Abstract

The ancient city of Jericho, located at the archaeological site of Tell es-Sultan west of the Jordan River and adjacent to the Ein es-Sultan spring on the edge of modern Jericho, has often been associated with the biblical city of Jericho and the story found in the book of Joshua. The identification of Jericho with Tell es-Sultan is not disputed, and numerous excavation teams have affirmed Tell es-Sultan as Jericho. While excavations have also uncovered the fiery destruction of a walled city at Jericho, the date of the fall of Bronze Age Jericho and the association of this destruction with the narrative in the book of Joshua have been a point of disagreement among archaeologists for more than a century. The first excavations at Jericho (Tell es-Sultan) occurred in 1868 under the direction of Charles Warren, followed by soundings conducted by FJ Bliss in 1894, the expeditions of the years 1907–1909 and 1911 by Ernst Sellin and Carl Watzinger, the excavations of 1930–1936 directed by John Garstang, the 1952–1958 project of Kathleen Kenyon, brief excavations by Shimon Riklin in 1992, and the most recent excavations and restorations by the joint Italian–Palestinian team from 1997 to 2000 under Nicolo Marchetti and Lorenzo Nigro, followed by the 2009–2017 seasons directed by Jehad Yasin, Hamdan Taha, and Lorenzo Nigro. Although there is a significant deviation in views over the exact date of the destruction and abandonment, archaeological analyses of Jericho generally agree on the manner in which the city met its end, including a widespread fire, collapsed mudbrick walls, burning of the stored grain, and abandonment. However, assessing all of the archaeological data from Jericho IVc, both new and old, including pottery wares, Egyptian scarabs, a cuneiform tablet, stratigraphic analysis, and radiocarbon samples, allows a more definitive historical reconstruction concerning the chronology of the destruction of Jericho and its connections to the biblical narratives.

1. Introduction

The ancient city of Jericho, located at the archaeological site of Tell es-Sultan, about 5 miles west of the Jordan River, adjacent to the Ein es-Sultan spring on the northwest edge of modern Jericho, has often been associated with the biblical city of Jericho and the story of its destruction as found in the book of Joshua. The identification of Jericho with Tell es-Sultan is not disputed, and the name of the city may even be attested on a Middle Bronze Age scarab discovered in Tomb D641 at Jericho, rendered as “Ruha” and perhaps deriving from an early Semitic word “Yareah” for the moon, connected to the name of the moon deity. Numerous excavation teams and archaeological investigations have not only identified Tell es-Sultan with Jericho but additionally uncovered the fiery destruction of a walled city. Yet, the date of the fall of the Bronze Age city of Jericho and the association of this destruction with the narrative in the book of Joshua have been points of disagreement among archaeologists for more than a century. The first excavations at Jericho (Tell es-Sultan) occurred in 1868 under the direction of Charles Warren, followed by soundings conducted by FJ Bliss in 1894, the expeditions of the years 1907–1909 and 1911 by Ernst Sellin and Carl Watzinger, the excavations of 1930–1936 directed by John Garstang, the 1952–1958 project of Kathleen Kenyon, brief excavations by Shimon Riklin in 1992, and the most recent excavations and restorations by the joint Italian–Palestinian team from 1997 to 2000 under Nicolo Marchetti and Lorenzo Nigro, followed by the 2009–2017 seasons directed by Jehad Yasin, Hamdan Taha, and Lorenzo Nigro. These excavation projects used varying methods, excavated for differing amounts of time per season, and all came to unique conclusions regarding the details of the fall of the final Bronze Age city at Jericho. Although there has been a disparity of views regarding the interpretation of the data, including the exact date of the destruction and abandonment, archaeological analyses of Jericho generally agree on other specifics, such as the manner in which the city met its end.

The current, prevailing view amongst modern archaeologists regarding Jericho is that the narrative in the book of Joshua about the destruction of the walled city is a “romantic mirage,” which contradicts the archaeological findings, and that “there was no trace of a settlement” around 1230 BC, “the suggested date of the conquest” (Finkelstein and Silberman 2002, pp. 76, 81–82; Joshua 6: 1–26).1 This perspective is widely held in academia and asserts that the Jericho conquest is a later literary invention and mythical propaganda devoid of historical information, or at best a legendary historical core that might preserve loosely similar earlier events combined with reflections of later periods (Finkelstein and Silberman 2002, pp. 107, 118; Dever 2003, pp. 51–74; Na’aman 1994, pp. 280–81; Fritz 1987, p. 84; Killebrew 2005, p. 152; Finkelstein and Mazar 2007, pp. 61–62; Lemche 1985, p. 56; Thompson 1987; Van Seters 2001). However, many other scholars have argued that the conquest of Jericho was a historical event that archaeological data supports (e.g., Albright 1957, pp. 273–89; Bright 1981, pp. 129–43; Garstang [1931] 1978; Wood 1999, pp. 35–42; Younger 2009, pp. 237–41). Within this “historical” view are two main subdivisions: that the fall of Jericho occurred about 1230 BC in Late Bronze IIB or that the destruction happened around 1400 BC at the end of Late Bronze IB. Although the vast majority of scholars over the last few decades have placed the hypothetical conquest of Jericho in the 13th century BC, and that is primarily the view mentioned and summarily rejected by most modern scholars, the conclusions of Kenyon following her excavations at Jericho asserted that neither ca. 1230 BC nor ca. 1400 BC would be possible for the fall of Jericho, since allegedly the last Bronze Age city existed during the Middle Bronze Age in the 16th century BC, not anytime in the Late Bronze Age, and therefore the story contradicts archaeological findings at the site (Kenyon 1957, pp. 213–18, 257–58; 1967; 1970; 1975, pp. 562–64).2 The debate between a conquest of Jericho in the 13th century BC versus around 1400 BC has been extensively discussed elsewhere and in relation to the Exodus and conquest generally, but it is almost universally acknowledged by archaeologists that there is no trace of the destruction of Jericho in the 13th century BC or an inhabited and walled city of Jericho at that time (Finkelstein and Silberman 2002, p. 76; Wood 2005, pp. 475–89; 2007, pp. 249–58; Hoffmeier 2007, pp. 225–47).3 However, the dispute at Jericho revolves around archaeological data related to the date of the fall of Jericho city IV, the final Bronze Age city, and how closely the specifics of the Joshua narrative about the fallen walls, fire destruction, looting, timing, and subsequent abandonment and settlement match the findings at the site.

Archaeological excavations have shown that Jericho had a long history of occupation, but the city is first mentioned in the Bible during the period of the wilderness wandering (Numbers 22: 1). According to biblical descriptions of Canaanite cities, including Jericho, many of these settlements prior to the Joshua period conquest had walls, gates, and various fortifications (Numbers 13: 19–28; Deuteronomy 3: 5; Joshua 2: 5, 6: 1–5, 10: 20). Past evaluations of Canaan in the Late Bronze II and the 13th century BC, where some scholars have placed the conquest of Canaan, suggest that there was a dearth of fortified cities in the region. However, massive fortifications originally constructed in the Middle Bronze Age often continued to be used at least into the first part of the Late Bronze Age, and in some cases even later (Mazar 1992, p. 243). Subsequent archaeological excavations and surveys have demonstrated that specific cities mentioned in the conquest narratives were occupied and fortifications were even present in the 15th century BC, or Late Bronze I (Hansen 2000; Kennedy 2013).

