Abstract

Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Governance is increasingly necessary and present in organizations aiming to improve the maturity of their ICT processes. This paper presents an analysis of the ICT Governance processes of a Brazilian Federal Public Administration agency. To assess the maturity of the ICT Governance processes, we surveyed and diagnosed the processes performed by the agency and organized a series of meetings/discussions to assist in the improvement and modeling of the processes related to the ICT Contract Planning process. As a result, we proposed improvements and identified the maturity level of the existing ICT processes, also assessing the awareness of employees of the General Coordination of Information Technology regarding these processes. Our findings reveal that the agency still needs to implement the following processes: (1) ICT People Management; (2) Business Process Modeling (Automated/to Automate); (3) Change Management; (4) Execution Monitoring of the ICT Projects and Services Portfolio; and (5) ICT Service Continuity Management. We also identified several artifacts that need to be implemented by the agency in different processes and collected survey participants’ suggestions about new processes to improve the maturity in ICT Governance.

1. Introduction

With well-defined governance processes, organizations can gain a strategic advantage over others as they systematically evaluate and improve their processes and services, leading the organization to perform better and, consequently, to be more competitive. There is a link between Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) and improved governance, providing a competitive advantage for organizations and citizens. The adoption of adequate and mature ICT processes, allows managers and their employees to provide services with quality and transparency, especially in relation to the management of public ICT resources [1]. In this context, stakeholders need to manage, measure, and monitor the ICT goods and services offered to citizens. In addition, the decentralization of ICT services should allow the use of practices that improve the supervision and accountability of poor management of ICT resources by the Federal Public Administration, considerably mitigating the monopoly of information by some stakeholders [2].

ICT Governance should be understood as the use of well-aligned processes to improve the governance of ICT resources by all stakeholders, including business, government, and citizens alike. Improvements in ICT Governance incorporates improvements, among others, on the respect for organizations in a country, citizen participation, and the delivery of quality public goods and services. Thus, ICT processes in organizations, whether public or private, are a basic factor to achieve better efficiency, effectiveness, and competitiveness, since there is no ICT product or service without an associated process or practice [3].

Therefore, understanding how organizations manage their activities and how they formulate and align their ICT processes, becomes an essential factor for organizational success. Thus, this work aims to diagnose the ICT practices and processes of a Brazilian Federal Public Administration agency, named the Administrative Council for Economic Defense (Conselho Administrativo de Defesa Econômica (CADE)). A diagnosis of ICT processes is important to identify the processes that CADE needs to implement in order to manage its ICT resources and improve their performance. In addition, CADE needs to improve its ICT processes, optimize the use of ICT resources and reinforce best practices in relation to ICT management so that the organization can achieve its goals and excel in providing services to other government agencies and the citizens. The main goal is to analyze and verify the ICT processes of CADE’s General Coordination of Information Technology (Coordenação-Geral de Tecnologia da Informação (CGTI)) and to carry out a compliance analysis of the ICT Solutions Contract Planning process with the rules that govern ICT solutions outsourcing within the scope of Information Technology Resources Management System (http://www.sisp.gov.br/) (Sistema de Administração dos Recursos de Tecnologia da Informação (SISP). The diagnosis and conformity analyses were carried out by the research team from the University of Brasília (UnB) (Decision Technologies Laboratory—LATITUDE), together with CGTI staff members, using a multi-methods approach [4]. The approach used strategies that involve data collection to better understand the problems in the investigated context. The data collection involved both quantitative and qualitative information and were carried out through a survey with employees of the agency and interviews with stakeholders.

The main contribution of this work was to identify the current scenario of CADE in relation to its ICT Governance processes, mainly in relation to the processes already implemented, as well as ICT processes that need to be fully implemented. The artifacts of each ICT process were also evaluated, in order to allow CADE to have an ICT Governance maturity level appropriate to the needs of the Federal Public Administration (APF). In addition, we carry out a compliance analysis and propose improvements in the modeling of the ICT Solution Contract Planning process, in accordance with the normative instructions in force in the country. Our findings allowed CADE to define and prioritize the ICT processes that need to be implemented to improve its performance in the provision of ICT services.

This article is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the contextualization of the concepts of Governance, Risk Management, and ICT Services Outsourcing (ITO), as well as related works. Section 3 presents the methodology used to perform this research. Section 4 presents the results obtained in this research, as well as a discussion about its results and the lessons learned during it. Section 5 presents threats to the validity of the results. Finally, Section 6 presents the conclusion of this work, as well as suggested future work.

2. Background and Related Works

2.1. Governance

The term governance has become increasingly discussed and practiced by organizations. According to the Brazilian Institute of Corporate Governance (Instituto Brasileiro de Governançã Corporativa (IBGC)) [5], the growth, evolution, and complexity of organizations, as well as the transformations of the contemporary world, lead to the need to better define roles, rules, and processes. Governance has applications in different areas of knowledge, with different meanings. In the corporate area, Fiorini et al. [6] explains governance as a consequence of the evolution of corporate societies that led to the separation of ownership and management. Between the owners of the companies and those hired to manage them—the managers—, conflicts of interest arose, called agency problem, which is one of the main points contributing to the emergence of corporate governance [7]. According to the IBGC [5]: “Corporate Governance is the system by which companies and other organizations are managed, monitored and encouraged, involving the relationships between partners, the board of directors, supervisory and control agencies and other stakeholders”.

In recent years, one of the areas that have most evolved was Information and Communication Technology (ICT), not only in the technical scope but also in the strategic scope. Tuzzolo [8] states that, without a mature ICT organization that promotes a competitive advantage through its processes, there is no company that can remain competitive in any market. According to Haes and Grembergen [9], ICT has become crucial in companies’ support, sustainability, and growth. Previously, boards of directors and executives could delegate, ignore, or avoid ICT decisions. Today, in most sectors and industries, such attitudes are impossible, as companies increasingly depend on ICT for their survival and growth.

Weill and Ross [10], aiming to capture the simplicity of ICT Governance, defines it as “the specification of decision rights and the framework of responsibilities to stimulate desirable behaviors in the use of ICT”. The authors also explain the important distinction between governance, which determines who makes decisions, and management, which is the process of making and implementing decisions. According to them, effective ICT Governance must address three questions: What decisions must be made to ensure the management and effective use of ICT? Who should make these decisions? And how will these decisions be made and monitored? [10].

In the last few decades, many best practices models for ICT have been developed. Such models help to implement ICT Governance, but they are not ready-made recipes. To use these models, each organization must design its own ICT process architecture. Among the reference models on the market are the ISO/IEC 38500 [11] and the Control Objectives for Information and Related Technologies (COBIT) [12]. ISO/IEC 38500 provides six principles, namely: (1) Responsibility, (2) Strategy, (3) Acquisition, (4) Performance, (5) Compliance, and (6) Human Behavior; with the objective of guiding the leaders of organizations on the effective, efficient and acceptable use of ICT within their organizations. The standard also presents a model for so-called good ICT Governance, whereby ICT is governed through three main tasks: (1) Evaluation, (2) Management and (3) Monitoring [11]. The COBIT governance structure based on an open and flexible conceptual model, aligned with the main standards, presents six principles for building a governance system: (1) Provide Stakeholder Value, (2) Holistic Approach, (3) Dynamic Governance System, (4) Governance Distinct From Management, (5) Tailored to Enterprise Needs and, (6) End-to-End Governance System. COBIT is organized into 40 management and governance objectives that are grouped into the following domains: (1) Evaluate, Direct, and Monitor; (2) Align, Plan and Organize; (3) Build, Acquire and Implement; (4) Deliver, Service and Support; and (5) Monitor, Evaluate and Assess [12].

In light of the digital transformation and constant evolution of ICT, public organizations are seeking to promote the engagement of citizens in their organizational processes [13,14]. The most curious aspect of this process is that the challenge of digital transformation is not a technological one, but that of directing efforts towards structural changes in the organization of government and society [15,16]. In Brazil, Decree N° 8638 of 15 January 2016, institutes the Digital Governance Policy within the scope of the Federal Public Administration and presents the following definition for Digital Governance: “The use by the public sector of information and communication technology resources with the objective of improving the availability of information and the provision of public services, encouraging the participation of society in the decision-making process and improving the levels of government responsibility, transparency and effectiveness” [17].

According to Cunha [18], assuming that the reason for the government’s digital transformation is the effective provision of public services to stakeholders, it is possible to infer that overcoming the challenges related to the Digital Transformation of public services is essential; therefore, it may represent one of the most representative tasks for the creation of the digital economy in our country. Despite the various strategic instruments created for the purpose of promoting digital transformation in the public sector, such as Decree N° 9319 of March 2018, which institutes the national system for digital transformation and establishes the governance structure for the implementation of the Brazilian strategy for the digital transformation; Judgment 1468 of July 2017, which resulted from an operational audit in which objectives were to identify the panorama of digital public services provided to society and evaluate the existing actions in the federal government to increase its offer; and the recommendations of the Organization for Cooperation and Economic Development (OECD), which gathered a set of recommendations aimed at countries that intend to develop digital government initiatives. The essential recommendations proposed, mainly by the OECD, are not being implemented or are evolving as if some adjustments were capable of creating the integrated environment that digital transformation requires.

