Abstract

From the middle of the 20th century, the rise of anthropocentric beliefs partly inherited from the Abrahamic religions led to a change in mentality about ecosystems. The measurable signs of environmental exploitation and destruction and their consequences for human health, the shift to post-materialist values, and the growth of ethical philosophies (Land ethics, the Gaia Hypothesis, and Deep Ecology) were predictors of global ecological awareness. Progressively, human cultures (which are inseparable from religion) have become a priority for understanding relationships with the natural world. Alongside beliefs, individual subjectivities, influenced by the New Age, also positively affect sustainable values and practices. One of the community manifestations that demonstrate this is the ecovillage phenomenon. The sociological study of these new social realities influenced by the New Age is a relevant field of research in the frame of secularization or the criticism of this paradigm.

1. Introduction

This article contextualizes the secularization theory as the recomposition of the religious field and relates it to ecology. As part of conceptualizing the future of religion, we focus on New Age spiritualities and, more specifically, how they are manifested in one form of contemporary community setup, ecovillages. These communities present themselves as solutions to the crisis of (late) modernity, from environmental concern to spiritual anomy, through alternative ways of life and incorporating spiritual practices and beliefs closely connected with New Age spiritualities. Recently, they have been in the spotlight of the broader society because they present sustainable models, which can inspire practical solutions to the environmental crisis that are potentially replicable to broader society.

There are a small number of studies that focus on the spiritual dimension in ecovillages. Although this is a marginal topic, it is increasingly receiving attention from researchers in environmental and social sciences.

An analysis of the manifestations and effects of spiritualities in ecovillages is in progress in the doctoral thesis of one of the authors of this article. This article focuses on the place of these intentional communities in the debates over (de)secularization and ecology. The results characterize these communities as novel and paradoxical cases within these debates.

2. Secularization as a Religious (Re)configuration

Secularization is one of the incipient theories of the sociology of religion. Driven by modernity, this theory reflected on the loss of religious significance in religious institutions and organizations (Weber 1965; Luckmann 1967) and their authority (Habermas 2002), values (Giddens 2013), and individual beliefs and practices (Wilson 1982; Taylor 2007; Martin 1978). These institutions and organizations were sources of identity and meaning (Bruce 2011; Davie 1994). As a complex and multifaceted process, secularization has taken different trajectories in different contexts and societies (Moniz 2017). In general terms, the approaches to secularization theory of the 1950s and 1960s, which almost universally defended the loss of social and individual religious meaning, were abandoned in favor of the recognition of the persistence of religions and, in some cases, the sense of increased belonging, in non-European religious, geographic, and cultural contexts. Although terms such as desecularization (Berger 1999) and resacralization (Blonner 2019) account for these trends, the term secularization itself, due to its heuristic value, has undergone reconceptualizations to account for the multiple reconfigurations of the religious field. The multidimensional understanding (Dobbelaere 1981) of this term in contemporary times is necessary to account for paradoxes, such as the loss of the cultural and social meaning of religion and its persistence and reconfiguration in the individual sphere, the increase in the diversity of beliefs, the rise of conservative, orthodox, and even fundamentalist religious movements (Berger 1999, p. 6), and the rejection of traditional religious forms, mainly the hierarchical structure and doctrinal authority or core beliefs of religions, while practicing some of their elements (e.g., Buddhist meditation or Hindu Yoga).

Modernity has led to various transformations, such as the emergence of new religious movements (Barker 1982) and spiritual compositions. One of the analytical categories that emerged from these (new) spiritualities, which arose as alternatives to institutional religions based on individual experience, was New Age spiritualities, a term we explore later in this article. Due to secularization, New Age spiritualities can be analyzed as a recomposition of religious beliefs (Habermas 2002; Taylor 2007; Davie 2015; Berger 2014; Woodhead and Heelas 2005). With the decline in the power of religious authorities and institutions and the increase in the public visibility and expression of religion and spiritual beliefs, people are free to choose what fits their unique spiritual path, configuring a spiritual market (Woodhead and Heelas 2005). This growing diversity entails a patchwork of beliefs and practices that, for the minority of authors who still defend the secularization theory, represents a decline in religious significance. However, as contended in this article, New Age is instead part of a reorganization of religious beliefs (Hervieu-Léger and Champion 1986).

These spiritualities raised criticisms about the potential manipulation and exploitation of individuals for financial purposes, as the promoters of some groups do not consider collective responsibility, and specific practices lack regulation and control. However, several authors (Beyer 2000; Sutcliffe and Gilhus 2014; Woodhead and Heelas 2005; Taylor 2010) show how New Age spiritualities, as a common ground, reject institutionalized religions, configure collective responsibilities, and promote moral values. Different collaborative configurations were created, including (spiritual) ecovillages. These spiritualities focus on promoting personal growth, self-awareness, compassion, and empowerment, and any allegation regarding their practices must be contextualized. New Age spiritualities integrate components from diverse origins (Pinto 2022). While generally viewed with reverence and admiration, there are instances where these spiritualities may be extracted from their original cultural context, thereby exposing them to the risk of being misconstrued, resulting in the propagation of prejudiced generalizations and even the promotion of imbalanced power dynamics.

3. A New Ethic of Care: Denouncement of the Environmental Crisis

Until the middle of the 20th century, Western ethics presented human beings as hierarchically superior to other species in the biotic community. The utility of nature was exclusively for the satisfaction of human needs, and, therefore, it could be exploited and even dominated. This anthropocentric concept of land, often associated in a careless and unfounded way with Abrahamic religions, does not exclude concerns about the natural world but highlights the urgency of a new generalized ethic of care and conservation of the natural world.

