Abstract

This article presents the innovative endeavor by Muḥammad ʿĀbid al-Jābrī and Nasr Ḥāmid Abū Zayd in interpreting the Qurʾān through a humanistic lens. Their approach marks a pivotal shift, viewing the Qurʾān as a dynamic text that actively engages with the human interpreter. This human-centric perspective underpins their hermeneutical method, which employs lexicography, philology, and semantics to unearth the layered meanings within the Qurʾānic narrative. The article delves into the nuances of their methodologies, drawing parallels and distinctions, and underscores their profound impact on modern Qurʾānic hermeneutics.

1. Introduction

The Qurʾānic text exemplifies a form of communication that encapsulates the roles of a sender, a receiver, and a linguistic code. This perspective on the Qurʾān, embraced by a cohort of Muslim intellectuals often referred to as ‘new thinkers’, advocates a scientifically inclined approach to deciphering the Qurʾānic revelation. These intellectuals purposefully distance their interpretations from mythical or metaphysical interpretations, striving instead for a more grounded understanding. Their theories pivot around the role of language and its intricate relationship with both the meanings embedded within the text and those extending beyond it1. This conceptual framework offers a renewed viewpoint on the dynamic between Muslims and the Qurʾānic revelation. In this context, the revelation is not merely a directive for passive adherence but a subject ripe for the recipient’s critical scrutiny. The recipient, thus, emerges as a pivotal figure within this communicative paradigm, simultaneously receiving and interpreting the message. This interaction is not with an absent entity but with a tangible text and its active linguistic components, challenging the traditional concept of a universal recipient. Each era and sociocultural context generate unique conditions for the reception and interpretation of the Qurʾān, leading to distinct meanings. This approach’s pivotal challenge lies in redefining the recipient of the text from a passive receiver to an active participant in generating meaning, thereby contributing to the text’s coherence and unity. The concept of authorship transforms into a textual strategy, as delineated by Umberto Eco (1990, p. 41), moving away from any transcendental authority. Consequently, the question of the author’s intent as an integral part of the text evolves into a more complex process of interpretation that unfolds during the act of reading. This paradigm thus fosters a dynamic Qurʾānic text, rich with multiple meanings awaiting interpretation2.

In this article, we undertake a detailed comparative analysis, focusing on the innovative hermeneutical methods of Muḥammad ʿĀbid al-Jābrī (1935–2010) and Nasr Ḥāmid Abū Zayd (1943–2010). Central to our exploration is how each intellectual utilizes and interprets the Qurʾānic linguistic code to unravel the text’s embedded historical and human experiences. This approach is not merely about linguistic analysis; it is an endeavor to understand how these scholars’ interpretations influence and redefine Qurʾānic hermeneutics. The core thesis of this study asserts that the unique perspectives of al-Jābrī and Abū Zayd on the Qurʾānic linguistic code represent a pivotal shift in the field, blending traditional Islamic thought with contemporary humanistic and linguistic insights. This perspective not only redefines the roles of sender, receiver, and linguistic code within the Qurʾānic discourse but also positions the text as a living, breathing construct in constant dialogue with contemporary contexts. By focusing on these two contemporary Arab intellectuals, the article aims to highlight the transformative potential of their interpretations in modern Qurʾānic studies, especially in how they contribute to the evolving understanding of Arab-Muslim identity and textual dynamics within Islamic tradition.

In the following sections, this article employs a comparative analytical method to dissect and juxtapose the hermeneutical approaches of Muḥammad ʿĀbid al-Jābrī and Nasr Ḥāmid Abū Zayd. The analysis delves into their respective methodologies, employing a critical examination of their texts and ideas to unearth the layers of meaning and interpretation they offer to Qurʾānic hermeneutics. The core thesis of this article is predicated on the assumption that the humanistic and linguistic lenses through which al-Jābrī and Abū Zayd view the Qurʾān represent a significant paradigm shift in Islamic studies. This shift is crucial for understanding contemporary interpretations of the Qurʾān and its impact on Muslim identity and thought. By focusing on these two scholars, the article aims to highlight how their innovative approaches contribute to a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the Qurʾān, one that transcends traditional interpretations and resonates with modern intellectual and cultural contexts

2. Textual Dynamics: Recontextualizing Qurʾānic Discourse through Linguistic Analysis

In their quest to modernize Arab thought, Muḥammad ʿĀbid al-Jābrī and Nasr Ḥāmid Abū Zayd dedicated a substantial portion of their intellectual pursuits to dissecting the intricate relationships between Islamic heritage, religion, and the state. In his landmark publication in 1980, Naḥnu wal-turāth: qirā’āt mu‘āṣirah fī turāthinā al-falsafī3 (al-Jābrī 1980) Al-Jābrī advocated for a rationalist reappropriation and reinterpretation of tradition and heritage. A decade later, in 1990, Nasr Ḥāmid Abū Zayd published Mafhūm al-naṣ—Dirāsah fī ʿUlūm al-Qurʾān (The Conception of the Text: A Study in Qurʾānic Sciences), marking the beginning of a research program centered on the concept of the text as a means of representation and communication. Both al-Jābrī and Abū Zayd advanced the notion that the text transcends its literal scriptural confines, thereby integrating broader realities. The analyses they develop initiate the emergence of an interpretative paradigm of Qurʾānic discourse (ta’wīl al-Qur’ān) based on a structural linguistic approach that deconstructs interpretations that have hermetically sealed the Qurʾān, rendering it largely inaccessible in its entirety, save for select excerpts that are often instrumentally exploited by certain radical ideologies. By examining the Qurʾān through the lens of its revelation circumstances, al-Jābrī and Abū Zayd not only provide the missing contextual background often overlooked in traditional readings that follow the order of surah length but also challenge the ahistorical view of the text. This shift in perspective, from seeing the Qurʾān solely as a divine revelation or a static book to appreciating it as a dynamic corpus, deeply rooted in its historical and situational context, is significant. Their method accentuates the textual dimension of the Qurʾān, emphasizing its complexity as a document interwoven with history, thereby offering a deeper understanding of its content and structure beyond conventional interpretations.

The concepts of text and interpretation that Abū Zayd discusses in his work do not undermine the divine origin of the Qurʾān4 but instead bring new linguistic perspectives into play, showing how language interacts with reality to forge new meanings. Abū Zayd notes, “The Ancients did not use the term ‘text’ to refer to the Qurʾān and hadiths, as we do in contemporary language. They usually used other words like ‘Book’ (kitāb), ‘Revelation’ (waḥy), or ‘Qurʾān’ to refer to the Qurʾānic text” (Abū Zayd 1999, p. 184). Such designations encapsulate the Qurʾān within a scriptural frame “enclosed in a chronology that is both summary and open to a before and after eternity. A more rigid, binding thinkable, therefore accompanied by a more extensive, more essential unthinkable as we delve into the time of orthodoxy” (Arkoun 1991, p. 14). Al-Jābrī, on the other hand, asks a different question: whether the Qurʾān, in its entirety, with its discourse, composition, and various readings, constitutes the word of God, or only its meanings constitute this word, (al-Jābrī 2006). For both Abū Zayd and al-Jābrī, the linguistic approach steers the reader to consider the crucial question of “how is this said?” rather than “by whom and why is this said?”. This process of readability is constantly in interaction with the reader and their sociocultural horizon. In this perspective, psycholinguist Walter Kintsch defines text comprehension as the outcome of an interaction between the characteristics of the text itself, as a semiotic object generating its own readability, and those of the reader. The reader participates in constructing the text through reading, thereby influencing its meaning and coherence. “The benefits found for high-coherence text may lead one to conclude that facilitating the reading process by increasing text coherence should, without fail, enhance text comprehension” (McNamara and Kintsch 1996). Indeed, while emphasizing its linguistic nature and reception as a textual product, the views of al-Jābrī and Abū Zayd regarding the Qurʾān evolve throughout their intellectual trajectories to move toward contextual analyses. These become significant factors for interpretation underpinned by a dialectical relationship with the text for both thinkers. They also highlight the linguistic specificities of the Qurʾānic text and the various possibilities of understanding that invoke the sociocultural horizon of the time. The relationship between the text, the context, and its reception forms the three generative pillars of meaning (El Makrini 2016, p. 44)5.

