Abstract

Text matching, as a core technology of natural language processing, plays a key role in tasks such as question-and-answer systems and information retrieval. In recent years, the development of neural networks, attention mechanisms, and large-scale language models has significantly contributed to the advancement of text-matching technology. However, the rapid development of the field also poses challenges in fully understanding the overall impact of these technological improvements. This paper aims to provide a concise, yet in-depth, overview of the field of text matching, sorting out the main ideas, problems, and solutions for text-matching methods based on statistical methods and neural networks, as well as delving into matching methods based on large-scale language models, and discussing the related configurations, API applications, datasets, and evaluation methods. In addition, this paper outlines the applications and classifications of text matching in specific domains and discusses the current open problems that are being faced and future research directions, to provide useful references for further developments in the field.

1. Introduction

Text matching aims at determining whether two sentences are semantically identical or not, and it plays a key role in domains such as question and answer, information retrieval, and summarization. Early text-matching techniques relied heavily on statistical methods such as the longest common substring (LCS) [1], edit distance [2], Jaro similarity [3], dice coefficient [4], and Jaccard method [5]. These methods have the advantage of quantifiable similarity and have been widely used in several scenarios such as text comparison, spell-checking, gene sequence analysis, and recommender systems. They have a solid theoretical foundation that ensures the accuracy and reliability of similarity computation. However, there are some limitations to these methods, such as the high computational complexity of some of them, their sensitivity to input data, and limited semantic understanding. These methods include the bag-of-words model [6], distributed representation [7], matrix decomposition [8], etc., and their common advantage is that they can transform textual data into numerical representations, which is easy for computer processing. At the same time, they are flexible and scalable and can adapt to different needs and data characteristics. However, these methods still have limitations in deep semantic understanding and may not be able to accurately capture complex meanings and contextual information. In addition, the computational complexity is high when dealing with large-scale corpora, and the parameters need to be adjusted and optimized to obtain the best results. In recent years, with the rise of neural network technology, recursive neural network-based matching methods such as LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) [9], BiLSTM(Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory) [10], and BiGRU (Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit) [11] have gradually emerged. These methods share common features in terms of sequence modeling, gating mechanism, state transfer, bi-directional processing, and optimization and training. They can fully utilize the information in sequences, capture long-term dependencies, and show excellent performance in handling complex tasks.

However, these methods often ignore the interaction information between the statements to be matched during the matching process, thus limiting the further improvement of the matching effect. To solve this problem, researchers have proposed sentence semantic interaction matching methods, such as DSSTM [12], DRCN [13], DRr-Net [14], and BiMPM [15]. The core of these methods lies in capturing the semantic interaction features between sentences using deep learning models and optimizing the matching task through an end-to-end training approach. These methods usually have a high matching performance and are flexible enough to be applied to different types of matching tasks. However, these methods are usually sensitive to noise and ambiguity and are data-dependent, with limited generalization capability. With the continuous development of technology, knowledge graph and graph neural network matching methods are gradually emerging. These methods show unique advantages in dealing with graph-structured data, can effectively extract features and perform representation learning, and are suitable for dealing with complex relationships. At the same time, they also show a strong flexibility and representation capability and can be adapted to different types of matching tasks. However, these methods also face some challenges, such as high computational complexity and sensitivity to data quality and structure. In recent years, advances in deep learning methods, the availability of large amounts of computational resources, and the accumulation of large amounts of training data have driven the development of techniques such as neural networks, attention mechanisms, and Transformer [16] language models. These research results have further advanced the development of big language models. Big language models utilize neural networks containing billions of parameters, trained on massive amounts of unlabeled text data through self-supervised learning methods. Often pre-trained on large corpora from the web, these models can learn complex patterns, linguistic subtleties, and connections. This technique has also significantly advanced the development of sentence matching, with models such as BERT [17], Span-BERT [18], Roberta [19], XLNet [20], the GPT family [21,22,23,24], and PANGU-Σ [25] demonstrating superior performance in sentence-matching tasks.

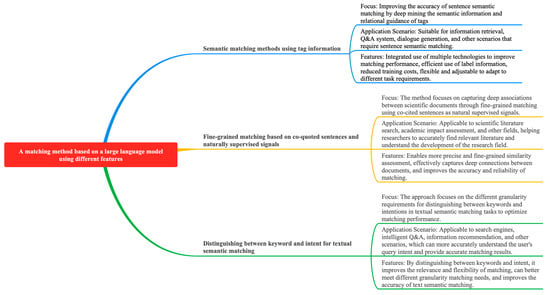

The large language model described above lays the cornerstone for sentence semantic matching and focuses on exploring generic strategies for encoding text sequences. In text matching, previous approaches typically add a simple categorization target through fine-tuning and perform direct text comparisons by processing each word. However, this approach neglects the utilization of the semantic information of tags, as well as the differences in the granularity of multilevel matching in the sentence content. To address this problem, researchers have proposed a matching method based on a large language model that combines different features, which is capable of digging deeper into the semantic-matching information at different levels of granularity in tags [26] and sentences [27,28,29]. These studies have made important contributions to the development of the text-matching field. Therefore, a comprehensive and reliable evaluation of text-matching methods is particularly important. Although a few studies [30,31,32] have demonstrated the potential and advantages of some of the matching methods, there is still a relative paucity of studies that comprehensively review the recent advances, possibilities, and limitations of these methods.

In addition, researchers have extensively explored multiple aspects of text matching in several studies [30,31,32], but these studies often lack in-depth analyses of the core ideas, specific implementations, problems, and their solutions for matching methods. Also, there are a few exhaustive discussions on hardware configurations, training details, performance evaluation metrics, datasets, and evaluation methods, as well as applications in specific domains of matching methods. Therefore, there is an urgent need to delve into these key aspects to understand and advance the development of text-matching techniques more comprehensively. Given this, this paper aims to take a comprehensive look at the existing review studies, reveal their shortcomings, and explore, understand, and evaluate text-matching methods in depth. Our research will cover core concepts, implementation strategies, challenges encountered, and solutions for matching methods, while focusing on their required hardware configurations and training processes. In addition, we will compare the performance of different metrics for different tasks, analyze the choice of datasets and evaluation methods, and explore the practical applications of matching methods in specific domains. Finally, this paper will also examine the current open problems and challenges faced by text-matching methods, to provide directions and suggestions for future research and promote further breakthroughs in text-matching technology.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows: (1) The core ideas, implementation methods, problems, and solutions for text-matching methods are thoroughly outlined and analyzed. (2) The hardware configuration requirements and training process of the matching method are analyzed in depth. (3) A detailed comparison of the performance of text-matching models with different metrics for different tasks is presented. (4) The datasets used for training and evaluating the matching model are comprehensively sorted out and analyzed. (5) The interface of the text-matching model in practical applications is summarized. (6) Application cases of matching models in specific domains are analyzed in detail. (7) Various current unsolved problems, challenges, and future research directions faced by matching methods are surveyed, aiming to provide useful references and insights to promote the development of the field.

The chapter structure of this study includes an overview of some leading research comparisons in Section 2. Then, the literature collection and review strategy is presented in Section 3. Then, in Section 4 we check, review, and analyze 121 top conference and journal papers published from 1912 to 2024. In Section 5, we focus on the core of the matching approach, exploring in detail its main ideas, implementation methods required hardware configurations, and training process, and comparing the performance of text-matching models with different metrics for different tasks. Through this section, readers can gain a deeper understanding of the operation mechanism and the advantages and disadvantages of the matching method. Section 6 then focuses on analyzing and summarizing the datasets used for training and evaluating the matching models and their evaluation methods, providing guidance and a reference for researchers in practice. Section 7 further explores the application of matching models in specific domains, demonstrating their practical application value and effectiveness through case studies. Section 8 reveals the various outstanding issues and challenges that the matching method is currently facing, and it stimulates the reader to think about future research directions. In Section 9, we delve into the future research directions of matching methods, providing useful insights and suggestions for researchers. Finally, in Section 10, we summarize the research in this paper.

