Abstract

Based on several scientific publications, a limited number of news from the 1980s up until 2021 and a series of in-depth interviews with devotees in 2006–2021, the authors of the paper managed to restore the history of Bengal Vaishnavism distribution in Belarus for the first time. Specific attributes of its introduction to the country were: (1) philosophical requests from the local citizens, not immigration of its original bearers; (2) a long period of spontaneous distribution in the form of personal involvement with Vaishnava ideas and, hence, late institutionalization of the movement. The main stages of Vaishnavism development in Belarus were distinguished: (1) 1980s, the Soviet period: introduction of Vaishnava ideas and practices within individual self-identification of the members of small groups; (2) 1990s, the post-Soviet period: forming organizational structure of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) in Belarus; (3) 2000s: spiritual and administrative crises and reformation of the systems of administration and practice creation of the institute of curating the newly converted devotees; (4) 2010s: search for and establishment of the new models of serving, the out-of-temple bhakti practice, in particular; further popularization of the Vaishnava movement and community in Belarus. The main source of information on the history of Vaishnavism distribution in Belarus were in-depth interviews with the members of the community standing at its origin.

1. Introduction

There is a gap in the current academic tradition of the ISKCON research covering its presence in the Eastern Europe (De Backer 2020). This article presents a study showing the historical stages of the ISKCON communities’ distribution across the post-Soviet Belarus and their distinctive features. Religious communities, especially the non-traditional ones, were nearly prohibited in the Soviet times. The development of the ISKCON community in Belarus is a small chapter in the history of the ISKCON distribution in Eastern Europe, yet it can serve as the basis for a broader elaboration on the topic and be characteristic for the region, reflecting typical key attributes of the ISKCON distribution in the post-Soviet countries. Determination of these features provides the answer to the key research question: how did ISKCON manage to survive and maintain steady development on the post-Soviet territory until the present day with no suitable conditions, favorable legislation, or Hindu diaspora?

2. Sources and Methodology of Research

A study was conducted, studying the becoming of the Vaishnava community in Belarus. It resulted in the narrative of events constituting its history, which has been recreated for the first time. The sources for its restoration were popular and academic editions, news publications, as well as series (2006–2007, 2016–2017, and 2020–2021) of in-depth interviews with the devotees at the origin of the community in Belarus:

- (1)

- An autobiographical book Hare Krishna Yesterday and Today by M. N. Shilov (one of the first Vaishnava followers in the territory of the USSR), half of which, about 200 pages, describes his preaching in Belarus (Mohan Das 2010);

- (2)

- Academic editions: works by A. I. Gurko containing the results of an ethnographic research of ISKCON lifestyle, teaching, and organizational form in Belarus: (a) dissertation ‘Vaishnavism and its Features in Belarus’ (Gurko 1993) and (b) monograph ‘Vaishnav Movement (Hare Krishna) and its Followers in Belarus’ (Gurko 1999) article by S. M. Zaiko ‘Hare Krishna Followers in Belarus’ (Zaiko 1997) about the Krishna Consciousness movement in the Hrodna region; the article by A. A. Titovets ‘International Society for Krishna Consciousness’ (Titovets 2000) is characterized by a pronounced anti-cult position;

- (3)

- News publications in printed newspapers and magazines from 1987 to 2007, Internet publications of the late 2000s–2010s;

- (4)

- A popular article by I. Lirb (Lirb 1996) is devoted to the festival held in Minsk, marking the 100th anniversary of the ISKCON founder.

Each of the above publications describe a certain aspect of the distribution of the Vaishnava communities in Belarus since the late 1980s. The first and the second on the list, the autobiography of ex-devotee M. N. Shilov and the scientific monograph of the Belarusian ethnographer A. I. Gurko, are the richest ones. Shilov’s book provides a detailed understanding of the becoming of Vaishnavism in Belarus. However, that information is intertwined with the author’s personal story, which only makes it useful for an academic scholar as empirical material. Gurko’s scientific monograph is the first systematic research of Vaishnavism in Belarus and the characteristics of the way of life of its early communities. This research is a good basis for elaborating on Vaishnavism in Belarus. The present article continues the research disclosing ISKCON in Belarus from within, based on the devotees’ memories and dividing its history into qualitatively different stages.

- (1)

- Empirical grounds for the research were a number of in-depth interviews with the Vaishnava tradition followers in Belarus.

One of the series was conducted from January to June 2021 specifically in preparation of this paper with 13 respondents. Selection criteria included, first, their administrative status in the community (see Appendix A) and second, their authority among the followers (these characteristics coincided in all cases). The age of the respondents was between 45 and 50 years. Considering the respondents’ status in the community, their interviews can be deemed expert ones, as they contain direct evidence of the events constituting the history of Vaishnavism in Belarus. The goals of this series were to discover (1) the respondent’s motivation for spiritual search and their conversion to Vaishnavism; (2) circumstances of their first encounter with the devotees and understanding of the need to accept the spiritual teacher; as well as (3) a description of the events affecting the distribution of ISKCON in Belarus.

