Abstract

Planetary boundary transgressions occur as the result of a conflict between human-engineered systems and the natural life-support systems on Earth. In this paper, we validate the Berkana Institute’s Two Loops Theory of Change which posits that big living systems cannot be changed from within. We can only abandon them and start over. We show that the desired objectives of world peace and planetary health can be attained through a “Planet B” style engineering of human systems to meet the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), sans SDG #8 (Economic Growth) and with the addition of Beyond Cruelty Foundation’s SDG #18 (Zero Animal Exploitation). We show that the transition to fully plant-based systems as envisioned in SDG #18 mitigates all seven planetary boundary transgressions and aids in the development of a regenerative, equitable, and sustainable civilization that we call Planet B.

1. Introduction

Humanity is at a crossroads. The transgression of seven planetary boundaries [1,2,3,4], biosphere integrity, novel entities, biogeochemical flows, climate change, land use, fresh water use, and ocean acidification signals that our relationship with Earth’s life-support systems are in a state of crisis. Two of these transgressions, biosphere integrity and novel entities, are rated as high-risk situations [4], with a high probability of destabilizing Earth’s life-support systems due to very strong boundary transgressions. These transgressions are not random accidents but the predictable outcome of human-engineered systems designed around myths of human supremacy, separation from Nature, and endless economic growth [5]. Attempts to reform such systems from within have repeatedly failed, as entrenched interests and cultural inertia resist fundamental transformation.

This paper takes a systems engineering perspective for addressing the twin desired objectives of world peace and planetary health. Systems engineering is a discipline concerned with analyzing why systems behave the way they do as well as synthesizing system solutions that meet those desired objectives. This paper builds upon the Berkana Institute’s Two Loops Theory of Change [6,7], which posits that large, living systems cannot be transformed through internal reform alone. Instead, true transformation occurs when new systems are created that render the old ones obsolete. To validate this, we examine persistent legacies of injustice, such as human slavery [8] and colonialism [9], and show that they have morphed rather than disappeared, despite formal abolitions. The historical continuity of these systems underscores the inadequacy of reforms from within.

In response, this paper presents a systems engineering framework for building Planet B [10], a regenerative, compassionate civilization intentionally designed to meet global objectives of world peace and planetary health. Unlike the current paradigm, Planet B is grounded in life-affirming values and ethical axioms that honor all beings. We critique the mainstream UN Sustainable Development Goals [11] (SDGs) for being structurally compromised by SDG #8: Decent Jobs and Economic Growth, which promotes endless economic growth, a goal that is fundamentally at odds with ecological stability. Instead, we propose the inclusion of Beyond Cruelty Foundation’s (BCF’s) SDG #18: Zero Animal Exploitation [12] as a critical and necessary upgrade to the UN SDG framework.

SDG #18 provides a much stronger countervailing force to the two high-risk planetary boundary transgressions, biosphere integrity and novel entities, than half-measures such as the EAT-Lancet Planetary Health Diet (PHD) [13], which call for a 50% reduction in animal foods consumption without addressing the foundational myths on Planet A. Since Earth’s life-support systems are highly complex with multiple nonlinear feedback loops, they are difficult to model accurately. The precautionary principle dictates that we go beyond half-measures in correcting their high-risk vulnerabilities, since Earth is the only planetary home available to us at the moment.

This paper assumes that human societies collaboratively engaged in rewilding and restoring the stability and long-term viability of Earth’s life-support systems on Planet B would be fundamentally nonviolent towards each other and towards other non-human species. The analogy is that of members of a bickering family that form a bucket brigade to put out their house fire and rebuild their home together, with all prior differences forgotten. We do not expect nonviolent interspecies relationships across non-human species boundaries, preserving natural balancing mechanisms within ecosystems [14,15,16,17].

This paper now introduces six key elements which together support a transition to Planet B. Each element is covered as an independent section in Section 2, Section 3, Section 4, Section 5, Section 6 and Section 7 in the pages that follow:

- The Intractability of Legacy Systems (S2)

In this section, we examine how global systems of domination, such as slavery and colonialism, have persisted under new forms despite official abolishment. This analysis underscores the validity of the Berkana Institute’s assertion that systemic change must emerge from outside existing paradigms.

- Foundational Myths vs. Foundational Axioms (S3)

We identify the dominant cultural myths that perpetuate planetary destruction, such as the myth of human supremacy [18], separation from Nature [19], and the necessity for endless economic growth [20]. In contrast, we articulate a new set of foundational axioms rooted in compassion, interdependence, and nonviolence that must underpin sustainable systems on Planet B.

- Dropping Invalid Goals (S4)

In this section, we propose a validity test for goals and explore how SDG #8: Decent Jobs and Economic Growth fails this validity test and compromises the integrity of the entire UN SDG framework. We note that infinite economic growth on a finite planet leads to ecological overshoot, resource depletion, and social inequity [21], which directly undermine the remaining goals that the SDGs aim to achieve.

- Including Valid Goals (S5)

We show how adopting SDG #18: Zero Animal Exploitation catalyzes systemic healing. By eliminating animal exploitation, we reduce greenhouse gas emissions, restore ecosystems, improve human health, and foster ethical coherence. We present evidence that a global transition to plant-based systems directly addresses all seven planetary boundary transgressions while advancing every other SDG.

- Designing Planet B (Fully Plant-Based Systems) (S6)

In this section, we outline a non-coercive socio-technical system architecture for reconfiguring agriculture, food supply chains, and economic and cultural practices around exclusively plant-based principles. This design prioritizes ecological regeneration, equitable resource distribution, and human health, making SDG #18 actionable from local communities to global governance. We include a case study of Sadhana Forest [22] in India to show that these reconfigurations are ongoing.

- Transitioning to Planet B (S7)

We present strategies for implementing the transition to Planet B through policy shifts, technological innovations, learning initiatives, and grassroots movements. Special emphasis is placed on cultural transformation, economic realignment, and the role of global collaboration in scaling plant-based systems.

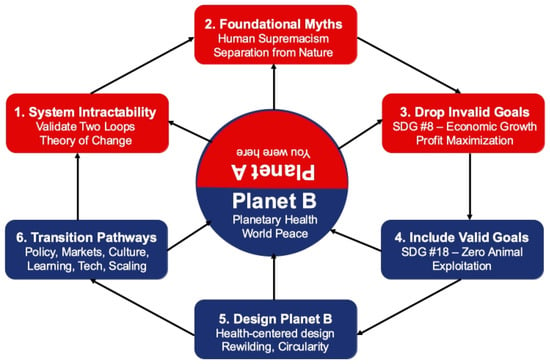

By integrating these six elements into a circular flow for continuous refinement as shown in Figure 1, we claim that a transition to Planet B is both technologically feasible and urgently necessary. It is through the deliberate design and adoption of plant-based systems that humanity can achieve the twin goals of world peace and planetary health. It is most likely the only viable pathway to a just, sustainable, and thriving future for all life on Earth.