2. The Middle Bronze Age Wall at Jericho

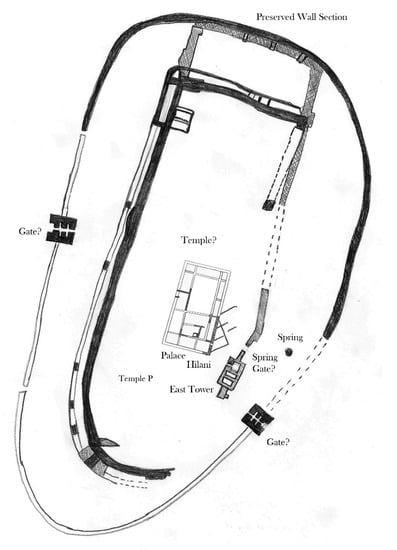

Jericho is one of the many settlements in Canaan where a formidable fortification system was constructed during the Middle Bronze Age. During this period, the people of Jericho built a cyclopean wall around the city, which utilized a stone retaining wall and an upper wall of mudbrick. This city wall was rebuilt in Middle Bronze III around 1600 BC and encompassed an area of about 17 acres, although part of the site was destroyed in modern times due to road construction, so calculations are only approximate (Nigro and Taha 2009, pp. 731–34; Marchetti et al. 1998, p. 141). According to the early German excavations, when less damage had been done to the site, the stone retaining wall was approximately 4 to 5 m high, and the upper mudbrick wall on top of the retaining wall was approximately 6 to 8 m high and 2 m thick (Sellin and Watzinger [1913] 1973, p. 58; Marchetti et al. 1998, p. 141). Inside this was another wall, made of mudbrick, which, according to the Italian–Palestinian team, reached a height of 12.11 m above ground level outside of the fortifications (Marchetti et al. 1998, p. 142). Both a stone retaining wall and a rampart of debris piled on the MB I and MB II fortifications were built in MB III, or approximately 1650–1550 BC/1600-1500 BC (Marchetti et al. 1998, pp. 131, 138, 141; Marchetti 2003, pp. 311–12; Nigro and Taha 2009, p. 731; Nigro 2020, p. 201). Besides the ceramic typology indicating the date of the construction in Middle Bronze III, excavations have demonstrated that the Cyclopean Wall cuts through Tower A1, which was in use during Middle Bronze I and II (Nigro and Taha 2009, p. 734). A report about the 1952 excavations had come to similar conclusions, stating that the latest surviving defenses are Middle Bronze Age and that this system had been preceded by two previous Middle Bronze Age walls built prior (Tushingham 1952, pp. 8–10). Although these final city walls appear to have been constructed in Middle Bronze III, this does not mean that Jericho had no walls in the subsequent Late Bronze I period. Rather, as was the case at many other sites in Canaan, the massive fortifications could have remained in use into the Late Bronze Age or beyond. One of the clearest parallels for this comes from Hazor, where it was obvious that the city of the Late Bronze Age reused Middle Bronze fortifications and repaired or strengthened them, and this was perhaps also the case at Jericho (Yadin 1959, pp. 9–19; 1975, pp. 266–67; 1982, p. 22). Other sites, such as Gezer and Tell Jerishe, demonstrate the continued use of the Middle Bronze Age fortification system into the Late Bronze Age (Dever 1992, p. 17; Sukenik 1942, p. 199). It is therefore possible that the city wall built at Jericho in Middle Bronze III continued to be used into the subsequent period of Late Bronze Age I. However, whether or not the city was occupied in Late Bronze I can only be determined by an analysis of other data. (See Figure 1 below).

Figure 1.

Composite map of the ancient city of Jericho based on multiple excavations.

3. Destruction of Jericho IVc

Temporarily setting aside the question of Middle Bronze III versus Late Bronze I for the fall of Jericho IVc, while acknowledging the possibility that the Middle Bronze Age fortifications could have continued in use into the Late Bronze Age, the correlation between the manner of destruction found in excavations at Jericho and the Joshua narrative about the conquest of Jericho should be examined. The book of Joshua records that not long after the spring harvest, the Israelites besieged Jericho, the walls of the city fell, the army walked up into the city, a restriction had been placed to not loot Jericho except for metals, and finally the city was burned (Joshua 3: 15, 4: 19, 5: 10, 6: 1–24). Additional information related to stratigraphy indicates that a city may not have been rebuilt at Jericho subsequent to its destruction until the 9th century BC, except for a briefly used residential building by Eglon of Moab during the Judges period (Joshua 6: 26; Judges 3: 12–30; 1 Kings 16: 34). Therefore, after the fall of Jericho, there should have been no city at the site until the Iron Age II and only a residence during the Late Bronze II.

According to archaeological excavations at Jericho, including the Kenyon and Italian–Palestinian excavations, the mudbrick wall on top of the stone retaining wall had collapsed and fallen in front of the retaining wall around most of the city and had essentially formed a pile of sloping bricks resembling a ramp (Marchetti et al. 1998, p. 143; Kenyon and Holland 1981, p. 110; Wood 1990b, pp. 54–56; 1999, p. 37). The outward falling of the city walls, which was followed by a massive fire that engulfed Jericho and included the collapse of buildings in the city, was proposed by excavators as possibly being the result of an earthquake rather than a battering ram or other siege equipment (Garstang 1948, pp. 118, 138–139, 159; Kenyon 1957, pp. 179, 262; Kenyon and Holland 1981, pp. 110, 370).4 This “terrible destruction” of Jericho by fire has been posited by various excavators and other researchers as the result of a violent attack by either a foreign enemy or another city-state, without agreement regarding the identity of the attackers (Nigro 2016, p. 15; 2020, p. 201). The falling or collapse of the wall was the first phase, while the destruction by fire was the second phase. The collapse of the city wall, which was constructed in the Middle Bronze Age III, and other associated architecture in the final Bronze Age City IVc Jericho is dated on the basis of its construction period. The finds sealed by the destruction layer on top of collapsed architecture and subsequently constructed architecture such as the “Middle Building” mean the falling of this wall, building collapse, and the destruction of the city must have occurred within the periods of either Middle Bronze III or Late Bronze I.

