Abstract

A

thick polycrystalline

film was sputter-deposited onto a circular 3-inch diameter,

thick single-crystal wafer with

surface layers. The magnetoresistance (MR) of the sample was analyzed as a function of applied DC magnetic field and temperature using the Van der Pauw technique. Magnetic measurements were carried out over a temperature range of 25 °C to 350 °C using a Lake Shore Hall Effect Measurement System (HEMS). An external magnetic field ranging from

to

was applied at each temperature value to observe changes in resistance. Hall coefficients and resistance were obtained by applying current in both directions with different contact configurations. Machine learning techniques, including Random Forest Regression, were employed to predict magnetoresistivity beyond 350 °C; the best-performing model achieved

values up to

with MSE as low as

, and enabled Curie temperature estimation with

. This study highlights the potential of machine learning in accurately forecasting material properties beyond experimental limits, providing enhanced predictive models for the magnetoresistive behavior and critical temperature transitions of

.

1. Introduction

Magnetoresistive sensors are essential components in high-density information storage and position/speed monitoring technologies [1]. Their performance is influenced not only by the field dependence of the material parameters but also by the geometric configuration of the device [2]. Narrow band-gap semiconductors such as InSb have attracted considerable interest due to their high carrier mobilities, which provide superior sensitivity and extended frequency response beyond the 10–20 kHz range typical of Si Hall sensors [3].

(Permalloy) is widely employed in spin-valve read heads because of its negligible magnetostriction, which effectively minimizes stress-induced anisotropy [4,5]. In ferromagnetic metals like

, electrical resistivity is strongly influenced by spin-dependent scattering processes. The likelihood of such scattering depends on spin orientation and magnetic ordering [6], giving rise to the anisotropic magnetoresistance (AMR) effect. When magnetization is aligned by an external field, spin disorder is reduced, resulting in lower electron scattering and decreased resistivity. In contrast, at zero field, a demagnetized multi-domain state enhances spin-disorder scattering, leading to higher resistivity. Temperature introduces additional effects: as it rises, thermal spin disorder increases resistivity, and near the Curie temperature (), critical spin fluctuations produce a pronounced peak [7]. This phenomenon—often described as enhanced spin-disorder scattering in the critical region—is analogous to the Curie–Weiss behavior of magnetic susceptibility. Above

, susceptibility follows the Curie–Weiss law, reflecting the loss of long-range ferromagnetic order. Below

, spontaneous magnetization decreases progressively with temperature and vanishes at

through a second-order phase transition. This temperature dependence, sometimes approximated by mean-field models such as

provides the theoretical framework for interpreting our high-temperature magnetotransport data.

In practice, extending magnetoresistivity characterization to elevated temperatures is challenging: measurements may be limited by instrument constraints and affected by thermal drift, contact-resistance changes, or irreversible modifications in ultrathin films (e.g., oxidation or interdiffusion). Moreover, the high-temperature response reflects multiple competing scattering mechanisms, including spin-disorder contributions that grow with temperature and can become strongly non-linear near the Curie region. These factors make straightforward extrapolation beyond the experimentally accessible range unreliable and motivate data-driven surrogate models for robust high-temperature prediction.

Despite significant advances in magnetoresistive technology, accurately predicting material properties, such as magnetoresistivity at elevated temperatures, remains a challenge [8]. Traditional experimental methods often face limitations when extending observations beyond experimentally feasible conditions [9]. In recent years, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful tool to address these challenges, enabling data-driven predictions that extend beyond the limits of experimental data [10,11,12,13].

The novelty of the present work is to treat high-temperature magnetoresistivity prediction as a supervised learning problem based on the full field-dependent curves, rather than predicting only a few scalar summaries. We benchmark multiple regression models under a unified evaluation protocol, then use the best-performing model to extrapolate magnetoresistivity to temperatures above the measurement limit. Importantly, the extrapolated temperature dependence is also used to estimate the Curie temperature, and the predicted behavior is checked for physical consistency using normalized representations (e.g., trends versus

). This combined curve-level prediction, extrapolation, and

estimation provides a device-relevant surrogate modeling workflow that reduces the need for technically challenging high-temperature experiments.

This study leverages advanced machine learning models, including Support Vector Regression (SVR), Random Forest Regression (RFR), and Neural Networks (NN), to analyze and predict the magnetoresistive behavior of

(Permalloy) monolayers. By employing these sophisticated models, we aim to generate accurate predictions of magnetoresistivity at temperatures exceeding 350 °C, a range that is typically inaccessible through conventional experimental methods [14,15]. The integration of ML models in our approach not only enhances predictive accuracy but also enables more precise estimation of critical material properties, such as the

[16,17]. These predictive insights are expected to play a crucial role in advancing the application of Permalloy in next-generation technologies, including high-density information storage and spintronic devices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Techniques

The 5 nm-thick

(Permalloy) films were deposited onto a 3-inch single-crystal Si wafer with its native

oxide layer preserved (prepared in-house by Recep Sahingoz, Yozgat Bozok University, Yozgat, Türkiye.). Films with an individual thickness of 5 nm are deposited under high-vacuum conditions using magnetron sputtering. The as-deposit films were 50–60 mm long and

wide. The samples were thoroughly cleaned with acetone and alcohol prior to further processing to remove surface impurities.

