Abstract

The escalating prevalence of counterfeiting and forgery has imposed unprecedented demands on advanced anti-counterfeiting technologies. Traditional luminescent materials, relying on single-mode or static emission, are inherently vulnerable to replication using commercially available phosphors or simple spectral blending. Multimode luminescent materials exhibiting excitation wavelength-dependent emission offer significantly higher encoding capacity and forgery resistance. Herein, we report the colloidal synthesis of lanthanide-doped Cs2ZrCl6 nanocrystals (Ln3+ = Tb, Eu, Pr, Sm, Dy, Ho) via a robust hot-injection route. These nanocrystals universally exhibit efficient host-to-guest energy transfer from self-trapped excitons (STEs) under 254 nm, yielding sharp characteristic Ln3+ f–f emission alongside the intrinsic broadband STE luminescence. Critically, Tb3+ enables direct 4f → 5d excitation at ~275 nm, while Eu3+ introduces a low-energy Eu3+ ← Cl− LMCT band at ~305 nm, completely bypassing STE emission. Due to their multimode luminescent characteristics, we fabricate a triple-mode anti-counterfeiting label displaying different colors under different types of excitation. These findings establish a breakthrough excitation-encoded multimode platform, offering potential applications for next-generation photonic security labels, scintillation detectors, and solid-state lighting applications.

1. Introduction

With the rapid expansion of the global commodity economy and the ever-increasing complexity of supply chains, counterfeiting of goods, documents, currencies, and high-value products has evolved into a critical worldwide challenge. Recent years have seen significant focus on developing strategies to prevent counterfeiting [1,2,3,4]. Photoluminescent materials that produce dynamic, multi-dimensional optical signatures under simple UV illumination have emerged as one of the most promising next-generation solutions, offering high encoding capacity, instant visual verifiability, and exceptional forgery resistance [5,6,7,8,9]. Among luminescent materials, lead halide perovskites (LHPs) have attracted immense interest due to their cost-effective solution processability and outstanding optical properties, such as high photoluminescence efficiency, color purity, stability, and tunable emission wavelength [10,11,12,13]. Moreover, LHPs can integrate with flexible material to prepare large-area security patterns through flexible printing techniques, such as screen printing, inkjet printing, and three-dimensional (3D) printing, which has led to the development of anti-counterfeiting and information encryption systems activated by UV light [14,15,16]. However, the toxicity of Pb2+ and poor stability of LPHs severely restrict their practical and commercial application [17,18,19].

In this regard, lead-free double perovskites, particularly vacancy-ordered A2BX6 compounds, have been intensively investigated because they are environmentally friendly and have high stability [20,21,22]. Notably, Cs2ZrCl6 stands out for its exceptional chemical robustness, negligible toxicity, and intrinsic broadband blue emission (~450 nm) arising from strongly bound self-trapped excitons (STEs) driven by Jahn–Teller distortion of [ZrCl6]2− octahedra [23,24]. However, the monochromatic emission of Cs2ZrCl6 limits its security level, as single-color responses are readily replicated using commercially available phosphors. Doping with metal ions is a well-established approach to tailoring the optical properties of halide perovskites as well as enhancing their stability [25,26]. Among various dopants, trivalent lanthanide ions (Ln3+) are particularly attractive owing to due to their narrow, atomic-like 4f–4f emission lines, high color purity, and rich energy levels, which collectively enable tunable luminescence spanning the ultraviolet to near-infrared spectral region [27,28,29]. Fang et al. prepared a serial of Ln3+-doped Cs2ZrCl6 microcrystals, enabling characteristic Tb3+ emission, while emissions from other types of Ln3+ were not observed [30]. Liu et al. synthesized various Ln3+-doped Cs2ZrCl6 nanocrystals and realized tunable luminescence between blue, green, and red [31]. Li et al. prepared Sb3+/Nd3+ co-doped Cs2ZrCl6, which enabled varied color delivery and showed great potential as anti-counterfeiting material [32]. Although multicolor emission under a single excitation wavelength has been achieved, realizing multi-modal luminescence under different excitation wavelengths in Cs2ZrCl6 remains a challenge.

Herein, we developed a strategy to prepared Ln3+-doped (Ln = Tb, Eu, Pr, Sm, Dy, Ho) Cs2ZrCl6 nanocrystals (NCs) with uniform size and morphology. Ln3+ doping into Cs2ZrCl6 nanocrystals enables efficient STE-to-Ln3+ energy transfer, producing lanthanide emission alongside the intrinsic blue STE band. Notably, Tb3+ exhibits an intense 4f→5d transition at ~275 nm whereas Eu3+ introduces a low-energy Eu3+ ← Cl− ligand-to-metal charge-transfer (LMCT) state at ~305 nm. By screen-printing Cs2ZrCl6:10 mol%Tb3+ and Cs2ZrCl6:10%Eu3+ into spatial regions, we fabricated a triple-mode excitation-encoded security label that displayed three different patterns under 254 nm, 275 nm, and 305 nm UV illumination.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Terbium acetate hydrate (Tb(OAc)3·xH2O, 99.99%), Europium acetate hydrate (Eu(OAc)3·xH2O, 99.99%) Cerium acetate hydrate (Ce(OAc)3·xH2O, 99.99%), Dysprosium acetate hydrate (Dy(OAc)3·xH2O, 99.99%), Samarium acetate hydrate(Sm(OAc)3·xH2O, 99.99%), Holmium acetate hydrate (Ho(OAc)3·xH2O, 99.99%), chlorotrimethylsilane (TMSCl, 99%), trimethylbromosilane (TMSBr, 99%), 1-octadecene (1-ODE,90%), oleylamine (OLA, 70%), and oleic acid (OA, 90%) were purchased from Sigma-(Shanghai, China). Cesium acetate (Cs(OAc), 99.99%), Praseodymium acetate hydrate (Pr(OAc)3·xH2O, 99.9%) was purchased from J&K Scientific Ltd., Beijing, China. Zirconium carbonate oxide (CO4Zr,99%) was purchased from Macklin Biochemical Co. Ltd., *Shanghai, China. Chloroform (CHCl3, 99%) was purchased from Guangshi Reagent Co. Ltd., Guangzhou, China. All chemicals were used as received without further purification.

