Abstract

This article provides an analysis of the enduring disagreements among bioethicists over the divide between secular and religious boundaries that are reflected in liberal, libertarian, and conservative approaches to medicine as a profession and vocation. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the most authoritative voices to address the problem of suffering were Protestants, Strict Calvinists, hydropaths, and homeopaths. Other religious and medical groups had regularly confronted pain and suffering in the nineteenth century in light of the discovery and increasing use of anesthesia. Rationalizations for suffering were first and foremost indebted to strong beliefs about divine will and about the seemingly inevitable course of nature. Did physical pain reflect the wrongdoing of one individual or of an entire community? What was the appropriate way to respond to the natural circumstances of growth, decay, and healing? Such questions produced a varied rhetoric of suffering that emerged in new ways in the second half of the twentieth century. Questions and concerns about the ethical foundations of medical practice—what should and should not be permitted—illustrate the present cultural struggles.

1. Introduction

… where death is felt to be inevitable, there is a strong tendency to mitigate its connection with suffering. Even in the extreme case of execution, deliberate torture preliminary to death would arouse deep revulsion, however heinous the crime. Certainly there is no widespread objection to the use of sedatives to reduce physical pain in fatal illnesses or accident cases.(Parsons 1963, p. 62)

I intend to set out here an argument that the rise of public involvement in matters that once were decidedly more the purview of physicians and their professional associations was coincident with the arrival of medical ethicists, trained in philosophy and law, thus supplanting the voices of doctors specifically on these same matters. Questions about the role that physicians should assume in such matters as end-of-life care had been underwritten by larger cultural forces, not least of which were religious ones that were rapidly superseded by political forces that now reflect deep differences in how the authority of medicine (and its role in the relief of pain and suffering) was to be understood and determined. The decline of that authority has created a cultural vacuum, which has led to legislative initiatives and judicial oversight to compensate for the absence of authoritative voices and oversight in the profession while revealing all the more those deep differences in an understanding of suffering.

One aspect of these deep differences is reflected in the emergence of contrasting views presented by medical ethicists (or bioethicists) in what has been associated with what are now called culture wars. A focus on what counts for understanding the nature of suffering and how the decline in the central role historically played by the medical profession may help to clarify how the authority of medicine, despite all appearances, continues to play a fundamental role in profound matters of life and death.

To understand suffering poses a challenge for any kind of intellectual consideration. The immediately brought-to-mind opposite—not suffering—has only one truly permanent condition (or at least some believe) in human experience: death. Suffering may be understood to be one of the most expansive and expandable concepts for which any kind of intellectual and scientific account must inevitably fall short. Unlike the achievement of scientific certainty at any given moment in time, the failure to represent the subjectivity of suffering in terms adequate to a model of causation results in both assertions and resistance to those assertions that are the basis of all rhetoric about the place of suffering in human life. In recent decades, such assertions and resistance to them have garnered much attention under the rubric of “culture wars”, which have become the basis for existential conflicts that undermine confidence in all institutions, including medicine.

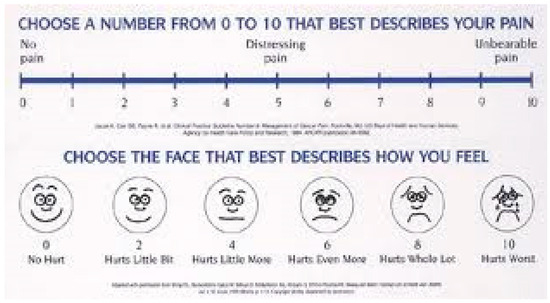

Consider a scale that asks patients to describe the degree of physical pain they are experiencing. The chart (Figure 1) below illustrates the choices.

Figure 1.

Emotion Faces.

Those faces express what any observer can readily acknowledge but not necessarily verify other than by one’s own visual observation and subjective interpretation. Nevertheless, this quantification of pain is one formula for determining the dispensing of pain-relieving medications. Some say it has actually contributed substantially to narcotic addiction. If this is an unintended consequence, it is because the response to pain has been reduced to a very persuasive argument that suffering’s subjectivity should be an essential factor in defining and responding to it. In other words, suffering has existential determinants that either make sense in a universe of discourse about it or do not.