The films were then cut into

pieces for measurement. Electrical contacts were established by coating the sample corners with silver paint and attaching copper wires [18]. Resistance was measured using the Van der Pauw technique, where a constant current (10–100 mA) was applied in-plane via a constant current source, and the corresponding voltage was measured using a digital voltmeter. The Helmholtz coils were driven by a bipolar power supply to generate the magnetic field.

Magnetic measurements were performed using the Lake Shore Hall Effect Measurement System (HEMS) in 30 steps over the temperature range of 25 °C to 350 °C [19]. Hall coefficients and resistance at each temperature were obtained by reversing the current direction and using all possible contact configurations [20,21]. Temperature-dependent magnetic measurements were carried out on

-thick

(Permalloy) films deposited under vacuum on

[22,23]. An external magnetic field of was applied to the sample at each temperature. Resistance changes with applied magnetic field and temperature were measured at each temperature, as shown in Figure 1.

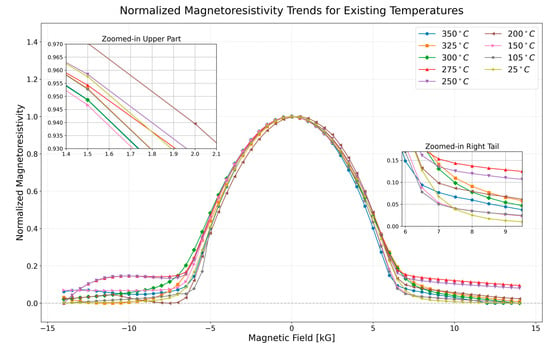

Figure 1.

This plot illustrates the normalized magnetoresistivity trends of

at various existing temperatures ranging from 25 °C to 350 °C. The data shows the dependence of magnetoresistivity on the applied magnetic field across these temperatures. The zoomed-in sections highlight specific regions where differences in magnetoresistivity behavior.

In Figure 1, temperatures were kept constant during the experiment. For example, magnetoresistance measurements were made by changing the magnetic field, while the temperature was fixed at 250 °C [24]. It can be seen in the normalized graphs that the magnetoresistivity values show considerable differences [25]. It is well known that changes in resistivity arise from the material’s composition, geometry, and external factors such as temperature, stress, and pressure, as discussed in similar studies [26]. The temperature was kept constant during the application of the magnetic field. Separate magnetic measurements were taken for each temperature value and presented in the same graph [27].

The magnetization of the material is inversely proportional to the temperature. Magnetization decreases with temperature and disappears at the

, where the material becomes paramagnetic. This phenomenon is known as the Curie–Weiss law in ferromagnetic materials [9]. Even though the sample temperature is constant under the applied magnetic field, the observed resistance change is due to changes in Hall mobility and carrier density [5].

In the absence of a magnetic field, the apparent carrier density decreases with increasing temperature, whereas the Hall mobility increases at higher temperatures. At 25 °C,

is approximately

; this falls to

by 350 °C. Meanwhile, the Hall mobility rises from

at 250 °C to

at 350 °C [28]. These characteristics differ from those typical in ordinary metals (where carrier density is approximately stable and the Hall mobility typically decreases with higher temperature owing to phonon scattering). Instead, these behaviors arise from the interplay of the ordinary and anomalous Hall effects (AHEs) in ferromagnetic

. When the AHE contribution (scaling with magnetization) dominates, it counteracts the ordinary Hall voltage, resulting in an apparent overestimation of carrier density.

When the temperature rises while the magnetization also falls, the effect of the AHE is minimized, exposing the intrinsic carrier density which seems to decline. The increase in

is mainly attributed to the remaining carriers experiencing reduced scattering in the near-paramagnetic regime, even though phonon scattering increases.

In summary, the observed decrease in carrier density and increase in the Hall mobility at elevated temperatures are explained by the weakening anomalous Hall contribution and prevailing scattering mechanisms, rather than actual variations in carrier density or reduced phonon scattering.

2.2. Machine Learning Methodology

This study applies several machine learning (ML) models, including Support Vector Regression (SVR), Random Forest Regression (RFR), Decision Tree Regression, Neural Networks (NN), Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), and Linear Regression, to predict magnetoresistivity and estimate critical temperatures such as the

. These models are selected for their ability to model non-linear relationships and to extend predictions beyond the experimental temperature range. This section details the architectures, key parameters, configurations for each model, and the crucial role of synthetic data generation.

