Abstract

The proliferation of user-generated content in today’s digital landscape has further increased dependence on online reviews as a source for decision-making in the hospitality industry. There has been an increasing interest in automating this decision-support mechanism through recommender systems. However, this process often requires a large amount of labelled corpus to train an effective algorithm, necessitating the use of human annotators for developing training data, where this is lacking. Although the manual annotation can be helpful in enriching the training corpus, it can, on the one hand, introduce errors and annotator bias, including subjectivity and cultural bias, which can affect the quality of the data and fairness in the model. This paper examines the alignment of ratings derived from different annotation sources and the original ratings provided by customers, which are treated as the ground truth. The paper compares the predictions from Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) models against ratings assigned by Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) workers. The GPT 4o annotation outputs closely mirror the original ratings, given its strong positive correlation (0.703) with the latter. The GPT-3.5 Turbo and MTurk showed weaker correlations (0.663 and 0.15, respectively) than GPT 4o. The potential cause of the large difference between original ratings and MTurk (largely driven by human perception) lies in the inherent challenges of subjectivity, quantitative bias, and variability in context comprehension. These findings suggest that the use of advanced models such as GPT-4o can significantly reduce the potential bias and variability introduced by Amazon MTurk annotators, thus improving the prediction accuracy of ratings with actual user sentiment as expressed in textual reviews. Moreover, with the per-annotation cost of an LLM shown to be thirty times cheaper than MTurk, our proposed LLM-based textual review annotation approach will be cost-effective for the hospitality industry.

1. Introduction

Consumers are increasingly inclined to obtain additional information about a product/service from online reviews before committing to it [1]. This development highlights the critical role electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) plays in shaping the perceptions and decision-making processes of customers of digital businesses, including businesses in the hospitality sector [2,3,4]. Prospective travellers often rely on firsthand experiences shared on platforms like TripAdvisor, Expedia, and Google to make data-informed decisions about their travel logistics, including accommodations and dining. These online review sites serve as pivotal resources, offering insights into the suitability of travel-related services for individual travellers [5,6].

The concept of eWoM, as discussed by Tsai et al. [7] and defined by Litvin, Goldsmith, and Pan [2], has evolved to replace traditional word-of-mouth testimonials. The vast and varied opinions expressed in online reviews require a significant amount of time for prospective travellers to process them, delaying decision-making. To address these challenges, sentiment analysis has seen extensive research focusing on the analysis of massive data sets of user-generated content [8,9] to identify areas of service improvement and automate the recommendation mechanism. However, in many real-world applications, having access to a large labelled corpus can be impractical [10,11]. As a result of this issue, human annotators have been instrumental for enriching the training data for recommender systems development by providing labels to customer reviews, feedback, and behavioural data. Nevertheless, the quality of the data and fairness of models developed from these data can be impacted by subjectivity and annotator bias [12], resulting in poor representation of review texts using star ratings [13,14]. The misalignment between qualitative reviews and quantitative ratings is largely due to the subjective nature of human judgments [15,16] and/or quantitative bias [17,18]. This research explores the relative suitability of human annotators and large language models (LLMs), such as GPT, for hospitality customer review annotation. Leveraging LLMs, this study seeks to improve the accuracy and reliability of recommender systems for the hospitality sector through the realisation of quality and more objective scoring of user-generated reviews for training the systems. Although text classifications have been performed using traditional machine learning algorithms such as Naive Bayes, the methods are keyword-driven, struggle with nuanced sentiments within texts and cannot cope with zero- or few-shots training as would a pre-trained model such as LLMs [19]. As such, this paper does not consider these models as it will be unfair to compare models that learn from few-shots with models that involve a larger scale of training data. To pursue these goals, the thrust of this paper is to infer a prompt-based approach towards rating of hotel reviews that better maps textual sentiments with numerical star ratings [20,21]. LLM-driven annotation presents a shift in methodology from the traditional or crowdsourced labelling. It enables contextual understanding and semantic generalisation. To the best of our knowledge, there is no existing work that has leveraged these capabilities in providing annotations to reviews within the hospitality domain.

Several researchers have investigated the use of LLMs as alternatives or complements to crowdsourced annotation. However, these works have fundamental differences from this paper. He et al. [22] explored the use of GPT-4o within a crowdsourced pipeline for scholarly text classification. Their findings demonstrate that a hybrid approach involving GPT-4o and a human-annotators has an improved accuracy of 87.5%. However, the paper focused on developing an aggregation strategy rather than direct alignment with user ratings, which can be challenging in the case of 5-star or higher-order ratings. Similarly, Li [23] examined label aggregation quality across several NLP tasks, investigating the usefulness of LLM outputs in enhancing overall annotation reliability. The paper, however, did not investigate user intent or sentiment-specific evaluation. Pavlovic and Poesio [24] critically analysed GPT’s suitability on subjective datasets; however, the authors followed a perspectivist evaluation rather than empirical or quantitative analysis with original user ratings.

