Abstract

This article aims to elucidate the origin of the merchant scene within the Easter drama, which can, by extension, be interpreted as representative of the entire Visitatio Sepulchri. Given that the troper-proser Vic 105 is the oldest attestation of the scene, we have used this manuscript as our starting point. Through a critical edition of the first nine stanzas of the drama, we propose a multidisciplinary working hypothesis that combines tools from reception history and cultural transfers studies with more traditional methods of stemmatics. As part of an ongoing project, we present two types of results: those that are well-supported by strong evidence, and others in the form of plausible hypotheses, awaiting further data to be substantiated.

1. Introduction

The events following the Passion and death of Christ were, from the very beginning, the most decisive and central in Christianity. For instance, in the Preface to a masterful essay by Heinrich Schlier, Joseph Ratzinger/Benedict XVI highlights this as a fundamental challenge for interpretation: “Schlier was perfectly well aware that Jesus’ Resurrection from the dead represents a borderline case for exegesis; but it becomes particularly clear in it that the interpretation of the New Testament always deals with borderline problems if one aims at reaching the core of the question. The faith in the Resurrection of the New Testament writings faces the exegete with an alternative that demands a response from him” (Schlier 2008, p. 6). Medieval Christians faced precisely this same type of exegetical challenge and demand for a response when, in the transition from Easter night to morning, they sought to deepen their understanding of passages concerning the Resurrection, such as Mark 16:1–2 or Luke 23:55–56 and 24:1–3, where the holy women, devastated by grief, journeyed to the tomb to anoint the body of Christ. Whether through liturgical actions, chants, or iconography, whether explicit or implicit, every detail of the Gospel narrative became of utmost importance for approaching these central mysteries within the History of Salvation.

In light of this reality, we encounter the dramatized scene and visual representation of the sale of ointments. This action is implicitly referenced in the statement from Mark 16:1: “When the Sabbath was over, Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome bought spices, so that they might go and anoint him.” During the transition from the 11th to the 12th centuries, this moment in the Gospel became a motif and an opportunity to enhance, through rhetorical ornatus—which implies both embellishment and explanation (Tello Ruiz-Pérez 2007)—the still-emerging Easter scenic celebrations at the altar of the Visitation of the Sepulchre (dialogued tropes, performances on a small scale, etc.), which date back at least to the ninth and tenth centuries (given the extensive historiography on this subject, we refer, for practical purposes, to the updated bibliographical synthesis and discussion by Norton 2017a). Within this dynamic of explanatory enrichment and deepening, the most significant and notable contribution of the Mercator scene lies, as Berthold describes, in how it “opened the door to one of the traditional stock characters of the popular theater—the Mercator—apothecary, quacksalver, medicaster, and pillroller of burlesque and mime. He did not have to be invented, but simply brought into the play […] A low sales table, a pair of scales, spice boxes, and ointment pots mark the scene of this first ‘worldly’ interlude” (Berthold 1972, p. 236).

Given its widespread dissemination, complex elaborations, and subsequent reinterpretations in Pasiones, Mystères, plays, and various forms of theatrical representation—whether in Latin or vernacular languages, both within and outside the temple—the introduction of this “worldly interlude”, or, in other words, the non-biblical and profane element (pro-fanus, i.e., “outside the temple”, or more precisely, in front of it), which intertwines with the central events of the “paschal kerygma”, raises a pertinent question: can it be regarded as a distinguishing factor that demarcates the boundaries between liturgy, liturgical drama, and theater proper during the Middle Ages? (see an updated discussion in Petersen 2022). Notably, amid an increasingly pronounced process of secularization of the scene, as evidenced by many late sources, recent scholarly discussions suggest that the depiction of the spice merchant or merchants—represented with heightened dramatic and comedic elements, incorporating the customs, gestures, and typical strategies of medieval itinerant healers, apothecaries, surgeons, and quack doctors—on the path of the women to the tomb may have served as a form of efficient advertisement, almost guild-like in nature, promoting the sale of goods and services by such traders (Katritzky 2020).

Before its dramatized appearance, the scene also emerged in the realm of iconographic images, albeit with varying success in terms of its proliferation. Indeed, examples in the visual arts, illuminations, and miniatures are rather scarce, sporadic, and scattered (Réau 1957, pp. 541–42; Hofmann 1972; Lorés i Otzet 1986; González Montañés 2002, pp. 427–32). Nonetheless, its existence as an image is intriguing, as the absence of a common biblical model compels us to draw parallels or even engage in direct dialogue with the performative dimension of the scene. In this regard, its significance in art presents a privileged case study for verifying the controversial hypothesis—articulated from Mâle to Davidson—regarding a medieval dependency of image configuration on dramatic and theatrical events (for a thorough discussion of this hypothesis, see González Montañés 2002, pp. 11–31). Building on this hypothesis, a new question arises: in seeking inspiration to enrich the representation of the Easter event, could sculptors and painters of religious images have been influenced by dramatizations of the Visitatio Sepulchri that included the sale of ointments?

These key points and the questions they generate collectively highlight the need to clarify, as precisely as possible, the origin of this scene and its potential transmission routes. The earliest dramaturgical evidence of the scene in the context of Easter can be found in the Verses pascales de III Mariis of the Visitatio Sepulchri, preserved in the troper-proser Vic 105 as a late 12th-century addition to a manuscript dating from the late 11th or early 12th century. Thus, it seems logical to consider the context in which this manuscript was used as our starting point and foundation.

However, beyond this first Ausonian testimony—which has not always been considered by scholars—a general consensus has persisted: “the theory that the Visitatio sepulchri provided the initial impetus, from which the merchant scene grew quasi-organically from the liturgy, and that it only ‘gradually abandoned also the Latin of the liturgy in favour of the language of ordinary life’, is widely accepted as a convenient truism” (Katritzky 2007). In other words, this is a liturgical “convenient truism” which, moreover, tends to attribute the origin of the scene—fons et origo—exclusively to a creative tradition of literary origin. This theory stems from Meyer’s pioneering explanation of a hypothetical Zehnsilberspiel, which he believed originated in present-day France and whose words and actions were supposedly integrated into the dramatic framework of a Visitatio (Meyer 1901, pp. 106–20). Thus, even without fully taking into account early non-liturgical testimonies relevant to our scene—such as the Sponsus in Pa 1139 (e.g., Dürre 1915; Young 1933; Donovan 1958; Romeu Figueras 1963; De Boor 1967; Castro Caridad 1997, 2019)—or extrapolating the scene’s emergence outside the liturgical sphere as a Ludus Paschalis, based on the text’s inherent complexity (e.g., Nicoll 1931; Warning 1974; Lipphardt 1975–1990; Dronke 1994), this literary thesis has generally proven inadequate in delineating fundamental aspects, such as its genetic relationship to liturgical action.

Amid this extensive array of hypotheses and speculation regarding the origins of this scene from strictly philological or theatrical perspectives, relatively few comprehensive studies have emerged from the field of musicology. Notable among these are investigations addressing distribution, developmental processes, and structure (e.g., Schuler 1951; McShane 1961; Moore 1971; Smoldon 1980; Rankin 1981, 1989; Sevestre 1987; Evers and Janota 2013). Nevertheless, with a few remarkable exceptions (Norton 1983, 2017b; Batoff 2013; Eberle 2019, 2023), studies focusing on how melodies may have been generated and their function within their liturgical context remain nearly non-existent.

Our aim here, drawing from the evidence provided by a combined iconographic, philological, and musicological approach, is to address this gap concerning the origin of the merchant scene and the motif of ointment sales. We situate this inquiry within a framework of liturgical dependency and connection—not merely incidental due to its presence in Vic 105—with the Matins of Easter Day, as evidenced by the reuse of melodic materials and the scene’s dramatic placement within the rite. Geographically, this scene was first dramatized and subsequently depicted iconographically, based on the scenographic model of the Visitatio Sepulchri. We demonstrate that the introduction of this non-biblical scene first occurred in Catalonia, specifically within the area of influence comprising Vic–Ripoll, Girona, and Sant Cugat del Vallés, likely between the late 11th and early 12th centuries. Although the drama was not copied in Vic until the late 12th century, the Vic–Ripoll nucleus had already emerged as a prominent center for liturgical song composition from an earlier period (see, e.g., Tello Ruiz-Pérez 2016). Therefore, it is reasonable to suggest that this scene may have originated at Vic Cathedral.

To achieve this, our methodology first involved examining the overall structure of the drama as it appears in Vic 105, and the intrinsic characteristics presented in the first nine stanzas, which encompass the dialogue between the merchant and the holy women. We then used the testimony of customaries and chapter charters to elucidate the liturgical context in which the Vicenzan drama unfolds, aiming to establish possible relationships with preceding and succeeding chants. Following this, through a critical edition of all readings and variants of the nine stanzas depicting the sale of ointments—found across 42 manuscripts and fragments, totaling 47 versions—we traced their potential dissemination routes from the Catalan area. Lastly, we juxtaposed these findings on transmission with the sporadic dissemination of the few available iconographic testimonies, in order to determine in which cases a connection to the scene exists and in which cases the theme of the image represents a spontaneous and occasional manifestation.

2. The Visitatio Sepulchri of Vic 105

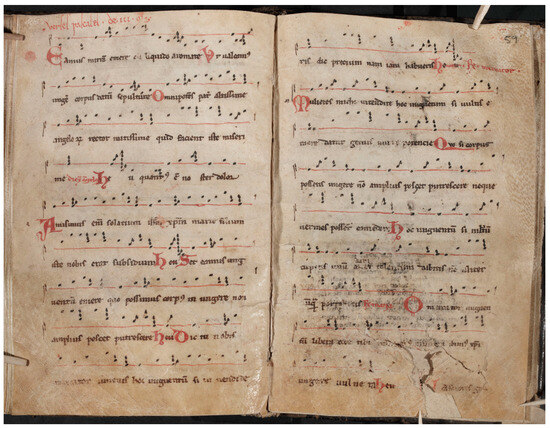

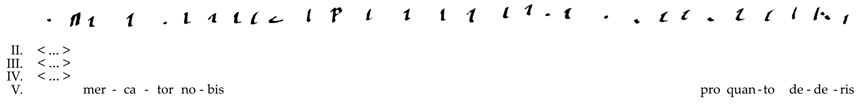

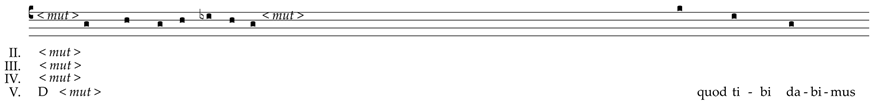

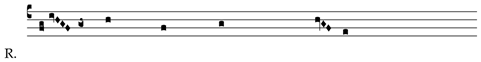

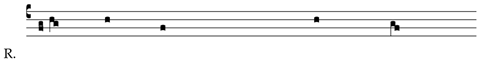

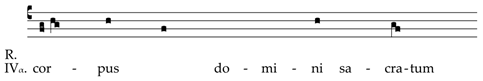

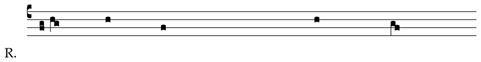

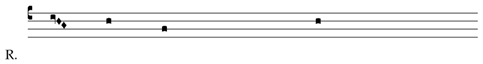

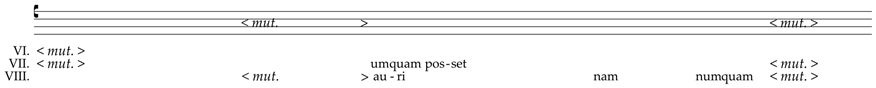

Vic 105 is a troper-proser from Vic Cathedral, with the main body copied during the first quarter of the 12th century (codicological analysis in Gros i Pujol 1999, pp. 44–56; 2010). However, the section of interest to us (Figure 1), located within the eighth booklet between folios 58v and 63r, was added later—towards the end of the 12th century—and includes several palimpsests, with rubrics dating from the 15th century (Gros i Pujol 1999, pp. 44–45, 51–53; Castro Caridad 1997, pp. 111–12, 247; 2019, p. 144; Garrigosa i Massana 2003, pp. 236–37).

Figure 1.

Vic 105, ff. 58v–59r. Merchant scene (beginning of the Visitatio).