Along with the 2021 series, interviews of the devotees were used and conducted (1) by one of the authors, I. Tarkan, in 2017–2018, in order to study the Hindu manifestations in Belarus (Karassyova and Tarkan 2020, 2 interviews) and (2) by one of the devotees in 2016–2017 in order to compile the ISKCON timeline (4 interviews).

Finally, in the course of the research, it was discovered that the ISKCON community possessed a series of interviews conducted by one of the devotees in 2006–2007 to reconstruct the history of the community (14 interviews). Those interviews were provided to the authors of this research and were used together with the other ones to interpret the results.

It should be noted that among 3395 religious communities under state registration in the Republic of Belarus as of 1 January 2021, there are only 6 Vaishnava communities. They operate in all the administrative regions of the country, except for one (Minsk region), and in the capital city of Minsk. The number of initiated followers is almost 250; the steady number of people interested in Vaishnava culture and joining community events has been around 1000 in the past few years. There is no other data on the size of the Vaishnava community. Questionnaires of the quantitative researches, which are extremely rare, place Vaishnavism in the ‘other’ category and due to the small number of followers it remains invisible in the national sample. So, in terms of the scale of request, Vaishnavism remains an exotic, rare tradition in Belarus. However, in terms of stability of presence and cultural influence, it has become common (Karassyova and Tarkan 2020).

3. Overview of Historical Stages of ISKCON Becoming in Belarus

Based on the contemporary studies four stages of the ISKCON development in the West can be distinguished.

- (1)

- Late 1960s–early 1970s: A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami’s visit to the USA and establishment of ISKCON. Active preaching and distribution of the Hare Krishna movement in the USA and across the Western Europe are typical for this stage. (Shinn 2005);

- (2)

- 1980s–1990s: A crisis manifested as retirement of many spiritual leaders, cases of violence against the gurukula students and infringement of the rights of women living in the Hare Krishna communities. (Vishnu Swami 2004; Wolf 2004; Knott 2004);

- (3)

- 2000s: Reforms aimed at establishing public relations and restoration of the devotees’ reputation (Deadwyler 2004). One of the prominent trends of the time was Hinduisation of the ISKCON communities due to active cooperation of its leaders with the Hindu diasporas. (Rochford 2007);

- (4)

- 2010s: Post-reform development characterized by distribution of the ISKCON as a Hindu religion and prevailing temple piety practices. (Wilke 2020).

Materials of the interviews allow the conclusion on formal similarity of the ISKCON development in Belarus and that in the West. Yet at the same time, a number of specific features make the Belarusian ISKCON qualitatively different.

Thus, almost 20 years (1970s–1980s) of the Hare Krishna movement development in the Soviet Union were without any institutional support, such as ISKCON. It was the spontaneous missionary activity of initiated individuals whose preaching was welcome by the intellectuals in search. It was only in the early 1990s that the ISKCON was registered.

The lack of Hindu diasporas in Belarus and harsh legislation against religious organizations made it impossible to rely on external resources during the 2000s ISKCON crisis. As a result, the main resource for the Vaishnava community in Belarus was in the informal groups of spiritual communication which were forming at the time and preserved the spiritual experience.

The post-reform history of the Belarusian ISKCON in the 2010s was characterized by a search of out-of-temple forms of piety and preaching due to significant hurdles for the ISKCON as a Hindu religion posed by the state policy in the form of religious preference favoring religions traditional for Belarus.

The above-mentioned provisions on spontaneous development, reliance on internal resources alone and the out-of-temple forms of preaching will be further described as distinctive attributes of the ISKCON in Belarus within the relevant historical stages of the Hare Krishna development in Belarus.

1980s: ISKCON Regional Secretary for Belarus Yuga avatāra dāsa noted that M. N. Shilov played an important role in the introduction and distribution of the Krishna Consciousness movement in Belarus (interview: 3. Yuga avatāra dāsa, 2021). He was from the first generation of the Soviet Vaishnava followers initiated by the International Society of Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) gurus in the late 1970s–early 1980s. According to M. N. Shilov’s own memories, he first learned about the Krishna Consciousness movement in 1980. That same year, he was initiated by Robert Campagnola (Harikesha Swami) and received the spiritual name Mamu Thakur Das (Mohan Maharaj 2016). In the 1980s, M. N. Shilov was preaching actively travelling to all the Soviet Union republics including Belarus.

In his autobiography ‘Hare Krishna Yesterday and Today’, M. N. Shilov noted that he visited Belarus for the first time in 1982. He met the representatives of the Belarusian intellectual class in Minsk, Lida, and Kobryn, and held spiritual and enlightening programs at private apartments. These resulted in popularization of the Krishna Consciousness movement among the intellectuals and an inflow of new followers (Mohan Das 2010).

It should be noted that since the ISKCON founder A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami’s visit to Moscow in 1971 until 1982, Vaishnavism developed in the Soviet Union in the underground setting, yet without any persecution. Vaishnava communities emerged at that time based on yoga classes and health groups, and preaching groups formed, among which the best organized were the ones in Moscow and the Baltic cities of Riga, Tallinn, and Kaunas (Ivanenko 2008). After 1982, the development of Vaishnavism has faced persecution by the State Security Committee (KGB) and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). The peak of mass persecution was in 1984 to 1986 (Shturman 1986).

