Abstract

We report here some of the results from an online survey of 1612 LGBTQ members and former members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (CJCLDS, Mormon). The data permitted an exploration of diversity—individual similarities and differences within and between the sexes. Men and women were compared with respect to sexual identity self-labeling and behavior (i.e., identity development, disclosure, activity), orientation change efforts, marital relationships, and psychosocial health—these variables in the context of their religious lives. More women than men self-identified in the bisexual range of the sexual attraction continuum. Both men and women had engaged in extensive effort to change their sexual orientation. Only about 4% of the respondents claimed that those efforts had been successful, and the claims were for outcomes other than an alteration in erotic feeling. In general, only those who identified as bisexual reported success in maintaining a mixed-orientation marriage and continuing activity in the church. For both men and women, measures of psychosocial and sexual health were higher for those in same-sex relationships and those disaffiliated from the church.

1. Introduction

In a recent essay, Andrew Barron (2019) asserted that, “Two things are clear about human sexual orientation. First, it is biological; second, it is complex.” Multiple reviews of the relevant research evidence attest to the first point (Bailey et al. 2016; Cook 2021; Ngun and Vilain 2014; Rice et al. 2012). For example, “Human sexual orientation and in particular its less common form homosexuality, is thus not mainly the result of postnatal education, but is, to a large extent, determined before birth by multiple biological mechanisms that leave little to no space for personal choice or effects of social interactions.” (Balthazart 2016, p. 8). Thus, same-sex sexuality is a normal variant whose origin lies in genetic and epigenetic determinants that program the brain during and immediately after embryonic development (parenthetically, available evidence supports the same conclusion for gender identity; Polderman et al. 2018). Again, research has not produced evidence to support alternative, psychosocial postulates, as an explanation (Bailey et al. 2016).

As to the second point, Barron argued that sexual complexity is under-appreciated; just as there is sexual diversity among heterosexuals, not all sexual minority individuals are the same. In the context of conservative religious socialization, we explore biological sex as a factor in understanding within-group heterogeneity among those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, or another personally meaningful sexual orientation label (LGBQ+). Some physical differences between men and women, those that also distinguish gay men or lesbians, clearly have a biological basis. Well-documented examples include differences in hearing and finger anatomy due to the presence or absence of prenatal exposure to testosterone (Breedlove 2017). Other differences are directly pertinent to sexuality. For instance, men and women differ with respect to how sex drive and sexual attraction are related to orientation (Lippa 2007). These traits are among those in a proposed dimension of sexual complexity termed “sexual impulse and impulse control”, thought to be influenced by postnatal hormone exposure (Lippa 2020). For women who identify as heterosexual, high sex drive is associated with increased attraction to both men and women; in men, it is associated with higher attraction only to women (for heterosexual men) or only to other men (for gay men). Women who identify as lesbian exhibit the male-typical pattern; bisexual individuals exhibit the heterosexual pattern of men or women. In addition, women are more likely than men to experience sexual fluidity, a natural evolution of sexual attraction, behavior, and self-labeling over the course of life (Diamond and Rosky 2016; Scheitle and Wolf 2018).

Central to the issue of sexual orientation complexity is bisexuality, its explanation, and its consequences. Early sexual identity scholarship tended to invalidate the existence of plurisexual orientation (e.g., bisexual, pansexual), often characterizing it as a preliminary state eventually resolved into a gay identity (transitional bisexuality). However, contemporary scholars reject exclusively monosexual frameworks for sexual orientation, and bisexual patterns of attraction have been observed in research using physiological measurements of arousal and other assessments (Rosenthal et al. 2012; Lippa 2013, 2020). In confirmation of this conclusion, the data from a meta-analysis of eight published studies “provided compelling evidence that bisexual-identified men show bisexual genital and subjective arousal patterns” (Jabbour et al. 2020, p. 1). This same study also established the validity of the Kinsey Scale as a reliable measure with which to assess sexual orientation (Bailey and Jabbour 2020). U.S. national trends in attitudes and relationships of bisexual people have been documented in Pew Research Surveys (Parker 2015).

While a biological framework for understanding sexual orientation is well supported, the expression of sexuality is clearly subject to cultural influence (Tskhay and Rule 2015). In addition to factors in the broader society, there is the overlay of the negative messaging about same-sex attraction that has originated in conservative religious communities. This has led to conflict for LGBQ+ persons between their sexual identities and their religious faith (Dahl and Galliher 2010; Schuck and Liddle 2001). Halkitis et al. (2009) have described attempts by non-heterosexuals to reconcile their religious and spiritual identities in a hostile context.

The preceding is the context for the current study. Published papers from our data set (a survey of LGBQ+ members or former members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (CJCLDS)) have addressed issues including the failure of reorientation therapy (Bradshaw et al. 2014; Dehlin et al. 2014b), navigating sexual and religious identity conflict (Dehlin et al. 2015), measures of psychosocial health (Dehlin et al. 2014a), and comparative religious experience (Bradshaw et al. 2015, 2021). The current report contains a comparative analysis of measures of sexuality between the men and women respondents, and the resulting relationship to orientation change efforts, relationships, mental and sexual health, and activity status in the church. It is an attempt to explore the complexity of gender expression in a particular religious context.

2. Sexual Orientation Change Efforts (SOCE)

A number of published studies have assessed reparative (conversion, reorientation) therapy efforts (Bradshaw et al. 2014; Dehlin et al. 2014b; Shidlo and Schroeder 2002). Based on the resulting data, mainstream mental health practitioners have concluded that programs aimed at altering sexual orientation lack evidence for effectiveness and may produce harmful outcomes (e.g., APA 2009; SAHM 2013; Serovich et al. 2008), and their professional organizations have condemned the practice (Just the Facts Coalition 2008). The Pan American Health Organization (2012) has issued the following position statement (“Cures” For an Illness that Does Not Exist): “purported therapies aimed at changing sexual orientation lack medical justification and are ethically unacceptable” (p. 1). Nevertheless, reparative therapy advocates (e.g., NARTH 2012; Nicolosi et al. 2000; The Alliance for Therapeutic Choice and Scientific Integrity) have continued to promote change programs, even in the face of legislation prohibiting their use for minors, and a court rendering a verdict against its practitioners (Michaels 2015). The CJCLDS figured prominently in negotiations that led to a ban on conversion therapy for minors in the state of Utah in 2020 (Dwyer 2020).

3. Mixed-Orientation Marriage (MOM)

Increasing attention has been paid to heterosexual marriages in which one spouse identifies as LGBQ+ (Hernandez et al. 2011). Twenty years ago, Buxton (2001) estimated the number of such relationships in the United States at two million. He also found that when disclosure to the heterosexual spouse happened only after marriage, only one third of them remained intact (Buxton 2004). Wolkomir (2009) explored how those in MOM negotiated heteronormative expectations in their relationships. Other studies show how the MOM experience differs across different sexual orientation categories (Swan and Benack 2012), or assess the impact of religion on these relationships (Kissil and Itzhaky 2015; Yarhouse et al. 2009). Some research attention has been paid to MOM in the CJCLDS context (Dehlin et al. 2014a; Lefevor et al. 2020; Legerski and Harker 2018). The strongest predictor of sexual satisfaction among sexual minority LDS in mixed-orientation relationships was found to be the degree of other-sex attraction. This included bisexual individuals, who, nevertheless, exhibited the highest degree of anxiety and depression (Bridges et al. 2019).