This can be referred to as a “compositional complex” because it consists of two interconnected works that originated based on distinct moments in the events following the Resurrection. On one side is a Visitatio Sepulchri, titled “Verses pascales de III Mariis”, and on the other, an Officium Peregrini, bearing the rubric “Versus de pelegri<no>“. Additionally, the hymn Audi iudex mortuorum, with the response “O redemptor sume carnem” (Dreves et al. 1886, pp. 80–82, AH 51, No. 77), is included. This hymn, which pertains to Maundy Thursday for the consecration of chrism, appears under the rubric “Versus de crismate in cena domini”.

Although various scholarly divisions and interpretations have treated these pieces as integral parts of a broader unified Easter structure (see Petersen 2022 for a discussion and updated synthesis of this issue), the sequence of the compositions (Table 1) is as follows:

Table 1.

General design of ff. 58v–63r of Vic 105.

It can be noted that, while we place ourselves within the context of Easter—supplemented by the use of the Te Deum from Matins to conclude the Visitatio, and the addition of the hymn for Maundy Thursday (“in cena domini”)—the manuscript provides no specific references regarding which celebrations, if any, these compositions were intended to accompany (for a complete philological edition of the entire set, see Castro Caridad 1989, 1997, pp. 124–33, 252–57; for a musical edition, see Anglès 1935, pp. 276–78). We will return to this question below.

Here, we will focus exclusively on the first nine stanzas of the Visitatio, specifically the merchant scene. According to Castro’s classification based on Young’s criteria (Young 1933, vol. 1 pp. i–xv), this Visitatio would be classified as Type I, as it does not include the Apostles’ race to the tomb (Type II) or, if we consider the scene separately, the appearance of Christ to Mary Magdalene (Type III) in the guise of a Gardener (Castro Caridad 1997, p. 111). As mentioned earlier, this scene represents the first testimony to focus on the purchasing of errands preceding the sorrowful journey to the tomb, particularly concerning the ointments (Mark 16:1). Thus, the manner in which the holy women chant and express themselves is of utmost interest.

2.1. Formal Organization of the Merchant Scene

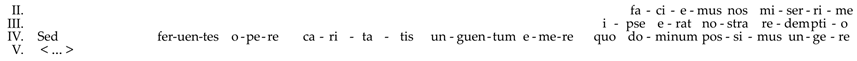

From Table 1, it can be deduced that the nine stanzas (see text and translation in Table 2) of the scene are organized into two distinct sections: (a) an exhortative introduction (stanza I) and (b) a lament (stanzas II–V, with refrain), which transitions into dialogue with the merchant (stanzas VI–IX, where the refrain returns at the end). The separation into sections, whether through poetic and/or melodic means, implies a division regarding the materials used.

Table 2.

Text (Castro Caridad 1997, pp. 124–27) and translation (Dronke 1994, pp. 92–95) of the stanzas I–IX.

Stanza I consists of four octosyllabic verses that alternate in pairs between an iambic rhythm, featuring a proparoxytone final cadence before the caesura, and a trochaic rhythm with a paroxytone cadence (8pp, 8p, 8pp, 8p),1 employing a rhyme scheme of aa’aa’—consonant between the first and third lines and assonant between the second and fourth (Table 3). In contrast, stanzas II-IX share a common structure of three trochaic decasyllables with a proparoxytone cadence and internal caesura (4p + 6pp; 4p + 6pp; 4p + 6pp), featuring a changing aaa rhyme scheme (Table 4).

Table 3.

Poetic and melodic design of stanza I.

Table 4.

Poetic and melodic design of stanza II (=III–IX).

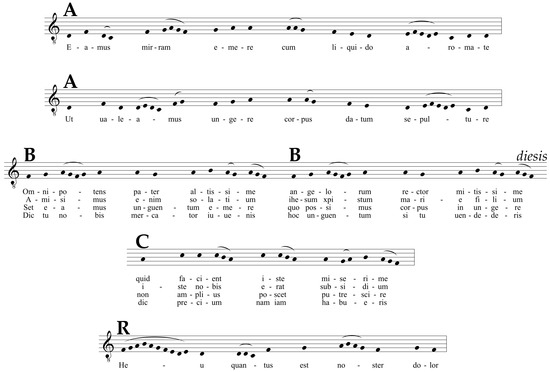

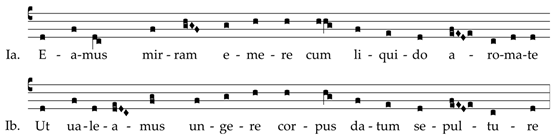

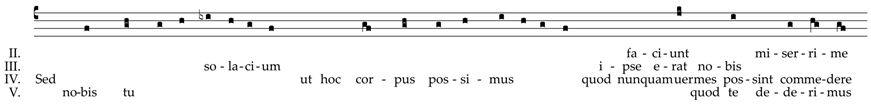

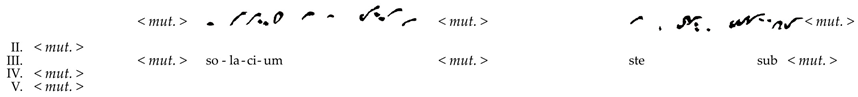

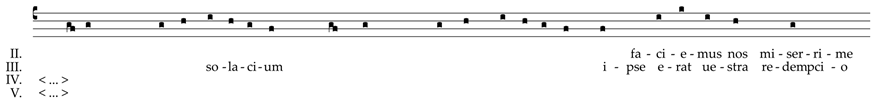

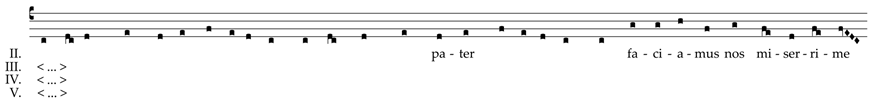

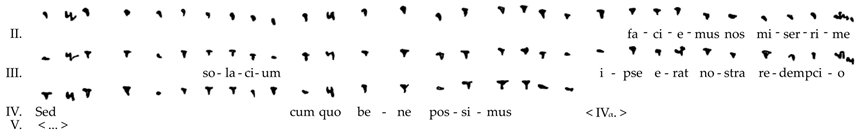

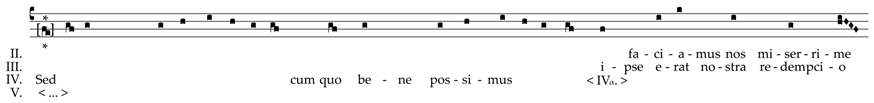

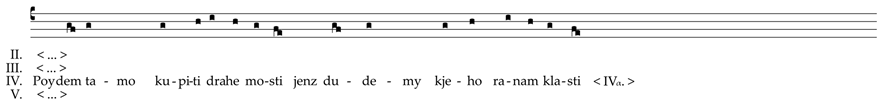

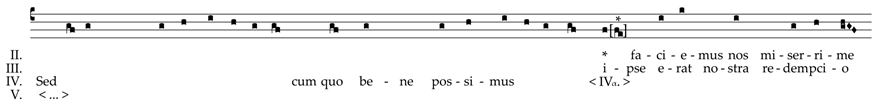

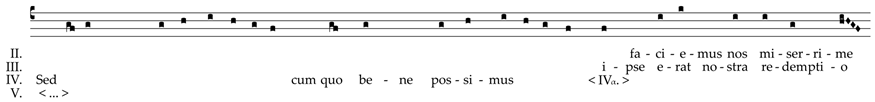

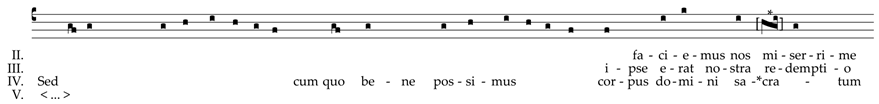

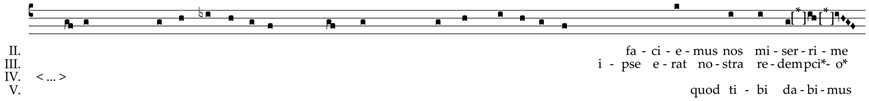

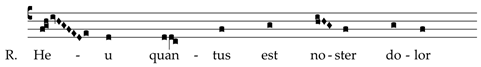

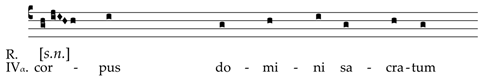

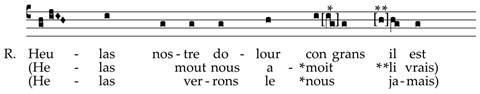

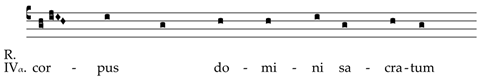

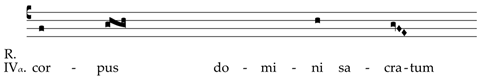

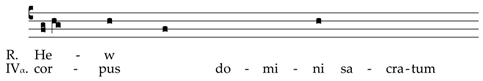

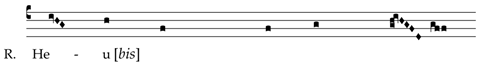

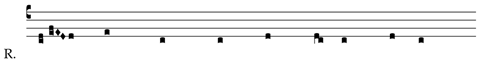

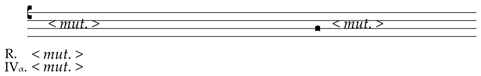

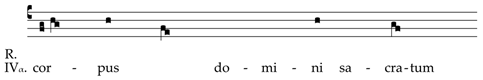

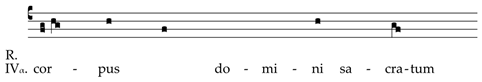

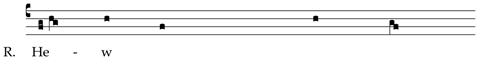

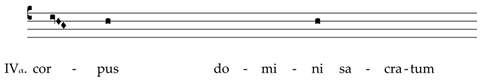

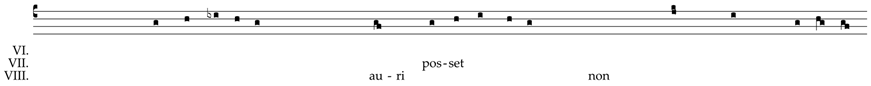

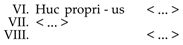

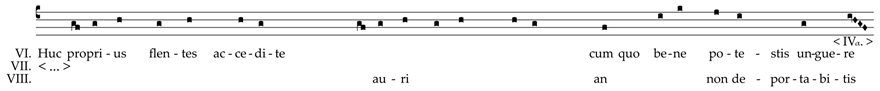

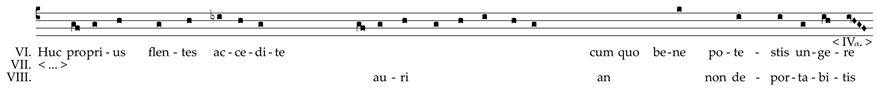

Regarding their melodies (Figure 2), the first stanza exhibits a double cursus pattern (AA), which is typical, for example, of sequences and prosulas (see, e.g., Peláez Bilbao and Tello Ruiz-Pérez 2021). The remaining stanzas, following Dante’s terminology,2 maintain a stanzaic organization of pedes cum cauda or sirma (AAB), with a diesis marking the stanza’s division between the repetition of one pes and another (AA) and everything else (B). Additionally, the refrain, associated with the interventions of the Maries (omitted when the merchant speaks), consists of a paroxytone octosyllable (8p), characterized notably by a long ascending–descending melisma spanning conjunct intervals over the interjection “Heu!” as an expression of grief. In any case, it appears to draw on common motivic materials previously introduced in the stanzas.

Figure 2.

Musical transcription 1: Formal structure of stanzas I–IX (merchant scene).