Our study investigates users’ sentiments within the hospitality domain, compares GPT-4o and GPT-3.5 Turbo against MTurk using original TripAdvisor ratings as ground truth, and employs statistical measures (correlation, MAE, RMSE, hypothesis testing) to empirically evaluate these approaches to user review annotation tasks. These distinctions underscore our contribution to advancing objective, scalable, and cost-efficient annotation for recommender systems in hospitality. By first establishing the correlation between original textual reviews and user-assigned star ratings, this paper further investigates the consistency and quality of LLM-generated text classifications, comparing them with outputs from MTurk and concluding on best practices for refining recommender systems for the industry through an effective data annotation mechanism.

The key contributions of this paper are summarized as follows.

- The paper provides a comprehensive comparison of sentiment scores from GPT models and human annotators, contributing to the understanding of reliability and consistency in textual annotation based on LLMs;

- presents a statistical direction for comparing the performances of different sentiment annotators, including LLM vs Human, as well as different LLM variants.

2. Literature Review

This section seeks to explore the literature regarding the complexities of consumer reviews, examining the challenges and opportunities they present in refining recommendation systems within the hospitality sector. Online reviews, particularly in the hospitality sector, serve as critical decision-making aids for prospective customers, influencing perceptions and purchase intentions. Platforms such as TripAdvisor, Expedia, and Google aggregate vast amounts of user-generated content, which, while valuable, presents challenges in processing and interpretation due to its unstructured nature. Current practices involve the outsourcing of data annotation tasks to platforms such as MTurk, which can be largely subjective and have been criticised for being capable of perpetuating bias [12]. As a result, researchers have explored the use of Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques for this task. NLP, particularly sentiment analysis, has become a hotbed for researchers aiming to extract insights from textual reviews [8,25,26].

2.1. Traditional Approaches and Their Limitations

Early sentiment analysis approaches relied heavily on lexicon-based methods, as demonstrated by Taboada et al. [27], who investigated the lexicon-based approach for sentiment extraction, stressing the significance of a manually curated dictionary. However, the scope for enhancing this method through additional knowledge sources remains vast. To address this, integrating domain-specific corpora and leveraging machine learning techniques to dynamically update lexicons can significantly improve sentiment detection accuracy.

2.2. Crowdsourced Annotation and Bias Concerns

To address the scarcity of labelled data, crowdsourcing platforms like Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) have been widely adopted for annotation tasks. MTurk offers scalability and cost-effectiveness compared to expert annotation; however, concerns persist regarding annotator bias, subjectivity, and variability in interpretation [12]. Studies such as Stringam and Gerdes Jr. [28] and Racherla et al. [29] revealed discrepancies between numeric ratings and qualitative feedback, highlighting the misalignment between user sentiment and star ratings. Annotator predispositions, cultural context, and task definitions further exacerbate these inconsistencies [15,16]. Therefore, reliance on crowdsourced labels can introduce systematic bias into recommender systems, undermining fairness and accuracy.

2.3. Emergence of LLMs for Annotation

The advent of Large Language Models (LLMs) such as GPT has transformed text annotation practices. Gilardi et al. [30] demonstrated that GPT-3.5 outperforms MTurk in text classification tasks, offering better accuracy and cost efficiency—approximately thirty times cheaper per annotation. However, their study focused on tweets and news articles, leaving domain-specific applications like hospitality largely unexplored. Similarly, Sadiq et al. [20] proposed deep learning frameworks for rating prediction but did not compare AI-driven annotation with human annotators.

Recent works in 2024 have expanded this discourse. He et al. [22] examined GPT-4o within a crowdsourced pipeline for scholarly article annotation, finding that GPT-4o slightly outperformed MTurk (83.6% vs. 81.5%) and that hybrid GPT-crowd approaches achieved the highest accuracy (87.5%). Li [23] investigated label aggregation strategies, concluding that integrating LLM outputs with crowd labels enhances overall quality. Pavlovic and Poesio [24] explored GPT’s effectiveness on subjective datasets, noting strong alignment with human annotations. Azad [31] applied GPT-4o to financial news sentiment analysis, reporting improved accuracy and reduced annotation time compared to human annotators. Roumeliotis et al. [32] evaluated GPT-4o for hotel review sentiment classification, achieving 67% accuracy versus 60.6% for BERT, though their study did not benchmark against crowdsourced methods.

