1. Introduction

Ecclesiology from a practical theological perspective denotes lived ecclesiology at the micro level of the local church, the meso level of the national and continental ecclesial structures, and the macro level of the worldwide Church governance (

van der Ven 1996;

Midali 2011). In fact, the synodal process engaging the Catholic Church—to which we refer when using the term ‘Church’ in this paper—has evolved at these three levels: the diocesan–national phase, from October 2021 to April 2022; the continental phase, from September 2022 to March 2023; and the universal church phase, in October 2023 and in October 2024. This long-drawn process (2021–2024) is considered to foster synodality as a constituent trait of the Church, as envisioned by the Second Vatican Council. Intriguingly, the aim of the ongoing synodal process is to reinforce the synodal transformation of the Church (

Pope Francis 2013, n. 32).

The present synod has brought Christians of diverse cultures, ethnic communities, linguistic groups and nationalities to engage in a process that can be termed

inter gentes. The term

gentes refers not only to the peoples and nations who form the people of God, but also to those outside of it, the ‘gentiles.’ This

inter gentes process—as is known—seeks to address three intersecting features of synodality: communion (

communio), participation (

partecipatio) and mission (

missio). In other words, the synodal process is intended to review the current state of

communio,

partecipatio et missio inter gentes, with a view to reinforcing the synodal nature of the worldwide Church. More specifically, the synod aims to transform the largely uniform, centralized, hierarchical, clericalized, and

missio ad gentes Church into a Church that is polyhedral, communal, egalitarian, participative, and

missio inter gentes. Viewed from a cultural perspective, this means transforming an essentially monocentric, monocultural, patriarchal, and Westernized Church into a polycentric, intercultural, gender-inclusive, and global Church (

Pope Francis 2013, n. 32;

Midali 2008, pp. 75–94;

Luciani 2022, p. 37). Without aiming to reproduce the intense debate that is in progress, we limit ourselves to examining the crucial issue—to a great extent ignored—of the intercultural lived ecclesiology associated with the

inter gentes synodal focus on communion, participation and mission. Although the synodal journey appears to be appealing, the endogenous and exogenous ecclesial and societal differences implied in the

inter gentes discernment can render it a complex transformative process, entailing reciprocal enrichment and mutual critique at all levels, namely, at the micro, meso and macro levels (

Second Vatican Council 1964, n. 12;

Luciani 2022, pp. 56–57;

Czemy 2022).

Cognizant of these, on the basis of the theological reflections emerging in diverse ecclesial contexts, we first explore synodality as a transformative process arising from intercultural lived ecclesiology that engages the entire people of God (

Section 2). We then clarify the criteria underlying the synodal process of the

inter gentes discernment of the present, the future and the journeying in between (

Section 3). Against the backdrop of the theological framework of synodality and the criteria of discernment, we then critically summarize the challenges and prospects of

communio,

partecipatio et missio inter gentes emerging among the Asian episcopal conferences, and examine it in an intercultural dialogue with the results of an empirical study of Asians’ view on related questions featured in the German Synodal Way. Furthermore, with the view to exploring these issues further, we refer to some contextual empirical studies that focus on the themes of the Asian synodal process (

Section 4). We conclude by drawing attention to intercultural synodality as an ongoing, complex and transformative process.

3. Discerning through Inter Gentes Synodal Process

The core dynamics of the synodal process involves discernment grounded on the intercultural lived ecclesiology of the entire people of God in order to review the current state of the monocultural, clerical (male-domineering), centralized Church (

Pope Francis 2013, n. 32) and move towards an intercultural, egalitarian, polycentric Church in terms of

communio,

partecipatio et missio inter gentes at the micro, meso and macro levels. As mentioned above, the starting point is the acknowledgement that we have not lived the synodal process, and that we do not know how to live it; that we stand in need of

inter gentes encounters, of listening, discerning and creating a culture of ecclesial consensus (

Vélez 2022). Furthermore, in the contemporary context, we cannot ignore the modern sensibility of

homo democraticus, the appeal to human rights, communicative dissent and egalitarianism (

Faggioli 2022;

Anthony 2020a). With these observations in mind, we outline the dynamics of intercultural discernment entailing intercultural hermeneutics, critique and participation and, more specifically, diverse types of thinking.

3.1. Intercultural Approach to Discernment Dynamics

“Exercising discernment is at the heart of synodal processes and events” (

ITC 2018, n. 113). The term “discernment,” derived from the Latin

discretio and the Greek

phrónesis, is close to the meaning of the Indian term

viveka. These terms suggest the need to distinguish or discriminate in making proper judgments and prudent decisions, in accordance with conscience, rationality and wisdom. In the Indian tradition,

Swami Vivekananda (

1987, p. 232) and

Swami Chinmayananda (

1989, p. 22f) refer to

viveka as the faculty used in day-to-day decisions, brought to the level of the inner constitution of the subject; as the capacity to discriminate between what is real and unreal, true and false, permanent and impermanent. There is, in Hinduism, a fine tradition of critical inquiry, a constant injunction to conduct

viveka (discrimination), which implies both analysis and evaluation (

Antoine 1968, p. 30).

In the biblical tradition, discernment was considered as the faculty with which to distinguish between God’s revelation and other sources of knowledge. It was considered a form of grace, a gift given by God to individuals for the purpose of enlightening their community regarding what was good for their common life. In the reflection that ensued among early-century Church Fathers, namely, Evagrius Ponticus (c. 345–399) and John Cassian (c. 360–435), as well as the later writings of Bernard of Clairvaux (c. 1090–1153) and, in particular, Ignatius of Loyola (c. 1491–1556), the meaning of discernment shifted to the personal level of making life choices. However, in recent times, a renewed interest has arisen in viewing discernment as a communal process in the search for the common good (

Waaijman 2013;

ITC 2018, n. 113).

In the Cassian tradition, discernment implies exploring different perspectives on a given matter with a view to decision-making. Insofar as exploring multiple perspectives necessitates the views of others, discernment has a communitarian or social dimension. In the Cassian tradition, discernment matures through the following four stages (

Waaijman 2013):

Circumspection: The existence of multiple perspectives on a question requires space for ideas from different sources and persons. It also implies a distinction between the viable and the non-viable.

Introspection: This covers reflection and self-inquiry, at both the individual and the community level. The focus here is on evaluating alternative perspectives and their possible outcomes, going beyond (the ideological aspect of) what is known and opening up to (the utopian aspect of) how things could be. Becoming attuned to ultimate purpose and being open to new possibilities necessitate both peace of mind and the ability to change perspectives.

Intervision: This stage is marked by an exchange of arguments in the process of deliberation, which requires participants to be wise and willing to share learning experiences.

Decision: This final stage of discernment entails the judgement of which of the alternatives can be viewed as wise, sound and adequately representative of the ultimate purpose.

The link between decision-making and radical attunement to the ultimate purpose and, thus, the creation of new possibilities is crucial to the Cassian tradition of discernment. It is characterized by a process of deliberation, which encourages the participation of all members in decision-making. It follows that in the case of the synodal process, a climate of listening and dialogue permits the faithful to express their common perception (

consensus fidelium), leading to (collegial and/or papal) decision-taking, without disregarding the voices of the minority. A dissonant minority with intuition and an innovative outlook is required for ecclesial transformation. This can be held as a necessary condition for the exercise of

sensus fidei, which translates into a living sense of the Church (

sensus ecclesiae), which the people of God perceive as authentic witness of Tradition. The primacy of

sensus fidei permits the discernment of

sensus fidelium, in view of

consensus fidelium. To the extent that these engage sociocultural and linguistic resources, they can be termed as

sensus populi or

sensus inter gentes (

Czemy 2022;

Luciani 2022, pp. 46–50, 69, 87–99;

Noceti 2022b, pp. 164–74, 249–65;

2022a, p. 273;

Wijlens 2022, p. 50).

Consensus fidelium is not a question of reaching an accord among different positions, but rather of valuing and reconciling differences at a higher level, where the best of each can be conserved (

Pope Francis 2020b, p. 93). Furthermore, the process may not be unilinear; instead, incomprehension and conflict may form part of the learning process, depending on the sincerity of the moral agent (

Eckholt 2022, p. 160). It is conscience as the ethical center of the subject that warranties the dignity of the person. It represents the heart of personal identity and the temple of dialogue with the divine, the condition for knowing the moral truth and attaining the good (

Del Missier and Massaro 2022).