2. Literature Review

Text matching, as an important branch in the field of artificial intelligence, has made a remarkable development in recent years. To deeply explore and evaluate its capabilities, numerous researchers have carried out extensive research work. Researchers from different disciplinary backgrounds have contributed many innovative ideas to text-matching methods, demonstrating their remarkable progress and diverse application prospects. Overall, these studies have collectively contributed to the continuous advancement in text-matching techniques. As shown in Table 1, Asha S et al. [30] provided a comprehensive review of string-matching methods based on artificial intelligence techniques, focusing on the application of key techniques such as neural networks, graph models, attention mechanisms, reinforcement learning, and generative models. The study not only demonstrates the advantages and potential of these techniques in practical applications but also deeply analyzes the challenges faced and indicates future research directions. In addition, Hu W et al. [31] provided an exhaustive review of neural network-based short text matching algorithms in recent years. They introduced models based on representation and word interaction in detail and analyzed the applicable scenarios of each algorithm in depth, providing a quick-start guide to short text matching for beginners. Meanwhile, Wang J et al. [32] systematically sorted out the current research status of text similarity measurement, deeply analyzed the advantages and disadvantages of existing methods, and constructed a more comprehensive classification and description system. The study provides an in-depth discussion of the two dimensions of text distance and text representation, summarizes the development trend of text similarity measurement, and provides valuable references for related research and applications.

Table 1.

Comparison between leading studies.

Table 1 compares in detail the research content and focus of different review papers in the field of text matching. Among them, the application of large language models in text matching, the core ideas of matching methods and their implementation, problems and solutions, and logical relationships have been explored to different degrees. However, the studies by Asha S [30] and Hu W et al. [31] are deficient in some key areas, such as the lack of a detailed overview and analysis of the matching methodology, an in-depth comparison of hardware configurations and training details, a comprehensive evaluation of the performance of the text-matching model under different tasks, and a comprehensive overview of the dataset, evaluation metrics, and interfaces of the model application. Similarly, the study by Wang J et al. [32] fails to cover many of these aspects. In contrast, our paper remedies these shortcomings by comprehensively exploring the core idea of the text-matching approach and its methodology, problems and solutions, hardware configurations, and training details, and comparing the performance of text-matching models for different tasks using different metrics. In addition, this study provides an overview of the datasets, evaluation metrics, and application programming interfaces for text-matching models, and analyzes in detail the application of the models in specific domains. Through these comprehensive studies and analyses, this thesis provides richer and deeper insights into the research and applications in the field of text matching.

As can be seen from the above analysis, most of the past studies have focused on limited areas of semantic matching, such as technology overviews, matching distance calculations, and evaluation tools. However, this study is committed to overcoming these limitations by providing an in-depth and comprehensive analysis of the above aspects, thus better revealing the strengths and weaknesses of the matching methods based on large language models. The core of this study is to deeply analyze the core idea of the matching method, compare the impact of different hardware configurations and training details on performance, evaluate the effectiveness of the text-matching model in various tasks with different metrics, outline the application program interface of the text-matching model, and explore its application in specific domains. By providing exhaustive information, this study aims to be an important reference resource for sentence-matching researchers. In addition, this study addresses open issues in sentence-matching methods, such as bottlenecks in the application of large models to sentence-matching tasks, model-training efficiency issues, interference between claim comprehension and non-matching information, the handling of key detail facts, and the challenges of dataset diversity and balance. The study highlights these key challenges and indicates directions and valuable resources for future research for sentence-matching researchers, to provide new ideas for solving these open problems.

3. Data Collection

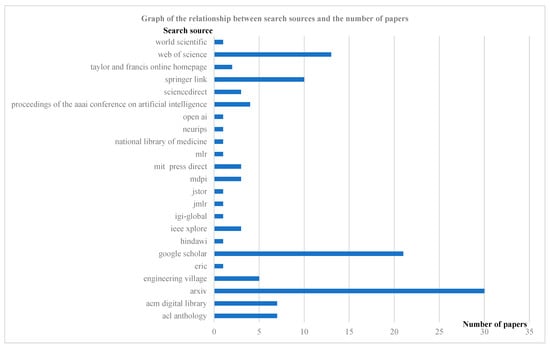

The literature review strategy consisted of three steps. First, the scope of the study was identified as text matching in NLP. The second step was to select widely recognized and high-quality literature search databases, such as Web of Science, Engineering Village, IEEE, SpringerLink, etc., and use Google Scholar for the literature search. Keywords include text matching, large language modeling, question and answer and retrieval, named entity recognition, named entity disambiguation, author names disambiguation, and historical documentation. In the third step, 121 articles related to text matching were collected for a full-text review and used for text-matching research and summarization. (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Graph of search sources versus number of papers.

4. Summary of Results

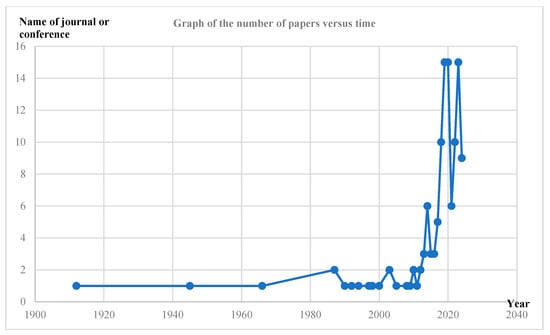

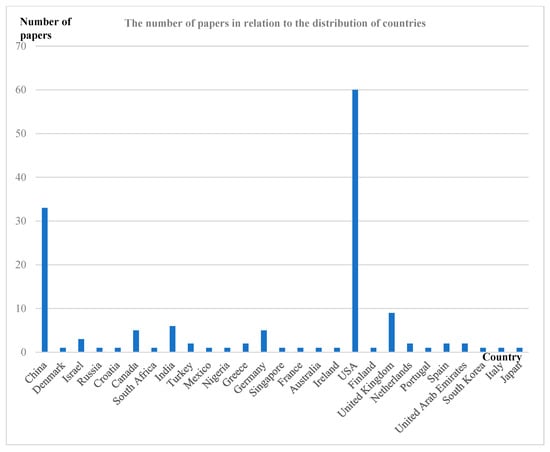

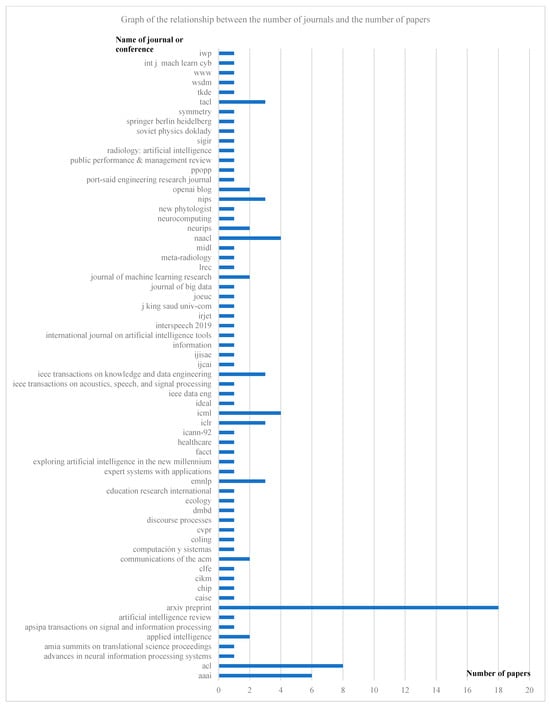

Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 illustrate the distribution of articles related to text-matching survey research by year, region, and journal. As can be seen in Figure 2, this type of research has shown a significant growth trend since around 2015. Previous studies have also shown that the field of machine vision is facing a similar situation, which is closely related to the increased demand for AI technology in various industries, the improved performance of computer hardware, and the rapid development and dissemination of AI. From Figure 3, it can be observed that the US has the highest number of papers published in text-matching-related research, accounting for 49.59% of the total. This is followed by China, the UK, India, Germany, and Canada. Other countries such as the United Arab Emirates, South Korea, Israel, and South Africa have published corresponding articles. Finally, Figure 4 shows the 65 top conferences and journals that were sources of the literature, mainly focusing on the field of natural language processing, where 18 papers from 2017 to 2024 were selected in the Arxiv preprint. Eight papers from 2014 to 2022 were selected for ACL. 6 papers from 2016 to 2022 were selected for AAAI.

Figure 2.

Graph of number of papers vs. time.

Figure 3.

Graph of the number of papers in relation to the distribution of countries.

Figure 4.

Graph of journals versus number of conferences and papers.

