Abstract

The Seven Sisters Festival (also known as Qixi Festival) is especially important to Cantonese women, with differences in syncretic religious practices and beliefs between marriage resistance and nonresistance regions. Despite being forerunners in the wave of women’s migration since the 19th century, developments in ritualistic practices and sisterhood structures of these Cantonese women after their migration remain largely unexplored. This article investigates the formation of Milky Way associations, liturgical sororities for organizing festival celebrations and worship of the Seven Sisters, and its influence on the social and religious lives of Cantonese women in Singapore. Through highlighting the coexistence of different belief systems, shifts in interest from China as the center of sociocultural origin to post-war/post-independence Singapore in the periphery, as well as negotiations with space, this article shows that Cantonese women have been active agents in reorganizing themselves, interacting within and outside of their communities, and engaging in heritage meaning-making. By compiling a non-exhaustive list of over 100 Milky Way associations in Singapore in the 1930–1940s, this article spotlights the magnitude and significance of the Seven Sisters Festival, which has disappeared since the 1970s with little material trace.

1. Introduction

The Qixi Festival, also known as Double Seventh Festival, or Qiqiao Festival, was one of the most important traditional Chinese festivals for women in Singapore, especially amongst the Cantonese who affectionately refer to it as the Seven Sisters Festival. Despite its significance, research on this festival in Singapore (C. S. Wong 1987; Comber 2009; Tan 2018; Lai 2020) is surprisingly limited. For instance, relying on archives of oral history interviews from the 1980s, Tan (2018, p. 23) noted that “religious beliefs and practices reported by informants often concur only to a certain degree, and occasionally contradict one another”. This gap is attenuated by the fact that there is a lack of material trace of this festival since its disappearance in the 1970s—archival sources such as membership records are scant, festival paraphernalia is often ephemeral and burnt after the celebrations and known visual documentation of the festival is lacking. This is in stark contrast to the large body of scholarly works on the festival in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Japan (e.g., Pan et al. 2020; Chu 2010; Bi 2013; S.-l. Hong 1988; Poon 2004; Poon and Wong 2011).

Furthermore, while there is burgeoning literature on the intersections of Chinese women and religiosity (e.g., Stockard 1989; Overmyer 1992; Grant 1995; Bryson 2015), few have investigated the developments after their migration to Southeast Asia (Topley 1954, 1955, 1956; Show 2018).

The purpose of this paper is threefold. First, it aims to reconcile seeming contradictions in Seven Sisters Festival beliefs and practices amongst the Cantonese. Second, this paper looks at how the high proportion of Cantonese women migrants, their sorority structures and large-scale public celebrations contributed to an overwhelming Cantonese prominence during the festival in Singapore despite the overall Cantonese population being outnumbered by the Hokkiens and Teochews. Third, this paper examines the formation of Milky Way associations (religious sororities for the organization of the Seven Sisters Festival mass celebrations) and its influence on the social and religious lives of Cantonese women in Singapore. In particular, through case studies on the coexistence of different belief systems, shift in interests from China as the center of sociocultural origin to post-war/post-independence Singapore in the periphery, and negotiations with space, I show that the Cantonese women were active agents in reorganizing themselves, interacting with other communities, and engaging in meaning making. I argue that the pre-condition that made possible this emergence was Cantonese women’s economic and intellectual independence from prescribed gender roles in existing patriarchal social systems.

It is in a similar vein to the growing body of literature investigating the histories of the everyday folk in Singapore (Warren 2003b; Dobbs 2003; Jason Lim 2013; Koh 2010; Loh 2013), especially those of women who are often invisible in pervasive patriarchal societies, such as entertainment hostesses and women factory workers (Warren 2003a; Jaschok and Miers 1994; Loh et al. 2021). Importantly, this article honors women whose role in the transmission of religious practices have often been overlooked.1

2. Methodology

In addition to looking into ancient Chinese texts to trace the origins and developments of the festival, documentary research for this article included a literature review of newspaper archives, oral history interviews, and an autobiography that provided an intimate perspective of the festival. Moreover, to provide a macro-view of the sociocultural shifts in Singapore and how it relates to the festival, I relied on statistical data published in colonial, governmental, and academic reports for information such as population demographics, migratory patterns over the years, maps on population distribution, as well as wages across occupations.

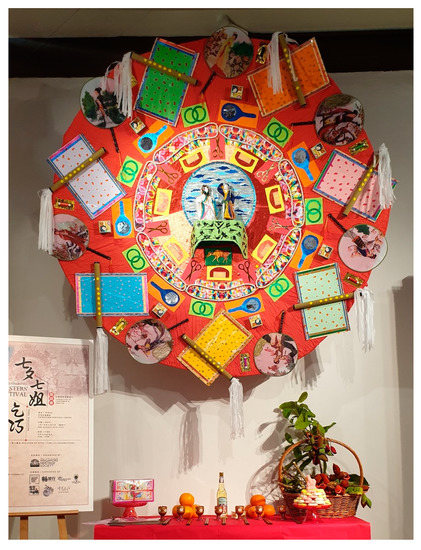

Notably, this paper presents fresh, first-hand data collected using ethnographic methodology including in-depth oral history interviews with relevant stakeholders using an open-ended list of questions, participatory mapping of spaces, and participatory photographic stills provided by interviewees.2 Ephemeral paraphernalia items distinct to the festival, such as the Seven Sisters Basin, were also recreated and exhibited to trigger memories and encourage participation from the community in this research (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A month-long mini exhibition, which features the recreated Seven Sisters Basin hung on the wall, was held in conjunction with a panel discussion titled “Remembering Seven Sisters Festival” in August 2019 to reach out to potential interviewees in Singapore for this research.

Aided by networks and outreach through social media, I interviewed diverse stakeholders involved in different aspects of the festival, including 91-year-old Fun Kwai Leng, who was a patron of a Milky Way association; 66-year old Cantonese Naam Mo priest Loke Weng Sun, who had performed related rituals; 88-year-old Kwang Ah Kui, who is the daughter-in-law of the Sai Bak Mun Milky Way association organizer; 87-year-old Tan Ah Ngan, who worked in a rubber factory and joined a Milky Way association organized by her colleague’s mother; as well as husband and wife duo Teo Bee Kim and Lee Chwee Choon who run one of the oldest remaining joss paper shops in Singapore that supplied related paraphernalia. I have included additional information of the interviews I conducted in the footnotes for a smoother reading experience and to differentiate them from published sources, which are cited in the main text.

There are no known official records on the Milky Way associations in Singapore. Even in the case of Shun Tak Kong Mei Sar Khai Wong Clan association, which is said to have held the most lavish Seven Sisters Festival celebrations in Singapore, not only was the Milky Way association not an official department within its formal organizational structure, but the festival was also not an activity recorded in the clan’s calendar of annual events.3

As such, another key contribution of this article is a non-exhaustive list of over 100 Milky Way associations, their addresses and contributions towards the China Relief Fund efforts, compiled from newspaper archives from 1938 to 1941, which allows us to map the magnitude of the Seven Sisters Festival celebrations organized by the Cantonese women in Singapore (Appendix A).

3. Historical Background

The Qixi Festival can be traced as far back as to the Han Dynasty. In Siminyueling 四民月令 by Cui Shi 崔寔 (103–170)—the earliest known record of worship directed to the Cowherd and the Weaver Fairy stars during this festival—practices included “making dry provisions, gathering wax (for oil lamps), laying a banquet with wine, dried meat, and seasonal fruits, as well as scattering fragrance powder”. It is also worth noting that Zhang Jiuling 张九龄 (678–740)’s Tang Liudian 唐六典and Tuoketuo 托克托 (1314–1355)’s Songshi 宋史recorded that the Qixi Festival was designated a holiday for government officials during the Tang and Song dynasties, suggesting its importance.

Over the long history of Chinese civilization, customary practices and beliefs related to the festival developed, adapted, and localized, giving rise to regional differences in syncretic religious content.4 For the Cantonese people, the focal point of this article, the festival is especially important.

As early as in the Southern Song dynasty, a poem in Liu Kezhuang 刘克庄 (1187–1269)’s collection Houchunji 后村集 described scenes of the festival in Guangzhou: “With melons placed on the altar, people cupped their fists in prayer while on their knees. Merchants selling Mahoraga dolls5 could be heard playing betting games with their customers. The Qixi Festival is of significance to the people in Guangdong, with celebratory lights illuminated till dawn”.

Detailed in the Zhonghua quanguo fengsu zhi 中华全国风俗志 (Record of Customs in the Whole of China) first published in 1922 (Hu 1988, p. 14), festival prayers in the Canton region start on the sixth evening of the seventh lunar month. Worship would be performed seven times, once for each of the seven fairies. Rituals relating to women’s marital status are prominent features of the festival, with unwed women participating in customs to “invite the celestials” (Yingxian 迎仙) and newlywed women conducting their last rituals to “bid farewell to the celestials” (Cixian 辞仙) before leaving the sorority. Prior to the festival, they would do embroidery and create different types of miniature using everyday items such as grass, colored paper, sesame, and rice grains. They were very competitive in showcasing their handicrafts. Even the less well-to-do households would organize such celebrations for the festival to the best of their ability. The Cowherd star is venerated on the seventh evening by only the males. Children also take part in the rituals at the period in between at noon on the seventh day.