ICT Governance

According to ISO 38500 [19], ICT Governance processes are the necessary resources to acquire, process, store, and disseminate information. It is the system that directs and controls ICT resources. In addition, it involves assessing and guiding the use of ICT to support the organization and monitoring its use to achieve organizational goals. ICT Governance includes the strategy and policies for using ICT within an organization [20].

On a continuous basis, over the past 30 years, the Federal Public Administration has presented various instruments, which sought to modernize the internal management of organizations and the service provided to citizens, including through the adoption of ICT. The objective of SISP is to plan, coordinate, organize, operate, control, and supervise the information technology resources of APF’s agencies and entities. On 4 April 2019, Ordinance Number 778 was published, which determines that the agencies and entities that are part of the SISP must adopt measures for the implementation, development, and improvement of ICT Governance. The implementation of ICT Governance must be in line with the following principles: focus on stakeholders, ICT as a strategic asset, management for results, transparency, accountability, and compliance [21], according to the ordinance on the implantation of ICT Governance in the agencies and entities belonging to SISP [22].

In the case of Brazilian public companies, due to administrative complexity and budgetary constraints, adopting an ICT Governance model and implementing it in its entirety can be a difficult and very long project [23]. Rodrigues and Vieira [23] carried out a case study with the Social Security Information Technology Company (Dataprev), a public company in which its mission is to work with other public institutions in government actions in the scope of social security and through sustainable ICT solutions. In order to assess the suitability of COBIT [12] to the Dataprev ICT structure, the authors applied a questionnaire to employees of the Dataprev Operations and Telecommunications Department, containing two questions. The first assessing which of the 34 objectives of COBIT would be the most relevant for the company, and in the second question the respondents would indicate which of these objectives were already practiced by Dataprev. The authors concluded that among the 34 objectives of COBIT, 50% were considered relevant for Dataprev, and among these 50%, only 5 were not yet practiced by it, namely: (1) Human Resources Management; (2) Quality Management; (3) Change Management; (4) Definition and maintenance of service level agreements (SLA); and (5) Configuration management.

According to Silva et al. [3], any decision made by the ICT area has a direct impact on the organization’s business; likewise, the strategic decisions of the organization directly impact the ICT area. Thus, alignment and integration between business Strategic Planning (SP) and ICT Strategic Planning (ICTSP) are necessary to achieve the organization’s goals. Among the Federal Government’s initiatives to implement, control, and monitor ICT Governance in APF’s agencies and entities, the ICT Governance Index (iGovTI) stands out, a survey carried out through questionnaires by the Federal Court of Accounts (Tribunal de Contas da União (TCU)) in order to discover the maturity level of the APF’s agencies [24]. The ICT Governance in the APF is a subject little discussed in the academic environment in Brazil, Silva et al. [24] proposed the creation of an optional discipline that addresses concepts of ICT Governance aimed at APF and the dimensions of ICT Governance suggested by TCU.

It is also important to ask how the organization can be sure that its ICT Governance processes are effectively in compliance with legislation, regulatory agency regulations, and best international management and governance practices. Clara et al. [25], in order to verify how a public company maintains ICT Governance compliance, carried out an analysis of the elements that guide the ICT Governance regulatory compliance audit. The elements were identified from the following sources: literature review, legislation, TCU standards, and ISO/IEC standards, as well as guides to good ICT Governance practices. In addition, the study sought to investigate and verify the applicability of the elements in a large company of the Federal Public Administration, concluding that the elements from supervisory and regulatory agencies, especially those related to the TCU rules, have priority in being followed by the organization.

2.2. Service Outsourcing

The operations of institutions, public and private, require various auxiliary services to the core business of the organization. A practice present in most industries and state entities is the contracting of services by third parties, commonly known as service outsourcing. In the public sector, these contracts can be understood as an economic relationship between actors, in which the challenge of public management is to align the public benefit with the institutional rules and the conditions of the service market, going through the three phases of the contract [26].

The first phase of the contracting process considers the decision to produce a service in-house or to outsource it. This is cared out considering the transaction costs, the competitive conditions of the market and identifying the possible suppliers. The second phase deals with the selection of service providers, usually carried out in a bidding process, with the need to establish the service provision contract. After a supplier is hired, public managers must change their focus to contract management, monitoring, and controlling the quality of the service provided [26].

Lacity et al. [27] performed a literature review and evaluated 164 articles. Seventy-one of them used a quantitative approach, 80 a qualitative one, and 13 a mixed approach. The authors identified 150 relevant variables that should be taken into account when contracting ICT services and examined 741 relationships between these variables. Most of the relationships (433) were considered positive, indicating that an increase in the independent variable leads to an increase in the dependent variable. The authors concluded that these variables, such as cost reduction and confidence, are factors strongly correlated with the decisions and results of a process of ICT outsourcing. It is worth mentioning that several of the variables and relationships analyzed comprise the process of outsourcing any service, such as the decision to contract or not and the planning and management of the contract, among others.

Karimi-Alaghehband and Rivard [28] showed a greater focus on the capabilities of the ICT services contractor when analyzing the competencies directly linked to ICT outsourcing and questioned their influence on the success of the service contract at the organization level. The authors proposed a model to test three macro hypotheses about the relationship between some ICT service contracting capabilities and successful contracting. The model was validated based on a survey carried out with 102 Dutch companies, which allowed them to conclude that the Orchestration and Detection capabilities are the most important for successful ICT contracts.

Service Outsourcing According to Brazilian Legislation

The Contracting Services’ flow under Brazilian law is governed by the IN 01/2019 and has three distinct phases: (i) hiring planning; (ii) selection of the supplier; and (iii) contract management. In the first phase, the hiring planning is carried out and has three steps. In the first one, the Hiring Planning Team is created, which defines the roles and responsibilities of each member, and at the end of this step, prepares the Demand officialization Document (DOD), aiming to explain the hiring needs in terms of the agency’s business. Then, the Contract’s Preliminary Technical Study is prepared, which aims to identify and analyze the scenarios to meet the demand contained in the DOD, in addition, to demonstrate the technical and economic feasibility of the solutions identified. The last step consists in the elaboration of the Technical Terms of Reference or Basic Project (TRPB), an indispensable document in which it must contain all the technical elements needed to ensure the cost evaluation by the federal public administration.

The next phase consists of the selection of the supplier that receives the public bidding as input and generates a signed contract as an output so that this contract is public through the publication of the contract extract. Currently, at this phase, the relevant rules must be observed, including the provisions of Law Number 8666/1993, Law Number 10,520/2002, Decree Number 9507/2018, Decree Number 3555/2000, Decree Number 5450, of 2005, Decree number 7174, of 2010, and Decree number 7892, of 2013 (https://www.gov.br/governodigital/pt-br/contratacoes). Generally, this phase’s steps consist of forwarding the TRPB to the area responsible for the contracting process and ends with the publication of the bidding result after adjudication and approval. Finally, the last phase, contract management, begins with the signing of the contract by both parties involved and the appointment of members to the contract’s inspection team.

2.3. Related Works

Information and Communication Technology (ICT) has increasingly played an important role in organizations, regardless of the category (public or private) given that most transactions are conducted in computerized environments. However, due to the level of complexity of ICT, there is a difficulty in obtaining understandable answers to questions about the decision-making roles in the ICT area in public and private organizations. Mendonça et al. [29] assessed the participation of ICT managers from public and private organizations in the alignment and strategic ICT decisions based on the ICT Governance Arrangement Matrix. In private organizations, managers have greater participation in strategic ICT decisions, and in public organizations, managers participate more actively in business strategy decisions. In general, the authors concluded that the organization’s most strategic decisions (not necessarily ICT) have the reasonable participation of members of the technology team. Regarding the aspects of ICT decisions, strategic or technical, organizational managers leave the decisions to ICT managers, mainly in terms of infrastructure and architecture.

Klumb and Azevedo [30] investigated the managers’ view and the impacts generated in the internal work processes of the Regional Electoral Court of the State of Santa Catarina (Tribunal Regional Eleitoral de Santa Catarina (TRE/SC)), after the implementation of ICT Governance practices. The results showed that there was an increase in efficiency, agility, and quality of the services made available to users by the Information Technology Services Center, reflecting positively on the quality of the services provided. The authors also identified the development of a more managerial view of ICT, through performance indicators, which provides greater effectiveness in the decision-making process. However, despite the positive points, the managers also pointed out some weaknesses, one of which was caused after the implementation of the COBIT processes, linked to communication between technical areas and between higher levels.