5. Text-Matching Methods

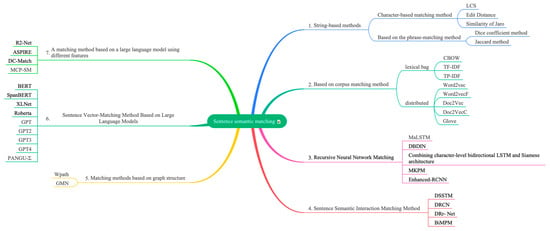

Text-matching methods cover several different techniques and strategies, each with its unique application scenarios and advantages. These methods can be broadly classified into the following categories: string-based methods, corpus-based methods, recursive neural network matching methods, sentence semantic interaction matching, matching methods based on graph structures, matching methods based on pre-trained language models, and matching methods based on large language models utilizing different features, as shown in Figure 5. String-based methods usually match by comparing the similarity of characters or strings in text and are suitable for simple and straightforward text comparison tasks. Corpus-based methods, on the other hand, rely on large-scale corpora to extract similarities and relationships between texts and achieve matching through statistical and probabilistic models. Recursive neural network matching methods utilize neural networks to deeply understand and represent the text, capturing the hierarchical information of the text through recursive structures to achieve a complex semantic matching. Sentence semantic interaction matching, on the other hand, emphasizes the semantic interaction and understanding between sentences, and improves the matching effect by modeling the interaction between sentences. Graph structure-based matching methods utilize graph theory knowledge to represent and compare texts, and match by capturing structural information in the text. In contrast, sentence vector-matching methods based on large language models improve the matching performance by capturing the deep semantic features of the text with the help of pre-trained language models from large-scale corpora. Among the large language model-based matching methods utilizing different features, the matching methods utilizing tagged semantic information consider the effect of tags or metadata on text matching and enhance the accuracy of matching by introducing additional semantic information. The fine-grained matching method pays more attention to the detailed information in the text and realizes fine-grained matching by accurately capturing the subtle differences between texts.

Figure 5.

Matching method overview diagram.

5.1. Text-Matching Methods

String similarity metrics are an important text analysis tool that can be used to measure the degree of similarity between two text strings, which in turn supports string matching and comparison. Among these metrics, the cosine similarity measure is popular for its simplicity and effectiveness. The cosine similarity metric calculates the similarity between two texts based on the cosine of the angle of the vectors [33], which consists of calculating the dot product of the two vectors, calculating the modulus (i.e., length) of the respective vectors, and dividing the dot product by the product of the moduli; the result is the cosine of the angle, i.e., the similarity score. However, the cosine similarity is not sensitive to the magnitude of the value, does not apply to non-positive spaces, and is affected by the feature scale. To improve its performance, methods such as adjusting the cosine similarity (e.g., centering the values), using other similarity measures (e.g., Pearson’s correlation coefficient), or feature normalization can be adopted to improve the accuracy and applicability of the similarity calculation.

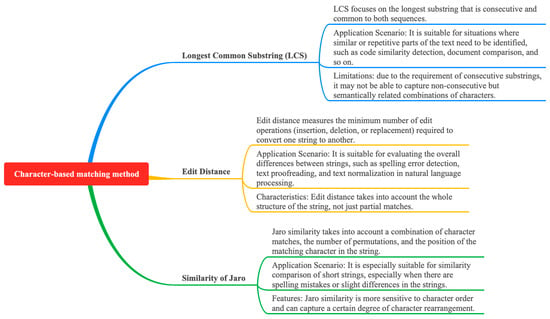

Several variants or improved forms of cosine similarity have also been proposed by researchers to address specific needs in different scenarios. These variants include weighted cosine similarity [34] and soft cosine similarity [35], among others. Weighted cosine similarity allows different weights to be assigned to each feature dimension to reflect the importance of different features; soft cosine similarity reduces the weight of high-frequency words in text similarity computation by introducing a nonlinear transformation. In addition, depending on the basic unit of division, string-matching-based methods can be divided into two main categories: character-based matching and phrase-based matching. These methods are illustrated in Figure 6, and their key ideas, methods, key issues, and corresponding solutions are summarized in detail in Table 2. These string-matching-based methods provide a rich set of tools and options for text analysis and processing to meet the needs of different application scenarios.

Figure 6.

Overview of logical relationships based on character-matching methods.

Table 2.

Overview of key ideas, methods, key issues, and solutions for string-matching-based approaches.

Longest common substring (LCS) [1], edit distance [2], and Jaro similarity [3] are three methods based on character matching, which have their own focuses and logically complement each other. LCS focuses on consecutive character matching, edit distance measures the overall conversion cost, and Jaro similarity considers character matching, permutation, and positional information. These methods constitute a diversified toolbox for character-matching analysis, which can be flexibly selected and combined according to the application scenarios. With the development of natural language processing technology, more new methods may emerge in the future to meet more complex text-processing needs.

The longest common substring matching algorithm iteratively determines the length of the longest common substring by calculating a threshold array to find the optimal solution, and it reduces the running time by optimizing the set operation [1]. For large-scale data and complex scenarios, parallelization and distributed processing schemes are proposed to improve the scalability and processing speed of the algorithm. Edit distance constructs binary codes by analogy to correct optimal code problems such as wounding, insertion, and inversion [2]. However, it faces problems such as a limited error correction capability, difficulty in recognizing insertion errors, and high computational complexity in inversion error detection and computation. The solutions include adopting more powerful error correction codes, designing synchronization markers, utilizing checksum methods, and optimizing the algorithm implementation. Jaro similarity is measured by a string comparator and optimized by the record-joining method of the FellegiSunter model, which uses the Jaro method to handle string discrepancies and adjust the matching weights [3]. However, the database quality and string comparator parameter settings affect the matching accuracy. We propose strategies such as data cleaning, increasing the sample diversity, and an adaptive string comparator to optimize the performance and accuracy of the matching algorithm.

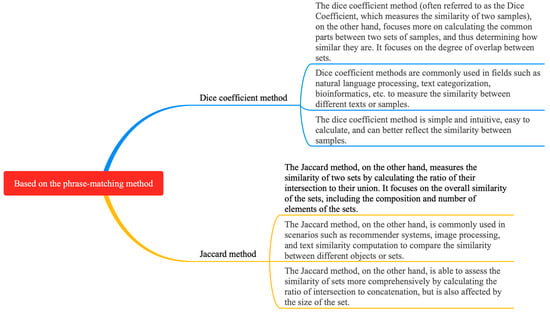

Phrase-based matching methods include the dice coefficient method [4] and the Jaccard method [5], as shown in Figure 7. The difference between phrase-based matching methods and character-based matching methods is that the basic unit of processing is the phrase. The dice coefficient method in the phrase-based matching method is mainly used to measure the similarity of two samples. However, this method has limitations in dealing with synonyms, contextual information, and large-scale text. For this reason, context-based word embedding models, deep learning methods, and the optimization of data structures, in combination with approximation algorithms, are used to improve the accuracy and efficiency of the similarity assessment. In the field of natural language processing, it is often used to calculate the similarity of two text phrases. The principle of the dice coefficient is based on the similarity measure of sets [4], which is calculated as follows:

where |X ∩ Y| denotes the size of the intersection of X and Y, and |X| and |Y| denotes the size (i.e., number of elements) of X and Y, respectively. The value domain of the dice coefficient is [0, 1]. When two samples are identical, the dice coefficient is 1; when two samples have no intersection, the dice coefficient is 0. Therefore, the larger the dice coefficient, the more similar the two samples are.

dice coefficient = (2 × |X ∩ Y|)/(|X| + |Y|)

Figure 7.

Overview of logical relationships based on phrase-matching methods.

The Jaccard method in the phrase-based matching method is an algorithm used to calculate the similarity of two sets [5]. Its principle is based on the Jaccard coefficient in set theory, which measures the similarity of two sets by calculating the ratio of their intersection and concatenation. Specifically, given two sets A and B, the Jaccard coefficient is defined as the number of elements in the intersection of A and B divided by the number of elements in the concatenation of A and B. However, the method suffers from the problems of being insensitive to sparse text and ignoring word weights and word order. To improve these problems, it is possible to convert word items into word embedding vectors, add word item weights, and for these to be used in combination with other similarity measures to evaluate text semantic similarity more accurately. Its calculation formula is as follows:

where |A ∩ B| denotes the number of intersection elements of sets A and B, and |A ∪ B| denotes the number of concatenation elements of sets A and B. The Jaccard coefficient has a value range of [0, 1], with larger values indicating that the two sets are more similar.