The reconceptualization of the Qurʾānic revelation as naṣ, or ‘text,’ marks a significant shift in Qurʾānic studies, profoundly influencing the perception of the Qurʾān among many Muslims. This linguistic perspective, echoing Toshihiko Izutsu’s insights, necessitates a reevaluation of the Arab-Muslim identity in the context of its foundational text. Izutsu notes, ‘Revelation, at its earliest stage, is primarily and preeminently linguistic in nature… it is a concept working within the semantic field of language and speech’ (Izutsu, Revelation as a Linguistic Concept in Islam). This view aligns with the notion of the Qurʾān emerging not as a static, completed entity, but rather as a dynamic, linguistic construct. Such a paradigm shift, as highlighted by Abū Zayd (1999), calls for a transition from traditional reading and memorization to a deeper, more analytical engagement with interpretation. Izutsu further elaborates that in Islam, ‘Revelation means that God spoke, that He revealed Himself through language, and through human language’—a decisive fact that underscores the Qurʾān ’s role as a complex, linguistically embedded document, necessitating hearty engagement and interpretation

For al-Jābrī and Abū Zayd, the linguistic aspect of the Qurʾān is crucial in dissecting the scripture’s discourse structured as a revelation in a textual format6. The Qurʾān thus presents itself to its audience7 as a scriptural space where “meaning unfolds as part of an interpretive exercise, a profoundly serious and educationally significant endeavor. (…) The Qurʾānic text serves as a bedrock for the cultivation of an ethical system, of which it is itself the archetypal embodiment” (Mégarbané 2015, p. 23). In this context, the Qurʾānic text becomes a site for reconstitution and interpretation, essential for clarifying its breadth and implications (cf. Eco 1995)8. For these scholars, the challenge lies in mastering the interpretive keys of this seminal Islamic text and examining the relationship between the text and its reader.

Understanding the role of the linguistic sign is fundamental in Abū Zayd’s textual framework. He emphasizes the interplay between the signifier and the signified, a concept that is deeply rooted in the Mu’tazilite approach to the Qurʾān. This approach is akin to the linguistic theories of Ferdinand de Saussure, who delineated the relationship between the signifier (the form of a word) and the signified (the conceptual meaning). For instance, Abū Zayd references Al-Jāḥiẓ’s metaphor of the word as the body to the soul of meaning, which echoes Saussure’s distinction between the signifier and signified (Abū Zayd 1999, p. 46). This parallel is drawn to highlight how Abū Zayd’s interpretation aligns with foundational linguistic concepts in Western theory, indicating a convergence of Islamic and Western thought in the understanding of language’s role in shaping meaning. Additionally, the reference to Jacques Lacan’s work on the human-symbolic relationship (Lacan 1966, p. 450) further complements this view. Lacan’s perspective on how linguistic signs shape human reality and experience can be seen as parallel to Abū Zayd’s approach to the Qurʾān. By recognizing these parallels, we gain a deeper understanding of how Abū Zayd’s interpretation of the Qurʾān is not just rooted in Islamic tradition but also resonates with broader, cross-cultural linguistic theories. These insights reveal Abū Zayd’s innovative approach in making the Qurʾānic text more relatable and humanized, encouraging a more engaged and interpretive interaction with its content.

The primary aim of this textual shift is to revive the dynamic essence of the Qurʾān ’s meaning, transcending the stale focus on static signs (Arkoun 1991, p. 37). Mohammed Arkoun’s historical and linguistic examination delves into the hidden layers of the textual universe, elucidating the evolving connotations within the intricate network of the Arabic language (Arkoun 1991, p. 41). This approach foregrounds the textual event, emphasizing the latent, linguistically discernible sense. This perspective not only enriches the understanding of the Qurʾānic narrative but also opens up avenues for new interpretations and meanings, continually influenced by the language’s evolution and the sociocultural contexts in which it is engaged.

Orthodox Sunni interpretations have traditionally negated the presence of esoteric meanings within the Qurʾān, adhering firmly to the concept of ‘fait accompli’ as articulated by Arkoun (1991, p. 53). This approach emphasizes adherence to established interpretations, legitimizing the authority of the caliphate through explicit texts and the practices of early disciples. Consequently, the hermeneutical effort (ta’wīl)9 aimed at uncovering these deeper, hidden meanings (bāṭin)10, the place from which the speaker has withdrawn, is often sidelined. In this hermeneutic turn, there is an element of the self that becomes intertwined with the interpreted text. In the depths, or in the folds, of an interpretive journey, an intertwining of the self with the text occurs. In this nuanced process of Qurʾānic hermeneutics, the objective involves grasping and appropriating the prophetic experience behind the materiality of the message.

For al-Jābrī and Abū Zayd, the concept of revelation (waḥy) transcends conventional understanding, encompassing a range of expressions like gestures, writings, inspirations, implicit statements, and signs (al-Jābrī 2006, p. 112; Abū Zayd 1999, p. 126)11. These signifiers reflect a spectrum of spiritual experiences, including dreamlike states (ḥulm), visions (ru’yā), and divine inspirations (ilhām), used to convey the meaning of a message that is ineffable and indescribable. Their perspective sheds light on revelations related to cosmic elements, articulated in a divine order and aesthetic, unique in their nature. This approach distinguishes between the signifier (the form of the revelation) and the signified (its deeper meaning). An example of such a revelation is described in the Qurʾān: “And from this nebula, He fashioned the substance of seven heavens in two days, and assigned to each heaven its duty” (41:12). This verse not only speaks of the creation of the cosmos but also of the divine inspiration behind it. It prompts contemplation of the ‘phenomenology of its own manifestation’ (Mégarbané 2015, p. 42), suggesting a self-awareness of the divine process. The metaphorical interpretation of this verse could lead us to contemplate the structured complexity of the universe and the interconnectedness of its parts. It invites reflection on the idea of cosmic order and the role of divine creativity in structuring existence.

