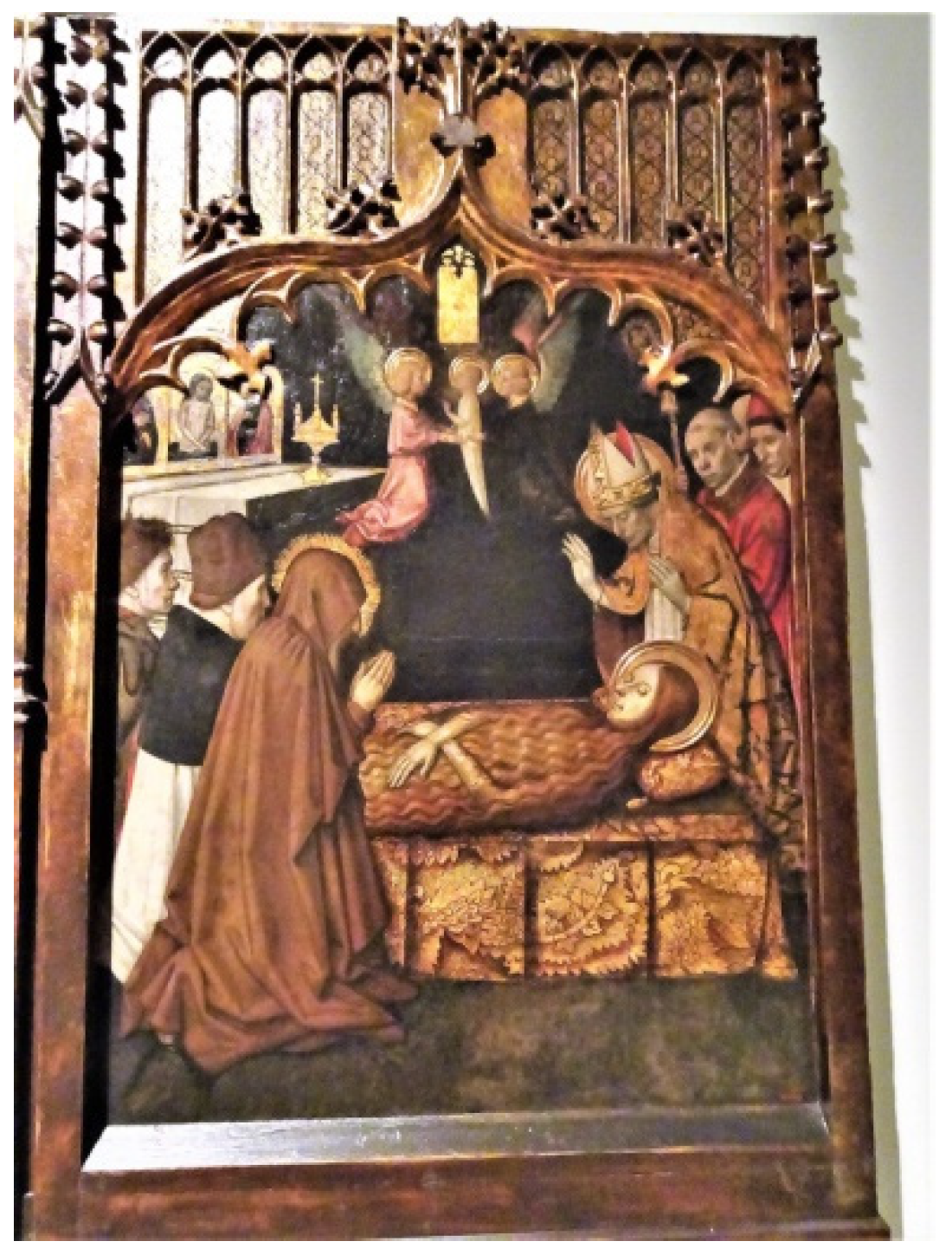

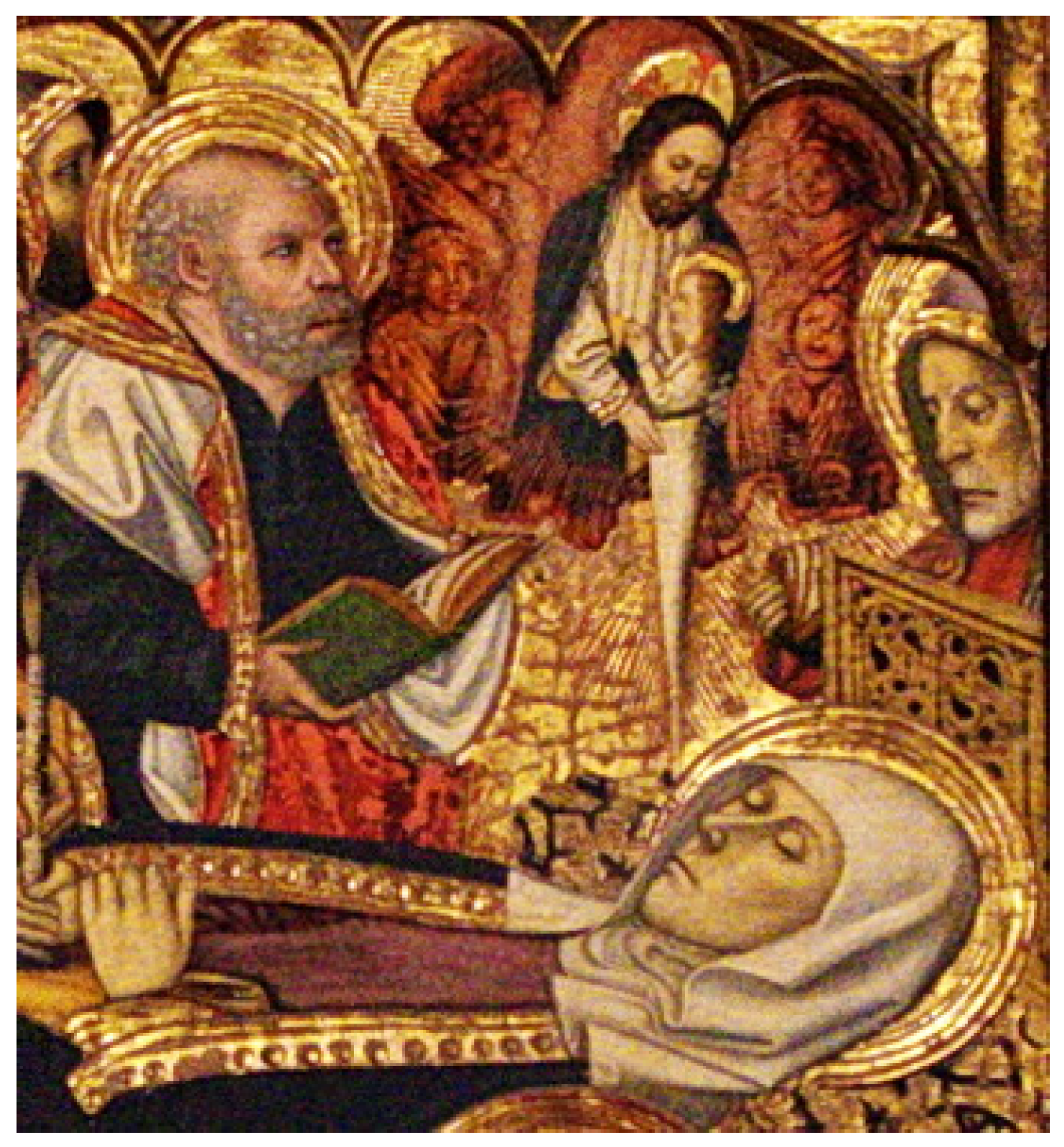

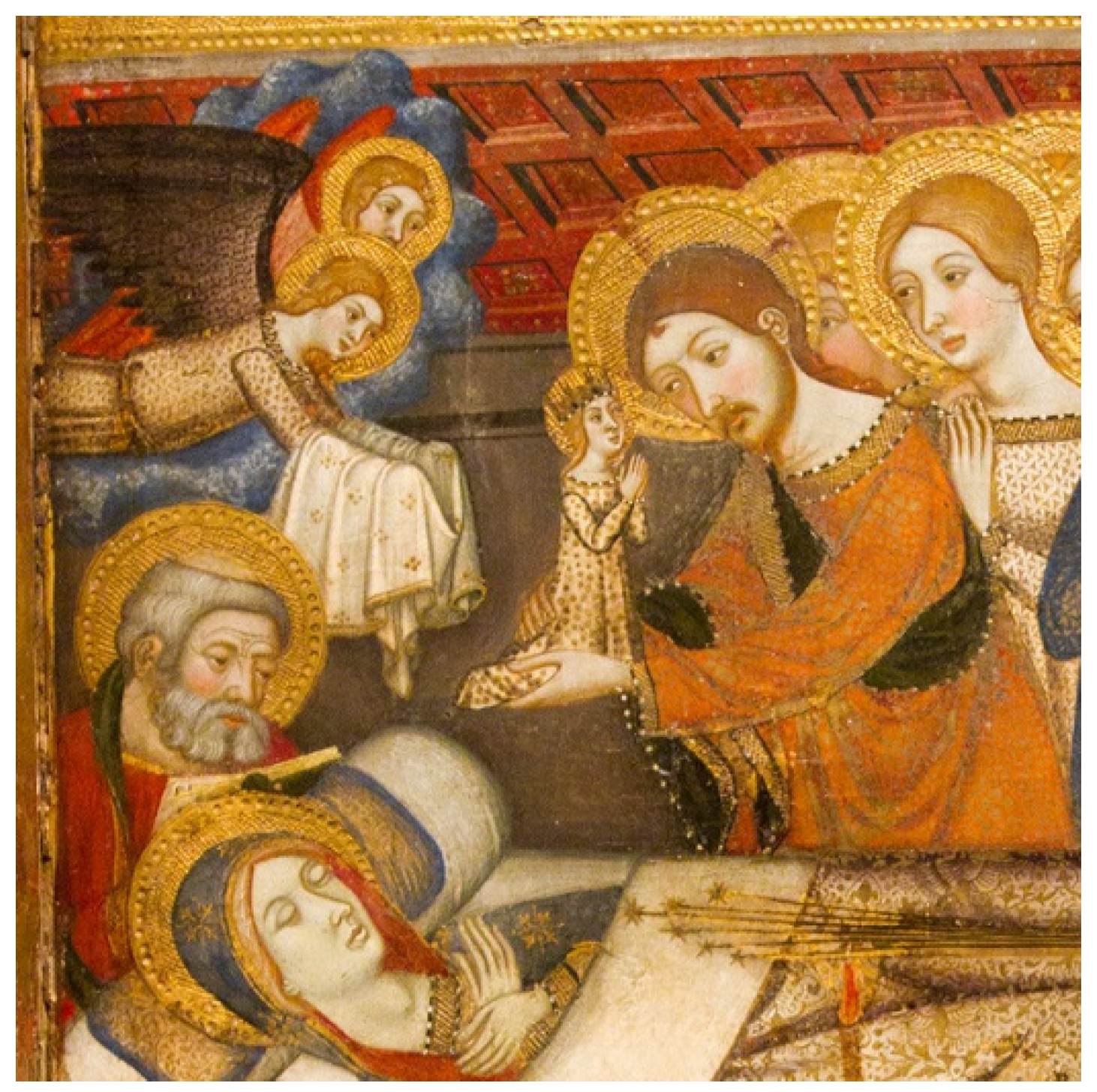

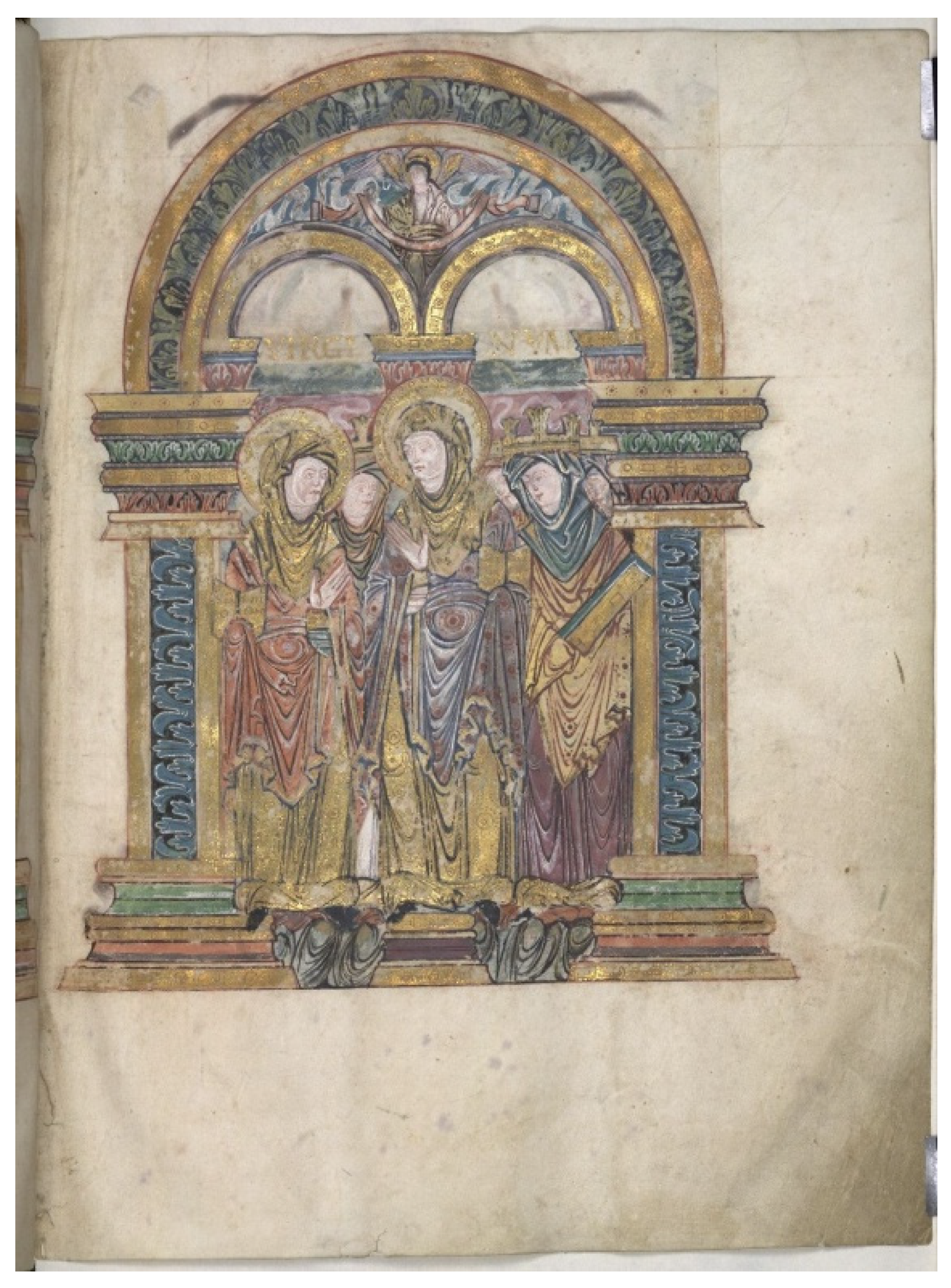

The Transit of Mary Magdalene’s Soul in Catalan Artistic Production in the 15th Century

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. The Death of Mary Magdalene in La Legenda Aurea and Its Vernacular Translations

2.2. The Soul of the Virgin in the Sources

“But after having suffered by men in accordance with what is written and after having resurrected on the third day and risen to Heaven after forty days, when you should see me come to you in the company of angels and archangels, of saints, of virgins and of my disciples, you can be sure then that the time has come for your soul to be separated from your body and conveyed by me to Heaven, where it will never suffer any tribulation or anguish”.

“He took her soul and put it in Michael’s hands, not without having wrapped it beforehand in something like veils whose radiance it is impossible to describe. But we the apostles saw that Mary’s soul, on being delivered into the hands of Michael, included all the bodily members, outside the sexual difference, with nothing but the semblance of all [human] bodies in her and a whiteness seven times greater than the sun’s. Peter, for his part, overcome with joy, asked the Lord, saying: ‘Who of us has a soul so white as Mary’s?’ To which the Lord replied: ‘Oh, Peter! The souls of all who are born unto this world are the same, but on departing the body they are not so radiant because He sent them in one condition and in others [very different] He found them, on having loved the darkness of many sins. But if one keeps oneself from the tenebrous iniquities of this world, their soul will delight in such whiteness on departing from the body”.