5. The LDS Context

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has held conservative positions on matters of sexuality, including chastity before marriage, discouraging an LGBQ+ identity, and opposing same-sex marriage. Detailed histories of same-sex sexuality and gender diversity in the CJCLDS have been provided by O’Donovan (1994), Hammarberg (2008), and Prince (2019). In a widely read book published in 1969, Spencer W. Kimball, a prominent church authority who would later become its president, strongly denounced both same-sex sexual feelings and behavior (Kimball 1969). It was assumed that non-heterosexuality was chosen or learned, and changeable, highly immoral, and a threat to the family and society. Current institutional policy statements, however, make a clear distinction between “same-sex attraction, SSA” which is not deemed sinful, and same-sex sexual behavior, which is (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints 2007). There are other indicators of an ongoing shift in attitudes, especially in the last decade.

Statements issued decades ago by LDS Social Services (LDS Social Services 1990) were equivocal about potential biological explanations for same-sex sexuality: “Some say it is a biological condition that exists at birth while others believe it is a psychological condition influenced by the environment in which a child grows up (p. 1).” And again: “No general agreement exists about the cause of such problems” (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints 1992, p. 2). Subsequently, this same source made a deliberate effort to dismiss and invalidate the biological evidence (LDS Social Services 1995). The basis, again, for these positions clearly was that SSA was a social construct and was reversable: “The Church... teaches that homosexual attraction is not inherent to a person’s particular genetic make-up and that they are quite able to change” (Byrd 2001, p. 36). The most recent authoritative statement, however, declares that the Church does not take a position on the cause of SSA—“whether nature or nurture”, “these are scientific questions” (Oaks and Wickman 2006, p. 3).

Same-sex sexuality remains controversial among members of the CJCLDS at large. Non-institutional LDS sources have promoted psychosocial explanations for the phenomenon and advocated conversion therapy efforts (Dahle et al. 2009). Strongly negative earlier pronouncements by some high-placed ecclesiastical leaders (Packer 1998; Hafen 2009) have had residual influence, but some positions have been inconsistent. A policy statement issued November 2015 in the Handbook of Instructions (for ecclesiastical leaders) excluded those in same-sex relationships and their children from membership and labeled those in same-sex relationships as apostate (Dobner 2015). This policy was then reversed in April of 2019 (First Presidency 2019). In 2012, an official video carried a softer tone and greater spirit of inclusion for LGBQ+ persons. In 2016, the website carrying the video, “mormonsandgays”, was changed to “mormonandgay”. In 2015, the Church supported a Utah State law prohibiting discrimination in housing and employment based on sexual orientation and gender identity (Gehrke and Dobner 2015). More recently, the Church gave money to the LGBTQ advocacy group Affirmation to help in its suicide prevention efforts (KSL 2018).

Earlier, the Church provided financial and other support for Evergreen International (now defunct, and subsumed by the organization North Star), which strongly advocated conversion therapy. Following a political controversy in Utah in late 2019, the CJCLDS issued a formal statement disavowing the practice (Time 100 2019). Church president Hinckley had much earlier challenged a widespread sentiment by stating that heterosexual marriage was not to be recommended as a step to cure SSA (Hinckley 1987).

The CJCLDS has espoused a position of gender essentialism; its Proclamation on the Family stated that “Gender is an essential characteristic of individual premortal, mortal, and eternal identity and purpose” (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints 1995). That view and the accompanying focus on traditional gender roles are reiterated in instructional materials provided to its congregations (Eternal Marriage: Student Manual n.d.). Changes to the Church’s Handbook of Instructions in 2020 outlined restrictions on members who engage in transgender transitioning (Religion News 2020). The Church joined amicus briefs arguing for religious freedom in urging the U.S. Supreme Court to rule against gender equality cases now under review (Supreme Court 2019).

6. Research Questions

The current study attempts to assess differences in the experience of sexual minority men and woman who are current or former members of the CJCLDS. One premise for the investigation was that doctrines and policies of the church relative to gender may differentially impact men and women in general and have even greater specific impact on non-heterosexual individuals. We hypothesize that rigid, essentialist messages related to gender in this cultural context will frame the sexual and religious identity development experiences of those who identify as men vs. women within the CJCLDS. Several measures of sexuality were examined: identity development, orientation across three domains of the Kinsey Scale, disclosure, and activity. One focus of the analysis is on bisexuality, and the effect of the degree of one’s same-sex orientation on religious affiliation and on marital status. In addition, we carried out an evaluation of the efficacy of sexual orientation change efforts and assessed several measures of psychosocial health as a function of CJCLDS or relationship status.

7. Methods

7.1. Data Collection and Recruitment

The data reported here were obtained through an online survey conducted from July 12 through 29 September 2011. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Utah State University. Adult LGBQ+ persons who are current or former members of the CJCLDS were recruited from a wide variety of sources. The survey was advertised through the Associated Press in over 100 online and print publications throughout the United States and abroad. Twenty-one percent of respondents came from this source, and an equal number came from advertisements placed with both affirming and conservative support groups for CJCLDS LGBTQ individuals (Affirmation, North Star, LDS Family Fellowship, etc.). An additional 5% reported that they heard about the study through the Salt Lake City Pride Center or the Equality Utah organization. Snowball sampling through email, social media, and word of mouth accounted for 47% of the respondents. A detailed summary of these sources is presented in Table S1 of the Supplementary Materials. Those data also allow a comparison of sources utilized by men and women respondents, and separately by those active in the CJCLDS. In both cases, the differences are small; no systematic recruitment bias is evident.

There were 149 questions in the survey instrument, including items about biological sex, gender, age, place of residence, marital history, parenthood, and current relationship status. Other variables included sexual orientation and gender identity, sexual identity development, psychosocial measures of well-being, interventions engaged in to understand, change, or accept a non-heterosexual orientation, and a history of religious practice and belief. There were also frequent options to provide open-ended written commentary that might clarify these quantitative items. The contents of these narratives were coded separately by two raters, and their primary themes were established through discussion to consensus.

7.2. Participants

Only those who were at least 18 years old, who completed a majority of the survey questions, and who indicated some degree of same-sex attraction were included. There were 1612 persons who met these criteria. As a group, they represented 48 U.S. states and the District of Columbia, and 22 countries abroad. Of the total sample, 387 (24.1%) identified their biological sex as “Female”, and 1218 (75.9%) identified as “Male”. With respect to gender, those assigned female at birth were: cisgender women 361, transgender 7, and nonbinary 19—the last two cohorts together comprising 6.7%. Those assigned male at birth identified as cisgender men 1179, transgender 9, and nonbinary 28—the last two comprising 3.0%. The profiles for race, education, marriage, and income were similar between men and women. Most (about 95%) identified as White/Caucasian. Between 63 and 69% were college graduates or had additional technical, professional, or graduate training. Average yearly incomes were USD 30,000 for women and USD 37,000 for men. Between 30 and 35% were ever married; only about half that number remain so.