As examples of culturally marked discernment praxis, we may cite the Melanesian method of consensus and the African

Indaba method of dialogue—also used in the Anglican synodal praxis since 2008—which aim to gradually resolve the conflicting positions in decision-making processes by coming to know the experience of the other and strengthening relationships in a climate of prayer and listening (

Zaccaria 2022, pp. 107–12). Likewise, we may refer to the unique and inclusive qualities of the Malaysian

longhouse culture, the spirit of

goton-royong (voluntary mutual assistance), and the culture of dialogue and cooperation in decision-making (

CBCMSB 2022, pp. 8–10, 17).

In this vein, the synodal dynamics of discernment can be understood as evolving through three phases of practical theological methodology: the prophetic discernment of the challenges posed and faced by the current lived synodal praxis (kairological phase); the prophetic discernment of a more consonant and desirable synodal praxis (projective phase); and the prophetic discernment of the progressive steps or itinerary necessary for moving from the current state to the desired configuration of the synodal Church (strategic phase) (

Midali 2011;

ITC 2018, n. 113). Given the challenge of balancing between the prophetic and the institutional, between the personal and the communitarian, the role of practical theologians and experts in accompanying and refining the synodal process cannot be overlooked (

ITC 2018, n. 75;

Brighenti 2022;

de Roest 2020).

3.2. Intercultural Hermeneutics, Critique and Participation

The dynamics of discernment described above entail concrete modes of hermeneutics, critique and participation. Hermeneutics is a process of interpretation comprising multiple perspectives, arising from the cultural assumptions or the worldview of persons (

Scheuerer 2001). As these assumptions shape cultural meaning systems, the latter become resources for the inculturation of faith in the hermeneutic mode. Meaning systems, in turn, find expression in words, concepts and categories in one or more languages. When believers from different cultures interact and interpret, intercultural tension arises, which can purify or enrich the understanding of lived ecclesiology. The ensuing discussion and debate can reveal the limits of the concepts or categories used in interpretation. Through this intercultural engagement, a more refined and deeper understanding of ecclesial life can emerge. In this regard, languages—as the most abstract forms of culture, with their nuances and subtleties—can play a crucial role. Therefore, instead of limiting ourselves to translating the theological understanding emerging from Western linguistic contexts, we need to use local linguistic resources as tools for exploring the profundity of our lived ecclesial experience.

When Gospel values interact with cultural values and purify the latter, we can speak of inculturation in the critical mode. If the fruits of this inculturation in one local church are shared by other local churches, interculturation occurs. Cultures differ in their scales of values. When these scales of values are confronted with others and with the Gospel, they become resources for intercultural exchange. In this sense, the ethical and moral aspects of life are fundamental areas of intercultural dialogue. If the multicultural and globalizing context is not dealt with appropriately, the danger of ethical or religious relativism arises. Intercultural critique can be a permanent way of refining what it means to be authentically human and truly Christian (

Anthony 2016a).

Observable behavior, signs, symbols, gestures, rituals, and artistic artefacts are concrete means through which the meanings and values of a culture are expressed, shared and celebrated. When these are critically and creatively integrated into the life of a local church, inculturation occurs. When these inculturated elements of a local church are shared by other churches, there is the possibility of aesthetic and expressive interculturation. Exchanges in the expressive system, such as symbols, gestures and rituals, can become—beyond their mere utilization—occasions for participation in another culture. This participation can stimulate creativity in representing and expressing Christian meanings and values in an original and apt manner.

The modes of interculturality described above can be understood as evolving in terms of participation (i.e., identification or ratification) and critique (i.e., distinction or refutation), both of which entail hermeneutics, giving rise to creative advancement (i.e., symbiosis, convergence, integration or transformation) with new possibilities for the ecclesial faith and local cultures. In this sense, interculturality is a complex process of discernment, through which cultural heritages are reciprocally ratified, challenged and transformed, just as ecclesial heritages are confirmed, tested and enriched. In this manner, intercultural transformation enters the structural realm of social and ecclesial life, reaching up to the material level of ecological and economic reality. This innovative and transformative discernment is the distinct hallmark of interculturality (

Anthony 1997;

Corpas de Posada 2022).

3.3. Types of Inter Gentes Thinking Underlying the Discernment Process

A worldwide

inter gentes discernment process requires that we become aware of the three types of thinking implicated in it: the

postulational (conceptual), which aims at defining; the

psychical, which lays an emphasis on intuition; and the

relational, which deciphers mutual presence. The first is said to be the characteristic of the Western mind, the second of the Eastern mind, and the third of the African and Chinese mind (

Hesselgrave 1978, pp. 204–9;

Hesselgrave and Rommen 1989, p. 205f). Although thinking postulationally, psychically and relationally are basic to all epistemological processes, it might be stated that in the postulational type, the focus is on the object known, while in the psychical type, it is on the knowing subject and, in the relational type, it is on the rapport between the knowing subject and the known object. If we were to place these three ways of knowing in concentric circles from the inner to the outer levels, in an Asian mind, the order would be as follows: psychic experience, concrete relationships and abstract concepts. In a Western mind, they would be in the reverse order: abstract concepts, concrete relationships and psychic experience. In an African or Chinese mind, the order would be as follows: concrete relationships, abstract concepts and psychic experience (

Hesselgrave 1978, p. 208f).

The Western extrospective mind generally tends to occupy itself with exteriorization, objectification, research and scientific progress; its thinking tends to be positive, historical and social. The dynamics of this thinking process, grounded in the principle of non-contradiction, tend to be disjunctive, i.e., characterized by an

either–

or logic. In this sense, the Western mind is essentially involved in exclusive or analytic thinking. The Eastern introspective mind, by contrast, tends to occupy itself with interiorization and interior search; consequently, it tends to be metaphysical, psychological and spiritual. Founded on the principle of identity, it is characterized by a conjunctive logic, i.e., a

both–

and logic. In this sense, the Eastern mind is essentially involved in what may be called inclusive or synthetic thinking (

Irudayaraj 1992, p. 117;

Wilfred 1991, pp. 156–60;

1995, pp. 186–87). The third type, i.e., the relational type, in a way captures the relationship between the subject and the object in symbolic or narrative forms: myths, stories, parables, etc. This thinking tends to be what might be called pluralistic or analogical, based on a

like–

unlike logic. With regards to the latter, the consistent use of the metaphors of Church-as-tent, bridge-building and taking off the shoes in the Final Document of the Asian Continental Assembly on Synodality is a case in point (

FABC 2023, n. 36–38, 110, 152, 154, 173, 180–85).

In a worldwide synodal discernment process, it is indispensable that we become attuned to the intersection of postulational, psychic and relational thinking. Fostering participation means enabling those who hold different views based on different modes of thinking to express themselves. Dialogue involves the coming together of diverse views, without excluding anyone, even if those who force us to consider new perspectives seem to run counter to current thinking. Allowing persons to speak out with authentic courage and honesty (

parrhesia) is indispensable for the discernment process. Humility in listening, openness to newness and conversion (

metanoia) or to paradigm shifts are vital to rise above prejudices, stereotypes, self-sufficiency and hidden ideologies and contribute to the unceasing process of

ecclesiogenesi, of constantly building up the Church (

SGSB 2021b, n. 2.2.;

CBCK 2022, p. 34;

SMC 2022, p. 76;

PCBC 2022, p. 44;

ITC 2018, n. 105, 120;

Luciani 2022, pp. 34, 39, 98, 108–12).

Insofar as the cognitive dynamics of interpretation and evaluation are closely bound to local languages, their specific nuances should not be watered down or lost in translation, mostly into European languages (limited to Latin alphabets, with the exception of Greek). In this regard, the great sophistication, wealth and merit of Asian languages—comprising over 2300 spoken languages (

FABC 2023, n. 1) and over 280 writing systems—in nurturing religious acumen cannot be ignored. It cannot be denied that the origin and development of Asian religions are intrinsically associated with the flourishing of multiple linguistic traditions. The languages—or codes—we use play a significant role in the way we perceive the world, the insights we have and the decisions we make; they serve as tools for organizing, processing and structuring our thinking (

Marian 2023). For these reasons, we need to take stock of local languages along with types of thinking in the intercultural discernment of synodal values and visions present in local cultures (

CBCP 2022, pp. 71–73).

