Abstract

This paper attempts to examine the genealogical framework of “lamp records” (denglu 燈錄) of the Chan Buddhist tradition using analytical tools and methods of Historical Social Network Analysis (HSNA) and graph theory. As an exploratory study, the primary objectives are to investigate the possibilities offered by HSNA and visualization tools for research on Chan genealogy in lamp records, explore the benefits of this approach over traditional lineage charts, and reflect on its limitations. The essay focuses on the Chan community portrayed in the Goryeo 高麗 edition of the Zutang ji 祖堂集 (Collection of the Patriarchal Hall; K.1503). It shows that the lineage reportedly stemming from Qingyuan Xingsi 青原行思 (d. ca. 740) and Shitou Xiqian 石頭希遷 (701–791), as well as the branch descending from Tianhuang Daowu 天皇道悟 (748–807) to Xuefeng Yicun 雪峰義存 (822–908) and his successors, play a crucial role within the structure of the Zutang ji’s genealogical network. The study further highlights possible irregularities in lineage claims by contrasting metrics of degree and betweenness centrality with features of the text (e.g., number of hagiographic entries, length of the entries).

Keywords:

Zutang ji; lineage; network; Historical Social Network Analysis; Gephi; Chan Buddhism; Goryeo canon 1. Introduction

Genealogy has been a source of concern for Buddhist monks that we retrospectively associate with the “Chan school” (Chanzong 禪宗) since at least the late seventh century.1 Around the year 689, a community of monks who followed a meditation master (chanshi 禪師) named Faru 法如 (638–689) had carved into stone the oldest extant record of a master-to-disciple lineage stemming from a certain Bodhidharma 菩提達摩 (d. ca. 530). Ostensibly erected in the memory of Faru’s legacy, this stele inscription—titled Tang Zhongyue shamen Shi Faru chanshi xingzhuang 唐中岳沙門釋法如禪師行狀 (Record of Conduct of the Meditation Master and Śramaṇa Shi Faru of Mt. Zhongyue of the Tang)—establishes a list of authoritative figures who purportedly initiated the transmission of a particular set of oral teachings, beginning in India with the Buddha, Ānanda 阿難, Madhyāntika 末田地, and Śāṇavāsa 舍那婆斯. The inscription thereupon reports that these teachings or tenets (zong 宗) were inherited and carried on by a “Tripiṭaka master of South India 南天竺三藏法師” named Bodhidharma, who brought them to the “neighboring Eastern country 東鄰之國,” that is, China. The epitaph eventually claims that Bodhidharma subsequently passed down these teachings to Huike 慧可 (ca. 485–ca. 555 or after 574), after which they were transmitted successively to Sengcan 僧璨 (d. 606?), Daoxin 道信 (580–651), Hongren 弘忍 (ca. 601–ca. 674), and Faru.2

Thereafter, different groups who followed other religious leaders supplemented or remodeled the lineage claims found in Faru’s epitaph through their own literary productions. The Chuan fabao ji 傳法寶紀 (Record of the Transmission of the Dharma Treasure),3 for example, contended that Faru somehow passed on or ceded his authority to Shenxiu 神秀 (ca. 606–706) just before his death.4 The Lengqie shizi ji 楞伽師資記 (Record of the Masters and Disciples of the Laṅkā[vatāra]),5 on the other hand, had the famed translator Guṇabhadra 求那跋陀羅 (394–468) precede Bodhidharma, more or less ignored Faru, championed Shenxiu as the leading disciple of Hongren, and seemingly singled out four individuals as Shenxiu’s successors.6 Concurrently, scholar-officials such as Zhang Yue 張說 (667–731), Li Yong 李邕 (678–747), Li Hua 李華 (ca. 715–774), and many others, through the funerary inscriptions that they composed for noted Chan or Tiantai 天台 masters, also participated in the circulation of particular lineage claims.7

It is not before the turn of the ninth century, however, that the lineage narrative that would become paradigmatic for the later Chan tradition was formulated and substantiated in the influential Baolin zhuan 寶林傳 (Chronicle of the Baolin [Monastery]; hereafter BLZ).8 Borrowing from earlier sources, the BLZ promoted a list of 33 patriarchs, among whom 28 patriarchs of India—from the Buddha’s disciple Mahākāśyapa 摩訶迦葉 to Bodhidharma—and six patriarchs of China, from Bodhidharma to Huineng 慧能 (638–713)—the latter being likely regarded as the sole legitimate heir of Hongren.9 In addition, as evidenced by Shiina Kōyū’s 椎名宏雄 research, the text’s tenth and last juan 卷 (fascicle) contained accounts for several of Huineng’s alleged first- and second-generation successors.10 There is little doubt, therefore, that the BLZ espoused the claim made in earlier Chan texts, such as the Putidamo Nanzong ding shifei lun 菩提達摩南宗定是非論 (Treatise on Establishing the True and the False in the Southern School of Bodhidharma) or the Liuzu tanjing 六祖壇經 (Platform Sūtra of the Sixth Patriarch), that Huineng had put an end to the transmission of the robe (yi 衣 or jiasha 袈裟)—i.e., one of the presumed symbols of patriarchal authority—and with it the unilineal transmission from one patriarch to the next.11 The BLZ’s version of Chan genealogy and literary structure, it could be argued, paved the way for the development of the complex multi-branched genealogies witnessed in later records such as the Zutang ji 祖堂集 (Collection of the Patriarchal Hall; hereafter ZTJ) and the Jingde chuandeng lu 景德傳燈錄 (Jingde[-Era] Record of the Transmission of the Lamp; hereafter JDCDL).12

In consideration of the few examples given above, it is evident that the various lineages championed in early Chan records should not be taken at face value. As T. Griffith Foulk pointed out 30 years ago, examination of “ostensibly historical lineage records reveals that they were fabricated retrospectively as a means of gaining religious authority, political power, and/or patronage.”13 This is most conspicuous in early Chan records and investigation into their socio-religious or sectarian background is to a certain extent facilitated by their focus and quasi-unilineal genealogical claims, a feature that was possibly already descried by the famed scholar-monk Guifeng Zongmi 圭峰宗密 (780–841).14 The picture is blurred, however, when we turn to a text like the ZTJ, which is not only difficult to approach from a methodological perspective due to its layered textual history, but also presents the reader with an intricate, multi-branched genealogy up to the alleged eighth generation of successors to Huineng. Challenges posed by the ZTJ are evidenced by the conflicting conclusions found in previous scholarship concerning the lineage(s) presumably championed in the received text.15 How, then, should we examine the socio-religious agendas of Chan collections that embrace multi-branched genealogies and whose circumstances of production remain unclear? What alternative methods could complement, support, or guide traditional philological analysis of these records and their paratext?

The primary objectives of this essay are to determine whether analytical tools of Historical Social Network Analysis (HSNA) and graph theory can help inform our understanding of the underlying genealogical claims of tenth and post-tenth century Chan texts traditionally known as “lamp records” (denglu 燈錄), and whether these can provide new insights into their context of production. More specifically, the study focuses on the ZTJ as it is the presumed earliest, fully extant Chan lamp record to adopt a substantial multi-branched genealogy.16 From a methodological perspective, I should emphasize that I do not treat the lineage claims presented in the ZTJ as pointing to historical events, but as literary artifacts that reflect both the partisan entrenchment of the text’s compilers and their religious aspirations. My aim is not to deny that there might be a historical basis for some of the lineages traced in the ZTJ but that these probably better represent the literary and religious orientations of the text and its compilers, as well as the limitations of such a project.17

In terms of structure, the first section of this paper provides a short overview of the ZTJ, including aspects of textual history and its place in the literary landscape of Chan circles of the tenth and early eleventh centuries. The second section presents the data collected in the framework of this study, relates how it was compiled, and discusses some of its limitations. In the third part of the paper, I proceed to the analysis of the relevant HSNA metrics (i.e., degree and betweenness centrality) and visualizations obtained via the open-source software Gephi. Eventually, in the concluding section, I summarize the findings of this preliminary study, evaluate the contributions and limitations of HSNA for analyzing the genealogical framework of individual Chan records, and highlight potential lines of inquiry for future research.

2. The Zutang ji: Elements of Textual History, Structure, and Genealogy

The ZTJ is the earliest known extant “lamp record” of the so-called southern Chan school organized around a full-fledged, multi-branched genealogy. The text was initially compiled by two Chan monks named Jing 靜 (d.u.) and Yun 筠 (d.u.), whose identities have yet to be convincingly ascertained, and it was prefaced, at their request, by Chan master Jingxiu 淨修 (d. 972, also known as Wendeng 文僜) of the Zhaoqing monastery 招慶寺 in Quanzhou 泉州.18 According to his hagiographic entry in juan 13 of the ZTJ and later texts, Wendeng was a successor of Baofu Congzhan 保福從展 (d. 928), who was himself a “dharma heir” of Xuefeng Yicun 雪峰義存 (822–908), an influential Chan master of the branch reportedly stemming from Qingyuan Xingsi 青原行思 (d. 738/740) and Shitou Xiqian 石頭希遷 (701–791) during the late Tang 唐 (618–907).19 Whereas the earliest layer of the ZTJ was compiled in the mid-tenth century, likely around 952,20 the sole extant witness of the text is presently the 1245 Goryeo 高麗 woodblock edition.21 In this regard, previous studies have shown that the ZTJ likely underwent three stages of compilation and/or editing process: (1) a mid-tenth century version in one juan edited by Jing and Yun, and prefaced by Wendeng; (2) an expanded 10-juan version, for the most part probably compiled during the second half of the tenth century or before the circulation of the imperially sanctioned JDCDL; and (3) the 1245 Goryeo edition which professedly subdivided the earlier 10-juan version into 20 juan.22

