Abstract

Kirtan is a musical worship practice from India that involves the congregational performance of sacred chants and mantras in call-and-response format. The style of kirtan performed within Gaudiya Vaishnava Hinduism is an expression of Bhakti Yoga, “the yoga of love and devotion”, and focuses on creating a personal, playful, and emotionally intense connection between the worshipper and their god—specifically, through words and sounds whose vibration is believed to carry the literal presence of Krishna. Kirtan is one of many Indian genres that uses musical techniques to move participants through a progression of spiritual states from meditation to ecstasy. Kirtan-singing has become internationally popular in recent decades, largely thanks to the efforts of the Hare Krishna movement, which has led to extensive hybridization of musical styles and cultural approaches to kirtan adapted to the needs of a diasporic, globalized community of worshippers. This essay explores the practice of kirtan in the United States through interviews, fieldwork, and analysis of recordings made at several Krishna temples and festivals that demonstrate the musical techniques that can be spontaneously deployed in acts of collective worship in order to create intense feelings of deep, focused meditation and uninhibited, expressive bliss.

1. Introduction

I had one of the most idiosyncratic spiritual encounters of my life on a side street through a residential neighborhood in Venice Beach, California. A multinational crowd of revelers, some in Indian dhotis, kurtas, and saris, and some in casual Western dress, sauntered down the road singing, playing drums, and pulling a cart that was decorated with flower garlands, balloons in the shape of smiling cows, and a large statue of the Hindu deity Jagannath.

Down the road I saw him coming toward me—Kermit the Frog in puppet form, dressed in the peach-colored dhoti typical of many Gaudiya Vaishnava worshippers, one hand pressed to his green felt heart and the other raised to the sky in ecstasy. “All glories to [prominent guru] Srila Prabhupada”, Kermit sang out as he passed me, while his puppeteer gave me a knowing smile, before continuing on down the road.

This encounter, humorous as it was on the surface, is indicative of a few important points. First, there is the importance of music not just as a soundtrack to worship, but as a gateway to certain spiritual states of consciousness—in this case, the bliss reflected by the spontaneous dancing of the singers and drummers making up the main parade (see Figure 1 below). Even Kermit the Frog’s posture—more exaggerated on a puppet than it would have been on a person—was a combination of culturally recognized signifiers of ecstasy: the hand on the heart, the other one raised in the air, the head thrown back impossibly far to sing (see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Dancing before Jagannath’s cart.

Figure 2.

Muppet Devotion.

Next, we can read the whole scene as a creative blend of cultural signifiers. The celebration of the Hindu festival Ratha Yatra by a multi-ethnic crowd of Westerners in Indian clothing and South Asians in Western clothing, all of them singing the Indian music known as harikirtan while en route to a famous California beach, was in itself an exercise in cultural exchange. However, there was also a sort of wink and a nod in the combination of signifiers present. Jagannath, the deity on the cart, is revered by many Hindus as an incarnation of the god Vishnu. Some, including the Gaudiya Vaishnavas who organized this parade, conceive of Vishnu and all other gods including Jagannath as incarnations of Krishna, whose pastime herding cattle is one reason why cows are considered sacred by many in India. The emoji-like faces on the smiling cow balloons reflected this connection to Krishna, while also signaling a certain lightheartedness in the deployment of recognizable cross-cultural and pop culture signifiers—as, of course, did the presence of Kermit the Frog sporting the robes commonly worn by gurus and devotees.

The cow balloons and the presence of a Muppet on the parade route also point to my final, and most important point—the fact that humor is welcome. Playfulness is welcome, spontaneous eruptions of idiosyncratic joy are welcome in this style of worship. The performance of harikirtan is an element of Bhakti Yoga—the “yoga of love and devotion”—that seeks to bind the heart of the worshipper to their God through a practice that is joyful, spontaneous, playful, and sometimes humorous.

The musical genre of kirtan involves singing sacred chants and mantras in call-and-response format. Different versions of kirtan are practiced by several religious groups in India, including Sikhs and Sufis. A globalized, contemporary iteration of the style of kirtan practiced among Gaudiya Vaishnava Hindus in Bengal—also called harikirtan, sankirtan, or harinam—has gained particular traction worldwide since the 1960s, largely thanks to the efforts of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), commonly known as the Hare Krishna movement. This essay draws on multi-site ethnography to explore the practice of Gaudiya Vaishnava kirtan with special focus on the experiences and musical performances of ISKCON devotees in North America, as they navigate both Indian and American musical, cultural, and spiritual practices and values. Many of the kirtans performed by American Hare Krishnas are “traditional”, meaning that they are performed using Indian folk instruments, melodies, and musical techniques. Other kirtans, however, have been hybridized with various genres of contemporary popular music, reflecting the needs and interests of a global, diasporic audience. Traditional and hybrid kirtans alike serve to draw participants into spiritually oriented states of consciousness along a continuum between deep, meditative focus and expressive, uninhibited bliss.

This essay is situated at the intersection of musicological research on Vaishnava kirtan, and historical research on American Vaishnavism as a religious movement. Early scholarship on the Hare Krishna movement tended to frame the establishment of ISKCON within the context of new religious movements in the United States by exploring the reasons why American youth might choose to convert, both in terms of countercultural impulses (Judah 1974) and intensive demographic analysis (Rochford 1985). As the movement and its devotees matured, and the organization itself took on a more international character, the scholarship on ISCKON began to focus more on the spiritual practices of Gaudiya Vaishnavism in India, and the challenges of adapting those practices globally (Bromley and Shinn 1989), ultimately forging a narrative more focused on continuity between continents and traditions (Bryant and Ekstrand 2004; Dwyer and Cole 2007).

In the meantime, ethnomusicologists and researchers in related fields have provided a body of excellent scholarship on Vaishnava kirtans as they are performed in different regions of India (see Singer 1966; Henry 1998; Slawek 1988; Schultz 2002; Ho 2013), including research focused specifically on differing musical approaches to Gaudiya Vaishnava kirtan in Bengal (Sarbadhikary 2015). My research focuses on Vaishnava musical practices as they are manifested outside of India, among American Krishna devotees who have developed practices that build on traditions from India while adapting them to contemporary American contexts.

I will begin this essay by explaining the spiritual purposes of Bhakti Yoga, as well as the purposes of kirtan itself, giving special focus to the personal experiences of American devotees as they describe their own states of transformation, spiritual discovery, and bliss found in the kirtan process. I will also discuss musical techniques common to many genres with Indian origins, including kirtan, that are associated with the progression of musical energy between the meditative and the ecstatic, giving due attention to the transformations of traditional kirtan sometimes adopted by American devotees. Finally, I will analyze a representative performance at the Festival of the Holy Name in Alachua, Florida, to demonstrate how the musical techniques of kirtan singing can be deployed in order to lead its participants through a progression of spiritual states from the quietly devoted to the exuberantly blissful.

2. The Spiritual Necessity of Joy

The spiritual beliefs that give meaning to the practice of kirtan have their roots in a cosmology, posited in early Sanskrit musical texts, wherein, at the creation of the universe, the vibration of sound waves brought matter to life. The Sanskrit term nāda-brahman refers to the idea of causal sound, or the belief that sound itself is, as Lewis Rowell writes, “the creative vital force by which the entire universe is animated” (Rowell 1992, p. 36). The 9th century Sanskrit treatise Bṛhaddeśī attributed to Matanga Muni states:

Without nāda, the dance cannot come into being; for this reason the entire world becomes the embodiment of nāda.In the form of nāda, Brahma is said to exist; in the form of nāda, Viṣṇu.In the form of nāda, Pārvatī; in the form of nāda, Śiva.(Matanga 1928)

This conception of sound as the source of sacred, life-giving power is reflected in a Hindu pantheon populated by musically inclined deities like Sarasvati, who plays the veena; Ganesh, who plays the drums; Shiva Naṭarāja, the “Lord of the Dance”; and most significantly for our purposes, Krishna, the divine flute-player. This connection between the vibration of sound and the sacred powers of the universe will be important to understanding what exactly it is that Gaudiya Vaishnavas hope to accomplish by bathing themselves and their environment in music.