It was the time of raids on the apartments of the free-thinking Belarusians, the first followers of the Krishna Consciousness movement among them. An article was printed in the Sovetskaya Belorussia (Soviet Belorussia) newspaper, the main official newspaper of the republic, about the harm of vegetarianism and danger from the Krishna Consciousness movement (Gurinovich 1987). According to M. N. Shilov, the article was based on the words of one of the first followers of the Krishna Consciousness movement who testified under pressure from the authorities (Mohan Das 2010). M. N. Shilov himself was arrested in 1985 and he did not visit Belarus until 1989.

Change in the ideological situation during the perestroika—democratic state reforms in the second half of the 1980s—created favorable conditions for starting practice and the restoration of missionary activities by the Vaishnava tradition followers in the Soviet Union. By 1989, when M. N. Shilov arrived in Belarus after a four-year break, a vegetarian café was already operating in Minsk. The café was opened by one of the yoga class leaders in the House of Culture at the Minsk Industrial Association named after V. I. Lenin (now Amkodor-Belvar OJSC). Since the café was unprofitable, its administration appealed to M. N. Shilov who has had experience of successfully organizing a vegetarian café in Leningrad (now Saint-Petersburg). M. N. Shilov invited his acquainted M. A. Gurchinsky and several other people to assist in establishing the café in Minsk.

Due to a conflict with the plant administration who accused the café administration of religious preaching the latter were forced to leave the premises (Kosterova 1989). As M. N. Shilov recalled, in summer 1989, the dormitory of the Minsk Institute of Culture (now Belarusian State University of Culture and Arts) became the new location of the café which was named Sankirtana. In the late 1980s to early 1990s, it became the center for spreading the Krishna Consciousness movement in Belarus. The Sankirtana-vedomosti (Sankirtana gazette) magazine was issued on the basis of the café, there was public Hare Krishna mantra singing (harinama), the Krishna’s Cuisine cookbook was published, and an exhibition showcasing the works by the Vaishnava artists and items of cult worshiping was held at the Palace of Arts (Republican Art Gallery of the Belarusian Union of Artists).

As a center of active missionary activities, the café not only attracted curious people interested in the exotic oriental atmosphere of the place, but also those who tried to adopt the Gaudiya Vaishnavism tradition at the level of deep, life-purpose requests.

When visitors appeared expressing their desire to be involved in the Vaishnava tradition on a greater scale, the café administration had to search for a place where the first followers of the Krishna Consciousness movement could live and conduct spiritual practice. An apartment rented by M. N. Shilov and M. A. Gurchinsky in one of the Minsk city districts became such a place. Dāmodara Paṇḍita dāsa, who joined the Krishna Consciousness movement in the summer 1989, recalls that life in the apartment was organized according to the principles of the preaching ashram. In the morning, there was a program including worshiping deities and that were accompanied by Hare Krishna mantra (kirtana) singing, beads mantra singing and a spiritual lecture. During the day, the Vaishnava followers distributed books in the city streets and held kirtanas in the city parks. After returning to the apartment, there was an evening program. Later, the ashram group split into the men’s and women’s ones each of which rented a separate apartment (interview: 13. Dāmodara Paṇḍita dāsa).

Further growth of the number of Krishna Consciousness followers resulted in the purchase of a private residential house in 11 Pavlova St. in 1990. It was refurbished as a new ashram with two kitchens, an expanded room for an altar to worship the deities, added floors for permanent residence of men and women, and a designated room to receive honorable guests. This place soon became the center of attraction for all the people interested in the Hindu tradition and the spread of Gaudiya Vaishnavism in Belarus. The place still exists with this status today.

1990s. The next stage of Vaishnavism development in Belarus was connected with its institutionalization.

After the Iron Curtain fell in the late 1980s, the ISKCON Governing Body Commission officially included the Soviet Union in its preaching area and sent its permanent authorized representative there to whom all the organizing secretaries of the regional communities of the Soviet Union reported. Presidents of the local communities were in turn subordinate to the secretaries. Spontaneously formed Vaishnava communities were gradually becoming parts of a centralized structure with vertical administration.

As Gokulānanda dāsa, Head of the Temple Commission of the ISKCON community in Minsk, recalled, due to the USSR dissolution, the All-Union ISKCON Center organized a meeting in December 1991 in Minsk with participation of the Vaishnava followers from the Baltic states, Ukraine, and Russia. The main issue was reorganization of preaching regions due to the Soviet republics leaving the USSR. Belarus and Ukraine were merged into one region where Neal Byers (Nirandjana Swami) represented the Governing Body Commission. M. A. Gurchinsky, who by that time had received his spiritual name Maitreya Das, was elected president of the community in Minsk (interview: 14. Gokulānanda dāsa).

