Abstract

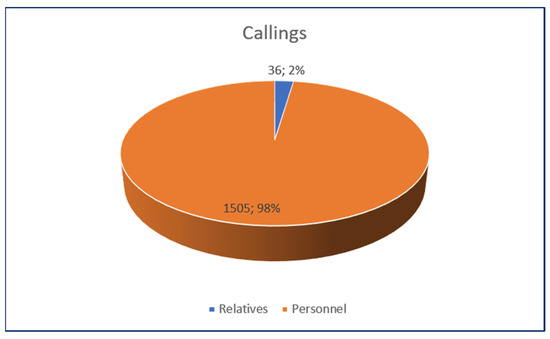

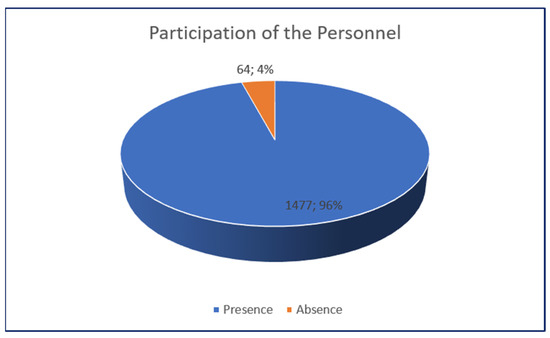

In the A. Gemelli university hospital in Rome, the presence of highly specialized inter-professional palliative care teams and spiritual assistants who are dedicated to their role in the service of inpatients is valuable to person-centered healthcare. Spiritual needs are commonly experienced by patients with sudden illness, chronic conditions, and life-limiting conditions, and, consequently, spiritual care is an intrinsic and essential component of palliative care. This paper focuses on the sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick to demonstrate the importance of spiritual care as an integral part of palliative care and highlights the need for all interdisciplinary team members to address spiritual issues in order to improve the holistic assistance to the patient. Over a 3-year period (October 2018–September 2021), data about the sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick administered by the hospitaller chaplaincy were collected. A total of 1541 anointings were administered, with an average of 514 anointings per year, excluding reductions related to the COVID-19 pandemic. In 98% of cases, the sacrament was requested by health personnel, and in 96% of cases, the same health personnel participated in the sacrament. These results demonstrate that, at the A. Gemelli polyclinic in Rome, the level of training that the care team has received in collaboration with the chaplains has generated a good generalized awareness of the importance of integrating the spiritual needs of patients and their families into their care, considering salvation as well as health, in a model of dynamic interprofessional integration.

1. Introduction

The spiritual dimension is an integral aspect of human life that gives meaning to the entirety of a person’s existence, and spiritual needs are commonly experienced by patients with sudden illness, bereavement, chronic conditions, and life-limiting conditions (Best et al. 2020). Spiritual care is an intrinsic and essential component of palliative care. Indeed, according to the WHO, palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families when facing problems that are associated with life-threatening illness through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of the early identification, assessment, and treatment of pain and other physical, psychosocial, and spiritual needs (Sepulveda et al. 2002).

Palliative care is the active holistic care of individuals across all ages with serious health-related suffering due to severe illness and especially of those near the end of their lives. It aims to improve the quality of life of patients, their families, and their caregivers (Radbruch et al. 2020).

Cicely Sounders, the founder of modern palliative care, identified multi-dimensional spiritual suffering at the end of life as “total pain”.

David Clark, an authority on the life of Cicely Saunders, states that the meaning of her work is sought in the exploration of “a deep and enduring connection between personal biography, spiritual life and ethics of care” (Clark 2005). Her work marked a turning point in palliative care thanks to the effectiveness of regular pain treatment, the acknowledgment of the “total pain” of the dying, and of the potential healing power of relationships (Miccinesi et al. 2020). “Total pain” is one of Saunders’s expressions that is used to describe comprehensive care for the dying, originating from the recent developments in spirituality in palliative care (Clark 1999). Spirituality is intended as a network that connects all aspects of life and expands into each dimension of the human being—somatic, psychological, and sociocultural—and well-fitting the notion of the unity of the multi facets of the human being. In Saunders’s vision, spirituality is anchored to both personal reality, which describes the commitment to achieve personal goals and visions, and social reality, in the way that it is experienced by the community, in which personal inspirations, mediation, and historical realization are attained (Saunders 2005).

Spirituality is multidimensional, consisting of existential challenges, value-based considerations and attitudes, religious considerations, and foundations. The COVID-19 crisis has amplified the importance of palliative care to patients who are suffering and dying from this disease and had also underscored the need to recommit to spiritual care as an essential component of whole-person palliative care. As COVID-19-related deaths have increased globally, there is a widening chasm between the experience of suffering in the outside world and the inside world of patients, families, and clinicians. During the COVID-19 crisis, the thin veil between clinicians, patients, and patients’ families has fallen, and all feel involved in the same “war”. The “inside world” of a patient necessitates integral medical and spiritual/religious care that should involve many people. The COVID-19 crisis brought the phrase “No atheist in the foxhole” to the foreground for many. So loud can be the echo of unmet spiritual care needs that any palliative specialist should take it into consideration as a fundamental part of their practice (Ferrel et al. 2020).

A multidisciplinary model of spiritual care works within a holistic or bio-psycho-social spiritual model of the human being and recognizes that all members of a clinical team have a responsibility for spiritual care, though they may have different levels of expertise (Best et al. 2020). Prolonged exposure to the physical symptoms and pain as well as the psychological, spiritual, and existential suffering of the dying patient can increase the chance of people in care teams developing post-traumatic stress symptoms and compassion fatigue. The importance of recognizing spirituality as a strategy to deal with and identify patients’ needs is that it assists health professionals, notably nursing professionals, to plan quality support and to deliver integral care to patients (Cross 2019). A spiritual environment in hospitals has been shown to influence nurses’ professional quality of life (Cruz et al. 2020).

Many studies emphasize the important role of spirituality in coping with diseases at advanced stages as well as having a positive impact on patients, family members, and palliative care teams regarding the end-of-life process and in helping them to face the finitude process (Selman et al. 2018; Visser et al. 2017). Interprofessional education on spirituality could contribute to improving compassion and satisfaction among care teams and to decrease compassion fatigue.

In this context, spirituality and religiosity must be distinguished (Chitra et al. 2020; Puchalsky et al. 2014; Steinhauser et al. 2017). Spirituality refers to personal attempts to understand questions about life and their own relation to the sacred and transcendent, which may or may not lead to the development of religious practices. Religiosity corresponds to an organized system of beliefs, practices, rituals, and symbols that are aimed at facilitating closeness between individuals and the sacred or transcendent. Religiosity is the most basic level of religion and concerns the extent to which individuals believe, follow, and practice a given religion (Puchalsky et al. 2009; Koenig 2012).

