Abstract

The problem of adequate quantitative analysis of anthropogenic film pollution of water areas according to synthetic aperture radar (SAR) satellite imagery is addressed here. A quantitative analysis of anthropogenic film pollution (AFP) in the studied coastal water areas of the north sector of the Black Sea and Avacha Gulf has been conducted. The analysis utilized a method that involved the statistical processing of data related to AFP identified within the cells of a regular spatial grid. Time series of Sentinel-1 SAR satellite imagery were used as initial data. Spatiotemporal distributions of the proposed quantitative criterion (eAFP, ppm) have been calculated and analyzed. This criterion characterizes the intensity of AFP impact within the selected regions of marine waters based on measuring the relative frequency of an AFP event. Among them, the area of the emergency fuel oil spill that occurred in 2024–2025 near the Kerch Strait was investigated (eAFP values near the wreckage of tankers reached ~13,000 ppm), as well as the area of the emergency oil spill near the Novorossiysk terminal that occurred in 2021 (eAFP ≤ 6000 ppm). Accidents led to an approximately 3–6-fold increase in eAFP values against the background level of 0–2000 ppm. The spatiotemporal variability of eAFP across various water areas and under different conditions has been demonstrated and discussed.

1. Introduction

Our time is characterized by a significant increase in the anthropogenic load on marine waters. This is due, among other things, to the increase in the number of offshore drilling rigs, the growth of the network of coastal oil terminals, the intensive growth of the volume of marine oil transportation operations, etc. [1]. Discharges of polluted waters from ships, including ballast, bilge, and wash waters, also significantly contribute to the anthropogenic load [1,2,3]. Moreover, domestic and industrial wastewater makes a large contribution to the pollution of coastal marine waters [4].

A key manifestation of such negative impacts on marine water areas, including coastal ones, is anthropogenic film pollution (AFP), which occurs when pollutants are released into the marine environment from the above-described and other sources. One of the promising areas used to detect and monitor such AFP over vast marine areas is the use of satellite images, including radar ones [1,5,6,7], as well as various ground-based sensors [8]. For a comprehensive analysis of such pollution, geoinformation systems (GIS) are used [4,9,10]. Mathematical modeling methods are also used to solve such problems [11,12].

Detection of AFP in satellite synthetic aperture radar (SAR) images is a complex task and is performed taking into account the characteristics of the marine environment, the physical features of the phenomena under study [10,13,14], and the specificity of the remote sensing of the sea surface in the radio range of the electromagnetic spectrum [1,3,13]. A large number of works are devoted to the issues of identifying film pollution based on radar satellite data [3,15,16], as well as determining their types and detecting their sources (e.g., [10,17,18] and other). However, a significant remaining challenge is the systematization and analysis of fragmented outcomes of long-term satellite monitoring of the AFP to obtain quantitative estimates characterizing the intensity of pollution in marine areas. Our article focuses primarily on examining this problem.

Many works (for example, [19,20,21], etc.) demonstrate that the conducted studies are often limited to the creation of generalized maps of detected AFPs and their comparison with a situational map using GIS. This approach allowed the analysis of the parameters and probable genesis of AFP but did not provide the basis for a reasoned classification of studied water area regions according to the level of pollution. It is important to note that the number of pollution cases [22] or affected areas [23] detected using satellite data may not accurately represent the actual pollution exposure in water areas under study. This is due to the fact that hydrometeorological conditions and the satellite imagery coverage can vary significantly [24].

Obviously, the coverage of satellite imagery varies due to the specific orbital configuration and imaging programs of the satellite constellations used. Moreover, the number of images taken, even for nearby areas of water, over a monitoring period (e.g., a year) can vary severalfold [25].

Spatial and temporal dynamics of external factors, including near-surface wind speeds [1,3], current fields, internal waves [26], etc., significantly affect the AFP detection using SAR satellite data [1,3,27]. Combined with variability in survey coverage density, this leads to an uneven spatiotemporal distribution of the number of observations suitable for AFP detection.

Thus, conditions for AFP detection vary across different locations and times within the surveyed waters. Under such circumstances, it is particularly challenging to perform a rigorous quantitative comparison of monitoring results obtained for different water areas.

This paper describes and explores an approach to recording and quantitatively analyzing the spatiotemporal dynamics of AFP based on the processing of long-term time series of SAR satellite data, taking into account variability in satellite observation coverage and wind speed. A quantitative comparison of the results of radar satellite monitoring of AFP conducted in the north sector of the Black Sea and Avacha Gulf is provided.

