Abstract

As the digital environment progresses, the complexities of cyber threats also advance, encompassing both hostile cyberattacks and sophisticated cyber espionage. In the face of these difficulties, cooperative endeavours between state and non-state actors have attracted considerable interest as crucial elements in improving global cyber resilience. This study examines cybersecurity governance’s evolving dynamics, specifically exploring non-state actors’ roles and their effects on global security. This highlights the increasing dangers presented by supply chain attacks, advanced persistent threats, ransomware, and vulnerabilities on the Internet of Things. Furthermore, it explores how non-state actors, such as terrorist organisations and armed groups, increasingly utilise cyberspace for strategic objectives. This issue can pose a challenge to conventional state-focused approaches to security management. Moreover, the research examines the crucial influence of informal governance processes on forming international cybersecurity regulations. The study emphasises the need for increased cooperation between governmental and non-governmental entities to create robust and flexible cybersecurity measures. This statement urges policymakers, security experts, and researchers to thoroughly examine the complex relationship between geopolitics, informal governance systems, and growing cyber threats to strengthen global digital resilience.

1. Introduction

The landscape of cybersecurity governance models involves interactions among stakeholders illustrating a range of cyber threats and vulnerabilities. The model relies on communication between government officials and those outside government organisations. Their efforts are seen as crucial for combating cyber dangers [1]. Multi-stakeholder cyber diplomacy enables collaboration among stakeholder sectors to enhance the effectiveness of initiatives. The absence of established systems underscores the need for innovative approaches to tackle emerging cyber threats, such as changes and the rise of non-governmental actors impacting diplomatic relations. Informal collaborations complement hierarchical structures, underlining the importance of flexible governance methods [2]. These insights reveal the ever-changing nature of cybersecurity governance, where both state and non-state actors play roles in addressing cyber threats and vulnerabilities. The interactions among these parties influence the development and implementation of cybersecurity policies and plans, underscoring the importance of collaborative approaches in tackling cyber challenges. For example, China’s cybersecurity governance framework has been influenced by its political, social, and economic contexts, resulting in strategies and laws to safeguard its digital domain [3]. By adopting a stakeholder approach to cybersecurity, China promotes the involvement of stakeholders, including government agencies, businesses, and civil society organisations. This cooperative strategy enhances our understanding of cybersecurity governance complexities and the challenges of navigating geopolitical landscapes. It is worth noting that the European Union and the United States have distinct legal, regulatory, and organisational laws governing cybersecurity, which are influenced by their historical, cultural, and geopolitical differences [4]. The EU prioritises coordination among member nations, whereas the US framework emphasises partnerships between the public and private sectors and industry-led initiatives. Examining the geopolitical dimensions of multi-stakeholder cyber diplomacy offers insights into the intricate relationship between geopolitical cybersecurity policies and international affairs. Cybersecurity governance touches on geopolitical factors beyond operational concerns and is tied to broader geopolitical trends. Hence, grasping the geopolitical dimensions of cybersecurity governance is essential for shaping policies and strategies that can adjust to geopolitical landscapes [5].

Furthermore, Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) are now acknowledged as a critical approach to enhancing infrastructure resilience against cyber threats [6]. By facilitating information sharing resource allocation and response coordination, PPPs leverage expertise and resources from both the public and private domains. PPPs encourage an approach to cybersecurity by promoting collaboration and a shared sense of accountability among stakeholders. This framework encompasses technical measures, policy formulation, governance practices, and risk management tactics to tackle cyber challenges. In the dynamic cyber threat landscape, PPPs offer an adaptable framework to address these intricacies. Ultimately, such partnerships can strengthen the resilience of critical infrastructure in the world. This study examines the dynamics in cybersecurity governance, with a focus on the role of actors in fostering cooperation and enhancing cyber resilience. The aim is to explore the responsibilities, contributions, challenges, and effects of state–non-state actor partnerships through a literature review method. This review delves into how countries and international organisations comprehensively address cyber threats, focusing on various geopolitical ramifications, such as differences in technology, governance, cooperation, etc. By studying themes and publications, this research seeks to shed light on the complex dynamics shaping the digital warfare landscape and provide insights into governance practices. Moreover, because digital warfare involves various issues of strategy, policy, corporations, etc., which impact cyberattacks and defences [7], this study focuses on digital warfare.

The next sections of this paper present and analyse the various aspects and studies about cyber war and warfare provided by the research community. Section 2 explains the methodology we used in this study. Section 3 is a holistic literature review of the topic. Section 4 explains three short case studies, and Section 5 discusses the findings and proposes future studies and some recommendations to organisations and governments (e.g., policymakers).

2. Methodology and Data Collection

This study employed a literature review methodology to investigate how state and non-state actors work together in cybersecurity governance. The review involved analysing various academic works and research findings connected to a specific area of interest. The review served as a framework for acquiring, assessing, and integrating information regarding collaborative efforts within cybersecurity governance. Creating a search strategy, formulating research questions, establishing criteria for study selection, reviewing and choosing relevant research and data, and evaluating the quality of studies were all crucial steps in conducting the literature review. Collecting a mix of evidence was crucial to understanding the roles, impacts, obstacles, and results of state and non-state actor partnerships in enhancing cybersecurity worldwide. Through this process, we aimed to highlight obstacles and detect patterns and zones for further investigation. Ultimately, this could inform the development of policies, research projects, and practical steps to enhance cooperation in cybersecurity on a global level.

In the thematic organisation phase, the collected data were systematically categorised based on themes to reveal patterns, trends, and reoccurring issues found in the literature [8]. A qualitative data analysis was performed to clarify the collaborative dynamics between state and non-state actors in cybersecurity governance. This synthesis entailed a comprehensive analysis and interpretation of the thematic patterns and trends revealed in the literature.

The data collection approach for this scientific literature review was undertaken diligently to ensure that all relevant material was found and included. The approach was outlined in the following steps.

Comprehensive Search: To ensure a comprehensive investigation, a thorough search of academic databases and scholarly repositories was conducted to find relevant peer-reviewed publications, conference papers, and research reports. The search used prominent databases such as PubMed, Scopus, IEEE Xplore, Google Scholar, and Web of Science.

Keyword Searches: Terms related to cybersecurity, cooperation, non-state actors, state actors, and governance were combined in the keyword searches. Based on each database’s search capabilities, these keywords were tailored to optimise the retrieval of relevant literature.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria: As Table 1 shows, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed to help select relevant material. The relevance of the research topics, the publication date, the language, and the study design were the criteria for selection, guaranteeing that only articles of superior quality and relevance were incorporated into the review, aligning with the predetermined criteria and the overarching focus on cybersecurity governance.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Using EndNote (version 20) for reference management was pivotal in maintaining a structured and efficient approach to handling citations and organising the vast array of articles collected during the search process. This methodical literature management served as a foundational element in assembling a robust and well-informed scholarly review, enabling the synthesis and interpretation of thematic patterns and trends within the literature to underpin the research’s comprehensive analysis of cybersecurity governance.