2.4. Gaps and Research Direction

While these studies confirm the potential of LLMs in annotation workflows, several gaps remain. First, most prior research either focuses on general NLP tasks or domains such as finance and scholarly content, with limited attention to hospitality reviews, a domain which produces sentiment and cultural variability. Second, few studies benchmark LLM annotations against original user ratings, which serve as an objective ground truth. Third, comprehensive statistical evaluations involving correlation, error metrics (MAE, MSE, RMSE), and hypothesis testing are rare. This study addresses these gaps by comparing GPT-4o and GPT-3.5 Turbo with MTurk annotations for hospitality reviews. It uses statistical measures to assess alignment, offering insights into the feasibility of LLM-driven annotation as a scalable and bias-mitigating alternative to crowdsourcing.

3. Methodology

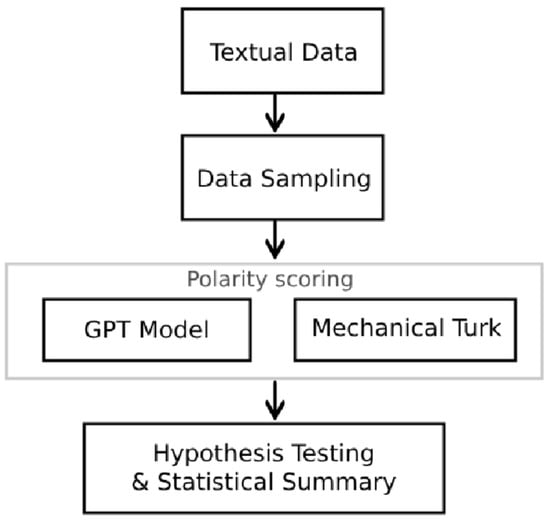

This section explains the methodology used in this research, from random sampling of the data to hypothesis testing and statistical summary, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Methodology.

This study uses a TripAdvisor dataset comprising 20,491 reviews with star ratings on a Likert scale of 1–5 published by Alam et al. [33]. TripAdvisor is characterised by its large volume of global visits and authentic user opinions, supported by user-authentication measures that enhance the credibility of its datasets. Due to the token limitations specific to LLMs like GPT-3.5, which is affected by both the sizes of the context, including the In-Context prompts provided to the LLM, and the generated output [34], 1000 reviews were randomly sampled from the original dataset for analysis, making it ~14,973 token counts for the training. Table 1 shows a sample of the dataset.

Table 1.

Samples of In-Context examples.

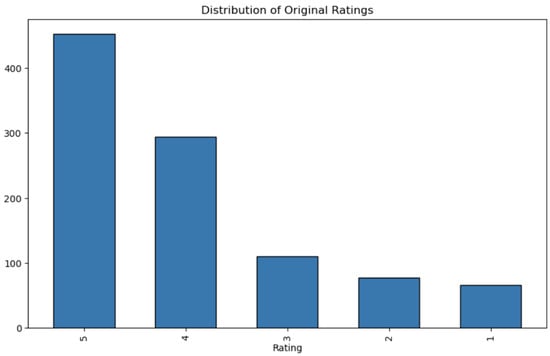

Figure 2 shows a visualisation of the dataset to observe the most recurrent rating given by users. The figure reveals that reviewers assigned a 5-star rating more frequently.

Figure 2.

Frequency of ratings in the reviewed dataset.