Fontana et al. [31] analyzed the participation of managers in decision-making rights and contribution to ICT strategies in a large, private company in the state of Rio Grande do Sul. For this, the political archetypes of ICT Governance (Business Monarchy; IT Monarchy; Feudalism; Federalism; IT Duopoly; and Anarchy) were considered in combination with the five critical ICT decisions, classified as typical governance arrangements for: ICT principles; ICT architecture; ICT infrastructure strategies; business application needs; and ICT investment and prioritization. The authors considered from the perspective of who makes the decision and who contributes to the decision. The results showed that the company presents a similar behavior regarding the decision-making process for all five analyzed decisions. It was also noticed that most of the key decisions related to ICT Governance are decided by ICT duopoly and the ICT monarchy contributes predominantly to the determination of these decision making. Finally, the results showed that there is no consensus between which of the ICT archetypes has greater participation in the process and in the contribution to decision making in the company.

Regarding the best practices for ICT Governance, Canedo et al. [7] presented an ICT Governance Kit to the State Companies Coordination and Governance Secretariat (Secretária de Coordenação e Governança das Empresas Estatais [SEST]). The kit comprises a targeting instrument and a set of conditioning practices, with the objective of developing and implementing improvements in ICT Governance in state companies of the Federal Public Administration. The kit was structured in such a way as to enable the identification and assessment of the company’s business capabilities and needs, considering the scope of the objectives and goals of each state-owned company. Thus, based on the Integrated Maturity in Training Model (Modelo Integrado de Maturidade em Capacitação [MIMC]), the ICT Governance kit was divided into three kits, namely: Kit 1 (with its processes being considered at maturity level 2), Kit 2 (with its processes considered with maturity level 3) and Kit 3 (processes considered with maturity levels 4 and 5).

In another study, Canedo et al. [32] presented a report on the implementation of the ICT Governance Kit processes at the Brazilian Agency for the Management of Guarantees and Guarantee Funds (Agência Brasileira Gestora de Fundos Garantidores e Garantias (ABGF)). Through a survey, brainstorming, semi-structured interviews, and a focus group, the authors had the perception of ABGF’s ICT managers and team in relation to the ICT Governance processes proposed in the kit, in addition of allowing the classification of the maturity level of the ICT Governance processes in the company. Among the results achieved by the study, was the fact that the execution of the kit processes also allowed the identification of a new process that was not initially contemplated in the Kit, causing this process and its artifacts to be incorporated into the Kit.

With regard to risk management, the work of Júnior and Irapuan [33] aimed to identify new and potentialized risks in ICT projects in local teams, given that, according to the authors, these projects have a degree of technological uncertainty during their execution due to continuous technological evolution. Thus, a survey containing the main risks of projects was carried out based on the literature, in addition to listing the main risks identified by management in ICT projects. The results showed that the main risks identified in the literature are related to a volatile environment, lack of technical competence, lack of support to users, and simultaneous organizational changes. Similar works have also been published previously by Nakashima and Carvalho [34], Wallace, and Rai [35]. Finally, the study by Souza et al. [36] presented a bibliographic review that provided subsidies regarding the vulnerability of ICT. It provided a vision of how future research could, through the use of indicators, measure the degree of public institutions’ commitment to ICT Governance and the Information Security Risk Management.

More recent works, such as the one published by Saeidi et al. [37], focused on examining the influence of Corporate Risk Management (CRM) and Competitive Advantages (CA), controlling the role of ICT dimensions, both in the strategic area and in the corporate area. To this end, the authors surveyed Iranian companies and obtained 84 questionnaires containing valid answers. Thus, the results showed that CRM has a positive relationship when compared to CA. In addition, the data showed that the ICT strategy and structure had a direct effect on CA and a moderate effect on the CRM relationship.

Regarding contracting and contract management, Oliveira et al. [38] identified the variables related to efficient contract management that lead a public company to reduce costs, and improve the quality of the contracted service. The authors carried out descriptive and qualitative research through an interview with managers from five regional offices of the investigated public company. The results showed the existence of nine specific variables for this type of activity, which were not yet referenced in the literature, the main ones being: (a) control of the validity of contracts, (b) compliance with the processing deadline of the additive terms’ preparation process, (c) regularity control of the process documentation for issuing an additive term. Prior to this study, other studies suggested efficient management to reduce costs and improve the quality of services provided by companies [39,40].

In this same domain, Medeiros et al. [41] focused on conducting an evaluation of the quality of services purchased through bidding processes, of the lowest price type, in a city council in the state of Rio Grande do Sul. The authors also conducted a survey of the main bidding processes and sought to understand the legislation in force and the bidding modalities most used by the institution. The authors applied a questionnaire to 72 city council staff and the results obtained showed that the quality of the products, although they performed the work for which they were intended, is inferior to the expected quality, thus requiring legal procedures for its improvement.

Gudergan et al. [42] described the results of their research to assess how companies are implementing digital transformation, including the strategies employed and the actions taken to achieve large-scale transformations. The authors surveyed companies from different areas, with emphasis on Information and Communication Technology companies, providing services in the following locations: United States, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Oceania. As a result, the authors identified that the companies with the most success in digitizing services integrate information with other key companies, chosen strategically, actively invest in education programs with a specific focus on digitization. They also encourage their employees to provide ideas and develop new business opportunities for the company, have the flexibility to update organizational strategies, invest widely in the implementation of new technologies, in training data scientists, and updating online services. The authors also stated that the digital transformation offers several configuration options that must be adjusted continuously and consistently by companies.

Hund et al. [43] stated that innovation management is an area challenged by the new circumstances created by the widespread digitization that occurs in industries, governments, and companies. Digital technology is an important part of most new services and products. Innovation management is looking for ways to align traditional innovation processes and routines with current demands. To better understand how digitalization challenges the assumptions established in traditional innovation management, the authors conducted interviews with senior managers of companies from various sectors, in order to try to identify the factors that can assist in the transformation of services. The biggest challenges identified related to the delimitation of organizational boundaries, where companies demonstrate the need to establish new processes to allow the connection with external actors and union with partner companies. In addition, another challenge is the fusion of processes and results, in order to allow quick launches and constant improvements in existing services, often obtained through the use of agile methodologies in conjunction with tests performed by users that can provide almost instant feedback to further improve satisfaction. The reduced innovation cycles were also identified as a factor in the transformation of services since companies are forced to deal with frequent and significant changes. Therefore, they not only need to adapt to an environment with rapid changes but also follow the rapid changes in user needs and pressure to serve an increasingly individualized market.

For the digitization of services to reach the largest possible audience, one must understand the different social and economic realities, from which the condition of access to technological resources by low-income citizens and even homeless people are assessed. Harris [44] stated that, for the complete digitization of services, it is not possible to require users to have a regular form of access to computers nor to have skills for the autonomous execution of services, or even to assume that all users have sufficient cognitive skills to browse often complex websites. In this context, different social, material, and circumstantial needs must be assessed before the implementation of new digitized services.

According to Silva et al. [45], good ICT Governance practices aimed at the public sector began to be created or studied with greater emphasis in 2015 and 2016. The authors noted that few countries are contributing to publications in this research area, and 76% of the studies analyzed by the authors in a quasi-systematic review were used only in the academic field and without application in public administration or private companies. Thus, the differential of our work is that we contribute to the literature and the governance of ICT in the Federal Public Administration, presenting a practical case study, carried out in an APF agency in Brazil, presenting an analysis of the conformity of the processes of contracting services and of the maturity of the agency’s ICT processes.

3. Methodology

We followed a multi-methods approach with a sequential exploratory strategy [4]. In the first step, we gathered a set of data from CADE’s ICT processes and their respective artifacts. We conducted an analysis of the processes and rules and laws that regulate the provision of services by government agencies in Brazil, in order to identify the compliance of these processes with Brazilian law. After data collection, we performed an analysis of the ICT processes. From the results of the analysis, we performed the modeling of the respective processes and suggest some improvements in the flow of activities. In the second stage, we conducted a survey with CADE’s employees to identify their perception of the ICT processes that the agency had implemented and or needed to implement. In the third stage, we conducted some interviews with CADE’s stakeholders to discuss the results of the process analysis and survey. As a result, we suggest some processes to be implemented, as well as the sequence in which they should be implemented.

