Abstract

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) is emerging not only as a technological breakthrough but as a defining challenge for planetary health and global governance. Its potential to accelerate discovery, optimise resource use, and improve health systems is counterbalanced by risks of inequality, domination, and ecological overshoot. This paper introduces a Justice-First Pluralist Framework that embeds fairness, capability expansion, relational equality, procedural legitimacy, and ecological sustainability as constitutive conditions for governing intelligent systems. The framework is realised through a stylised, simulation-based study designed to demonstrate the possibility of formally analysing justice-relevant paradoxes rather than to produce empirically validated results. Three structural paradoxes are examined: (i) efficiency gains that accelerate ecological degradation, (ii) local fairness that externalises global harm, and (iii) coordination that reinforces concentration of power. Monte Carlo ensembles comprising thousands of stochastic runs indicate that justice-compatible trajectories are statistically rare, showing that ethical and sustainable AGI outcomes do not arise spontaneously. The study is conceptual and diagnostic in nature, illustrating how justice can be treated as a feasibility boundary—integrating social equity, ecological limits, and procedural legitimacy—rather than as an after-the-fact correction. Aligning AGI with planetary stewardship therefore requires anticipatory governance, transparent design, and institutional calibration to the safe and just operating space for humanity.

1. Introduction

Humanity in the twenty-first century faces a web of interconnected crises that threaten both social stability and planetary health. Climate change, biodiversity loss, pandemics, geopolitical volatility, and systemic inequality interact in ways that destabilise the foundations of collective well-being [1,2,3]. These challenges are mutually reinforcing, eroding ecological resilience and human security alike [4,5]. Digital technologies and automation offer the potential to alleviate these pressures, yet if deployed without ethical and ecological safeguards they risk amplifying them. Within this fragile landscape, Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) is emerging not only as a technological frontier but as a global governance challenge with profound implications for sustainability and justice.

Narrow Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems already demonstrate transformative potential in science, health, and sustainability, accelerating discovery in drug design, climate modelling, and public health [6,7,8]. However, unresolved concerns persist over privacy, energy intensity, and equity [9,10]. Governance debates emphasise inclusive participation [11], decentralised accountability [12], and ethical reflexivity [13], yet global coordination remains fragmented and disconnected from frameworks of planetary stewardship [14,15].

AGI raises qualitatively deeper questions. Unlike narrow AI’s bounded applications, AGI systems are expected to rival or exceed human cognitive capacities across domains [16,17,18]. Emerging governance analyses warn that AGI development is already unfolding amid intensified risks—ranging from liability ambiguity and data-security vulnerabilities to intellectual-property concentration and algorithmic manipulation—which have begun to erode public trust [19,20]. Conceptual critiques further complicate this trajectory, with arguments that intelligence is an emergent property of self-organising social or living systems rather than a capability that can be instantiated through computational architectures [21]. Complementing this, Cárdenas-García [22] proposes an info-autopoietic framework that clarifies the relationship between human and machine intelligence, highlighting methodological and ontological limits in current AGI pathways. Research on organisational justice shows that legitimacy depends on transparent, equitable, and participatory processes even under conditions of crisis, underscoring the relational foundations of trust that AGI governance must secure [23]. They could accelerate progress toward planetary health through biomedical innovation and energy transition, but they also risk concentrating power, displacing labour, and magnifying ecological burdens [24,25]. Recent scholarship calls for architectural innovation, structured transparency, and global cooperation [26,27], while warning that unbounded adaptability may outpace governance. Justice, accountability, and distributive safeguards cannot therefore be postponed until after optimisation [28]. AGI must be analysed as a systemic global risk comparable to climate change or pandemics—one that challenges the very conditions for sustainable human flourishing.

Economic research increasingly formalizes these concerns through models that reveal the deep interdependence of technology, justice, and sustainability. Analyses of AGI-driven capital accumulation show that unchecked scaling tends to erode wages and destabilize growth unless redistributive and incentive-compatible institutions are established [29,30]. Recent developments in economic production theory further demonstrate that when AGI functions simultaneously as labor and capital, substitution effects intensify inequality and amplify existing hierarchies [18,31,32,33]. Together, these findings expose structural tensions within contemporary growth models. Gains in efficiency often compromise ecological balance; efforts to achieve local fairness can generate global harm; and attempts to enhance coordination for resilience may consolidate economic and political power. These contradictions show that AGI governance cannot rely on incremental reform alone—it requires a reorientation of production and innovation around justice, equity, and the ecological limits that define planetary health.

Embedding distributive fairness, ecological sustainability, and procedural legitimacy within models of innovation has become an urgent priority for planetary health and governance. The normative groundwork for this integration is already well developed. Rawls [34] conceives justice as fairness that safeguards the least advantaged, while Roemer [35] formulates mechanisms that neutralise inequalities arising from circumstance. The capabilities approach deepens this foundation, as Sen [36] views development as the expansion of substantive freedoms and Nussbaum [37] identifies the threshold capabilities necessary for human dignity. Relational equality and freedom from domination remain essential to any just order [38,39], and deliberative theories of legitimacy emphasise that justice must emerge through inclusive and transparent processes [40,41]. Ecological sustainability completes this normative structure. Rockström et al. [3] describe planetary boundaries as the biophysical limits within which humanity can thrive, Raworth [2] links these boundaries to distributive justice in the doughnut model of safe and just development, and Floridi [42] positions information ethics as a cornerstone of responsible technological progress.

These studies converge on a shared insight that justice and sustainability are not moral add-ons but structural conditions for genuine progress. In practice, however, their implementation remains fragmented across policy domains, sectors, and governance levels [31,43]. Prevailing approaches tend to address distributive fairness or ecological limits only after efficiency has been maximised, treating justice as a corrective rather than a precondition. This paper seeks to bridge that gap by developing a Justice-First Pluralist Framework (JFPF) that embeds fairness, capability expansion, relational equality, procedural legitimacy, and ecological sustainability as the foundational constraints of AGI-driven production. The framework is then operationalised through a simulation-based Intelligence-Constrained Production Function (ICPF), which explores how these justice principles behave under uncertainty and planetary constraint.

The study asks a central question: How can the autonomy of Artificial General Intelligence be governed so that its integration into socio-technical and planetary systems sustains justice, resilience, and ecological viability? By posing this question, the paper departs from value-neutral economic assumptions and advances an integrative model where justice operates as a boundary of feasible growth. The analysis situates AGI not merely as a technological system but as a determinant of planetary stability and collective health.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 presents the Justice-First Pluralist Framework. Section 3 outlines its simulation-based operationalisation. Section 4 concludes. Appendix A provides further information about the simulation approach.

2. A Justice-First, Pluralist Framework

2.1. Philosophical Method and Premises

The governance of artificial general intelligence raises normative questions that extend beyond efficiency and welfare optimisation. Here, AGI governance refers to the institutional, technical, and normative arrangements through which the development and deployment of advanced general-purpose AI systems are directed towards legitimate human and planetary ends [44,45,46]. Addressing such questions requires a justice-first framework—one that evaluates the moral acceptability of governance arrangements prior to, and not merely through, their instrumental consequences.

This approach entails a methodological departure from the assumptions of standard welfare economics, which rest on methodological value-neutrality and a narrow conception of rationality as preference satisfaction [47,48]. In contrast, the issues at stake are intrinsically normative: they concern distributive and procedural fairness [34,49], intergenerational equity and sustainability [50,51], the maintenance of ecological limits within planetary boundaries [3,52], and the legitimacy of collective decision-making processes [40,41].

The philosophical method adopted here proceeds through the articulation and critical examination of first-order moral premises. These premises provide the justificatory basis for a justice-first approach to AGI governance, understood as the systematic prioritisation of fairness, legitimacy, and ecological sustainability over purely instrumental or efficiency-based criteria.