As I indicated previously, the ZTJ inherits the patriarchal lineage championed in the BLZ, from Mahākāśyapa to Huineng. In addition to the 33 patriarchs, the BLZ also contained entries and accounts related to a few putative successors of Huineng in its nonextant tenth juan. Indeed, based on a series of quotations from the BLZ found in later sources, it can be inferred that the BLZ’s last juan included passages related to at least six first-generation disciples of Huineng—namely, Nanyue Huairang 南嶽懷讓 (677–744), Yongjia Xuanjue 永嘉玄覺 (665–713), Sikong Benjing 司空本淨 (667–761), Caoxi Lingtao 曹溪令韜 (d. 760), Nanyang Huizhong 南陽慧忠 (ca. 675–775), and Heze Shenhui 荷澤神會 (684–758)—and two second-generation disciples of Huineng—namely, Shitou Xiqian and Mazu Daoyi 馬祖道一 (709–788).23 In one of the surviving fragments, Shitou is identified as a successor of Xingsi but it is not entirely clear how much space was dedicated to the persona of Xingsi in the BLZ.24 The second, Mazu, is not explicitly identified as Huairang’s successor in the extant quotations. However, three fragments that reportedly quote from the BLZ’s tenth juan relate exchanges between the two monks which precede, in unabridged accounts of the encounter found in later Chan records, the presumed “transmission” from Huairang to Mazu.25 There is little doubt, therefore, that Mazu was regarded as the dharma heir of Huairang in the BLZ.26

Taking the BLZ as one of its sources, the version of Chan genealogy embraced in the ZTJ rests on the premise that the legitimate or principal heir of Hongren was Huineng and that the unilineal succession of the patriarchs (zu 祖, zushi 祖師) ended with the latter.27 In terms of structure, the text consists of a succession of hagiographic entries for 246 figures, arranged somewhat chronologically in clusters related to lineage affiliations.28 The first two juan cover the so-called “seven past buddhas” (guoqu qi fo 過去七佛), including Śākyamuni 釋迦牟尼, and the 33 patriarchs listed in the BLZ. The third juan contains the entries of four monks of Daoxin’s side-lineage, four monks of Hongren’s side-lineage, and eight first-generation disciples of Huineng. The sixth patriarch’s successors who have an entry in the ZTJ are, in order, Xingsi, Shenhui, Huizhong, Trepiṭaka Jueduo 崛多 (*Gupta; d.u.), Zhice 智策 (d.u.), Benjing, Xuanjue, and Huairang. With two exceptions, juan 4 to 13 then cover seven generations of monks in the line of succession of Xingsi, beginning with his presumed single dharma heir Shitou. The exceptions are the entry of Danyuan Yingzhen 耽源應真 (d.u.), successor of Huizhong, in the fourth juan, and that of Zongmi, allegedly a fourth-generation disciple of Shenhui, in the sixth juan. Finally, juan 14 to 20 record the entries of six generations of monks in the line of succession of Huairang, beginning with Mazu.29

In contrast to Faru’s epitaph and early Chan records, it is difficult to determine at first glance whether the compilers of the ZTJ favored a specific lineage or adopted an ecumenical perspective. Naturally, the Niutou school 牛頭宗 and Northern school 北宗 are not allotted much space in the text, but this is to be expected in a tenth-century southern Chan framework. We may therefore first ask ourselves the following: Does one of the two main branches represented in the ZTJ’s version of Chan genealogy—that of Xingsi–Shitou or that of Huairang–Mazu—appear to have been favored by the compilers of the text? If so, is this bias reflected in other ways in the text itself? This being the case, in consideration of the ZTJ’s complex textual history and composite nature, it would be more appropriate from a methodological perspective to first confine this inquiry to the received Goryeo edition, as we do not have access to earlier witnesses of the text, and we do not know whether the expanded version of the ZTJ was the result of the combined effort of its two initial compilers or other individuals.

Claims to authority being a central aspect of early Chan records, scholars have naturally turned their attention towards the sectarian background of the ZTJ. The arguments advanced so far, however, contradict each other. In 2006, Albert Welter for example argued that the ZTJ “definitely favors the descendants of Mazu Daoyi by placing their biographies in the final fascicles, giving the impression that the Chan legacy culminates in their activities.”30 Earlier, Yang Zengwen 楊曾文 had in contrast indicated that because the compilers of the ZTJ belonged to the lineage of Xuefeng, they had chosen to place the entries of the monks of the Xingsi–Shitou branch first and relegate the entries of the individuals of the Huairang–Mazu branch to the end of the collection.31 In the same vein, Jia Jinhua 賈晉華 mentioned the ZTJ’s “obvious sectarian inclination” towards the Shitou school,32 and Mario Poceski argued that the ZTJ’s compilers “decided to prioritize those Chan lineages that traced their ancestry back to Shitou […] at the expense of the spiritual descendants of Mazu,” finding further evidence of this in the structure of the work.33 A third stance is taken, for example, by Ge Zhaoguang 葛兆光 in the explanatory notes of his partial modern Chinese translation of the ZTJ where he writes that the ZTJ reflects fairly comprehensively, although through the lens of the “southern Chan school,” the history of Chan up to the Five Dynasties period (907–960/979).34

To a certain extent, the above conflicting statements echo the methodological difficulties posed by the complex textual history of the ZTJ. My purpose here will not be to demonstrate which of these allegations is more accurate than the others but rather to explore how this problem can be approached from the perspective of HSNA and graph theory, and whether these can offer satisfying answers or stimulate new hermeneutic processes in this regard. Before I proceed to the analysis of the HSNA metrics and visualizations, however, I will briefly introduce the data underpinning this project and discuss some of their limitations.

3. Materials, Data, and Methods

The data used for producing the tables and visualizations in the section below were collected from the ground up, from an examination of the photographic reproductions of the Goryeo woodblock prints of the ZTJ to the curation of the corresponding .csv files. Unless otherwise indicated, the data are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) License on Zenodo and are divided into three subsets. Ultimately, however, the data derive from a single source—namely, the ZTJ.35

The first subset contains TEI (Text Encoding Initiative)-based editions of four sections of the ZTJ in .xml format, together with a unique schema.36 The primary source on the genealogical network of the text is retrieved from the Goryeo preface of Seok Gwangjun 釋匡儁 (d.u.). Gwangjun’s preface contains a list of names that functions both as an approximate table of contents of the hagiographic entries contained in the twenty-juan ZTJ and a lineage chart—although textual—of the Chan patriarchs and masters. A typical excerpt of this list reads as follows:

To Shitou succeeded: Reverend Tianhuang, Reverend Shili, Reverend Danxia, Reverend Zhaoti, Reverend Yaoshan ([With this] the fourth fascicle is concluded), Reverend Dadian, and Reverend Changzi. (The seven individuals above are [members of] the forty-third generation). To Tianhuang succeeded: […].石頭下出:天皇和尚、尸利和尚、丹霞和尚、招提和尚、藥山和尚 (第四卷已畢。)、大顛和尚、長髭和尚。(已上七人,四十三代。) 天皇下出:[…]37

While the list of names provided in the Goryeo preface exceeds the number of actual entries in the main text of the ZTJ, all individuals and their pedigree are in fact recorded in the ZTJ.38 In addition, because the Goryeo preface seems to have omitted for purpose of brevity the names of Cizhou Faru 磁州法如 (723–811) and Yizhou Weizhong 益州惟忠 (d. 821) of the so-called Heze school 荷澤宗, and likely omitted by inadvertence the name of Xinghua Cunjiang 興化存獎 (830–888),39 I supplement evidence for these individuals and their pedigree through two fragmentary TEI editions of the corresponding excerpts of the ZTJ.40 The figures (nodes) and the lineage claims (edges) that appear in the data are thus all part of the dharma lineages presented in the text.41 The TEI markup of the relevant sections of the ZTJ differs from the type of markup found in my diplomatic and regularized editions of the two prefaces of the ZTJ and is limited to HSNA.42 In addition to the basic structural markup, two elements are used to mark-up the names of the individuals (<persName>) and the toponyms (<placeName>) that appear in the text. These elements each have a @key attribute that corresponds to the relevant identifiers (ID) retrieved from the Buddhist Studies Authority Database Project 佛學名相規範資料庫建置計畫 of the Dharma Drum Institute of Liberal Arts 法鼓文理學院 (DILA).43 The nexuses (<linkGrp> and child elements) are found at the end of the TEI document.44

The second subset consists of the data extracted from the TEI editions. This includes an .xml file that consists of the nexuses and the name of the source texts from which they were extracted. This .xml file was subsequently converted using XQuery into a .gexf file, with further input of data from the DILA Authority Database Project (e.g., labels, years of birth and death, gender) retrieved through the correspondence of the individuals’ identifiers. Lacunae of the data contained in this .gexf file reflects the current state of the DILA Authority Database.