Several weeks after the dissolution of the USSR, on 13 January 1992, the ISKCON community in Minsk received its certificate of state registration. In 1990s, communities in all regional centers of Belarus—Viciebsk, Homiel, Brest, Hrodna and Mahilioŭ—obtained certificates of state registration as well. A total of six registered ISKCON communities operated in Belarus in the 1990s.

An important milestone in the history of Belarusian ISKCON was the purchase in 1991 of 123 hectares of land in Hatynka village 140 km North-West from Minsk. Dāmodara Paṇḍita dāsa recalls that the head of the Minsk community M. A. Gurchinsky had for a long time been looking for the opportunity to purchase land to start a farm (interview: 13. Dāmodara Paṇḍita dāsa). After negotiations with the officials in the Ministry of Agriculture, administration of Krupki District Executive Committee, a plot of land was assigned free of charge (Malakhovskaya 1992). Soon after that, several cows and bulls were purchased and the construction of cow houses and other farming complexes started. During the 1990s, a significant share of money received as donations from book distribution and preaching programs was directed to the development of the farming infrastructure.

An iconic event contributing to the rooting of Vaishnava traditions in Belarus was the installation of the preaching center of the Minsk community of Sri Sri Gaura Nitai deity statues (murti), which M. A. Gurchinsky brought from India in 1993. According to the Vaishnava tradition, the Gaura Nitai deity form is considered a material embodiment of Krishna and is worshipped by the believers as an absolutely transcendent. Performing the rite of installations of the deities according to the Hindu standards was of great symbolic meaning to the Vaishnava followers in Belarus.

One of the events that gained the attention of the Belarusian society to the ISKCON was a lawsuit in 1993, initiated by the parents of the teenagers living at the ISKCON community ashram in Minsk. The plaintiffs accused the ISKCON of “ideological and spiritual aggression inspired by certain powers of the West” (Dergach 1993). M. A. Gurchinsky noted that the Court threatened to revoke the community’s registration and open a criminal case against the administration. Timothy Kiernan (Shaunaka Rishi Das; founder of Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies) was invited to Minsk to consult on the case. A turning point was the engagement of the leading Belarusian psychiatrists and sociologists as independent experts on the case.

The experts were A. R. Evsegneev, M. D., Associate Professor at the Department of Psychiatry of Minsk Medical Institute at the time, and E. M. Babosov, PhD, correspondent member of the Academy of Sciences of Belarus. They gave a positive assessment of the activities of Krishna Consciousness movement and highlighted that participation in the life of the Society of Krishna Consciousness does not necessarily deteriorate physical and mental state of its members and is good for the society.

The court also had financial activities of the community in Minsk audited but did not find any violations of tax legislation. Dietary study of the Krishna followers’ daily diet, which the plaintiff called “harmful”, resulted in a conclusion that the lactovegetarian food of the Belarusian followers of Krishna Consciousness was absolutely balanced and healthy.

The court proceedings were eventually closed in 1993 in favor of the defendant, ISKCON community in Minsk.

In the late 1990s, events that took place in the Belarusian ISKCON determined the next stage of the community’s development. One of them was the replacement of the leader of the ISKCON community in Minsk M. A. Gurchinsky who had been in position for about eight years and was suspended in 1997. The absolute majority of respondents gave positive feedback about M. A. Gurchinsky’s activities throughout that time. They noted his great influence on the becoming and development of both the community in Minsk and other communities in Belarus: a great amount of spiritual literature was distributed, large-scale preaching programs were conducted with participation of spiritual teachers taught by A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, a farm was established and, finally, Vaishnava communities were registered in all the regional cities in Belarus.

It was a great shock for all the followers of the Krishna Consciousness movement in the post-Soviet countries when R. Campagniola—Harikeshi Swami—left the ISKCON in 1998. D. P. Maevsky, who had been Harikeshi Swami’s apprentice at the time, recalled that he had preached in the USSR since 1976 after receiving instructions from A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami to publish and distribute Vaishnava literature in the communist countries. Being an absolute Gaudiya Vaishnavism spiritual leader in the post-Soviet countries, he initiated hundreds of apprentices. His retirement from practice and leaving the ISKCON caused a universal crisis of belief in the Vaishnava environment. Many devotees stopped their spiritual practice, many left the ISKCON for Gaudiya Math, Gaudiya Vaishnavism organizations related to the ISKCON. Harikeshi Swami’s apprentices that stayed with the ISKCON received re-initiation from other spiritual teachers.

Yuga avatāra dāsa recalled that the reaction to Harikeshi Swami’s retirement from spiritual practice and missionary activities was in structural reforms initiated by the ISKCON Governing Body Commission (interview: 3. Yuga avatāra dāsa). The root cause of the problem was that many spiritual teachers in the 1990s were worshiped by their followers as cult persons. The tradition began in the 1980s, in the areal acharya institute, when charismatic gurus preached in the ISKCON, each followed by thousands of apprentices ready to fulfill, often noncritically, the boldest and biggest preaching projects of their spiritual leaders. Although the Governing Body Commission terminated the areal acharya institute in 1988, many spiritual leaders in the 1990s continued to have a huge authority among their followers. Disputable questions often led to numerous conflicts among the apprentices of a certain guru on one side and the ISKCON administrative representatives—presidents, community chairmen, and regional secretaries—on the other side. The last word in such a situation was usually the word of the spiritual leaders. In the worst case, when a certain guru retired from spiritual practice and preaching—eight influential gurus had retired before Harikeshi Swami did—all his apprentices followed him, and the ISKCON was shocked by another crisis of belief, which would take years to overcome.