7.3. Measures

Sexuality. Respondents reported sexual orientation development along the following milestones: age of first awareness of a difference you now attribute to same-sex orientation, first romantic or sexual attraction to persons of the same sex, first romantic or sexual same-sex experience, first self-labeling of non-heterosexuality, and first told someone of your SSA. Sexual orientation was measured in three domains (behavior, attraction, and identity) using a Kinsey Scale from 0, exclusively opposite sex, to 6, exclusively same sex, with 7 indicating asexual. In addition, respondents placed themselves in one of the following categories: gay/lesbian, bisexual, heterosexual, queer, pansexual, asexual, or don’t identify. Those selecting “heterosexual” were retained because other items in the survey indicated that they experienced same-sex attraction. Disclosure was measured on a scale from 1 (closed or non-supportive) to 5 (open or supportive) for immediate family, friends, classmates/coworkers, and religious affiliates. In addition, respondents rated overall “outness’” on a 6-point scale from 1 = no one to 6 = totally open. Current sexual activity was assessed with the following: celibate by choice, celibate due to lack of a partner, sexually active in a committed relationship, sexually active, but not in a committed relationship. The history of sexual orientation change efforts (SOCE) covered a number of possible interventions including Individual Effort (education, force of will—non-religious attempts), Personal Righteousness (prayer, scripture reading, church service, etc.), Psychotherapy, and Ecclesiastical Counseling. SOCE variables included age when initiated, length of engagement, efficacy, and open-ended commentary.

Marital status was categorized as: single, heterosexually married, same-sex married, civil union, domestic partnership, opposite-sex partnership, same-sex partnership, divorced, or widowed. These variables were collapsed into three groups: single, heterosexual relationship, and same-sex relationship.

Religiosity. Respondents placed their status in the CJCLDS in one of five categories: Active (church attendance at least once per month), Inactive, Disfellowshipped, Excommunicated, or Resigned.

Psychosocial health. The Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms (CCAPS-34; Locke et al. 2012) is an instrument measuring psychological symptoms and distress. Only scores on two subscales, Depression (α = 0.90) and Generalized Anxiety (α = 0.84), are reported here. Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms; range = 0–4 for both. Self-esteem was assessed using the 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg 1965), with higher scores indicating higher self-esteem; range = 0–4 (α = 0.92). The Quality o Life Scale (Burckhardt and Anderson 2003) was employed to measure material and physical well-being, relationships with other people, personal development and fulfillment, and independence (α = 0.90). It utilized a 7-point Likert-type scale from 1 (terrible) to 7 (delighted). Higher scores indicate a higher quality of life, and an average score for “healthy populations” is 90.

Sexual health. An assessment of the respondents’ perception of the positive benefits of a non-heterosexual orientation (BSSA, benefits of same-sex attraction) was conducted. It consisted of 6 quantitative items (e.g., “My same-sex attraction has provided me with an opportunity to live a more honest and authentic life.”), and 1 open-ended response, based on the work of Riggle et al. (2008). The range for this variable is 6–24; higher scores are deemed more beneficial (α = 0.80).

We employed the Sexual Identity Distress Scale (SID; Wright and Perry 2006). It is a 7-item measure with questions such as “I worry a lot about what others think about my being (gay/lesbian/bisexual)”. Six responses from strongly agree to strongly disagree are possible. Higher scores indicate greater identity distress; range = 7–35, α = 0.91. An additional measure was derived from the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual Identity Scale (LGBIS; Mohr and Fassinger 2000). Only the Internalized Homonegativity subscale was employed, in which higher scores indicate greater negativity over a range of 1–7 (α = 0.90).

Survey data were analyzed using the R statistical package (R Core Team). Chi-squared goodness-of-fit tests compared differences in frequency distributions. OLS regression was used to test for differences among continuous variables assessing mental and sexual health.

8. Results

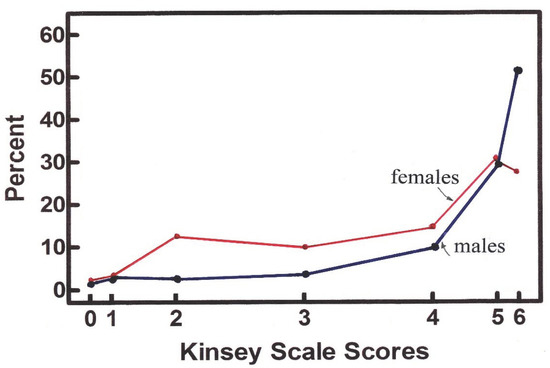

Measures of sexuality in the sample participants are presented in Table 1. On average, LGBTQ persons reported a sense of being different from their peers at an early age, somewhat before puberty. Awareness of sexual and romantic interests emerged during adolescence. Coming out to self and others occurred, on average, in the early twenties. These milestones were passed somewhat later in women than in men. For both sexes, the latter three events occurred at earlier ages in the age cohort 18 to 30 in the sample. The profile of sexual orientation was clearly different in women than in men. A much larger fraction (22.4%) of women than men identified as bisexual, queer, or pansexual. Average Kinsey Scores for sexual orientation were from 0.5 to 1.0 lower in women. For both men and women, the highest scores were in the Attraction domain. Figure 1 shows how non-heterosexual men and women were quantitatively distributed across the Kinsey Scale. The patterns are distinctly different, with 23% more women in the bisexual range, with Attraction scores of 1 through 4.

Table 1.

Sexuality Measures in the LGBTQ LDS Sample.

Figure 1.

Kinsey Scale Score Profile (Attraction): Males and Females.

Table 1 also shows that women were less open about their sexuality, reporting lower disclosure scores than men; both men and women were least open to LDS church members. A majority of persons were sexually active in a committed relationship, with 15% more women than men in that category.

When the disclosure data were tabulated as a function of sexual orientation, bisexual participants were at least 1.5 points less open than those self-reporting as lesbian or gay (an average of 2.87 vs. 4.32 for women, and 2.44 vs. 4.08 for men). Moreover, only 10% of bisexual women reported Kinsey Attraction scores of 5 or 6, and the average score of those remaining was 2.87. Many more bisexual men (31.5%) reported high same-sex attraction, and the average score for those in the low attraction range was 3.13.

Survey respondents provided information about their efforts to “understand, cope with, or change” their sexual orientation. These included the separate categories of Individual Effort, Personal Righteousness, Psychotherapy, and Ecclesiastical Counseling. A summary of the results, listed as a function of CJCLDS status, is provided in Table 2. Private efforts were initiated, on average, in late adolescence, and counseling efforts in the mid to late twenties. On average, the former lasted for as much as a decade, and the latter for about half that length of time, but clearly these attempts were extensive. As a general rule, efforts focused on increased religiosity (personal righteousness) and counseling with church leaders were perceived as least helpful or even harmful (especially by those whose membership had been sanctioned or who had resigned their membership voluntarily). This is likely because expectations/promises made in a religious context that a change in orientation would take place did not occur (see below). Private efforts by women tended to start later and extend for shorter periods than for men.

Table 2.

Sexual Orientation Change Efforts by LDS Status.

Respondents also provided written descriptions of these four categories of efforts, resulting in 786, 755, 622, and 502 narratives, respectively. Each of these written statements was read independently by two analysts, identifying any in which there was some claim of change as a result of that intervention. This review found affirmative statements by 32 individuals (4 women, 28 men). This represents about 3–4% of those supplying statements. The specific nature of their claims is revealing. The elimination of same-sex desire was reported by a single individual. All of the other narratives, in contrast, took the form of a reduction in same-sex behavior or attraction, some increase in other-sex attraction, or reduced anxiety over one’s sexual orientation.