The third subset of data consists of the .csv files for the nodes and edges that were used to produce the HSNA metrics and visualizations with Gephi. Whereas the .gexf file mentioned above could have been used directly for this purpose, my aim was to produce a cleaner set of data containing only curated relevant information. The data for the edges of the .gexf file were converted to a .csv file which, in addition to the sources and targets, contains information on the type of the network, an automatically generated ID, and the exact references in the CBETA edition of the ZTJ. The data concerning the nodes, on the other hand, were almost entirely remodeled. First, in the .csv file, the nodes’ labels correspond to the names used in the entries of the ZTJ or the list of the Goryeo preface. Second, in addition to the IDs and labels, I provide the number of the generation to which each individual reportedly belongs and a label that situate these figures in clusters found in the text, such as the seven past buddhas, the 27 patriarchs of India (Tianzhu ershiqi zu 天竺二十七祖), the six generations (of patriarchs) of China (Zhendan liu dai 震旦六代), the “collateral“ (pang 傍/旁) branches of Bodhidharma, Daoxin, and Hongren, and the various successive generations after Huineng. Eventually, the .csv file records the length of each entry in the ZTJ (expressed in number of characters), a numerical value (0 or 1) that indicates whether a praise by Wendeng was appended or not to the end of the entries of these figures in the ZTJ, and information on their presumed country of origin (Tianzhu, Zhendan, or Dongguo 東國, the last corresponding to the Korean peninsula). This simplified .csv table is supplemented by a table in .xlsx format that presents further information such as the juan in which the entries are located, a numerical value that indicates their order of succession in the text, the exact names given in the ZTJ and the Goryeo preface, both with references to the Goryeo woodblock edition, the Zen bunka kenkyūjo 禅文化研究所 photographic reproduction, and two modern critical editions of the text.45

Because the primary focus of this study is not on the individual lineage claims championed in the ZTJ, but on the compilers’ conscious effort to present (selected) Chan circles from different periods and regions as belonging to one dharma family, I treat the resulting network as undirected. In other terms, I am not attempting to reconstruct an underlying historical network of religious actors based on the lineage claims found in the ZTJ. Rather, I examine how the compilers of the ZTJ pieced together this particular Chan community, explore who in this network are the figures that hold the family legacy together, and evaluate what this network, in turn, reveals about the possible circumstances surrounding the compilation of the ZTJ. Accordingly, the fact that I interpret this textual network as undirected is not an artifact of the data itself but is contingent on the research questions that guide this study. In this framework, the geodesic distance (i.e., shortest path) between two nodes is indicative of their closeness or proximity within the network depicted in the ZTJ, and high betweenness centrality metrics therefore reflect the centrality of these nodes in holding together this newly fleshed out Chan community.

Regarding the limitations of these datasets, I should first mention that the approach adopted in this paper, with its focus on lineages, inherits the biases of the version of Chan genealogy presented in the ZTJ. As Foulk rightly pointed out, the Chan schools or circles that can be identified within the text naturally included more members than those few individuals who were singled out as the dharma heirs of a given master.46 The resulting visualizations are therefore that of an aggregation of ego networks centered around those whose status was recognized and/or legitimized in the ZTJ. Second, the very nature of the lineal structure, in which the connection is supposedly located at the interpersonal level between two monks, flattens complex patterns of interactions. For instance, this approach does not consider the actual relationship between these individuals, the frequency of their encounters, the duration of their contacts, and so forth. In addition, in its current state, the data are limited to the lineage claims and ignore the social interactions recorded in the text (e.g., alleged encounters of masters, exchange of letters, networks of commentarial practices). However, because I treat the genealogical network of the ZTJ as a literary product, these limitations are anticipated and should not impact the reliability of the findings of the study. Likewise, deliberate appropriations of celebrated figures and forged or erroneous lineage claims should not be a source of concern as my focus is on the textual nature of the network, precisely as it is transmitted through the ZTJ. However, such cases should be examined carefully as these may provide important hints concerning the ZTJ’s potential agendas.

Eventually, although the visualizations presented in the section below are to some extent reminiscent of the “string of pearls” fallacy, to borrow John R. McRae’s expression,47 examining this string (i.e., the received text of the ZTJ), with the pearls that are threaded onto it (i.e., the buddhas, patriarchs, and masters who have an entry in the ZTJ) and their specific arrangements (i.e., the ZTJ’s structure and genealogical claims), should nonetheless help us better understand the literary and socio-religious circumstances surrounding the compilation of the ZTJ. In this respect, I should reiterate that I do not regard the information on the pedigree of the patriarchs and masters recorded in the text as a historically reliable source on these monks’ lineages. Rather, I examine these lineage statements as offering insights into the context in which the ZTJ was compiled. Naturally, I do not wish to suggest that we cannot rely on any of these associations and should abandon history altogether. However, my focus here is resolutely on the “representation of history,”48 as conveyed through the ZTJ.

4. The Zutang ji through the Lens of HSNA and Graph Theory

In addition to evaluating the possibilities offered by HSNA for research on the genealogical framework of Chan lamp records, another objective of this essay is to investigate the dharma family portrayed in the received text of the ZTJ and determine whether the record shows signs of partiality towards one or more (sub-)branch(es) of this textual community. Considering its southern Chan background, we should first confirm whether the collection indeed demonstrates a bias in favor of the alleged lineal descent of Huineng and clarify its magnitude. Second, and more importantly, we should investigate whether the ZTJ shows preferential treatment for the Xingsi–Shitou branch or the Huairang–Mazu branch, or whether these are fairly evenly represented in the text. To provide a first answer to these questions, let us examine the visualizations of the HSNA data created with Gephi in Figure 1 and Figure 2 below.

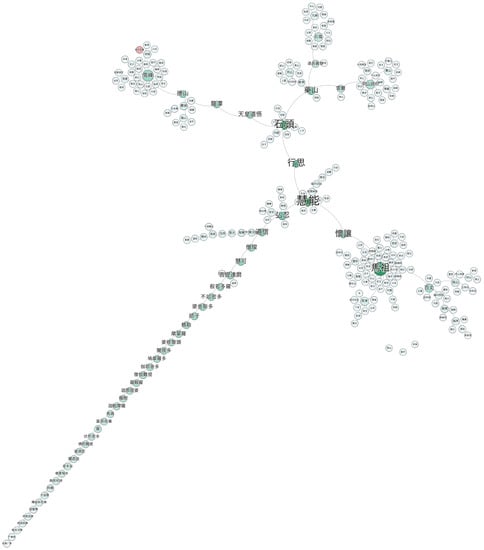

Figure 1.

Overview of the ZTJ’s version of Chan genealogy. Generated with Gephi (version 0.9.5), with Force Atlas 2. The size of the nodes is proportional to their degree centrality (min. size: 10, max. size: 20). The color (shades of green) of the nodes and the size of the nodes’ labels (min. size: 0.5, max. size: 2.5) are proportional to their betweenness centrality. Once spatialized, Force Atlas 2 was run a second time with the “Prevent overlap” option checked. The author of the ZTJ’s original preface, Fuxian Zhaoqing 福先招慶 (i.e., Wendeng), is colored in red.

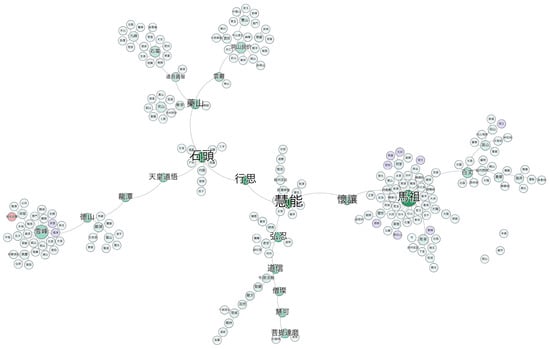

Figure 2.

Overview of the ZTJ’s version of Chan genealogy: from Bodhidharma onwards. Generated with Gephi (version 0.9.5), with Force Atlas 2. Description is identical to Figure 1. The nodes of the Silla monks are colored in purple.

The visualization output in Figure 1 displays the Chan dharma family depicted in the ZTJ, from the seven past buddhas to the later generations of Chan masters. First, the mythical origin of the ZTJ’s version of Chan genealogy is conspicuous, beginning with the presumed transmission from the first six past buddhas to Śākyamuni, subsequently proceeding with Mahākāśyapa, Ānanda, Śāṇavāsa,49 and so forth, up to Bodhidharma—that is, the pivot of the transmission from India to the Chinese territory.50 The list of the six patriarchs of China is inherited from earlier texts of the southern Chan tradition (e.g., Liuzu tanjing, BLZ).51 However, the ZTJ appears to be the earliest extant southern Chan record to include dedicated entries for monks of the “collateral” branches of Daoxin and Hongren.52 Second, although the ZTJ provides entries for eight main successors of Huineng, the graph leaves no doubt about the legacy of the sixth patriarch, which runs through Xingsi and his presumed dharma heir Shitou on the one hand, and Huairang and his purported successor Mazu on the other. This, as we have seen, is reflected in the general structure of the work. Among the other successors of Huineng, the ZTJ records an entry for Danyuan Yingzhen who reportedly succeeded Huizhong and documents a unilineal branch seemingly stemming from Heze Shenhui up to Zongmi.53 Besides the sixth patriarch, noticeable clusters in the Xingsi–Shitou branch are centered around the figures of Shitou Xiqian, Yaoshan Weiyan 藥山惟儼 (d. 827/834), Shishuang Qingzhu 石霜慶諸 (809–888), Dongshan Liangjie 洞山良价 (807–869), Yantou Quanhuo 巖頭全豁 (828–887), and Xuefeng Yicun.54 Regarding the Huairang–Mazu branch, we find clusters around Mazu Daoyi, Baizhang Huaihai 百丈懷海 (749–814), Nanquan Puyuan 南泉普願 (748–834), and Guishan Lingyou 潙山靈祐 (771–853). The sub-branches of the Xingsi–Shitou line, composed of multiple ego-centered clusters, are more disjointed than the clusters of the Huairang–Mazu branch.

To better visualize the section of the lineage that is of interest for the present study, Figure 2 above omits the nodes of the seven past buddhas and the first 27 patriarchs of India. In addition, the graph is rotated to increase visibility and the nodes of the Silla 新羅 monks are colored in purple to highlight where these appear in the lineages. Below, I provide two tables with relevant metrics concerning the degree centrality (Table 1) and betweenness centrality (Table 2) of the nodes in the network.

Table 1.

Figures ranked by degree centrality (≥5) in the ZTJ’s genealogical network.

Table 2.