Figure 1.

Planet B system design flow (Planet B is the world of Planet A turned upside down). Elements primarily concerned with the analysis of legacy system intractability are colored in red and those primarily concerned with the synthesis of a new sustainable system are colored in blue. The arrows indicate the dependencies of the analysis/synthesis steps during the system design flow.

2. The Intractability of Legacy Systems

2.1. Definition and Properties

A system is an organized framework to accomplish an objective. In this paper, legacy systems denote large, adaptive systems such as economies, states, food regimes, and knowledge institutions that are as follows:

- (i)

- Multi-layered with technological, legal and cultural characteristics;

- (ii)

- Self-stabilizing via feedback on resource flows, incentives, and norms.

As living systems, when perturbed, they reconfigure to preserve core properties even as surface features are reformed. Three system properties explain their resistance to change from within:

Narrative lock-in. Firstly, foundational stories on human supremacy, scarcity, and economic growth act as high-level controllers that bound the solution space for problems that arise. Solutions outside this space are treated as “unrealistic,” regardless of merit.

Institutional inertia. Secondly, laws, infrastructures, and professional societies propagate past decisions even as they become outdated. For instance, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) continues to use the 1996 reporting guidelines for greenhouse gas emissions [23], even though climate science has progressed by leaps and bounds since 1996.

Political-economic capture. Thirdly, powerful beneficiaries shape rule-sets, metrics, and even the framing of scientific problems, redirecting proposed changes toward efficiency tweaks while leaving core system characteristics untouched.

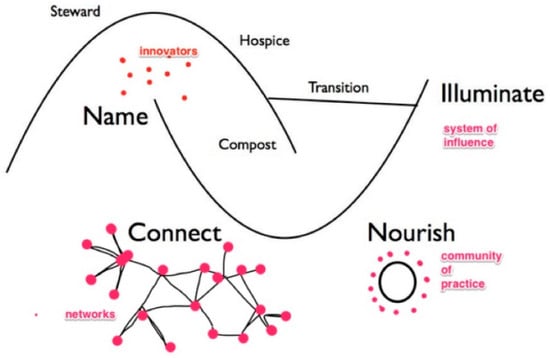

These properties map directly onto the Berkana Institute’s Two Loops model (Figure 2). As the incumbent loop matures, internal repair capacities privilege continuity, while genuine reforms accumulate in a parallel, emergent loop.

Figure 2.

The Berkana Institute’s Two Loops Theory of Change (source: Berkana Institute).

2.2. Abolition Without Erasure

Since the 19th-century legal abolition of chattel slavery [8] did not abolish its economic purpose, the equivalent of slavery re-emerged through debt peonage, convict leasing, racialized policing, and later through mass incarceration. From a systems perspective, slavery was morphed rather than erased since coercive labor was reinstantiated through new legal encodings. The incumbent loop preserved the following:

- (a)

- A cheap, disciplined labor pool;

- (b)

- A punitive control apparatus; and

- (c)

- Racialized hierarchies that rationalize unequal extraction.

The courts, media, and the education system performed narrative work to normalize these surface-level changes [24]. This shows that even well-intentioned genuine reforms fail when the system’s objective function remains intact.

2.3. Independence Without Decolonization

Formal decolonization in the 20th century dismantled imperial administrations yet left the extractive function largely unchanged. Post independence, extraction from the colonies was achieved through unfavorable terms of trade, debt conditionalities, export-oriented agriculture, unequal intellectual property regimes, and health care paradigms aligned with donor interests. For instance, the European Economic Commission funded the National Dairy Development Board in India to increase dairy consumption even though the majority of Indians cannot digest lactose [25]. India is now the largest dairy producer and the second largest beef exporter in the world, while also becoming the diabetes capital of the world.

In control-theoretic terms, net resource transfer from the colonies was maintained through finance, standards, and development expertise rather than military garrisons [9]. The substitution of flags, anthems, and constitutions merely provided surface-level changes sufficient to quell mass unrest.

2.4. Why Climate–Nature Policy Stalls Inside the Incumbent Loop

Contemporary environmental governance inherits this pattern. The unchecked growth of material throughput on a finite planet and a food regime premised on non-human animal exploitation conflicts with planetary carrying capacity and interspecies justice. Yet most solutions privileged inside the incumbent loop optimize emissions intensity, not reversal of harm. Efficiency upgrades, voluntary pledges, and growth-compatible “green transitions” preserve the goal of aggregate expansion of the human enterprise. Simultaneously, high-leverage demand-side measures, such as ending animal exploitation and rewilding, are marginalized as “lifestyle changes” rather than treated as system-level prerequisites. The result is apparent action without meaningful results. While conferences proliferate and metrics improve at the margin, state variables of the planetary life-support system such as biosphere integrity, novel entities, biogeochemical flows, and CO2 emissions continue to transgress beyond safe ranges [4].

2.5. Formal Proposition and Corollary

Proposition. In mature legacy systems, interventions that do not modify the system’s objective function and constraint set will produce only surface-level changes without disrupting the core functions.

Corollary. To terminate harmful functions, e.g., extractive growth and animal exploitation, reforms must (a) replace the objective function, (b) alter constraints and payoffs across layers, and (c) instantiate the new design in parallel institutions capable of outcompeting or rendering obsolete the incumbent institutions.

2.6. Mechanisms of Absorption

The incumbent loop uses four distinct mechanisms to absorb proposed changes without altering its core functionality:

Compensating dynamics. Efficiency gains lower apparent costs, triggering rebound effects that restore and even increase aggregate throughput, as in Jevon’s paradox [26]. For example, animal factory farming increased efficiency and lowered apparent costs, while externalizing environmental and animal welfare costs [27].

Instrument drift. Metrics and models are re-parameterized to legitimate the status quo, e.g., growth-centric success criteria, reclassifying externalities as exogenous.

Co-optation of dissent. Radical critiques are translated into safe managerial programs wherein funding architectures privilege incrementalism.

Cultural containment. Media and education curate the Overton window [28], ensuring that compassion-centric, multi-species ethics remain peripheral to “serious policy”.