Table 3 details the nature and experience of the individuals who made change claims. For men, a comparison is provided with an equal number of men in the survey, randomly matched pairwise by age, who did not make a change claim. These data show that the change claimants are clearly in the bisexual range of the sexual orientation spectrum (with Kinsey Scores at least 2 points below the 5-point averages reported by the non-claimants). Seventy-one percent were heterosexually married; none were in a same-sex relationship. Aspects of change efforts through Personal Righteousness are also reported. The men started those efforts, on average, 8 years later than the non-claimants (at about the time they would have returned from missionary service and would be considering marriage). They also evaluated the effectiveness of that intervention 2 points more in the positive direction than non-claimants.

Table 3.

Respondents Claiming Orientation Change.

Data reflecting the impact of differences in sexual orientation on religious and relationship variables are shown in Table 4. Those who remained active in the CJCLDS and those able to maintain a mixed-orientation marriage (or other-sex partnership) were at the low end in all three domains of the Kinsey Scale. For example, scores for women in heterosexual relationship categories ranged from 1 to 3, and for men from 2 to 4. Values at the monosexual same-sex attracted end of the spectrum (5–6) were associated with dissociation from the Church and entrance into a same-sex relationship. We note, however, the apparent discrepancy between the earlier observation of greater bisexuality among women (which should predict church activity because it facilitates heterosexual marriage) and the data reported here actually showing greater disaffiliation from the Church among women (10% fewer Active and 6% greater in the Inactive and Resigned categories compared to men). A total of 34% of bisexual women were heterosexually married (20% higher than among all women), but only 38% of those were active in the Church. Other factors besides orientation, then, are affecting religiosity.

Table 4.

Gender Comparison of Kinsey Scale Scores by LDS and Marital Status.

Data that indicate how the once-married (but subsequently divorced) differ from those who remain married as a function of sexual orientation status are shown in Table 5. Those able to sustain a mixed-orientation marriage were much more likely to be in the bisexual/heterosexual range of the Kinsey scales (88% of currently married women, and 54% of currently married men). The strong majority who experienced divorce, 84% of men and 62% of women, were positioned at the gay/lesbian end of the scale. Only about 12% of divorced individuals have remained single; most are now in committed same-sex relationships.

Table 5.

Mixed-Orientation Marriage as a Function of Sexual Orientation.

For bisexual participants (self-identified) in married and partnered relationships, we also determined whether those were with other-sex or same-sex individuals. For women, 28.4% of those who identified as bisexual (n = 96) were single; of those who were not single, 67.7% were in a relationship with other-sex partners. For men, 44.3% of those who identified as bisexual (n = 131) were single; 93.2% of those who were not single were in a relationship with an other-sex partner.

Table 6 shows how measures of psychosocial and sexual health vary as a function of relationship status and status in the CJCLDS. The general trends were the same for both men and women; depression, anxiety, sexual identity distress, and internalized homophobia were lower, and self-esteem, quality of life, and benefits of same-sex attraction were higher in those who are disaffiliated from the church and in those involved in same-sex relationships (compared to those who were single or in a mixed-orientation marriage). Note, for example, that the data for internalized homophobia for men listed by CJCLDS status were approximately linear (except for the Disfellowshipped group, where n is small). Because of these differences in the sample size among subgroups, the statistical treatment of the data was performed across both CJCLDS status and relationship status, using Active-Heterosexual persons as the standard. In the case of CJCLDS status, those identified as Active were compared to all others as a “non-Active” set. Measures of sexual health were significantly lower among active and single individuals, and highest among those in a same-sex relationship who were disaffiliated. For measures of mental health (except for Generalized Anxiety, where the differences were not sufficiently large), scores were significantly more positive among those in same-sex relationships.

Table 6.

Mental and Sexual Health Measures by CJCLDS and Relationship Status.

9. Discussion

In attempting to elucidate these results, we point out that none of the patterns exhibited rigid gender differences; general trends were the same for men and women. Nevertheless, some quantitative differences had very important qualitative consequences. In contrast to men, there was a much higher tendency toward bisexual identification among women in this sample. It was manifested in self-reports of sexual orientation identity self-labels and in the Kinsey Scale profile of erotic attraction. This is consistent with the newly published results of an international survey of sexual orientation prevalence in 28 countries. The authors of that study concluded that the stable rates of various sexual identities they found suggest that “... non-social factors likely may underlie much variation in human sexual orientation”, and the results “... do not support frequently offered hypotheses that sexual orientation differences are related to gendered social norms across societies” (Rahman et al. 2020, p. 1). There are reports that “men experience considerable pressure to hide or downplay their same-sex attraction”, or are in denial of their bisexuality (Morgenroth et al. 2021, p. 1). However, direct assessment of brain function employing fMRI (Safron et al. 2018) confirms separate neural patterns of heterosexual, bisexual, and homosexual orientation. This supports the alternative view—that the gender difference in the distribution of bisexuality is probably due to inherent biological underpinnings, not socialization. Our respondents themselves echo this conclusion. We have reported elsewhere (Bradshaw et al. 2016) their views about the etiology of same-sex attraction, as a general rule and as relating to themselves personally. A biological explanation was the most frequent choice (81–75%) for both men and women.

In addition to a higher prevalence of bisexuality, women also reported passing sexual identity development milestones 2–3 years later than the men, although that gap was much shorter for those ages 18–30 in the sample. Earlier disclosure in this subgroup likely represents increasing societal acceptance of sexual diversity in recent years. The patterns of disclosure were similar for men and women. Bisexual participants, however, were significantly less open, and most reported sexual attraction at the low end of the Kinsey Scale. This, in turn, appears to mediate relationship options; 61% of the women reported being in a committed sexual relationship with a partner/spouse compared to 46% of the men.

We submit that our findings make an important contribution by demonstrating how inherent gender differences in the distribution of sexual orientation are manifested in religious belief and practice. The greater incidence of bisexuality in women permits a greater accommodation to the conventions of their religious lives—in disclosure, entering heterosexual marriage, and continued affiliation. These insights are not only valuable to the individuals involved but should also be very useful to their church leaders and those offering professional counseling.

These results concerning bisexuality lead us to offer an observation about the sex distribution of respondents in LGBTQ research surveys (ours and others) obtained through convenience sampling. Examples are provided in Table 7. The results of this canvass are remarkably consistent: men outnumber women three to one as respondents—this in the face of current evidence that the percentages of non-heterosexual men and women are equal (Gates 2011; Ward et al. 2014). We explore here plausible explanations for the apparent reluctance of women to participate in these academic inquiries.

Table 7.

Only about 25% Of Respondents in Studies Using Convenience Sampling Are Female.

It would appear that there are several reasons why older lesbian and bisexual women may not self-identify as such. It may be, especially in older generations, that non-heterosexual women were less stigmatized than men. Women who remain unmarried into their thirties (and cohabitate with other women) have probably been less subject to societal suspicion or condemnation (Quinn 1996). National surveys conducted by Pew Research (Parker 2015) reveal the following: “Bisexuals are much less likely (20%) than gay men (48%) and lesbians (50%) to say that their sexual orientation is an important part of who they are”. Moreover, they “are also much less likely than gay men or lesbians to have ‘come out’ to the important people in their lives” or to have experienced discrimination (being subjected to slurs or jokes or being treated unfairly by an employer). These data also revealed that, at least prior to the legalization of same-sex marriage in the U.S. in 2015, 32% of bisexual women were married compared to 23% of bisexual men, or to 4% and 6% of gay men and lesbians, respectively. A significant proportion of bisexual women, therefore, remain invisible (closeted) with respect to their sexuality and are less prone to identify as gay or to participate in a study of non-heterosexuals.