We conducted the case study at the General Coordination of Information Technology (CGTI) of the Administrative Council for Economic Defense (CADE) (http://en.cade.gov.br/), which is a federal autarchy, linked to the Ministry of Justice, with headquarters and venue in the Federal District, which exercises, throughout the national territory, the attributions given by Law number 12529/2011. CADE’s mission is to ensure free competition in the market, being the entity responsible, within the scope of the Executive Branch, not only for investigating and ultimately deciding on competitive matters but also for promoting and disseminating the culture of free competition. CADE’s duties are defined by Law number 12529, of 30 November 2011, and complemented by CADE’s Internal Regulations, approved by Resolution number 20, of 7 June 2017. CADE has three functions:

- (1)

- Preventive: analyze and subsequently decide on mergers, acquisitions of control, incorporations, and other acts of economic concentration between large companies that may put free competition at risk;

- (2)

- Repressive: to investigate, throughout the national territory, and later to judge cartels and other harmful conduct to free competition;

- (3)

- Educational: instructing the general public about the various behaviors that may hinder free competition; encourage and stimulate academic studies and research on the subject, establishing partnerships with universities, research institutes, associations, and government agencies; conduct or support courses, lectures, seminars, and events related to the subject; edit publications, such as the Competition Law Magazine (Revista de Direito da Concorrência) and booklets.

CADE’s CGTI is responsible for decisions related to ICT Governance with regard to Information and Communication Technology Contracting Planning (PCTIC).

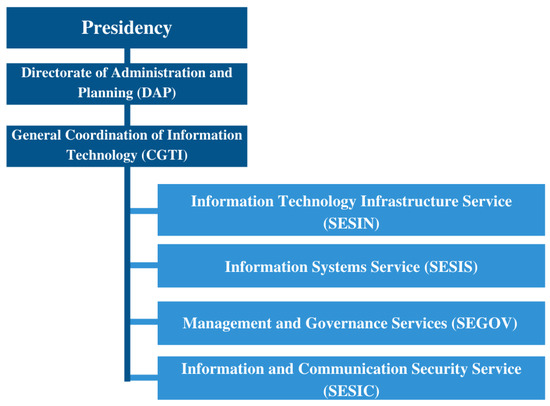

The organizational structure of CADE, according to the Internal Regulations, is composed of the agencies of direct and immediate assistance to CADE’s President; sectional agencies; specific and singular agencies and, a collegiate agency. Among the sectional agencies, there is the Directorate of Administration and Planning (DAP) which, in order to fulfill its powers, is divided into coordinations, among them, the General Coordination of Information Technology (CGTI). CGTI is the sectional unit responsible for managing CADE’s Information and Communication Technology, as shown in Figure 1. CGTI is composed of the following units: Information Technology Infrastructure Service (SESIN); Information Systems Service (SESIS); Management and Governance Services (SEGOV); and Information and Communication Security Service (SESIC).

Figure 1.

CADE’s General Coordination of Information Technology organizational structure.

3.1. Compliance Analysis

The case study was carried out at CADE to analyze the modeling of the Master Plan for Information and Communication Technology (PCTIC) processes, which aims to ascertain the alignment of the contract’s request with CADE’s PDTIC, as well as to perform a comparative analysis of solutions and costs, thus ensuring the optimal use of CGTI resources. The purpose of the processes’ analysis was to verify the compliance of the PCTIC with the Normative Instructions (IN) 01/2019, published on 4 April 2019, and IN202/2019, published on 18 September 2019 [46].

After performing the compliance check, we discussed with the CGTI about which processes should be performed concerning the planning of ICT outsourcing so that all activities of this process are carried out following the processes proposed by IN01/2019 and the CADE’s internal regulations. Thus, the mapped processes provide the necessary information so that CGTI can, in an organized and appropriate manner, define how inputs and materials will be transformed into outputs by the responsible operating unit. In general, the mapped processes make it possible to structure the execution of activities that will be developed by CGTI, always aiming at simplifying, analyzing, and improving the execution of each of CGTI activities, as a way of articulating the permanent search for improvement and performance of ICT Governance, both by the CGTI and by its employees.

3.2. Survey with CGTI Employees

We conducted a survey with CGTI employees to verify what knowledge they had of the ICT Governance processes proposed by Canedo et al. [7,47]. The survey was designed according to the one proposed by Kitchenham et al. [48] and had two stages: (1) the first stage to collect demographic information from the participants; and (2) the second stage with 39 closed questions and an open question to check the knowledge of employees regarding the ICT Governance processes and artifacts. The survey’s questions can be accessed at this URL: https://leomarcamargo.github.io/survey-cade/index.html. In total, all of the 10 CGTI employees responded to the survey, and Table 1 presents the profile of all respondents, in which 60% of CGTI employees were between 41 and 50 years old and 40% between 31 and 40 years old. Ninety percent were men, and only one respondent was a woman (10%). Twenty percent worked at CADE between 5 and 7 years, 40% between 2 and 4 years, and up to 1 year, respectively. In addition to the survey, we conducted interviews with CGTI stakeholders to discuss the results found with the survey in order to understand and resolve some conflicts identified during the analysis of the results.

Table 1.

Profile participants.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Suggestions for Improvements in the Information and Communication Technology Outsourcing Processes

The planning for outsourcing Information and Communication Technology (ICT) solutions aims to ensure alignment of the request to the Information and Communication Technology Master Plan (PDTIC), as well as to perform a comparative analysis of solutions and costs, thus ensuring optimal use of resources. In modeling the processes related to the contracting of ICT solutions, CGTI acts as the ICT area, the sectorial unit responsible for managing Information and Communication Technology and for the planning, coordination, and monitoring of actions related to the ICT solutions of the agency. It must follow the Normative Instruction (IN) IN01, which regulates the process of contracting ICT solutions by the agencies and entities that are part of the Federal Executive Branch’s SISP.

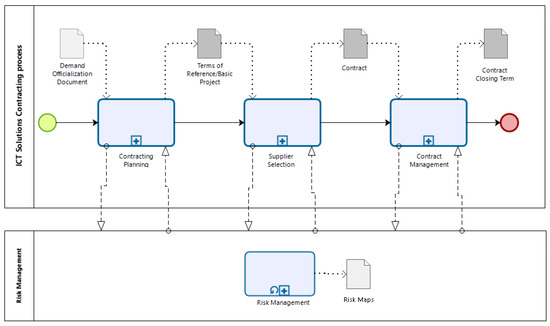

The process of contracting ICT solutions must follow the following phases: (1) Planning of contracting; (2) selection of the supplier; and (3) contract management, in parallel to these phases, risk management activities must be carried out, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Phases of the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) solutions contracting process.

The Contracting Planning process begins with the CGTI receiving the Demand Officialization Document (DOD), prepared by the solution’s Requesting Area, and is concluded with the preparation of the Terms of Reference/Basic Project. The Contracting Planning phase consists of three phases, the institution of the Contracting Planning Team, the preparation of the contracting Preliminary Technical Study, and the preparation of the Terms of Reference/Basic Project.

The Supplier Selection process begins with the Terms of Reference or Basic Project being sent by the Contracting Planning Area to the Bidding Area, and it ends with the publication of the bidding result after the award and approval. It is the responsibility of the Bidding Area team to conduct the main activities of this process. The ICT solution Contract Management process begins with the receipt of the Approved Contract to be signed. This process includes activities to initiate the contract, sign the contract, and execute the Service Order (OS) or Order for the Supply of Goods (OFB). As for the Risk Management process applied to ICT contracting, the purpose is to define the stages of preparation of the Risk Management Map, which must contain, at least: (1) the identification and analysis of the main risks; (2) the assessment and selection of the risk response according to the agency’s risk tolerance; and (3) the registration and monitoring of risk treatment actions.

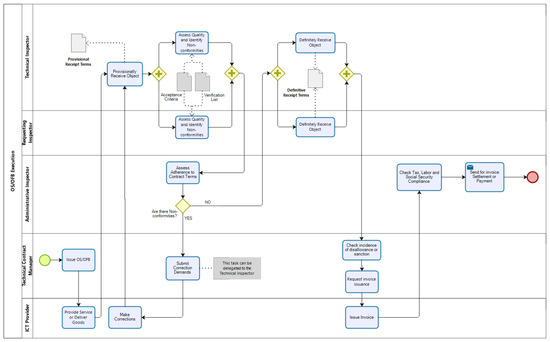

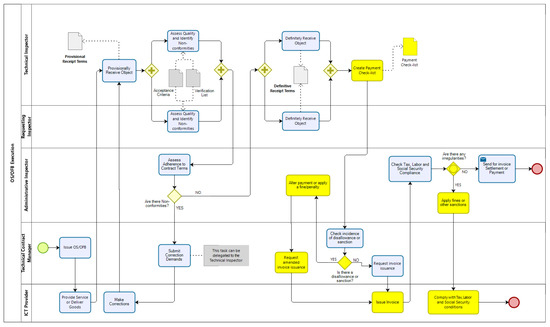

We suggest improvements in modeling in all phases of the process of contracting ICT solutions, checking the compliance of each activity with Normative Instruction IN01 and its respective updates, IN202 and IN40, and also adapting the flows to CADE’s practices and reality. An example of the improvements suggested by the research team to the agency is presented in Figure 3 and Figure 4, which demonstrate the changes made in one of the Contract Management sub-processes, in the OS/OFB Execution sub-process.