In the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna outlines three primary paths to salvation: Karma Yoga, the yoga of compassionate action; Jñāna Yoga, the path of knowledge; and Bhakti Yoga, the “yoga of love and devotion”. It is common, in discussing India’s religious history, to refer to a Bhakti “movement” within Hinduism that began to sweep India starting in the 6th century C.E., and foregrounded these personal, emotional elements of love and devotion. This idea of Bhakti reformation as a singular movement has been problematized in recent years by scholars including John Stratton Hawley, who has noted the role of 20th century writers like Rabindranath Tagore in shaping this concept of a Bhakti movement that executed what Hawley has called “a national integration in both space and time”, serving to both “knit together India’s many regional literatures” and “[form] a bridge that spanned between the Classical period and its modern counterpart” (Hawley 2015, p. 3).

The set of wandering mystics who are generally credited with setting off the first sparks of the Bhakti “movement”, such as it may have been, were Tamil-speaking saints known as Alvars, which roughly translates as “one who has mystical intuitive knowledge of God and who has merged himself in the divine contemplation” (see Gupta 1991; Johnson 2009). Thomas Hopkins describes the Bhakti Reformers as carrying a message that “was highly emotional and intensely personal; it was their own relationship to God that they expressed, conveyed in terms of human feelings—love, friendship, despair, and joy” (Hopkins 1971, p. 117).

This very personal approach to worship rests in a conception of divinity as embodied in a personal God—Krishna, in the case of Gaudiya Vaishnavism—with whom a personal relationship is possible. Harvey Cox describes this level of devotion as resting in “the idea of a personal God who becomes incarnate in a particular figure revealing what God is about and eliciting a form of participation in the life of God” (Quoted in Gelberg 1983, pp. 27–28). Hopkins adds,

That whole orientation toward a personal deity of compassion and concern, and of love, who is not just some kind of absolute, impersonal reality in the Vedantic or Advaitic sense, but a Personal Being of infinite compassion, one who is concerned for those suffering in the world, appeals to something very deep within the human spirit.(Quoted in Gelberg 1983, p. 116)

There is a regional flavor to many Bhakti movements, to discuss them in the plural. The Alvars, for example, propagated a style of Bhakti devotionalism which was strongly influenced by the language and culture of the Tamil-speaking southern region of the Indian subcontinent. Sukanya Sarbadhikary writes about the mapping of Hindu cosmology onto the landscape of India as “sacred geography”, in which certain auspicious locations are associated with “a form of intensely emotional place-making” (Sarbadhikary 2015, pp. 1–2).

In the case of Gaudiya Vaishnava Hinduism, that auspicious location is Bengal, where certain landmarks are reputed to be important sites in the life of Krishna. Additionally, if, as Stephen Slawek writes, bhakti movements “[form] around a central figure who [is] regarded to have experienced some kind of direct contact with the Divine” (Slawek 1988, p. 78), the central character of Gaudiya Vaishanvism is the 15th century Bengali saint Chaitanya Mahaprabhu.

The lore surrounding Chaitanya focuses heavily on the singing of kirtan as a means of spreading the message and practice of Bhakti Yoga, with great emphasis laid on the extraordinary emotional intensity of the kirtans that he led. Chapter 13 of the “Madhya Līlā” section of the Chaitanya Caritamṛta reads:

When Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu danced and jumped high, roaring like thunder and moving in a circle like a wheel, He appeared like a circling firebrand.Wherever Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu stepped while dancing, the whole earth, with its hills and seas, appeared to tilt.When Chaitanya Mahaprabhu danced, He displayed various blissful transcendental changes in His body…When Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu fell down with a crash while dancing, He would roll on the ground. At such times it appeared that a golden mountain was rolling on the ground.(Prabhupada 1974)

Chaitanya’s devotees conceived of their guru as an incarnation of Krishna himself, but took the ecstatic flavor of Chaitanya’s approach to Vaishnavism a step further. If the intense, irresistible love between Krishna and his divine lover Radha is held up as the great metaphor for the ideal relationship between man and God, followers of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu believed that he was an incarnation of both Radha and Krishna at the same time. Sarbadhikary writes of the “ultimate divine irony” that “Krishna, the repertoire of greatest possible bliss, could not taste of his own sweetness (madhurya), though Radha…could. With a fine stroke of the imagination, the two thus decided to incarnate in the same body, to taste each other’s love (prem) in the same site. So Chaitanya was literally born as the perfect embodiment” of Radha and Krishna’s divine love (Sarbadhikary 2015, p. 3). For this reason, the style of kirtan-singing propagated by Chaitanyas’ followers “puts the utmost premium on devotees’ being able to experience these divine erotic moods at their own most embodied, visceral levels” (ibid.).

Over the next several centuries, Chaitanya’s followers established the school of thought sometimes known as Bengali Vaishnavism, or Gaudiya Vaishnavism. There are, within the umbrella of Gaudiya Vaishnavism, several distinct schools of thought distinguished by different temple and worship as well as musical practices. A pivotal moment in this history of Gaudiya Vaishnavism came in 1965 with the journey of Srila A.C. Bhaktivedanta Prabhupada from India to New York City, where he established the International Society of Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), commonly known as the Hare Krishna movement.

The rise of ISKCON in the 1960s was inextricably entangled with American counterculture, and a widespread interest among “hippies” in seeking an expanded consciousness through so-called “Eastern” spirituality, even as practices such as free love and the use of mind-altering drugs ran in direct opposition to the regulatory principles of ISKCON. Srila Prabhupada’s first kirtan recording was performed on a harmonium borrowed from Alan Ginsburg. The hit Broadway musical Hair featured blissed-out hippies singing the Maha Mantra. The Hare Krishna movement found its most prominent supporter in George Harrison, who donated the property that would become known as Bhaktivedanta Manor and produced the 1971 album Radha Kṛṣṇa Temple at Abbey Road under the Apple Records label. The single “Hare Kṛṣṇa Maha Mantra” performed strongly on the pop charts in both Europe and the United States, while Harrison’s own chart-topping single “My Sweet Lord” featured a gospel choir singing both “Hallelujah” and “Hare Krishna”.

The years following the death of Prabhupada in 1977 were turbulent, as scandals and power struggles plagued the leadership of ISKCON. The 1980s saw ISKCON further rocked by allegations of child abuse at gurukula schools, while declining membership numbers reflected the fallout of 1960s practices that encouraged asceticism in young male devotees by eschewing family life, and marginalizing women in the process. Nevertheless, the movement successfully shifted its focus toward a lifestyle that included marriage, family, and more gender equality, as detailed in E. Burke Rochford’s Hare Krishna Transformed (Rochford 2007), thus ensuring intergenerational continuity.

Today, ISKCON claims 10,000 devotees residing full-time at ISKCON temples, along with an estimated one million congregational members worldwide (see Factsheet 2019, religionmediacentre.org, accessed on 29 July 2021). The American and Western European temple communities first established in the 1960s and 70s have been joined by temple communities in Africa, Latin American, and especially in Eastern Europe following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the fall of the Iron Curtain. To date the organization’s online directory lists 398 temples, 41 farming communities, and 178 other centers located on all continents (see centres.iskcon.org, accessed on 29 July 2021). Most importantly, ISKCON has embraced what Rochford terms a “Hinduization” of ISKCON, both in terms of Indian-born residents of the United States worshipping in large numbers at American ISKCON temples, and the establishment of temple communities in India populated by both Indian and foreign-born (including American) devotees.

The displacement of ISKCON devotionalism from the original sites of Gaudiya Vaishnavism in Bengal has required devotees to employ some creative approaches to retaining a sense of spiritual groundedness in the land of Krishna. Sarbadhikary writes that “ISKCON devotees embody a distinctive sense of place” because they locate Vrindavan, the reputed homeland of Krishna, “anywhere on the global stage where there is an ISKCON temple and where devotees come together to render devotional service”. In this way, a devotee’s distance from the sacred sites of Gaudiya Vaishnavism is rendered “immaterial, if every physical site where they offer devotional services transforms into Vrindavan” (Sarbadhikary 2015, p. 154).

Many devotees separated in time and space from the Bengali origins of Gaudiya Vaishnavism have nevertheless anchored their own spiritual experiences in reverence toward the founding guru of their movement, Srila Prabhupada. Statues of Prabhupada occupy positions of honor in ISKCON temples, and many devotees from ISKCON’s first generation describe milestones in their spiritual lives in terms of their meetings with Prabhupada. Los Angeles devotee and drummer Bada Hari described Prabhupada as “the best musician I’ve ever heard”, after hearing a recording in a temple gift shop. “I think it was because of this point: he was actually singing from his heart. He was singing real feelings, real emotions, about things that actually exist in reality. It’s not illusory and there’s not a hint of false ego in his music…it’s all just him singing out of pure love to Krishna”.