2. Materials and Methods

In [24], known approaches to the quantitative analysis of AFP detection results obtained during long-term satellite monitoring of marine areas were considered. Based on the analysis of [25,28,29,30] and other works, it was shown that, when generalizing the results of long-term satellite monitoring of different types of sea surface pollution, it is expedient to take into account the spatiotemporal variability in the number of observations. It is also advisable to correlate the obtained statistical estimates of AFPs with the areas of the studied water regions [9,31]. A promising approach to solving this problem is to divide large study areas into equal-area cells according to a regular spatial grid and obtain estimates for multiple such cells. This makes it possible to classify analyzed sections of the study areas by their degree of pollution exposure, as well as to quantitatively track pollution dynamics in each cell [29].

Based on the above, this study utilized a methodology to quantitative analyze the accumulated area of registered AFP, correlated with accumulated area of used SAR data. In general, we aimed to obtain spatial distributions of the estimation of the relative frequency of AFP event occurrence. To realize this idea, an appropriate computational procedure was proposed and implemented, involving the processing of each pixel of the processed data within larger cells of a regular spatial grid.

We propose to calculate cyclically the annual maps of the eAFP value, notionally termed the AFP exposure criterion (eAFP). The eAFP value is determined for each cell as the ratio of the summarized area of recorded AFPs to the summarized area of SAR coverage under acceptable conditions. It is of principle that we aim to exclude from consideration obviously unsuitable SAR imagery fragments, which for physical reasons make AFP detection impossible even in the case of their presence.

The eAFP value for each cell essentially represents the measured value of the relative frequency of its pollution events. As is known [32,33], with a sufficiently large number of tests (in this case, SAR surveys under acceptable conditions), the measured frequency will tend to an objective estimate of the probability of a pollution event. To ensure a large number of tests to obtain valid assessments, we use relatively long periods for eAFP calculation, typically a year, or half a year in the case of an emergency.

In [25] it was shown, that the eAFP value for an arbitrary-sized area can be calculated as follows:

where Y is the number of satellite constellations (SC) involved. Satellite constellation means a series of the same-type satellites, e.g., Sentinel-1A and Sentinel-1B, etc.;

j is the counting number of SC (j = 1, …, Y);

is the pixel area for satellites of j-th SC;

X is the number of surveys for the selected SC over the analyzed period;

i = 1, …, X is the counting number of the survey;

is the number of pixels corresponding to the AFP registered as a result of interpreting the i-th survey performed by the j-th SC;

is the number of all pixels for which the hydrometeorological conditions (corresponding to the pixel coordinates) during the i-th survey performed by the j-th SC and allowed the AFP detection.

The numerator and the denominator in Equation (2) correspond to the total area of AFP observed in the analyzed marine area using all involved SCs and the total valid satellite coverage area, respectively.

In this effort, a single SAR SC (Sentinel-1A/B/C satellites) was used. The key parameters of the Sentinel-1 SAR system are following (https://sentiwiki.copernicus.eu/web/s1-mission (accessed on 23 December 2025)):

- -

- Operating frequency/wavelength—C-band, 5.405 GHz (corresponding to a wavelength of 5.55 cm);

- -

- Polarization modes—HH+HV, VV+VH, VV, HH;

- -

- Acquisition modes and approximate spatial resolution—Strip Map (~5 m), Interferometric Wide Swath (~10 m), Extra-Wide Swath (~30 m), Wave (5 m);

- -

- Incidence angle range (approximate)—from ~18° to 47° (depending on acquisition mode).

It can be noted that a significant part of the scientific community’s experience in detecting and classifying various types of sea surface film pollution by satellite radar methods has been accumulated using C-band SAR instruments (including experience in processing data from previously operated satellites such as ERS, ENVISAT, and others) [1,3,14]. In our work, we use the most common type of Sentinel-1 SAR imagery of coastal water areas today—Interferometric Wide Swath mode, VV+VH polarization with a resolution of ~10 m, 250 km swath. Given the typical AFP spatial scale, the linear dimensions of which usually range from tens and hundreds of meters to several kilometers, such data provides an optimal balance between detail and spatial coverage.

Considering this:

Considering the constancy of the value, this term in Equation (1) can be reduced. Thus, the can be calculated as a special case of (1) as follows:

The approach consists of obtaining the spatial distribution of the value, calculated using Equation (2) in the cells of a regular spatial grid with a selected size during the selected time intervals. This was accomplished by processing time series of radar satellite images, followed by accumulation of the results into a systematic spatiotemporal array [25]. It should also be noted that potentially (see Equation (1)) the approach is applicable for processing multi-source heterogeneous data (e.g., other remote sensing satellites and unmanned aerial vehicles).

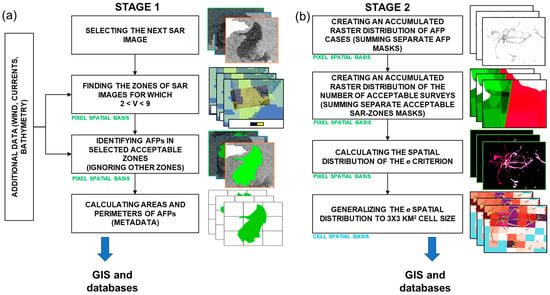

Data processing for each selected AFP monitoring period (in most cases, a year) for each processed region of coastal waters (see Section 3) was carried out in two main stages, as shown in the structural flow chart shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A structural flowchart of data processing: (a) stage 1—processing SAR images; (b) stage 2—summarizing the results of SAR image processing for the analyzed period.