Although outward expressions of festival celebrations (such as elaborate display of handicrafts) are shared, the religious practices and beliefs contrast starkly from regions within the Pearl River delta, such as Shunde, Panyu, and Nanhai counties, where esoteric marriage resistance customs abound.6 As noted in Shunde Xianzhi 顺德县志 (Gazetteer of Shunde County) published in 1853, “Single women in the village formed sworn sisterhoods to take care of each other and reject marriage. If forced into marriage, they would delay returning to their husbands, and even resort to hanging or drowning themselves to death”. While its origins remain unclear, there were generally two forms of marriage resistance: first, the “self-combed women” (Zi So Neoi 自梳女) who perform the ceremonial combing ritual to renounce marriage altogether, and second, the married women who refuse to consummate the marriage and cohabit with their husbands (M Lok Gaa 唔落家) (Topley 1975). The latter category would nonetheless financially support the husband’s family and even arrange a concubine for the husband as compensation (Jashok 1984, p. 46; Stockard 1989, p. 18). In interviews with “self-combed women” who worked as domestic workers in Singapore, the latter’s actions to maintain her chastity while supporting her husband and his children were considered respectable (I. C. Ho 1958, p. 38).

In these Canton regions with marriage-resistance practices, the festival was reconceptualized as one that exhorts notions of purity, chastity, and gender equality. This anti-marriage belief system is manifested in the legend related to the festival being propagated.7 While there are different versions of the legend, a common narrative shared in other parts of China (including regions in the Pearl River delta where marriage resistance is not practiced) highlights the annual reunion of the personified Cowherd and the Weaver Fairy stars who were separated across the Milky Way by the Jade Emperor for neglecting duties in plowing the land and weaving on the loom, respectively. Distinctively, the narrative in the marriage resistance regions differs on two key aspects.

The first difference revolves around their initial meeting, which ensued when the Weaver Fairy descended to Earth to take a shower and the Cowherd withholds her heavenly robe. In the commonly told version of the legend, they fell in love and married without parental approval. Contrastingly, the altered version in the marriage resistance regions asserts that the Weaver Fairy was forced to marry the Cowherd against her will as her modesty was insulted by having been seen naked. While the former reflects the independence of women in choosing their own husbands, the latter portrays women’s reluctance to marry (Sankar 1978, pp. 23–25).

The second key element in the marriage resistance version is the emphasis on the sworn sisterhood of the Weaver Fairy with the other six fairies.8 Notably, it was the sisters, rather than the usual parental authority, who were incensed by the marriage and permitted the couple to reunite only once a year across the Milky Way (Gray 1880, pp. 281–82). Female marriage resisters in the delta are sympathetic to the plight of the Weaver Fairy and pray to the Seven Sisters “for protection and strength to resist temptations from men” (I. C. Ho 1958, p. 141). Also, while the common account suggests that the seven fairies are daughters of the Jade Emperor with the Weaver Fairy being the youngest, an oral history interview I conducted with a Seven Fairies Temple caretaker describes their relationship as “fellow spiritual practitioners” (Tongxiu 同修).9

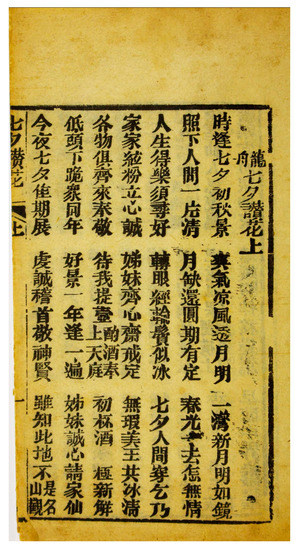

Coupled with the distinctive feature of separate residences for adolescent girls (referred to as girls’ houses) within the Pearl River delta where close sisterhoods were forged10, the Seven Sisters Festival is the most important festival of the calendar year organized by unmarried women from one or more of the girls’ houses and the entire village community was invited. Monthly membership contributions varied from 20 cents to three dollars a month (Stockard 1989, pp. 43–44). Elaborate preparations for the festival, including hand-embroidering miniature shoes, creating decorations from sesame seeds, and purchasing the necessary offerings, would begin months in advance. Liturgical texts, such as the “wooden-fish book” titled Qixi zanhua 七夕赞花 (In Praise of Flowers on Qixi), which emphasized the importance of sisterly bonds and virtues such as filial piety would be sung by the girls when performing worship rituals and making offerings to “beseech needlework skills” from the celestials during the festival (Figure 2).11

Figure 2.

Excerpt from Qixi zanhua (p. 1). The last four columns, read from right to left, emphasize strong sisterly bonds in upholding religious discipline and describe the Qixi festival rituals such as offering wine to the heavens, prostrating, and inviting the celestials to descend to Earth.

4. Migration of Chinese Women to Singapore

The onset of Chinese women migrating to Singapore began in the mid-19th century in the wake of the Taiping civil war. Prior, the population on the island were mostly transient male migrants intending to return home after working a few years (Wang 2000). Those with families in Singapore were generally individuals who were financially well off or part of the more settled communities such as the Straits Chinese and Malays. The introduction of female migrants was encouraged, as they were viewed as an economic force that could contribute to the development of Malaya, and there was a belief that having a domesticated Chinese population would help maintain order and peace in the colony (Vaughan 1974, p. 8; Chin 1984).

In addition to married women who came to join their spouses in the host country, a large majority of early Chinese female migrants were young, single Cantonese from regions around the Pearl River delta in Guangdong province. There were mainly two streams of Cantonese females. The first was from families with desperate economic conditions and regarded daughters as “a commodity on which money has been lost” (Croll 1978, p. 23). This included little girls trafficked as indentured maidservants (Mui Tsai 妹仔), blind singing girls (Maang Mui 盲妹), entertainment hostesses (Pipa Tsai 琵琶仔), and prostitutes (Ah Ku 阿姑) (Ong 1995; Julian Lim 1980; Song [1923] 1967, p. 253; Warren 2003a). The second stream comprised female laborers who aspired to autonomy and desired to see the world (Ye 1994, p. 88). Traditional Confucian views on what is considered a “socially valued way of life for a woman”, that is, to stay inside and be kept busy with childbearing and rearing, runs contrary to the ideology held by many of these Cantonese women.12 By the early 19th to the early 20th century, women all over Canton were already involved in cash-earning occupations out of their homes (Topley 1975).

Such liberal attitudes toward Cantonese women’s migration and involvement in the public sphere were not shared by the other Chinese subcommunities. For instance, despite many Teochew women earning subsidiary incomes from light industries (e.g., embroidery and joss paper making), which profited with the opening of Swatow as a treaty port in 1860, they, unlike their Cantonese counterparts in the silk industry, were not able to step beyond the family and into the public domain due to cultural sanctions in a male lineage-dominated community (Choi 2010). As observed by Ball (1925, p. 718), “to one accustomed in Canton and neighborhood to the constant presence of women in the fields and streets and on the river and sea, busy with various kinds of manual labor, it is strange to note their entire absence, with but trifling exceptions, in the country around Swatow”.

In 1881, Cantonese females formed over one-third of the total female population size in Singapore. Being the third-largest Chinese migrant community in Singapore, almost every one in three Cantonese was a female. This high percentage of Cantonese female migrants is striking compared to the other Chinese migrant communities (not including the Straits-born Chinese who had settled here): women accounted for only 6% in the largest Hokkien community, 7.5% in the second-largest Teochew community, and 0.64% in the fourth-largest Hainanese community (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Chinese population in Singapore.

Efforts to restrict the flow of immigration stepped in to control unemployment and economic distress in the Straits Settlements leading up to the Great Depression (Blythe 1947). Initially, the male quota was fixed at 1000 monthly but later fluctuated between 500 to 6000 monthly based on labor needs in Malaya. As no immigration quota was imposed on women, the cost of passage for women was far cheaper than those for men. In addition, ticket brokers would sell a quota ticket only if three or four non-quota tickets were bought at the same time so as to fill their ships. These factors contributed to the peak in migration and a high influx of women entering Singapore.

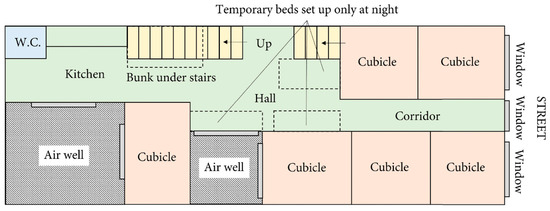

From 1933 to 1938, shiploads of Cantonese women—mainly from the Shunde and Dongguan regions—aged between 18 to 40 came to Malaya in search of a better future (Blythe 1947). The size of the Chinese female population in Singapore was only one-third that of the Chinese male population in the early 20th century, drastically increasing to two-thirds in the 1930s, and reaching close to 90% after WWII (Freedman 1957). These women engaged in different occupations such as domestic helpers, hawkers, tin miners, and construction workers (Lebra 1980). A large proportion of these Cantonese women congregated in the Ngau Ce Seoi (牛车水) area13 and lived in overcrowded cubicles (also known as coolie quarters) formed by a maze of interior partitions within two- or three-story shophouses (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Typical first-floor plan of a shophouse. Illustration adapted from Kaye (1960, p. 27).

With regard to the Seven Sisters Festival, it is important to note that while separate practices were observed by Cantonese men and women, it was the latter that proliferated in Singapore (TSFPMA 1938). Although Hokkien and Teochew families also observed the festival, celebrations were largely held in private within individual households.14 This is in stark contrast to the Cantonese sororities who organized large-scale festival celebrations, which were open to the public to visit. This coupled with the preponderance of Cantonese females in early Singapore and their organization of sororities contributed to the prominence of Cantonese rituals during the festival in Singapore.

In the following sections, I explore how Cantonese women reconfigured their basic structure of the sisterhood and adapted their religious practices outside of the original cultural area that had nurtured it. As noted earlier, there is a rich diversity in syncretic religious content of the Seven Sisters Festival within the Canton region. Hence, it should be kept in mind that the nuanced religious beliefs and practices of these Cantonese women vary and are not limited to those covered in this article, which serves to provide an overview.