Understanding terrestrial resources as finite and their exploitation’s negative consequences marked a turning point in global consciousness after the Second World War (Schmidt et al. 2018)1. This change in attitudes towards the environment was mainly due to two explanations, one objective and the other subjective (Running 2012). The first uses the measurable signs of problems associated with the deterioration of ecosystems and their effects on human health. Some examples were the destruction of soils by the use of pesticides in agriculture (Carson 1962), the warning of the limits of natural resources (Ehrlich 1968; Meadows et al. 1972; Duncan 1989), the harmful effects on the biosphere of atmospheric pollution (Margulis and Lovelock 1974), such as changes in climate patterns, global warming, and the greenhouse effect (Revelle and Suess 1957), and the massive extinction of many species (Kolbert 2014).

Subjective explanations, on the other hand, are based on the transformation of values, which include famous theories, such as the post-materialist theory (Abramson and Inglehart 1995) and the new ecological paradigm (NEP) (Catton and Dunlap 1978).

Beck (1992) points to environmental risks as uncontrollable, an idea that Anthony Giddens (1990) metaphorized as the “Jagrená car”. This moving machine threatens human beings because it involves a constant escape from its control. Reflexivity concerning ecology and other social risks defined a new phase of reflexive modernity (Beck et al. 2000). Among the social changes that constitute this continuum, we can highlight the blurring of the division of political concerns and private modes of action, the dichotomy between state and civil society and class values (Offe 1985), the individual recomposition of values and norms and the consequent increase in subjectivities, the information technology revolution and “the economic crisis of capitalism and statism and the consequent restructuring of both” (Castells 1999, p. 412). For individuals, confrontation with these risks, which often threaten unknown consequences, can generate anxiety, and religion can present itself as a solution (Giner and Tábara 1999).

In the face of economic progress, security, and education, the post-materialist values of self-expression, social justice, freedom, and the defense of the environment thrive (Inglehart 1977). Ecology, sustainability, and development progressively enter the agenda and acquire a heuristic character.

The intersection of these transformations with the cultural sphere led to the emergence of a new disciplinary subfield, Religion, and Ecology.

4. Religion and Ecology

As a pluralistic concept, the term religion serves as a foundation for a diverse array of studies. A particularly notable aspect of this concept is its emphasis on examining the historic-cultural meanings and ethical values that inform the complex interactions and relationships between organisms, nature, the environment, and ecology (Haeckel 18662; Jenkins 2017).

Religion and ecology represent an emerging interdisciplinary field that studies the relationship between religious and spiritual worldviews and nature (Gottlieb 2009). This contemporary relationship presupposes an understanding of the influences of religion on the environment and vice versa. More specifically, it focuses on finding the responses of different beliefs to environmental problems and their influence on individual, social, and, primarily, political behavior and their effects on the environment (Jenkins and Chapple 2011). The relationship between these terms was first discussed at the Harvard conference, “Religion of world and ecology”, in 1991. This event developed three theses that connected environmental thinking with religious practices and thought patterns: religious worldviews shape environmental behavior; an environmental crisis represents a spiritual crisis; and, in turn, this crisis requires scholars to reexamine religious traditions with the ecological insights needed to develop more sustainable worldviews. Through these theses, the main challenge posed to the scientific community was to investigate the influence of religious and spiritual worldviews on ecological behaviors and beliefs (e.g., practices that favor or do not favor ecocentrism) (Tucker and Grim 2017).

To understand this relationship, it is necessary to consider two premises. The first is that the field was born from the reflection on the human errors that led to environmental risks and the destruction of nature. Defining what is wrong presupposes classifying what is right and what is normatively ecological. In this sense, “[a] thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community” (Leopold 1949, pp. 224–25). The second premise is that, with the increasing diversity of people and religious, spiritual, and cultural designations, it becomes more difficult to make universal claims about reality (Bauman 2011). However, there is increasing concern with interreligious dialogue and identifying cultural motivations and shared worldviews on eco-justice and sustainability (Tucker and Grim 2017) to find practical answers to global problems (Porter 2001; Jenkins 2008).

Three complementary methodologies emerge from the study of religion and ecology: recovery, reassessment, and reconstruction. The first relies on documentary sources to explain the religious perspective on the relationship between humans and the Earth, primarily through ethical codes and rituals. The second proposes a reassessment of the validity and questioning of traditional teachings (e.g., attitudes, practices, and ethics) about the environment in current circumstances. Finally, reconstruction proposes to adapt and modify reassessed rules (Tucker and Grim 2017).

Religions are ecological because they are a significant part of human history and are inevitably entangled with the environment (Bellah 2011). There can only be adequate ecological knowledge if one understands the culturally embedded humans who change ecological systems (Jenkins 2017). As Bergmann points out:

“Natural environments embed, carry, and nurture human life and faith. Faith, religion, belief, and spirituality appear in such a view as deeply natural forces […] Analyses of religion, therefore, must respect not only the subject, sociocultural, and historical dimensions of religious traditions but also the ecological functions of faith”.(Bergmann 2017, p. 14)

The entry of religions into an ecological phase presupposes the understanding that they significantly shaped the cultural roots of sustainability problems (Jenkins 2008) and developed essential resources to help us perceive and respond critically to suffering and injustice (Tucker 2003). An example is the Christian heritage in the West, which, although it was criticized for promoting an anthropocentric mentality (Leopold 1949; White 19673), has been reformulated around an ecological cosmology (Berry 1988; Tucker 2003; Grim and Tucker 2014; (in the Catholic case) Hart 2009), or even a cosmic pietism (Giner and Tábara 1999, pp. 66–71).

