Abstract

Mahāyāna and Theravāda are the two major traditions of Buddhism in contemporary Asia. Although they share many similar teachings, there are long-standing disputes between their respective sets of adherents, touching on doctrine, ritual, religious practices, and the ultimate goal, among other matters. Drawing on fieldwork conducted in Yangon and Mandalay, this study explores gender’s role in the position of Sino-Burmese Mahāyāna bhikṣuṇīs in the sociocultural context of Theravāda-majority Myanmar, where the full bhikṣuṇī lineage of Theravāda Buddhism has died out. Its findings, firstly, shed light on how the local Theravāda ethos inevitably affects Sino-Burmese Mahāyāna nuns’ positions and experiences of religious- and ethnic-minority status. Secondly, they demonstrate the gender dynamics of Sino-Burmese nuns’ interactions both with indigenous Burmese monks and Myanmar’s ethnic-Chinese laity. As such, this research opens up a fresh perspective on these nuns’ monastic lives, to which scant scholarly attention has hitherto been paid. Specifically, it argues that while Sino-Burmese nuns are subjected to “double suffering” on both gender and ethnoreligious minority grounds, they play an important role in shaping the future of Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism by educating the next generation of monastics and serving the religious needs of the wider Sino-Burmese community in Myanmar.

1. Introduction

The history of the world has largely been written through men’s eyes, such that we effectively have a male version of events (Sarao 2004, p. 1), and this is no less true of the history of women’s religious experience (Knott 1995, p. 199). A connected problem is what Rita Gross (2005, p. 18) has called “inadequate and unbalanced” research on women and religion due to androcentrism in academia. Though this problem has diminished since Gross wrote, the accomplishments of female Buddhist monastics are still often ignored by Western scholars, who have typically been more interested in the Buddha’s hesitation about establishing the nuns’ order than in the nuns’ achievements (Gross 1993, p. 30). Because of the increasingly important roles played by women in political, economic, and social life over the past century, the subject of women has assumed greater importance for various faiths, particularly in the West. I. B. Horner’s classic 1930 book Women under Primitive Buddhism alerted a wide audience to issues around women in Buddhism. Since then, increasing numbers of feminists and other scholars have researched and questioned the positions of nuns and other women in Buddhist texts. For example, there is an ongoing, heated debate about the re-establishment of bhiksuni ordination in the Theravāda and Tibetan traditions,1 involving not only the various schools of Buddhism but also academics, particularly with regard to the complex issues around the rules in the Vinaya (Buddhist disciplinary texts) and the legitimacy (or not) of ordination. Various studies, including many based on empirical fieldwork, have explored non-fully ordained contemporary Buddhist nuns’ experiences and perceptions of the controversy surrounding this ordination movement. Such nuns are known as maechi2 in Thailand, as thilá-shin3 in Myanmar, and as eight/ten-precept nuns in Sri Lanka (Bartholomeusz 1994; Cheng 2007; Falk 2007; Carbonnel 2009; Seeger 2009; Kawanami 2013; Salgado 2013). Their status within the religious system is at best ambiguous, and at worst, fully subordinates them to monks, as performers of menial services for them. Nevertheless, the voices of these and other Southeast Asian Buddhist women are gradually being heard and understood, and particularly so in the context of the debate on the validity and (re-)establishment of full ordination for nuns in Theravāda tradition, where the bhikṣuṇī lineage has died out. In short, ethnographic research on Theravāda Buddhist women in Thailand, Myanmar, and/or Sri Lanka, has been extensive and of a high quality.

However, various religious minority communities in mainland Southeast Asia are generally ignored, not only by the local majority religions but also by academics. As Jack Meng-Tat Chia (2020, p. 8) recently pointed out, the root of this problem is that scholars tend to narrowly identify the category of “Southeast Asian Buddhism” as Theravāda Buddhism. Therefore, McDaniel (2010); Hansen (2014) and Chia (2020) advocated looking beyond the Theravāda tradition when studying Southeast Asian Buddhism. By focusing on Mahāyāna bhiksunis in contemporary Myanmar4 who are Sino-Burmese, i.e., people of Chinese descent who identify with Burma,5 this paper not only answers that call but extends this academic conversation to deeper questions about the nature of Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism at its margins, considered specifically as a local minority immigrant religion in a Theravāda-majority society and culture.

The Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism of Myanmar is regarded as an immigrant religion, having been brought there from Mainland China in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. In general, wherever there are Chinese people, the sacred footprint of Buddhism can be discerned (Lai et al. 2008, p. 96). As noted by Meei-Hwa Chern (2009, p. 61),6 monastics have played a critical role in the history of cultural interaction between China and Southeast Asia; wherever Chinese monks go to live, monasteries or temples are likely to be established, and these sites then serve as magnets for groups of Chinese immigrants.7 Overseas Chinese, monastics and laity alike, have played key roles in the spread of Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism into various Southeast Asian countries, as well as in this religious tradition’s further development there (e.g., Tan 2011; Ashiwa and Wank 2005; Chern 2009; Hue 2013; Dean 2018; Chia 2020). On the one hand, this spread of Buddhism to new places resonates strongly with Jan Nattier’s (1997, p. 78) category of “Baggage Buddhism”, which is “deliberately monoethnic in membership at the outset” because it operates not only for religious purposes but also as a community’s support network. On the other hand, the transplantation of Mahāyāna Buddhism into Theravāda countries via immigration or commerce has inevitably resulted in unprecedented cross-traditional communication, conflicts, adaptation, and/or integration. Given the marked differences between these two Buddhist traditions in terms of both ritual and the religious practices of monastics, it is especially worth examining overseas Chinese nuns’ religious and minority experiences of living in the sociocultural context of Theravāda-majority Myanmar.

While the issue of Mahāyāna–Theravāda border-crossing is a topic of strong interest in Buddhist Studies, only a limited amount of ethnographic work on Chinese Buddhism in regions of the world beyond the traditional East Asian Mahāyāna territories has been conducted.8 Research engagement with Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism in Myanmar has been especially scant, in part as a result of that country’s isolationism up until 2010. When it opened its doors to the outside world after five decades of army-imposed hibernation, a major window of opportunity opened for scholars to empirically investigate its Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhist community. Some of the ensuing research has sketched the outlines of how Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism changed within and became integrated into the Theravāda contexts of Burmese society before the military coup that established Myanmar’s current regime in 2021. These include a case study of Chinese Buddhism in Myanmar by Feng-Yng Wu (2006), a Buddhist nun from Taiwan who has researched the historical development and difficulties of Chinese Buddhist monasteries in Yangon; an exploration of the past and present interdependence of Chinese Buddhism and the Myanmar Chinese, by Bingxian Chen and Shuai Feng (Chen and Feng 2016, pp. 57–62); and an examination of how Mahāyāna and Theravāda Buddhism affect the Sino-Burmese’s laity religious life and ethnic identity in Mandalay via different degrees of localisation and acculturation, by Ying Duan (2015, pp. 43–71). However, the above-cited studies’ treatment of Buddhist religious life leaves much to be desired: in some cases, only relying on out-of-date sources for Sino-Burmese monks’ experiences or presenting general views of ritual and religious practices. Moreover, none of these works can be said to constitute theoretically informed explorations of the contextual factors affecting Sino-Burmese monastics’ experience and adaptation to local customs. In short, there has not hitherto been any sustained enquiry into how contemporary Chinese Buddhists in Myanmar, considered an ethnoreligious group, have understood and enacted localisation.

In focusing on Buddhist women, it is important not to allow the pendulum to swing too far and overlook first-generation Chinese monks’ contribution to spreading and developing Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism in Theravāda contexts. Most Chinese Mahāyāna monks in Burma in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries engaged in short-term activities such as visits to holy sites, rather than seeking to propagate Buddhism, and their historical footprint was therefore small.9 For instance, the Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon was, and remains, a place of pilgrimage for many Chinese monastics. Chinese Buddhist monasteries were thus built for the temporary accommodation of a growing number of Chinese pilgrim monks near Shwedagon. Despite their limited character, the existence of these dedicated spaces for Chinese practitioners enabled the spread of the Mahāyāna tradition in Burma (Wu 2006, pp. 16–18).