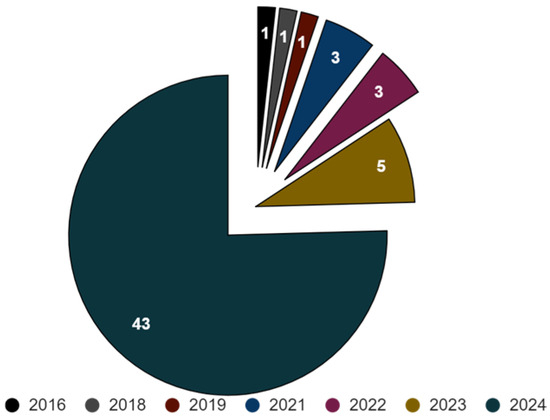

Categorisations: Using the keyword search, over 300 relevant publications were investigated. Considering relevance to the study topic, 64 publications were selected for this work. After carefully considering the 64 papers and attempts to categorise them, 57 papers were chosen due to their alignment with the essential areas deemed crucial for the study. This indicates that seven papers were excluded from the screening process. The criteria for selection included how well the paper fits with the main ideas, theoretical frameworks, empirical evidence, analysis, advocacy, and practical solutions needed for a full review of the cybersecurity landscape. Figure 1 illustrates the publication years of the papers. As it shows, most of the selected articles were published recently.

Figure 1.

Year of publication.

For each search, thorough searches were made on Google Scholar and other scholarly databases, such as PubMed, IEEE Xplore, and the ACM Digital Library. The search keywords were customised for each inquiry to assure relevancy and comprehensiveness. Papers were selected based on their pertinence to the research inquiries and adherence to the predetermined criteria. The search criteria, such as analysis of endeavours, case studies demonstrating achievements, obstacle identification, examples of used search keywords, etc., are captured in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of search focuses and alignment of criteria.

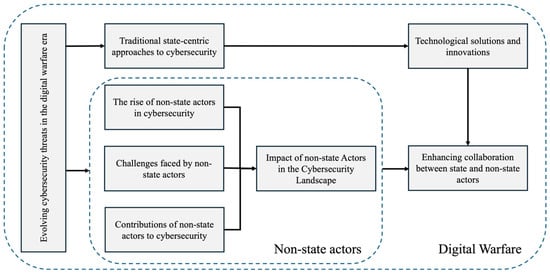

The considered focused areas help us understand solutions to tackle cyber threats in digital warfare. Figure 2 shows how the focused areas are linked together and support our analyses.

Figure 2.

Relationships between the focused areas.

By organising the themes in coherence with the main research questions, this research paper establishes a framework for comprehensive exploration, analysis, and integration of information pertinent to the evolving dynamics of cybersecurity governance. This thematic organisation enables a structured and focused approach to address the intricate relationship between geopolitics, informal governance systems, and growing cyber threats, ultimately enhancing global digital resilience.

The identified themes include:

Cooperative Endeavours in Cybersecurity Governance: This theme delves into the collaborative efforts between state actors and non-state actors, emphasising the role of international non-governmental organisations, business sector entities, and civil society organisations in enhancing global cyber resilience. It directly relates to the research question exploring the effectiveness of cooperative endeavours in improving global cyber resilience.

Emerging Cyber Threat Landscape: This theme encapsulates the evolving nature of cyber threats, including supply chain attacks, advanced persistent threats, ransomware, and vulnerabilities on the Internet of Things. It aligns with the research question seeking to understand the increasing dangers posed by contemporary cyber threats and their impact on global security governance.

Non-state Actors and Strategic Utilisation of Cyberspace: This theme explores how non-state actors, including terrorist organisations and armed groups, leverage cyberspace for strategic objectives. It sheds light on the growing significance of non-state actors in the cybersecurity domain. It directly connects to the research question examining the effects of non-state actors on global security and their implications for conventional state-focused security management approaches.

Informal Governance Processes and International Regulations: This theme emphasises the influential role of informal governance processes in shaping international cybersecurity regulations. It relates to the research question investigating the crucial influence of informal governance on forming international cybersecurity regulations and underscores the need for increased cooperation between governmental and non-governmental entities to develop robust cybersecurity measures.

3. Literature Review

Cybersecurity concerns are essential in shaping global politics and bringing risks to aspects such as national security stability and public well-being. Technology’s progress and reliance on connected ICT systems have resulted in a rise in cyberattacks carried out by various state and non-state actors. Understanding the impact of these dangers is essential in an era where the line between the physical and digital realms is becoming increasingly blurred. This research explores how countries and entities address cyber threats, focusing on their efforts. By examining common themes and the existing literature, this study aims to help untangle the complexities of the cyber landscape while providing insights into effective governance practices.

3.1. Evolving Cybersecurity Threats in the Digital Warfare Era

In the digital warfare era, the increasing dependence on information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure has led to remarkable interconnectedness, facilitating everyday life. However, this dependence also introduces significant vulnerabilities that malicious actors exploit, posing grave security risks [9]. Cybersecurity threats have become more sophisticated and targeted. The impact of these threats on the geopolitical landscape is significant, as state and non-state actors increasingly use cyber capabilities to pursue their strategic objectives and undermine the security of rival nations [10].

Among the variety of risks facing ICT infrastructure, advanced persistent threats (APTs), ransomware, and supply chain attacks stand out as particularly menacing adversaries. Understanding the nature of these dangers is essential for creating efficient defence tactics to protect sensitive data and vital systems [7]. For example, the APT group known as “Fancy Bear” has been linked to numerous high-profile attacks targeting government agencies and political organisations [11]. Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) are complex cyberattacks carried out by skilled attackers with significant resources and skills [12]. Advance Persistence Threats (APTs) are known for being secretive and long-lasting, as malicious individuals use sophisticated methods to breach specific networks, steal confidential information, and sustain unnoticed entry for extended periods [13]. The multilayered campaigns usually start with thorough reconnaissance efforts to identify vulnerabilities and potential entry sites. Attackers then carry out the initial breach using techniques such as spear phishing or other social engineering approaches. After infiltrating the network, attackers move horizontally and increase their access rights, enhancing their authority and enabling activities like espionage, the theft of intellectual property, or disruption [14]. APTs differ from traditional cyberattacks by employing a sophisticated approach that involves patience, precision, and strategic navigation of networks to achieve objectives while avoiding detection. APTs can develop a strong presence in targeted locations due to their secretive and persistent characteristics, which allow them to conduct long-term surveillance, steal data, and carry out hidden operations [15]. APTs can bypass conventional security measures by using sophisticated methods and taking advantage of weaknesses, which poses challenges for companies in terms of identification and mitigation [13]. APTs frequently exhibit a strong ability to adapt, constantly changing their methods and approaches to bypass protective measures and take advantage of new weaknesses [12,13]. To address this dynamic nature, organisations must deploy proactive cybersecurity measures such as continuous monitoring, threat intelligence exchange, and effective defence-in-depth tactics [16]. Actors can reduce the risk of APTs by strengthening their resilience and improving their detection skills, therefore protecting their digital assets and infrastructure against complex cyber assaults.

Ransomware has become a widespread and disruptive cyber threat that targets enterprises in several sectors via encryption-based extortion methods [13]. The WannaCry ransomware attack in 2017, which affected over 200,000 computers across 150 countries, is a prime example of the devastating impact of ransomware [17]. Cybercriminals use phishing emails or exploit kits to acquire unauthorised access to a victim’s network in a ransomware attack. Upon gaining access, they utilise advanced encryption algorithms to make important data or systems unreachable, essentially keeping them captive. Afterwards, the attackers request money, typically in cryptocurrency, in return for decryption keys or the commitment to unlocking the encrypted data. Ransomware versions have evolved to use complex evasion strategies such as polymorphic malware and file-less attacks to bypass traditional security measures, making identification and prevention more challenging [18]. Polymorphic malware changes its code with each infection, making it difficult for antivirus tools to identify, while file-less attacks use genuine system processes to run harmful payloads without conventional traces [19]. Organisations should use multilayered protection techniques and strong backup and recovery processes to reduce the danger of ransomware attacks, as these tactics make ransomware threats more sophisticated and powerful.