10. Sexual Orientation Change Efforts

Respondents utilized a range of SOCE in order to meet the heteronormative expectations in their families and broader communities. This is in response to the negative messaging about same-sex sexuality circulating in their CJCLDS surroundings (Mattingly et al. 2015). For most of these strategies, women participated for shorter periods of time and reported their efforts as less effective, perhaps because they experienced less pressure to conform to the standards required for CJCLDS missionary service. Only 4 women and 28 men (of about 750 who provided written explanations) reported any claim of change. All were in the bisexual range of the Kinsey continuum. Their claims were for outcomes other than an alteration in erotic feeling (i.e., reduced same-sex behavior or reduced anxiety about same-sex attraction). Following their study of a small sample of CJCLDS LGBT individuals, Beckstead and Morrow (2004, p. 1) advocated for “a broader-based treatment approach (besides one focused solely on changing sexual orientation or adopting a lesbian, gay, or bisexual identity), which is designed to produce individualized congruent solutions for religiously conflicted, same-sex-attracted clients,” a strategy consistent with the recommendations of Lefevor et al. (2019b).

11. Relationship to the Church

Status in the church was strongly linked to scores on the Kinsey scales for both men and women. Average Kinsey scores were in the low range for those who were active and in the high range for those who had disaffiliated. Some bisexual individuals were in heterosexual partnerships and thereby fit into the LDS norms for traditional family life. Nevertheless, fewer women than men were active, and more had their membership sanctioned or had resigned. We have reported elsewhere (Bradshaw et al. 2021) other differences in religiosity. Women reported lower levels of belief in core CJCLDS doctrines and lower self-reports of religious orthodoxy, and more indicated they had no denominational affiliation. These observations suggest the influence of other factors not directly related to sexuality. For one, it is likely that women were also marginalized by a sense of inequality because of the patriarchal nature of the church, in which men hold most leadership positions. Jacobsen (2017) found this to be one relevant consideration for the fact that some sexual minority LDS women experienced a loss of community support which led to a reduction in their sense of well-being. Differences in other personality traits among LGBTQ individuals may also be in play (Lippa 2020).

12. Mixed-Orientation Marriage

The data for marital status also reflect differences across the spectrum of sexual orientation for both men and women. Those positioned at the low to mid end of the Kinsey Scale were most likely to have remained in a mixed-orientation marriage. A gender difference was observed for those currently married heterosexually: among women, a greater percentage (62%) were bisexual compared to men (35%). This analysis complements earlier work on mixed-orientation marriage among current or former members of the CJCLDS. With a sample of 240 persons in such a relationship who were recruited online, Legerski et al. (2017) obtained valuable insights about variations in reasons for marriage, the disclosure experience, and levels of attraction and attitudes toward sex in both the LGBQ and heterosexual partners. Among their findings were that previously married LGBQ partners, who had experienced pressure to marry as a solution to manage their sexuality, reported lower attraction and higher levels of aversion to their opposite-sex spouses. Only one third of currently married heterosexual partners learned of their spouse’s orientation before marriage. Subsequent disclosure left many less secure about their own attractiveness. Subsequently, A. Dehlin et al. (2018) described same- and other-sex aversion and attraction in a subset of the same sample. Higher other-sex attraction and attraction to the spouse were associated with better relationship quality for both men and women in intact marriages, confirming the conclusion in the present study of the role of bisexuality. The results of personal interviews with a subset of these respondents demonstrated that “most couples maintain an outward appearance of heteronormality; some view their private departure from the traditional gender order as a benefit to their relationship, whereas others view it as a source of strain and work hard to minimize gender deviance in their roles” (Legerski and Harker 2018, p. 482). There is clearly diversity in the ability of different persons to navigate the intersection of their religious beliefs and personal experience. Analysis of comparative data from another recent survey of CJCLDS sexual minority adults (Lefevor et al. 2019a) showed that relationship status dissatisfaction was lower for those in a mixed-orientation relationship than for those who were single (either celibate or not celibate), but greater than that for those in a same-sex relationship.

13. Mental Health

Measures of depression, anxiety, sexual identity distress, and internalized homophobia for both men and women were lower for those who disaffiliated from the Church, and for those who maintain committed same-sex relationships. Measures of quality of life and self-esteem followed the opposite pattern. These results confirm the findings of a California Health Interview Survey (Wright et al. 2013) which found significantly less psychological distress in LGB persons who were legally married compared to those not in a legal relationship. The same was true for married heterosexuals compared to those who were single. These findings are also consistent with the work Hamblin and Gross (2013, p. 817), who found that “Those who attend rejecting faith communities attended services less often, experienced greater identity conflict, and reported significantly less social support than those of the Accepted [accepting faith communities] group.”

(Jacobsen and Wright 2014; Jacobsen 2017) reported the results of in-depth interviews conducted with 23 same-sex attracted current or former CJCLDS women. Most experienced conflict, including internalized homophobia, between their religious and sexual identities. In a study of factors impacting the mental health of same-sex attracted CJCLDS adults (n = 142), Grigoriou (2014) determined that social constraints were the best predictor for symptoms of anxiety and depression: “... SSA Mormons cannot speak about their sexual minority status because their religious society teaches them to (a) silence sexually atypical thoughts (b) “control” sexually atypical behavior, and (c) comply with LDS established norms” (p. 477). That the issue of mental health in the LGBTQ community is highly complex, however, is highlighted by the work of Joseph and Cranney (2017). In a sample of 348, they found equal levels of self-esteem among sexual minority Mormons and ex-Mormons, achieved through different pathways. The group maintaining church activity reported higher family support and lower SSA identity acceptance. The disaffiliated cohort reported a higher positive level of sexual identity, having been less exposed to the negative messaging emanating from the Church.

While some LGBTQ persons have experienced such a degree of conflict that they feel reconciliation with religious faith is not possible, others have found ways to successfully navigate between their sexual and spiritual identities, some through institutional participation and others through private devotion. Rodriguez (2010) described one such pathway as follows: “These “gay Christians” have carved out safe spaces where they can practice a version of Christianity that neither condemns nor simple tolerates homosexuality, but instead embraces homosexuals as having been created in God’s image” (p. 26).

14. Limitations

The data used in this study were collected ten years ago. However, they are still relevant. The present focus on the difference in the experiences of the men and women respondents represents a unique analysis not addressed in previous publications. Equally important, we submit that the policies of CJCLDS leaders (see the recent address by Jeffrey R. Holland—Church News 2021) and the resulting attitudes of its members have not changed materially in the intervening period.

The recruitment design (convenience) of this study limits generalization to LGBTQ Mormons at large. Note, however, that the data represent a relatively large sample size, and the diversity of sources from which participants were obtained suggests that they are highly representative of the target population. Respondents were primarily highly educated and affluent. Persons of color and non-U.S. residents are under-represented, along with those who do not participate in online communication. Closeted persons, especially women as detailed above, likely choose not to respond to a survey requiring them to disclose highly personal information. Retrospective self-reports are subject to some degree of inaccuracy. In spite of the unique aspects of CJCLDS doctrine and practice, we are hopeful that our findings will find application to other religious faiths.

