Abstract

Over the period in which the ancient Roman empire grew to its greatest extent, religion in the provinces underwent change. In this article, the author argues that glocalization as an explicit modern conceptual framework has added value to the analysis of religious material culture. First, the glocalization model is discussed in the context of a wider debate on the biased concept of Romanization. Second, a rationale is presented for interpreting Roman religious change with a glocalization perspective. Third, two concrete bodies of archaeological source material are re-interpreted within the glocalization framework: first the little studied rural sanctuary of Dhronecken near ancient Trier and second a particular form of religious gifts that appeared on an empire-wide scale as a ritual with respect to the salus, the well-being of the emperor. Based on the application of the glocalization framework to these sources, the author concludes that religious material culture in these cases can be seen as a process in which new forms of religious communication were created out of an interrelated and ongoing process of local and global cultural expressions.

1. Introduction

In the period between ca. 50 BC and AD 300, the Roman Empire gained control over a territory incorporating large parts of modern Europe, North Africa and East Asia. The people who lived in these newly conquered areas faced changes in their lives. The interpretation of how these people experienced religious change, based on material culture and ancient texts, is a difficult task and subject to change. The dominant “grand-narrative” implying that Graeco-Roman religion was in great decline in the first centuries AD has become subject to fierce deconstruction (Rives 2010). In addition, Rives shows that the indigenous traditions of the various peoples who made up the empire, and the way that these developed under Roman rule, has long been a neglected topic in research on religion in the Graeco-Roman world (Rives 2010). Now, Graeco-Roman religious tradition is attributed a more vigorous and creative role, and “the degree of Roman influences, strength of local traditions and the emergence of mixed forms have all been radically re-assessed” (North and Price 2011, pp. 2–3).

In a larger context, the interpretation of Roman cultural change in general is subject to fierce debate, as the ancient material does not speak for itself and historians and archaeologists ask and answer the questions, biased by a preset of conceptions of their own time (Finley 1987; Hingley 2005). In this article, the author investigates if glocalization is a valuable conceptual framework for the interpretation of religious change in the western part of the Roman Empire in the period of ca. 50 BC–AD 300. In short, glocalization involves the adaption of global expressions in local particularities and derives from theorizing ideas about globalization. As glocalization as a concept is increasingly applied across a variety of disciplines and fields—Roudometof (2016a) speaks of a glocal turn—this paper contributes to a wider debate on globalization and Roman archaeology in the first part, and applies the glocalization framework that has been set out in two case studies in the second part. First, glocalization theory is discussed in the context of a wider debate on the concept of Romanization, a deconstructed top-down framework from the late 19th century. The author argues that the glocalization framework is valuable because it uncovers a complex negotiation process behind Roman archeological material, in which seemingly Roman (i.e., global) cultural elements were differently adopted and adapted in various local contexts. Second, the author sets forth how Roman religion in its ancient context can be understood, and how religious change can be interpreted within a glocalization framework. It is argued that religious change on a local scale was a process in which new forms of religious communication were created out of an interrelated and ongoing process of local and global religious expressions. Third, two concrete bodies of archaeological source material are studied as case studies: first the rural sanctuary of Dhronecken near ancient Trier and second a particular form of religious gifts that appeared on an empire-wide scale as a ritual related to the salus, the well-being of the emperor. In doing so, this paper adds to the continuing theoretical debate on Romanization, the expanding interdisciplinary research on glocal religions, and provides new insights into the understanding of two religious types of material culture.

2. Beyond the Romanization Paradigm? Glocalization and the Roman World

“The extent to which conquest transformed the lives of the majority of the population is a contentious area of debate” (Hingley 2005, p. 115). This summarization by Hingley touches upon the fundamental problem of scholars studying Roman material culture and cultural interaction. Several scholars successfully demonstrated that an imperialistic top-down perspective became dominant from the late 19th century onwards, until it has been the subject of fierce deconstruction in the late 20th century inspired by postcolonial theories (e.g., Freeman 1997, pp. 27–50; Hingley 2005, pp. 1–48; Mattingly 2011, pp. 203–45). In reaction, several new frameworks have been proposed and discussed, which has led to an increasingly self-reflective, but highly fragmented research field (Pitts and Versluys 2015). While these frameworks often focused on bottom-up processes, some scholars have opposed that these postcolonial perspectives paradoxically maintain the Roman-Native dichotomy (Versluys 2014; Pitts and Versluys 2015; Gardner 2013; Woolf 1997). Another recent approach, that of globalization theory, aims to get beyond the Romanization paradigm (Versluys 2014; Pitts and Versluys 2015; Gardner 2013).

Globalization theory recently developed to describe the awareness of a process of growing interconnectivity, connecting different localities and making them more interdependent. Globalization has numerous meanings in different contexts, and is used to describe processes of a changing, globalizing world, in the spheres of culture, gender, ecology, capitalism, inequality, power, development, identity and population (Nederveen Pieterse 2009). I will focus on the area of cultural globalization, following Pitts who argues that globalization has high potential in the study of cultural change in antiquity (Pitts 2012). I argue it is a misunderstanding to interpret globalization as leading to cultural unity, where local places become increasingly interconnected with each other that one dominant culture will fade out the local cultures eventually (Appadurai 1996; Featherstone 1995). Rather, there is an inherent paradox in globalization, namely that processes of increasing homogenization and the incorporation of objects and ideas from a “global culture” ultimately involve transformations of these objects and ideas that always reassert self-identity at a local level (Hodos 2010). Robertson (1994, 1995) shows that glocalization is a twofold process involving the interpretation of the universalization of particularism and the particularization of universalism, the so-called paradox of globalization or the local-global nexus. Therefore, Robertson (1992, 1994, 1995) argues that the concept of glocalization better expresses the way globalization actually operates, as he explains that local and global culture are not two opposing forces, but they are interdependent and enable each other. In contrast, Roudometof (2016a, 2016b) argues, in his clear illustration of current theoretical interpretations of glocalization, for seeing glocalization as an analytically autonomous concept. It holds that glocalization should be seen as a process in which the agency of the local and the global is respected, leading to a multitude of glocalities. Roudometof (2016b, p. 399) defines glocality as “experiencing the global locally or through local lenses.” Therefore, I use the term glocalization to point towards the glocal in terms of processes of adopting and adapting globalization though the local.

Critique has been raised to apply globalization to the ancient Roman world, addressing the anachronistic approach (Dench 2005), the argument that the Roman world was not a global empire (Naerebout 2006–2007; Greene 2008), and that this framework offers no new insights or is even a mere fashionable substitute buzz-word for Romanization (Mattingly 2004). Gardner (2013) questions whether globalization might even serves to legitimize current inequalities, as it may be used as a gloss for neo-colonialism.

However, the glocalization framework fits into a general recent trend in archaeology where several justified globalization approaches have been made (e.g., Hodos 2017), as well as in the particular field of Roman archaeology (e.g., Pitts and Versluys 2015; Versluys 2014; Haeussler 2013; Hingley 2005; Hitchner 2008; Pitts 2008). Woolf (1994, 1995, 1997, 2005) already argued that it is not helpful to approach cultural contact in the Roman world by holding up the dichotomy of natives versus Romans. On the question as to why globalization can offer a solution seeking a way forward beyond Romanization, Versluys (2014) makes a strong case by arguing for instance that the Roman world can be seen as one oikumene which is all about increased connectivity between localities culturally and socially interacting within the same (global) group. Further perspectives and opportunities, including a coherent rationale for globalization theory in Roman archaeology and history are further set out in Pitts and Versluys (2015). Gardner (2013) too suggests that it is able to both study empire-wide phenomena and local experiences. In addition, several scholars already successfully used the glocalization framework in their work. For instance, Witcher (2000) shows that both earlier described approaches (top-down ‘Romanization’ and localized perspectives) made interesting advances, but are working at either end of a continuum. He concludes that "globalization offers the potential to work between these scales and to offer more rounded approaches to the mechanisms of Roman imperialism. Both the modern and ancient worlds involve overlapping scales of identity—global, national, regional, and local. The key is to locate these multiple identities in relation one another" (Witcher 2000, pp. 220–21). Along similar lines, Pitts (2008) argues that this framework adds more sophistication to the understanding of the homogenizing supply of pottery vessels in Roman Britain, as it was shaped by the integration of both local and global cultural elements.