Supply chain attacks have increased recently, with malicious individuals targeting suppliers, vendors, and partners to undermine the quality of products, services, or infrastructure [12]. The SolarWinds breach in 2020, which affected numerous government agencies and private companies, is a prime example of the devastating impact of supply chain attacks [20]. These covert attacks take advantage of weaknesses in the supply chain to breach secure networks, spread harmful software, or tamper with trusted software updates, creating substantial risks for enterprises and their stakeholders [18]. Organisations must implement a proactive strategy for managing supply chain risks, which involves thoroughly evaluating vendors, enhancing supply chain transparency, and developing plans for responding to incidents. Organisations may reduce the effect of supply chain attacks and strengthen the resilience of their operations by improving their defences and working closely with partners and industry peers.

APT, ransomware, and supply chain attacks are significant cybersecurity risks that need proactive steps to reduce their impact efficiently. Actors can improve their ability to withstand and protect against emerging cyber threats by comprehending threat actors’ strategies, methods, and protocols and establishing strong security measures [21]. Collaboration, information sharing, and continual monitoring are crucial to combating the ever-changing cyber threats and protecting ICT infrastructure in a more linked world.

3.2. Traditional State-Centric Approaches to Cybersecurity

Historically, cybersecurity strategies and policies have been greatly shaped by approaches emphasising the role of governments in safeguarding national interests and critical infrastructure from cyberattacks. These methods prioritise leveraging power and assets to establish an integrated framework for addressing cyber threats and minimising risks to security. Despite their effectiveness, such approaches’ constraints are becoming more apparent given the constantly morphing landscape of cyber threats. The intricacies and interdependencies within cyberspace extend beyond borders, posing challenges for state-centred measures to adapt to the evolving terrain [22].

Additionally, state-centric approaches may struggle to address cyber threats originating beyond their borders, hindering their ability to protect national interests effectively [23]. With these limitations, there is a growing need for broader, more inclusive approaches to cybersecurity governance. Exploring multi-stakeholder models that involve government agencies, businesses, and civil society organisations can foster collaboration and leverage diverse expertise, ultimately leading to more robust and adaptable cybersecurity strategies [3].

Likewise, strengthening public–private sector collaboration can facilitate information sharing and coordinated action to combat cross-border threats [24]. For instance, the Australian government’s partnership with academic researchers exemplifies the shift towards collaborative governance models, acknowledging the complexity of contemporary cyber challenges [25]. By incorporating a wider range of perspectives and experiences, such collaborative approaches can enhance the effectiveness and adaptability of cybersecurity strategies in addressing evolving threats.

Addressing the complexities of contemporary cyber threats necessitates moving beyond state-centric approaches and embracing collaborative and inclusive governance models that incorporate a more comprehensive range of stakeholders and expertise.

3.3. The Rise of Non-State Actors in Cybersecurity

The role of non-state actors in cybersecurity is changing significantly. These actors, including international NGOs, private sector organisations, and civil society groups, are playing a role alongside state actors in addressing the challenges of the digital age. Their role is critical in navigating the evolving cybersecurity threats landscape.

Non-state actors are actively involved in cybersecurity governance models. They partake in initiatives to build capacity by offering training and resources to government agencies and stakeholders on practices and emerging threats. Moreover, they engage in advocacy work to influence policymaking and raise awareness about important ICT security issues [1]. This collaborative approach encourages sharing knowledge and expertise, resulting in more robust and adaptable cybersecurity strategies. They are crucial in safeguarding critical national infrastructure from ever-present cyber threats. Their knowledge, tools, and creative methods complement the government’s actions in ensuring that systems are strong. Their collaboration with government bodies and partners helps create cybersecurity strategies to deal with weaknesses in infrastructure sectors. This joint work plays a role in upholding the operation and safety of services that are important to society.

In today’s conflicts, groups use strategies and tactics to achieve their objectives. Petrosyan [26] analysed how non-state actors are involved in warfare, focusing on conflicts such as those in Syria and Nagorno Karabakh. Their research highlights how non-state actors strategically use cyberspace to disrupt enemy operations, spread propaganda, and coordinate strikes quickly and accurately. Non-state actors undermine traditional state-centric conflict resolution and security governance by utilising cyberspace as a battleground, which presents distinctive obstacles to international stability and peacekeeping endeavours. Furthermore, their ability to take advantage of technological weaknesses and participate in information warfare hinders efforts to effectively prevent and counter their actions [27].

Overall, the rise of non-state actors in ICT cybersecurity represents a significant shift in the global security landscape. Their diverse contributions shape policy, infrastructure protection strategies, and responses to cyber warfare. As the digital age continues to evolve, effective collaboration between state and non-state actors will be crucial for building a secure and resilient ICT ecosystem.

3.4. Contributions of Non-State Actors to Cybersecurity

Non-state actors are crucial in strengthening cybersecurity resilience by shaping global norms and standards, fostering knowledge transfer, and collaborating on joint initiatives. Non-state actors significantly influence cybersecurity norms in the digital age [28]. They actively participate in multi-stakeholder dialogues and advocacy campaigns, contributing diverse perspectives to developing best practices and governance frameworks. This collaborative approach leads to more comprehensive and effective cybersecurity policies. Furthermore, non-state actors leverage their expertise and connections to raise awareness and encourage compliance with these standards. This fosters a culture of accountability and collaboration among all stakeholders, including governments, businesses, and individuals [4].

At the national and regional levels, capacity-building initiatives play a major role in enhancing cybersecurity expertise. Non-state actors, such as international NGOs and civil society organisations, actively contribute to these efforts by organising training programmes and promoting knowledge exchange [29]. This equips stakeholders with the necessary skills and resources to effectively address the evolving threats in cyberspace.

Non-state actors play a crucial role in forging partnerships, exchanging insights, and shaping norms. Their skills and connections enable them to work with governments and international organisations on initiatives to strengthen cybersecurity and promote cooperation against cyber threats [5]. This collaborative approach involves diverse entities such as industry associations, academic institutions, and think tanks partnering with stakeholders to enhance cybersecurity practices and foster collaboration. These efforts enhance defence capabilities on a global scale by leveraging resources and networks to share expertise and intelligence. Engagement in these initiatives promotes trust and resilience across sectors and boundaries. Enhancing cooperation among parties and joint actions is crucial in addressing cyber risks and creating a safer online environment for all.

Case studies provide valuable insights into the specific measures and collaborations carried out by non-governmental groups to tackle distinct cyber dangers and difficulties effectively. Maschmeyer [30] explores how non-state players undermine cyber operations and wield structural influence in global politics. Non-state actors impact cybersecurity policy development and question the prevailing narratives on a global scale through strategic partnerships and lobbying efforts. Studying these case studies can help policymakers and cybersecurity experts understand the techniques used by non-state actors to reduce cyber dangers and enhance cybersecurity.

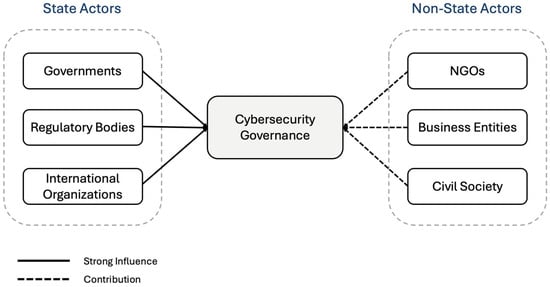

These findings can guide the creation of policies and programmes that utilise the assets and talents of non-state actors to improve cybersecurity resilience and promote international cooperation. The in-depth research on state-sponsored cyberattacks that was conducted by Azubuike [31], clarifies the complex relationships between governing bodies and non-governmental organisations when it comes to mitigating cyber threats. Non-state actors are crucial in helping government entities and private sector organisations reduce cyber risks and improve cyber resilience by offering expertise and technological assistance. Figure 3 illustrates the roles of example state and non-state actors in cybersecurity governance.