Feng-Yng Wu (2006, pp. 16–17) compiled a list of the Chinese monastics who came to Burma during the Qing Dynasty and early republican period, together with their reasons for doing so. The majority of these individuals who made pilgrimages from China to Shwedagon Pagoda or did religious business in Myanmar were monks rather than nuns. Given that most Buddhist monasteries in Yangon were built by first-generation monks in the early twentieth century, it is somewhat surprising that the individuals currently managing Buddhist institutions in Yangon and other areas of Myanmar include some second-and third-generation Sino-Burmese nuns (ibid., pp. 50–51). Some nuns took over the monasteries from their male masters after the latter’s deaths (e.g., at Luohan Si and Zangjing Lou), whereas some others established nunneries on their own initiative (e.g., at Zhonghua Si and Miaoyin Si). This could be connected to the fact that, according to my fieldwork observations, Sino-Burmese nuns in contemporary Myanmar outnumber Sino-Burmese monks by five to one (ca. 100 vs. ca. 20).10 One of the most prominent of these nuns, Ven. Hongxing (who will be further discussed below), was sent from Myanmar to Taiwan for advanced monastic education, and some talented young nuns who are motivated to stay in monastic circles have followed suit. Of these, some returned to Myanmar, aiming to foster the future growth of the Sino-Burmese monastic community and Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism more generally there.

While the Mahāyāna tradition has minority status in Myanmar, Sino-Burmese nuns’ sheer numbers, as well as their educational standards, have risen in recent decades in a way that resonates with Taiwanese nuns’ circumstances.11 Additionally, junior Sino-Burmese nuns are often sent to Taiwan for advanced education. Yet, despite these connections and similarities, and the fact that the Buddhist nuns of Taiwan have been the subject of considerable scholarly attention, Sino-Burmese nuns’ religious positions and experiences in contemporary Myanmar have hitherto been largely unexplored. Therefore, Sino-Burmese Mahāyāna bhikṣuṇīs have been selected as the main research subjects of this study, which will attempt to capture bhikṣuṇīs’ attitudes and approaches toward their settlement in the host country and to understand how these relate to their monastic identities and social recognition.

This study addresses two main research questions:

- How does the local ethos affect Sino-Burmese Mahāyāna nuns’ positions and experiences as religious minority members in a Theravāda host country with no recent history of a bhikṣuṇī lineage? Specifically, are they recognised as bhikṣuṇīs, or merely as eight-precept nuns in the eyes of the local monastics and laity?

- What are contemporary Sino-Burmese nuns’ general perceptions of, and practices involving, their gender relationship both with indigenous Burmese monks and Myanmar’s ethnic-Chinese laity? Specifically, are the eight gurudharma rules12 reinforced when Mahāyāna nuns interact with male Theravāda colleagues (e.g., to bow or not to bow)? And what are Sino-Burmese Mahāyāna bhikṣuṇīs’ roles in overseas Chinese communities?

When studying Chinese Buddhism or any other Chinese religion, applying a combination of historical, textual, and fieldwork approaches can be very rewarding. As Daniel Overmyer (1998, p. 4) has pointed out, “knowledge of history and texts can enrich field observation, and field observation can often provide a sense of context for past practices”. Following Overmyer’s recommendations, I adopted interviews and observation as my key qualitative methods, supplemented by analyses of historical writings utilised by Sino-Burmese nuns and monks in Yangon and Mandalay.

While bhikṣuṇīs of all status levels were this study’s primary interviewees, the viewpoints on Buddhist nuns held by the Sino-Burmese laity were also collected via interviews and informal conversation, for the sake of comparison and to gain as complete a picture as possible of the current situation. A total of twelve face-to-face interviews were conducted in eleven Chinese Buddhist institutions in Myanmar.13 One formal interview with a senior Hokkien Sino-Burmese layman and several informal conversations with ritual participants were also recorded as corroboration of the monastics’ perspectives.

Theravāda Buddhism is the predominant religion in Myanmar, where there are around 500,000 monks and 75,000 nuns.14 The percentage of lay Theravāda Buddhists among the national population is likewise quite high, at around 88%, according to the U.S. State Department’s 2020 International Religious Freedom Report.15 It is also a religious landscape in which Burmese laypeople have traditionally spent fairly large proportions of their incomes on Buddhist donations (Sakya 2011, p. 140). In Myanmar, Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism is clearly a minority religion, but it nevertheless has given rise to a rich monastic scene. Indeed, it would be very difficult, or perhaps impossible, to conduct fieldwork in all the Chinese monastic institutions there. Therefore, I selected Yangon and Mandalay as my major sites for fieldwork-data collection, not only because the majority of the ethnic-Chinese populations in these cities are descendants of early overseas Chinese migrants from Fujian, Guangdong16 or Yunnan,17 but also because many Chinese Buddhist temples were built to meet the needs of first-generation Chinese immigrants there; anyone researching Chinese Buddhism in Myanmar can obtain a major ‘head start’ by focusing on those two cities initially. As such, the present work can be best described as a multiple-case study. Widening one’s range of fieldwork sites is more likely to yield a balanced overview of one’s subject matter and can allow comparisons of nuanced differences among them. Nevertheless, Stake (2005, p. 451) noted that the sample size in a multiple-case study is usually “much too small to warrant random selection”. I therefore selected my target Chinese monasteries purposively to provide the requisite variety and balanced overview, and perhaps more importantly in light of my research, focus on nuanced, localised differences in religious practices. Thus, a total of seven monasteries in Yangon and four in Mandalay were chosen, as shown in Table 1. Most of the fieldwork data were collected in 2018 and 2019, i.e., before the military coup that established Myanmar’s current regime.

Table 1.

Interview sites, by region.

Thematic analysis was applied to nuns’ interview responses and to their independently expressed views on their religious lives in present-day Myanmar. This approach, which has been widely used with qualitative data, is “for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data” (Braun and Clarke 2006, p. 79), and can be summed up as emphasising “what is said rather than […] how it is said” (Bryman 2008, p. 553). I have followed the process of thematic analysis recommended by Braun and Clarke (2006).

In particular, in light of my research questions and aims, I have categorised these fieldwork data into three distinct dimensions: (1) status, i.e., whether a person is recognised as a bhikṣuṇī or not; (2) interactions and relationships among Burmese monks, Sino-Burmese monks, and Sino-Burmese nuns; and (3) the role of Sino-Burmese bhikṣuṇīs in the overseas Chinese community. Each of these three dimensions is explored in detail in its own section below.

2. Being Recognised as Bhikṣuṇīs or Not

Before proceeding to my fieldwork results, it will be helpful to the reader to have some brief background on female monastics in Myanmar. Around two and half millennia ago, the order of nuns was established when the Buddha allowed women to join the Buddhist monastic community. Nevertheless, most nuns in various Buddhist traditions have never received the same rights as their male counterparts, and down the ages, nunneries have been more vulnerable than monks’ communities to political and economic problems. As a result, with the exception of the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya, which is still active in Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism, all traditions for bhikṣuṇīs’ lineages have become extinct, including the Pāli tradition in Southeast Asia and the Mūlasarvāstivādavinaya tradition in Tibet.18 Thilá-shin in Myanmar, like Thai maechis, live in nunneries according to the precepts of a novice nun, shaving their heads and wearing pink robes; but they are not ordained as bhikṣuṇīs, leaving their status quite ambiguous:

On the one hand, Buddhist nuns in Myanmar endorse one of the typical traits of monastic living in the Theravāda tradition: they live on the gifts and alms they receive from lay people19 […]. On the other hand, nuns in Myanmar appear closer to laywomen when their relationship with monks in their role as donor [for merit-making] is considered.(Carbonnel 2009, p. 267)

Crucially, many Burmese nuns have appeared to be formally subordinated to monks, performing whatever daily chores and other menial services they require (Kawanami 1990). Therefore, it is worth investigating whether Sino-Burmese Buddhist nuns in contemporary Myanmar have gained social recognition and respect for their status as bhikṣuṇīs, despite having been ordained in an essentially foreign tradition of Dharmaguptaka Vinaya.20

My fieldwork data suggest that, owing to more mutual interactions among Buddhists in Taiwan, Mainland China, and Myanmar, whether via religious activities such as the worship of the Buddha Tooth Relic, philanthropic activities, or cross-traditional exchanges by monastic delegations, the relationship between Theravāda and Mahāyāna Buddhism is better now than in the past, albeit with room for further improvement remaining (Chiu 2020). Additionally, some of my informants told me that Burmese laypeople expressed acceptance and even respect for Chinese Mahāyāna monastics, in part due to Myanmar’s newfound openness to the world and the concomitant development of information networks. Notably, however, they said that Chinese bhikṣuṇīs’ identities were not well recognised or accepted in the sociocultural context of Theravāda-majority Myanmar:

Bhikṣuṇī (A): Chinese bhikṣuṇīs are seen as eight-precept nuns in Myanmar. Most Sino-Burmese laypeople also see things that way. Only those few members of the laity who often come to Chinese temples know that we are bhikṣuṇīs […]. The full bhikṣuṇī lineage of Theravāda Buddhism died out, so Burmese people do not accept bhikṣuṇīs of the Chinese Mahāyāna tradition. Besides, Burmese society regards men as superior to women[.]