Another justification for applying a glocalization framework to the Roman world is explicitly or implicitly made by scholars who have shown processes of globalization—in the form of increased connectivity—being active in the ancient Roman society (cf. Horden and Purcell 2000; Versluys 2014; Pitts and Versluys 2015; Hodos 2014). For example, Woolf argues that there was a relative short period of rapid cultural change, a formative period as he calls it, that went through the whole empire and coincided with the rule of Augustus (Woolf 1998). This wider process of socio-political and cultural change is not depended on the time of a region being conquered by Romans, but rather that this formative period took off on an empire-wide scale from roughly the transformation period between the ‘Roman Republic’ and the ‘Roman Empire’ (Keay and Terrenato 2001; Woolf 1995). It may seem clear to conclude that it was not the matter how long a region was conquered before change was visible, but rather in this specific period of time empire-wide change can be seen (Woolf 1998). In addition, the Roman elite themselves noticed that in this formative period around the time of Augustus there were some significant political and cultural changes occurring in the Roman empire, as can be seen in the writings of Dionysius of Halicarnassus (de Oratoribus Veteribus 3) and Strabo (Γεωγραφικά 6.4.3.) as shown by Woolf (2005, pp. 117–18). It seems clear that from this period onwards we can increasingly speak of an imperial structure of a formalized system of rule and government, census, and taxation over conquered territories. As Woolf points out: “the horizons of the Roman world had changed. Within those horizons the provinces were more numerous, were managed with more uniform systems, and were more securely held. With hindsight it seems a watershed had been passed: Rome had moved from greedy and unstable conquest state to tributary empire” (Woolf 2005, p. 117). Besides the fact that the political change brought about an increasing Roman imperial administration, a rapid spread and adaption of objects, practices, monuments characterized as Roman culture is also visible (Noreña 2011). Noreña (2011) argues for not seeing this as the expansion of one dominant culture at the expense of other local cultures, but as the emergence of a new, highly differentiated social formation of culture that was differently constructed on the basis of local and global power relations and hierarchy. This dominant culture was widely recognized as Roman, as it was closely connected to citizenship, and it evolved around shared notions of Roman identity in which habits of dress, speech, manners and conducts became more important than ethnical descent (Woolf 2005). Gardner (2013) argues that glocalization is able to analyze how transformation in the speed and reach of communication, movements of goods and people, information, and identities occurred differently in various places in the Roman empire, creating new forms of local identities.

3. Roman Religion as a Cultural Communication System

Before I can turn to the application of the glocalization framework on two religious archaeological datasets, it is necessary to briefly describe how religion in the ancient Roman world can be understood, and explain how Roman religion and its material culture can be seen as a cultural communication system. In his work on religion in the Roman empire, Rives (2000) explicates that Roman religion was closely tied to issues of culture, identity, and power. “Religion is very closely bound up with the way a person views the world and his or her own place within it; both shapes and reflects the system of values according to which a person lives his or her life” (Rives 2000, p. 245). Rives is inspired by the works of Clifford Geertz ([1973] 1993), who makes a case throughout his work for studying the religion of groups of people, societies and communities, rather than individuals, because even individual religious experience is part of a larger group (e.g., family, tribe, nation). For Geertz, culture is a system of meanings embodied in symbols, a communication system that serves as framework for individuals and social groups to understand reality, the world, and as a guidance for their behavior (Geertz [1973] 1993). Geertz defines religion fully as “a system of symbols which acts to establish powerful, pervasive and long-lasting moods and motivations in men by formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and clothing these conceptions with such an aura of factuality that the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic” (Geertz [1973] 1993, p. 90). Thus, in his understanding, religion is an instance of culture (Segal 2003). Religious symbols as part of such a cultural system serve a particular function, as they convey a direct connection between our worldview and ethos; how we perceive the world and how we live according to that view (Geertz [1973] 1993; Segal 2003).

Here we come to the point of explaining why this theory by Geertz is still relevant (cf. Schilbrack 2005), and is particularly useful in the context of Roman religion. Geertz' basic assumption rests upon the notion that sociologists and anthropologists need to study and interpret meanings people express through culture and religion, rather than explaining the cause of cultural and religious expressions (Segal 2003). Thus, it makes the study of religious material possible by interpreting how people used religious material in everyday life in a set of customs, traditions and rituals to shape their understanding of the world, rather than focusing on what people actually believed and questioning their theological views on religious truth.

Thus, in a period of rapid change due to globalization, the way in which people construct religious meanings can show us how their (glocalized) worldview changed (Robertson and Garrett 1991). Roudometof (2005) argues that religion and language in particular are relevant indicators in which local communities faced with global pressures will re-evaluate their support and attachment to local culture. In a society faced with globalization pressures, an increasing awareness of local differences and attitudes toward that difference is increasingly visible (Roudometof 2005).

Now, how are these ideas related to Roman religion? The similarities will be clear if we understand Roman religion in the definition by Rives that I would like to adhere to, as “a conception of, reverence for, and desire to please or live in harmony with some superhuman force, as expressed through specific beliefs, principles and actions” (Rives 2007, p. 4). However, the term Roman religion is a scholarly construct that is itself subject of extensive discussion; it is debated if there even was such a conceptual understanding of religion in the Roman world (Ando 2007, 2008). Therefore, it is necessary to briefly look at how Romans themselves perceived religion.

Turning to the ancient Roman works by Cicero (De Deorum Natura 2.28) (Cicero 1933), it is helpful to understand the difference between the concepts pietas and religio. “It is our duty to revere and worship these gods under the names which custom has bestowed upon them. But the best and also the purest, highest and most pious (pietas) way of worshipping the gods (cultus deorum) is ever to venerate them with purity, sincerity and innocence both of thought and of speech. For religion (religio) has been distinguished from superstition (superstitio) not only by philosophers but by our ancestors” (Cicero 1933). Pietas wrongly carries the Christian notion of piety, but in the Roman world it meant something like loyalty to the gods in behavior (Belayche 2007). The Latin concept of religio does not equal our concept of religion as a religious system, but rather, religio as Roman concept means a conviction that there is an asymmetrical reciprocal-relationship between the gods and humans (Ando 2003). Cicero also contrasts religio with superstitio, the persuasion of the contractual relationship between gods and humans (religio) versus the belief in mystical power beyond the gods, not simply a mere superstition but more a dread of the supernatural and anxious credulity (superstitio). In this classification of the right religious attitude, Cicero uses the concept of cultus deorum, which is closer to our sense of religion, as a system to “have the proper regard to the gods” (Ando 2003). As Rives shows, the term cultus derives from colere, which means to tend to, to look after, and in this context to make the object of religious devotion (Rives 2007). Therefore, though I will continue to speak of Roman religion as this is common practice, we need not only keep in mind the considerations from above about ancient terminology, but also continue to realize that Roman religion was not a static concept, but was rather constantly developing and dynamically changing over time (Beard et al. 1998).