15. Conclusions

One important aspect of sexual complexity is that the etiology of orientation in women is probably different than it is in men. In our sample, women reported a significantly higher incidence of bisexuality than men, probably due to the intersection of distinctive biological mechanisms and unique socialization experiences. We found that in the religious and social context of the CJCLDS, this sexuality difference often finds qualitative expression in the following ways. Self-reported bisexual women are less likely to disclose their minority status and more likely to remain in a mixed-orientation marriage. In that way, they comply with the heteronormative expectations of the community and remain active in the church. However, other bisexual women and those who are lesbian (self-reporting as a 5 or 6 on the Kinsey Scale), who do not conform to the notions of gender exceptionalism and traditional expectations of CJCLDS women as wives and mothers, are more likely to disaffiliate. The evidence is that mental health improves as a result. Although these same forces are in play among sexual minority LDS men, other variables, such as the effect of missionary service (Bradshaw et al. 2015), further complicate their behaviors. These insights about differences between men and women should be helpful to therapists who are assisting sexual minority clients from conservative religious backgrounds.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/rel13060561/s1, Table S1: Survey Sources.

Author Contributions

W.S.B.: Original draft preparation, data collection and analysis. J.P.D.: Data collection and analysis; R.V.G.: Review and editing, data collection and analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The approval number for our study with Utah State University IRB is 2906.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- APA Task Force on Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation—APA. 2009. Report of the Task Force on Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, J. Michael, and Jeremy Jabbour. 2020. Reply to Zietsch and Sidari: Male sexual arousal patterns (and sexual orientation) are partly unidimensional. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117: 27081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, J. Michael, Paul L. Vasey, Lisa M. Diamond, S. Marc Breedlove, Eric Vilain, and Marc Epprecht. 2016. Sexual orientation, controversy, and science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest 17: 45–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Balthazart, Jacques. 2016. Sex differences in partner preference in humans and animals. Philosophical Transactions Royal Society B 371: 20150118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barron, Andrew. 2019. Sexuality is complex. New Scientist 243: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckstead, A. Lee, and Susan L. Morrow. 2004. Mormon Clients’ Experiences of Conversion Therapy: The Need for a New Treatment Approach. The Counseling Psychologist 32: 651–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, Kate, John P. Dehlin, Katherine A. Crowell, Renee V. Galliher, and William S. Bradshaw. 2014. Sexual orientation change efforts through psychotherapy for LGBQ individuals affiliated with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy 41: 391–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, William S., Nicholas Norman, John P. Dehlin, Renee V. Galliher, and Katherine A. Crowell. 2016. Social Reactions, Etiological Perceptions, and Spiritual Perspectives in an LGBTQ Mormon Sample. In Sexual Orientation: Perceptions, Discrimination, and Acceptance. Edited by Frances Earley. Hauppage: Nova Scientific Publishers, Inc., chp. 1. pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, William S., Renee V. Galliher, and John P. Dehlin. 2021. Differences in Religious Experience between Men and Women in a Sexual Minority Sample of Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Journal of GLBT Family Studies 7: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, William S., Tim B. Heaton, Ellen Decoo, John P. Dehlin, Renee V. Galliher, and Katherine A. Crowell. 2015. Religious Experience of GBTQ Mormon Males. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54: 311–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breedlove, S. Marc. 2017. Prenatal influences on human sexual orientation: Expectations versus data. Archives of Sexual Behavior 46: 1583–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, James G., G. Tyler Lefevor, and Ronald L. Schow. 2019. Sexual Satisfaction and Mental Health in Mixed-Orientation Relationships: A Mormon Sample of Sexual Minority Partners. Journal of Bisexuality 19: 515–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, James G., G. Tyler Lefevor, Ronald L. Schow, and Christopher H. Rosik. 2020. Identity affirmation and mental health among sexual minorities: A raised-Mormon sample. Journal of GLBT Family Studies 16: 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burckhardt, Carol S., and Kathryn L. Anderson. 2003. The Qualityof Life Scale (QOLS): Reliability, validity, and utilization. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 1: 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Buxton, Amity Pierce. 2001. Writing our own script: How bisexual men and their heterosexual wives maintain their marriage after disclosure. Journal of Bisexuality 1: 155–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, Amity Pierce. 2004. Work in progress: How mixed-orientation couples maintain their marriage after their wives come out. Journal of Bisexuality 4: 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, A. Dean. 2001. Homosexuality and the Church of Jesus Christ. Springville: Bonneville Books. [Google Scholar]

- Church News. 2021. Available online: https://www.thechurchnews.com/leaders-and-ministry/2021-08-23/elder-holland-byu-university-conference-love-lgbtq-223095 (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Cook, Christopher C. H. 2021. The causes of human sexual orientation. Theology & Sexuality 27: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Cranney, Stephen. 2017. The LGB Mormon paradox: Mental physical, and self-rated health among Mormon and Non-Mormon LGB individuals in the Utah Behavioral Risk Facto Surveillance System. Journal of Homosexuality 64: 731–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowell, Katherine A., Renee V. Galliher, John P. Dehlin, and William S. Bradshaw. 2014. Specific aspects of minority stress associated with depression among LDS-affiliated non-heterosexual adults. Journal of Homosexuality 62: 242–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, Angie, and Renee Galliher. 2010. Sexual minority young adult religiosity, sexual orientation conflict, self-esteem and depressive symptoms. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Mental Health 14: 271–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahle, Dennis V., A. Dean Byrd, Shirley E. Cox, Doris R. Dant, William C. Duncan, John P. Livingstone, and Gawain W. Wells. 2009. Understanding Same-Sex Attraction. Salt Lake City: Foundation for Attraction Research. [Google Scholar]

- Dehlin, Audrianna J., Renee V. Galliher, Elizabeth Legerski, Anita Harker, and John P.Dehlin. 2018. Same-and other-sex aversion and attraction as important correlates of quality and outcomes of Mormon mixed-orientation marriage. Journal of GLBT Family Studies 15: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehlin, John P., Renee V. Galliher, William S. Bradshaw, and Katherine A. Crowell. 2014a. Psychosocial correlates of religious approaches to same-sex attraction: A Mormon perspective. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health 18: 284–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehlin, John P., Renee V. Galliher, William S. Bradshaw, and Katherine A. Crowell. 2015. Navigating sexual and religious identity conflict: A Mormon perspective. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research 15: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehlin, John P., Renee V. Galliher, William S. Bradshaw, Daniel C. Hyde, and Katherine A. Crowell. 2014b. Sexual Orientation Change Efforts among Current or Former Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Journal of Counseling Psychology 62: 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, Lisa M., and Clifford J. Rosky. 2016. Scrutinizing immutability: Research on sexual orientation and US. Legal advocacy for sexual minorities. The Journal of Sex Research 53: 363–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobner, Jennifer. 2015. New Mormon Policy Makes Apostates of Married Same-Sex Couples, Bars Children from Rites. Available online: http://archive.sltrib.com/article.php?id=3144035&itype=CMSID (accessed on 7 November 2015).

- Dwyer, Colin. 2020. Utah Becomes Latest State To Ban Discredited LGBTQ “Conversion Therapy”. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2020/01/22/798603313/utah-becomes-latest-state-to-ban-discredited-lgbtq-conversion-therapy (accessed on 25 January 2020).

- Eternal Marriage: Student Manual. n.d.Available online: https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/the-eternal-family-teacher-manual/lesson-8-gender-and-eternal-identity?lang=eng (accessed on 26 January 2020).

- First Presidency. 2019. First Presidency Shares Messages From General Conference Leadership Session. A Message From the First Presidency. April 4. Available online: https://www.mormonnewsroom.org/article/first-presidency-messages-general-conference-leadership-session-april-2019 (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Gates, Gary J. 2011. How Many People Are Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender. Available online: https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/research/census-lgbt-demographics-studies/how-many-people-are-lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender/ (accessed on 5 June 2011).