Jaccard(A, B) = |A ∩ B|/|A ∪ B|

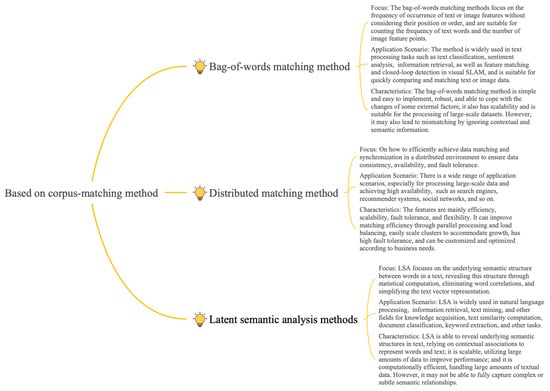

5.2. Based on the Corpus-Matching Method

Typical methods for corpus-based matching include bag-of-words modeling such as BOW (bag of words), TF-IDF (term frequency-inverse document frequency), distributed representation, and matrix decomposition methods such as LSA (Latent Semantic Analysis), as shown in Figure 8. The key ideas, methods, key problems, and solutions for typical methods of corpus-based matching are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 8.

Corpus-based matching method.

Table 3.

Overview of key ideas, methods, key problems, and solutions of corpus-based matching methods.

Typical approaches to bag-of-words models are BOW [6], TF-IDF [40], and its variant TP-IDF [42]. The bag-of-words model reduces the text to a collection of lexical frequencies, ignores the order and semantics, and is not precise enough for complex text processing. To improve this model, the n-gram model can be used to consider word combination and order, or word embedding technology can be used to capture semantic relationships, so as to enhance the accuracy and performance of text processing.TF-IDF is an important method in the bag-of-words model, which evaluates the importance of words by combining the word frequency and the inverse document frequency, and extracts key information effectively. However, IDF simplified processing may lead to information loss and the underestimation of similar text keywords. For improvement, text representation techniques such as TF-IWF, or ones combined with word embedding models, can be used to represent text content more comprehensively.TP-IDF is an improvement to the traditional TF-IDF method, which combines the positional information of the word items in the document to assess the word importance more accurately, and it is especially suitable for short text analysis. However, it also faces the challenges of defining location factors, stability, noise interference, and computational complexity in its application. By optimizing the position factor definition, combining other text features, deactivating word processing, and algorithm optimization, TP-IDF can improve the efficiency and accuracy of text data processing.

Distributed approaches cover a range of techniques based on dense vector representations [51], such as Word2vec [7], Word2VecF [45], Doc2Vec [46], Doc2VecC [47], and glove [39]. These techniques represent vectors using fixed-size arrays where each element contains a specific value, thus embedding words, documents, or other entities into a high-dimensional space to capture their rich semantic information. Dense vector representations have been widely used in natural language processing tasks such as text categorization, sentiment analysis, recommender systems, etc., because of their simplicity, intuitiveness, and ease of processing. Word2Vec, as a representative of this, achieves a quantitative representation of semantics by mapping words into continuous vectors through neural networks. However, CBOW and Skip-gram, as their main training methods, have problems such as ignoring word order, multiple meanings of one word, and OOV words. To overcome these limitations, researchers have introduced dynamic word vectors and character embeddings or pre-trained language models, in conjunction with models such as RNN, Transformer, etc., to significantly improve the performance and applicability of Word2Vec. Word2VecF is a customized version of Word2Vec that allows users to customize word embeddings by supplying word–context tuples, to be able to exploit global context information. However, it also faces challenges such as data quality, parameter tuning, and computational resources. To overcome these challenges, researchers have adopted technical approaches such as data cleaning, parameter optimization, distributed computing, and model integration to improve the accuracy and efficiency of word embeddings.

The glove model, on the other hand, captures global statistics by constructing co-occurrence matrices to represent the word vectors, but it suffers from the challenges of dealing with rare words, missing local contexts, and high computational complexity. To improve the performance and utility of the glove, researchers introduced an external knowledge base, incorporated a local context approach, and used optimized algorithms and model structures, as well as a distributed computing framework for training. These improvements make the glove model more efficient and accurate in natural language processing tasks.

The core idea of LSA (Latent Semantic Analysis) is to reveal the implicit semantics in the text by mapping the high-dimensional document space to the low-dimensional latent semantic space [8]. It uses methods such as singular value decomposition to realize this process. However, LSA suffers from semantic representation limitations, sensitivity to noise, and computational complexity. To improve the performance, it can be combined with other semantic representation methods, data preprocessing, and cleaning, as well as the optimization of the algorithm and computational efficiency. Through these measures, LSA can be utilized more effectively for text processing and semantic analysis.

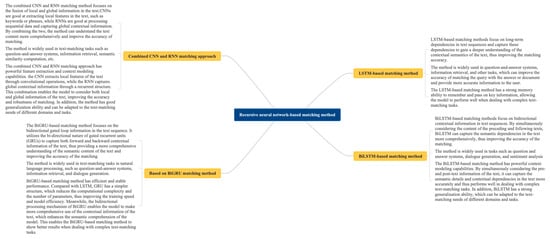

5.3. Recursive Neural Network-Based Matching Method

Neural network architectures are at the heart of deep learning models and determine how the model processes input data and generate output. These architectures consist of multiple layers and neurons that learn patterns and features in the data by adjusting the weights of connections between neurons. Common neural network architectures include feed-forward neural networks, recurrent neural networks, and convolutional neural networks, each of which is suitable for different data-processing needs. When dealing with sentence-matching tasks, specific architectures such as twin networks and interactive networks can efficiently compute the similarity between sentences. In addition, the attention mechanism [52] improves the efficiency and accuracy of processing complex data by simulating the allocation of human visual attention, enabling the model to selectively focus on specific parts of the input data. Recursive neural network matching methods, such as those based on LSTM, BiLSTM, and BiGRU, are shown in Figure 9. They further combine neural network architectures and attention mechanisms to provide powerful tools for processing sequential data. By properly designing and adapting these architectures, deep learning models can be constructed to adapt to various tasks. The key ideas, methods, key issues, and solutions for the recursive neural network matching approach are summarized in Table 4.

Figure 9.

Overview of logical relationships of recursive neural network-based matching methods.

Table 4.

Overview of key ideas, methods, key problems, and solutions for recursive neural matching-based approaches.

The MaLSTM model predicts semantic similarity by capturing the core meaning of sentences through LSTM and fixed-size vectors [9]. However, there are problems with low-frequency vocabulary processing, capturing complex semantic relations, and computational efficiency. This study proposes strategies such as data preprocessing, introducing an attention mechanism, optimizing the model structure, and utilizing pre-trained models to improve the model’s effectiveness on the sentence similarity learning task. The DBDIN model [55] achieves precise semantic matching between sentences through two-way interaction and an attention mechanism but faces the problems of a high consumption of computational resources, difficulty in capturing complex semantics, and limited generalization ability. Optimizing the model structure, introducing contextual information and pre-training models, and combining multiple loss functions and regularization techniques can improve the performance and stability of DBDIN on the sentence similarity learning task. The deep learning model proposed by Neculoiu P et al. combines a character-level bi-directional LSTM and Siamese architecture [10] to learn character sequence similarity efficiently but suffers from high complexity, and it may ignore overall semantic information and show a lack of robustness. Optimizing the performance can be accomplished by simplifying the model structure, introducing high-level semantic information, cleaning the data, and incorporating regularization techniques.

Lu X et al. [11] proposed a sentence-matching method based on multiple keyword pair matching, which uses the sentence pair attention mechanism to filter keyword pairs and model their semantic information, to accurately express semantics and avoid redundancy and noise. However, the method still has limitations in keyword pair selection and complex semantic processing. The accuracy and application scope of sentence matching can be improved by introducing advanced keyword extraction techniques, extending the processing power of the model, and optimizing the algorithm. Peng S et al. proposed the Enhanced-RCNN model [57], which fuses a multilayer CNN and attention-based RNN to improve the accuracy and efficiency of sentence similarity learning. However, the model still has challenges in handling complex semantics, generalization ability, and computational resources. The model performance can be improved by introducing new techniques, optimizing models and algorithms, and expanding the dataset.