SVR captures non-linear dependencies in the data using a radial basis function (RBF) kernel. The model is configured with three key hyperparameters: the regularization parameter (), the kernel coefficient (), and the

-insensitive margin. Here, based on systematic tuning, the hyperparameters

, kernel width

, and

were selected. Specifically, grid searches and cross-validation were performed: a lower

(e.g., 1) was observed to underfit (high bias, producing smoother predictions that missed curvature), whereas a very high

(e.g., 100) overfit the noise (high variance, capturing small fluctuations that hurt generalization).

gave the best balance between bias and variance on validation sets. For the kernel parameter, we found

optimal; a larger

(such as 1.0) made the SVR local, fitting individual points tightly but failing to generalize (similar to overfitting), while a much smaller

(e.g., 0.01) made it global (almost linear). The chosen

allowed the SVR to capture the broad non-linear trend without chasing high-frequency noise. The parameter

, controlling the tolerance for the fit error, was set to

(for normalized resistivity values ~0–1), allowing minor deviations to be ignored and improving robustness. Using a significantly larger

(e.g., 0.1) slightly degraded accuracy (as the model would ignore small but systematic variations), while a smaller

(e.g., 0.001) did not noticeably improve accuracy but made training slower. With these optimized hyperparameters, the SVR achieved prediction accuracy almost on par with RFR.

RFR operates as an ensemble learning technique, constructing 400 decision trees trained on bootstrapped subsets of data and features. A distinct prediction is made for each tree.

Inference is determined by the ensemble output, which is defined as the average prediction from all the trees. This process is able to effectively preserve complex non-linear interactions between magnetoresistivity and magnetic field while reducing model variability and preventing overfitting. With the noise-augmented training scheme as seen above, the relatively high number of estimators () ensures the model stability against noisy inputs.

In contrast, in decision tree regression, the input data is compartmentalized using a single hierarchical structure through the iterative selection of optimal feature thresholds. This methodology is characterized by high interpretability and clearly defined decision logic, making it suitable for exploratory analysis. However, when applied to small or moderately sized datasets, it is particularly prone to overfitting, resulting in the capture of noise rather than the true signal. Consequently, while decision trees may demonstrate efficacy in training data, their capacity for generalization to unseen data is frequently suboptimal. Notwithstanding this limitation, decision tree regression remains a valuable baseline for comparing the performance of more robust ensemble methods, such as random forests.

In order to learn non-linear mappings from magnetic field to magnetoresistivity, NN were implemented as deep feedforward architectures. Four dense layers make up the enhanced NN architecture: 512 neurons for the input layer, 256 and 128 neurons for the hidden layers, and an output layer at the end. Dropout layers with rates of 0.4 and 0.3 are used to avoid overfitting, and all hidden layers introduce non-linearity using the ReLU activation function. To stabilize training, batch normalization is added after the initial dense layer. In order to minimize the mean squared error loss, the model is trained using the Adam optimizer at a learning rate of 0.0001. To avoid overfitting and enhance generalization, adaptive learning rate reduction (factor = 0.6, patience = 150) and early stopping (patience = 200) are used.

GPR offers a probabilistic modeling approach that can not only provide point predictions but also measures of uncertainty. Hyperparameters were optimized with up to 30 restarts to overcome local minima in the likelihood landscape. Normalized targets were utilized to learn the model that was regularized with an

noise term. GPR demonstrated the ability to interpolate within the training range and supplied predictive uncertainty where it is extrapolated that rendered the method highly useful for the calculation of confidence intervals in sparse or noisy spaces.

Linear Regression serves as a baseline model for evaluating the linearity of the relationship between temperature, magnetic field, and magnetoresistivity. While computationally efficient, it is insufficient to capture the complex, non-linear interactions in the dataset, highlighting the need for more advanced techniques.

Synthetic data generation plays a critical role in enhancing the robustness and generalizability of the machine learning models applied in this study. Gaussian noise is introduced to the experimental data to simulate the variability often encountered in real-world measurements. Additionally, synthetic magnetoresistivity values are computed for temperatures beyond the experimental range using the magnetization model

, where

and

are fitted parameters derived from the experimental data. These model predictions are further smoothed using Gaussian filtering to minimize abrupt variations while retaining key trends. This approach ensures that the ML models train on a broader spectrum of conditions, facilitating improved extrapolation and predictive accuracy for unseen temperature and magnetic field values. After augmentation, the training pool contained 50% synthetic data.

The dataset consists of 300 measurements collected in a temperature range of 25 °C to 350 °C and a magnetic field of

. These data points are divided into 70% for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing. Cross-validation is performed to ensure model generalizability, and hyperparameter optimization is performed for SVR, RFR, NN, and GPR to fine-tune their performance. Although the dataset is modest, the magnetoresistivity exhibits a structured response for each temperature it is approximately Gaussian like in the intermediate field range, while showing clear and systematic deviations in the high field tail. Moreover, the temperature evolution follows a physically constrained trend that can be approximated by

, which supports stable learning and enables estimation of

. This structure reduces the amount of data required to learn robust patterns, but the tail discrepancies indicate that a single simple parametric form is insufficient across the full field range. Therefore, ML is employed to learn a global surrogate model that captures both Gaussian like core and the non-Gaussian tail behavior, and to support extrapolation beyond the experimental temperature limit.