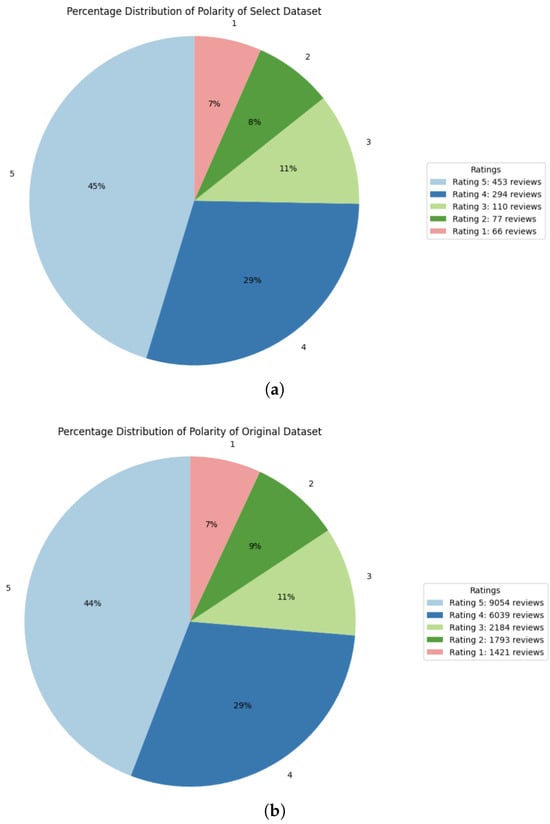

Figure 3a,b show the distribution of the randomly selected dataset and the original dataset. They indicate that the randomly selected data is a good representation of the complete dataset, thus ruling out bias in the selection process. Both datasets exhibit similar distributions across the ratings. The selected dataset had 45% of ratings as 5-star, which is similar to the 44% in the original dataset. Also, 4-star ratings constitute 29% of the ratings in both datasets. The 3-star ratings are identical at 11%, while the 2-star ratings show a minor variance of 1% (8% in the selected dataset compared to 9% in the original). Finally, the 1-star ratings accounted for the remaining 7% in both datasets.

Figure 3.

Data distribution.

3.1. Amazon Mechanical Turk

Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) has been widely used for sentiment analysis [35]. It offers a reliable infrastructure where requesters post HITs that are visible only to qualified workers based on criteria initially established. The workers earn small rewards for completing specific tasks [27,36]. For this project, the selected review was uploaded to Amazon Mechanical Turk, where the reviewers assigned a rating to each text based on the available choices.

Although Amazon Mechanical Turk aims to mitigate subjectivity bias through crowd-sourced ratings, the annotators often provide ratings justified only by the text rather than real experience. This limitation may affect task quality and introduce systematic, contextual, or quantitative bias. According to a study by Paolacci et al. [36], participants often need more oversight and care than those in traditional experiment settings. This difference could impact the accuracy and dependability of data.

The dataset was uploaded to MTurk using the default settings of the MTurk predefined template. The data has 1000 reviews, and each review was annotated by one worker, within an estimated time of about one minute, with a reward of USD 0.04 per task. A worker must hold a Human Intelligence Tasks (HIT) approval rate above 95% and have at least 50 approved HITs. No geographic restrictions were applied. There were no additional attention checks and no aggregation required. Only submissions that met the task requirements were approved, while any low-quality or incomplete responses were rejected.

Large Language Models (GPT 4o and GPT 3.5 Turbo)

This research used GPT 4o and GPT 3.5 Turbo for rating prediction. These LLMs have been pre-trained on terabytes of textual data with 200 billion and 175 billion parameters, respectively, and have been tailored to support a wide range of tasks. A study by Huang et al. [37] provides an exposé into the likelihood of GPT performing subjective tasks that require social judgment and decision-making. Prompt engineering ensures GPT is streamlined to specific domains without compromising its extensive general knowledge base [38,39]. The prompt engineering process must involve a systematic and iterative workflow for making LLMs domain-specific [38]. The crafting of the prompt for the GPT models for this paper followed the iterative process model presented in [38]. Each of the GPT models utilises a prompt containing In-Context examples for the rating task. Qualitative mapping was provided to guide the models’ assignment of ratings to the textual reviews. Table 2 shows the context given to the model through the OpenAI API. The In-Context prompt is a JSON object containing 50 examples, developed from a stratified sampling from the dataset to uniformly represent the different ratings, while the text in the prompt represents each textual review. Following the in-context learning, the model was applied to the 1000 reviews. Table 1 shows a sample of data used in the In-Context prompts.

Table 2.

Prompt for rating by the GPT models.

The LLM-based annotation solutions were implemented using the OpenAI GPT API within Python 3.8.0. To manage token limitations, the 1000 reviews were passed into the LLMs in 10 sets, with each set containing 100 reviews. Prompts for sentiment analysis were crafted to extract scores ranging from very negative to very positive; this made classification direct and clear. The temperature parameter, which controls the randomness of the LLM, was set to 0.1, making the model relatively deterministic [40]. This approach was aimed at examining GPT’s performance under varying conditions, offering insights into whether or not it is appropriate for sentiment analysis tasks.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents the observations from this research, detailing the analysis and obtained results. It also discusses the implications of the findings and how they address the research questions, and provides recommendations for future research.