Religions, as cultural expressions, can create an ecological conscience—a reformulation of human nature and its ontology (Grim 2013, p. 265)—and contribute to self-reflection and understanding of sustainable development, including economic, ecological, and spiritual well-being. Similarly, the new religious movements and spiritual beliefs (framed in the New Age) appear to be essential definers of diverse environmentalist imaginations (Jenkins 2017).

The main phenomena that led to the development of religion and ecology were climate change, the development of technology, and the definition of spaces/places (Bergmann 2017). We intend to focus mainly on the first of these phenomena.

Veldman et al. (2014) point out four factors that help religions to engage with climate change. The first is the influence of these religions on the worldviews of believers, particularly their ability to encourage behavior change and to motivate activism. The second is responsiveness to global challenges through the growth of moral arguments around climate justice and interfaith collaboration. The third is the importance of the institutional and economic resources of religions. Furthermore, beliefs, as sociocultural driving forces, provide and enhance the communicative communal processes of social connections and collective actions (Veldman et al. 2014).

Religions can provide moral and ethical guidelines and aspirations for a self-reflective process, which can lead to changes in behavior and the creation of new, sustainable communities (Tucker 2008). This step toward collective change is a resource that can be mobilized for political action. To this extent, Roger Gottlieb (2006) points out the importance of the environmental work of leaders (1) who preach a green gospel, which “is likely to have more of an effect than statements by, say, a comparable number of college professors” (Gottlieb 2009, p. 10). Two examples of this were the publications of the encyclical Laudato Sí (June 2015) and the Islamic Declaration on Global Climate Change (18 August 2015), which were shown to influence the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Agreement on climate change, 12 December 2015 (Tucker and Grim 2017). However, although these were important milestones, neither the author of the encyclical, Pope Francis nor the authors of the Islamic Declaration were the first to pay attention to environmental issues within their statements. According to Santos (2017), the first time the theme of environmentalism appeared in a Catholic document was in November 1970, in the speech of Pope Paul VI at the assembly of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Subsequently, Pope John Paul II, using Francis of Assisi, incorporated environmental issues in the message to celebrate the XXIII World Day of Peace in 1990. Furthermore, Benedict XVI tried to produce measures to make the Vatican carbon-neutral4. In the case of Islam, there are prominent examples concerning the understanding of nature, such as the lectures delivered by Seyyed Hossein Nasr in 1966, the development of the Islamic Foundation for Ecology and Environmental sciences in the mid-1980s (Bagir and Martiam 2017 p. 79), and the testimony of Abdullah Omar Nassef5 in the 1986 Assisi Declaration on Nature, regarding the Islamic environmental ethic.

Furthermore, Gottlieb (2006) also highlights the importance of religious communities (2), which, through religious groups and associations, play significant roles in shaping a sustainable future, as well as the value of environmental policies (3) reinforced by spiritual resources and environmental movements (4), interpreted as religious movements. Religious environmentalists (Dunlap and McCright 2015), often seen as ecological and political activists, generally challenge private property’s prerogatives and governments’ complicity with economic growth instead of environmental protection (Gottlieb 2009). However, there is increasing concern about defining sustainability policies, and many policymakers already recognize the role of cultural and religious values in shaping a sustainable future (Klinkenborg and Fuchs 2021). From this relationship emerged a set of essential interdisciplinary focuses for the current political debate, such as religion and animals, which are intended to explore forms of coexistence with non-human species on earth, the importance of places for the cultural understanding of beliefs, and how moral communities interpret specific environmental problems.

In short, religions have entered an ecological phase (Gottlieb 2009). Although traditional religions present anthropocentric values, they are able, through their institutional power and moral and ethical authority, to help change attitudes, practices, and public policies to help create a more sustainable world (Tucker 2008).

The increase in demand for spirituality based on nature or naturalists (Barros and Betto 2009, p. 22) follows three other trends that restructure the religious field (Lynch 2007): the rejection of patriarchal forms of religion; the movement to resacralize the sciences, with an emphasis on quantum physics and cosmology (Capra 1996; Ferguson 1981; Commoner 1971; Ehrlich 1968); and the adaptation of the spiritual quest to the values of liberal societies. These transformations are the primary roots of what Lynch (2007) calls progressive spirituality. The impulse of this spirituality, through a contesting posture with modernity and popularized in apocalyptic and utopian subcultures, led to the appearance of the New Age movement (Pinto 2022).