ISKCON temples around the world are sites dedicated to the central tenets of Bhakti Yoga—namely love and devotion, as expressed through the development of a personal relationship between the devotee and Krishna. All devotees are expected to engage in acts of “devotional service” that express dedication to Krishna, and may include activities ranging from cleaning the temple and cooking food for the temple community to decorating the altars and dressing the statues of deities in colorful fabrics and flower garlands.

Any act done with a heart inclined toward Krishna may be considered an act of devotional service—and in many instances, that devotional service may involve participating in the visual and performing arts, which express a certain spiritual necessity of beauty. Along with the performance of devotional service, there are elements of worship that exist to bind the senses to Krishna. The 12th chapter of the Bhagavad Gita reads:

For those whose minds are attached to the unmanifested, impersonal feature of the Supreme, advancement is very troublesome. To make progress in that discipline is always difficult for those who are embodied.But those who worship Me, giving up all their activities unto Me and being devoted to Me without deviation, engaged in devotional service and always meditating upon Me, having fixed their minds upon Me, O son of Prthā—for them I am the swift deliverer from the ocean of birth and death.(Prabhupada 1989)

The statues of Radha and Krishna on the temple altar, along with a variety of figures representing other avatars or demigods, are necessary for the practice of darshan, or coming face to face with the deity and exchanging gazes, with the figures on the altar acting as proxy for the divine personalities represented. This practice of taking darshan by exchanging gazes with a figure representing the deity is practiced throughout the Hindu world. Diana L. Eck describes Hinduism as an “‘image-making’ religious tradition in which the sacred is seen as present in the visible world” because “the day-to-day life and ritual of Hindus is based not upon abstract interior truths, but upon the charged, concrete, and particular appearances of the divine in the substance of the material world”. Therefore, within Hinduism “the eyes have a prominent role in the apprehension of the sacred” (Eck 1996, p. 10).

The deities on the altars of ISKCON temples, along with the paintings, decorations, and often highly detailed architecture of the buildings themselves, all serve to bind the soul of a devotee to Krishna through the sense of sight. Coward and Goa describe darshan as an “exchange of vision that is itself a form of ‘touching,’ of intimate knowing”. They go on to make the connection between darshan and music, because “so also the practice of hearing and speaking the mantra is an act in which the consciousness of the individual may experience a tuning into the divine sound of the cosmos” (Coward and Goa 2004, p. 6).

The other senses are bound to Krishna through the scent of flowers and incense, the taste of the consecrated foods known as prasadam, and the kinesthetic movement of dancing—the type of performance, according to Susan L. Schwartz, that provides a “path through bodily experience toward ultimate and religiously defined transformation” (Schwartz 2004, p. 20). Francine Daner writes that through all of these sensory experiences “the senses of the individual become dovetailed with the supreme senses of Krishna, and the living being attains the pleasure and happiness that is otherwise impossible to find” (Daner 1976, pp. 34–35).

At a personal level for many artistically inclined devotees, participation in the arts becomes their form of devotional service. The temple community surrounding the New Raman Reti temple in Alachua, Florida, is one where I have personally observed a great focus on the creation of beauty as devotional service, from the cultivation of Bharata Natyam troupes and prominent kirtan bands, to simple things like drawing colorful chalk designs on the floor of the temple entrances before a festival. Even though the designs will likely be gone by mid-day, the creation of something beautiful, even something temporary, is a sign of dedication.

Sukha Dasa, a longtime devotee and educator in the Alachua community, wife to the painter of the New Raman Reti temple murals and mother to one of the Bharata Natyam dancers, explains that: “Krishna was at the center of everything [in Vedic culture], so all drama revolved around Krishna and his pastimes. All music revolved around Krishna and his pastimes. All art revolved around Krishna and his pastimes. Everything was meant to elevate peoples’ consciousness, not degrade it”. Raga Swan, a recording artist that I met at the same temple, told me that “God gives gifts, talents as they call it in the Bible, to be returned to him in service…These desires will stay with you, lifetime after lifetime sometimes. And they’ll haunt you completely. For example—you’re interested in music. When did that start for you?”.

As these sensory, artistically beautiful elements of worship serve to forge that emotional connection between ISKCON devotees and their personal God, it is important to understand how the personality of Krishna plays into this combination of the beautiful and the playful, the spontaneous and the personal in Gaudiya Vaishnava worship. The name Krishna can be translated as “the all-attractive”; Edward Dimock writes that “man seeks God because he is by his nature attracted to that which is of greatest beauty and sweetness” (Dimock 1966, p. 62). Krishna is often characterized as beautiful, playful, youthful, mischievous, always dancing and playing the flute.

Krishna’s flute figures prominently in Hindu iconography, apparent not only in temple altars and paintings of Krishna, but in performances dedicated to him, ranging from the hand gestures used in Bharata Natyam and other Indian dance forms, through Bollywood dance numbers that frequently put flutes in the hands of their young, romantic male leads. Devotees attribute symbolism to Krishna’s flute that is similar to the reed flute described by Rumi and other Sufi poets: the hollowed-out reed represents a soul emptied of ego and purified by the suffering of being pierced to form the finger holes of the instrument. Thus emptied and purified, the soul becomes an instrument in the hands of God.

The fact that Krishna is a playful god is an important aspect of his worship through Bhakti Yoga. During a lecture at the ISKCON temple Sri Sri Radha Krishna in Spanish Fork, Utah, the temple priest encouraged his congregation to take note, while visiting different temples, of what the deities are doing in the various artistic representations on display. In Sarasvati temples, the deity will be engaged in distributing blessings; in Shiva temples, the deity will be performing acts of meditation. However, in Krishna temples, the deity is singing, dancing, and generally having a good time. However, according to the temple priest, none of this means that Krishna is a frivolous god. Krishna’s pastimes are, in fact, a profound revelation about the nature of the Spiritual world. According to Sri Sri Radha Krishna temple president Caru Das,

Krishna’s a reservoir of pleasure. He’s not material, he’s full of knowledge, bliss, and eternity, and he’s not weighed down by all the considerations that burden us, a person maintaining this body and mind, and so he’s more or less always in a celebratory mood…so it’s not really surprising if you think about it that there’s a lot of music in the spiritual world, a lot of music, a lot of dancing. Because there is nothing other than celebration once you shed this bag of earth, water, air, ether, bag of mucus and bile and phlegm. Once you no longer have to drag it around with you, you can really fly and sing and dance and do all those things. Right now we’ve got a ball and chain around us—it’s called the material body. But…Krishna doesn’t have any of those limitations and he’s always to be portrayed with his flute…it epitomizes the joy of the spiritual world.

The fact that Krishna’s eternal personality is perceived as a joyful personality translates into the use of joyful acts like singing and dancing as acts of worship. Longtime ISKCON devotee Kurma Rupadasa explains that

The process of worshipping god is joyfully performed. In other words, we understand god—Krishna. One of his characteristics is that he’s full of bliss, and so as one practices yoga then one should experience happiness. Bliss is of course a spiritual state. If one is practicing bhakti yoga properly then he will experience—if not happiness, at least he will experience peace. Or at least he will experience a cessation of suffering.

Author and recording artist Hridayananda Das Goswami, who joined ISKCON in 1970 and has served in many leadership positions within the organization, explains that:

The soul just naturally dances, it sings. We are not ultimately or originally impersonal. The experience that we have now of ourselves, “I am a unique individual person”—that’s eternal. We are eternally unique persons and it is our nature to rejoice to sing to dance…It’s the very nature of the soul.

3. The Yoga of Music

If, in Bhakti Yoga, the process of worship is intended to be joyfully performed, then singing and dancing are sacred acts that serve as gateways to exstasis, or the experience of holy ecstasy.

Kirtan, as I described it earlier, is the musical performance by a congregation of sacred chants and mantras in call-and-response format. Kirtan singing is led by a kirtaniya, who strings together mantras and verses of poetry, or different melodies for a single mantra that is sung over a period ranging from 15 min to an hour or so. The sound of kirtan is nearly omnipresent during worship services, at festivals and yoga classes, in parades like the Ratha Yatra, and piped over loudspeakers in temples, food distribution centers, and other gathering spaces for Krishna devotees. The spiritual purposes of kirtan are served by several distinctive aspects of the practice, including the language used in the chants and mantras, the use of call-and-response, and the deployment of both traditional and hybrid musical styles in kirtan performance.