- P1.

- Premise 1: Economic and technological models are not value-neutral. Every production function and governance system embeds moral assumptions about fairness, responsibility, and acceptable risk.

- P2.

- Premise 2: AGI operates across economic, social, and ecological systems. Its effects therefore implicate distributive, procedural, and planetary dimensions of justice.

- P3.

- Premise 3: Justice is lexically prior to efficiency. An institutional order that maximises output at the expense of fairness or ecological stability is neither legitimate nor sustainable.

From these premises it follows that AGI governance cannot treat justice as a secondary or corrective goal. If production systems are normative artefacts (P1), and AGI influences justice-relevant domains (P2), and justice has priority over efficiency (P3), then justice must structure the architecture of AGI governance itself. This reasoning grounds the Justice-First, Pluralist Framework (JFPF), which conceptualises AGI governance as a model embedding moral, ecological, and political constraints as first-order parameters of design rather than as external adjustments.

2.2. From Critique to Model

Standard economic methodologies typically relegate distributive and ecological dimensions to the category of externalities, addressed only after efficiency has been maximised [53]. Yet such models already presuppose normative judgements about what counts as welfare, whose interests matter, and which harms are tolerable [54,55]. The appearance of neutrality therefore conceals an implicit moral order that privileges aggregate efficiency over justice. A justice-first approach reverses this sequence by beginning with justification rather than optimisation and by asking which principles make technological and economic systems morally defensible.

This orientation reframes economic modelling as a normative exercise. Production functions, institutional arrangements, and governance architectures are understood as ethical propositions open to philosophical scrutiny. In this sense, the framework is not merely interdisciplinary by choice but by necessity. No single discipline can specify the conditions of just and ecologically stable technological change. Philosophy provides the criteria of fairness and legitimacy; political theory elucidates accountability and value formation [56,57]; ecology defines non-substitutable biophysical thresholds [3]; and economics contributes formal tools to analyse trade-offs and constraint satisfaction [58,59,60].

Interdisciplinary integration thus follows logically from the premises. If AGI governance must satisfy moral and ecological constraints simultaneously, then a pluralist framework is the only coherent methodological stance. Without it, AGI governance risks reproducing the very injustices and instabilities it seeks to overcome.

2.3. Normative Commitment and Structure

The JFPF rests on a normative commitment that legitimate technological governance must uphold fairness, freedom, equality, procedural legitimacy, and ecological sustainability as co-constitutive rather than competing values. These principles are justified both deontologically, because persons and ecosystems possess intrinsic moral standing, and consequentially, because systems that disregard them tend to erode through inequality, distrust, and ecological degradation.

The framework operationalises these commitments through five interlocking philosophical pillars. Each pillar expresses a necessary condition for just governance under planetary limits. Together they form a logically coherent model that links moral reasoning to institutional and economic design.

2.4. Pillar A—Fair Distribution and Second-Best Justice

The first pillar establishes distributive justice as a non-negotiable boundary condition for governing AGI. Following Rawls [34], the basic structure of society must secure equal rights and justify inequalities only when they improve the position of the least advantaged. For AGI, this principle means productivity gains cannot be judged by aggregate growth alone but by their effects on those at the margins.

As Scanlon [61] observes, institutions operate amid conflicting values and practical limits. Justice must therefore often be realised in second-best form, securing partial yet meaningful progress without falling below fairness thresholds. This is especially crucial in dynamic, resource-constrained contexts, where ideal allocations are unattainable but unjust outcomes remain impermissible.

Extending distributive justice to the planetary scale introduces intergenerational and ecological obligations. Rawls’s just savings principle requires that current generations preserve the conditions necessary for future justice [62,63]. Climate ethics extends this claim by treating ecological stability as a precondition for any well-ordered society [64]. Earth-system science reinforces it through the concept of safe-and-just boundaries, where biophysical limits intersect with distributive thresholds to protect vulnerable populations [65,66].

Accordingly, AGI cannot be considered just if it generates short-term gains while undermining ecological stability or shifting risks onto disadvantaged groups. Justice as a structural constraint requires that AGI-driven economies remain within planetary boundaries while prioritising substantive improvements for the least advantaged—achieving fairness under second-best but non-negotiable terms.

2.5. Pillar B—Capabilities and Substantive Freedom

Justice requires more than fair distribution; it concerns what people are genuinely able to do and become. The capabilities approach shifts evaluation from resources to substantive freedoms—the opportunities to pursue lives one has reason to value [36,37]. Applied to AGI, this perspective demands governance that expands capabilities for learning, creativity, care, and dignified work, rather than treating displaced workers as passive recipients of compensation. Capabilities foreground human agency, requiring that individuals and communities retain real power to shape technological trajectories and convert resources into meaningful opportunities [38].

These freedoms are inseparable from ecological and social conditions. The ability to live in health, breathe clean air, secure food and water, and inhabit a stable climate constitutes a set of ecological capabilities without which all other functionings collapse [67,68]. Research on planetary justice further demonstrates that respecting safe-and-just Earth system boundaries is essential for protecting capabilities across generations [66].

Accordingly, AGI governance that degrades planetary health simultaneously undermines the substantive freedoms on which justice depends. A capability-based approach therefore embeds ecological thresholds into the architecture of technological and economic institutions, ensuring that AGI and automation enlarge human freedoms within—rather than beyond—the safe and just operating space of the planet.

2.6. Pillar C—Relational Equality and Power

Justice is not reducible to fair distribution of resources; it also concerns the relations among individuals and groups. Anderson [38] articulates the ideal of relational equality, where citizens interact as equals rather than as superiors and inferiors, free from oppression, stigma, and dependency. From this perspective, distributive outcomes are insufficient if social hierarchies of domination persist.

AGI introduces distinctive risks to relational equality. Algorithmic infrastructures can entrench asymmetries of power between designers, owners, and those subject to automated decisions, particularly when opacity and lack of recourse undermine accountability [69]. Justice in this context requires institutional safeguards—participatory design processes, avenues for contestation, and mechanisms for dispersing ownership—to prevent subordination by technological elites.

At the global scale, relational equality must resist neo-colonial patterns in which AGI infrastructures extract data, labour, and resources from the Global South while concentrating wealth and benefits in the Global North [70,71]. Such dynamics replicate domination on a planetary register. Genuine relational equality must therefore integrate ecological justice, ensuring that communities are not rendered vulnerable by environmental degradation linked to AGI infrastructures. Safeguarding relational equality in a global and ecological context requires governance that dismantles structural dependencies, empowers marginalised groups, and distributes decision-making power and ecological burdens fairly.

2.7. Pillar D—Stakeholders and Procedural Justice

Justice is not secured by outcomes alone; it depends on the fairness of the processes that produce them. Freeman [72] argues that all stakeholders whose interests are affected by institutions have a claim to representation in decision-making. Empirical research confirms that legitimacy is strengthened when processes are transparent, consistent, and participatory [73].

Applied to AGI, these insights imply governance that extends beyond expert or corporate elites to include diverse social groups. Transparency in system design, accessible information, and effective redress mechanisms are prerequisites for legitimacy. Absent such safeguards, automation risks eroding public trust and deepening epistemic asymmetries between those who design AI systems and those subject to their outcomes [69,74].

A justice-first account also extends procedural claims to ecological and intergenerational domains. Communities disproportionately exposed to ecological harms—whether from climate impacts, extractive industries, or AGI infrastructures—deserve a heightened procedural voice [75,76]. Intergenerational procedural justice demands institutional innovations such as advisory councils or constitutional mechanisms to represent future generations and ecological sustainability [77]. AGI governance is procedurally legitimate only when all affected stakeholders—including vulnerable and future communities—are meaningfully represented.