Bhikṣuṇī (B): There are no [Theravāda] bhikṣuṇīs in Myanmar. Burmese people generally see Chinese bhikṣuṇīs as ten-precept nuns or śikṣamāṇās, instead of as bhikṣuṇīs, because they do not understand [their true status]. But some Burmese people may know we are bhikṣuṇīs if they often come to Chinese temples or have more interactions with us.

Bhikṣuṇī (C): I was thought to be a precept nun when I went out wearing a Chinese Buddhist robe. Local people knew more Burmese precept nuns, and when I was with them they asked me whether I was a precept nun or not [due to my robe’s different style and colour].

Bhikṣuṇī (D): People see me as a Chinese bhikṣuṇī.

Senior layman: There are no bhikṣuṇīs in the Theravāda society of Myanmar, only eight/ten-precept nuns […]. The local ethos also affects Sino-Burmese people’s thinking[.]

These excerpts raise some interesting points. First, we cannot overlook how contextual factors influence local Burmese people’s perceptions of Chinese Buddhist nuns in Myanmar. The informants in question made it clear that Sino-Burmese nuns are widely assumed to be precept nuns,21 even though they have been ordained as bhikṣuṇīs based on the Dharmaguptaka tradition. Unsurprisingly, even some Sino-Burmese believers in Chinese Buddhism saw female monastics through this Theravāda lens. On the one hand, it would be inappropriate to condemn these people’s ‘ignorance’ of bhikṣuṇīs (or indeed the style and colour of Chinese Buddhist robes), given that Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism is a minority religion that has developed quite slowly over the decades since it first arrived in Myanmar (Chiu 2020). Conversely, most laypeople in Taiwan and Mainland China do not understand Theravāda Buddhism and may inevitably ‘upgrade’ the status of Burmese eight/ten-precept nuns to the more familiar one of bhikṣuṇī. In this sense, the respective contexts and ethos of Theravāda and Mahāyāna Buddhism crucially impact people’s perceptions and recognition of female monastics’ identity and status. On the other hand, it should also be borne in mind that revolutionary change to a long-lasting tradition or custom is seldom easy or straightforward; previous research and my fieldwork data suggest that shifting Burmese public opinion to acceptance of female monastics as bhikṣuṇīs would be challenging and controversial. Ma Thissawaddy, a Burmese nun who was ordained as a bhikṣuṇī outside Myanmar, caused serious unrest in the Burmese saṃgha and society (Kawanami 2007, pp. 232–34). In her tragic case, little or no support came from Burmese nuns or laypeople; indeed, the Burmese saṃgha decried attempts to revive the bhikṣuṇī lineage as being “against the historical tradition of Burmese Buddhism” (ibid.). Given that Ma Thissawaddy failed to achieve recognition of her status despite being a member of Myanmar’s ethnolinguistic majority, it is reasonable to surmise that Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhists would have no more success than she did.22 Most importantly, we cannot deny that the ethnoreligious boundaries between an in-group made up of Burmese monastics and an out-group consisting of Chinese ones is clearly defined, partially because Mahāyāna and Theravāda practitioners hold imaginary versions of each other, which are very powerful, but not based on actual knowledge of the other tradition’s distinctive teachings and practices. As Gustaaf Houtman (1999, p. 165) succinctly put it: “All that comes from outside is ‘bad’ influence, and ‘alien cultural influences’ are highly undesirable”. This statement resonated strongly with my interviewee’s comment that most Burmese people cannot accept and/or recognise bhikṣuṇīs of the Chinese Mahāyāna tradition due to Myanmar’s historical monastic legacy.

Second, while most of my fieldwork data showed that Sino-Burmese bhikṣuṇīs are widely perceived as precept nuns in Burmese contexts, one of them, Ven. Hongxing, explicitly told me that people saw her as a bhikṣuṇī. The abbess of Luohan Si, she is well-known among adherents of both the Mahāyāna and Theravāda traditions and particularly so in Yangon. It is thus worth briefly sketching her biographical information. Ven. Hongxing 釋宏興 (b. 1960) received her full ordination in Shifang Guanyin Si, Yangon, in 1979. In 1984 she went to Bangkok, Thailand to study advanced Buddhism at Wat Paknam Bhasicharoen (水門寺), and then studied at Yuan Kuang Buddhist College (圓光佛學院) in Taiwan. After graduation in 1992, she went to Sri Lanka to study Literature at the University of Kelaniya. In 2000 she came back to Myanmar to study at Maha Santi Sukha Buddha Sasana Centre. After graduating from there in 2002, she was assigned to teach at Shifang Guanyin Si, and visited India on a pilgrimage. This was followed by visits to Singapore and Malaysia in 2003. After Ven. Hongxing was invited to take over as prior (jianyuan監院) at a Buddhist temple in Bangkok, she decided to stay in Myanmar due to the shortage of teachers in Chinese Buddhist saṃgha education. In the same year, she commenced her work as abbess of Luohan Si. Due in part to her almost unparalleled Buddhist training all over Myanmar and in Taiwan, Thailand, and Sri Lanka, she is considered a monastic of extraordinary ability (Wu 2006, p. 37). According to my fieldwork observations in her nunnery and other religious events, Ven. Hongxing indeed plays an important role in local Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism for religious propagation among the laity and in saṃgha education for the next generation. Unlike other nuns I interviewed, she expressed her empowerment by noting that other people see her as a bhikṣuṇī. Nevertheless, it would be hard to deny that she would have the power and authority to contribute even more if she were male, in the monk-dominated context of Myanmar. Unlike some Sino-Burmese nuns, who tend to focus on self-cultivation in their own nunneries, Ven. Hongxing’s profound knowledge and wide experience have not only brought her a good reputation and high status but have also provided her with more connections to Burmese monks, useful when it comes to collaboration on certain cross-traditional events that will be further discussed below. While the present research did not seek to answer the question of whether indigenous Burmese monks recognised Ven. Hongxing as a bhikṣuṇī or not, her case provides a fresh perspective i.e., that it is not unheard of for a Sino-Burmese female monastic to be able to pursue advanced studies in various countries, return to Myanmar to propagate Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism there, and in the process win people’s recognition and respect. Most importantly, her story is not only hopeful from the perspective of those wishing for the further development of Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism but also established an influential model of self-reliance for next-generation nuns in monk-dominated countries.

As noted above, in Theravāda sociocultural contexts, Sino-Burmese nuns who have received full precepts are generally seen as having a lower status than they perceive themselves to have e.g., in the case of Myanmar, they are treated as thilá-shin instead of as bhikṣuṇīs. From my secular perspective, Sino-Burmese nuns’ reactions and attitudes toward this phenomenon were unexpected. In other words, ordinary people generally guard their own status and secular titles jealously, but my nun informants’ responses were calm and revealed no inclination to fight for their ‘real’ monastic status:

Bhikṣuṇī (A): I am used to it [i.e., being treated as a ten-precept nun in Myanmar]. I personally do not care how others see me or what they think of me. Working hard on the road to spiritual cultivation is the important thing.

Bhikṣuṇī (B): I can’t really help it, since I live in their country [Myanmar].

Bhikṣuṇī (C): It is okay for me [to be seen as a thilá-shin]. Superficial status doesn’t matter. Cultivation is to cultivate your own self.

Against this backdrop, it is worth asking whether their position as Chinese Mahāyāna nuns, i.e., outsiders to Theravāda Buddhism, is respected by local people or not. In Yangon in the 1950s, Ven. Leguan23 commented that Burmese people did not consider first-generation overseas Chinese monks to be monastics, due to differences between those incomers’ and their local counterparts’ religious lifestyles and practices, including but not limited to robe colour, fasting after midday, and alms-begging (L. Shih 1977, p. 150). Indeed, Chinese monastics at that time seemed not to be well treated or respected in the host country (L. Shih 1977, pp. 154–55; C.-h. Shih 1931, p. 17). Therefore, I was quite curious about whether, gender factors aside, the treatment of Chinese Mahāyāna monastics in Myanmar had improved over the past half-century or so. Some of their comments relevant to this issue are reproduced below.

Bhikṣuṇī (A): Local Burmese people show respect to [Chinese Mahāyāna] monastics [while walking down the street …]. Nuns’ treatments definitely differ from monks’ due to Myanmar is a patriarchal country.