Figure 3.

Roles of state and non-state actors in cybersecurity governance.

3.5. Challenges Faced by Non-State Actors

Non-state players have impacts on cybersecurity and face obstacles that can affect their ability to deal with cyber threats efficiently. Limited resources are a major challenge for these stakeholders when they are involved in cybersecurity initiatives. Maulana and Fajar [32] explore cyber diplomacy and its barriers in the society era. They shed light on state and non-state actors’ challenges, including various threats (e.g., political process and privacy). There are also other challenges mentioned in other studies, such as limited expertise and constrained technical capabilities [33]. These barriers prevent these entities from establishing strong cybersecurity measures and responding promptly to cyber threats. For example, inadequate resources can hinder their capacity for research, designing solutions, and addressing cyber threats, which restricts their role in strengthening cybersecurity resilience. Adapting to changes in the cyber threat landscape and building partnerships with governments, businesses, and other entities and communities can be difficult for non-state actors due to limited resources. Thus, resource allocation is essential for enhancing non-state players’ role and efficiency in cybersecurity and cyberspace resilience.

Legal barriers pose challenges for organisations involved in addressing cybersecurity threats. Abdullahi and Musa [34] emphasised the hurdles faced by non-state entities in navigating the legal landscape. These actors deal with uncertainties and jurisdictional issues when combating cybercrimes, which hinders their ability to uphold cybersecurity norms effectively [35]. The absence of frameworks and the complex nature of cross-border cyber incidents worsen challenges. Non-state actors struggle to hold cybercriminals accountable, underscoring the importance of legal expertise and global collaboration.

Lewis and Baez [36] study theories related to control and how they influence warfare, underlining the difficulties in coordinating responses to cyberattacks that involve stakeholders such as government, agencies, businesses, and organisations. The lack of coordination among these groups arises from conflicts of interest, disparities in knowledge levels, and conflicting objectives. Consequently, this results in disjointed and chaotic responses to cyber threats, diminishing the overall effectiveness of cybersecurity measures. Overcoming coordination challenges requires improving communication mechanisms, establishing avenues for collaboration, and promoting trust among stakeholders within the cybersecurity community. Addressing these challenges can enhance the ability of non-state actors to respond to cyber threats effectively, strengthening cybersecurity governance and resilience on a global scale.

The continuously evolving landscape of cyber threats adds another layer of challenge for addressing cybersecurity issues. Diro, Kaisar [37] explained anomaly detection within information networks, underscoring the agility of threats and the importance of adaptable cybersecurity methods in response to evolving threats. Non-state entities must accommodate new cyber threats and vulnerabilities, necessitating ongoing investment in research, development, and capacity-building efforts to stay ahead of cyber attackers. Taking a proactive and adaptable stand for those outside government circles can proactively predict and respond to emerging threats in cyberspace.

3.6. Impact of Non-State Actors in the Cybersecurity Landscape

Non-state actors significantly affect the cybersecurity norms and policies that are vital in mitigating cyber threats. Through avenues such as advocacy, research, and engagement with diverse stakeholders, they substantially impact cybersecurity standards and regulations. For instance, Painter [38] examines how non-state actors, including industry companies, civil society organisations, and academic institutions, collaborate to shape cybersecurity legislation, particularly through multi-stakeholder participation in cyber stability issues within the United States. These actors are instrumental in influencing cybersecurity norms and standards by facilitating discussions among stakeholders from various sectors, thus enabling the consideration of a broad spectrum of viewpoints and interests. Consequently, they contribute to developing inclusive and representative cybersecurity governance frameworks that address cyber threats’ complex and evolving nature through collaborative efforts.

Additionally, non-state actors are crucial in enhancing the legitimacy and rationale of cybersecurity governance by actively participating in deliberative processes and decision-making procedures. Zhao [39] explores how legitimacy is conferred through discussions involving non-state actors, focusing on the involvement of women’s groups in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Advocacy groups and grassroots organisations, among other non-state actors, contribute diverse perspectives and expertise to policy dialogues, enriching the deliberative process and fostering inclusive and representative cybersecurity governance frameworks. Their involvement ensures that a wide array of viewpoints is considered, resulting in more robust and comprehensive cybersecurity policies that address the requirements and concerns of various stakeholders.

Nonetheless, regulatory cybersecurity governance encounters challenges in establishing credibility, as non-state players struggle to assert their influence on developing regulatory frameworks and standards. Dunn Cavelty and Smeets [40] examine the evolution of regulatory cybersecurity governance, focusing on establishing the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) and its challenges in acquiring accurate information. Industry stakeholders and cybersecurity specialists seek to garner credibility and influence in shaping cybersecurity policies. However, they face resistance from entrenched state-centric governance paradigms that often prioritise traditional governmental structures and decision-making processes. Despite these challenges, non-state actors persist in enhancing cyber governance by advocating for inclusive and participatory approaches that acknowledge their diverse viewpoints and expertise.

Non-state actors are pivotal in bolstering cybersecurity resilience by establishing new governance structures and implementing capacity-building programmes, notwithstanding their challenges. They contribute to developing flexible and robust cybersecurity strategies by fostering collaboration and facilitating information sharing among stakeholders [41]. These initiatives effectively mitigate emerging cyber threats and vulnerabilities, ultimately enhancing the overall resilience of cyber defences. Thus, non-state actors influence the cybersecurity landscape considerably, guiding it towards greater agility and responsiveness to evolving threats.

3.7. Enhancing Collaboration Between State and Non-State Actors

Collaboration between governmental and non-governmental entities is pivotal for effectively addressing the intricate and evolving challenges of cybersecurity. It facilitates sharing information, resources, and knowledge, thereby significantly enhancing cybersecurity resilience [42]. Governments, corporate sector organisations, and civil society groups can develop innovative solutions to combat changing cyber threats by pooling their resources and expertise. Collaborative projects foster trust and cooperation among stakeholders, which is essential for developing robust cybersecurity frameworks. Moreover, they empower the cybersecurity community to anticipate emerging threats and protect digital infrastructure by leveraging multiple stakeholders’ combined insights and capabilities. State and non-state entities possess distinct capacities that, when combined, can effectively address cybersecurity issues.

Insurance companies have an important role in motivating businesses to invest in cybersecurity [43]. They do this by working with governmental regulators, providing incentives and expertise for risk assessments, and mitigating risks. Through these partnerships, a strategy is developed to take advantage of strengths in order to address cybersecurity challenges efficiently. Involvement also prompts organisations to proactively manage cyber risks by implementing robust cybersecurity measures to protect themselves against cyberattacks. The collaboration between public and private sector partners, including insurers, is crucial in building a landscape that can effectively and proactively respond to cyber threats [44].

Policymakers should prioritise the establishment of multi-stakeholder forums and partnerships to improve coordination between governmental and non-governmental entities in cybersecurity. These forums provide a formal platform for stakeholders from different sectors to exchange ideas, share insights, and combine resources [45]. They facilitate open communication and collaboration among various parties to address shared cybersecurity issues and develop joint solutions. Moreover, these platforms help exchange best practices and lessons learned, enhancing cybersecurity resilience across various sectors and businesses. Policymakers are instrumental in promoting cooperation between governmental and non-governmental entities through legislative frameworks and funding mechanisms. Additionally, policymakers may promote the creation of new cybersecurity solutions by investing in joint research projects, capacity-building programmes, and knowledge-sharing activities.