2000s: In the early 2000s, the Governing Body Commission started reforms due to the above reason. These reforms’ ideological grounds were to restore A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada’s authority as acharya and the founder of the ISKCON. Practically it meant that the teachings of Shrila Prabhupada were acknowledged to be of utmost importance compared to the teachings of other ISKCON gurus. At the same time the Governing Body Commission was recognized as a body created by Shrila Prabhupada and representing his will upon retirement. All resolutions of the Governing Body Commission should be made collectively (with common consensus) and the guru’s practical position on individual issues should not be in dispute with the resolutions adopted. In the Governing Body Commission members’ opinion, these changes were to safeguard the ISKCON development from further shocks.

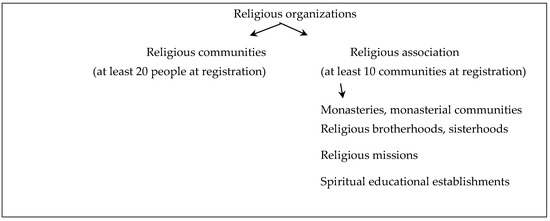

Troubles did not stop there for the ISKCON community in Belarus. In the early 2000s, Belarusian legislation in the religious sphere was changed, resulting in changes in the registration of religious communities. Thus, according to the law of the Republic of Belarus “On the Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organizations”, as amended in 2002, local religious communities were subject to registration if they have at least 20 followers aged 18 and older. Republican networks of local communities—religious associations—can be registered if they have at least 10 communities operating in the majority of regions of the country with at least one of them having operated for at least 20 years (On the Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organizations 2002). This established two types of officially operating religious organizations: local and republican, communities and associations, respectively. Only associations had the rights to establish monasteries and monasterial communities, educational establishments, religious missions, and invite missionaries from abroad (in the case of a foreign organization), etc. (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Requirements of the religious organization headcount for obtaining state registration in the Republic of Belarus.

Adoption of the law entailed mandatory re-registration of all the religious communities and associations operating on the territory of Belarus. Tightening the state registration conditions for religious organizations was connected with the desire of the authorities to control ideology and politics in the setting of establishment of the Belarusian statehood and aimed at maximum exclusion of unwanted foreign influence through the religious sphere. Due to a certain strictness the 2002 revision of the law of the Republic of Belarus “On the Freedom of Consciousness and Religious Organizations” was criticized by human rights defenders (Report by the Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Belarus Adrian Severin 2007). Gokulānanda dāsa recalls that, even though all the requirements were met, re-registration was only completed in 2008 after the Resolution of the UN General Assembly on the human rights situation in Belarus was issued. A significant portion of attention in the Resolution was drawn to the violations of the freedom of religious activities by Krishnaits (interview: 14. Gokulānanda dāsa).

Re-registration costs required significant funds. This happened on the conditions of a general reduction in the amount of spiritual literature, the distribution of which was one of the main sources of income. A debt was accumulated to Bhaktivedanta Book Trust (BBT).

All these led to discontinuation of the Vaishnava farm financing. According to Pāṇḍu dāsa, who lived at the farm in the early 2000s and was responsible for training bulls tillage, the number of cows and bulls at the time reached 60. All the projects for agricultural community development were suspended. The farm had no resources of its own—neither financial, nor human—for proper development. Given the winter seasons, bulls and cows faced the threat of starvation death, which is against the values of the Vaishnava tradition. Pāṇḍu dāsa told that the way out was found accidentally. Already in the first winter, when the farm lacked fodder, cows and bulls headed from the snowy breeding ground to the nearby forest to cover from the wind. There they found a lot of trees with juicy small branches which they were eating throughout the whole winter. They cut down some trees together grasping its branches in turns and bending it until the tree broke down completely and fell on the ground (interview: 9. Pāṇḍu dāsa).

Yuga avatāra dāsa highlighted that a general reaction to the shocks the ISKCON faced in the late 1990s to early 2000s was the introduction to the communities in Belarus and active development of the system known as curating (interview: 3. Yuga avatāra dāsa). As mentioned above, once faced with the crisis of belief, many Vaishnava followers stopped their spiritual practice and left the ISKCON. In response to that, representative of the Governing Body Commission for Belarus and Ukraine, Neal Byers, started implementing the system of spiritual and social care in the communities of the region in the early 2000s. The need to implement the system was due to the understanding by many leaders of the contradiction between the extensive and intensive development of the ISKCON, i.e., despite the constantly increasing growth of the number of newly converted followers of the Krishna Consciousness movement and their active involvement in the preaching projects, their faith had no sufficient deep growth and remained superficial and unstable.