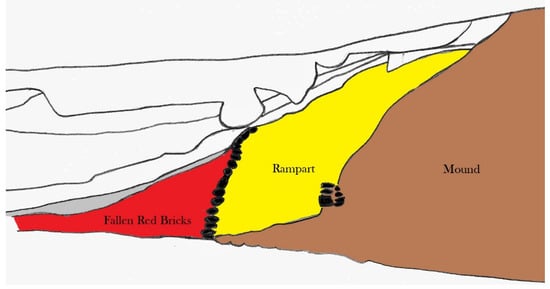

Although Kenyon separated the falling of the walls and the following fire destruction into separate phases, the two events need not be separated by vast amounts of time, and there is no indication that the city was abandoned or lay dormant in between the collapse and the fire. Perhaps it is more than a coincidence that the sequence is the same as that recorded in the book of Joshua—fallen city walls, then the intentional burning of the city by the attacking Israelites (Joshua 6: 20–24). Because battering rams would cause the walls to fall into the city at specific points of attack rather than outside and in front of the retaining wall all around nearly the entire city, this facet of the destruction has often been attributed to an earthquake, although other explanations may be possible. Indeed, rather than displaying the characteristics of a battering ram siege and forcing entry at a particular weak point or points of the city defenses, as would be expected from conventional warfare, an earthquake or another action with similar result might have caused wall sections to crumble both outside and inside the line of the stone retaining wall. However, perhaps more important than the specific cause of the collapse is that, according to archaeological observations, the walls of Jericho City IVc fell down the slope, resulting in the formation of a simple ramp up into the city. This phenomenon of a fallen mudbrick wall forming a pile that people could use to march over and past the walls and into the city accords with the description in the Joshua narrative about the wall falling upon itself and the army then walking up into Jericho (Joshua 6: 20). (See Figure 2 and Figure 3 below).

Figure 2.

Cross section of Trench I showing the Jericho outer city wall built in Middle Bronze III. The pile of fallen mudbricks in the form of a ramp in front of the stone retaining wall originally comprised a mudbrick wall atop the stone retaining wall.

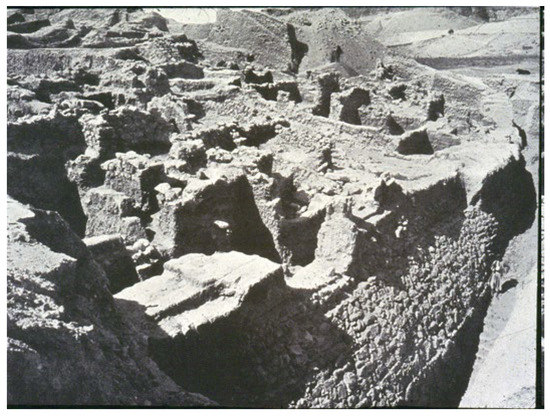

Figure 3.

Houses of mudbrick built up against the outer wall at Jericho. Photo from the Sellin and Watzinger excavations.

After the walls fell, the next archaeologically observable event in the sequence was the burning of the city. The fire destruction of Jericho IVc was found in numerous excavation areas at the site, and it was a severe and complete destruction, including blackened walls and floors, fallen bricks and timber, burnt debris, collapsed roofs, and burned remains around the MBIII wall (Kenyon and Holland 1981, p. 370; Nigro and Taha 2009, p. 735). The fire was so intense and so widespread, including residential houses, the palace and the temple, that it appeared to indicate a deliberate burning of Jericho rather than an accidental or localized fire restricted to a particular building or section of the city (Garstang 1948, pp. 118, 136, 142). This is further supported by the long abandonment of the site, with the next architecture dating to Iron II except for the briefly occupied “Middle Building,” indicating that significant death and destruction that occurred at Jericho. (Marchetti 2003, p. 317). This violent destruction brought an end to the stratum known as Jericho IVc (Jericho 1997–2000 Seasons Report: http://www.lasapienzatojericho.it/Results%201997-2000/res_sulIVc.htm, accessed on 22 February 2023). (See Figure 4 below).

Figure 4.

Stratigraphic section of the final Bronze Age destruction layer at Jericho from a Kenyon excavated square on the eastern side of the city, showing collapsed building materials, pottery, charcoal, and ash.

However, the collapse of the walls and the city being engulfed in a destructive fire were not the only details found at Jericho that match the Joshua narrative. Prior to attacking the city, the Israelites had observed Passover (March/April), and then the Israelite army had been instructed to loot only the metals from Jericho but to leave everything else in the city to be destroyed (Joshua 5: 10, 6: 19–20). Excavations in the destruction layer at Jericho uncovered numerous ceramic storage jars containing significant amounts of grain, specifically barley, that had been burned along with the buildings rather than looted (Kenyon 1957, pp. 230, 261; Garstang 1931, pp. 193–94; 1948, p. 141). These finds indicate an attack on Jericho soon after barley harvest time in March/April and by an army that was not concerned with looting the food supplies of the city, matching the timing and methodology of the invading Israelite army in the Joshua narrative (Joshua 2: 6, 3: 15, 5: 10; cf. Gezer Calendar; Exodus 9: 31–32; Ruth 1: 22; 2 Samuel 21: 9). Although this would explain why there was so much burned grain found in the city at the time of its destruction, it also directly contradicts the typical military practice of the period, as the full grain jars indicate that the city was conquered while food stores were still abundant and the attacking army neglected to loot food from the city. Campaigns were usually launched before the spring harvest, when the city under siege would have the lowest amount of resources, and sieges were usually quite long, such as the 3-year siege of Sharuhen and the 7-month siege of Megiddo (Pritchard 1969, p. 246; Cline 2002, p. 21). Besieging a city in the spring season prior to harvest would not only starve out the defenders but also allow the attacking army to harvest and use the grain in the fields outside of the city for an additional food source (Lichtheim 1976, p. 34). At Jericho IVc, the attack was initiated after harvest, the siege was brief, and the invaders simply burned the food supplies inside the city. (See Figure 5 below).

Figure 5.

Burned storage jars full of grain uncovered in the fire destruction layer of Jericho IVc. Found and photographed in the excavations under Garstang.

4. Pottery and the Date of Destruction

Although there may be general agreement about the basic manner in which Jericho IVc was destroyed and perhaps even acknowledgement that the events and sequence appear consistent with the Joshua narrative, there is much dispute concerning the exact date when the city was destroyed and if those events could connect to the fall of Jericho recorded in the book of Joshua. In order to establish a firm date for the destruction of Jericho, it is necessary to analyze the chronology of the ceramic remains, royal scarabs found at the site, a clay tablet discovered in excavations, and the various radiocarbon dates.

Ceramic remains are the most abundant material found from excavations in this region, and the chronology of pottery typology is widely used for establishing the date of excavated strata. At Jericho, thousands of sherds were excavated in association with the destruction layer and the final Bronze Age city, including local wares, imported wares, and locally produced exotic imitation wares. The types of pottery that are most distinctive are usually decorated wares, and excavations at Jericho have certainly uncovered much of this material.

Cypriot Bichrome Ware, with its characteristic painted red/brown and blue/black decoration along with fine clay, is one type of pottery that can indicate the occupation of the site in Late Bronze I or ca. 1500–1400 BC (Gitin 2019, pp. 339–41; Amiran 1970, pp. 152–57). Garstang excavated various bichrome fragments in the destruction layer of the final Bronze Age city (Wood 1990b, pp. 37, 53; 1990a, pp. 48, 49; Bienkowski 1986, pp. 128–30; Garstang 1934, pls. 29: 4, 7, 12; 34: 3; 36: 12; 39: 5; p. 111, pl. 34: 10; and pl. 31: 8). Chocolate on White Ware, which is another painted ware that was found in significant amounts at Jericho from numerous excavations, maybe even more indicative of Late Bronze I occupation around 1500–1400 BC (Fischer 1999, pp. 1–22; Gitin 2019, pp. 169–70; Amiran 1970, pp. 158–60). Another possible indicator of the fall of Jericho and its abandonment prior to Late Bronze II could be the lack of Western Anatolian Gray Ware imports, which appear in the Levant beginning in Late Bronze IIA (Gitin 2019, p. 381).