2. The Rhetoric of Suffering before Bioethics

In the United States, until the beginning of the twentieth century, the most authoritative voices to reflect on suffering were Protestants, and they represented a broad spectrum of accounts about the place of suffering in human life (See Klassen 2011). The historian Martin S. Pernick, for example, describes how strict Calvinists, hydropaths, homeopaths, and other religious and medical groups confronted pain and suffering in the nineteenth century in light of the discovery and increasing use of anesthesia (Pernick 1985). Rationalizations for suffering were first and foremost indebted to strong beliefs about divine will and about the seemingly inevitable course of nature. Was childbirth a punishment for the sins of Adam? Did physical pain reflect the wrongdoing of one individual or of an entire community? What was the appropriate way to respond to the natural circumstances of growth, decay, healing, and injury? All of these questions produced a varied rhetoric of suffering that had yet to be challenged and consolidated by the new ambitions of scientific medicine, which took fuller shape throughout the course of the twentieth century.1

William James recognized that by the end of the nineteenth century, what he described as “a strange moral transformation” had already preceded scientific advances in the alleviation of pain and suffering. He wrote in his chapter on “Saintliness” in The Varieties of Religious Experience:

A strange moral transformation has, within the past century swept over our Western world. We no longer think that we are called on to face physical pain with equanimity. It is not expected of a man that he should either endure it or inflict much of it, and to listen to the recital of cases of it makes our flesh creep morally as well as physically. The way in which our ancestors looked upon pain as an eternal ingredient of the world’s order, and both caused and suffered it as a matter-of-course portion of their day’s work, fills us with amazement.(James [1902] 1985, pp. 239–40)

In one sense, what James identified was very much the opposite of the nearly canonical view today that progress in scientific understanding and technological innovation outpaces our moral capacity to respond to them. On the contrary, the most significant change came in the rhetoric of suffering, the strange moral transformation that pain and the suffering caused by it were not and did not have to be inevitable. This change alone has been instrumental in encouraging the ambitions of both science and technology to the present moment.

3. Bioethics in Perspective

The origins of medical ethics in the nineteenth century linked medical practice with medical professionalism. The founding of the American Medical Association in 1847 represented the collective effort on the part of practitioners to present themselves as professionals above the fray of a myriad of other “doctors” who could, in the gradual formalization of medical education, no longer simply claim the mantle of “regular” practitioner without a license (i.e., state sanction). In this way, the appeal to “ethics” (in the AMA’s 1847 Code of Medical Ethics) was the first rhetorical strategy of medical professionalism. Having an ethical code did not mean that all doctors could be counted on to abide by it but rather that they were obliged to abide by it, a very different encouragement than direct supervisory oversight by outsiders. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, the rhetoric of medical ethics seemed entirely devoted to problems of personal demeanor, collegiality, and the organizing of finances. What happened during the second half of the twentieth century has by now several illustrative accounts, all of which are acknowledgments that the fraternity of medicine was challenged not because doctors were suddenly proven to be quacks or incompetent (although some certainly were) but because whatever injury and suffering were attributed to medical practice or involvement (i.e., iatrogenesis), new and fascinating public scrutiny was taking shape both by journalists, academics, and government and eventually by doctors themselves (See Rothman 1991; See also Martensen 2001).

The implications for what then emerged as a rhetoric of bioethics, as distinct from and sometimes in conflict with medical professionalism, have been extensive and are still being revealed. What is meant by rhetoric here is the use of language and argument that is intended to be persuasive, that is, to create those kinds of strong claims that are often contested by equally strong counterclaims, something, to be sure, that is not regularly documented in the now enormous bioethics literature. Indeed, I have written elsewhere that one of the brilliant rhetorical strategies of the bioethics profession, reflecting the long arc of medical professionalism, has been to engage publicly difficult issues with the appearance of being above the fray (See Imber 2008b; See also Imber 2003). Much of this appearance has had to do with who has assumed, over time, the mantle of speaking for bioethics. One significant representation of this mantle has been who gains public attention in the mass media. A rare glimpse of tensions among professional bioethicists about the legitimacy and perils of such media attention is illustrated in a letter to the New York Times thirty years ago by R. Alta Charo and Daniel Wikler, who wrote the following:

All that bioethicists can offer is a somewhat less politically or emotionally charged, somewhat more dispassionate evaluation of our options. No doubt you will always be able to find one ethicist who considers a new development grotesque and another who wants to wait and see. But personal feelings about such innovations even from respected academics, do not reflect any rigorously derived consensus. We suggest the following pledge be taken by ethicists and the news media alike: No ethicist should be asked for a personal opinion. If asked, no personal opinion should be given. And if given, no personal opinion should be published. With issues so complicated, we cannot afford to let a small group of academics be a self-appointed, secular version of the Committee for the Defense of the Faith.2