In another fragment of a speech written by Cicero (On the Response of the Haruspices 19), he claims that the Romans outdo all other people in their pietas and religio and taking care of the gods, who govern and manage all things (Cicero 1891). Furthermore, in the first half of the quote he states that the Roman empire was only achieved and preserved by the divine authority. Therefore, he sees taking the proper care of the gods as a main reason for the military and political success of all the Romans. To some extent, this part of Cicero’s speech shows that there was at least some consensus in how Roman religion was perceived by Cicero and the late Republican Roman elite (Beard et al. 1998). Namely, this fragment shows that cultivating the gods to maintain the pax deorum (peace of the gods) is one of the fundaments of Roman religion. In addition, as these religious statements were done in the context of a strong political speech against Clodius, a political rival of Cicero, it makes clear that the political and religious spheres were inextricably connected in the ancient Roman world. All in all, it is often regarded that everything in the Roman world was dependent on the reciprocal relationship with the gods. In fact, the nature of Roman religion was founded upon an empiricist epistemology, as Ando (2003) argues, which means that religious cults addressed problems in the here and now; the effectiveness of rituals, in short success or failure, determined whether they were repeated, modified, or abandoned.

It is here that Roman religion shows a close resemblance with Geertz’s conception of religion seen as a cultural communication system. Other scholars argued along similar lines, as for example Van Andringa (2011) views ancient religious systems as human and historical constructs, continuously changing as ancient societies who produced them continuously evolved according to changing circumstances. In particular, at the time when the Roman world became increasingly interconnected as illustrated above, cult and religion played a particular role in processes of redefining ones place in a changing world order, and one’s own place in this new order (Stek 2009; cf. Roudometof 2005). As Derks (1995, p. 111) also put it: “One of the most suitable fields of study for examining the integration of native societies in the wider context of the Roman state is their religion. Nowhere is the self-definition of a group or of an individual more clearly perceptible than in their rituals.”

Now, I would like to connect the previous points about interpreting religion as cultural communication system and the nature of Roman religion. Rüpke (2009, 2011), in parallel with Rives and Geertz, argues that if we interpret religion as communicative system, it offers a framework to analyze religious material expressions as inscriptions, images and architecture. He explains that Roman religion functioned through vows and dedications to maintain good relations with the gods. These vows and dedications are real performative deeds, first and foremost expressed in language (i.e., reality), just like saying thank you is not just a token of gratitude, but also a real performative deed (Rüpke 2009). In making vows, normally one asked a certain help or gift from a god and promised something in return. When human deeds had a positive outcome, the recipient gave the particular fulfillment promised to a god in the vow, that forms the final action part of the vow (Rüpke 2009; cf. Derks 1995). This fulfillment could be a votive of all kinds of material, but for example temples were usually vowed in this manner too. Vows could also be accompanied by an inscription as witness of this transaction (usually we only find these written records), and sometimes the written record became the actual dedication itself (Bodel 2009). As Rüpke shows, this form of ritual communication with the gods was not always accompanied with material, but in time this process of constructing a religious infrastructure of communication became more materialized and an internal part of Graeco-Roman religion (Rüpke 2009).

Therefore, religious material culture like dedicatory inscriptions, statuettes of various material, temples and other votive objects can be interpreted as materialized and monumentalized forms of communicating with the gods. These are the material remainders of what Rüpke defines as the ‘media’ of symbolic religious communication, but we have to realize that these objects were once part of acts and rituals of religious communication, loaded with intentions and meanings (Bodel 2009; Rüpke 2011). In a sense, the focus on religious material culture and in particular its agency and various contexts presented here is in line with the point made by Versluys (2014, p. 17) of seeing “material culture as an active agent in its relationship with people, rather than simply a representation of (cultural) meaning (alone).”

Religious communication took place at different times, places and occasions. As the primary goal of religious communication was to maintain a healthy and beneficial relationship with the gods, primary recipients were the gods. In addition, religious communication also began to play a role at the level of social competition, by showing other humans how (well) one was able to communicate with the gods, and one's capacity to afford expensive votive gifts (Bodel 2009). Recording these offers, often accompanied with the names of the dedicants, not only served the goal that the gods would recognize the gifts, but also that other peers could recognize them, as they served a second communicative purpose of social competition and status demarcation. All in all, Rüpke (2010, p. 204) reasonably summarize that “by its use of inscriptions, images, and architecture, religion became one of the most important media of public communication.”

Before turning to the case studies, there is one more problem to touch upon. If an archaeologist finds a religious (and seemingly Roman) object, it is hard to signify the adoption of Roman religious attitudes therewith. Furthermore, there is little that scholars can say with certainly about indigenous pre-Roman religions. Still, the artefacts of religious material culture (votives, inscriptions, altars, temples and other monuments for instance) that frequently began to appear in the Roman provinces after conquest could be used to reconstruct religious glocalization. A discussion of the ancient concept of interpretatio Romana can be illustrative here. It is a concept that is used in studies of ancient religion to refer to the identification of foreign gods with Roman gods. In Latin literature, it is used only once by Tacitus (Germania 43.4), commenting on the Naharvali tribe that, according to interpretatio Romana, commemorated Castor and Pollux in a prehistoric ritual grove with pre-existing non-Roman rituals (Ando 2008, p. 44). Ando (2008) points to the unreflective use of this fragment by scholars in their studies on Roman provincial practice, where the material culture for syncretism between ‘Roman and Native’ gods is more abundant. He rightly argues that this passage, in its Roman context, shows that interpretatio Romana was much more an ongoing, dynamic process of translation and cross-cultural understanding; not in time and place, but from time to time and place to place (Ando 2008).

In the same way, interpreting votive inscriptions to gods with double names, one local and one Roman such as for instance Lenus-Mars, remains problematic. Derks (1998) argues that this label of native-Roman will “hold the Roman authorities responsible for the associations, whether or not intentionally”, and rather argues for seeing these associations in essence as products of local interpretations. Webster (1995), in contrast, points to the problem that interpretatio Romana was not simply a mutual recognition of similar gods, as the unequal power relation in this syncretizing process should not be under-emphasized. This implies that the Roman conquerors somehow implicitly or explicitly forced their religious communicational framework upon locals in a top-down way, because of the unequal power discourse. Webster further argues that “foreign gods were not simply viewed in terms of the Roman pantheon—they were converted to it by force” (Webster 1995, p. 160).

However, the combination of local and Roman gods as native-Roman religion (or as Gallo-Roman for the province of Gaul) does not work to enhance our conceptual understanding of religion in the Roman Empire. Van Andringa (2011, p. 133) illustrates this point by concluding that “Lenus-Mars is not a Gallic god, nor is he an indigenous god, any more he is Roman or Gallo-Roman.” Versluys (2015) similarly states that thinking about Isis as ‘Egyptian’ goddess in ‘Greek’ and ‘Roman’ contexts makes no sense, as this is an example of a Hellenistic, Mediterranean innovation in which all ‘players’ were involved in creating something new. Here is where the glocalization model offers perspective, since it is able to study the described religious material not just as solely bottom-up or top-down processes. The material culture shares characteristics of a global/Roman context, which makes it trans-locally recognizable, but it is locally different.

Van Andringa (2002, 2007) argues that during the socio-political transformation in the western provinces of the Roman empire, the processes of incorporating local communities into a larger territorial empire, alongside urbanization, led to a religious transformation. A crucial point in this religious transformation was that these new local communities now had a twin-fold interest in the well-being of their own community and their gods, and the empire as a whole and their gods, of which they now formed a part. Van Andringa (2007, 2011) sees this religious change as the creation of a whole new religious language. He argues against visions of Roman and native religion as coexisting, borrowing from each other, fusing or undergoing hybridization, because this implies that both religious cultures were static non-changing entities before Roman conquest, and because they are based on syncretized images isolated from their archaeological and historical context. Rather, these new local civic communities were established in a new global order within the power of Rome and its empire, and therefore the future of provincial communicates was closely connected to that of the state of Rome (Van Andringa 2002). Religious communication served the goal of enabling local communities to express their understanding of their place in a global context and in relation with other local communities (Van Andringa 2007).