As can be seen from this flowchart (see Figure 1), at stage 1, the following steps were performed:

- -

- Selecting the next SAR image (Sentinel-1A/B/C, Interferometric Wide Swath mode, ~10 m pixel size) for the analyzed period;

- -

- Determining the areas of SAR images for which the wind speed (V) satisfied the conditions:2 m/s < V < 9 m/sAs is known, at low speeds of near-surface wind (V < 2 m/s), the generation of gravitational–capillary waves stops, which plays a key role in the formation of the reflected SAR signal. However, AFPs that mainly reveal themselves due to the modulation of such waves become invisible. On the other hand, when the wind speed is too high (V > 9 m/s), the film formations on the sea surface are broken and the pollution takes on a different physical form, which is also inaccessible for detection using SAR [3,13,14]. Wind conditions were monitored using NCEP data, and relevant radar image masks were created.

- -

- Interactive detection of AFP by the SAR imagery analyst team for regions of each radar image where Equation (3) was met, taking into account the AFP SAR interpretation methodology [3,7,14] as well as data on bathymetry, wind conditions, and currents;

- -

- Calculating AFP metadata (areas and perimeters).

Stage 1 of data processing (see Figure 1a) was conducted using JavaScript (ECMAScript 5.1) software scripts developed at the AEROCOSMOS Research Institute and based on the Google Earth Engine (GEE) cloud platform [34].

Stage 2 of data processing (see Figure 1b) included summarizing the SAR image processing results for the selected period according to the proposed approach. The following steps were performed:

- -

- Summarizing the raster masks of all AFP detected in the processed area over the selected time period (typically a year; see Table 1);

- -

- Summarizing the raster masks of all valid fragments of SAR scenes, which satisfied Equation (3);

- -

- Calculating spatial distribution of the eAFP value using Equation (2) in full resolution mode (10 m pixel size) using the band-math concept [35];

- -

- Generalizing the eAFP map by calculating its mean values in 3-km-size cells [25,29].

Reducing the processed raster masks to a single coordinate-pixel basis and their summing up, as well as the calculation of spatial distributions of eAFP criterion and their generalization, were performed using a software module developed at the AEROCOSMOS Research Institute, operating in the ENVI+IDL 5.2 software environment.

The results from the 1 and 2 data processing stages according to Figure 1 were accumulated in a specialized GIS and stored in the database.

The main output data from the above-described approach implementation were:

- -

- AFP vector outlines and their metadata, as well as raster AFP masks;

- -

- Raster spatial distributions of the annual number of valid SAR surveys;

- -

- Raster spatial distributions.

For the convenience of operating with typically relatively small levels of the eAFP criterion, we present it in millionths and denote it as (ppm) by multiplying the actual values obtained by Equation (2) by 106. As will be shown below, eAFP values in a 3 km spatial cell can reach a level of about 0.01 under extreme pollution (we denote this as 10,000 ppm). Typical eAFP values averaged over a large area of coastal waters are usually on the order of 0.0001 level (we denote this as 100 ppm) [25].

The final information products were presented as color-coded distribution maps of the proposed AFP exposure criterion for the selected period. At the next step, these products were analyzed using GIS functionality.