2.2. Synthesis of Cs2ZrCl6 and Ln3+-Doped Cs2ZrCl6 Nanocrystals

Cs2ZrCl6 NCs were synthesized through a modified hot-injection method. In a typical procedure, 272 mg (1.42 mmol) of CsOAc and 123.7 mg (0.71 mmol) of CO4Zr were added to a 50 mL three-neck flask containing 10 mL of 1-ODE, 2.8 mL of oleic acid and 615 μL of oleylamine. The mixture was degassed and dried under a vacuum for at 110 °C for 30 min to obtain a clear, transparent solution. The mixture was then heated to 220 °C under an Ar atmosphere. Upon reaching this temperature, 400 μL TMSCl was rapidly injected. After reaction for about 45 s, the obtained crude solution was cooled in an ice-water bath. The resulting NCs were isolated by centrifugation at 7850 rpm for 5 min and the supernatant was discarded. The precipitate was redispersed in 4 mL of chloroform through vigorous vortexing to form a stable colloidal dispersion, followed by the addition of 8 mL ethanol to induce precipitation. The mixture was then centrifuged, and the supernatant was discarded. This washing procedure was repeated twice. Finally, the cleaned product was redispersed in 4 mL of chloroform for storage.

Ln3+-doped Cs2ZrCl6 NCs (Ln = Tb, Eu, Dy, Pr, Sm, Ho) were prepared following the same procedure by adding the corresponding lanthanide (III) acetate hydrate.

2.3. Materials’ Characterizations

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was carried out on a MiniFlex600 X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation λ = 1.5406 Å (Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images were acquired using a HT7700 tungsten filament transmission electron microscope (Hitachi High-Tech Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). High-resolution TEM images and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping were recorded on an F200 field emission transmission electron microscope equipped with an EDS attachment (JEOL). Photoluminescence spectra were acquired using an FS5 Transient spectrometer (Edinburgh Instruments Ltd., Livingston, UK). Fluorescence decay curves and photoluminescence quantum yields were recorded on an FLS1000 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Edinburgh Instruments Ltd., Livingston, UK).

2.4. Fabrication of Security Pattern

The security patterns were prepared by using Cs2ZrCl6: 10 mol%Tb3+ and red Cs2ZrCl6: 10 mol%Eu3+ NCs. Luminescent inks were prepared by mixing the PDMS glue and curing agent at a mass ratio of 10:1. Subsequently, the Cs2ZrCl6: 10 mol%Tb3+ (or Cs2ZrCl6: 10 mol%Eu3+) phosphor were added to the PDMS mixture at a mass ratio of 3:2 and vigorously stirred for 5 h to ensure homogeneous dispersion. The resulting mixture was then screen-printed onto polypropylene (PP) substrates using custom-designed stencils. After printing, the patterns were cured at 80 °C for 10 min. Photographs of the security patterns under 254 nm, 275 nm, and 305 nm excitation were recorded in a dark chamber with handheld UV lamps.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural and Morphological Properties of Tb3+-Doped Cs2ZrCl6 NCs

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns reveals that samples doped with Tb3+ below 10 mol% retain the pure cubic vacancy-order double-perovskite structure of Cs2ZrCl6 (space group Fmm, PDF#74-1001), with no detectable impurity phase (Figure 1a). The host lattice consists of isolated [ZrCl6]2− octahedra alternatively arranged with ordered vacancies and separated by Cs+ cation (Figure 1b) [33]. Given the close ionic radii and identical octahedral coordination preference of Tb3+ (r ≈ 0.92 Å, CN = 6) and Zr4+ (r = 0.72 Å, CN = 6), Tb3+ ions preferentially substitute at Zr4+ sites, forming [TbCl6]3− units, instead of substitution at the larger Cs+ site (r = 1.68 Å, CN = 8) [31,34,35]. The resulting charge imbalance from this aliovalent substitution is typically compensated by the formation of chloride vacancies to preserve lattice electroneutrality [26]. When the concentration of Tb3+ reaches 10 mol%, weak additional diffraction peaks emerge in the 20° range, which is attributable to trace TbCl3·xH2O. Upon further increasing the Tb3+ concentration to 12.5 mol%, more extraneous peaks emerged, showcasing the formation of Cs3TbCl6. This phase segregation is attributed to the combined effects of ionic radius mismatch between Tb3+ and Zr4+ ions, which collectively induce lattice strain and thermodynamic instability beyond ~10 mol% doping. This solubility limit arises from cumulative lattice strain induced by ionic radius mismatch and electrostatic imbalance between Tb3+ and Zr4+; collectively, these factors destabilize the solid-solution formation and drive phase segregation at higher doping levels [31,34].

Figure 1.

(a) Powder XRD patterns of Cs2ZrCl6:xTb3+ NCs. The diffraction peaks marked with diamonds and triangles correspond to TbCl3·xH2O and Cs3TbCl6, respectively. (b) Schematic of the crystal structure of Cs2ZrCl6:Ln3+ NCs.