Bhikṣuṇī (B): Local Burmese people show respect to monastics by offering their seats to them on the bus, and letting them go first when buying tickets. The laity gave more respect in the past because they were more devoted then. Nowadays, some people pay less attention to politeness [toward monastics] and rules, because of modern technology […] [A] Burmese person disrespected me and then I let him know I was a Buddhist nun via proper communication.

Bhikṣuṇī (C): Local people show a certain degree of respect [to me] by kneeling down [despite thinking I am a precept nun].

Bhikṣuṇī (D): Some taxi drivers refuse to allow us to pay our fares. On some occasions, Burmese people who see Chinese nuns have given us priority, without claiming that we are not really Buddhist monastics.

Bhikṣuṇī (E): It is a fact that Chinese Buddhist monastics are not well respected in Myanmar [… but the] Sino-Burmese laity who come to Chinese temples show us due respect.

The above fieldwork data touch upon several important points regarding Sino-Burmese nuns’ relationship to the local value/norm of inherent respect for monastics in general and Burmese people’s respect in Theravāda-majority Myanmar. First, the Sino-Burmese nuns I interviewed appeared to have received better treatment and more religious recognition than first-generation Chinese monastics in Burma did in Ven. Leguan’s time, i.e., the middle decades of the twentieth century. According to my fieldwork observations in 2018, and Feng-Yng Wu’s (2006, p. 119) personal experience as a Taiwanese bhikṣuṇī in the early part of the present century, some local Burmese people in Yangon showed respect to Sino-Burmese nuns not only by offering their seats to them on buses but also by joining their palms as a respectful greeting, whether inside Buddhist monasteries or outside on the street.24

Secondly, however, we cannot overlook the fact that my interviewees had either experienced impoliteness or mentioned that people treated monks and nuns differently in their host country. Males’/monks’ predominance over females/nuns may, after all, be an important factor in Sino-Burmese nuns’ treatment in Myanmar, and one that is worth exploring more.

In broad outline, Burmese women seem relatively emancipated, and historically enjoyed a privileged position in comparison to other Asian women, marked by considerable independence of action (Mya Sein 1958). Nevertheless, women still face many injustices and inequalities under certain Burmese cultural taboos. One well-known and typical instance is the old Burmese tradition that men who pass under women’s longyi (sarongs) drying on clotheslines will lose their masculine power, known in Burmese as hpone. Additionally, women including Buddhist nuns are not allowed to approach or touch the stones or Buddha statues of some famous sacred Buddhist sites, including the Mahamuni Buddha Temple and Kyaiktiyo Pagoda, also known as Golden Rock. This religious exclusion clearly reflects a certain degree of gender prejudice toward women in Burmese culture.

Buddhist texts also fundamentally influence Burmese people’s perceptions of the sexes’ superiority or inferiority. Mya Sein, a Burmese female author and advocate for women’s equality during British rule, explicitly pointed out that Burmese people believe the next Buddha coming to this world will be male, and that for a woman to achieve this status she would first need to be reborn as a boy. This belief thus “gives men an inherent superiority” and allows them to “reach higher than women” (Mya Sein 1958). Similarly, Melford Spiro, who conducted most of his fieldwork in Burma in the 1960s, pointed out that many of his female respondents wanted to be reborn male, since men’s superiority can be manifested in various ways: “[O]nly a male can be a Buddha, males are ‘nobler than females, males have a pleasanter life than females…’” (Spiro 1970, pp. 82n–83n). On the other hand, monks as males in this complex cultural context have generally received unusually intense veneration from the Burmese laity. As Spiro noted, “[t]here is probably no other clergy in the world which receives as much honor and respect as are offered the Buddhist monks of Burma” (Spiro 1970, p. 396). Furthermore, due to being female, Burmese eight/ten-precept nuns—despite their ambivalent position between the religious and secular worlds—are subordinated to monks (Kawanami 1990; Carbonnel 2009).25 While there is a visible gap in social-status ranking and gender differences in Burmese Buddhist communities between indigenous monks and precept nuns, I would argue that Sino-Burmese nuns’ positions and experiences are subjected to what might be called “double suffering”: as female monastics, they suffer patriarchal gender inequality similar to local precept nuns, while also experiencing marginalisation due to their minority status as Mahāyāna and ethnically Chinese “pagans” living in a Theravāda-majority, Burman-majority land.

To sum up, my fieldwork data confirm that most of my bhikṣuṇī interviewees were misidentified as precept nuns by local people, chiefly because of the lack of bhikṣuṇī lineages in Theravāda Buddhism. However, rather than treating this as a challenge to their monastic status, which they said they regarded as superficial in any case, my informants focused on their own spiritual cultivation. It is nevertheless worth noting that these fully ordained Sino-Burmese nuns—living in the sociocultural context of Theravāda-majority Myanmar, where monks are disproportionately powerful compared to nuns—could not avoid gender injustice and/or hostility towards their minority religious position. On the positive side, however, they appeared to be receiving more respect from the Burmese laity than in the past. The next section explores these nuns’ interactions and relationships with monks, whether local Burmese or fellow Chinese ones.

3. Interactions and Relationships among Burmese Theravāda Monks, Chinese Mahāyāna Monks, and Chinese Mahāyāna Nuns

This section explores gender issues, and in particular, whether Myanmar’s indigenous sociocultural ethos (e.g., monks’ superior status to nuns; the extinction of bhikṣuṇīs) affect Sino-Burmese nuns’ religious life and practices when they interact with local monks. For example, are the eight gurudharma rules more strictly observed when Mahāyāna nuns interact with Theravāda monks (e.g., do the nuns bow to them) in comparison to when they interact with Sino-Burmese Mahāyāna monks? It is also worth exploring whether Chinese Mahāyāna bhikṣus have been influenced by the local atmosphere in their treatment of female colleagues.

Before presenting the analysis of my fieldwork findings regarding these gender issues, it will be useful to take a brief look at the historical background of Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism in the sociocultural context of Theravāda-majority Myanmar, where Buddhist monks are highly influential. Unsurprisingly, the ethnic and religious boundaries between local Burmese monks and overseas first-generation Chinese monastics were hard to break through, partially due to the deep historical antagonism between the Mahāyāna and Theravāda schools. Theravāda Buddhists typically hold strong views of their religious identity, take their own traditions to constitute Orthodox Buddhism (Swearer 2006, p. 83), and express suspicions that various aspects of the Mahāyāna tradition lack authenticity. Conversely, Theravāda practitioners are often derogated as “the vehicle of the hearers” by Mahāyāna Buddhists, a reference to the role of the Buddha’s early followers who sought to become Arhats through hearing and practising his teachings. In the eyes of many Mahāyāna polemicists, these hearers are too narrowly focused on individual salvation, as opposed to the path of the bodhisattva, which aims at all beings’ liberation. This strong antagonism was expressed very quickly when first-generation Chinese monks arrived in Burma (Chiu 2020, pp. 220–24). In Yangon in the 1950s, the Ven. Leguan met overseas Chinese monks who considered themselves to be Mahāyāna bodhisattva, and on that basis had never made contact with local Burmese monks who practiced “Hīnayāna” Buddhism.26 However, he found that Burmese monks did not recognise Chinese ones as the Buddha’s disciples, even deeming them heretics in some cases, and on that basis refused to associate with them (L. Shih 1977, pp. 154–55). Alongside this historical antagonism between the two Buddhist traditions, language barriers experienced by the first generation of Chinese monks made cross-traditional dialogue and understanding even less possible in that period. Recent generations of Sino-Burmese monastics, however, are bilingual in Mandarin and Burmese and have grown up in Burmese society with a certain degree of assimilation; but whether this change has provided a boost to cross-traditional dialogue has been under-explored.

The first example I present here is Zhonghua Si, the oldest nunnery in Yangon (Wu 2006, p. 43). Almost every time I visited this institution, which is close to the Shwedagon Pagoda and the various Theravāda monasteries that surround it, I saw a particular middle-aged Burmese monk come to the main hall to worship the Buddha by offering flowers, and some other local monks who seemed to be in the habit of stopping by and engaging the abbess in friendly conversation. Other Burmese monks could also be seen teaching younger Sino-Burmese śrāmaṇerīs there (Figure 1 and Figure 2). I was even told by an informant nun that Theravāda monks living around this temple knew that Chinese Mahāyāna monastics eat Yaoshi (medicine stone)27 and sometimes came to eat dinner with them.

Figure 1.

The abbess of Zhonghua Si having a friendly chat with a Burmese monk (Source: Author).

Figure 2.

A Burmese monk teaching female novices at Zhonghua Si (Source: Author).