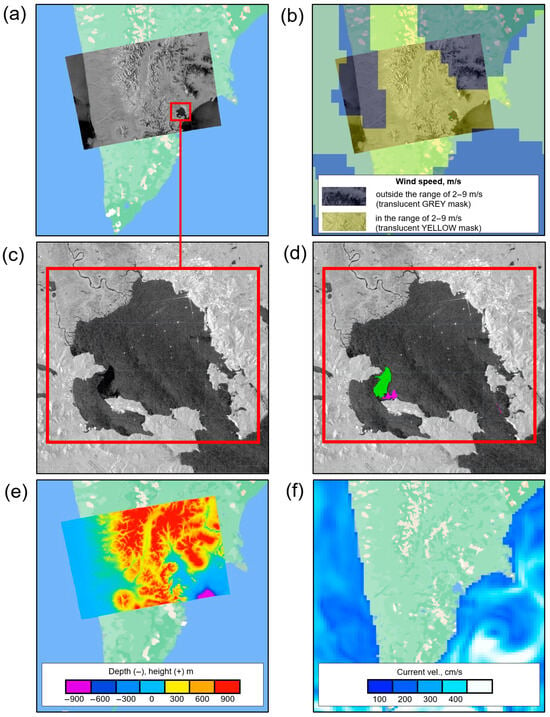

Figure 2 illustrates in more detail the specifics of working processes of operators when interactively identifying AFP using the example of processing a single SAR image for one of the study areas (Avacha Gulf; see Table 1). It is important to note that there are two main approaches for identifying AFP using satellite SAR imagery, namely automated (currently usually based on neural network algorithms [15]) and interactive (which involves visual analysis of SAR imagery [10]). Without discussing the advantages and disadvantages of each of them (this deserves a separate article), let us clarify that in our case we tend to trust the interactive approach more. During the interactive analysis, each operator identifies AFP in the SAR image using their knowledge and experience, relying primarily on shape, size, structure, texture, proximity to potential sources and other decoding features. These features make it possible, among other things, to distinguish AFP from other types of film formations, primarily biogenic films. In addition, the field of currents, bathymetry conditions, and areas of wind shadows are subject to analysis. These factors can lead to the formation of objects similar to AFP, but not them (the so-called look-alike objects that must be eliminated). Some basics of interactive AFP decryption using satellite SAR data are described in [3,7,14].

Figure 2.

An example of an operator’s workflow for AFP identification (Avacha Gulf test site): (a) original SAR image (2 January 2024) superimposed on the map; (b) translucent mask of wind conditions superimposed on (a); (c) enlarged SAR image fragment with detected AFP; (d) vector polygons (designated as green and purple areas) of the identified AFP superimposed on (c); (e) depth/elevation map within the SAR image boundaries; (f)—surface current velocity map.

Figure 2a presents the original radar image (2 January 2024), overlaid on a map of the study area (Avacha Gulf).

Figure 2b shows a translucent wind (NCEP) mask overlaid on the original radar image. This mask allowed the operators to identify areas with suitable and unsuitable conditions for detecting AFP.

Figure 2c shows a zoomed-in fragment of the radar image of identified AFP examples. Figure 2d illustrates vector polygons of the identified AFP, superimposed on the zoomed-in radar image fragment.

Figure 2e shows a depth/elevation map within the radar image boundaries, and Figure 2f shows a surface current velocity map. These maps were combined with the radar image, allowing for consideration of bottom topography, as well as potential drift conditions and the dynamics of the identified AFP. The depth/elevation maps and the surface current velocity maps increased the reliability of radar image interpretation.

During our research, three operators-interpreters were involved in processing the satellite data. Some aspects of the organization of a technique for interactive collaborative detection of AFP in SAR imagery by several operators enabling consensus evaluations are highlighted, for example, in [29]. In our case, the operators detected potentially interesting formations in satellite SAR imagery independently of each other. At the same time, the final decision on whether the identified objects belong to the AFP class was made through a periodical collegial discussion based on the acceptance of the majority opinion.

