Abstract

Debates about the true purpose of education have increased globally in recent years, with climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic accelerating interest in the subject. It has become clear that education systems play a vital role not only in shaping the values, mindsets and ethical behaviours that we need for caring and responsible societies, but also in influencing our everyday interactions with the environment. To that end, wellbeing always concerns the triple nature of self, others and the natural world and there is increasing recognition of the need to move from a primary focus on personal happiness and attainment to a more balanced interest in the optimisation of human flourishing within the context of sustainable and regenerative futures. This article introduces the educational work of the Flourish Project, exploring the degree to which schools need to be understood as living systems and the way curricular frameworks, as they currently stand, may be inadvertently contributing to human languishing rather than flourishing. It explains the thinking behind the Flourish Model and describes the way in which the educational aspect of the Flourish Project hopes to contribute not only to the ongoing debate concerning the role of flourishing in education, but also to the growing global interest in the Inner Development Goals (IDGs) as skills and qualities that are vital for purposeful, sustainable, and productive lives.

1. Introduction

There can be no keener revelation of a society’s soul than the way in which it treats its children.—Nelson Mandela [1]

Thirteen percent of the world’s adult population are currently estimated to be clinically overweight or obese, which includes 38.2 million children under the age of five. In 2016, one in six Americans was prescribed psychiatric medication and, in the UK, one in six adults experience a common mental health problem, with one in five having considered taking their own life at some point [2,3,4]. According to the UK charity Young Minds, even before COVID-19 one in six children aged five to sixteen were identified as having a probable mental health problem in July 2021, a huge increase from one in nine in 2017. That is an average of five children in every classroom. In the 2018–2019 period, an astonishing 24% of 17-year-olds reported self-harming the previous year, and 7% reported self-harming with suicidal intent at some point in their lives [5]. A recent report on exams in the UK reported that children showed little variance in their levels of wellbeing during exam periods, but in its appendix revealed that:

- 68% of children were unhappy at school;

- 64% did not like themselves;

- 55% did not feel they have a number of good qualities (rising to 68% 90 days after the exam period);

- 53% did not think they can do things as well as other people;

- 58% thought they were not a person of value (rising to 67% over 90 days) [6]

Flourishing is when our inner needs are in a state of cohesive balance with the demands of the external world, enabling us to become aware of and focus on what most interests us and brings us pleasure, to hone, express and share our unique skills and capacities and to functionally optimise our lives—physically, psychologically, socially and spiritually [7,8,9,10]. It involves a strong sense of meaning and purpose, where our work and leisure activities make sense in the context of creative participation within the larger ecosystem. It is always a contextually dynamic process as we adapt and respond to external stimuli in the movement towards and process of integration and growth. This often involves us in periods of challenge and difficulty as we face, seek and overcome our conditioning, fears and limitations.

The positive dimensions of flourishing manifest as the following: physical health and vitality; mental health, positive relationships with others; emotional mastery; environmental mastery; autonomy; self-acceptance; contribution; personal growth; purpose in life; fulfilment of potential and happiness.

Adults with integrated levels of health, where a sustainable balance has been achieved between personal needs and social and environmental pressures, exhibit high levels of vitality and wellbeing. Adults with fragmented levels of health instead exhibit languishing, with low vitality and wellbeing. Some of their needs may be met, but often at the expense of other needs. Languishing is frequently experienced as emptiness and stagnation, often constituting lives of quiet despair. It involves little or no sense of cohesion in one’s life, and an eroded and compromised sense of meaning and purpose, where life seems pointless and of little or no value to the wider world. It is an indication that our wellbeing needs are not being sufficiently met. Languishing is often discussed as primarily consisting of poor mental health [11] but based on the definition of flourishing put forward above it is a systemic issue that indicates that we are unable to achieve the states of balance and integration that are necessary for us to grow and feel whole.

Any education is, in its forms and methods, an outgrowth of the needs of the society in which it exists.John Dewey [12]

This paper presents the first major contribution of the Flourish Project to the way in which schools might embed whole systems thinking into their wellbeing approaches. It explores schools as living systems within which everyone’s wellbeing matters, and that all human beings have inner and outer lives that need to be integrated for optimal functioning. It promotes the importance of school communities being active participants in the design process and will suggest that over and above personal accomplishment and attainment, effective learning should be about being able to live good and meaningful lives.

The objective of the first pilot studies is to:

- (a)

- Evaluate the use of the Flourish Model to support whole systems thinking;

- (b)

- Initiate whole school conversations about the conditions that nurture or inhibit human wellbeing/flourishing;

- (c)

- Actively engage schools in helping to shape and refine the wellbeing indicators;

- (d)

- Develop a practical and implementable digital resource for the initial pilot schools;

- (e)

- Initiate discussions around the way such a digital platform might then be further revised and structured for practical implementation in state schools at a global scale;

- (f)

- Explore the way the model could be used to promote the Inner Development Goals (IDGs);

- (g)

- Actively contribute to current global conversations on unitive thinking and planetary health.

The pilot studies are experimental and involve both qualitative and quantitative research, with original data collected through online surveys, participative webinars with the participating schools and datasets from the Nurture Digital Platform. The population involves those schools that have agreed to become early adopters of the pilot studies and that are members of the existing global client base of ORAH.com. The intention is for the results to then be actively shared and discussed with other expert groups that are working in the field, including the educational working groups of the Human Flourishing Programme at Harvard University.

2. The Role of Education in Flourishing

Education matters for people at all stages of life. But what is the purpose of education? This quintessential question must be asked before we can assess if our education systems are delivering on their promise. Should the goal of education be to develop human flourishing, or should it be to meet the demands of ‘homo economicus’?UNESCO, 2022

The need to shift focus in education away from personal attainment and towards flourishing is now being discussed by many major organisations. The OECD talks of students needing to ‘act with a sense of purpose, which guides them to flourish and thrive in society’ [13]. The Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues holds that ‘flourishing is the widely accepted goal of life’ [14]. Positive Psychology holds that ‘flourishing is the goal of education’ [15]. and The Church of England (CofE) states that ‘education is … at its heart, about human flourishing’ [16]. The Human Flourishing Program at Harvard University includes several working groups in its Flourishing Network focusing on education [17].

Influential advocates of theories on human happiness and flourishing include Amartya Sen [18,19], Richard Layard [20],Martin Seligman [21], Felicity Huppert [22], Harry Brighouse [23], Doret de Ruyter [24], Lynne Wolbert [25], Michael Reiss and John White [26], and Tyler J. VanderWeele [27,28,29].