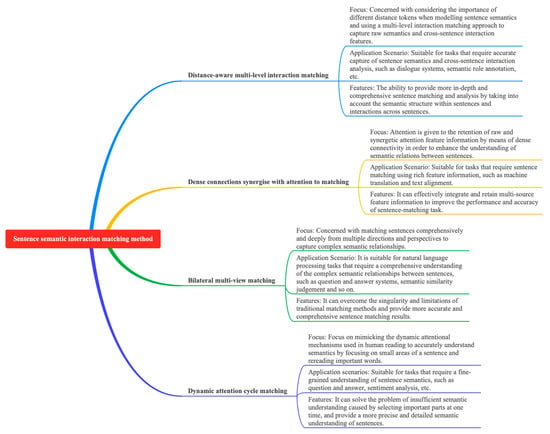

5.4. Semantic Interaction Matching Methods

Typical models of semantic interactive matching methods include DSSTM [12], DRCN [13], DRr- Net [14], and BiMPM [15], as shown in Figure 10. As shown in Table 5, this study outlines the key ideas, methods, key issues, and solutions for interaction matching methods.

Figure 10.

Overview of logical relations of sentence semantic interaction matching methods.

Table 5.

Overview of key ideas, methods, key problems, and solutions for interaction matching methods.

Deng Y et al. proposed constructing a DSSTM model [12], which utilizes distance-aware self-attention and multilevel matching to enhance sentence semantic matching accuracy but suffers from computational inefficiency and insufficient deep semantic capture, and it is suggested to optimize the model structure and introduce complex semantic representations to improve the performance. Kim S et al. [13] proposed a novel recurrent neural network architecture, which enhances inter-sentence semantic comprehension through dense connectivity and collaborative attention but suffers from rising feature dimensions’ computational complexity and information loss. It is suggested to optimize the feature selection and compression techniques to improve the model performance. Zhang K et al. [14] proposed a sentence semantic matching method that simulates the dynamic attention mechanism of human reading, which improves comprehension comprehensiveness and accuracy but is limited by the quality of training data and preprocessing. It is suggested to optimize the training strategy, increase the diversity of data, improve the preprocessing techniques, and combine linguistic knowledge to enhance the model performance. The BiMPM model proposed by Wang Z et al. [15] improves the performance of NLP tasks through multi-view matching but suffers from complexity and cross-domain or cross-language adaptability problems. Optimizing the model structure and introducing the attention mechanism are schemes that help to improve the model’s accuracy and adaptability.

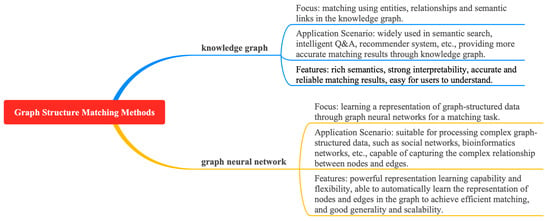

5.5. Matching Methods Based on Graph Structure

Typical approaches for matching based on graph structures include knowledge graphs and graph neural networks, as shown in Figure 11. This study also outlines the key ideas, methods, key problems, and solutions for graph-based matching methods, as shown in Table 6.

Figure 11.

Overview of logical relationships of graph structure matching methods.

Table 6.

Overview of key ideas, methods, key problems, and solutions based on graph matching methods.

Zhu G et al. proposed the wpath method [59] to measure semantic similarity by combining path length and information content in a knowledge graph. However, there are problems of graph sparsity, computational complexity, and information content limitations. It is suggested to introduce multi-source paths, optimize the graph structure and algorithm, integrate other semantic features, and adjust the weights to improve the applicability and performance of the wpath method. Chen L et al. proposed a GMN framework to improve the accuracy of Chinese short text matching through multi-granularity input and attention graph matching [60], but there are problems such as high complexity and poor interpretability. It is suggested to optimize the graph matching mechanism, enhance interpretability, reduce model dependency, and use data enhancement and automation tools to improve performance.

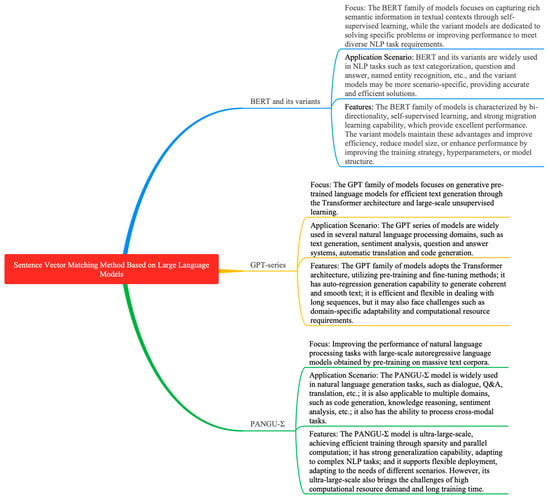

5.6. Sentence Vector Matching Method Based on Large Language Models

The embedding technique is an important means to transform textual data, such as words, phrases, or sentences, into fixed dimensional vector representations. These vectors not only contain the basic features of the text but are also rich in semantic information, enabling similar words or sentences to have similar positions in the vector space. In the sentence-matching task, the embedding technique is particularly important because it can transform sentences into computable vector representations, thus facilitating our subsequent similarity calculations and comparisons. Among the many embedding methods, models such as Word2Vec, Glove, and BERT have shown excellent performance. They can capture the contextual information of words and generate semantically rich vector representations, providing strong support for NLP (Natural Language Processing) tasks such as sentence matching. In recent years, significant progress has been made in sentence vector matching methods based on large language models. Models such as BERT [17], Span BERT [18], XLNet [19], Roberta [20], GPT family, and PANGU-Σ [25] are among the leaders. As shown in Figure 12, these models have their features and advantages in sentence vector representation. This study delves into the key ideas and methods of these models, as well as the key problems and solutions encountered in practical applications. As shown in Table 7, we provide an overview of the performance of these models, aiming to help readers better understand their principles and applicable scenarios. Through this study, we can see that sentence vector matching methods based on large language models have become one of the important research directions in the field of NLP. These models not only improve the accuracy and efficiency of sentence matching but also provide rich feature representations for subsequent NLP tasks. With the continuous development of technology, we have reason to believe that these models will play an even more important role in future NLP research.

Figure 12.

Overview of logical relations of sentence vector matching method based on large language model.

Table 7.

Overview of key ideas, methods, key issues, and solutions based on large language model.

BERT [17], proposed by Devlin J et al., uses a bi-directional encoder and self-attention mechanism to capture deep semantic and contextual information of a text, which are pre-trained and fine-tuned to achieve efficient applications. However, there are problems such as a high consumption of computational resources and insufficient learning. Optimizing the algorithm and model structure, increasing the amount of data, and exploring new text-processing techniques can improve the performance and generalization of BERT. SpanBERT [18], proposed by Joshi M et al., improves the text representation by masking successive text segments and predicting the content, but it suffers from the problems of context-dependence and the stochasticity of the masking strategy. It is suggested to introduce an adaptive masking mechanism and balance multiple strategies, combining stable training and unsupervised pre-training tasks to improve the model’s stability and generalization ability. XLNet [19], proposed by Yang Z et al., improves text quality and accuracy by introducing causal and bi-directional contextual modeling and aligned language modeling, and although there are problems such as computational complexity, these can be solved by techniques such as an approximate attention mechanism to improve the model efficiency and performance. Liu Y et al. presented the study of Roberta [20] and pointed out that the hyperparameters and the amount of training data in BERT’s pre-training are crucial to the performance, and by replicating and adjusting the pre-training process, it was found that the performance of BERT could rival that of the subsequent models. However, there are problems such as an incomplete hyperparameter search and computational resource limitation. It is suggested to expand the search scope, use distributed computing, and combine advanced models and techniques to optimize its performance.

The GPT [21] model overcomes BERT’s limitations through an autoregressive structure and expanded vocabulary to generate coherent text sequences, which are applicable to a variety of NLP tasks. It faces the problems of data bias, dialog consistency, and long text processing, but these can be solved by diversifying the data, introducing a dialog history, and segmentation. GPT [21] possesses the advantages of text generation and still faces the challenges of long text processing and training complexity.