Although many regression algorithms exit, we intentionally focus on a compact set of widely used approaches that cover complementary modeling strategies. This supports the main aim of the paper, which is to perform a controlled comparison under identical preprocessing, data splitting, and evaluation metrics. For reproducibility, all hyperparameters and training settings are reported so that readers can regenerate the results. The next section presents the comparative performance and discusses the predictive behavior of each method.

3. Results and Discussion

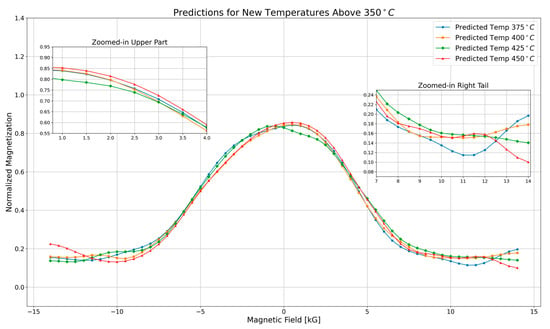

The behavior of the MR data, as shown in Figure 2, demonstrates an almost perfect Gaussian pattern in the central and intermediate regions of the magnetic field range. This consistency underscores the quality of the dataset and the robustness of the machine learning models. However, in the tail regions, discrepancies between the magnetoresistivity curves become more pronounced for different temperature values, which is a common feature in magnetic systems as they approach magnetic saturation.

Figure 2.

Predictions for new temperatures above 350 °C. This plot shows the predicted magnetoresistivity for temperatures above 350 °C The zoomed-in sections highlight the upper part and right tail of the curve.

As magnetic saturation effects dominate in the tail regions, the magnetoresistive sensitivity is reduced, leading to the observed deviations. These deviations do not undermine the overall fit or predictive accuracy of the models in the primary and intermediate regions but rather highlight the physical limitations and complexities of magnetoresistive behavior at extreme magnetic field values. This transition from regular Gaussian behavior to saturation effects provides valuable insights into the material’s magnetoresistive properties, which are critical for understanding its performance across different regimes.

To extend the understanding of the material’s properties beyond the experimentally measured range, ML techniques were employed to analyze the dataset of magnetoresistivity as a function of temperature and magnetic field. The dataset, comprising measurements across a temperature range of 25–350 °C and magnetic fields up to

, was used to train several ML models [10]. These models included regression techniques, which were trained to predict magnetoresistivity beyond the experimental limits [8].

The ML models were evaluated using metrics such as Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and the

score to assess predictive accuracy [29]. To summarize the temperature-wise robustness of the two best-performing models, we report the average and standard deviation of their scores across the temperature steps listed in Table 1 and Table 2. Over this range, Random Forest Regressor achieves an average

score of

, while Support Vector Regressor yields

; consistently, the average MSE values in Table 1 are

for Random Forest and

for SVR. Since the magnetoresistivity curves are dominated by a Gaussian-like profile, even small gains in overall agreement are valuable for preserving the full curve shape; therefore, Random Forest is adopted as the preferred model for high-temperature extrapolative predictions beyond the experimental window [30,31].

Table 1.

MSE Scores of Different Models for Various Temperatures (°C).

Table 2.

Scores of Different Models for Various Temperatures (°C).

The predictions plot in Figure 2 illustrates the variation in normalized magnetization as a function of the magnetic field at temperatures exceeding

(,

,

, and

). Each curve represents a specific temperature and follows a Gaussian-like profile, peaking at zero magnetic field and symmetrically decreasing as the field strength increases. As temperature increases, magnetization decreases, which is expected due to thermal agitation reducing magnetic alignment. The

curve (red) consistently exhibits the lowest magnetization values, while the

curve (blue) maintains the highest values across the field range.

The zoomed-in upper region, covering the

to

range, provides a closer look at how magnetization decreases with increasing magnetic field. The curves follow a smooth downward trend, with higher-temperature curves lying below lower-temperature ones. This gradual separation of the curves confirms the expected temperature-dependent decline in magnetization, with no abrupt changes in behavior.

The zoomed-in right tail, spanning

to

, highlights magnetization behavior at high magnetic fields. In this region, magnetization values are generally low, but temperature-driven variations cause slight deviations from the Gaussian shape. The 450 °C curve (red) reaches the lowest magnetization values, reflecting stronger thermal effects at higher temperatures. Despite these differences, all curves stabilize at low magnetization values, suggesting a reduced sensitivity to the magnetic field at elevated temperatures, where thermal fluctuations dominate.