Education is essential for flourishing, in that it contributes to the evolutionary growth process through the acquisition of the knowledge, skills, values, beliefs and worldviews necessary to survive in a complex world with others [30]. It facilitates the transmission of cultural heritage from one generation to the next and, when at its best, enables the compassionate deconstruction of what has gone before to serve the emergent needs of the future. At this time in human history, when we are facing climate change, a financial crisis and global destabilisation, education has never been more important. Education needs to adapt to the most pressing needs of any time; as John Dewey wrote in 1923, education ‘should never come to an end’ [31]—it should be continuously evolving in response to the needs of society and the planet.

What has so far been missing from the global dialogue, however, is the vital role of optimising the early conditions needed to optimise states of wellbeing, something that has recently been acknowledged by UNESCO, together with how to maintain and achieve the states of autonomous motivation or energetic flow that are prevalent in early childhood and indicative of human flourishing, yet are rarely examined and promoted within schooling systems. Flow is when our unique skills and capacities are stretched to meet the demands of the environment. Flow is discussed in more detail in Section 4. From a schooling perspective, flow is facilitated when students are able to seek out from the environment those elements that most attract or interest them and are given the time and space to follow these interests and to express their own knowledge, creativity and individuality.

UNESCO’s 2022 International Science and Evidence-based Education Assessment (ISEEA), which supports its recently published Futures of Education report [32] discusses the purpose of education and challenges the current state of imbalance, calling for the implementation of large-scale flourishing assessments in schools. The report states that

These findings clearly point to the current imbalance in the educational system—overemphasis on academic performance and insufficient focus on supporting student flourishing, with academic pressures often undermining student flourishing. Inclusion of large-scale regular flourishing assessments in schools, and their results being considered in evaluations of school provisions, may help bring flourishing to the central stage of educational policy.[33]

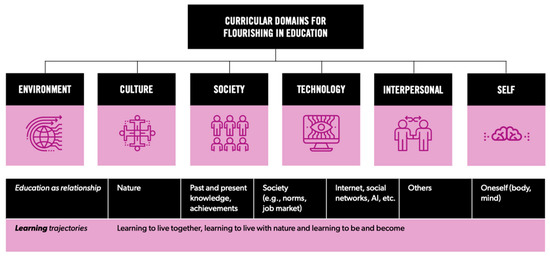

The report seeks to separate flourishing aims and manifestations into those that support the conditions of flourishing and those that provide the capacities for flourishing, stating that ‘The promotion of flourishing should be multi-scalar, and advance from micro to macro, that is, from the level of the individual student and teacher to that of policy, and vice versa’—with relationship as core to the whole process. It identifies a number of curricular domains that underpin the process (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

ISEEA Curricular Domains for Flourishing in Education.

The ISEEA suggests that the above framework might lend itself to considering various assessment practices that could be introduced to each of the curricular domains, from a schooling perspective to a policymaking perspective, and goes on to offer some specific suggestions:

Merely offering some illustrative examples, in the environment domain we would hope to see more sustainability practice; in the cultural curricular domain, more reading of literature, growing interest in arts; in the social domain, improved literacy, economic growth and higher rates of voting; in the technological domain, wiser consumption of news and reduced rates in consumption of unethical content; in the interpersonal domain, reduction in racism and growing inclusion; in the personal domain, higher levels of wellbeing, health, satisfaction and meaning in life.

The relationship between student and teacher is core to the process of flourishing, with the teacher providing a link between the student and the wider curricular domains. As Parker Palmer says in The Heart of a Teacher:

We need to open a new frontier in our exploration of good teaching: the inner landscape of a teacher’s life. To chart that landscape fully, three important paths must be taken–intellectual, emotional, and spiritual–and none can be ignored. Reduce teaching to intellect and it becomes a cold abstraction; reduce it to emotions and it becomes narcissistic; reduce it to the spiritual and it loses its anchor to the world. Intellect, emotion, and spirit depend on each other for wholeness. They are interwoven in the human self and in education at its best, and we need to interweave them in our pedagogical discourse as well.(1997) [34]

However, the relationships that students, teachers and schools have with parents is also essential. Several studies have shown that positive parent–child relationships are directly related to learning engagement and improved mental health [35,36,37,38].

3. A New Ecological Wellbeing Framework

Through revealing the interconnected nature of human development, evolution, behaviour and sustainability, the Flourish Model aims to provide an interdisciplinary road map explaining the relational foundations of human capacities and potential, and the way these promote and optimise sustainable wellbeing. It promotes the need for a new ‘ecology of wellbeing’ that better conveys the vital importance of protecting early development with our need to understand human flourishing as a dynamic and highly interconnected process, between the self, others, and the natural world.

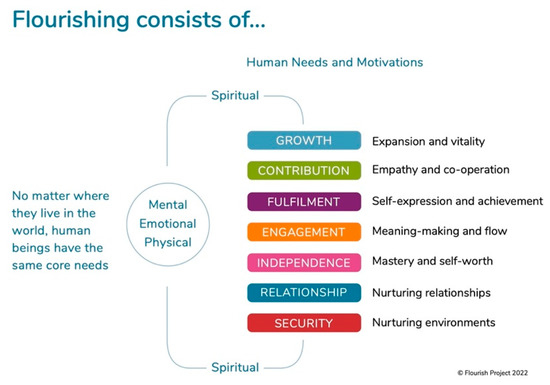

The Flourish Model was initially inspired by the Seven Levels of Consciousness Model put forward by leadership expert Richard Barrett [39] which was itself an extension of Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs [40]. The Model proposes that the dynamics of natural systems are reflected in seven core aspects to human flourishing which need to be fully acknowledged and incorporated for us to be supported in becoming the best version of ourselves. These are the energetic drivers of human motivations and development that invite us to actively engage with our environments and they are further shaped and defined by the unique experiences that we all have as individuals. They reflect our physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual needs as human beings.

The seven aspects are:

- Security;

- Relationship;

- Independence;

- Engagement;

- Fulfilment;

- Contribution;

- Growth.

Depending on our unique environmental experiences, these become the dispositions, beliefs, values and mindsets that create our individual maps of the world. The measures we have designed to reflect these seven aspects of wellbeing are summarised below (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Flourish Project—The Seven Core Human Needs/Motivations.

Figure 3.

Flourish Project—The Seven Aspects extended.

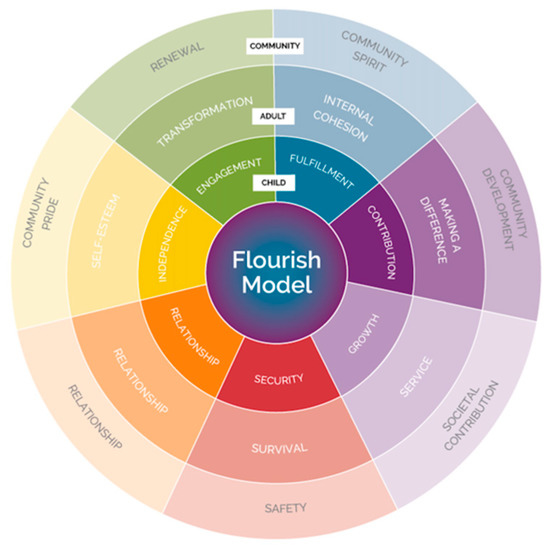

The Flourish Model proposes that we do not live in isolation, but always need to understand ourselves as unique elements within a wider social ecosystem (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Flourish Project—The Wellbeing Wheel.