5. Milky Way Associations

5.1. Membership and Leadership

In a foreign land away from home, the early Chinese migrants formed different types of liturgical associations or Hui (会) for communal solidarity and celebrated festivals in honor of patron saints, bringing together people with kinship familial ties or those who shared the same territorial place of origin (Yen 1986, p. 15; Wang 2000, p. 57).15 Similar to temples, these associations were often founded on an incense burner, a symbolic representation that is kept in the possession of the association leader who is known as the Lu Zhu (炉主; “master of the incense burner”) (Feuchtwang 2010, pp. 77–78).

It was popular amongst Cantonese wedded women to form congregations such as Goddess of Mercy associations (Gun Yam Wui 观音会), Goddess of the Sea associations (Noeng Maa Wui 娘妈会), and Tua Pek Kong associations (Daai Baak Gung Wui 大伯公会). Unwed Cantonese women formed their own sororities to celebrate the Seven Sisters Festival. These were termed Milky Way associations (Ngan Ho Wui 银河会), also known as Seven Sisters associations (Cat Ze Wui 七姐会), beseeching skills associations (Hat Haau Wui 乞巧会), or magpie bridge associations (Coek Kiu Wui 鹊桥会). In the late 1930s, there were over 100 Milky Way associations, mostly congregated in the Cantonese-populated Ngau Ce Seoi area within Big Town (Appendix A).

While a number of Milky Way associations were tied to familial kinship (such as those organized by clan associations), a large majority of these were by women who reorganized themselves based on their occupation (e.g., rubber factory female workers) or place of residence (e.g., living in the same coolie quarters) to form voluntary associations that could be cross-clan and even cross-dialect outside of the patriarchal familial system.16 Most of these Milky Way associations did not even have a name and were generally identified only by the address where the celebrations were held, which suggests blurred distinctions amongst the associations in a shared religious orientation.

Membership at Milky Way associations was usually via personal introductions by existing members to the association leader. Association size varied, from smaller ones with over twenty members to larger ones with hundreds of members. In the late 1940s, as little as 1.50 Malayan dollars per month for a year entitled a member to a midnight supper and offerings distributed at the end of the festival, such as a slice of roast pork, some fruits, and pastries; contributions to larger-scale associations cost more, at around 3 to 4 Malayan dollars per month, but included a dinner banquet held on the next evening as well as many more unannounced perks, which allowed members to “more than recoup on their investment” (Si 2002). For instance, if any member had their wishes granted by the Seven Sisters (e.g., strike lottery, good business), it would be customary for the lucky member to give thanks by sponsoring a whole roast pig as an offering at the following year’s festivities. This meant each member would get a larger piece of meat. Membership in such associations was generally exclusive and each association had a cap on their membership size. Sisterhoods forged from such mass religious activities not only created opportunities for the women to socialize, but also provided networks for mutual help and support.17 As such, many unwed women vied for such memberships, and few would leave the sorority.

According to custom, only unwed women could participate in Milky Way associations. If a member were to marry, she would have to perform ceremonial rituals to bid farewell to the celestials and the sorority in the first year of her marriage. As this would be her very last time participating in the festival, she would celebrate it with much splendor and treat her “sisters” to a banquet in order not to “lose face” (J.-t. Hong 1950). Offerings for the farewell ritual included confinement foods such as dyed red eggs and pickled ginger, in hopes of bearing children. Amongst the gifts would also be pears (Lei 梨), which is a pun on the word “separation” (Lei 离). In later years, however, some continued to participate in Milky Way association activities even after they were married (W. M. Lee 2000).

The leader of the association, also referred to as Wui Tau (会头), was “elected” annually at the festival via the ritual of throwing two crescent-shaped wooden divination blocks (Gaau Bui 筊杯), often initiated by a Cantonese Naam Mo priest. A series of successful yin and yang outcomes (e.g., three times in a row, winning a string of ten throws) would make one the newly appointed leader. The leader would then be in charge of collecting monthly fees from members for the following year’s festival.18

5.2. Festival Practices, Rituals, and Games

The annual Seven Sisters Festival was a much-anticipated event many young girls grew up aspiring to attend, having heard about all the excitement and interesting sights associated with it. Every year, there would be a healthy dose of competition amongst the different Milky Way associations to vie for the honor of attracting the largest crowds to their association’s handicraft public showcase. For the months leading up to the festival, members would prepare their handicrafts, usually under a cloud of secrecy to be unveiled in full glory only on the day itself. This often drew curious neighbors, who were excited to see what these women had up their sleeves (Wen 1988). Many of these associations would even have their more experienced members mentor the other women to ensure that they put up a good display (Si 2002). Members received utmost satisfaction when others sang praises of their handicrafts. Some believed that the more compliments received from the public on one’s handicraft skills, the faster one’s wishes would be fulfilled (Qiao 1987).

These women were resourceful and innovative, often using ordinary, everyday items found in their environment to create extraordinary decorative pieces. Intricate pieces meticulously crafted are testimony to their skillfulness and patience. A distinctive display was the pyramidal towers painstakingly decorated by sticking small food items such as dyed glutinous rice and different color beans (such as red bean, green bean, soybean, black bean, and black-eyed peas) onto a paper cone structure.19 Even fish bones were utilized to create miniatures, the size of two fingers, of characters depicted in Chinese classical stories such as Romance of the West Chamber and Zhuge Kong Ming Borrows Arrows (Chia 2000). “Three-inch golden lotus” shoes hand-embroidered with symmetric designs such as “two phoenixes facing the sun” are also a demonstration of their craftsmanship (S. S. Lee 1990).

An important festival paraphernalia was the Seven Sisters Basin, which would be hung up near the entrance of the Milky Way association premises. It is constructed using bamboo strips weaved into a round shape and then painstakingly decorated with paper designs of accessories and vanity items such as scissors, needles, threads, cloth, mirrors, combs, whisks, bangles, flutes, and cosmetics. In any case, the items had to be in sets of seven, dedicated to each of the Seven Sisters. Sometimes, this circular basin would be decorated using actual items instead of paper substitutes. Small basins are around 20 to 30 cm in diameter and large ones can be as wide as 2.4 m (Mo 1995). With so many Milky Way association open houses in Ngau Ce Seoi, visitors tended to use the size of the Seven Sisters Basin as a deciding factor for whether it would be worth squeezing through the crowd to view a particular association’s display (Si 2002).

Another key offering that would be hung up was the different colored robes for the Seven Sisters as well as black robes for the Cowherd topped with a hat made from bamboo leaves, a pair of boots, and a bamboo whip for chasing cattle. These robes could be made from paper, or at some Milky Way associations, from silk with embroideries that took the members months to collectively create (Ci 1987; Qiao 1987).

From the first to the seventh day of the seventh lunar month, some members would abstain from meat and go vegetarian to purify themselves for the festival.20 On the sixth day of the seventh lunar month, members would gather early at the Milky Way associations for the final preparations. Tables would be filled with exquisite handicrafts made by members and offerings including vegetarian sundries, fruits, cosmetics, grain seedlings bundled with a strip of red paper, as well as three-colored pastries stacked into a mountain-shape. As early as 5.30 p.m., members would start burning joss paper and ingots to welcome the heavenly contingent as the celestials descend to inaugurate the festival celebrations (Ci 1987).

At the Zi hour21, a Cantonese Naam Mo priest would be engaged to lead the congregation in the prayers. The mass rituals involved paying respects to the divine stars (Li Dou 礼斗) to ask for peace, harmony, and good luck. The priest would also chant scriptures, which narrate the legend of the Cowherd and the Weaver Fairy, about how the Weaver Fairy was the youngest of the seven fairies, how they attained immortality, how the Weaver Fairy married the Cowherd, and how the couple could meet only once a year.22 Following this, the Cantonese Naam Mo priest would recite the individual names of the members to inform the celestials of their contributions to the heavenly feast that evening.23

Members would then stay over at the association for supper and chat through the night. Children visiting the associations could also enjoy the delicacies prepared. A frequently mentioned specialty of the Milky Way association members was the dessert soup cooked with seven ingredients, including red bean, adzuki bean, glass noodles, and dried bean curd skin (Wen 1988; Qiao 1987).

Members would also engage in various games to read into their future.24 A popular game was taking turns to peer into a basin of water placed on the altar. It is said that only those who were fated or with a good heart could see the Weaver Fairy descend to earth from the reflections of the water (Wen 1988). W. C. Lee (2001), a Milky Way association member in the 1950s, was one such “fated” person who claimed to have seen the Weaver Fairy. Before “viewing”, one must wash one’s hands, clean one’s face, and rub one’s eyes using water steeped with fresh flowers and pomelo leaves. After praying seven times, she stared into the water basin and saw a very beautiful fairy in white robes, with a headdress and flowy silk, holding fresh flowers and smiling at her. “I asked those beside me to have a look too, but they could not [see the Weaver Fairy], and commented how come I was so lucky”, recounted Lee, who was then around 16 years old.

Another custom practiced in Singapore, dating back to the Ming dynasty, was dropping a needle into a bowl of water and watching the reflections form.25 This would predict if one would be blessed with the handicraft skills of the Weaver Fairy. Many also read them as omens of good or evil. If the reflections took forms such as a leaf or flower, it was taken as an auspicious sign or an indication of one’s proficiency in needlework. If the reflections took forms such as beasts or scissors, it was interpreted as an unlucky sign or incompetency (TSFPMA 1937; J.-t. Hong 1950).