Singing kirtan is considered by devotees to be an act of yoga, or “yoking” the soul to God, and this perception hinges on certain beliefs about the words themselves that are being sung. There are many sacred texts drawn from Hindu scriptures that may be sung as kirtan, but Gaudiya Vaishnavas give special emphasis to singing mantras composed of names for Krishna. Krishna is said to have at least 108 names, and any of the “holy names” may be used as a text for kirtan—“Govinda Govinda Gopala”, for example. However, the most common mantra used in Gaudiya Vaishnavism is the Maha Mantra, or “Great Mantra”:

Hare Krishna Hare KrishnaKrishna Krishna Hare HareHare Rama Hare RamaRama Rama Hare Hare

One interpretation of the mantra that devotees shared with me is that this particular set of names refers to the supreme nature of God (Krishna), his attributes (Hare), and his personal nature (Rama). However, Hare is also a name for Radha the divine lover, making the mantra itself an expression of the love between Radha and Krishna, so that by chanting the names Hare and Krishna together, every iteration of the mantra reaffirms the vital nature of the deity as love.

Music may have multiple distinct functions within worship contexts, such as praise, instruction, remembrance, purification, etc. Two important theological functions for our purposes are epiclesis, or, to borrow a phrase from Guy L. Beck, “the tonal invitation of any deity or spirit to a sacrifice or worship occasion” (Beck 2006, p. 17); and koinonia, or communion, a “solidarity of feeling between the human and divine realms” (Beck 2012, p. 157). Some types of music are intended to cross the boundary between the visible and invisible words; to borrow a phrase from Karen Ralls-McLeod’s work on Celtic music, “music is seen as a universal ‘connector’ to the Otherworld”. (Ralls-McLeod 2000, p. 15).

Inherent in the use of the Maha Mantra is the belief that the dualism fundamental to language, the schism between signifier and signified, does not exist in the case of the Holy Names. I have frequently heard devotees explain to visitors at their temples that in ordinary language, the sounds making up the word “knife” are not actually the same thing as the sharp metal object currently being used to cut your bread. However, within Gaudiya Vaishnavism, Krishna is the great exception to that dualism.

Earlier we introduced the concept of nāda-brahman, a belief that sound itself is sacred because the vibration of sound is the animating creative power that gives life to the universe. Coward and Goa write that “the mantras are symbols that participate in that to which they point. The entire sonic universe, with all its gods, planes, and modes of being, is manifested in a certain number of mantras. By chanting the mantra one awakens all the cosmic forces that correspond to it” (Coward and Goa 2004, p. 47). According to Gaudiya Vaishnava doctrine, the sound of Krishna’s name is literally imbued with his energy, and by bathing oneself in the sound of Krishna’s names, one comes into direct personal contact with Krishna himself. Edwin Bryant refers to the names of Krishna as “perpetually accessible sonic avatara”, or “Krishna in vibratory form”, (Bryant 2007, pp. 15–16) and Neal Delmonico describes them as “a perpetual descent or an enduring appendage of Krishna in the world” (Delmonico 2007, p. 551).

This is the focal point of the entire practice of kirtan, and devotees use a variety of metaphors to make their point. Ananda, a devotee from ISKCON farming community New Vrindaban in West Virginia, explains that the purpose of kirtan is “to purify the heart. We want to understand our identity. We want to understand God”. He quotes a Sanskrit verse by Caitanya Mahaprabhu, “ceto-darpaṇa-mārjanam”, referring to the consciousness, a mirror, and cleansing: “the consciousness is compared to a mirror that is covered with dust at the present moment” but may be cleansed by chanting.

Former Brooklyn temple president Ramabhadra Das describes kirtan as a science, one of “the different spiritual sciences [that] help one re-establish or reawaken one’s dormant love” toward God. Music, according to Ramabhadra, is a means of cultivating a type of devotion that is “hardwired into the Spirit”, and he makes a comparison with the intense fervor of young Beatles fans watching their favorite band perform on the Ed Sullivan show. “The Beatles were great people, don’t get me wrong”, he says. “They’re very nice people and they helped the Hare Krishna movement a great deal. But the point is: it was a mundane [sound] vibration. It was a mundane vibration, but because of the dynamics of the nature of our own souls” even the mundane music drew out hysterical reactions from the fans. “Every living entity, even a tiger, wants to be loved, because that’s inherent. And God’s the supreme lover…We’re given the opportunity to carry out this process [of kirtan] in the material realm to qualify ourselves to once again enter the spiritual realm, to enter an eternal loving relationship which we have with God, but forever. Forever”.

The belief that Krishna’s presence is carried directly through the sonic vibration of his spoken name shapes not only the practice of kirtan as a conscious act of communion for the benefit of those who sing, but also the belief that singing kirtan is a form of service. In this formulation of divine name as divine presence, any living being within earshot of the chant, and even the environment where kirtan is sung, is spiritually cleansed by Krishna’s presence. Slawek quotes the kirtan singers he interviewed in Benares as saying that “By uttering good words, the pollution in the air is counteracted…we believe that our kirtan benefits the welfare of the whole world” (Slawek 1988, p. 84).

The first waves of Hare Krishna converts in the 1960s gained notoriety for singing in airports, and to this day the chanting of harinam in public spaces is a significant aspect of devotional service for ISKCON devotees. These public performances of kirtan are commonly regarded as a form of proselytization, but they’re also intended to serve the communities where they are sung by bringing the divine presence to the airport, or the sports stadium, or the college campus. Delmonico writes that “chanting to oneself, in one’s mind or in a whisper, is beneficial for oneself, but chanting loudly is beneficial for oneself and for all those who hear. Loud chanting is thus said to be a hundred times more beneficial than silent chanting” (Delmonico 2007, p. 552).

ISKCON devotees also perform kirtan in public spaces while observing the festival of Ratha Yatra. Ratha Yatra is a centuries-old, pan-Indian Hindu festival which is celebrated by parading statues of the deity Jagannath and his siblings on chariots through the streets. ISKCON has its own variations on Ratha Yatra, and it’s no coincidence that the largest annual Ratha Yatra parades in North America are accompanied by hundreds, if not thousands, of devotees singing kirtan while passing through New York City’s Fifth Avenue and California’s Venice Beach.

These festivals take the temple experience into public spaces, allowing non-devotees the chance to hear kirtan and take spontaneous darshan with the deities on the carts, while their presence raises the spiritual vibration of these cultural centers themselves. These large-scale public kirtans perform the function of epiclesis. Beck writes that epiclesis is part of a process of “bringing the cosmos to completion or perfection” by inviting the divine presence into the physical spaces inhabited by humans, so that the process of singing is “perpetually linked to the ongoing process of healing, rebuilding, and reinforcing the cosmos”. Thus the music, or at very least the ritual that contains the music, becomes “the workshop in which all reality [is] forged” (Beck 2012, p. 56).

The celebration of Ratha Yatra in important public spaces represents a large-scale manifestation of this belief in the physically transformative nature of kirtan. On a smaller scale, I have watched devotees at the llama farm attached to the Sri Sri Radha Krishna temple sing kirtan while giving medical care to an injured llama, believing that if the llama were to die, the kirtan it heard in its final hours would raise it to a higher state and allow it to be born as a higher form of being in its next reincarnation. Practices like these tap into the idea of sound-as-psychopomp, the spiritual function of music that Beck describes as “the principal vehicle that [transports] the musician and the listener to heavenly states in the afterlife” (Beck 2012, p. 200). I have even watched devotees toss out a spontaneous “Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna” to an insect running across the floor mid-interview.

Kirtan is not only a form of yoga that connects the individual devotee to their God, but it is also a collective yoking that connects participants to each other, largely through the mechanism of call-and-response. Unlike most forms of performative music intended for stages and studios, kirtan is intended to encompass everyone within earshot. One thing I learned very quickly while visiting ISKCON temples is that there is a strong expectation—or at least a strong hope—that visitors to the temple will not simply sit and politely listen to the service. The hope is that every person in the building will sing, or at very least move along with the music. The ultimate goal of kirtan is to bind the heart of the devotee to their god, but the interaction between participants is also an expression of Bhakti Yoga.