These verses are characterized by a self-reflective style, privileging rhetorical devices over direct reference. This echoes ancient Arabic poetry, wherein the rhetorical approach seeks to captivate the reader through the aesthetic and poetic quality of the arrangement, suggesting that belief may be deeply rooted in these aspects of the message (Ricœur 1975)12. The text thereby gains authority and legitimacy through its rhetorical depth. As an iconic sign, the textual event unfolds its persuasive power, subjugation, and laws over the signified. Jacques Derrida, in his work L’écriture et la différence, elucidates this concept by deconstructing the conventional understanding of a ‘sign’: he states that a sign has traditionally been understood as a signifier referring to a signified, distinct from the signifier itself. However, he argues that if the fundamental distinction between the signifier and signified is obliterated, the term ‘signifier’ itself becomes obsolete as a metaphysical construct (Derrida 1967, p. 412). Such nuanced interpretations are notably absent in fundamentalist readings, where the concepts of expression, speech, sign, signifier, and signified coalesce into a singular, eternal divine entity. This convergence exemplifies a form of determinism deeply entwined with metaphysical dogma and an extreme sanctification of the sign.

3. Al-Jābrī and the Rational Approach to Qurʾānic Interpretation

MuḥammadʿĀbid al-Jābrī, after dedicating nearly seventeen years to his seminal work, Naqd al-ʿaql al-ʿarabī13 across four volumes14, profoundly analyzes the intersection of heritage (turāth) and culture (thaqāfah), and their influence on contemporary political frameworks. His work paves the way to a novel approach to the Qurʾān15 aiming to render it “contemporary both to its own context and to our present time” (al-Jābrī 1994, p. 20). Contrary to the mechanical historicism that characterizes some contemporary Arab scholarship, which seeks a clean break from Arab-Islamic tradition (cf. Laroui 1973), al-Jābrī advocates for a reappropriation of tradition, using it as a stepping stone for transcending it. He critiques the current state of Arab thought, lamenting its inability to distance itself from its religious and cultural past and its tendency to blur speculation with factual information, leading to an ‘inappropriate ideological mishmash’ (al-Jābrī 2007, p. 8)16. Al-Jābrī identifies two predominant but problematic approaches in the Arab intellectual sphere: the fundamentalist approach, with its deceptive idealization of the past17 and the orientalist or liberal approach, which overemphasizes the present, thus creating confusion among its followers between the Arab-Muslim present and the Western present18. For al-Jābrī, both readings are fundamentalist, as they ‘do not differ (2026) essentially from the epistemological point of view’ (al-Jābrī 1994, p. 41), thus reflecting the state of contemporary Arab thought that remains in thrall to the authority of the ‘founding fathers’, reliant on analogical reasoning (qiyās al-ghā’ib ʿalā al-shāhid), a remnant of its cultural past (al-Jābrī 2007, p. 8). This analogical method, once effective in grammar, law, and theology, has become overused and ineffective, particularly in the realm of fiqh, or religious sciences, for methodologically and scientifically rigorous demonstrations. Al-Jābrī argues that this method leads to “Every unknown object thereby became the term (referent) in absentia of an analogy, to which at all costs a term (referent) in praesentia (known) had to be related” (al-Jābrī 1994, p. 45).

The tendency to overvalue the past, which is perceived as known, often takes precedence over the present and future, seen as realms of the unknown. This phenomenon echoes the return of the repressed: during times of weakness and vulnerability, the religious heritage and its associated rituals re-emerge as foundations of religious and cultural identity. As al-Jābrī notes, ‘Faced with any new challenges, (Arab thought) resorts to the mechanical mental activity of seeking ready-made solutions by relying on some “foundational belief” (al-Jābrī 1994, p. 46). To move beyond this paradigm, where the absent structure no longer dictates the assessment of contemporary knowledge and events, an epistemological break must be instituted19 “at the level of the mental act, i.e., the unconscious activity that operates within a determined cognitive field”’ (al-Jābrī 1994, p. 48). Ancient knowledge, while retained, should be contextualized and updated. In its era, this knowledge was limited by a lack of understanding of revelation and its meanings20. This intra-cultural approach allows for an internal analysis of the traditional Arab-Muslim world and the concepts that animate it, liberating the present and future from their historical shackles. This method also mitigates the risk of anachronistic judgments and misunderstandings in the present, while offering the ‘Other,’ particularly Europeans, a more nuanced comprehension of the Arab-Muslim cultural universe (al-Jābrī 1994, p. 11).

Al-Jābrī ‘s intra-cultural methodology critically examines the cognitive foundations shaping the Arab-Muslim cultural sphere. He pioneered the formalization of three cognitive paradigms that influence Arab-Muslim thought: the rhetorical or linguistic order (al-bayān) of Arab origin, the gnostic cognitive order (al-’irfān) of Persian hermetic origin, and the rational cognitive order (al-burhān) of Greek origin (al-Jābrī 1988, pp. 333–34). Of these, the rhetorical system (al-bayān) is paramount in Arab-Muslim knowledge, serving as the ‘Text that is both the object and the regulator of the exercise of indicative reason’ (al-Jābrī 1994, p. 12). This approach entails a meta-linguistic logic that emphasizes interpreting the revealed Text to derive social, natural, logical, and ontological laws, rather than relying solely on reason. In this framework, reason itself conforms to the Text’s logic, adapting to its fluidities and rigidities (al-Jābrī 1994, p. 12). Knowledge thus relies on analogy, positioning the ‘unknown’ in the context of the ‘known’ (qiyās al-ghā’ib ‘alā al-shāhid) (al-Jābrī 1994, p. 12). This methodology offers a scientific, rational, and critical approach to engaging with traditional heritage. Notably, by focusing on the rhetorical and linguistic aspects, namely al-bayān, this approach aligns with the Mu’tazilite perspective, which emphasizes the symbolic in relation to the signifier.

Considering the world, space, and time from a textual viewpoint as “discontinuous particles continuously woven by divine providence” (al-Jābrī 1994, p. 12) leads to a unique form of interpretation. This method, similar to the textual analysis techniques in linguistics as proposed by R. Jakobson and M. Bakhtin21, involves more than just analyzing sentences. It encompasses elements that might initially seem disparate and unrelated (Adam 2008, p. 9). This broader, more inclusive approach allows for a deeper exploration of meaning, viewing texts as complex, interconnected tapestries rather than simple strings of sentences.

In delving into the Qurʾānic revelation, al-Jābrī confronts the formidable challenge of interpreting a text that is not only intricate and multifaceted but also steeped in religious authority and tradition, as Eco notes: “There is always an authority and a religious tradition claiming the keys to its interpretation” (Eco 1990, p. 110). Aware of the complexities, al-Jābrī begins his book Introduction to the Qurʾān with a commitment to neutrality and objectivity. His goal is to render the text contemporary, aligning it with the moment of its reception and comprehension. Methodologically, al-Jābrī ’s analysis traces the Qurʾānic text in relation to the context of its revelation, its interconnections with the Prophet’s biography, and its ties with other monotheistic faiths. This approach underscores the significance of the historical dimension of human experience in his analytical framework.

Al-Jābrī ‘s critique addresses the widely accepted dogma of the Prophet’s illiteracy, a belief so deeply ingrained in the Muslim psyche that it has become an unassailable tenet of the faith. Central to this belief is the concept of i’jāz22, a notion predicated on a sign-miracle. The intricate relationship between the signifier and signified of this concept was ontologically structured two centuries post Qurʾānic writing, coinciding with the compilation of the major hadith volumes. Al-Jābrī views this as a cognitive barrier that requires to be deconstructed. To this end, he analyzes the signifier ummī, seeking to disentangle the symbolism that many Muslims revere. In the Qurʾān, ummī appears in six verses. Its translation into French varies between “people without the Book”23 and “illiterate”, contingent on the contextual implications of each occurrence24.