2.3. Shared Visualities

2.3.1. A Death with Witnesses

2.3.2. Ascension to Heaven

2.4. The Relationship between the Virgin and Mary Magdalene

2.4.1. Chastity and Virginity

2.4.2. Incarnation, Pain and Resurrection

“The Lord gave immense benefits to Mary Magdalene and He distinguished her with very significant shows of predilection […]; He honored her with his trust and friendliness; […] He treated her constantly with understanding and gentleness […] for love for her He resuscitated her brother Lazarus […] she was the first one to whom the resurrected Jesus appeared and the one entrusted by Him to communicate His resurrection to the others, thus becoming apostle of the apostles”.(LA, I, p. 384)9

2.4.3. Sermons and Writings from the 15th Century in the Crown of Aragon

“Magdalena: see to it that my mother is the most important thing I leave behind in this world and thus you will serve me. Love her and serve her: I leave her to take my place to console all of you. […]. Do not stray from her authority and attend to her advice and obey her. She will be your mother and your teacher. […] You will stay by my beloved mother’s side for twelve years, and afterwards you will be completely orphaned of father and mother […]. Magdalena, for your harsh and great penitence, you will be given invaluable consolations. […] And at the end of your life, I will come for you and bear you to my Glory”.

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For more information on the different legends about Mary Magdalene (see Collet and Messerli 2008; Saxer 1959). |

| 2 | |

| 3 | In order to study the fact that Jaume Huguet depicts the departure of the Virgin’s soul and that of Mary Magdalene in the same way, it would be essential to count on sources that are not accessible today, such as the contract for those works of art. Nevertheless, a hypothesis can be put forward by turning to the concept created by Jan Bialostocki (1972) of a “framing theme” (Rahmenthemen), given that this would be a solution when creating a new kind of iconography making use of a previous compositional layout along with another series of artistic aspects. |

| 4 | From among the numerous apocryphal accounts of the Assumption, only the ones most representative for the proposed aims ones have been selected, using the Santos Otero edition (Santos Otero 2001). |

| 5 | “Más después que hubiere sufrido por los hombres conforme a lo que está escrito y después que hubiere resucitado al tercer día y subido al cielo al cabo de los cuarenta días, cuando me vieres venir a tu encuentro en compañía de los ángeles y de los arcángeles, de los santos, de las vírgenes y de mis discípulos, ten por cierto entonces que ha llegado el momento en que tu alma va a ser separada de tu cuerpo y trasladada por mí al cielo, donde nunca ha de experimentar la más mínima tribulación o angustia.” |

| 6 | “Él tomo su alma y la puso en manos de Miguel, no sin antes haberla envuelto en unos como velos, cuyo resplandor es imposible de describir. Mas nosotros los apóstoles vimos que el alma de María, al ser entregada en manos de Miguel, estaba integrada por todos los miembros corporales, fuera de la diferencia sexual, no habiendo en ella sino la semejanza de todo cuerpo (humano) y una blancura que sobrepasaba siete veces a la del sol. Pedro, por su parte, rebosante de alegría, preguntó al Señor, diciendo: ‘¿Quién de nosotros tienen un alma tan blanca como la de María?’. El Señor respondió: ‘¡Oh Pedro!, las almas de todos los que nacen en este mundo son semejantes, pero al salir del cuerpo no se encuentran tan radiantes, porque en unas condiciones se las envió y en otras (muy distintas) se las encontró, por haber amado la oscuridad de muchos pecados. Mas, si alguno se guardare a sí mismo de las iniquidades tenebrosas de este mundo, su alma goza al salir del cuerpo de una blancura semejante.” |

| 7 | This matter can be amplified by turning to Transitus Mariae, texts that include the oral traditions of the 2nd and 3rd centuries, which repeat the luminosity and aromas at the moment of the Dormition. |

| 8 | The litanies were extended or reduced depending on their uses. This is why Mary Magdalene varies her position: she appears among the apostles, the saints or the virgins. This does not make it any less important that in some forms of the litanies she may appear presiding over a group of virgins. |

| 9 | “El Señor hizo a María Magdalena inmensos beneficios y distinguióla con señaladísimas pruebas de predilección (…); honróla con su confianza y amistad; […] la trató constantemente con comprensión y dulzura […] por amor a ella resucitó a su hermano Lázaro […] fue la primera a quien Jesús resucitado se apareció y la encargada por El de comunicar su resurrección a los demás, convirtiéndose de este modo en apóstola de los apóstoles.” |