4. Intercultural Synodality with Reference to the Asian Context

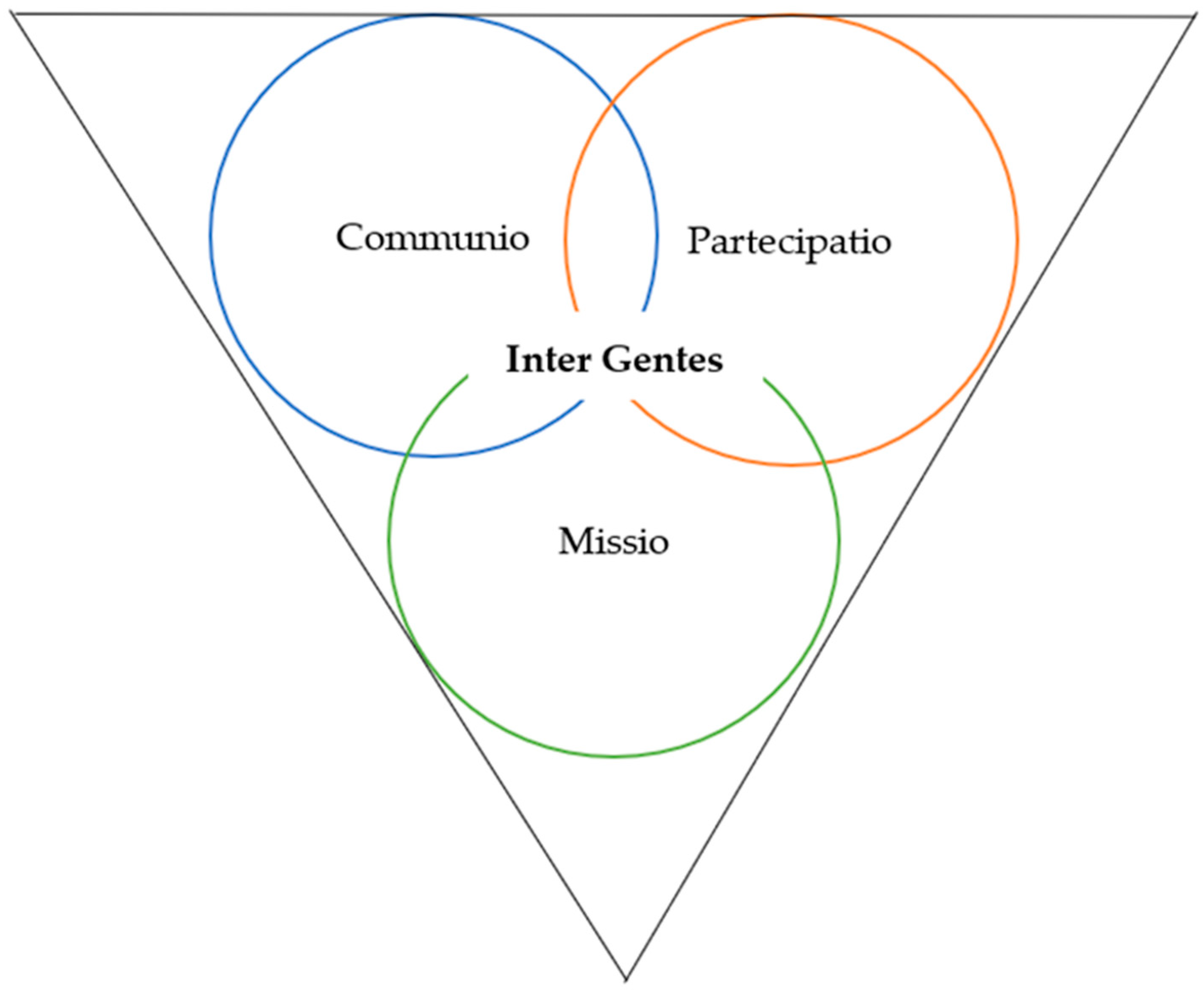

The previous sections offered some insights into the complexity of the synodal process encompassing the successive stages of discernment (circumspection, introspection, intervision and decision), distinct modes of intercultural dynamics (hermeneutics, critique, and participation) and characteristic ways of thinking (analytic, synthetic, and analogical). We can assume that these intersecting facets of lived synodality,

sentire cum Ecclesia, are operative in the synodal features of communion, participation and mission (

Figure 1), embedded in the diverse religio-cultural, socio-political and ecological-economic spheres of local contexts (

ITC 2018, n. 108). In our case, the reference is to the Asian context, with its religious, cultural and socio-economic pluralism. To the extent that the Asian church seeks to be embedded in this pluralistic context, it needs to engage in inculturizing, dialogic and humanizing synodal praxis (

Anthony 1997,

2014;

Midali 2008).

Although all contemporary world religions, including Christianity, are of Asian origin, Christianity, which has 298 million followers in Asia (6.53%; Catholics comprise 3.31%) is a minority religion in most Asian countries (

FABC 2023, n. 1), such as Myanmar (6.2%), India (2.3%), Mongolia (2.1%), Pakistan (1.5%), Thailand (1.17%) and Bangladesh (0.3%), with the exception of Singapore (18.9%), South Korea (29.2%), the Philippines (88.7%), and East Timor (98%). Christianity’s minority status in most Asian countries, despite the missionary efforts at its origin, raises the question of its survival or its reduction to a ghetto. Religious diversity in Asia is closely linked to cultural diversity, as religion and culture are bound to each other in an

advaitic (non-dual) bond, as the soul is to the body (

Panikkar 1991). Instead, a range of socio-political and ecological–economic systems have resulted in rapidly developing societies with widespread poverty and ecological threats: currently, about one billion people are beneath the poverty line of USD 2.15 per day, with 320 million living in extreme poverty (

FABC 2023, n. 3–8). This explains why, in the synodal process of the Asian national and regional bishops’ conferences, three transversal perspectives ran across the discussion, namely, dialogue with cultures, religions and the poor, which were previously identified by the first assembly of the Federation of Asian Bishops Conferences (FABC I), in 1974. In other words, inculturizing, interreligious and humanizing perspectives—as discussed below—emerge in varying degrees in the three intersecting features of

Communio,

Partecipatio et Missio inter gentes. These perspectives suggest an Asian approach to nourishing deeper communion, fuller participation and fruitful mission (

SGSB 2021b).

To analyze the intercultural synodality emerging through the Asian church, we refer to the sixteen Synthesis Reports of the Synod of Bishops (2021–2023) and the Final Document of the Asian Continental Assembly on Synodality (

FABC 2023). It is remarkable that in countries such as Bangladesh, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia–Singapore–Brunei, Philippines and Thailand, empirical methods were employed in the synodal process, including survey questionnaires (printed or online), tiered consultations, focus-group discussions, in-depth interviews and drawings for children. Among the participants in the survey in Central Asia, foreign parishioners were also included (

CECAC 2022, p. 26). Separate online surveys were undertaken among members of other Christian denominations and people of other faiths in Brunei (

CBCMSB 2022, p. 14). In the Syro-Malabar Church, the Pastoral Animation Research and Outreach Centre (PAROC) supported the synodal structure through interdisciplinary research in general and psycho-social and pastoral–theological research in particular (

SMC 2022, pp. 68–69). An enormous effort was made to translate materials for the synodal process into local languages, given the importance of linguistic nuances and cultural sensitivity (

CECAC 2022, pp. 25–26). The diversity of opinions emerging in the Asian synodal process can be attributed to the diversity of ethnicities, cultures, languages and faith stages.

In order to place the themes that emerged in the Asian synodal process—already intercultural in many ways—in a wider intercultural engagement, we refer to the results of an empirical–theological study, “Synodal Way—Global Church Perspectives,” undertaken by Catholic Academic Exchange Service (Katholischer Akademischer Ausländer-Dienst—KAAD) and the Institute for the Global Church and Mission (Institut für Weltkirche und Mission—IWM), to solicit the views of Asians (in addition to respondents from other continents) on the basic themes of the German Synodal Assemblies held between 2021 and 2023. The quantitative online research undertaken from 1–17 April 2022 involved 599 respondents from 67 countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America, the Middle East and Eastern Europe. The sample was equally divided between men (56.6%) and women (43.4%). Almost nine-tenths of the respondents were lay people (88.3%) and Roman Catholics (89.2%). In the Asian context, seventy respondents participated in the quantitative research and eight of them participated in the qualitative-research focus group (for further details, see

Cerda-Planas 2023). Given that creative and scientific pathways involving theological faculties and research centers were also solicited, with a view to widening the discussion, we also refer to the findings of some of our empirical–theological research, associated with the synodal focus on communion, participation and mission. The significance of empirical–theological research in the synodal process is derived from the fact that these are based on the lived experiences of Christians and followers of other religious traditions, as

locus theologicus (

Wijlens 2022, p. 41;

Eckholt 2022, p. 155).