The term “illiterate”, ummī, is addressed in its linguistic, lexicographical, and grammatical determinations. The idea is to discern the meaning intra-textually but also extra-textually, as al-Jābrī invokes in his approach the accounts of the “official” biographers of the prophet25 and the collection of hadiths in direct connection with the question of Muḥammad illiteracy. “In our approach”, he specifies, “we first examine the contributions of the traditionalists and exegetes, then we try to develop an objective understanding of the Qurʾān’s contribution on this subject, and finally, we cast a look on a set of facts and testimonies concerning the subject” (al-Jābrī 2006, p. 78). In his methodical analysis, al-Jābrī maintains a critical perspective as he examines the work of traditionalist scholars, especially focusing on Ibn Isḥāq’s (d. 768) biography of the Prophet and the collection of hadiths by al-Bukhārī (d. 870)26. His deep exploration of the term ummī is noteworthy, as he traces its occurrences and interactions across various verses. Through this process, al-Jābrī seeks to decipher the diverse connotations of ummī by examining its different signifiers, thereby shedding light on its developmental trajectory within the sociocultural context of the Arabs of that era. Further enriching his study, al-Jābrī meticulously analyzes the initial five verses of Surah 96. His investigation into the usage of the verb “read” in these verses is particularly insightful, as he delves into its semantic implications and how they contribute to the foundational aspects of the text27.

Confronted with the divine command to “read”, al-Jābrī discerns two distinct interpretations, each offering a unique response to this celestial injunction. The first is encapsulated in the query “What shall I read?” This response inherently asks, “What is to be read?” or “What should I read?” In contrast, the second reaction is denial: “I do not know how to read”. Al-Jābrī argues that in the first scenario, the question implies a quest for content to read, rather than an admission of illiteracy. This interpretation is supported by the accounts of Ibn Isḥāq and al-Bukhārī, where the Prophet’s response is seen as seeking guidance on what he is expected to read, not as a confession of his inability to read. Al-Jābrī further clarifies that the act of reading in this context does not imply the literal deciphering of a written text, like a book or manuscript. Nor does it refer to simply repeating the words inspired by the Archangel Gabriel to Muḥammad. If the latter were the case, the command would likely have been “repeat” instead of “read”. This distinction is crucial in understanding the nuances of the command and its significance in the Islamic tradition.

By meticulously analyzing the chronological sequence of the occurrences of ummī and ummiyyūn in the Qurʾān, al-Jābrī arrives at a compelling conclusion. He observes a consistent contrast in numerous verses: on one side are the ummī and ummiyyūn—groups without a previously revealed sacred text—and on the other, the People of the Book, specifically Jews and Christians. The latter possess sacred texts—Jews with the Torah and Christians with the Bible, particularly the Gospel—while the ummī and ummiyyūn do not. This absence of a revealed book is precisely what designates the ummī and ummiyyūn as such. According to al-Jābrī, the Qurʾān ’s revelation serves to bridge this gap, positioning it as their own divine scripture (al-Jābrī 2006, p. 72).

Al-Jābrī’s examination of the word ummī reveals a fascinating divergence between its lexical meaning in Arabic dictionaries and its usage in the Qurʾān. In Lisān al-ʿarab28, the term is primarily defined as “native, one who is akin to his nation or umma, not educated in reading from a book”. This definition paints a picture of an individual who, like his nation or umma, or akin to his mother, umm, remains unlettered, preserving the purity of his birth state (al- Jābrī 2006, p. 72). Such lexicographical interpretations perpetuate a myth within the Muslim imagination, fueling the belief in the Qurʾān’s miraculous inimitability—i’jāz. Al-Jabri’s work is a deliberate effort to challenge this dogma of i’jāz by scrutinizing the notion of illiteracy. To this end, he embarks on a rigorous semiotic study of the Qurʾānic text, delving into the cultural connotations surrounding ummī’. His analysis is not just a commentary on the term’s usage; it is an endeavor to articulate and reconstruct its various meanings as they appear throughout the Qurʾān. Al-Jābrī’s approach is guided by the pivotal question ‘What does the term mean?’ This perspective seeks to transcend the literal interpretations born from a linear reading of the text, which typically hinges on the question ‘What is it?’

In his approach, al- Jābrī highlights the term’s contrasting sense against the People of the Book, aiming to dispel the intricate speculations that link the quality of being ummī to the miraculous nature of the Qurʾān (al-Jābrī 2006, p. 92). He suggests that the term, traditionally seen as indicating the Prophet Muḥammad’s illiteracy, has been subject to various interpretations over time, impacting the understanding of the Qurʾān ’s origin and its perceived miraculous qualities. Al- Jābrī delves into the historical and linguistic shifts that have shaped this term, underlining its multifaceted nature in Islamic discourse.

Toward the conclusion of his chapter, al-Jābrī cites the theologian Ibn Taymiyya (d. 1318), drawing a parallel with his analysis. Ibn Taymiyya acknowledges a lexicographic shift in the meaning of the term, leading to the mythical perception it holds today. He argues that ummī originally referred to someone who neither reads nor writes any Book, emphasizing a linguistic departure from its roots, which are not found in the Arabic language. This interpretation challenges the conventional understanding and invites a reevaluation of the Prophet’s educational background and the nature of his revelations.

In a similar vein, Abū Zayd (1993, p. 53) aligns with this perspective, providing a comprehensive analysis that goes beyond mere linguistic interpretation. He explores the broader implications of this term in the context of Islamic theology and the historiography of the Prophet Muḥammad. Abū Zayd examines how the evolving understanding of ummī has influenced Islamic thought and practice, suggesting that these shifts in interpretation can offer fresh insights into the Qurʾān ’s teachings and the role of the Prophet.

By comparing the approaches of Al-Jābrī and Ibn Taymiyya, we observe a common thread in their efforts to demystify and contextualize a key Islamic term. However, it is particularly striking to draw a parallel between Al-Jābrī, who is known as a left-wing militant in addition to being a scholar, and Ibn Taymiyya, a conservative theologian.

4. Nasr Ḥāmid Abū Zayd: Reframing Qurʾānic Interpretation with Enunciative Linguistics

Nasr Ḥāmid Abū Zayd embarked on a profound exploration of Qurʾānic textual analysis beginning in Abū Zayd (1981) with his seminal article “Hermeneutics and the Problematics of Text Interpretation”29. His linguistic and philosophical approach unfolded through numerous publications centered on the discourse of the Qurʾān and the ways it is received. Abū Zayd’s entire body of work contributes to the formation of a text theory that critically examines Qurʾānic enunciation. His primary aim is to challenge the prevailing traditionalist interpretations within the Arab-Muslim context, thereby paving the way for contemporary readings that align with the historical context of their interpretation. Drawing inspiration from European linguistics of enunciation and philosophy of language, Abū Zayd endeavors to establish a text theory that connects with both the wider Arab-Muslim literary corpus and the Qurʾān in particular. By treating the Qurʾān as a literary text, Abū Zayd opens the door to understanding its meanings in an unconstrained and limitless manner.