The compositional procedures employed in both sections correspond to what has come to be known as Nova Cantica or Neues Lied (e.g., Arlt 1986, 1990; Llewellyn 2018; Camprubí Vinyals 2020; and several practical cases in Peláez Bilbao and Tello Ruiz-Pérez 2024). This circumstance is particularly significant as it links our stanzas with other compositional genres, both in Latin and the vernacular. As highlighted by various musicologists, such as Sevestre, and philologists like Castro (Sevestre 1987; Castro Caridad 1997, p. 114), these stanzas, with their metric regularity—where syllable count serves as the primary metric criterion—their use of rhyme, accentual rhythm, and melodic style emphasizing steps of a third (in this case, the sequence D–F–a–c),3 clearly transport us to the compositional climate of other dramas such as the Sponsus in Pa 1139 (edited by Avalle and Monterosso 1965), to versus repertoires, Occitan passions like the Passion Didot (MacDonald 1996, 1997), or even troubadour repertoires. In this regard, it is worth noting that in the Thuringian Play of the Ten Virgins from manuscript Mühl 60/20—directly linked with the Sponsus in Pa 1139—the textual and musical reuse of stanzas II and IV from our merchant scene has been identified (Amstutz 2002, pp. 171–201); similarly, a strikingly similar melody of stanza I from Vic appears in the cansó Aissi cum es genser pascors (BEdT 406,2) by Raimon de Miraval (1160–1220), also in octosyllables (edition in Switten 1985, pp. 144–47).

2.2. Liturgical Context and Connections of the Merchant Scene

In alignment with Petersen’s observations in one of the most recent studies offering a thorough reflection on the drama of Vic 105, we must consider the following:

There are numerous problems in understanding these pages of the manuscript, which also do not indicate any specific liturgical placement for either part of the mentioned textual units [Visitatio and Peregrinus]. The way it was edited by Karl Young and Peter Dronke seems to indicate that there is altogether one connected drama […] Donovan and Castro Caridad understand the text as two dramas, an Easter morning drama and a special, innovative Peregrinus drama for Easter Monday, the Easter morning drama ending with the Te Deum before the second mentioned rubric [“Versus de pelegrino”] […]Since there are no indications telling us when the ceremony was to be performed during Easter, we cannot know.(Petersen 2022).

We believe Petersen’s argument is correct. Indeed, if we rely solely on the troper-proser Vic 105, which provides no specification regarding the liturgical location of these ceremonies, it is impossible to determine their exact placement with certainty. For this reason, Donovan, Romeu Figueras, Lipphardt, and Castro herself (see Castro Caridad 1997 for specific citations for each source below) have sought corroboration from other testimonies originating from or near Vic within the Catalan region. Although subsequent to Vic 105, these testimonies—comprising customaries or chapter charters (Vic 134, Pa nal 903, Vic s/n, Ger 20 e 3, Ger s/n, and GerS 18)—precisely identify the liturgical setting for both the “Verses pascales de III Mariis” and the “Versus de pelegri<no>.” For the sake of brevity, we will present here only the versions from the Vic manuscripts (Table 5 and Table 6), as normalized by Castro, and provide their translations accordingly.

Table 5.

Text (Castro Caridad 1997, p. 134) and translation of Officium matutinum (Vic 134, f. 17r; Pa nal 903, f. 163v; and Vic s/n, f. 52r).

Table 6.

Text (Castro Caridad 1997, p. 247) and translation in the Office of Vespers for Easter Monday (Vic s/n, f. 54v).

Let us examine the data. The evidence suggests that the Visitatio was designed to be optionally dramatized during the Matins on Easter Sunday, while the Peregrinus was intended for the Vespers of Easter Monday. Furthermore, in the case that concerns us most here—that of the Visitatio—specific instructions are provided regarding which responsory in the third nocturne should be sung before, and most importantly, that this responsory, Et valde mane (Cantus n.d., chant ID No. 006676), should be sung with verbeta—a term used in the Catalan area to denote a prosula, or a small textual addition to the melisma or pneuma of the responsory. In consequence, we conclude that the chant immediately preceding the merchant scene is the composition Christus hodie surrexit ex tumulo (edited by Bonastre i Bertran 1982, pp. 125–27).

Upon close examination of this verbeta, we immediately perceive that, mutatis mutandis, it functions almost like a theatrical annotation, imaginatively situating the context for the subsequent merchant scene and its dialogues. In a way, it appropriately prepares the participant in the liturgical service to experience and witness the events that occurred “then” and are “taking place again”—hic et nunc, one of the most significant dimensions of the liturgy—on Easter morning, as recounted in the Gospels. In fact, the responsory itself incorporates verbatim passages from Mark 16:1–2 and Luke 24:1.

However, the relevance of the verbeta is not limited solely to providing a liturgical context for our scene; it also does so stylistically, serving as a sophisticated source of melodic formulas and motivic cells. In this regard, we must not overlook that the melody of the verbeta derives entirely from the practice of fitting a text to the original melisma of the responsory “Orto iam sole, alleluia, alleluia” [“at the rising of the sun”]. Therefore, we must assume that the compositional structure inherently contains all the spiritual, poetic, and musical elements necessary to sustain the continuity with the forthcoming merchant scene.

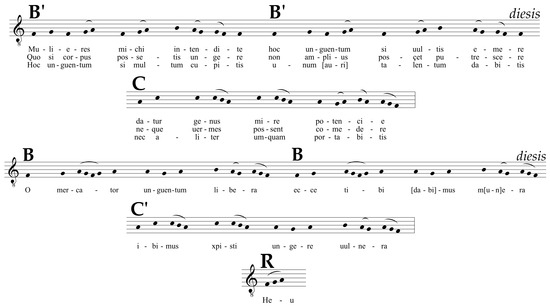

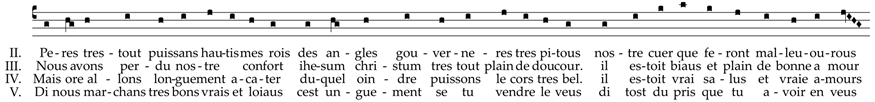

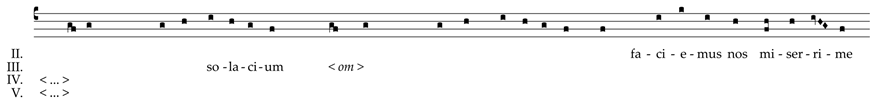

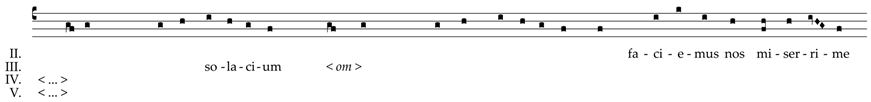

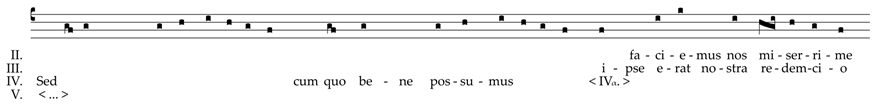

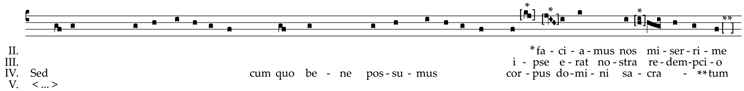

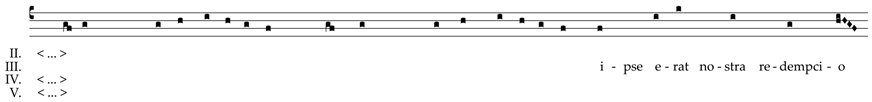

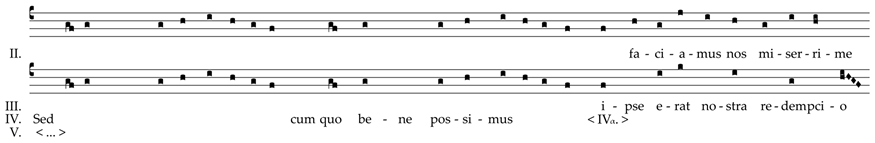

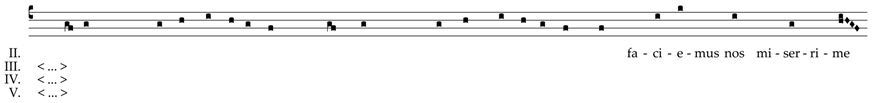

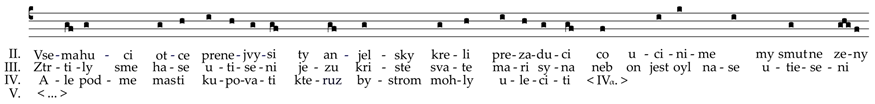

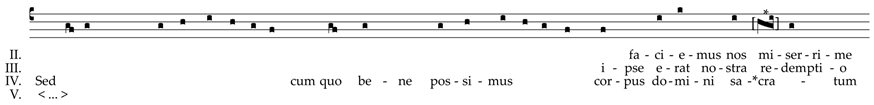

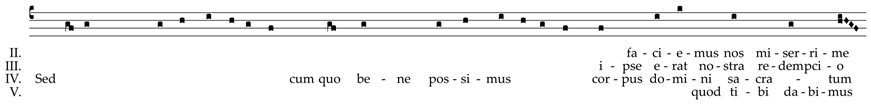

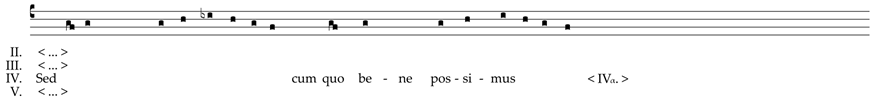

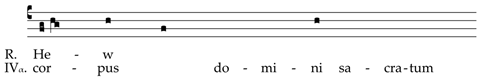

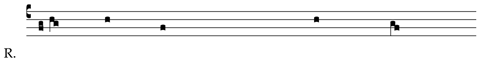

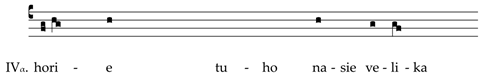

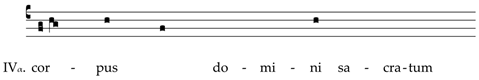

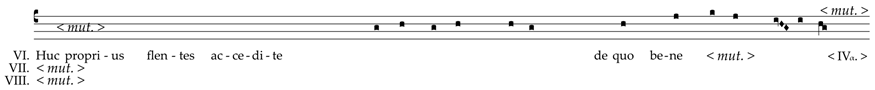

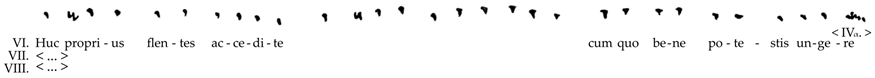

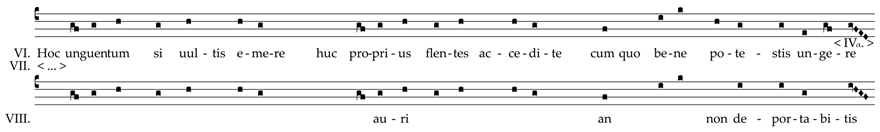

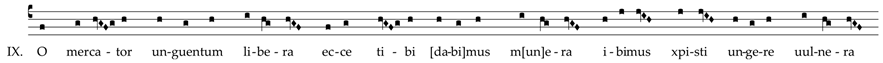

In the comparison of melodic motifs transitioning from the responsory/verbeta to stanzas I and II (=III–IX) in the merchant scene—presented here through a synoptic arrangement using colors and boxes (Figure 3)—one can observe strong melodic cohesion and the multiplicity of relationships that emerge during the transition from the final responsory of the Matins nocturne to the liturgical performance of all the biblical or imagined moments associated with the visit to the sepulcher, before the bishop intones the Te Deum. In this specific context, Eberle’s exemplary musical analysis already compared and identified the melodic relationship between the beginning of stanza I and the responsory but omits the intermediary link through which this relationship is indirectly established, as the verbeta Christus hodie surrexit serves as the connecting element that links the responsory and the Visitatio. Nevertheless, his analysis remains highly useful in illustrating how, after the merchant scene in D mode (protus), the motifs of the stanzas gradually transform from a modal perspective, culminating in G mode (tetrardus), within which the dialogue Quem quaeritis—the authentic core of the Visitatio—and the Te Deum itself unfold (Eberle 2019, 2023). This transformation represents a remarkable exercise in compositional craftsmanship.

Figure 3.

Musical transcription 2: Motivic relationships between responsory, verbeta (Vic 118, ff. 87r–88r), and merchant stanzas and refrain (Vic 105, ff. 58v–59r).