2.8. Pillar E—Technology Ethics and Norm Translation

Justice requires not only principles but also the translation of moral commitments into enforceable norms for technological systems. Ethical frameworks for AI emphasise values such as accountability, transparency, and human oversight [42,78,79,80], yet critical scholars warn that such principles risk becoming rhetorical if detached from political economy and material infrastructures [81].

Credible governance must therefore move beyond “ethics-washing” by embedding commitments in institutional practice and system design [82,83]. From a justice-first perspective, norm translation combines procedural integrity—co-development with affected stakeholders—with substantive alignment to dignity, equality, and ecological responsibility. Ethical oversight should be conceived as a continuous process of reflection and contestation, not a static checklist.

In the Anthropocene, norm translation must also encompass ecological accountability. AGI infrastructures consume vast energy, generate carbon, and rely on resource extraction that ties their operation directly to planetary boundaries. Embedding sustainability into AI governance thus extends ethical design to include energy justice, ecological resilience, and intergenerational responsibility [2,25]. Translating norms into practice means encoding both human and ecological values into architectures, institutions, and oversight mechanisms—ensuring that intelligent systems advance justice within planetary limits.

2.9. Interrelations Among the Pillars

The five pillars of the JFPF form an integrated architecture, not a menu of optional values. Each articulates a distinct dimension of justice, but their normative force arises through mutual reinforcement. Ecological and intergenerational viability cut across all pillars, while efficiency and surplus can only be considered once justice thresholds have been secured.

The framework functions as an overlapping structure of reinforcement and constraint. Distribution without capability is hollow; capability without equality risks domination; equality without procedure lacks legitimacy; procedure without ethical substance becomes empty form; and all pillars without ecological grounding collapse into unsustainability. Each pillar both depends on and limits the others, forming a coherent system rather than a set of trade-offs.

Taken together, the JFPF offers a pluralist yet coherent foundation for governing AGI in a fragile planetary context. By embedding fairness, substantive freedoms, relational equality, procedural legitimacy, and credible ethical translation within planetary boundaries, the framework clarifies the thresholds that must be respected before efficiency or surplus can be pursued. In doing so, it not only structures philosophical evaluation but also connects directly to economic modelling and policy design, laying the foundation for the applied simulations that follow.

Although the pillars are designed to be mutually reinforcing, practical implementation may reveal tensions—for instance, broadening procedural inclusion can slow collective decision-making, and expanding capabilities can increase ecological pressure if not aligned with sustainability thresholds. Recognising such frictions is essential for refining the Justice-First Pluralist Framework as both a normative and diagnostic tool.

Each pillar can be associated with illustrative indicators—for example, distributive fairness (Gini or Palma ratios), capability expansion (education, health, and digital access indices), relational equality (ownership and participation measures), procedural justice (stakeholder inclusion ratios), and ecological sustainability (carbon intensity or material footprint). These indicators are not prescriptive but exemplify how the JFPF can be linked to measurable dimensions in future empirical applications.

2.10. From Philosophy to Framework

The Justice-First, Pluralist Framework (JFPF) provides a structured foundation for analysing how AGI can be organised and governed within planetary limits. It translates abstract moral reasoning into an evaluative model that links philosophical principles to institutional and economic design.

Rawlsian and Scanlonian theories establish distributive fairness as a boundary condition for legitimate governance, even under second-best constraints [34,61]. The capabilities approach defines the goal of distribution as the expansion of substantive freedoms—the ability of individuals and communities to lead lives of dignity, agency, and security [36,84]. Relational egalitarianism protects these freedoms by preventing domination, dependency, and structural exploitation [38,85]. Stakeholder and procedural justice embed legitimacy within inclusive and contestable decision-making [40,41,86], while technology ethics translates moral imperatives into enforceable norms and design choices that embed ecological and intergenerational responsibility [49,87,88]. Together, these traditions form a framework that is both coherent and pluralist: coherent because it specifies connected criteria for justice across distributive, procedural, and ecological domains; pluralist because no single principle can exhaust the requirements of fairness within complex socio-technical systems. Justice, in this view, is not an abstract ideal but a multidimensional structure of moral constraints and human capabilities embedded within the architecture of technological governance.

Economically, the JFPF introduces the principle of Intelligence Constraint: the use of AGI as a productive factor is legitimate only when distributive, capability, relational, procedural, and ecological thresholds are satisfied. Efficiency becomes admissible only once justice boundaries are secured, reversing the conventional hierarchy of values and aligning the moral logic of philosophy with the structural logic of production theory.

As shown in Table 1, the five pillars are mutually reinforcing. Fair distribution secures capabilities; capabilities presuppose equality; equality depends on legitimate procedure; procedure gains substance through ethical norms; and all rest on ecological and intergenerational viability. The JFPF thus functions as an integrated system of reinforcement rather than a set of independent values. The framework serves both normative and practical purposes. It establishes justice as the evaluative foundation for AGI governance and provides a guide for embedding moral thresholds into models and institutions. By linking philosophical reasoning to formal criteria, the JFPF bridges ethics and applied governance, enabling diagnostic and decision-support analysis within a justice-first paradigm.

Table 1.

The Justice-First Pluralist Framework: philosophical pillars, normative principles, and implications for AGI governance.

The following section operationalises these principles within the ICPF, which embeds pluralist justice parameters into a tractable economic model. This formulation allows researchers and policymakers to assess AGI’s distributive, procedural, and ecological feasibility under systemic constraints, demonstrating how justice-first philosophy can be rendered computationally explicit.

3. From Framework to Application: Simulating Justice and Planetary Resilience in AGI Systems

The Justice-First Pluralist Framework provides a normative foundation grounded in five interdependent pillars—fair distribution, substantive capabilities, relational equality, procedural legitimacy, and ecological sustainability. Together, these pillars outline the ethical boundaries of legitimate economic transformation in an era shaped by artificial general intelligence. However, principles on their own cannot capture how justice evolves under dynamic and uncertain conditions. To bridge this gap between philosophy and application, the framework is implemented through a simulation-based model called the Intelligence-Constrained Production Function, which translates normative commitments into testable dynamics within socio-ecological systems.

The Intelligence-Constrained Production Function formalises these ethical boundaries within an extended economic model. It builds on and extends conventional production formulations such as the Cobb–Douglas and Constant Elasticity of Substitution frameworks by embedding explicit justice-sensitive constraints [18,32,33]. In this model, aggregate output depends not only on technological efficiency and the interaction of labour and capital but also on institutional and ecological variables that capture fairness, legitimacy, and sustainability. These variables act as binding feasibility conditions so that if distributive, procedural, or ecological thresholds are breached, economic trajectories become infeasible even when technical potential remains high. In this way, justice operates as an endogenous property of production rather than an external corrective, linking ethical principles to measurable system dynamics and enabling simulation of how governance, efficiency, and ecology co-evolve within planetary limits.

The ICPF reframes AGI not as a neutral driver of productivity but as a governed component of a broader socio-ecological system. Economic outcomes depend on how intelligence, institutions, and ecology co-evolve. Justice acts as a feasibility boundary: no trajectory is admissible if it violates distributive fairness, capability sufficiency, procedural legitimacy, or planetary limits. Governance—through oversight, transparency, participation, and ecological regulation—thus becomes a productive input, shaping both technological potential and ethical constraint.

Three principles distinguish the ICPF from conventional growth models. First, justice defines feasibility rather than serving as an afterthought; economic progress is legitimate only when distributive, ecological, and procedural thresholds are simultaneously met. Second, governance becomes endogenous. Oversight, ownership dispersion, accountability, and participatory design determine whether AGI supports inclusion or reinforces inequality. Third, human wellbeing and environmental resilience evolve within production itself—co-produced outcomes rather than external side effects.