The climax at many Milky Way associations was the needle threading competition. Members would have a needle in hand and compete to be the fastest in passing colorful threads through the eye of the needle (Wen 1988). In preparation for this very occasion, the “sisters” would even create needle holders by wrapping either banana leaves or one end of the taro with colored paper and sticking seven needles onto them (Sha 1983). Those who successfully perform this needle threading custom are believed to have received blessings from the Weaver Fairy for proficiency in needlework (TST 1935).

Women may even invite the Weaver Fairy to descend to foretell the future or to seek guidance from. One form was via planchette writing (Fu Ji 扶乩)26, which was reported in TSFPMA (1933): “The ceremony takes place before an altar. The question is written down on a piece of paper which is burnt at the altar apparently before anyone could gather knowledge of its contents, and the answer from the god is forthwith traced on a tray of sand word by word by two girls, supposedly to be ignorant of the question, who hold the ends of a v-shaped instrument from the point of which a little wooden pencil projects at right angles”.

Past 1 a.m., the festival paraphernalia such as the Seven Sisters Basin and robes would be carefully placed into a large metal trunk and set ablaze as the celestials departed (Ci 1987; Qiao 1987).

At dawn, members would start searching under the air well or around the wall corners for the “Seven Sisters powder” (七姐粉) (Feng 1975; Si 2002). It is believed that on the eve of the seventh day of the seventh lunar month, there would be white powder as large as grains falling from heaven, and whoever successfully found them would be blessed with good luck. The powder found could also be applied on the face for good complexion.

In the morning, offerings such as roast pork, fruits, and pastries would be packed in bags labelled with numbers for members to collect, based on the number they drew.27 The members would then return home and reconvene that evening for a banquet at a restaurant or eatery (Aw 1987).

6. Cantonese Women as Active Agents

For the remainder of the article, I delve into case studies that highlight the coexistence of different belief systems, shifts in interest from China as the center of sociocultural origin to post-war/post-independence Singapore in the periphery, and negotiations with space to show how Cantonese women of Milky Way associations were active agents in reorganizing themselves, interacting with other communities, and engaging in heritage meaning-making.

6.1. Coexistence of Different Belief Systems

Majies (妈姐 “mother-sister”), many of whom took up work in Singapore as domestic helpers to look after their employer’s children, came mainly from Shunde and the surrounding regions (K. L. Lee 2015). They took the vow of celibacy that involved a ceremonial ritual known as Sor Hei (梳起 “combing up”) in which their hair would be styled into a neat bun as an expression of their social maturity. Majies are hence “self-combed women” (自梳女), influenced by long-withstanding marriage resistance practices in their hometown (Topley 1975).

The annual Seven Sisters Festival was the most important celebration for Majies in general (Ye 1994).28 They would specifically take leave from their employers, wear new clothes, and stay over at the Milky Way associations in the company of their Gam Laan sworn sisters (金兰姐妹 “Golden Orchid Sisters”) (Si 2002). In addition to customary rituals, they would also catch up and exchange greetings with one another as though it were the lunar new year (Jun 2002). Sometimes, the Majies even bought gold, which would be placed on the altar that evening and later gifted to their goddaughters or other Majies as a form of blessing (Chay 2013).

Despite Majies’ marriage-resisting status, they would nonetheless, in their role as loyal servants, partake in rituals to pray for a blissful marriage on behalf of their little employers during the Seven Sisters Festival. Offering items full of symbolisms related to bearing offspring would be used. This included a stack of pastries each shaped like a Chinese chess piece (Kei Zi 棋子), which is a Cantonese pun on the desire to “beseech for sons” (Kei Zi 祈子). Vivienne Tan, who grew up in the big Wong Ah Fook household where each child was attended to by a Majie, recounted: “I remember my Majie saying to me [during the Seven Sisters Festival] that she would pray for a good husband for me”. True enough, she is now blissfully married to Professor Walter Tan, fifth generation descendent of the esteemed philanthropist Tan Kim Seng.29

Due to the significance of the Seven Sisters Festival for the Majies, they were often key drivers in larger-scale Milky Way associations, such as those organized at clan associations, vegetarian halls30, and even entertainment houses. At the latter, Pipa Tsais (high-class courtesans who played the pipa or the pear-shaped Chinese wooden lute to entertain men) had deep pockets and were willing to splurge on hiring a personal Majie to attend to them. They usually left it to the Majies to put up lavish displays and large praying altars in the Keong Saik red-light district area as an outward demonstration of the Pipa Tsais’ popularity and economic power (Aw 1987). Some showcased exquisite gold utensils such as wine cups, teacups, bowls, and chopsticks, while others decorated the Seven Sisters basin with precious jade bracelets (Si 2002). Although Majies’ personal beliefs of purity and chastity run counter to their employers’ nature of work, such arrangements paradoxically afforded the extravagant celebrations and offerings for their worship of the Seven Sisters.

6.2. Shift in Social Interests

Although overseas, the women kept in touch with their families and the latest happenings in China.31 As atrocities during the Sino-Japanese War escalated, Chinese from all walks of life responded fervently to appeals to rescue China. On 15 August 1937, the Singapore China Relief Fund Association, led by Tan Kah Kee, was set up with a thirty-two-member committee represented by the various Chinese dialect groups in Singapore (Leong 1979). Weighing in their role as a daughter with familial ties in China and as a sister in their Milky Way association sorority, Cantonese women from over a hundred Milky Way associations in Singapore reconceptualized the Seven Sisters Festival by cutting back on their celebrations and leveraging the festival for fundraising efforts. No amount was considered too small: donations of even one or two dollars, which constituted a few days of wages (Table 2), were worthy of mention in the newspapers.

Table 2.

Average labor wages of Chinese laborers per day in Singapore in 1938.

Based on a conservative estimate gathered from various known newspaper sources, the Milky Way associations raised over 5642.69 Straits dollars and 564.29 Chinese currency from 1938 to 1941 (Table 3). Most of these associations were in the Ngau Ce Seoi area within Big Town. Despite their sheer numbers, the size of their contributions could not hold a candle to that of the few Milky Way associations in another Cantonese enclave in Singapore—the Sai Bak Mun area. Notably, three Milky Way associations from Sai Bak Mun area collectively contributed the lion’s share of the funds raised: over 2000 Straits dollars in 1938, 1100 Straits dollars in 1939, 700 Straits dollars in 1940, and 900 Straits dollars in 1941 (NSPP 1938g, 1939c, 1940a, 1941b).

Table 3.

Conservative estimate of contributions raised by Milky Way associations in Singapore, 1938–1941.

Sai Bak Mun (西北门 “Northwest Gate”) is the colloquial name referring to the area around what used to be Keppel Harbor gate number 9 (present day Harbourfront). Large numbers of Singapore Harbor Board male workers and supervisors (nicknamed “number one”) worked in the vicinity of gate nine, northwest of the sixteen blocks of workers’ quarters where many of them lived with their families.32 As ship repairing required specialized skills such as grinding and welding, the Cantonese who performed mechanical or engineering work had more stable jobs compared to other lower-skilled workers (Aw 1996). In the late 1930s, Cantonese mechanics formed a huge portion of the over 1800 Chinese employees working there.33 Hence, with both strong financial backing and the ability to mobilize resources, women in the Sai Bak Mun area were able to collectively organize large-scale Milky Way association celebrations.

Three Milky Way associations at Sai Bak Mun came together to run a huge fundraiser for the China Relief Fund (NSPP 1938e). The usual celebrations with four days of Cantonese opera performances held on the sixth, seventh, eighth, and ninth days of the seventh lunar month were cut down to two days, and the savings were donated. One of the key leaders who proposed organizing this fundraiser was Wat Fung Ngo 屈凤娥, also known as “Sister Ngo 娥姐”. In addition to being a sponsor, the fifty-something “Sister Ngo” also personally went around to supervise all aspects of the fundraising (NSPP 1940c).

It was not only the Sai Bak Mun Milky Way association members who were mobilized: businesses and hawkers set up stalls at the charity bazaar, the “Fragrant Chrysanthemum Sisters” (菊芳姐妹团; an informal group formed by Pipa Tsais and Ah Kus who went around to help with fundraising efforts)34 beautifully dressed in white with an embroidered yellow chrysanthemum solicited festivalgoers at the entrance to make donations for fresh flower collar pins, and even children living in the Sai Bak Mun area sold soft-drinks to raise funds. Cantonese representatives from the China Relief Fund also presented rousing speeches, appealing to audiences to open their hearts and wallets. This community effort successfully drew crowds of families to soak in the lively atmosphere while generously supporting the relief of distressed Chinese in the war (NSPP 1938e). A total of over 2000 Straits dollars was donated, of which more than 740 Straits dollars was raised from the two-day carnival and the remaining amount from cost savings by cutting back on the celebrations (NSPP 1938g).

Over the years, possibly through increased interaction and ties with the other Chinese dialect groups, the causes supported by the Milky Way associations in Singapore continued to evolve and diversify, including those that targeted other non-Cantonese communities. For instance, in response to severe flooding in the Guangdong and Fujian provinces (华南水灾) in 1947, the Milky Way association at Sai Bak Mun collaborated with Xinghua Music and Drama association (星华音乐剧社), as well as the women’s group from Qiao Sheng Club (侨声俱乐部妇女组), to put up a two-day Cantonese opera fundraiser (NSPP 1947).