4.1. Communio Inter Gentes ad Intra et ad Extra

Above all, the synodal process is an exercise in

inter gentes synodality (

Paranhos and Ponte 2022), aiming at three objectives: fostering communion, increasing participation and relaunching the mission (

SGSB 2021a, n. 1;

Czemy 2022). The fostering of communion is not only

ad intra ecclesial, but also

ad extra, embracing other Christian denominations, other religions and the global world, viewing synodality as an interface between the Church and the world (

Martins Filho 2022). The new and eternal covenant, the God–human–cosmos covenant in Christ’s eternal embrace of the wood of the Cross and the outpouring of the Spirit, is the core of trinitarian communion (

ITC 2018, n. 116;

CET 2022, pp. 42, 43, 45) and the ecclesial communion of communities (

FABC 2023, n. 171). As

modus vivendi et operandi, namely, as a specific form of living and acting, communion is the fount of synodality and the underlying rationale of mission. Lived ecclesial communion results from sincere self-giving, union with God and union with brothers and sisters in Christ (

ITC 2018, n. 43). The mystery of married couples’ experiences of communion in the domestic church has its specific significance here, as well as parish communities composed of the former (

Noceti 2022b, pp. 174–78, 235–42). The reflection of the Asian synodal process—as discussed below—is particularly focused on the problems in and prospects of communion in Catholic families and parishes.

4.1.1. Communion in the Family

The first

locus of communion is the family, the domestic church, comprising the spouses, children and elderly relatives of the household (

KWI 2022, pp. 6, 9–10;

FABC 2023, n. 142). However, the growing reality in Central Asia, India, Malaysia, Myanmar, Laos, etc., is that of wounded and broken families, with separated, divorced and remarried couples; of single parents and live-in and polygamous partners; of the orphans and homeless children of dysfunctional families and anti-social personalities; and of victims of domestic violence, incest, honor killings, etc. (

CBCMSB 2022, p. 7;

CBCB 2022, pp. 12–13;

CCBI 2022, p. 38;

CELAC 2022, p. 60;

CBCM 2022, p. 22;

FABC 2023, n. 141, 155–56, 169). Furthermore, in the Indian context, young men and women show reluctant attitudes to married life, viewing it as obsolete and leading to bondage, overly conditioned by internet addiction, pornography, mental stress, etc. (

SMCMAC 2022, pp. 73, 76;

FABC 2023, n. 139–40). This state of affairs suggests the fear of the erosion of the basic Christian doctrines of family and morality (

CECAC 2022, pp. 31–32).

In the Indonesian and Indian contexts, there are mixed or interfaith marriages, in which one of the first difficulties experienced is the need to overcome differences in the ratification of these marriage ties. On the positive side, interfaith marriage ties create opportunities to exercise interfaith dialogue and collaboration (

KWI 2022, pp. 9–10;

CCBI 2022, p. 38;

FABC 2023, n. 123–26, 143). In Laos, mixed couples tend to practice two religions at the same time and bring up the question of double belonging: Is it necessary for individuals to give up their religion in such situations (

CELAC 2022, pp. 48, 50, 60)? Evidently, in contexts such as that of Thailand, Catholics married to persons of other faiths require proper formation—seminars and conferences—to instill faith, devotion, and unity in the family, and to grow in mutual understanding and respect for differences, since the family is a place of lived witness (

CBCT 2022, p. 31). In this vein, new lay movements, such as the Home Mission, the Judith Forum Movement (for widows), and the Missionary Couples of Christ, could be valued as contributing to the empowerment of family and social relationships (

SMC 2022, p. 69).

Interestingly, when the Asian respondents in the empirical study “Synodal Way—Global Church Perspectives” (

Cerda-Planas 2023) were asked if “it is right and important that the church’s teachings—generally and in the local context—deals so intensively with the topic of sexuality,” they demonstrated strong approval (mean 4.13, on a five-point scale, also used in other cases referred to below). In this respect, the Asian responses were similar to those of the Latin American (mean 4.16) and African (mean 4.20) respondents. In response to another statement, “It is correct and should remain so that, according to church teaching, sexuality may have its place only in a Catholic marriage blessed by the Church,” the Asian respondents manifested a lesser degree of approval (mean 3.43), probably due to the multireligious situations of some of their families. When asked “if in future diocesan priests should be able to choose whether they want to be celibate or whether they want to marry,” the Asian respondents manifested the lowest agreement tendency with regard to the possibility of married priests (mean 2.81) when compared to the respondents from the other continents. This was in contrast to the fact that one of the Asian synodal suggestions was that married priests might better understand the situations of families (

CECAC 2022, p. 30). On the other hand, when compared to the other respondents, Asia had the highest levels of agreement with regard to “the actuality and adequacy of priestly celibacy” (mean 3.40). The impact of the Asian religious heritage may be perceived here: although married priests are common among other religions, Asians have a deep respect for celibate monks and ascetics. Catholic secular and religious priests enjoy the esteem of the local people, even of non-Christians, for their total dedication to the divine manifested in their choice of celibacy.

The conversations with the Asian respondents during the qualitative phase of the research confirmed the findings of the assessment: celibacy is viewed as a key aspect and valued as a particular gift that is given for priests’ Christian witness and, as such, it should be safeguarded. Instead, giving priests the opportunity to marry would result in their becoming unable to adequately focus on their work in the Christian community. Married priests would be busy looking after their families and their communities, without being able to commit themselves completely to either. In the opinion of the Asian focus group, the commitment and absolute dedication of priests to their ecclesial service have an elevated value and need to be protected. Furthermore, the respondents also drew attention to the value of the Christian family as a witness to faith, unlike that of priests, but equally valuable, especially in the present times. In addition, the Asian participants also mentioned that sexuality was an issue that belonged exclusively to people’s private lives; since Asia is a region characterized by traditional cultures, there would not be high expectations regarding reforms of the current doctrine in this sector. Thus, the areas of family life, celibacy and the moral dimension of sexuality emerged as topics of synodal intercultural debate.

4.1.2. Communion in the Parish

The second basic

locus of communion, namely, the parish as a communion of communities, is challenged by diversity and differences based on ethnicity, culture and religion. Living in a multicultural society necessitates intercultural engagement, which entails the sharing of ideas and the acknowledgement of differences, with the aim of developing a deeper understanding of diverse perspectives and practices. This inclusive outlook needs to be fostered to overcome disbelief or mistrust among ethnic tribes that have suffered trauma or wounds in the past. In this regard, the Myanmar church augurs bridge-building amidst a plurality of cultural, ethnic and religious traditions. This entails capacity building among lay people for the specific tasks of dialoguing with people of other faiths, mediating in conflict situations and pro-actively contributing to organizations in civil society (

CBCM 2022, pp. 20–21, 31). As a consequence, parish boundaries are to be redefined—according to the Syro-Malankara Church—to include non-Catholics and non-Christians in their area (

SMCMAC 2022, p. 74). In the context of the Philippines, it is felt that the Church and

barangay (villages) should denounce the conflicts arising among tribes, between military and armed groups, etc. (

CBCP 2022, p. 63).

Discrimination based on caste, language, ethnicity and economic, academic and social status is not uncommon within Christian communities. Indian communities are of the view that diversity within the Church and society must become a source for celebration, eradicating various forms of discrimination and poverty (

CCBI 2022, p. 38;

SMCMAC 2022, p. 79;

FABC 2023, n. 128–29, 144–45). This would imply the proper representation of

Dalit faithful and of other marginalized groups in ecclesial and civil structures (

CCBI 2022, p. 42;

SMC 2022, p. 54).

Among some local communities, there is a lack of interaction, due to language barriers, with foreign believers. Since the Japanese and Korean Societies are increasingly multinational, there is a need to advocate praying together across nationalities and cultures (e.g., Philippines and Vietnam). In fact, migrants and their families desire to attend eucharistic celebrations—the locus of communion—without experiencing language or political barriers. The acceptance of North Korean defectors as companions in the synodal process was a positive response in this regard (

CBCJ 2022, pp. 19–22, 29;

CBCK 2022, pp. 33, 36). The presence of foreign Christians, namely, migrant workers and tourists, from different parts of Asia and the rest of the world, requires that local community be open to dialogue with other cultures on the basis of love, justice and peace-making (

CBCT 2022, p. 38).