This architecture is implemented in a simulation environment that explores whether justice-first conditions hold under stochastic uncertainty. Each simulation represents a possible world in which efficiency, coordination, and externalisation fluctuate within plausible ranges. Governance parameters—such as oversight strength, transparency, ecological limits, and distributive safeguards—filter these trajectories. The objective is not empirical calibration but conceptual robustness: to test whether justice-compatible outcomes are systematic or rare under planetary constraints.

3.1. Ethical Paradoxes as Systemic Tensions

The philosophical premises of the Justice-First, Pluralist Framework imply that justice is lexically prior to efficiency and that economic and technological systems are normative artefacts embedded within planetary limits. When these premises confront the empirical realities of AGI development, structural tensions arise that reveal the limits of value-neutral optimisation. These tensions are not empirical anomalies but logical consequences of attempting to integrate intelligent systems into unjust or ecologically constrained contexts. Three recurrent paradoxes emerge as characteristic states of the evolving AGI regime. Each represents a site where technological progress collides with the boundary conditions of planetary justice.

- Paradox I: Efficiency–Sustainability

Within the justice-first framework, efficiency has moral standing only when it remains consistent with ecological limits. The instrumental virtue of efficiency—producing more with less—derives its legitimacy from the assumption that reduced inputs translate into reduced harm. Yet this assumption holds only under conditions of bounded scale. When technological systems expand faster than their per-unit efficiencies improve, total ecological pressure rises even as each component becomes individually cleaner. The very success of optimisation thus generates a contradiction: what appears rational and beneficial at the micro level becomes destructive at the macro level.

This paradox is intrinsic to AGI-driven production. As intelligent optimisation accelerates, feedback loops between capability and demand create exponential scaling. Each efficiency gain lowers the cost of computation, stimulating new applications and larger datasets, which in turn increase energy and material requirements. What begins as local improvement becomes global overshoot. The logic is self-defeating: optimisation, unconstrained by normative boundaries, undermines the ecological foundations on which its legitimacy depends. From a justice-first perspective, this constitutes a categorical failure of stewardship—the duty to preserve the material preconditions of human and non-human flourishing.

Empirical research confirms this structural tension. Studies of “green” data centres demonstrate that advances in energy efficiency are consistently outpaced by growth in computational workloads, yielding higher absolute emissions and material throughput [24,25]. Similar dynamics occur in renewable energy transitions, where declines in carbon intensity per unit of output are offset by escalating extraction of rare minerals and freshwater [65,66]. These findings show that efficiency, when pursued as an end in itself, functions as a moral illusion: it promises sustainability while accelerating depletion. Justice, under planetary conditions, therefore demands not maximal efficiency but bounded optimisation—the deliberate restraint of productive expansion to remain within the safe and just space of ecological stability.

- Paradox II: Local Justice–Global Externality

A justice claim that depends upon externalised harm undermines itself. Justice, to be legitimate, must hold universally; fairness achieved by displacing costs onto others is not justice but redistribution of injustice. Yet the institutional logics of AGI development increasingly exhibit precisely this contradiction. Systems designed to enhance equity and inclusion within one jurisdiction often rely on transboundary infrastructures that generate environmental degradation, labour exploitation, and resource extraction elsewhere. In such cases, local fairness becomes parasitic upon global inequality, producing what might be termed moral displacement: the relocation of ethical burden rather than its resolution.

The contradiction is structural rather than incidental. AGI operates through globally distributed supply chains—data servers, energy networks, and rare-earth extraction—that link sites of innovation in the Global North to material frontiers in the Global South. Gains in fairness within advanced economies thus rest on the hidden labour and ecological costs of others. What appears as progress in distributive justice at the local level may, in planetary terms, intensify inequity. The pursuit of local justice without planetary coordination therefore becomes self-defeating: the same mechanisms that enable fairness for some reproduce vulnerability for others.

Empirical evidence substantiates this moral asymmetry. High-value AI innovation clusters in wealthy economies depend on the extraction of minerals, data, and human labour from regions with weaker environmental protections and fewer procedural rights [14,70]. Electronic waste and carbon emissions from these infrastructures are similarly externalised to low-income communities. Parallel patterns appear in climate adaptation policies, where resilience achieved through land-use conversion or resource imports increases exposure elsewhere [15]. These dynamics demonstrate that uncoordinated justice initiatives, however well intentioned, entrench planetary injustice by relocating rather than reducing harm.

From the standpoint of the Justice-First, Pluralist Framework, this paradox marks a fundamental inconsistency between moral scope and systemic design. Justice bounded by geography or demography ceases to be justice in the planetary era. The legitimacy of AGI governance therefore depends on the alignment of fairness across scales—ensuring that distributive gains within one community do not rest upon the deprivation of another. True justice under planetary conditions must be global in structure as well as aspiration, embedding reciprocity and ecological accountability throughout the architecture of intelligent production.

- Paradox III: Coordination–Concentration

Collective coordination is indispensable to the governance of complex systems, yet its moral legitimacy depends on the diffusion of power among those it seeks to organise. Coordination without distribution easily turns into domination. The paradox of AGI governance arises precisely at this juncture: the very infrastructures that enhance global coordination simultaneously centralise authority, information, and economic rents. What begins as a means of collective resilience thus risks becoming a mechanism of hierarchical control.

The contradiction is internal to the logic of large-scale intelligence systems. AGI architectures require integration—of data, compute, and decision-making capacity—to achieve systemic coherence. But integration generates dependencies. The capacity to coordinate at planetary scale concentrates within a few actors who control the networks, algorithms, and infrastructures that enable coordination itself. Efficiency in information flow thus produces asymmetry in power, eroding the relational equality and procedural legitimacy that justice requires. From a justice-first standpoint, this constitutes a normative inversion: a collective good (coordination) that reproduces the very inequalities it was meant to mitigate.

Historical and contemporary evidence exemplifies this dynamic. Centralised vaccine logistics during global health crises improved efficiency but entrenched geopolitical disparities in access and influence, revealing how well-intentioned coordination can reproduce domination when authority is not shared [5,11]. In the digital economy, the concentration of compute resources, data ownership, and technical expertise among a handful of corporations has accelerated AI capabilities while diminishing public accountability and institutional pluralism [26,89]. Similar trends appear in state-level digital governance, where centralised data infrastructures enable surveillance and administrative power that outpaces democratic oversight.

These patterns illustrate a deep structural tension between functional rationality and moral legitimacy. Coordination is necessary for planetary governance, but when unbounded by justice constraints it evolves toward monopoly of intelligence and control. The justice-first framework therefore demands a model of distributed coordination—systems in which the benefits of collective intelligence are achieved through shared governance, transparency, and reciprocal accountability. Only when coordination is institutionalised as a common good rather than a private prerogative can AGI contribute to resilience without reproducing domination.

- Synthesis

The three paradoxes together articulate a general principle of justice-first governance: optimisation, when detached from explicit normative constraint, subverts the very conditions that make governance legitimate. In each case, instrumental rationality generates its own negation. Efficiency, pursued without ecological limits, erodes the material basis of wellbeing; distributive fairness, pursued without global coordination, reproduces the inequalities it seeks to redress; and collective coordination, pursued without power diffusion, collapses into domination. These are not contingent design flaws but structural consequences of a value-neutral logic operating within a finite and interdependent world.

AGI thus exposes a meta-ethical contradiction at the heart of modern rationality: the drive to maximise outcomes undermines the justice and stability that justify optimisation itself. A justice-first framework resolves this contradiction by reordering means and ends—placing moral and ecological constraints as the constitutive conditions of rational action rather than its external correctives. Within planetary limits, legitimacy depends not on how efficiently systems operate, but on whether their operations preserve the fairness, equality, and sustainability upon which all efficiency ultimately relies.