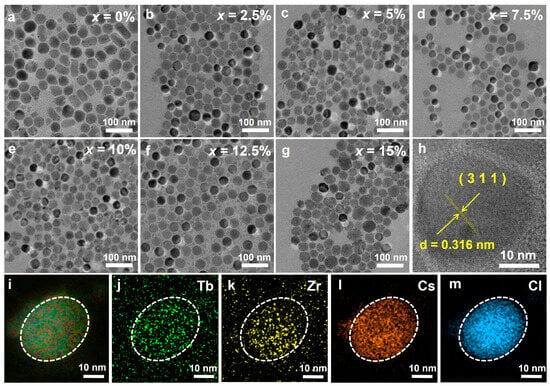

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images show that Cs2ZrCl6:xTb3+ NCs exhibited quasi-spherical, prism-like, and polygonal morphologies, with most having sizes of around 30 nm (Figure 2a–g). Upon Tb3+ doping, the number of prism-like particles decreases, likely because Tb3+ alters surface energy and growth kinetics [26]. All the prepared NCs exhibit excellent dispersion, regular morphology, and uniform size. The high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM) image shows clear lattice fringes, indicating the single-crystalline nature of the Cs2ZrCl6 nanocrystals (Figure 2h). The observed d-spacing of lattice fringes is ~0.316 nm, which is in good agreement with the lattice spacing of (311) planes of Cs2ZrCl6 (PDF#741001). Furthermore, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping demonstrates the homogeneous elements distributions of Cs, Zr, Tb and Cl through the individual Cs2ZrCl6: 10 mol% Tb3+ NCs (Figure 2i–m), further confirming the successful doping of Tb3+ ions into the Cs2ZrCl6 host matrix.

Figure 2.

(a–g) TEM images of Cs2ZrCl6: xTb3+ (x = 0–15 mol%) NCs. (h) High-resolution TEM image of a single Cs2ZrCl6:Tb3+ NCs. (i–m) Elemental mappings of Tb, Zr, Cs and Cl for Cs2ZrCl6:Tb3+ NC.

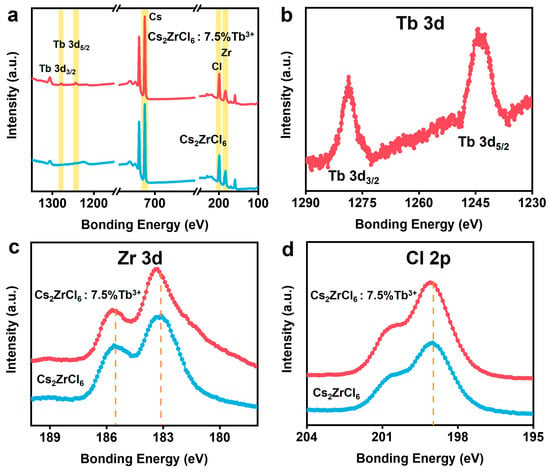

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurement was performed to further explore the valence state and chemical composition of ions in Cs2ZrCl6 nanocrystals with and without Tb3+ doping (Figure 3a). With the doping of Tb3+, two peaks corresponding to Tb were observed. Furthermore, the two peaks at 1278 and 1243 eV were attributed to Tb 3d3/2 and Tb 3d5/2, respectively (Figure 3b), as well as two peaks at ~182.7 and ~185.1 eV which were attributed to Zr 3d5/2 and Zr 3d3/2, respectively (Figure 3c). A slight blue shift was observed in the Zr 3d and Cl 2p XPS peaks of Tb3+-doped Cs2ZrCl6 nanoparticles (Figure 3c,d). This was due to the charge imbalance induced by Tb3+ substituting Zr4+, which is consistent with prior reports on aliovalent doping in halide perovskites [36,37].

Figure 3.

(a) Wide XPS spectrum of Cs2ZrCl6:Tb3+. (b–d) High-resolution XPS spectra of Tb, Zr and Cl.

3.2. Optical Properties of Ln3+-Doped Cs2ZrCl6 NCs

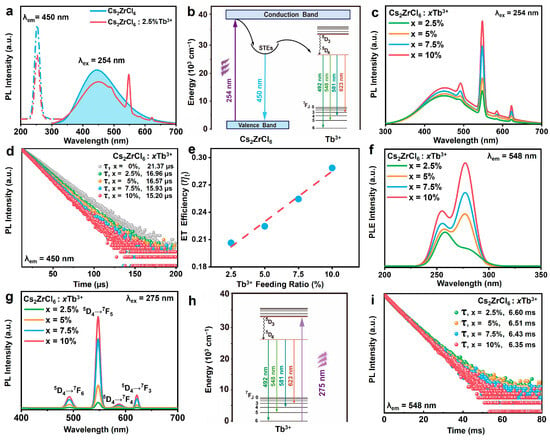

The optical properties of as-prepared Cs2ZrCl6 NCs doped with Tb3+ ions were systematically investigated. The PLE spectrum of pristine Cs2ZrCl6 NCs monitored at 450 nm exhibits a sharp excitation peak located at 254 nm, which is attributed to the Zr–Cl ligand-to-metal charge transfer transition (LMCT) in [ZrCl6]2- complex clusters (Figure 4a) [38,39]. Such charge transfer transitions were widely observed not only in metal oxide complexes like [VO4]3− but in other perovskite-structured materials such as Cs2HfCl6 [40,41]. Upon the excitation at 254 nm, undoped Cs2ZrCl6 NCs exhibited a broad emission peak centered at 450 nm (Figure 4a). This broad emission of the matrix was ascribed to intrinsic STEs of the host in consequence of the strong electron–phonon coupling in metal halides with a soft lattice [42,43,44,45]. For Tb3+-doped Cs2ZrCl6 NCs, the host STE emission (~450 nm) sharply declined, accompanied by the emergence of intense 492 nm, 548 nm, 581 nm and 623 nm under the excitation at 254 nm (Figure 4a). These discrete peaks are assigned to the 5D4 → 7FJ (J = 6, 5, 4, 3) intra-configurational transitions of Tb3+ ions driven by efficient energy transfer from STEs to Tb3+ ions (Figure 4b). Under 254 nm excitation, electrons were promoted from the valence band to the conduction band, followed by non-radiative relaxation into self-trapped states within distorted [ZrCl6]2− octahedra, yielding the characteristic broad blue STE emission. In the presence of Tb3+, a fraction of this trapped energy resonantly transferred to the Tb3+ 5d manifold via Förster–Dexter exchange [32,44], followed by rapid internal conversion to the 5D4 level and subsequent radiative decay to the 7Fⱼ ground states, producing sharp Tb3+ emission lines. Thus, under 254 nm excitation, Tb3+ luminescence was primarily sensitized by host STEs rather than direct dopant excitation, highlighting the critical role of the host-to-guest energy channel in enabling tunable emission color.