2.7. Summary of Legacy Systems Intractability

Historical reforms that left objective functions intact produced surface-level, not structural, changes. The same logic explains contemporary environmental stalemate. Consistent with the Two Loops Theory of Change, durable change requires building a parallel operating system that we call Planet B, whose controllers are compassion, sufficiency, and multi-species flourishing, operationalized via the adoption of SDG #18 and the deliberate design of fully plant-based, regenerative systems.

3. Foundational Myths vs. Foundational Axioms

3.1. Diagnosing the Foundational Myths Structuring Planet A

We use myth in the technical sense of a narrative that contains an element of truth but functions as a high-level controller that constrains admissible policy and design choices. On Planet A, five interlocking myths govern socio-technical organization [10]:

3.1.1. Myth 1: Endless Growth as the Master Objective

Economic expansion is treated as a necessary condition for human wellbeing and institutional stability. The necessity for growth is coded into currency architectures and governance objectives so that political, corporate, and scientific actors are constrained to preserve growth even when it conflicts with ecological limits. This normalization persists even in high-consumption societies already in ecological overshoot who are often considered “too big to fail”, where official plans explicitly commit to cutting emissions without reducing growth [29].

3.1.2. Myth 2: Consumption and Commodification as Social Logic

Consumption is elevated from means to organizing value. Advertising infrastructures continuously stimulate demand, while supply chains are optimized for the accessibility of exotic, discretionary goods rather than universal sufficiency. The result is systemic misallocation so that a food system which procures multiples of required quantities [30] produces chronic hunger and widespread macro/micronutrient deficiency [31].

3.1.3. Myth 3: Separation from Nature and Human Exceptionalism

A story of human separation from the rest of Life, bolstered by cultural and scientific framings of the self as a discrete, competing unit for scarce resources, licenses the differential moral valuation of beings and the routine exploitation of non-human animals [32]. Explicitly speciesist institutions such as slaughterhouses are thereby normalized even as analogous harms among humans are condemned. This asymmetry is a root driver of ecological breakdown and social harms.

3.1.4. Myth 4: Mis-Specified Responsibility for Ecological Breakdown

A fourth, more recent myth narrows causality for ecological breakdown to fossil fuel combustion alone, politically obscuring food system drivers through selective accounting choices [33,34]. This mis-specification diverts effort toward growth-compatible efficiency fixes on the energy infrastructure while marginalizing high-leverage dietary and land use transformations.

3.1.5. Myth 5: Technological Solutions for Environmental Constraints

A fifth myth frames environmental constraints as solvable through future technological innovations. This myth diverts resources and efforts toward technological research and development, while marginalizing behavioral transformations [35].

A secondary example illustrates the mechanism of myth making. The pedagogical association of protein with animal foods and calcium with dairy foods obscures the ubiquity of protein [36] and calcium [37] in all foods, naturalizes animal consumption, and erases plant sources with measurable health and equity consequences.

3.2. Foundational Axioms for Planet B

The transition to Planet B requires axioms that perform the following:

- (i)

- Correct the above myths;

- (ii)

- Re-parameterize institutional objective functions; and

- (iii)

- Ground design/test criteria across sectors.

We synthesize these axioms from whole-system governance frameworks [38] and value transformations necessary for the restoration of planetary health.

3.2.1. Axiom A: Interdependence of All Life

Align governance, law, economics, media, education, and technology with the principles of Life and whole-system health. Peace is illusory if oppression exists anywhere in the Community of Life.

3.2.2. Axiom B: Nonviolence/Zero Animal Exploitation

Recognize non-human animals as moral subjects; institutionalize Ahimsa (non-harming) as a hard constraint. This closes a primary pathway of ecological degradation and social injustice through speciesism.

3.2.3. Axiom C: Sufficiency over Growth

Replace growth imperatives with goals oriented towards planetary healing and purpose beyond the self.

3.2.4. Axiom D: Honesty and Humility as Design Criteria

Evaluate systems against the “5H” litmus test criteria: honesty, humility, health, happiness, and harmony [10]. Reject system architectures that fail these values.

3.2.5. Axiom E: Universal Provisioning Within Planetary Limits

Organize for clean air, healthy soils, pure water, and vitalizing food for all beings; redesign supply chains and production so that universal needs, not luxury consumption, constitute the optimization target.

3.2.6. Axiom F: Distributed, Participatory Governance

Adopt distributed decision architectures that place whole-system health at the core and give standing to human and non-human stakeholders.

3.2.7. Axiom G: Technology Subordinated to Life

Direct scientific and technological advancement to serve whole-system healing rather than throughput expansion. Evaluate tools by their contribution to biosphere integrity and compassion.

3.3. Operationalization and Falsifiability

The axioms above are actionable rather than aspirational. They prescribe the following:

- (i)

- Constraint re-writing, e.g., elimination of exploitation under Axiom B;

- (ii)

- Goal substitution under Axiom C; and

- (iii)

- New evaluation functions under Axioms D–G.

They are empirically testable through system-level indicators already enumerated in governance frameworks, e.g., stabilization and restoration of planetary boundary variables, adoption of distributed governance, and measurable shifts in provisioning quality for humans and other animals.

3.4. De-Programming Myths

Because myths are reproduced through pedagogy and everyday practice, overcoming them must include curricular corrections, e.g., on plant sources of protein and calcium, and narrative reform, along with institutional redesign.

In summary, Planet B requires explicit axioms that reverse the operational myths of Planet A and re-compose our socio-technical control architecture around whole-system health, compassion, and multi-species flourishing.

4. Dropping Invalid Goals

4.1. Why Goals Matter in Systems Engineering

In socio-technical system design, goals instantiate the objective function. They determine which states are considered successes, what trade-offs are admissible, and how feedback is interpreted. When an objective is ill-posed, the system will optimize toward harmful states no matter how sophisticated the policies, models, or technologies layered on top. Section 3 proposed axioms for Planet B regarding interdependence, nonviolence, sufficiency, equity, and honesty. Here, we operationalize those axioms by identifying and retiring goals on Planet A that are biophysically infeasible, systemically incoherent, or ethically inadmissible. Dropping invalid goals is a required step in systems engineering to remove opposing forces so that the desired objectives of world peace and planetary health become achievable stable points in human-engineered systems.

4.2. A Validity Test for Goals (GVT)

We define a Goal Validity Test (GVT) with four necessary conditions:

GVT-F (Feasibility): The goal is compatible with planetary boundary constraints and thermodynamic or biogeochemical realities.

GVT-C (Coherence): Pursuit of the goal does not systematically undermine other agreed upon goals.