Although Kenyon argued for dating the destruction of Jericho IVc to around 1550 BC rather than slightly later in the 15th century BC due to an alleged absence of exotic wares such as Cypriot Bichrome and Chocolate on White, the excavation reports on Jericho tell a different story. Both Cypriot bichrome and Chocolate on White can be seen on plates and descriptions in the Kenyon expedition reports, which were published posthumously, demonstrating that this type of pottery was in fact discovered (Kenyon and Holland 1983, pp. 436, 464–72). This exotic ware characteristic of Late Bronze I was also found in the Sellin and Watzinger excavations and can be seen in the excavation report of 1913, although ceramic chronology was not well understood and defined at that time (Sellin and Watzinger [1913] 1973, pp. 123–29, 142–46). However, Watzinger eventually argued that Jericho was unoccupied during Late Bronze I (Watzinger 1926, pp. 131–36). The Kenyon expedition did in many places mention the presence of Late Bronze pottery, even noting parallels to Late Bronze IB strata at other sites such as Megiddo Level VIII and Beth-Shean stratum IX (Kenyon 1951, p. 133; Tushingham 1953, p. 63). The excavations under Kenyon surely found Late Bronze I pottery, which is consistent with the findings from other expeditions at Jericho. However, because the Kenyon excavations focused on deep trenches rather than broad trenches, only a sampling of findings from each period was uncovered rather than extensive material culture from a single period. While using narrow excavation trenches encompassing only very small areas of the site may have been a pragmatic method to probe and discover an overall stratigraphic profile of the site, this technique also had major shortcomings for understanding any one occupational period at Jericho (Herr 2002, p. 53; Wood 1990a, p. 47).

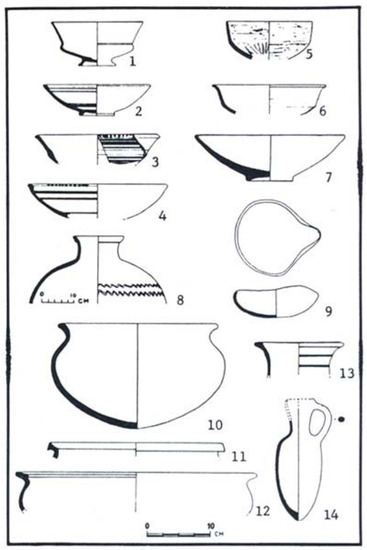

The excavations at Jericho led by Garstang, which dealt extensively with Middle Bronze Age and Late Bronze Age structures, tombs, and materials, found considerable amounts of Late Bronze Age pottery, including local and imported wares. Among the distinctive Late Bronze I pottery types were Cypriot wares and imitations, but a lack of Mycenaean wares indicated that occupation of the city had ceased by Late Bronze II (Garstang 1941, pp. 369–71). However, the local wares excavated at Jericho were the most prolific of the pottery finds. It is therefore significant that these local wares have clear parallels to Late Bronze I strata at other sites in Canaan. Wood analyzed the local wares in detail and explained numerous parallels, refuting the idea that these local wares could all belong to Middle Bronze II or III (Bienkowski 1990, p. 46; Wood 1990a, pp. 45–49, 68–69). Among the numerous forms found at Jericho with clear parallels from other sites were “the flaring carinated bowl with slight crimp” from Late Bronze I contexts at the Lachish Fosse Temple 1 (Tufnell et al. 1940, pl. 42: 129), Megiddo IX (Loud 1948, pl. 53: 19), Hazor 2 (Yadin 1961, pl. 263: 3–16), Hazor cistern 9024 level 3 (Yadin et al. 1958, pl. 123: 1–9), and Hazor cistern 7021 level C (Yadin 1972, pl. 136: 1–7; Wood 1990a, pp. 47–48). Conical bowls with painted interior concentric circles, a typical Late Bronze IB form found all over the southern Levant, were also found at Jericho (Garstang 1934, p. 121). Parallels in Late Bronze I contexts come from Ashdod XVII (Dothan 1971, p. 81), Hazor 2 (Yadin 1960, p. 94; 1972), Lachish Fosse Temple 1 (Tufnell et al. 1940, pl. 37: 1), Shechem XIV (Toombs and Wright 1963, fig. 23: 2), Mevorakh XI (Stern 1984, fig. 5: 7) and Megiddo VIII (Loud 1948, pl. 61: 18). Another bowl form found at Jericho has Late Bronze I strata parallels from Rabud LB4 (Kochavi 1974, fig. 4: 3) and Shechem XIV (Toombs and Wright 1963, fig. 23: 1) (number 5), Lachish Fosse Temple 1 (Tufnell et al. 1940, pls. 41: 98, 104, 105, pls. 42: 127) (number 6), and Lachish Fosse Temple 1 (Tufnell et al. 1940, pls. 37: 3, 4, 7 and 38: 32, 33), Mevorakh XI (Stern 1984, fig. 5: 11–14), Megiddo VIII (Loud 1948, pl. 61: 13, 14) and Hazor 2 (Yadin 1961, pl. 288: 3) (number 7), although this has also been found in Middle Bronze III contexts and is probably a form that continued from MB into LB (Wood 1990a, p. 48). The storage jar type found at Jericho (number 8) is another typical Late Bronze I form, with parallels from Late Bronze I strata such as Lachish Fosse Temple 1 (Tufnell et al. 1940, pl. 57: 389), Rabud LB4 (Kochavi 1974, fig. 4: 10), Shechem XIV (Toombs and Wright 1963, fig. 23: 14) and Hazor cistern 7021, level C (Yadin 1972, pl. 141: 2). Oil lamps, which continuously changed over time and are quite distinctive by archaeological period, are another indicator from Jericho that the city was occupied during Late Bronze I, as the saucer form with a slightly pinched spout (number 9) is typical of Late Bronze I with a clear parallel from Lachish Fosse Temple 1 (Tufnell et al. 1940, pl. 45 186, 187). Cooking pots were prolific due to their common use and short lifespan, and they are another pottery type that is quite distinctive by period. At Jericho, the everted rim cooking pots with a round bottom (numbers 10, 11, 12) have numerous parallels in other Late Bronze I contexts, such as Lachish Fosse Temple I (Tufnell et al. 1940, pl. 355: 361), Shechem XIV (Toombs and Wright 1963, fig. 23: 19, 20), Michal XVI (Herzog et al. 1989, fig. 5.6: 3), Mevorakh XI (Stern 1984, fig. 7: 9), Hazor 2 (Yadin 1972, pl. 138: 4), Lachish Fosse Temple 1 (Tufnell et al. 1940, pl. 55: 354), Rabud LB4 (Kochavi 1974, fig. 4: 6), Ashdod XVII (Dothan 1971, fig. 33: 7), Michal XVI (Herzog et al. 1989, fig. 5.6: 8), Hazor XV/2 (Yadin 1961, pls. 199: 19 and 289: 7), and Hazor 2 (Yadin 1972, pl. 139: 1–4). The water jar with painted stripes (number 13) was unique to the Late Bronze Age, and the type found at Jericho is also known from Late Bronze I strata at Ashdod XVII (Dothan 1971, fig. 33: 13), Hazor 2 (Yadin 1961, pl. 266: 15), and Hazor cistern 7021 level C (Yadin 1972, pl. 141: 12). The dipper juglet from Jericho (number 14), while occurring from Middle Bronze III to Late Bronze II, also appears to have a form consistent with Late Bronze I at the Lachish Fosse Temple 1 (Tufnell et al. 1940, pl. 52: 297, 303). The most recent excavations at Jericho have also affirmed Late Bronze IB pottery at the site from a building in the palace area near the center of the city (Nigro 2009, p. 362).