Figure 3.

Initial execution of the Service Order (OS)/Order for the Supply of Goods (OFB).

Figure 4.

Execution of the OS/OFB with the suggested improvements.

The changes in the OS/OFB Execution sub-process, shown in Figure 4, consist of 5 new activities, 2 new decision gateways, and 1 new artifact, all indicated in light yellow. The gateways were added to better indicate the two possible results of the processes “Check incidence of disallowance or sanction” and “Check tax, labor, and social security compliance”. The absence of at least two possible results, the existence or not of disallowance, regularity, or irregularity, made these activities meaningless. Thus, the two decision gateways and the 4 processes resulting from their results allow the operationalization of these important checks in the process. The last activity added, “Create Payment Checklist”, refers to the implementation of a compliance checkpoint when moving the process from one area/responsible to another. In the case of the OS/OFB Execution sub-process, the Technical Inspector creates and fills in the Payment Checklist, a new artifact that allows the compliance control of the items of the Definitive Receipt Terms, which will be forwarded to the Administrative Inspector. This new practice increases transparency between areas and makes it possible to establish more clearly the responsibilities for the results of each activity in the process.

4.2. Diagnosis of ICT Governance Processes

This section presents the results obtained in the survey with the responses of CGTI employees. We divide the analysis by the maturity levels of the ICT Governance processes. In Section 4.2.1, the analysis of the basic ICT processes is presented, which have a Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) maturity level equal to 2 [7]. In Section 4.2.2, we present the analysis of the intermediate processes, which have a maturity level of 3 [7], and, finally, in Section 4.2.3, the analysis of advanced processes with a maturity level of 4 and 5 is presented [7].

4.2.1. Basic ICT Processes

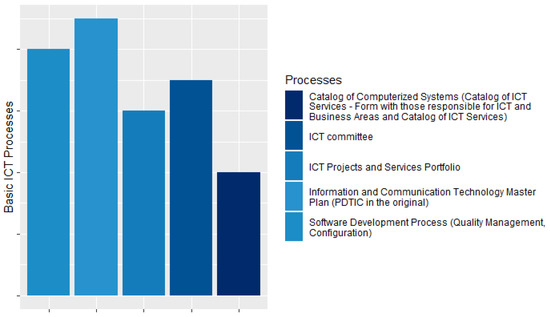

Regarding the processes that include the basic ICT processes for agencies with little or no maturity in ICT, only the ICT People Management process, and its artifacts (Talent Bank; Skills and Competencies; and Role and Responsibility Definition Form) are not implemented at CADE. The Information Technology Master Plan (PDTI) is the process best known to employees, except for a single respondent.These results support the findings of Freitas et al. [49], which affirm that in order to minimize the risks in ICT resource management, all participants must know their in an organization’s PDTI and execute its activities, following the principles and goals defined in the PDTI. All employees who claim to have up to one year of experience at CADE are unaware of the existence of the Catalog of Computerized Systems (Catalog of ICT Services—Form with the Responsible for ICT and Business Areas and Catalog of ICT Services), indicating an alert for the current process of integrating new employees and the CGTI’s team. Figure 5 shows the basic ICT processes that the agency has implemented, according to the responses of the participants.

Figure 5.

Basic ICT processes.

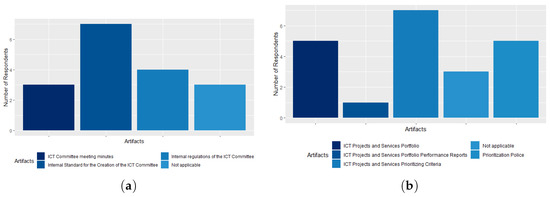

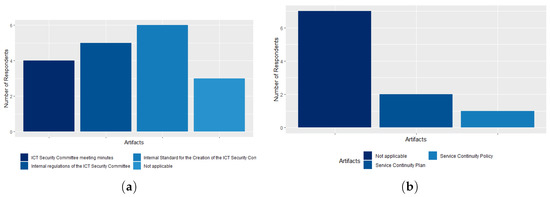

Regarding the ICT Committee process artifacts, only 30% of respondents, the CGTI Coordinator, the Responsible for ICT Governance, and an ICT Analyst, is aware of all the process artifacts, namely: Internal Creation Standard of the ICT Committee, Internal Rules of the ICT Committee, and Minutes of the ICT Committee meeting. Among all ICT Analysts, a function that represents the majority of respondents, only one has knowledge of all artifacts. The Internal Standard for the Creation of the ICT Committee is the most familiar artifact among respondents, 70% of whom claimed to know its existence, as shown in Figure 6a. Regarding the artifacts of the ICT Projects and Services Portfolio process, all respondents said they knew the existence of the ICT Projects and Services Prioritization Criteria artifact. Only 1 survey participant, who has the role of ICT Administrative Assistant, stated that the artifact ICT Projects and Services Portfolio Performance Report is implemented by the agency, as shown in Figure 6b. This finding leads us to believe that this artifact is probably not implemented by CADE and needs to be implemented since it is part of the group of basic processes and artifacts that an agency must have in order to be at least at level 2 of maturity in its ICT Governance processes. As stated by Silva et al. [3], the basic ICT processes must all be implemented by an organization so that it has the minimum maturity required to provide ICT services.

Figure 6.

(a) The ICT Committee process artifacts; (b) the ICT Projects and Services Portfolio process artifacts.

Although the ICT People Management process (Talent Bank; Skills and Competencies; and Role and Responsibility Definition Form) is not implemented in the agency, as all respondents stated in relation to the basic processes that the agency has implemented, two respondents (20%—the head of ICT Governance and an ICT Analyst) stated the existence of the CADE’s Roles Definition Form artifact, as shown in Figure 7a. This answer allows us to conclude that the two respondents did not express the reality of the agency, since the same respondents stated that this process does not exist in the question that addressed the implementation of the process. According to Adam et al. [50], all organizations need to implement the ICT People Management process to ensure the quality of human resources in carrying out ICT activities. In the artifacts of the PDTI process, 60% of respondents stated that the agency has 10 or more artifacts implemented, out of a total of 12 artifacts existing in this process. 20% of CGTI workers stated the existence of all artifacts. Among the 12 artifacts, the least known by the survey respondents is the SWOT Analysis Model, in which only 40% of the participants stated that it was implemented in the agency, as shown in Figure 7b.

Figure 7.

(a) The ICT People Management process artifacts; (b) the Information and Communication Technology Master Plan process artifacts.

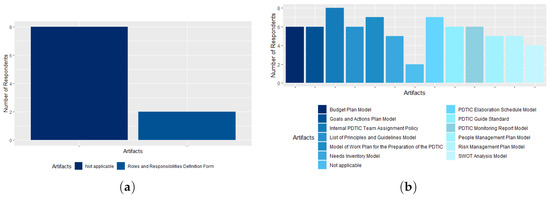

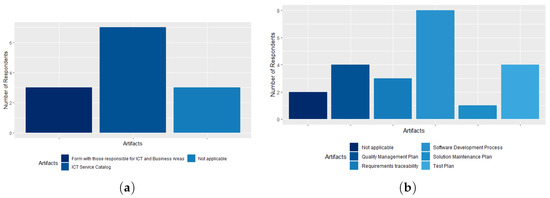

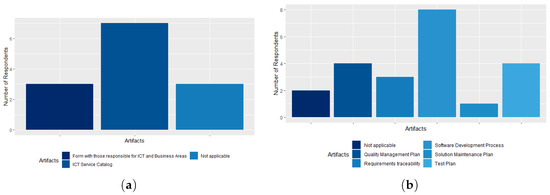

Regarding the Computerized Systems Catalog (ICT Services Catalog) process, 70% of respondents stated that the agency has the ICT Services Catalog artifact. Among them, 30% also affirm the existence of the Form with the Heads of ICT and Business Areas, as shown in Figure 8a. In the artifacts of the Software Development process (Quality Management, Configuration), 40% of respondents stated that the agency has the Quality Management Plan and the Test Plan. For 30% of respondents, the agency also has the Requirements Traceability artifact. The artifact Software Development Process is known to 80% of respondents, as shown in Figure 8b. A single respondent stated that the Solution Maintenance Plan artifact is in place, which may be a warning about whether this artifact is actually implemented in the agency. There are several works in the literature [3,51,52,53,54] which assert the importance of organizations having a well-defined software development process, especially in relation to government agencies, which require maturity level 3 for an organization to be able to provide software development services to any agency of the Brazilian Government.

Figure 8.

(a) The Computerized Systems Catalog (ICT Services Catalog) process artifacts; (b) the Software Development (Quality Management, Configuration) process artifacts.