GVT-E (Ethical admissibility): The goal is consistent with Axioms A–B so that it does not require institutionalized harm to humans or other animals.

GVT-M (Meaningful measurement): Indicators track ends such as wellbeing and ecological integrity, rather than proxies such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP) that detach from those ends under optimization pressure.

A goal that fails any one of GVT-F/C/E/M is invalid at the top level and should be retired or reframed.

4.3. Case Analysis: SDG #8 (“Sustained Economic Growth”) Fails GVT

SDG #8 installs “sustained economic growth”, often measured as real GDP growth, as a global objective. In control-theoretic terms, it acts as a master set-point that undermines other goals.

GVT-F (Feasibility) failure. At the planetary scale, GDP growth remains strongly coupled with aggregate energy and material throughput. While energy/material/waste intensity reductions are possible, the rate and scope of reductions needed to grow GDP indefinitely and re-enter the safe operating space of the life-support systems of the planet has not been observed at a global scale. Treating growth as a standing objective therefore violates the feasibility condition under multiple boundaries such as climate, biosphere integrity, land system change, biogeochemical flows, and novel entities.

GVT-C (Coherence) failure. A growth set-point exerts negative pressure on other SDGs, such as, for example, SDG #3: Good Health and Well Being. At the moment, 90% of the health care economy is engaged in treating 15 chronic conditions caused by eight risky behaviors [39]. When growth is a priority, those risky behaviors are encouraged to grow the health care economy, causing failure on SDG #3.

When conflicts arise between any goal and the growth set-point, budget, policy, and narrative systems typically prioritize “green growth” pathways over alternatives with higher leverage but lower compatibility, e.g., dietary shifts, rewilding, and sufficiency. Coherence is lost because the optimization target reinterprets constraints as adjustable.

GVT-E (Ethical) failure. The growth objective structurally favors sectors whose value-added scales with commodification of beings and habitats. In practice, this has normalized the mass use of non-human animals as inputs for food, fashion, testing, and entertainment. That reliance conflicts with Axiom B (nonviolence), rendering the goal ethically inadmissible as a top-level aim.

GVT-M (Measurement) failure. GDP conflates desirable and undesirable activity, is blind to depletion and suffering, and is trivially gamed via monetization and externalization [40]. As an objective, it incentivizes proxies rather than end-state improvements on health, equity, and ecosystem vitality.

In conclusion, SDG #8, in its growth-as-goal formulation, fails all four validity conditions. On Planet B, growth may occur locally as a side-effect of healing and provisioning, but it cannot serve as a goal.

4.4. Additional Invalid Goal Patterns Linked to Boundary Transgressions

Beyond SDG #8, several common objectives should be retired or reframed:

“Increase per capita animal-source protein” as a nutrition goal.

GVT-F: Expands methane, nitrous oxide, land conversion, and freshwater use, while incurring carbon opportunity cost by displacing rewilding.

GVT-E: Requires institutionalized harm to sentient beings and therefore violates Axiom B.

Replacement on Planet B: Protein adequacy from plants with amino-acid literacy and culturally resonant cuisines.

“Maximize yields via input intensification” as an agricultural goal.

GVT-F/C: Drives novel entities and biogeochemical boundary pressures, while undermining soil biota and biosphere integrity.

Replacement on Planet B: Maximize nutritional provisioning within planetary boundaries.

“Net-zero by X while sustaining growth” as a climate goal.

GVT-F/C: Relies on speculative carbon capture technologies and land claims that collide with food, water, and biodiversity goals.

Replacement on Planet B: Rapid absolute reductions achieved through food systems transformations, elimination of wasteful activities, and ecological restoration projects.

“Expand animal farming productivity and exports” as a rural development goal.

GVT-F/E: Entrenches boundary pressures and normalized harm, while exposing communities to zoonoses and market volatility.

Replacement on Planet B: Rural prosperity via plant-based value chains, restoration livelihoods, community kitchens, and agroforestry.

4.5. Anticipating Counter-Arguments

“Growth is needed to end poverty”. Empirically, large wellbeing gains derive from targeted provisioning of nutrition, clean water, primary health, education, and resilient housing, not aggregate GDP increases per se. The Planet B reframing is needs-first. Directly focusing on universal provisioning within planetary boundaries can easily outperform trickle-down growth in cost-effectiveness, resource usage, and ethics.

“Green growth via absolute decoupling is coming”. Even if pockets of absolute decoupling appear, a growth set-point reintroduces rebound and offshoring. Planet B adopts sufficiency in over-consuming contexts and capability expansion in under-consuming contexts, both within explicit ecological limits.

“Animal agriculture is culturally important”. While cultural continuity is desirable, we know that culture also evolves. Nevertheless, special consideration must be given to help transition pastoral societies, who are finding it increasingly difficult to maintain their way of life in the face of increasing global temperatures [41]. Planet B centers freely chosen plant-based traditions and offers dignified transition pathways, expanding culinary identity while aligning with nonviolence and planetary health.

5. Including Valid Goals

5.1. UN SDGs as a Starting Point

We propose using the UN Sustainable Development Goals [11] (SDGs) as the starting set of valid goals for Planet B since all 195 nations at the UN have signed up to meet these goals by 2030. Of the 17 UN SDGs, we strongly recommend dropping the invalid goal SDG #8 for reasons detailed in Section 4. We suggest the inclusion of additional goals be governed by a Goal Inclusion Protocol (GIP) as outlined below.

5.2. Goal Inclusion Protocol

Section 4 specified a Goal Validity Test (GVT: Feasibility, Coherence, Ethical admissibility, and Meaningful measurement). We now define a Goal Inclusion Protocol (GIP) as follows.

A goal is included when

- (i)

- It passes GVT;

- (ii)

- It improves at least one planetary-boundary state variable without degrading any other; and

- (iii)

- It advances at least one of the Section 3 axioms (interdependence, nonviolence, sufficiency, equity, honesty).

Formally, let x denote system states, b(x) planetary boundary functions, and w(x) wellbeing functions across humans and other animals. A goal g is valid if

under plausible policy and technology sets, with ethical admissibility satisfied.