This raises some interesting points. For one, the contacts I observed between Sino-Burmese Mahāyāna monastics and Burmese Theravāda monks at Zhonghua Si seemed to be more harmonious than in the past, or even collaborative, as well as more frequent. However, we cannot deny that the long-standing antagonism between the Mahāyāna and Theravāda schools will not be easy to resolve due to differences in doctrine, religious practices, and views of the ultimate goal, among other matters. Likewise, a broadly conflictual relationship still exists between these traditions, and should not be overlooked. For example, one of my informant nuns in Yangon told me that the Theravāda teacher at her Buddhist educational centre asked the male novices there not to worship Avalokiteshvara (Guanyin 觀音) because she is female and considered a deity. Additionally, a Burmese layman pointed out to me that Burmese people only know Shakyamuni Buddha, but do not know Amitabha Buddha (Amituofo 阿彌陀佛) or Medicine Buddha (Yaoshifo 藥師佛). In other words, some key elements of Mahāyāna tradition were neither understood nor accepted by local Burmese monastics and laity as of 2018–2019.28

Second, the interpersonal interactions I observed—chatting, teaching, eating, and just dropping by—demonstrated not only that the relationship between Zhonghua Si’s nuns as second-and third-generation Sino-Burmese monastics and their host-country Theravāda counterparts was broadly better than the relations between Theravāda and Mahāyāna monastics in the middle decades of the twentieth century; they also seemed to support the idea that Burmese as a shared language was crucial to widening the channels of communication between these two groups of practitioners. Indeed, I would argue that without this shared language, it would not be possible to break the ethnoreligious boundaries between Chinese Mahāyāna and local Theravāda Buddhists, given the marginalised statuses not only of the former religious tradition but of Sino-Burmese ethnicity. What surprised me most was that a few local monks came to Zhonghua Si to eat supper with Sino-Burmese nuns, which ran contrary to the widely perceived strictness of Theravāda Buddhists’ adherence to fasting after midday (Chiu 2015), and implied a strong relationship of trust between my informant nun and her Theravāda counterparts.29

Lastly, but no less importantly, was the cross-traditional collaboration in education that I observed.30 Zhonghua Si was similar to other Chinese Buddhist monasteries I visited in Myanmar in having a learning centre for young ethnic-Chinese monastics,31 and during my fieldwork in such places, I sometimes observed Theravāda monks or local thilá-shin teaching young novices, often in subjects requiring knowledge (e.g., of Pāli) that most Sino-Burmese abbots and abbesses lacked. On the one hand, we can see this educational cooperation not merely as an index of the improved relationship between the two traditions, but also potentially as a manifestation of the future development of Buddhism via cross-traditional collaboration or even union. On the other, given that the Chinese Mahāyāna tradition has minority status in Myanmar, its destiny will depend critically on future generations of well-educated monks and nuns, conversant in both the Burmese language and Pāli doctrines, who can continue to propagate it via verbal preaching to both Burmese laypeople and Sino-Burmese ones who have undergone strong Burmanization. Better education, in turn, will tend to improve the status of Chinese Mahāyāna monastics in Myanmar. As Susanne Mrozik (2009, p. 365) aptly put it, “across the Buddhist world, the status of [monastics] is most directly linked to their levels of education in Buddhist canonical languages, scripture and philosophy.” Unsurprisingly, against this backdrop, some Sino-Burmese abbots and abbesses I met paid careful attention to the next generation’s education. All that being said, however, it must be borne in mind that Zhonghua Si is not fully representative of the contemporary Chinese Mahāyāna monastic scene in Myanmar, especially insofar as it is surrounded by various Theravāda monasteries. As such, research findings about the two traditions’ interactions in other monastic institutions in different regions, and whose Sino-Burmese abbots/abbesses differ in their individual characteristics including language skills and saṅgha-management preferences, will inevitably vary.

A second instance that will help to broaden the present discussion of gender perspectives was the 6th Southeast Asia Sangha Offering Puja in Yangon, organised by Ciguang Si 慈光寺 in Taiwan and held on 8 September 2018.32 The abbot of Ciguang Si, Ven. Hui Kong 惠空, collaborated with Luohan Temple (now a Chinese Buddhist nunnery), donating money and offering lunch to more than a thousand monastics in the Insein Ruama Pariyatti Institute (緬甸仰光巴利文僧伽學院). During this offering event,33 the dean of this Pāli College, Sayadaw U Tiloka Bhivamsa (因聖亞瑪大師), and 1187 Burmese monks joined Chinese Mahāyāna monastics and laypeople from both Taiwan and Myanmar in the Main Hall for Buddhist chanting and mutual conversation, with Luohan Temple’s abbess (Ven. Hongxing) serving as a moderator and translator. This event was a very important manifestation of the Mahāyāna/Theravāda cross-traditional dialogue and cooperation that has been increasingly prevalent in recent years. More importantly, while attending this event, I witnessed some interesting phenomena that corroborated the received wisdom on unequal gender relationships in the monk-dominated context of Myanmar. First, I observed that Sino-Burmese nuns (both bhikṣuṇīs and female novices) sat at lower levels than senior monks (Figure 3) and that Ven. Hongxing knelt next to senior and influential Burmese monks when translating or discussing (Figure 4 and Figure 5). It was likewise unsurprising that other Buddhist nuns attending this event were seated among the Taiwanese and Sino-Burmese laity, i.e., in the front row, instead of at the centre of the meeting room with the male monastics.34

Figure 3.

Monks seated at higher levels than Sino-Burmese nuns while posing for photos (Source: Author).

Figure 4.

Ven. Hongxing kneeling next to influential senior Burmese monks during an event (Source: Author).

Figure 5.

During a lunchtime discussion, two monks sit in chairs while bhikṣuṇī Hongxing kneels on the floor (Source: Author).

As a scholar from Taiwan, where bhikṣuṇīs’ status continues to rise inexorably amid a general atmosphere of gender equality (Heirman and Chiu 2012), these arrangements seemed to me to reflect rank—noble vs. base—through the differentiation of high/low positioning, and to reveal subtle power negotiations and competitions among the various participants (see Bourdieu 1996). Specifically, the Burmese monks’ higher positions clearly reflected their greater sociocultural capital in Theravāda-majority Myanmar, relative to that of their female counterparts, regardless of Mahāyāna or Theravāda tradition. As Melford Spiro (1970, p. 398) noted, “[a]t public gatherings the monk sits above the laymen on a platform or dais”, as a way of showing reverence for the former; but Ven. Hongxing and other senior as well as junior Buddhist nuns attending this event were female monastics but sat together with laity, instead of being arranged in the areas with other less-senior Burmese monastics. These seating phenomena raise three important questions. Did the local Theravāda ethos underlie Chinese Mahāyāna nuns’ gendered experiences of subordination to Burmese monks at this formal event? Did Chinese Mahāyāna bhikṣuṇīs want to be on a par with the local Burmese monks while attending it? And what did these nuns think of bowing to monks in a Theravāda host country?35 My informants answered them as follows.

Bhikṣuṇī (A): Myanmar belongs to the Theravāda tradition, in which the bhikṣuṇī lineage has historically died out […]. Monks in Myanmar and other Theravāda Buddhist countries do not recognise the existence of Chinese Mahāyāna bhikṣuṇīs and see us as novices. We cannot sit on an equal footing with monks […] I personally will respect the rules [about not sitting at the same height as monks] if I go to Theravāda temples […]. I recognise myself [as a bhikkhuni] and do not care how others see me, because this is the local custom and tendency that we cannot change and don’t have the ability to change.

Bhikṣuṇī (C): Hardly any Theravāda countries either recognise our Vinaya [i.e., the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya] or the bhikṣuṇī precepts. [Monks] do not recognise my bhikṣuṇī identity since the bhikṣuṇīs order does not exist [here…]. One Taiwanese monastic group came to Myanmar for cultural-exchange events. However, Buddhist nuns were arranged to sit under the stage and wondered why they could not sit on the stage [with the monks …]. But it was impossible because those monks were the National Saṃgha Committee Chairman and senior monks. Our master taught us that we must accept local culture even though we are bhikṣuṇīs [...]. We need to be humble and act in a low-key way[.]

Bhikṣuṇī (D): Monks and nuns are sharply distinguished in Myanmar [… because] there are only precept nuns and no bhikṣuṇīs here […]. We respect their customs and keep a low profile[.]