The emphasis on “a rigorously derived consensus” suggests one kind of rhetorical strategy: a focus on democratic participation (at least among the fraternity of bioethicists) in the formulation of public policy about medically controversial matters. How consensus would be rigorously determined is an entirely different matter. Charo and Wikler were more concerned with persuading the principal actors (bioethicists and the media) to foreswear personal opinions, implying that asking for and providing personal opinions was unprofessional, if not unethical. They sought to persuade in such a way as to affirm the appearance of being above the fray. To appear to take sides in such matters is to reveal personal opinion over and against some form of derived consensus. Yet here, the problem grows more complicated because even if there were a larger group pursuing a derived consensus about these matters, since 1994, the concerns of Charo and Wikler have been muted by the public role that succeeding bioethics commissions have played in prominent ways on the public stage.

4. The Culture War Comes to Bioethics

Further context about the cultural role of bioethics should be given before focusing more specifically on the rhetoric of suffering and its vicissitudes. One of the strongest salvos against what has by now been generally viewed as the politicization of bioethics was published during the George W. Bush administration in 2006 by Ruth Macklin in The Hastings Center Report. (Macklin had already sounded the alarm three years earlier in a brief editorial in the British Medical Journal entitled “Dignity is a useless concept” (Macklin 2003)). Her intention was to identify “The New Conservatives in Bioethics: Who Are They and What Do They Seek?”, locating bioethicists and bioethics rhetorically over and against those who she claimed are not professionally trained bioethicists and who she certainly did not consider to be part of “the mainstream” of bioethics.

Macklin’s argument against a “conservative” critique of bioethics is first stated in the idiom of medical professionalism: “conservative” is to bioethics as “quack” is to medical professionals. This ad hominem tactic operates at two levels.3 The first is simply the claim that the new conservatives are outsiders to the professional guild of bioethicists. These interlopers even created (in 2003) their own journal, The New Atlantis: A Journal of Technology & Society which continues to be published. The second level of ad hominem argument comes in the accusation that prior to the appearance of these new conservatives, debates in bioethics had little or no political valence: “authors did not self-identify as liberals or conservatives, nor were they, with rare exceptions, labeled as such by their opponents in specific debates or controversies”(Macklin 2006, p. 34).

Macklin’s approach is to demonstrate by semantic parsing of such terms as liberal and conservative that it is difficult to “shoehorn” bioethicists into one ideological position or another. She illustrates this by referring to already publicly prominent figures in the national conversations and debates about controversial medical matters, in particular Daniel Callahan, to whom she credits a variety of positions that could be termed both conservative and liberal. On the other hand, Leon Kass is presented as “the chief public spokesperson for conservative bioethicists in the United States”. Kass earns this distinction because he was “a political appointee of George W. Bush to head the President’s Council on Bioethics in 2001” (Ibid., p. 35) as if previous and subsequent appointees to commissions on bioethics were not “political” appointments, that is to say, appointed by politicians. The implication is clear in Macklin’s phrasings that conservatives have politicized contentious public matters such as abortion and euthanasia. In other words, they are not “political” appointments but “politicized” ones. Apparently, until the arrival of pugnacious outsiders and the subsequent loss of balance by some insiders, bioethicists did not envision playing a visible part in politics, and certainly not as partisan spokespersons. To be viewed above, the fray has long served as a rhetorical strategy for defining professionalism, and bioethics mastered this process with admirable and rapid success following the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

Macklin furthers her characterizations of “conservative” by arguing that their “stated positions do not really distinguish them from others that appeared much earlier, promoted by groups that were anything but conservative” (Ibid., p. 35). She compares the new conservatives to radical feminists on such matters as assisted reproduction and birth control. Their similarities are held to be the result of a deep suspicion of what is “artificial” in contrast to what is “natural”. The radical feminists arising from their counter-cultural objections to technical advances are thereby linked to contemporary conservatives (more than a generation later) who also express objections to such advances, even though such objections may be made on very different grounds. The central problem with this comparison is that it need not disqualify such objections (from either group) simply because they challenge the status quo of two different eras. Indeed, in echoing nineteenth-century objections to certain approaches to the restoration of health and the alleviation of suffering by the hydropaths and homeopaths, the radical feminists and others similarly developed their objections against a perceived dominant culture that sought to reduce the influence and impact of such counter-cultures. The new conservatives in bioethics, led by figures more sympathetic to the approaches of the major religious traditions, echo nineteenth-century acknowledgments of providence if not direct divine intervention. Macklin inadvertently identifies the strong affinities not only between these movements but also in terms of their historically resonating approaches.