On the other hand, the typical structure of the verbeta—a double cursus with rhymes based on the sonority of melisma, specifically in this case on the vowel “o”—explains the poetic–musical function of this form in the first stanza (AA) of the merchant scene. In other words, it serves as a true gateway to the liturgical drama. Moreover, as shown in Table 7, the verbeta reflects the rhythmic imitation of iambic trimeter (5pp + 7pp) in the first couplet, trochaic septenarius (8pp + 7pp) in the second, and catalectic dactylic tetrameter in the final single line (10p). These metrical patterns ultimately shape all nine of the merchant’s stanzas in one way or another.

Table 7.

Poetic and melodic design of Christus hodie surrexit ex tumulo.

Therefore, it is difficult to deny the coherence within the sequence Et valde mane (responsory), Christus hodie surrexit (verbeta), merchant scene (Visitatio Sepulchri), which not only establishes a clear liturgical context in Vic but also suggests a series of broader implications. For instance, the verbeta is a unicum from Catalonia, chronologically sourced as follows: GerS 45, f. 12v; BarAm 381, f. 6r; Vic 134, ff. 17r and 18r; Vic 117, f. 72r; Würz s/n, f. 66v; Vic 118, f. 87v; Vic XVIII 13; Bar 662, f. 53v; Bar 706, f. 54v; Vic 85, ff. 74v, 76r, and 79r; Tar 84, f. 32r; Ger 20 e 3, ff. 58r and 71r; Pa 1309, f. 84r; BarO s/n, f. 60r; Tar s/n, f. 74v; and BarFC s/n, f. 220v. This implies that, if it serves as the cornerstone for the poetic and musical construction of the merchant scene, the origin of this scene must be traced to Catalonia, most likely within the creative center of Vic–Ripoll. From there, this initial secular scene would spread extensively across Europe, undergoing adaptations and expansions—both in Latin and in vernacular languages—ultimately emerging as one of the quintessential scenes of medieval theater. Exploring hypotheses regarding these transmission paths will be our next step.

2.3. Manuscript Transmission of the Merchant Scene

After clarifying its liturgical origin in the Easter Matins, any hypothesis regarding a cultural object, such as the nine stanzas of the merchant scene, must be grounded in two fundamental principles: first, the development of a philological–musicological critical edition and second, an analysis based on criteria from the fields of reception history and cultural exchanges (for a more detailed explanation of this necessary combination, see Tello Ruiz-Pérez 2006, pp. 6–16). The first principle is presented here in a synoptic form, detailing all readings and variants in relation to Vic 105 (Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C, Appendix D, Appendix E), while the second is introduced only as a provisional argument, a work in progress.

Given the substantial number of manuscripts we have examined—alongside the extensive body of literature4 that each has produced over nearly two centuries—and the fact that some manuscripts are in Latin while others are partially or entirely in Langue d’oïl, Southern Bavarian, various other dialects of Upper German, or Old Czech, undertaking a stemmatic analysis is far from straightforward. In total, we have 42 manuscripts containing 47 distinct versions, each from different periods, composed for different purposes, and illustrating how stanzas were integrated into particular, and sometimes unique, contexts. This complexity only further intensifies the challenge.

To address this complexity, we have grouped the sources by geographical regions or manuscript families, arranging them chronologically from the oldest to the most recent, based on the concordance of variant similarities. Accordingly, we have delineated several regions: Catalonia and Occitania, the Northwest, the Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest, the Hesse Group, Bohemia, and finally, Lower Saxony. Amid this apparent “mixed bag”, we have also found that some manuscripts transmit the repertoire in adiastematic notation, requiring us to treat the entire melody as a variant in itself in those cases. Conversely, when the notation is diastematic, we have employed square notation and non-standard transcription methods to facilitate easier comparison of various neumatic groupings.

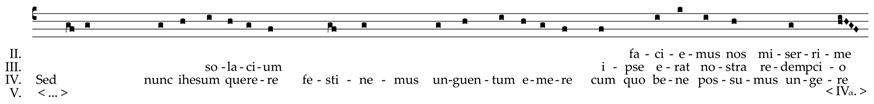

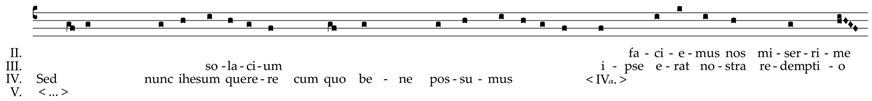

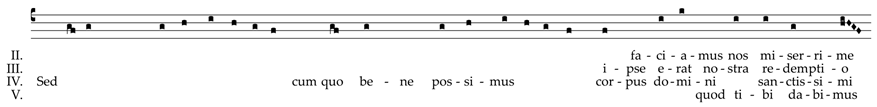

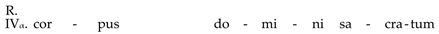

Before proceeding with any strict assessment of readings and musical–textual variants, it is essential to first address the transmission and arrangement of stanzas in each source (Table 8). For example, stanzas Ia–b (Vic 105 and Vic 187) and IX (Vic 105) are unique to the Vic Cathedral. Additionally, we have identified other stanzas—restricted to those in Latin—that do not appear in the original core of Vic 105. In such cases, these stanzas are marked with a letter in brackets. Similarly, we have emphasized specific features of each source in italics and brackets, such as their presence in incipit, an absence of musical notation [s.n.], mutilation [mut.], and other relevant details. To aid comprehension, a census of all these additional stanzas, along with their corresponding text, has been compiled and is provided in Appendix F.

Table 8.

Distribution of the stanzas by source.

The most striking feature of the stanza distribution in Table 8 is the noticeable lack of uniformity in both their number and order. This phenomenon can be attributed to the diversity of contexts—almost all related to Easter—in which they are embedded. A liturgical drama differs significantly from a Passion play performed in a town square, just as a mystère diverges from a play that is part of an educational collection. The occasion and usage dictate all aspects, leading to a broad spectrum that ranges from intimate planctus to elaborate theatrical productions, where Easter occasionally appears to be merely an excuse. Furthermore, the number of merchants, apothecaries, doctors, and their families and friends varies considerably, from the solitary “mercator iuuenis” of Vic 105 to an entire procession of diverse characters and intricate secondary narratives in the Eger Passion Play. This variation in the number of “merchants” could be particularly intriguing when considering iconographic representations.

As a working hypothesis regarding the issue of readings and variants, and without delving into excessive detail, we first present an inversion of a prevalent assumption among contemporary scholars. Specifically, it is commonly believed that a composition of any type originates simply and becomes increasingly sophisticated over time through reinterpretations. Conversely, we observe that the opposite holds true for our nine stanzas. There is no version more complex than that of Vic 105, as evidenced by both its internal and external relationships. From this version, the melody—while preserving its original structure—gradually simplifies, particularly in relation to its neumatic style in the stanzas and the melismatic character of the refrain, approaching a syllabic style in certain cases.

Among the earliest testimonies documenting the stanzas derived from the version in Vic 105, one trajectory extends northwesterly toward Tours 927 (of uncertain origin but conceived within a Norman/Angevin milieu), while another moves toward the heart of Central Europe, likely via a goliard, as evidenced by Mü 4660a and Mü 4660. It is important to note that Ripoll, as attested by its Carmina Rivipullensia, served as a transit point for goliards. Along both routes, the addition of new stanzas generated a particular diffusion in which, undoubtedly, many intermediate testimonies have been lost. However, in general terms, this dual diffusion proves to be entirely heterogeneous due to factors such as multilingualism and varied purposes.

Nevertheless, based on the versions of these early sources (Tours 927, Mü 4660a, and Mü 4660), which already offer a new interpretation in contrast to Vic 105, a preliminary examination of the synoptic edition suggests that one could argue for a relative stability in the transmission of both the text and melody of our stanzas across the respective stemmatic branches that emerge from them. Interestingly, there are generally greater divergences between Vic 105 and the entire corpus than within the corpus itself. This observation remains significant regardless of context and use. In some respects, it is as if one could discern a sacred mark of origin within the liturgy that must be respected as the locus auctoritatis where the theatrical interest in introducing the stanzas involving the commercial transaction of selling ointments to the holy women first emerged. As we assert, this remains merely a working hypothesis.

3. The Iconographic Motif of the Sale of Ointments

We begin with the premise that the motif of the scene, as observed, originated in a sophisticated manner from the liturgy, specifically within the context of a Visitatio Sepulchri. It is essential to recognize that this dramatic model incorporated profane elements derived from the everyday commercial practices in Vic at the time—such as the merchant’s demonstrated skill in selling his products at favorable prices, as illustrated in Vic 105. Consequently, it is reasonable to assert that this phenomenon likely captured the imaginations of sculptors and manuscript illuminators. This scenario exemplifies the theories proposed by scholars such as Mâle and Davidson (e.g., as updated in González Montañés 2002), particularly regarding the notion that the iconographic paradigm emerged from dramatized performances of the liturgy.

However, the iconography of the paschal sale of ointments is by no means among the most widely disseminated in the medieval world, as evidenced by the scarcity and dispersal of the testimonies in which it appears. It is likely that its extrabiblical nature posed significant limitations on its representation in the visual arts, especially on the part of the patrons. Despite this dispersion, we shall examine a few examples—some of which, to the best of our knowledge, remain unpublished in critical scholarship—that notably appear to converge along the same primary transmission routes as the nine stanzas of the drama under discussion.

3.1. An Early Isolated Testimony

Notably, the earliest known representation of this scene dates to the early 11th century, significantly earlier than Vic 105, and can be found in the Uta Evangeliary from Regensburg. It is depicted specifically in a decorative medallion in the Gospel of Saint Mark (Berthold 1972, pp. 236–38). The manuscript is housed in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek under catalog number Mü 13601, and it was commissioned around 1025 by Abbess Uta von Niedermünster of Regensburg, Bavaria (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Detail of Mü 13601, f. 86r.

In the upper left corner, two of the Maries are visible; strikingly, the figure of Salome is absent from the image (Cohen 2000, p. 115), despite the fact that all three Maries are mentioned in both the accompanying titles and the Gospel narrative. It is possible that one of the figures was omitted due to spatial constraints, or, as Cohen suggests (Cohen 2000, p. 117), the image may have been based on a different visual model. Nevertheless, this depiction appears to be unique and iconographically isolated until comparable evidence emerges in the visual arts of later periods, particularly in the 12th and 13th centuries. These later instances, however, do not seem to be temporally or spatially connected with Mü 13601, nor do they appear to have evolved from this example. Moreover, Mü 13601 clearly does not owe any referential debts to liturgical or non-liturgical performances.

3.2. The Catalan–Occitan Group

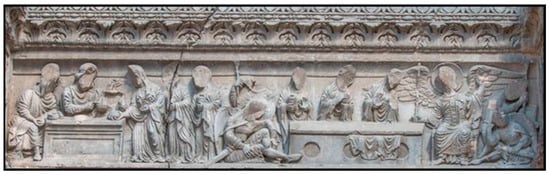

Our next reference can be found at the entrance of the Provençal Abbey of Saint-Gilles-du-Gard (ca. 1130–1150), where the tympanum dedicated to the Crucifixion (on the right portal) depicts a scene representing the sale of ointments and the visit to the Sepulcher by the three Maries, along with other scenes related to the Resurrection (Figure 5). A stylistically and chronologically related example is preserved in the cloister of Saint Trophimus in Arles (north and east galleries), where the northwest pillar features a depiction of the sale of ointments and the Resurrection (Figure 6). Notably, in this representation, the scene of the visit to the tomb is absent, in contrast to the other examples.

Figure 5.

Detail from the west façade of the Provençal church of Saint-Gilles-du-Gard.

Figure 6.

Detail from the cloister of Saint Trophimus in Arles.

A third example, possibly derived from the aforementioned works, can be found in the frieze of Notre-Dame des Pommiers in Beaucaire, which depicts the sale of ointments and the visit to the Sepulcher. In this scene, the three women are shown before the merchant, who is weighing the perfumes on a scale (Figure 7). Similarly, in the Civic Museum of Modena, there is a capital that stylistically resembles the frieze of Beaucaire, representing the Sale of Perfumes (Figure 8). This capital originates from the Pieve di San Vitale di Carpineti, located in the Reggio area, and was donated to the Museum by Giuseppe Campori in 1884. Attributed to a craftsman from the Po Valley, it dates to before 1178 and is made of marble.

Figure 7.