The processes Van Andringa describes are in perfect harmony with the implications of the glocalization framework. Local communities were faced with global (i.e., Roman) power and culture. To come to terms with this changing world and their own place in it, new communities were created, which established new religious expressions in which both local and global interests were combined. I agree with Van Andringa in that this caused a new and common (i.e., global) religious language. These developments were both influenced by an interconnected process of top-down and bottom-up negotiation; firstly locally by local communities creating a new religious system of gods and cults that reflected their new status. Secondly in a top-down manner, as, for example, Roman soldiers and governors present in the provinces preferred to worship local gods, but did this in a Roman manner, thereby thinking globally but acting locally and influencing local communities too (cf. Derks 2002).

4. Case Study 1: Rural Sanctuary at Dhronecken

Now, as the theoretical framework of glocalization is explicitly discussed in the context of Roman religious change, I will apply it to the religious archaeological material of two case studies. In line with Versluys (2014), it seems important to me to study the material culture in its own right and various contexts to discover the various functions these objects had. New insights on these archaeological data can be provided by incorporating both the local and the global context of the material culture. The first case study deals with the understudied material of a rural sanctuary of Dhronecken in modern Germany, while the second case study involves the material used in a religious ritual performed in the whole Roman empire.

The rural sanctuary of Dhronecken belonged to the civitas Treverorum, a region that was populated by the tribe of the Treveri with an urban center that became known as Augusta Treverorum (modern Trier).1 In its historical context, the civitas Treverorum became steadily under Roman control from the conquests of Julius Caesar (Bellum Gallicum 3.11; 4.3; 4.10; 4.6; 6.32) onwards (Caesar 1869). After the Treverans played various roles during the Gallic wars, the Treveran region ultimately became part of the Roman province Belgica around the late first century BC and early first century AD, and from this period onwards the significance of the region and Augusta Treverorum grew, as it became the capital at this point. According to Woolf (1998), the Treveri were one of the local tribes that readily adapted Roman cultural influences, as he argues they underwent a significant cultural change after the Roman conquest. This is based on the large amount of archaeological material that has been found and can be dated to this period, and this rural sanctuary is just one of many examples.

4.1. Archaeological and Spatial Context

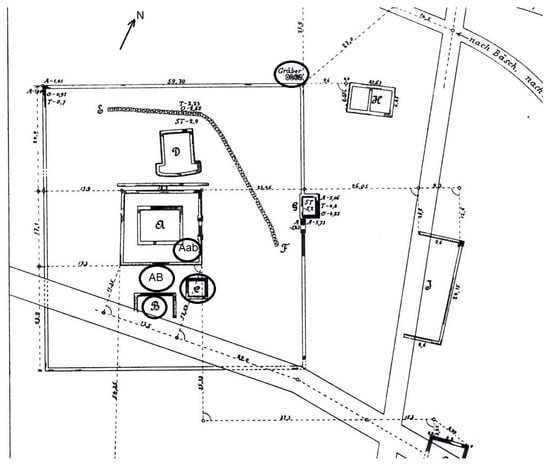

During road constructions in 1899, the precinct of 65 × 60 m2 and its directly adjacent buildings were discovered and excavated by archaeologist Hettner (1901) as can be seen in Figure 1. According to Hettner, cremation graves 1 and 2 in the northern corner outside and against the precinct wall can be dated to the first half of the first century AD, based on bone material, coal and votive gifts. Hettner thinks it is likely that the other two adjacent graves belong to approximately the same period. Although it is not clear whether Dhronecken was a newly created sanctuary in this time or built upon a pre-Roman cult place, it is certain that from the first century AD onwards Roman religious materials were used in this cult place.

Figure 1.

Details of the excavation map of Dhronecken, by Hettner (1901, p. XXII, 3a). Highlights and finding place indicators added by the author.

There are four main find places of votive material, as Hettner categorized them (Figure 1). First, there is finding place Aab in the eastern corner just below the entrance of the temple (building A), which lies in the center of the precinct. Unfortunately, due to a lack of manpower, only a small fragment of temple A was excavated. In addition, because Hettner could not distinguish different stratigraphical sections, we do not know anything about the development of the temple and the possibility of several building phases. In finding place Aab, mostly weapons, fibulae, mirrors, lead discs (bleischeiben), bronze fragments, shards and glass objects and coins were found (Hettner 1901, pp. 43–44, 75–81).

Second, finding place AB is a closed secondary votive deposit, found between the buildings A and B. With only a few exceptions, the largest part of the terracotta votive gifts was found in this context, numbering less than 300 in total (Hettner 1901, pp. 43–44, 75–81). Most of the bronze statuettes were found here (cf. De Beenhouwer 1979, pp. 1278–79). Coins from this closed context from Tiberius (AD 14–37) until (Valens (AD 364–378) indicate that somewhere in the late fourth century a certain cleansing of one of the temples had taken place. The uniformity of the context layer, the position of late coins in the lower part of the context, and the damaged and fragmented state of the votives are also indicators that instigated Hettner to argue for the interpretation of a cleansing of displayed votives from all or one of the temples (Hettner 1901; De Beenhouwer 1979; Cüppers 1983).

The third and fourth find contexts are those of the minor buildings B and C. In finding place B mostly weapons, fibulae, mirrors, lead washers, bronze fragments, shards and glass objects and coins have been found. In finding context C, however, a number of stone dedicator figures and gods (not more than twenty in total) were found at the eastern part of the building (Hettner 1901). Hettner argues that these votives were on display in this building, and therefore he suggests this was a minor temple (Hettner 1901). Other scholars, however, do not exclude the possibility that buildings B and C were annex buildings of temple A, in which only votives were on display (Cüppers 1990).

In addition, material was found in the four graves dating from the first century AD, against the northern precinct wall. In the first two burial places, fragments of terracotta statuettes, a gladius, two iron knives, two bronze fibulae, and shards have been found, as well as a fragment of a naked terracotta boy in grave 1, and a fibula, terracotta lion, an iron lance point in grave 2 (Hettner 1901).

4.2. Interpreting Religious Communicative Objects

How should we interpret the material objects that have been found in this sanctuary? Since no inscription has been found to provide an answer, it is not clear to which god(s) the sanctuary was dedicated. So far, only a few scholars have made suggestions. Based on the six bronze statuettes of Mars and the different kinds of weaponry found at different find contexts, Roymans argues the sanctuary was dedicated to local Mars deities (Roymans 1996). In contrast, the overwhelming majority of mother goddesses and fertility-type goddesses in the terracotta votives has led Wightman (1970) and Green (1986, 1992) to argue that the precinct in Dhronecken was exclusively connected with Mother goddesses.

However, I believe it is not possible nor desirable to pinpoint a specific god or goddess to this sanctuary based on the limited and fragmented evidence available. It is more likely that the rural sanctuary of Dhronecken was never dedicated to one god in particular, for it was in the nature of Roman religion that the housing of gods could be flexible. Even if a temple was dedicated to a particular god, one could worship other gods there as well. An analysis of all the votive material that has been characterized as gods by Hettner (1901) and Kyll (1966) provides quite a diverse picture of votive gods (Table 1).

Table 1.

Analysis of the votive material characterized as gods by Hettner (1901) and Kyll (1966).

So far, scholars have only regarded the local context of this sanctuary. I will argue that the glocalization framework offers a richer and reconsidered understanding of this particular dataset by including the global context and changing the focus to the specialization of this sanctuary. Derks already put forward (Derks 2006a, 2006b, 2009) a similar argument for a closely related and nearby sanctuary in Trier, that of Lenus Mars. Derks argues that this sanctuary should be seen as functioning as a site for the coming of age rite of passage (Van Gennep 1960). This was the ritual of Roman boys reaching manhood and their donning of the toga, a ritual that was adopted and adapted in the empire in different ways by local elites and non-elites (Derks 2010). I argue that in virtually all of the votive material that has been found in Dhronecken, both the deity statuettes and other votive representations, can be associated with the same ritual of coming of age too. Below, I will illustrate how glocalization can be understood as interconnected processes of the universalization of the particular (i.e., how the ritual became detached from its original context and plays a different role in the global context) and the particularization of the universal (i.e., how this globally understood ritual was shaped in the local context of Dhronecken) (cf. Witcher 2000; Versluys 2015).