Using the refined models, predictions were made for magnetoresistivity at temperatures significantly higher than

, specifically at

,

,

, and

. These predictions provide insights into the behavior of the material at higher temperatures, which are challenging to achieve in standard laboratory conditions [32]. The plots reveal that as the temperature increases beyond

, the predicted magnetoresistivity values continue to follow the expected trend, demonstrating the models’ capability to extrapolate beyond the experimentally available data [33].

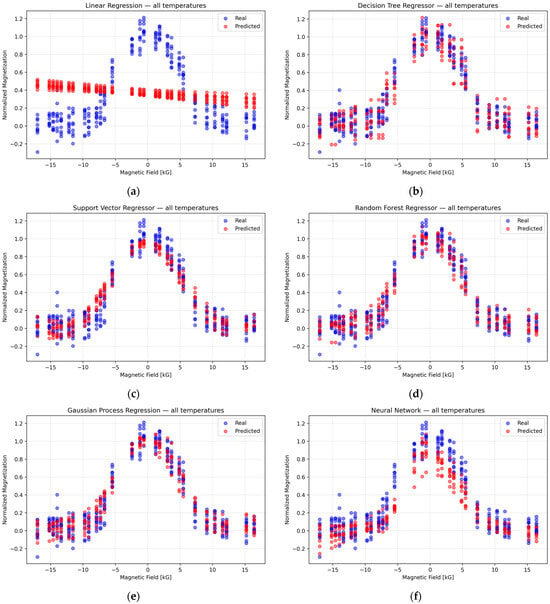

The real vs. predicted values for different ML models at

are shown in Figure 3. This comparison highlights the performance of various models, with the RFR model providing the most accurate predictions. The scatter plot demonstrates a strong alignment between the predicted and actual values for the RFR, while other models show larger deviations, indicating the superior predictive power of the Random Forest model in this scenario [34,35,36].

Figure 3.

Real (blue) vs. Predicted (red) values at 25 °C shows the different ML models. Subplots correspond to: (a) Linear Regression, (b) Decision Tree Regressor, (c) Support Vector Regressor, (d) Random Forest Regressor, (e) Gaussian Process Regression, and (f) Neural Network.

Importantly, the Random Forest Regression (RFR) model did not merely achieve high predictive accuracy—it also captured meaningful physical trends inherent in the data. Specifically, the model recognized that increasing the temperature generally raises the material’s baseline resistivity, a consequence of enhanced scattering at higher

, while applying a higher magnetic field lowers the resistivity by suppressing magnetic scattering. In other words, it successfully reflected the well-known magnetoresistive behavior where an external field reduces resistivity (negative magnetoresistance) by aligning magnetic moments and thereby reducing spin-disorder scattering [37].

These trends are consistent with established physics: near the

(where spins become disordered), one typically observes a strong negative magnetoresistance (i.e., a significant drop in resistivity under applied field), whereas at low temperatures (deep in the ferromagnetic phase with ordered spins), the magnetoresistive effect is much weaker [37].

The key point is that the RFR’s predictions respect known physical behavior (e.g., no unphysical spikes or trends), indicating that the model learned underlying dependencies rather than spurious correlations. In effect, the RFR operates as an implicit physics-based model for resistivity as a function of temperature and field. Its learned mapping can be interpreted as effectively capturing separate contributions of temperature and magnetic field, for instance:

where

is a baseline resistivity increasing with temperature (reflecting temperature-dependent scattering processes), and

is a field-dependent component associated with spin-disorder scattering, which decreases as the field

increases.

Physically,

represents the resistivity in the absence of magnetic scattering (e.g., due to lattice or impurity scattering), while

represents the additional resistivity from spin disorder, which is suppressed by an external magnetic field [38]. This form is analogous to Matthiessen’s rule—where total resistivity is approximately the sum of independent contributions—and mirrors what is observed in magnetoresistive materials.

Near the

, the spin-disorder contribution

is large (random spins increase resistivity), but a strong enough magnetic field can align the spins and drastically reduce this part of the resistivity [37]. Far below

, the spins are mostly aligned even at zero field, so

is inherently small, and the application of a field yields only a minor resistivity change, consistent with the weaker magnetoresistance observed at low

.

Although this two-component form was not explicitly imposed in the modeling, it was effectively discovered from the training data by the RFR (and, to a lesser extent, the SVR), reflecting the underlying physical relationship. This accounts for the model’s high predictive accuracy and the fact that its predictions conform to established physical laws of magnetoresistivity, thereby lending credibility to its use in analyzing and predicting magnetoresistive behavior.