At least one consequence of Macklin’s efforts to discredit allegedly dissident movements in and around mainstream bioethics is the greater emphasis unintentionally put on the ultimate goals of bioethics rather than on the proven methods of participation by those calling themselves bioethicists.4 The culture war in bioethics that Macklin reveals has brought to light a call for deeper reflection that rises to the level of conviction and politics, which is understandably objectionable (and no doubt disorienting) to those who already imagine themselves secure in the kinds of participation they pursue as professionals in the name of bioethics. That security is reflected through participation locally in, for example, IRBs, and nationally through participation in various national conferences and governmental commissions.

5. Dignity, Awe, Souls, and Human Nature

Perhaps Macklin’s most effective challenge to the rhetoric of the new conservative bioethicists is to criticize–in a way reminiscent of ordinary language philosophy–certain terms, such as dignity, which is deemed meaningless and useless for the purposes of shaping ethical thinking and, subsequently, social policy recommendations. She takes particular exception to the writings of Yuval Levin, a senior editor of The New Atlantis, who wrote the following in its inaugural issue in 2003:

A conservative bioethics proceeds by dissecting taboos, but it has as its mission to prevent our transformation into a culture without awe filled with people without souls. It is, to be sure, a paradoxical mission. But conservatives do not expect consistency in life, and so should not be too surprised by paradox. Its twisted character does not make the mission unachievable. And its achievement is, properly, a key priority of the American right. Much depends upon it.(Levin 2003, p. 65)

This mission of conservative bioethics is, Macklin believes, to establish “immutable truths” “akin to religious believers who assert that theirs is the ‘one, true religion’”. She asks rhetorically whether claims for “truly human bioethics” by conservatives make mainstream bioethics “Nonhuman? Inhuman? Or simply, not truly human?” She criticizes another writer who calls for “a true bioethics”, asking “What, is the contrast with ‘a true bioethics’—a false bioethics?” This is not a strategy of arguing that intends to address what these conservative writers might mean or what they are trying to argue. Rather, it signifies one way of drawing a line, for example, between the rational and the poetic, thus banishing the poets who, by using such terms as dignity, awe, and souls, excite not reason but emotion, and in our day, religious and political emotions.5

A similar criticism is evident in Macklin’s taking to task the claim that “Children are a gift”. Here, the problem is not only that this is metaphorical language but that it can only make sense if it is “understood and accepted by members of a homogeneous, religious audience, especially if … reference to the giver [i.e., God] of the gift [is made]” (Macklin 2006, p. 38). She was referring to a statement that Leon Kass made while delivering a presentation on genetic selection and enhancement at what she describes as a “secular” conference. Here, the line drawn between religious and secular, in effect, between church and state, represents an inversion of who is authorized (and in what jurisdictions) to examine and propose answers to questions about such matters as genetic selection and enhancement. Macklin’s approach is to welcome theological perspectives as long as they are identified as such, but she does not draw the further implication that once a claim is deemed “religious”, it no longer is viewed as an analytic argument as distinct from a professed belief when expressed in a secular forum. This raises the question about the rhetoric and its uses not only of religious discourse but of secular discourse as well.

Macklin criticizes Kass’s characterization of resistance to technological advance in his formulation of “the wisdom of repugnance”. In her view, emotion again trumps reason, and she praises Yuval Levin for pointing out that gut reactions should not determine government policy, using his example of interracial marriage. But this use of Levin against Kass is disingenuous because Macklin ignores Levin’s further concerns about the fate of moral sentiments in general in modernity.6 She writes, “The trouble is, of course, that in pluralistic societies, people do not all share the same repugnance or the same moral foundations”. Of course, this is neither an endorsement of a relativistic worldview nor a denial of some sort of mechanism to achieve consensus; otherwise, why deliberate at all on any bioethical matter? In the final analysis, Kass is condemned because his “style of writing [is] alien to that found in mainstream bioethics” (Macklin 2006, p. 39). The rhetoric of secularism imitates religious accusations of heterodoxy. But this rhetoric does not treat the “conservative” heterodoxy as a form of dissident writing. Instead, the rhetorical foundations of rationality, which champion terms such as “alien” and “irrational”, serve to define permissible discourse, in this instance, on ostensibly medical–ethical matters.

