Historical Landscape: A Methodological Proposal to Analyse the Settlements of Monasteries in the Birth of Portugal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Literature Review

3. Methods and Data

Criteria Used to Characterize and Analyze the Distribution of Monasteries in Mainland Portugal

4. Results

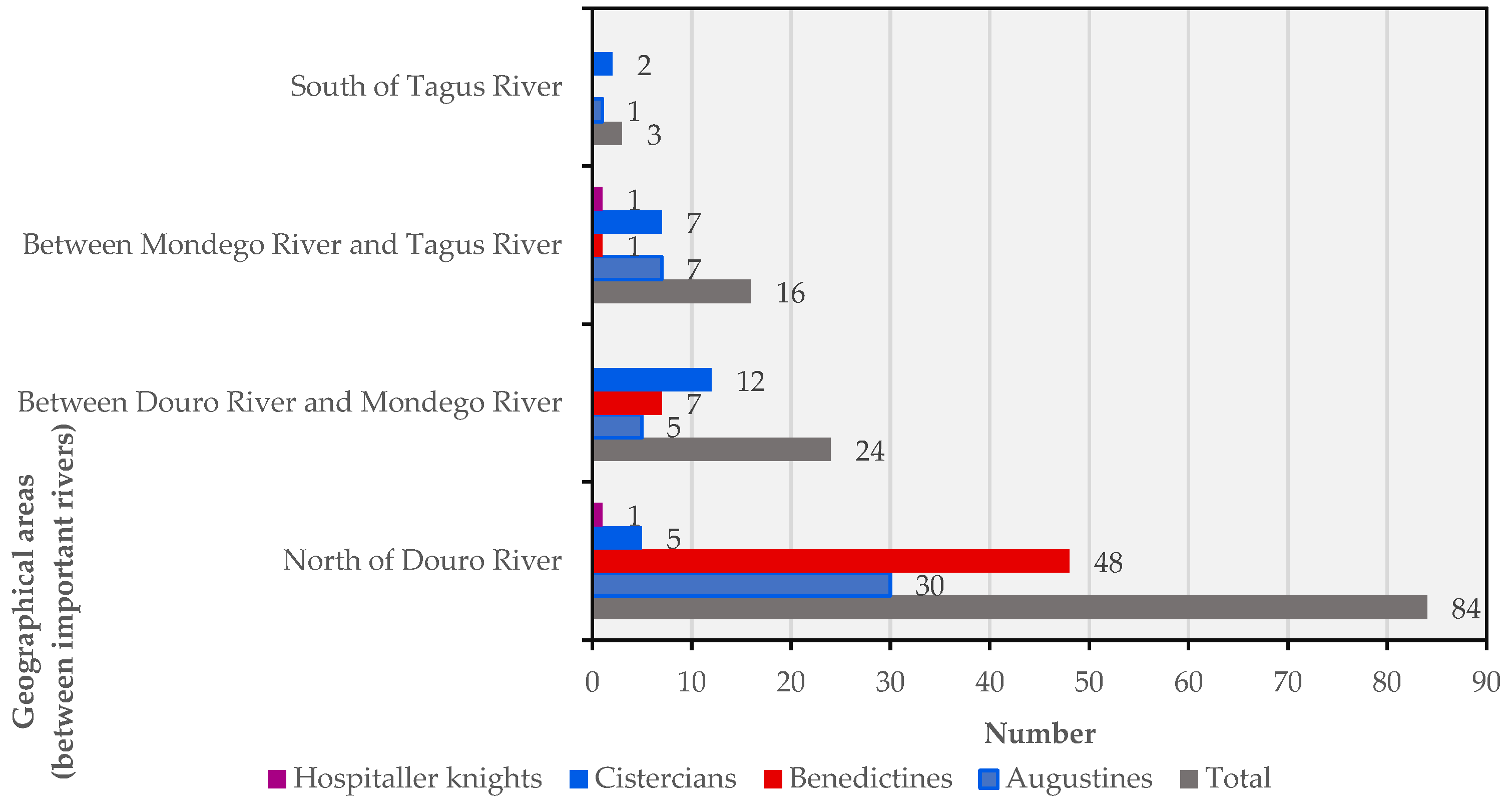

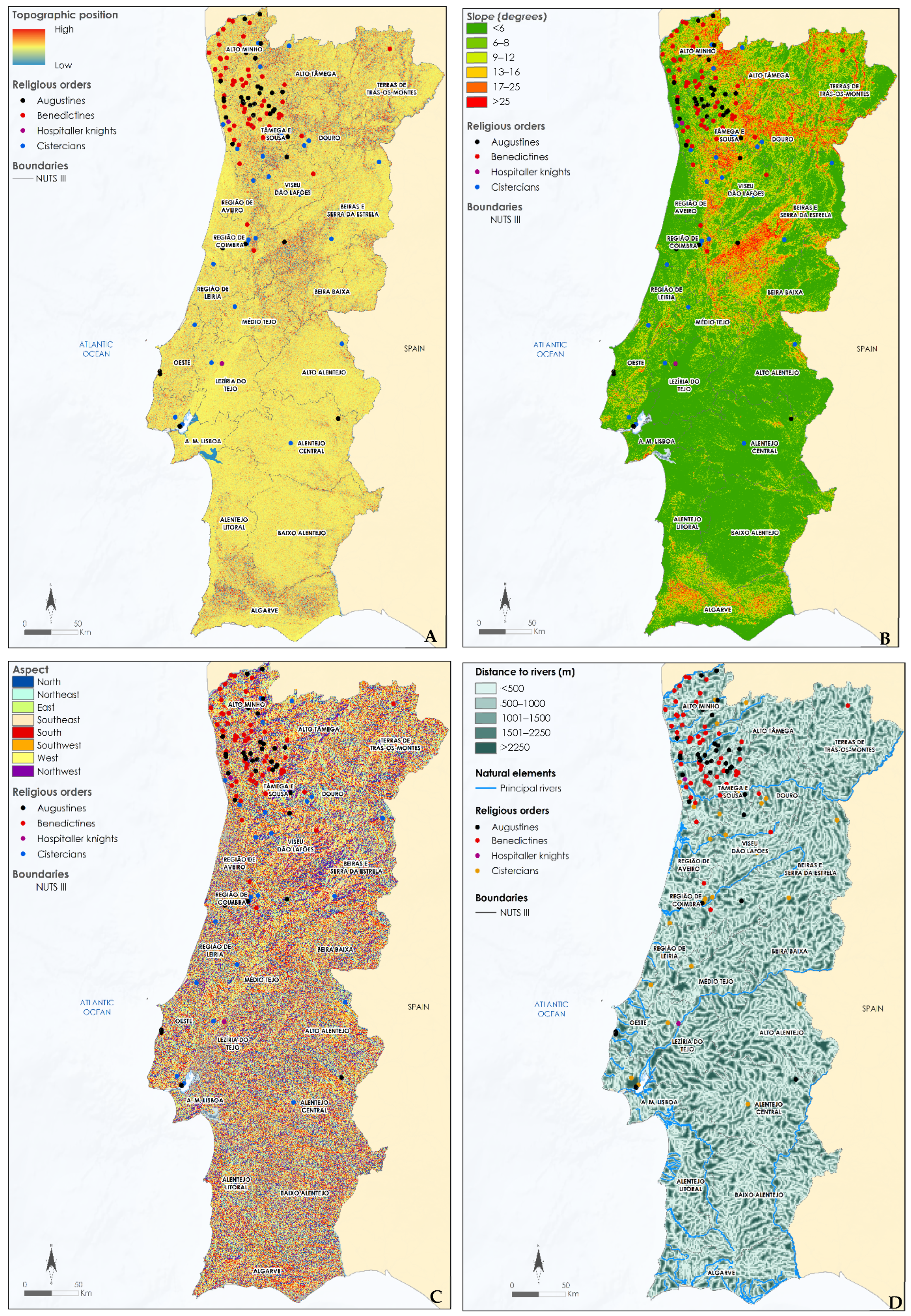

4.1. Distribution of Religious Orders in Early Medieval Portugal (12th Century)

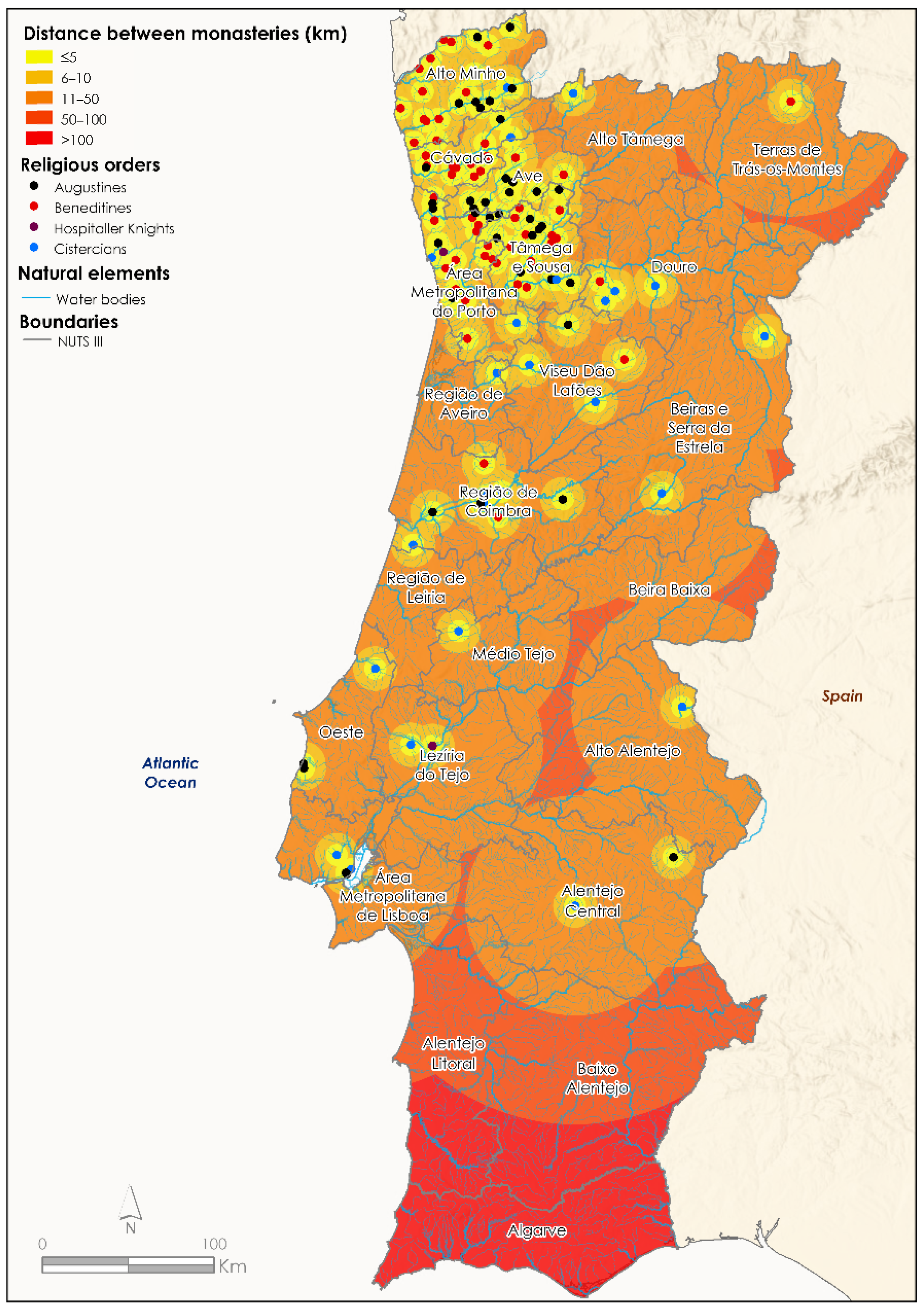

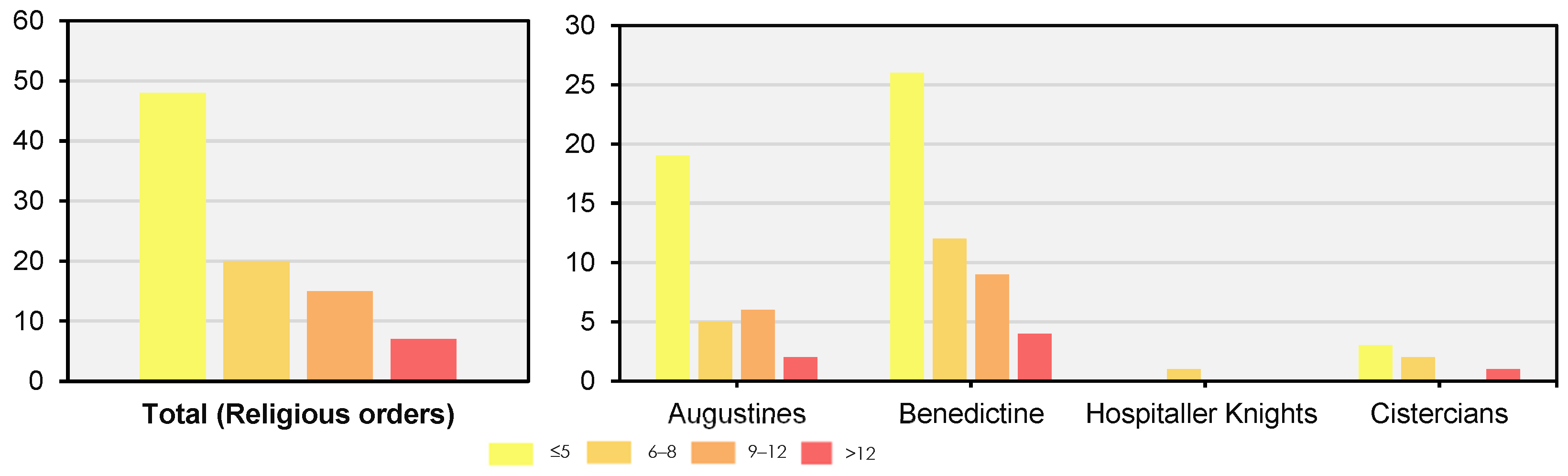

4.2. A Detailed Analysis of the Northwestern Monasteries

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adade Williams, Portia, Likho Sikutshwa, and Sheona Shackleton. 2020. Acknowledging indigenous and local knowledge to facilitate collaboration in landscape approaches—Lessons from a systematic review. Land 9: 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, Krisztina. 2020. Introducing historical landscape in the cultural heritage conservation through the example of the Tokaj wine region in Hungary. AUC Geographica 55: 112–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroca, Mário Jorge. 2003. História das campanhas. Nova História Militar de Portugal 1: 22–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bartley, Ken, and Bruce M. S. Campbell. 1997. Inquisitiones Post Mortem, GIS, and the creation of a land-use map of medieval England. Transactions in GIS 2: 333–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrica, Silvia. 