Figures ranked by betweenness centrality in the ZTJ’s genealogical network. Scope: 20 nodes.

Table 1 provides a list of 16 monks ranked by degree centrality (≥5) which, in our case, corresponds to the number of direct lineal connections of a monk, as recorded in the ZTJ. In other words, the numerical value of the degree centrality of a monk represents the sum of his connections with his putative dharma heirs and his master. For example, the ZTJ records that Mazu succeeded Huairang and provides entries for 32 of his successors, giving a degree centrality of 33. Xuefeng, who succeeded Deshan Xuanjian 德山宣鑑 (780–865) and had 21 main successors according to the ZTJ, has a degree centrality of 22. By itself, this table does not provide any new or insightful information, but we may wish to note that the individuals listed here are for the greater part historically influential figures. The data presented in Table 1 become more interesting when contrasted with Table 2 above.

In this second table, 20 figures are ranked according to their betweenness centrality which, as mentioned earlier, is in our case indicative of their centrality in holding together or participating in the cohesiveness of the Chan community portrayed in the ZTJ. First, it is not surprising to find that the node with the highest betweenness centrality in the lineage is none other than Huineng. This confirms how central the figure of the sixth patriarch is in the ZTJ’s version of Chan genealogy, despite a degree centrality more than three times inferior to that of Mazu and two times inferior to that of Xuefeng. This also illustrates that betweenness centrality is likely to be a better indicator of the general centrality of an actor in lineage-based textual networks than degree centrality. Interestingly, the four individuals with the highest betweenness centrality after Huineng are, in order, Shitou, Mazu, Xingsi, and Huairang. Likewise, this shows that these monks occupy key roles in the ZTJ’s genealogical framework. Without them, the greater part of the network or Chan family would fall apart.

Because Shitou and Xingsi precede, respectively, Mazu and Huairang in terms of betweenness centrality, we could put forward the hypothesis that the ZTJ demonstrates an inclination towards the Xingsi–Shitou branch. This, in turn, appears to be supported by the fact that among the 20 figures listed in Table 2, we find, in order, Yaoshan, Tianhuang Daowu 天皇道悟 (748–807), Deshan, Longtan Chongxin 龍潭崇信 (d.u.), and Xuefeng, all associated in the ZTJ with the Xingsi–Shitou line. In contrast, successors of the Huairang–Mazu line are absent from this table, and it is only at the twenty-third place that we find Baizhang Huaihai, with a betweenness centrality of 0.179731. The next in line is Nanquan Puyuan, who ranks 46, with a betweenness centrality of 0.060190. The presence of numerous patriarchs in this table is explained by the fact that nodes situated on the “trunk” of the tree structure of the Chan lineage are situated on the geodesic distance between many nodes in the network.55 More interestingly, Table 2 suggests that, within the Xingsi–Shitou branch, the line of succession from Daowu to Xuefeng is of particular importance in the ZTJ’s genealogical framework. It also highlights the crucial role played by Yaoshan as a bridge between the clusters centered around Dongshan Liangjie, Shishuang, and Jiashan Shanhui 夾山善會 (805–881) on the one hand, and Shitou on the other.

From a methodological perspective, I should emphasize that the results above do not indicate that the ZTJ, in terms of contents, gives more weight to the Xingsi–Shitou branch. They merely illustrate that within the ZTJ’s version of Chan genealogy, it is the branch of Xingsi, Shitou, and their putative successors that appears to take precedence over that of Huairang and Mazu. These indicative HSNA metrics are therefore not sufficient to determine with certainty the possible sectarian inclinations of the text and should be complemented with other elements. If we restrict our analysis to the textual features of the ZTJ, among the factors that we should take into consideration are the number of entries in each of the two prevailing branches, the length of these entries, and the number of generations and individuals by generation recorded for each branch.

First, the consensus is that the ZTJ contains a total of 246 hagiographic entries, despite the fact that the last entry—that of Miling 米嶺 (d.u.)—neither begins on a new line in the Goryeo edition nor records the expected basic biographic information.56 In the first three juan, there are 7 entries for the past buddhas, 27 for the patriarchs of India, 6 for the patriarchs of China, 4 for the collateral branch of Daoxin, 4 for the collateral branch of Hongren, and 8 for the putative dharma heirs of Huineng. From juan 4 to 13, there are in total 106 entries, including 1 entry for Shitou, 1 for Danyuan, 1 for Zongmi, and 103 for the alleged successors of Shitou. From juan 14 to 20, there are in total 84 entries, including 1 entry for Mazu and 83 for his presumed successors. The ZTJ thus includes more entries for monks associated with the Xingsi–Shitou branch than that of Huairang–Mazu, which to a great extent explains why more figures in the Xingsi–Shitou branch have a higher betweenness centrality.

The crude distribution of the number of entries in the ZTJ, however, should not be taken at face value and should be complemented by an examination of the length of these entries. In Figure 3 below, I provide a visualization of the Chan community depicted in the ZTJ in which the size of the nodes is proportional to the length of the entries in the text.57 It is followed by Table 3, which lists the 30 longest entries in the ZTJ.

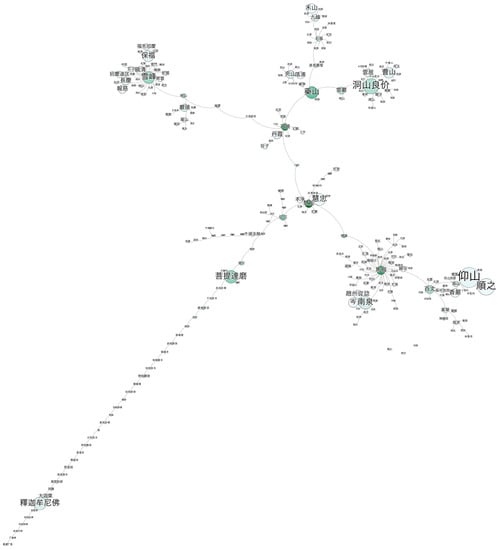

Figure 3.

The ZTJ’s version of Chan genealogy: textual perspective. Generated with Gephi (version 0.9.5), with Force Atlas 2. The color (shades of green) of the nodes corresponds to their betweenness centrality. The size of the nodes (min. size: 2, max. size: 30) and labels (min. size: 0.5, max. size: 2.5) are proportional to the length of the entries. The nodes of the individuals who appear in the lineage but do not have an entry in the ZTJ are colored in black. To prevent overlap, I occasionally dragged some of the nodes manually in Gephi.

Table 3.

Figures with the longest entries in the ZTJ (in characters). Scope: 30 entries.

Because the length of the entries is examined here as an additional indicator of potential partisanship in the ZTJ, I will not discuss specificities individually in what follows. It should be noted, however, that the two monks who have the longest entries in the ZTJ are Yangshan Huiji 仰山慧寂 (807–883), one of the two founding figures of the so-called Guiyang school 溈仰宗, and his disciple Ogwan Sunji 五冠順之 (ca. 858–893) of the Korean peninsula, both belonging to the Huairang–Mazu branch. The third-longest entry is that of Dongshan Liangjie, one of the founding figures of the Caodong school 曹洞宗 and a celebrated master of the Xingsi–Shitou branch. The fourth is that of Śākyamuni who was somewhat eclipsed in HSNA metrics, but whose importance is revealed by the extent of his entry in the ZTJ. Most importantly, among the 30 entries listed in Table 3, 18 are associated with the Xingsi–Shitou line, while only 8 represent the Huairang–Mazu branch. The total length of these 30 entries amounts to approximately 102,004 characters and 54.68% of the total length of all entries recorded in the ZTJ. Eventually, I should add that the average entry in the ZTJ consists of approximately 758 characters.

To further contextualize the data concerning the length of the entries contained in the ZTJ, in Table 4 below I list the different clusters or sections mentioned in the Goryeo edition of the text (e.g., the seven past buddhas, the twenty-seven patriarchs of India) and provide the number of entries per section, the total length of these entries (in characters), and the space that they occupy within the collection, proportionate to the total length of the entries in the ZTJ (ca. 186,551 characters; 246 entries).58

Table 4.

Proportion of sections of the ZTJ according to the length of the entries (in characters).

To summarize, entries from the seven past buddhas to Huineng account for approximately 12.74% (23,758 characters; 40 entries) of the total text of the ZTJ’s entries. Although this represents a non-negligible part of the collection, adequately located in the first two juan,59 it nevertheless illustrates that the received text of the ZTJ does not revolve around the patriarchs themselves but rather emphasizes their legacy through their successors up to the tenth century. Second, while the Niutou, Northern, and Heze schools appear in the text, the total length of the relevant entries account for a meager 2.15% (4006 characters; 10 entries) of the ZTJ’s entries. The southern Chan framework centered around the Xingsi–Shitou and Huairang–Mazu lineages, which in some measure began to take form with the BLZ at the turn of the ninth century, is therefore evident. Eventually, in line with HSNA metrics, the data presented in Table 4 above suggests that the Xingsi–Shitou branch (105 entries; 89,977 characters; 48.23%) also takes precedence over that of Huairang–Mazu (85 entries; 61,507 characters; 32.97%) in the received text of the ZTJ. Entries of the monks associated with the line of succession from Tianhuang Daowu to Xuefeng and his first- and second-generation heirs represent approximately 17.5% (32,642 characters; 32 entries) of the ZTJ’s entries.

Finally, another element that should be considered to refine our understanding of the Chan community portrayed in the ZTJ relates to the distribution of generations in the text. In this respect, we may observe that the ZTJ records monks over eight generations for the Xingsi–Shitou branch and over seven generations for that of Huairang–Mazu, with Xingsi and Huairang embodying, respectively, the first generation after Huineng.60 A complementary visualization such as that of Figure 4 below, however, allows us to put this seemingly small difference into perspective.