Since the end of the Second World War, the New Age has been an alternative to the dominant religious trends; however, it only became popular in the 1960s and 1970s through counterculture movements, of which the hippies are the most illustrative example. Initially driven by the mass media, namely literature (Spangler 1976) and cinema (Fry 2008), it was from reflective modernity, with the appearance of the World Wide Web, that these beliefs and practices were driven into the cultural mainstream, framing them within ecological and sustainable concerns in the public space. New Age is used as an umbrella term for individual subjective beliefs that are influenced by esoteric (Western), occult, gnostic, alchemist, and philosophical (such as neo-Pythagorism, Stoicism, Neo-Platonism) practices or beliefs, as well as Eastern religions and paganism (Pinto 2022). The biosphere is characterized by rejecting the dualisms of God–nature, man (dominator)–nature, and rationalism–reductionism, replacing them with an ecological paradigm and a planetary conscience (Sutcliffe and Gilhus 2014). In this way, the New Age allows “new relationships with oneself, with others, and with nature” (Monteiro and Mascarenhas 2020, p. 215). Nature is seen as something pure and supreme, an original state of the world, which must be defended (Vaillancourt 2002, p. 148). Although this idea is present in institutionalized religions, mainly in Eastern traditions (Watling 2009; Grim 2013), it is in New Age beliefs that spiritual devotion in terms of ecological balance is crucial (Giner and Tábara 1999, p. 61; Lewis and Kemp 2007). The idea of holism—that everything is connected in the network of life (Capra 1996)—is essentially the cause of this affinity. In the New Age, holism shifted from a concern “with Holistic Health to its quest for unitive consciousness, and from ecological consciousness to the idea of global networking” (Hanegraaff 1996 p. 119). In the pursuit of holism in the New Age context, two emerging theories of response to the climate crisis stand out (Katinić 2013): ecosophy, which later gave rise to deep ecology (Naess 1973), and the Gaia hypothesis (Lovelock [1979] 1991), which, through its analytical models, reconfigured itself as a theory (Dutreuil 2016). The first of these theories defends the appreciation and recognition of the interconnection of all species in the biosphere, accompanied by a change in moral and ethical values and awareness of the entire ecosystem (Boff 2008, p. 157). More specifically, “it defends biospheric egalitarianism, diversity, social symbiosis, anti-class posture, complexity instead of complication, local autonomy, and decentralization” (Katinić 2013, p. 3). The second theory argues that the planet Earth (and each of its subsystems: the atmosphere, hydrosphere, pedosphere, and biosphere), as with a living organism, functions as a homeostatic, self-regulating system. As such, the Earth’s evolutionary process must be observed through the interconnection of the layers that constitute it. The repercussions of the developments in the idea that the Earth is an interdependent living system resulted in proposals for cooperation and collaboration with the natural world (Latour 2017). Its association with the New Age takes this idea further, considering the Earth, but also the cosmos (Faivre 2010, p. 12), as a conscious organism—Gaian spirituality (Taylor 2010, p. 16)—and even as “intelligent” (Hanegraaff 1996, p. 156). The ecological thinking of New Age spiritualities, even in their criticism of traditional religious worldviews, is not inherently secular. These spiritual ethics can be understood as new environmentalism, a consequence of spiritual bricolages. This connection to the spirituality of the natural world forms a patchwork of practices and beliefs from shamanism, paganism, the two philosophical theories stated above, and many other religious and spiritual beliefs. This could result in a new environmental vision, boost reconfigurations, or even grow revivalist beliefs, challenging the secular theoretical framework.

The New Age prioritizes individual well-being—the self. However, it also manifests in various collective recompositions, generally characterized by diversity (of beliefs, ethnicities, sexual identifications, etc.), tolerance, and sustainability (economic, social, environmental, and spiritual). In addition to the possibility of changing individual ways of living, many New Age adherents are drawn to collective environmental causes and participate in activities such as organic farming and permaculture (Lewis and Kemp 2007). The best illustrative examples are ecovillages. These are primarily intentional and rural communities, which are excellent living laboratories (Fois 2019, p. 109) for alternative and regenerative experiences for a sustainable future. These heterotopic places form a network combining various aspects, such as ecological design and construction, green (Biological) production, renewable energies, community lifestyle, spiritual practices, and holistic views. Through education, they disseminate their ideas and alternative practices, essentially encouraging a (re)connection with nature, personal care (physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual), and community life. Their practices include reducing waste, growing their food, following a vegetarian diet, using renewable energy sources, sharing resources, and working collaboratively to configure behavior, norms, and values that challenge modernity’s conventional ways of living. This intentional lifestyle can be understood as a form of Alternation (Berger and Luckmann 1999) that is successfully reflected in a decrease in the negative impact on the ecosystem (Daly 2017). The internalization and institutionalization of these norms by subsequent generations, along with efforts to apply sustainable models to the general community (Barani et al. 2018), allow the passage of these alternative practices into the social mainstream. Currently, the ecovillages of the global North can be perceived as places in transition, that is, as models of social innovation, as alternatives to the dominant culture, and structural transformation (namely in how citizenship is exercised).

Currently, ecovillages are growing (GEN n.d.; Liftin 2014; Wiest et al. 2022) in relevance and number, with approximately 10,000 communities (GEN n.d.) already in existence. This is partly a result of the dissemination of information, mainly online, such as through ecovillage networks (e.g., GEN), social networks, and ecovillage websites. Other significant sources are informational tourism pages (e.g., TripAdvisor) and, in particular, the dissemination of workshops by New Age social media groups. Culture and spirituality, mainly of the New Age type, and criticism of Western institutional religions, namely Christianity, are not primary dimensions of ecovillages (regardless of whether they are self-styled as spiritual or not) but also the most crucial dimensions for their inhabitants6. Kindig (2014) identifies some of the manifestations of these forms of culture and spirituality, such as artistic expression, cultural activities, rituals, celebrations, respect and support for spiritual demonstrations, shared vision and respect for cultural heritage, flexibility in response to difficulties, understanding the interconnectedness of all elements of life on Earth (the fundamental idea of deep ecology), and the creation of a world of peace, love, and sustainability. Through exploratory research on the Global Ecovillage Network (GEN) website and the forthcoming publication of a systematic review of the literature by the authors of this article, it is possible to identify that spirituality in most ecovillages not only integrates cultural manifestations but all dimensions of social life, assuming itself as a total social phenomenon. The communities that demonstrate this most notably are spiritual ecovillages.