The curating system was to fix the problem to establish a healthy balance between the missionary activities of the devotees and their internal submersion into the Krishna Consciousness practice based on deep faith in the values of the Vaishnava tradition. Curators were selected from among the most experienced devotees. Their duties included regular meetings with the members of the community experiencing certain difficulties. Based on their knowledge and experience, they helped junior Vaishnava followers to form life-purpose reference points through common discussions about spiritual literature, to resolve problematic life situations, and to assist in solving problems that might arise in communications with the members of their families or colleagues at work.

So, starting in the late 1990s, the community in Belarus entered a period of difficulties that resulted in many devotees experiencing the worldview crisis and leaving the ISKCON. In response to that, a curating system was introduced, aimed at promoting strengthening of faith in the community members through trusting and empathic communications with mature Vaishnava followers. It can be said that starting in the early 2000s, along with the community’s extensive activities, its intensive development started growing. Its purpose was to help the spiritual becoming of the members who had already joined, rather than attract new followers.

2010s: A new trend in the late 2000s in the community in Belarus was the growth of the number of family members. During the 1990s and the early 2000s, the bhakti practice implied temple life, which meant that bhakti followers should live in a temple performing the duties assigned to them and regular missionary activities, which mainly consisted of distributing spiritual literature. Life outside the temple was seen as a life in illusion (maya), a condition allowing achievement of a complete spiritual fulfillment. There was a strict respective division into the temple members of the community fully involved in the bhakti practice and non-temple ones who, according to the common understanding at the time, also practiced bhakti but lacked the level of spiritual purity and self-fulfillment that those living in the temple had. In the second half of the 2000s, this line started to vanish because more and more former temple devotees whose age was around 40 years started to marry and live in their own houses and apartments. Since the bhakti practice outside the temple and family life started to become normal, rather than a deviation of spiritual development, the attitude towards community members joining while also maintaining a family turned positive (Gormash 2007).

During the 2010s, family members of the community became more and more involved in the temple life. They took over the kinds of service that was usually performed by the temple devotees—service for the altar deities and the preparation and organization of Sunday feasts. Preaching programs received a non-typical form and were called Goloka Fest (since 2014). The aim of these programs was in presenting bhakti in a popular (non-religious) form. To do that, the programs actively employed popular instruments, covering big issues, such as health, family psychology, raising children, etc. Since 2014, an all-Belarusian annual festival was held, attended by the members of all the ISKCON communities in Belarus and ISKCON members from other countries.

The most effective regular form of the out-of-temple bhakti practice were groups of spiritual communication known as bkakti vriksha. They too were initiated by the family members of the community. They usually invited all those interested in philosophy and Vaishnavism practice to their homes once a week and talked based on spiritual literature—Bhagavad Gita, Bhagavata Purana, etc. Groups of spiritual communication usually consist of 10 to 15 people.

It should be noted that informal communication prevails in such groups. Not only theoretical issues, but also difficulties of daily bhakti practice can be discussed. One of the common difficulties is the situation of religious fanaticism which young people express in their communication with their relatives or colleagues. In such cases, leaders of spiritual communication can often act as mentors and mediators resolving conflicts. Thus, such groups accept a curating function, creating conditions for comprehensive spiritual support of their members.

A conclusion is possible, as currently, the Vaishnava community in Belarus has become: there is a second generation of followers, a temple, an organizational structure, and it is searching for the ways of social integration. Summing up, it is possible to highlight the stages and features of its becoming as follows.

4. Conclusions

Based on the above sequence of events it is possible to mark several distinct stages of the Vaishnava tradition becoming in Belarus.

- 1980s: In the first stage, Vaishnavism appeared and developed spontaneously without any organized form or systemic preaching. It spread among the Belarusian intellectual class and was practiced as their personal hobby;

- 1990s: In the second stage, Vaishnavism was institutionalized once a centralized ISKCON structure appeared, consisting of registered religious communities in different cities in Belarus. This stage is characteristic of social adaptation of the ISKCON communities in Belarus, in which the biggest manifestation was a lawsuit against the community in Minsk;

- 2000s. The third stage was characterized by a range of spiritual and administrative crises, which shook the ISKCON in the former Soviet republics in the late 1990s. Internal reforms in the communities in Belarus resulted in a care system aimed at supporting spiritual becoming of the practicing members of the community;

- 2010s–2021. The fourth stage was characterized by a search of new piety models. The main trend in the life of the communities in Belarus was the out-of-temple bhakti practicing, aimed at popularizing the Vaishnava tradition in the Belarusian society. The social integration of the community deepened, as well as the production cooperation with the state’s scientific structures.