According to this framework, the main goals of this paper are:

- To highlight, contextualize in the Catholic perspective, and discuss a new pillar of Spirituality in palliative care as an added value: the contribution of the Sacraments for the integral care of the Person, focusing on the Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick;

- To analyze the empirical data collected in the period of October 2018–September 2021, which refer to the Anointings that were administrated at our institution;

- To highlight how the Sacraments fit in the cross-disciplinary context of the interaction between all of the components of the care team, both in the interprofessional education process and in ordinary synergic daily service.

We will consider the palliative care team to be composed of priests and friars, nuns, doctors, nurses, and health personnel who are working in collaboration with each other.

2. Motivational and Contextual Assumptions

We will start furnishing the anthropological and theological basis on which we operate and in which we have developed this study in order to set a clear framework for further analysis and discussion.

2.1. Weakness and Vulnerability as an Occasion for Fullness

Weakness and vulnerability are often considered as limiting conditions for human happiness; in this first paragraph, we will offer a reading in the light of the Incarnation of the Lord Jesus Christ to discover these conditions as an occasion for fullness in the context of care.

The problem of suffering marks human life, making one’s weakness and vulnerability particularly evident. Weakness is linked to the continuous need for new and substantial forces that are lacking, stimulating a continuous search for meaning, which is connatural with human nature itself, even regardless of the suffering or pain that is experienced. Vulnerability, on the other hand, represents a particular condition that exposes humans, similar to any other living being, to disease and, more generally, to the transience of life and therefore also to sin, that is understood as a deviation from the target, which, with respect to the goal, from a Catholic perspective, is a Human Person’s Fullness in Christ. Both are existential conditions that, as such, especially given their problematic nature and their profound influence on human life, impact all of its dimensions in an integral way.

Weakness primarily has to do with the radical dependence of humans, a characteristic that is with them from birth to death, and defines the real anthropology of poverty. It is an anthropological framework that describes “man as a being who is in need, who symbolically expresses himself with the initial cry of the new-born and the final rattle of the dying man … the life of human being is enclosed within two invocations of help” (Zuccaro 2015). The being of man is the question that accompanies him from the first “cry or wailing” as an urgent search for identity and therefore for fullness, a question that involves him in a passionate search throughout his life, marking victories and defeats in a particular way through the streets of pain and suffering, which are where this question becomes more pressing and decisive. Suffering can be an enigmatic paradigm of the amplification of the fundamental question of meaning about our identity as human beings and, above all, of our personal identity, which is so clearly original and unique while being fragile and weak at the same time. In this way, man’s weakness becomes an opportunity that opens up his horizons rather than a limit that forces him, as admirably expressed by St. Paul: “I will rather boast most gladly of my weaknesses, in order that the power of Christ may dwell with me. Therefore, I am content with weaknesses … for the sake of Christ; for when I am weak, then I am strong” (2Cor 12:9–10). Weakness is therefore dependence because it constitutively recalls a relationship that continually moves man ‘from me to you’: “These considerations lead us to the conception of selfhood as a dynamic unity of first-, second-, and third-personal perspectives: I can be a “me” only for a “you”, and only if we are both one of the ‘they’” (Atkins 2008).

As we have also seen, vulnerability characterizes the essential structure of man in terms of exposure to disease, infirmity, and non-equilibrium. However, man is also vulnerable because he is exposed to temptation and therefore to the fall, to the wound, and to the diminution of himself. In the latter sense, “man as a being in need becomes the condition of possibility for the development of a viable moral theology project” (Zuccaro 2015). In fact, something that is closely connected with the frailty of man is the reality of sin, which arises at the level of relationships, interrupting its vital structure for the existentially not-self-sufficient man, both towards God, the first personal, constitutive, subsistent, and vitalizing relationship; towards himself; and finally, towards others.

Weakness and vulnerability are thus synonymous with creaturality, in which man finally finds his explanation in awe in front of the Revelation of God the Trinity.

The Gospel makes us discover how the relational dimension of man is not only constitutive but that it is even primary, as God the Creator is Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit. Man experiences this relationality: “it is God who loves the human being, making him part of the same experience and putting him in the condition to receive and, in turn, to donate” (Zuccaro 2015).

In this context, the Incarnation of the Word of God throws a decisive light on anthropology, in the sense that only “Christ, the final Adam, by the revelation of the mystery of the Father and His love, fully reveals man to man himself and makes his supreme calling clear” (Vatican Council II 1965). The event of Jesus Christ expands the horizons of the existence of mankind and generates a breath of hope that nourishes every heartbeat of human life, projecting it into personal commitment and the construction of increasingly structured networks of relationships to build a communion of Grace: “each person … feels held within a network of solidarity and belonging. Social problems must be addressed by community networks and not simply by the sum of individual good deeds” (Francis 2015).

This network can and must become a real “network of fraternity” that includes care relationships: “But a Samaritan traveler who came upon him was moved with compassion at the sight. He approached the victim, poured oil and wine over his wounds and bandaged them. Then he lifted him up on his own animal, took him to an inn and cared for him” (Lk 10:33–34). It is an innate answer to the original question of God that is addressed to the heart of every man: “Where is your brother?” (Gn 4:9). Very touching is the image of the doctor that, not ever leaving the patient on his own, must be an “obstetrician” to life and also to death (Abiven 1995), and who is aware of having a precious and unique son or daughter of God in his hands with the duty to accompany him/her along the pathway to eternal life.

2.2. The Body in the Unity of the Person: Value and Mission

The above guidelines converge toward the second step, which highlights the importance of the Human Body, not only from the physical point of view but, as we will see in this paragraph, in the context of the unity of the Person.

The light of the Incarnation of Jesus Christ has brightened and resulted in the discovery of the value of the human person, helping us to define man as a unity of soul and body; in fact, “corporeality is the specific way of existing of the human spirit: the body reveals man, expresses the person. Then the person is not configured as pure rationality or as a single body, but as a total unity or better as a unified unity, which thinks, knows, chooses, decides, feels, is afraid, loves, experiences sufferings and unspeakable joys” (Benanti 2016).

The human person is the object of God’s unconditional love and is intrinsically called for this in his inseparable unity, but in order for man to grasp this value and dignity, he needs a revelation that helps him to discover how much and how that interior calling is founded. Therefore, man does not “have” a body, as something foreign and almost as an embarrassment (as in many dualist philosophies), but instead, man “is” a body that is called to the eternity of the Resurrection of bodies, in the same way that Christ himself showed us: “The body is not something that I possess, the body that I live in first person, is myself. [...] the human body fully participates in the realization of the spiritual self and allows it” (Lucas Lucas 2007).