Detail of the frieze at Notre-Dame des Pommiers in Beaucaire.

Figure 8.

Capital from the Pieve di San Vitale in Carpineti.

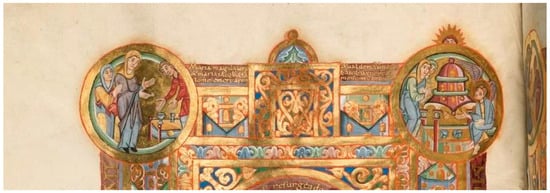

These four testimonies can be categorized within the same group due to their close relationships and shared context, which revolves around the artistic centers in Provence. Although the scene depicting the sale of ointments rarely appears in visual representations (Lorés i Otzet 1986), there are two additional examples of this scene in the Catalan region: one is a capital located in the southern area of the cloister of Sant Cugat del Vallés, and the other is a capital housed in the Cluny Museum in Paris, which is purportedly Catalan and most likely originates from Sant Pere de Rodes, although its provenance remains uncertain. This latter capital stylistically resembles the sculptures found in the cloister of Girona Cathedral and the aforementioned capital from Sant Cugat (Lorés i Otzet 1986, p. 132). Both capitals depict scenes of the sale of ointments and the visit to the Sepulcher, and the stylistic similarities between these capitals and those of Girona Cathedral are evident.

One characteristic shared by the capitals of Girona Cathedral and the cloister of Sant Cugat del Vallès is the architectural elements (turrets) framing the depicted scenes in the historiated and biblical capitals. The cloister of the monastery of Sant Cugat del Vallès contains a key element that aids in dating its construction and indicates that it was built after the cloister of Girona. This temporal reference is provided by the testamentary legacy of Guillem de Claramunt in 1190, which supported the construction of the cloister. The similarities and coincidences between both sculptural ensembles have been attributed to the presence of a workshop from Girona that relocated to Sant Cugat, leaving its mark on the Vallesan monastery with the sculptural traditions of Ripoll and, consequently, Roussillon. Furthermore, this is the only definitive reference that allows us to ascertain the presence of a workshop operating in the cloister, which originated from the Girona Cathedral. The construction of the Girona cloister began around the 1180s, involving sculptors trained under the influence of the third workshop of the Daurada in Toulouse. These sculptors, who worked in Girona, likely also contributed to the work at Sant Pere de Rodes and later may have moved to Sant Cugat, possessing a thorough knowledge of the local tradition due to the dissemination of sculpture from Roussillon and Ripoll (Lorés i Otzet 1991, p. 70).

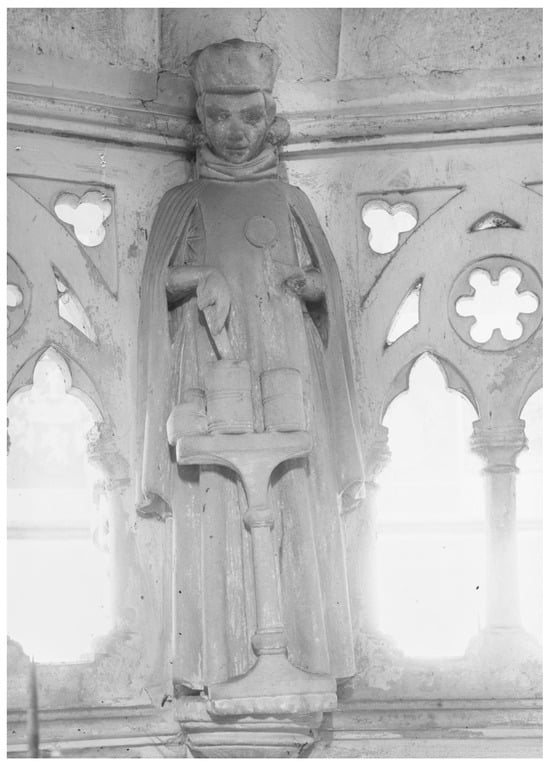

The capital from the cloister of Sant Cugat del Vallès is situated in the southern gallery within the iconographic cycle of the Passion (Figure 9). It closely resembles the capital located in the Cluny Museum that depicts the same scene, which is likely to have originated from Sant Pere de Rodes (Lorés i Otzet 1986).5 The six capitals from Catalonia housed in the Cluny Museum were acquired in 1881 in Paris by Edmond de Sommerand from a collector named Stanislas Baron upon his return to Spain. Although the museum has no record of their provenance (Lorés i Otzet 1994, p. 59), it is significant that Salet also notes their connections to those from the cloister of the Girona Cathedral as well as those from Sant Cugat (Salet 1959).

Figure 9.

Capital from the cloister of Sant Cugat del Vallés.

There are several indications that may suggest the capitals studied by Salet could have originated from a common source. All six examples were acquired simultaneously by the same individual; they possess identical dimensions of 35 × 28 cm; and they are constructed from the same material, limestone (Lorés i Otzet 1994, p. 60). Furthermore, the connection between these capitals and those from the cloisters of Girona and Sant Cugat, as noted by Salet, along with the identification of one capital as originating from the monastery of Rodes, may lead to the conclusion that the six capitals purchased in 1881 by the Cluny Museum are part of the group that was looted from the Monastery of Sant Pere de Rodes. Indeed, the acquisition dates coincide with the most intense years of cloister dismantlement.

As Lorés points out (Lorés i Otzet 1994, p. 80), the iconographic program of Sant Pere de Rodes may have concluded coherently with the episode of the Resurrection of Christ. In the fourth capital of the six mentioned, preserved in the Cluny Museum (Figure 10), the themes of the sale of ointments and the visit to the tomb of the three Maries are represented. On two faces of the capital, the women are depicted carrying containers to anoint the body of Christ and encountering the angel. The first woman gestures toward the flask, while the angel indicates where Christ has gone. This composition is echoed in a capital from the southern gallery of Sant Cugat, reflecting the dialogue between the characters, which constitutes the core of the scene—Quem quaeritis—in which the angel announces that Christ has risen. Although the capitals adhere to the characteristics common in most Western compositions, there are notable differences in certain details. The capital from Sant Pere de Rodes presents a composition that deviates somewhat from the more generalized type.

Figure 10.

Capital from the Musée du Cluny, Paris. Catalog number Cl. 19002 (Cl. 10757).

Concerning the scene of the sale of ointments at both Sant Cugat and Sant Pere de Rodes, it is depicted on two faces of the capital. The women approach the merchant and apothecary, who are positioned behind a table. In the foreground, scales and containers are visible. Both capitals, dated to the third quarter of the 12th century, directly present the scene followed by the visit to the Holy Sepulchre. These scenes are framed by semicircular arcades (two on each side), reminiscent of another capital housed in the Cluny Museum, which depicts the Nativity of Jesus.

As Lorés points out, this is all connected to the Visitatio Sepulchri in Vic 105 (Lorés i Otzet 1994, p. 82). The depiction of a merchant and an apothecary in these scenes is not at all unusual in later manuscript sources containing the drama, including those from Catalonia (Ger s/n), where we frequently find a complete cast of related characters, often involved in secondary narrative threads, whether implicit or explicit. In surviving visual examples, when this occurs, a similar compositional scheme is consistently followed: two figures seated behind a table, two merchants—one young and one old—and the three Maries approaching from the side. However, an exceptional case can be found in the pillar of the cloister of Arles, where the composition deviates from this norm by dividing the scene into two overlapping registers: the upper register depicts the three Maries, while the lower register shows the merchants seated behind a table.

3.3. Later Examples

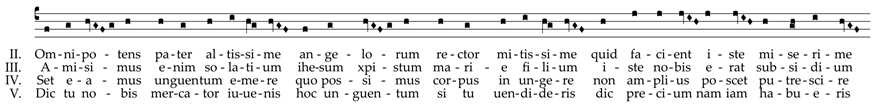

We would like to succinctly address several later iconographic testimonies that may be connected, in various ways, to the primary channels through which the performative scene was transmitted. Of particular significance in this context is the sculptural ensemble within the Holy Sepulchre in the Chapel of St. Maurice (1286–1300) at Constance Cathedral (Figure 11). This ensemble is notable for its specificity, depicting a merchant in the role of an apothecary, characterized by a scholarly demeanor reflective of the customs of the period for this type of trade (Tripps 1999, figs. 50 a–c; Kurmann 2016). It is highly likely that the iconographic program of this work was influenced by the strong impact of performances represented in manuscripts from the southern Bavarian region and the Black Forest.

Figure 11.

Detail of the apothecary from the Holy Sepulchre in the Chapel of St. Maurice at Constance Cathedral.

On the other hand, directly connected to the specionarius of DHaa 71 J 70, we find a representation in NY M 87, f. 202v (Figure 12). In this illumination, the holy women are depicted in the act of purchasing, standing before a learned figure who is seated, almost enthroned, suggesting both high social status and a carefully crafted scenographic design. Similarly, although in a different context, as Katritzky notes, comparable vignettes appear in manuscripts illustrating Arnoul Gréban’s French Mystère de la Passion (Katritzky 2018, p. 112, illustrations 10a, 10b). Finally, we wish to highlight another example from the Poitiers missal Pa 873, f. 194r, this time related to the Sponsus Play, where, in the Common of Virgins, the wise virgins are shown purchasing oil as the merchant fills their jars (Figure 13).6

Figure 12.

Detail of NY M 87, f. 202v.

Figure 13.

Detail of Pa 873, f. 194r.

4. Conclusions

In a concise summary, we present the key findings of our ongoing research. First, we have provided philological and musicological evidence, supported by well-reasoned arguments, to situate the origin of the merchant scene almost unequivocally in the Catalan region, specifically in Vic. Notably, due to its strong poetic and melodic connection with the final responsory—preceding the Te Deum—of the Easter Matins and its verbeta (Christus hodie surrexit), which is unique to Catalonia, we have demonstrated that the scene’s origins are deeply embedded in the development of the Easter liturgical rite at Vic Cathedral.

Therefore, in response to the question of whether the Visitatio Sepulchri of Vic 105, in which the sale of ointments is integrated for the first time, should be classified as a literary work, a Ludus Paschalis, or a liturgical drama, we can confidently assert that the “Verses Pascales de III Mariis” of Vic 105 constitutes a liturgical drama closely associated with the events surrounding Christ’s Resurrection. This is followed in the manuscript by another liturgical drama, the Peregrinus, composed for the Vespers of Easter Monday.

Moreover, the stylistic characteristics of the nine stanzas that comprise this scene, which mark the beginning of the Visitatio, suggest a connection to the compositional genres of the Neues Lied. This association could potentially place the composition as early as the late 11th century, particularly given that in Vic 105—the earliest known liturgical testimony of the introduction of this extrabiblical secular scene—the entire drama appears as a late 12th-century addition. This earlier dating aligns with the copying of formally similar dramatic and poetic compositions, such as the Sponsus or the versus repertoires in Aquitaine.

Based on this evidence and through a critical edition of the stanzas, we have formulated a working hypothesis regarding the widespread transmission of the scene across Europe. There is substantial reason to believe that this transmission occurred shortly after the testimony found in Vic 105, branching in two directions: one towards the Norman northwest and the other, via the Carmina Burana, into the heart of the continent. From these key points, various additions, variations, and performative adaptations—both formal and contextual—proliferated, organizing the testimonies into distinct families and regions with relatively consistent boundaries.