Regarding the analysis of the basic ICT processes, we can conclude that only the ICT People Management process and its respective artifacts (Talent Bank (Skills and Competencies) and Role and Responsibility Definition Form) are not implemented in the agency. In addition, the ICT Projects and Services Portfolio Performance Reports artifact of the ICT Projects and Services Portfolio process and the Solution Development Maintenance Plan for the Software Development process (Quality Management, Configuration) are also not implemented in the agency.

4.2.2. ICT Intermediate Processes

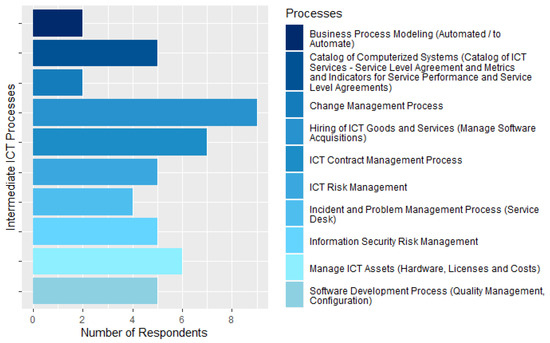

In relation to the processes that contemplate the intermediate ICT processes, which are those that, once implemented, enable the agency to evolve to an intermediate level of maturity—level 3. The most known process among CGTI employees was the ICT Goods and Services Contracting process (Manage Software Acquisitions), in which 90% of the workers stated that the agency has this process in place, followed by the ICT Contract Management Process, known by 70% of respondents. The ICT Risk Management processes, Computerized Systems Catalogs (ICT Services Catalog—Service Level Agreement, Metrics, and Indicators for Service Performance and Service Level Agreements.), Information Security Risk Management and Software Development Process (Quality Management, Configuration) are known to 50% of survey respondents. Only two respondents claimed to know the existence of the Business Process Modeling (Automated/to be automated) and Change Management processes, as shown in Figure 9. This finding may indicate that these two processes are not actually implemented by the agency.

Figure 9.

Intermediate ICT processes.

In the ICT Risk Management process, respondents stated that the agency has all the artifacts of this process, namely: ICT Risk Management Plan, ICT Risk Management Policy, and Information and Communication Security Policy. The information and communication security policy artifact is known to 90% of respondents. Only one respondent (10%) stated that he did not know if the artifacts of this process are implemented by the agency (Not Applicable), as shown in Figure 10a. Kim [55] presented a study discussing the implementation of ICT Governance and its effects on public organizations and the importance of the risk management process in the Korean government. Our study presents results similar to those of the author since almost all CADE employees know and understand the importance of the risk management process. Regarding the ICT Goods and Services Contracting process (Manage Software Acquisitions), there was a uniformity in the responses, the agency has all the artifacts presented (Demand Officialization Document, Model of the Terms of Commitment, Model of the Acknowledgment and Terms of Reference or Basic Project), according to 90% of respondents, as shown in Figure 10b.

Figure 10.

(a) The ICT Risk Management process artifacts; (b) the ICT Goods and Services Contracting process (Manage Software Acquisitions) artifacts.

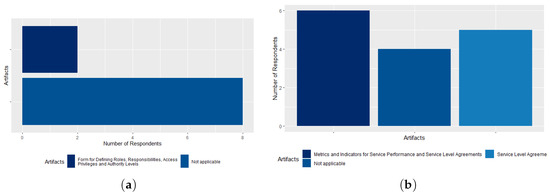

The Business Process Modeling (Automated/to be automated) process is not implemented in the agency, according to 80% of respondents. Strangely, two respondents (20%) stated that the agency has the artifact Form for Defining Roles, Responsibilities, Access Privileges, and Authority Levels implemented, as shown in Figure 11a. Since one of this two respondents stated that the process is not implemented, but that its artifact is, we can conclude that this process and all its artifacts (Form for Defining Roles, Responsibilities, Access Privileges, and Authority Levels; Business Process Modeling Simplification Document) are not implemented in the agency. Fritsch [56] stated in his research that for an organization to have a sustainable life cycle, all its business processes must be modeled, using standard notation, so that all employees of the organization know their activities and responsibilities in relation to the ICT services that the organization offers to its users.

Figure 11.

(a) The Business Process Modeling (Automated/to be automated) process artifacts; (b) the Computerized Systems Catalog (ICT Services Catalog) process artifacts.

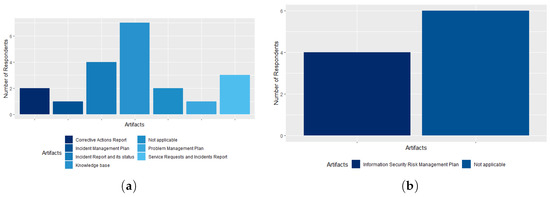

Regarding the Computerized Systems Catalog (ICT Services Catalog) process, 60% of respondents stated that the agency has implemented the Metric and Indicators for Service Performance and Service Level Agreements artifacts, and 50% of respondents said that the Service Level Agreement artifact is implemented at CADE. For 40% of respondents, the agency does not have any of the two process artifacts implemented, as shown in Figure 11b. In the Incident and Problem Management Process (Service Desk) the Knowledge Base artifact is the best known among respondents (70%). The Incident Reports and their Status, Service Request, and Incident Report and Corrective Action Report artifacts are known to 40%, 30%, and 20% of respondents, respectively. The Incident Management Plan and Problem Management Plan artifacts are known to only one survey respondent, as shown in Figure 12a. This finding leads us to conclude that these two artifacts are not implemented by the agency.

Figure 12.

(a) The Incident and Problem Management Process (Service Desk) artifacts; (b) the Information Security Risk Management process artifacts.

Regarding the Information Security (IS) Risk Management process, 60% of the respondents chose to check “Not applicable”, not knowing any of the artifacts of the process. Forty percent of respondents, including the CGTI Coordinator and the Responsible for ICT Governance, stated that the agency has the Information Security Risk Management Plan artifact, as shown in Figure 12b. Thus, we can conclude that the IS Category and Parameter Form and IS Risk Treatment Plan artifacts are not implemented in the agency.

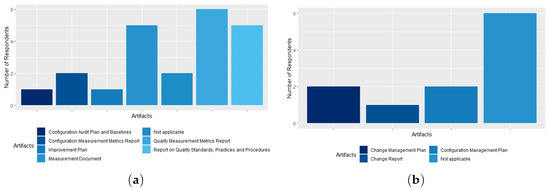

In the Software Development Process (Quality Management, Configuration), 60% of the respondents stated that the agency has the Artifact Metrics of Quality Measurement Report, which is the best known among survey participants, followed by the Document of Measurements and the Report on Quality Standards, Practices and Procedures, both known to 50% of CGTI workers. The Configuration Audit Plan and Baselines, and the Improvement Plan artifacts are known to only 10% of CGTI employees, as shown in Figure 13a. This finding shows that these two artifacts are not implemented at the agency. For 60% of respondents, the Change Management Process artifacts are not implemented by CADE, although the Change Management Plan and Configuration Management Plan artifacts have been recognized by 20% of respondents, and only one respondent stated that the agency has the Change Report, as shown in Figure 13b.

Figure 13.

(a) The software development process (Quality Management, Configuration) artifacts; (b) the Change Management Process artifacts.

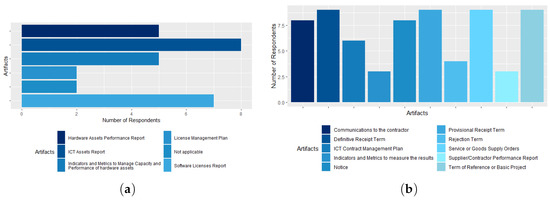

In the Manage ICT Assets (Hardware, Licenses, and Costs) process, the most known artifact among respondents is the ICT Assets Report (80%), followed by the ICT Licenses Report (70%). Fifty percent of respondents stated that the agency has the Indicators and Metrics artifacts to Manage Hardware Assets Capacity and Performance and the Hardware Assets Performance Report. Only 20% of respondents know the License Management Plan, as shown in Figure 14a.

Figure 14.

(a) The Manage ICT Assets (Hardware, Licenses and Costs) process artifacts; (b) the ICT Contract Management process artifacts.

The ICT Contract Management process is the most popular among CGTI workers, four of the ten artifacts in the process are known to 90% of respondents, namely: (1) Terms of Reference or Basic Project; (2) Services or Supply of Goods Orders; (3) Provisional Receipt Terms; and (4) Final Receipt Terms. Only 20% of the servers claimed to know only 2 or 3 artifacts. The Supplier/Contractor Performance Report and Indicators and Metrics to measure results are the least known by the participants, only 30% of respondents stated that the agency has it, as shown in Figure 14b.