Therefore, thanks to the Incarnation of Christ, the spiritual self is no longer an entity as opposed to the body, but instead, the very whole of a human person receives, lives, and is inhabited by the presence of the Holy Spirit, who animates the “withered bones” (cf. Ez 37) so that always, as on the first day of creation, they may become and be a “living being” (cf. Gn 2:7) or rather a child of God, and “yet so we are” (cf. 1Jn 3:1): “Do you not know that your body is a temple of the holy Spirit within you, whom you have from God, and that you are not your own?” (1Cor 6:19).

Man is an incarnate spirit and is never reducible to a part of him; his dignity in Christ pervades every area of the body and soul precisely as a unified unity, which is called the human person. God the Trinity is the first who takes care of humans, by calling us to do the same towards each other exactly in this ontological and value perspective: ‘Which of these three, in your opinion, was neighbor to the robbers’ victim?’ He answered, ‘The one who treated him with mercy’. Jesus said to him, ‘Go and do likewise’” (Lk 10:36–37).

Touching the body thus means to “touch” the soul, and touching the soul means “touching” the body because of this total unity, which qualifies health care both when the body perceives it and when it seems that it does not, thanks to the contemporary presence of different levels of perception: physical and spiritual, which are intimately connected in the living human person.

3. Expanded Methodology

The present paper deals with a theological and empirical approach to Integral Care, and this paragraph is unusually divided into three sections that explore the coordinates (both motivational and operative) of our concrete and cross-disciplinary method, which is based on the ulteriority of the Sacraments; on the specific Sacrament of the Anointing; and on the empirical data.

3.1. Integral Cross-Disciplinary Care of the Sick: The Ulteriority of the Sacraments in the Training and in the Method of the Care Team

At the A. Gemelli University Polyclinic in Rome, we tried to implement an approach to the Integral Human Person by adding Sacramental content both at the training level and at the operative level. This method will be described here.

The professionalism of the health personnel, the cutting-edge technological resources, and the training of the personnel, which is characterized by sensitivity and clear choices in the direction of respecting the value of human life from its conception to natural death, are all dilated by the light of the Incarnation and Resurrection.

The personnel are supposed to sign the Ethical Code to express their disposal to work in this enlarged context. In addition, the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore offers curricular Theological courses during the first four years of degrees for doctors, nurses, and other health care professions together with continuous assistance for postgraduates and in general at the hospital itself. It is a concrete enlarged formation.

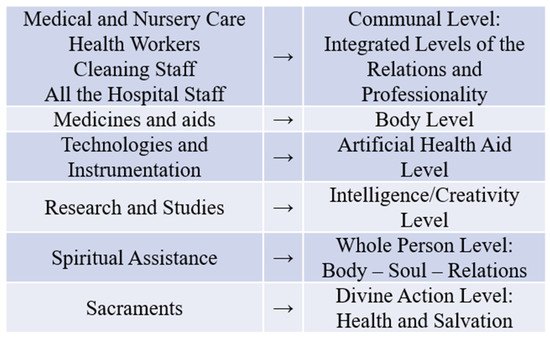

This enhancement is possible thanks to the multiple level extension of the care approach that considers the Polyclinic as a Community (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Multiple level extension of the care approach.

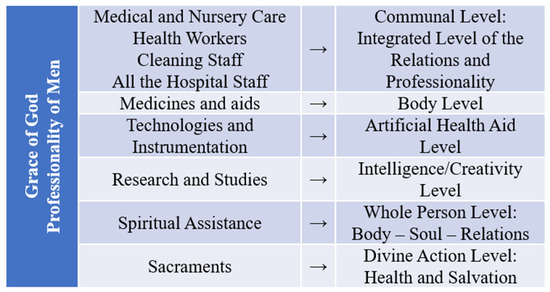

As is the case in the majority of the personnel’s awareness, the consciousness of the intervention of God’s Grace is the “engine” that collects all of these levels into one great Mission, in which Professionality is at the service of the Presence of God that is operating in force of His Incarnation, Resurrection, Gift of the Holy Spirit, and Power of the Sacraments. God acts together with man’s hands and professionality, and this action is in the direction of the mystery of God’s love, who is present, crucified and risen, inside the care process, simply because He said and He promised this. The previous scheme therefore becomes (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Multiple level extension of the care approach enhanced by Grace of God.

What really makes the difference in our proposal with respect to a generic spiritual approach to health care, which is however precious because of its reference to the whole person, is the key factor of the Sacraments. This determines the concrete and effective possibility of the connection between human aid and God’s aid, in which the divine action is widespread at the level of health and at the level of salvation, according to the wisdom and the love of God.

In fact, the Sacraments can be defined in a context where “the mysteries of Christ’s life are the foundations of what he would henceforth dispense in the sacraments, through the ministers of his Church, for ‘what was visible in our Savior has passed over into his mysteries’. Sacraments are ‘powers that comes forth’ from the Body of Christ, which is ever-living and life-giving. They are actions of the Holy Spirit at work in His Body, which is the Church. They are ‘the masterworks of God’ in the new and everlasting covenant” (John Paul II 1992). Additionally, in synthesis, “the sacraments, instituted by Christ and entrusted to the Church, are efficacious signs of Grace perceptible to the senses. Through them divine life is bestowed upon us” (Benedict XVI 2005).

The awareness of the personnel in an integral correlation between their interventions, and divine action is strengthened and is effective precisely because of the availability of the Sacraments as well as with the prayer and human proximity, which are always essential. The sick and their relatives are thus reached by a real initiative of integral care. Divine action is always a mystery in Its ways, and what we consider here is the concrete reference just to the ordinary “instruments” of Its intervention.

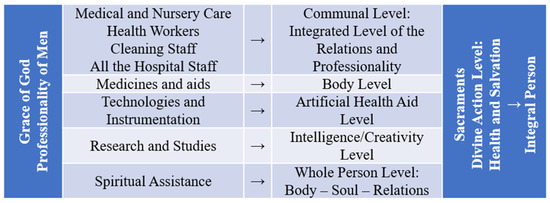

The Sacraments are thus not just something that is added to health care procedures but are instead something (a gift) that embraces the entirety of health care dynamism by conferring structural effectiveness; the Sacraments are in fact related to the integral dimensions of the Person. Finally, our complete approach can consequently be synthesized as follows (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Integral care.