2022. El Paisaje Altomedieval de la Sierra de Guadarrama a través de dos casos de estudio: Cancho del Confesionario y la Dehesa de Navalvillar. Cuadernos de Arqueología de la Universidad de Navarra 30: 73–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan, Andrew, James Conolly, Christian Hennig, Alan Johnston, Alessandro Quercia, Lindsay Spencer, and Joanita Vroom. 2013. Measuring chronological uncertainty in intensive survey finds: A case study from Antikythera, Greece. Archaeometry 55: 312–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Zhenrao, Chaoyang Fang, Qian Zhang, and Fulong Chen. 2021. Joint development of cultural heritage protection and tourism: The case of Mount Lushan cultural landscape heritage site. Heritage Science 9: 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrero-Pazos, Miguel. 2023. Arqueología computacional del territorio. Métodos y técnicas para estudiar decisiones humanas en paisajes pretéritos. Summertown: ArchaeoPress Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Carrero-Pazos, Miguel, Benito Vilas-Estévez, and Alia Vázquez-Martínez. 2018. Digital imaging techniques for recording and analysing prehistoric rock art panels in Galicia (NW Iberia). Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage 8: 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, Santiago, and Iñaki Martín Viso. 2005. The local articulation of central power in the north of the Iberian Peninsula (500–1000). Early Medieval Europe 13: 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Badia, Xavier, Marta Sancho, and Maria Soler. 2017. Monacato femenino y paisaje. Los monasterios de clarisas dentro del espacio urbano en la Catalunya medieval. In Clarisas y dominicas. Modelos de implantación filiación promoción y devoción en la Península Ibérica Cerdeña Nápoles y Sicilia. Firenze: Firenze University Press, pp. 449–86. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. 2000. European Landscape Convention. Available online: http://www.convenzioneeuropeapaesaggio.beniculturali.it/uploads/Council%20of%20Europe%20-%20European%20Landscape%20Convention.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Council of Europe. 2005. Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680083746 (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- De Reu, Jeroen, Jean Bourgeois, Machteld Bats, Ann Zwertvaegher, Vanessa Gelorini, Philippe De Smedt, Wei Chu, Marc Antrop, Philippe De Maeyer, Peter Finke, and et al. 2013. Application of the topographic position index to heterogeneous landscapes. Geomorphology 186: 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Reu, Jeroen, Jean Bourgeois, Philippe De Smedt, Ann Zwertvaegher, Marc Antrop, Machteld Bats, Philippe De Maeyer, Peter Finke, Marc Van Meirvenne, Jacques Verniers, and et al. 2011. Measuring the relative topographic position of archaeological sites in the landscape, a case study on the Bronze Age barrows in northwest Belgium. Journal of Archaeological Science 38: 3435–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanta, Václav, Jaromír Beneš, Jan Zouhar, Volha Rakava, Ivana Šitnerová, Kristina Janečková Molnárová, Ladislav Šmejda, and Petr Sklenicka. 2022. Ecological and historical factors behind the spatial structure of the historical field patterns in the Czech Republic. Scientific Reports 12: 8645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes, João Luís Inglês, Maria Filomena Andrade, and Ana Maria S. A. Rodrigues. 