In Abū Zayd’s seminal work, the linguistic status of the Qurʾānic text is pivotal, focusing on the figure of the addressee or recipient, a concept he expounded in his influential book Mafhūm al-naṣ dirāsah fī ʿulūm al-Qurʾān (The Concept of the Text: A Study in the Sciences of the Qurʾān). This work, published in 1991, lays down a theoretical and practical framework for analyzing the Qurʾānic universe as a textual arrangement, perpetually open to contemporary reading and interpretation. Within the Arab-Muslim sphere, The Concept of Text forms the foundation for a textual theory of the Qurʾān, centering on the intricate relationship between ‘the subject, the signifier, and the Other’ (Barthes 1974, p. 9).

The notion of the Qurʾān as a dynamic text gained prominence, particularly with his 1992 publication, Naqd al-khiṭāb al-dīnī. In this work, he addresses the interplay between the immutable and the evolving aspects of religious texts. Abū Zayd postulates the Qurʾān as ‘immutable in its materiality and changing in its meaning’ (Abū Zayd 1999, p. 181). He thereby distinguishes between signification and meaning; the former being ‘the result of a reading deferred from the time of the text’s creation’ (Abū Zayd 1999, p. 85), while the latter is ‘what the texts signify at the time of its creation, usually posing little issue for the original recipients’ (Abū Zayd 1999, p. 84). Abū Zayd’s textual grammar diverges sharply from the analogies used by traditionalists, incorporating the socio-historical context essential for textual coherence30. His approach seeks to distance itself from the dominant fundamentalist reading that detaches ‘the Text from history, attempting to apply an abstract text to an abstract reality’ (Abū Zayd 1999, p. 18). This interpretive perspective emancipates the Qurʾānic text from a singular, timeless meaning, fostering a concept of plural meanings emanating from the Qurʾān ’s polysemic space. Consequently, the notion of a text embodying a definitive, eternal sense that authoritatively dictates rules is now open to question.

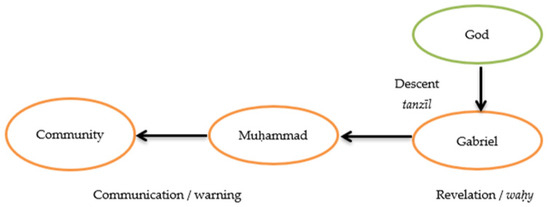

In Naqd al-khiṭāb al-dīnī, Abū Zayd compellingly illustrates the impact of structural linguistics on his analytical approach. In the section titled ‘Text’, he develops the principle of ‘Signifiance’31. This notion opens the perspective of the dialogic and polyphonic dimension of the Qurʾānic text, whose unity of enunciation cannot be summarized by the simple equation of a speaker addressing an addressee. The question of ‘who speaks’ and ‘to whom the speech is addressed’ is central to Abū Zayd’s reading of the Qurʾān32. This approach rigorously excludes theological biases, focusing instead on the semiotics of the Qurʾānic text. In the first part of The Concept of the Text, titled ‘the concept of revelation’ (mafhūm al-waḥy), Abū Zayd delineates a dynamic communication model (Figure 1) involving the figures of the speaker, intermediaries, the message, the recipient community, and interpretation. This model highlights the intricate and multifaceted nature of communication within the Qurʾānic context.

Figure 1.

Waḥy: From revelation to communication.

This semiotic framework (Figure 1) underscores the transformative journey of the message, beginning with the act of revelation and evolving into a form of communication and warning. In this process, Muḥammad transitions from a mere recipient to a conscious speaker, fully cognizant of his mission. This metamorphosis of the message, as Mégarbané describes it, involves its detachment from the ‘confined horizon of its first recipient’, thereby transforming it into a discourse aimed ‘at each existing entity in particular, arguing ad hominem against it’ (Mégarbané 2015, p. 98). Toshihiko Izutsu’s perspective on revelation offers a complementary lens to this discussion. He posits that, although revelation transcends comparison and defies traditional analysis, it can be approached as an exceptional form of human speech. This approach, considering revelation as an ‘extreme, or rather, exceptional case of general linguistic behavior’, aligns with the transformative narrative of the message in the Islamic tradition (Izutsu 1959, p. 127). By regarding the act of revelation not just as a divine event but also as a unique linguistic phenomenon, the analysis of this discourse becomes feasible, allowing for a deeper exploration to ‘scrutinize its existential intention’ (Mégarbané 2015, p. 98). Thus, integrating Izutsu’s view, the message’s significance is discerned beyond its initial context, highlighting the dynamic interplay between divine communication and human linguistic interpretation. Both Mégarbané and Izutsu elucidate a congruent analytical framework, suggesting that the message’s transformation transcends its initial divine revelation, positioning it within a broader semiotic and linguistic context that is universally applicable.

Abū Zayd’s proposed schema stresses the paradoxical relationship between presence and absence. This movement between these two poles can be grasped at the level of the divine figure and its position relative to its recipient, Muḥammad, through the intermediary of the archangel Gabriel, ‘at once visible and invisible, audible and inaudible, available and out of reach’ (Mégarbané 2015, p. 97). The prophet is at the heart of this movement, both as the receiver of a secret and ineffable revelation and as the speaker of a clear and lucid message.

This oscillation between the absent and the present belongs to the mechanism of writing (Mégarbané 2015, p. 98), serving to actualize what is otherwise an absent structure. Like a literary text33, the interpretive progression involves distinguishing between the intention of the historical author—not always explicit in the text—and the narrative voices, as well as the role of the recipient. Analyzing the aesthetic distances among these elements implies the methodological question of ‘who speaks?’ This approach, which Abū Zayd frames as a poetics of the text, challenges rigid readings that claim to directly discern the divine intentions in the Qurʾān (Abū Zayd 1999, p. 156). The text, as a site of transcendental intentionality, becomes a source of eternal truth and discourse. However, as Abū Zayd notes, ‘from the moment of its revelation—its recitation by the prophet—the Qurʾān transitions from divine text to human interpretation. The prophet’s understanding of the text is the first stage of its dynamic interaction with human reason’ (Abū Zayd 1999, p. 186). Yet, the fundamental question remains unresolved: whether Muḥammad, the primary recipient, received the revelation and its meaning. Abū Zayd’s schema does not comment on the transition of revelation as indescribable content into communication structured according to human language. The challenge for the Abū Zayd remains in the play of meanings presented by the Qurʾānic text and the shifts it enacts within its space.

This perspective on the dynamic and evolving nature of textual interpretation finds a resonance in Muḥammad Shaḥrūr’s significant work Al-Kitāb wal-Qur’ān. Qirā’ah mu‘āṣirah (The Book and the Qurʾān. A Contemporary Reading), with its third edition released in 2016 (Shaḥrūr 2016). Shaḥrūr conducts an in-depth analysis of how revelation transforms into a message, relying on linguistics, logic, and rhetoric, highlighting the historical context of the latter to make it more tangible and relatable to the recipient community. He views the message’s meaning as dynamic, evolving with the temporal and cultural context of its reception, adhering to the principle that meaning should provide answers that the recipients can internalize as their own. While the message as conveyed by Muḥammad is seen as largely subjective and relative, Shaḥrūr posits that prophecy, as internalized content, is objective, timeless, and ongoing34.