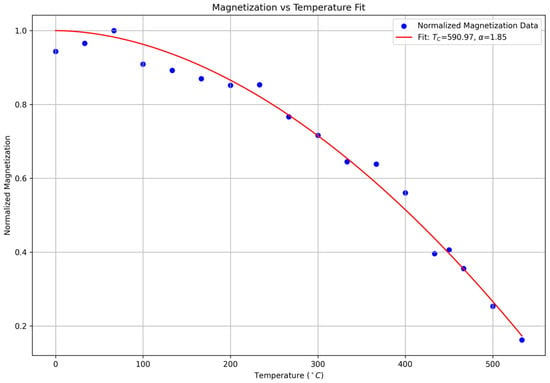

After identifying RFR as the best-performing model, predictions were extended to temperatures above

, beyond the experimental range. Using the predicted magnetoresistivity data,

was determined by fitting the data to the equation

, where

is a fitting parameter. Through this fitting procedure (see Figure 4), the

was estimated to be approximately

demonstrating the success of our methodology and the quality of both the data and model predictions. This result aligns closely with recent studies that report a

of

for

[17], underscoring the precision of the RFR model in predicting critical material properties.

Figure 4.

Magnetoresistivity vs. Temperature Fit. This plot shows the magnetoresistivity data as a function of temperature with a fitted curve, indicating the trend and behavior of magnetoresistivity.

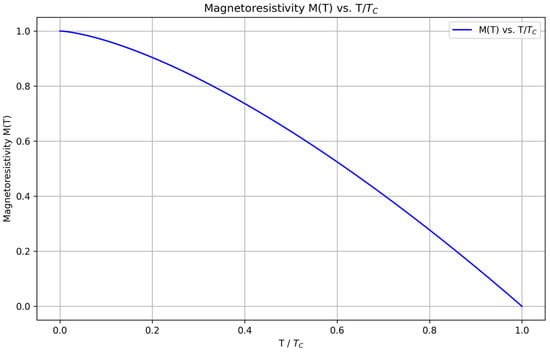

The normalized magnetoresistivity

as a function of the normalized temperature

is shown in Figure 5 [39,40]. This plot is particularly significant as it compares well with the theoretical models and existing literature, indicating that the ML predictions align closely with known physical behaviors [40,41]. The curve demonstrates a smooth decline in magnetoresistivity with increasing normalized temperature, consistent with theoretical expectations, and further validates the model’s accuracy in capturing the material’s intrinsic properties [36].

Figure 5.

Magnetoresistivity

vs.

. The plot shows the normalized magnetoresistivity as a function of the normalized temperature, comparing well with theoretical models and existing literature [40]. This validation against known behaviors underscores the accuracy of the machine learning predictions.

Overall, this advanced analysis provided enhanced predictive models for the material’s magnetoresistive behavior and critical temperature transitions [24]. The Random Forest Regression model, in particular, showcased the potential of machine learning in accurately forecasting material properties beyond experimental temperature limits [11]. The extension of predictions to elevated temperatures underscores the effectiveness of these ML models in offering insights into material behavior under conditions that are challenging to replicate experimentally. This study underscores the significant role that machine learning can play in advancing our understanding of complex material properties and aiding in the development of new technologies [42].

4. Conclusions

This study has demonstrated the significant potential of advanced machine learning techniques in predicting magnetoresistive behavior in

thin films of

at elevated temperatures. By successfully applying models such as Support Vector Regression, Random Forest Regression, and Neural Networks, a robust framework for understanding and predicting material properties beyond conventional experimental limits has been established [43]. The Random Forest Regression model emerged as the most effective, delivering the lowest Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and highest

scores, which indicates high predictive accuracy for magnetoresistivity across a range of temperatures [44]. This suggests that Random Forest Regression is particularly well-suited for handling complex datasets and extracting meaningful insights regarding the material’s behavior [44,45].

The ability of the machine learning models to estimate the

with precision further highlights their potential for identifying critical transitions in magnetic properties [30]. These findings provide a foundation for future research and development in materials science, particularly in designing high-performance materials for applications in spintronic devices and high-density information storage [46]. These predictions can support sensor and device design by estimating high-temperature response trends, helping define operating windows and expected degradation behavior without requiring additional high-temperature measurements. The study underscores the transformative role of machine learning in materials science, offering new avenues for predicting and understanding complex material behaviors. By extending predictions beyond experimentally accessible conditions, machine learning models can significantly accelerate the development of advanced materials and technologies [23].

Future work will focus on refining these models further and exploring their applicability to other magnetic materials, potentially broadening the scope and impact of machine learning in predicting and enhancing material properties [47] such as mobility and carrier density. The continued integration of machine learning techniques in material science research promises to unveil new insights and drive technological advancements in various fields [48].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A., R.S. and T.T.M.; methodology, P.A., R.S. and T.T.M.; software, T.A.; validation, P.A., R.S. and T.T.M.; formal analysis, T.A.; investigation, P.A. and R.S.; resources, T.T.M.; data curation, T.A., F.S.Z., V.B.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, T.A., P.A., R.S. and T.T.M.; writing—review and editing, T.A., P.A., R.S., and T.T.M.; visualization, T.A., F.S.Z., V.B.Z.; supervision, T.T.M.; project administration, R.S. and T.T.M.; funding acquisition, T.T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Yozgat Bozok University BAP, grant number FHD-2024-1475 and State Task of Russian Ministry of Science and Higher Education (North Ossetian State University, FEFN-2024-0002).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the NOSU Laboratory of Physics of Adsorption Phenomena for the provided support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Solin, S.A.; Thio, T.; Hines, D.R.; Heremans, J.J. Enhanced room-temperature magnetoresistance in inhomogeneous magnetic multilayers. Science 2000, 289, 1530–1532. [Google Scholar]