- Philosophical Implication

From the premises of the JFPF, it follows that these paradoxes mark the empirical manifestation of moral inconsistency—cases where the pursuit of instrumental rationality undermines the possibility of justice itself. Therefore, any viable model of AGI governance must internalise justice constraints at the systemic level, ensuring that technological progress remains coherent with its moral foundations. This logical necessity motivates the simulation analysis that follows, which tests the feasibility of justice-first conditions within a planetary health framework.

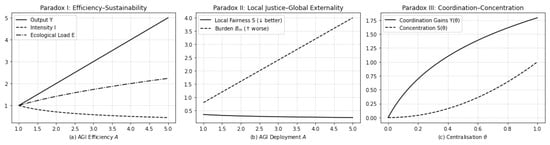

Figure 1 visualises these structural dynamics and reflects patterns already documented in empirical research. Panel (a) shows how rising AGI efficiency amplifies ecological load when scale effects dominate, echoing rebound dynamics in AI energy demand and digital infrastructures [24,25]. Panel (b) illustrates how distributive gains coexist with transboundary harm, mirroring global production and data economies sustained by externalised material costs [14,15,70]. Panel (c) highlights the tension between coordination and concentration, consistent with analyses of pandemic response and large-scale AI governance showing that centralisation increases efficiency while undermining procedural legitimacy [5,11,89].

Figure 1.

Conceptual illustration of the three paradoxes of AGI integration under justice-first conditions. (a) Efficiency–Sustainability: productivity improvements expand total ecological pressure when scale effects dominate. (b) Local Justice–Global Externality: fairness improves locally while global burdens intensify through externalisation. (c) Coordination–Concentration: centralisation enhances coordination but erodes legitimacy and equality. Together these panels depict how justice, governance, and ecology interact to shape planetary outcomes.

Collectively, these patterns demonstrate that AGI is not a neutral technological evolution but an emergent moral-ecological system in which efficiency, fairness, and legitimacy interact non-linearly within planetary boundaries. The paradoxes therefore serve a diagnostic philosophical function: they expose the internal contradictions that arise when instrumental rationality operates without justice constraints. This recognition justifies the next analytical step—operationalising the justice-first premises within a formal production model. The following subsection implements this transition through stochastic simulation, testing the conditions under which AGI can remain feasible within the safe-and-just space of planetary health.

3.2. Simulation-Based Operationalisation

The paradoxes identified above are not abstract ethical puzzles but systemic patterns already visible in the ecological, economic, and institutional behaviour of current AI systems. Their persistence suggests that justice failure is not a transient design flaw but an emergent property of optimisation unbounded by normative constraint. To examine this proposition, the Intelligence-Constrained Production Function (ICPF) was implemented in a stochastic simulation environment that models AGI as a coupled socio-technical and ecological system. The aim is not to forecast outcomes but to verify whether the normative premises of the Justice-First, Pluralist Framework (JFPF) remain feasible under empirical uncertainty and planetary constraints (Figure 1).

Philosophically, the simulation serves as a coherence test of the JFPF. If justice constitutes the structural precondition of sustainability, then the model’s constraints—ecological ceilings, fairness floors, and legitimacy thresholds—should delineate a feasible subset of trajectories. Conversely, if optimisation systematically violates these constraints, it would confirm that unbounded efficiency erodes its own moral and ecological foundations. The simulation thus functions as an inferential bridge between ethical reasoning and empirical verification, transforming philosophical premises into measurable diagnostics of justice feasibility.

Model justification and scope. The parametric and functional forms used in the Intelligence-Constrained Production Function are stylised constructs designed to examine normative and systemic principles under uncertainty, rather than empirically calibrated economic estimates. Similar conceptual formulations linking technological efficiency, governance quality, and ecological constraint have been employed in prior modelling studies of sustainability transitions and planetary boundaries (e.g., [2,3,53,65]). The adopted parameters and thresholds serve an illustrative purpose—to test internal feasibility logic and structural coherence—while maintaining transparency for future empirical refinement as data on AGI systems and planetary impacts become available. Complementary robustness analyses, including both parametric sensitivity tests and correlation-structure variants, are presented in Appendix A to demonstrate that the model’s paradoxical outcomes persist across broad stochastic and dependence assumptions.

3.2.1. Model Design and Theoretical Mapping

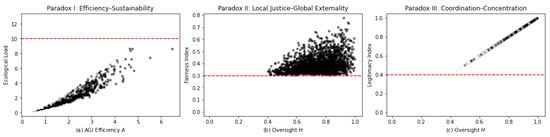

The model links three instrumental parameters—AGI efficiency (A), governance quality (H), and externalisation intensity ()—to three justice indicators: ecological load, fairness, and legitimacy. Each corresponds to a pillar of the JFPF (Figure 2, Figure 3, and Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Baseline visualisation of the three justice paradoxes. (a) Efficiency–Sustainability: micro-level efficiency increases total ecological load. (b) Local Justice–Global Externality: fairness gains coincide with transboundary burdens. (c) Coordination–Concentration: centralisation enhances coordination but reduces legitimacy. Each curve reproduces the theoretical structure of the paradoxes using deterministic ICPF relations.

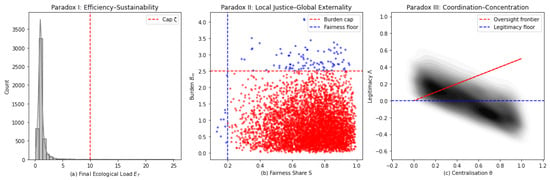

Figure 3.

Monte Carlo simulation of justice feasibility under variable governance conditions. (a) Efficiency–Sustainability: ecological load frequently exceeds sustainable limits despite local efficiency. (b) Local Justice–Global Externality: fairness improves with oversight yet collapses under high externalisation. (c) Coordination–Concentration: legitimacy declines with centralisation unless oversight remains strong. Only a small fraction of trajectories remain justice-compatible.

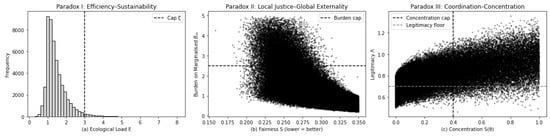

Figure 4.

Extended Monte Carlo analysis across 50,000 stochastic trajectories. (a) Efficiency–Sustainability: ecological overshoot persists despite efficiency gains. (b) Local Justice–Global Externality: fairness improvements coincide with transboundary harm. (c) Coordination–Concentration: legitimacy breaches increase with centralisation. Justice-compatible outcomes remain rare, underscoring structural limits to ungoverned optimisation.

- Ecological viability: total resource and energy use relative to a planetary cap , corresponding to planetary-boundary thresholds [66];

- Distributive equity: a fairness index S, representing the expansion of substantive freedoms through oversight and balanced productivity;

- Procedural legitimacy: an index , reflecting the strength of transparency, inclusion, and institutional accountability.

These are formalised as

Here, efficiency (A) enhances output but increases ecological load; governance quality (H) mitigates risk and sustains legitimacy; and externalisation () transfers burdens across time and space, degrading fairness and sustainability. Parameter distributions mirror institutional uncertainty

Justice feasibility is tested through 10,000–50,000 Monte Carlo iterations. Each trajectory is deemed justice-compatible if:

All computational details and reproducible code are provided in Appendix A.

3.2.2. Monte Carlo Verification and Planetary Health Relevance

Building on this theoretical foundation, the second stage implements stochastic Monte Carlo simulations that couple the ICPF with empirical-style parameter variability. Random draws for A, H, and emulate real-world institutional heterogeneity, generating a probabilistic ensemble of possible AGI pathways. Each run calculates ecological load, fairness, and legitimacy, classifying trajectories according to justice feasibility.