Δbi (x) ≤ 0 ∀ i, ∃ j: Δbj (x) < 0, Δwi (x) ≥ 0 ∀ i,

5.3. Case Analysis of SDG #18: “Zero Animal Exploitation”

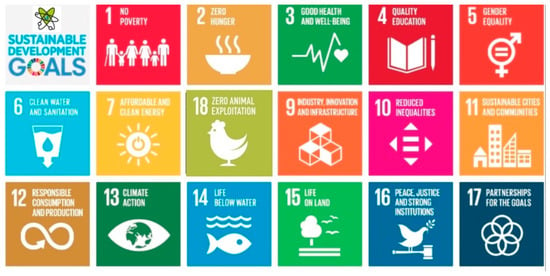

The dropping of SDG #8 and the inclusion of BCF’s SDG #18: “Zero Animal Exploitation” leads to a modified set of UN SDGs as show in Figure 3. The inclusion of BCF’s SDG #18 is justifiable under the Goal Inclusion Protocol. Since removing animal exploitation simultaneously relaxes multiple biophysical constraints and corrects for speciesism, a deeply ethical defect on Planet A, SDG #18 actually functions as a keystone goal on Planet B. In optimization terms, SDG #18 changes the feasible set F by

Figure 3.

Recalibrating UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with SDG #18 instead of SDG #8 (source: UN SDGs and Beyond Cruelty Foundation).

- (i)

- Eliminating high-harm technologies and practices from the admissible policy space; and

- (ii)

- Unlocking high-benefit land use changes for rewilding that were previously infeasible.

Animal agriculture uses 37% of the ice-free land area of the planet for grazing alone [42]. On average, land animals consume 39 kgs of food in order to produce 1 kg of animal biomass for human consumption, in terms of dry weight. Animal matter constitutes 15% of the food consumed by humans today, while plants provide the remaining 85%. About two-thirds of the biomass extracted from croplands is also consumed by farmed animals.

Consequently, the inclusion of SDG #18 frees nearly 40% of the ice-free land area of the planet for rewilding, mitigating all seven transgressed planetary boundaries—biosphere integrity, novel entities, biogeochemical flows, climate change, land use, water use, and ocean acidification. For SDG #18,

Δbi (x) < 0 ∀ i

The Beyond Cruelty Foundation has documented the means by which SDG #18 facilitates the implementation of the UN SDG set [12]. Of the remaining 16 SDGs, sans SDG #8, two need to be recalibrated to cohere with SDG #18:

SDG #14: “Life Below Water”—Conserve and restore the ocean, rivers, and marine life to their natural state. On Planet A, this goal is about exploiting the oceans, rivers, and marine life for human use. The official UN description of this goal reads, “Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, rivers and marine resources for sustainable development”.

SDG #15: “Life on Land”—Conserve and restore native ecosystems, combat desertification, halt and reverse land degradation, and halt and reverse biodiversity loss. Once again, on Planet A, this goal was about exploiting land for human purposes without causing too much damage. The official UN description reads, “Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, halt and reverse land degradation, and halt biodiversity loss”.

5.4. The Valid Goal Set (VG)

Concomitant with SDG #18, we propose a minimal, mutually reinforcing set of Valid Goals (VGs) that together instantiate Planet B’s objective function.

VG1—Zero Animal Exploitation (SDG #18, by adoption). Organize provisioning, science, and culture so that animals are never treated as commodities. Expand sanctuary and wildness.

VG2—Universal Plant-Based Provisioning. Ensure affordable, delicious, culturally resonant whole-food plant-based diets as the social default in schools, health care settings, workplaces, and public venues.

VG3—Large-scale Rewilding and Ecological Connectivity. Restore and connect habitats (land and sea) at landscape scale with community guardianship.

VG4—Rapid Methane and Nitrous Oxide Decline. Achieve steep, near-term declines through dietary shifts, manure elimination, legume-centric agronomy, and soils-first nutrient management.

VG5—Soil and Water Integrity. Regenerate soil organic matter and watershed function via perennial polycultures, agroforestry, and nutrient budgets aligned with local biogeochemistry.

VG6—Equity-First Universal Basic Provisioning. Meet needs for food, shelter, care, education, and mobility within ecological caps. Prioritize communities historically excluded.

VG7—Participatory, Multi-species Governance. Institutionalize deliberation (citizens’ assemblies) and Animal Guardians with standing. Embed Rights-of-Nature in local charters.

VG8—Knowledge Commons for Healing. Open-source Research and Development (R&D) and data for legumes, pulses, minimally processed foods, restoration, and ecological monitoring.

These goals satisfy GVT by construction and create positive cross-elasticities so that progress on any one facilitates progress on others (e.g., VG1 → VG3/4 via land return and decline in methane emissions).

5.5. Measurement Architecture

Valid goals require indicators that track ends:

Animal wellbeing through sanctuary and wild population flourishing indices. We can create an animal exploitation index by tracking factory farms and experimentation facilities.

Dietary provisioning through cost and availability of a healthy plant-based basket, uptake in public provisioning, and micronutrient adequacy.

Rewilding through measuring the fraction of protected/connected habitats, edge-to-core ratios, functional diversity.

Methane/N2O through measuring sectoral emissions with high-frequency monitoring and nutrient surplus maps.

Soil/water through measuring soil organic carbon (SOC), infiltration rates, evapotranspiration balance, and watershed nutrient loads.

Equity evaluated through wellbeing measures, e.g., P90–P10 gaps in nutrition, morbidity, and access.

Governance through measuring participation rates in assemblies and decisions reflecting multi-species considerations.

Knowledge commons through open-licensing share and adoption latency from research to practice.

We can apply floors on provisioning and caps on ecological impact, with early-warning leading indicators, e.g., biodiversity counts, to avoid overshoot.

5.6. Incentive Alignment Without Coercion

Planet B privileges choice architectures over mandates: plant-based defaults in public services, community kitchens, recognition and celebration of restoration and sanctuary stewardship, open procurement that guarantees demand for legumes, pulses, fruits, vegetables, and perennials. Incentives are framed as opportunities to opt in to healthier, tastier, kinder, and more resilient ways of living.

5.7. Robustness, Risks, and Mitigation

Risks include substitution toward ultra-processed plant foods, inequitable access, or ecological leakage. The corresponding mitigations include nutritional standards that favor minimally processed foods, affordability guarantees, trade and finance alignment with VG1–VG6, and continuous monitoring with adaptive management. Governance risks can be mitigated by rotating citizens’ assemblies, transparent data, and locally grounded Animal Guardians.

6. Designing Planet B (Fully Plant-Based Systems)

6.1. The Aim of the Design

In this section, we specify a deployable, non-coercive socio-technical architecture that renders SDG #18: “Zero Animal Exploitation” operational from local to global. The design treats Planet B as a controllable system with

- (i)

- Hard constraints on planetary boundaries and nonviolence toward non-human animals;

- (ii)

- Objective functions on universal nutritional adequacy, health, equity, and joyful participation;

- (iii)

- Actuators for procurement, culture, and finance; and

- (iv)

- Sensors to ensure transparency and open source development.