5. Method

This article results from an extensive literature review about the effect of secularization on the reconfiguring of beliefs and the appearance of New Age spiritualities in the West. Framed within this investigation, we aim to explain how inner subjective experiences manifest in spiritual, ecological intentional communities, specifically in spiritual ecovillages. This investigation allows exploratory contact with theory and preliminary results of a systematic literature review. Data recollection maps the spiritual ecovillages in the world. In subsequent research, we aim to conduct observations, interviews, and photorecordings from members of ecovillages in Portugal, the country under investigation. The primary objective of this data collection process is to determine how spirituality is manifested and to explore its impacts on individuals, communities, and the surrounding context. This study is novel in that it gathers the first data focused on the composition of New Age spiritualities in Portugal and nurtures knowledge of the continuous reflections on (de)secularization. Additionally, this study is innovative because it offers some understanding of an often overlooked dimension in strategies to reproduce the sustainable models of ecovillages in broader society.

The main focus of this research is to present the direct relations between secularization, as a reconfiguration of religion, and ecology, introducing spiritual ecovillages as illustrative examples of the dialogue between New Age spiritualities and their community configurations. The article briefly highlights the debates over secularization that contextualize the New Age spiritualities (1), relates them in a broad sense to the relation between religion and ecology (2), and then contextualizes ecovillages specific sites of the manifestation of the contemporary relation of between these terms (3).

6. Spiritual Manifestations in Ecovillages

The authors carried out a systematic literature review over the last decade on ecovillages (or intentional communities) and the New Age (and spiritualities) to identify spiritual manifestations in ecovillages or spaces configured as such. Although the results are in preparation for submission to a scientific journal, we can already present some here due to their relevance.

Utilizing the PRISMA scheme, 49 carefully selected articles were analyzed7. The results demonstrate that the concern over the academic investigation of the spiritual dimension in ecovillages is recent, mainly in the last five years, and primarily in European (based on the geographic location of the empirical data collection). Just over half of these studies have an impact factor (Science Journal Ranking) but present a low score. Ecovillages are studied more by researchers from the environmental sciences and social sciences, mainly from Geography (and urban planning), Economics and Administration, International Relations and Communications, and Sociology, who opt mostly for longitudinal studies of an ethnographic nature. Therefore, most analyzed studies used interviews and participant observation as data-collection methods. They were published in several journals in the social sciences and environmental sciences related to community life, ecology, and sustainability.

The qualitative analysis of the literature essentially identified three ways of manifesting spiritualities in ecovillages: with nature, with communities, and with oneself (interiority). In general, the natural world is seen as intrinsically spiritual. As with Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis and pantheistic religions, the Earth (as a mother), or the divine, connects all the material and immaterial planes in an interrelated web of life (Capra 1996) and represents a communicative and even an intelligent being. This vision structures a new relation and ethics with nonhuman species—ecocentrism—and, consequently, new forms of communal life and individual beliefs.

In community life, spirituality is often considered necessary. Regardless of the ecovillage’s denomination, secular or spiritual, spirituality is manifested as an expression of its identity through cultural practices, such as art (plastic arts, dances, and singing), rituals (meals, collective constructions, sacred feminine, readings and recitations about the environment, etc.), seasonal celebrations (festivals, fairs, etc.), physical practices (Yoga, shamanic exercises, and meditation), and transformative and emancipatory education. Most of the literature reviewed spiritually is a catapult to changing values and supports the collectivity’s union, cooperation, resilience, distribution, and self-organization.

Within a community panorama generally characterized by a diversity of beliefs, individual manifestations of faith are highly relevant, influencing personal happiness (boosting actions that allow lasting states of positive feeling), mediating individual well-being and health (through the integration of physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual dimensions into human development), and developing environmental awareness (via immanent spiritual messages and daily tasks, such as gardening and cooking).

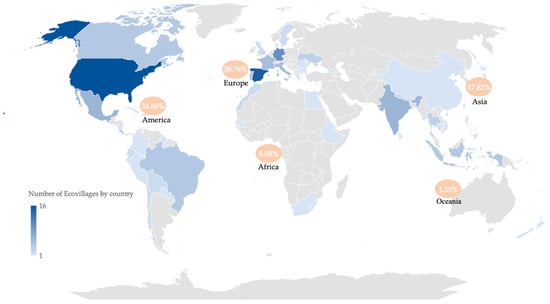

Although ecovillages incorporate spiritual practices in the community or individually, there are other priorities besides this. Those for which this focus is a priority are called spiritual ecovillages. There are 132 established or aspiring spiritual ecovillages, of which 129 were identified and mapped (Figure 1). They are mainly located on the European and American continents, particularly in North America. These results show the spiritual heritage of the ecovillages of the global North, shaped by the counterculture movements of the 1960s and 1970s, but also their material privilege (Liftin 2014). This setup makes it more manageable for ecovillages from the global North to prioritize personal and spiritual realization —post-materialistic values (Inglehart 1977)—over material necessities. In the global South, many ecovillage work to rehabilitate and regenerate traditional configurations with material needs (e.g., food security, access to and retention of clean water, and economic stability). The analysis of any specific ecovillage cannot be reduced to this dichotomy but must be contextualized as a complex site of interrelated cultural, political, environmental, economic, and social factors.

Figure 1.

Map of established or aspiring spiritual ecovillages listed in GEN in January.

7. Discussion

The religious field in modernity must necessarily play with the concept of pluralism and individualism (Vilaça 2006). Secularization is in dialogue with these concepts and, due to its heuristic value, has been reconfigured to account for the transformations in the religious field. As a multilevel sociological tool, the term secularization permits the understanding of religious and social transformations in the public sphere, internal changes in traditional religions, and shifts in individual beliefs. For instance, secularization enables the knowledge of the increased public visibility of New Age spiritualities, how these beliefs affect traditional religious institutions, and how they are embedded in personal development narratives.