Figure 4.

(a) PLE (dashed lines) and PL (solid lines) spectra of undoped (blue) and 10% Tb3+ doped Cs2ZrCl6 NCs (red). (b) The photoluminescence mechanism diagram of Cs2ZrCl6: Tb3+ NCs excited under 254 nm. (c) PL spectra of Cs2ZrCl6: (2.5–10%) Tb3+ NCs excited by 254 nm. (d) The decay curves of Cs2ZrCl6: (2.5–10 mol%) Tb3+ NCs monitored at 450 nm. (e) The ET efficiency (ηt) variation of Cs2ZrCl6: (2.5–10 mol%) Tb3+ NCs (monitored at 450 nm) as a function of the Tb3+ feeding ratio. The dashed line is the linear regression of the measured data. (f) PLE spectra of Cs2ZrCl6: (2.5–10 mol%) Tb3+ NCs monitored at 548 nm. (g) PL spectra of Cs2ZrCl6: (2.5–10 mol%) Tb3+ NCs in the visible region excited by 275 nm. (h) The photoluminescence mechanism diagram of Cs2ZrCl6: Tb3+ NCs excited at 275 nm. (i) The decay curves of Cs2ZrCl6: (2.5–10 mol%) Tb3+ NCs monitored at 548 nm.

To shed more light on the optical properties of Cs2ZrCl6: Tb3+ NCs, Cs2ZrCl6 with Tb3+ doping concentrations ranging from 2.5 to 10 mol% was investigated. As the Tb3+ concentration increased, the Tb3+ characteristic emission gradually enhanced. Remarkably, the STE emission band at ~450 nm recovered slightly in intensity rather than exhibiting the anticipated decrease typically observed in conventional donor–acceptor systems (Figure 4c). The enhancement of host STE emission is ascribed to Tb3+-induced lattice expansion upon substitution of the smaller Zr4+. This structural relaxation exacerbates the Jahn–Teller distortion of the [ZrCl6]2−/[TbCl6]3− octahedra in the excited state, thereby deepening the self-trapping potential and ultimately enhancing the radiative efficiency of STE recombination [42,46,47].

To further understand the ET process from host STEs to Tb3+ ions, PL decay curves of Cs2ZrCl6: Tb3+ NCs ( = 0~10 mol%) were recorded at 450 nm under 254 nm excitation (Figure 4d). The effective lifetimes were determined by [48]

where I0 and I(t) represent the maximum luminescence intensity and luminescence intensity at time t after cutting off the excitation light, respectively. Upon Tb3+ doping, the effective STE lifetime decreased from ~21.37μs to ~15.20 μs, further demonstrating the non-radiative energy transfer from the host to Tb3+. The progressive acceleration of decay with increasing Tb3+ concentration confirms that ET is enhanced at higher dopant concentrations, consistent with reduced average donor–acceptor separation. The ET efficiency (ηt) was adopted and can be calculated by the following equation [32]:

where and are the lifetimes of STEs in the presence or absence of Tb3+ ions, respectively. Figure 4e shows that the ET efficiency () from host STEs to Tb3+ increases gradually with the Tb3+ doping concentration, reaching a maximum (ca. 28%) when Tb3+ feeding concentrations are at 10%. The ET efficiency of Ln3+-doped Cs2ZrCl6 NCs is obviously higher than that of Cs2ZrCl6 microcrystals (ca. 20%). Furthermore, the ET course in perovskite doped with weak-emission Ln3+ ions cannot be detected in Cs2ZrCl6 MCs, but Cs2ZrCl6 NCs can, indicating that nanocrystals are more advantageous when it comes to studying the ET process in perovskite doped with Ln3+ ions [30].

The excitation spectra monitored at 548 nm (5D4 → 7F5 transition) reveals, in addition to the host STE band at 254 nm, a distinct new excitation peak centered at 275 nm in Tb3+-doped Cs2ZrCl6 NCs. This 275 nm band is absent in undoped samples and scales linearly with the Tb3+ concentration (Figure 4f), confirming its origin from f–d transition of Tb3+ ions (Figure 4h). Excitation wavelength-dependent PL spectra further demonstrate two independent sensitization channels. When Cs2ZrCl6: Tb3+ NCs were excited by 275 nm, only the feature emission of Tb3+ ions existed without the host STEs emission. As the Tb3+ doping concentration increased, the intensity of characteristic emission of Tb3+ ions was augment little by little, as illustrated in Figure 4g. The Tb3+ lifetimes monitored at 548 nm show only slight shortening as the Tb3+ doping concentration increases (Figure 4i). This behavior arises from the vacancy-ordered structure of Cs2ZrCl6, which features isolated [ZrCl6]2−/[TbCl6]3− octahedra separated by Cs+ cations and ordered vacancies. Such spatial confinement effectively isolates individual Tb3+ dopants, minimizing energy migration between sites and suppressing concentration quenching through cross-relaxation or non-radiative trapping [49,50].