In the context, for example, of Indian and Thai parish communities, Basic Christian/Ecclesial Communities emerge as a new way of being Church. In this vein, the Asian phenomenon of Basic Human Communities includes members of other religious traditions living in the same neighborhood to promote justice and the common good (

Quevedo 2022;

CCBI 2022, pp. 47, 49;

CBCT 2022, p. 31;

KWI 2022, p. 14;

FABC 2023, n. 136, 150). Furthermore,

Khrista-Bhaktas (Devotees of Christ) exemplify new communities emerging in some Indian dioceses, constituted by people who love and worship Christ, without wishing to receive baptisms for social and political purposes. With their deep faith in and personal relationship with Christ, they offer a convincing form of witness to other Christian communities (

CCBI 2022, p. 38;

SMC 2022, p. 58). The emergence of

Khrista-Bhaktas, mixed marriages, etc., raises the question of whether different phases or levels of ecclesial belonging can be envisaged (

van Leeuwen 1984).

While the shaping of linguistic, ethnic, social, religious and national identities by diversity can contribute positively to Asian societies and churches, it can also give rise to discrimination and violence (

FABC 2023, n. 51). In the context of the International Research Project “Values, Religion and Human Rights” (

Anthony 2022), 942 senior-school students differing in their religious identities from Tamil Nadu responded to a specific section meant only for the Indian students on diversity and discrimination. The findings showed that the students clearly agreed that religious, caste, gender and racial discrimination are opposed to both their understanding of human rights and their religious beliefs. However, they seemed to view the culture of discrimination as slightly more opposed to human rights than to their religious beliefs. We also found that Christians are significantly more sensitive than Hindus to gender discrimination, in relation to both their understanding of human-rights values and their religious beliefs. Similarly, they are more sensitive to religious discrimination than Hindus on the basis of their religious beliefs. On these questions, the Muslim respondents were between the other two religious groups. Overall, Christians seem to be particularly sensitive to gender discrimination. This may derive from the Christian vision of the human person closely bound to the incarnation of the divine. It could also depend on their greater association with the Western feminist culture. Furthermore, their greater opposition to religious discrimination may depend on their own experience of belonging to a minority religion and feeling degraded as foreign, despite the religion’s probable presence in South India since the first century and its flourishing communities in the region from the fourth century.

Curiously, this challenging area of religio-cultural diversity and discrimination was not discussed in the questions posed to the respondents in the empirical study “Synodal Way—Global Church Perspectives.” Perhaps the German synodal process does not consider this as a crucial challenge in its local context. However, given the massive rate of migration of people to Western countries, particularly of the young (

Anthony 2015), intercultural–theological discernment on this issue would be relevant in the macro phase of the synodal process, involving continental representatives of the global Church.

4.2. Partecipatio Inter Gentes ad Intra et ad Extra

The second objective—promoting greater participation—is founded on the priestly, prophetic and governing/diaconal functions not only of ordained members, but of all the baptized. Synodality, as an exercise in participation, is intended to breathe life into church structures (

ITC 2018, n. 46–48), encouraging co-creativity, co-participation and co-responsibility, by sharing power in terms of service (

Brighenti 2022) and harmonizing the roles of the people of God, priests, bishops and the successor to Peter. Viewing synodality from the perspective of the laity,

Pope Francis (

2015) describes an inverted pyramid in his discussion of altering the dominant role of the hierarchy. This also implies the conversion of the papacy, in recognition of the centrality of the laity (

Pope Francis 2013, n. 32). The key questions are: What should the laity be? And what are they, in fact? (

Vélez 2022). It is not sufficient to recognize that all the faithful are anointed by the Spirit; it is indispensable to listen to their voices. In other words, the laity must participate in the processes of discernment, decision-making, planning and implementation (

John Paul II 1988, n. 51). Obviously, religious women and men, with their respective charisms, also have special contributions to make in this regard. This implies a recognition of the primacy of

sensus fidei, exercised as the

sensus fidelium of the totality of the baptized, including of the poor and the marginalized (

Pope Francis 2013, n. 119, 198;

Vélez 2022, p. 52). The Asian synodal process—as summarized below—brought into focus the identities and roles of priests, religious, the laity and, specifically, women, with a view to supporting participation and transformational leadership (

Noceti 2022b, pp. 186, 190–93, 205–7).

4.2.1. Participation of Priests and Religious

Ministerial priests are expected to inspire baptismal priests, namely, the laity, to become full, active and conscious participants in the Church’s governance and liturgical celebrations (

PCBC 2022, p. 50). Instead, priests and religious tend to be preoccupied with the administration of institutions and fail to engage in meaningful encounters and dialogues. There have been cases of priests becoming overly secular, dependent on vices, engaged in business, owning vast properties, and misusing parish funds. In other words, some priests have been involved in monetary, verbal and sexual abuses (

CCBI 2022, p. 42;

CBCP 2022, pp. 59, 62;

CBCK 2022, p. 34;

FABC 2023, n. 63, 93–94). Unhealthy relationships between the clergy and the faithful, discriminatory approaches and poor leadership have had a negative impact on Christian communities. The authoritarian leadership and patriarchal attitudes of the clergy and the blind obedience and naive reliance on their opinions on the part of the laity have led to the problem of clericalism (

CBCM 2022, p. 28;

CBCK 2022, p. 34;

FABC 2023, n. 90–92, 112–15).

On the one hand, there is a sharp decline in the vocation of the priesthood and religious life, and on the other, there is a lack of adequate formation courses and programs for the clergy, religious, the laity and Basic Christian/Ecclesial Communities to deepen their specific identities, synodal leadership and synodal spirituality (

CCBI 2022, p. 43;

CBCJ 2022, p. 23;

CBCMSB 2022, p. 14;

CBCK 2022, p. 43;

CBCM 2022, p. 28;

CRBC 2022, p. 16;

FABC 2023, n. 166–68, 190). In the Indian context, it was suggested that religious women and the lay faithful could be appointed in major and minor seminaries as formators, members, spiritual guides, counsellors and professors (

CCBI 2022, p. 48). In the Myanmar Church, it was felt that the situations of those who have distanced themselves from the Church, like ex-seminarians and former priests and religious, could be reconsidered in the current ecclesial context (

CBCM 2022, p. 22).

4.2.2. Participation of Laity and Youth

The history of the Church in Korea and Japan illustrates the crucial role played by the laity in introducing, preserving and sharing the Christian faith for hundreds of years (

Quevedo 2022). As in other communities, the laity participates in ministries of lectorship and acolyteship in a spontaneous manner in Bangladesh, without being officially instituted (

CBCB 2022, p. 11). Nonetheless, currently, greater attention—according to the Church in Laos—needs to be paid to the formation of ordinary Christians and community leaders for the transmission of faith in the family (

CELAC 2022, p. 58). In the Indian context, it was suggested that parish communities should make space for the expertise of the faithful, including men, women and, in particular, youths, by creating inventories of the human resources available in these communities (

CCBI 2022, p. 48). Although youths form a significant part of the Asian population (about 65%), they are largely absent from the life of the Church. Instead, youths who frequent the Church stand in need of adequate faith formation and must be included in leadership positions and decision-making processes (

FABC 2023, n. 98, 137–38). Given that contemporary youths are technologically literate, there is a need for greater investment in media and communication, to involve them in the ecclesial sphere and to educate them in the critical use of social media (

FABC 2023, n. 102, 139).

Christians taking up responsibilities for the society and the nation, namely, involving themselves in social, political and community services as administrators, create awareness—as in Indonesia—that these are integral parts of the mission of the Church (

KWI 2022, p. 8). This means that the professionals among the faithful are to be engaged when the Church seeks to address social issues (

CBCK 2022, p. 40). Unfortunately, it was noted that there is little dialogue about social and political issues between priests and the laity, as in the context of the Philippines (

CBCP 2022, p. 65).

4.2.3. Participation of Women

In both the social and the ecclesial spheres, women are often marginalized as homemakers, domestic workers and working women (

PCBC 2022, p. 40). It is felt that greater space needs to be made for women in ministries (

CBCMSB 2022, pp. 7, 17;

FABC 2023, n. 95–97). Religious women, in particular, feel left out of the decision-making process within the Church (

CCBI 2022, p. 41;

FABC 2023, n. 65–66).