- Wieder, H.H. Hall Generators and Magnetoresistors; Pion: London, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xing, Y.; Li, G.; Deng, D.; Liu, L. Overview on the design of magnetically assisted electrochemical biosensors. Biosensors 2022, 12, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurney, B.A.; Carey, M.; Tsang, C.; Williams, M.; Parkin, S.S.P.; Fontana, R.E.; Grochowski, E.; Pinarbasi, M.; Lin, T.; Mauri, D. Spin valve giant magnetoresistive sensor materials for hard disk drives. In Ultrathin Magnetic Structures IV: Applications of Nanomagnetism; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 149–175. [Google Scholar]

- Biondo, A.; Nascimento, V.P.; Lassri, H.; Passamani, E.C.; Morales, M.A.; Mello, A.; De Biasi, R.S.; Baggio-Saitovitch, E. Structural and magnetic properties of Ni81Fe19/Zr multilayers. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2004, 277, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, S.; Gambardella, P.; Garello, K.; Klein, O.; Sierra, J.; Sinova, J. Spintronic materials. In Encyclopedia of Condensed Matter Physics, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; Volume 2, pp. 159–176. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Sun, K.; Wu, S.; Li, H.F. Crystal, ferromagnetism, and magnetoresistance with sign reversal in a EuAgP semiconductor. J. Mater. 2025, 11, 100853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecharsky, V.K.; Gschneidner, K.A., Jr. Giant magnetocaloric effect in Gd5(Si2Ge2). Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 4494–4497. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.V. Magnetic heat pumping near room temperature. J. Appl. Phys. 1976, 47, 3673–3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanev, V.; Oses, C.; Kusne, A.G.; Rodriguez, E.; Paglione, J.; Curtarolo, S.; Takeuchi, I. Machine learning modeling of superconducting critical temperature. npj Comput. Mater. 2018, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Court, C.J.; Cole, J.M. Magnetic and superconducting phase diagrams and transition temperatures predicted using text mining and machine learning. npj Comput. Mater. 2020, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, J.J.; Körner, W.; Krugel, G.; Urban, D.F.; Elsässer, C. Compositional optimization of hard-magnetic phases with machine-learning models. Acta Mater. 2018, 153, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Lan, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, E.; Deng, Y.; Wang, K. Switching plasticity in compensated ferrimagnetic multilayers for neuromorphic computing. Chin. Phys. B 2022, 31, 117106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, C.; Yari, P.; Wu, K. Recent advances in magnetoresistance biosensors: A short review. Nano Futures 2023, 7, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.S.; Kim, D.Y. Permeability measurement performance of PHR sensor according to direction of driving current. J. Korean Magn. Soc. 2023, 33, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R News 2002, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yamanoi, K.; Semizu, H.; Nozaki, Y. Enhancement of room-temperature unidirectional spin Hall magnetoresistance by using a ferromagnetic metal with a low Curie temperature. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 106, L140401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning, 8th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.; Ong, S.P.; Hautier, G.; Chen, W.; Richards, W.D.; Dacek, S.; Cholia, S.; Gunter, D.; Skinner, D.; Ceder, G.; et al. The Materials Project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 2013, 1, 011002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzwawy, A.; Piskin, H.; Akdogan, N.; Volmer, M.; Reiss, G.; Marnitz, L.; Moskaltsova, A.; Gurel, O.; Schmalhorst, J.-M. Current trends in planar Hall effect sensors: Evolution, optimization, and applications. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2021, 54, 353002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, L.; Agrawal, A.; Choudhary, A.; Wolverton, C. A general-purpose machine learning framework for predicting properties of inorganic materials. npj Comput. Mater. 2016, 2, 16028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oezer, B.; Piskin, H.; Akdogan, N. Shapeable Planar Hall Sensor With a Stable Sensitivity Under Concave and Convex Bending. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 19, 5493–5498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firkowska, I.; Giannona, S.; Rojas-Chapana, J.A.; Luecke, K.; Brüstle, O.; Giersig, M. Biocompatible nanomaterials and nanodevices promising for biomedical applications. In Nanomaterials for Application in Medicine and Biology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Capar, O.; Yildirim, M.; Cinar, H.; Oksuzoglu, R.M. Influence of deposition technique on growth and resistivity of Ta/NiFe nano films. Acta Crystallogr. A 2009, 65, S208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, A. Magnetoresistance Measurement of Thin Film with Hall Effect Technique. Master’s Thesis, Yozgat Bozok University, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences, Mechatronics Engineering Department, Yozgat, Turkey, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; Bahl, C.R.; Bjørk, R.; Engelbrecht, K.; Nielsen, K.K.; Pryds, N. Materials challenges for high performance magnetocaloric refrigeration devices. Adv. Energy Mater. 2012, 2, 1288–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, M.K.; Montoya, J.H.; Liu, M.; Persson, K.A. High-throughput prediction of the ground-state collinear magnetic order of inorganic materials using density functional theory. npj Comput. Mater. 2019, 5, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Zhu, K.; Freitas, S.C.; Davies, J.E.; Eames, P.; Freitas, P.; Kazakova, O.; Kim, C.G.; Leung, C.W.; Liou, S.H.; et al. Magnetoresistive sensor development roadmap (non-recording applications). IEEE Trans. Magn. 2019, 55, 0800130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskin, H.; Akdogan, N. Interface-induced enhancement of sensitivity in NiFe/Pt/IrMn-based planar Hall sensors with nanoTesla resolution. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2019, 292, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talantsev, A.; Elzwawy, A.; Kim, C.G. Effect of NiFeCr seed and capping layers on exchange bias and planar Hall voltage response of NiFe/Au/IrMn trilayer structures. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 123, 173902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, A.D.; Rizzi, G.; Hansen, M.F. Planar Hall effect bridge sensors with NiFe/Cu/IrMn stack optimized for self-field magnetic bead detection. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 119, 093910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhone, T.D.; Chen, W.; Desai, S.; Torrisi, S.B.; Larson, D.T.; Yacoby, A.; Kaxiras, E. Data-driven studies of magnetic two-dimensional materials. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 72811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, T.Q.; Oh, S.; Kumar, A.S.; Jeong, J.R.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, C.G. Optimization of the multilayer structures for a high field-sensitivity biochip sensor based on the planar Hall effect. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2009, 45, 4518–4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.K. Random decision forests. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Montreal, QC, Canada, 14–16 August 1995; pp. 278–282. [Google Scholar]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, W.; Kim, M.; Ha, J.H.; Zulkifli, N.A.B.; Hong, J.I.; Kim, C.G.; Lee, S. Accurate, hysteresis-free temperature sensor for health monitoring using a magnetic sensor and pristine polymer. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 7885–7889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, T.; Trodahl, H.J.; Granville, S.; Vézian, S.; Natali, F.; Ruck, B.J. Magnetoresistance of epitaxial GdN films. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raquet, B.; Viret, M.; Sondergard, E.; Cespedes, O.; Mamy, R. Electron-magnon scattering and magnetic resistivity in 3d ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 66, 024433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Tomsett, R.; Raghavendra, R.; Harborne, D.; Alzantot, M.; Cerutti, F.; Srivastava, M.; Preece, A.; Julier, S.; Rao, R.M.; et al. Interpretability of deep learning models: A survey of results. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE SmartWorld, Ubiquitous Intelligence & Computing, Advanced & Trusted Computed, Scalable Computing & Communications, Cloud & Big Data Computing, Internet of People and Smart City Innovation (SmartWorld/SCALCOM/UIC/ATC/CBDCom/IOP/SCI), San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–8 August 2017; 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-W. Magnetism and Metallurgy of Soft Magnetic Materials; Courier Corporation: Chelmsford, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer, J.; Schoenholz, S.S.; Riley, P.F.; Vinyals, O.; Dahl, G.E. Neural message passing for quantum chemistry. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; pp. 1263–1272. [Google Scholar]