Enhancing capacity is crucial for fostering cybersecurity collaboration between governmental and non-governmental organisations [46]. Iacono and Mastroianni [47] proposed a modelling framework that can be used by governments to create and evaluate policies to make the cyber environment safer for users. Their work can help policymakers make policies and regulations effective in reducing privacy and security risks. Training programmes, workshops, and knowledge exchange initiatives can help foster teamwork and encourage a culture of cooperation in addressing cyber threats. Investing in capacity-building projects enables stakeholders to improve their comprehension of cybersecurity threats and acquire the necessary skills and experience to address cyber issues proficiently. These projects offer opportunities for stakeholders to exchange knowledge, share best practices, and collaborate on methods to tackle shared cybersecurity issues. Capacity building enhances trust and confidence among stakeholders, promoting stronger interactions and partnerships in the cybersecurity ecosystem. It is crucial for enhancing collaboration and bolstering the collective resilience of governmental and non-governmental organisations against cyberattacks.

3.8. Technological Solutions and Innovations

The increase in cyber threats today is due to our dependence on technology. This section focuses on understanding the concept of cyber resilience, leveraging advanced tools such as artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain, and Internet of Things (IoT) security.

Integrating AI and blockchain technologies into security frameworks has sparked interest among researchers. For example, Girdhar, Singh [48], examined the use of AI and blockchain in enhancing security for cyber-physical systems. Similarly, Tyagi [49] explored how blockchain and AI technologies contribute to securing the Internet of Things and industrial Internet of Things applications. These studies shed light on innovative approaches to combating cyber threats and demonstrate the potential of these technologies in fortifying cyber resilience.

The rise in the use of IoT devices represents a turning point in technology, presenting a mix of challenges and opportunities. The increase in connected devices, especially in areas like homes, wearable technology, industrial equipment, and infrastructure, elevates the risk of cyberattacks, as noted by Lone, Mustajab [50]. In their study, Lone et al. conducted a deeper analysis of the security challenges within the realm of IoT. Their findings emphasise the importance of implementing strong security measures to protect IoT environments from cyber threats, underscoring the urgency of implementing proactive defence mechanisms. Moreover, their research highlights the vulnerabilities found in IoT setups, emphasising the significance of robust security measures in developing and deploying IoT solutions. As the network of connected devices expands, bad actors will find more opportunities to breach systems. This study underscores the importance of emphasising cybersecurity in IoT implementations by proactively detecting and addressing vulnerabilities to predict and prevent security breaches. It stresses the need for stakeholders across industries to take precautionary steps.

In the domain of global cybersecurity governance, the increase in advanced technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), blockchain, and the Internet of Things (IoT) introduces distinctive risks and regulatory challenges. The integration of AI in cyber threats presents a multifaceted challenge due to the emergence of sophisticated AI-driven cyberattacks and data manipulation by creating deepfake content. Regulatory challenges are particularly evident in the standardisation of AI in cybersecurity and necessitate a comprehensive approach to address ethical considerations and harmonise regulations across international boundaries [51,52].

Meanwhile, blockchain technology introduces decentralised threat vectors and fosters anonymity, promoting illegal activities and posing potential cybersecurity risks. Regulatory challenges for blockchain pertain to the need for global harmonisation of regulations and the establishment of interoperable standards to address diverse implementations and interpretations. Furthermore, the widespread adoption of IoT devices significantly expands the attack surface. It raises data privacy and integrity concerns, calling for standardised regulations and governance practices to mitigate fragmented security frameworks and complex supply chain oversight [50,53].

In navigating these challenges within global cybersecurity governance, collaborative efforts are imperative to formulate interdisciplinary regulatory frameworks that effectively address the technical intricacies of AI, blockchain, and IoT, thus safeguarding against emerging cyber threats. It is essential for state and non-state actors to work collectively in establishing adaptive governance mechanisms that accommodate the evolving nature of cybersecurity risks in the digital age, promoting harmonisation of regulations and cybersecurity best practices to foster resilience and address the complexities posed by these technologies at a global scale.

To enhance cyber resilience, particularly during an ever-evolving cyber threat landscape, Vegesna [54] dives into an analysis of cyber resilience focusing on the effectiveness of AI-based threat detection and mitigation systems. By strengthening their cyber defence capabilities, organisations can rapidly detect and neutralise emerging threats using AI algorithms. AI’s capability to adjust and learn from patterns in data and threat landscapes enhances cyber defences and thwarts potential breaches. Saeed, Altamimi [55] suggest a structured approach for managing cyber threats, underscoring the importance of proactive defence tactics in mitigating cyber risks. Their strategy introduces a systematic framework for fortifying cyber defences and streamlining responses to cyber incidents effectively. Leveraging AI-powered solutions for threat detection and mitigation is crucial in addressing cyber risks, protecting assets, and ensuring business continuity in the face of evolving threats.

When it comes to the cyber challenges faced by entities, including state-owned businesses, a thorough examination of the challenges related to their digital transformation is essential. Saeed, Altamimi [55] described the obstacles organisations face during this process. State-owned businesses are prone to a range of security gaps and threats arising from factors like outdated systems and sophisticated cyberattacks launched by malicious actors aiming to exploit weaknesses in digital infrastructure. The study emphasises the necessity of developing robust security measures tailored to state-owned entities’ specific needs and challenges. A comprehensive strategy involves addressing advancements in technology preparedness at the organisational level and regulatory requirements.

Advanced cybersecurity tools such as AI-driven threat detection systems and blockchain-strengthened security measures are vital in fortifying defences and enhancing resilience against emerging threats. Safitra, Lubis [56] underscore the importance of training programs, awareness campaigns, and incident response protocols to boost defences and instil a culture of cyber awareness in government-controlled entities. Establishing robust regulations is critical for defining standards and ensuring compliance levels in state-owned entities. Organisations can reduce cyber risks, enhance resilience, and confidently navigate the digital landscape by enforcing directives covering these aspects.

Table 3 lists publications categorised according to their relevance and impact within the subject areas. Each publication is grouped based on its significance in discussing key topics, providing evidence, and sharing concepts.

Table 3.

Publication categories and description.

3.9. Emerging Threats in Cybersecurity

Kumar [12] examined the obstacles within the realm of cybersecurity. Kumar’s objective is to emphasise the importance of addressing security threats such as APTs, ransomware attacks, vulnerabilities linked to the Internet of Things (IoT), and social engineering tactics. By thoroughly examining and synthesising the available data, the research aims to clarify the nuances of these risks, highlighting their significance for individuals, organisations, and society at large. Kumar stresses the significance of taking action and fostering partnerships to strengthen cybersecurity measures by exploring the complexities. Their work can be a reference point for professional policymakers and researchers within each threat category, providing valuable insights to navigate the challenging landscape of cybersecurity threats today effectively. Table 4 captures cybersecurity threats and their descriptions to help better understand the threats to be mitigated.

Table 4.

Threats analysis.

Kumar [12] provides insight into the changing nature of digital threats by emphasising the urgent requirement for proactive cybersecurity measures by recognising and analysing emerging threats such as APTs, ransomware, IoT vulnerabilities, and social engineering tactics. Organisations and cybersecurity experts should take note of these findings, which emphasise the significance of implementing a comprehensive defence strategy. This strategy should include strong security regulations, frequent cybersecurity awareness training, and continuous threat intelligence. It is recommended that policymakers prioritise cybersecurity activities, promoting cooperation among governments, organisations, and individuals to create efficient strategies and structures for sharing information.