Kishor Rico, who performs with kirtan band The Mayapuris, describes it this way:

[Kirtan] encourages us to live in a higher conscious reality and be loving and thoughtful in every act that we do. And if you are around somebody sharing love…that’s what kirtan is. Even you see it’s call-and-response: it’s always giving and receiving. It helps us to practice that in our everyday lives with our interactions with our family and with our friends and with strangers.

During a performance at the Festival of Colors in Spanish Fork, Utah, Kishor demonstrates this importance of call-and-response. The Mayapuris’ performance at this festival is a study in walking the line between the performative and the participatory in music, and Kishor addresses that tension almost immediately by telling the crowd: “Just because we’re on stage doesn’t mean this is a performance. Kirtan means that we’re in this together, so your clapping, your singing, your dancing is just as important as my drumming, as his singing, as the whole band up here. So that you can partake in this beautiful practice, we’re going to teach you the words”.

Kishor and his bandmates then take several minutes to teach their primarily non-Hindu audience the words of the mantras through verbal call-and-response, using gestures with the microphone to “throw” the call-and-response back and forth between the audience and the band. Then, the music begins, and even at the moments when the band members let their performative talents fly using complex vocal melismas, they first pause to teach their audience members how to use their arms and hands to follow the melodic contour of those melismas, so that the crowd is still participating kinesthetically in the music.

The different musical styles used in kirtan performance carry their own layers of meaning, especially in regard to ISKCON’s delicate balance between tradition and hybridity. American Hare Krishna devotees, and by extension, American kirtaniyas, occupy a complex, contested, and often controversial space at the intersection of Indian musical tradition and the demands of global audiences with an interest in stylistic diversification. Even outside of the realm of music, Sarbadhikary has noted extensive areas of conflict and contradiction that exist between ISKCON and other Gaudiya Vaishnava groups over a wide range of issues.

One value of particular importance in understanding traditional Indian music, as well as Indian spirituality in general, is the concept of guru-śiṣya-paramparā, or faithful master-disciple succession. ISKCON devotees frequently refer to guru-śiṣya-paramparā in terms of their relationships with their spiritual gurus, and if the spiritual heritage of Hare Krishna kirtan lies purely in India, then the melodies and musical practices of any given kirtan should date at least as far back as Srila Prabhupada, if not farther.

At the same time, ISKCON exploded onto the American cultural scene during the 1960s counterculture, as part of a cultural milieu in which, according to Rochford, new religious movements like ISKCON tended to be “antistructural”, in the “spirit of protest”, “prophetic movements challenging the existing social order”. Rochford observes that in a countercultural context, “new religious groups create structures, practices, and symbols meant to integrate followers into their unconventional religious worlds” (Rochford 2007, p. 6). So if the spiritual heritage of Hare Krishna kirtan lies in 1960s America, at least some departure from tradition might be expected.

I have observed both the traditional and the transformative in American kirtan. Many prominent kirtaniyas of ISKCON’s second generation have spent formative years in India, training in classical Indian music and performing music as devotional service at temples in Bengal. Bhaktivedanta College in Mayapur, India, offers a regular Kirtan Course, in which devotees are trained in traditional instrumental and drumming techniques, as well as studying recordings of melodies created by Srila Prabhupada and other gurus (Sarbadhikary 2015, p. 191; also https://kirtancourse.com/, accessed on 29 July 2021). Even for those ISKCON devotees who have never trained formally, traveled to India, or taken the Kirtan Course, certain common melodies are especially beloved because they were Prabhupada’s favorites.

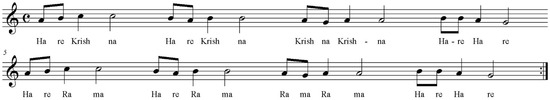

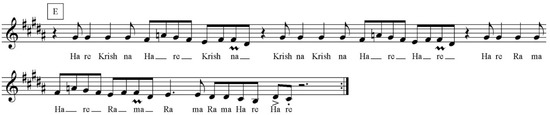

One such melody is featured in the “Hare Kṛṣṇa Mantra” single recorded by George Harrison and the London temple devotees as part of the Radha Kṛṣṇa Temple album, transcribed here as Figure 3:

Figure 3.

“Hare Kṛṣṇa Mantra” melody.

This particularly beloved melody has figured into most kirtans that I have heard at American temples. I have heard entire kirtans dedicated solely to this melody. Many devotees appear to have deep emotional attachments to this melody, and I have often seen this melody deployed at the climax of a kirtan, triggering a markedly ecstatic emotional release on the part of all participating.

The melodies and musical traditions inherited from Prabhupada are clearly prized by many musicians within the Hare Krishna movement. At the same time, I have always heard kirtaniyas insist on the spontaneous nature of kirtan, the flexibility of a communally learned wellspring of melodies, and the possibility of a talented kirtaniya adding something new.

All of this said, the sound most often heard at American ISKCON temples is what devotees casually refer to as “traditional kirtan”. Traditional kirtan is essentially performed in the style of Indian folk music, using Indian tonalities, drumming patterns, vocal ornamentations, and most importantly, Indian instruments. The instruments heard in nearly every traditional kirtan include the harmonium, a small portable keyboard; karatala, or hand cymbals; and the mridanga drum, as seen in Figure 4. Other instruments such as the bansuri flute or violin may be used depending on what the devotees have on hand.

Figure 4.

Devotees playing Harmonium, Mridanga and Karatala.

One particularly important instrument is the double-headed mridanga drum (which, to be clear, is a different instrument than the South Indian mridangam that is commonly played in Karnatic classical music). Mayapuris lead singer Visvambhar Sheth explains that the lightweight and portable mridanga, which is sometimes called the khol, was invented by Chaitanya Mahaprabhu for the specific purpose of playing kirtan while dancing. Furthermore, he explains, the two heads of the drum carry meaning: “The small [treble] side represents Radharani, the big [bass] side represents Krishna—it’s high and low like their voices”. Thus the drum itself carries the same symbolism as the belief that Chaitanya was a simultaneous incarnation of both Radha and Krishna, the wild love of the divine pair contained in a single being—or, in this case, a single instrument.

Some ISKCON drummers, including Visvambhar, have studied Indian classical music and traditional tala rhythms. However, even for those untrained ISCKON (2021) devotees who have learned drumming organically by simply taking part in the kirtan, the rhythms they’ve absorbed from within the practice are based in the complex talas of Indian music, and play into the hypnotic, trance-like effect of kirtan. John Blacking, in his seminal work How Musical is Man?, describes music as an experience which fundamentally disrupts our perception of time, or what he calls “a world of virtual time” in which “people become keenly aware of the true nature of their being” and experience “freedom from the restrictions of actual time and complete absorption in the ‘Timeless Now of the Divine Spirit.’” The end result of musical participation, he writes, is that “we often experience greater intensity of living when our normal time values are upset, and appreciate the quality rather than the length of time spent doing something” (Blacking 1973, p. 52).

The drumming in kirtan is one of the musical elements that serves to invite participants into this “world of virtual time”. Drummer Bada Hari describes his instrument as a spiritual being and his relationship to it as a spiritual interaction. “Everything is the energy of God, and especially things that are directly used to glorify God actually have their counterpart in the spiritual world, so that they actually have a personality”, he says. Depending on the state of mind in which he takes up the drum, “Some of the times when I play with that intention, the drum actually begins to start playing me. I get the feeling from the drum, and the beats come from the drum. I basically lose external consciousness and it becomes a totally spontaneous kind of experience”.

As significant as the sounds and instruments of traditional kirtan are, many kirtaniyas adopt elements of modern popular music genres into hybrid styles of kirtan. Sarbadhikary writes that in the perspective of ISKCON, “the modern becomes spiritual if used for devotional service; otherwise it remains material” (Sarbadhikary 2015, p. 162). Devotees have frequently reminded me that Krishna’s name means “the all-attractive”, and that Krishna will use all things, including all styles of music, to attract all people to him. While I have almost always heard only traditional kirtan inside temple rooms and as part of temple services, I have often noticed the use of hybrid kirtan styles at outdoor festivals, for example, where they serve not only the purpose of worship for the in-group, but also as an introduction to kirtan for the out-group, non-devotee audience.