The most important evidence is demonstrated by the several representations of naked children that have been found in Dhronecken, usually accompanied with representations of birds and additional fruits. The same votives have been found in larger amounts at a closely related temple for Lenus Mars near Trier. The representation of boys and girls with birds and toys became an increasingly dominant cultural element of Greaco-Roman sculpture (Derks 2006b, 2009). Derks (2006a, 2006b, 2009) summarizes that up until recently, scholars interpreted these images as direct representations of the dedicants, for example when parents gave these representations of their children as thanksgiving to the gods for the care of their children. In contrast, Derks (2009) convincingly argues that these votives should not be seen as direct representations that have been offered. Material objects were in fact often used in transitional rites of passage from one social status to another (Derks 2006b, 2009, 2010; cf. Van Gennep 1960). Thus, this material should rather be interpreted as symbolic representations of a non-elite rite of coming of age (Derks 2009).

This is a good example of where the glocalization framework provides new insights into the understanding of archaeological material. A local community sought to redefine their position within the new political context, and locally adapted the Roman (i.e., global) ritual of coming of age.

Boys or their parents used this religious votive material as fulfillment in the vows that were made for the well-being of the children associated with the rite of passage of coming of age. Unfortunately there are no inscriptions found at Dhronecken to further strengthen this point, but at the Lenus Mars sanctuary nearby some votives are epigraphically attested to be concerned with the welfare of the children as new adults, which were sometimes explicitly vowed for by their parents (Derks 2006b, 2009).

This argument can be further enhanced by investigating a possible difference between boys and girls (Derks 2006b). The focal variation of these sanctuaries may not reflect the change of votive material being discovered, but rather, as Derks (2006b) mentions, reflect the reality of different life cycles of men and woman and the different roles they played in Roman society. According to the discovered votive material, it seems that votives of boys are overrepresented in the Lenus Mars sanctuary at nearby Trier, while female votive gifts are overly present at Dhronecken (Derks 2006b). This does not insist that boys could not make offerings to the gods in rituals associated with becoming adult in Dhronecken, as approximately 10 votives of naked boys with birds were found, similar to the votives that were discovered in greater numbers at the Lenus Mars sanctuary.

As the majority of the votives catalogued as deities are mother goddesses, or at least goddesses related with fertility such as Venus, Cybele and Fortuna, some scholars so far associated the sanctuary of Dhronecken mainly with the ritual function of fertility. Wightman (1970) argues that the approximately 90 mother goddess votives indicate a fertility function, and that busts of children, sometimes accompanied with the mother goddesses themselves, served as a kind of protective function. Green (1992) argues that the nursing mother goddesses, Deae Nutrices, were very common in Gaul and German, as well as the mother goddess with a dog on her laps in the Treveran region, and argue they originated in the Celtic religion and are all concerned with fertility, life and regeneration, with a symbolic aspect of rebirth and regeneration. However, I already argued that looking at these votives in terms of continuation of native tradition versus what is Roman is an outdated and unfruitful approach. That local pre-Roman traditions played a role is not to be excluded, but it goes too far to argue, as Green (1992) does, that the images of the votives represent a true continuation of pre-Roman religion. Rather, the global (i.e., Roman) appearance of these votives should be interpreted in the context of glocalization, as the creation of new religious rituals out of global culturally dominant elements in a locally adapted context. This is visible in the ca. 90 votives representing some kind of a mother goddess. Only four votives are clearly indicated as Cybele (i.e., Magna Mater), but it is clear that the ca. 90 mother goddess votives share features that are common in the representation of Cybele too, such as mural crowns, the company of lions and being seated on a throne. Therefore, even in a remote rural sanctuary such as Dhronecken, in the outer region of the Roman empire, global religious elements (e.g., Cybele) appeared to be used in this context.

In addition, as Schwertheim (1974) has already shown with his ichnographically analysis, it is clear that the representations of Cybele found in the Treverian region have a clear local regional appearance. The votives found in Dhronecken and other sanctuaries in this region are based on one representation of Cybele sitting on a throne, her feet on a footstool, alongside the throne accompanied with lions. Her regionally local appearance in Dhronecken and its near area, shows to me on the one hand how Cybele as global religious element by means of glocalization processes is locally adapted (i.e., particularization of the universal). On the other hand, it further strengths the point that Dhronecken could be associated with the coming of age ritual for girls.

Regarding the found figurines of mother goddesses, Beck (2009) suggests that they could have been some kind of amulets. They were small and girls could easily carry them around, perhaps symbolizing protection in everyday life, or in particular during pregnancy (Beck 2009). The fact that they have been found in houses and in sepulchral contexts suggests that they perhaps could also have been used when girls or women died and the votives were buried alongside them (Beck 2009). Again, it illustrates the idea that a large amount of the votives found in Dhronecken associated with childhood, motherhood and fertility, could be associated with the rite of passage of coming of age of a woman. We can only speculate on the underlying reasons, but the amulets might have had a similar function to the toga ritual of boys coming of age, as they could have been offered when women successfully raised their children who then passed towards adulthood.

Other votive objects found that are used in daily life point in a similar direction. First, Kyll (1966) argues that some busts of boys that have been found at Dhronecken contain rattling stones in their head, making them likely to be personal toys of the children offered them. If this interpretation is valid, it is another example of objects that played a role in the coming of age rite of passage, in which children entering adulthood offered their toys. If we look at the primary literary sources, we may find a fragile but relevant fragment to back up this interpretation. For the ritual of the toga and the dedication of the bulla amulet from their youth, Derks (2009, p. 206) put together all historical references to this ritual in fasti inscriptions or texts. It is striking that in a fourth to fifth century AD work Docrina by Nonius Marcellus, a small fragment by Varro (1903) dating to ca. 116–127 BC (Saturarum Menippearum 150.463), was preserved in which he describes a ritual in which a girl before her marriage would dedicate her dolls and toys in the shrine of the Lares (cf. Warrior 2006, p. 32). While this is a piece of evidence on a ritual in Rome at an earlier stage, it is not possible to directly relate it to the sanctuary at Dhronecken, and we have to remain careful. It shows, nevertheless, that rituals in which girls dedicated toys and dolls before her marriage did exist in the Roman world. The interpretation of the figurines and toys thus might be enhanced by involving global contexts as the ritual described above.

Lastly, as Woolf (2003) points out, Matronae cults in general were quite popular and common in the provinces of the north-western part of the Roman empire. The Matronae cults in this particular region shared common iconographical appearance, but were locally addressed in a different way (Woolf 2003). The several Matronae cults are sometimes interpreted as ancestral worshipping that represented a continuation of pre-Roman religion, expressing a strong local identity and resistance to Roman religion and power (Woolf 2003). However, as Woolf (2003) makes clear, the Matronae cults do not refer to local kin/groups and tribes, but rather symbolically represent adult women and similar concepts. The fact that this type of cult was popular around this region is significant, because it was an increasingly competitive and global (Woolf uses the term cosmopolitan) environment in which a relatively high amount of religious choice was involved (Woolf 2003). Similarly, Beard, North and Price (1998) characterize the early Imperial period as a ‘marketplace of religions’. In this context Woolf (2003) explicitly assesses the value of the application of globalization theory, as Roman imperialism caused an increasing emphasis on the local, but the local could only make sense in a global context. As illustrated with the Matronae cults, they were all monumentalized in a common religious language style practices were conducted according to the precise rules of Roman ritual across the whole empire, and epigraphically attested in the same style. However, apart from this common Roman style, locally the cults were different in their meaning, focus, naming and sometimes in their images (Woolf 2003). Thus, the Matronae cults too are an example of glocalization processes in the Roman religious sphere, as they possess both local and global factors. The cults did not make any sense in the local or the global context alone, but rather this dynamic and complex interplay between local and global shaped these cults.