The empirical study “Synodal Way—Global Church Perspectives” (

Cerda-Planas 2023) suggested that Asians manifested strong agreement (mean 4.46)—second only to African respondents—with the important roles women play in their communities. However, they manifested only positive ambivalence (mean 3.16) regarding women’s influence on communities and parishes. They manifested some agreement with the possibility of admitting women to the ministries in the Church (mean 3.51).

In relation to this issue, diverse opinions were expressed during the focus-group conversation. On the one hand, the Asian participants recognized that women’s work is mainly related to the domestic sphere of ecclesiastical life and that they are not involved in decision-making processes. For some of them, however, this was not a major setback. Nonetheless, they were of the view that women should be empowered to play a more appropriate role in the community. In this vein, other participants held that it is possible for women to become leaders within the Church and that this should be an area for improvement. Since women have been recognized and integrated into leadership positions in different societal spheres, it should not be a problem for this to take place within the Church. However, there are transversal reservations regarding the ordination of women.

4.2.4. Transformational and Servant Leadership

Underlying the participation of priests, the laity, youths, and women in ecclesial life, there is the question of leadership, implying a certain degree of power. Both within the Church and in society, power needs to be decentralized and made collaborative, encouraging communal discernment and decision-making, with a transformational and empowering model of “servant” leadership (

CBCMSB 2022, pp. 16–17;

CBCP 2022, p. 73;

FABC 2023, n. 86–87, 164). In the resolution of conflicts, there is a need for greater involvement from traditional leaders, religious leaders and government officials. While the lay leadership is particularly evident in small communities, building cooperation and dialogue with religious leaders is indispensable for overcoming the politicization of religious issues and promoting religious moderation in society. The presence of traditional cultural values like respect for and obedience to elders/leaders can help lay people to play leadership roles (

Quevedo 2022;

CCBI 2022, pp. 47, 49;

CBCT 2022, pp. 31, 33;

KWI 2022, pp. 10, 15).

The empirical study “Synodal Way—Global Church Perspectives” (

Cerda-Planas 2023) found that compared to those from other regions, the Asian (and Latin American) respondents manifested weak ambivalent agreement (mean 3.17) regarding the notion that power and influence are exclusively in the hands of priests and bishops, but their highest level of agreement (mean 4.36)—as in the case of the Middle Eastern respondents—was over the importance of laypeople’s influence in the Church and of improvements in the distribution of power in the Church. Comparatively, in the multireligious context, Christianity seems to be undermined by hierarchies (priests and bishops), depending excessively on foreign or Western ecclesial power centers.

In this vein, the Asian participants in the focus group suggested that power within the Church should be the subject of further discussion, although they considered that it is better to conceptualize it as responsibility, since this is a more appropriate term in the ecclesial context. In effect, while power and rights are discussed in the political and civil sectors, Asian religions generally focus more on responsibility. The focus-group participants tended to agree that, generally, priests and bishops assume exclusive decision-making and power positions and that this could eventually be modified in the future. However, in order for this to occur, it is necessary that the laity are prepared to assume tasks for which they are not currently qualified. Furthermore, the participants emphasized that there are no better or worse ecclesial roles; the dignity of all ecclesial roles is the same. In their view, currently, hierarchies are present in different areas of life—such as education or social life—and it is therefore not odd that they also exist in the Church.

Our empirical–theological research project “Spirituality, Education and Leadership” (

Anthony and Hermans 2020;

Hermans and Anthony 2020) focused on the transformational leadership qualities of the leaders of Higher Secondary Catholic schools run by Salesians in India. The findings—based on 198 respondents (from principals/headmasters, vice principals/assistant headmasters, and key coordinating teachers) to an online questionnaire—revealed that the heads of Salesian schools are characterized by a fairly strong involvement in transformational leadership, comprising idealized attributes and behaviors, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individual consideration, in addition to associated rewards. The emerging factor with all hypothesized dimensions reveals an integral understanding of transformational leadership among the heads of schools. The strong impact of discernment on transformational leadership was expected. However, it is significant that, among the spiritual determinants, discernment emerged as one of the two strongest predictors. In effect, discernment is the compass for navigating good life with and for others over the high sea of spirituality. In other words, discernment is the core of lived spirituality, with which human beings learn to sense the emergence of the good life with and for others and to act and speak accordingly. They report higher levels of discernment if they report a stronger spiritual character trait of self-directed-cooperativeness, more spiritual capital (both in claiming the absolute truth of their own religion and/or in claiming that truth emerges from religious pluralism) and a higher level of mystical experiences.

The above views on the role and formation of priests and the laity could easily reflect the proposals emerging from other local churches with regard to the promotion of ecclesial participation. Although the Asian churches favor the empowerment of women in their ecclesial roles, with the possibility of admitting women to some ministries in the Church, they have reservations regarding the ordination of women. This could be an important theme for intercultural theological discernment at the macro phase of the synodal process. It is noteworthy that, as announced in L’Osservatore Romano (26 April 2023), the 70 participants (men and women, including youths), comprising priests, deacons, religious and the laity from local churches participating in the General Assembly of the synodal event in Rome, will have the right to vote on the proposals discussed.

4.3. Missio Inter Gentes ad Intra et ad Extra

If communion is the basis of synodal process, the goal of lived synodality is to discern and promote the mission of evangelization (

ITC 2018, n. 53). Historically the Church has been used to

missio ad gentes, with Western missionaries leaving for other parts of the non-Christian world. Given the uniqueness of the culture and identity of indigenous people, their symbols and images,

missio ad gentes, i.e., the proclamation of good news to the non-Christian population, called for adaptation, accommodation and, finally, inculturation. With the emergence of Christianity in the southern hemisphere since the Second Vatican Council, missionaries from these churches leave for other parts of the world, including the increasingly secularized European continent. Along with the more theologically positive comprehension of various cultures and religions, this situation emphasizes the urgency of

missio inter gentes, particularly in the Asian continent (

Tan 2004;

Anthony 2012a,

2012b,

2013), as well as the necessity of a decolonized planetary theology, working towards a new world order (

Balasuriya 1984). In effect, the synodal process entails the exploration of diverse religio-cultural visions and values, along with their integration in the ecclesial praxis of

communio,

partecipatio et missio inter gentes. We summarize the synodal debate on the mission of evangelization in the multicultural, multireligious and poverty-stricken Asian context in terms of intercultural, ecumenical, interreligious and humanizing dialogue. The synodal process, recognizing the working of the Spirit in ways known only to God among the peoples of Asia, their history and their socio-cultural realities (

John Paul II 1999, n. 15), should lead to

ad intra ecclesial transformation, i.e., a legitimate plurality of forms of expression of Christian identity, as well as to

ad extra societal transformation, i.e., to a public theology addressing the common good and a common home (

ITC 2018, n. 117–19).

4.3.1. Mission of Evangelization and Witness

Christianity’s image as a foreign import results from the fact that Asian churches are the outcomes of

ad gentes missionary activities originating in Europe. The missionary enterprise was at its height during the colonial and imperialistic expansion of Western powers in several Asian countries, including Myanmar (

CBCM 2022, p. 37). Ecclesial power is in fact viewed as based on the imperial colonial past, with its hidden superiority complex. Evangelization in the Asian context therefore requires a decolonized perspective, a decolonial theologization. Since Christians are, at times, ashamed or afraid to declare themselves as members of the Church on account of frequent abusive comments and discrimination in education, employment, etc., as well as their treatment as second-class citizens, they tend to hide their identity and pretend to be Buddhists or followers of other religious traditions, such as in Laos (

CELAC 2022, pp. 52–53).

The credible proclamation of the Gospel springs from the real-life experiences of individual Catholics and communities (

CBCT 2022, p. 35). In effect, the lived faith of believers in their respective contexts is already a proclamation of good news. This requires the adequate formation of lay people as evangelizers (

CCBI 2022, pp. 42, 48). Families, which are domestic churches, as well as parish communities and Catholic educational institutions can serve as

loci of evangelization among people of different faiths, cultures and economic statuses (

CBCT 2022, p. 29). As the education, healthcare and social development offered by Catholic institutions are appreciated by members of other faiths, these qualified services can serve as witnesses to our faith (

CCBI 2022, p. 44).