3. Studied Water Area Regions

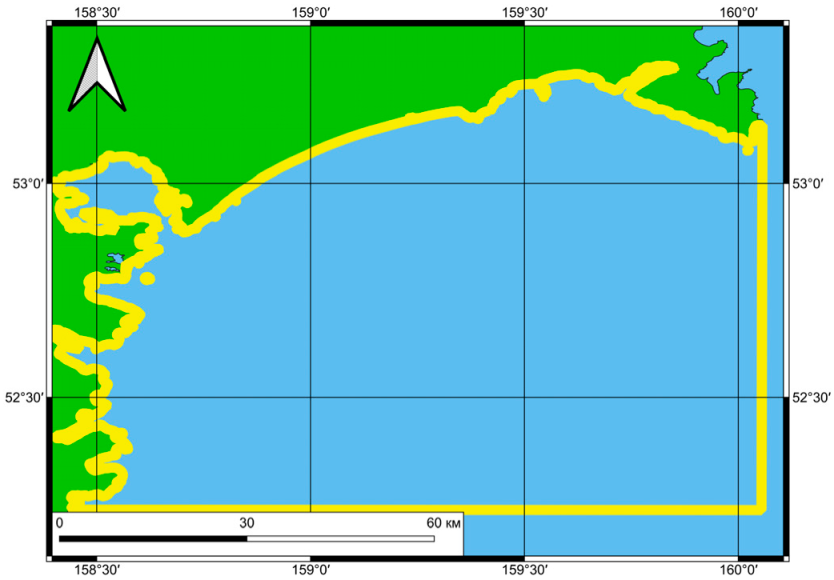

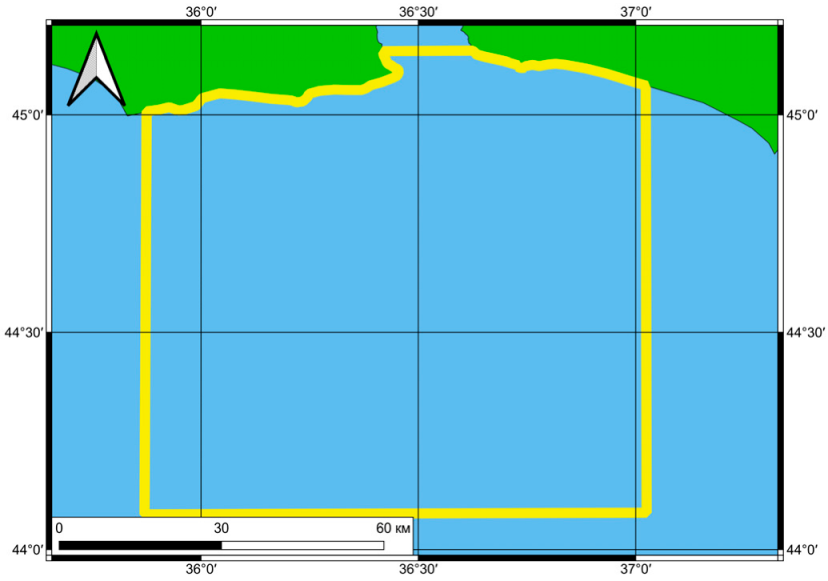

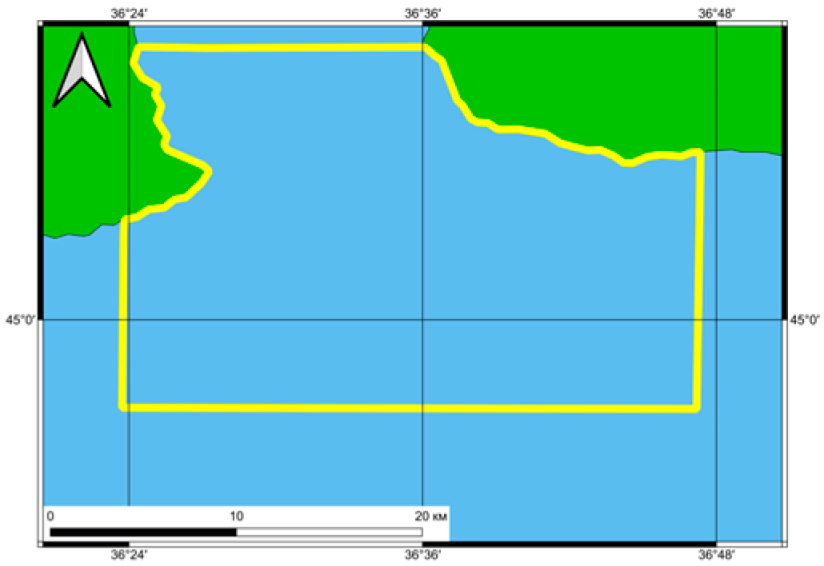

The list of sea coastal water areas under study, their areas, monitoring periods and some details is given in Table 1.

As Table 1 shows, the research involved the results of satellite monitoring of 5 sites, two of which are quite extensive (~10.2 thousand km2 area), and the remaining 3 are smaller (less than 1 thousand km2 area).

Site 1, located off the Kamchatka Peninsula, covers Avacha Gulf (including Avacha Bay) with an area of ~10.2 thousand km2. It was monitored from 2014 to 2024 (11 years). The monitoring results from 2014 to 2023 were summarized and analyzed in [24]. In this study, new AFP satellite monitoring results were obtained and analyzed for this site (for 12 months of 2024). Those results were compared with the data obtained for the period of 2014–2023 and with the monitoring results for Site 2 (see Table 1). Site 1 was characterized by rather intense anthropogenic impacts due to shipping, as well as domestic and household wastewater [24].

Site 2 (northern Black Sea) was located south of the Kerch Strait. The boundaries of Site 2 were selected based on three criteria:

- -

- Available data of previously conducted satellite monitoring of film pollution (see [25]);

- -

- Intensive shipping traffic;

- -

- An area of ~10.2 thousand km2 (to ensure full comparability with Site 1).

Given these conditions, the study of Site 2 was of interest for comparison with the results of Site 1. Both sites are adjacent to the coast and characterized by the presence of AFP sources but are located in widely separated seas.