- Gehrke, R., and J. Dobner. 2015. New anti-bias bill praised as a ‘model’. Salt Lake Tribune, March 13. [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriou, Jennifer A. 2014. Minority stress factors for same-sex attracted Mormon adults. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 1: 471–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafen. 2009. Elder Bruce C. Hafen Speaks on Same-Sex Attraction. Available online: https://www.mormonnewsroom.org/article/elder-bruce-c-hafen-speaks-on-same-sex-attraction (accessed on 25 September 2009).

- Halkitis, Perry N., Jacqueline S. Mattis, Joel K. Sahadath, Dana Massie, Lina Ladyzhenskaya, Kimberly Pitrelli, Meredith Bonacci, and Sheri-Ann E. Cowie. 2009. The meanings and manifestations of religion and spirituality among lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender adults. Journal of Adult Development 16: 250–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamblin, Rebecca, and Alan M. Gross. 2013. Role of religious attendance and identity conflict in psychological well-being. Journal of Religion and Health 52: 817–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammarberg, M. 2008. The current crisis in the formation and regulation of Latter-day Saints’ sexual identity. In Revisiting Thomas F. O Dea’s the Mormons. Edited by Cardell K. Jacobson, John P. Hoffmann and Tim B. Heaton. Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, Barbara Couden, Naomi J. Schwenke, and Colwick M. Wilson. 2011. Spouses in mixed-orientation marriage: A 20-year review of empirical studies. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 37: 307–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinckley, Gordon B. 1987. Reverence and Morality. The Ensign 17: 45. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbour, Jeremy, Luke Holmes, David Sylva, Kevin J. Hsu, Theodore L. Semon, A. M. Rosenthal, Adam Safron, Erlend Slettevold, Tuesday M. Watts-Overall, Ritch C. Savin-Williams, and et al. 2020. Robust evidence for bisexual orientation among men. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117: 18369–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, Jeanna. 2017. Community influences on Mormon women with same-sex sexuality. Culture, Health, and Sexuality 19: 1314–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, Jeanna, and Rachel Wright. 2014. Mental Health Implications in Mormon Women’s Experiences With Same-Sex Attraction: A Qualitative Study. Counseling Psychologist 42: 664–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Stanton L., and Mark A. Yarhouse. 2011. A longitudinal study of attempted religiously mediated sexual orientation change. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy 37: 404–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, Lauren J., and Stephen Cranney. 2017. Self-esteem among lesbian, gay, bisexual and same-sex-attracted Mormons and ex-Mormons. Mental, Health, Religion, and Culture 20: 1028–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just the Facts Coalition. 2008. Just the Facts about Sexual Orientation and Youth: A Primer for Principals, Educators, and School Personnel. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Kimball, Spencer W. 1969. The Miracle of Forgiveness. Salt Lake City: Bookcraft. [Google Scholar]

- King, Michael, Joanna Semlyen, Sharon See Tai, Helen Killaspy, David Osborn, Dmitri Popelyuk, and Irwin Nazareth. 2008. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self-harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry 8: 70. Available online: https://link-gale-com.erl.lib.byu.edu/apps/doc/A184771981/AONE?u=byuprovo&sid=AONE&xid=f783d5e0 (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Kissil, Karni, and Haya Itzhaky. 2015. Experiences of the marital relationship among orthodox Jewish gay men in mixed-orientation marriages. Journal of GLBT Family Studies 11: 151–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KSL. 2018. Available online: https://www.ksl.com/article/46358409/lds-church-donates-25k-to-lgbt-advocacy-group-in-effort-to-prevent-suicide (accessed on 15 July 2018).

- LDS Social Services. 1990. Keys to Understanding Homosexuality. Fayette: LDS Social Services. [Google Scholar]

- LDS Social Services. 1995. Understanding and Helping Individuals with Homosexual Problems. Fayette: LDS Social Services. [Google Scholar]

- Lefevor, G. Tyler, A. Lee Beckstead, Ronald L. Schow, Marybeth Raynes, Ty R. Mansfield, and Christopher H. Rosik. 2019a. Satisfaction and health within four sexual identity relationship options. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy 16: 355–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefevor, G. Tyler, Isabelle Blaber, Caldwell Huffman, Ronald Schow, A. Lee Beckstead, Marybeth Raynes, and Christopher H. Rosik. 2019b. The role of religiousness and beliefs about sexuality in well-being among sexual minority Mormons. The Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 12: 460–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefevor, G. Tyler, Sydney A. Sorrell, Grace Kappers, Ashley Plunk, Ronald Schow, Christopher H. Rosik, and A. Lee Beckstead. 2020. Same-sex attracted, not LGBQ: The association of sexual identity labeling on religiousness, sexuality and health among Mormons. Journal of Homosexuality 67: 940–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legerski, Elizabeth, and Anita Harker. 2018. The intersection of gender, sexuality, and religion in Mormon mixed-sexuality marriages. Sex Roles 78: 482–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legerski, Elizabeth, Anita Harker, Catherine Jeppsen, Andrew Armstrong, John P. Dehlin, Kelly Troutman, and Renee V. Galliher. 2017. Mormon mixed-orientation marriages: Variation in attitudes and experiences by sexual orientation and current relationship status. Journal of GLBT Family Studies 13: 186–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippa, Richard A. 2007. The relation between sex drive and sexual attraction to men and women: A cross-national study of heterosexual, bisexual, and homosexual men and women. Archives of Sexual Behavior 36: 209–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippa, Richard A. 2013. Men and women with bisexual identities show bisexual patterns of sexual attraction to male and female “swimsuit models”. Archives of Sexual Behavior 42: 187–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippa, Richard A. 2020. Interest, personality, and sexual traits that distinguish heterosexual, bisexual, and homosexual individuals: Are there two dimensions that underlie variations in sexual orientation? Archives of Sexual Behavior 49: 607–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locke, Benjamin D., Andrew A. McAleavey, Yu Zhao, Pui-Wa Lei, Jeffrey A.Hayes, Louis G.Castonguay, and Lin Yu-Chu. 2012. Development and initial validation of the counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms-34. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development 45: 151–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, Mckay S., Renee V. Galliher, John P. Dehlin, Katherine A. Crowell, and William S. Bradshaw. 2015. A Mixed Methods Analysis of the Family Support Experiences of GLBTQ Latter Day Saints. Journal of GLBT Family Studies 12: 386–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mays, Vickie M., and Susan D. Cochran. 2001. Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health 91: 1869–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, S. 2015. A New Jersey Jury Just Dealt a Serious Blow to Gay Conversion Therapy. Available online: www.motherjones.com/politics/2015/06/new-jersey-gay-conversion-therapy-consumer-fraud-jonah (accessed on 10 July 2015).

- Mohr, Jonathan, and Ruth Fassinger. 2000. Measuring dimensions of lesbian and gay male experience. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development 33: 66–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenroth, Thekla, Teri A. Kirby, Maisie J. Cuthbert, Jacob Evje, and Arielle E. Anderson. 2021. Bisexual erasure: Perceived attraction patterns of bisexual women and men. European Journal of Social Psychology 52: 249–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NARTH. 2012. Statement on Sexual Orientation Change. January 27. Available online: http://narth.com/2012/01/narth-statement-on-sexual-orientation-change/ (accessed on 15 March 2012).