Perhaps Macklin’s most damning criticisms are left for what she terms “mean-spirited rhetoric”. She asserts that “when the purpose is to attack opponents by mislabeling their positions or using analogies likely to be highly offensive to some people, rhetoric becomes mean-spirited”. She excoriates Richard John Neuhaus for equating physician-assisted suicide with eugenics, accusing him of either deliberate distortion or “woeful ignorance of concepts commonly discussed in bioethics”. Worse than that was Neuhaus’s use of analogies of practices such as abortion and euthanasia to Nazism. Macklin concludes, “It is hard to think of an analogy more likely to offend and even outrage large numbers of people”. She also criticizes Charles Krauthammer for his comparisons of techniques of assisted reproduction with “manufacture”, along with his invoking the term “artificial” with a “distinctly negative connotation”. Finally, both Neuhaus and Krauthammer receive ad hominem rebukes as harbingers of a new conservative movement in bioethics, demonstrated by the appearance of their claims in “magazines (Commentary and The New Republic) rather than in scholarly journals” (Macklin 2006, p. 40). This kind of boundary setting lacks an acknowledgment of the ways in which the dispute over abortion has permeated American politics for many decades, even early in the 1970s, spawning a political party (Imber 2011). The idea that the “scholarly journals” could exist apart and insulated from the controversies addressed in magazines such as Commentary or The New Republic while at the same time analyzing and deliberating on these same matters reflects a kind of academic bitterness over who should be considered and heard, again, above the fray.

Expectations about the need for public and democratic deliberation on ethical matters, a call for which Charo and Wikler made three decades ago, appear to put Macklin’s fierce and passionate denunciations of the rhetoric of conservative bioethics in direct conflict with any hope for a rigorously derived consensus. The difficulty is not only that the rhetoric of conservative bioethics apparently appeals more to the inevitably messy realities of democratic and pluralistic deliberations but also that it denies mainstream bioethics pride of place in directing how the rigorously derived consensus will be or, at best, should be achieved. Despite her defense of mainstream bioethics, Macklin cannot have it both ways, which accounts, in my opinion, for much of the energy in her otherwise clear and sustained defense of the need for dispassionate analysis of these controversial matters. One way to consider the conservatives is to recognize how much better they recognize that politics is a blunt instrument of both social intransigence and social change. Either way, this is always a politics of campaigning for or against change, hardly the vision of intellectually stimulating attention to the details and nuances allegedly associated with “scholarly journals”. Bioethicists have long confronted the dilemma of determining the nature of their role in “public relations”. To hold those who are successful at gaining public attention responsible for debasing the discourse is one way to deflect criticism about what all those “scholarly journals” are supposed to achieve in terms of the public good.

6. The Rhetorical Uses of Suffering

A consideration of Macklin’s assessment of conservative bioethics helps lay the grounds for understanding why concern for human suffering took a more prominent place in the collective mind of bioethicists as George W. Bush assumed the presidency in 2001. By the time Macklin penned her account, Leon Kass and other ostensibly conservative commission members had conducted a very different kind of floating seminar that invited enormous resistance from various sectors of the scientific establishment, not to mention mainstream bioethicists. The central issue, the one that inspired Bush to appoint Kass in the first place, was the use of embryonic stem cells for medical research. The defining, acknowledging, and alleviating of suffering evoke specific kinds of contrasts between the promise of progress and the limits on human possibility. Not everything is possible, at least not all at once or for everyone all the time. Yet the idea of progress, as the sociologist Robert Nisbet observed, inspires not only real improvements and outsized promises but also warnings about its dark side in terms of constraints on human freedom (Nisbet [1980] 1994).

For Ruth Macklin and mainstream bioethicists, what underlies their rhetoric of suffering is a strong belief in progress as it enables a greater achievement of justice for those who suffer from life’s many forms of inequality. Eric Cohen is put on the docket for writing that “the biotechnology project cuts to the very foundation of the American project”. The term “project” is assailed largely for its lack of specificity, akin to a conspiracy theory attributed to conservative critics who are said to be in search of ways to connect different constituencies to similar goals. These are primarily goals of resistance to biological enhancement, and conservatives are said to reject the “project” of finding ways to make everyone biologically equal. Macklin writes, “It is easier to understand opposition to stem cell research on the grounds that it involves the destruction of human embryos than it is to comprehend Cohen’s apparent opposition to helping suffering children lead more normal lives by making them ‘biologically more equal.’ Why is it acceptable (or is it?) to alter the physical environment to benefit individuals with disabilities (such as public accommodations for wheelchairs) but not their biological attributes?” (Ibid., p. 41).