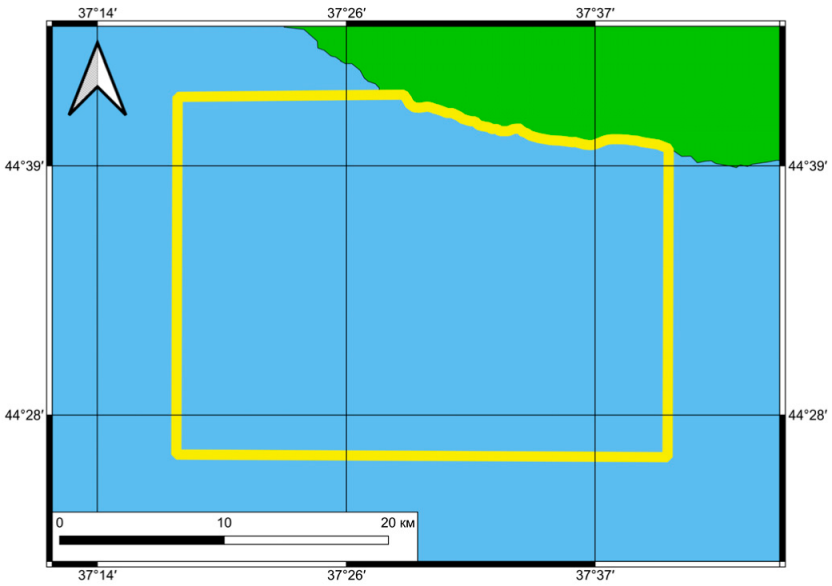

Site 3 (located near the Kerch Strait) had an area of ~0.8 thousand km2. The study of this site was operatively carried out for 6 months, from 15 December 2024 to 15 June 2025. Satellite monitoring focused on AFP resulting from the emergency wreck of the Volgoneft-212 and Volgoneft-239 tankers. These vessels were transporting a large quantity (almost 10 thousand tons) of M-100 fuel oil, a significant portion of which entered the marine environment [18,36,37]. Site 3 was studied using satellite methods earlier, during the monitoring in 2019, described in [25] using the developed quantitative approach. Considering this, it became possible to compare new monitoring results obtained for this local area after the tanker accident that occurred in 2024 with background characteristics obtained in 2019. Thus, in this study, the contribution of the consequences of a large-scale fuel oil spill to the overall pollution of the sea surface in this region was quantitatively assessed.

Site 4 (located in the Black Sea near Novorossiysk) had an area of ~0.6 thousand km2. This site was monitored throughout 2021. In August 2021, an incident related to an oil spill at the terminal of the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC) occurred in this site (http://www.aerocosmos.info/news/detail.php?ELEMENT_ID=7196 (accessed on 23 December 2025)). As part of this article, a comparative analysis of AFP data for this site was performed with the monitoring results of other local sites in the Black Sea waters, which were obtained in 2019 (Sites 3 and 5, shown in Table 1).

Site 5 (located in the Black Sea near Sevastopol) had an area of ~0.9 thousand km2. It was monitored from 1 January 2019, to 31 December 2019 [25]. This area was characterized by quite intensive background pollution due to the presence of a natural source of film pollution—hydrocarbon seep [6]. Therefore, within the framework of this study, Site 5 was of interest for assessing possible background levels of natural pollution and comparing them with pollution in local sites 3 and 4.

Table 1.

Coastal water sites under study, their areas, monitoring periods, and study details.

Table 1.

Coastal water sites under study, their areas, monitoring periods, and study details.

| No. | Site Name, Geographic Location, Map, and Area | Monitoring Time Frame | Study Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Avacha Gulf (including Avacha Bay). The Kamchatka Peninsula  ~10.2 thous. km2 | 2014–2024, 11 years | The site is characterized by intense anthropogenic impacts. A comprehensive retrospective of AFP satellite monitoring results (11 years) is available for this site. This study is of interest for quantitative analysis of the long-term dynamics of annual AFP exposure criteria. |

| 2 | A site in the northern part of the Black Sea, equivalent in area to the Site 1 ~10.2 thous. km2 | 2019, 12 months | The site is located in the Black Sea south of the Kerch Strait in a heavy- traffic zone. The boundaries of Site 2 were chosen so that its area matched that of Site 1. The study of Site 2 is of interest, among others, for its comparison with Site 1. |

| 3 | Local emergency site near the Kerch Strait ~0.8 thous. km2 | 15 December 2024–15 June 2025, 6 months (Emergency period) 2019, 12 months (Background period) | The local site where the tanker accident occurred in December 2024 [18]. The study of this area is of interest for quantitative assessment of the contribution of the fuel oil spill to marine pollution. |

| 4 | Local emergency site of the Black Sea near Novorossiysk ~0.6 thous. km2 | 2021, 12 months | The local site where the accident occurred at the CPC oil terminal in 2021. (http://www.aerocosmos.info/news/detail.php?ELEMENT_ID=7196 (accessed on 23 December 2025)). The study of the site is of interest for the quantitative assessment of oil sea pollution after an accident. |

| 5 | Local background site of the Black Sea near Sevastopol ~0.9 thous. km2 | 2019, 12 months | The local site subjected to relatively intense background film pollution, including that associated with the presence of a natural oil leakage. Involving this area in research is advisable to assess possible background levels of natural film pollution. |

4. Results and Analysis

This section firstly presents and analyzes the following actual results obtained:

- -

- AFP detection results based on SAR satellite data in Avacha Gulf (Site 1) in 2024;

- -

- AFP detection results in the area of the tanker accident, which occurred on local emergency Site 3 near the Kerch Strait in December 2024.