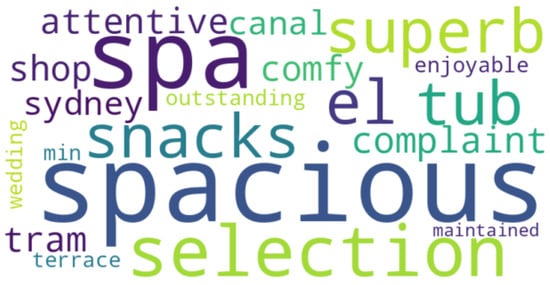

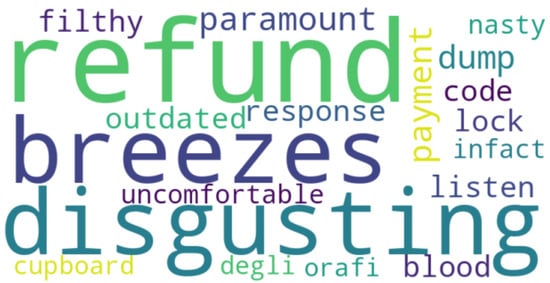

As part of the exploratory data analysis (EDA) and data understanding process, we explored the sentiments in the text data by grouping the reviews into positive (ratings of 4 and 5) and negative (ratings of 1 and 2) examples to visualise key themes within these categories, as shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5, respectively.

Figure 4.

Thematic word cloud of positive sentiments.

Figure 5.

Thematic word cloud of negative sentiments.

4.1. Statistical Analysis

The independent variable of this study is the text review data being analysed, while the dependent variables include the original rating assigned by users, the MTurk rating scores, and the ratings generated by the different GPT models. The aim is to explore how well these sources of ratings align with the customer sentiment expressed in the text. The descriptive data generated for all variables is used to measure the accuracy and reliability of the output of GPT and the MTurk-generated scores against the original ratings. Table 3 shows the distribution of ratings across the different platforms, revealing a clear trend; it is possible to agree with the similarity between the original rating and the GPT 4o, while the distribution of ratings for MTurk and GPT 3.5 Turbo falls between 2 and 3.

Table 3.

Statistical observations of ratings.

Table 4 shows a summary of the descriptive statistics for the original ratings, MTurk ratings, GPT 4o ratings, and GPT 3.5 Turbo ratings.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of ratings.

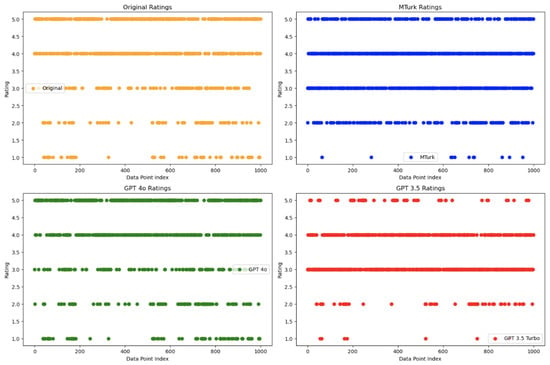

Relying solely on descriptive statistics can sometimes lead to erroneous inferences, as demonstrated by Anscombe’s quartet [41]. Four datasets with identical summary statistics were shown to have vastly different distributions when visualised with scatter plots. This highlights the importance of graphical analysis in understanding dataset dimensionality and revealing details not visible in summary statistics [42,43]. Figure 6 presents scatter plots comparing the spread and density of ratings across platforms. Each plot reveals how sentiment scores are distributed, highlighting similarities and differences in evaluation patterns. We see that most of MTurk and GPT 3.5 Turbo’s ratings are 3 and 4, while Original and GPT 4o have more varied ratings, with a notable concentration around 3, 4, and 5.

Figure 6.

Scatter plot of sentiment scores.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

The hypotheses are tested to examine the reliability of the Amazon worker-assigned ratings and AI-generated scores. The null hypothesis assumes no difference between the elements being observed, while the alternate hypothesis (research hypothesis) proposes a difference in the observed values. Shapiro–Wilk normality tests indicated non-normal distributions for rating differences, justifying the use of non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. If the p-value is less than the significance level ( = 0.05), the null hypothesis is rejected in favour of the alternate hypothesis. However, a ‘statistically non-significant’ result (p-value higher than ) does not necessarily mean no difference exists but, rather, that the observed difference may be due to random chance.

Next, we present the research questions and the statistical tests:

- RQ1: Can the customers’ original ratings of text reviews be accurately represented using GPT models and/or the MTurk workers’ ratings?

Hypothesis (H0).

The mean ratings assigned by customers are the same as the mean ratings from the GPT models and/or the MTurk workers.

Hypothesis (H1).

The mean ratings assigned by customers are significantly different from the mean ratings from the GPT models and/or the MTurk workers.

Both GPT-4o and MTurk differed significantly from original ratings (p = 3.7 × 10−4 and p = 2.5 × 10−8, respectively). However, practical significance contextualises these differences: GPT-4o exhibited a small-to-medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.32), while MTurk showed a medium effect (d = 0.65), indicating greater misalignment, as can be seen in Table 5.