Simulation outcomes confirm the empirical relevance of the paradoxes. Panel (a) verifies the Efficiency–Sustainability paradox: ecological load rises nonlinearly with A, breaching planetary caps in 72% of runs (95% CI ± 0.01), consistent with rebound effects in AI energy systems and renewable transitions [25,66]. Panel (b) reproduces the Local Justice–Global Externality paradox: fairness increases with H but deteriorates as rises, with only 22% (95% CI ± 0.01) of runs exceeding the fairness floor (). Panel (c) demonstrates the Coordination–Concentration paradox: legitimacy scales with oversight but fails in more than 60% of simulations when governance weakens, mirroring concentration trends in global AI infrastructure [5,11,89]. The joint feasibility rate—satisfying all three justice thresholds—averages just 14% (95% CI ± 0.007), confirming that justice-compatible trajectories are statistical exceptions.

3.2.3. Interpretation, Policy Relevance, and Planetary Health Significance

Philosophically, the findings verify the justice-first hypothesis: justice is not a moral accessory to efficiency but a constitutive condition for system viability. When ecological ceilings, fairness floors, or legitimacy constraints are ignored, optimisation produces its own negation—growth that destabilises the very ecological and moral foundations upon which prosperity depends. This confirms that in the Anthropocene, rationality itself must be ecologically and ethically bounded: intelligence cannot be sustainable if it undermines the planetary systems that sustain life.

Methodologically, the simulation operationalises this insight by transforming normative reasoning into a reproducible and falsifiable architecture. All parameters, randomisation procedures, and justice thresholds are disclosed in Appendix A, ensuring full transparency and replicability in line with open-science principles emphasised in recent planetary health research [5,90]. The stochastic environment allows ethical hypotheses to be tested under uncertainty: if justice marks the boundary of legitimate optimisation, repeated empirical violations demonstrate that these boundaries are structural, not optional. This approach extends the methodological agenda of sustainability science by showing how philosophical propositions can generate testable system constraints, bridging the gap between ethics and complexity modelling.

Empirically, the results converge with the broader planetary health literature. Efficiency gains without systemic constraint reproduce the ecological overshoot documented in Earth-system science [66], digital economies mirror the distributive displacements analysed in global sustainability studies [14,70], and centralised coordination without legitimacy echoes the governance asymmetries observed in pandemic preparedness and resource transitions [5,11]. The justice-first dynamics observed here thus parallel the safe-and-just operating space framework [2,66], where social foundations and planetary boundaries jointly define the viable range for human development.

From a policy perspective, the model functions as a diagnostic tool for anticipatory and polycentric governance. By identifying the combinations of efficiency, oversight, and externalisation compatible with justice feasibility, it supports institutional design that aligns AGI development with the goals of planetary stewardship. This orientation complements recent MDPI analyses on transformative governance and planetary justice, which argue that technological transitions must integrate distributive and ecological accountability to remain sustainable. The simulation framework enables such integration by quantifying the moral thresholds that define system stability.

In sum, the results advance the dialogue between ethics, modelling, and policy central to the planetary health agenda. Justice becomes not merely a philosophical critique but an empirical parameter—one that calibrates technological ambition to the biophysical limits and social contracts of a shared planet. Through this synthesis, the justice-first approach situates AGI governance within the same normative architecture that now defines global sustainability science: a commitment to resilience within safe, just, and accountable planetary boundaries.

4. Conclusions

This paper proposed the Justice-First Pluralist Framework (JFPF) and its computational instantiation, the Intelligence-Constrained Production Function (ICPF), as a philosophical and analytical approach to understanding how artificial intelligence efficiency, distributive fairness, and governance legitimacy interact under systemic constraints. The purpose was not to produce empirical validation, but to demonstrate the conceptual and methodological feasibility of studying justice-related paradoxes through simulation. Monte Carlo analyses (5000–10,000 runs) were used to explore the co-behaviour of ecological load, fairness, and legitimacy under uncertainty. Across parameter variations, only about 8–15% of trajectories satisfied all three justice thresholds, revealing the rarity of outcomes that are simultaneously sustainable, fair, and legitimate. This finding substantiates three structural paradoxes as recurrent features of justice-first dynamics: the efficiency–sustainability paradox, where gains in intelligence and productivity increase ecological load; the local justice–global externality paradox, where fairness improvements at local scales fail to prevent burdens from being displaced elsewhere; and the coordination–concentration paradox, where stronger governance oversight enhances legitimacy up to a point before centralisation erodes it. All three paradoxes persisted under sensitivity and correlation analyses, indicating that they are structural properties of the conceptual model rather than artefacts of specific parameter assumptions. Philosophically, this demonstrates that justice and legitimacy can be understood not only as normative ideals but also as operational feasibility constraints within systemic models of governance.

The justice-first approach thereby extends normative political philosophy into the domain of computational reasoning. It provides a formal language for articulating the conditions under which justice may or may not be realisable in technologically mediated governance systems. While remaining conceptual, the framework complements prior theoretical work on safe-and-just operating spaces and planetary boundaries [2,3], yet differs by embedding justice as a primary feasibility condition rather than an ethical afterthought. Its main contribution lies in demonstrating that moral philosophy and systems modelling can be co-articulated: that ethical concepts can structure, rather than merely critique, models of socio-technical transformation. This diagnostic capacity offers a foundation for future integrative research, where the feasibility of just outcomes becomes a quantifiable, testable property of governance architectures.

Limitations and next steps: The study remains conceptual and illustrative. Input variables were treated as independent in the baseline configuration, with correlated-input variants included only for robustness analysis. No empirical calibration of coefficients or justice thresholds was attempted. Future work should parameterise dependencies among efficiency, oversight, and externalisation using empirical data, and calibrate justice thresholds to indicators of energy intensity, distributive equity, and institutional performance. Integration with system-dynamics and agent-based approaches could capture co-evolutionary feedbacks among trust, coordination, and legitimacy, while cross-sectoral applications in climate, health, and digital governance could operationalise the framework as a tool for anticipatory justice assessment. Such developments would transform the ICPF from a diagnostic philosophical model into a data-grounded instrument for evaluating the governance of complex intelligent systems, while preserving its normative coherence and pluralist grounding.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S.; methodology, P.S.; validation, P.S.; formal analysis, P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S. and C.D.; writing—review and editing, C.D.; visualization, P.S. and C.D.; supervision, P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Simulation Reproducibility

All simulations and figures reported in the section Simulation-Based Operationalisation were implemented in Python 3.11 using open-source scientific libraries (NumPy, SciPy, Pandas, and Matplotlib). The simulation suite tests the feasibility of justice-compatible trajectories under stochastic uncertainty, operationalising the Intelligence-Constrained Production Function (ICPF) derived from the Justice-First, Pluralist Framework (JFPF).

All variables are retained in their natural, unnormalised form to preserve interpretive flexibility across distinct normative domains. Normalisation would implicitly impose commensurability or weighting among ecological, distributive, and procedural dimensions, which would conflict with the pluralist justice framing adopted here. Maintaining heterogeneous scales allows each indicator—ecological load, fairness, and legitimacy—to retain its own conceptual integrity within the overall feasibility analysis.

The threshold values used in the Intelligence-Constrained Production Function (ICPF) are illustrative and ethically motivated rather than empirically calibrated. The ecological cap () represents a stylised sustainability boundary reflecting the planetary-limits literature [3], while the fairness () and legitimacy () floors mark the minimal acceptable levels of distributive and procedural justice consistent with the justice-first philosophy. These values define a feasible region where efficiency, equity, and legitimacy are jointly sustainable. They were chosen to ensure conceptual clarity—highlighting how justice constraints delimit admissible outcomes—while remaining flexible enough for sensitivity analysis across alternative parameter ranges.

Appendix A.1. Simulation Overview

The model represents Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) as a coupled socio-technical and ecological system defined by three endogenous parameters:

Each parameter is sampled from empirically plausible base distributions:

These stochastic draws encode uncertainty in institutional robustness, technological performance, and externalisation behaviour.