While the idea that Jericho was completely unoccupied during the Late Bronze Age is not accepted by archaeologists, a variety of ideas about the extent of the settlement and the dates of occupation have been proposed, ranging from only occupation at the “Middle Building” in the 14th century BC to a small settlement that allegedly lasted into the beginning of LB IIB before being abandoned until the Iron Age IIA (Nigro 2020, pp. 201–6). These discrepancies are mostly due to differing chronologies about 18th Dynasty Pharaohs, incorrectly placing LB I pottery into LB II (e.g., Chocolate on White Ware), and claiming that the evidence for the LB II settlement disappeared due to erosion, dumping, or leveling. While erosion can move archaeological material or cover it, pits and dumping can jumble the chronology of sections of strata, and leveling can cover or damage architectural remains, the evidence for entire strata does not simply disappear from archaeological sites and is not a phenomenon observed elsewhere in the region. The ceramic data from excavations at Jericho since 1907 indicate that the site was indeed inhabited during the Late Bronze I. (See Figure 6 and Figure 7 below).

Figure 6.

Cypriot Bichrome sherds excavated by Garstang at Jericho IV and shown in (Wood 1990b).

Figure 7.

Pottery types from Jericho shown in Wood 1990a, p. 47. 1. flaring carinated bowl (Jericho 4, fig. 110: 1); 2 4. bowls decorated with internal concentric circles (Jericho 5, fig. 206: 2; Jericho 4, fig. 110: 8 and Jericho 5, fig. 206: 1); 5–7. bowls (Jericho 5, fig. 191: 16, Jericho 4, fig. 109: 34 and Jericho 5, fig. 189: 2); 8. storage jar (Jericho 5, fig. 199: 6); 9. lamp (Jericho 5, fig. 197: 2); 1012. cooking pots (Jericho 5, fig. 198: 10; Jericho 4, figs. 150: 22 and 121: 11); 13. decorated water jar (Jericho 5, fig. 206: 11); 14. dipper juglet (Jericho 5, fig. 196: 5).

5. Scarabs, Stratigraphy, and Radiocarbon Tests

While the ceramic data from Jericho indicates the occupation of city IV into Late Bronze I and, by extension, the destruction of this final city during Late Bronze I, the evidence from inscribed scarabs is an important secondary form of chronological information that can help pinpoint an accurate date for the fall of Jericho. During the course of excavations at Jericho, numerous scarabs have been discovered, some of which are stylistic and others that contain the names of rulers. For the purposes of unraveling the dispute about the date of the fall of Jericho, a series of Egyptian scarabs inscribed with the names of kings from the 13th Dynasty to the middle of the 18th Dynasty (18th to 14th centuries BC) are especially useful. The most important of these royal scarabs were those of the 18th Dynasty Pharaohs Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, and Amenhotep III (Garstang 1948, p. 126). The scarabs of Thutmose III, one of the most powerful and prestigious Pharaohs, are one of the few of Pharaohs whose scarabs may have been manufactured after his death or even handed down as an heirloom. In contrast, the scarab of Hatshepsut is a very unusual find, as Pharaoh–Queen Hatshepsut suffered damnatio memoriae after her reign in an attempt to wipe her name and image from history, and her scarabs would not have been reproduced or circulated later (Gardiner 1964, pp. 182, 198). Another artifact of note is a two-sided seal, not a scarab, of Thutmose III (Garstang 1948, p. 126). This seal, unlike the scarabs of Thutmose III, is a rare artifact and one that can be restricted to the years of his reign in the early to middle 15th century BC. The scarabs of Amenhotep III, a rather isolationist and insignificant Pharaoh, were also not reproduced after his reign nor held in high regard, so the idea that all of these scarabs were heirlooms or reproductions from centuries later is implausible. However, many scarabs of Amenhotep III have been found in stratified LB IB contexts from Canaan. The presence of scarabs of Hatshepsut and Amenhotep III at Jericho, after which no more Pharaohs are attested at Jericho, indicates that the occupation of the site ceased during the reign of Amenhotep III and at the end of Late Bronze IB around 1400 BC. Recent studies and discussion of 18th Dynasty chronology may have a slight bearing on the exact date of these connections, but would not change overall conclusions (e.g., Ramsey et al. 2010). Indications of Egyptian weakness in Canaan and the inability or refusal to send troops to help combat the invading “Habiru” in the region during the reign of Amenhotep III as described in the Amarna Letters should also be considered as related to the fall of Jericho during this period (cf. Johnson 1996, pp. 65–82; Moran 1992). The chronology from the inscribed royal scarabs, in agreement with data from pottery excavated at Jericho, therefore seems to indicate that the destruction of the final Bronze Age city of Jericho occurred during the reign of Amenhotep III at the end of the Late Bronze IB and near 1400 BC (Garstang 1948, pp. 135, 179; cf. Garstang 1944, p. 380). Indeed, even the most recent expedition at Jericho acknowledges the possibility that the city could have been destroyed in Late Bronze IB in the second half of the 15th century BC, although it attributes the attack to the Egyptians led by Thutmose III (Nigro 2020, p. 201). While it is possible that Thutmose III could have conducted a military campaign against Jericho, the city appears nowhere in Egyptian annals or topographic lists around this period, and the method of destruction and looting does not fit the typical military practice of the Egyptians. (See Figure 8 below).

Figure 8.

Seal of Thutmose III (left) and the scarab of Amenhotep III (right) excavated at Jericho. Amemhotep III was the latest Pharaoh attested at Jericho and corresponds to the LBIb pottery.