Table 5.

Comparison of statistical metrics for GPT-4o and MTurk.

- RQ2: Do AI-generated (GPT) sentiment scores exhibit a stronger correlation with the original numeric ratings assigned by customers compared to the sentiment scores provided by human MTurk annotators?

Cross-validating the result from RQ1, we compared the original numeric ratings assigned by customers with the sentiment scores from MTurk, GPT 4o, and GPT 3.5 using several statistical measures: the correlation coefficient, Mean Squared Error (MSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and R-squared (R2). These measures help assess how well each set of sentiment scores aligns with the original ratings.

The Spearman correlation coefficient was computed to assess monotonic relationships. GPT-4o achieved r = 0.703 (p < 1 × 10−149); GPT-3.5 scored r = 0.663; and MTurk remained weak, at r = 0.153 (Table 6). These results confirm that GPT models capture ordinal trends better than MTurk.

Table 6.

Results of regression performance.

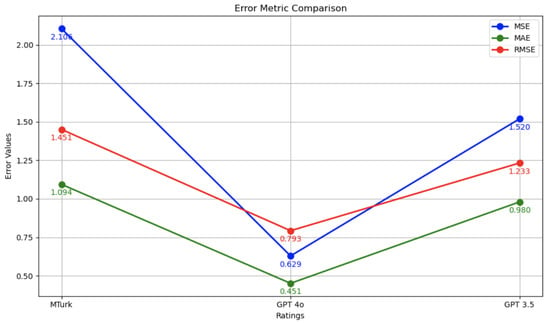

The results of the MAE, MSE, and RMSE comparisons shown in Figure 7 provide insights into how well GPT 4o ratings align with the original ratings given by the users. GPT 4o has the lowest MAE (0.451), MSE (0.629), and RMSE (0.793), indicating that the deviations between the sentiment scores and the original ratings are small compared to GPT 3.5 (MAE: 0.980; MSE: 1.520; RMSE: 1.233) and MTurk (MAE: 1.094; MSE: 2.106; RMSE:1.451). The MAE and MSE further confirm that GPT 4o generates the most accurate scores relative to the original ratings. At the same time, the RMSE shows that it more accurately captures the variability in the original ratings.

Figure 7.

MAE, MSE, and RMSE plot for original ratings vs. MTurk and GPT.

5. Future Directions

While none of the evaluated approaches perfectly replicated the original customer ratings, GPT-4o demonstrated the strongest alignment, achieving a Spearman correlation of 0.703 and the lowest error metrics among all methods. However, this superiority is not merely a statistical observation; it reflects GPT-4o’s enhanced ability to capture nuanced sentiment through contextual and semantic understanding. Unlike MTurk annotators, whose judgments are susceptible to cultural and perceptual biases, GPT-4o leverages large-scale pretraining and In-Context prompting to interpret sentiment consistently. Nevertheless, this advantage introduces its own challenges: prompt design can influence outputs, and reliance on a few examples risks overfitting or systematic bias inherited from training data. GPT-4o is not immune to annotation errors; misinterpretation of sarcasm, idiomatic expressions, or domain-specific terms can lead to incorrect ratings. These limitations underscore the need for hybrid workflows where human oversight validates automated outputs, mitigating risks of hallucinations and goal misalignment.

Beyond technical performance, the findings raise socio-technical and ethical considerations. Automating annotation tasks at scale could disrupt digital labour ecosystems, challenging the sustainability of crowdsourcing platforms. Moreover, unchecked deployment of LLMs may perpetuate algorithmic bias, especially if prompts or training data embed cultural stereotypes. Future research should therefore explore bias auditing frameworks, transparency in prompt engineering, and adversarial testing to ensure fairness and accountability.

Additional directions include sensitivity analysis of GPT outputs under varying temperature settings and a comprehensive cost–benefit evaluation of transitioning from human annotators to LLM-driven workflows. These steps will not only validate the robustness of GPT-based annotation but also inform ethical governance models for the integration of generative AI into decision-support systems.

6. Conclusions

This study evaluated the suitability of large language models (LLMs)—specifically, GPT-4o and GPT-3.5 Turbo—against human MTurk annotatorsfor hospitality review rating prediction. While GPT-4o demonstrated the strongest alignment with original ratings (Spearman r = 0.703) and lower error metrics compared to other methods, these findings should not be interpreted as evidence that LLMs can fully replace human annotators. The observed performance advantage reflects GPT-4o’s ability to leverage contextual and semantic cues, but it does not eliminate risks associated with automated annotation.