The GPT [21] model proposed by Radford A et al. is widely used and provides high-quality and adaptable text generation, but the results are inaccurate and inconsistent. It performs poorly on rare data. GPT2 [22] improves the text quality and diversity by increasing the model size and training data but still faces challenges. It can be improved by a bi-directional encoder, model compression, etc., and addressing concerns about security and ethical issues. GPT2 [22], proposed by Radford A et al., enhances the quality and diversity of text generation but suffers from a lack of accuracy and consistency. GPT3 [23], proposed by Brown T et al., further enhances its generation capability by increasing the size and training data, and it supports multi-tasking. However, it faces challenges such as a high cost and a lack of common sense and reasoning ability. An optimization of the model and attention to ethical norms are needed. GPT4 [24], proposed by Achiam J et al., demonstrates high intelligence, handles complex problems, and accepts multimodal inputs, but suffers from problems such as hallucinations and inference errors. It can be improved by adding more data, human intervention, and model updating. Meanwhile, optimizing its algorithms and quality control inputs can improve its accuracy and reliability; checking the data quality, increasing the dataset and number of training sessions, and using integrated learning techniques can also reduce the error rate and bias. The PANGU-Σ [25] model proposed by Ren X et al. adopts a scalable architecture and a distributed training system, and utilizes massive corpus in pre-training to improve the performance of NLP, but it faces challenges such as sparse architecture design, accurate feedback acquisition, and other challenges. These can be solved by optimizing its algorithms, improving data annotation and self-supervised learning, designing multimodal fusion networks, model compression, and optimization.

5.7. A Matching Method Based on a Large Language Model Utilizing Different Features

Typical models of matching methods based on large language models utilizing different features include the R2-Net [26], ASPIRE [27], DC-Match [28], and MCP-SM [29] models, as shown in Figure 13. This study outlines the key ideas, methods, key issues, and solutions for their fine-grained matching approaches, as shown in Table 8.

Figure 13.

Overview of the logical relationships of fine-grained matching methods.

Table 8.

Summary of key ideas, methods, key problems, and solutions for fine-grained matching methods.

Zhang K et al. [26] proposed to improve sentence semantic matching accuracy by deep mining label semantic information and relational guidance, combining global and local coding and self-supervised relational classification tasks to achieve significant results, but there are problems of model complexity, label quality, and hyperparameter tuning. Model compression, distributed computing, semi-supervised learning or migration learning, and automatic hyperparameter-tuning tools are suggested to solve these problems and improve the model’s performance and utility. Mysore S et al. [27] studied to achieve a fine-grained similarity assessment among scientific documents by utilizing paper co-citation sentences as a naturally supervised signal. The ASPIRE [27] method constructs multi-vector models to capture fine-grained matching at the sentence level but faces data sparsity, noise, and computational complexity issues. Data enhancement and filtering techniques can be used to improve its generalization ability, optimize the model structure, and reduce the complexity by using parallel computation to deal with a large-scale scientific corpus efficiently. Zou Y et al. study proposed a DC-Match [28] training strategy for different granularity requirements of query statements in text semantic matching tasks, which optimizes the matching performance by distinguishing between keywords and intent. However, DC-Match may face remote supervision information accuracy, computational complexity, and flexibility issues. It is suggested to optimize the resource selection and quality, adopt advanced remote supervision techniques, optimize the algorithm and model structure, utilize distributed computing techniques, and introduce domain-adaptive techniques to improve performance and adaptability. Yao D et al. propose a semantic matching method based on multi-concept parsing to reduce the dependence on traditional named entity recognition and improve the flexibility and accuracy of multilingual semantic matching. The method constructs a multi-concept parsing semantic matching framework (MCP-SM [29]), but faces concept extraction uncertainty, language and domain differences, and computational resource limitations. It is suggested to optimize the concept extraction algorithm, introduce multi-language and domain adaptation mechanisms, and optimize the model structure and computational process to improve the performance and applicability.

This study also compares the number of parameters, hardware equipment, training time, and context learning of recursive neural network matching methods, sentence vector matching methods based on large language models, and large language model-based matching methods utilizing different features, as shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Comparison of hardware configurations and training details for matching models.

In terms of the number of model parameters, there is an overall increasing trend from recursive neural network-based matching methods to interactive matching methods, to sentence vector matching methods based on large language models. Specifically, the MKPM model based on the recurrent neural network has the least number of parameters, which is 1.8 M, while the number of parameters of GPT4 is the largest, reaching an amazing 1.8 T. In terms of hardware requirements, as the performance of the matching model gradually increases, the requirements for the performance of the graphics card show a corresponding trend of enhancement. This suggests that to effectively train these high-performance matching models, we need to equip more advanced graphics card devices. Meanwhile, in terms of training time, the training time required for sentence vector matching methods based on large language models is also increasing. Notably, these matching models are designed based on contextual learning, which helps them to better understand and process complex semantic information.

This paper delves into the performance comparison of different matching models on different datasets, aiming to provide researchers with a comprehensive and detailed analysis perspective. Through comparative experiments and data analysis, different matching models do have significant differences in performance, as shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Performance comparison of matching models in different tasks.

The Pearson correlation (r), Spearman’s ρ, and MSE of MaLSTM on SICK were 0.8822, 0.8345, and 0.2286. The Acc of MaLSTM features + SVM was 84.2%. The GMN model based on the graph neural network had an accuracy of 84.2% and 84.6% on LCQMC and BQ, with F1 values of 84.1% and 86%. In the QQP dataset, we witness a gradual improvement in the accuracy of multiple matching methods. Initially, the recursive neural network-based matching method increases the accuracy to 89.03%, and then the interactive matching method further pushes this figure to 91.3%. Then, using the labeling information of the sentence pairs to be matched, the accuracy of the matching method climbed again to 91.6%. However, the fine-grained matching method, with its unique advantages, boosted the accuracy to a maximum of 91.8%, highlighting its sophistication in its current state. At the same time, the large language model shows performance growth on multiple datasets. Whether in MNLI, QQP, QNLI, COLA, or MRPC and RTE tasks, the big language model has grown in terms of GLUE scores, which fully proves the continuous improvement in the big language model’s performance. Of note is the performance of the GPT family of models on the dataset RTE. With the evolution from GPT to GPT3, the accuracy of the models also grows steadily, which fully demonstrates the continuous enhancement of the performance of the GPT series of models. In addition, the PANGU-sigma model shows a strong performance in several tasks. In CMNLI, OCNLI, AFQMC, and CSL tasks, it achieved accuracy rates of 51.14%, 45.97%, 68.49%, and 56.93%, respectively, which further validates its ability to handle complex tasks. In the fine-grained matching approach, our accuracy rate in the MRPC dataset is also further improved by introducing different large language models as skeletons. Specifically, the accuracies increased from 88.1% and 88.9% to 88.9% and 89.7%, and this enhancement again proves the effectiveness of the fine-grained matching approach.

This paper also outlines the APIs for the matching model, and different APIs have their advantages and disadvantages in terms of performance, ease of use, and scalability, and the selection of a suitable API (Application Programming Interface) depends on the specific application scenario and requirements, as shown in Table 11. These NLP APIs have their characteristics in several aspects, and by comparing them, we can draw the following similarities and differences. The similarity is that these APIs are launched by tech giants or specialized NLP technology providers with strong technical and R&D support capabilities. For example, Google Cloud Natural Language API, IBM Watson Natural Language Understanding API, Microsoft Azure Text Analytics API, and Amazon Comprehend API are the respective company’s flagship products in the NLP field, all of which reflect their deep technical accumulation and R&D capabilities. In addition, most of the APIs support multi-language processing, covering major languages such as English and Chinese to meet the needs of different users. Whether it is a sentiment analysis of English text or an entity recognition of Chinese text, these APIs can provide effective support. In terms of interface design, these APIs are usually designed with RESTful interfaces, enabling developers to integrate and invoke them easily. This standardized interface design reduces the learning cost of developers and improves development efficiency. In terms of application scenarios, these APIs are suitable for NLP tasks such as text analysis, sentiment analysis, entity recognition, etc., and can be applied to multiple industries and scenarios. Whether it is the analysis of product reviews on e-commerce platforms or the monitoring of public opinion in news media, these APIs can provide strong support.

Table 11.

Comparison of matching model APIs.