| 10 | Translation by Esponera Cerdán (2002). |

| 11 | Translation by Forcada Comins. There is no date in the website of reference; I have also indicated this in the final bibliography. |

| 12 | These and other texts are part of the Querella de les Dones, in which female characters were an important focus of discussion (See Piera 2006; Criado 2013; Cortijo 2014). |

| 13 | “Magdalena: recoman-vos la mia mare així com la pus cara cosa que en aquets món lleixe: servireu a mi. Amau-la e reveriu-la: en lloc meu la lleixe per consolació de tots vosaltres. No us parteixcau de sa senyoria e estau a consell e obediencia sua Ella será mare e maestressa vostra. […] Magdalena, per confort de la vostra aspra e fort penitencia, seran-vos donades consolacions inestimables […]. E, finit lo terme de la vostra vida, io vendré per vós e us portaré a la Glòria mia”. |

| 14 | Saxl, interested in the life in the images, its processes of lethargy and rebirth, as well as the variety and continuity of the images, also introduced the idea of their magnetic power; in other words, how some images can be subject to contamination by others, thereby giving rise to migrations of certain visual characteristics and also of content from some images to others. In fact, this is precisely what has been dealt with throughout this study. |

References

- Antunes, Joana. 2014. The Late-Medieval Mary Magdalene: Sacredness, Otherness and Wildness. In Mary Magdalene in Medieval Culture: Conflicted Roles. Edited by Peter Loewen and Robin Waugh. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 116–39. [Google Scholar]

- Auberger, Jean-Baptiste, François Tricard, Gérard Billon, Isabelle Chareire, Jean-Louis Déclais, Jean-Noël Guinot, Joseph Beaude, Michel Berder, and Régis Burnet. 2008. Figuras de María Magdalena (Figures of Mary Magdalene). Estella: Verbo Divino. [Google Scholar]

- Barasch, Moshe. 2005. The Departing Soul. The Long Life of a Medieval Creation. Artibus et Historiae: An Art Anthology 52: 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baschet, Jérôme. 2016. Corps Et âmes. Une Histoire de la Personne au Moyen Âge. Paris: Flammarion (Ebook). [Google Scholar]

- Bernabé, Carmen. 1994. María Magdalena. Tradiciones en el Cristianismo Primitivo. Mary Magdalene. Traditions in Early Christianity. Estella: Verbo Divino. [Google Scholar]

- Bialostocki, Jan. 1972. Estilo e Iconografía. Contribución a una Ciencia de las Artes. Style and Iconography. Contribution to a Science of the Arts. Barcelona: Barral Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Collet, Olivier, and Sylviane Messerli. 2008. Vies Médiévales de Marie-Madeleine. Medieval Lifes of Mary Magdalene. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés, Marcos. 2010. El ‘Flos Sanctorum con sus Etimologías’. The ‘Flos Sanctorum’ and Its Etymologies. Edición y Estudio. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad de Oviedo, Oviedo, España. Available online: http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra/el-flos-sanctorum-con-sus-ethimologias-edicion-y-estudio/ (accessed on 21 February 2021).

- Cortijo, Antonio. 2014. Amores humanos, amores divinos. La Vita Christi de sor Isabel de Villena. The Vita Christi of sor Isabel de Villena. SCRIPTA, Revista Internacional de Literatura i Cultura Medieval i Moderna 4: 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Criado, Miryam. 2013. La Vita Christi de Sor Isabel de Villena y la teología feminista contemporánea. The Vita Christi of Sor Isabel de Villena and conteporary feminist theology. Lemir 17: 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- De Boer, Esther A. 1997. Mary Magdalene. Beyond the Myth. London: SCM Press Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- de Luna, Álvaro. 2009. Libro de las Virtuosas e Claras Mugeres. Book of Good and Virtuous Women. Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- de Villena, Isabel. 1987. Vita Christi. Barcelona: Edicions de les Dones. [Google Scholar]