These results were then compared with previously obtained AFP satellite monitoring results in various coastal waters, listed in Table 1. The following were performed:

- -

- A comparative analysis of the AFP monitoring results conducted in Avacha Gulf (Site 1) in 2024 against previously obtained monitoring results (from 2014 to 2023) for this site, as well as against Site 2 in the northern part of the Black Sea, equivalent in area to Site 1;

- -

- A comparative analysis of the AFP monitoring results in the Site 3 of the tanker accident near the Kerch Strait against monitoring results in other local areas of the Black Sea (Site 4 and Site 5).

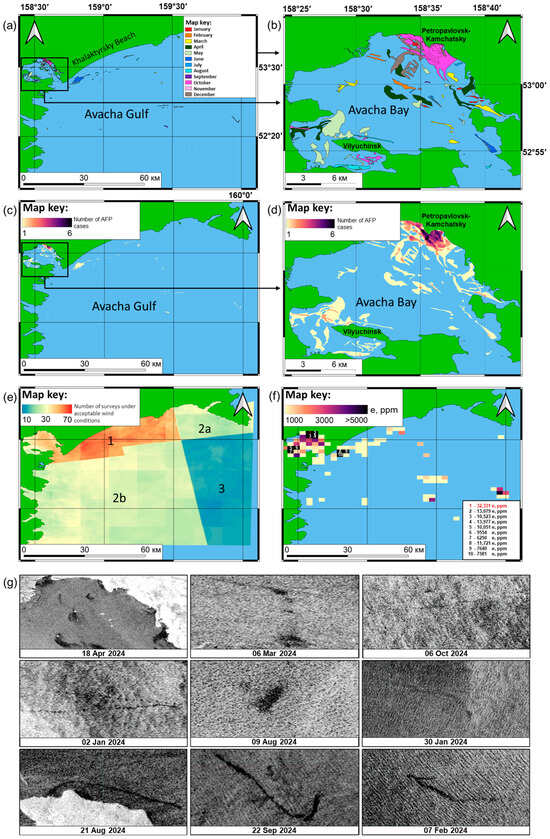

4.1. Detecting AFP in Avacha Gulf in 2024

The detection of AFP in Avacha Gulf (Site 1 in Table 1), was carried out using 148 SAR satellite images (Sentinel-1A, obtained from 1 January 2024, to 31 December 2024). Interpretation of the collected 148 images yielded 115 identified AFP cases. Thirty-six AFPs were located in the open part of Avacha Gulf, and seventy-nine in Avacha Bay. The total area of the detected AFP was approximately 84.1 km2.

Figure 3a shows an integrated map of AFP detected in Avacha Gulf in 2024. AFP detected in different months of the year are shown in different colors. Analysis of the map from Figure 3a shows that in the open part of Avacha Gulf, relatively strong pollution concentrations were observed along Khalaktyrsky Beach, while Avacha Bay was found to be the most exposed to AFP. Examples of SAR satellite imagery fragments with typical AFP manifestations in this study area in 2024 are shown in Figure 3g.

Figure 3.

Mapped AFP contours detected in 2024: (a) in Avacha Gulf and (b) in Avacha Bay; mapped number of AFP cases: (c) in Avacha Gulf and (d) in Avacha Bay; (e) mapped number of acceptable SAR surveys; (f) mapped eAFP criterion; (g) examples of SAR images with AFP manifestations.

Due to the large number of AFPs observed in Avacha Bay, a detailed integrated AFP map was created for it (see Figure 3b). Analysis of this map revealed that the majority of AFPs were located in the northeastern part of the bay and close to the city of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. Another cluster of pollution was located in the southwest near the city of Vilyuchinsk (see Figure 3b).

The maps shown in Figure 3c,d indicate that near the city of Vilyuchinsk, the number of AFP registered in 2024 in the several areas of the test site reached 2–3. While near the city of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, this parameter reached 5–6 AFP.

The map of the number of valid SAR surveys, shown in Figure 3e, reveals spatial variability in the density of survey coverage in the study area suitable for processing. On this map, one can identify four main areas with greatly different amounts of available SAR data under acceptable wind conditions (see ‘1’, ‘2a’, ‘2b’, ‘3’ marks in Figure 3e). The presence of these four areas is due to the peculiarities of the Sentinel-1 satellite constellation’s survey program, which is focused primarily on surveying coastal waters. Figure 3e demonstrates the feasibility of applying the developed quantitative approach to process the results of AFP monitoring, which enables the generation and analysis of the maps of AFP exposure criterion, taking into account variability in the density of observations.