We use an “AhimsaCoin” economy [43] as the monetary substrate that aligns everyday incentives with SDG #18 without compulsion.

6.2. Constraints and Requirements

The Planet B design space is bounded by the following two constraints and three hard requirements:

- (i)

- Ethical constraint: Institutionalized harm to non-human animals is out of scope in public systems, while rewilding and sanctuaries are in scope.

- (ii)

- Biophysical constraints: Rapid declines [44] in CH4 and N2O are design objectives within local N, P biogeochemistry. We use soil, water, and biosphere integrity caps with carbon opportunity maximization via land return to Nature.

- (iii)

- Provisioning requirement: Ensure affordable, culturally resonant whole-food, plant-based (WFPB) diets with macro/micronutrient adequacy across life stages.

- (iv)

- Equity requirement: In order to ensure rapid adoption of Planet B, we propose preferential gains for historically marginalized populations, with dignified, supported transitions for those with livelihoods currently coupled to animal exploitation.

- (v)

- Resilience requirement: We propose portfolio diversity in crops, regions, and storage, with distributed control and open knowledge in order to ensure graceful degradation under environmental stresses.

6.3. The AhimsaCoin Economic Substrate

In order to operationalize SDG #18, we propose an AhimsaCoin economic substrate to replace growth compulsion and scarcity assumptions with a bottom-up allowance from Nature that encodes equality, sufficiency, and nonviolence. This resonates with the popular idea that Nature has endowed all human beings with an inalienable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Unit and issuance: One AhimsaCoin (A) represents the productive output of 1 m2-year of the Earth’s surface. A is offered directly to people at a uniform cadence (baseline: 1 A every ~50 min), creating a lifelong, unconditional stream that secures basic provisioning without debt.

Throughput-linked retirement: AhimsaCoins are retired (“burned”) at point of biocapacity use via publicly auditable “retirement coefficients” rk of A per unit activity k.

Plant-based provisioning causes low harm with nutrient efficiency and therefore low rk.

Ecological restoration and rewilding causes negative effective rk and earns dividends in A for the community with verified outcomes.

Animal exploitation activities result in non-settling under the protocol since the ledger does not clear transactions that instantiate exploitation. This is not coercion of individuals but rather an institutional choice. Public systems, major buyers, and communities choose AhimsaCoin flows because they secure freedom-from-want while aligning with SDG #18. Actors preferring exploitative flows can still transact in legacy currencies, but Planet B institutions route purchasing power through A, thereby shifting markets nonviolently.

Choice architecture: We propose public procurement in A, with multi-year, cost-plus contracts for legumes, grains, produce, and minimally processed staples, all settled in A.

We propose universal basic provisioning with endowment streams covering a WFPB reference basket and essential services. Unspent A lapses in demurrage, rewarding sufficiency and discouraging hoarding.

Transition finance is provisioned through A with time-bound income bridges, retraining, and cooperative conversions for workers and stakeholders pivoting from animal-dependent livelihoods.

With open ledgers and governance, citizen assemblies with Animal Guardians set rk, audit identity and retirement processes, and adjust cadence with population and ecological restoration feedback.

Expected Result: With institutional adoption of A, non-settlement of exploitation activities on A flows, and positive dividends for ecological restoration on A, we expect that the feasible set of everyday choices would tilt decisively towards plant-based provisioning and rewilding without policing private behavior.

6.4. Food Production System

The food production system is optimized for a diverse crop portfolio, comprising

- (i)

- Pulses such as beans, peas, lentils, chickpeas, peanuts and soy;

- (ii)

- Whole grains such as millets, sorghum, rice, wheat, corn and oats;

- (iii)

- Roots, tubers, vegetables, fruits;

- (iv)

- Nuts and seeds.

In the absence of animal farming, the cropland necessary for producing these crops for human consumption is expected to be reduced by 25%, alleviating pressure on the biogeochemical cycle planetary boundary transgression [44]. In addition, we propose transitioning to multi-species climate-resilient rotations with legume covers and living mulches for maximizing yield and soil carbon accrual.

We prefer perennial crops and agroforestry with alley cropping, shelter belts, riparian buffers and tree–crop mosaics to regulate the microclimate and provide a habitat for native animal species. We can employ water management systems using rainwater harvesting, drip irrigation where appropriate, with coordinated watershed plans. Energy is provisioned with on-farm solar and battery storage with low tillage, low horsepower implements, and machinery pools owned by producer co-ops.

6.5. Ecological Restoration

We convert former grazing land and feed-crop land into native grasslands, wetlands, forests, and coastal ecosystems connected at landscape scales. We prioritize rewetting and restoration of peatlands and mangroves to restore high-carbon, high-biodiversity systems. Following the abolishment of animal exploitation, we can promote lifetime caring sanctuaries for formerly domesticated non-human animals, integrated with ecological restoration and education. We can encourage indigenous-led compacts and community conservancies with biodiversity credits tied to verified outcomes and not as offsets against ongoing harm.

6.6. Health System Integration

The normalization of Lifestyle Medicine and the preponderance of wellness centers over hospitals characterizes Planet B health systems [45]. The health system promotes food as medicine protocols with diet-first interventions for diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) and Blood Pressure (BP), and Body Mass Index (BMI) reductions. Nutrition and culinary competencies are embedded in medical, nursing, and public health education with community health workers trained as food guides for the public.

Both individual and planetary health integration is accomplished through performance metrics on reductions in diabetes and CVD incidence, LDL/HbA1C/BP distributions, increases in rewilded and connected areas, soil organic carbon content, nutrient surpluses, and functional diversity as well as decreases in CH4 and N2O atmospheric concentrations.

6.7. Governance and Participation

We expect cities, regions, and entire nations to adopt SDG #18 and participate in the AhimsaCoin economy through open deliberation.

We appoint councils for the Community of Life with indigenous leadership, scientists, ethicists, youth, and Animal Guardians to create and review plans.

Citizen assemblies co-design menus for community kitchens, rewilding maps, procurement specs, and AhimsaCoin retirement coefficients, rk.

We drive adoption through plant-based defaults, transparency, celebration, and support, rather than sanctions.

6.8. Case Study of Sadhana Forest

Sadhana Forest is a volunteer-based project in Auroville, Tamil Nadu, India, that has successfully restored the critically endangered Tropical Dry Evergreen forest native to that region [22]. Founded by Yorit and Aviram Rozin in 2003, Sadhana Forest engages local communities and international volunteers in the reforestation and water conservation efforts. It uses many of the sustainable living practices rooted in compassion and selfless service as outlined in this section, including plant-based agroforestry that is free of domesticated animal inputs.