Nevertheless, Kumar’s research has limitations, including the possibility of bias in threat selection or dependence on obsolete data. Future research should further examine the other factors (e.g., socio-political and psychological factors) that drive cyber threats, investigate new methods of attack in developing technologies, and evaluate the effectiveness of present measures for preventing and mitigating cyberattacks in real-world situations. By engaging in ongoing research and fostering collaboration, cybersecurity communities can effectively enhance their ability to respond to the constantly evolving nature of digital warfare.

Moreover, their study has important implications for guiding the execution of cybersecurity measures in our research on the “Geopolitical Ramifications of Cybersecurity Threats.” To comprehensively examine the role of non-state entities in promoting international cooperation and enhancing global cyber resilience, it is crucial to have a thorough grasp of the range of cyber threats. Kumar’s categorisation of many types of cyber risks and threats offers a fundamental comprehension of the difficulties for states.

To address these dangers, it is necessary to implement targeted strategies and utilise appropriate technologies. For example, when defending against APTs, it is crucial to implement strategies like network segmentation, advanced threat detection systems, and regular security audits. Ransomware attacks require the implementation of measures such as frequent data backups, thorough employee training on phishing awareness, and robust endpoint security solutions (e.g., endpoint detection and response solutions). To address IoT vulnerabilities, it is important to implement secure device authentication, encrypt data while it is being transmitted, and perform regular firmware upgrades and network segmentation (if needed). To mitigate social engineering threats, it is essential to provide employees with cybersecurity awareness training, implement multi-factor authentication, and conduct regular phishing simulation exercises. Of course, AI-powered solutions can help us to detect, prevent, and respond to all of the mentioned cyber threats.

By aligning these strategies (focusing on non-state actors), we can anticipate how these entities might contribute to implementing and enhancing these measures globally, thereby strengthening global cyber resilience and cooperation in the era of digital warfare. Using a table structure to highlight these mitigation techniques improves clarity. It offers a useful reference for policymakers and stakeholders who want to effectively utilise non-state entities to tackle future cyber dangers. Table 5 presents examples of the mitigation strategies that can be employed to handle all the threats identified.

Table 5.

Mitigation strategies.

3.10. Analysis of Non-State Actors in Modern Warfare

Petrosyan [26] analysed the involvement of non-state players in contemporary warfare, offering a complete exploration of the changing dynamics of conflicts. The study highlights the growing significance of non-state actors, such as armed groups and terrorist organisations, in influencing modern battles. Using case studies, Petrosyan demonstrated the emergence of key actors in Syria and Nagorno-Karabakh who exercise influence using both conventional and unconventional strategies. It emphasises the hybrid nature of their operations, combining superior technical weaponry and artificial-intelligence-driven devices to improve their operational efficacy on the battlefield.

Petrosyan’s study enhances our comprehension of the intricate dynamics of contemporary warfare, thereby shedding light on the diverse character of conflicts in today’s geopolitical setting. The knowledge obtained from their work emphasises the significance of acknowledging the changing role of non-state actors and their influence on the progress and result of hostilities. This comprehension is essential for policymakers, military strategists, and security professionals responsible for creating efficient tactics to tackle the difficulties non-state actors present in modern conflict situations.

Petrosyan’s research greatly enhances our comprehension of contemporary warfare by clarifying non-state actors’ crucial involvement and influence on wars. The report offers valuable insights for politicians, military strategists, and security professionals by examining these actors’ motivations, capabilities, and strategies. Gaining insight into non-state players’ operational and tactical behaviours is crucial, as it exposes their capacity to disrupt, create damage, and inflict casualties in conflicts, even if they do not directly impact the strategic elements. This knowledge provides stakeholders with the essential resources to adjust to the changing characteristics of warfare and formulate efficient tactics to counter the risks presented by non-state actors. Policymakers can use these findings to guide diplomatic efforts, military strategists to customise their approaches to countering insurgencies, and security (including cybersecurity) professionals to strengthen their defence systems.

To advance Petrosyan’s research and collaborative efforts, it is crucial to explore further the motivations, tactics, and consequences of non-state actors’ participation in conflict. By being thoroughly aware of these elements, politicians, military strategists, and security experts can design strong tactics to effectively fight the risks posed by non-state actors in modern conflict scenarios. Petrosyan’s work is an important basis for current conversations and efforts to improve our understanding of the changing nature of conflict and to ensure proactive responses to emerging security concerns worldwide.

3.11. Analysis of International Cybersecurity Governance

Sukumar, Broeders [2] offer a comprehensive analysis of the complex dynamics of the global cybersecurity governance system, focusing mainly on the widespread and significant role of informal methods. The authors analyse the connections between geopolitics, non-state actors, and diplomatic processes to understand how these elements shape the informal institutions that govern cybersecurity. This detailed analysis highlights the crucial importance of informal governance mechanisms, primarily when no official international cybersecurity treaty exists. The authors explain how informal processes facilitate communication and decision making between nation states and non-state players at the United Nations and other international forums.

Their study illustrates how different actors, driven by diverse interests, contribute to the complexity of the regulatory landscape. The military, for instance, emphasises the preservation of cyber capabilities, which may conflict with efforts to maintain stability. Corporations, on the other hand, often prioritise economic gain over security concerns. Intelligence agencies seek to gather information through cyber operations, potentially impacting trust and collaboration. Additionally, national cybersecurity strategies are influenced by both geopolitical and economic considerations.

Raymond and Sherman [63] explained the term “authoritarian multilateralism”, which refers to the strategy employed by certain countries, such as China and Russia, to manipulate the processes of multilateral organisations to promote their interests, going against the principles of liberal multilateralism. This deviation from transparency, inclusivity, and accountability highlights a notable change in the worldwide cybersecurity environment, where authoritarian entities exert considerable control over norms and rules. This phenomenon highlights the importance of a detailed grasp on how geopolitics and global cybersecurity governance interact.

Sukumar, Broeders [2]’s research highlights the crucial significance of informal governance in cybersecurity, shifting the usual focus from formal institutions. They support a more thorough investigation of the interactions between states, non-state actors, and informal diplomatic channels, acknowledging the complex nature of the digital environment.

To enhance global cybersecurity, it is necessary for future studies to thoroughly investigate the changing dynamics of informal governance and how it influences policy frameworks. Gaining a comprehensive understanding of these complexities can offer significant perspectives to improve the ability to withstand cyber threats and protect digital systems in our progressively interconnected global environment. By analysing how authoritarian governments shape cybersecurity discussions, scholars can devise tactics to oppose their influence and advocate for a more open, comprehensive, and responsible approach to global cybersecurity governance.

Sukumar, Broeders [2]’s research provides a perceptive analysis of the prevalent informality that defines the worldwide cybersecurity regime. The authors emphasise the significance of understanding the nuances of informal governance institutions by closely examining the relationships between states, non-state actors, and diplomatic procedures. To navigate the complex and evolving digital landscape, a comprehensive understanding of cybersecurity policy and practice is necessary for policymakers and practitioners.

4. Case Studies

Following are three example case studies demonstrating non-state actors’ contributions to cybersecurity resilience.

4.1. Case Study 1: Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration in Creating Cybersecurity Standards

The Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) is a prominent example of non-state actors collaborating to develop cybersecurity standards, including industry experts and academics. The IETF has played a crucial role in formulating technical standards and protocols for the Internet, contributing to establishing cybersecurity norms and best practices. Through open collaboration and consensus-based decision making, the IETF has influenced governance by setting widely adopted standards that enhance cybersecurity resilience on a global scale [64,65].