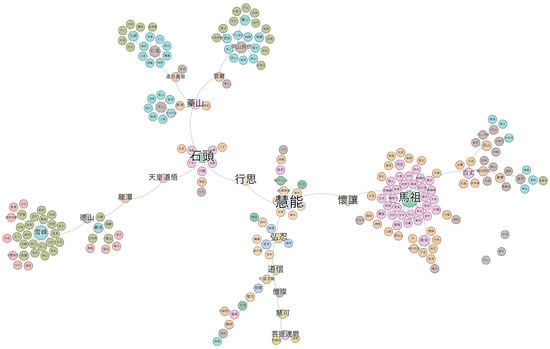

Figure 4.

The ZTJ’s version of Chan genealogy: from Bodhidharma onwards, colored by generation. Generated with Gephi (version 0.9.5), with Force Atlas 2. Description is identical to Figure 1. However, the nodes are colored by generation with a randomly generated palette.

From the distribution of generations presented in Figure 4, it is evident that the ZTJ includes more entries for monks of later generations in the Xingsi–Shitou line. If we follow the Goryeo preface, only four monks in the Huairang–Mazu branch reportedly belong to the seventh generation after Huineng.61 In addition, because the main text of the ZTJ does not record the pedigree of Yinshan 隱山 (d.u.), Xingping 興平 (d.u.), and Miling, and it is unlikely that they were disciples of Guanxi 灌谿 (d. 895), these three monks should not be counted as part of the seventh generation of the Huairang–Mazu line. In the Xingsi–Shitou branch, however, we not only find entries for 42 monks of the seventh generation after the sixth patriarch but also for 11 monks of the eighth generation,62 including the relatively long entries of Zhaoqing Daokuang 招慶道匡 (d.u.), Baoci Guangyun 報慈光雲 (d.u.), and Wendeng (1955 characters; 1.05%). Because the proportion of entries of these two branches in the ZTJ might not necessarily reflect the space that they occupy in the text, I provide in Table 5 and Table 6 below the number of entries for each generation of the two branches and the combined length of these entries by generation. Accordingly, I also indicate their proportion relative to the total number of entries in the ZTJ (i.e., 246) and the total length of these entries in the text (ca. 186,551 characters).

Table 5.

Generations of successors to Shitou in the ZTJ.

Table 6.

Generations of successors to Mazu in the ZTJ.

As witnessed in Table 5 and Table 6 above, the diachronic testimony of the Chan Buddhist landscape left by the ZTJ is that of a Xingsi–Shitou branch which began to flourish in its sixth generation—corresponding to the fourth generation of Shitou’s successors—reportedly due to the activities of famed masters such as Dongshan Liangjie, Shishuang Qingzhu, and Deshan Xuanjian. Conversely, the Huairang–Mazu branch is depicted as undergoing a steady decline as early as its fourth generation—corresponding to the second generation of Mazu’s successors.63 Several factors could explain this asymmetry in the ZTJ’s version of Chan genealogy and history. First, these results could indicate that the compilers either knew little or were unable to collect enough sources about monks of the Huairang–Mazu branch active in the second half of the ninth century and the first half of the tenth century. Second, this asymmetry could betray a certain partiality of the ZTJ’s compilers towards the Xingsi–Shitou line, whether this was intentionally designed or not in the compilation process of the text. Finally, the ZTJ’s impression of Chan genealogy could reflect the historical realities of a general or regional (temporary) decline of the Huairang–Mazu branch. Although this is far beyond the scope of the study, it is not unreasonable to speculate that a satisfactory answer to this issue will incorporate elements from all the above propositions.64

Before we return to HSNA-oriented questions in the paragraphs below, I would like to draw attention to an issue that is of no small significance regarding the textual history of the ZTJ and the terminus ad quem of its expansion, at least regarding the 10-juan version. Indeed, among the monks who reportedly belong to the seventh generation of the Xingsi–Shitou branch and whose approximate dates of death are known, we find Xuansha Shibei 玄沙師備 (835–908), Jingqing Daofu 鏡清道怤 (868–937), Gushan Shenyan 鼓山神晏 (d. 936~944), Changqing Huileng 長慶慧稜 (854–932), Baofu Congzhan (d. 928), Yunmen Wenyan 雲門文偃 (864–949), Qiyun Lingzhao 齊雲靈照 (870–947), and Heshan Wuyin 禾山無殷 (884–960). Among the figures of the eighth generation, we find Longguang Yinwei 龍光隱微 (886–961), Zhongta Huijiu 中塔慧救 (d. 913; also known as Huiqiu 慧球), Longtan Ruxin 龍潭如新 (894–934), and Wendeng (d. 972). Therefore, the monk whose known date of death is the latest appears to be none other than Wendeng, the author of the preface of the original ZTJ in one juan. In addition, according to Kinugawa Kenji, his entry in the ZTJ does not record any information posterior to around 949.65 In fact, the latest date recorded in the entries of the ZTJ is the “xinhai year 辛亥歲” of the Baoda 保大 era (951) of the Southern Tang 南唐 (937–976),66 and the latest date found among the editorial notes of the first two juan is the “renzi year 壬子歲” of the Baoda era (952).67 Accordingly, although we do have scattered evidence of slightly later additions or editorial interventions,68 it is nonetheless probable that the expanded ZTJ in 10 juan was completed in the course of the second half of the tenth century.69 Because the Goryeo edition, at least for its greater part, likely corresponds to the 10-juan ZTJ,70 the observations made in this study may well apply to this second version of the text.

To conclude this essay, I return to the visualizations and tables above and explore some of the “irregularities” that emerge when examining the data comprehensively. If we consider Figure 1 or Figure 2, for instance, we can observe that, in the post-Bodhidharma section of the lineage, there is an asymmetry between the high betweenness centrality of a few nodes and their low degree centrality. In other words, certain figures seem to hold together the Chan lineage championed in the ZTJ despite a very low number of disciples recorded in the text. If we now consider Figure 2 and Figure 3 together, yet another asymmetry can be noticed between the high betweenness centrality of certain nodes in the network and the briefness of the corresponding entries in the received ZTJ. Taking Table 2 as a reference, we find that figures with a high betweenness centrality such as the presumed twenty-seventh patriarch of India Prajñātāra 般若多羅, Huike, Sengcan, Xingsi, Huairang, Tianhuang Daowu, and Longtan Chongxin have the lowest degree centrality possible for nodes situated in this part of the network (i.e., 2) and that their entries in the ZTJ are relatively short when contrasted with their centrality in the lineage (see Table 7). Because we would expect influential or key figures to have a certain number of first- and second-generation disciples and the corresponding hagiographic entries to reflect their importance as socio-religious actors—as exemplified, in the ZTJ, by Mazu or Xuefeng for example—it seems warranted to examine such cases in more detail.

Table 7.

Figures with a high betweenness centrality, low degree centrality, and relatively short entry in the ZTJ. Total length of the entries: 3274 characters (1.76%).

The names appearing in Table 7 will probably raise the level of alertness of scholars of Chan studies since these often appear in discussions of literary and sectarian creativity: Prajñātāra is but the last candidate in a list of presumed predecessors to Bodhidharma;71 the personage of Huike, together with Bodhidharma and Sengcan, was perhaps borrowed from the Xu gaoseng zhuan 續高僧傳 (Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks) to manufacture the first instantiation of a lineage claim from Bodhidharma to Faru;72 Sengcan is a notoriously obscure figure for a patriarch;73 Xingsi and Huairang were famously qualified by Hu Shi 胡適 (1891–1962) as having been “exhumed from obscurity” to create connections to the semi-legendary figure of Huineng for both Shitou and Mazu;74 the figure of Daowu, as demonstrated by several scholars, was the subject of historical controversy within Chan circles and was not always exclusively associated with the Shitou branch;75 eventually, the connection of Chongxin and his master Daowu with the Xingsi–Shitou line was probably first emphasized by Deshan Xuanjian, disciple of Chongxin.76

It is interesting that the “irregularities” observed from an HSNA perspective would involve individuals and lineage claims that are all somewhat problematic or shrouded in mystery. The typical scenario appears to involve figures who did not enjoy great popularity during their lifetime, or at least whose life, activities, and disciples were poorly documented, but who were later “rediscovered” and brought to the fore because they acted as bridges between celebrated masters and later generations. This being the case, the metrics considered above do not systematically highlight—and we should not expect them to do so—all cases of suspicious lineage claims. Yaoshan, for instance, who, as we have seen, provides important connections between Shitou and later generation clusters centered around Jiashan Shanhui, Dongshan Liangjie, and Shishuang, may have been selectively remembered as a dharma heir of Shitou.77 However, no irregularity was detected when comparing HSNA metrics retrieved from the genealogical framework of the ZTJ and the length of Yaoshan’s entry in the text. Such limitations are discussed in more detail in the concluding section below.

5. Concluding Remarks

The primary objective of this study was to determine whether HSNA and graph theory are useful heuristic tools for exploring and analyzing the genealogical framework and possible sectarian biases of Chan lamp records such as the ZTJ. In this regard, metrics of degree centrality and, more importantly, betweenness centrality were used to identify key actors in the structure of the Chan community depicted in the ZTJ. These metrics not only confirmed the centrality of the figure of Huineng, but also that of the presumed initiators of the two most “productive” branches descending from Huineng up to the tenth century, namely that of Xingsi and Shitou, and that of Huairang and Mazu. Furthermore, HSNA metrics and visualizations revealed that, within the ZTJ’s version of Chan genealogy, the Xingsi–Shitou branch somewhat outweighs the Huairang–Mazu branch. In addition, they showed that the line of succession from Tianhuang Daowu to Xuefeng and his successors plays an important role in the Chan family portrayed in the ZTJ. In summary, there is little doubt that HSNA and graph theory can provide useful preliminary or complementary data for scholars of Chan lamp records and similar premodern Chinese religious texts. Reading a collection such as the ZTJ not only requires considerable effort and time, but it would be challenging, even for experts in the field, to provide more than a general intuition and/or selective observations regarding its potential factional agendas after reading it only once or twice. In this respect, HSNA not only presents well-defined metrics concerning the Chan community depicted in the ZTJ, but also provides the tools for a more nuanced take on its version of Chan genealogy. Indeed, one of the most interesting contributions of HSNA and graph theory is that these allow us to recognize differences of degree in terms of sectarian biases and are therefore well suited for maintaining a certain level of sophistication in our analyses.