The inquiries raised by Muḥammad ʿĀbid al-Jābrī and Nasr Ḥāmid Abū Zayd represent a significant stride toward carving out a realm for independent thought in Islamic scholarship, liberated from the constraints of established religious and ideological presuppositions. Their endeavors to engage with the Qurʾānic text outside the bounds of traditional dogma mark a pivotal moment in the discourse on religious tradition, which is often ontologically constrained within the realms defined by Islamic dogma.

This article has showcased the innovative hermeneutical methods employed by these two scholars in reinterpreting the Qurʾān. Despite sharing a common goal of understanding the Qurʾān through a humanistic and linguistic lens, their approaches exhibit distinct characteristics and implications. Al-Jābrī’s methodology, deeply rooted in the rationalist tradition, emphasizes the rhetorical and linguistic aspects of the Arabic language, particularly al-Bayān. His analysis of the Qurʾān ’s composition and historical context challenges traditional interpretations that adhere to the fact that “the Qurʾān text is considered as the verbatim Word of God essentially different from human language (…) which language is thus operating outside of history and possessed of a fixed meaning that is, in principle, not dependent on human modes of perception and analysis”35.

In contrast, Abū Zayd’s approach is characterized by an emphasis on enunciative linguistics and semiotics, treating the Qurʾān as a dynamic text that interacts with the reader’s sociocultural contexts. His methodology integrates contemporary linguistic theory, focusing on the interplay between the signifier and the signified and the reader’s role in constructing meaning.

Historically, those attempting a rational, unprejudiced examination of the Arab-Muslim heritage, like al-Jābrī and Abū Zayd, have faced severe backlash, not just theologically, but also politically and socially. Influential works such as Islam and the Foundations of Political Power36, On pre-Islamic Poetry37, and The Second Message of Islam38, have incited intense reactions, sometimes even leading to dire consequences like death sentences.

In the cases of al-Jābrī and Abū Zayd, their resistance to dogmatic interpretation, despite affirming their faith, was evident in their writings. Abū Zayd’s Naqd al-khiṭāb al-dīnī led to his condemnation as an apostate and a court-ordered separation from his wife. Conversely, al-Jābrī’s situation was different, often declining accolades offered by Moroccan political authorities, reflecting his independent stance.

The experiences of these scholars represent two poles: persecution for one and recognition for the other. Yet, the underlying similarity lies in their shared sense of being misunderstood, despite their profound and critical engagement with the Arab-Muslim intellectual heritage. Their contributions have not only enriched modern Islamic scholarship but also illuminated the diverse and evolving landscape of Qurʾānic interpretation in contemporary times.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For further reference in this regard, see the works of Mohammed Arkoun, Muḥammad Shaḥrūr, and Mustapha Ben Taïbi. |

| 2 | Abū Zayd distinguishes between ‘explanation’, which is past-oriented and relies on the authority of predecessors, and ‘interpretation’, which is forward-looking, focusing on future events or those with a hidden (bāṭin) meaning. Interpretation, aligning with the concept of text, implies a return to the origin. The act of interpreting is notably emphasized in the Qurʾān, appearing 17 times, in contrast to ‘explanation’, which is mentioned only once. Abū Zayd, drawing from Arabic poetry and the Qurʾān, underscores the significance of this approach in that era. This is elaborated in Chapter 5, “L’explication et l’interprétation” (At-Tafsīr, wa Ta’wīl), in Mafhūm al- naṣ: dirassa fi ‘ulūm al-Qur’ān (The Concept of Text), Al-Hai’a Al-messria Al ‘ama llkitab 1993. |

| 3 | Us and Our Tradition: Contemporary Readings of Our Philosophical Tradition, 1980, the book is a foundational introduction to al-Jābrī ‘s major works, where he thoroughly outlines his method of thought, objectives, and the conceptual tools he utilizes in his intellectual work. |

| 4 | Applying textual linguistics to the Qurʾān does not contradict the belief in its divine origin. Developing the concept of text is ultimately an effort to uncover the essence of the text that lies at the heart of our culture and the intricate interrelations between text and culture. Critique du discours religieux (Naqd al-khiṭāb al-dīnī, Cairo 1998, 4th Edition), Actes Sud 1999, p. 33. |

| 5 | The idea of the text enables Muslim society to become a ‘society of the Book’. This will have the consequence, on the one hand, of placing ‘the people in a hermeneutic situation’ and, on the other hand, allowing for a Qurʾānic reading aimed at organizing and informing society at various levels (belief systems, moral order, legal, political, etc.). Mohammed Arkoun, Ouvertures sur l’Islam, Paris Grancher, coll. «Ouvertures», p. 59. Quoted by Naïma El Makrini, Regards croisés sur les conditions d’une modernité arabo-musulmane: Muḥammad Arkoun et Muḥammad ʿĀbid al-Jābrī. Academia-L’Harmattan 2016, p. 44. |

| 6 | The Qurʾān refers to itself using the term al-kitāb, meaning the Book, as stated: “We have certainly brought them a Book which We explained with knowledge—a guide and mercy for those who believe” (Qurʾān 7:52). |

| 7 | “Contrary to religious thought, which focuses all its attention on the speaker—in this case, God—and makes Him the starting point of its speculations, we, on the other hand, place the receiver, that is, man in his historical and social conditions, at the center of interest, making it both the starting point and the destination”. Critique du discours religieux, p. 60. |

| 8 | Umberto Eco defines cooperative reading as a space where a series of relationships between the text and its recipient are established. It is not a cooperation between two entities or individuals, but rather a cooperation between two textual strategies. |

| 9 | Paul Ricoeur’s definition fully encapsulates the effort “to decipher the hidden meaning within the apparent meaning, to unfold the levels of significance involved in the literal meaning” (Ricœur 1969). Paul Ricœur, Le conflit des interprétations, Seuil, Paris 1969, p. 16. My translation. |

| 10 | “Convention and intention should precede the verbal revelation of God (Kalam Allah). Thus, one must rationally understand the nature of divine actions before proceeding to interpret His revealed word in the Qurʾān. If this is the case, thought precedes language and forms its foundation, just as divine intention is accessible through its verbal manifestations. The Mu’tazilites, therefore, seek to understand the inner word (thought) through the outer word (language)” (Salman 2017). Wassim Salman, L’islam politique et les enjeux de l’interprétation, Éditions Mimesis Philosophie 2017, p. 43. My translation. |

| 11 | One of the modes of communication mentioned in the Qurʾān is waḥy. This form of communication is established not only between the divine entity and humans but also, crucially, between the divine entity and non-humans. It is important to emphasize that, in the concept of waḥy, there is neither the idea of qawl (قول) for "speech," nor that of kitāb (كتاب) for "discourse," much less that of kalimāt (كلمات) for "word”. Waḥy represents a form of supernatural communication that actually merges the two constitutive strata of the dynamics of meaning: the signifier and the signified. By transcending this structure, waḥy constitutes a direct, instantaneous, and immediate communication, which testifies to its closeness with the divine source and the truth of what is communicated. Communication through waḥy is unilateral, as only the divine entity acts as the sender. The receiver is subjected to waḥy without the possibility of refusal. Take, for example Moses, to whome God asks to cast his staff (Qurʾān 7: 117), and manu other verses where the word is used, thus illustrating the imperative and unquestionable nature of waḥy, or the verse that mentions God inspiring bees to take the mountains as homes, among other instructions, in surah An-Naḥl (The Bee), verse 68-69. The verse demonstrates the broad scope of waḥy, extending beyond human prophets to include communication with all of creation, in this case, bees, guiding them on where to dwell, gather nectar, and make honey. For further and general discussion on this topic, see Toshihiko Izutsu, God and Man in the Qurʾān. Semantics of the Qurʾānic Weltanschauung, Ayer Co Pub, 1980 (1st dd. 1964), 292 p. |