Integral care therefore consists of not only reaching with care due to the sensibility of the personnel and the chaplains but also essentially due to the contribution of the Sacraments. They confer, as we will see, the dimension of God’s action by considering an expanded horizon of life that emerges when the person is living the experience of palliative care.

The Sacraments, as effective signs of salvation, are the concrete instrument that the Catholic Church received from the Lord so that man can today and can always be reached by the living Body of Christ, the body that saves and heals: “Today we are given the possibility of this contact with His body. ‘How do you now, Lord Jesus, take on you my pains in the head, my pains of stomach and heart, my psychoses, my neuroses? How do you get it? How is this contact established?’ … there is a way, par excellence, by which He continues to establish this contact. Always in perfect coherence with the logic of the incarnation that God has not rethought. The logic of the incarnation continues. God does not contradict himself. So, he has chosen a path of incarnation to make real contact with us possible. And these are the Sacraments … The sacraments are the visibility of Him, the way He takes care of us. It is not something that we do for Him. It is something that He does for us” (Viola 2014).

In this way, the Sacraments help us to improve the definition of spirituality and religiosity, conferring a deeper consistence to the approach and to the effects, offering the possibility of spiritual competency training (Selman et al. 2018; Gijsberts et al. 2019) that is oriented to the Truth. They are consequently enriched by the dynamics of gratuitousness in the “logic of the gift”, which do not just come from other people but from the Person of the Living God.

We firmly believe that this surplus is essential in order to give consistency to existential and relational concerns, helping us to transform spiritual and religious care into integral care (Selman et al. 2018).

Through our methodology, we propose stimulating a serious reflection that could be able to go beyond the “religious care” that is intended to be referred to as personal creed in order to think and, in the delicate terrain that is suffering, to search for the Truth (Gijsberts et al. 2019).

3.2. The Meaning and the Method of the Sacrament of the Anointing

The in-hospital Sacraments that are administered by the hospital chaplains in a Catholic context are Baptism, which is performed when the lives of babies are in peril at any stage of their birth and is requested by the parents of these babies; Eucharist, which can be received in the wards every day and specifically on Sunday for those who usually celebrate their participation to the Holy Mass in ordinary life; Confession, which can be lived every day possible in each of the wards for all those who, especially in pain and suffering, need the forgiveness, reconciliation, and the great gift of the Holy Spirit; and Anointing of the Sick, which can be performed during the different stages of disease progression.

Among these Sacraments, the one on which we are focusing our attention in this paper is the Anointing of the Sick, particularly because of the value of this Sacrament, which is correctly understood as being intended for the patient’s health and salvation. We will describe its meaning and its method.

The Anointing of the Sick is in fact a healing Sacrament and has its biblical foundation in Jm 5: 14–15: “The Church believes and confesses that among the seven sacraments there is one especially intended to strengthen those who are being tried by illness, the Anointing of the Sick: ‘This sacred anointing of the sick was instituted by Christ our Lord as a true and proper sacrament of the New Testament. It is alluded to indeed by Mark, but is recommended to the faithful and promulgated by James the apostle and brother of the Lord’” (John Paul II 1992).

There is still little that is known about this Sacrament today because it is often mistakenly confused with a pious recommendation for the last moments of a dying person after he/her has lost consciousness, but this Sacrament instead represents the concrete occasion for Communion with the living Christ in moments of suffering and pain and at any time during old age. As it is a Sacrament with a specific destination, it can be repeated, and it can be administered before a surgical intervention, for example, or before other therapeutic treatments, during illness, and naturally while the passage of death is approaching: “In fact, the seriously ill man needs, in the state of anxiety and pain in which he finds himself, a special grace from God in order not to allow himself to be disheartened, with the danger that temptation will cause his faith to waver” (CEI 1974).

The special Grace of the Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick and its effects are the uniting of the sick person to the passion of Christ, for his/her own good and that of the whole Church; the strengthening, peace, and courage to endure the sufferings of illness or old age in a Christian manner; the forgiveness of sins if the sick person was not able to obtain it through the Sacrament of Penance; the restoration of health if it is conducive to the salvation of his/her soul; and preparation for passing over to eternal life (John Paul II 1992).

It is evident that in illness, a Christian Catholic man or woman asks God for special help that comes to them precisely through this Sacrament, the effects of which could not be more consoling. As part of palliative care, it confers the grace of the Holy Spirit onto the sick person; the ill receive help in achieving their salvation, feel refreshed by their trust in God, and gain new strength against the temptations of the evil one and the anxiety of death; the sicks can thus not only bear evil validly, but fight it and can also achieve health in cases where an advantage for their spiritual salvation derives from this Sacrament (PCHPC 2005).

The Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick is only conferred by ordained priests through the imposition of the priests’ hands on the head of the patient, the communitarian prayer of faith together with the sick (if conscious) and with the personnel/families, and the anointing of the hands and forehead with oil that has been sanctified by God’s blessing (by the Bishop on the Holy Thursday).

3.3. Empirical Data Collection

In this anthropological and theological framework, we focused our attention on the action of the Sacraments as an integral, dynamic, and enhanced part of the palliative care process in a cross-disciplinary way. We then studied the period from October 2018 to September 2021 following our ordinary work at the A. Gemelli University Polyclinic in palliative care and in the Spiritual/Religious services, with the intention of collecting the following data: the Sacraments of the Anointing that were administrated in cooperation with all the Care Team, the origin of the request, and the presence of the personnel and/or the families each time. This work represents neither an experiment nor a particular analysis, but instead represents an evaluation of an ordinary service that, to our understanding, has not been evaluated in the literature before.

In particular, the data were collected directly by the friars and priests who conferred the Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sicks in strict communion between the chaplains and the health personnel. For each Anointing, we thus decided to include evidence pertaining to the asking person (the sick, the family, the health personnel); the age of the sick person; the date; the presence or absence of the personnel during the Sacrament; and the presence or the absence of the families during the Sacrament. Finally, the collected data were analyzed by the cross-disciplinary team.

As far as eventual biases are concerned, we have to underline that the opportunity to receive the Sacraments is not at all imposed nor is it taken for granted. Those who are sick in our hospital come from different religious experiences and sensibilities, but the visit and the presence of the priests, friars, and nuns each day makes it possible for anyone is weak or vulnerable to illness to awaken a sincere reference to God. Sacraments are obviously only administered to those who request them or based on the evaluation of the care team. The latter indication can be given by the personnel, by the families, and/or by the priests/friars/nuns because of their constant presence during the time in which the patients are ill.