The increase in environmental awareness inaugurated a new field of study—Religion and Ecology—and the combination of two significant tendencies in the religious field, the anthropocentric rejection of religion and the increase in the embedding of contemporary spiritualities in ecological ethics. Focusing on the second trend, we highlight intentional, sustainable communities that manifest New Age spiritualities as central to their daily lives, called spiritual ecovillages.

As a contemporary topic, these ecovillages integrate the debates on secularization and present themselves as paradoxical spaces with the potential for new discussions. In this way, the result of the contextualization of this phenomenon shows that in these spaces, we can find a diversity of individual beliefs, mainly of the bricolage type, which focuses on personal development, the rejection of traditional religions, and also the reappreciation (and sometimes reappropriation) of ancient beliefs, traditional forms of spiritual knowledge, and even specific practices or beliefs from traditional religions that involve collective rituals, celebrations, and moral guidance.

The early results of the systematic literature review on the inhabitants’ representations of spiritual manifestations in ecovillages corroborate those above. The inhabitants of ecovillages seek sustainable communal ways of life that prioritize the search for individual meaning and purpose through a spiritual dimension, characterized as alternatives to (and critical of) traditional religions (Heelas 1996; Heelas and Woodhead 2005). In the community set up, these spiritualities are expressed in rituals, celebrations, collective body-and-mind practices (Yoga, meditation, and mindfulness), and collective actions and advocacy (Hironaka 2014; Pike 2017; Fischer and Hajer 1999). These practices respect natural cycles, connect with nature (Gould 2005), and reinforce community togetherness and resilience (Harré 2011).

Future research on the recomposition of the religious field and new sustainable solutions must consider the effects of these spiritual communities on individuals, institutions, and even wider society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.P. and H.V.; methodology, T.P.; validation, T.P. and H.V.; formal analysis, T.P.; investigation, T.P.; resources, T.P. and H.V.; data curation, T.P. and H.V.; writing—original draft preparation, T.P.; writing—review and editing, T.P. and H.V.; visualization, T.P. and H.V.; supervision, H.V.; project administration, T.P. and H.V.; funding acquisition, T.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, grant number 2022.13643.BD.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | A large part of the changes in mentality was also due to scientific progress “from the naturalistic studies of the 16th century, through botany, zoology, other biological sciences to ecology in the 19th century.” (Silva and Schramm 1997, p. 358). |

| 2 | The author coined the term ecology in his work Generelle Morphologie der Organisme (Haeckel 1866). |

| 3 | White (1967) denounced traditional Western Christian beliefs as significant contributors to (not as creators of) the ecological crisis. In a reductive, Westernized, and disruptive argument, he even mentions that “Christianity is the most anthropocentric religion the world has ever seen” (White 1967, p. 1206). |

| 4 | For more information, see (Santos 2017, pp. 93–115). |

| 5 | General Secretary of the Muslim World League between 1983 and 1993. |

| 6 | Statement based on the results (0 to 10) of the impact assessment carried out by the GEN regarding the subjective opinions of community members about their lives and practices (Level 1) and the presence, scale, or frequency of specific practices in the community (Level 2) between February 2021 and February 2023. Map of regeneration dimensions in the order of importance: culture (7.22), regenerative design (7.17), social (6.78), ecological (6.54), and economic (6.38). The results are available at: https://ecovillage.org/impact/ (accessed on 30 January 2023). For more information, see https://ecovillage.org/sustainable-development-the-ecovillage-way/ (accessed on 30 January 2023). |

| 7 | Exclusion criteria used: (i) intentional communities or ecovillage explicitly or implicitly (practices and lifestyle exclusives to a single belief) self-styled or belonging to an institutional religion (e.g., Ashrams (Hinduist), charismatic Christian communities (Christianity), or Buddhist or Christian cenobitic communities); (ii) communities that do not take into account social and environmental regeneration; (iii) urban ecovillages; (iv) articles from a (systematic) literature review; and (v) articles published in a language other than Portuguese, English, or Spanish. |

References

- Abramson, Paul R., and Ronald Inglehart. 1995. Value Change in Global Perspective. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bagir, Zainal A., and Najiyah Martiam. 2017. Islam. In Routledge Handbook of Religion and Ecology. Edited by Willis Jenkins, Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Barani, Shahrzad, Amir H. Alibeygi, and Abdolhamid Papzan. 2018. A framework to identify and develop potential ecovillages: Meta-analysis from the studies of world’s ecovillages. Sustainable Cities and Society 43: 275–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, Eileen. 1982. New Religious Movements: A Perspective for Understanding Society. New York and Toronto: The Edwin Mellen Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, Marcelo, and Frei Betto. 2009. O amor fecunda o universo—Ecologia e espiritualidade. Rio de Janeiro: Agir. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Whitney. 2011. Ecology and Contemporary Christian Theology. Religion Compass 5: 376–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Ulrich. 1992. Risk Society: Toward a New Modernity. Londres: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Ulrich, Anthony Giddens, and Scott Lash. 2000. Modernização reflexiva: Política, Tradição e Estética no mundo Moderno. Oeiras: Celta Editora. [Google Scholar]