4.2. Case Study 2: Civil Society Organisations’ Role in Cyber Policy Development

The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a non-profit organisation, has actively participated in shaping cybersecurity governance by influencing policy development and advocating for user privacy and digital rights. Through legal advocacy, public awareness campaigns, and engagement with policymakers, the EFF has influenced the formulation of cybersecurity regulations and guidelines. Their efforts have contributed to establishing norms that prioritise individual privacy and data protection, demonstrating how non-state actors can shape cybersecurity governance through public advocacy and engagement [66,67].

4.3. Case Study 3: Industry-Led Collaborative Initiatives for Cyber Resilience

The Cyber Threat Alliance (CTA), a coalition of cybersecurity companies, exemplifies successful non-state actor contributions to cybersecurity resilience. The CTA has significantly influenced cybersecurity norms and governance by sharing threat intelligence, collaborating on research, and developing best practices. Their collaborative efforts have established industry-wide standards for threat information sharing and collective defence, showcasing how non-state actors within the private sector can proactively shape cybersecurity governance and resilience strategies [68,69,70].

These case studies demonstrate the tangible impact of non-state actors in shaping cybersecurity norms and governance, highlighting their pivotal role in enhancing cyber resilience through collaborative initiatives, policy advocacy, and technical standardisation.

5. Discussion

This study explored changes in managing cybersecurity, focusing on how non-state actors shape global safety. It conducted a thorough analysis of the present status of cybersecurity and emphasised the changing role of non-state actors in this field. This research provides useful insights into resolving non-state actors’ complex challenges in cybersecurity. It highlighted the increasing risks of cyber threats such as supply chain attacks, advanced persistent threats, ransomware, and vulnerabilities on the Internet of Things. It dived into how entities like terrorist organisations exploit cyberspace to pursue their objectives, challenging conventional security methods. Additionally, this study examined how informal processes influence the development of cybersecurity standards. Underlining the significance of fostering collaboration between governmental and non-governmental entities to establish robust security measures, emphasising the role of cyber diplomacy in engaging stakeholders to enhance cybersecurity initiatives.

Our research findings underscored the importance of implementing novel strategies to counter evolving cyber threats while recognising the impact of organisations on diplomatic relations. It emphasised how cooperative approaches complement traditional governance frameworks for effectively addressing cyber challenges. Moreover, this study scrutinised how countries and international organisations approach cyber threats comprehensively. Focusing on the geopolitical implications of managing such challenges, including disparities in technology governance and cooperation, stresses the significance of recognising the geopolitical dimensions of cybersecurity governance to inform the development of policies and strategies tailored to specific geopolitical environments. Furthermore, the analysis emphasised the value of public–private partnerships in enhancing infrastructure resilience against cyber threats. By facilitating information sharing, resource allocation, and response coordination, these partnerships leverage expertise and resources from both the public and private domains, promoting a shared sense of accountability among stakeholders to tackle cyber challenges.

The difficulties in coordination that non-state entities face are a significant aspect that was emphasised. The obstacles encompass various interests, differing levels of competence, and conflicting aims. To overcome these obstacles, enhancing communication, fostering transparent collaboration, and building mutual trust among all parties involved is necessary. This research highlights the significance of policymakers in establishing multi-stakeholder forums and partnerships by emphasising the necessity for improved collaboration. Moreover, offering monetary and regulatory rewards can motivate collaboration between state and non-state actors, promoting a more harmonious cybersecurity ecosystem.

Furthermore, this study highlights the essential need for capacity-building programmes to improve cybersecurity knowledge and resilience. Training programmes, seminars, and information exchange activities are recognised as valuable methods to enhance the capacity of both state and non-state actors to counter cyber threats. By allocating resources to enhance their capabilities, stakeholders can better equip themselves to tackle the ever-changing cybersecurity threats.

5.1. Study Limitations and Future Works

The critique and ideas presented offer significant insights into prospective areas for additional investigation and enhancement within the research on cybersecurity and the involvement of non-state actors. A comprehensive examination of non-state actors’ techniques and optimal methods to overcome coordination issues and improve cybersecurity efforts requires thorough investigation. This research could offer practical insights for stakeholders aiming to enhance collaboration in the cybersecurity area by including case studies or empirical evidence, which would provide tangible examples of effective ways. This would facilitate the connection between theoretical concepts and practical implementation, allowing stakeholders to convert abstract frameworks into practical plans.

Also, a more in-depth analysis of the socio-political and economic elements that contribute to the development of cyber threats would enhance the research by offering a more elaborate comprehension of the fundamental forces that shape the cybersecurity environment. By analysing the broader framework in which cyber threats arise, policymakers and stakeholders can devise more focused and efficient measures to tackle emerging concerns. This comprehensive strategy can aid in reducing risks and developing resilience in a progressively interconnected and intricate digital setting.

Additionally, it is crucial to investigate possible frictions and disputes between state and non-state actors in cybersecurity to foster increased cooperation and confidence. By openly recognising and actively confronting these obstacles, the individuals and groups involved can strive towards constructing more comprehensive and collaborative cybersecurity frameworks. It is necessary to have a sophisticated comprehension of the varied interests and motivations that influence different individuals and take proactive steps to reduce confrontations and encourage productive discussions.

Furthermore, examining the involvement of international organisations and multilateral frameworks in promoting global collaboration in cybersecurity is crucial since this is essential for navigating the intricate geopolitical environment. By analysing the efficiency of current procedures and identifying areas that require enhancement, the research can provide valuable insights to enhance international collaboration and coordination in addressing cybersecurity matters. This involves investigating ways to improve the exchange of information, develop skills, and align policies on a global scale.

It is crucial to offer specific suggestions to policymakers and stakeholders on how to put forward recommended solutions and evaluate their efficacy. This is necessary for turning research findings into tangible results. This research provides practical assistance on policy formulation, implementation methodologies, and performance measurements, enabling stakeholders to enhance cyber resilience proactively. This necessitates a practical strategy that harmonises academic understandings with practical issues, guaranteeing that suggestions are achievable and influential.

Future studies should investigate the changing dynamics of informal governance. Examining how these forces shape and impact cybersecurity governance worldwide will be essential in formulating efficient policies and frameworks to tackle rising cyber threats. By further investigating the complexities of informal governance, researchers can provide valuable insights that inform and direct efforts to enhance cybersecurity resilience and protect digital infrastructures in a progressively interconnected global environment.

5.2. Recommendations for Stakeholders

The changing dynamics of cybersecurity and the growing risks posed by threats underscore the need for a united and forward-thinking approach from both government bodies and companies. The following high-level recommendations are put forth to address cyber threats that relate to geopolitics:

Increased Cooperation and Collaboration: A critical step is enhancing the collaboration between government and non-governmental entities to establish robust and adaptable measures. This collaboration should include engaging in diplomacy and implementing innovative strategies to tackle emerging threats. Measures could involve creating channels for sharing information and coordinating responses.

Engaging with Non-State Actors: Governments should acknowledge the influence of actors such as international non-governmental organisations, businesses, and civil society groups in cybersecurity governance. Collaborating with these actors and utilising their skills and resources can significantly enhance cybersecurity efforts.

Adaptation to Geopolitical Contexts: Understanding geopolitical environments that encompass political, social, and economic aspects is essential for shaping effective cybersecurity frameworks. Governments and businesses should customise their strategies and regulations to protect their digital realms based on the geopolitical factors at play.

Flexibility in Governance Methods: Embracing informal partnerships and adaptable governance methods is crucial to complement traditional structures in cybersecurity governance. This flexibility allows for prompt responses to changes in threats and weaknesses, making it easier to navigate the complexities of geopolitics.