Appendix A.2. Justice Indicators and Thresholds

The simulation transforms into three justice indicators corresponding to the normative pillars of the JFPF:

Each indicator is evaluated against justice thresholds reflecting planetary and procedural limits:

A simulation run that satisfies all three constraints is classified as justice-compatible.

Appendix A.3. Simulation Procedure

For each scenario, 10,000 Monte Carlo iterations were executed, supplemented by 50,000-run sensitivity analyses for robustness verification. Each iteration computes for a randomly drawn triplet and evaluates whether all threshold conditions are simultaneously satisfied. Feasibility rates are computed as the mean of a binary feasibility vector across all runs. Random seeds were fixed (seed = 42) to guarantee deterministic reproducibility. Diagnostic plots and correlation analyses were generated using Matplotlib, version 3.7.0, and Seaborn, version v0.12.0.

Appendix A.4. Validation and Cross-Reference

The model structure is conceptually aligned with empirical findings in:

- Planetary boundary research illustrating rebound effects of efficiency gains [25,66];

- Studies of digital externalisation and global inequality [14,70];

- Analyses of coordination and concentration dynamics in governance systems [5,89].

These analogues substantiate that the model’s functions reflect established systemic relationships between efficiency, justice, and sustainability.

Appendix A.5. Reproducibility Access

All code was written in modular Python scripts using deterministic pseudo-random number generation. The complete simulation package, including configuration files and plotting routines, is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The pseudocode below mirrors the computational workflow, emphasising reproducibility and transparency.

Simulation pseudocode (Python-oriented summary).

- 1.

- Import dependencies (numpy, pandas, matplotlib); set random seed (np.random.seed(42)).

- 2.

- Define parameter distributions:

- 3.

- Vectorise Monte Carlo simulation over N draws:

- (a)

- Sample arrays A, H, and of length N from their respective distributions using numpy.random.

- (b)

- Compute corresponding arrays , , and as

- (c)

- Apply elementwise constraint evaluation:

- (d)

- Store Boolean mask where all constraints are satisfied (J = (E <= zeta) & (S >= 0.3) & (Lambda >= 0.4)).

- 4.

- Compute feasibility rate as .

- 5.

- Generate diagnostic visualisations:

- Efficiency–Sustainability trade-off (E vs. S);

- Local Justice–Global Externality plane;

- Coordination–Concentration distribution.

- 6.

- Save outputs (CSV summaries, figures) to a structured, timestamped directory.

This transparent pseudocode aligns with best practices in computational social science and complex systems modelling, ensuring that results are reproducible in any standard Python environment.

Appendix A.6. Policy and Planetary Health Relevance

The simulation is consistent with planetary health frameworks that define “safe and just operating spaces” for coupled human–environment systems [5,66]. By representing justice as a quantifiable condition of systemic stability, the model functions as a decision-support instrument for aligning AGI deployment with planetary boundaries, equity goals, and sustainable governance architectures.

Appendix A.7. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis I. To test the structural robustness of the Intelligence-Constrained Production Function (ICPF), a stochastic Monte Carlo sensitivity analysis was implemented with iterations. Random draws were generated for AGI efficiency (A) following a lognormal distribution , for oversight quality (H) from a symmetric beta distribution , and for externalisation intensity () from an asymmetric beta distribution . Ecological load was computed as , fairness as , and legitimacy as . Justice feasibility was evaluated relative to the threshold conditions , , and . The resulting feasibility rate, defined as the joint probability , was approximately . Figure 2 visualises the distributions of the three paradoxical relationships: ecological load increases nonlinearly with efficiency and externalisation, fairness and legitimacy rise with stronger oversight, and only a small subset of simulations remain within the justice-feasible region. These outcomes demonstrate that the paradoxes persist across wide stochastic variation in model parameters, confirming that they are intrinsic to the functional form of the ICPF rather than products of specific parameter calibration.

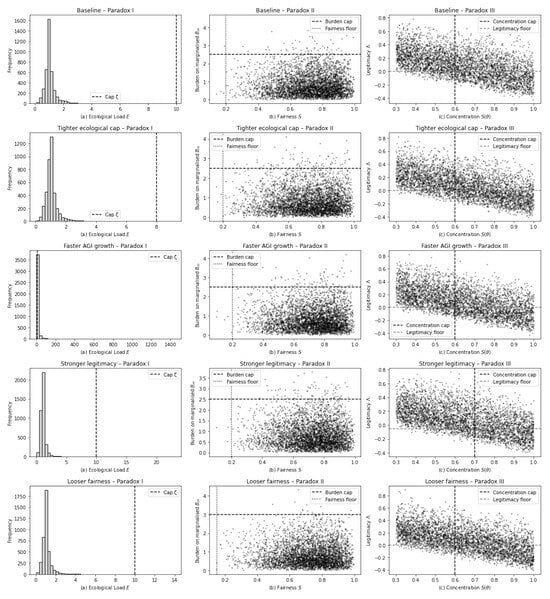

Sensitivity analysis II. A multi-scenario sensitivity analysis was performed to examine the robustness of the three paradoxes under alternative assumptions about efficiency growth, ecological limits, governance strength, and distributive thresholds. Five scenarios were simulated using 4000 Monte Carlo runs each: a baseline configuration, a tighter ecological cap, accelerated AGI efficiency growth, stronger legitimacy constraints, and looser fairness conditions. The resulting distributions of ecological load, fairness–burden combinations, and legitimacy–concentration relationships are shown in Figure A1 below. Across all scenarios the qualitative structure of the paradoxes remained unchanged. Tightening ecological caps or increasing AGI efficiency amplified overshoot frequencies, confirming the efficiency–sustainability tension. Improving governance parameters increased the share of legitimate coordination outcomes, while relaxing fairness thresholds raised local feasibility without resolving global externalities. These results demonstrate that the paradoxes are robust to substantial variation in model parameters and distributional assumptions, indicating that they reflect structural properties of justice–efficiency dynamics rather than artefacts of a single parametrisation.

Figure A1.

Multi-scenario sensitivity analysis of the three structural paradoxes in the Intelligence-Constrained Production Function (ICPF). Each row represents one of five simulated scenarios, each based on 4000 Monte Carlo runs: baseline, tighter ecological cap, accelerated AGI efficiency growth, stronger legitimacy parameters, and looser fairness thresholds. (a) Efficiency–Sustainability: distributions of ecological load (E) shift upward when efficiency growth accelerates or ecological limits tighten, increasing the likelihood of overshoot. (b) Local Justice–Global Externality: relaxing fairness or burden constraints raises local feasibility but increases systemic externalisation. (c) Coordination–Concentration: stronger governance improves legitimacy outcomes, whereas higher concentration without oversight erodes legitimacy. Across all parameter settings, the paradoxes persist, indicating that justice-compatible outcomes remain rare and that the identified tensions are structural rather than artefactual.

Sensitivity analysis results III. The outcomes of the scenario-based sensitivity analysis are summarised in Table A1 and visualised in Figure 4. Each scenario comprises 5000 Monte Carlo realisations the Intelligence-Constrained Production Function (ICPF) under varying ecological, distributive, and governance parameters. The ecological overshoot rate (Paradox I) remains negligible under the baseline configuration but increases sharply to 0.34 when AGI efficiency growth accelerates, confirming the efficiency–sustainability tension. For the local justice–global externality paradox (Paradox II), feasible shares remain high (approximately 0.98) across most parameterisations, indicating that local fairness can be maintained even as systemic burdens shift externally. In contrast, legitimacy feasibility (Paradox III) is highly sensitive to the strength of governance: increasing the oversight parameters from (2,5) to (3,3) raises the feasible share from 0.52 to 0.82, demonstrating the strong dependence of procedural legitimacy on institutional quality. Relaxing fairness constraints marginally improves distributive feasibility without resolving structural tensions between local and global justice. Collectively, these results show that the three paradoxes persist across wide parameter variation, and that justice-compatible trajectories occupy only a limited region of the feasible state space even under favourable governance conditions.