Importantly, I would not describe these key informant nuns as either conservative or poorly educated. Rather, as well as having good educational backgrounds, they all had international experience. So, far from endorsing the local subordination of nuns to monks, their failure to struggle against it could be ascribable to their focus on their own spiritual cultivation, as opposed to striving for status recognition. On the other hand, however, these Sino-Burmese nuns could be seen as making excuses for having assimilated into the local ethos of gender hierarchy, despite their assertions of having maintained a sense of continuity with the key characteristics of Chinese Buddhism. Be that as it may, given their doubly marginalised status as both members of a religious minority and as inferior members of an unequal gender hierarchy, Sino-Burmese nuns did not feel they could challenge or change the domination of Buddhism by monks in Myanmar. It is also worth noting a further reason that these self-aware nuns gave for keeping a low profile in Theravāda-majority Myanmar: to ensure Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism’s continued development there. As such, we should not overlook the fact that, in the dynamic encounters between minority outsiders and majority insiders when the former enter the latter’s territory, it is difficult and sometimes impossible for the newcomers to reform and challenge the locals’ cultural mainstream and its taboos. In other words, it might in fact be both unwise and useless for Sino-Burmese nuns to stage a rebellion against local Burmese monastic authority aimed at gaining recognition for their bhikṣuṇī identity and/or equal seat allocation with monks (e.g., the case of Ma Thissawaddy in Myanmar), given the negative impact such a rebellion could have on their religious life and, indeed, on Mahāyāna Buddhism’s local survival. Instead, some of my informant nuns adopted a strategy of donation to local charities and medical provision (see also Chen 2015, pp. 25, 33, 41) to interact and build mutual understanding with Theravāda monks and allow Theravāda Buddhism to—so to speak—catch glimpses of Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism, on the way to the latter potentially gaining a societal foothold. Simply put, giving donations is an obvious way of exhibiting one’s friendliness and goodwill across ethnic and religious boundaries, the positive results of which can be realized quickly.

There has been considerable attention and debate among academics on the gurudharma rule mandating bowing: that, even if a nun has been ordained for a hundred years, she must rise up from her seat when seeing a newly ordained monk, and must pay obeisance and offer him a place to sit. For example, Owen (2003, p. 9) criticised the Buddha’s use of the eight rules to relegate bhikṣuṇī to a “disadvantaged position and second-rate status”. Several generations earlier, I.B. Horner (1930, p. 121) recognised that almswomen were limited by this rule and wrote that it was “the outcome of an age-old and widespread tradition rather than a prudent provision to keep women in their place”. Lorna Dewaraja (1999, p. 73) noted that although Mahāprajāpatī and her followers were given permission to establish the order of nuns, the price they paid was control by and inferiority to the monks. Rita Gross (1993, p. 37) took a similar view, that the core of each rule was followed by reinforcement of this “gender hierarchy”. While exploring the interaction between monks and nuns in terms of this rule’s implementation, however, we should not overlook the impacts of social contexts and cultural customs. For instance, nuns’ practice of paying homage to monks via bowing indicates complex implications in Chinese contexts (Chiu and Heirman 2014). In contemporary Taiwan, kneeling down to anyone is not a socially common custom, and thus is likely to carry heavier hierarchical implications there than in cultures where it is fairly commonplace, such as in South Asia (Tsomo 2004; Cheng 2007). In Myanmar, every layperson—including even the head of state and the monks’ own parents—are required to worship monks by kneeling and touching their foreheads “to the floor or ground three times” (Spiro 1970, p. 397). Against this backdrop, it is worth recounting the perceptions of bowing in Myanmar held by my key informant nuns, all of whom had either studied abroad or stayed in Taiwan for other reasons.

Bhikṣuṇī (A): There is no high standard to practice the gurudharma in Mahāyāna monasteries [… But Buddhist nuns] need to respect monks by bowing for the implementation of the gurudharma when they go to Theravāda monasteries[.]

Bhikṣuṇī (C): There is no habit [of bowing in Taiwan]. But I will pay homage to monks here […]. Male monastics are more senior than female ones in precepts. This is respect: I respect him as a bhikkhu and also respect his robe. I understand my bhikṣuṇī precepts: even though I have been ordained 20 years, I still bow to our male novices. I do not mind paying homage to them since I agree with the Buddha about observing the precepts. You can see how humble you are while bowing [… Yet, in this institution], I am the only nun who bows to novices [… One] told me that his [Theravāda] master commended me for understanding the precepts well in life […]. The saṃgha shall be harmonious if everyone pays attention to this for mutual respect[.]

Bhikṣuṇī (B): We as nuns of course need to kneel down to monks. Monks themselves pay homage to their masters upon seeing them. If my ordination was years before yours, you must bow to me if you see me between monks. Eight- and ten-precept nuns also bow to monks and their student nuns do too. Laypeople also kneel down to them [i.e., precept nuns]. I feel that Theravāda Buddhism is doing better than Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism when it comes to respecting senior masters […]. Monastics and laypeople in Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism are unlike those in Theravāda Buddhism, who respect teachers and monastics by kneeling down thoroughly.

These excerpts raise interesting points that we cannot overlook. First, it is clear that sociocultural factors crucially affected my informant nuns’ ways of thinking and behaving, even though they had experienced an atmosphere of near gender equality in Taiwanese Buddhism,36 in line with the English proverb, “When in Rome, do as the Romans do.” This demonstrates how important it can be for religious-minority outsiders to modify their practices through processes of localisation. Second, one of my informant nuns praised the local Theravāda ethos of paying homage to senior monks and teachers as a mark of respect. Her comment opens up a fresh perspective on the issue of bowing, one that transcends many researchers’ narrow foci on gender hierarchy or inequality and highlights the importance of not making hasty judgments of other religions and practices based on our own cultural biases or, worse, an innate if unconscious sense of our own superiority. As Rita Gross (2005, p. 22) warned us, we should “be careful not to project our feminist values onto the religious and cultural situations of other times and places.” In this spirit of seeing phenomena from outside the so-called feminist angle, I re-examined my photos and videos of the donation ceremony and other key moments from my fieldwork and usually could see Burmese junior monks kneeling down to their teachers or well-known masters when meeting them (Figure 6), revealing a more complex state of affairs than accounts based on gender hierarchy alone would tend to suggest.37

Figure 6.

Monks and a layman talk to Sayadaw U Tiloka Bhivamsa and pay homage to him before an event (Source: Author).

While this section’s focus is on cross-tradition interactions and relationships between Burmese monks and Chinese Mahāyāna nuns, it is also an attempt to paint a more general and realistic picture of how contemporary Sino-Burmese monks may have been influenced by indigenous cultural characteristics, and in particular, monks’ status as superior to nuns, even though Sino-Burmese nuns in contemporary Myanmar outnumber their Chinese male counterparts. One of my key informant monks in Yangon stressed that female renunciants—whether local precept nuns or Chinese bhikṣuṇīs—could not sit on an equal footing with Burmese monks, and that Burmese bhikkhus’ seat allocations are based on their years of ordination. Additionally, this informant monk strongly emphasised to me that, even though Chinese bhikṣuṇīs could not sit with Chinese monks as their equals in some formal Buddhist ceremonies because of the local cultural context and gurudharma rules, they could nevertheless be photographed standing together on informal occasions. It is clear that an external contextual factor, which can be summed up as the Burmese ethos, has exerted considerable influence on how Sino-Burmese nuns are expected to behave even in settings where only Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhists are present.

In another fieldwork observation at a monastery in Yangon, I saw a very old nun and one younger nun around 30–40 years old working together in the kitchen, cooking for the whole male Chinese monastic population (novices and bhikkhus), though a few male novices assisted these nuns as part of their monastic training (Figure 7). When I asked the abbot why these two nuns were responsible for cooking work, he simply replied that the nuns were expert at it.

Figure 7.

Two bhikṣuṇīs working in a kitchen, cooking for male monastics (Source: Author).

His comment spontaneously reminded me of Taiwanese master Ven. Guang Qin,38 who believed that to have been born a woman was a result of karmic obstacles; and for that reason, he required all his nun followers to first complete seven years’ work in the kitchen as the basis of their spiritual practice (Shi 1994, pp. 79, 105, 196; Li 1999, pp. 98, 110). Yu-chen Li (1999, p. 98) likewise indicated that to be a Buddhist nun in post-war Taiwan was virtually the same as being a cook. Currently, many competent and well-educated nuns in the largest dual-saṃgha39 Buddhist institutions in Taiwan (e.g., Dharma Drum Mountain, Fo Guang Shan, Chung Tai Chan Monastery) are engaged in various forms of contribution and service to Buddhism and society, rather than cooking food as the daily focus of their religious lives.