| 12 | The rhetorical function “aims to persuade humans by adorning the discourse with pleasing ornaments; it is what enhances the discourse for its own sake”, whereas the poetic function “seeks to re-describe reality through the indirect path of heuristic fiction” p. 311. My translation. |

| 13 | Al-Jābrī defines Arab reason as “the set of principles and rules from which knowledge in Arab culture proceeds”. These principles and rules do not originate from the era traditionally perceived by Arab consciousness as its beginnings, the pre-Islamic period (Jāhiliyya), but rather from a later era. This era, known as the period of codification (‘asr al-tadwīn) placed in the II/VIII and III/IX centuries, saw the cultural heritage (of Arabs from the pre-Islamic period and the formation of Arab reason and the beginnings of Islam) reproduced in such a way as to establish it as ‘tradition’, i.e., a referential framework from which Arabs would view ‘the universe, man, and history’. Introduction à la critique de la raison arabe, Éditions la Découverte. Institut du Monde Arabe 1994, p. 12. |

| 14 | Takwīn al-‘aql al-‘arabī, (La formation de la raison arabe) Markaz dirāsāt al-waḥda al-‘arabīyah, 1984; Bunyat al-‘aql al-‘arabī, (La structure de la raison arabe) al-Markaz al-Thaqāfī al-ʻArabī, 1986; Al-‘aql al-siyāsī al-‘arabī, (La raison politique en islam) Markaz Dirāsāt al-Waḥda al-ʻArabīya, 1990 Al-‘aql al-akhlāqī al-‘arabī, (La raison éthique arabe, Éditions la Découverte 2007) Beyrouth, Casablanca, Markaz dirāsāt al-wahda al-’arabia 2001. |

| 15 | Madkhal ilā al-Qur’ān al-Karīm. 1: Al-juz’ al-awwal: Fī al-Ta‘rīf bi-l-Qur’ān (Introduction to the Qurʾān), Beirut: Markaz dirāsāt al-Waḥda al-‘Arabīyah 2006; Fahm al-Qur’ān al-Ḥakīm, al-tafsīr al-wāḍiḥ ḥasab tartīb al-nuzūl (3 v.), (Understanding the Qurʾān) Bayrūt: Markaz Dirāsāt al-Waḥdah al-‘Arabīyah, 2008. |

| 16 | One of the consequences of this thought mechanism, which fundamentalists adopt, is to eliminate the historical dimension. “Every present is systematically related to the past, as if past, present, and future constituted a flattened expanse, an immobile time” (ʿĀbid al-Jābrī 1994, p. 46). My translation. |

| 17 | “This current (fundamentalist), more than any other, has dedicated itself to reviving tradition, investing it in the perspective of an excessively ideological reading, consisting of projecting an ‘ideal future,’ fabricated by ideology, onto the past; and, consequently, to ‘demonstrate’ that ‘what took place in the past could be realized in the future”. Introduction à la critique de la raison arabe, p. 34. |

| 18 | «Le dialogue autour de cet axe et l’ordre dialectique qu’il implique s’établissent cette fois entre le présent et le passé. Non point notre présent à nous, mais le présent de l’Occident européen, qui s’impose comme «Sujet-Moi» à partir duquel a lieu le regard sur notre époque, sur l’ensemble de l’humanité et, partant, comme «fond» de tout futur possible», Introduction à la critique de la raison arabe, p. 36. |

| 19 | «The epistemological break ‘has no relation to those deleterious theses which invite us to confine tradition to museums. (…) The epistemological break operates at the level of the mental act, i.e., the unconscious activity that takes place within a determined cognitive field, according to a certain order, and by means of cognitive instruments: the concepts». Introduction à la critique de la raison arabe, p. 48. My translation. |

| 20 | “The most problematic (…) is that, firstly, this ignorance of the first recipients, despite the humility that drove them to recognize it, is today promoted as a feat and a virtue, that of the salaf (predecessor), supposedly more knowledgeable than the khalaf (heir). Secondly, and more seriously, this ignorance transformed into virtue, has become the very principle of what we consider to be a false reading of the Qurʾān” (Seddik 2007). Youssef Seddik, L’arrivant du soir, Edition de l’Aube 2007, p. 31. |

| 21 | See in particular, Roman Jakobson, Essais de linguistique générale (1 et 2), Paris, Éditions de Minuit 1963 (Vol. 1), 1973 (Vol. 2), Mikhail Bakhtin, La poétique de Dostoïevski, Paris, Le Seuil, coll. ‘Points Essai’ 1970. |

| 22 | The Inimitability of the Qurʾān. |

| 23 | It is worth noting that in the Qurʾān, the term Kitāb is also replaced by the word imam (Cf. Qurʾān 36:12). |

| 24 | Regis Blachère translated it as ‘gentiles,’ meaning people who have not received books revealed by God (the Torah or the Gospel), in other words, pagans. |

| 25 | Abu ‘Abd Allah Muḥammad ibn Ishaq (circa 704–767). His biography of the Prophet, revised by the grammarian Ibn Hisham (d. 834), under ‘Al-Sira al-Nabawiya’ by Ibn Ishaq is considered the earliest source on the Prophet’s life. The translation into French, in two volumes, was completed by Abdurrahmane Badawi at Al Bouraq editions. |

| 26 | Muḥammad al-Bukhari, whose collection of hadiths, ‘Sahih al-Bukhari,’ is considered by Sunni Muslims as one of the most authentic sources of the life and sayings of the Prophet of Islam. |

| 27 | “Read in the Name of your Lord Who created! He created man from a clot of blood. Read! For your Lord is the Most Generous Who taught man by the pen, taught him what he did not know” (Qurʾān 96:1–5). It is acknowledged in authentic hadiths that the first five verses of this surah constitute the initial revelation. |

| 28 | The Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Arabic Language. It catalogs Arabic lexicology since the 9th century. |

| 29 | Nasr Ḥāmid Abū Zayd, al-Hermeneutiqā wa-Mu‘ḍilāt Tafsīr al-Naṣ (Hermeneutics and the Problem of Text Interpretation), Fuṣūl No. 3, 1981, pp. 141–59. |

| 30 | Grammar is a coding tool common to both propositional semantic information (simple sentences) and discursive pragmatic coherence (discourse). […] Much of grammatical coding unfolds in the realm of discursive pragmatics, thereby signaling the coherence of the information conveyed in its situational, inter-sentential, and cultural context. Thomas Givón, «L’approche fonctionnelle de la grammaire». Verbum 20, 3, pp. 257–88. Cited by Jean-Michel Adam, in ‘Practices, Textual Linguistics and Discourse Analysis in the Context of the 1970s’, Pratiques [Online], 169–170|2016, posted on 30 June 2016, accessed on 25 April 2018. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/pratiques/2931; DOI: 10.4000/pratiques.2931. My translation. |