5. Case Study 2: Pro Salute Imperatoris

In the second case study, a particular kind of votive material that emerged on an a global (i.e., empire-wide) scale is discussed. It is a common epigraphically attested pro salute imperatoris ritual, a vow for the well-being of the emperor and sometimes also imperial family members, dedicated to a wide variety of gods. As I will argue, this ritual is both publicly and privately expressed and is developed out of a clear glocalization process, containing both local and global interests. It involves the universalization of the particular (i.e., originally a Republican ritual now globally associated with the emperor and Rome) and the particularization of the universal (i.e., the various local adaptions of this global form of religious communication).

To start with, and perhaps most significantly, this ritual in the Imperial era was actually a transformed ritual that already existed in the Republican era. Salus was a prominent virtue and a public cult of Salus seems to be dated back to Rome to the late fourth century BC, when a temple was vowed in 307–306 BC during the Samnite war, and dedicated on the Quirinal in 303–302 BC, according to Livius (Ab Urbe Condita 9.43.25; 10.1.9) Salus can be related both to personal well-being and safety, including physical health (Livius 1926; cf. Winkler 1995, pp. 16–19), and also to communal security (Noreña 2011). This last point is attested in the public rituals (vota publica) in the Roman republic, namely the pro salute rei republica at five- and ten- year intervals, and annually on the first of January at the event when new magistrates took office (sollemnis votorum nuncupatio) (Daly 1950, p. 164). In the Roman empire, these vows were transformed into public vows for the emperor. Cassius Dio (ca. 155–235 AD) reports (Historia Romana 44.6; 51.19) (Dio 1914–1927) that vows were annually taken on behalf of Caesar, and that an annual votum pro salute imperatoris was established in the time of Augustus. There is abundant epigraphical evidence to prove that this ritual was performed throughout the empire and in the same style as in Rome (Hahn 2007). The ritual could also be performed on special occasions, for example on the birthday of an emperor or on his return to the city (Noreña 2011, p. 142). These examples illustrate that a particular ritual became universalized and received different functions and meanings.

This ritual is sometimes discussed from a merely political viewpoint, as Ando (2000) for example argues that these annual vota were mainly oaths of loyalty, re-assuring the prime position of one individual, the emperor, uppon whom the well-being of the commonwealth depended. However, we only have to take into account the records of the fulfillments of the rituals by the Arval Brethren to see that the vows are foremost invocated to (the supreme) gods, and the religious conviction that everything was dependent on the will of these gods (Hahn 2007, p. 240). This example, and the fact that the ritual form is identical throughout the empire in both public and private pro salute imperatoris votives shows to me that, in contrast with Ando, these pro salute rituals were not just mere acts of loyalty to the emperor, but certainly contained a reflection of an important religious conviction that conveys the coming together of local and global interests.

In addition, the ritual is examined from different perspectives within studies on the so-called Imperial cult. I agree with Gradel’s (2002) line of reasoning that emperor worship was neither exclusively a religious nor political practice, which expressed the supreme power of the emperor, just like worship of gods acknowledge their supreme powers. The Imperial cult was not a cohesive system, and Gradel (2002) shows how a variety of complex cults and rituals differ in their approach towards seeing the emperor as god. Asking to what extent Romans regarded emperors as gods is a modern question to ask; in the ancient world divine honors were established and could appear in different contexts and formulas (Gradel 2002). In addition, Fishwick (2012) explicitly excludes the vota pro salute from his discussion on the divinity of the emperor, because they are virtually all on behalf of the emperor voted towards the gods, not towards the person of the emperor itself. While we may conclude that the vota pro salute imperatoris are not a pure religious practice towards the emperor, it is striking that an emperor received such a prominent place in the religious lives of people in the whole empire, who participated in the religious rituals and dedicated private votives on behalf of the emperor as well (Liertz 1998).

The cult for the salus of the emperor fits into a broader pattern of cults that were established for “divine qualities that were closely connected with the person of the emperor. To this group belonged the cult of the imperial peace (pax Augusta) or the fortunate destiny of the emperor (fortuna Augusta). In this case divinities that before the empire had been the property of the whole Roman state were redirected to the emperor and privatized” (Herz 2007, p. 307). This is the essential element of the votives that I would like to highlight, as it is here that glocalization is able to enhance our understanding of the material culture. We see a universalized way of communication that was globally understood and shared representational elements. The ritual is recorded in inscriptions throughout the empire in nearly the same style and model and became associated with the well-being of the emperor. This might imply a certain top-down regulation of the ritual if only the global context is regarded, or a Romanization framework is applied. It certainly seems plausible that, as Noreña (2011) argues, salus was one suitable virtue in the representation on coins too, as it was used to actively promote the ideological benefits of the Roman empire and the person of the emperor to a broad audience. Noreña (2011) argues that with coins with the Roman emperor and salus, Roman imperial members could ideologically transmit that the salus of the state, the emperor, and also the local communities were in principle interdependent, as everyone was dependent on it. In addition, Várhelyi (2010) argues that Roman senators who dedicated these votives in other parts of the empire expressed power relations in the empire, with the emperor on top. These very public votives made on behalf of the emperor were ascribed with their own names, enhancing their status in the province and defining their power position as well. In this way, religious communication was, besides being religious in the first place, on a second level a process of continuously negotiating and establishing power relations (Várhelyi 2010).

However, I will argue that besides a clear global importance, considering the local interest in this global ritual further enhances our understanding. The pro salute votives are in fact locally different, as they were vowed to a broad variety of gods (Beard et al. 1998, p. 360). Liertz (1998), studied the discovered 11 pro salute inscriptions in the western provinces of Belgica, 32 in Germania Inferior and 64 in Germania Superior, showing that all kinds of variable and combinations of ascribed gods could be made. It seems to me that, in line with Laurence and Trifilò (2015), it was the connection with the global institution—here the imperial family—that spread the concept of this pro salute imperatoris ritual, not its geographical connectivity. For example, it also occurred that senatorial administrators in the empire dedicated the votives to local divinities Várhelyi (2010). As I argued earlier, it might not be helpful to regard the combination gods in one pro salute votive in terms of native and Roman gods and possible cyncretisms (cf. Fishwick 2004), but rather see them in their newly created context in which local and global interests played a complex role. Thus, it seems clear that processes of particularization of the universally understood ritual took place in each local context and were shaped in different ways.

In addition, Plinius (Epistulae 10.35–36; 10.52) reports that he, as responsible provincial governor, conducted the annual pro salute imperatoris ritual with the help of the local community (Plinius 1906). Presented with a clear model, local communities both publicly and privately took up this ritual and gave the emperor a prominent place in their religious communication (Liertz 1998). The content of the vow is the perfect illustration of a type of religious communication that before Roman conquest did not exist in the provinces, and, more importantly, now clearly constituted both local and global interests converging in one ritual on behalf of the salus for the emperor. I agree with Hahn (2007, p. 247), the pro salute inscriptions “are clearly modifications of republican prayers offered annually for the safety and prosperity of the state. Now, however, the state’s welfare is represented as dependent on that of the emperor. The new prayers served to communicate this novel state of affairs but also, through the power of ritual, to establish it as convention.”

Local elites could manipulate and enhance their social positions by, for example, performing these pro salute imperatoris vota (Rizakis 2007). From the reign of Augustus onwards, local elites began to use global cultural expressions in general, but the pro salute ritual exemplifies that at this point the religions of other communities were becoming systematically oriented towards Rome (Woolf 2012). In addition, they could clearly give shape to the changed world and their own position in a global empire. As Herz (2007) concludes, the personal security and well-being of the emperor (securitas imperatoris) was identified with the security and well-being of the whole empire (securitas imperii). In the eyes of local communities who vowed pro salute imperatoris, they had to contribute their share in safeguarding the well-being of the emperor, the empire and their own, by turning directly to their local gods (Herz 2007). The religious material culture here described is just one instance of how local communities accomplished this, as Herz (2007) further illustrates other (collective) actions in which regular prayers and sacrifices were made, including publicly offered vows in which the assembled population took a solemn vow.