By contrasting HSNA metrics with selected textual features of the ZTJ (e.g., the number of entries per section or per branch, the length of these entries, the number of entries by generations), the study revealed that the received text, despite its ecumenical outlook, shows a certain partiality towards the Xingsi–Shitou branch. Whether this reflects the socio-religious realities of the late Tang and early Five Dynasties, the sectarian motives of the ZTJ’s compilers, or the regional nature of the record is beyond the scope of this paper. However, it is not hard to conjecture that a combination of the above will probably offer the most satisfactory explanation as to the state of the received ZTJ. This is precisely the rationale that emerges when we reconcile the various perspectives articulated in previous scholarship.78 It would be misleading, however, to state that the ZTJ exclusively favored the Xingsi–Shitou line (105 entries; 89,977 characters; 48.23% of the total length of the entries) given the fair portion of the text allotted to the Huairang–Mazu branch (85 entries; 61,507 characters; 32.97%). This is all the more noteworthy when we consider the possibly local nature and historical situatedness of the collection.

Eventually, we examined metrics of degree and betweenness centrality, contrasting these with textual features of the ZTJ, to highlight potential irregularities in the structure of the Chan community portrayed in the collection. The few cases investigated all demonstrated a certain level of fabrication or partisanship, either inherited from previous records or from the compilers of the text themselves. This suggests that HSNA and visualizations could be used to uncover potential cases of partisan lineage claims and/or general trends in terms of sectarian inclinations in Chan records. However, I should reiterate that, when specifically directed towards the analysis of genealogical networks, HSNA should be complemented by other parameters, as illustrated in the present study. Furthermore, although HSNA and graph theory can hypothetically play a key role in stimulating new research questions about specific lineage claims and genealogical frameworks, philological analysis of primary sources will remain an indispensable tool to provide more conclusive answers to these inquiries.

Among the limitations of HSNA and the metrics explored in this study, I should first emphasize that betweenness centrality, due to its nature, is not adequate to evaluate the potential importance of monks listed among the last generations of their respective lineage. The low betweenness centrality of Nanyang Huizhong (0.007632), for instance, fails to explain why his entry ranks among the longest in the ZTJ (4207 characters; 2.26%), being in fact longer than that of Huineng (2555 characters; 1.37%) who ranks highest in betweenness centrality. To take an even more striking example, the monk of the Korean peninsula Sunji has a betweenness centrality of zero because of his eccentricity in the network, but his hagiographic entry is the second-longest (6020 characters; 3.23%) of all 246 entries recorded in the ZTJ. While probably a better metric than degree centrality to identify key actors in any complex genealogical network, betweenness centrality has its limitations when assessing the importance of nodes (i.e., monks) located towards the peripheries of the network. As mentioned in the introduction, however, entries of monks belonging to the later generations included in Chan records are in fact crucial to appreciate the lineage claims made in these texts. Indeed, they almost unequivocally reflect the records’ allegations concerning the presumed contemporary legitimate heirs of the Chan tradition.

Second, a more evident limitation of the approach adopted in this exploratory study resides in the silences left by HSNA. That contextualized analysis of betweenness centrality did not reveal any apparent irregularity for Yaoshan, for instance, does not indicate that the claim of lineal descent contained in the ZTJ is without problem. Conversely, cases of asymmetry between betweenness centrality and degree centrality and other factors will not necessarily point to suspicious lineage claims. Further studies are required to evaluate the contributions of HSNA and graph theory in the analysis of Chan genealogies and their ability to predict anomalies. In this regard, it would be particularly interesting to investigate whether the basic methods employed in this study could also be applied to premodern Chinese religious texts that similarly emphasize issues related to lineages.

Finally, I should reiterate that some of the complementary textual features examined in this essay equally have their own set of limitations. For instance, whereas the length of the entries might appear as an objective and precise indicator of the space allotted to specific monks or lineages in the ZTJ, we should bear in mind that, since we have very little direct evidence concerning the compilation process of the text or the sources used, we do not know the extent of the selectiveness or biases of the ZTJ’s compilers. If the collection was indeed compiled in or around Quanzhou and its neighboring regions, access to the relevant sources (e.g., xinglu 行錄, shilu 實錄, bielu 別錄, yuben 語本) may have been more limited regarding monks of the Huairang–Mazu branch than those of the Xingsi–Shitou line. In other terms, the length of these entries could be more indicative of the materials available to the compilers of the ZTJ than their editorial interventions and partisanship. The same reasoning could be applied to the individuals who were given an entry in the text. Cautiousness is therefore required when ascribing motives to the ZTJ’s compilers, especially since little is known about them.

Despite these few limitations, there is in fact much more potential for HSNA and the study of Chan records than presented in this essay. This exploratory inquiry was limited to the analysis of the ZTJ’s genealogical framework and therefore focused on the lineage claims recorded in the text. First, within the limits of the study, we were not able to explore all lines of potentially fruitful research. For instance, it would be of great value to analyze in more detail the various sub-branches of the Xingsi–Shitou lineage and investigate their respective importance in the ZTJ. Similarly, it would be interesting to examine which of the sub-branches of the Huairang–Mazu line is best represented in the text and explore the possible reasons behind those differences.79 The second and perhaps most stimulating avenue for research would be to compare the ZTJ’s version of Chan genealogy with those of later lamp records such as the JDCDL in order to put their individual contributions into perspective and better acknowledge their specificities. Finally, HSNA and graph theory have more traditional fields of application than the approach adopted in this paper. One could, for example, map all the interactions between actors recorded in the ZTJ in order to further our understanding of the networks of monks, literati, and rulers of the late Tang and Five Dynasties. Another possible line of inquiry would be to scrutinize the ZTJ and later lamp records for commentarial practices such as “raising” (ju 舉) or “replacing” (dai 代) and map the corresponding network of interactions. Yet another promising research area would be to investigate networks of poet-monks as recorded in Chan lamp records and examine how these compare, for example, with networks of exchange poetry.80 In this respect, it is my hope that this exploratory study on the ZTJ’s version of Chan genealogy, together with its data, will facilitate further HSNA studies of Chan records.

Funding

This research was completed with support from the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange 蔣經國國際學術交流基金會, DD010-U-20.

Data Availability Statement

The data and network graphs presented in this study are openly available on Zenodo. Please refer to the link provided by Marcus Bingenheimer in the Introduction to this Special Issue.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to Chen Song 陳松 and Christian Wittern for their insightful feedback on an earlier draft of this paper. I also extend my thanks to Wu Luchun 吳廬春 and Bart Dessein for their help and valuable suggestions. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the symposium “Perspectives of Digital Humanities in the Field of Buddhist Studies” (13–14 January 2023) at Hamburg University. My warmest thanks to the organizers of this symposium, Carsten Krause and Sebastian Nehrdich, for their kind invitation and the fruitful atmosphere.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| B | Dazangjing bubian 大藏經補編 |

| BLZ | Shuangfengshan Caohouxi Baolin zhuan 雙峰山曹侯溪寶林傳 |

| CBETA | Chinese Buddhist Electronic Text Association 中華電子佛典協會 |

| DMCT | Database of Medieval Chinese Texts 中古寫本資料庫 |

| JDCDL | Jingde chuandeng lu 景德傳燈錄 |

| P. | Dunhuang manuscripts from the Pelliot chinois collection, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris |

| QTW | Quan Tang wen 全唐文 |

| S. | Dunhuang manuscripts from the Stein collection, The British Library, London |

| T | Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 |

| X | Wan xinzuan xuzanjing 卍新纂續藏經 = Shinsan Dai Nippon zokuzōkyō 新纂大日本續藏經 |

| ZBK | Zen bunka kenkyūjo 禅文化研究所 |

| ZTJ | Zutang ji 祖堂集 |

Notes

| 1 | For discussions of the notion of “Chan school” (chanzong 禪宗), see, e.g., Foulk (1987, 1992) and McRae (2003, chap. 1). |