- Disalvo, Santiago. 2010. El planctus de la Virgen en la Península Ibérica, desde el Quis dabit hasta las Cantigas de Santa María [En línea]. The planctus of the Virgin in the Iberian Peninsula, from tthe Quis dabit to the Cantigas of Santa Maria [Online]. IX Congreso Argentino de Hispanistas, 27 al 30 de abril de 2010 La Plata. El Hispanismo ante el Bicentenario. Available online: http://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/trab_eventos/ev.1065/ev.1065.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Eiximenis, Francesc. 1403. De Vita Christi. Valencia: Biblioteca Universitaria de Valencia. [Google Scholar]

- Esponera Cerdán, Alfonso. 2002. Sermonario de san Vicente Ferrer del Real Colegio-Seminario de Corpus Christi de Valencia. Sermonary of Saint Vicente Ferrer of the Royal College-Seminary of Corpus Christ of Valencia. Available online: https://www.juntacentralvicentina.org/index.php/antologia-de-textos/17-de-un-sermon-en-la-fiesta-de-santa-maria-magdalena (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Fedele, Anna. 2012. Looking for Mary Magdalene. Alternative Pilgrimage and Ritual Creativity at Catholic Shrines in France. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreiro, Alberto. 2010. St. Vicent Ferrer’s Catalan Sermon on Mary Magdalene. Anuario de Estudios Medievales 40/1: 415–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ferrarii, Sancti Vicenti. 1695. De un Sermón en la Fiesta de la Asunción de la Virgen María. About a Sermon on the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary. In Opera Omnia. Translated by Vicente Forcada Comins. Rocaberti: Valencia, vol. III. [Google Scholar]

- Foskolou, Vassiliki A. 2011. Mary Magdalene between East and West: Cult and Image, Relics and Politics in the Late Thirteenth-Century Eastern Mediterranean. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 65: 271–96. [Google Scholar]

- Giudice, Hernánd. 2012. Casta Meretrix. Acerca de la traducción y aplicación eclesiológica frecuente de una expresión patrística. Casta Meretrix. About the Frequent Ecclesiological Translation of a Patristic Expression. Revista de Teología XLIX: 111–23. [Google Scholar]

- Haskins, Susan. 1996. María Magdalena. Mito y Metáfora. Mary Magdalene: Myth and Metaphor. Barcelona: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, Katherine L. 2000. Like a Virgin: The Meaning of the Magdalen for Female Penitents of Later Medieval Italy. Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 45: 131–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, Katherine L. 2001. The Making of the Magdalen: Preaching and Popular Devotion in the Later Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Juan-Mompó, Joaquim. 1999. ‘O, dona ja n dona’. La ‘Història de la Gloriosa Santa Magdalena’ de Joan Roís de Corella. Fonts i originalitats. The ‘History of the Glorious Saint Magdalene’ by Joan Roís de Corella. Sources and Originalities. In Homenatge a Arthur Terry. Edited by Josep Massot i Muntaner. Barcelona: Abadia de Montserrat, vol. 3, pp. 115–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ketter, Peter. 2006. The Magdalene Question. Hartford: Catholic Authors Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kinch, Ashby. 2013. Imago Mortis: Mediating Images of Death in Late Medieval Culture. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Lefèvre D’Ètaples, Jacques. 1519. De Tribus et Unica Magdalena. Disceptatio Secunda. Of the Three and only Magdalen. The Second Argument. Paris: Ex officine Hnrici Stephani. [Google Scholar]

- Macías, Fray José. 2001. La Leyenda Dorada. The Golden Legend. Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Maisch, Ingrid. 1998. Between Contempt and Veneration… Mary Magdalene. The Image of a Woman through the Centuries. Collegeville: The Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maneikis Kniazzeh, Charlotte S., Edward J. Neugaard, and Joan Colomines. 1977. Vides de Sants Rosselloneses. Barcelona: Fundació Salvador Vives Casajuana. [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis, Nicole M. 2012. Draw Us after Thee: Daily Indulgenced Devotions for Catholics. Bloomington: iUniverse, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Molina i Figueras, Joan. 1999. Arte, Devoción y Poder en la Pintura Tardogótica Catalana. Art, Devotion and Power in Catalan Late Gothic Painting. Murcia: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad. [Google Scholar]