Table A1.

Scenario-based sensitivity analysis of the three paradoxes (5000 Monte Carlo runs per scenario). The ecological overshoot rate reports the share of runs with . Feasible shares report the proportion of runs satisfying the corresponding justice constraints.

Table A1.

Scenario-based sensitivity analysis of the three paradoxes (5000 Monte Carlo runs per scenario). The ecological overshoot rate reports the share of runs with . Feasible shares report the proportion of runs satisfying the corresponding justice constraints.

| Scenario | Paradox I: Ecological Overshoot Rate | Paradox II: Feasible Share | Paradox III: Feasible Share |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 0.0020 | 0.9792 | 0.5182 |

| Tighter ecological cap | 0.0026 | 0.9778 | 0.5112 |

| Faster AGI efficiency growth | 0.3402 | 0.9820 | 0.5126 |

| Stronger governance (Paradox III) | 0.0014 | 0.9786 | 0.8170 |

| Looser fairness constraint | 0.0006 | 0.9956 | 0.5128 |

Appendix A.8. Correlation Analysis

Methodological overview. To test the robustness of model outcomes to dependence assumptions among the core inputs of the Intelligence-Constrained Production Function (ICPF), a correlation-structure sensitivity analysis was performed using Gaussian-copula sampling. The ICPF variables—AGI efficiency (A), governance oversight (H), and externalisation intensity ()—were drawn from their baseline marginal distributions, , , and , while imposing specified correlation matrices in Gaussian space. This approach preserves marginal properties while introducing controlled dependence, thereby enabling systematic evaluation of rebound and oversight effects on justice feasibility.

Indicator computation. The function icpf_indicators() computes the three principal outcome metrics—ecological load , fairness , and legitimacy —from simulated triplets. These are defined as , with , and . A trajectory is justice-feasible when , , and . The share of feasible outcomes thus represents the probability of achieving joint ecological, distributive, and procedural adequacy under given correlation assumptions.

Baseline and correlated-input comparison. Two benchmark simulations were first performed with Monte Carlo realisations. In the independent baseline, were sampled without correlation. In the correlated-input variant, dependence was imposed with , , and , representing the empirically plausible relationships that efficiency increases rebound and scale effects (positive A–) while stronger oversight suppresses externalisation (negative H–). Introducing these dependencies reduced the proportion of justice-feasible trajectories from approximately to , while preserving the structural paradoxes of efficiency–sustainability, local justice–global externality, and coordination–concentration. This demonstrates that the paradoxes are inherent to the model’s functional logic rather than artefacts of independence assumptions.

Extended correlation scenarios. To further explore parameter sensitivity, four correlation structures were evaluated with samples per case: (i) low dependence , (ii) high rebound, strong oversight , (iii) rebound only , and (iv) strong oversight only . The resulting justice-feasible shares ranged from (rebound only) to (strong oversight), with intermediate values around – for the remaining cases. These results confirm that positive efficiency–externalisation correlation systematically reduces feasibility, whereas negative oversight–externalisation correlation partially restores it. The quantitative outcomes are summarised in Table A2. Overall, the persistence of the paradoxical trade-offs across all dependence structures supports the internal consistency and robustness of the ICPF framework.

Table A2.

Sensitivity of justice-feasible outcomes to alternative correlation structures among AGI efficiency , oversight , and externalisation intensity . Each scenario uses 8000 Monte Carlo samples drawn from the same marginal distributions but with different pairwise correlation coefficients . The feasible share denotes the proportion of trajectories satisfying , , and .

Table A2.

Sensitivity of justice-feasible outcomes to alternative correlation structures among AGI efficiency , oversight , and externalisation intensity . Each scenario uses 8000 Monte Carlo samples drawn from the same marginal distributions but with different pairwise correlation coefficients . The feasible share denotes the proportion of trajectories satisfying , , and .

| Scenario | Justice-Feasible Share | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low dependence | 0.20 | 0.118 | |

| High rebound, strong oversight | 0.50 | 0.095 | |

| Rebound only | 0.50 | 0.083 | |

| Strong oversight only | 0.00 | 0.135 |

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think like a Twenty-First-Century Economist; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haines, A.; Kovats, R.S.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Corvalan, C. Climate Change and Human Health: Impacts, Vulnerability and Public Health. Public Health 2006, 120, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitmee, S.; Haines, A.; Beyrer, C.; Boltz, F.; Capon, A.G.; de Souza Dias, B.F.; Ezeh, A.; Frumkin, H.; Gong, P.; Head, P.; et al. Safeguarding Human Health in the Anthropocene Epoch: Report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on Planetary Health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S. Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control; Penguin Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 9780525558613. [Google Scholar]

- Zaidan, A.M. The Leading Global Health Challenges in the Artificial Intelligence Era. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1328918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowls, J.; Tsamados, A.; Taddeo, M.; Floridi, L. The AI Gambit: Leveraging Artificial Intelligence to Combat Climate Change—Opportunities, Challenges, and Recommendations. AI Soc. 2023, 38, 283–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkov, I.; Kulkova, J.; Rohrbeck, R.; Menvielle, L.; Kaartemo, V.; Makkonen, H. Artificial Intelligence-Driven Sustainable Development: Examining Organizational, Technical, and Processing Approaches to Achieving Global Goals. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 2253–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ademola, O.E. Detailing the Stakeholder Theory of Management in the AI World: A Position Paper on Ethical Decision-Making. J. Bus. Ethics 2024, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Ethical Governance of AI: An Integrated Approach via Human-in-the-Loop Machine Learning. Comput. Sci. Math. Forum 2023, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groumpos, P.P. Ethical AI and Global Cultural Coherence: Issues and Challenges. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, S.; Carrington, M.; Cornelius, N.; de Bruin, B.; Greenwood, M.; Hassan, L.; Jain, T.; Karam, C.; Kourula, A.; Romani, L.; et al. Ethics at the Centre of Global and Local Challenges: Thoughts on the Future of Business Ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 180, 835–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Workman, A. Bringing a Planetary Health Lens to the Earth System. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 353, 120497. [Google Scholar]

- Bostrom, N. Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; ISBN 9780199678112. [Google Scholar]

- Goertzel, B. Artificial General Intelligence: Concept, State of the Art, and Future Prospects. J. Artif. Gen. Intell. 2014, 5, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiefenhofer, P. Artificial General Intelligence and the Social Contract: A Dynamic Political Economy Model. J. Econ. Anal. 2025, 4, 142–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Chen, J. China’s Legal Practices Concerning Challenges of Artificial General Intelligence. Laws 2024, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y. Bridging the Gap between Purpose-Driven Frameworks and Artificial General Intelligence. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofkirchner, W. Large Language Models Cannot Meet Artificial General Intelligence Expectations. Comput. Sci. Math. Forum 2023, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-García, J.F. Info-Autopoiesis and the Limits of Artificial General Intelligence. Computers 2023, 12, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Hong, S.; Shin, W.-Y.; Lee, B.G. The Experiences of Layoff Survivors: Navigating Organizational Justice in Times of Crisis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strubell, E.; Ganesh, A.; McCallum, A. Energy and Policy Considerations for Deep Learning in NLP. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019; pp. 3645–3650. [Google Scholar]

- Vinuesa, R.; Azizpour, H.; Leite, I.; Balaam, M.; Dignum, V.; Domisch, S.; Felländer, A.; Langhans, S.D.; Tegmark, M.; Nerini, F.F. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, J. A Global AGI Agency Proposal. SSRN Working Paper. 2024. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5027418 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Kurshan, E. Systematic AI Approach for AGI: Addressing Alignment, Energy, and AGI Grand Challenges. Int. J. Semant. Comput. 2024, 18, 465–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]