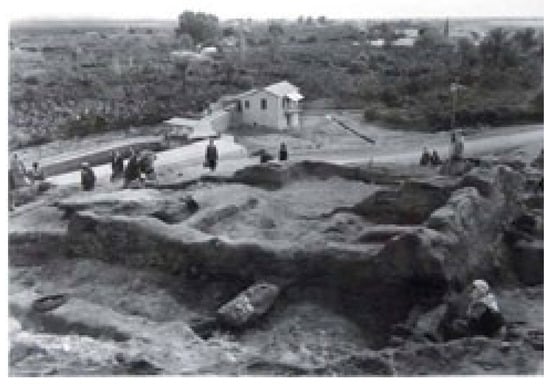

In addition to the ceramic and scarab data indicating destruction of Jericho in Late Bronze IB ca. 1400 BC, the abandonment and reoccupation of the site in the following periods also suggests that the overall narrative about Jericho in the books of Joshua, Judges, and Kings spans Late Bronze IB to Iron IIA. Following the destruction of the city, although the city itself remained abandoned until Iron IIA, a lone residential structure on the site was later built and occupied in Late Bronze IIA during the 14th century BC, at what came to be designated the “Middle Building” due to its stratigraphic positioning beneath the Hilani and above the Palace storerooms of Areas H-I 6 (Bienkowski 1986, pp. 112–21; Garstang 1941, pp. 369–70; 1948, p. 180; Kenyon 1957, p. 261). After the destruction of Jericho IVc, the final Bronze Age city, Jericho was vacant for a number of years. Dirt, pottery, and other material washed down from the higher areas of the mound and was called the “streak” or the “wash” (Wood 1990a, p. 49). When the Middle Building in Area H on the east side of the tell was built, this layer of wash was underneath its foundations. After the Middle Building was abandoned, along with the rest of the site, erosion again formed a wash layer over the stratum of the Middle Building. Because of this, the Late Bronze IIA material of the Middle Building was both above and below some Late Bronze I material (Wood 1990a, p. 49; Garstang 1934, pp. 106, 111; Bienkowski 1986, p. 112; Kenyon 1951, pp. 120–21). In the Iron Age, the Hilani structure was built over the Middle Building, but after its abandonment, erosion from the top of the mound again washed down and covered the stratum of the Hilani. Thus, material from the top of the mound, especially from the final Bronze Age city, is found in various strata because of erosion. However, the most important stratigraphic relationship to note is that the Late Bronze IIA Middle Building was constructed over the stratum of Jericho IVc (except where the “wash” brought materials from Jericho IV), and thus there is an indication of a short period of an occupational hiatus in between the two layers. This means that the last phase of Jericho City IVc precedes Late Bronze IIA, but not for a long period of time. The “Middle Building” is also significant because it can be linked to another phase in the history of Jericho, which is recorded in connection to Eglon of Moab and an event that occurs decades after the destruction of Jericho by Joshua (Judges 3: 13–26).5 This Middle Building was identified as a large residence or villa associated with Eglon of Moab in the 14th century BC, measuring about 14.5 m by 12 m and being the sole occupied area at the previously destroyed city (Garstang 1948, pp. 177–80). (See Figure 9 below).

Figure 9.

The “Middle Building” at Jericho, excavated and photographed by Garstang and dated to the Late Bronze IIA or the 14th century BC.

Another significant find associated with the Middle Building was a cuneiform clay tablet dated to the 15th century BC on the basis of epigraphy (van der Toorn 2000, p. 98; Bienkowski 1986, p. 113; Garstang 1934, pp. 116–17). Tablets in the Bronze Age southern Levant are rare, with very few examples coming from any city south of Ugarit. From Hazor, Tell el-Hesi, Taanach, Shechem, Jerusalem, Megiddo, and elsewhere in Canaan, only about 40 total tablets or tablet fragments from the Late Bronze Age have been discovered (e.g., Horowitz et al. 2002, pp. 753–66). Unfortunately, the Jericho tablet found in the Middle Building was in extremely poor condition, with few signs visible, and no plausible reading for the text has yet been determined. Although this tablet was found in excavations of the Middle Building, it was dated to the 15th century BC and may have been part of the “wash” material from the previous stratum, further indicating occupation at Jericho in Late Bronze I and the 15th century BC. (See Figure 10 below).

Figure 10.

Damaged cuneiform tablet from Jericho dated to the 15th century BC.

After the abandonment of the Middle Building, the city of Jericho was not rebuilt until the Iron Age II, including the reuse of the MB III-LB I cyclopean wall and the construction of the Hilani building (Nigro 2020, pp. 204–6). During the 9th century BC reign of Ahab in Iron Age II, a small settlement was built over part of the ruins of Jericho, including tripartite pillared buildings associated with Israelite architecture. While slightly later, according to the biblical narrative, the city was also apparently occupied in the time of Elisha by “sons of the prophets,” and LMLK (“for the king”) imprinted jar handles likely dating to the reign of Hezekiah was also found at the site (1 Kings 16: 34; 2 Kings 2: 4–18).

Radiocarbon samples from Jericho have also been an important subject of discussion, but unfortunately, the radiocarbon dates from the Jericho IV destruction have been inconsistent and therefore have not yet been able to support a particular date for the fall of the city. Initial radiocarbon samples taken from Jericho were eventually analyzed by the laboratory at the British Museum, and a date was published as 1410 BC +/− 40 (Kenyon and Holland 1983, p. 763). However, due to a problem with equipment calibration that affected many samples for the years 1980–1984 and caused uncertainty of the results, BM-1790 from Jericho was revised to 3300 +/− 110 BP (Bowman et al. 1990, p. 74).6 Another analysis of 18 samples from the Kenyon excavations at Jericho yielded results ranging from 3393 +/− 17 BP (GrN-18368) to 3312 +/− 14 BP (GrN-18539), with an outlier of 3614 +/− 20 (GrN-18538) that may have been from an older and reused wooden beam; the calibrated probable dates given during the time of the study were 1601-1566 calBC or 1561-1524 calBC (Bruins and van der Plicht 1995, pp. 213–20). Using OxCal with IntCal20 and no adjustments for geographical location, these samples would yield calibrated dates ranging from 1699 to 1623 calBC 70.3% probability (GrN-18368) to 1617–1531 calBC 95.4% probability (GrN-18539), with the outlier (GrN-18538) 2031–1899 calBC 95.4% probability (https://c14.arch.ox.ac.uk/calibration.html, accessed 20 April 2023; cf. Christopher Bronk Ramsey 2009, pp. 337–60). These samples from the Kenyon excavations indicate that their calibrated radiocarbon dates are significantly higher than the historical dates when compared to the proposed dates of destruction published by the various excavation teams. In 2000, the Italian–Palestinian expedition tested two samples that were excavated from a building that appeared to contain debris from the final destruction of the Bronze Age city that had washed down to the bottom of the mound. These two most recent samples yielded calibrated dates of 1347 BC +/−85 and 1597 BC +/−91, which could accommodate either proposed approximate historical destruction dates of around 1550 BC or 1400 BC if the calibration curves were accurate (Marchetti and Nigro 2000, pp. 206–7, 330, 332). However, it is a known issue that the radiocarbon dates for Bronze Age sites in the Levant often conflict with the chronological information derived from ceramics and inscriptions and that some samples can be from burned wooden beams cut from trees that were harvested over 100 years before their destruction (Mazar and Ramsey 2008, pp. 159–80; Levy and Higham 2005; Ben-Tor and Rubiato 1999, p. 36). Thus, radiocarbon dates should be viewed with caution, and dating strata by means of pottery typology continues to be the primary and most reliable method employed by archaeologists. While a few radiocarbon samples from Jericho do fit a Late Bronze IB destruction of the city around 1400 BC, others match more closely to a 1600–1500 BC destruction timeframe. Essentially, the radiocarbon dates from Jericho at present appear to only rule out a ca. 1230 BC destruction hypothesis but have not been able to solve the dispute between a Middle Bronze III or Late Bronze I destruction of the city.