In the case of the above-mentioned young Sino-Burmese nun working in the monastery kitchen in Yangon, a senior layman knew her background well and shared details of it with me. This nun had graduated from one university in Myanmar before becoming the old nun’s disciple and following her example by cooking and doing other work in the kitchen. Some people, including the layman I was speaking to, felt it was a pity for a nun with a good education to work in the kitchen, and they had tried to persuade her to better herself by studying at the Burmese Buddhist College. The young nun, however, declined such opportunities, partially due to the Burmese context and partially due to her concern for her master, whom (she thought) no one could work with if she left. Based on the layman’s remarks, this nun in the future after her master dies might become stuck in a primary role of cooking in a monastery kitchen for Sino-Burmese monks, unless she personally wants to change her fate and situation through self-empowerment or even resistance.

To me, this incident starkly illustrated the constraints of Chinese female monastics’ development in Myanmar, due to both the Burmese cultural context and the preference for traditional mentorship over formal education. On the one hand, we can see the profound loyalty of the young nun to her master, in line with the English proverb, “A day as a teacher, a lifetime as a father.” Going against the grain of the high percentage of Sino-Burmese novices and monks who disrobe, the younger nun showed her determination in this working environment that was obviously inappropriate to her education level. On the other hand, we cannot ignore that this nun’s situation reflected the relative lack of good learning programmes at Buddhist monastic colleges for Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhists in Myanmar.40 Nevertheless, every cloud has a silver lining: despite the fact that the local context and monastic learning settings were generally unfavourable to Sino-Burmese bhikṣuṇīs’ development, some talented Sino-Burmese nuns study abroad41 and then return to Myanmar, not only to foster the future of the Chinese Mahāyāna tradition there but also to create their own ways of propagating it. For example, bhikṣuṇī Hongxing told me that she not only taught Sino-Burmese male novices in a monastery but also had experience of instructing bhikṣus in Chinese learning. Her excellent education and monastic experience indeed led her to win people’s recognition and inspire many younger Sino-Burmese nuns in the Burmese context of monks’ superior status to nuns. Of course, we cannot deny the fact of gender restraint; as one of my informant monks said, Ven. Hongxing’s influence as a leader of Chinese Buddhism in Myanmar would be more powerful if she were a monk.

Most importantly, contemporary female Chinese monastics play an indispensable role in overseas Chinese communities that we cannot overlook, regardless of whether they are seen as bhikṣuṇīs or precept nuns by the ethnic-Chinese laity. The next section explores the interrelationship between Sino-Burmese bhikṣuṇīs and the ethnic-Chinese laity in this Theravadin Burman-majority nation.

4. The Role of Chinese Bhikṣuṇīs in the Sino-Burmese Community

Generally speaking, monks play an important role as the recipients of lay benefactions, as part of a complex interdependent relationship between Buddhist clergy and laity in Myanmar. The existence of monks is, metaphorically, a “field of merit” in which laypeople “‘plant’ good deeds and ‘reap’ the consequence of their improved karmic states” (Kawanami 2013, p. 131). Most importantly, Burmese people hold the view that they can obtain more merit by donating to those monks who have the most monastic purity (i.e., observe the rules most strictly), in line with Spiro’s comment that “the amount of merit acquired from alms-giving is proportional to the piety of the recipient” (Spiro 1970, p. 412). In other words, lay donors make a bad merit investment by offering to less-virtuous monks; and it is thus logical for them to donate to monks they respect and admire. Against this backdrop, Burmese precept nuns are unquestionably in a more vulnerable situation, since they occupy a status that is both inherently ambiguous, and unquestionably inferior to that of monks (see Kawanami 2013, pp. 131–51; 2020, pp. 95–118). The aim of this section, therefore, is to explore current Sino-Burmese bhikṣuṇīs’ roles and interactions with the ethnic-Chinese laity in Myanmar.

My key lay informant, who was over 80 years old, had witnessed the historic decline and development of Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism in Myanmar. Based on his personal experience, he told me that in places in the country where Sino-Burmese people generally had been influenced by local culture, there were only precept nuns, no bhikṣuṇīs. The Sino-Burmese laity, he said, usually requested that Chinese Mahāyāna monks conduct the Ceremony for the Liberation of the Deceased.42 In the past in Upper Burma, relatively few people supported Sino-Burmese nuns, some of whom even ran small businesses such as food pickling to make ends meet. They suffered considerably and received poor Buddhist educations due to the traditional master–disciple system. But nowadays, he told me, more laypeople were going to nunneries to make donations than in the past.

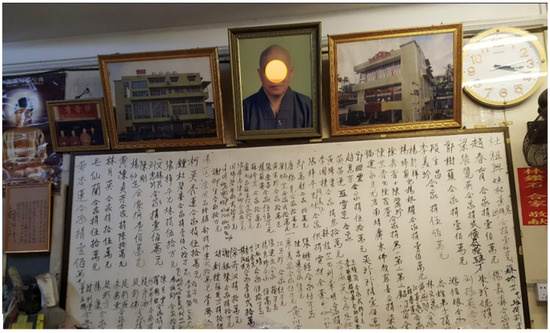

My first-hand data indeed resonated with this informant’s comments about increased levels of ethnic-Chinese lay support for current Chinese nunneries. Below, I will discuss two nunneries from among my fieldwork sites as cases of interaction and interdependence between Sino-Burmese bhikṣuṇīs and local ethnic-Chinese laity in dharma services and rituals.43 Generally speaking, Chinese nunneries and monasteries’ major lay supporters are drawn from the less de-Sinicized Yunnanese group, rather than the Burmanized Hokkien or Cantonese ones. I attended one dharma service on 10 September 2018, the first day of the lunar month, in Miaoyin Si 妙音寺.44 In the early morning before the beginning of the dharma service, some female laypeople came to this nunnery and prepared vegetarian food for the day’s lunch. The abbess of Miaoyin Si, Ven. Miaoci, was so busy greeting attendees and checking everything for the dharma service that she did not have time to talk with me before the ceremony. This senior nun, aged more than 70, was charismatic and friendly, and had attracted the long-term loyalty of many Sino-Burmese laypeople, who supported her nunnery’s construction projects and year-round dharma services. I saw numerous different donors’ names and the amounts they had given, in written and printed Chinese,45 adorning many parts of the nunnery’s interior (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Hand-written donors’ names and donated amounts (Source: Author).

During the ceremony, the senior nun led around forty, mostly female attendees in chanting the Eighty-eight Buddha Repentance Service and the Sutra of the Medicine Buddha for blessings and elimination of calamities. The ritual atmosphere was harmonious; I observed laypeople assisting each other while chanting. The senior nun did not give a dharma talk after the ceremony ended. During the lunch, more than 100 people ate large vegetarian meals offered by devoted laypeople (Figure 9). Ven. Miaoci interacted extensively with those who were eating, greeting them table-by-table and announcing in Mandarin and Burmese that the next dharma service would be held on the 15th day of the same lunar month. Some laypeople entertained the others by singing songs. After lunch, the majority of the laity left the nunnery, but a few stayed and chatted with the abbess. One old and wealthy laywoman explicitly told me that she had followed and supported this nun since she was young. Many of the laywomen that this nun’s charismatic presence had attracted over many years did not need to work after marriage, and they had ample time to worship at different temples and donate money for merit accumulation. From my observations, it is clear that an older-generation Sino-Burmese nun who did not study abroad can be well supported by local ethnic-Chinese Buddhist devotees in Myanmar, despite her supposedly inferior nun’s identity. Additionally, my data suggest that this Chinese Buddhist nunnery functioned not only as a religious site for the laity but also as an important venue in which members of Myanmar’s Chinese ethnic minority could seek social connections and mutual assistance.46 This fieldwork observation significantly resonated with Kawanami’s (2013) point (p. 131) that Buddhist temples in Myanmar are essential “social venues” in which people can network with those of different social ranks, share information, and redistribute money.

Figure 9.

Sino-Burmese laypeople eating together after a Buddhist ceremony on the 1st day of the lunar month (Source: Author).

The other case I would like to present is Luohan Si, where the well-known bhikṣuṇī Ven. Hongxing is the abbess. On 9 September 2018, I attended a Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva Sutra Dharma Service at Luohan Si, and upon entering was struck by a sense of familiarity: the main hall was decorated like those of some of the nunneries or monasteries I had visited in Taiwan. Ven. Hongxing studied abroad, at Yuan Kuang Buddhist College in Taiwan, an experience that had clearly influenced her way of managing as well as refurbishing her nunnery. For example, a contingent of Sino-Burmese volunteers had been very well developed, to the point that the abbess did not need to recruit people to cook and clean.47 I also noted that many Sino-Burmese laywomen attended the dharma service she held because of her already established reputation in local ethnic Chinese Buddhist communities. Some laity chanted the sutra, and some just knelt down without chanting, presumably because they could not read Chinese. What surprised me most was that Ven. Hongxing gave the attendees a dharma lecture after the end of the ceremony, in which she explained the Ksitigarbha Sutra in Mandarin Chinese and encouraged the laity to study more sutras, as a means of becoming better Buddhists (Figure 10). Laywomen of various ages paid close attention to what the abbess was teaching them.