2021. Mosteiros e conventos no Portugal medieval: Vida espiritual e lógicas de implantação. SVMMA 15: 8–34. Available online: https://revistes.ub.edu/index.php/SVMMA/article/view/31799/31595 (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Fortó García, Abel. 2021. La arquitectura religiosa y la arquitectura doméstica en la configuración del paisaje medieval del Principat d’Andorra (siglos X–XIV). Archeologia dell’Architettura XXVI: 139–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, Vincent, and Martijn van Leusen. 1995. 367 Postscript—GIS, environmental determinism and archaeology: A parallel text. In Archaeology and Geographic Information Systems: A European Perspective. Boca Raton: CRC Press, pp. 367–82. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS-IFLA. 2017. Principles Concerning Rural Landscapes as Heritage. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/General_Assemblies/19th_Delhi_2017/Working_Documents-First_Batch-August_2017/GA2017_6-3-1_RuralLandscapesPrinciples_EN_final20170730.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Llobera, Marcos. 2015. Working the digital: Some thoughts from landscape archaeology. In Material Evidence: Learning from Archaeological Practice. Edited by Robert Chapman and Alison Wylie. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 173–88. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, José. 2017. A Igreja no tempo de D. Afonso Henriques. Alguns aspetos. In No tempo de D. Afonso Henriques. Reflexões sobre o primeiro século português. Coordinated by Mário Barroca. Porto: CITCEM—Centro de Investigação Transdisciplinar «Cultura Espaço e Memória», pp. 27–71. [Google Scholar]