Based on the survey findings in relation to the intermediate ICT processes, we can conclude that the processes: (1) Business Process Modeling (Automated/to be automated) and (2) Change Management Process, as well as all of its artifacts, are not implemented at CADE. In addition, the artifacts (a) Incident Management Plan and (b) Problem Management Plan for the Incident and Problem Management process (Service Desk); (c) Categories and Parameters Form for IS Risks; (d) IS Risk Treatment Plan for the Information Security Risk Management process; (e) Configuration Audit Plan and Baselines; and (f) Improvement Plan for the Software Development process (Quality Management, Configuration) are also not implemented by the agency.

4.2.3. Advanced ICT Processes

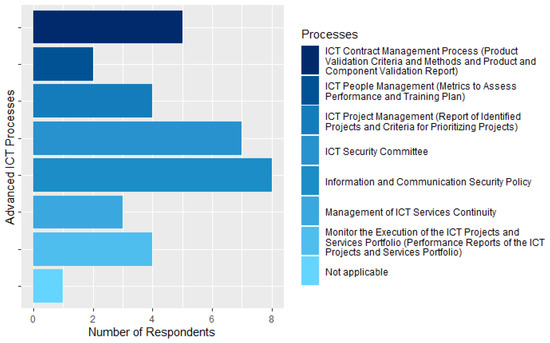

Regarding the processes that contemplate the advanced ICT processes for the agencies that wish to evolve to an improved stage of maturity, that is, to level 4 or 5, only the ICT People Management (Metrics to Evaluate Performance and Training Plan) process and Change Management (Causal Analysis Report) process and all its artifacts are not implemented in the agency. 30% of respondents do not know any of the advanced ICT processes. Another 30% claim that the agency has 6 out of 8 advanced ICT processes. The Information and Communication Security Policy process is the most well-known process among CGTI employees (80%), followed by the ICT Security Committee process (70%). The ICT Contract Management process is known to 50% of respondents. Only 20% stated that the ICT People Management (Metrics to Assess Performance and Training Plan) process is implemented by the agency, as shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Advanced ICT processes.

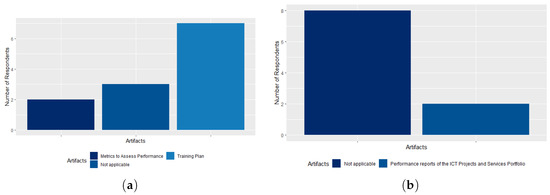

In the ICT People Management (Training, Performance, Roles and Responsibilities) process, 70% of respondents stated that the agency has the Training Plan artifact. The Metrics to Evaluate Performance artifact are known to only 20% of respondents, as shown in Figure 16a. This finding leads us to conclude that this artifact is not implemented by the agency. Regarding the process of Monitoring the Execution of the ICT Projects and Services Portfolio, 20% of the respondents said that the agency has the artifact Performance Reports of the ICT Projects and Services Portfolio and the other respondents (80%) chose by checking “Not applicable”, as shown in Figure 16b. These responses are at odds with the question that addresses the advanced ICT processes, in which 4 participants stated that this process was implemented by the agency, but, with the analysis of the process artifacts, we can conclude that this process is not implemented by the agency.

Figure 16.

(a) The ICT People Management (Training, Performance, Roles, and Responsibilities) process artifacts; (b) Monitoring the Execution of the ICT Projects and Services Portfolio process artifacts.

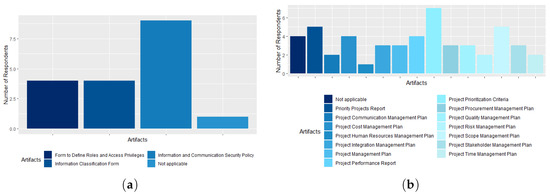

In the ICT Security Committee process, 40% of respondents stated that the agency has all the implemented artifacts. The ICT Security Committee Internal Standard Creation artifact is known to 60% of respondents, followed by the ICT Security Committee Internal Regulation artifact (50%) and right after the ICT Security Committee Meeting Minutes artifact (40%). Only 30% of respondents stated that the artifacts do not apply, as shown in Figure 17a. In the ICT Services Continuity Management process, 70% of respondents chose to check “Not Applicable”, only 20% said the agency has the Service Continuity Plan artifact, and 10%, a single respondent, said that the agency has the Service Continuity Policy artifact, as shown in Figure 17b. Thus, we can conclude that the agency does not have this process and its artifacts implemented.

Figure 17.

(a) The ICT Security Committee process artifacts; (b) the ICT Services Continuity Management process artifacts.

Regarding the Information and Communication Security Policy process, 40% of respondents stated that the agency has the artifacts: (1) Information Classification Form; and (2) Form for Defining Roles and Access Privileges. The Information and Communication Security Policy artifact is known to 90% of respondents, as shown in Figure 18a. Regarding the ICT Project Management process, the most known artifact among respondents is the Project Prioritization Criteria (70% of respondents know it). The artifacts: (1) Priority Projects Report; and (2) Project Scope Management Plan are known to 50% of CGTI employees. Out of the 14 artifacts in the process, 10 are known to 20% to 40% of respondents, namely: (1) Project Integration Management Plan; (2) Project Time Management Plan; (3) Project Cost Management Plan; (4) Project Quality Management Plan; (5) Project Communications Management Plan; (6) Project Risk Management Plan; (7) Project Procurement Management Plan; (8) Project Stakeholder Management Plan; (9) Projects Management Plan; (10) Project Performance Report. The Human Resource Project Management Plan artifact is known to only one respondent, as shown in Figure 18b. Therefore, we can conclude that this artifact is not implemented by CADE.

Figure 18.

(a) The Information and Communication Security Policy process artifacts; (b) the ICT Project Management process artifacts.

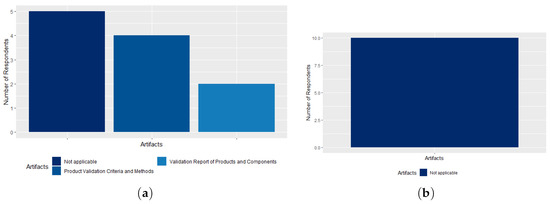

In the ICT Contract Management process 40% of the respondents said that the agency has the Product Validation Criteria and Methods artifact, 20% know the Product and Components Validation Report artifact. The other respondents, 50%, stated that the agency does not have these artifacts, choosing to select the option “Not applicable”, as shown in Figure 19a. This result may be a warning factor regarding the implementation of these artifacts at CADE. As noted in the responses related to the advanced ICT processes, CADE does not have the Change Management process in place. Thus, it also does not have the Causal Analysis Report artifact, according to 100% of respondents, as shown in Figure 19b.

Figure 19.

(a) The ICT Contract Management process artifacts; (b) the Change Management process artifacts.

The survey findings in relation to the advanced ICT processes, allow us to conclude that the processes: (1) Change Management and its artifact, Causal Analysis Report; (2) Monitor the Execution of the ICT Projects and Services Portfolio and its artifact, ICT Projects and Services Portfolio Performance Reports; and (3) ICT Services Continuity Management and its artifacts, Service Continuity Plan, and Service Continuity Policy are not implemented at CADE. In addition, the Metrics to Assess Performance of the ICT People Management process artifact, and the Human Resources Management Plan artifact of the ICT Project Management process are not implemented by CADE.

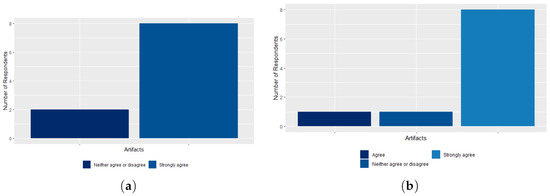

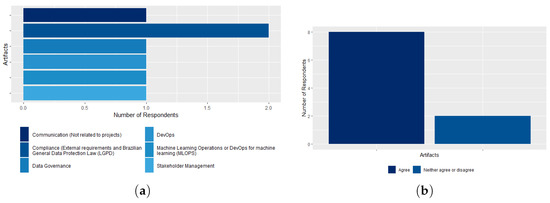

The survey also addressed other issues related to the creation of a working group and the deadlines required to implement the processes at CADE. Thus, 80% of CGTI employees totally agree with the institution of a working group with the objective of implementing the processes most appropriate to the ICT maturity of the agency. Twenty percent were neutral, as shown in Figure 20a. Regarding basic, intermediate, and advanced maturity processes, 90% of the respondents stated that they will contribute to the improvement of the ICT Governance processes at CADE, as shown in Figure 20b, and 80% agree that the maturity processes that were presented are in line with CADE’s reality, as shown in Figure 21b. In addition, the respondents presented some processes that they consider that were not addressed in the survey, in the basic, intermediate and advanced processes, namely: (1) Stakeholder Management; (2) Communication (not related to projects); (3) DevOps (a set of practices and cultural values that aims to reduce the barriers between development and operations teams) [57]; (4) Machine Learning Operations or DevOps for Machine Learning (MLOPS) [58]; (5) Data Governance [59]; and (6) Compliance (External Requirements and LGPD) [60,61,62,63], as shown in Figure 21a. These findings lead us to conclude that it is really necessary to add these processes and their respective artifacts to the set of ICT processes to measure the level of ICT Governance maturity of an agency.