| 31 | An experimental notion proposed by R. Barthes in 1974, ‘Signifiance is a process, during which the ‘subject’ of the text, escaping the logic of the ego-cogito and engaging in other logics (that of the signifier and that of contradiction), struggles with meaning and deconstructs (‘loses’) itself; signifiance, and this is what immediately distinguishes it from signification, is thus a work, not the work by which the subject (intact and external) would try to master language (for example, the work of style), but this radical work (it leaves nothing intact) through which the subject explores how the language works and undoes him as soon as he enters it (instead of supervising it): it is, if you will, ‘the endless possibilities in a given field of language’’ Roland Barthes, Théorie du texte, p. 5. My translation. |

| 32 | “The main function of language is the communicative function. This function presupposes a relationship between a speaker and an interlocutor, a sender and a receiver. While it goes without saying that these two functions are inseparable, the informative function of the text—i.e., the message—cannot be separated from the linguistic system in which it is expressed. And therefore, this function can only be considered in relation to culture and reality”. Critique du discours religieux, p. 29. My translation. |

| 33 | “‘(…) there are different types of meanings. (…) language is endowed with a particular semiotics, governed by specific laws. And if we still find a certain pleasure in reading literary texts produced more than 15 centuries ago, it is because these texts still have the capacity to produce meaning. If this is the case for texts created by humans, how could one imagine that religious texts, so well received, venerated for centuries and centuries, extensively studied by various disciplines, would cease to interest us or lose their significance for us?!’ (Abū Zayd 1999, p. 44)”. My translation. |

| 34 | Muḥammad Shaḥrūr, Al-Kitab wal Qurʾān. Qira’a mu’asira, Syria, Damascus, al-ʾāhālī lilṭibāʿah wa al-nashr wa al-tawzīʿ, 1990. |

| 35 | Adis Duderija, Traditional and Modern Qurʾānic Hermeneutics in Comparative Perspective, International Qurʾānic Studies Association, 2015. https://iqsaweb.org/2015/03/23/duderija_hermeneutics/ (accessed on 23 January 2024). |

| 36 | Ali Abderraziq (1888–1969), a judge in Mansura (Egypt), was a theologian educated at Oxford and Al Azhar. |

| 37 | Taha Hussein (1889–1973) was an Egyptian essayist and literary critic. |

| 38 | Mahmoud Mohamed Taha (1909–1985) was a Sudanese jurist and theologian. His work ‘An Islam with a Liberating Mission’ has been reviewed by Maurice Borrmans. More information can be found at http://www.ifao.egnet.net/ (accessed on 23 January 2024). |

References

- Abū Zayd, Nasr Ḥāmid. 1981. Al-Hermeneutiqā wa-Mu‘ḍilāt Tafsīr al-Naṣ. (L’herméneutique et le problème de l’interprétation du texte). Fuṣūl N° 3. Available online: https://archive.alsharekh.org/Articles/133/14106/303599 (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Abū Zayd, Nasr Ḥāmid. 1993. Mafhūm al-Naṣ. Dirāsah fī ʿUlūm al-Qurʾān (The Concept of the Text: A Study in the Sciences of the Qurʾān). Le Caire: Al-hai’a al-messria al ‘ama llkitab. [Google Scholar]

- Abū Zayd, Nasr Ḥāmid. 1999. Critique du discours religieux (Naqd al-Khiṭāb al-Dīnī), 4th ed. Caire: Actes Sud. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, Jean-Michel. 2008. La linguistique textuelle. Paris: Armand Colin. [Google Scholar]

- al-Jābrī, ʿĀbid Muḥammad. 1980. Naḥnu wal-turāth: Qirā’āt mu‘āṣirah fī turāthinā al-falsafī (Nous et la tradition. Lectures contemporaines de notre tradition philosophique), 6th ed. Beyrouth: Casablanca, al-Markaz al-Thaqāfī al-‘Arabī, Le Centre Culturel Arabe. [Google Scholar]

- al-Jābirī, ʿĀbid Muḥammad. 1988. Takwīn al-ʿAql al-ʿArabī, (The Formation of Arab Reason). Beyrouth: Markaz Dirāsāt al-waḥdah al-ʿarabīyah, al-ṭabʿah al-thālithah. [Google Scholar]

- al-Jābrī, ʿĀbid Muḥammad. 1994. Introduction à la critique de la raison arabe. Traduction de l’arabe et présentation par Ahmed Mahfoud et Marc Geoffroy. Paris: Éditions la Découverte & Institut du Monde Arabe. [Google Scholar]

- al-Jābrī, ʿĀbid Muḥammad. 2006. Madkhal ilā al-Qurʾān (Introduction au Coran). Beyrouth: Markaz dirasat al-wahda al-’arabiyya. [Google Scholar]

- al-Jābrī, ʿĀbid Muḥammad. 2007. La raison politique en islam, hier et aujourd’hui. Traduction de l’arabe par Boussif Ouasti, avec la participation de Adelhadi Drissi et Mohamed Zekraoui. Coordination et revue par Ahmed Mahfoud. Paris: Éditions la Découverte. [Google Scholar]

- Arkoun, Mohammed. 1991. Lectures du Coran. Tunis: Alif-Editions Méditerranée. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1974. Théorie du texte. Paris: Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 1967. L’écriture et la différence. Paris: Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, Umberto. 1990. Les limites de l’interprétation. Paris: Grasset. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, Umberto. 1995. Lector in fabula. Paris: Grasset. [Google Scholar]

- El Makrini, Naïma. 2016. Regards Croisés Sur Les Conditions D’une Modernité Arabo-musulmane: Mohammed Arkoun et Mohammed Al-Jābrī. Paris: Academia-L’Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- Izutsu, Toshihiko. 1959. The Structure of The Ethical Terms in The Koran. Tokyo: The Keio Institute of Philological Studies, Keio University. 275p. [Google Scholar]

- Lacan, Jacques. 1966. Écrits. Paris: Le Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Laroui, Abdellah. 1973. Al ‘arab wa al fikr at-tarikhi (les Arabes et la pensée historique). Beyrouth-Casablanca: Al markâz at-thaqâfîal-’arabî. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara, S. Danielle, and Walter Kintsch. 1996. Learning from Texts: Effects of Prior Knowledge and Text Coherence. Discourse Processes 22: 247–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mégarbané, Patrick. 2015. Le Livre Descendu. Essai d’exégèse coranique. Norderstedt: Books on Demand, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ricœur, Paul. 1969. Le conflit des interprétations. Paris: Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Ricœur, Paul. 1975. La métaphore vive. Paris: Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Salman, Wassim. 2017. L’islam politique et les enjeux de L’interprétation: Nasr Ḥāmid AbūZayd. Sesto S. Giovanni: Éditions Mimésis. [Google Scholar]

- Seddik, Youssef. 2007. L’arrivant du soir. La Tour-d’Aigues: Édition de l’Aube. [Google Scholar]

- Shahrūr, Muḥammad. 2016. al-Kitāb wa-al-Qur’ān: Ru’yā Jadīdah. Bayrūt: Dār al-Sāqī. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).