In this work, the spiritual perspective is thus directly referred to as a cross-disciplinary approach that is expressly enhanced with the Sacraments and their added value as connected to the Christian Catholic faith. No bias was present during the data collection both because of the interaction of the whole staff as well as for the objective concreteness of this Sacrament. Nevertheless, future studies could determine the specificity of the Sacraments themselves as acts of God during the care process and their role, as an explained proposal, for non-Christian patients expressing a desire to be baptized. At the same time, we also highlight how we ordinarily involve other spiritual assistants (for the different religions), if requested, to help all patients fulfill their own needs during their time spent in palliative care, but in this study, we only focused on the specific reference to the Sacraments.

The stage of the illness of each patient was not evaluated deliberately because integral care was considered as one entity that took place throughout the entire time spent in hospital.

Family involvement was the final aspect that was focused upon in the present study. The service of the chaplains and of the whole palliative care team is not punctual but is instead continuous. As such, we had the possibility to receive personal resonances from the families during the care period because either the chaplains or the health personnel were in communication with the families regarding Sacramental care during the palliative care process as well as when Sacraments had to be administered in the absence of the families. This provided a source of satisfaction and consolation for the families themselves, which will be described.

4. Results: Data Collection and Evaluation

While caring for the patients during different stages of their illnesses and while evaluating their therapy in palliative care, the Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick was administrated in many cases. As shown, this represents a concrete, objective, and expanded resource that is able to refer to integral care and specifically to the conditions of weakness and vulnerability that the patients were living in. On this basis, the data that were collected are significative of the interventions that took place within a framework of expanded care.

No data that are identifiable at the patient level will be transmitted, and only aggregate data will be reported.

The data that were extracted do not aim to control the effects of the Sacraments and instead emphasize the dimension of the integrated professional training that has been received by the staff and the importance of team work.

The data that have been collected refer to three complete years and cover the 36 months between October 2018 and September 2021.

The data that are reported refer to patients who were admitted to 69 wards of the A. Gemelli Polyclinic in Rome (1500 in-hospital beds) and who were administered the Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick by the hospital chaplains during the specified period.

There are six chaplains in total, all of whom live at the hospital. They are all involved in daily visits to the patients, making at least two complete visits to all the sicks each week. In particular one chaplain each day (making turns) is available 24 h for the whole hospital for emergencies

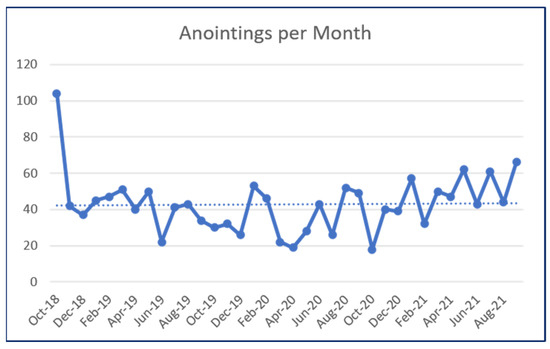

A total of 1541 Anointings were administered, with an average of 514 (approximation up) Anointings per year, with 757 being received by women and 784 being received by men.

An important finding resulting from the data analysis is the interpolation line of the Anointings during the entire period: it is quite horizontal, with a value that is very close to the average of the data. We cannot individuate a significant variation in the data during the COVID-19 period; on the other hand, the data themselves were taken during continuous service. We do think that the value of the interpolation line could be important, not in a qualitative sense, but instead to indicate that through ordinary and unpredictable variations, the data are stable and maintain a constant mean value. That is to say that the data can be used to evaluate ordinary work throughout the entire study period. The natural variations are thus not referrable to specific events (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Anointings per month.

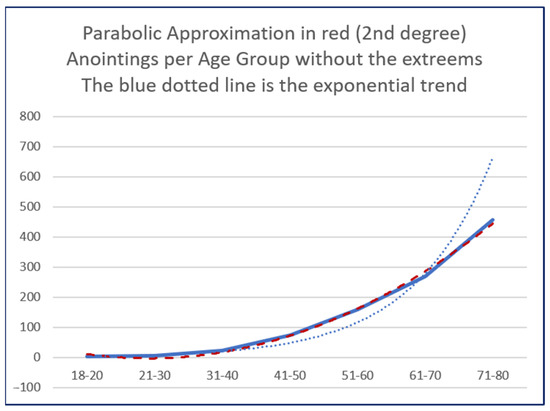

In terms of the distribution of the data by age group, excluding the extremes (0–18 and 81 upwards), a perfectly polynomial second-degree distribution (parabolic) is obtained, as seen in Figure 5, and is not as exponential as expected if the Anointings were conceived as a Sacrament that was only conferred in cases of advanced age (this is shown by the interpolation with an exponential approximation—dotted blue line—to demonstrate the clear difference in the evidence). On one hand, the linear trend is unexpected, as there would be an indistinct and constant distribution with respect to age, a result that would not take into account the greater incidence of the diseases in the older age groups. However, in theory, it would be more likely that a flatter curve would correspond with lower age groups and that there would be an exponential increase with age, which would take into account that this Sacrament is often only “asked” for the last moments of life. However, the parabolic growth is a surprise, which in fact “tears” away the idea that this is the Sacrament of consolation for a dying person (as it would be if the curve were exponential, that is, if the data were concentrated at higher ranges).

Figure 5.

Anointings per age group.

These results are very interesting to us because while it is more than natural to expect this trend to grow with age, since illness and suffering are mostly the prerogative of older people, a polynomial and parabolic approximation offers us some food for thought.

In fact, the parabolic shape adds important information that indicates a trend that expresses a gradualness in awareness and in the request.

Therefore, the first ingredient that emerges is precisely the “simplicity” of the data, in the sense that the Anointing of the Sick is a Sacrament that is considered to be an integral part of a patient’s care process. It is important to consider how much the staff who, as we have seen, is the main applicant of this Sacrament (Figure 6), are aware in order for them to guarantee a natural consideration of this Sacrament within the dynamism of care for the integral good of the patient. This datum is also confirmed by the finding that almost all the medical and nursing staff made the choice to request the celebration of the Sacrament by participating in the Sacrament with the priest next to the patient (Figure 7). The simplicity is also highlighted by the constant interpolation of the Anointings along the three-year period.

Figure 6.

Calls for anointings.

Figure 7.

Participation of the personnel during the Anointings.

“Uniformity” is the second factor that is taken into account for the whole hospital and for all age groups as well as for the specific patients’ needs.

The first-derivative gradient of this curve provides its usual information regarding the growth rate of the Anointings as it is related to different age groups. It indicates that the number of Anointings does not accelerate with age and that the personnel is able to evaluate and to propose the Sacrament of the Anointing according to specific needs, not being ‘biased’ by the age. This linearity thus adds a third element after simplicity and uniformity, which is the “familiarity” of the personnel with this Sacrament.