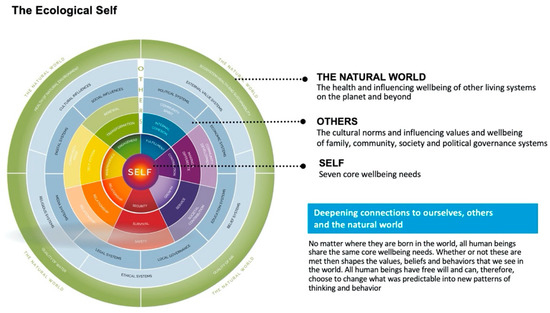

Not only that, but we are further embedded within the natural world and there is a relational ‘ecological self’ that needs to be recognised and better understood. The construct of the ecological self is illustrated below (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Flourish Project—The Ecological Self.

In this way, the model seeks to unite the work of the early psychologists and pedagogues (Montessori [41], Maslow [42] Bronfenbrenner [43] Deci [44] and Ryan [45] with the more cutting-edge thinking of contemporary figures such as Jack Shonkoff [46], Carol Dweck [47], James Heckman [48], Elinor Ostrom [49], David Sloan Wilson [50], Fritjof Capra [51,52], Peter Senge [53], Otto Scharmer [54], Gabor Mate [55] and Keri Facer [56]. It illustrates that the academic evidence itself needs to be understood and applied using a ‘whole systems’ perspective, and this includes the Indigenous call for ways of being in the world that are aligned with natural systems and processes and that honour states of messiness, difficulty and unpredictability as essential for human learning and growth [57,58].

The Model encourages more profound explorations into what causes and perpetuates states of languishing and diminished vitality rather than focusing only on what supports and measures states of attainment and positive functioning (Jahoda) [59]. It also moves the axis away from states of mental health to the more integrated and interesting dynamic of optimised values, dispositions, skills, capacities and potentialities which, when fully balanced, it suggests is experienced as ‘flow’ [60]. As such, it fully aligns with UNESCO’s own focus in aiming to show that individual wellbeing is always relational.

From an ecological perspective, it holds that we need to seek to balance skills and abilities with the cultivation of the kind of attitudes and values that we need to see in the world. In other words, we need a fully integrated approach that acknowledges that our own survival may depend on the decisions that we take at this time. There is a common acknowledgement that the old models of wellbeing, which focused on one aspect of the system, all too often at the expense of others, are no longer either valid or sustainable. There is also an acknowledgement that flourishing is a dynamic and lifelong process that incorporates the more transitory psychological state of happiness, but that, more fundamentally, involves personal struggle, difficulty and the overcoming of past obstacles, limitations, and fears. We are complex beings living in a complex world.

4. Flow

The input, throughput and output processes of living systems are always trying to achieve the state of energetic homeostasis or optimal functioning of energetic flow. They spontaneously include the emergence of new forms of order at points of instability. Continuous learning, adaptation and development are key characteristics of the behaviour of all living systems, as we try to optimise our own development within the context of the larger system. Creativity is fundamental to the process. As the system theorist Fritjof Capra says in his 2018 book The Hidden Connections [61]:

This spontaneous emergence of new order at critical points of instability, which is nowadays often referred to just as “emergence,” is the key characteristic of dynamic self-organization, and is in fact one of the hallmarks of life. It has been recognized as the underlying dynamic of development, of learning, and of evolution. In other words, creativity—the generation of new forms of order—is a key property of all living systems. Nature always reaches out into new territory to create novelty.

Perhaps the activity that we most associate with flow during childhood is play, but from a psychological point of view, work and play are not opposites, and what matters is the intense involvement of the participant in an experience that gives them both meaning and purpose [62]. This is the essence of intrinsic (rather than extrinsic) motivation. Play is so important to human beings because it allows us to generatively reach out into novelty without the risk of being overly judged by others as ‘failing’ or the need to achieve a specific externally imposed result.

Finding individual meaning and purpose in our lives is essential, but from a systems perspective, this has a collaborative aspect where personal maturation is linked to the needs of broader society. Natural systems always provide maximum freedom of their parts to invite in novelty, but also promote maximum coherence (health or vitality) of the whole. Structure is the springboard for creativity (both generative and adaptive) and leads to flow within the system.

In a flow state, the achievement of goals is no longer the only priority. Rather, the freedom from having to focus on any specific end result allows the individual to escape the confines of boredom or the concern about being judged and to fully enjoy the learning process. In this way, the experience itself becomes immensely fulfilling, but this does not necessarily equate with simple pleasure, for many flow activities are, to all intents and purposes, immensely complex, time-consuming and even frustrating. It is all about finding the balance between environmental challenge and personal capacities and each individual responds to this in their unique way. This is something that was of profound interest to the early pedagogue Maria Montessori, who saw that adult interventions were constantly interrupting the natural learning cycles of children [63].

We cannot know the consequences of suffocating a spontaneous action at the time when a child is just beginning to be active; perhaps we suffocate life itself.

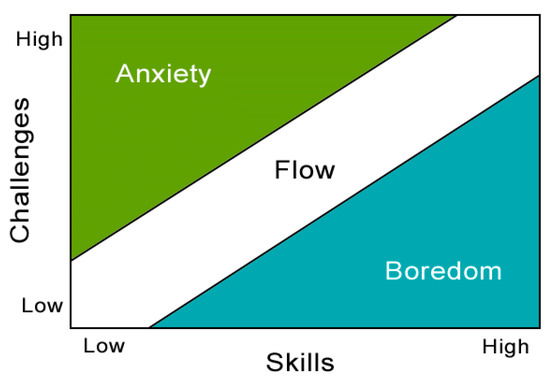

Later on, psychologist Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi [64] showed that flow states are achieved through balancing external environmental challenges with the optimisation of internal skills and capacities (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The Flow Channel (Csikszentmihalyi 1990, p. 74).

It is when we act freely, for the sake of the action itself rather than for ulterior motives, that we learn to become more than what we were. When we choose a goal and invest ourselves in it to the limits of concentration, whatever we do will be enjoyable. And once we have tasted this joy, we will redouble our efforts to taste it again. This is the way the self grows.