6. Conclusions

When all of the chronological data from Jericho IV is assessed and assembled, including specific pottery wares and forms of Late Bronze I, 18th Dynasty Egyptian scarabs concluding with Amenhotep III, a cuneiform tablet dated tentatively to the 15th century BC, and radiocarbon samples that would at least allow the possibility of a destruction around the Late Bronze IB period, the destruction of the final walled Bronze Age city of Jericho appears to have occurred near the end of the Late Bronze I period around 1400 BC. The mudbrick wall falling upon itself all around the city, similar to an earthquake rather than a specific point of entry, an apparently intentional fire that consumed the entire city, the many storage jars of grain that were not looted, and the timing of the attack soon after the spring harvest all agree with the specifics of the Joshua account regarding the methods of destruction. An abandonment of Jericho following its destruction until Iron IIA, except for a palatial residence briefly occupied in Late Bronze IIA, also matches the narratives and sequences in the books of Joshua, Judges, and Kings. Thus, archaeological excavations and analysis at Jericho appear to place the destruction of the final Bronze Age city ca. 1400 BC in a manner consistent with the account in the book of Joshua.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The conquest of Canaan, the Holy Land, is also mentioned in the Quran (Surah 5 Al-Ma′ida, 20–26), although the city of Jericho is not specified. |

| 2 | The view of Kenyon that Jericho was destroyed around 1550 BC was based primarily on the expulsion of the Hyksos and the alleged lack of Cypriot pottery of the Late Bronze Age discovered in the Jericho excavations. Note that Watzinger thought that Jericho was destroyed by 1600 BC or even earlier in an evaluation of his excavations (cf. Watzinger 1926). |

| 3 | The view that the conquest of Canaan occurred during the 13th century BC or around approximately 1230 BC was promoted by Albright and prompted by his excavation findings of destruction at Tell Beit Mirsim which he dated to the 13th century BC and connected to the conquest of Canaan. |

| 4 | While there was also an Early Bronze Age II earthquake dated to around 2700 BC at Jericho which provides an example of such phenomenon, and many significant earthquakes throughout history are known to have occurred in the Jericho region, the events should not be conflated (Nigro 2020, p. 188). |

| 5 | The place where Eglon of Moab resided can be identified as Jericho by comparing the information in Judges 3: 13 with that of Deuteronomy 34: 3 and 2 Chronicles 28: 15, which both record that Jericho is the city of palm trees. |

| 6 | BP or “Before Present” and referring to the year 1950. |

References

- Albright, William. 1957. From the Stone Age to Christianity. Garden City: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Amiran, Ruth. 1970. Ancient Pottery of the Holy Land. Rutgers: Rutgers Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Tor, Amnon, and Maria Teresa Rubiato. 1999. Excavating Hazor, Part Two: Did the Israelites Destroy the Canaanite City? Biblical Archaeology Review 25: 22–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bienkowski, Piotr. 1986. Jericho in the Late Bronze Age. Warminster and Wiltshire: Aris & Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Bienkowski, Piotr. 1990. Jericho Was Destroyed in the Middle Bronze Age, Not the Late Bronze Age. Biblical Archaeology Review 16: 45–49, 68–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, Sheridan G. E., Janet C. Ambers, and MNnbsp Leese. 1990. Re-Evaluation of British Museum Radiocarbon Dates Issued between 1980 and 1984. Radiocarbon 32: 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bright, John. 1981. A History of Israel. Philadelphia: Westminster. [Google Scholar]

- Bruins, H. Bruins, and Johannes van der Plicht. 1995. Tell es-Sultan (Jericho): Radiocarbon Results of Short-Lived Cereal and Multiyear Charcoal Samples from the End of the Middle Bronze Age. Radiocarbon 37: 213–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cline, Eric H. 2002. The Battles of Armageddon: Megiddo and the Jezreel Valley from the Bronze Age to the Nuclear Age. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dever, William G. 1992. The Chronology of Syria-Palestine in the Second Millennium B.C.E.: A Review of Current Issues. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 288: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dever, William G. 2003. Who Were the Israelites and Where Did They Come From? Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Dothan, Moshe. 1971. Ashdod 2–3: The Second and Third Seasons of Excavations, 1963, 1965, Soundings in 1967. Atiqot English Series; Jerusalem: Dept. of Antiquities and Museums, vols. 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, Israel, and Amihai Mazar. 2007. The Quest for the Historical Israel. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, Israel, and Neil Asher Silberman. 2002. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Ancient Texts. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Peter. 1999. Chocolate-on-White Ware: Typology, Chronology, and Provenance: The Evidence from Tell Abu al-Kharaz, Jordan Valley. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 313: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, Volkmar. 1987. Conquest or Settlement? The Early Iron Age in Palestine. The Biblical Archaeologist 50: 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, Alan H. 1964. Egypt of the Pharaohs. Oxford: National Geographic. [Google Scholar]

- Garstang, John. 1931. The Walls of Jericho. The Marston-Melchett Expedition of 1931. Palestine Exploration Quarterly 63: 186–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garstang, John. 1934. Jericho: City and Necropolis, Fourth Report. University of Liverpool Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology 21: 99–136. [Google Scholar]

- Garstang, John. 1941. The Story of Jericho: Further Light on the Biblical Narrative. The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures 58: 368–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garstang, John. 1944. History in the Bible. American Journal of Economics and Sociology 3: 371–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garstang, John. 1948. The Story of Jericho. London: Marshall, Morgan & Scott. [Google Scholar]

- Garstang, John. 1978. Joshua-Judges. Grand Rapids: Kregel. First published 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Gitin, Seymour, ed. 2019. The Ancient Pottery of Israel and Its Neighbors from the Middle Bronze Age through the Late Bronze Age. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, David G. 2000. Evidence for Fortifications at Late Bronze I and II: A Locations in Palestine. Ph.D. dissertation, Trinity College and Theological Seminary, Newburgh, Indiana. [Google Scholar]

- Herr, Larry G. 2002. W.F. Albright and the History of Pottery in Palestine. Near Eastern Archaeology 65: 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, Ze’ev, George Rapp, Jr., and Ora Negbi, eds. 1989. Excavations at Tel Michal, Israel (Michal). Publ. of Tel Aviv University Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology No. 8. Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmeier, James K. 2007. What Is the Biblical Date for the Exodus? A Response to Bryant Wood. Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 50: 225–47. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, Wayne, Takayoshi Oshima, and Seth Sanders. 2002. A Bibliographical List of Cuneiform Inscriptions from Canaan, Palestine/Philistia, and the Land of Israel. Journal of the American Oriental Society 122: 753–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W. Raymond. 1996. Amenhotep III and Amarna: Some New Considerations. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 82: 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, Titus. 2013. A Demographic Analysis of Late Bronze Age Canaan: Ancient Population Estimates and Insights through Archaeology. Uitenhage: University of South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon, Kathleen. 1951. Some Notes on the History of Jericho in the Second Millennium. B.C. Palestine Exploration Quarterly 83: 101–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyon, Kathleen. 1957. Digging Up Jericho. New York: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon, Kathleen. 1967. Jericho. In Archaeology and Old Testament Study. Edited by D. Winton Thomas. Oxford: Clarendon. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon, Kathleen. 1970. Archaeology in the Holy Land, 3rd ed. London: Nelson. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon, Kathleen. 1975. Jericho. In Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Edited by Michael Avi-Yonah and Ephraim Stern. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, vol. 2, pp. 550–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon, Kathleen, and Thomas A. Holland. 1981. Excavations at Jericho III: The Architecture and Stratigraphy of the Tell. Jerusalem: British School of Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon, Kathleen, and Thomas A. Holland. 1983. Excavations at Jericho V. The Pottery Phases of the Tell and Other Finds. Jerusalem: British School of Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Killebrew, Ann. 2005. Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. [Google Scholar]