Figure 20.

(a) The perception of CGTI workers in relation to the institution of a working group to implement ICT processes at CADE; (b) the perception of CGTI workers in relation to whether the ICT processes presented will contribute to the improvement of ICT Governance processes at CADE.

Figure 21.

(a) The artifacts suggested by CGTI workers to be added to the CADE context; (b) the perception of CGTI workers in relation to the adherence of ICT processes to CADE.

Regarding the possibility of implementing the maturity processes presented at CADE, 80% of the survey respondents agree that it is possible to implement the processes at CADE, only one (10%) disagreed. Forty percent of respondents disagree that the agency has human resources to implement and monitor the ICT maturity processes and 40% were neutral. Only 20% stated that the agency has enough staff to implement the ICT processes. Regarding the desired time to implement the processes presented, 70% of the respondents indicated 6 months to implement the basic processes, 60% opted for 12 to 18 months for the intermediate processes, and for the advanced processes, 12 months was stated by 80% of respondents.

Only 20% of CGTI employees said they did not know the Information and Communication Technology Master Plan (PDTIC), and 50% said they knew CADE’s Information and Communication Technology Governance Policy (PGTIC). All respondents (100%) claimed to know CADE’s Information and Communications Security Policy (POSIC).

5. Limitations and Threats to Validity

Although the results of this research have been shown to be satisfactory, it presents threats to its validity that cannot be disregarded, since different problems can be caused during the participation of CADE’s employees in carrying out the survey.

The target population of the diagnosis was a small group of participants, considering the size of CADE’s CGTI team, which facilitates the control of the survey application methodology. This contributes to standardize the reproduction of the applied methodology, which can lead to similar results in different contexts. In addition, it is important to note that the qualitative information of the data may vary, as it does not depend on the way the methodology was applied, since the way respondents react to a survey, depends on the context in which they are inserted. Thus, questions related to the respondent’s context can lead to divergent answers, even when we use the same application methodology.

5.1. Internal Validity

The application of the Diagnostic Questionnaire to identify the ICT Governance processes at CADE may not represent the real scenario in relation to its maturity, as well as not presenting all the artifacts that portray the CADE scenario. In response to the questionnaire, some CGTI participants were contradictory in relation to some questions. In order to mitigate this threat, we conducted meetings with the CGTI coordinator and the Responsible for ICT Governance to discuss the survey results and consolidate the participants’ view of all processes and artifacts.

5.2. External Validity

The representativeness of the population (the variety of participants) who responded to the survey was very small since CADE has few employees at CGTI—only 10 employees—and all of them responded to the survey. One way to mitigate this threat would be to reproduce this study with all CADE employees, for example, to include all CADE departments and outsourced employees and to compare their perception of the processes identified by CGTI employees. In addition, it is important to carry out new diagnostics in other federal public administration agencies, with the aim of verifying the adherence of ICT processes and artifacts in different organizations, with specific ICT contexts and needs.

5.3. Construct Validity

The distribution of the set of participants regarding the functions or positions of the participants in CADE may affect the results; however, most responses were obtained by positions of leadership or those responsible for the ICT processes. It is important to highlight that there is a risk that the answers are true but not consistent with the practice, such as affirming the existence of a process or artifact in which it formally exists on paper and that in practice, CADE does not execute it.

6. Conclusions

In this work, we carried out an analysis of the ICT Solution Contract Planning processes and proposed improvements in these processes so that different activity flows are adapted to CADE’s practices and reality. In addition, we carried out a diagnosis in the ICT processes of a Federal Public Administration agency in which we identified several processes and artifacts that were not implemented by the organization, such as the ICT People Management process and its respective artifacts, as well as the ICT Project and Service Portfolio Performance Report artifact that belongs to the ICT Project and Service Portfolio process and the Solution Maintenance Plan artifact for the Software Development process (Quality Management, Configuration).

Despite this, the results showed us that more than half of the respondents are aware of the existence of other processes, such as the ICT Goods and Services Contracting (Manage Software Acquisitions) process and the ICT Contract Management process. In addition, the respondents are aware of additional artifacts from different processes, for example, the artifacts of the Internal Standard for Creation and Regulation of the ICT Security Committee process. It is important to note that both scenarios (artifacts and processes identified or not) occurred regardless of the maturity level at which the processes or artifacts are found.

Finally, the survey allowed us to identify six new ICT processes to be used to verify the maturity of the ICT Governance processes. These processes and their respective artifacts will be added to our ICT Governance Kit [7]. The implementation of the new processes will allow better monitoring of CADE’s ICT resources. In addition, the standardization and implementation of ICT processes will contribute to CADE’s digital transformation. Thus, the main contribution of this work was to identify in the literature the existing works in relation to the ICT processes and to propose improvements in the processes of an APF agency, in order to improve the use of its ICT resources.

As future work, we intend to apply ICT processes in other agencies of the Federal Public Administration and in the industry. We also aim to use similar questionnaires in order to assess the perception of ICT processes maturity and, eventually, to identify new ICT processes of interest. The practical application of ICT processes in several agencies will allow us to make improvements in the proposed processes and artifacts, analyzing which processes can be excluded or changed.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to performing the reported use case, Writing the Original Draft and Writing Review and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Publication fees were honored by the cooperation project between the Administrative Council for Economic Defense and the University of Brasilia (grant CADE 08700.000047/2019-14).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the support of the Brazilian research, development and innovation agencies CAPES (grants 23038.007604/2014-69 FORTE and 88887.144009/2017-00 PROBRAL), CNPq (grants 312180/2019-5 PQ-2, BRICS2017-591 LargEWiN, and 465741/2014-2 INCT in Cybersecurity) and FAP-DF (grants 0193.001366/2016 UIoT and 0193.001365/2016 SSDDC), as well as the cooperation projects with the Ministry of the Economy (grants DIPLA 005/2016 and ENAP 083/2016), the Institutional Security Office of the Presidency of the Republic (grant ABIN 002/2017), the Administrative Council for Economic Defense (grant CADE 08700.000047/2019-14), and the General Attorney of the Union (grant AGU 697.935/2019).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Asongu, S.A.; Nwachukwu, J.C. The role of openness in the effect of ICT on governance. IT Dev. 2019, 25, 503–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clara, A.M.C.; Canedo, E.D.; de Sousa Júnior, R.T. A synthesis of common guidelines for regulatory compliance verification in the context of ICT governance audits. Inf. Polity 2018, 23, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.J.N.; Ribeiro, Q.A.D.S.; Soares, M.S.; do Nascimento, R.P.C. ICT Governance: A View of Adoption of Best Practices in Enterprises of Sergipe State. In Proceedings of the XV Brazilian Symposium on Information Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA; Sergipe, Brazil, 2019; pp. 58:1–58:8. [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrook, S.; Singer, J.; Storey, M.A.; Damian, D. Selecting empirical methods for software engineering research. In Guide to Advanced Empirical Software Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heiderberg, Germany; London, UK, 2008; pp. 285–311. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Governança Corporativa. Código das Melhores Práticas de Governança Corporativa; IBGC: São Paulo, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorini, F.A.; Junior, N.A.; Alonso, V.L.C. Governança Corporativa: Conceitos e Aplicações. In Proceedings of the XIII Simpósio de Excelência em Gestão e Tecnologia (SEGet), Rezende, Brazil, 30–31 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Canedo, E.D.; da Costa, R.P.; de Sousa Junior, R.T.; Nze, G.D.A. Best Practices Kits for the ICT Governance Process within the Secretariat of State-Owned Companies of Brazil and Regarding these Public Companies. Information 2018, 9, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuzzolo, O. Governança e Estratégia de Tecnologia da informação; Senac: São Paulo, Brazil, 2019; p. 182. [Google Scholar]

- De Haes, S.; Grembergen, W.V. Enterprise Governance of Information Technology Achieving Alignment and Value, Featuring COBIT 5; Springer: Berlin/Heiderberg, Germany, 2015; p. 178. [Google Scholar]

- Weill, P.; Ross, J. IT Governance: How Top Performers Manage IT Decision Rights for Superior Results; Harvard Business School Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Feltus, C. Introducing ISO/IEC 38500: Corporate Governance in ICT; ITSMF Jaarcongres 2008: Luxembourg, Germany, 2012; pp. 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Audit, I.S.; Association, C. COBIT 5: Enabling Processes; ISACA: Schaumburg, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, P. Digital Transformation of the Italian Public Administration: A Case Study. CAIS 2020, 46, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanea-Ivanovici, M.; Pana, M. From Culture to Smart Culture. How Digital Transformations Enhance Citizens’ Well-Being Through Better Cultural Accessibility and Inclusion. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 37988–38000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]