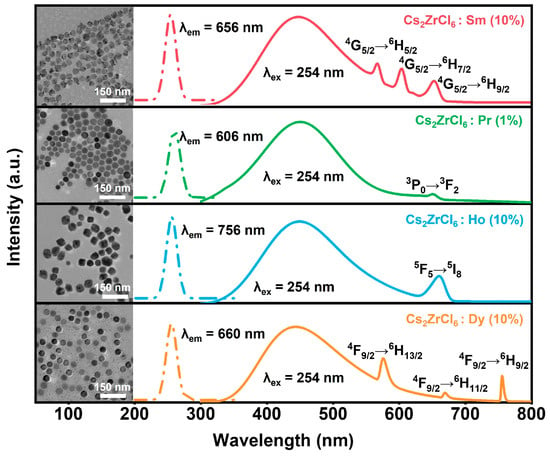

To assess the universality of host-sensitized lanthanide luminescence in Cs2ZrCl6 NCs, a series of additional Ln3+ (Ln = Pr, Sm, Dy, Ho) ion-doped Cs2ZrCl6 NCs were prepared using the identical hot injection protocol. Based on the XRD results for Tb doping, impurity phases of Cs3LnCl6 form when the Ln3+ concentration exceeds 10 mol%. Therefore, the doping level for Sm3+, Dy3+, and Ho3+ is set at 10 mol%. For Pr3+, the concentration is reduced to 1 mol% due to its pronounced susceptibility to concentration quenching. TEM images confirm that all Ln3+-doped Cs2ZrCl6 nanocrystals retain highly uniform morphology and an average particle size of ~30 nm (inset of Figure 5). PLE spectra monitored for the respective Ln3+ emissions reveal that all these Ln3+-doped samples exhibit a dominant excitation peak at 254 nm, corresponding to the host Zr4+ ← Cl− ligand-to-metal charge-transfer (LMCT) transition. Under 254 nm excitation, all the samples exhibiting composite emission spectra comprise a broad blue STE band centered at ~450 nm and well-resolved f-f transition emission of the respective Ln3+ activators (Figure 5). The consistent observation of Ln3+-specific f–f emission across this diverse set of Ln3+ ions provides compelling evidence for efficient and universal STE-to-Ln3+ energy transfer in the Cs2ZrCl6 NC, enabling tunable multicolor luminescence via a single broadband sensitizer.

Figure 5.

PLE (dashed lines) and PL (solid lines) spectra of Cs2ZrCl6:Ln3+ (Ln = Pr, Sm, Dy, Ho) NCs. Inset: TEM images of Cs2ZrCl6:Ln3+ (Ln = Pr, Sm, Dy or Ho) NCs.

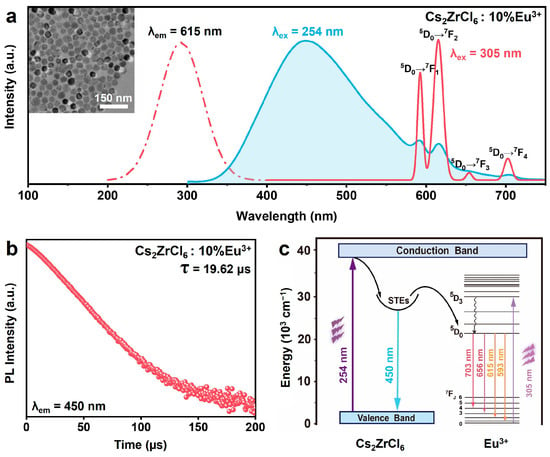

Compared to Dy3+-, Sm3+-, Pr3+-, or Ho3+-doped Cs2ZrCl6 NCs, the excitation spectrum of Cs2ZrCl6: 10 mol% Eu3+ NCs monitoring at 615 nm (5D0 → 7F2 transition of Eu3+) shows a pronounced redshift of the dominant excitation peak from 254 nm to a wide band centered at 305 nm (Figure 6a). The redshift is attributed to the formation of a low-energy Eu3+ ← Cl− LMCT state that lies below the intrinsic Zr4+ ← Cl− LMCT band of the host lattice. The host LMCT at 254 nm remains detectable and the STE emission is accompanied by weak Eu3+ f–f lines, indicative of a partial STE-to-Eu3+ energy transfer under 254 nm excitation (Figure 6c). A decay curve monitored at 450 nm shows a lifetime of ~19.62 μs for Cs2ZrCl6: 10 mol% Eu3+ (Figure 6b), which is slightly shorter than that of undoped Cs2ZrCl6, confirming the energy transfer from STEs to Eu3+ ions. The transfer efficiency is about ~8.2%, lower than that observed in Tb3+-doped Cs2ZrCl6. Notably, the Eu3+ ← Cl− CT state becomes the dominant excitation pathway for Eu3+ luminescence. Notably, 305 nm excitation selectively populates the Eu3+-centered CT state, resulting in pure sharp Eu3+ f–f transition emission lines with complete suppression of the host STE broadband emission (~450 nm).

Figure 6.

(a) PLE (dashed lines) and PL (solid lines) spectra of 10 mol% Eu3+-doped Cs2ZrCl6 NC. Inset: TEM image of Cs2ZrCl6:10 mol% Eu3+ NCs. (b) The photoluminescence mechanism diagram of Cs2ZrCl6: Eu3+ NCs excited at 254 nm and 305nm. (c) The decay curves of Cs2ZrCl6: 10 mol% Eu3+ NCs monitored at 450 nm.