In the empirical study “Synodal Way—Global Church Perspectives” (

Cerda-Planas 2023), we found that compared to those from other regions, the Asian (and African) respondents’ strongest point of agreement was the view that “shared participation by lay and clergy in the mission of Church helps in proclaiming the message” (mean 4.59). This tendency probably results from the lived experience of Christians amidst other religious traditions, which are essentially popular religions, i.e., people consider them as their own, with priests called into temple service. There are no territorial divisions headed by priests. It is left to individuals or families to choose to attend one or another temple or sect.

Comparatively, the Asian participants agreed more strongly than the others with the notion that “mandatory celibacy for diocesan priests helps the Church in its credibility and in spreading its message” (mean 3.73). As mentioned above, in the Asian context, the celibacy of monks and priests is viewed as a witness to their total dedication to the divine and to the experience of liberation/salvation. This explains the value of celibacy for spreading good news, which is also a call to follow the master closely as his disciples, chaste, obedient and poor. In the final stage of the synodal process at the macro level, the Asian respondents’ view in favor of celibacy in association with its witness value, could be taken up in an intercultural discussion and discernment.

With a view to deepening the discussion, it is opportune to refer to an empirical-theological research project, “Believing and Communicating” (

Anthony 2016b), on the urgency of evangelization, undertaken among international students frequenting Pontifical universities in Rome. A total of 567 students responded to the online questionnaire. It is interesting that the urgency of evangelization manifested itself as a continuum starting from broader missionary–ecumenical–pastoral concentric circles. However, the students who responded to the questionnaire tended to feel a greater urgency to evangelize the non-practicing Christians, those who did not belong to any religious tradition, and practicing members of the Church. They manifested a moderate sense of urgency regarding the evangelization of those who belong to other religious traditions (which implies interreligious dialogue) and those who belong to other Christian churches (which requires ecumenical dialogue). This means the demonstration of greater respect in evangelizing those who already have a defined religious identity; however, the relative lack of urgency in these cases can also be explained by a certain lack of interest in or inability to propose the Gospel message in a dialogical way. In the current multidenominational and multireligious context, greater clarity regarding evangelization from the ecumenical and interreligious perspectives could contribute to an increase in zeal among evangelizers, with evangelization understood as a process in which the missionary–ecumenical–pastoral dimensions are intertwined in a continuum, reinforcing the dialogical perspective.

The results of the research also revealed some useful clues concerning theological paradigms. First, in the constants of lived theology, we can distinguish the conservative–static paradigm from the progressive–dynamic alternative. The conservative–static paradigm is characterized by a perennial theology, focused on the ontological dimension and displaying little sensitivity to the value of modern sciences and cultural and religious pluralism. Instead, the progressive–dynamic paradigm represents a theology that develops over time towards the full understanding of truth, embracing the value of modern sciences, cultures and other religions. The correlational analysis, in turn, showed that the missionary–ecumenical–pastoral urgency felt by those who responded was strongly associated, on the one hand, with the conservative–static paradigm, that is, ecclesiocentrism, individual eschatology and religious monism and, on the other, with the progressive–dynamic paradigm, that is, integral Christology (the integration of Christology from above and below), optimistic anthropology, cultural pluralism and extroverted mysticism. This means that the urgency to evangelize can be sustained by both the conservative–static and the progressive–dynamic paradigms. The regression analysis, however, revealed that the predictability of the feeling of the urgency of evangelization is linked to the affirmation of cultural pluralism and integral Christology, as well as to the attenuation of anthropological pessimism. Therefore, in order to strengthen evangelical zeal, greater clarity in terms of the figure of Christ, the value of culture and the dignity of the human person is indispensable. Furthermore, in the post-conciliar context, the link between missionary–ecumenical–pastoral urgency and the conservative–static paradigm, comprising ecclesiocentrism, individual eschatology and religious monism, becomes ambiguous and problematic if it is not critically reviewed from the dialogic–communion perspective.

4.3.2. Mission of Inculturation and Interculturation

Various languages and cultural groups in Asia represent different ways of perceiving the world, the Church and human reality (

CBCMSB 2022, p. 3). Overcoming the dichotomy between cultural identities and Christian life poses the challenge of inculturation. The latter also involves challenging the cultural elements that dehumanize people (

CBCM 2022, p. 30). A lack of proper inculturation can lead to unacceptable levels of religious syncretism (

CET 2022, p. 41).

Although they are already lived out to some extent, more space must be made for vernacular languages, cultural musical instruments, regional music, local styles of liturgical vestments, etc. The challenge in the Asian context is that of the integration and inclusion of many cultures in the liturgy in an intercultural perspective (

CBCM 2022, p. 27;

CCBI 2022, p. 43;

FABC 2023, n. 117–18). In other words, inculturation in the local cultural context is a necessary condition to initiate mutual enrichment or interculturation between churches. Such cultural differences can be lived as opportunities for unity in diversity. In effect, ethnic Christian communities have their own diverse lifestyles, customs, cultures and languages, and they can coexist peacefully and work for the common good (

CBCT 2022, p. 39;

FABC 2023, n. 120–21).

Furthermore, a dialogue with God’s creation—according to the Thai and Laos churches—can be ensured by incorporating valuable local cultural elements into local liturgies to make the celebration meaningful: forest rituals, the blessing of rice fields, watersheds, fish, the custom of

basi—the watering of the statues of saints during the New Year—and offering food during liturgies, etc. (

CBCT 2022, p. 30;

CELAC 2022, pp. 52–53, 59). However, the practice of faith in connection with local cultural traditions is not always feasible, as in the case of customary weddings, the celebration of the Lao New Year, which often falls during Holy Week, etc. Evangelization can be undertaken—as in the Cambodian context—through Khmer Art (Yeeke, Ba-Sak, Lakhon Khol and other performances) in local languages (

CELAC 2022, pp. 60, 66).

By contrast, foreign priests, who pose linguistic and cultural barriers, become, to some extent, obstacles to building up local communities. This means that parish priests who are foreign nationals need proficiency in the local language and familiarity with the local culture. Without these factors, the local people become indifferent to faith, turn to other religions, or practice two religions, indulging in superstitious beliefs or divination (

CELAC 2022, pp. 48–50;

CRBC 2022, p. 17). Moreover, insufficient pastoral care paves the way for other religious fundamentalists to proselytize the Catholic faithful easily, on account of their poverty and ignorance (

CBCM 2022, p. 34). For these reasons, addressing the ethnic cultures of Christians through trained catechists is a growing need (

CBCT 2022, p. 30).

To delve deeper into this topic, we refer to our empirical–theological research on “Ecclesial praxis of inculturation” (

Anthony 1997,

1999b), undertaken among 990 Catholic higher-secondary students and 390 Catholic teachers in Tamil Nadu, India. Firstly, the findings clarified that in a holistic approach, culture must be viewed in connection with its religious and/or ideological core and, consequently, that inculturation is inseparably bound to the processes of interreligious dialogue and liberation. Secondly, inculturation is a question of the relation between ecclesial faith and societal culture, specifically the forging of a dialogical, diacritical and dialectical relationship between the two poles. Thirdly, the dynamic process of inculturation is guided and oriented by the internal regulative mechanism generated by the corrective and complementary roles of the two points of convergence: salvation/liberation and

anubhava (God–experience). Finally, on the subjective plane, these relationships are to be realized in the cognitive, affective and operative components of attitude/praxis, since inculturation is essentially a question of subjects’ agency and lifestyle. In and through the subjective components of praxis, native Christians become the agent-subjects of inculturation. The inculturizing praxis of agent-subjects, in turn, depends on their predisposition towards this praxis, i.e., on their inculturizing attitude, as well as on the external contextual factors that determine both attitude and praxis.

Because the Christian faith has, through the centuries, saturated the Western cultural context, it may appear that inculturation is a necessity only for the churches of the southern hemisphere. Instead, as was made clear by the Asian synodal discussion and related empirical research, the churches in the Western world need to take up the challenge of inculturation in the context of secular culture and enrich themselves interculturally with the developments in the younger churches in the synodal process.