Csikszentmihalyi broke flow and what is required to achieve it down into the following characteristics [65]:

- Complete concentration on the task;

- Clarity of goals and rewards;

- Immediate feedback;

- Time dilation;

- The experience is intrinsically rewarding;

- Effortlessness and ease;

- There is a balance between challenge and skills, such that skills have to be stretched to meet the challenge;

- Actions and awareness are merged, losing self-conscious rumination;

- A feeling of control.

There is currently a growing interest in the neurobiology of flow [66] and the way we can achieve states of ‘peak performance’ [67]. There is also growing interest in ‘group flow’ and the power of collaboration to generate innovation. Examples include Keith Sawyer’s Group Genius [68] and Peter Senge and Otto Scharmer’s work on presencing and emergence [69].

As Steven Kotler, the founder of the Flow Research Collective, writes, Flow is more than an optimal state of consciousness—one where we feel our best and perform our best—it also appears to be the only practical answer to the question: What is the meaning of life? Flow is what makes life worth living [70,71].

From the perspective of the Flourish Project, this involves exploring the difference between optimising our functioning and performance as individuals and the need for us to understand the impact of our own decisions on the wellbeing and sustainability of the system as a whole. It also involves being curious about the difference between the states of flow needed to achieve the optimal individual functioning and performance ultimately associated with ‘self-actualization’, those that occur in coherent group situations, and the states of peak experience and ‘self-transcendence’ that lift us fully away from our individuated sense of self to being one with a larger unified field—something that Maslow was interested in towards the end of his life [72]:

Transcendence refers to the very highest and most inclusive or holistic levels of human consciousness, behaving and relating, as ends rather than means, to oneself, to significant others, to human beings in general, to other species, to nature, and to the cosmos.(Maslow, 1971, p. 269.)

Flow remains, however, a subject that is poorly explored in schools and an area that has considerable possibilities for future research.

5. Authenticity and Vulnerability

Flourishing is, therefore, all about achieving a right or ‘authentic’ relationship—with yourself, with others and the natural world. Authenticity and vulnerability (i.e., being able to openly share your own thoughts and emotions) is fundamental to this process and is essential for meaningful human interactions and experience. Vulnerability involves emotional exposure, opens us up to being seen through the eyes of others and is deeply connected to our sense of self-worth. Very early on in life we learn that our feelings of worth are tied up with external perceptions and value measurements relating to who we are, and that being authentic can therefore be dangerous. The dilemma is that we are always being pulled towards self-expression and wholeness, and for us to flourish we need to be supported in letting go of all the fears that may have been holding us back. Flourishing is therefore not about being perfect but is, instead, about being supremely human. The inner guide in each of us is always looking for opportunities to bring our minds, emotions and bodies into connection and wholeness with the dynamics of the natural world. There is a natural energy of integration that invites us to let go of our individual and conditioned selves and to unite with the emergent and dynamic patterns and principles of the larger system.

Evolutionary science shows us that there is more to life than psychological wellbeing. Individuals flourish when they are physically healthy and secure, have warm and trusting relationships, have a sense of personal agency, can engage positively with the environment, can creatively express themselves, feel a sense of purpose, belonging and contribution and can learn and grow throughout the lifespan [73]. In other words, we are dynamic cultural beings, and we need to constantly balance and harmonise our internal experiences through the quality of our relationship with others and the environments that we live within. This includes the development of self-awareness and the prosocial moral and ethical capacities that we need for a sustainable future.

The Flourish Model celebrates the contribution of the leading thinkers to our understanding of human wellbeing, but highlights the danger of an over-focus on the psychological health of the individual rather than the optimisation of all the physical, emotional, mental and spiritual aspects that combine to create more balanced states of functioning. This is something that is being explored by the Human Flourishing Program at Harvard University, whose measures of wellbeing currently include the following five domains: happiness and life satisfaction; mental and physical health; meaning and purpose; character and virtue, and close social relationships [74]. Wellness is never just about our individual functioning, but also includes our social and environmental contexts.

Numerous studies show that excessive focus on personal attainment or achievement without the balance of contributing to something bigger than ourselves produces lives that are materially impressive, but lack the deeper meaning and purpose that emotional connection to something beyond ourselves provides. As Helen Street writes in her 2018 book Contextual Wellbeing: Creating Positive Schools from the Inside Out [75]:

Well-being is not simply about individual expressions of thoughts, feelings and behaviours; it is not an isolated or solitary pursuit. It is just as much about the connections we form with others, the tasks we pursue and our wider sense of the world. Wellbeing concerns our ‘being well’ as social beings, not just human beings. It is about creating and reacting to a social context in a healthy and positive way. Ultimately lasting well-being and happiness have far less to do with any aspect of our individual functioning than we might like to think, and far more to do with the spaces between us.

We thrive when our lives make sense in terms of the whole, when we feel held, understood and valued by the communities within which we live and when we can express our own skills, abilities and understanding as we develop and grow.

6. Education and Sustainability

Outside of families and communities, education systems are the key influencers on the ways we learn to think about ourselves, others and the natural world. They inform us about what our cultures value the most and significantly shape our subsequent motivations and behaviours. They profoundly shape our sense of personal agency, worth and wellbeing and either promote or inhibit what we feel is possible in terms of personal aspiration.

The promotion of new and more ecosystemic models of education has tremendous potential to optimise personal, societal and planetary wellbeing, to better prepare children for the rapidly changing future of work and to distribute opportunities for agency more equitably. This can support the empowerment of young people to shape the future now, to enhance social mobility and to promote more participative, engaged and harmonious societies which pay closer attention to wellbeing beyond individualistic success. In this way, schooling and education systems would be understood as simply one element of the wider ecosystem of a lifelong journey, within which personal meaning and ongoing growth is acknowledged as essential for human and planetary wellbeing. They would represent a crucial element in promoting our need to live regeneratively and in right relationship for a sustainable world.

In 2021, the influential Dasgupta Review [76] (Box 1) called for the transformation of our institutions and systems—particularly finance and education—to enable such changes and sustain them for future generations, asserting that this should include increasing public and private ‘financial flows’ that enhanced natural assets and decreasing those that degraded nature.

Box 1. Dasgupta Review, The Economics of Biodiversity, 2021.