Macklin elides a good deal in her pointed questions about the kinds of boundaries set out by conservatives when it comes to equalizing the circumstances of differently abled individuals. One type of boundary is between nature and nurture, and, however conceived, it does fit Macklin’s useful question of whether fashioning the biological nature of a person is motivated by any sentiment and purpose different than fashioning the environment in such a way as to accommodate better those less able to negotiate it as well as so-called normal people. Rather than ask what differences may exist between these two types of intervention, she accuses Cohen, Levin, and Kass of selective endorsement of some moral sentiments over others. But this overlooks thorny ethical (and political) questions about both kinds of intervention. Macklin assumes interventions in the environment are one important basis of a robust liberal humanitarianism applied to the creation of a more just society. If this were true as more than a guiding sentiment, there would have been an absence of politics in the struggle to pass the Americans with Disabilities Act signed into law in 1990. The Act extended civil rights to the disabled while at the same time raising often complicated questions about its application to real life situations (See Mezey 2005; See also Nielsen 2013). Macklin does not mention the inevitably of politics as a presiding reality in many ethical matters, preferring instead to impugn motives for resisting transformational “projects” whose consequences are, according to conservative bioethicists, inevitably expressed in political, legal, and constitutional terms. Instead, “justice” is masked as “ethics”, and the sleight of hand that conceals what remains unspoken provides ample opportunity to impugn the motives of the conservative bioethicist.

The question of how to understand what, when, and where intervention is appropriate or just in order to reduce or eliminate suffering is an amorphous one, with bioethics playing an important role in laying out in elaborately abstract ways what may be at stake in endorsing movement in one direction or another. This role has taken a unique shape over the past half-century in large part because the question draws on a variety of forms of expert guidance, not only about oversight but about the future direction and funding of research. The convergence of multiple identities of lawyer, ethicist, physician, and scientist (sometimes all in one person) is historically significant in the evolution of expertise.7 Macklin is keen to acknowledge that mainstream bioethicists disagree on a host of matters, but she stops short of explaining why these disagreements receive much less public attention than those mounted by conservatives. By defining oneself as “mainstream”, thus seeing oneself as running between various tributaries of dissent that flow in openly political directions, whether left or right, the unspoken discontent may really be about not being taken seriously in the role of an expert advisor.8

By the conclusion of her account of conservative bioethics, Ruth Macklin describes herself as a “liberal, humanitarian bioethicist”.9 What is striking about this acknowledgment is how glib she remains about conservatives referring to “so-called liberals” and “allegedly liberal bioethicists”. Her point, I think, is that each thinker and writer should be afforded the dignity of saying what he or she believes rather than being subject to characterizations that dismiss others in a wide swath of criticism. Fair enough. But this confuses collegiality with participation in the public sphere where very little is at stake other than being heard, as it were, above the fray. But to get above the fray and the visibility (and potential respect) it affords can be either an individual or institutional achievement. For decades, that achievement was largely allied with a politics of collaboration between think tanks and government. That model may have served its usefulness in light of the stakes raised by all sides in bioethical debates. Macklin admits that her hope for bioethics is focused on matters of justice “in access to health care and the gap in the health status between rich and poor, as well as broader issues of global justice in medical research and health disparities between industrialized and developing countries” (Ibid.). Here is stated an agenda on the reduction of suffering around the world that is compared to the absence of such concerns among the new conservatives who are labeled as fatalists opposed to various interventions.

The reduction of suffering under Macklin’s guidance is clearly a political project, historically undertaken by agencies and schools of public health and their pioneers in the strategies to combat both infectious and non-infectious diseases across the globe. The conservatives appear to arrive on the scene with little to offer to this particular project. But how is that omission an argument against what they have raised as concerns? The problem is that the conservatives are not liberal humanitarians in the received sense of those terms. In his famous treatise, Language, Truth and Logic, A. J. Ayer concluded: …we who are interested in the condition of philosophy can no longer acquiesce in the existence of party divisions among philosophers. We know that if the questions about which the parties contend are logical in character, they can be definitively answered. And, if they are not logical, they must either be dismissed as metaphysical or made the subject of empirical inquiry”.10 Macklin is a philosophical descendant of central analytical observations in Ayer’s work, that not only must someone be right and someone wrong but also that there is no room for the metaphysical as a basis for truth-finding and truth-telling. A soul may be a terrible thing to waste for some, but for others any search for its existence or verification is a waste of time, and resources are better spent on empirically verifying whether justice is being served or denied.