Our working hypothesis underscores the pivotal role of multidisciplinary and cross-disciplinary approaches in liturgical studies. To this end, we have integrated notable instances of the sale-of-ointments motif in iconography—despite the relative scarcity of such representations. Nonetheless, it is significant that these examples are concentrated in the Catalan–Occitan region, indicating a clear connection with the liturgical drama preserved in Vic 105, both due to their geographic proximity and the iconographic elements employed. As previously mentioned, the study of transmission is ongoing; however, it is encouraging to observe increasing support for this horizontal approach (e.g., Abajo Vega 2005).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T.R.-P. and P.P.B.; methodology, P.P.B. and A.T.R.-P.; formal analysis, P.P.B. and A.T.R.-P.; investigation, P.P.B. and A.T.R.-P.; resources, P.P.B. and A.T.R.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T.R.-P. and P.P.B.; writing—review and editing, A.T.R.-P. and P.P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to replace Figures 2 and 3 with high-definition versions, and correct the typo in word "ante" to "Dante", in note 2. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

Appendix A. Synoptic Edition of Stanza I

Vic 105 |

| Catalonia and Occitanie |

Vic 187 |

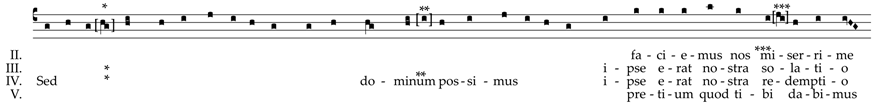

Appendix B. Synoptic Edition of Stanzas II–V

Vic 105 |

| Catalonia and Occitanie |

Martène |

| Northwest |

Tours 927 |

SQ 86 |

DHaa 71 J 70 |

| Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

Mü 4660a |

Mü 4660 |

SG Fragm. Fab. IV |

NY M 886 |

Vip IV (b) |

Vip IV (a) |

Vip XIV |

Ith 410 |

Bol I 51 |

Mü 7691 |

InnsK 1 rtr.m |

Vip III |

Vip VII |

InnsM 575 |

FBs 12 |

| Hesse–Thuringia Group |

FM 178 |

FM III 6 |

Be 757 |

Mühl 60/20 |

Inns 960 |

Be 1219 |

Ka 18 |

| Bohemia |

Wi 13427 |

PrU VIII G 29 (a) |

PrU VIII G 29 (b) |

PrU I B 12 |

Wro 226a |

PrU XVII E 1 (a) |

PrU XVII E 1 (b) |

Nürn 7060 |

Zwi 1 15 3 |

Zwi 36 1 24 (a–c) |

Eger B V 6 |

| Lower Saxony |

Hild 383 |

Wol VII B 203 |

Wol 965 |

TriS 1973/63 |

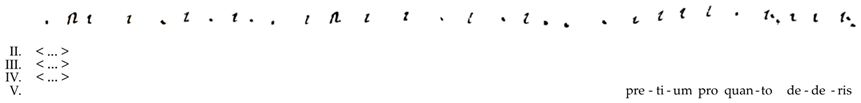

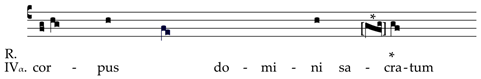

Appendix C. Synoptic Edition of the Refrain and Stanza IVα

Vic 105 |

| Catalonia and Occitanie |

Bar 911 |

Martène |

| Northwest |

Tours 927 |

DHaa 76 F 3 |

SQ 86 |

DHaa 71 J 70 |

| Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

Mü 4660a |

Mü 4660 |

SG Fragm. Fab. IV |

NY M 886 |

Vip IV (b) |

Vip IV (a) |

Vip XIV |

Ith 410 |

Bol I 51 |

Karls D 137 |

InnsK 1 rtr.m |

Vip III |

Vip VII |

InnsM 575 |

| Hesse–Thuringia Group |

FM 178 |

FM III 6 |

Be 757 |

Mühl 60/20 |

Inns 960 |

Be 1219 |

Ka 18 |

| Bohemia |

PrU VIII G 29 (a) |

PrU VIII G 29 (b) |

PrU I B 12 |

Wro 226a |

PrU XVII E 1 (a) |

PrU XVII E 1 (b) |

Nürn 7060 |

Zwi 1 15 3 |

Zwi 36 1 24 (a–c) |

Eger B V 6 |

| Lower Saxony |

Hild 383 |

Wol VII B 203 |

Wol 965 |

TriS 1973/63 |

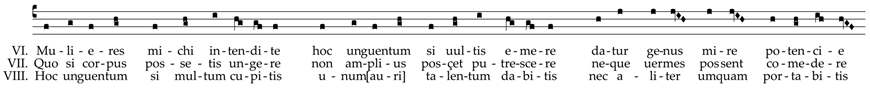

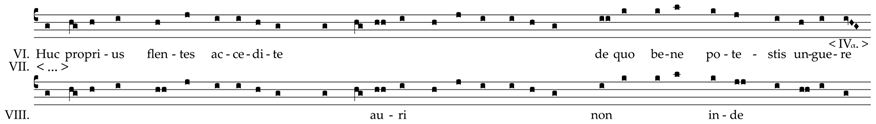

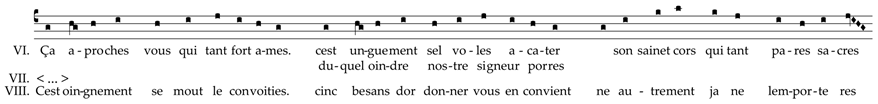

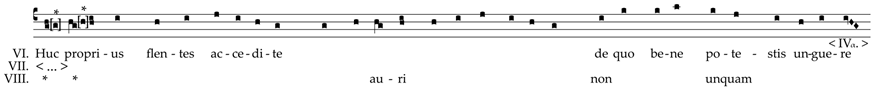

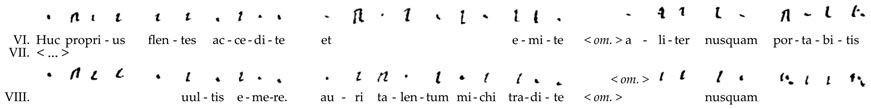

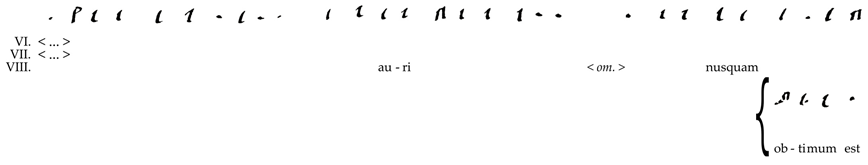

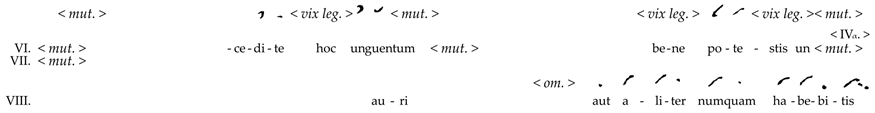

Appendix D. Synoptic Edition of Stanzas VI–VIII

Vic 105 |

| Catalonia and Occitanie |

Bar 911 |

| Northwest |

Tours 927 |

DHaa 76 F 3 |

SQ 86 |

DHaa 71 J 70 |

| Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

Mü 4660a |

Mü 4660 |

SG Fragm. Fab. IV |

NY M 886 |

| Hesse–Thuringia Group |

FM 178 |

FM III 6 |

Be 757 |

Inns 960 |

Ka 18 |

| Bohemia |

Eger B V 6 |

| Lower Saxony |

Wol 965 |

Appendix E. Synoptic Edition of Stanza IX

Vic 105

Appendix F. Latin Stanzas Not Present in Vic 105 (The Source from Which the Reading Is Taken Is Indicated)

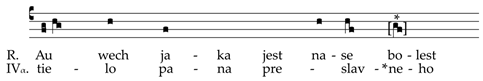

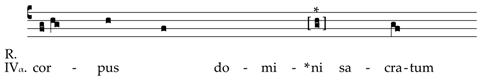

| Tours 927 | ||

| A. | Venite si | complacet emere |

| hoc unguentum | quod uellem uendere | |

| de quo bene | potestis ungere | |

| IVα. | corpus domini sacratum | |

| Mü 4660a | ||

| B. | Aromata | pretio querimus |

| corpus iesu | uolumus ungere | |

| aromata | sunt odorifera | |

| sepulture | xpisti memoria | |

| C. | Dabo uobis | ungenta optima |

| saluatoris | ungera uulnera | |

| sepulture | eius in memoriam | |

| et nomini | eius ad gloriam |

| Inns 960 | |

| D. | Heu nobis internas mentes |

| quanti pulsant gemitus | |

| pro nostra consolatione | |

| qua priuamur miseri | |

| quam crudelis iudeorum | |

| morte dedit populo | |

| E. | Iam percusso ceu pastore |

| oues errant miseri | |

| sic magistro discedente | |

| turbantur discipuli | |

| abque nobis eo absente | |

| dolor crescit nimius |

| F. | Sed eamus et ad eius |

| properemus tumulum | |

| si dileximus uiuentem | |

| diligamus mortuum | |

| et ungamus corpus eius | |

| o leo sanctissimo |

| G. | Ibant ibant tres mulieres |

| ihesum ihesum ihesum querentes | |

| maria jacobena maria cleophea et salomena | |

| re uemasti tu tres mulieres | |

| dare mihi narium | |

| dabo tibi sal salium |

| PrU VIII G 29 (a) | ||

| H. | Ad monumentum uenimus gementes | |

| angelum domini sedentem | uidimus et dicentem | |

| quia surrexit ihesus | ||

| (Cantus n.d., chant ID 850144) | ||

| PrU I B 12 | |

| J1. | Dum transisset |

| Et ualde mane una sabbatorum ueniunt ad monumentum orto iam sole | |

| (Intonation of Mc 16, 1–2) | |

| PrU XVII E 1 | |

| J2. | R. Dum transisset sabbatum maria magdalena et maria iacobi et salome emerunt aromata |

| Ut uenientes ungerent Jesum alleluia Alleluia | |

| ℣. Et ualde mane una sabbatorum ueniunt ad monumentum orto iam sole | |

| ℣. Gloria Patri et filio et spiritui sancto | |

| (Cantus n.d., chant ID 006565 and 006565a) | |

| K. | Leta Syon laudans plaude |

| renouata terra gaude | |

| agens deo gracias |

| L. | Veni desiderate |

| ueni xpiste amate | |

| ueni patris gloria | |

| ueni sanctorum corona |

| M. | Quis est iste qui uenit cum gloria |

| cum quo sanctorum copia | |

| peragi [sic] at [sic] celi palacia |

| Zwi 36 1 24 | |

| O. | Ihesu nostra redempcio |

| amor et desiderium | |

| deus creator omnium | |

| homo in fine temporum | |

| P. | Que te uicit clemencia |

| ut ferres nostra crimina | |

| crudelem mortem paciens | |

| ut nos ab hoste tolleres |

| Q. | Inferni claustra penetrans |

| tuos captiuos redimens | |

| uictor triumpho nobili | |

| ad dextram patris residens |

| Eger B V 6 | |

| S. | Nuper ueni de studio |

| scio quod tota regio | |

| mihi coequalem | |

| nescit nec habet talem | |

| hoc loquor sine fraude | |

| sed tamen ficta laude | |

| Wol VII B 203 | |

| T. | Heu uerus pastor occidit |

| quem culpa nulla infecit | |

| O mors plangenda | |

| U. | Heu nequam gens iudaica |

| innocentis homicida | |

| O gens damnanda |

| V. | Heu quid agemus misere |

| dulci magistro orbate | |

| O mors lacrimanda |

| W. | Hinc eamus |

| ut ungamus | |

| Condimentis | |

| Dormientis | |

| caraem sanctam xpisti |

| DHaa 76 F 3 | |

| X. | Femine quid gemitis |

| quid gementes queritis | |

| et sic hic preceditis | |

| et ex hiis non emitis | |

| rebus aromaticis | |

| sepulture debitis. | |

| Nostrum solatium heu | |

| Y. | Ihesu nostra redempcio |

| Z. | Ista pixis nobile | continet ungentum |

| ista cui simile | non est adimentum | |

| si quis huius | tercie deferat ungentum | |

| auri dabit integrum | marcam aut talentum | |

| Tibi dabimus heu | ||

Appendix G. Archival Souces

| Sigla | RISM Sigla | Signature | Provenance | Century | Typology | Area |

| Bar 662 | E–Bbc 662 | Barcelona, Biblioteca de Catalunya, M. 662 | Barcelona | 14/15 | Antiphonary | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| Bar 706 | E–Bbc 706 | Barcelona, Biblioteca de Catalunya, M. 662 | Catalunya | 14/15 | Antiphonary | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| Bar 911 | E–Bbc 911 | Barcelona, Biblioteca de Catalunya, M. 911, frag. f. 156 | Girona, Seu Sta. Maria | 13/14 | Troper–Proser | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| BarAm 381 | E–Bac m. 381 | Barcelona, Arxiu de la Corona d’Aragó, Monacales 381 (Cod. Varia. VIII) | Girona (Col·legiata St. Feliu?) | 12 | Antiphonary | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| BarFC s/n | E–Bcapdevila s/n | Barcelona, Felipe Capdevila Rovira, colección privada, Ms. s/n | Tarragona, Seu Sta. Tecla | 1568 (16m) | Processional | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| BarO s/n | E–Boc s/n | Barcelona, Centre de Documentació de l’Orfeó Català, Ms. s/n | Sant Joan de les Abadesses, Monestir St. Joan de les Abadesses | 1425 (15i) | Processional | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| Be 757 | D–B 757 | Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin—Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Cod. germ. fol. 757 [Fragment] | Thuringia | 14 | Berliner Thuringian Easter Play | Hesse–Thuringia Group |