The resource for the Vaishnava tradition in Belarus was and still is the request of its ideas and practices from the seeking Belarusians. Its roots are rather existential than cultural, because it arises in the absence of migrants—authentic bearers of the Vaishnava tradition. It determined the contents of the main stages of distribution (although by the ISKCON general development in the Western world and in India, as well). Long-term spontaneous operation of the Vaishnava environment in Belarus was based on personal interest, which justified the long-term process of its structural formation in the 1990s, ending with administrative crisis. It now continues to develop as an organized community with its internal focus on the groups of spiritual communication and experienced devotees personally curating the newcomers. Traditional forms of preaching are maintained, such as book distribution and common Hare Krishna singing in the city streets. However, one of the key factors contributing to the ISKCON survival and steady development in Belarus is the followers’ orientation to personal goals, prevailing existential requests and hence, the expansion of informal groups (bhakti).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K. and I.T.; methodology, S.K.; software, I.T.; validation, S.K. and I.T.; formal analysis, S.K. and I.T.; investigation, I.T.; resources, I.T.; data curation, I.T.; writing—original draft preparation, I.T.; writing—review and editing, S.K. and I.T.; visualization, S.K. and I.T.; supervision, S.K. and I.T.; project administration, S.K. and I.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Belarusian Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. List of Respondents

| No. | Name at Initiation | Function within the Hare Krishna Movement | Date of Interview |

| 1 | Maitreya dāsa | President of the ISKCON temple in Minsk from 1992 to 1997 | 11.05.2021 |

| 2 | Gaṅgā dāsī | One of the members of the first women’s ashram of the ISKCON community in Minsk | 07.05.2021 |

| 3 | Yuga avatāra dāsa | ISKCON Regional Secretary fo the Republic of Belarus | 23.04.2021 |

| 4 | Mahādeva dāsa | First President of the ISKCON temple in Viciebsk | 07.04.2021 |

| 5 | Vani kṛṣṇa dāsa | Member of the board of tutors (curators) | 01.04.2021 |

| 6 | Nitya priyā dāsī | Member of the board of tutors (curators) | 01.04.2021 |

| 7 | Priya sakhī dāsī | One of the members of the first women’s ashram of the ISKCON community in Minsk | 20.03.2021 |

| 8 | Vāṇīnātha vasu dāsa | President of the ISKCON temple in Minsk in the late 1990s | 19.03.2021 |

| 9 | Pāṇḍu dāsa | Lived and worked at the ISKCON farm for a long time (over 5 years) | 18.03.2021 |

| 10 | Vṛkodara dāsa | President of the ISKCON temple in Minsk in 2000–2004 and in 2005–2013 | 16.03.2021 |

| 11 | Śacī suta dāsa | Leader of the brahmacari ashram of the ISKCON community in Minsk | 10.03.2021 |

| 12 | Vraja kiśora dāsa | Head of the Food of Life program | 15.02.2021 |

| 13 | Dāmodara Paṇḍita dāsa | Regional Secretary in 2000–2007 | 07.02.2021 |

| 14 | Gokulānanda dāsa | Head of the ISKCON Temple Commission in Minsk | 26.07.2018 |

| 15 | Dāmodara dāsa | Was among the first to join the ISKCON community in Minsk | 31.05.2018 |

| 16 | Ojasvinī dāsī | President of the ISKCON temple in Minsk in the late 1990s | 27.05.2018 |

| 17 | Vidyānanda dāsa | Member of Sri Chaitanya Gaudiya Math | 08.12.2017 |

| 18 | Muralī Mohana dāsa | The first Gaudiya Vaishnavism preacher in Belarus | 02.12.2017 |

| 19 | Oṁprakāśa dāsa | Director of Lotus café in 1990 | 22.10.2016 |

| 20 | Gadāpāṇi dāsa | Book distributor | 2007 |

| 21 | Avijñāta dāsa | Book distributor | 2006 |

| 22 | Ādideva dāsa | Book distributor | 2006 |

| 23 | Āmāranātha dāsa | Book distributor | 2006 |

| 24 | Anantadeva dāsa | Book distributor | 2006 |

| 25 | Vedanta kartā dāsa | Book distributor | 2006 |

| 26 | Vraja bihārī dāsa | Book distributor | 2006 |

| 27 | Nāmāmṛta dāsa | Book distributor | 2006 |

| 28 | Sanat-kumāra dāsa | Book distributor | 2006 |

| 29 | Sandhyā avatāra dāsa | Book distributor | 2006 |

| 30 | Śālagrāma dāsa | Book distributor | 2006 |

| 31 | Śaṅkarapriya dāsa | Book distributor | 2006 |

| 32 | Śāstra dāsa | Book distributor | 2006 |

| 33 | Śukadeva dāsa | Book distributor | 2006 |

References

- De Backer, Luc. 2020. The Hare Krishna Movement in Europe. In Handbook of Hinduism in Europe. Edited by Knut Axel Jacobsen and Ferdinando Sardella. Leiden: Brill, pp. 462–527. (In English) [Google Scholar]

- Deadwyler, William. 2004. Cleaning House and Cleaning Hearts: Reform and Renewal in ISKCON. In The Hare Krishna Movement: The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant. Edited by Edwin Francis Bryant and Maria Ekstrand. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 149–69. (In English) [Google Scholar]