Although the sense of transcendence that Nature invokes may still exist everywhere, it has taken a severe beating in modern times…That need not have been. Correct economic reasoning is entangled with our values. Biodiversity does not only have instrumental value, it also has intrinsic worth—perhaps even moral worth. Each of these senses is enriched when we recognise that we are embedded in Nature. To detach Nature from economic reasoning is to imply that we consider ourselves to be external to Nature. The fault is not in economics; it lies in the way we have chosen to practise it.Dasgupta Review, 2021

Such new thinking aligns with the current interest in balancing the external UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with the Inner Development Goals (IDGs) [77] and suggests that, to become more aware, we need to explore both the inner and outer aspects of human societies. This involves understanding the world on two fundamental levels. First, understanding the world from the ‘inside-out’: the way our own backgrounds, experiences, values, thoughts and emotions influence our personal behaviour, activities and impact on the world. Second, understanding the world from ‘outside-in’: the way the external pressures and expectations of the systems that we live within (i.e., the quality of the natural environment, our families, communities, political and religious systems and cultures) influence our physical health, thoughts, emotions, values and behaviours. As Wilson-Strydom and Walker explore in a 2015 article, there are both personal and relational aspects that always need to be taken into account:

Flourishing “in” education requires consideration of the well-being and agency of students. Flourishing “through” education draws attention to the role of education in promoting well-being and flourishing beyond its walls by fostering a social and moral consciousness among students.(Wilson-Strydom, Merridy; Walker, Melanie, 2015) [78]

7. A Collaborative and Inclusive Approach to Assessment

As in inclusive approach, the initiative celebrates the rich diversity of contributions to the field of human wellbeing in the last two decades and has been developing a range of resources to support schools in adopting a ‘whole school’ way of thinking and to encourage prosociality. It further endorses the global call for the need to move away from extrinsic value and reward systems, based primarily on individual achievement and performance, to more intrinsic and autonomous forms of motivation that underpin deep learning and growth [79]. In addition, it endorses the findings of the UNESCO ISEE Assessment report in that:

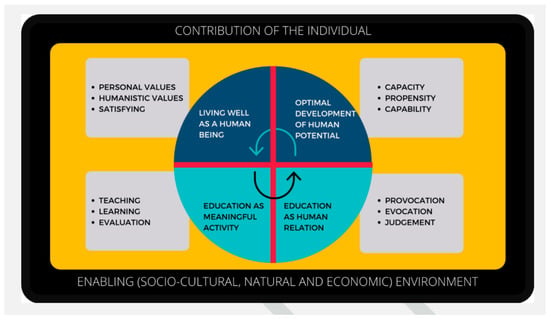

and which reveals flourishing as a multi-systemic process (Figure 7).The intertwined character of flourishing and education also shows that flourishing is a hybrid concept: the development of human potentials that make life a human life must inform education (the naturalistic quality of flourishing), but the worlds in which these potentials are fostered are different (cultural-dependent) and good education takes into account that children can develop different ways of living well related to their specific potentials and their ideas and preferences about how they want to live in the world (agent-relative).

Figure 7.

A visual representation of the relationship between flourishing and education, UNESCO ISEE Report, 2021.

The Flourish Model incorporates all seventeen of the SDGs. The Flourish Project initiative has worked with international partners to develop handbooks for Early Year and Primary/Elementary Settings. It is currently developing new resources that are aligned to the Inner Development Goals (IDGs) and is actively working with partners to develop a new ecological narrative that will cut across disciplines.

As well as providing a standalone framework, the model provides a way of mapping other approaches and forms of wellbeing assessment to support existing initiatives and to show the different areas of focus within an ecological context. This has proved to be particularly useful to endorse approaches that schools are already using, or to show where there might be excessive focus on certain aspects at the expense of others. Its core principles include:

- Human beings have physical, emotional, mental and spiritual needs that all need to be nurtured for optimal functioning.

- Wellbeing is relational, in that we are always influencing, and being influenced, by (i) the social world of others and (ii) the natural environment.

- Wellbeing is contextual, in that our individual wellbeing is always impacted by the authenticity and values of the communities in which we participate.

- Wellbeing is dynamic, in that our systems are always trying to self-optimise by balancing our inner and outer worlds.

8. Digital Wellbeing Platform

The Flourish Model is currently being beta-tested in the development of a new Digital Wellbeing Platform that aims to support schools in developing whole school thinking. The platform will provide a range of survey questions for everyone in the system (including students, leadership teams, teaching and administrative staff, parents and carers) and will offer the ability to customise wellbeing assessment templates so that measures can be precisely tailored to the contextual needs of the school, local authority, city or state. All the survey questions have been mapped across the Flourish Models Seven Levels of Wellbeing (Appendix A).

The initiative is supporting the development of collaborative research partnership arrangements with schools, to move the emphasis away from ‘tick-box wellbeing’ to the development of datasets that have real value and benefit over time. It is actively exploring how best to tackle the ethical implications of collecting longitudinal data.

The items, scales and survey questions being used in the development of the Orah Nurture Wellbeing Platform were created over a two-year period involving original expert contribution, an academic literature review of wellbeing indicators [80], an analysis of existing wellbeing frameworks currently being used worldwide [81], and a range of conversations with experts across disciplines. The intention is to further develop these in consultation with the participating schools.

9. The Pilot Process

The pilot process will be actively shaped through academic consultation, active research collaborations with participant schools and the key collaborators involvement in leading educational forums, including the Human Flourishing Program at Harvard, the Charter for Compassion, the Wellbeing Economy Alliance and the SDG Thought Leaders’ Circle.

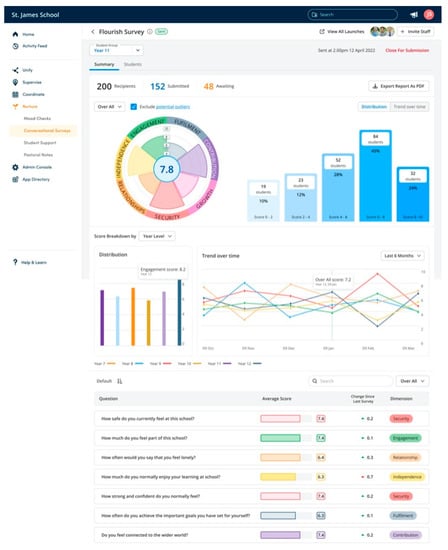

The platform is currently being beta-tested and developed though the partner’s existing relationship with some of the leading schools in the world, with the long-term aim of the final versions of the product being made fully accessible to state schools. The beta product currently includes Mood Maps, Survey Scales and Questions and a range of customisable templates and reports (Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10). The partnership is also exploring the development of a personal wellbeing app, for all participants within the school system, that will facilitate the confidential mapping of each person’s states of wellbeing over time in order to support their holistic wellbeing outside of the school system.

Figure 8.

Mood Map—Nurture Beta Web Platform.

Figure 9.

Flourish Survey Report—Nurture Beta Web Platform.

Figure 10.

Flourish Survey Options—Nurture Beta Web Platform.

One of the unique features offered through the platform is the degree of customisation available to participating schools who wish to further tailor the suggested sets of surveys to fit the contextual needs of their own settings. This is a potential innovation in the field, as most frameworks currently limit assessments to a predefined set of questions tied to the particular chosen version. There is recognition, however, that this will complicate the ability to conduct comparative assessments across settings and the project plans to work with school leadership teams to further explore this.