- Bellah, Robert N. 2011. Religion in Human Evolution: From the Paleolithic to the Axial Age. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter L. 1999. The Desecularization of the World: A Global Overview. In The Desecularization of the World. Resurgent Religion and World Politics. Edited by Peter L. Berger. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter L. 2014. The Many Altars of Modernity. Toward a Paradigm for Religion in a Pluralist Age. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter L., and Thomas Luckmann. 1999. A Construção Social da Realidade. Lisboa: DINALIVRO. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, Sigurd. 2017. Development in religion and ecology. In Routledge Handbook of Religion and Ecology. Edited by Willis Jenkins, Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, Thomas. 1988. The Dream of the Earth. San Francisco: Sierra Club. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, Peter. 2000. Religion and Globalization. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Blonner, Alexa. 2019. Reimagining God and Resacralisation. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boff, Leonardo. 2008. La opción Terra. La solución para la Tierra no cae del cielo. Madrid: Editorial Sal Terrae. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, Steve. 2011. Secularization. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, Fritjob. 1996. The Web of Life: A New Scientific Understanding of Living Systems. New York: Anchor Books Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, Rachel. 1962. Silent Spring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, Manuel. 1999. Fim de milênio. São Paulo: Paz e Terra. [Google Scholar]

- Catton, William R., and Riley Dunlap. 1978. Environmental Sociology: A New Paradigm. The American Sociologist 13: 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Commoner, Barry. 1971. The Closing Circle: Nature, Man, and Technology. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, Matthew. 2017. Quantifying the environmental impact of ecovillages and co-housing communities: A systematic literature review. Local Environment 22: 1358–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davie, Grace. 1994. Religion in Britain since 1945: Believing without Belonging. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Davie, Grace. 2015. Religion in Britain: A Persistent Paradox. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbelaere, Karel. 1981. Trend report: Secularization: A Multi-Dimensional Concept. Current Sociology 29: 3–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, Richard C. 1989. Evolution, Technology, and the Natural Environment: A Unified Theory of Human History. Paper presented at the St. Lawrence Section ASEE Annual Meeting, Binghamton, NY, USA, October 13–14; pp. 14B1-11–14B1-20. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, Riley, and Aaron M. McCright. 2015. Challenging Climate Change: The Denial Countermovement. In Climate Change and Society: Sociological Perspectives. Edited by Riley Dunlap and Robert Brulle. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dutreuil, Sébastien. 2016. Gaïa: Hypothèse, Programme de Recherche pour le Système Terre, ou Philosophie de la Nature? Ph.D. thesis, École Doctorale Philosophie, Paris, France, December 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich, Paul R. 1968. The Population Bomb. New York: Ballantine Books. [Google Scholar]

- Faivre, Antoine. 2010. Western Esotericism: A Concise History. New York: Suny Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, Marilyn. 1981. The Aquarian Conspiracy: Personal and Social Transformation in the 1980s. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Frank, and Maarten Hajer. 1999. Living with Nature: Environmental Politics as Cultural Discourse. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fois, Francesca. 2019. Enacting Experimental Alternative Spaces. Antipode 51: 107–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, Carrol L. 2008. Cinema of the Occult: New Age, Satanism, Wicca and Spiritualism in Film. Bethlehem: Lehigh University. [Google Scholar]

- GEN. n.d. About GEN. Who Is in the GEN Network? Available online: https://ecovillage.org/about/about-gen/ (accessed on 16 February 2023).

- Giddens, Anthony. 1990. The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, Anthony. 2013. Sociologia. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. [Google Scholar]

- Giner, Salvador, and David Tábara. 1999. Cosmic piety and ecological rationality. International Sociology 14: 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, Roger. 2006. A Greener Faith: Religious Environmentalism and Our Planet’s Future. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, Roger. 2009. Introduction: Religion and Ecology—What is the connection and Why Does it Matter? In The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Ecology. Edited by Roger Gottlieb. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 16–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, Rebecca K. 2005. At Home in Nature: Modern Homesteading and Spiritual Practice in America. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grim, John. 2013. The Roles of Religions in Activating an Ecological Consciousness. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Grim, John, and Mary Evelyn Tucker. 2014. Ecology and Religion. Washington, DC: Island Press. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 2002. Religion and Rationality. Essays on Reason, God and Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haeckel, Ernest. 1866. Generelle Morphologie der Organismen. Allgemeine Grundzüge der Organischen Formen-Wissenschaft, Mechanisch Begründet Durch die von Charles Darwin Reformirte Descendenztheorie, von Ernst Haeckel. Berlin: G. Reimer. [Google Scholar]

- Hanegraaff, Wouter J. 1996. New Age Religion and Western Culture: Esoterism in the Mirror of Secular Thought. New York: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Harré, Niki. 2011. Psychology for a Better World: Strategies to Inspire Sustainability. Auckland: University of Auckland. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, John. 2009. Catholicism. In Roger Gottlieb, The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Ecology. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heelas, Paul. 1996. The New Age Movement. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Heelas, Paul, and Linda Woodhead. 2005. The Spiritual Revolution: Why Religion Is Giving Way to Spirituality. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Hervieu-Léger, Danièle, and Francçoise Champion. 1986. Vers un nouveau christianisme? Introduction à la sociologie du christianisme occidental. Paris: Cerf. [Google Scholar]