- Monzón Pertejo, Elena. 2020. La posesión demoníaca como protesta inconsciente de género: Los siete demonios de María Magdalena en la teología feminista y la cultura (audio)visual. Demon Posession as an Unconcious Gender Protest: The Seven Demons of Mary Magdalene in Feminist Theology and (audio)visual Culture. In Blame it on the Gender: Identities and Transgressions in Antiquity. Edited by de la Escosura Balbás, Maria Cristina, Elena Duce Pastor and Patricia González Gutiérrez. London: BAR Publishing, pp. 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Mycoff, David. 1989. The Life of Saint Mary Magdalen and of her Sister Saint Martha. A Medieval Biography. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, Vibeke. 2012. ‘Woman, Why Weepest Thou?’ Mary Magdalene, the Virgin Mary and the Transformative Power of Holy Tears in Late Medieval Devotional Painting. In Mary Magdalene. Iconographic Studies from the Middle Ages to the Baroque. Edited by Michelle A. Erhardt and Amy M. Morris. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 249–66. [Google Scholar]

- Piera, Montserrat. 2006. Mary Magdalene’s Iconographical Redemption in Isabel de Villena’s Vita Christi and the Speculum Animae. Catalan Review 20: 313–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Mathieu, Elisabhet. 1997. Marie-Madeleine dans la littérature du Moyen Age. Mary Magdalene in the Literature of the Middle Ages. Paris: Editions Beauchesne. [Google Scholar]

- Reau, Louis. 2000. Iconografía del arte Cristiano. Iconografía de la Biblia. Nuevo Testamento. Iconography of the Christian Art. Iconography of the Bible. New Testament. Barcelona: Ediciones del Serbal. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, Carla. 1994. Mary Magdalene and Many Others. Women Who Followed Jesus. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Santos Otero, Aurelio, trans. 2001. Los Evangelios Apócrifos. The Apocryphal Gospels. Madrid: Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos. [Google Scholar]

- Saxer, Víctor. 1958. Les saintes Marie Madeleine et Marie de Béthanie dans la traditions liturgique et homilétique orientale. The Saints Mary Magdalene and Mary of Bethany in the Liturgical and Homiletical Traditions of the East. Revue des Sciences Religieuses 32: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxer, Víctor. 1959. Le Culte de Marie Madeleine en Occident des Origines à la fin du Moyen âge. The Cult of Mary Magdalene from its Origins to the End of the Middle Ages. París: Librairie Clavreuil. [Google Scholar]

- Saxl, Fritz. 1989. La Vida de las Imágenes. Estudios Iconográficos Sobre el arte Occidental. The Life of Images. Iconographic Studies on Western Art. Madrid: Alianza. [Google Scholar]

- Schaberg, Jane. 2008. La Resurrección de María Magdalena. Leyendas, Apócrifos y Testamento Cristiano. The Resurrection of Mary Magdalene: Legends, Apocrypha and the Christian Testament. Estella: Verbo Divino. [Google Scholar]

- Schaus, Margaret, ed. 2006. Women and Gender in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schüssler Fiorenza, Elisabeth. 1975. Mary Magdalene: Apostle to the Apostles. UTS Journal 22: 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Toldrà i Vilardell, Albert. 2019. ‘Mes filles!’ La dona als sermons de sant Vicent Ferrer. ‘Mes filles!’ The woman in Saint Vicent’s sermons. Revista Valenciana de Filologia 3: 434–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannucci, Viviana. 2012. Maria Maddalena. Storia e Iconografia nel Medioevo dal III al XIV Secolo. Mary Magdalene. History and Iconography in the Middle Ages from III to XIV Century. Roma: Gangemi Editore. H. [Google Scholar]

- Viera, David J. 1991. Vincent Ferrer’s Sermon on Mary Magdalen: A Technique for Hagiographic Sermons. Hispanofilia 101: 61–66. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monzón Pertejo, E. The Transit of Mary Magdalene’s Soul in Catalan Artistic Production in the 15th Century. Religions 2021, 12, 1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111009

Monzón Pertejo E. The Transit of Mary Magdalene’s Soul in Catalan Artistic Production in the 15th Century. Religions. 2021; 12(11):1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111009

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonzón Pertejo, Elena. 2021. "The Transit of Mary Magdalene’s Soul in Catalan Artistic Production in the 15th Century" Religions 12, no. 11: 1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111009

APA StyleMonzón Pertejo, E. (2021). The Transit of Mary Magdalene’s Soul in Catalan Artistic Production in the 15th Century. Religions, 12(11), 1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111009