The sensitivity of the staff is therefore the decisive aspect that emerges from the number of nurses and doctors who call the chaplains to evaluate and recognize a need for the Sacrament in the context of the care as well as from the palliative care of the individual sick person in terms of whether it corresponds to the worsening of his/her condition or if he/her is available to receive it during the hospitalization; on the other hand, familiarity also emerges as the product of the number of nurses and doctors who, after calling for the chaplains, choose to be present during the celebration of the Sacrament as well as the other individuals who the specific doctor or nurse calls to participate with them.

Familiarity with the Sacrament, the simplicity of the statistic, and the uniformity of the applications are therefore the terms that express, in summary, the awareness of the staff both in reference to the Christian meaning of the Sacrament and concerning the importance of the Sacrament itself for the life of the patient in the integral context of care; the sensitivity to the logic of giving and of gratuitousness, which emerges strongly from the number of calls, from participation and, most importantly, from the joy of being able to confer the Anointing on one of their patients as a gift; the overcoming of the idea of consolation or comfort in favor of a “therapeutic” action on the patient in the sense of care that is extended to the dimensions of the body and of the spirit (the soul), with the view of unity in the direction of the eternal life, going beyond the moment and beyond the actual physical care to the patient.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made this final aspect even more evident, especially since our Polyclinic has made the choice to stop all relative visits but allowing the continuous presence of chaplains (thanks to the fact that they live in the Polyclinic 24 h a day). This strong and synergic collaboration during such a delicate time has served to strengthen the awareness of the interaction between a concrete medical approach and a concrete Sacramental approach in both the spiritual and health care teams, but also, most notably, in the gratefulness expressed by the relatives of these sick patients to these care teams.

The resonances that have been expressed by the relatives concerning this attention to each individual patient, granting him/her integral health/salvation care while living in the deep and extreme sufferance that is caused by the distance and the impossibility of being in touch, have been so grateful, full of wonder, and a source of great consolation, regardless of whether explicit requests for the Sacrament have been made.

Two specific findings become clear when discussing how integral care focuses on the dignity of the person and not only on his/her conscious comfort: the first thing that becomes clear is the consolation of the families, who were able to take comfort in the fact that their sick relatives were granted warm and complete attention by both the Medical Personnel and by the chaplains; the second thing that became evident was the demolition of the wall relating to the lack of faith of the people involved in favor of the salvation of their sick relative. Suffering discloses in fact the interior and original need for God and for Salvation that is also present in those who are not believers.

This indicates that letting the families know that their sick relatives were reached also by the Sacraments as the deepest possible “prayer” and action, was, despite their personal consciousness in the Catholic faith, provided both a great source of peace and a concrete opportunity creating a new awareness of faith.

A final aspect that is worth highlighting is related to the impact that the widespread participation of health personnel in the celebration of the Sacrament of the Anointing has on dealing with compassion fatigue, a phenomenon to which the personnel itself is subjected. This participation offers the concrete, effective, and pacifying possibility of handing one’s emotional involvement and one’s efforts (personal and of the team) into the concrete hands of God (through community sacramental action) for the benefit of the gift of full and eternal life to the sick. Delivering one’s fatigue is only possible where there is a reasonably consistent bridge between the human and the divine, which is represented precisely by the Sacraments and by a Personal and Revealed God who theologically guarantees its truth. Compassion fatigue would otherwise remain entirely the responsibility of the personal elaboration of those who care for the ill.

5. Discussion

Two main aspects that we would like to address while discussing our results refer to how the health community operates as well as to the effectiveness of the integral approach to palliative care that is used at the A. Gemelli University Policlinic.

5.1. An Enhanced Health Community

The close collaboration of the entire health community with the work of the hospitaller chaplaincy is made up of a community of Franciscan minor friars who are at the direct service of the ill, a community of diocesan priests at the service of the health personnel and of the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, and a community of nuns, who carry out nursing and health services.

In this way, spirituality is integrated with the Catholic faith, which confers an integral perspective to the Human Person, and the health community reaches the sick without any exclusion and with great respect for diversities. The surplus is both on the level of the experience of faith and on the possibility of administering the Sacraments.

Such a health community carries out its work in a synergy that has been consolidated over the years and that allows operational dynamism and spiritual support from the perspective, as we have seen, not only of an “interior” accompaniment but one that also considers the care of the person in terms of both corporeal and spiritual dignity.

This anthropological approach does not have its basis in a theological addition to the principles that human reason may already be able to elaborate, nor in a rational discourse that is reinforced by evidence of man’s dignity or in one possible transcendent sense. The specificity that we want to highlight is instead anchored on the Revelations that God makes of himself so that, as a gift, man enters a sanctuary (life) not built by man’s hands (Mantini 2014).

Specifically, the close cross-disciplinary collaboration that is made up of presence, competence, action and prayer, communion, and intercession, along the wards, in the offices, in the operating rooms, in the emergency rooms, in the clinics, along the corridors of the waiting rooms, etc., is consolidated and made effective by the most precious and decisive gift of the Sacraments.

It is therefore not a question of consolatory support and philanthropic proximity, which would however represent an important step, but is instead a question of the importance of “taking care” of all of the dimensions of a person.

This makes salvific bidirectional compassion a spiritual practice, a way of being and a way of being in service that is both close to and without hierarchies.

The value of human proximity is immense, especially in moments of pain and suffering, but the value of the proximity of the Crucified and Risen Christ himself, which is present through the hands of his priests, is absolutely a great novelty. In the full freedom of each person, of his cultural context, and of his religious sensitivity, the health personnel and the chaplaincy structure a network of healing relationships that can offer everyone the broadest and most concrete horizon to face the challenges that are imparted by suffering and pain. Patients must be placed in a position in which they are able “to satisfy their moral and family obligations and above all they must be able to prepare themselves with full conscience for the definitive encounter with God” as much as possible (PCHPC 2005).

This network of healing relationships is a dynamic structure in which the patient is inserted and that surrounds him with discretion, offering proximity at all professional, human, and spiritual levels. Since this network is aware of being inserted into the Trinitarian relationality and drawing from it, an attempt is made to favor, with deeds and words, the passage of Grace through imprinting the logic of the Incarnation. In this way, the dynamism of the network does not support every patient with a standard approach but instead reaches him/her by welcoming the clinical, personal, family, historical, social, spiritual specificity. On the other hand, the excess of the network primarily consists of its placement in a context that is not only of unanimous prayer but that also includes each individual person in the Eucharistic dynamism of the daily Celebration of the Holy Mass, which is experienced within the hospital, while the same patients participate in the network, especially those who, despite being scattered throughout the wards, express their union with the Passion of Christ, offering their suffering and their prayers for others.