Feedback from the pilot studies will then be used to:

- Explore how best to initiate school-wide discussions on the Triple Nature of Wellbeing (self, others and the natural world);

- Show how everyone’s individual wellbeing matters to the whole;

- Provide valuable insights into the dynamic nature of states of wellbeing;

- Inform the selection, development and implementation of new targeted interventions;

- Facilitate the ongoing design of optimised tools and templates;

- Contribute to global discussions on the role of education in human flourishing;

- Debate the importance of ‘flow’ for optimal functioning;

- Create a collaborative research network of school leaders.

10. Conclusions and Pedagogical Implications

The emerging global interest in human flourishing is providing the field of education with an increasingly significant approach that warrants further multi-disciplinary research and development for stakeholders around the world. It encourages the move away from systems that limit human wellness and potential to those that recognise learning as fundamentally a relational process that involves more meaningful, ethical and relevant curriculum content. It provides policy-relevant evidence and recommendations that challenge narrow definitions of success and that promote learning as a lifelong process that is essential for the creation of peaceful and regenerative societies. It shows that we all have inner lives that need to be nurtured, that the wellbeing of parents, leadership teams and teaching staff is essential for flourishing schools, and that education systems across the world are now moving towards a transformative period of development where personal wellness is intricately woven into the wellness of others and the planet.

In this pivotal time of existential threat and evolutionary potential, it will be essential that our educational systems move beyond the current focus on the attainment of the individual to acknowledge that we are all embedded in larger systems and that the wellbeing of each element impacts on the whole. They will need to reflect a unitive understanding of what it means to be human, that schools are living systems with their own unique environmental contexts and needs, and that we have a mutual responsibility as stewards and co-creators of the future.

The project is currently entering its proof of concept/pilot development phase. Through its partnered educational activities, the Flourish Project hopes to (a) help open up this dialogue and (b) develop tools and resources to accelerate the process, with the ORAH.com digital wellbeing platform providing an early example.

Funding

This research is being funded by ORAH.com in partnership with the Flourish Project C.I.C.

Acknowledgments

Jonathan Beale was an academic consultant to the digital aspect of the project. Beale is currently a Research Affiliate at the Human Flourishing Program at Harvard University, where he co-leads the Program's Flourishing Network. He is a Peak Performance Coach for the Flow Research Collective, and an education and well-being research consultant. His previous positions include Academic Visitor at St Antony’s College, University of Oxford, Researcher-in-Residence at Eton College and Fellow in Philosophy at Harvard University.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has acted as an expert consultant to the development of the ORAH.com Digital Wellbeing Platform.

Appendix A. The Flourish Model’s Seven Domains of Wellbeing

The model helps to identify all the different aspects of wellbeing that need to be included in Whole System Assessments and shows the fears and limitations associated with each area. These will be further assessed and refined throughout the pilot period of development.

- Level 1: SECURITY—Physical Security and Health (PSH)

Includes shelter and support, health of the environment, nutrition, quality of sleep, movement and exercise, access to nature trusting the world, being in touch with your body, sensory awareness, self-knowledge and self-regulation.

Fears and limitations: the world is unpredictable and therefore dangerous/unsafe, I am not safe enough, I am not well enough, I do not trust things to be OK, I need to always be vigilant, I do not have enough, helplessness.

Optimised adult qualities: the ability to understand and structure the environment to maximise health and learning possibilities, the adoption of tools and techniques to optimise sensory awareness/being in touch with the body, the ability to understand the importance of spending time in nature, the ability to self-regulate, staying grounded in what is physically possible.

- Level 2: RELATIONSHIP—Relational Wellbeing (RW)

Includes connection, love, affection, nurturing, understanding, oracy, dignity, respect, family, peers, school, neighbourhood, self-image, love, affection, dignity, integrity, respect, fun, humour, trust, co-operation, listening, communication, empathy, respect for diversity.

Fears and limitations: judgement, bullying, abuse, abandonment, humiliation, I do not understand or trust other people, other people do not understand me, I am different, I do not fit in, I will get it wrong, I will be seen as stupid, I will be made to feel bad about myself, I am not good enough, people who are different from me are threatening/dangerous, I need to protect myself, I need to show others that I am strong/OK.

Optimised adult qualities: trusting self and others, being able to express and receive love and affection, being an effective communicator, expressing emotions appropriately, recognising emotions in self and others, understanding the causes and consequences of emotions in self and others, using authentic words and actions, the ability to listen to others, the ability to be open to different points of view, the ability to be non-judgemental, the ability to nurture relationships built upon inclusion, acceptance, cooperation and trust.

- Level 3: INDEPENDENCE—Resilience and Self-esteem (RSE)

Includes personal agency, self-direction, goal setting, overcoming challenge and difficulty, resilience, perseverance, self-regulation, empowerment, mastery, achievement, self-esteem self-confidence, curiosity, problem solving, risk taking, perseverance, overcoming challenges, learning from failure, courage, resilience, authenticity, self-worth, intrinsic motivation, self-development, self-efficacy, personal mastery, self-organisation, adaptability, self-direction.

Fears and limitations: I am not going to be able to understand what is needed, I cannot do it, I will fail, it will make me feel bad about myself, I will look stupid, I need to rely on others, there is no point trying, I am not clever enough, self-blame, shame.

Optimised adult qualities: the ability to self-organise, the ability to problem-solve and overcome challenges, adaptability, patience and perseverance, courage and authenticity, recognising the value of failure, acknowledging human imperfection, self-confidence.

- Level 4: ENGAGEMENT—Positive involvement and functioning (PIF)

Includes novelty, curiosity, challenge creativity, adaptation, innovation, entrepreneurship interest, concentration, study, playfulness, flow, creativity, innovation, entrepreneurship creative thinking, technology embracing, focus, planning, strategy, boundary spanning, efficacy building, playful leadership, curiosity, challenge, openness, accountability.

Fears and limitations: this has no relevance to my life, it is boring, I cannot see the point, other people can do this better than me, nothing interests or excites me about this.

Optimised adult qualities: playfulness, openness, humour, creative thinking, innovation and entrepreneurship, testing boundaries, leadership, accountability.

- Level 5: FULFILMENT: Positive Integration and Expression (PIE)

Includes personal achievement, individuality, self-expression, self-worth, individual meaning and purpose, success as optimising personal skills and capacities cohesion, self-expression, individuality, personal achievement, personal value authenticity, self-responsibility, achievement, excellence, peak performance, professionalism, presence, power, working to the edge of your skills and capacities.

Fears and Limitations: it is too risky, I will be seen and judged, I do not want to be blamed if it goes wrong, my ideas and activities have little or no value, I will fail.

Optimised adult qualities: individuality, integrity, self-expression, self-responsibility, professionalism, presence, power, flow, joy.