| Be 1219 | D–B 1219 | Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin—Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Cod. germ. fol. 1219 | Mainz area | 1460 (15m) | Dirigierrolle of the Mainz Easter Play | Hesse–Thuringia Group |

| Bol I 51 | I–BZf I 51 | Bolzano, Biblioteca del Convento dei padri Francescani, Cod. I 51 | Bolzano (Tirol) | 1495 (15x) | Bolzano Passion Play | Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

| DHaa 71 J 70 | NL–DHk 71 J 70 | Den Haag, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, ms. 71 J 70 | Egmond–Binnen, Benedictijnerabdij St. Adalbert | 15 | Hymnary | Northwest |

| DHaa 76 F 3 | NL–DHk 76 F 3 | Den Haag, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, ms. 76. F. 3 | Maastricht, St. Servaasbasiliek > Delft, St. Hippolytus–Kerk | 12x/13i | Evangeliary | Northwest |

| Eger B V 6 | H–EG B V 6 | Eger, Főegyházmegyei Könyvtár, Cod. B. V. 6 (olim 772–774) | Eger (Bohemia) | 1563 (16m) | Eger Passion Play | Bohemia |

| FBs 12 | D–FRsa 12 | Freiburg im Breisgau, Stadtarchiv, B 1 (H) Nr. 12 | Freiburg im Breisgau, Münsterplatz | 1599 (16x) | Freiburg Passion Play | Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

| FM 178 | D–F 178 | Frankfurt am Main, Universitätsbibliothek Johann Christian Senckenberg, ms. Barth. 178 (Ausst. 29) | Frankfurt am Main | 14i | Dirigierrolle of the Frankfurt Passion Play | Hesse–Thuringia Group |

| FM III 6 | D–F germ. III 6 | Frankfurt am Main, Universitätsbibliothek Johann Christian Senckenberg, fragm. germ. III 6 | Frankfurt am Main | 14i | Frankfurt Passion Play | Hesse–Thuringia Group |

| Ger 20 e 3. | E–G 20 e 3 | Girona, Arxiu Capitular de la Catedral, ms. 20–e–3 (olim 9) | Girona, Seu Sta. Maria | 1356–1360 (14m) | Customary | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| Ger s/n | E–G s/n | Girona, Arxiu Capitular de la Catedral, s/n | Girona, Seu Sta. Maria | 1528–1539 (16im) | Chapter charters | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| GerS 18 | E–Gs 18 | Girona, Arxiu diocesà i Biblioteca diocesana del Seminari, Col·legiata de Sant Feliu, ms 18 (olim 158) | Girona, Col·legiata St. Feliu | 15im | Customary | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| GerS 45 | E–Gs 45 | Girona, Arxiu diocesà i Biblioteca diocesana del Seminari, Col·legiata de Sant Feliu, ms 45 (olim 20) | Girona, Col·legiata St. Feliu | 12 | Antiphonary | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| Hild 383 | D–His 383 | Hildesheim, Stadtarchiv, ms. Mus. 383 | Bad Bevensen (Lüneburg), Zisterzienserinnenkloster Medingen | 1320ca (14i) | Prayer book | Lower Saxony |

| Inns 960 | A–Iu 960 | Innsbruck, Universitäts– und Landesbibliothek Tirol, cod. 960 | Schmalkalden, Kollegiatstift St. Egidius? | 1391 (14x) | Neustift–Innsbruck Play | Hesse–Thuringia Group |

| InnsK 1 rtr.m | A–Iadk 1 rtr.m | Innsbruck, Provinzarchiv der Kapuzinerprovinz Österreich-Südtirol, Ms. Liturg. 1 rtr.m (olim Feldkirch, Bibl. des Kapuzinerklosters, Ms. Liturg. 1 rtr.m) | Benediktbeuern–Peißenberg–Schongau area | 16i | Processional [Augsburg (Feldkirch) Easter Play] | Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

| InnsM 575 | A–Imf 575 | Innsbruck, Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, Musiksammlung, 575 (V2.p.18) | Bressanone (Tirol) | 1551 (16m) | Bressanone Passion Play | Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

| Ith 410 | US–I 410 | Ithaca (N.Y.), Cornell University Library, Archives 4600 Bd. Ms. 410 (olim MS F 6) | Bolzano (Tirol) | 15x (1494–1595) | Bozner Passion Play | Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

| Ka 18 | D–Kl 18 | Kassel, Landesbibliothek und Murhardsche Bibliothek der Stadt Kassel, 2° Ms. poet. et roman. 18 | Friedberg/Alsfeld | 16i (1501–1517) | Alsfeld Passion Play | Hesse–Thuringia Group |

| Karls D 137 | D–KA D 137 | Karlsruhe. Badische Landesbibliothek, Cod. Donaueschingen 137 | Donaueschingen | 15mx | Donaueschingen Passion Play | Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

| Klos 574 | A–KN 574 | Klosterneuburg, Augustiner–Chorherrenstift, Bibliothek, Cod. 574 | Klosterneuburg, Augustiner–Chorherrenstift St. Mariä Geburt | 13i | Miscellany | Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

| Martène | Edmond Martène. 1736. De antiquis Ecclesiae ritibus libri tres. Antwerpen: J. B. de La Bry, from an Ordinarium from Narbonne, which is no longer locatable | Narbonne, Cathédrale St. Just–et–St. Pasteur | 14/15 | Ordinary | Catalonia and Occitanie | |

| Mü 4660 | D–Mbs 4660 | München, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, clm 4660 | Seckau, Augustiner–Chorherrenstift BMV | 1230ca (13i) | Carmina Burana | Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

| Mü 4660a | D–Mbs 4660a | München, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, clm 4660a | Seckau, Augustiner–Chorherrenstift BMV | 1230ca (13i) | Carmina Burana (fragmenta) | Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

| Mü 7691 | D–Mbs 7691 | München, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, clm 7691, Brevier des, 1496 | Indersdorf, Augustiner–Chorberrnstifts Maria Himmelfahrt, St. Peter und St. Paul | 1496 (15x) | Breviary | Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

| Mü 13601 | D–Mbs 13601 | München, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, clm 13601 | Regensburg, Kanonissenstift Niedermünster | 11i | Evangeliary | Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

| Mühl 60/20 | D-MLHr 60/20 | Mühlhausen, Stadtarchiv, Ms. 60/20 (olim 87/20) | Eisenach (Thüringen) | 1350–1371 (14m) | Thuringian Play of the Ten Virgins | Hesse–Thuringia Group |

| Nürn 7060 | D–Ngm 7060 | Nürnberg, Germanisches National–Museum, Hs. 7060 | Eger (Bohemia) | 15x/16i (1500ca) | Eger Play | Bohemia |

| NY M 87 | US–NYpm M 87 | New York, The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M 87 | Egmond–Binnen, Benedictijnerabdij St. Adalbert | 1440ca | Breviary | Northwest |

| NY M 886 | US–NYpm M 886 | New York, The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M 886 [Fragment] | Melk, Benediktinerstift St. Peter und St. Paul | 15im (1430ca) | Mercatores Play | Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

| Pa 873 | F–Pn 873 | Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, ms. lat. 873 | Poitiers, Abbaye St. Jean de Montierneuf | 15m/x | Missal | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| Pa 1139 | F–Pn 1139 | Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, ms. lat. 1139 | Limoges, Abbaye St. Martial | 11x + 12/13 | Troper-Proser/Miscellany | Southwest |

| Pa 1309 | F–Pn 1309 | Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, ms. lat. 1309 | Girona, Seu Sta. Maria | 1457 (15x) | Breviary | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| Pa nal 903 | F–Pn nal 903 | Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, ms. nouv. acq. lat. 903 | Vic, Seu St. Pere | 14 | Customary | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| PrU I B 12 | CZ–Pu I B 12 | Praha, Národní knihovna Ceské republiky, Cod. I B 12 (cat. 68) | Praha, Katedrála sv. Víta, Václava a Vojtěcha | 1384 (14x) | Easter Play | Bohemia |

| PrU VI G 10a | CZ–Pu VI G 10a | Praha, Národní knihovna Ceské republiky, Cod. VI G 10a (cat. 1175) | Praha, Bazilika–Klášter sv. Jiří | 13/14 | Processional Antiphonary | Bohemia |

| PrU XIII E 14d | CZ–Pu XIII E 14d | Praha, Národní knihovna Ceské republiky, Cod. XIII E 14d (cat. 1175) | Praha, Bazilika–Klášter sv. Jiří | 14 | Ordinary | Bohemia |

| PrU XIII H 3c | CZ–Pu XIII H 3c | Praha, Národní knihovna Ceské republiky, Cod. XIII H 3c (cat. 2396) | Praha, Bazilika–Klášter sv. Jiří | 14 | Processional | Bohemia |

| PrU XII E 15a | CZ–Pu XII E 15a | Praha, Národní knihovna Ceské republiky, Cod. XII E 15a (cat. 2182) | Praha, Bazilika–Klášter sv. Jiří | 14i | Processional | Bohemia |

| PrU VI G 3b | CZ–Pu VI G 3b | Praha, Národní knihovna Ceské republiky, Cod. VI G 3b (cat. 1167) | Praha, Bazilika–Klášter sv. Jiří | 14 | Processional Antiphonary | Bohemia |

| PrU VII G 16 | CZ–Pu VII G 16 | Praha, Národní knihovna Ceské republiky, Cod. VII G 16 (cat. 1363) | Praha, Bazilika–Klášter sv. Jiří | 14 | Processional Antiphonary | Bohemia |

| PrU VIII G 29 | CZ–Pu VIII G 29 | Praha, Národní knihovna Ceské republiky, Cod. VIII G 29 (Y.II.5.n. 5.) (cat. 1611–1612) | Praha, Katedrála sv. Víta, Václava a Vojtěcha | 14 | Easter Play | Bohemia |

| PrU XVII E 1 | CZ–Pu XVII E 1 | Praha, Národní knihovna Ceské republiky, Cod. XVII E 1 (olim Y.III.3.n.53) (cat. 177) | Bohemia | 15 | Easter Play | Bohemia |

| SG Fragm. Fab. IV | CH–SGsap fragm. fab. IV | Sankt Gallen, Stiftsarchiv (Abtei Pfäfers), Fragm. Fab. IV | Pfäfers, Benediktinerabtei BMV (Kanton Sankt Gallen) | 14i | Passion Play | Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

| SQ 86 | F–SQ 86 | Saint–Quentin, Médiathèque Guy de Maupassant, ms. 86 | Origny, Abbaye Ste. Benoite | 1315–1317 (14i) | Ordinary | Northwest |

| Tar 84 | E–TAha 84 | Tarragona, Arxiu Històric Arxidiocesà, Ms. 84 | Tarragona, Seu Sta. Tecla | 14 | Customary | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| Tar s/n | E–TAha s/n | Tarragona, Arxiu Històric Arxidiocesà, Inc. s/n | Tarragona, Seu Sta. Tecla | 1485–1486 (15x) | Breviary (Patriarch Pere d’Urrea) | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| Tours 927 | F–TOm 927 | Tours, Bibliothèque municipale, ms. 927 | Norman/Angevin milieu | 13 | Miscellany | Northwest |

| TriS 1973/63 | D–TRs 1973/63 | Trier, Stadtbibliothek Weberbach, Hs. 1973/63 4º | Trier | 15m (1450ca) | Trier Easter Play | Lower Saxony |