- Kochavi, Moshe. 1974. Khirbet Rabud Debir. Tel Aviv 1: 2–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemche, Niels Peter. 1985. Early Israel: Anthropological and Historical Studies on the Israelite Society before the Monarchy. Vetus Testamentum Supplements. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, Thomas Evan, and Thomas Higham, eds. 2005. Introduction: Radiocarbon dating and the Iron Age of the Southern Levant: Problems and potentials for the Oxford conference. In The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating: Archaeology, Text and Science. London: Equinox. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtheim, Miriam. 1976. Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom. Berkeley: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Loud, Gordon. 1948. Megiddo 2: Seasons of 1935–39. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, vol. 42. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, Nicolo, and Lorenzo Nigro, eds. 2000. Quaderni di Gerico 2. Rome: Universita Di Roma. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, Nicolo, Lorenzo Nigro, and Issa Sarie. 1998. Preliminary Report on the First Season of Excavations of the Italian-Palestinian Expedition at Tell es-Sultan/Jericho April-May 1997. Palestine Exploration Quarterly 130: 121–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, Nicolò. 2003. A Century of Excavations on the Spring Hill at Tell Es-Sultan, Ancient Jericho: A Reconstruction of Its Stratigraphy. In The Synchronisation of Civilisations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C. II. Edited by Manfred Bietak. Vienna: Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaftren, pp. 295–321. [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, Amihai. 1992. Archaeology of the Land of the Bible. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, Amihai, and C. Bronk Ramsey. 2008. C14 Dates and the Iron Age chronology of Israel: A response. Radiocarbon 50: 159–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, William L. 1992. The Amarna Letters. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins. [Google Scholar]

- Na’aman, Nadav. 1994. The “Conquest of Canaan” in the Book of Joshua and in History. In From Nomadism to Monarchy. Edited by Israel Finkelstein and Nadav Na’aman. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, pp. 218–81. [Google Scholar]

- Nigro, Lorenzo, and Hamdan Taha. 2009. Renewed Excavations and Restorations at Tell es-Sultan/Ancient Jericho Fifth Season—March–April 2009. Scienze Dell’Antichita Storia Archaeologia Anthropologia 15: 731–44. [Google Scholar]

- Nigro, Lorenzo. 2009. The Built Tombs on the Spring Hill and the Palace of the Lords of Jericho (‘ḎMR RḪ’) in the Middle Bronze Age. In Exploring the Longue Duree: Essays in Honor of Lawrence E. Stager. Edited by J. David Schloen. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 361–76. [Google Scholar]

- Nigro, Lorenzo. 2016. Tell es-Sultan 2015: A Pilot Project for Archaeology in Palestine. Near Eastern Archaeology 79: 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nigro, Lorenzo. 2020. The Italian-Palestinian Expedition to Tell es-Sultan, Ancient Jericho (1997–2015): Archaeology and Valorisation of Material and Immaterial Heritage. In Digging Up Jericho: Past, Present and Future. New York: JSTER. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, James B. 1969. Ancient Near Eastern Texts, 3rd ed. Princeton: Princeton University. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey, Christopher Bronk. 2009. Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates. Radiocarbon 51: 337–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, Christopher Bronk, Michael W. Dee, Joanne M. Rowland, Thomas F. G. Higham, Stephen A. Harris, Fiona Brock, Anita Quiles, Eva M. Wild, Ezra S. Marcus, and Andrew J. Shortland. 2010. Radiocarbon-Based Chronology for Dynastic Egypt. Science 328: 1554–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellin, Ernst, and Carl Watzinger. 1973. Jericho die Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen. Osnabrück: Otto Zeller. First published 1913. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, Ephraim. 1984. Excavations at Tel Mevorakh (1973–1976), Part Two: The Bronze Age, Qedem 18. Jerusalem: Hebrew Univ. [Google Scholar]

- Sukenik, Eleazar. 1942. Excavations in Palestine and Trans-Jordan, 1939-40: Tell Jerishe. Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities of Palestine 10: 198–99. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Thomas. 1987. The Origin Tradition of Ancient Israel. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Toombs, Lawrence E., and G. Ernest Wright. 1963. The Fourth Campaign at Balatah (Shechem). Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (BASOR) 169: 1–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufnell, Olga, Charles H. Inge, and Lankester Harding. 1940. Lachish 2: The Fosse Temple. London: Oxford Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tushingham, A. Douglas. 1952. The Joint Excavations at Tell es-Sulṭân (Jericho). Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 127: 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushingham, A. Douglas. 1953. Excavations at Old Testament Jericho. The Biblical Archaeologist 16: 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Toorn, Karel. 2000. Cuneiform Documents from Syria-Palestine: Texts, Scribes, and Schools. Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 116: 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- Van Seters, John. 2001. Pentateuch: A Social Science Commentary. Sheffield: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Watzinger, Carl. 1926. Zur Chronologie der Schichten von Jericho. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gessellschaft 80: 131–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Bryant. 1990a. Dating Jericho’s Destruction: Bienkowski is Wrong on All Counts. Biblical Archaeology Review 16: 45–49, 68–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Bryant. 1990b. Did the Israelites Conquer Jericho? A New Look at the Archaeological Evidence. Biblical Archaeology Review 16: 44–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Bryant. 1999. The Walls of Jericho. Bible and Spade 12: 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Bryant. 2005. The Rise and Fall of the 13th-Century Exodus-Conquest Theory. Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 48: 475–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Bryant. 2007. The Biblical Date for the Exodus Is 1446 BC: A Response To James Hoffmeier. Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 50: 249–58. [Google Scholar]

- Yadin, Yigael. 1959. The Fourth Season of Excavations at Hazor. The Biblical Archaeologist 22: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadin, Yigael. 1960. Hazor II: An Account of the Second Season of Excavations, 1956. Jerusalem: Magnes. [Google Scholar]

- Yadin, Yigael. 1961. Hazor III–IV: An Account of the Third and Fourth Seasons of Excavations, 1957–1958. Jerusalem: Magnes. [Google Scholar]

- Yadin, Yigael. 1972. Hazor: The Head of All Those Kingdoms. Schweich Lectures of the British Academy, 1970. London: Oxford Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yadin, Yigael. 1975. Yigael Yadin on “Hazor, the Head of All Those Kingdoms. Biblical Archaeology Review 1: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Yadin, Yigael. 1982. Israel Comes to Canaan: Is the Biblical Account of the Israelite Conquest of Canaan Historically Reliable? Biblical Archaeology Review 8: 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Yadin, Yigael, Y. Aharoni, R. Amiran, T. Dothan, I. Dunayevsky, and J. Perrot. 1958. Hazor I: An Account of the First Season of Excavations, 1955. James A. de Rothschild Expedition at Hazor. Jerusalem: Magnes. [Google Scholar]

- Younger, K. Lawson. 2009. Ancient Conquest Accounts. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).