As increasing numbers of Cantonese women migrants settled down and a new generation of Cantonese women born in Singapore joined Milky Way associations, there was a shift in interests from China as the center of sociocultural origin to post-war/post-independence Singapore in the periphery and many started looking at how they could contribute locally. For example, in 1950, the organizers of a Milky Way association on Keong Saik Road, Li Yue Zhen 李月珍 and Yuan Hui Xia 袁惠霞, each donated 100 Malayan dollars to help the sick at the Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital and rallied the others to contribute as well (J.-t. Hong 1950). In 1956, the Milky Way association on 24 Banda Street (万拿街24号钟盛七姐会) was reported to have cut back on their festival spending for that year and donated 240 Malayan dollars in cost savings to the Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital (SCJP 1956). On a larger scale, the Milky Way association at Keppel Shipyard (岌巴船坞部七姐牛郎联合会庆祝银河会), which “aimed to promote doing good as the greatest source of happiness”, held a ten-day fundraiser for the Singapore Chung Hwa Medical Institution (中华留医院基金) from the third to the twelfth day of the seventh lunar month in 1972 (NSPP 1972). With a strong line-up of popular Cantonese opera troupes from Singapore and Hong Kong, they raised a total of 5101.70 Singapore dollars—a sum that ranked the Keppel Shipyard Milky Way association as one of the top donors alongside other Zhong Yuan Festival associations that were also fundraising for the medical institution during the seventh lunar month (NSPP 1972; SCJP 1972).

6.3. Negotiations with Space

Unlike in regions of Canton where women had entire girls’ houses and large courtyards to hold the Qixi Festival celebrations, the Milky Way associations had to negotiate with overcrowded and tight living spaces in early Singapore. Through their ingenuity and resourcefulness, the Milky Way associations transformed everyday common or informal venues into sacred spaces, enlivening almost every street and lane in Ngau Ce Seoi with dazzling handicraft displays, which attracted throngs of curious visitors throughout the night. One such space was the coolie quarter. As recounted by S. S. Lee (1990):

Everyone in the coolie quarters would be involved in the mass worship of the Seven Sisters. The women would even use the coolie quarters as an exhibition area to showcase their handicrafts for the public to see. Their hand-embroidered pieces of flowers and little animals were all very realistic!

These coolie quarters were not usually open to the public. Only on the seventh day would you be allowed to enter these quarters for prayers and visit the exhibition. The women had a lot of display items which were visible even from the ground floor. If the [ground floor] was decorated with fresh flowers, it meant that there was more to see upstairs.

If there was an exhibition in the coolie quarters that night, the beds would be packed away. Each bed was basically a straw mat laid onto a plank of wood. Most of the time, they would have their own storage box for clothes; this box would be placed under the bed. Usually, the beds would be partitioned with a piece of cloth such that “you cannot see me, and I cannot see you”.

At times, physical constraints forced Milky Way associations to coexist harmoniously alongside very disparate communities.

An example is the infamous Keong Saik area, which was not just a red-light district, but also a place of residence for the ordinary folk. To differentiate from the Milky Way associations organized by the entertainment hostesses who lived in the area, the Milky Way associations ran by the common folk would hold their celebrations in back alleys instead of on the main street (Liang 1978).

Another interesting example is Sago Lane, which was nicknamed “Street of the Dead” due the common sight of coffins and corpses outside the funeral parlors situated there. According to Woo (2000), there were at least two Milky Way associations on Sago Lane, creating an interesting juxtaposition of events: “On one side of the Street of the Dead, there were funeral parlors holding wakes, and on the other side were the festivities of the Milky Way Associations. Each minded their own business with no conflict arising between the two. We girls happily roamed, feasting our eyes and commenting on the displays exhibited”.

7. Conclusions

Following the lead of scant scholarship that investigated the intersection of Chinese religion and women and their developments after migration to Southeast Asia (Topley 1954, 1955, 1956; Show 2018), this article contributes to the field by bringing to the fore the Seven Sisters Festival in Singapore, its religious practices, and the over 100 Milky Way associations (listed in Appendix A) organized by Cantonese women for the mass festival celebrations.

In piecing the fragmented social and religious history of an ephemeral festival, which left little material trace and has faded from public consciousness since the 1970s, I employed a combination of documentary and ethnographic field research methods including conducting in-depth oral history interviews with diverse stakeholders, from a Cantonese Naam Mo priest who provided such specialized religious rituals to former Milky Way association members to suppliers of related paraphernalia. This allowed me to achieve the three objectives set out in this paper.

First, this article sheds light on previous research that noted contradictions in the religious beliefs and practices reported by oral history interviewees (Tan 2018, p. 23) through historical inquiry on divergences in syncretic religious content within the Canton region. Particularly, I show that while sisterhoods of unwed Cantonese women featured centrally in the Seven Sisters Festival, for Canton regions with marriage-resistance practices, the festival was further reconceptualized as one that exhorts notions of purity, chastity, and gender equality. For instance, “self-combed women” who swore to celibacy would pray to the Seven Sisters for the strength to resist temptations from men whereas newlywed Cantonese women (from regions that do not practice marriage resistance) leaving the sorority would make offerings that included confinement foods in hopes of bearing children.

Second, I argued that the phenomenon of Cantonese ritualistic prominence during the Seven Sisters Festival, despite the Cantonese population being outnumbered by the Hokkiens and Teochews, was contributed by two main factors. For one, the Cantonese women migrants constituted a large, sizeable population in Singapore, which increased drastically in the 1930s. Next, while Hokkien and Teochew families celebrated the festival in private within individual households, Cantonese women formed sororities that organized large-scale celebrations open to the public to visit.

Third, I detailed how Cantonese women reconfigured their basic structure of the sisterhood and adapted their religious practices outside of the original culture area that had nurtured it. Notably, although a number of Milky Way associations were organized based on familial kinship ties, a large majority of these were reorganized based on occupation (e.g., rubber factory female workers) or place of residence (e.g., living in the same coolie quarters) hence forming voluntary associations, which included members from other communities beyond their clan or dialect group. Through case studies on the coexistence of different belief systems, shift in interests from China as the center of sociocultural origin to post-war/post-independence Singapore in the periphery, and negotiations with space, I demonstrated that Cantonese women were active agents who reorganized themselves, interacted with other communities, and engaged in heritage meaning-making.

In this article, I focused the discussion on the religious historical developments of the Seven Sisters Festival brought over by the huge wave of Cantonese women migrating from China to Singapore, especially during the 1930s. Future research could expand the time period under study to examine the multitude of political, economic, and sociocultural factors leading to the disappearance of this once-significant Seven Sisters Festival in the 1970s. Of particular interest would be to investigate the continuity and adaptation of Seven Sisters religious practices and beliefs, albeit at a much smaller scale and generally in private spaces, by scattered individuals and organizations in Singapore. Trajectories of the Seven Sisters Festival in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, and other Southeast Asian countries including Malaysia, Vietnam, and Thailand, which are beyond the scope of this article, could also be explored for an in-depth comparative analysis.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Heritage Board (Singapore) grant number NHB/HPG/19113M47.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all interviewees to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| NSPP | Nanyang Siang Pau Press |

| SCJP | Sin Chew Jit Poh |

| TKSSDN | The Kung Sheung Daily News |

| TSFP | The Singapore Free Press |

| TSFPMA | The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser |

| TST | The Straits Times |

Appendix A

The following non-exhaustive list of Milky Way associations in Singapore was compiled by the author from newspaper articles reporting their fundraising efforts towards the China Relief Fund (NSPP 1938a, 1938b, 1938c, 1938d, 1938f, 1938g, 1938h, 1939a, 1939b, 1939c, 1939d, 1940a, 1940b, 1941a, 1941b; SCJP 1939).

Table A1.

Non-exhaustive list of addresses and contributions by Milky Way associations in Singapore for the China Relief Fund, 1938–1941. Asterix (*) and question mark (?) in the list indicates that the street is now defunct and that information is missing from newspaper sources, respectively.

Table A1.

Non-exhaustive list of addresses and contributions by Milky Way associations in Singapore for the China Relief Fund, 1938–1941. Asterix (*) and question mark (?) in the list indicates that the street is now defunct and that information is missing from newspaper sources, respectively.

| S/N | Area | 银河会地址 | Address of Milky Way Association | Contribution Straits Dollars/ Chinese Currency (SD/CC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Big Town | 安祥禧35号楼下七姊会 | 35 Ann Siang Hill, Ground floor | SD10 |

| 2 | Big Town | 大坡万拿街1号二楼 | 1 Banda Street, 2nd floor | SD3 |

| 3 | Big Town | 万拿街15号楼下佩金七姐会 | 15 Banda Street, Ground floor | SD5 |

| 4 | Big Town | 万拿街27号楼下合心堂 | 27 Banda Street, Ground floor | SD8 |

| 5 | Big Town | 万拿街29号楼下 | 29 Banda Street, Ground floor | SD5 |

| 6 | Big Town | 大坡万拿街30号广 _ 安乐庆堂姊妹七姐会 | 30 Banda Street | SD23.40 |

| 7 | Big Town | 万拿街59号二楼3号房七姐会 | 59 Banda Street, 2nd floor, No. 3 | SD3 |

| 8 | Big Town | 广东街51号金玉庆堂七姐会 | 51 Canton Street | SD14 |

| 9 | Big Town | 大门楼2号广顺利二楼七姐诞会 | 2 Club Street, 2nd floor | SD2 |

| 10 | Big Town | 大门楼21号楼下 | 21 Club Street, Ground floor | SD5 |

| 11 | Big Town | 大坡大门楼35号三楼 | 35 Club Street, 3rd floor | SD50 |

| 12 | Big Town | 大门楼56号江玉琼七姐会 | 56 Club Street | SD3 |

| 13 | Big Town | 乞纳街58号联庆堂七姐会 | 58 Club Street | SD2 |

| 14 | Big Town | 大门楼93号何带七姐会 | 93 Club Street | SD3 |

| 15 | Big Town | 丹戎巴加当店巷9号三下 | (Tanjong Pagar) 9 Craig Road | SD2 |

| 16 | Big Town | 吉宁街23号楼下七姐会 | 23 Cross Street, Ground floor | SD10 |

| 17 | Big Town | 车仔街22号三楼小姊会 | 22 Duxton Road, 3rd floor | SD3 |

| 18 | Big Town | 车仔横街集 _ 堂 | (?) Duxton Road | SD5 |

| 19 | Big Town | 余东旋街27号三楼七姐会 | 27 Eu Tong Sen Street, 3rd floor | SD5 |

| 20 | Big Town | 余东旋街28号三楼合福堂七姊会 | 28 Eu Tong Sen Street, 3rd floor | SD5 |

| 21 | Big Town | 余东旋街28号二楼七姐会 | 28 Eu Tong Sen Street, 2nd floor | SD3 |

| 22 | Big Town | 余东旋街南昌二楼七姐会 | (?) Eu Tong Sen Street, 2nd floor of Nan Chang | SD30 |