Sadhana Forest conducts workshops, open to the public, free of charge, on plant-based nutrition, plant-based cooking classes, and connecting with animals. It hosts weekly documentary screenings, monthly vegan potlucks, and annual vegan forest festivals, all free of charge to the public.

On 70 acres of land that was barren in 2003, Sadhana Forest successfully planted over 300,000 trees and naturally regenerated twice as many trees, contributing to the return of 150 wild animal species native to that region. It is a shining example of what can be achieved, all over the world, on Planet B.

6.9. Summary of Planet B Implementation

The blueprint for Planet B outlined in this section ensures that SDG #18 is realized not by edict but by making compassionate, plant-based provisioning the easiest, cheapest, tastiest, and celebrated choice. The AhimsaCoin economic substrate is designed to align money with morality and ecological restoration.

7. Transitioning to Planet B

The most efficient way to achieve this transition to Planet B is through a multi-pronged approach with massive grassroots campaigns and strategic cultural shifts. Here are seven strategies for accomplishing this:

- (i)

- Normalize plant-based living fast. Flood the culture with images, stories, role models, and products that make plant-based living feel normal, aspirational, joyful, and easy. Make SDG #18 mainstream, not marginalized.

- (ii)

- Transform institutions simultaneously. Schools, hospitals, government programs, corporate cafeterias, and wherever food is served must rapidly default to plant-based first. Policy change follows culture, but culture follows policy, too. We must work to do both.

- (iii)

- Frame SDG #18 as a justice issue, not just a personal choice. Link SDG #18 to climate justice, food security, indigenous rights, racial justice, and public health. Make it morally obvious, not just a matter of taste or preference. Make compassion non-negotiable.

- (iv)

- Leverage technology and media. TikTok, YouTube, podcasts, multiplayer games, and apps can be leveraged to own the cultural conversation. Short-form storytelling, movies, viral campaigns, humor, and art can be used to reach hearts and sway minds.

- (v)

- Build local self-sustaining models. Create plant-based farms, cooperatives, villages, and communities that thrive visibly as proof of concept for Planet B. If people can see it, they would believe it is possible.

- (vi)

- Make plant-based the easy, affordable default. Work to reduce cost barriers, increase accessibility, and dismantle the false image of sacrifice. Plant-based living must look and feel like abundance, not deprivation.

- (vii)

- Activate courageous leadership. Religious leaders, politicians, educators, scientists, and artists must find the courage to proclaim that plant-based is planet-based and the future is nonviolent.

This is how we shift the culture, policies, economy, and ultimately the heart. We have no choice but to do so.

8. Discussion

This paper advanced a systems engineering pathway to world peace and planetary health by

- (i)

- Diagnosing why incumbent, living systems resist reform;

- (ii)

- Replacing their controlling myths with explicit axioms;

- (iii)

- Dropping invalid goals, chiefly economic growth as a standing objective (SDG #8); and

- (iv)

- Including valid goals centered on interdependence, nonviolence, sufficiency, equity, and honesty.

We then specified an implementable architecture for Planet B—fully plant-based, non-coercive socio-technical systems that operationalize SDG #18: Zero Animal Exploitation—and proposed AhimsaCoin as a nonviolent monetary substrate that aligns everyday incentives with those goals without coercion. We then discussed transition pathways to help individuals, communities, and all of humanity to transition from Planet A to Planet B.

Our system engineering is designed to accomplish non-coercive transition, with the benefit of near-term cooling and long-term healing. Dietary shifts (VG1–VG2) and land return (VG3) unlock immediate methane and nitrous oxide declines while creating durable carbon drawdown through rewilding and perennial agroecologies (VG5). Universal plant-based provisioning, living income benchmarks, and financing in the AhimsaCoin economic substrate reduce the transition risk for workers and communities currently tied to animal-dependent livelihoods.

To move from theory to dominance, we recommend three concurrent pilots as Minimum Viable Experiments (MVE), each with indicators and independent audit:

MVE Cities: A total of 10–20 cities to adopt plant-based defaults across schools, hospitals, and public workplaces. Public procurement settles in the AhimsaCoin economic substrate. Primary outcomes to be monitored include cost and uptake of WFPB diets, CH4/N2O footprints of city food purchases, diet-related clinical markers, and equity gaps.

MVE Land Corridors: Regional retirement of grazing and feed-crop land parcels into connected rewilding experiments with animal sanctuary integration. The primary outcomes to be monitored include habitat connectivity, soil organic carbon, watershed nutrients, biodiversity indices, and restoration dividends paid in A.

MVE Economic Ledgers: AhimsaCoin identity, issuance, and retirement protocols bound to ports, grids, and wholesale markets with citizens’ assemblies setting retirement coefficients. The primary outcomes to be monitored include sectoral retirement intensity, share of public spend in A, leakage rates, and public trust. Each pilot can be conducted on a consent-based, open-source basis and designed for replication.

Open questions remain on the calibration of retirement coefficients. Translating biophysical intensities into fair, comprehensible A-retirement rates requires iterative refinement and citizen oversight. In the long run, feedback from, e.g., satellite data, on observable land, water, and material resource usage would serve to close the loop and ensure the integrity of the calibration. In addition, we have to verify the viability of unique identity and governance in A. We concede that privacy preserving, human-only issuance of A with low fraud risk is non-trivial but achievable. Finally, the WFPB core must be flexible for regional variations, culinary heritage, and specific nutritional contexts.

While exploitative flows may persist in legacy currencies, knowledge commons must be protected from enclosure to keep entry barriers low. However, we believe that these are research-, design-, and institution-building challenges that are not insurmountable.

If this blueprint is sound, then within 24–36 months of MVE implementation we should observe the following:

- (i)

- Significant drops in food system CH4 and N2O per capita;

- (ii)

- Increased habitat connectivity and soil carbon trends;

- (iii)

- Declining public outlays on diet-related disease alongside stable or reduced provisioning costs;

- (iv)

- High public acceptance of A-based procurement and visible reduction in animal exploitation flows in A-settled markets.

Failure to observe these shifts at scale-adjusted thresholds would warrant revision of the system design flows.

9. Conclusions

In closing, Planet B is not a place we travel to. It is an operating protocol that we can instantiate wherever communities choose different axioms, valid goals, and a monetary system that honors Life. The Two Loops model tells us not to waste resources pleading with a mature system to stop being itself. Our engineering design shows us how to build the second loop in which nonviolence is a constraint, sufficiency is encouraged, and freedom is obtained by design.