- Martín Viso, Iñaki, José Antonio López Sáez, Reyes Luelmo Lautenschlaeger, and Francisco Javier San Vicente Vicente. 2022. Paisajes dinámicos y agencia local en el sur de la Meseta del Duero medieval: El caso de Monleras (Salamanca España). Lucentum XLI: 321–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Tejera, Artemio Manuel. 2017. La organización de los monasterios hispanos en la Alta Edad Media (ss. IX–X): Los espacios de la aldea espiritual. Hortus Artium Medievalium 1: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattoso, José. 2001. Identificação de um país. Obras completes. Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores, pp. 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Nora, Mechtild Rössler, and Pierre Marie Tricaud. 2009. World Heritage Cultural Landscapes: A Handbook for Conservation and Management. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000187044 (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Parcero Oubiña, César, and Pastor Fábrega Álvarez. 2006. Diseño metodológico para el análisis locacional de asentamientos a través de un SIG de base Ráster. In La aplicación de los SIG en la arqueología del paisaje. Coordinated by I. Grau. Alicante: Serie Arqueológica, pp. 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Quirós Castillo, Juan Antonio. 2021. Arquitectura del poder y el poder de la arquitectura. Las “petrificaciones” de las arquitecturas en Álava y Treviño entre los siglos IX–XIII. Archeologia dell’Architettura 2021: 159–72. [Google Scholar]