| 2 | The Tang Zhongyue shamen Shi Faru chanshi xingzhuang is generally believed to have been written shortly after the death of Faru in 689 and is preserved at the Huishan monastery 會善寺 on Mt. Song 嵩山 (see, e.g., Yanagida 1967, p. 35; McRae 1986, p. 85). A good annotated edition of the text can be found in the classic Shoki Zenshū shisho no kenkyū 初期禅宗史書の研究 of Yanagida Seizan 柳田聖山 (see Yanagida 1967, pp. 487–96; a reproduction of a rubbing of the stele inscription can also be found in Figure 1 in the unpaginated section at the beginning of Yanagida’s monograph). The relevant passages, some of them being quotations from earlier works, are as follows: “天竺相承,本無文字。入此門者,唯意相傳。故廬山遠法師《禪經序》云:[…] 如來泥曰未久,阿難傳末田地,末田地傳舍那婆斯。[…] 即南天竺三藏法師菩提達摩,紹隆此宗,武步東鄰之國。《傳》曰:神化幽賾。入魏傳可,可傳粲,粲傳信,信傳忍,忍傳如。[…]” (see Faru chanshi xingzhuang, line 5 to 9; Yanagida 1967, pp. 487–88); a relatively good English translation of these passages can be found in McRae (1986, pp. 85–86). On the Faru stele, see, e.g., Yanagida (1967, pp. 35–46, 490–96), McRae (1986, pp. 85–86), and Ran (1997, pp. 419–20). For more recent studies, see Cole (2009, pp. 73–114), together with a discussion of some of Cole’s readings in Robson (2011, pp. 330–34), Morrison (2010, pp. 53–55), and Ge (2012). For other sources that identify Faru as the successor of Hongren, see Ge (2012, pp. 251–52). Note that the dates given for Chan figures in this study generally follow the cross-referenced dates provided in the Zhonghua shuju 中華書局 edition of the Zutang ji 祖堂集 (see below) edited by Sun Changwu 孫昌武, Kinugawa Kenji 衣川賢次, and Nishiguchi Yoshio 西口芳男 (see Sun et al. 2007). Occasionally, however, when these dates rely on late and historically unreliable materials, I follow the dates provided in previous scholarship. The dates for Bodhidharma and Huike, for instance, are based on McRae (1986, pp. 18, 23, 278–79, n.30). |

| 3 | Presumably compiled by Du Fei 杜朏 (d.u.), probably between 716 and ca. 732. The most complete witnesses of the work found among the Dunhuang manuscripts are P.3664/3559 and P.2634. On the Chuan fabao ji, see, e.g., Yanagida (1967, pp. 47–58), Yang (1999, pp. 140–44), McRae (1986, pp. 86–88), Faure (1997, pp. 162–64), and Cole (2009, pp. 115–72). Editions are found, for example, in Yanagida (1967, pp. 559–93) or Bingenheimer and Chang (2018). See also the corresponding TEI editions of the Dunhuang manuscripts on the Database of Medieval Chinese Texts (see Anderl 2023; hereafter DMCT). An English translation of this short text can be found in McRae (1986, pp. 255–69). See also the partial and fragmented translation of Cole (2009, pp. 120–55). |

| 4 | The relevant passage in P.3664 reads as follows: “[…] the Great Master (i.e., Bodhidharma) transmitted them (i.e., the teachings) [to Huike] and then left; Huike transmitted them to Sengcan; Sengcan transmitted them to Daoxin; Daoxin transmitted them to Hongren; Hongren transmitted them to Faru; and Faru passed them on to Datong (i.e., Shenxiu). […] 大師傳之而去。惠可傳僧璨,僧璨傳道信,道信傳弘忍,弘忍傳法如,法如及乎大通。” (P.3664r, 520–21 in Bingenheimer and Chang 2019a; see also the translation in McRae 1986, p. 257). As evidenced by this excerpt, according to the Chuan fabao ji, the teachings were not transmitted (chuan 傳) by Faru to Shenxiu but were “passed on” or “ceded to” (ji yu 及乎) him. This expression is clarified by the end of Faru’s entry in the Chuan fabao ji where he exhorts his students to go and study with the meditation master Shenxiu of the Yuquan monastery in Jingzhou after his passing away (“又曰: ‘而今已後,當往荊州玉泉寺秀禪師下咨稟。’”, P.3664r, 603–4; see also the translation in McRae 1986, p. 265). On Shenxiu, see, e.g., McRae (1986, pp. 44–56) and Faure (1997, pp. 13–36). Throughout the paper, Dunhuang manuscripts are referenced as “Abbreviated pressmark followed without space by an indication of whether the text is found on the recto (r) or the verso (v) of the manuscript, line.character.” A hyphen indicates a range. For example, “P.3664r, 520.01” corresponds to Pelliot chinois 3664 recto, line 520, character 01 (i.e., da 大); “P.3664r, 520–21” corresponds to Pelliot chinois 3664 recto, line 520 to 521. |

| 5 | Presumably compiled by Jingjue 淨覺 (683–ca. 750), perhaps between 713 and 716 or in the early eighth century. The most complete witnesses of the work in Chinese found among the Dunhuang manuscripts are P.3436 and S.2054. On the Lengqie shizi ji, see, e.g., Yanagida (1967, pp. 58–87), McRae (1986, pp. 88–91), Faure (1989, 1997, pp. 160–76, 226, n.1), Yang (1999, pp. 132–40), Barrett (1991), Cole (2009, pp. 173–208), and van Schaik (2018, pp. 54–93). An annotated edition of the preface of the text can be found in Yanagida (1967, pp. 625–37). Recent editions of the Chinese Dunhuang manuscripts are found in Bingenheimer and Chang (2018). See also the corresponding TEI editions on the DMCT (Bingenheimer and Chang 2019b). A good annotated French translation is found in Faure (1989, pp. 87–182) and a more recent English translation was made by Sam van Schaik (2018). On Jingjue, see, e.g., Yanagida (1967, pp. 87–100), Faure (1989, pp. 9–35; 1997, pp. 130–44), and van Schaik (2018, pp. 88–93). On the composite and layered nature of the text, see McRae (1986, pp. 90–91) and Faure (1989 pp. 39–41, 73–79; 1997, pp. 167–73). On the Tibetan version of the text (IOL Tib J 710), see van Schaik (2015, chap. 4; 2018, pp. 86–87). |

| 6 | See, e.g., McRae (1986, pp. 89–90) and Foulk (1992, pp. 21–22, 30, n.14). The relevant passages in P.3436 (hereafter cited from Bingenheimer and Chang 2019b) are typically found at the beginning of the sections that compose the text and which are organized according to generations, from the first to the eighth. Guṇabhadra’s transmission to Bodhidharma is given as follows: “As for the second [generation], the Tripiṭaka master Bodhidharma of the Wei dynasty succeeded Tripiṭaka [master] Guṇabhadra 第二,魏朝三藏法師菩提達摩,承求那跋陀羅三藏後。” (P.3436r, 110–11; see also P.3436r, 468–70; S.2054r, 111). A similar phraseology is used for Huike (P.3436r, 156), Sengcan (P.3436r, 204), Daoxin (P.3436r, 231), and Hongren (P.3436r, 377). Regarding the seventh generation, the relevant textual unit mentions two figures along Shenxiu, namely Xuanze 玄賾 (d.u.) and Hui’an 慧安 (ca. 581–708) (see P.3436r, 422–23). The Lengqie renfa zhi 楞伽人法志—a nonextant text ostensibly authored by Jingjue’s master, Xuanze—is subsequently quoted to reiterate that Shenxiu received the transmission of the “Chan teachings” (chanfa 禪法) from Hongren (P.3436r, 425–27). This special status accorded to Shenxiu is further confirmed by the fact that in the eighth generation, the Lengqie shizi ji lists four individuals—namely, Puji 普寂 (651–739), Jingxian 敬賢 (660–723), Yifu 義福 (658–736), and a certain meditation master Lantian Yushan Hui 藍田玉山惠禪師 (d.u.)—as successors of Shenxiu (see P.3436r, 460–62), although this passage might in fact be a later addition (see Faure 1989, p. 179, n.1; 1997, p. 207, n.33). The Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大蔵経 and CBETA editions do not properly mark the segmentation of this eighth section (see respectively T2837, vol.85, p.1290, c, ll.13-26, and T85, no. 2837, p. 1290c13) probably because, in P.3436, this new section begins after a full line. For other sources that identify Shenxiu as a disciple of Hongren, see Ge (2012, p. 252). |

| 7 | Zhang Yue, in his Tang Yuquan si Datong chanshi beiming (bing xu) 唐玉泉寺大通禪師碑銘(並序) preserved in the Quan Tang wen 全唐文 (hereafter QTW) 231, gives in order Bodhidharma, Huike, Sengcan, Daoxin, Hongren, and Shenxiu (QTW 231, 01.13–02.01). Li Yong, in his Songyue si bei 嵩岳寺碑 preserved in QTW 263, gives Bodhidharma, Huike, Sengcan, Daoxin, Hongren, Shenxiu, and Puji (QTW 263, 15.17–18). The same lineage appears in his extensive epitaph for Puji (in a citation attributed to Puji himself) titled Dazhao chanshi taming 大照禪師塔銘 and preserved in QTW 262 (see QTW 262, 07.08–10). Li Hua, in his Gu Zuoxi dashi bei 故左溪大師碑 preserved in QTW 320, gives a more inclusive but unusual account of several Chan branches such as the Northern school (beizong 北宗), the Southern school (nanzong 南宗), and the Niutou 牛頭 school—although not explicitly labeled Niutouzong 牛頭宗. This tradition, Li Hua reports, began when the Buddha transmitted the “dharma of the mind” (xinfa 心法) to Mahākāśyapa 摩訶迦葉, after whom twenty-nine generations succeeded each other up to Bodhidharma (QTW 320, 01.17–02.05). On this stele by Li Hua and its importance for Chan and Tiantai 天台, see Yanagida (1967, pp. 136–148), Penkower (1993, pp. 182–84), and Ibuki (2020). For an overview of early conflicting lineage claims about the sixth and seventh patriarchs, see Ran (1997) and Ge (2012). See also the even more comprehensive overview of Morrison (2010, pp. 51–87), although the section relies heavily on secondary scholarship and there are inevitable issues in the details. Throughout the paper, I use the following referencing format for sources other than Dunhuang manuscripts: “Title of text fascicle number, page.line.character.” The use of a hyphen indicates a range. For example, “QTW 231, 01.13.12” corresponds to fascicle 231 of the Quan Tang wen, page (in this case, zhang 張 or “printing surface”) 01, line 13, character 12 (i.e., ren 忍); “QTW 231, 01.13–02.01” corresponds to fascicle 231 of the Quan Tang wen, from page (zhang) 01, line 13, to page (zhang) 02, line 01. |