While it would be impossible to name all of the styles of hybrid kirtans in circulation, I have observed several distinct approaches to hybridizing kirtan with other popular music genres, both in terms of structure and musical styling.

One approach is to simply perform the kirtan in an alternate style while retaining the basic kirtan structure of repeated verses of mantra sung in call-and-response. “Thief of Hearts” by prominent kirtan singer Jai Uttal (2011), for example, simply translates the chant “Govinda Govinda Gopala” into a reggae style, adding a thumping bassline, heavy backbeat, and a back-up chorus singing the kirtan responses in a manner distinctly reminiscent of Bob Marley and the I-Threes. Lyrically and structurally, however, the performance is pure kirtan.

Another approach is to essentially sing a song about Krishna consciousness, in which verses that talk about Krishna and the spiritual life are interspersed with rounds of mantra sung as a chorus. The classic rock-inspired outfit TK and Namrock (2007), for example, perform a song called “It’s My Nature”, which includes verses such as:

It’s my nature to rock and rollJust ‘cause I do don’t mean I ain’t got soulIt’s my nature, it’s my natureI do it for Krishna‘Cause he’s the ultimate goal.

After singing a few verses about kirtan, TK calls out “Everybody sing now” and begins performing rounds of the mantra itself.

There are also different approaches to actually merging the kirtan’s traditional musical elements with popular music genres. A kirtaniya may simply perform all things musically in their alternate genre, with the mantra lyrics being the only part of the performance that is recognizably connected to the Indian origins of Gaudiya Vaishnavism. A performance by Lokah Pavana, for example, simply lays the conveniently symmetrical Maha Mantra over the distinctive thumping “dembow” rhythm of Reggaeton.

Other kirtans actually hybridize the musical style itself, using traditional melodies and traditional vocal styles, but with an alternate genre layered in. One particularly fascinating festival performance is a collaboration between the Mayapuris and fellow kirtan band The Kirtaniyas at the Festival of Colors held at the Sri Sri Radha Krishna temple in Spanish Fork, Utah. The performers in both bands are extensively trained in Indian music, having spent formative years at the major temples in Vrindavan. Both bands, however, play with alternate genres at times, including reggae, hip hop, and for this performance, Electronic Dance Music. During their shared set in Spanish Fork, the performers frame their performance in specifically hybrid terms, shouting “East meets West!” as members of both bands take the stage carrying mridanga and harmoniums. Meanwhile, Nitai from the Kirtaniyas mans the laptop and fills the space with a dense layer of electronic noise. Following a hand gesture from Mayapuri Kishor, Nitai draws the electronic sounds down to a complete stop. After a dramatic moment of silence, the drummers in both bands launch into a dense groove of acoustic Indian folk percussion, while the audience leaps into the air and dances with a frenzy of energy.

Over the next hour, the bands sing mantra melodies that I, as a frequent visitor to ISKCON temples, recognize as being part of the oral repertoire of common kirtan melodies. Both lead singers use distinctly Indian vocal melismas, and the instruments of traditional kirtan are very much present on the stage. There’s simply an added layer of dense electronic noise that has its own musical shape, and at the moments when the electronic component of the music reaches its climax and subsides, the acoustic, traditionally Indian sounds emerge from the texture as a reminder of the constant presence of the deep tradition of kirtan, regardless of what modern innovations may be added to it.

Hridayananda sees reflections of the Vaishnava emphasis on the holy name throughout world religions. ”If you study world religions including Buddhism, not to speak of the overtly theistic religions [such as] Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, in all these traditions there is a clear notion that God is present in his name”. He perceives the fundamental character of kirtan in music found throughout the world:

They did kirtan. Western culture is full of kirtan. If you look at the great figures like Bach, Handel, Mozart, and of course others—Vivaldi was a Jesuit priest. They wrote a tremendous amount of sacred music. Handel’s Messiah…was done very consciously and very specifically to glorify God. So yeah, kirtan is universal. In the Vaishnava tradition that we practice and promote there is really a unique amount and quality of knowledge about God, and you know the saying “ye shall know the truth and the truth shall set you free”. So when you do kirtan with a very powerful understanding of who you’re glorifying I think it makes it all the more powerful. [But] Kirtan is very much a part of sacred culture all over the world.

4. Participation and Progressive Energy

I have asked many kirtaniyas over the years about the process of performing kirtan—i.e., the techniques involved with putting together melodies and mantra in the moment of performance—and found that they most often insist on the spontaneity of the process. “Oh man, I never know what’s going on”, quips Visvambhar—who is, to be clear, among ISKCON’s most prominent professional musicians. “It is a practice where…you have your former training and practice of the tunes and the rhythms”, he acknowledges. “So when we have the right combination of people together and everyone drumming and singing” the kirtan comes together as a spontaneous creation.

Bada Hari, in conversation with Visvambhar, says “I think you’d agree that there’s an art to putting together a kirtan”. However, he also insists on the fundamental spontaneity of the experience. “It becomes really ecstatic and then people kind of think, ‘Okay do it again.’” After pausing for a hearty laugh, he adds, “But I didn’t do that, I was just sitting there singing. If anything wonderful happens it’s certainly by the grace of the Lord”. According to Bada Hari, the process transcends individual musical talents: “The kind of amazing thing about kirtan is, it’s not really within our power…We try to nicely call out to Krishna and if he by his grace appears in the kirtan, believe me—it will be fired up. It happens by his grace”.

With this said, there are certain musical techniques often found in kirtan, whether deployed consciously or spontaneously, that enhance the state of exstasis associated with worship in Bhakti Yoga. In formulating a music theory of kirtan, it is useful to evaluate the rhythmic, melodic, and kinesthetic dimensions of a kirtan—i.e., the dance elements, the physical expressions of musical energy—in terms of two important traits: a progressive musical intensity that takes kirtan singers from a state of deep focus to ecstatic bliss, and an emphasis on participation rather than the presentational quality of a performance.

In his article “The Rationalization of Intensity in Indian Music”, Edward O. Henry notes that one of the most important traits of Indian music is emotional intensity. Many of the most prominent genres in Indian music feature a gradual progression toward this intensity, from a more static, less intense emotional state to a dynamic, very intense state. This progressive energy characterizes classical genres like Dhrupad, Khyal, and both Hindustani and Karnatic styles of raga; a wide range of folk songs and dances; and many of the song picturization sequences in Bollywood movies—the 2003 hit Kal Ho Naa Ho, for example, even has a plot point wherein the medically fragile character Aman lands himself in the hospital by dancing through the acceleration in the music at a wedding party.

Not all of these genres are associated with religious practices, but there is still often an underlying recognition that both ends of the static-ecstatic continuum of progressive energy are spiritual states of consciousness. The qawwali music used for worship in Sufi Islam, for example, shares many traits with Gaudiya Vaishnava kirtan, from the responsorial format to the use of the harmonium, and even a mythology that emphasizes the symbolism of a reed flute and the relationship of lovers—in this case, Layla and Majnun—as the great metaphor for a relationship between man and god. Sufi theologian ‘Alī al-Hujwīrī, now revered as the patron saint of Lahore, described the spiritual exstasis achieved through music and dance as the moment when “the agitation of ecstasy is manifested and conventional forms [of expression] are gone, that agitation is neither dancing nor foot-play nor bodily indulgence, but a dissolution of the soul…It is a state that cannot be explained in words” (Sakata 2000, p. 754).

Henry lists nine specific musical techniques that are often used to generate the increasing levels of intensity in Indian music, leading toward that state described as a “dissolution of the soul”:

- (1)

- Progression from free rhythm to a fast, structured beat;

- (2)

- Acceleration of tempo;

- (3)

- Dynamic crescendos;

- (4)

- Increasing rhythmic density, meaning that the surface rhythms of the melody and the drumming become more compact and focused;

- (5)

- A rising melody line;

- (6)

- Holding a high melody note for a long time;

- (7)

- What Henry terms an “arousing lyric”; I would add that a familiar and well-loved kirtan melody can have a similar effect;

- (8)

- A wide melodic range; and

- (9)

- The use of cross-rhythms in drumming (Henry 2002, pp. 48–49).