- Rosas, Lúcia, Maria Leonor Botelho, and Nuno Resende. 2013. Ermida do Paiva: Reflexões e problemáticas. Revista da Faculdade de Letras Ciências e Técnicas do Património XII: 245–62. [Google Scholar]

- Rouco Collazo, Jorge. 2021. Las fortificaciones medievales de la Alpujarra Alta desde la Arqueología de la Arquitectura y del Paisaje. Ph.D. thesis, University of Granada, Granada, Spain. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10481/71115 (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Sánchez-Pardo, José Carlos, Miguel Carrero-Pazos, Marcos Fernández-Ferreiro, and David Espinosa-Espinosa. 2020. Exploring the landscape dimension of the early medieval churches. A case study from A Mariña region (north-west Spain). Landscape History 41: 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler Sala, Maria. 2019. More than Maps. The Use of GIS in the Economic and Territorial Study of the County of Barcelona and the Analysis of Spiritual Landscapes in the Middle Ages. Revista De Humanidades Digitales 3: 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobalina-Pulido, Leticia Tobalina. 2022. Étudier les dynamiques de peuplement entre l’Èbre moyen et les Pyrénées occidentales durant l’Antiquité tardive (III–VIIe siècle) avec les SIG. Première approche. SPAL 31: 269–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 1992. World Heritage Convention. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/convention/ (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- van Lanen, Rowin J., Roy van Beek, and Menne C. Kosian. 2022. A different view on (world) heritage. The need for multi-perspective data analyses in historical landscape studies: The example of Schokland (NL). Journal of Cultural Heritage 53: 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavrouchová, Hana, Antonín Vaishar, and Veronika Peřinková. 2022. Historical Landscape Elements of Abandoned Foothill Villages—A Case Study of the Historical Territory of Moravia and Silesia. Land 11: 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Yi, Luo Guo, Sulong Zhou, Fen Li, and Bingsheng Wu. 2016. GIS-based distribution and land use pattern of the monasteries in Guoluo Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in China. In Geo-Informatics in Resource Management and Sustainable Ecosystem, Paper Presented at Third International Conference, GRMSE 2015, Wuhan, China, October 16–18. Revised Selected Papers 3. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 190–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Goal | Method Used | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Altitude | Pattern elevation | DEM analysis | Raw variables |

| Slope | Patterns in slope | ||

| Aspect | Patterns in aspect | ||

| Hydrology | Spatial relationship between churches and rivers | Distance from rivers | |

| Topographic prominence | Topographic prominence of the landscape | Modelled variables |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vaz de Freitas, I.; Lopes, H.S.; Albuquerque, H. Historical Landscape: A Methodological Proposal to Analyse the Settlements of Monasteries in the Birth of Portugal. Religions 2024, 15, 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15101158

Vaz de Freitas I, Lopes HS, Albuquerque H. Historical Landscape: A Methodological Proposal to Analyse the Settlements of Monasteries in the Birth of Portugal. Religions. 2024; 15(10):1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15101158

Chicago/Turabian StyleVaz de Freitas, Isabel, Hélder Silva Lopes, and Helena Albuquerque. 2024. "Historical Landscape: A Methodological Proposal to Analyse the Settlements of Monasteries in the Birth of Portugal" Religions 15, no. 10: 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15101158

APA StyleVaz de Freitas, I., Lopes, H. S., & Albuquerque, H. (2024). Historical Landscape: A Methodological Proposal to Analyse the Settlements of Monasteries in the Birth of Portugal. Religions, 15(10), 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15101158