| Vic 85 | E–VI 85 | Vic, Arxiu i Biblioteca Episcopal, Cod. 85 | Vic, Seu St. Pere | 1398 (14x) | Breviary | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| Vic 105 | E–VI 105 | Vic, Arxiu i Biblioteca Episcopal, Cod. 105 (olim CXI) | Vic, Seu St. Pere | 12i [add. 12x and 13i] | Troper–Proser | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| Vic 117 | E–VI 117 | Vic, Arxiu i Biblioteca Episcopal, Cod. 117 (olim CXXIV) | Vic, Seu St. Pere | 1278–1318 (13x/14i) | Processional | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| Vic 118 | E–VI 118 | Vic, Arxiu i Biblioteca Episcopal, Cod. 118 | L’Estany, Monestir–canònica agustiniana Sta. Maria | 14m | Processional | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| Vic 134 | E–VI 134 | Vic, Arxiu i Biblioteca Episcopal, Cod. 134 (olim LXXXIV) | Vic, Seu St. Pere | 1216–1228 (13im) | Customary (by Andreu s’Almunia, d. 1234) | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| Vic 187 | E–VI 187 | Vic, Arxiu i Biblioteca Episcopal, Cod. 187 | Vic, Seu St. Pere | 1445 (15m) | Easter Play (Representació del Centurió) | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| Vic s/n | E–VI s/n | Vic, Arxiu i Biblioteca Episcopal, Cod. s/n | Vic, Seu St. Pere | 1413 (15i) | Customary/Chapter charters | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| Vic XVIII 13 | E–VI XVIII 13 | Vic, Arxiu i Biblioteca Episcopal, Fragments XVIII, n. 13 [Fragment] | Vic, Seu St. Pere | 14 | Antiphonary | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| Vip III | I–VIPbc III | Vipiteno, Biblioteca Civica, Cod. III | Bolzano (Tirol) | 1514 (16i) | Vigil Raver’s Passion Play | Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

| Vip IV | I–VIPbc IV | Vipiteno, Biblioteca Civica, Cod. IV | Bolzano (Tirol) | 15mx | Bolzano Passion Play | Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

| Vip VII | I–VIPbc VII | Vipiteno, Biblioteca Civica, Cod. VII | Tirol (Bolzano?) | 1520 (16i) | Tirol Passion Play | Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

| Vip XIV | I–VIPbc XIV | Vipiteno, Biblioteca Civica, Cod. XIV (XVI) | Vipitieno (Tirol) | 1486 (15x) | Lienhart Pfarrkircher’s Passion Play (Church Provost in Vipiteno) | Southern Bavarian Area and Black Forest |

| Wi 13427 | A–Wn 13427 | Wien, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. 13427 | Praha, Katedrála sv. Víta, Václava a Vojtěcha | 1334–1366 (14m) | Breviary | Bohemia |

| Wol 965 | D–W 965 | Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, Cod. Guelf. 965 Helmst. (Heinemann–Nr. 1067) | Braunschweig (Brunswick) Kollegiatstift St. Cyriacus? | 15 | Miscellany | Lower Saxony |

| Wol VII B 203 | D–Wa VII B 203 | Wolfenbüttel, Niedersächsisches Landesarchiv – Standort Wolfenbüttel, VII B Hs, Nr. 203 | Braunschweig (Brunswick) Kollegiatstift St. Cyriacus | 1314 (14i) | Lectionary | Lower Saxony |

| Wro 226a | PL–WRu 226a | Wroclaw, Bibliotheka Uniwersytecka, MS I Q 226a [Fragment] | Wroclaw | 14x/15i | Wroclaw/Breslau Easter Play | |

| Würz s/n | D–WÜubs s/n | Würzburg, Universitätsbibliothek, Bruno Stäblein Archiv, s/n | Vic, Seu St. Pere | 1278–1318 (13x/14i) | Processional | Catalonia and Occitanie |

| Zwi 1 15 3 | D–Z 1 15 3 | Zwickau, Ratsschulbibliothek, 15.1.3 (olim ms. I XV 3) | Jächymov, Latinské školy | 1520–1523 (16i) | Collection of plays by Rector Stephan Roth for the Latin School | Bohemia |

| Zwi 36 1 24 | D–Z 36 1 24 | Zwickau, Ratsschulbibliothek, 36.1.24 (olim ms. XXXVI I 24) | Jächymov, Latinské školy | 1520–1523 (16i) | Collection of plays by Rector Stephan Roth for the Latin School | Bohemia |

Notes

| 1 | From the perspective of strictly poetic diction, the cadence of the second verse would be 8pp (arómate) with an iambic rhythm. However, it is the melodic configuration itself—marked by a pressus on “cum” and a pes subpunctis resupinus emphasizing the syllable “a–”—that shifts the accent to a trochee (cúm liquído áromáte), thereby aligning it with the fourth verse of the stanza, which obviously repeats the same melody. |

| 2 | Dante Alighieri. De vulgari eloquentia, II, X, 4. (Squarotti et al. 1983, p. 512). |

| 3 | An interesting and thorough melodic analysis can be found in (Eberle 2023). |

| 4 | We refer to the most recent references cited in the Introduction for access to an extensive bibliography. |

| 5 | Some of the capitals attributed to this monastery, which was plundered in the 19th century, are now preserved in various museums, including the Museum of Art in Girona, the Castle Museum of Peralada, and the aforementioned Cluny Museum in Paris. |

| 6 | We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Miss Nadia Smirnova, art historian and researcher at the Complutense University of Madrid, for her generosity in providing this reference. |

References

- Abajo Vega, Noemí. 2005. Arte románico y teatro litúrgico: Las posibilidades de un método en el estudio de la iconografía. Codex aquilarensis: Cuadernos de investigación del Monasterio de Santa María la Real 21: 108–31. [Google Scholar]

- Amstutz, Renate. 2002. Ludus de Decem Virginibus. In Recovery of the Sung Liturgical Core of the Thuringian Zehnjungfrauenspiel. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Anglès, Higini. 1935. La Música a Catalunya fins al Segle XIII. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans/Biblioteca de Catalunya. [Google Scholar]

- Arlt, Wulf. 1986. Nova cantica. Grundsätzliches und Spezielles zur Interpretation musikalischer Texte des Mittelalters. Basler Jahrbuch für historische Musikpraxis 10: 13–62. [Google Scholar]

- Arlt, Wulf. 1990. Das eine Lied und die vielen Lieder. Zur historischen Stellung der neuen Liedkunst des frühen 12. Jahrhunderts. In Festschrift Rudolf Bockholdt zum 60. Geburtstag. Edited by Norbert Dubowy and Sören Meyer-Eller. Pfaffenhofen: Ludwig, pp. 113–27. [Google Scholar]

- Avalle, Arco Silvio, and Raffaello Monterosso, eds. 1965. Sponsus: Dramma delle Vergini Prudenti e delle Vergini Stolte. Milano: R. Ricciardi. [Google Scholar]

- Batoff, Melanie Laura. 2013. Re-Envisioning the Visitatio Sepulchri in Medieval Germany: The Intersection of Plainchant, Liturgy, Epic, and Reform. Ph.D. thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Berthold, Margot. 1972. A History of World Theater. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bonastre i Bertran, Francesc. 1982. Estudis sobre la Verbeta: (La Verbeta a Catalunya durant els Segles xi–xvi). Tarragona: Publicacions de la Diputació de Tarragona. [Google Scholar]

- Camprubí Vinyals, Adriana. 2020. Repertorio Métrico y Melódico de la Nova Cantica (Siglos XI, XII y XIII). De la Lírica Latina a la Lírica Románica, 2 Vols. Ph.D. thesis, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Cantus. n.d. Available online: https://cantus.uwaterloo.ca (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Castro Caridad, Eva. 1989. El texto y la función litúrgica del “Quem Quaeritis” Pascual en la Catedral de Vic. Hispania Sacra 41: 399–420. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Caridad, Eva. 1997. Teatro Medieval 1. El Drama Litúrgico. Barcelona: Crítica. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Caridad, Eva. 2019. Els Drames Litúrgics Pascuals a La Catedral De Vic. In La Catedral de Sant Pere de Vic. Edited by Marta Crispí, Sergio Fuentes and Judith Urbano. Montserrat: Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat, pp. 141–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Adam S. 2000. The Uta Codex. Art, Philosophy, and Reform in Eleventh-Century Germany. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Boor, Helmut. 1967. Die Textgeschichte der Lateinishen Osterfeiern. Tübingen: Niemayer. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, Richard. 1958. The Liturgical Drama in Medieval Spain. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Dreves, Guido Maria, Clemens Blume, and Henry Marriott Bannister. 1886. Analecta Hymnica Medii Aevi. Leipzig: O. R. Reisland, vol. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Dronke, Peter. 1994. Nine Medieval Latin Plays. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dürre, Konrad. 1915. Die Mercatorszene im Lateinisch-Liturgischen Altdeutschen und Altfranzösischen Religiösen Drama. Ph.D. thesis, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Eberle, Michael. 2019. Eamus mirram emere: Der Musikalische Beitrag zu Ritualität und Theatralität in den Frühen Osterfeiern von Vic. Master’s thesis, Universität Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Eberle, Michael. 2023. Von “veniunt” zu “eamus”. Zur semantischen Funktion der Melodien im frühen Osterspiel. Kirchenmusikalisches Jahrbuch 107: 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Evers, Ute, and Johannes Janota, eds. 2013. Die Melodien der Lateinischen Osterfeiern: Editionen und Kommentare. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Garrigosa i Massana, Joaquim. 2003. Els Manuscrits Musicals a Catalunya fins al Segle XlII (L’evolució de la Notació Musical). Lleida: Institut d’Estudis IIerdencs. [Google Scholar]

- González Montañés, Julio I. 2002. Drama e Iconografía en el Arte Medieval Peninsular (siglos XI–XV). Ph.D. thesis, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Gros i Pujol, Miquel S. 1999. Els Troper Prosers de la Cathedral de Vic: Estudi i Edició. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans. [Google Scholar]

- Gros i Pujol, Miquel S., ed. 2010. Troparium Prosarium Ecclesiae Cathedralis Vicensis: Edició Facsimilar Monocroma amb Introducció i Índexs. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, Sigfrid. 1972. Salbenkauf der Frauen. In Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie, Vol. 4. Allgemeine Ikonographie. Edited by Engelbert Kirschbaum. Rome, Freiburg, Basel and Vienna: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Katritzky, M. A. 2007. Text and Performance. Medieval Religious Stage Quacks and the Commedia dell’Arte. In Transformationen des Religiösen: Performativität und Textualität im geistlichen Spiel. Edited by Ingrid Kasten and Erika Fischer-Lichte. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 99–126. [Google Scholar]

- Katritzky, M. A. 2018. Les représentations du charlatan pendant la première modernité, et leur origine dans la scène du marchand du théâtre religieux. In Théâtre et Charlatans dans l’Europe Moderne. Edited by Beya Dhraïef, Éric Négrel and Jennifer Ruimi. Paris: Presses Sorbonne Nouvelle, pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Katritzky, M. A. 2020. The Itinerant Healer as a Stage Role: Its Origins in Religious Drama. In Enacting the Bible in Medieval and Early Modern Drama. Edited by Eva von Contzen and Chanita Goodblatt. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurmann, Peter. 2016. Le Saint-Sépulcre de Constance du XIIIe siècle, réceptacle eucharistique au service du “pèlerinage intérieur”. Reti Medievali Rivista 17: 399–416. [Google Scholar]

- Lipphardt, Walther. 1975–1990. Lateinischen Osterfeiern und Osterspiele. Berlin: De Gruyter, vol. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn, Jeremy. 2018. Nova Cantica. In The Cambridge History of Medieval Music. Edited by Mark Everist and Thomas Forrest Kelly. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, I, vol. 2, pp. 147–75. [Google Scholar]

- Lorés i Otzet, Imma. 1986. L’escena de la venda de perfums en la visita de les Maries al Sepulcre i el drame litúrgic pasqual. In Lambard. Estudis d’Art Medieval. Barcelona: Amics de l’Art Romànic. Institut d’Estudis Catalans, vol. 2, pp. 129–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lorés i Otzet, Imma. 1991. El monestir de Sant Cugat del Vallès. Escultura del claustre i de l’església. In Catalunya Romànica, XVIII. El Vallès Occidental. El Vallès Oriental. Barcelona: Enciclopèdia Catalana, pp. 169–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lorés i Otzet, Imma. 1994. El Claustre Romànic de Sant Pere de Rodes: de la Memòria a les Restes Conservades: Una Hipòtesi Sobre la Seva Composició Escultórica. Lleida: Universitat de Lleida. [Google Scholar]