| 23 | Big Town | 香港街11号三楼 | 11 Hong Kong Street, 3rd floor | CC100 and SD3 |

| 24 | Big Town | 恭锡街17号楼下 | 17 Keong Saik Road, Ground floor | SD3 |

| 25 | Big Town | 恭锡街39号楼下广永七姐会 | 39 Keong Saik Road, Ground floor | SD10 |

| 26 | Big Town | 恭锡街47号楼下姊妹会 | 47 Keong Saik Road, Ground floor | CC50 and SD17.50 |

| 27 | Big Town | 恭锡街若泉街10号 | 10 Keong Saik Rd/Jiak Chuan Rd | SD12 |

| 28 | Big Town | 水车街27号美容 | 27 Kreta Ayer Road | SD3 |

| 29 | Big Town | 水车街27号二楼七姐会 | 27 Kreta Ayer Road, 2nd floor | SD12 |

| 30 | Big Town | 水车街30号二楼头房容珍七姐会 | 30 Kreta Ayer Road, 2nd floor | SD5 |

| 31 | Big Town | 水车街36号二楼联友堂七姐会 | 36 Kreta Ayer Road, 2nd floor | CC100 and SD42.50 |

| 32 | Big Town | 水车街39号七夕会 | 39 Kreta Ayer Road, 2nd floor | SD3 |

| 33 | Big Town | 水车街43号二楼北山七姐会 | 43 Kreta Ayer Road, 2nd floor | SD5 |

| 34 | Big Town | 水车街43号三楼七姐会 | 43 Kreta Ayer Road, 3rd floor | SD3 |

| 35 | Big Town | 水车街257号二楼七姐会 | 257 Kreta Ayer Road | SD12 |

| 36 | Big Town | 马来克街48号楼上七姐会 | 48 Malacca Street (?) | SD5 |

| 37 | Big Town | 牛角街19号7号房 _ _ 亚子七姐会 | 19 Mohammad Ali Lane | SD5 |

| 38 | Big Town | 摩士街17号二楼七姐诞会 | 17 Mosque Street, 2nd floor | SD10 |

| 39 | Big Town | 尼律黎乙街11号丽昇二楼七姐会 | 11 Neil Road, 2nd floor | SD32 |

| 40 | Big Town | 尼律26号七姊会 | 26 Neil Road | SD5 |

| 41 | Big Town | 尼律勤记45号二楼 | 45 Neil Road, 2nd floor | SD5 |

| 42 | Big Town | 尼律58号存福七姊姊妹会 | 58 Neil Road | SD6 |

| 43 | Big Town | 尼律80号 | 80 Neil Road | SD10 |

| 44 | Big Town | 呢律121号合义堂七姐会 | 121 Neil Road | SD3 |

| 45 | Big Town | 二马路湖山_室 | (?) New Bridge Road | Placed donation box |

| 46 | Big Town | 二马路195号楼下义合堂七姐会 | 195 New Bridge Road, Ground floor | SD2 |

| 47 | Big Town | 二马路197号三楼合胜堂七姐会 | 197 New Bridge Road, 3rd floor | SD10 |

| 48 | Big Town | 二马路263号 | 263 New Bridge Road | Placed donation box |

| 49 | Big Town | 纽马吉律(?)号得光堂七姐会 | (?) New Market Road | SD3 |

| 50 | Big Town | 纽马吉律149号七姐会 | 149 New Market Road | SD3 |

| 51 | Big Town | 纽吗吉律183号阿三七姐会 | 183 New Market Road | SD5 |

| 52 | Big Town | 广合源街71号三楼七姐会 | 71 Pagoda Street, 3rd floor | SD5 |

| 53 | Big Town | 广合源街74号长春酒莊二楼 | 74 Pagoda Street, 2nd floor | SD20 |

| 54 | Big Town | 广合源街75号二楼头房冰姐七姐会 | 75 Pagoda Street, 2nd floor | SD3 |

| 55 | Big Town | 广合源街79号二楼七姐会 | 79 Pagoda Street, 2nd floor | SD3 |

| 56 | Big Town | 沙古连街36号三楼七姐会 | 36 Sago Lane (?), 3rd floor | SD3 |

| 57 | Big Town | 沙古连街37号宝树七姐会 | 37 Sago Lane (?) | SD5 and placed donation box |

| 58 | Big Town | 沙古连街43号三楼七姐会 | 43 Sago Lane (?), 3rd floor | SD2 |

| 59 | Big Town | 庙仔街7号三楼广有发七姊会 | 7 Sago Street, 3rd floor | SD1 |

| 60 | Big Town | 庙仔街51号广林发二楼王惠莲七姐会 | 51 Sago Street, 2nd floor | SD4 |

| 61 | Big Town | 庙仔街51号三楼广合兴七姐会 | 51 Sago Street, 3rd floor | SD13 |

| 62 | Big Town | 庙仔街55号宝兴七姊会 | 55 Sago Street | SD1 |

| 63 | Big Town | 庙仔街58号大明星七姊会 | 58 Sago Street | SD3 |

| 64 | Big Town | 庙仔街72号二楼润记七姊诞会 | 72 Sago Street, 2nd floor | SD4 |

| 65 | Big Town | 庙仔街76号二楼七姐会 | 76 Sago Street, 2nd floor | SD2 |

| 66 | Big Town | 戏院街19号维德学校学生七姐会 | 19 Smith Street, Student Group | SD5 |

| 67 | Big Town | 戏院街33号二楼冠英学校 | 33 Smith Street, 2nd floor, school | SD8 |

| 68 | Big Town | 戏院街54号楼下七姐会 | 54 Smith Street, Ground floor | Placed donation box |

| 69 | Big Town | 戏院街66号楼下七姐会 | 66 Smith Street, Ground floor | SD3 |

| 70 | Big Town | 戏院街李庆成堂七姊会 | (?) Smith Street | SD4 |

| 71 | Big Town | 大马路29号二楼七姐诞会 | 29 South Bridge Road, 2nd floor | SD1 |

| 72 | Big Town | 大马路282号二楼胜意堂 | 282 South Bridge Road, 2nd floor | SD3 |

| 73 | Big Town | 番寨尾陈_和二楼七姐会 | (?) Spring Street, 2nd floor | SD5 |

| 74 | Big Town | 番寨尾29号七姐会 | 29 Spring Street | SD3 |

| 75 | Big Town | 番寨尾34号元楼七姊会 | 34 Spring Street | SD5 |

| 76 | Big Town | 番寨尾45号楼下七姐会 | 45 Spring Street, Ground floor | SD2 |

| 77 | Big Town | 番寨尾47号周金大七夕 | 47 Spring Street | SD19.09 |

| 78 | Big Town | 番寨尾88号阿金坚七姊会 | 88 Spring Street | SD2 |

| 79 | Big Town | 丹戎巴加1号 _ 昌乞巧会 | 1 Tanjong Pagar Road | CC100 |

| 80 | Big Town | 丹戎巴加4号楼下广成七姐会 | 4 Tanjong Pagar Road, Ground floor | SD15 |

| 81 | Big Town | 丹戎巴加93号 南中二楼 | 93 Tanjong Pagar Road, 2nd floor | SD2 |

| 82 | Big Town | 源顺街105号楼下七姐会 | 105 Telok Ayer Street, Ground floor | SD8 |

| 83 | Big Town | 元顺街秋记105号七夕 | 105 Telok Ayer Street, Qiu Ji | SD5 |

| 84 | Big Town | 戏院后街7号二楼七姐会 | 7 Temple Street, 2nd floor | SD12 and placed donation box |