However, there are some differences in these APIs. First, API-providing companies may differ in their focus and expertise in NLP. For example, the Google Cloud Natural Language API excels in syntactic analysis and semantic understanding, while IBM Watson is known for its powerful natural language generation and dialog system. Second, while both support multilingual processing, the specific types of languages supported, and the level of coverage may vary. Some APIs may be optimized for specific languages or regions, to better suit the local culture and language habits. In terms of interface types, while most APIs utilize RESTful interfaces, some APIs may also provide other types of interfaces, such as SDKs or command-line tools. For example, Hugging Face Transformers provides a rich SDK and model library, enabling developers to train and deploy models more flexibly. Each API may also have a focus in terms of application scenarios. For example, some APIs may specialize in sentiment analysis, which can accurately identify emotional tendencies in a text, while others may focus more on entity recognition or text classification tasks, which can accurately extract key information in a text. In the marketplace, certain APIs are more advantageous due to their brand recognition, technological prowess, or marketing strategies. However, this advantage may change as technology evolves and the market changes. Therefore, developers need to consider several factors when choosing an NLP API, including technical requirements, budget constraints, data privacy, and security. In addition, each API may have some drawbacks or limitations. For example, some APIs may face performance bottlenecks and be unable to handle large-scale text data; or the accuracy of some APIs may be affected by specific domain or language characteristics. Therefore, developers need to fully understand the advantages and disadvantages of NLP APIs when choosing them, and combine them with their actual needs.

6. Comparison of Different Matching Models across Datasets and Evaluation Methods

This section focuses on outlining the performance of different matching models on different datasets as shown in Table 12. From the perspective of datasets, English datasets are widely used in matching models, while Chinese datasets are relatively few, mainly including OCNLI, LCQMC, BQ, Medical-SM, and Ant Financial. From the perspective of modeling, recursive neural network-based matching methods are mainly applied to natural language inference and implication (NLI) datasets such as SNLI and SciTail, and Q&A and matching datasets such as QQP, LCQM, and BQ. Interactive matching methods are mainly focused on NLI datasets such as SNLI and Q&A and matching datasets such as Trec-QA and WikiQA. Graph neural network matching methods are mainly applied to Q&A and matching datasets such as LCQMC and BQ, while fine-grained matching methods are widely applied to NLI datasets such as XNLI, Q&A, and matching datasets such as QQP, MQ2Q, etc., as well as other specific datasets such as MRPC and Medcial-SM. Semantic matching methods utilizing label information are mainly applied to NLI datasets such as SNLI and SciTech, SNLI and SciTail, and Q&A and matching datasets such as QQP. As for the matching methods based on large language models, their application scope is even wider, covering NLI datasets such as MNLI and QNLI, Q&A and matching datasets such as QQP, the sentiment analysis dataset SST-2, and other specific datasets such as MRPC and COLA. To summarize, different matching models are applied to all kinds of datasets, but the English dataset is more commonly used. The models perform well on specific datasets and provide strong support for the development of the natural language processing field.

Table 12.

Comparison of different matching model training datasets and evaluation methods.

From the perspective of evaluation metrics, when discussing the evaluation metrics for the sentence-matching task in Table 12, this study needs to first clarify the definition of each metric, as well as their applicability and effectiveness in different scenarios. First, accuracy (Acc) is a basic categorization evaluation metric, which is defined as the proportion of samples correctly predicted by the model to the total number of samples. In the sentence-matching task, when the distribution of positive and negative samples is more balanced, the accuracy rate can intuitively reflect the performance of the model. However, when faced with category imbalance, the accuracy rate may not accurately assess the effectiveness of the model.

For the regression prediction task of sentence similarity scores, the Pearson correlation (r) and Spearman’s ρ are two important evaluation metrics. The Pearson correlation (r) measures the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two continuous variables, while Spearman’s ρ measures the strength and direction of a monotonic relationship between two variables, which is less demanding on the distributional pattern of the data. These two metrics are useful in assessing the relationship between predicted and true scores. The Mean Square Error (MSE) is another commonly used metric for regression assessment, which calculates the mean of the squares of the differences between the predicted and true values. In the regression task of sentence similarity scoring, the MSE can directly reflect the accuracy of the model’s predicted scores. For the binary classification task of sentence matching, especially when the distribution of positive and negative samples is not balanced, the F1 score is a more accurate evaluation metric. It combines precision and recall and comprehensively evaluates the model’s performance by calculating the reconciled average of the two.

When the sentence-matching task involves ranking multiple queries or sentence pairs, the Mean Average Precision (MAP) and Mean Reverse Ranking (MRR) are two important evaluation metrics. MAP is used to evaluate the average precision of multiple queries, while MRR computes the average of the reverse of the first relevant result ranking across all queries. These two metrics are effective in evaluating the performance of the model in ranking results. The Macro-F1 is an evaluation metric for multi-category sentence-matching tassk. When calculating the F1 score, it calculates the F1 score for each category separately and then averages the scores, regardless of the sample size of the categories. This allows Macro-F1 to treat each category equally and is suitable for sentence-matching tasks where the performances of multiple categories need to be considered together. GLUE (General Language Understanding Evaluation) is a benchmark evaluation suite that includes a range of natural language understanding tasks. If a sentence-matching task is included in the GLUE suite, we can use the evaluation metrics provided (e.g., accuracy, F1 score, etc.) to evaluate the performance of the model. Finally, metrics such as MC/F1/PC may be acronyms or specific metrics under a particular task or dataset. In the absence of a specific context, they may stand for accuracy (MC may be an abbreviation for Multi-Class), F1 score, or some kind of precision. Depending on the specific task and dataset, these metrics may be used to evaluate different aspects of the performance of the sentence-matching model. By using a combination of these evaluation metrics, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the performance of sentence-matching models and optimize the model design accordingly.

7. Field-Specific Applications

This section provides insights into the wide range of applications of matching methods in different domains, especially in education, healthcare, economics, industry, agriculture, and natural language processing. Through the detailed enumeration in Table 12, we can clearly see the main contributions of matching models within each domain, as well as reveal the limitations they may encounter in practical applications and potential future research directions. In the exploration of text-matching techniques, we recognize their central role in several practical scenarios, especially in the key tasks of natural language processing, such as named entity recognition and named entity disambiguation. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the current status and trends of these techniques, we have expanded the scope of our literature review to cover research results in these areas. Named entity recognition (NER) [104] is a crucial task in natural language processing, whose goal is to accurately identify entities with specific meanings, such as names of people, places, organizations, etc., from the text. In recent years, with the continuous development of deep learning technology, the field of NER has made significant progress. Meanwhile, named entity disambiguation [105] (NED) is also an important research direction in the field of natural language processing. It aims to solve the problem that the same named entity may refer to different objects in different contexts, to improve the accuracy and efficiency of natural language processing. In summary, matching methods and text-matching techniques have a wide range of application prospects and an important research value in several fields. (See Table 13).

Table 13.

Field-specific application of text matching.

In education, matching technologies have significantly improved planning efficiency by automatically aligning learning objectives within and outside of subjects. In addition, the design of data science pipelines has enabled the analysis of learning objective similarities and the identification of subject clustering and dependencies. Meanwhile, text-matching software has demonstrated its versatility by being used not only as a tool for educating students but also for detecting inappropriate behavior. In the medical field, matching technology provides powerful support for doctors. It is used in the retrieval and generation of radiology reports, in the linking of medical text entities, and in Q&A systems to help doctors carry out their diagnosis and treatment more efficiently. In the economic domain, matching technology provides powerful support for the accurate provision of job information, the formulation of industry-specific recommendations, and the promotion of policy tourism and economic cooperation. Especially in the e-commerce field, matching technology has made a big difference, not only improving the accuracy of matching product titles in online shops and e-commerce platforms so that users can find the products they need more quickly but also significantly improving the efficiency and accuracy of product retrieval in the e-commerce industry. In addition, matching technology also solves the problem of duplicate product detection in online shops, which improves the operational efficiency and market competitiveness of the platform.