There is, then, a profound bifurcation in the perceptions of what constitutes moral thinking in bioethics around the matter of suffering. On the one hand, Macklin makes plain her contempt for the rhetorical animadversions of the conservatives who profess views about bioethical matters. Yet she acknowledges without irony that she, too, relies on more than analytical strategies to determine what is best to do in general, if not always in particular cases. The liberal humanitarian worldview is founded on a rhetorically useful concept of justice, where claims for equality are made against inevitable scarcities in resources and knowledge. In this sense, the conservatives are fatalists, even if their rhetorical approach to suffering would probably emphasize acceptance over resignation. Suffering is thus rhetorically up for grabs in much the same way that the issue of abortion has been for quite some time around the uses of pro-choice and pro-life, neither of which can be criticized as unclear, unpersuasive or rhetorically self-defeating. For Macklin and many others, suffering must be reduced quantitatively and qualitatively as a matter of public trust. Progress may have unintended consequences, but any consequences emerge for analytical consideration, not as warnings about unwished futures to be avoided. She follows directly in the footsteps of William James’s insight about the moral inevitability of judging suffering as something to be fought against rather than endured.11

7. Coda

Sigmund Freud recognized that physical suffering would be much less of a burden in modern life than mental pain. The exquisite sufferings of the affluent alone have produced an industry of therapy fully prepared to minister to mental pain. Bioethicists have shown themselves, much in keeping with the American public, to have had less to say about mental rather than physical pain and suffering. This is part of a broad cultural resignation about the sinkhole that opens up when confronting the concerns of the worried well (Imber 2008a). At the same time, alongside the analytical tradition in bioethics, of which Macklin is a key representative, new alliances are being forged, particularly by faith traditions that have sought greater involvement in medical decision making, thus challenging a long-established tradition of secularism in medicine (See Cadge 2013; See also Peteet and Balboni 2017). The faith traditions can hardly be described as adversarial to the ambitions of cure and comfort, but they establish as a matter of both reason and faith new arguments about the limits of medicine. Religious bioethics may strike some as a contradiction in terms, but what emerges from various forms of thoughtful engagement about suffering from religious standpoints is a growing awareness of the many ways in which these partnerships strengthen the assistance and care given to patients, which is, beyond the ever sought after technical advances, the ultimate goal of medicine (Imber 2017a, 2017b).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | A fine example of the ancient and enduring challenges to understanding suffering in the context of anesthesia can be found in (Holzman 2022). |

| 2 | The New York Times, 14 January 1994, A28. |

| 3 | I do not advance here any particular judgment about the uses and abuses of ad hominem argumentation. That debate has been taken up in bioethics proper. See (Chambers 2007). |

| 4 | Macklin criticizes (Stevens 2000) for labeling mainstream bioethics as conservative (e.g., allying itself with the avatars of technical advance) even though the new conservatives label the mainstream as (too) liberal. Again, the problem is not so much the confusion over labels but Macklin’s clear animus toward any characterization that bioethics is deserving in any way of such criticisms, whether from the left (e.g., Stevens) or the right (e.g., the new conservatives). |

| 5 | For a serious consideration of the idea of dignity, see (Kateb 2011). |

| 6 | Kass’s line of thinking finds resonance in psychology. See (Rozin et al. 2008; Imber [1963] 2014). |

| 7 | The evolution of the expert and expertise was remarked on by Laski (1931, Tract 235); Imber (1984). |

| 8 | Experts and expertise are enduring subjects of assessment. Laski (1931, Tract 235); Imber (1984). |

| 9 | Macklin (2006, p. 42) Macklin reiterated these ideas in a more satirical form in (Macklin 2010). |

| 10 | Ayer ([1946] 1952, pp. 133–34). Macklin’s enduring commitment to philosophical clarity connected to the uses of language can be observed in her essay (Macklin 1967). |

| 11 | One account that presents such dilemmas is (Wolff 2012; Reverby 2012). Sociological and anthropological literature also endorses a progressive stance about the amelioration of what is called “social suffering”. See (Bourdieu 1993; Kleinman et al. 1997). |

References

- Ayer, Alfred Jules. 1952. Language, Truth and Logic. New York: Dover Publications. First published 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1993. The Weight of the World: Social Suffering in Contemporary Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cadge, Wendy. 2013. Paging God: Religion in the Halls of Medicine. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, Tod. 2007. The Virtue of Attacking the Bioethicist. In The Ethics of Bioethics: Mapping the Moral Landscape. Edited by Lisa A. Eckenwiler and Felicia G. Cohn. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 281–87. [Google Scholar]