- Ngun, Tuck C., and Eric Vilain. 2014. The biological basis of human sexual orientation: Is there a role for epigenetics? Advances in Genetics 86: 167–84. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolosi, Joseph, A. Dean Byrd, and Richard W. Potts. 2000. Retrospective self-reports of changes in homosexual orientation: A consumer survey of conversion therapy clients. Psychological Reports 86: 1071–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, Rocky. 1994. The abominable and detestable crime against nature: A brief history of homosexuality and Mormonism, 1840–1980. In Multiply and Replenish: Mormon Essays on Sex and Family. Edited by Brent Corcoran. Salt Lake City: Signature Books, pp. 123–70. [Google Scholar]

- Oaks, Elders Dallin H., and Lance B. Wickman. 2006. Same-Gender Attraction. Available online: http://www.lds.org/newsroom/issues/answer/0,19491,6056-1-202-4-202,00.html (accessed on 28 November 2006).

- Packer, Boyd K. 1998. “To the One.” BYU 12-Stake Fireside. Available online: https://speeches.byu.edu/talks/boyd-k-packer/say-unto-one (accessed on 29 March 2015).

- Pan American Health Organization. 2012. “Cures” for an Illness That Does Not Exist. Available online: http://new.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=17703&Itemid (accessed on 19 August 2018).

- Parker, Kim. 2015. Among LGBT Americans, Bisexuals Stand out When It Comes to Identity, Acceptance. Available online: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/02/20/among-lgbt-americans-bisexuals-stand-out-when-it-comes-to-identity-acceptance/ (accessed on 20 March 2015).

- Polderman, Tinca J. C., Baudewijntje P. C. Kreukels, Michael S. Irwig, Lauren Beach, Yee-Ming Chan, Eske M. Derks, Isabel Esteva, Jesse Ehrenfeld, Martin Den Heijer, Danielle Posthuma, and et al. 2018. The biological contributions to gender identity and gender diversity: Bringing data to the table. Behavioral Genetics 4: 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prince, Gregory A. 2019. Mormons and Gays: A Turbulent Interface. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, D. Michael. 1996. Same-Sex Dynamics among Nineteenth Century Americans: A Mormon Example. Chicago: University of Illinois. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, Qazi, Yin Xu, Richard A. Lippa, and Paul L. Vasey. 2020. Prevalence of sexual orientation across 28 Nations and its association with gender equality, economic development, and individualism. Archives of Sexual Behavior 49: 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Religion News. 2020. Available online: https://religionnews.com/2020/02/19/new-lds-handbook-softens-some-stances-on-sexuality-doubles-down-on-transgender-members/ (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Rice, William R., Urban Friberg, and Sergey Gavrilets. 2012. Homosexuality as a consequence of epigenetically canalized sexual development. The Quarterly Review of Biology 86: 343–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Riggle, Ellen D. B., Joy S. Whitman, Amber Olson, Sharon Scales Rostosky, and Sue Strong. 2008. The positive aspects of being a lesbian or gay man. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 39: 210–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodriguez, Eric M. 2010. At the intersection of church and gay: A review of the psychological research on gay and lesbian Christians. Journal of Homosexuality 57: 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. 1965. Society and Adolescent Child. Prineton: Princeton Univeristy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, A. M., David Sylva, and Adam Safron. 2012. The male bisexuality debate revisited: Some bisexual men have bisexual arousal patterns. Archives of Sexual Behavior 41: 135–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Caitlin, David Huebner, Rafael M. Diaz, and Jorge Sanchez. 2009. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics 123: 346–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Caitlin, Russell B. Toomey, Rafael M. Diazand, and Stephen T. Russell. 2018. Parent-Initiated Sexual Orientation Change Efforts With LGBT Adolescents: Implications for Young Adult Mental Health and Adjustment. Journal of Homosexuality 67: 159–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Caitlin, Stephen T. Russell, David Huebner, Rafael Diaz, and Jorge Sanchez. 2010. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing 23: 205–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safron, Adam, Victoria Klimaj, David Sylva, A. M. Rosenthal, Meng Li, Martin Walter, and J. Michael Bailey. 2018. Neural Correlates of Sexual Orientation in Heterosexual, Bisexual, and Homosexual Women. Scientific Reports 8: 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scheitle, Christopher, and Julia Kay Wolf. 2018. Religion and sexual identity fluidity in a national three-wave panel of U.S. adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior 47: 1085–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuck, Kelly D., and Becky J. Liddle. 2001. Religious conflicts experienced by lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy 5: 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serovich, Julianne M., Shonda M. Craft, Paula Toviessi, Rashmi Gangamma, Tiffany McDowell, and Erika L. Grafsky. 2008. A systematic review of the research base on sexual reorientation therapies. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 34: 227–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shidlo, Ariel, and Michael Schroeder. 2002. Changing sexual orientation: A consumers’ report. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 33: 249–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine—SAHM. 2013. Recommendations for promoting the health and well-being of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescents: A position paper of the society for adolescent health and medicine. Journal of Adolescent Health 52: 506–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, Robert L. 2003. Can some gay men and lesbians change their sexual orientation? 200 participants reporting a change from homosexual to heterosexual orientation. Archives of Sexual Behavior 32: 403–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Suzanne, and A Jordan Wright. 2018. Discrete effects of religiosity and spirituality on gay identity and self-esteem. Journal of Homosexuality 65: 1071–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supreme Court. 2019. Available online: https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/18/18-107/113604/20190826131230679_Harris%20Amicus%20Brief%20Final%20Version.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2020).

- Swan, Thomas B., and Suzanne Benack. 2012. Renegotiating identity in unscripted territory: The predicament of queer men in heterosexual marriages. Journal of GLBT Family Studies 8: 46–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 1992. Understanding and Helping Those Who Have Homosexual Problems. Suggestions for Ecclesiastical Leaders. Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. [Google Scholar]

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 1995. The Family: A Proclamation to the World. Available online: https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/bc/content/shared/content/english/pdf/36035_000_24_family.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2018).

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 2007. God Loveth His Children. Available online: http://www.lds.org/portal/site/LDSOrg/menuitem.b3bc55cbf541229058520974e44916a0/? (accessed on 20 March 2015).

- Time 100. 2019. Why the LDS Church Supports Utah’s Conversion Therapy Ban|Time. Available online: https://time.com/5741789/utah-conversion-therapy-ban-lds/ (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Tskhay, Konstantin O., and Nicholas O. Rule. 2015. Sexual orientation across culture and time. In Psychology of Gender Through the Lens of Culture: Theories and Applications. Edited by Saba Safdar and Natasza Kosakowska-Berezecka. New York: Springer International Publishing, pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, Brian W., James M. Dahlhamer, Adena M Galinsky, and Sarah S. Joestl. 2014. Sexual orientation and health among U.S adults. National Health Interview Survey 77: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wolkomir, Michelle. 2009. Giving it up to god”: Negotiating femininity in support groups for wives of ex-gay Christian men. Gender and Society 18: 735–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Eric R., and Brea L. Perry. 2006. Sexual identity distress, social support, and the health of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. Journal of Homosexuality 51: 81–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Richard G., Allen Leblanc, and Lee Badgett. 2013. Same-sex legal marriage and psychological well-being: Findings from the California health interview survey. American Journal of Public Health 103: 339–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarhouse, Mark A., Christine H. Gow, and Edward B. Davis. 2009. Intact marriages in which one partner experiences same-sex attraction: A 5-year follow-up study. Family Journal 17: 329–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).