| 85 | Big Town | 登婆街24号 | 24 Temple Street | Placed donation box |

| 86 | Big Town | 戏院后街36号何锐记(?) | 36 Temple Street | Unknown |

| 87 | Big Town | 戏院后街42号联益楼下小姐会 | 42 Temple Street, Ground floor | SD3 |

| 88 | Big Town | 戏院后街54号楼下七姐会 | 54 Temple Street, Ground floor | SD10 |

| 89 | Big Town | 登婆街忠记七姊会 | (?) Temple Street | SD3 |

| 90 | Big Town | 丁加奴街2号楼下顺利堂七姐会 | 2 Terengganu Street | SD15 |

| 91 | Big Town | 戏院横街24号二楼李氏七姐会 | 24 Trengganu Street, 2nd floor | SD6 |

| 92 | Big Town | 道拉实街132号楼下 | 132 Tras Street, Ground floor | SD5 |

| 93 | Big Town | * 豆腐街正昌二楼七姐会 | * (?) Upper Chin Chew Street, 2nd floor | SD1 |

| 94 | Big Town | * 豆腐街27号地下七姐会 | * 27 Upper Chin Chew Street, Basement | SD3 |

| 95 | Big Town | * 豆腐街35号二楼七姊会 | * 35 Upper Chin Chew Street, 2nd floor | SD5 |

| 96 | Big Town | * 豆腐街55号楼下 | * 55 Upper Chin Chew Street | SD3 |

| 97 | Big Town | * 豆腐街56号二楼七姐会 | * 56 Upper Chin Chew Street, 2nd floor | SD5 |

| 98 | Big Town | * 豆腐街60号_利七姐会 | * 60 Upper Chin Chew Street | SD10 |

| 99 | Big Town | * 豆腐街62号七姐会 | * 62 Upper Chin Chew Street | SD5 |

| 100 | Big Town | 海山街尾64号七姐会 | 64 Upper Cross Street | CC114.29 |

| 101 | Big Town | 海山街64号四楼七姊会 | 64 Upper Cross Street, 4th floor | SD40 |

| 102 | Big Town | 海山街72号 | 72 Upper Cross Street | Placed donation box |

| 103 | Big Town | 海山街尾90号日南二楼 | 90 Upper Cross Street, 2nd floor | SD10 |

| 104 | Big Town | * 松柏街洪记七姐会 | * (?) Upper Nankin Street | SD2 |

| 105 | Big Town | * 松柏街60号杨展记七姊会 | * 60 Upper Nankin Street | SD2 |

| 106 | Big Town | 大坡单边街32号吉庆堂 | 32 Upper Pickering Street | CC50 |

| 107 | Big Town | 大坡七姊会卢秀莲等 | (?) | SD10 |

| 108 | Small Town | 小坡十六间60号会_ 堂七姊会 | (?) | SD10 |

| 109 | Small Town | 小坡克街60号梁三姑七姐会 | (?) | SD10 |

| 110 | Small Town | * 福南街30号二楼女子七姐会 | * 30 Hock Lam Street, 2nd floor | SD10 |

| 111 | Sai Bak Mun | 西北门七姐会 (甲乙丙) | Northwest Gate (Note: 3 Milky Way Associations combined) | SD4700 |

| 112 | Others | 丹戎巴加船厂4号广胜 髹漆厂七姐会 | Tanjong Pagar Dock | CC50 |

| 113 | Others | 专利局 | (?) | SD40.50 |

| 114 | Others | 石龙岡街349号楼下七姐会 | 349 Serangoon Road, Ground floor | SD4 |

| 115 | Others | 丹戎禺旧厂七姐会 | Tanjong Rhu | SD50 |

| 116 | Others | 丹戎禺新厂七姐会 | Tanjong Rhu | SD10 |

| 117 | Others | 马利士他196号联胜堂七姐会 | 196 Balestier Road | SD5 |

| 118 | Others | 孖厘士他街490号二楼七姐会 | 490 Balestier Road, 2nd floor | SD5 |

| 119 | Others | 金龙酒楼龙珠厅七姊会 | (?) | SD30 |

| 120 | Others | 沙咀广安七姐会 | (?) | SD10.70 |

| 121 | Others | 火井十字路永南龍七姐会 | (?) Lavender Street | SD4 |

| 122 | Others | 卡温律7号家庭七姐会 | 7 Cavan Road | SD5 |

| 123 | Others | 中保街37号张丽生 | (?) | SD5 |

Notes

| 1 | For a discussion on how “superstitious practices” is gendered in a society moving towards modernity, and the role of women in propagating religious knowledge in their families, see Valussi (2020). |

| 2 | Ethnography and cultural mapping are methods recommended by UNESCO Institute for Statistics (2009) for festival research. |

| 3 | See Shun Tak Kong Mei Sar Khai Wong Clan Association (1959–1976). In the late 1980s, the Milky Way association of this clan was one of the last few remaining that still held the Seven Sisters Festival celebrations (Ci 1987; Qiao 1987). |

| 4 | Beyond China, the Sinicization of Japan as early as in the fifth century, for instance, saw the Qixi Festival evolved into the Tanabata Festival with a fusion of Chinese practices and Japanese indigenous Shintō religious rituals. See Qiu (2017). |

| 5 | For a study on the localization and popularity of the Mahoraga dolls during the Song dynasty, see Fan and Long (2022). |

| 6 | For maps showing areas where marriage resistance was practiced in the Pearl River delta, see Stockard (1989, pp. 10–11). Note that contrary to misconceptions propagated in popular media, marriage resistance was not found in the Samsui region, see Low (2014, p. 78). On a related topic on social perceptions on chastity, also see A. Leung (1993). |

| 7 | For a related folklore on antimarriage sisterhood, which purportedly gave rise to the street name “Tsat Tsz Mui Road 七姊妹道” in Hong Kong, see Dung (2012, pp. 115–17). |

| 8 | Another popular legend in the region related to sisterhood is that of Caam Gu 蚕姑, three sworn sisters who look after the health of silkworms. Legends as such supported the cultural formation of sisterhoods in the Pearl River delta. See Sankar (1978, p. 26). |

| 9 | Authors’ interview with Lan Jie 蓝姐 at the Seven Fairy Temple in Setapak, Malaysia, 5 August 2019. |

| 10 | For a discussion on girls’ houses, see Watson (1994, pp. 38–39). Note that boys in the region had similar bachelor houses where they spend their boyhood until they got married, see Topley (1975, pp. 429–30). For accounts of Cantonese women on their experiences living in girls’ houses before finding work as domestic helpers in Singapore, see I. C. Ho (1958, pp. 46–51). |

| 11 | On the topic of Cantonese “wooden-fish books” and related expressive art forms, also see Yung (1987), P.-C. Leung (1978), and Eberhard (1972). |

| 12 | For a close parallel of women from Chuansha, Shanghai who had economic independence and shared non-Confucian female identities, see Prazniak (1986). |

| 13 | For a distribution of the Chinese population in early Singapore, see Report on the Census of the Straits Settlements, Singapore, 1891. |

| 14 | In the author’s interview with Ng Siam Eng 黄暹英, 71-year-old female of Teochew descent, on 22 April 2019, she fondly remembered gathering fresh flowers as a child in the morning, which would later be placed on the altar set up in her home in Punggol to be offered to the Seven Sisters on the seventh day evening; in the author’s interview on 28 July 2021 with husband and wife duo Teo Bee Kim 张美金 and Lee Chwee Choon 李水春, both Hokkien and born in Singapore in the 1950s, they referred to the Seven Fairies as Seven Mothers 七娘妈. Celebrations took place on the seventh evening with offerings including paper pavilions and sesame oil sticky rice. For Teo, his family’s festival celebrations were considered more lavish with larger portions of food as it was held in the shophouse of their family business and employees would join in for dinner after prayers. |

| 15 | For an in-depth discussion on the different types of liturgical associations and how they organize themselves, see Schipper (1977). |

| 16 | Author’s interview with Chen Meizhi 陈梅枝, 16 May 2019. Of Hokkien Zhao An (福建诏安) descent, she joined a Milky Way association organized at her friend’s place in Aljunied in the late 1960s when she was in her twenties. For her, it was simply an opportunity to have fun hanging out with her ten other female friends, whom she worked with at the steel cable factory and were mostly of Cantonese descent. For a related discussion on women in voluntary associations established along kinship and ancestral hometown clan ties, see L. Y. Wong (2022). |

| 17 | For detailed examples of the various mutual support including the tontine system, afterlife practices, and caring for each other during times of difficulty, see I. C. Ho (1958). |

| 18 | Author’s interview with Fun Kwai-leng 范桂玲, a female of Guangdong Samsui-descent born in Singapore in 1930, in the presence of her grandniece Pauline Fun, 13 August 2021. Also see Boon (1951). |

| 19 | Author’s interview with Richard Lee 李福荣, who was born in 1956, on 30 March 2020. |

| 20 | Author’s interview with 88-year-old Kwang Ah Kui 关亞娇 in the presence of her son Patrick Yee, 18 August 2021. Also see TSFP (1947) and S. M. Lee (1986). |

| 21 | The Chinese time system follows a two-hour subdivision, starting with the Zi hour 子时 from 11 p.m. to 1 a.m. |

| 22 | Author’s interview with Cantonese Naam Mo priest Loke Weng Sun 陆荣新, who was born in 1955, regarding the rituals he conducted during the Seven Sisters Festival in Ngau Ce Seoi, 11 September 2021. |

| 23 | Author’s interview with 87-year-old Tan Ah Ngan 邓亚银, in the presence of her son Lee Kian Cheong, 15 December 2020. Tan had worked in a rubber factory and joined a Milky Way association organized by her colleague’s mother. |

| 24 | Also see a discussion on the folk custom of playing shamanistic games, such as the “descent of the Eight Immortals 降八仙”, under the moonlight in Guangdong, by Shiga (2002). |

| 25 | See Wan shu zaji 宛署杂记 (Records of Wan Ping County). |

| 26 | For an analysis on the practice of automatic writing seances, see Jordan and Overmyer (1986). |

| 27 | Author’s interview with Fun Kwai-leng 范桂玲, 13 August 2021. |

| 28 | There were also Majies who did not celebrate the Seven Sisters Festival. In the author’s interview (with the assistance of Dongguan dialect interpreter Yang Hui Sheng 杨惠聲) with 97-year-old Yong Lai Wah 杨丽华, a Majie from Dongguan who worked in Singapore, she commented that the festival was only for those with the “luxury of time”, and she did not participate in it, 27 May 2018. |

| 29 | Author’s interview with Vivienne Tan 黄佩璧, 3 January 2020. |

| 30 | Vegetarian halls (Zaai Tong 斋堂), communal spaces for members who followed Buddhism-influenced practices such as vegetarianism as well as an esoteric religion known as the Way of Former Heaven 先天道, were also havens for many retired Majies. For comprehensive studies, see Topley (1963) and Show (2018). |

| 31 | It is worth noting that the Milky Way associations in Singapore were unaffected by the suppression of Seven Sisters Festival celebrations in Guangzhou during the rise of the “New Culture” Movement in China. See NSPP (1929) and TKSSDN (1929). |

| 32 | Author’s interview with Norman Kwok, 63 years old, former resident at Blk 3 Morse Road, 15 April 2022. The workers’ quarters, which used to occupy the open carpark and the area where Seah Im Food Centre is today, were demolished in the 1970s. |

| 33 | See Straits Settlements, Blue Book, 1938, section 23, p. 810. |

| 34 | In K. M. Ho (1992), she described her life living on Teck Lim Street and as a popular Pipa Tsai in the 1940s until the post-war period. She is better known by her stage name Yue Xiaoyan 月小燕. She, together with another female partner, started the “Fragrant Chrysanthemum Sisters” and organized the other Pipa Tsais and Ah Kus to help raise funds for different causes. At one point, the group had over 300 members. |