- Holzman, Robert S. 2022. Anesthesia and the Classics: Essays on Avatars of Professional Values. Boca Raton: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Imber, Jonathan B. 1984. The Well-Informed Citizen: Alfred Schutz and Applied Theory. Human Studies 7: 117–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imber, Jonathan B. 2003. Religious Sources for Debates in Bioethics. In Society and Medicine. Edited by Carla M. Messikomer, Judith P. Swazey and Allen Glicksman. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, pp. 211–26. [Google Scholar]

- Imber, Jonathan B. 2008a. Anxiety in the Age of Epidemiology. In Trusting Doctors. Princeton: Princeton University Press, chp. 8. pp. 144–66. [Google Scholar]

- Imber, Jonathan B. 2008b. The Evolution of Bioethics. In Trusting Doctors: The Decline of Authority in American Medicine. Princeton: Princeton University Press, chp. 6. pp. 130–43. [Google Scholar]

- Imber, Jonathan B. 2011. Fetal Rights. In Handbook of Human Rights. Edited by Thomas Cushman. London: Routledge, pp. 384–88. [Google Scholar]

- Imber, Jonathan B. 2014. Introduction to the Transaction Edition. In Taboo Topics. Edited by Norman L. Farberow. New Brunswick: Aldine Transaction, pp. vii–xxi. First published 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Imber, Jonathan B. 2017a. How Navigating Uncertainty Motivates Trust in Medicine. AMA Journal of Ethics 19: 391–98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Imber, Jonathan B. 2017b. Spirituality, Resistance, and Modern Medicine: A Sociological Perspective. In Spiritualty and Religion within the Culture of Medicine: From Evidence to Practice. Edited by John R. Peteet and Michael J. Balboni. New York: Oxford University Press, chp. 16. pp. 263–74. [Google Scholar]

- James, William. 1985. The Varieties of Religious Experience. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. First published 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Kateb, George. 2011. Human Dignity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Klassen, Pamela E. 2011. Spirits of Protestantism: Medicine, Healing, and Liberal Christianity. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman, Arthur, Veen Das, and Margaret Lock, eds. 1997. Social Suffering. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laski, Harold. 1931. The Limitations of the Expert. London: Fabian Society. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, Yuval. 2003. The Paradox of Conservative Bioethics. The New Atlantis 1: 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Macklin, Ruth. 1967. Actions, Consequences and Ethical Theory. Journal of Value Inquiry 1: 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macklin, Ruth. 2003. Dignity is a useless concept. British Medical Journal 327: 1419–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macklin, Ruth. 2006. The Conservatives in Bioethics: Who Are They and What Do They Seek? Hastings Center Report 36: 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macklin, Ruth. 2010. The Death of Bioethics (As We Once Knew It). Bioethics 24: 211–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martensen, Robert. 2001. The History of Bioethics: An Essay Review. Journal of the History of Medicine 56: 168–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezey, Susan Gluck. 2005. Disabling Interpretations: The Americans with Disabilities Act in Federal Court. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, Kim E. 2013. A Disability History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet, Robert. 1994. History of the Idea of Progress, 2nd ed. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers. First published 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, Talcott. 1963. Death in American Society—A Brief Working Paper. New York: The American Behavioral Scientist. [Google Scholar]

- Pernick, Martin S. 1985. A Calculus of Suffering: Pain, Professionalism, and Anesthesia in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peteet, John R., and Michael J. Balboni, eds. 2017. Spiritualty and Religion within the Culture of Medicine: From Evidence to Practice. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reverby, Susan. 2012. Ethical Failures and History Lessons: The U.S. Public Health Service Research Studies in Tuskegee and Guatemala. Public Health Reviews 34: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, David J. 1991. Strangers at the Bedside: A History of How Law and Bioethics Transformed Medical Decision Making. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Rozin, Paul, Jonathan Haidt, and Clark McCauley. 2008. Disgust: The Body and Soul Emotion in the 21st Century. In Disgust and Its Disorders: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment Implications. Edited by Bunmi O. Olatunji and Dean McKay. Washington: American Psychological Association, pp. 9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, M. L. Tina. 2000. Bioethics in America: Origins and Cultural Politics. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, Jonathan. 2012. The Human Right to Health. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).