In formulating a framework for the musical analysis of kirtan, it is also important to recognize the distinction between participatory and presentational music. The objective of kirtan is not to perform a discrete piece of music from a repertoire of known pieces, even one as functional in the worship context as a hymn in a hymn book. The objective of kirtan is to participate in a certain process, or to invite as many people as possible to become involved in an act of “musicking”. This is the term that Christopher Small famously proposed to describe music as a process in which “the more actively we participate, the more each one of us is empowered to act, to create, to display, then the more satisfying we shall find the performance of the ritual” (Small 1998, p. 54).

Music intended for participation utilizes different techniques than music intended for performance, because musicians perfecting their art for a stage or a recording are fundamentally working with a different set of values and priorities than a kirtaniya assembling melodies into an experience in which, as Thomas Turino writes in Music as Social Life: The Politics of Participation, “a collection of resources [are] refashioned anew in each performance like the form, rules, and practiced moves of a game” (Turino 2008, p. 59). There are certainly many kirtan bands and solo artists like Jai Uttal, the Kirtaniyas, and the Mayapuris, who perform on stage, make studio recordings, and develop fan followings, and those artists develop their musical technique to an advanced level. However, even those stage performances and recordings walk a complicated line between the polish and planned composition of performative music, and the repetition and open-endedness of participatory music.

Turino outlines several distinctions in musical technique between what he terms participatory and presentational music, i.e., music as activity vs. music as art object. Participatory music usually has an unscripted, open form, in comparison to the scripted closed forms of presentational music. Participatory music is generally less complex, more repetitive, and less focused on individual talent or virtuosity, since the goal is to be accessible for amateur, untrained musicians; whereas presentational music is more complex, balances repetition with contrast for the sake of audience interest, and focuses on the display of individual virtuosity for the listeners’ pleasure (ibid.).

Those kirtans that most effectively serve to induce the spiritual states of consciousness associated with Bhakti devotion often combine the musical techniques of progressive intensity found in Indian music—i.e., acceleration, crescendo, increasing rhythmic density, rising and wide-ranging melodies, etc.—with the open-ended, repetitive, accessible characteristics of the best participatory music. In the next section I will analyze a specific kirtan performed at a Florida music festival in order to illustrate how these techniques for creating musical ecstasy may be combined by a skilled kirtaniya.

5. Techniques of Ecstasy

If the first generation of ISKCON converts made a name for themselves by chanting in public spaces like airports and sports events, the dedication of the younger generation is evidenced in the rise of the kirtan mela, or the festival organized around a certain span of time—often 24 h, but sometimes 48, 72, or even 96 h—dedicated to the focused chanting of kirtan. While kirtan is often sung as an accompaniment to longstanding Hindu festivals like Rath Yatra, Holi, Gaura Purnima, Krishna Janmastanmi, etc., the relatively recent kirtan mela is a festival in which intense immersion in the kirtan process is itself the object of celebration. Kirtan melas are often organized around a lineup of kirtaniyas who each lead the music for an hour-long set, and while the expectation is that festival attendees will come in and out of the music as it suits them, the objective of the festival is to offer the opportunity for near-continuous, intensive immersion in the kirtan process, with all of its attendant spiritual states. A promotional article for a kirtan mela in West Virginia quotes recording artist Gaura Vani, founder and frontman of the kirtan band As Kindred Spirits, as saying that “with all our faults, the one thing the younger generation has got right is our love for chanting” (Smullen 2009).

An hour of kirtan led by Jahnavi Harrison at the Festival of the Holy Name in Alachua, Florida, provides an ideal example of the progressive energy and participatory fervor of a well-crafted kirtan in its rhythmic, melodic, and kinesthetic dimensions. Jahnavi Harrison is a London-born recording artist and radio personality who was raised at Bhaktivedanta Manor, the ISKCON center famously donated to Srila Prabhupada by George Harrison, and as such she represents this second generation of ISKCON devotees that has driven the rise of the kirtan mela (see Jahnavimusic.com, accessed 29 July 2021).

The Festival of the Holy Name is held on the grounds of the New Raman Reti temple in Alachua, Florida. Various tents offer activities for children, food distribution, etc. However, the focal point of the festival is a large tent holding around 200 people at any given time, decorated with colorful lights and fabrics. There is no stage inside the kirtan tent; the only figures that are elevated above the ground are the statues of deities displayed on tables, but kirtaniyas and instrumentalists alike sit on the floor at the center of the room, on the same level as the festival participants who will follow them in the kirtan, as seen in Figure 5. This is a deliberate choice to not elevate any one person above others—Charles R. Brooks writes that “Bhakti movements have always been a force subversive to ideological inequality” (Brooks 1989, p. 25), and this choice not to elevate one singer honors that egalitarian character of Bhakti Hinduism.

Figure 5.

Kirtan at the Festival of the Holy Name, with Jahnavi seated at the center.

During her kirtan set, Jahnavi takes this egalitarian character of kirtan one step further by sharing the microphone with fellow musicians Gaura Vani, Visvambhar, dancer Vrinda Sheth, and some of the instrumentalists gathered around this central group. While Jahnavi introduces all of the major melodies and shapes the energy of the kirtan from her seat in front of the harmonium, she passes the microphone back and forth regularly, allowing each musician in this central group to put their unique vocal stamp on a repetition or two of the mantra.

A primary trait of Indian music that builds intensity is the pattern in which a piece of music begins slowly, thoroughly exploring all melodic materials, then gradually becomes faster and more rhythmic until it reaches a climax. Perhaps the most well-known example of this is the basic alap/gat structure of classical raga, which begins with a drone, then a free rhythm introduction in which the lead performer gives every note of the raga a focused and melismatic treatment before introducing a pulse, then a meter, and finally progressing toward a climactic jhala.

Jahnavi’s kirtan necessarily modifies a few aspects of this drone-free rhythm-fast beat model for progressive energy. The drone, for example, is replaced with a few slow chords played on the harmonium. Rather than opening in free rhythm, a beat and meter are introduced right away, as the distinctive “ching-ching CHING, ching-ching CHING” of hand cymbals takes over almost as soon as the singing has begun. In a large group event like a kirtan mela where participation is paramount, the performance of rhythm—whether by drumming, playing on the hand cymbals that are dispersed throughout the crowd, or simply clapping along—is one of the most efficient ways for everyone inside the tent to become immediately involved in the music and enter that state of “virtual time” that Blacking posited as emblematic of deep musical experience.

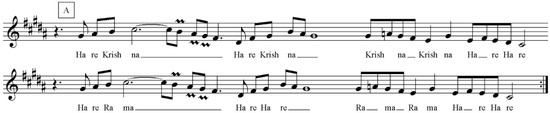

The melody that Jahnavi chooses to open with, however, is perfectly suited to the expansive and somewhat rhythmically flexible character of the early, meditative section of a piece with progressive energy. The melody she chooses (labeled in Figure 6 as melody A) has a wide melodic range, and rises to a long, high, held note—both of which Henry names as traits of music with intensity.

Figure 6.

Melody A.

In addition, this melody allows for what Turino calls an “ever-expanding ceiling for challenge”, (Turino 2008, pp. 46–48) which encourages participation by singers of varying levels of ability. The experienced singers passing the microphone for each “call” of the call-and-response are able to engage more deeply in the musical process by adding expressive vocal ornamentation that is clearly reflective of their training in Indian classical music. Meanwhile, the less-experienced members of the congregation simply sing the melody straight during their “responses”. The size of the crowd allows for what Turino calls a “cloaking” effect that makes it more comfortable for less-confident singers to participate as loudly as they want without becoming self-conscious.

Both singers and drummers relax into a steady mid-tempo groove after about ten minutes when Jahnavi introduces a more rhythmically regular melody B, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Melody B.

Much of the kirtan is spent alternating between melodies A and B. Turino emphasizes the fact that repetition is a significant factor in inviting participants to take part in a musical performance, and the repetition of melodies also adds to the hypnotic character of the kirtan. As Jahnavi and the singers thoroughly explore the musical possibilities of melodies A and B at slower tempos (roughly 80 BPM for melody A, and 96 BPM for melody B), the audience sways slowly from side to side, many with eyes closed but their faces oriented upward, in an emotionally charged, hypnotic absorption in music and mantra. After an initial nine or ten rounds through each melody at a slower tempo, Jahnavi returns to A, then B, then A again for seven iterations each, at which point the music becomes markedly more rhythmic and the tempos begin to flow, gradually increasing to 132 BPM.