- Hironaka, Ann. 2014. Greening the Globe: World Society and Environmental Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, Ronald. 1977. The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Willis. 2008. Global Ethics, Christian Theology, and the Challenge of Sustainability. Worldviews 12: 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, Willis. 2017. Whose religion? Which ecology? Religious studies in the environmental humanities. In Routledge Handbook of Religion and Ecology. Edited by Willis Jenkins, Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Willis, and Christopher K. Chapple. 2011. Religion and Environment. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 36: 441–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katinić, Marina. 2013. Holism in deep ecology and gaia-theory: A contribution to eco-geological science, a philosophy of life or a new age stream? The Holistic Approach to Environment 3: 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kindig, Christopher. 2014. The Cultural/Spiritual dimension—Global Ecovillage Network. Available online: https://ecovillage.org/culturalspiritual-dimension/ (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Klinkenborg, Hannah, and Doris Fuchs. 2021. Religion: A resource in European climate politics? An examination of faith-based contributions to the climate policy discourse in the EU. Zeitschrift Für Religion, Gesellschaft Und Politik 6: 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbert, Elizabeth. 2014. The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. New York: Henry Holt and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 2017. Facing Gaia. Eight Lectures on the New Climate Regime. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leopold, Aldo. 1949. A Sand County Almanac. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, James, and Daren Kemp. 2007. Handbook of New Age. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Liftin, Karen T. 2014. Ecovillages: Lessons for Sustainable Community. Cambridge: Polity press. [Google Scholar]

- Lovelock, James E. 1991. Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth. Oxford: Oxford University Press. First published 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Luckmann, Thomas. 1967. The Invisible Religion: The Problem of Religion in Modern Society. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, Gordon. 2007. The New Spirituality an Introduction to Progressive Belief in the Twenty-First Century. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Margulis, Lynn, and James E. Lovelock. 1974. Biological modulation of the Earth’s atmosphere. Icarus 21: 471–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, David. 1978. A General Theory of Secularization. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, Dennis, Donella Meadows, Jorgen Randers, and William W. Behrens, III. 1972. The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind. New York: Universe Books. [Google Scholar]

- Moniz, Jorge B. 2017. As teorias da secularização e da individualização em análise comparada. Estudos de Religião 31: 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, Dalila, and Paula V. Mascarenhas. 2020. “Estar com o universo”. As novas espiritualidades dos movimentos sociais da nova era. In Eu sou tu. Experiências ecocríticas. Edited by José Pinheiro neves, Pedro rodrigues Costa, Maria Paula Mascarenhas, Ilda Teresa de Castro and Virginia Román Salgado. Braga: CECS—Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade, pp. 207–40. [Google Scholar]

- Naess, Arne. 1973. The Shallow and the Deep, Long Range Ecology Movement. Inquiry 16: 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offe, Claus. 1985. New Social Movements: Challenging the Boundaries of Institutional Politics. Social Research 52: 817–68. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, Sarah M. 2017. For the Wild. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, Tiago. 2022. New Age: Uma revolução cultural em dois momentos. Cadernos IS-UP 1: 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, Jean. 2001. The Search for a Global Ethic. Theological Studies 62: 105–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelle, Roger, and Hans E. Suess. 1957. Carbon dioxide exchange between atmosphere and ocean the Question of an Increase of Atmospheric CO2 during the Past Decades. Tellus 9: 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Running, Katrina. 2012. Examining Environmental Concerns in Developed, Transitioning, and Developing Countries. World Values Research 5: 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, Renan W. 2017. A salvação agora é verde: Ambientalismo e sua apropiação religiosa pela Igreja Católica. Master’s thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Luísa, Mónica Truninger, João Guerra, and Pedro Prista. 2018. Sustentabilidade Primeiro Grande Inquérito em Portugal. Lisboa: Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, Elmo R., and Fermin Roland Schramm. 1997. A questão ecológica: Entre a ciência e a ideologia/utopia de uma época. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 13: 355–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangler, David. 1976. Revelation: The Birth of a New Age. San Francisco: Rainbow Bridge. [Google Scholar]

- Sutcliffe, Steven, and Ingvild Gilhus. 2014. New Age Spirituality—Rethinking Religion. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Bron R. 2010. Dark Green Religion: Nature Spirituality and the Planetary Future. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: The University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Charles. 2007. A Secular Age. Cambridge and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, Mary E. 2003. Worldly Wonder: Religions Enter Their Ecological Phase. Chicago: Open Court. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, Mary E. 2008. World religions, the earth charter, and sustainability. Worldviews 12: 115–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, Mary E., and John Grim. 2017. The movement of religion and ecology. In Routledge Handbook of Religion and Ecology. Edited by Willis Jenkins, Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt, Louis. 2002. Écologie, christianisme et Nouvel Age: Quand nature et spiritualité se rencontrent. Studies in religion/Sciences Religieuses 31: 145–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldman, Robin G., Andrew Szasz, and Randolph Haluza-DeLay. 2014. How the World’s Religions are Responding to Climate Change. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Vilaça, Helena. 2006. Da torre de Babel às Terras Prometidas—Pluralismo Religioso em Portugal. Porto: Edições Afrontamento. [Google Scholar]

- Watling, Tony. 2009. Re-imagining the human-environment relationship via religious traditions and New Scientific Cosmologies. In Technology, Trust, and Religion: Roles of Religions in Controversies on Ecology and the Modification of Life. Edited by Willkiem B. Drees. Utrech: Leiden University Press, pp. 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Max. 1965. The Sociology of Religion. London: Methuen & Co Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Bryan. 1982. Religion in Sociological Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- White, Lynn. 1967. The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis. Science 155: 1203–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiest, Franziska, M. Gabriela Gamarra Scavone, Maya Tsuboya Newell, Ilona M. Otto, and Andrew K. Ringsmuth. 2022. Scaling Up Ecovillagers’ Lifestyles Can Help to Decarbonise Europe. Sustainability 14: 13611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhead, Linda, and Paul Heelas. 2005. The Spiritual Revolution: Why Religion is Giving Way to Spirituality. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).