| 8 | The BLZ is also known under the more complete titles Da Tang Shaozhou Shuangfengshan Caoxi Baolin zhuan 大唐韶州雙峰山曹溪寶林傳 and Shuangfengshan Caohouxi Baolin zhuan 雙峰山曹侯溪寶林傳. The first title is found in a catalog by Ennin 圓仁 (ca. 794–864) (see Yanagida 1967, p. 351) and the second is used in the partial Jinzang 金藏 woodblock edition (see BLZ 2, 01.02 in Zhonghua dazangjing bianji jubian 1994, vol. 73, p. 610). In traditional accounts, the text is said to have been compiled by a certain Zhiju 智炬 (or Huiju 慧炬) (d.u.) and completed in the seventeenth year of the Zhenyuan 貞元 era of the Tang 唐 (801) (see, e.g., Yanagida 1967, p. 351, Shiina 1980b, p. 234). On the BLZ, see, e.g., Yanagida (1967, pp. 351–418), Yang (1999, pp. 576–91), Jia (2011), Jorgensen (2005, pp. 640–51), and Robson (2009, pp. 274–76, 297–99). On the BLZ’s debated authorship and composition date, see specifically Jorgensen (2005, pp. 644–49), Jia (2006, pp. 84–89; cf. Jia 2011), and Robson (2009, pp. 297–99). The extant witnesses of the 10-juan BLZ are the Jinzang edition (juan 1 to 5, and 8, with missing portions), and the Shōren Temple 青蓮院 manuscript edition (juan 6) (see Yanagida 1967, p. 351). In other terms, juan 7, 9, and 10 are currently lost. However, quotations from lost sections of the BLZ were discovered in later sources such as the Yichu liutie 義楚六帖, the Beishan lu zhu 北山錄注, the Zuting shiyuan 祖庭事苑, or the Keitoku dentō shōroku 景德傳燈鈔錄. On the surviving fragments of the BLZ, see Shiina (1980a, 1980b, 2000). On the BLZ’s hagiographic account of Huairang and the corresponding passages in early lamp records, see my forthcoming paper in the proceedings of the international conference “How Zen Became Chan: Pre-modern and Modern Representations of a Transnational East Asian Buddhist Tradition” (29–31 July 2022), in collaboration with Yale University (“Nanyue Huairang 南嶽懷讓 (d. 744) in Chan histories: On the textual fragments of the Baolin zhuan 寶林傳 quoted in the Keitoku dentō shōroku 景德傳燈鈔錄”). |

| 9 | Unfortunately, the entry of Huineng does not survive among the two extant witnesses of the BLZ. However, several passages in later sources that quoted from the BLZ strongly suggest that he was regarded as the legitimate successor of Hongren. See fragments no. 46, 47, 48, and 50 cited in Shiina (1980b, p. 246). The view espoused in Huineng’s entry in later Chan records such as the Zutang ji (see below) likely reflects the content of his entry in juan 10 of the BLZ. For early sources that identify Huineng as the successor of Hongren, see Ge (2012, p. 252). |

| 10 | |

| 11 | For the relevant excerpt in the Putidamo Nanzong ding shifei lun, see, e.g., P.2045r, 34–35 in Lin et al. (2017). For the relevant passage in one of the Dunhuang versions of the Liuzu tanjing, see, e.g., Yampolsky (1967, pp. 176, 二一六 [216]) and T48, no. 2007, p. 344a17-23, both taking Or.8210/S.5475 as their base text. The fact that the BLZ likely adopted this narrative is further suggested by Huiguan’s 慧觀 (d.u.) preface to the Quanzhou Qianfo xinzhu zhuzushi song 泉州千佛新著諸祖師頌 (Or.8210/S.1635) of Wendeng 文僜 (d. 972), at the time known as Qianfo Deng 千佛僜 or simply Qianfo, and the praise (zan 讚) composed by Wendeng for Huineng, both of them influenced by the BLZ (see, e.g., Kinugawa 2010). The first passage is as follows: “Since the lamp of the patriarchs was successively entrusted, from [Mahā]kāśya[pa] to Caoxi, in total there were thirty-three patriarchs. [Then], after the robe of faith [ceased to be transmitted], it (i.e., the transmission of the lamp) extended to several individuals. 自祖燈相囑,始迦葉終曹溪,凡三十三祖,信衣之後,迨數人。” (S.1635r, 3–4). The relevant line of Wendeng’s praise reads: “Although he did not entrust the robe, flowers blossomed throughout the empire. 衣雖不付,天下花開。” (S.1635r, 77). In other words, Huineng presumably had not one but numerous dharma heirs who carried on the transmission. For a recent annotated TEI edition of S.1635, see Van Cutsem (2021) on the DMCT. |

| 12 | The JDCDL, initially titled Fozu tongcan ji 佛祖同參集, was compiled by a certain Daoyuan 道原 (d.u.), possibly a disciple of Tiantai Deshao 天台德韶 (891–972), around the first year of the Jingde 景德 era (1004) of the Northern Song 北宋 (960–1127). First presented by Daoyuan at the imperial court around 1005 or 1006, the text was edited by Yang Yi 楊億 (974–1020), Li Wei 李維 (d.u.), Wang Shu 王曙 (963–1034), and other officials, a process that was completed around the second year of the Dazhong xiangfu 大中祥符 era (1009), before it eventually entered the Buddhist canon in 1011. See, e.g., Yang (2006, pp. 70–72) and Feng (2014, pp. 120–25). On the JDCDL’s compiler and textual history, see Feng (2014, pp. 99–147). |

| 13 | Foulk (1992, p. 18). On yet another lineage championed in the late eighth-century Lidai fabao ji 歷代法寶記 and the text’s socio-religious background, see the good study of Adamek (2007). |

| 14 | Reportedly answering to Pei Xiu 裴休 (791–864), Zongmi notes the following in his Zhonghua chuan xindi chanmen shizi chengxi tu 中華傳心地禪門師資承襲圖 (also known under the title Pei Xiu shiyi wen 裴休拾遺問): “As for the records composed by predecessors, they only discuss their direct ancestry. 前者所述傳記,但論直下一宗。” (X63, no. 1225, p. 31a14). On the different interpretations of the term zhuanji (or chuanji) 傳記 in the passage translated above, see Broughton (2009, p. 237, n.6). This text is introduced and translated in full in Broughton (2009, pp. 12–22, 69–100). See also Gregory (1991, pp. 15, n.28, 74, 230–31, 318–19). On the unilineal nature of genealogical claims in early Chan records and their possible connection to imperial lineages, see Jorgensen (1987). |

| 15 | I provide an overview of the conclusions of some of the more recent publications at the end of Section 2. |

| 16 | |

| 17 | For methodological reflections on the functions of lineages and lineage diagrams in Chan, see, e.g., McRae (2003, pp. 1–11) and the interesting discussion of lineages as models by Steffen Döll (2018, pp. 150–66, 174–75). For an overview of the antecedents to and the development of Chan lineages, see Morrison (2010, pp. 13–87). See also the recent contribution by John Kieschnick (2022, chap. 5) on the genre of genealogical histories in the Chan and Tiantai contexts. |

| 18 | The Zhaoqing monastery was reportedly located on Mt. Qingyuan 清源山 in present-day Fengze district 豐澤區 of Quanzhou city 泉州市, Fujian province 福建省. On Wendeng’s preface to the ZTJ, see, e.g., Yanagida (1964, pp. 13–18) and Van Cutsem and Anderl (2021). |

| 19 | On Xuefeng and his disciples, see, e.g., Yanagida (1953, pp. 38–39, 44), Ishii (1986, pp. 171–73), Welter (2006, pp. 90–110), and Brose (2015, pp. 50–62, 143–45). See also Jia (2006, p. 118). |

| 20 | Six passages in the first and second juan of the ZTJ identify the present as the tenth year of the Baoda 保大 era (952) of the Southern Tang 南唐 (937–976) (see, e.g., Yanagida 1953, p. 35). These are found in the entries of Śākyamuni 釋迦牟尼, Bodhidharma, Huike, Sengcan, Hongren, and Huineng. The exact references of these passages and a translation of the excerpt in Śākyamuni’s entry is provided by Van Cutsem and Anderl (2021, p. 11, see also p. 30, nn.100–02). It is based on this identification of the present with the tenth year of the Baoda era that Japanese scholars have assumed that the ZTJ, as initially compiled by Jing and Yun and prefaced by Wendeng, was completed around 952. See, e.g., Yanagida (1980–1984, vol. 3, pp. 1579, 1584) and Kinugawa (2007, p. 945). |

| 21 | The ZTJ was identified by Japanese scholars in the early twentieth century among the extra-canonical works of the second Goryeo Buddhist canon (Kor. Goryeo Daejanggyeong 高麗大藏經) preserved at the Haein monastery 海印寺, located on Mt. Gaya 伽耶山 in South Gyeongsang province 慶尙南道. See, e.g., Yanagida (1980–1984, vol. 3, p. 1579), Demiéville (1970, p. 262), and Kinugawa (2007, pp. 933–34). |

| 22 | See, e.g., Kinugawa (1998, p. 122). The exact nature of the two earlier versions of the ZTJ is not yet well understood but suggestions have been made by Kinugawa (2007, p. 945; 2010, pp. 88–89) and Van Cutsem and Anderl (2021, pp. 11–15). |

| 23 | Regarding Huineng’s successors, the fragments cited by Shiina come for the most part from the Keitoku dentō shōroku, a manuscript that likely dates back to the Muromachi 室町period (1336–1573) and which is preserved at the library of Komazawa University 駒澤大学 in Tōkyō 東京. Quotations from the BLZ’s tenth juan are found in fascicles (kan 卷) five and six (see Shiina 1980b, pp. 248–49). |