3.3. Anti-Counterfeit Application of Ln3+-Doped Cs2ZrCl6 NCs

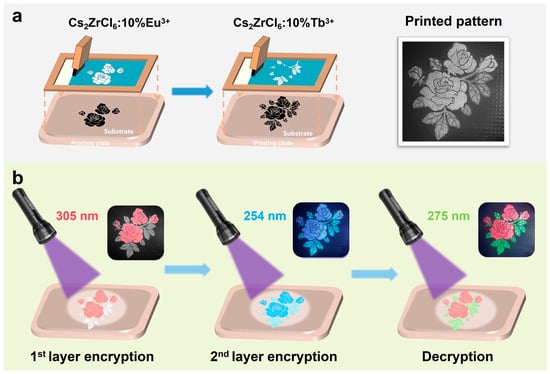

To exploit the distinct excitation wavelength-dependent luminescence of Tb3+- and Eu3+-doped Cs2ZrCl6 nanocrystals, we fabricated a multimode optical security pattern by spatially integrating Cs2ZrCl6:10 mol% Tb3+ and Cs2ZrCl6:10 mol% Eu3+ phosphors in different regions within a flexible composite matrix (Figure 7a). The pattern was produced via sequential screen-printing onto a polypropylene (PP) substrate, employing luminescent inks prepared by dispersing the nanocrystals in polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) at a phosphor-to-PDMS mass ratio of 3:2. Specifically, the flower region was first printed using a Cs2ZrCl6:10%Eu3+@PDMS ink, followed by printing of the leaf region with Cs2ZrCl6:10%Tb3+@PDMS ink.

Figure 7.

(a) Schematic of multicolor pattern preparation through serial screen printing and a photograph of the pattern under ambient light. (b) Optical photographs of the prepared pattern under 295 nm, 254 nm, and 275 nm UV lamp excitation, respectively.

The resulting security label exhibits three fully orthogonal luminescence responses depending solely on the excitation wavelength (Figure 7b). Under 305 nm excitation, corresponding to the low-energy Eu3+ ← Cl− LMCT state, only the flower region emits intense red light, dominated by the Eu3+ 5D0 → 7F1 and 7F2 transition at 595 and 611 nm. Meanwhile, the leaf region remains dark due to negligible absorption by either the Cs2ZrCl6 host bandgap or the Tb3+ transitions in this wavelength range. At 254 nm excitation, both the leaf and flower region display blue emission (~450 nm) arising from STE recombination within the Cs2ZrCl6 host, resulting in complete pattern visualization in a single color. Under 275 nm excitation, the flower region exhibits dominant red emission from Eu3+, whereas the leaf region emits green light arising from f-f transition of Tb3+ ions. This triple-mode, excitation wavelength-encoded behavior renders replication difficult and prohibitive using conventional phosphor blending, significantly enhancing the security level of the anti-counterfeiting feature.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we have established a robust and reproducible hot-injection protocol for the synthesis of Ln3+-doped Cs2ZrCl6 nanocrystals (Ln = Tb, Eu, Pr, Sm, Dy, Ho) that delivers uniform size and morphology. Systematic spectroscopic investigations reveal universal and efficient energy transfer from STEs to Ln3+ activators. Tb3+-doped nanocrystals exhibit two independent sensitization routes: host LMCT excitation at 254 nm produces composite STE and Tb3+ emission, whereas direct 4f → 5d absorption at 275 nm yields pure green Tb3+ luminescence. Eu3+ doping introduces a low-energy Eu3+ ← Cl− LMCT band at ~305 nm, enabling pure f–f transition emission of Eu3+ without host STE luminescence. We demonstrate an advanced triple-mode, excitation wavelength-dependent anti-counterfeiting technology based on Cs2ZrCl6:10 mol% Tb3+ and Cs2ZrCl6:10 mol% Eu3+ NCs. This present work establishes Cs2ZrCl6 nanocrystals as a versatile, broadband-sensitizing host for lanthanide luminescence, offering excitation-tunable multicolor emission for next-generation photonic security labels, scintillation detectors, and solid-state lighting applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Y., Q.W. and X.C.; methodology, L.Y. and Q.W.; validation, Y.L., X.Z. and K.D.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Y.; writing—review and editing, K.D. and X.C.; supervision, X.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Foundation of Shenzhen (JCYJ20220531101807017 and 20231122012004001), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52272159 and 62204158), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2022B1515020072), and the Project of Department of Education of Guangdong Province (2021ZDZX1006).

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PL | Photoluminescence. |

| PLE | Photoluminescence. |

| UV | Ultraviolet. |

| NCs | Nanocrystals. |

| MCs | Microcrystals. |

| LHP | Lead halide perovskites. |

| STEs | Self-trapping excitons. |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy. |

| HRTEM | High-resolution transmission electron microscopy. |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction. |

| EDS | Energy-dispersive spectrometer. |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope. |