This precious service is therefore offered and recommended while all members of this health community are working together.

It is evident that this approach offers a specific and concrete surplus to the contribution of the health community in order to integrally take care of the patients. It also represents a surplus in the panorama of the recent publications concerning palliative care and spiritual assistance.

5.2. The Integral Approach

We thus wish to stress the difference between what we have called an integral approach and what is usually defined as a whole approach. The latter case refers to the typical and diffuse religious assistance which consists of the presence of a chaplain or of a spiritual assistant who is helping the patient to approach, in a human and spiritual way, his/her suffering. As we all know, this proximity is incredibly important. It in fact consists of reaching the whole person (body and soul) and his/her relations in order to comfort the sick on the horizontal level, that is during terrestrial life, and on the vertical plane, which consists of the religious and/or spiritual personal dispositions or beliefs. The former, which concerns the integral approach, instead refers to the importance of the wider reality of the Dignity of the Person and goes beyond the physical or spiritual aspects. It, in fact, adds a third dimension, conferring the naturally desired Eternal Dimension that is finally revealed as consistent (Table 1):

Table 1.

Spiritual and integral assistance.

In the context of palliative care, where the contributions of spiritual assistance are important, it is also necessary to consider instances where a disease has affected a patient’s consciousness. This delicate time of the life, which can be brief or long, is an important part of the whole palliative care process, and during this time, spiritual assistance is essential and it is particularly important the Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick.

Since it is not a measurable quality, it is difficult to determine when spiritual assistance has been achieved because it depends on many personal, historical, and relational dimensions. For this reason, we do need a parameter that can define the effectiveness of complete assistance, and this can be precisely represented by Sacraments that include both divine and human action, as seen here.

As such, the Sacraments are not substitutive to spiritual assistance but instead confer a completeness to it “while the Lord worked with them and confirmed the word through accompanying signs” (Mk 16: 20).

In palliative care, the contribution of the Sacraments integrates the process and permits all of the dimensions of a patient’s life to be reached, when cases where the patient is not in a state of consciousness, a time in which spiritual assistance has no instruments (except for the proximity and prayer, that, in turn, are always essential), resulting in collaboration between divine and human action.

The real dimensionality of human life that springs from the revelations of God in Christ therefore offers tools and methods that must be integrated with each other in a synergy that not only crosses and connects the disciplines but that strengthens them from within, offering the “hands” of healthcare personnel that “extra” knowledge about care and heart that St. Camillus de Lellis strongly wished for when he said “more heart in those hands”. This “more” is not simply supported by the good will of man, which can be weak and fragile, even in serving, but it is instead a given “more” that therefore widens the narrow and limited dimensions of human action, making it more human with the gift of the Grace united with the freedom of man who receives it.

6. Conclusions

The integral approach to the human person that is proposed in this paper offers an additional and qualifying passage with respect to the more widespread and important attention to the spiritual or religious dimension that is applied also to palliative care. At the basis of this proposal, there is full cross-disciplinarity that goes beyond the inter- or multi-disciplinary model, allowing for profound interaction between the disciplines and the treatment strategies that are involved (medical/health/scientific aspects, welfare aspect and theological aspect) and the full training of all personnel who are considered to be a part of the real health community.

We have proposed the passage from the care to the “whole” person, which considers one’s earthly existence in the awareness and in the moment at which a person is no longer conscious, to the surplus that is offered by the “integral” care to a person, which consider life to not only include one’s time on earth but also to extend it to the salvation and the fullness of life that follows after death. Access to this improved dimension, which is highly desirable for each of us, is made possible thanks to the conscious integration, in the Catholic perspective, of the Sacraments and, in particular, the Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick, within the complex and precious process of care and of palliative care for the patient in the various stages of disease, including in times of agony.

At the A. Gemelli University Polyclinic in Rome, the staff have received a level of training that allows them to have a medium and generalized awareness of the importance concerning this aspect of integral care in close collaboration with the entire care team, including with the chaplains who live in the hospital permanently, reaching a level of dynamic coordination that leads next to the sick and consequently to their families. The precious involvement of the health personnel, which is manifested both in the attention to calling the chaplains at times of need and in actively participating in the individual, intensive, emergency or operating rooms during the celebration of the Sacrament, highlights an integral system of care.

The proposed sampling of the data that were collected over three years of investigation shows us on the one hand, the simplicity and uniformity of the data that were related to the administered Anointings, which consequently mean full, natural, and constant involvement and awareness of the care community, and on the other hand, represents a widespread familiarity with the Sacrament itself. In fact, that parabolic trends that were observed with the different age groups indicates that progressively and according to the greater or lesser needs of the sick, the Anointing Sacrament is administered as a decisive part of the treatment process that is extended and enhanced to the integral dignity of the Person.

We then highlighted at least two important results: the first relates to the preparation, participation, and, above all, the interaction of the health personnel who are responsible for complete and extensive palliative care; the second is related to the transition to the integral care of the Person, which takes into account the action of man and the action of God’s Grace through the gift of the Sacraments, whose consolation and efficacy fully reaches the sick and, similar to a luminous reflection, the peace and satisfaction of family members.

The results that were proposed here aim to integrate but also introduce a process of care in the context of palliative care and beyond, in which the Sacraments and, in particular, the Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick can represent a surplus that remains unexplored.

Further research could be certainly developed, and this paper is intended to be a starting point that is aimed at contextualizing the Sacramental approach to care and palliative care and to generally motivate this area, to evaluate its importance, and to propose a first empirical analysis as a basis for new studies.

According to the approach that was proposed here, the natural and precious asymmetry between vulnerable and needy patients and the care team is recognized; however, the style of the care relationship overcomes paternalism in favor of shared care planning.

All this is possible within a dynamic relationship between the patient, the family, and all of the members of the palliative care team, who are called to bend over the vulnerability and weakness of the sick person, enriched with the gift of God and who are therefore fortified humanly and professionally.