4.3.3. Mission of Ecumenical and Interreligious Dialogue

As small minorities, living and operating within multicultural and multireligious societies, Christians in Myanmar, China and the rest of Asia face the challenge of ecumenical and interreligious dialogue. Christians have a special responsibility to develop new forms of living together with their brothers and sisters from other religious traditions. In this endeavor, divisions within Christianity are obstacles to giving a credible witness to the Gospel. In fact, denominationally divided missionary enterprise cause further divisions (

CBCM 2022, pp. 33, 37;

CECAC 2022, p. 29;

CRBC 2022, pp. 18–19;

FABC 2023, n. 75–77). However, local churches do not seem prepared for dialogue with other Christian denominations and religions, such as Islam, Confucianism, Hinduism, and Buddhism (

KWI 2022, p. 11;

CBCK 2022, pp. 38–39;

CET 2022, p. 48). Living in villages with different religious denominations—as in the context of Laos—can be both a challenge and an opportunity for Catholics to bear witness to their faith. As the faith of many Christians is still impregnated with Buddhist or superstitious practices, this can help or hinder the evangelization of local traditions and cultural practices, such as participating in Buddhist feast days, offering food to monks for transmitting merits to the dead, and seeking auspicious days for weddings or building houses (

CELAC 2022, pp. 54, 57).

The push for Islamization and policies restricting religious freedom in some parts of Asia, like Malaysia, can make the young vulnerable to the temptations of interfaith conversion (

CBCMSB 2022, pp. 7, 8). As a minority community in an Islamic country, Christians face the challenge of forced conversion, the misuse of blasphemy laws, forced and underage marriages, discrimination in workplaces and in education, inaccurate census data, attacks on Churches and Christian colonies, mob/suicide attacks, bomb blasts, etc. Faced with these situations, Christian communities live under a state of fear and face new forms of “martyrdom” (

FABC 2023, n. 61–62, 109–11, 130). These threats and the lack of adequate pastoral care force the faithful either to join other denominations or to convert to other religions (

PCBC 2022, pp. 44, 48). Religious fundamentalism, fanaticism and anti-conversion laws seriously sully the attempts to develop dialogue in countries like India and Japan. Moreover, the allegedly foreign character of Christianity hinders its dialogue with civil society (

CCBI 2022, p. 45;

CBCJ 2022, p. 22;

FABC 2023, n. 146).

Although intra/interfaith harmony is promoted in terms of participation in festivals, devotions, praying with non-believers, civic movements and ecological initiatives (

PCBC 2022, p. 42;

CCBI 2022, p, 44;

CBCJ 2022, p. 23), it is feared that such interactions with other religions can easily swallow up Christians if they are not formed well (

CBCT 2022, p. 38). For this reason, the formation of the young needs to be based on church teachings on interfaith relationships and to advocate community development for the underprivileged (

CBCMSB 2022, p. 8). In this vein, a need is felt for the ongoing exposure of non-Christian faculty and staff members, as well as the students and patrons of Christian institutions, to the Gospel message and its values (

CBCJ 2022, p. 25). An example of a positive experience in this regard is the encounter between Catholic and Buddhist monks and lay Cambodian Buddhists to “create a new culture.” Although these groups differ in terms of religious affiliations, there is a conviction that all can contribute to the common good (

CELAC 2022, p. 64). Similarly, as a dialogue on life, there are also positive experiences of joining other denominations to celebrate some feasts like Christmas Day, Elder’s day, International Human Rights Day and the network for environmental conservation (

CBCT 2022, p. 32;

CCBI 2022, pp. 44–45;

SMC 2022, pp. 59, 67)

Our cross-religious comparative research project, “Religion and Conflict Attribution” (

Anthony et al. 2014), focusing on the interpretation of religious plurality, religiosity, mystical experience, religiocentrism and religious conflict, was undertaken among Christian, Muslim and Hindu college students in Tamil Nadu, India, with 1920 respondents. Instead of presenting specific details of this complex research, we focus on the key aspect of interpreting religious plurality, on which the research produced three reliable cross-religious comparative models: monism (combining replacement monism and fulfilment monism), commonality pluralism (acknowledging the underlying common ground) and differential pluralism (acknowledging the value and richness of differences). The model that proved to be most acceptable to the three religious groups was commonality pluralism, with Hindus differing significantly from the other two. The Hindus seemed to be the most open to the underlying commonality of religions. Differential pluralism received ambivalent responses from the three groups, with no significant differences between them. The model that was contested by the three religious groups was monism. The Christians ambivalently tended towards agreement with this point of view, whereas the Muslims agreed with monism. The Hindus, by contrast, disagreed with the monistic interpretation and differed significantly from the other two groups. The Hindu students were found to be the least exclusive and the most open to the commonality underlying the other religions. Since the Second Vatican Council, the Christian community seems to have been in the process of overcoming the traditional monistic–exclusive approach to other religions.

Insofar as the traditionally Christian Western world is becoming multireligious through the migration of people from other continents and through Western Christians adopting other religious traditions, the experiences of the churches in the Asian continent can be helpful in synodal discernment.

4.3.4. Mission of Liberation and Humanization

Evangelization requires that the Church engage in dialogue with the poor and their unjust and oppressive situation, promote justice, protect human rights, prevent human trafficking and care for creation. In other words, we need to humanize society at large by addressing human-rights issues associated with freedom of religion, socioeconomic rights, civil rights, the right to life, environmental rights, etc. (

CBCK 2022, pp. 32, 37;

CBCT 2022, pp. 26, 29–31;

CECAC 2022, p. 30;

CRBC 2022, p. 18;

FABC 2023, n. 70, 151). This means that the Church should be willing to work with civil society, the political establishment, the cultural realm and the business world (

CET 2022, p. 47;

CECAC 2022, p. 29). More concretely, the Church should facilitate dialogue on political issues such as election fraud, vote buying, cultural bias and stereotyping (

CBCP 2022, p. 66). The ecological crisis, in turn, also invites dialogues over nature and culture for the protection of ecosystems; it calls for creative conversations about our common home, i.e., how we live, learn and work in dialogue with nature (

CBCM 2022, p. 33;

CBCK 2022, p. 45;

FABC 2023, n. 133–34, 178–79).

There is a growing conviction that the lay faithful require adequate formation to be able to participate in public life, engage in dialogue with civil authorities and collaborate with the state on matters of common concern: catering to the marginalized, immigrants, unemployed, street children, refugees, displaced people, etc. (

CCBI 2022, pp. 45–46;

CBCJ 2022, p. 18;

CRBC 2022, pp. 13–14;

FABC 2023, n. 103–7, 151). In other words, the laity should be empowered and encouraged to involve themselves in the existential conditions of the stigmatized and marginalized in society:

Orang Asal and

Asli (indigenous populations),

Dalits, LGBTQIA+ people, drug addicts, gangsters, etc. (

CBCMSB 2022, p. 3;

CBCP 2022, pp. 61, 66;

PCBC 2022, p. 50;

CBCT 2022, p. 31;

CET 2022, p. 42;

CCBI 2022, p. 43;

FABC 2023, n. 67–69, 108, 148, 169).

In the empirical study, “Synodal Way—Global Church Perspectives” (

Cerda-Planas 2023), we found that, unlike the respondents from the African region, who manifest clear disagreement, the Asian respondents showed a rather high level of acceptance concerning the new assessment of homosexuality (mean 3.80). In the Asian context, this may depend on the general pragmatic socio-religious approach to the phenomenon. The references to homosexuality in religious mythology might also make it more tolerable. However, in the focus group, the participants mentioned that homosexuality is culturally rejected in several Asian countries, and therefore, they did not see the need for any modifications to Church’s stand in this matter.

An International Empirical Research Project, “Religion and Human Rights,” was undertaken in over 20 countries in Europe, Asia, Africa and Latin America. In the context of Tamil Nadu, India, 1215 Christian, Muslim and Hindu college students participated as respondents. With a view to examining the human-rights attitudes of the young, the questionnaire included scales on the right to life (

Anthony and Sterkens 2019a), civil rights (

Anthony and Sterkens 2016), judicial rights (

Anthony and Sterkens 2019b), political rights (

Anthony and Sterkens 2018), socioeconomic rights (

Anthony and Sterkens 2020) and the separation of religion from the state (

Anthony 2023). The findings revealed that among all the categories of human rights, socioeconomic rights and the right-to-life issue of abortion, for psycho-economic reasons emerged, as distinct categories in the perception of the young (

Anthony and Sterkens 2021). The young respondents manifested a clear tendency towards agreement on socioeconomic rights, with the Christians expressing significantly stronger agreement than the Muslims and Hindus. The three religious groups affirmed that they might engage in human-rights activism if necessary. The findings emerging in the overall project in the Indian context suggest that the Christian, Muslim and Hindu religious traditions can offer a meta-ethical basis for critically upholding socioeconomic and other rights. This is in line with the fact that religions, with their beliefs, experiences and practices, aspire to contribute to human flourishing, liberation and salvation.