References

Primary Sources

Census of the Straits Settlements (Singapore), 1881.Houchunji 后村集, vol. 12, Jishishishou 即事十首. Liu Kezhuang 刘克庄 (1187–1269). Available online: https://ctext.org/library.pl?if=gb&file=1469&page=90&remap=gb (accessed on 10 May 2021).Qixi zanhua 七夕赞花. Circa 1900–1949. Guangzhou: Yiwentang 以文堂.Report on the Census of the Straits Settlements, Singapore, 1891.Shunde Xianzhi 顺德县志, vol. 3, p. 42. Guo Rucheng 郭汝诚 (1853). Available online: https://ctext.org/library.pl?if=gb&file=107682&page=341 (accessed on 2 March 2023).Siminyueling 四民月令. Cui Shi 崔寔 (103–170). Available online: https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&res=913478 (accessed on 2 January 2023).Songshi 宋史, vol. 116, Zhiguansan 职官三. Tuoketuo 托克托 (1314–1355). Available online: https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&chapter=735849&searchu=七夕&remap=gb (accessed on 2 January 2023).Straits Settlements, Blue Book, 1938.Tang Liudian 唐六典, vol. 2. Zhang Jiuling 张九龄 (678–740). Available online: https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&chapter=755018&remap=gb#p32 (accessed on 2 January 2023).Wan shu zaji 宛署杂记. Shen Bang 沈榜 (1540–1597). Available online: https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&res=545777&searchu=投小针&remap=gb (accessed on 2 January 2023).Secondary Sources

- Aw, Yue Pak 区如柏. 1987. Niucheshui yu xibeimen qijiehui shengkuang 牛车水与西北门七姐会盛况. Lianhe Zaobao 联合早报, August 23, p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Aw, Yue Pak 区如柏. 1996. Chuanchang da banqian lao yuangong qing nan she 船厂大搬迁老员工情难舍. Lianhe Zaobao 联合早报, July 14, p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, Dyer. 1925. Things Chinese: Or Notes Connected with China. Hong Kong and Shanghai: Kelly and Walsh. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, Xue-fei 毕雪飞. 2013. Qixi qiqiao zai riben de lishi bianqian yu xiandai jiangshu 七夕乞巧在⽇本的历史变迁与现代讲述. Journal of Jiangxi Agricultural University: Social Science 江西农业⼤学学报: 社会科学版 12: 404–8. [Google Scholar]

- Blythe, Wilfred L. 1947. Historical sketch of Chinese labor in Malaya. Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 20: 64–114. [Google Scholar]

- Boon, C. T. 1951. Girls’ greatest day of the year: Festival of Seven Heavenly Sisters. The Straits Times, August 13, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, Megan. 2015. Religious women and modern men: Intersections of gender and ethnicity in the tale of woman Huang. Signs 40: 623–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chay, Abigail 谢昇恩. 2013. Interviewed by Jesley Chua Chee Huan. National Archives of Singapore, Oral History Interview, Singapore, Performing Arts in Singapore, Accession Number 003782, Reel/Disc 38. February 7. [Google Scholar]

- Chia, Yee Kwan 谢愈君. 2000. Interviewed by Moey Kok Keong. National Archives of Singapore, Oral History Interview, Singapore, Chinatown, Accession Number 002381, Reel/Disc 39. November 9. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, Yoon Fong. 1984. Chinese female immigration to Malaya in the 19th and 20th centuries. In Historia: Essays in Commemoration of the 25th Anniversary of the Department of History, University of Malaya. Edited by Muhammad Abu Bakar, Amarjit Kaur and Abdullah Zakaria Ghazali. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Historical Society, pp. 357–71. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Chi-cheung. 2010. Stepping out? Women in the Chaoshan emigrant communities, 1850–1950. In Merchants’ Daughters: Women, Commerce, and Regional Culture in South China. Edited by Helen F. Siu. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, pp. 105–28. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Dong-ai 储冬爱. 2010. Queqiao qixi: Guangdong Qiqiaojie 鹊桥七夕: 广东乞巧节. Guangzhou: Guangdong Jiaoyu Chubanshe 广东教育出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Ci, Ren 慈仁. 1987. Baitou jiemei hua qiqiao 白头姐妹话七巧. Lianhe Zaobao 联合早报, August 29, p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Comber, Leon. 2009. Feast of the Seven Sisters. In Through the Bamboo Window: Chinese Life & Culture in 1950s Malaya & Singapore. Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society & Talisman Publishing Pte Ltd., pp. 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Croll, Elisabeth J. 1978. Feminism and Socialism in China. London: Routledge & Kagan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs, Stephen. 2003. The Singapore River: A Social History 1819–2002. Singapore: Singapore University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dung, Kai-Cheung. 2012. Atlas: The Archaeology of an Imaginary City. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard, Wolfram. 1972. Cantonese Ballads. Taipei: Oriental Cultural Service. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Chen, and Yanghuan Long. 2022. The secularization of religious figures: A study of Mahoraga in the Song Dynasty (960–1279). Religions 13: 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Mu 风木. 1975. Xianhua qixi 闲话七夕. Nanyang Siang Pau Press 南洋商报, August 13, p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Feuchtwang, Stephan. 2010. The organisation of extravagance as charismatic authority and self-government. In The Anthropology of Religion, Charisma and Ghosts: Chinese Lessons for Adequate Theory. Edited by Gustavo Benavides, Kocku von Stuckrad and Winnifred Fallers Sullivan. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, pp. 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, Maurice. 1957. Chinese Family and Marriage in Singapore. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Beata. 1995. Patterns of female religious experience in Qing dynasty popular literature. Journal of Chinese Religions 23: 29–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, John Henry. 1880. Fourteen Months in Canton. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, It Chong. 1958. The Cantonese Domestic Amahs: A Study of a Small Occupational Group of Chinese Women. Singapore: Department of Social Studies, University of Malaya, Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Kwai Min 何桂绵. 1992. Interviewed by Tan Beng Luan. National Archives of Singapore, Oral History Interview, Accession Number 001393, Reel/Disc 3. December 24. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Jin-tang 洪锦棠. 1950. Qixi qiqiao yu qijiehui: Liyuan er nüzhi qingzhu queqiaohui buwang shan ju 七夕乞巧与七姐会: 李袁二女士庆祝鹊桥会不忘善举. Nanyang Siang Pau Press 南洋商报, August 21, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Shu-ling 洪淑苓. 1988. Niulangzhinu yanjiu 牛郎织女研究. Taipei: Taiwan xuesheng shuju 台湾学生书局. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Pu-an 胡朴安. 1988. Guangdong. In Zhonghua quanguo fengsu zhi 中华全国风俗志. Shanghai: Shanghai wenyi chubanshe 上海文艺出版社, p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Jaschok, Maria, and Suzanne Miers, eds. 1994. Women and Chinese Patriarchy: Submission, Servitude, and Escape. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jashok, Maria. 1984. On the lives of women unwed by choice in pre-communist China: Research in progress. Republican China 10: 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, David K., and Daniel L. Overmyer. 1986. The Flying Phoenix: Aspects of Chinese Sectarianism in Taiwan. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, Rong 军荣. 2002. Qiaosimiaoxiang de shidai shiming qiqiaojie 巧思妙想的世代使命—七巧节. Lianhe Wanbao 联合晚报, August 11, p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Kaye, Barrington. 1960. Upper Nankin Street in Singapore: A Sociological Study of Chinese Households Living in a Densely Populated Area. Singapore: University of Malaya Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, Ernest. 2010. Singapore Stories: Language, Class, and the Chinese of Singapore, 1945–2000. Amherst: Cambria Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Su-chun 赖素春. 2020. Hexi zaixian qixi: Yi xinjiapo weili 何昔再显七夕: 以新加坡为例. In Qixi wenhua jieqing yu chuanbo 七夕文化: 节庆与传播. Edited by Zhi-xian Pan 潘志贤, Ying-jun Ye 叶映均 and Zhi-jian Ou 区志坚. Hong Kong: Zhonghua shuju xianggang youxian gongsi 中华书局(香港)有限公司, pp. 231–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lebra, Joyce. 1980. Immigration to Southeast Asia. In Chinese Women in Southeast Asia. Edited by Joyce Lebra and Joy Paulson. Singapore: Times Books International, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Kok Leong 李国樑. 2015. Guangdong majie: Shunfeng xia nanyang dexing chuanren jian 广东妈姐: 顺风下南洋, 德行传人间. Singapore: Xinjiapo shunde huiguan 新加坡顺德会馆. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Soon Sum 李顺森. 1990. Interviewed by Yeo Geok Lee. National Archives of Singapore, Oral History Interview, Singapore, Chinese Dialect Groups, Accession Number 001096, Reel/Disc 9. January 16. [Google Scholar]