In this way, health care personnel and spiritual assistants may be better able to serve the hospital as a Sanctuary of Hope.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and M.A.R.; methodology, A.M.; validation, all authors; formal analysis, all authors; investigation, all authors; resources, all authors; data curation, A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.; writing—review and editing, A.M.; visualization, A.M.; supervision, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all the health personnel of the hospital and all of the chaplains, minor friars, priests, and nuns who dedicate their lives to caring for the sick patients at this polyclinic and at this university, which is celebrating its 100-year anniversary (1921–2021) of its founding by A. Gemelli.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abiven, Maurice. 1995. Une éthique pour la mort. Paris: Desclée de Brouwer. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins, Kim. 2008. Narrative Identity and Moral Identity. A Practical Perspective. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Benanti, Paolo. 2016. Ut si homo non daretur? Un tentativo di dialogo con il post-umano a partire da alcuni spunti della Gaudium et spes. Gregorianum 97: 543–64, (Our Translation). [Google Scholar]

- Benedict XVI. 2005. Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/archive/compendium_ccc/documents/archive_2005_compendium-ccc_en.html (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Best, Megan, Carlo Leget, Andrew Goodhead, and Piret Paal. 2020. An EAPC white paper on multi-disciplinary education for spiritual care in palliative care. BMC Palliative Care 19: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CEI. 1974. Sacramento dell’Unzione e cura pastorale degli infermi. Roma: Edizioni Conferenza Episcopoale Italiana. [Google Scholar]

- Chitra, G., Paul Victor, and Judith V. Treschuk. 2020. Critical Literature Review on the Definition Clarity of the Concept of Faith, Religion, and Spirituality. Journal of Holistic Nursing 38: 107–13. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, David. 1999. ‘Total pain’, disciplinary power and the body in the work of Cicely Saunders, 1958–1967. Social Science & Medicine 49: 727–36. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, David. 2005. Foreword. In Watch with Me: Inspiration for a Life in Hospice Care. Edited by Saunders Cicely. Lancaster: Observatory Publications, pp. vii–xii. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, Lisa A. 2019. Compassion Fatigue in Palliative Care Nursing: A Concept Analysis. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing 21: 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, Jonas Preposi, Nahed Alquwez, Jennifer H. Mesde, Ahmed Mohammed Aid Almoghairi, Abdulaziz Ibrahim Altukhays, and Paolo C. Colet. 2020. Spiritual climate in hospitals influences nurses’ professional quality of life. Journal of Nursing Management 28: 1589–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrel, Betty. R., George Handzo, Tina Picchi, Christina Puchalski, and William E. Rosa. 2020. The Urgency of Spiritual Care: COVID-19 and the Critical Need for Whole Person Palliation. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 60: e7–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis. 2015. Laudato si’. Encyclical Letter. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclica-laudato-si.html (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Gijsberts, Marie-José H. E., Anke. I. Liefbroer, René Otten, and Erik Olsman. 2019. Spiritual Care in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review of the Recent European Literature. Medical Science 7: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- John, Paul, II. 1992. Catechism of the Catholic Church. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/_INDEX.HTM (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Koenig, Harnold G. 2012. Religion, spirituality, and health: The research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry 16: 278730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lucas Lucas, Ramón. 2007. L’uomo, spirito incarnato. Compendio di filosofia dell’uomo. Cinisello Balsamo: Edizioni San Paolo, (Our Translation). [Google Scholar]

- Mantini, Alessandro. 2014. Introduzione. In Anima e Corpo. Una sfida per la Cura: Itinerario formativo per la cura dei malati. Edited by Mantini Alessandro and Cappellani Ospedale. Santa Maria degli Angeli: Edizioni Porziuncola, pp. 5–18, (Our Translation). [Google Scholar]

- Miccinesi, Guido, Augusto Caraceni, Ferdinando Garetto, Giovanni Zaninetta, Raffaella Bertè, Chiara M. Broglia, Bruno Farci, P. Lora Aprile, Massimo Luzzani, Annamaria M. Marzi, and et al. 2020. The Path of Cicely Saunders: The ‘Peculiar Beauty’ of Palliative Care. Journal of Palliative Care 35: 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontifical Council for Health Pastoral Care (PCHPC). 2005. Dolentium Hominum. p. 58. Available online: https://www.humandevelopment.va/content/dam/sviluppoumano/pubblicazioni-documenti/archivio/salute/dolentium-hominum-en-1-72/DH_58_En.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Puchalsky, M. Christina, Betty Ferrell, Rose Virani, Shirley Otis-Green, Pamela Baird, Janet Bull, Harvey Chochinov, George Handzo, Holly Nelson-Becker, Maryjo Prince-Paul, and et al. 2009. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: The report of the Consensus Conference. Journal of Palliative Medicine 12: 885–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Puchalsky, M. Christina, Robert Vitillo, Sharon K. Hull, and Nancy Reller. 2014. Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: Reaching national and international consensus. Journal of Palliative Medicine 17: 642–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radbruch, Lukas, Liliana De Lima, Felicia Knaul, Roberto Wenk, Zipporah Ali, Sushma Bhatnaghar, Charmaine Blanchard, Eduardo Bruera, Rosa Buitrago, Claudia Burla, and et al. 2020. Redefining Palliative Care—A New Consensus-Based Definition. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 60: 754–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, Cicely. 2005. Watch With Me: Inspiration For a Life In Hospice Care. Lancaster: Observatory Publications, pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Selman, Lucy Ellen, Lisa Jane Brighton, Shane Sinclair, Ikali Karvinen, Richard Egan, Peter Speck, Richard A. Powell, Ewa Deskur-Smielecka, Myra Glajchen, Shelly Adler, and et al. 2018. Patients’ and caregivers’ needs, experiences, preferences and research priorities in spiritual care: A focus group study across nine countries. Palliative Medicine 32: 216–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sepúlveda, Cecilia, Amanda Marlin, Tokuo Yoshida, and Andreas Ullrich. 2002. Palliative care: The World Health Organization’s global perspective. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 24: 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhauser, Karen E., George Fitchett, George F Handzo, Kimberly S. Johnson, Harold G. Koenig, Kenneth I. Pargament, Christina M. Puchalski, Shane Sinclair, Elizabeth J. Taylor, and Tracy A. Balboni. 2017. State of the Science of Spirituality and Palliative Care Research Part I: Definitions, Measurement, and Outcomes. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 54: 428–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vatican Council II. 1965. Gaudium et Spes. Pastoral Constitution. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19651207_gaudium-et-spes_en.html (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Viola, Vittorio. 2014. I Sacramenti farmaco e cura. In Anima e Corpo. Una sfida per la Cura: Itinerario formativo per la cura dei malati. Edited by Mantini Alessandro and Cappellani Ospedale. Santa Maria degli Angeli: Edizioni Porziuncola, pp. 307–24, (Our Translation). [Google Scholar]

- Visser, Cora, Johannes C. F. KEt, Gerda Croiset, and Rashmi A. Kusurkar. 2017. Perceptions of residents, medical and nursing students about interprofessional education: A systematic review of the quantitative and qualitative literature. BMC Medical Education 17: 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuccaro, Cataldo. 2015. Fundamental Moral Theology. Vatican City: Urbaniana University Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).