Thus, while Cicero in the late Republic (Oratio pro Rabirio Posthumo 20) could express that the salus of every man of every order lay in the salus of the res publica (Cicero 1909), in the Imperial period one’s own salus was symbolically attached to the salus of the emperor. Although it became a common and widely attested ritual, I argue that it was not solely a top-down global ritual to spread power and global religious communication, nor was it a solely bottom-up local ritual to religiously honor the welfare of the emperor. It can best be understood as a glocalized phenomenon in which both local and global interests played a part in the complex creation of a new form of religious communication; a vow for the well-being of the emperor, representing the global empire, of which all local communities now were part, invoking not Roman nor indigenous gods, but gods that at that time and that moment globally made sense in each local situation.

6. Conclusions

This article began by engaging in theoretical discussions on Romanization, globalization theory and Roman religious change. Arguments were provided to show that glocalization can be applied to the Roman world for substantive reasons. By connecting the analytical framework of glocalization with the idea of Van Andringa for seeing religious change as the creation of a whole new and common (i.e., global) religious communication language, I proposed using the framework of glocalization as an explicitly modern interpretative model to study the material culture presented in the two subsequent case studies. Furthermore, I argued that glocalization should not be seen as a process leading to cultural homogeneity, but as a complex negotiation process in which new forms of Roman (i.e., global) cultural elements were developed on a global and local scale, both in top-down and bottom-up directions. The material culture was differently adopted and adapted in various local contexts, but at the same time globally defined as Roman.

Application of the glocalization framework led to richer understandings of two types of religious material culture, which showed that religious change on a local scale was a complex process in which new forms of religious communication were created out of an interrelated and ongoing process of local and global religious expressions, in which local communities could express their understanding of their place in a global context. First, the religious material found in Dhronecken consisted of objects that show a relationship between the local community and the global Roman empire. A universalized ritual of coming of age became particularized in this region, adopting the dominant common religious language. The votives, shaped in a globally recognizable forms, should be interpreted as a symbolical representation of the coming of age ritual, locally adopted and adapted. The votive material represent an instance of a small part of the Treveran community in terms of how they constructed their own version of what they thought was Roman religion (which become their religion as well) reflecting their place in the new global Roman empire. Second, with the pro salute Imperatoris ritual, a glocalization perspective illustrated that both imperial administrators and local communities had their reasons for participating in the rituals. Both groups shared the conviction that their own safety and well-being was closely connected to the safety and well-being of the emperor. This global ritual was therefore differently applied in each local context, also as a reflection of local understanding of their position in a global context.

Although the conclusions of this paper remain limited, as only two small case studies are provided, both case studies showed that analysis of material culture becomes enriched if the local and global contexts are taken together and are not studied in isolation. Further research should be conducted to investigate the viability of glocalization for other types of material culture. In addition, it might also be interesting to statistically analyze distribution patterns of the pro salute imperatoris votives discussed in case study 2 (see for instance Laurence and Trifilò 2015), and further analyze local particularizations.

As a last remark, I would like to make clear that I do not regard glocalization as the framework that can provide all the answers that previous frameworks could not, nor that it is free from limitations. However, I believe it to be the ultimate task of every generation of historians and archaeologists to reconstruct and explain the past to their own generation, using conceptual frameworks that are relevant and understandable in their own time. I view that the growing body of studies taking a glocalization approach shows that using glocalization as a heuristic and explicitly modern tool to reinterpret material culture is a worthwhile endeavor.

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge Saskia Stevens and Leonard Rutgers for their critical yet constructive comments on my Research Master thesis (which this paper is based on), from which I learned a lot. I would also like to thank the Royal Netherlands Institute in Rome (KNIR) for the scholarship I received to work on the present study. In addition, I would like to express my gratitude to the editors and the anonymous reviewer for their help in improving this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Ando, Clifford. 2000. Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire. California: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, Clifford, ed. 2003. Roman Religion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, Clifford. 2007. Exporting Roman Religion. In A Companion to Roman Religion. Edited by Jorg Rüpke. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 429–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, Clifford. 2008. The Matter of the Gods: Religion and the Roman Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1996. Modernity At Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, Mary, John North, and Simon Price. 1998. Religions of Rome. 2 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Noémie. 2009. Goddesses in Celtic Religion. Lyon: Université Lumière. [Google Scholar]

- Belayche, Nicole. 2007. Religious Actors in Daily Life: Practices and Related Beliefs. In A Companion to Roman Religion. Edited by Jorg Rüpke. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 275–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bodel, John. 2009. “Sacred dedications”: A problem of definitions. In Dediche Sara nel Mondo Greco-Romano: Diffusione, Funzioni, Tipologie (Religious Dedications in the Greco-Roman World: Distribution, Typology, Use). Acta Instituti Romani Finlandiae 35. Edited by John Bodel and Mika Kajava. Rome: Institutum Romanum Findlandiae and American Academy in Rome, pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Caesar, Caius Julius. 1869. Bellum Gallicum. Translated by William Alexander McDevitte, and W. S. Bohn. New York: Harper & Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius. 1891. Oratio de Haruspicum Responso. Translated by Charles Duke Yonge. London: George Bell & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius. 1909. Oratio pro Rabirio Posthumo. Translated by Charles Duke Yonge. London: George Bell & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius. 1933. De Deorum Natura. Translated by Harris Rackham. Harvard: Loeb. [Google Scholar]

- Cüppers, Heinz, ed. 1983. Römer an Mosel und Saar; Zeugnisse der Römerzeit in Lothringen, in Luxemburg, in Raum Trier und im Saarland. Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Cüppers, Heinz. 1990. Die Römer in Rheinland-Pfalz. Stuttgart: Theiss. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, Lioyd W. 1950. Vota publica pro salute alicuius. Transactions of the American Philological Association 81: 164–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beenhouwer, Jan. 1979. De Gallo-Romeinse Terracottastatuetten van Belgische Vindplaatsen in Het Ruimer Kader van de Noordwest-Europese Terracotta-Industrie. Leuven: Katholieke Universiteit Leuven. [Google Scholar]

- Dench, Emma. 2005. ‘Romulus’ Asylum: Roman Identities from the Age of Alexander to the Age of Hadrian. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Derks, Ton. 1995. The Ritual of the Vow in Gallo-Roman Religion. In Integration in the Early Roman West: The role of Culture and Ideology. Edited by Jeannot Metzler. Luxembourg: Musée National D’histoire et D’art, pp. 111–28. [Google Scholar]

- Derks, Ton. 1998. Gods, Temples and Ritual Practices. The Transformation of Religious Ideas and Values in Roman Gaul. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Derks, Ton. 2002. Roman imperialism and the sanctuaries of Roman Gaul. Review. Archéologie des Sanctuaires en Gaule Romaine. Textes reunis et presentes par William van Andringa. Journal of Roman Archaeology 15: 541–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, Ton. 2006a. Le grand sanctuaire de Lenus Mars á Tréves et ses dédicaces privées: Une Reinterpretation. In Sanctuaires, Pratiques Cultuelles et Territiores Civiques Dans l’Occident Romain. Edited by Monique Dondon-Payre and Marie-Thérèse Raepsaet-Charlier. Brussels: Le Livre Timperman, pp. 240–70. [Google Scholar]

- Derks, Ton. 2006b. Les rites de passage et leur manifestation matérielle dans les sanctuaires des Trévires. Antiqua 43: 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Derks, Ton. 2009. Van toga tot terracotta: Het veelkleurige palet van volwassenwordingsrituelen in het Romeinse Rijk. Lampas 42: 204–28. [Google Scholar]