Enhancing International Cooperation: Considering the varied legal, regulatory, and organisational frameworks governing cybersecurity internationally, fostering cooperation is vital. Governments and businesses must strive towards aligning regulations and exchanging best practices to enhance global digital resilience collectively.

Putting these recommendations into action necessitates a collective effort from government entities, companies, and non-state actors to mitigate the intricate cyber threats and vulnerabilities in the digital warfare era. Policymakers, security professionals, and researchers need to come together to examine the nuanced interplay between geopolitics, governance arrangements/systems, and the rise in cyber threats, setting the stage for a more robust digital landscape. Based on this study, we also recommend the following high-level actions.

In-depth Study of Non-State Actors: An extensive examination of non-state actors is necessary because of their substantial influence on cybersecurity dynamics. Delving deeply into their objectives, capabilities, and strategies can yield critical insights. One approach is to examine case studies of influential non-state actors and their partnerships with state actors in cyber operations.

Investigation of Emerging Threats: Considering the rapidly changing cybersecurity environment, it is imperative to remain informed about emerging threats and vulnerabilities. Subsequent investigations should prioritise the identification and analysis of novel cyber hazards, including those that aim at exploiting nascent technologies such as artificial intelligence, blockchain, and quantum computing.

Assessment of International Cooperation Efforts: It is crucial to evaluate the efficacy of international collaboration mechanisms in tackling cybersecurity threats. This task may entail assessing current frameworks, such as global treaties, accords, and platforms for exchanging information, to determine their strengths, flaws, and areas for enhancement.

Integration of Geopolitical Analysis: Including geopolitical analysis in the study would enhance comprehension of how geopolitical considerations impact state responses and international collaboration in cybersecurity. One such approach is to analyse the geopolitical incentives driving cyber operations, the influence of regional dynamics, and the consequences of power transfers on cybersecurity measures.

Practical Recommendations

Based on this study’s analyses, the following are some practical recommendations that policymakers and cybersecurity experts can make to implement cybersecurity strategies and cooperation models.

Case Studies on Successful Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs): Include detailed case studies or practical evidence of successful PPPs in cybersecurity, highlighting the specific policies, frameworks, and collaborative mechanisms that facilitated positive outcomes. For instance, a case study could analyse a successful cybersecurity PPP in a specific industry or region, outlining the policies and regulations that enabled effective collaboration.

Establish Multi-Stakeholder Forums: Policymakers should prioritise the establishment of multi-stakeholder forums that bring together the government, industry, academia, and civil society to foster transparent collaboration and information sharing on cyber threats and highlight specific steps for initiating and maintaining these forums, such as forming committees, setting agendas, and facilitating regular interactions. They can also create work groups in, for instance, ransomware threats and include the public and private sectors to discuss various challenges, needs, etc.

Capacity-Building Programmes: Provide detailed guidelines for designing and implementing capacity-building programmes, including training workshops, seminars, and information exchange activities. These programmes should feed to both state and non-state actors and focus on enhancing cybersecurity knowledge and resilience. Suggestions for resource allocation, curriculum development, and evaluation metrics for these programmes should be included. Many awareness and training activities can happen online.

Incentivise Collaboration: Offer specific recommendations for policymakers on providing monetary, regulatory, etc., incentives to motivate collaboration between state and non-state actors in cybersecurity. This could involve creating funding schemes, tax incentives, or awards for collaborative initiatives that enhance cybersecurity resilience.

Thorough Investigation of Non-State Actor Techniques: Conduct detailed research on the techniques and optimal methods non-state actors use to overcome coordination issues and improve cybersecurity efforts. Based on the findings, provide actionable insights and practical guidelines to help stakeholders better understand and address these challenges.

Analysis of Socio-Political and Economic Elements: Conduct a comprehensive analysis of the socio-political and economic elements contributing to the development of cyber threats. Offer specific methodologies for policymakers and stakeholders to incorporate this analysis into their cybersecurity strategies, such as integrating economic indicators into risk assessments or conducting political impact analyses on cyber threats.

Recognise and Confront Frictions Between State and Non-State Actors: Guide openly recognising and actively confronting obstacles and disputes between state and non-state actors in cybersecurity. Offer tools and strategies for conflict resolution, promoting productive discussions, and building trust to foster collaborative cybersecurity frameworks.

Enhance International Collaboration through Analysis and Recommendations: Investigate the involvement of international organisations and multilateral frameworks in promoting global collaboration in cybersecurity. Provide specific analysis of the current procedures and identify areas that require enhancement, along with practical recommendations for improving the exchange of information, skill development, and policy alignment on a global scale.

Practical Assistance on Policy Formulation and Implementation: Provide practical assistance to policymakers in formulating, implementing, and evaluating cybersecurity policies. This includes clear steps to propose recommended solutions, evaluate their efficacy, and measure performance (e.g., by creating KPIs), ensuring that all the recommendations translate into tangible results and proactive cyber resilience enhancements.

6. Conclusions

This study used various analyses and provided insights into the complex relationship between cyberspace and the current state of world political cooperation initiatives and the involvement of non-state actors. The review’s findings underline the increasing importance of non-state actors, including cybercriminal groups and commercial cybersecurity corporations, in influencing cybersecurity dynamics alongside state actors. Partnerships between government and non-government entities have become more common. This partnership impacts how governments address cyber threats and define international cooperation efforts. It has also emphasised the significance of efficient international collaboration methods in tackling cybersecurity concerns. Public–private partnerships, information-sharing platforms, and international treaties are essential for promoting collaboration and coordination among stakeholders in the global cybersecurity community. The method and findings of this study can be used to investigate the effects of state responses and national and international cooperation on other digital areas.

In the future, it is crucial for research on this subject to prioritise comprehensive investigations of non-state actors. Future studies should examine emerging risks, evaluate international cooperation efforts, incorporate geopolitical analysis, develop policy suggestions, and have the active involvement of stakeholders. By prioritising these areas, the study can help advance the knowledge and understanding of cybersecurity, provide information for policy decisions, and improve global cybersecurity resilience in the era of digital warfare. For instance, the emerging risk of supply chain attacks (which can greatly impact the public and private sectors) and the collaboration between the state and non-state actors in making proper policy and defining mitigation actions to tackle those attacks should be studied more. The findings of this investigation have significant consequences for politicians, government agencies, cybersecurity professionals, and other individuals responsible for protecting cyberspace. Through a collective and pre-emptive approach, we can tackle the difficulties presented by cybersecurity threats and establish a fortified and robust digital ecosystem that benefits everyone.

Funding

The APC was funded by Anglia Ruskin University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Johnstone, I.; Sukumar, A.; Trachtman, J. The way ahead for multistakeholder cyber diplomacy. In Building an International Cybersecurity Regime; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; pp. 257–265. [Google Scholar]

- Sukumar, A.; Broeders, D.; Kello, M. The pervasive informality of the international cybersecurity regime: Geopolitics, non-state actors and diplomacy. Contemp. Secur. Policy 2024, 45, 7–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Rethinking Chinese multistakeholder governance of cybersecurity. In Building an International Cybersecurity Regime; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; pp. 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Cîrnu, C.-E.; Rotuna, C.; Vasiloiu, I.-C. Comparative Analysis on Cyber Diplomacy in EU and US. Rom. Cyber Secur. J. 2023, 5, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukumar, A. The geopolitics of multistakeholder cyber diplomacy: A comparative analysis. In Building an International Cybersecurity Regime; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; pp. 20–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ampratwum, G.; Osei-Kyei, R.; Tam, V.W.Y. Exploring the concept of public-private partnership in building critical infrastructure resilience against unexpected events: A systematic review. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2022, 39, 100556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]