In the industrial field, text-matching technology is applied to robots, which enhances the model’s ability to understand the real scene and promotes the development of industrial automation. In the field of agriculture, the application of text-matching methods improves the retrieval efficiency of digital agricultural text information and provides an effective method for the scientific retrieval of agricultural information. In named entity recognition, named entity disambiguation, author name disambiguation, and historical documents in natural language processing, matching techniques play a crucial role. In named entity recognition, the matching technique, which dynamically adjusts visual information, can more effectively fuse the semantic information of text and images to improve the accuracy of recognition. In this process, the cross-modal alignment (CA) module plays a key role, narrowing the semantic gap between the two modalities of text and image, making the recognition results more accurate. In named entity disambiguation, the matching technique is also crucial. By exploiting the semantic similarity in the knowledge graph, the same entity in different contexts can be judged more accurately for disambiguation. In addition, the embedding model of joint learning also provides strong support for entity disambiguation, improving the performance of entity disambiguation by capturing the intrinsic relationship between entities. In summary, matching techniques play a crucial role in the field of named entity recognition and named entity disambiguation, which not only improves the accuracy of recognition but also provides strong support for other tasks in natural language processing.

In author name disambiguation, LightGBM creates a paper similarity matrix and hierarchical clustering method (HAC) for clustering, which enables paper clustering to be implemented more accurately and efficiently, thus avoiding the problem of over-merging papers. The automatic segmentation of words in damaged and deformed historical documents is achieved based on cross-document word matching in historical documents. An image analysis method based on online and sub-pattern detection is successfully applied to pattern matching and duplicate pattern detection in Islamic calligraphy (Kufic script) images. Through the above analyses, matching techniques have shown a wide range of application prospects and significant results in different fields, but at the same time, there are some limitations and challenges that require further research and exploration. To enable the text-matching technique to be applied in the specific application areas mentioned above, this study provides practical insights or guidelines for implementing the sentence-matching technique in real-world applications, including some hints on hardware requirements, software tools, and optimization strategies.

When implementing sentence-matching technology in the specific application areas mentioned above, it is first necessary to define the specific application requirements, including application scenarios, the desired accuracy, and response time. These requirements will directly guide the subsequent technology selection and model design. Subsequently, a high-quality, clearly labeled dataset is the basis for training an efficient sentence-matching model, so the data preparation stage is crucial. In terms of hardware, to meet the training and inference needs of deep learning models, it is recommended to choose servers equipped with high-performance GPUs or utilize cloud computing services. Meanwhile, a sufficient memory is essential to support data loading and computation during model training and inference. For storage needs, it is recommended to use high-speed SSD hard disks or distributed storage systems to accommodate huge datasets and model files.

In terms of software tool selection, deep learning frameworks such as TensorFlow and PyTorch are indispensable tools that provide a rich set of APIs and tools that greatly simplify the model development and deployment process. Text-processing libraries such as NLTK and spaCy, on the other hand, can help us efficiently perform text preprocessing and feature extraction. In addition, the combination of pre-trained models and specialized semantic matching tools, such as BERT [17] and Roberta [20], can further improve the accuracy of sentence matching.

To further improve the performance of the model, we can employ a series of optimization strategies. Data enhancement techniques [63] can increase the diversity of training data and improve the generalization ability of the model. Model compression techniques [75] can reduce the size and computations of the model, thus speeding up the inference. Multi-stage training strategies, especially pre-training and fine-tuning, can make full use of large-scale unlabeled data and small amounts of labeled data. Integrated learning [58] can further improve sentence-matching accuracy by combining predictions from multiple models. Finally, hardware optimization techniques such as GPU acceleration and distributed computing can be utilized to significantly improve the efficiency of model training and inference.

8. Open Problems and Challenges

8.1. Limitations of State-of-the-Art Macro Models in Sentence-Matching Tasks

Despite the dominance of the BERT [17] family and its improved versions in sentence-matching tasks, some state-of-the-art macro models, such as GPT4 [24] and GPT-5, are currently difficult to apply in sentence-matching tasks due to their not-yet-open-source nature. This limits to some extent the possibility that sentence-matching tasks can be advanced and developed using new technologies.

The application of state-of-the-art macro models to sentence-matching tasks is limited by multiple challenges. Among them, the issue of model openness driven by commercial interests is particularly critical. These models are usually owned by large technology companies or research organizations as a core competency and thus are not readily made public. Even partial disclosure may be accompanied by usage restrictions and high licensing fees, making it unaffordable for researchers and small developers. This openness issue not only limits the wide application of the model in sentence-matching tasks but also may hinder research progress in the field. The lack of support from advanced models makes it difficult for researchers to make breakthroughs in sentence-matching tasks and to fully utilize the potential capabilities of these models. Therefore, addressing the issue of model openness driven by commercial interests is crucial to advancing research and development in sentence-matching tasks.

8.2. Model-Training Efficiency of Sentence-Matching Methods

Most of the sentence-matching methods are based on large language models, which leads to high requirements on device memory during the training process, and the training time is up to several hours or even dozens of hours. This inefficient training process not only increases the consumption of computational resources but also limits the rapid deployment and iteration of the model in real applications. Therefore, we need to investigate how to optimize the model-training process, improve the training efficiency, and reduce the dependence on device memory, as well as reducing the training time.

It is difficult to solve the problem of the model-training efficiency of sentence-matching methods, mainly because of the following reasons: the high complexity of large language models leads to a large demand for memory, which poses a challenge to users with limited hardware; the training time is long, and the processing of a large amount of data requires multiple rounds of iterations, which consumes computational resources and affects the efficiency; how to reduce the dependence on memory and the training time, while guaranteeing performance, involves many technical challenges in terms of the model structure, the algorithm design, and data processing.

8.3. Assertion Comprehension and Non-Matching Information Interference in Sentence Matching

A key challenge in the sentence-matching task is the lack of in-depth understanding of the sentence claim, while being susceptible to interference from non-matching information. Sentence claims are the embodiment of the core meaning of a sentence, while noisy information or non-matching content may mislead the matching process. To address this problem, research is needed to design more effective model architectures or introduce new semantic understanding mechanisms to enhance the capture and recognition of sentence claims, while reducing the interference of non-matching information.

The main challenges of claim comprehension and non-matching information interference in sentence matching are the complexity and subtlety of sentence claim comprehension, which require the model to deeply analyze the semantics and context of the sentence; at the same time, non-matching information interference is difficult to overcome, as it requires the model to have a strong semantic differentiation ability to filter the interfering content. Therefore, solving these problems requires the model to realize significant breakthroughs in semantic understanding and information filtering.

8.4. Confusion or Omission in Handling Key Detail Facts

Key Detail Facts in Sentence-Matching Processing Detail information is crucial for accurate matching in sentence-matching tasks [121]. However, existing methods for sentence matching often suffer from the problem of confusion or omission when dealing with key detail facts. Losing certain detailed information may lead to inaccurate matching results. Therefore, there is a need to investigate how to optimize sentence-matching algorithms to capture and process key detail facts more accurately. This may involve the optimization of extraction, representation, and matching strategies for detailed information.

The main difficulties in processing key detail facts in sentence-matching tasks are the accurate extraction of detail information, effective representation, and the optimization of matching strategies. Due to the diversity and complexity of languages, it is extremely challenging to extract key details in sentences; meanwhile, existing methods may not be able to fully capture the full meaning of the detail information, leading to confusion or omission during the matching process; in addition, it is also a major challenge to design a matching strategy that can fully take into account the importance of the detail information, which may lead to inaccurate matching results.

8.5. Diversity and Balance Challenges of Sentence-Matching Datasets

Currently, most sentence-matching datasets focus on the English domain, while there are relatively few Chinese datasets. In addition, there is a relative lack of application-specific datasets to meet the application requirements in different scenarios. This imbalance and lack of datasets limit the generalization ability and application scope of sentence-matching models. Therefore, there is a need to work on constructing and expanding diverse and balanced sentence-matching datasets, especially increasing Chinese datasets and datasets of specific application domains, to promote the development and application of sentence-matching technology.

The diversity and balance challenges of sentence-matching datasets are significant, and are mainly reflected in the uneven distribution of languages, the lack of application-specific datasets, and the difficulty of guaranteeing the balance of datasets, etc. English datasets are relatively rich, while Chinese and other language datasets are scarce, which limits the generalization ability of the model in different languages. Meanwhile, the lack of domain-specific datasets results in limited model performance in specific scenarios. In addition, constructing a balanced dataset faces difficulties in data collection and labeling, and an unbalanced dataset may affect the training effect and matching accuracy of the model.

9. Future Research Directions

9.1. Future Research Direction I: The Problem of Sentence-Matching Model Publicity Driven by Commercial Interests and Solutions