- Dergach, Irina. 1993. Pulling heartstrings, or Thoughts about why Belarusian parents firmly decided to fight the ancient Indian God Krishna. In Narodnaya Gazeta. Minsk: Belarusian Printing House, p. 2. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Gormash, Elena. 2007. Hare Krishna! To be wed [about the rite of Veda wedding]. In Trud: Weekly Newspaper about Family and Life. Minsk: Belarusian Printing House, p. 13. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Gurinovich, Irina. 1987. Who calls to heaven? [About Krishnaism]. In Sovetskaya Belorussia. Minsk: Belarusian Printing House, pp. 2–3. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Gurko, Alexandr. 1993. Vaishnavism and Its Features in Belarus. Author’s Abstract of Candidate of Sciences Thesis. Minsk: Institute of Art Science, Ethnographics and Folklore of the Academy of Sciences of Belarus. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Gurko, Alexandr. 1999. Vaishnav Movement (Hare Krishna) and Its Followers in Belarus. Minsk: ISPI. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Ivanenko, Sergey. 2008. Vaishnav Tradition in Russia: History and Current State. Teaching and Practice. Social Service, Charity, Cultural and Enlightenment Activities. Moscow: Filosofskaya Kniga. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Karassyova, Svetlana, and Ilya Tarkan. 2020. Manifestations of Indian culture in modern Belarus. In Handbook of Hinduism in Europe. Edited by Knut Axel Jacobsen and Ferdinando Sardella. Leiden: Brill, pp. 833–48. (In English) [Google Scholar]

- Knott, Kim. 2004. Healing the Heart of ISKCON: The Place of Women. In The Hare Krishna Movement: The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant. Edited by Edwin Francis Bryant and Maria Ekstrand. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 291–311. (In English) [Google Scholar]

- Kosterova, Natalya. 1989. The name of the café was Sankirtana. In Znamya Yunosti. Minsk: Belarusian Printing House, p. 2. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Lirb, Irina. 1996. Shrila Prabhupada, the Veda teacher. In At the Urn of Centuries. Minsk: Belarusian Printing House, pp. 30–31. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Malakhovskaya, Galina. 1992. Small lags to be widely known! In 7 Days. Minsk: Belarusian Printing House, p. 4. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Mohan Das, Murali. 2010. Hare Krishna Yesterday and Today (Issue Four). Revda: Revda printing shop. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Mohan Maharaj, Murali. 2016. Biography. In His Divine Grace Sri Srimad Murali Mohan Maharaj—Acarya—Founder of the Sankirtana Association [Electronic Resource]. Available online: http://www.muralimohan.org/glavnaya/ob-avtore-2/biografiya/ (accessed on 11 May 2021). (In Russian).

- On the Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organizations. 2002. The Law of the Republic of Belarus (as Amended in 2002, No. 137-3) [Electronic Resource]. Available online: https://etalonline.by/document/?regnum=v19202054 (accessed on 5 January 2021). (In Russian).

- Report by the Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Belarus Adrian Severin. 2007. In Human Rights Council [Electronic Resource]. Available online: http://hrlibrary.umn.edu/russian/hr-council/Rsprapporteur_hrtsbelarus.html (accessed on 5 January 2021). (In Russian).

- Rochford, Edmund Burke, Jr. 2007. Hare Krishna Transformed. New York: New York University Press, pp. 181–200. (In English) [Google Scholar]

- Shinn, Larry. 2005. International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON). In Encyclopedia of Religion. Edited by Lindsay Jones. Farmington Hills: Thomson Gale, vol. 7, pp. 4521–24. (In English) [Google Scholar]

- Shturman, Dora. 1986. About the means and ends. In Golos Zarubezhya. No. 40. Jerusalim: Express, pp. 10–24. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Vishnu Swami, Bhakti Bhavana. 2004. The Guardian of Devotion: Disappearance and Rejection of the Spiritual Master in ISKCON after 1977. In The Hare Krishna Movement: The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant. Edited by Edwin Francis Bryant and Maria Ekstrand. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 170–93. (In English) [Google Scholar]

- Titovets, Alexandr. 2000. International Society of Krishna Consciousness. In Neocults: New Religions of the Century? Edited by Alfred Stepanovich Maikhrovich. Minsk: Four Quarters, pp. 182–85. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Wilke, Annette. 2020. Temple Hinduism in Europe. In Handbook of Hinduism in Europe. Edited by Knut Axel Jacobsen and Ferdinando Sardella. Leiden: Brill, pp. 215–348. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, David. 2004. Child Abuse and the Hare Krishnas: History and Response. In The Hare Krishna Movement: The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant. Edited by Edwin Francis Bryant and Maria Ekstrand. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 321–44. (In English) [Google Scholar]

- Zaiko, Svetlana. 1997. Krishnaits in Belarus. In Way to Science: Materials of the 7th Republican Scientific and Practical Conference Marking the 40th Anniversary of the Students’ Scientific Circle on Regional History at Yanka Kupala Hrodna State University, 31 May 1995. Hrodna, Minsk: GRSU, pp. 207–11. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).