- Level 6: CONTRIBUTION—Social Connection and Self-Worth (SCW)

Sense of connection, participation, inclusion, equity, rights, having a voice, social sense of meaning and purpose, caring, responsibility, generosity, tolerance, inclusion, understanding where you fit, success as being able to contribute to the whole participation, inclusion, significance, community involvement, social media, kindness, generosity, humility, giving, service, self-responsibility, personal impact, global citizenship, making a difference, compassion, humour, cooperation, collaboration, team-development, team learning, community, interpersonal agility, systems thinking, celebrating diversity, cultural responsiveness, advocacy, diplomacy.

Fears and limitations: I have nothing of worth to contribute, no one cares about my thoughts, ideas and opinions, there is no point in trying to change the system, it is better to stay quiet/hidden, I have little or no value, I am invisible.

Optimised adult qualities: active cooperation, deep listening, systems thinking, generosity, the ability to model inclusion and respect for others, the ability to express care and compassion, the desire to achieve the best outcomes for all, the ability to foster creativity and innovation in others.

- Level 7: GROWTH—Meaning, Purpose and Vitality (MPV)

Self-reflection, life goals, faith, hope, love, compassion, future generations, clear goals, simplicity, vision, mission, continuous development, ecological stewardship, wisdom inner development, love of learning, celebrating unique skills and capacities, heart/soul fulfilment and expression, valuing challenge and difficulty, life meaning and purpose, understanding others, compassion, connection to nature, safeguarding the planet, success as becoming a caring global citizen.

Fears and limitations: my life has no meaning/purpose, it is hopeless, what is the point of it all, the unknown is dangerous, nothing will ever change, there is no point in hoping for anything better, there is no point in learning anything new, I do not care about the wellbeing of others.

Optimised adult qualities: a recognition of the joy of life-long learning, the ability to see the big picture, a personal sense of meaning and purpose, promoting the environmental conditions for mutual growth, demonstrating a commitment to life-long learning and positive ongoing change and transformation, the development of a sense of personal simplicity, contentment and joy, the ability to positively impact the lives of others, envisioning infinite potential/possibilities.

Appendix B. Nurture Wellbeing Platform—Beta Survey Questions

This initial set of optimised survey questions has been created by the Flourish Project for ORAH.com as part of the Nurture Wellbeing Platform concept development process. The intention is for the questions to be evaluated and refined/improved in collaboration with participating schools. The items, scales and questions being used were created over a two-year period involving original expert contribution, an academic literature review of wellbeing indicators, an analysis of existing wellbeing frameworks being used across the world and a range of expert conversations across disciplines.

| (A) Leadership |

| SECURITY: Physical Security and Health |

|

|

|

|

|

| RELATIONSHIP: Relational Wellbeing |

|

|

|

|

|

| INDEPENDENCE: Resilience and Self-Esteem |

|

|

|

|

|

| ENGAGEMENT: Positive Involvement and Functioning |

|

|

|

|

|

| FULFILMENT: Positive Integration and Expression |

|

|

|

|

|

| CONTRIBUTION: Social Connection and Self-Worth |

|

|

|

|

|

| GROWTH: Meaning, Purpose and Vitality |

|

|

|

|

|

| (B) Staff |

| SECURITY: Physical Security and Health |

|

|

|

|

|

| RELATIONSHIP: Relational Wellbeing |

|

|

|

|

|

| INDEPENDENCE: Resilience and Self-Esteem |

|

|

|

|

|

| ENGAGEMENT: Positive Involvement and Functioning |

|

|

|

|

|

| FULFILMENT: Positive Integration and Expression |

|

|

|

|

|

| CONTRIBUTION: Social connection and self-worth |

|

|

|

|

|

| GROWTH: Meaning, Purpose and Vitality |

|

|

|

|

|

| (C) Parents |

| SECURITY: Physical Security and Health |

|

|

|

|

|

| RELATIONSHIP: Relational Wellbeing |

|

|

|

|

|

| INDEPENDENCE: Resilience and Self-Esteem |

|

|

|

|

|

| ENGAGEMENT: Positive Involvement and Functioning |

|

|

|

|

|

| FULFILMENT: Positive Integration and Expression |

|

|

|

|

|

| CONTRIBUTION: Social Connection and Self-Worth |

|

|

|

| GROWTH: Meaning, Purpose and Vitality |

|

|

|

|

|

| (D) Students |

| SECURITY: Physical Security and Health: |

|

|

|

|

|

| RELATIONSHIP: Relational Wellbeing: |

|

|

|

|

|

| INDEPENDENCE: Resilience and Self-Esteem |

|

|

|

|

|

| ENGAGEMENT: Positive Involvement and Functioning |

|

|

|

|

|

| FULFILMENT: Positive Integration and Expression |

|

|

|

|

|

| CONTRIBUTION: Social Connection and Self-Worth |

|

|

|

|

|

| GROWTH: Meaning, Purpose and Vitality |

|

|

|

|

|

References

- Mandela, N. May speech given for launch of Children’s Fund in South Africa. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/1-in-6-americans-takes-a-psychiatric-drug/ (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Available online: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/statistics (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Young Minds, April 2022. Available online: www.youngminds.org.uk (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Ellyatt, W. A Response to Professor John Jerrim, National Tests and the Wellbeing of Primary School Pupils: New Evidence from the UK; Flourish Project: Cheltenham, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Piñeiro-Cossio, J.; Fernández-Martínez, A.; Nuviala, A.; Pérez-Ordás, R. Psychological Wellbeing in Physical Education and School Sports: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakellari, E.; Notara, V.; Lagiou, A.; Fatkulina, N.; Ivanova, S.; Korhonen, J.; Kregar Velikonja, N.; Lalova, V.; Laaksonen, C.; Petrova, G.; et al. Mental Health and Wellbeing at Schools: Health Promotion in Primary Schools with the Use of Digital Methods. Children 2021, 8, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Mavoa, S.; Zhao, J.; Raphael, D.; Smith, M. The Association between Green Space and Adolescents’ Mental Well-Being: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Gu, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, X. Association of Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Cognitive Function with Psychological Well-Being in School-Aged Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. The Mental Health Continuum: From Languishing to Flourishing in Life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2002, 43, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. Individual Psychology and Education. Philosopher 1934, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Future of Education and Skills: Education 2030; OECD Learning Compass 2030: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kristjánsson, K. Flourishing as the Aim of Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being; New York Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schools for Human Flourishing; The National Society (Church of England and Church in Wales) for the Promotion of Education: London, UK; SSAT (The Schools Network) Ltd.: London, UK; The Woodard Corporation: Rugeley, UK, 2016.

- Human Flourishing Program, Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA.