- Curtarolo, S.; Setyawan, W.; Hart, G.L.; Jahnatek, M.; Chepulskii, R.V.; Taylor, R.H.; Wang, S.; Xue, J.; Yang, K.; Levy, O.; et al. Aflow: An automatic framework for high-throughput materials discovery. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2012, 58, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, C.; Eriksson, O.; Klintenberg, M. Data mining and accelerated electronic structure theory as a tool in the search for new functional materials. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2009, 44, 1042–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyk, S.; Schmidsfeld, A.; Klaeui, M.; Ruediger, U. Magnetotransport effects of ultrathin Ni80Fe20 films probed in situ. New J. Phys. 2010, 12, 013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavarini, E. Solving the strong-correlation problem in materials. La Rivista del Nuovo Cimento 2021, 44, 597–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Sampathkumar, P.; Kumar, P.S.A. Development of a very high sensitivity magnetic field sensor based on planar Hall effect. Measurement 2020, 156, 107590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhun, I.O.; Gerasimenko, A.V.; Ezhov, A.A.; Bezzubov, S.I.; Rodionova, V.V.; Gritsenko, C.A.; Chechenin, N.G. Temperature dependence of magnetization dynamics in Co/IrMn and Co/FeMn exchange biased structures. Magnetochemistry 2023, 9, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobs, A.; Oepen, H.P. Disentangling interface and bulk contributions to the anisotropic magnetoresistance in Pt/Co/Pt sandwiches. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 014426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.