- Derks, Ton. 2010. Les Rites de Passage Dans L’Empire Romain: Esquisse d’une Approche Antropologique. In L’antiquité et L’anthropologie: Bilans et Perspectives. Actes du Colloque Toulouse 18–19 Mars 2010. Edited by Pascal Payen and Évelyne Scheid-Tissinier. Turnhout: Collection Antiquité et Sciences Humaines, vol. 1, pp. 43–80. [Google Scholar]

- Dio, Cassius. 1914–1927. Ῥωμαϊκὴ Ἱστορία, Historia Romana. Translated by Earnest Cary. Harvard: Loeb. [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone, Mike. 1995. Undoing Culture: Globalization, Postmodernism and Identity. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Finley, Moses I. 1987. Ancient History: Evidence and Models. London: Chatto & Windus. [Google Scholar]

- Fishwick, Duncan. 2004. The Imperial Cult in the Latin West. Studies in the Ruler Cult of the Western Provinces of the Roman Empire. Volume III: Provincial Cult. Part 3: The Provincial Centre: Provincial Cult. In Religions in the Graeco-Roman World 147. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Fishwick, Duncan. 2012. Cult, Ritual, Divinity and Belief in the Roman World. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, Philip W. M. 1997. Mommsen to Haverfield. The origins of studies of Romanization in late 19th-c. Britain. In Dialogues in Roman Imperialism: Power, Discourse, and Discrepant Experience in the Roman Empire, Supplement. Edited by Susan E. Alcockand and David J. Mattingly. Journal of Roman Archaeology 23: 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, Andrew. 2013. Thinking about Roman Imperialism: Postcolonialism, Globalization and Beyond? Britannia 44: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1993. Religion as a Cultural System. In The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. Edited by Clifford Geertz. London: Fontana Press, pp. 87–125. First published 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Gradel, Ittai. 2002. Emperor Worship and Roman Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Miranda. 1986. The Gods of the Celts. Gloucester: Barnes & Noble. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Miranda. 1992. Symbol and Image in Celtic Religious Art. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, Kevin. 2008. Learning to consume: Consumption and consumerism in the Roman Empire. Journal of Roman Archaeology 21: 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeussler, Ralph. 2013. Becoming Roman? Diverging Identities and Experiences in Ancient Northwest Italy. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, Frances Hickson. 2007. Performing the Sacred: Prayers and Hymns. In A Companion to Roman Religion. Edited by Jorg Rüpke. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 235–49. [Google Scholar]

- Herz, Peter. 2007. Emperors: Caring for the Empire and Their Successors. In A Companion to Roman Religion. Edited by Jorg Rüpke. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 304–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hettner, Felix. 1901. Drei Tempelbezirke im Trevererlande. In Festschrift des Hundertjährigen Bestehens der Gesellschaft für Nützliche Forschungen im Trier. Trier: Kommissionsverlag der Fr. Lintz’schen Buchhandlung. [Google Scholar]

- Hingley, Richard. 2005. Globalizing Roman Culture: Unity, Diversity and Empire. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchner, R. Bruce. 2008. Globalization Avant la Lettre: Globalization and the History of the Roman Empire. New Global Studies 2: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodos, Tamar. 2010. Local and Global Perspectives in the Study of Social and Cultural Identities. In Material Culture and Social Identities in the Ancient World. Edited by Shelley Hales and Tamar Hodos. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hodos, Tamar. 2014. Stage settings for a connected scene. Globalization and material-culture studies in the early first-millennium B.C.E. Mediterranean. Archaeological Dialogues 21: 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodos, Tamar, ed. 2017. The Routledge Handbook of Archaeology and Globalization. London and New York: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Horden, Peregrine, and Nicholas Purcell. 2000. The Corrupting Sea: A Study of Mediterranean History. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, Keay, and Nicola Terrenato, eds. 2001. Italy and the West: Comparative Issues in Romanization. Oxford: Oxbow Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kyll, Nikolaus. 1966. Heidnische Weihe- und Votivgaben aus der Römerzeit des Trierer Landes. Trierer Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Kunst des Trierer Landes und Seiner Nachbargebiete 29: 5–114. [Google Scholar]

- Laurence, Ray, and Francesco Trifilò. 2015. The global and the local in the Roman empire: Connectivity and mobility from an urban perspective. In Globalisation and the Roman World: World History, Connectivity and Material Culture. Edited by Martin Pitts and Miguel John Versluys. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 99–122. [Google Scholar]

- Liertz, Uta-Maria. 1998. Kult und Kaiser. Studien zu Kaiserkult und Kaiserverehrung in den germanischen Provinzen und in Gallia Belgica zur Römischen Kaiserzeit. In Acta Instituti Romani Finlandiae 40. Rome: Institutum Romanum Findlandiae. [Google Scholar]

- Livius, Titus. 1926. Ab Urbe Condita. Translated by Benjamin Oliver Foster. London: Loeb. [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly, David J. 2004. Being Roman: Expressing identity in a provincial setting. Journal of Roman Archaeology 17: 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, David J. 2011. Imperialism, Power, and Identity: Experiencing the Roman Empire. Oxford: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Naerebout, Frederick G. 2006–2007. Global Romans? Is globalization a concept that is going to help us understand the Roman Empire? Talanta 38–39: 149–70. [Google Scholar]

- Nederveen Pieterse, Jan. 2009. Globalization: Consensus and controversies. In Globalization and Culture: Global Mélange. Edited by Jan Nederveen Pieterse. Plymouth, New York and Toronto: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Noreña, Carlos F. 2011. Imperial Ideals in the Roman West: Representation, Circulation, Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- North, John, and Simon. R. F. Price. 2011. The Religious History of the Roman Empire : Pagans, Jews, and Christians. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pitts, Martin. 2008. Globalizing the local in Roman Britain: An anthropological approach to social change. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 27: 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, Martin. 2012. Globalization. In The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. Hoboken: Wiley, Available online: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com (accessed on 20 March 2017).

- Pitts, Martin, and Miguel John Versluys. 2015. Globalisation and the Roman World: Perspectives and Opportunities. In Globalisation and the Roman World: World History, Connectivity and Material Culture. Edited by Martin Pitts and Miguel John Versluys. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Plinius, Caius Caecilius Secundus (minor). 1906. Epistulae. Translated by Karl Friedrich Theodor Mayhoff. Leipzig: Teubner. [Google Scholar]

- Rives, James B. 2000. Religion in the Roman Empire. In Experiencing Rome: Culture, Identity and Power in the Roman Empire. Edited by Janet Huskinson. London: Psychology Press, pp. 245–76. [Google Scholar]

- Rives, James B. 2007. Religion in the Roman Empire. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rives, James B. 2010. Graeco-Roman Religion in the Roman Empire: Old Assumptions and New Approaches. Currents in Biblical Research 8: 240–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizakis, Athanasios. 2007. Urban Elites in the Roman East: Enhancing Regional Positions and Social Superiority. In A Companion to Roman Religion. Edited by Jorg Rüpke. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 317–30. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, Roland. 1992. Globalization: Social Theory and Global Culture. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, Roland. 1994. Globalization or Glocalisation? The Journal of International Communication 1: 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, Roland. 1995. Glocalization: Time-Space and Homogeneity-Heterogeneity. In Global Modernities. Edited by Mike Featherstone, Scott Lash and Roland Robertson. London: Sage Publications, pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, Roland, and William R. Garrett, eds. 1991. Religion and Global Order. New York: Paragon House. [Google Scholar]

- Roudometof, Victor. 2005. Transnationalism, Cosmopolitanism and Glocalization. Current Sociology 53: 113–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudometof, Victor. 2016a. Glocalization: A Critical Introduction. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Roudometof, Victor. 2016b. Theorizing Glocalization: Three Interpretations. European Journal of Social Theory 19: 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roymans, Nico, ed. 1996. From the Sword to the Plough: Three Studies on the Earliest Romanisation of Northern Gaul. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]