Figure 10.

Sino-Burmese laity listening to Ven. Hongxing giving a lecture at Luohan Si (Source: Author).

Based on my own observations, giving such Buddhist talks—either after rituals or to Sino-Burmese laypeople—is rare in Myanmar; and many of my monastic and lay informants confirmed that the norm among overseas Chinese was to come to Buddhist temples to burn incense, worship the Buddha, chant sutras, and pray for family or individual blessings and fortunes, not to learn about Buddhism in any profound way. Some of them could not even distinguish between bodhisattvas and folk deities.48 Those who were interested in Buddhist dharma knowledge would go to Theravāda monasteries to be taught by Burmese monks.49 Nor is this situation particular to Myanmar: well-known Chinese Buddhist monks who migrated to Singapore (e.g., Ven. Yen Pei 演培) and Malaysia (e.g., Ven. Chuk Mor 竺摩) have observed and experienced similar phenomena (Chia 2020).

On the one hand, it is clear that most of the Sino-Burmese Buddhist laity’s worship of the Buddha in Buddhist monasteries has a strong utilitarian tendency,50 much as Han Chinese believers in folk religion pray to deities in temples (see Lai 2003, p. 58; Li 2010, pp. 276–77). This attitude toward religion is not uncommon in Chinese communities, whether in Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, or Myanmar, in line with the well-known Chinese proverb, “the more deities they worshipped, the more blessings they would receive” (Chia 2020, p. 58). One middle-aged monk who had studied abroad in Mainland China and returned to Mandalay took over a Buddhist temple from an elderly monastic relative and expressed a strong view of how difficult it had been for him to make changes to the Sino-Burmese laity’s perceptions of Buddhism. Likewise, I attended one ullambana ceremony at Jingming Chan Si in lunar July and witnessed a leading monk give a dharma talk in Yunnanese about making merit and practicing wholesome deeds for the laity’s deceased relatives before the chanting of sutras in the afternoon. Again, however, many older laypeople fell asleep while the monk was teaching. What surprised me was that many of those among the laity who looked absent-minded during the talk chanted loudly and sincerely when the ceremony subsequently began.

An interesting contrast to this was provided by the Burmese Theravāda laity. On one full-moon Sunday in Yangon, on the recommendation of a taxi driver, I visited a Theravāda monastery and observed the interaction between Burmese monks and the local Burmese laity during a Buddhist dharma lecture. Upon arriving in the lecture hall, I could sense a completely different atmosphere there. Around thirty local people attended this lecture (Figure 11), and—as my driver had promised—the lecturer was very charismatic and engaging. Most significantly, interactions between the speaker and listeners were frequent. The laypeople usually responded to the master by nodding their heads and echoing/repeating his words while listening and learning.51 In short, their attitude toward dharma learning was far more enthusiastic than that of the Sino-Burmese laypeople I observed elsewhere, whose focus, in line with my informants’ prior remarks, was on ritual rather than dharma learning.

Figure 11.

Burmese laity listening attentively as a master lectures (Source: Author).

On the other hand, the relative lack of dharma lectures by Chinese Mahāyāna monastics could help explain the defects in the laity’s Buddhist knowledge. Dharma teaching is challenging, especially so if the monastic delivering it has not received appropriate Buddhist education and training. As I mentioned in a previous section, there is a profound gap in such education and training between elderly and middle-aged Sino-Burmese nuns. In part, this is because first- and second-generation overseas monastics tended to focus mainly on individual spiritual cultivation, by chanting sutras and conducting rituals under mentorship. Therefore, these earlier-generation monks and nuns could only perform the liturgy and rites that overseas Chinese communities needed, and the teaching of Buddhist knowledge was completely de-prioritised. Alongside the Sino-Burmese laity’s above-mentioned utilitarian tendency, it is worth considering how, and how much, this historical legacy has influenced the ways of preaching and teaching Chinese Buddhism in Myanmar (and, indeed, in other overseas Chinese Buddhist communities). Most importantly, we should not ignore the fact that the slow development of Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism in Myanmar has in part been due to a relative scarcity of learned Chinese migrant monks, who—if they had been more numerous—might have reformed or modernised it there, much as Ven. Yen Pei and Ven. Chuk Mor did on the Chinese periphery in Singapore and Malaysia (Chia 2020).52 In other words, the development of Buddhism is inextricably bound up with the development of Buddhist learning and education.

Let us return now to Ven. Hongxing’s Buddhist lecturing activity in contemporary Myanmar. Atypically, she gives dharma talks after ceremonies in her nunnery for her lay disciples, providing them with a certain degree of Buddhist education. From my observations, this nun appeared to be doing so, despite the obvious challenges involved, based on strong religious convictions regarding the propagation of Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism in Myanmar. During the lunch at one such event, Ven. Hongxing—like Ven. Miaoci—engaged in chit-chat with ritual attendees, and clearly recognised which laypeople had been there before vs. which had come for the first time. Additionally, some laywomen familiar with the abbess consulted her about their family problems and religious questions.

From the two cases I presented here, and fieldwork observation in other nunneries, I can conclude that Sino-Burmese bhikṣuṇīs are indeed important to the ethnic-Chinese laity in Myanmar, particularly laywomen. Partially owing to their being of the same sex, and therefore lacking the boundaries between male monastics and female laity, it is much more convenient for female laypeople to consult nuns about their personal problems (e.g., about marriage) since a nun may understand and empathise with difficulties specific to being a woman better than a monk can. Most importantly, each nun has her own leadership style and personality that can attract laypeople with various characteristics to support her nunnery. For instance, some might be drawn to Ven. Hongxing’s nunnery as a Buddhist learning centre, while others might prefer Ven. Miaoci’s as a religious venue for social networking. Also, while many of the laywomen I observed seemed to have easy interactions and mutually beneficial relationships with Sino-Burmese bhikṣuṇī, partially due to being the same sex, my unexpected fieldwork findings in Mandalay indicated that they nevertheless exhibited a utilitarian tendency when attending certain types of ritual ceremonies.

On 24 August (lunar July) 2018, I attended an ullambana ceremony at Jingming Chan Si. In particular, I was interested in learning whether Sino-Burmese monks conducted it in accordance with the key characteristics of Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism in Taiwan and Mainland China. Also, I wanted to observe how Sino-Burmese laypeople (most of whom were the descendants of migrant Yunnanese) practised this important ritual for their deceased relatives. Unsurprisingly, I encountered numerous lay people participating in the ceremony, in a new, larger Main Hall (Figure 12). The ullambana ceremony is critically important and meaningful for overseas Chinese and involves chanting sutras and offering food and donations to the monastic community (both as a meritorious act and for the consolation of their ancestors’ souls), in light of their tradition of filial piety (e.g., Teiser 1988).

Figure 12.

Numerous Yunnanese laity attentively and respectfully participating in a chanting ceremony at Jingming Chan Si. (Source: Author).

Later in the afternoon, monks and laypeople left the monastery and drove to the riverbank, where they conducted the rituals of releasing water lanterns (Fangshuideng放水燈) and releasing animals (Fangsheng 放生). I was kindly invited by a young laywoman who had met me previously to go to these ceremonies in a car with three other women. On the way, these Sino-Burmese women chatted in Yunnanese, which I was able to understand to a certain degree. Upon hearing their praise of the day’s ceremony and the monks, I asked them for further explanations. All of them passionately responded to my inquiry, and I have summarised their key viewpoints below.

In the past, many Chinese Buddhist institutions were run by Buddhist nuns, and many ceremonies were held in Jinduoyan53 nunnery. However, perhaps because the abbess was so old, some laypeople felt that she no longer performed them well. In recent years, young Buddhist monks [from Shifang Guanyin Si in Yangon] came here and recommended by word of mouth by Sino-Burmese laypeople who felt that they chanted sutras sincerely and loudly, and this led to them embracing ceremonies again and participating in more of them. In other words, the monks who performed ceremonies were much very on point in comparison with nuns. As family members of the deceased, we always hope that ritual masters will perform ceremonies well for their blessing. The laity will observe monastics and then compare them.