We contend that this path is neither utopian nor punitive. It is practical, measurable, and available now. Plant-based defaults, rewilding corridors, food-as-medicine, participatory governance with Animal Guardians, and a nonviolent AhimsaCoin economic substrate enhance basic security while guiding the life-support systems of the planet back within planetary boundaries. When enough of us make the choice to transition to Planet B, the old loop will become obsolete by comparison, while world peace and planetary health become realizable objectives, engineered by design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.R.; Methodology, S.K.R.; Formal analysis, S.K.R.; Resources, G.W.-B.; Data curation, G.W.-B.; Writing—original draft, S.K.R.; Writing—review & editing, S.K.R. and G.W.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data concerning Foundational Myth 4 is publicly available here: https://zenodo.org/records/14838263 (accessed on 4 September 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; De Vries, W.; De Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.; Steffen, W.; Rockström, J.; Lucht, W.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bala, G.; Von Bloh, W.; Feulner, G. Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadh2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planetary Boundaries Science (PBScience). Planetary Health Check 2025; Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK): Potsdam, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kallis, G. Degrowth; Agenda Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley, M.J.; Frieze, D. Using Emergence to Take Social Innovations to Scale; Two Loops Framework; The Berkana Institute: Provo, UT, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley, M.J. Who Do We Choose to Be? Facing Reality, Claiming Leadership, Restoring Sanity; Berrett-Koehler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness; The New Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M. Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World; Verso: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, S. There Is a Planet B: Implementing the Greatest Transformation in Human History; Climate Healers: Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; A/RES/70/1; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Beyond Cruelty Foundation. SDG #18: Zero Animal Exploitation. (Policy Proposal/Website). Available online: https://sdg18.org/ (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Rockström, J.; Thilsted, S.H.; Willett, W.C.; Gordon, L.J.; Herrero, M.; Hicks, C.C.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Rao, N.; Springmann, M.; Wright, E.C.; et al. The EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy, Sustainable and Just Food Systems. Lancet 2025, 406, 1625–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulé, M.; Noss, R. Rewilding and Biodiversity: Complementary Goals for Continental Conservation; Wild Earth: Gold Coast, Australia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Foreman, D. Rewilding North America: A Vision for Conservation in the 21st Century; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pettorelli, N.; Barlow, J.; Stephens, P.A.; Durant, S.M.; Connor, B.; Schulte to Bühne, H.; Sandom, C.J.; Wentworth, J.; du Toit, J.T. Making Rewilding Fit for Policy. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 55, 1114–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blythe, C.; Jepson, P. Rewilding: The Radical New Science of Ecological Recovery; Icon Books: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, D. The Myth of Human Supremacy; Seven Stories Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ostende, M.; Sorman, A.H. From separation to relation: The rights of nature vs. nature’s contribution to people. PLoS Clim. 2025, 4, e0000654. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, T. Prosperity Without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist; Chelsea Green: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sadhana Forest. A Forest in the Making (Website). Available online: https://sadhanaforest.org/ (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Houghton, J.T.; Miera Filho, L.G.; Lim, B.; Treanton, K.; Mamaty, I.; Bonduki, Y.; Griggs, D.J.; Callender, B.A. (Eds.) Revised 1996 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Bracknell, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, W.M., Jr. Race, Rights and the Thirteenth Amendment: Defining the Badges and Incidents of Slavery. UC Davis Law Rev. 2007, 40, 1311–1379. [Google Scholar]

- Munshi, S.A.; Sharma, A.; Shivaswamy, G.P. Decoding Lactose Intolerance: Growing Concerns in India’s Dairy-Rich Culture. Food Sci. Rep. 2024, 5, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- McGee, J.A. Understanding the Jevon’s Paradox. Environ. Sociol. 2015, 2, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabi, S.; Giagnocavo, C. Business models and strategies for the internalization of externalities in agri-food value chains. Agric. Econ. 2024, 12, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahmann, C.; Heyer, G. Measuring Context Change to Detect Statements Violating the Overton Window. In Proceedings of the 11th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2019), Viena, Austria, 17–19 September 2019; pp. 392–396. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment. Norway’s Climate Action Plan for 2021–2030; Meld. St. 13 (2020–2021) Report to the Storting (White Paper); Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment: Oslo, Norway, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.; Bustamante, M.; Ahammad, H.; Clark, H.; Dong, H.; Elsiddig, E.A.; Haberl, H.; Harper, R.; House, J.; Jafari, M.; et al. Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use (AFOLU). In Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Edenhofer, O., Pichs-Madruga, R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, S.O.; Abrantes, L.C.S.; Azevedo, F.M.; Morais, N.D.S.D.; Morais, D.D.C.; Goncalves, V.S.S.; Fontes, E.A.F.; Franceschini, S.D.C.C.; Priore, S.E. Food Insecurity and Micronutrient Deficiency in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, J.; Chang, S.S.E.; Agrawal, N. On seeing the self as a scarce resource: How time and money scarcity differentially shape consumers’ self-value and preferences. J. Consum. Psychol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedderburn-Bisshop, G. Deforestation—A call for consistent carbon accounting. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 111006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedderburn-Bisshop, G. Increased transparency in accounting conventions could benefit climate policy. Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 044008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, D.; Markusson, N. The co-evolution of technological promises, modeling, policies and climate change targets. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, C.D.; Hartle, J.C.; Garrett, R.D.; Offringa, L.C.; Wasserman, A.S. Maximizing the intersection of human health and the health of the environment with regard to the amount and type of protein produced and consumed in the United States. Nutr. Rev. 2019, 77, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P.J.; Broadley, M.R. Calcium in Plants. Ann. Bot. 2003, 92, 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostroff, S.; Golding, J. Codes for a Healthy Earth. Available online: https://www.codes.earth/ (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health and Economic Costs of Chronic Diseases; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021.

- Dudzich, V.; Dědeček, R. Exploring the limitations of GDP per capita as an indicator of economic development: A cross-country perspective. Rev. Econ. Perspect. 2022, 22, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnko, H.J.; Gwakisa, P.S.; Ngonyoka, A.; Estes, A. Climate change and variability perceptions and adaptations of pastoralists’ communities in the Maasai Steppe, Tanzania. J. Arid. Environ. 2021, 185, 104337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; (SRCCL); IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, S. Carbon Yoga: The Vegan Metamorphosis; Climate Healers Publication: Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 2018, 360, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rippe, J.M. The Academic Basis of Lifestyle Medicine. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2023, 18, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).