Several limitations should be considered for further improvement. First, the analysis revealed non-normal error distributions and residual variability, indicating that GPT-4o, while more consistent than MTurk, can still misclassify, particularly in cases involving sarcasm, idiomatic language, or domain-specific nuances. Second, the reliance on in-context prompting introduces sensitivity to prompt design, which can bias outputs or lead to overfitting. These factors underscore the need for hybrid workflows where human oversight validates automated predictions.

Ethical considerations are equally critical. Automating annotation tasks at scale raises questions about systemic bias embedded in LLM training data, transparency in prompt engineering, and the socio-economic impact on digital labour markets. Without robust bias audits and governance frameworks, replacing human annotators could perpetuate inequities and erode accountability. Future research should therefore prioritise bias detection, adversarial testing, and ethical guidelines for the integration of LLMs into annotation pipelines.

Finally, while cost and speed advantages of GPT-based annotation are compelling, these benefits must be weighed against risks of algorithmic bias and misalignment. Future work should explore sensitivity analysis under varying temperature settings, domain generalisation, and cost–benefit trade-offs in real-world deployments. By addressing these dimensions, the adoption of LLMs for annotation can move from optimistic assumptions to evidence-based, ethically grounded practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.N. and C.P.E.; methodology, P.N.; software, O.A.; validation, E.I., O.A. and C.P.E.; formal analysis, P.N. and O.A.; investigation, O.A.; resources, C.P.E. and E.I.; data curation, P.N.; writing—original draft preparation, P.N.; writing—review and editing, C.P.E. and E.I.; visualization, O.A.; supervision, C.P.E. and E.I.; project administration, E.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

This study uses a TripAdvisor dataset comprising 20,491 reviews with star ratings on a Likert scale of 1–5 published by Alam et al. [33].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, T.; Samaranayake, P.; Cen, X.; Qi, M.; Lan, Y.-C. The impact of online reviews on consumers’ purchasing decisions: Evidence from an eye-tracking study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 865702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S.W.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Pan, B. Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbard, D. The impact of online reviews on hotel performance. J. Mod. Hosp. 2023, 2, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Kishan, K.; Tewari, V. The influence of online reviews on consumer decision-making in the hotel industry. J. Data Acquis. Process. 2023, 38, 2559–2573. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Z. A comparative analysis of major online review platforms: Implications for social media analytics in hospitality and tourism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Ma, Y.; Du, Q.; Xiang, Z.; Fan, W. Role of user-generated photos in online hotel reviews: An analytical approach. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C. Improving text summarization of online hotel reviews with review helpfulness and sentiment. Tour. Manag. 2020, 80, 104122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibeke, E.; Lin, C.; Coe, C.D.; Wyner, A.Z.; Liu, D.; Barawi, M.H.B.; Abd Yusof, N.F. A curated corpus for sentiment-topic analysis. Emot. Sentim. Anal. 2016. Available online: http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2016/workshops/LREC2016Workshop-ESA_Proceedings.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Sun, S.; Luo, C.; Chen, J. A review of natural language processing techniques for opinion mining systems. Inf. Fusion 2017, 36, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Dong, X.; Zheng, L.; Yan, Y.; Yang, Y. A bottom-up clustering approach to unsupervised person re-identification. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2019, 33, 8738–8745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Qin, C.; Ouyang, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Qiu, H.; Chen, L.; Tarroni, G.; Bai, W.; Rueckert, D. Enhancing MR image segmentation with realistic adversarial data augmentation. Med. Image Anal. 2022, 82, 102597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.; Rahman, M.; Kamawal, S.; Toroghi, A.; Raval, A.; Navah, F.; Kazemeini, A. A comprehensive review of recommender systems: Transitioning from theory to practice. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2026, 59, 100849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Kuwatly, H.; Wich, M.; Groh, G. Identifying and measuring annotator bias based on annotators’ demographic characteristics. In Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop on Online Abuse and Harms, Online, 20 November 2020; pp. 184–190. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen, T.S.T.; Barrett, M.; Søgaard, A.; Lassen, D. The sensitivity of annotator bias to task definitions in argument mining. In Proceedings of the 16th Linguistic Annotation Workshop (LAW-XVI) Within LREC2022, Marseille, France, 24 June 2022; pp. 44–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, K. Predicting hotel review helpfulness: The impact of review visibility, and interaction between hotel stars and review ratings. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36 Pt A, 929–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Darpy, D. Rating, review and reputation: How to unlock the hidden value of luxury consumers from digital commerce? J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2020, 35, 1553–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCusker, K.; Gunaydin, S. Research using qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods and choice based on the research. Perfusion 2015, 30, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.; Qureshi, R.; Zahid, A.; Fioresi, J.; Sadak, F.; Saeed, M.; Sapkota, R.; Jain, A.; Zafar, A.; Ul Hassan, A.; et al. Who is responsible? The data, models, users or regulations? Responsible generative AI for a sustainable future. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.08650. [Google Scholar]