| ET | Energy transfer. |

| PDMS | Polydimethylsiloxane. |

References

- Ying, W.; Nie, J.; Fan, X.; Xu, S.; Gu, J.; Liu, S. Dual-Wavelength Responsive Broad Range Multicolor Upconversion Luminescence for High-Capacity Photonic Barcodes. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2021, 9, 2100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Dong, B.; Lu, Y.; Yang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Bai, W.; Wu, S.; Ji, Z.; Lu, C.; Zhang, K.; et al. Energy Manipulation in Lanthanide-Doped Core–Shell Nanoparticles for Tunable Dual-Mode Luminescence toward Advanced Anti-Counterfeiting. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2002121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Tian, Y.; Xiang, C.; Liu, W.; Zhou, Z.; Cui, J.; Chen, X. Visible-Light-Driven Photoswitchable Fluorescent Polymers for Photorewritable Pattern, Anti-Counterfeiting, and Information Encryption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2303765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Jiang, C.; Ng, S.H.; Lu, Y.; Han, F.; Bach, U.; Gooding, J.J. Unclonable Plasmonic Security Labels Achieved by Shadow-Mask-Lithography-Assisted Self-Assembly. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 2330–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Q.; Tang, Y.; Huang, Z.Y.; Wang, F.Z.; Qiu, P.F.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.H.; Li, Q. A Dual-Responsive Liquid Crystal Elastomer for Multi-Level Encryption and Transient Information Display. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202313728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, D.; Sun, Y.; Li, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, J.; Pan, C.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, X.; Liu, W. Double Lock Label Based on Thermosensitive Polymer Hydrogels for Information Camouflage and Multilevel Encryption. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202117066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Feng, D.; Chen, G.; Chen, X.; Hong, W. Re-Printable Chiral Photonic Paper with Invisible Patterns and Tunable Wettability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2009916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, M.; Zou, S.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, K.; Li, X.; Ma, H.; Li, B.; Huang, W. A Spatiotemporal Cascade Platform for Multidimensional Information Encryption and Anti-Counterfeiting Mechanisms. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2302146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Liu, Z.; Liu, B.; Wang, K.; Dong, X.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, C.; Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Huang, W. Thermally-induced phase fusion and color switching in ionogels for multilevel information encryption. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 479, 147544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, N.; Tian, H.; Guo, J.; Wei, Y.; Chen, H.; Miao, Y.; Zou, W.; Pan, K.; He, Y.; et al. Perovskite light-emitting diodes based on spontaneously formed submicrometre-scale structures. Nature 2018, 562, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, K.; Xing, J.; Quan, L.N.; de Arquer, F.P.G.; Gong, X.; Lu, J.; Xie, L.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, D.; Yan, C.; et al. Perovskite light-emitting diodes with external quantum efficiency exceeding 20 per cent. Nature 2018, 562, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldhuis, S.A.; Boix, P.P.; Yantara, N.; Li, M.; Sum, T.C.; Mathews, N.; Mhaisalkar, S.G. Perovskite Materials for Light-Emitting Diodes and Lasers. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 6804–6834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Wang, J.-X.; Li, Y.; Huang, H.; Wang, J.; Shi, T.; Deng, Y.; Yuan, Q.; He, R.; Chu, P.K.; et al. Multilevel Information Encryption Based on Thermochromic Perovskite Microcapsules via Orthogonal Photic and Thermal Stimuli Responses. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 10874–10884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Meng, L.; Jiang, F.; Ge, Y.; Li, F.; Wu, X.G.; Zhong, H. In Situ Inkjet Printing Strategy for Fabricating Perovskite Quantum Dot Patterns. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1903648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Hu, S.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, N.; Lee, S.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, R.; Yang, J.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; et al. Three-Dimensional Perovskite Nanopixels for Ultrahigh-Resolution Color Displays and Multilevel Anticounterfeiting. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 5186–5194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Liao, J.; Sun, H.; Ji, D.; Pang, R.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Liu, S. Highly Luminescent and Stable Perovskite Quantum Dots Films for Light-Emitting Devices and Information Encryption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2316717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Zhang, F.; Tian, L.; You, L.; Wu, J.; Wen, N.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Gan, F.; Yu, H.; et al. Modified Fabrication of Perovskite-Based Composites and Its Exploration in Printable Humidity Sensors. Polymers 2022, 14, 4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkerman, Q.A.; Rainò, G.; Kovalenko, M.V.; Manna, L. Genesis, challenges and opportunities for colloidal lead halide perovskite nanocrystals. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante, I.; Manna, L. Are There Good Alternatives to Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals? Nano Lett. 2020, 21, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yang, J.; Lee, J.I.; Cho, J.H.; Kang, M.S. Lead-Free Perovskite Nanocrystals for Light-Emitting Devices. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 1573–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Biesold-McGee, G.V.; Ma, J.; Xu, Q.; Pan, S.; Peng, J.; Lin, Z. Lead-Free Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals: Crystal Structures, Synthesis, Stabilities, and Optical Properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 59, 1030–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Xu, Y.; Hu, X.; Hu, Q.; Chen, T.; Jiang, W.; Wang, L.; Jiang, W. Lead-Free Halide Double Perovskite Nanocrystals for Light-Emitting Applications: Strategies for Boosting Efficiency and Stability. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2004118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Yang, B.; Chen, J.; Wei, D.; Zheng, D.; Kong, Q.; Deng, W.; Han, K. Efficient Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence from All-Inorganic Cesium Zirconium Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 21925–21929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abfalterer, A.; Shamsi, J.; Kubicki, D.J.; Savory, C.N.; Xiao, J.; Divitini, G.; Li, W.; Macpherson, S.; Gałkowski, K.; MacManus-Driscoll, J.L.; et al. Colloidal Synthesis and Optical Properties of Perovskite-Inspired Cesium Zirconium Halide Nanocrystals. ACS Mater. Lett. 2020, 2, 1644–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroyuk, O.; Raievska, O.; Hauch, J.; Brabec, C.J. Doping/Alloying Pathways to Lead-Free Halide Perovskites with Ultimate Photoluminescence Quantum Yields. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202212668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-H.; Biesold-McGee, G.V.; Liu, Y.; Kang, Z.; Lin, Z. Doping and ion substitution in colloidal metal halide perovskite nanocrystals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 4953–5007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Bai, X.; Yang, D.; Chen, X.; Jing, P.; Qu, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, D.; Zhu, J.; Xu, W.; et al. Doping Lanthanide into Perovskite Nanocrystals: Highly Improved and Expanded Optical Properties. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 8005–8011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Yang, B.; Chen, J.; Zheng, D.; Tang, Z.; Deng, W.; Han, K. Colloidal Synthesis and Tunable Multicolor Emission of Vacancy-Ordered Cs2HfCl6 Perovskite Nanocrystals. Laser Photonics Rev. 2021, 16, 2100439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, M.; Shrivastava, N.; McClain, S.T.; Adhikari, C.M.; Guzelturk, B.; Khanal, R.; Gautam, B.; Luo, Z. Luminescence from Self-Trapped Excitons and Energy Transfers in Vacancy-Ordered Hexagonal Halide Perovskite Cs2HfF6 Doped with Rare Earths for Radiation Detection. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2022, 10, 2201374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Yang, J.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, Z.; Mao, Y.; Yun, X.; Liu, L.; Xu, D.; Li, X.; Zhou, J. Energy transfer from self-trapped excitons to rare earth ions in Cs2ZrCl6 perovskite variants. J. Mater. Chem. C 2023, 11, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yun, R.; Yang, H.; Sun, W.; Li, Y.; Lu, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, X. Lattice doping of lanthanide ions in Cs2ZrCl6 nanocrystals enabling phase transition and tunable photoluminescence. Mater. Horiz. 2024, 11, 5341–5351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Han, K.; Li, Z.; Yue, H.; Fu, X.; Wang, X.; Xia, Z.; Song, S.; Feng, J.; Zhang, H. Multiple Energy Transfer Channels in Rare Earth Doped Multi-Exciton Emissive Perovskites. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2307354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, M.-G.; Chen, M.; Zhou, Y.; Garces, H.F.; Dai, J.; Ma, L.; Padture, N.P.; Zeng, X.C. Earth-Abundant Nontoxic Titanium(IV)-based Vacancy-Ordered Double Perovskite Halides with Tunable 1.0 to 1.8 eV Bandgaps for Photovoltaic Applications. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Ma, X.; Dong, G.; Yan, H. Mechanochemical synthesis of Sb3+-doped Cs2ZrCl6 double perovskites for excitation-wavelength-responsive trimodal luminescence and high-level anti-counterfeiting. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 26800–26806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Rong, X.; Li, M.; Molokeev, M.S.; Zhao, J.; Xia, Z. Incorporating Rare-Earth Terbium(III) Ions into Cs2AgInCl6:Bi Nanocrystals toward Tunable Photoluminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 11634–11640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Hills-Kimball, K.; Yang, H.; Nagaoka, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Zia, R.; Chen, O. Mn2+/Yb3+ Codoped CsPbCl3 Perovskite Nanocrystals with Triple-Wavelength Emission for Luminescent Solar Concentrators. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 2001317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhong, G.; Yin, Y.; Miao, J.; Li, K.; Wang, C.; Xu, X.; Shen, C.; Meng, H. Aluminum-Doped Cesium Lead Bromide Perovskite Nanocrystals with Stable Blue Photoluminescence Used for Display Backlight. Adv. Sci. 2017, 4, 1700335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donker, H.; Smit, W.M.A.; Blasse, G. On the luminescence of Te4+ in A2ZrCl6 (A = Cs, Rb) and A2ZrCl6 (A = Cs, Rb, K). J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1989, 50, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.; Yuan, L.; Jin, Y.; Wu, H.; Li, Z.; Qu, B.; Ju, G.; Chen, L.; Yang, S.; Hu, Y. Aliovalent Doping and Surface Grafting Enable Efficient and Stable Lead-Free Blue-Emitting Perovskite Derivative. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2020, 8, 2000779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeki, K.; Fujimoto, Y.; Koshimizu, M.; Yanagida, T.; Asai, K. Comparative study of scintillation properties of Cs2HfCl6 and Cs2ZrCl6. Appl. Phys. Express 2016, 9, 042602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, A.; Rowe, E.; Groza, M.; Morales Figueroa, K.; Cherepy, N.J.; Beck, P.R.; Hunter, S.; Payne, S.A. Cesium hafnium chloride: A high light yield, non-hygroscopic cubic crystal scintillator for gamma spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 143505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, L.A.; Sisira, S.; Mani, K.P.; Thomas, K.; Alexander, D.; Biju, P.R.; Unnikrishnan, N.V.; Joseph, C. A new potential green-emitting erbium-activated α-Na3Y(VO4)2 nanocrystals for UV-excitable single-phase pc-WLED applications. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Luo, J.; Liu, J.; Tang, J. Self-Trapped Excitons in All-Inorganic Halide Perovskites: Fundamentals, Status, and Potential Applications. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 1999–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Muhammad, Y.; Ding, D.; Liu, Z.; Hu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, H.; Shi, Y.; Li, H. Dexter Energy Transfer in Zero-Dimensional Inorganic Metal Halides for Obtaining Near-Unity PLQY via Sb3+/Mn2+ Codoping. J. Phys. Chem. C 2024, 128, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wei, Q.; Wang, S.; Rogach, A.L.; Xing, G.; Shi, P.; Wang, F. Multiexcitonic Emission in Zero-Dimensional Cs2ZrCl6:Sb3+ Perovskite Crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 17599–17606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Juan, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhang, W.; Zeng, H.; Li, X. Efficient, Stable, and Tunable Cold/Warm White Light from Lead-Free Halide Double Perovskites Cs2Zr1-xTexCl6. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2021, 9, 2100815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Brédas, J.-L.; Bakr, O.M.; Mohammed, O.F. Boosting Self-Trapped Emissions in Zero-Dimensional Perovskite Heterostructures. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 5036–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Deng, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Han, Y.; Zhu, H.; Chen, X.; Liu, X. Tuning upconversion through energy migration in core–shell nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 968–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, S.; Samanta, A. Photoluminescence of Zero-Dimensional Perovskites and Perovskite-Related Materials. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017, 9, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xia, Z. Recent progress of zero-dimensional luminescent metal halides. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 2626–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.