- Sen, A. Well-Being, Agency and Freedom: The Dewey Lectures 1984′. J. Philos. 1985, 82, 169221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Commodities and Capabilities; North-Holland: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Layard, R.; Ward, G. Can We Be Happier?: Evidence and Ethics (Pelican Books); Pelican Publishing Company: New Orleans, LA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realise your Potential for Lasting Fulfilment; Simon and Shuster: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Huppert, F. Challenges in defining and measuring well-being and their implications for policy. In Future Directions in Wellbeing: Education, Organizations and Policy; White, M.A., Slemp, G.J., Murray, A.S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brighouse, H. Education for a flourishing life. In Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education; Nabu Press: Charleston, SC, USA, 2008; Volume 107. [Google Scholar]

- De Ruyter, D. Ideals, Education and Happy Flourishing. Educ. Theory 2007, 57, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbert, L.S.; de Ruyter, D.J.; Schinkel, A. Formal criteria for the concept of human flourishing: The first step in defending flourishing as an ideal aim of education. Ethics Educ. 2015, 10, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, M.; White, J. An Aims-Based Curriculum: The Significance of Human Flourishing for Schools; IOE Press: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- VanderWeele, T.J. On the promotion of human flourishing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 8148–8156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, T.J.; McNeely, E.; Koh, H.K. Reimagining health: Flourishing. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2019, 321, 1667–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, T.J.; Kubzansky, L. Measuring Well-Being: Interdisciplinary Perspectives from the Social Sciences and the Humanities; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. SDG Resources for Educators—Quality Education; UNESCO, Paris, France. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/themes/education/sdgs/material/04 (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- Dewey, J. Social purposes in education. In Proceedings of the State Conference of Normal School Instructors, Bridgewater, MA, USA, September 1922. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Reimagining Our Futures Together—A New Social Contract for Education; UNESCO: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. International Science and Evidence Based Education (ISEE) Assessment Report; Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Education for Peace and Sustainable Development (MGIEP): Delhi, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Palker, P. The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Randolph, K.A.; Fraser, M.W.; Orthner, D.K. A strategy for assessing the impact of time-varying family risk factors on high school dropout. J. Fam. Issues 2006, 27, 933–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukie, I.K.; Skwarchuk, S.; LeFevre, J.; Sowinski, C. The role of child interests and collaborative parent–child interactions in fostering numeracy and literacy development in Canadian homes. Early Child. Educ. J. 2014, 42, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, M.; Barry, C.M.; De Grace, A.; Di Donato, T. How parents still help emerging adults get their homework done: The role of self-regulation as a mediator in the relation between parent–child relationship quality and school engagement. J. Adult Dev. 2016, 23, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Hong, J.S.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, D. Parent–child, teacher–student, and classmate relationships and bullying victimization among adolescents in China: Implications for school mental health. Sch. Ment. Health 2021, 13, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, R. A New Psychology of Human Wellbeing; Lulu Publishing: Morrisville, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montessori, M. The Absorbent Mind; Theosophical Publishing House: Tamil Nadu, India, 1939; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. Motivation and Personality; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, R. Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life’s domains. Can. Psychol. 2008, 49, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.; Deci, E. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shonkoff, J. The Lifelong Effects of Early Childhood Adversity and Toxic Stress. Am. Acad. Paediatr. 2012, 129, e232–e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, 1st ed.; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, J. The Economics of Inequality The Value of Early Childhood Education. Am. Educ. 2011, 35, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, O. Collective Action and the Evolution of Social Norms. J. Econ. Perspect. 2000, 14, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D. Prosocial: Using Evolutionary Science to Build Productive, Equitable, and Collaborative Groups; Context Press: Reno, NV, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F. Deep ecology: Educational possibilities for the twenty-first century. NAMTA J. 2003, 28, 157–193. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F.; Luisi, P. The Systems View of Life—A Unifying Vision; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.M.; Scharmer, C.O.; Jaworski, J.; Flowers, B.S. Presence: Exploring Profound Change in People, Organizations, and Society; Currency Press: Sydney, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Scharmer, C.O. Theory U: Learning from the Futures as It Emerges; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mate, G. the Realm of Hungry Ghosts; Vermilion: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Facer, K. Learning Futures, Education, Technology and Social Change; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cajete, G.; Little Bear, L. Native Science: Natural Laws of Interdependence; Clear Light Books: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- OCED. Meaningful reconciliation: Indigenous knowledges flourishing in B.C.’s K-12 education system for the betterment of all students. In Future of Education and Skills 2030: Conceptual Learning Framework, Proceedings of the 8th Informal Working Group (IWG) Meeting, Paris, France, 29–31 October 2018; Indigenous Working Group: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jahoda, M. Current Concepts of Positive Mental Health; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, J.A.; Shernoff, D.J.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Individual and situational factors related to the experience of flow in adolescence: A multilevel approach. In The Handbook of Methods in Positive Psychology; Ong, A.D., van Dulmen, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 542–558. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F. The Hidden Connections: A Science for Sustainable Living. Available online: http://beahrselp.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/Capra-Hidden-Connections-Ch-4.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2018).

- Whitebread, D. The Importance of Play; University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Montessori, M. The Secret of Childhood; Orient Longman Ltd: Patna, India, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. The Evolving Self: A Psychology for the Third Millennium; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 1993; p. 178. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Linden, M.; Tops, M.; Bakker, A. The Neuroscience of the Flow State: Involvement of the Locus Coeruleus Norepinephrine System. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 645498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.flowresearchcollective.com (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Sawyer, K. Group Genius; Abe Books: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.M.; Scharmer, C.O.; Jaworski, J.; Flowers, B.S. Presence, Human Purpose and the Field of the Future; Currency: Redfern, Sydney, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, S. The Rise of Superman: Decoding the Science of Ultimate Human Performance; New Harvest Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, S. The Art of the Impossible; Harper Wave: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A. The Farther Reaches of Human Nature; Arkana/Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, H.; Verden-Zoller, G. The Biology of Love; Opp, G., Peterander, F., Eds.; Focus Heilpadagogik, Ernst Reinhardt: Munchen, Germany; Basel, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://hfh.fas.harvard.edu/measuring-flourishing (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Street, H. Contextual Wellbeing, Creating Positive Schools from the Inside Out; Wise Solutions: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta, P. The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review; HM Treasury: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Inner Development Goals. Available online: www.innerdevelopmentgoals.org (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Wilson-Strydom, M.; Walker, M. A Capabilities-Friendly Conceptualisation of Flourishing in and through Education. J. Moral Educ. 2015, 44, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://rethinkingassessment.com (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Ellyatt, W. A History of Global Wellbeing Indicators; Flourish Project C.I.C.: Cheltenham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ellyatt, W. Global School Wellbeing Indicators Survey; Flourish Project C.I.C.: Cheltenham, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).