- Ezenkwu, C.P.; Ibeke, E.; Iwendi, C. Assessing the capabilities of ChatGPT in recognising customer intent in a small training data scenario. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Advanced Communication and Intelligent Systems (ICACIS 2024), New Delhi, India, 16–17 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sadiq, S. Discrepancy detection between actual user reviews and numeric ratings of Google App Store using deep learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 181, 115111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivia, A. Inconsistencies on TripAdvisor reviews: A unified index between users and sentiment analysis methods. Neurocomputing 2019, 353, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Huang, C.-Y.; Ding, C.-K.C.; Rohatgi, S.; Huang, T.-H.K. If in a Crowdsourced Data Annotation Pipeline, a GPT-4. In Proceedings of the CHI 2024, Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–16 May 2024; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. A Comparative Study on Annotation Quality of Crowdsourcing and LLM via Label Aggregation. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlovic, M.; Poesio, M. Effectiveness of LLMs as Annotators: A Perspectivist Evaluation. In Proceedings of the LREC-COLING 2024, Turin, Italy, 20–25 May 2024; ELRA: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ravi, K.; Ravi, V. A survey on opinion mining and sentiment analysis: Tasks, approaches and applications. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2015, 89, 14–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, S.; Du, K.; Ntalianis, K. Sentiment analysis and deep learning. In Proceedings of the ICSADL 2022, Songkhla, Thailand, 16–17 June 2022; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Taboada, M. Lexicon-based methods for sentiment analysis. Comput. Linguist. 2011, 37, 267–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringam, B.B.; Gerdes, J., Jr. An analysis of word-of-mouse ratings and guest comments of online hotel distribution sites. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 773–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racherla, P.; Connolly, D.J.; Christodoulidou, N. What determines consumers’ ratings of service providers? An exploratory study of online traveler reviews. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2013, 22, 135–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilardi, F.; Alizadeh, M.; Kubli, M. ChatGPT outperforms crowd workers for text-annotation tasks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2305016120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, S. The effectiveness of GPT-4 as financial news annotator versus human annotator in improving the accuracy and performance of sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on MAchine inTelligence for Research & Innovations, Jalandhar, India, 1–3 September 2023; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Roumeliotis, K.I.; Tselikas, N.D.; Nasiopoulos, D.K. Leveraging large language models in tourism: A comparative study of the latest GPT Omni models and BERT NLP for customer review classification and sentiment analysis. Information 2024, 15, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.H.; Ryu, W.-J.; Lee, S. Joint multi-grain topic sentiment: Modeling semantic aspects for online reviews. Inf. Sci. 2016, 339, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Han, T.; Ma, S.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Tian, J.; He, H.; Li, A.; He, M.; Liu, Z.; et al. Summary of ChatGPT-related research and perspective towards the future of large language models. Meta-Radiology 2023, 1, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Jussà, M.R.; Grivolla, J.; Mellebeek, B.; Benavent, F.; Codina, J.; Banchs, R.E. Using annotations on Mechanical Turk to perform supervised polarity classification of Spanish customer comments. Inf. Sci. 2014, 275, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolacci, G.; Chandler, J.; Ipeirotis, P.G. Running experiments on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2010, 5, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Kwak, H.; An, J. Is ChatGPT better than human annotators? Potential and limitations of ChatGPT in explaining implicit hate speech. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.07736. [Google Scholar]

- Ezenkwu, C.P. Towards expert systems for improved customer services using ChatGPT as an inference engine. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Digital Applications, Transformation & Economy (ICDATE), Miri, Malaysia, 14–16 July 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Muresanu, A.I.; Han, Z.; Paster, K.; Pitis, S.; Chan, H.; Ba, J. Large language models are human-level prompt engineers. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.01910. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J. The Temperature Feature of ChatGPT: Modifying creativity for clinical research. JMIR Hum. Factors 2024, 11, e53559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anscombe, F.J. Graphs in statistical analysis. Am. Stat. 1973, 27, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousselet, G.A.; Pernet, C.R.; Wilcox, R.R. Beyond differences in means: Robust graphical methods to compare two groups in neuroscience. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2017, 46, 1738–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulrow, E.J. The visual display of quantitative information. Technometrics 2002, 44, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).