A great deal of the progressive energy of a kirtan—and the artistry of the kirtaniya—lies in stringing together (and repeating) melodies in a way that allows participants to both fully lean into the musical possibilities of each tune, and also experience the shifts in energy that are brought on by changes in the melody.

Essentially, a kirtaniya shapes progressive energy by deciding:

- (1)

- What melodies are sung;

- (2)

- How many times they are sung;

- (3)

- How the melodies will flow into and relate to each other, whether by organic progression of similar melodies or the juxtaposition of contrasts in melodic range, contour, or rhythmic density; and

- (4)

- How the melodies shape the energy of a kirtan by manipulating states of meditation vs. ecstasy, focus vs. expansiveness, etc.

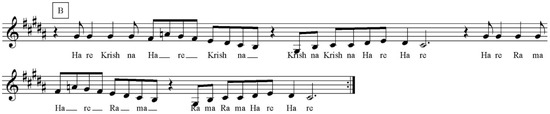

Henry describes increasing rhythmic density as one of the important traits of emotional intensity in Indian-derived music. After spending roughly twenty-five minutes exploring melodies A and B in an easy, flowing rhythm, Jahnavi begins ramping up the energy with short, simple melodies (transcribed in Figure 8 as C and D) that streamline the surface rhythm into a steady run of eighth notes and simplify the melodic motion to basic runs down and up the scale (or vice versa). In the process she moves the tempo ahead to an energetic 152 BPM.

Figure 8.

Melodies C and D.

Meanwhile there is an intensive kinesthetic dimension to the kirtan that serves to invite devotees to participate more deeply in the kirtan, and then enhance the mounting state of ecstasy for those involved. I like to refer to a range of “gestures of ecstasy” on display during kirtan, or common behaviors that appear to be culturally conditioned through long-term participation in kirtan with other ISKCON devotees. These gestures convey recognizable emotional states, such as raising the arms above the head to convey excitement or opening the hands around the heart to express joyful contemplation. Kirtans are commonly performed in temple rooms where a de facto division into men’s and women’s sides of the room often emerges, and certain distinctive gestures of ecstasy are common on either side. There is often more of a collective, dance-like character on the women’s side of the room, as participants gather into loosely packed groups and engage in spontaneous but semi-coordinated and artful dancing. The men’s side of the room tends to become something of a devotionally repurposed mosh pit, where devotees jump up and down rapidly during passages with a fast surface rhythm, and shift into explosive vertical leaps at the moments when the music opens out into a more expansive melody.

Even at an event like the Festival of the Holy Name, where there is no gendered division in the crowd space, a ring of standing devotees forms at the edges of the tent, where groups of women begin dancing in and out of the central space, sometimes visibly struggling to keep up with the tempo of the music, and laughing about it when they do (see Figure 9). Meanwhile, men at the corners of the tent attempt to execute the highest vertical leaps possible.

Figure 9.

Dancing to Jahnavi’s Kirtan.

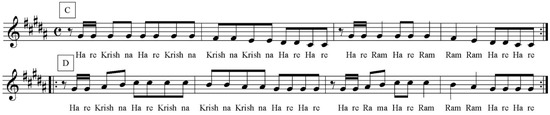

After ramping up intensity and speed through melodies C and D, Jahnavi makes a marked break in tempo, reining the music in to about 126 BPM, and introducing a variant on melody B, transcribed in Figure 10 as E. Here, she repeats the first phrase of her melody—a phrase that desperately wants to resolve tonally. However, she withholds the resolution three times, finally ending with an abrupt and percussive “Rama Rama Hare Hare!” Meanwhile, the dancers in the back add a heavy dipping step to their dance in order to match the groovy, off-kilter feeling of this melody.

Figure 10.

Melody E.

During this section, there is an interactive character to the kinesthetic dimension of the kirtan that enhances the sense of participation among the singers. At various moments Jahnavi and the other singers who share the microphone will gesture to the audience to do some modified, unpredictable, and playful call-and-response patterns between different groups within the tent. Turino’s characterization of participatory music as being like “the practiced moves of a game” comes to mind (Turino 2008, p. 59). When passing verses of the mantra back and forth, the singers will raise their arms in a throwing gesture as if they are literally tossing the music back and forth across the room. At the same time, many of the men start flinging their arms upward in an enthusiastic “V” while adding a “Krishna Krishna Hare Hare” or “Rama Rama Hare Hare”, sung at the top of their register, to the end of each soloist’s call.

Jahnavi follows this slower, more funky section with another tempo change, streamlining the rhythm into a steady flow of eighth notes that accelerate not only the surface rhythm, but the rate at which the mantra is repeated, singing in two phrases what previously took four. Henry lists an increase in rhythmic density as one of his techniques for maximizing intensity in Indian music, in terms of both melodic surface rhythm and compact, focused drumming patterns. At this point in Jahnavi’s kirtan, the tempo accelerates markedly, first to 168 BPM, then on to a frenzied pace well past 200 BPM. By now the musicians are spitting out mantras at a rapid rate—between Jahnavi and the congregation, they sing twenty rounds of the mantra in about a minute and twenty seconds, which is approximately the time spent on a single round of call-and-response at the beginning. When Jahnavi suddenly breaks out of this frenzied, focused rush of eighth notes with a long, slow run up the opening notes of melody A, it has an exhilarating, dramatically expansive effect on the audience.

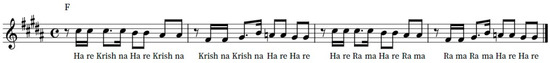

After twenty more minutes and several more changes in melody accompanied by distinctive shifts in energy, Jahnavi introduces one more new melody, transcribed in Figure 11 as F, which is sung at a relatively high pitch range and features an angular rhythmic and tonal character. These musical characteristics create the impression of a spontaneous outburst and a sensation of great freedom.

Figure 11.

Melody F.

Kirtans vary in the manner in which they end, and sometimes kirtaniyas, having progressed from a meditative to an ecstatic energy, bring the experience full circle by returning to meditative contemplation. After bringing melody F up to a frenzied 200 BPM, Jahnavi suddenly breaks the tempo and takes it back to a very slow, fluid, ornamented and emotional return first to melody B, then melody A, the musical focal points of the whole experience. The effect of this return to a meditative state, as singers and dancers alike catch their breath, returns the kirtan experience from an outwardly expressive display of ecstasy back to an internally focused, personal communion with the holy names of Krishna. Many singers in the crowd are visibly emotional, closing their eyes, swaying from side to side, and placing their hands over their hearts, or raising a single graceful hand into the air.

6. Conclusions

The earliest stories about Caitanya Mahaprabhu teaching his followers to sing Hare Krishna emphasize the extraordinary joy of his kirtans, and the achievement of an ecstasy so intense that it could only be the incarnation of love between two gods. These stories about Caitanya also present him as an iconoclast; as someone who came to remake the older forms of religious orthodoxy by replacing them with something spontaneous and new, and adaptable to many circumstances.

The Hare Krishna kirtans sung in airports by the first generation of ISKCON converts in the 1960s presented an important moment of change in the history of kirtan. The kirtan melas popularized by ISKCON’s successive generations marked another evolution in the history of Gaudiya Vaishnava kirtan, as devotees found new ways of immersing themselves in the ecstasy of chanting and making the teachings of Caitanya relevant and transformational in their lives.

By April of 2020, ISKCON’s Krishna devotees found themselves, along with the rest of the world, facing the altered reality of the COVID-19 pandemic. In-person religious practices were cancelled for safety reasons, and even the thought of a large gathering of people tightly packed in a tent to sing together began to seem like a relic from a more innocent time. So, the committee behind the annual Festival of the Holy Name in Alachua proposed a new event: the Global Pandemic Kirtan, to be held in virtual space. Devotees from all over the world signed up to stream kirtans from their homes, where families and small groups each took a turn broadcasting their microkirtans over Facebook Live—many of them the same second generation kirtaniyas who had popularized the kirtan mela, now surrounded by their own small children around the harmonium. Requests to participate came in from all over the world, and all told more than 400 musicians from 150 countries streamed 360 h of continuous kirtan over fifteen days. Some of these videos went legitimately viral, with a video by UK devotee Kishori Jani and her family eventually receiving 30 million views on Facebook. Organizers of the event stated their intent to continue streaming future kirtan melas in virtual space, even at whatever point in future time the subsiding of the pandemic should allow for a return to in-person worship (Smullen 2020).