The generalized AFP exposure map for the study area in 2024, shown in Figure 3f, was obtained on a 3 × 3 km2 grid using Equation (3). Analysis of this map revealed that a significant portion of Avacha Bay was subject to AFP (e values reaching 5000 ppm or more) in many cells both in the northeast and southwest of Avacha Bay, as well as in the northwestern part of Avacha Gulf. Extremely high AFP exposure values were registered specifically in Avacha Bay, where eAFP criterion reached a record level of over 32,000 ppm in one cell near the city of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky.

We can assume that such high eAFP values in Avacha Bay are because this part of the studied water area was exposed to both intensive shipping and the influx of domestic and industrial wastewater. Both of these factors lead to the formation of large quantities of AFP. As can be seen from Figure 3f, cell No. 1 with the aforementioned record level of eAFP criterion is located in close proximity to the city of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. This urban agglomeration is undoubtedly the most significant source of pollution in this water area. Thus, the results of the performed monitoring demonstrate, apparently, a realistic and adequate assessment.

Unlike Figure 3a, which shows a traditional AFP vector map, Figure 3f allows for a formal differentiation of sea surface cells based on their level of eAFP value. Furthermore, as mentioned above, this information product is correct for the perception of the actual situation of the spatiotemporal AFP distribution inherent in classical AFP maps (for example, as shown in Figure 3a or 3b), which is modulated with variability in the number of observations.

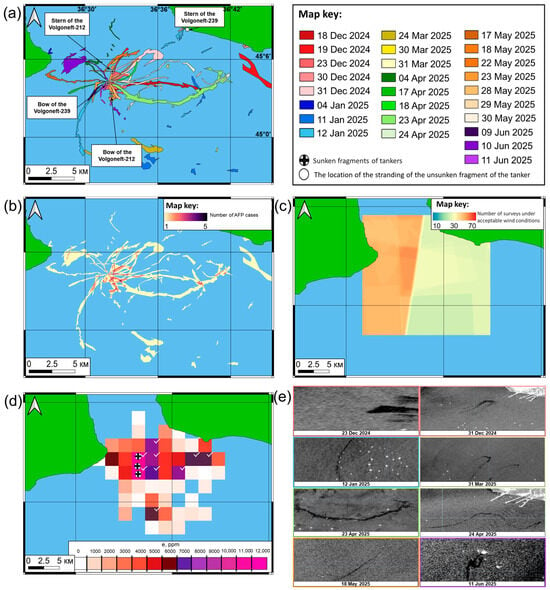

4.2. Results of AFP Detection in the Area of the Tanker Accident near the Kerch Strait

Identifying AFP resulting from the Volgoneft-212 and Volgoneft-239 tanker accidents that occurred in December 2024 [18] was conducted based on the processing of a series of 99 Sentinel-1A/C SAR satellite images acquired between 15 December 2024, and 15 June 2025.

The interpretation of the radar images yielded 73 slicks associated with AFP on the sea surface, primarily caused by the release of fuel oil into the aquatic environment following the tanker accidents. The total area of slicks associated with such AFP was ~94.9 km2.

Figure 4a presents an integrated map of pollution recorded in this water area from 15 December 2024, to 15 June 2025 (six months). To visualize the pollution dynamics, the integrated map uses color-coded polygons representing AFPs detected on different dates (see Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

Mapped: (a) AFP contours detected near the Kerch Strait (15 December 2024–15 June 2025), (b) number of AFP cases, (c) number of acceptable SAR surveys, (d) eAFP criterion; (e) examples of SAR images with AFP manifestations.

Analysis of the map shown in Figure 4a revealed that the largest number of AFPs recorded between 15 December 2024, and 15 June 2025, are located in the area where the sunken bow of the Volgoneft-239 tanker is located, as well as the stern and bow sections of the Volgoneft-212 tanker. Examples of SAR imagery fragments with typical AFPs detected are shown in Figure 4e.

The distribution map of the number of AFP cases, shown in Figure 4b, indicates that the number of overlapping (detected in the same fragment of the water area) AFP registered during the six-month monitoring period after the accident reached its maximum values (up to 4–5) in the immediate vicinity of the locations of the sunken fragments.

The valid SAR survey map, shown in Figure 4c, demonstrates the spatial variability of survey coverage density in the period from 15 December 2024, to 15 June 2025, in the study area. Two main areas can be identified on this map (see Figure 4c):

- -

- An orange area in the west of the study site, corresponding to zones with the highest number of surveys, the number of which could exceed ~60;

- -

- A yellow-green area in the east of the study site, corresponding to zones with a smaller number of surveys (approximately ~30).

An analysis of Figure 4c shows that in the studied area there was a sharp boundary separating a zone with a relatively high chance of detecting AFP (the western section, with over 60 SAR scenes captured over six months) from a zone with a relatively low chance of registering AFP (the eastern section, with ~30 scenes captured). The observed distribution of the number of surveys indicates the need to take into account the unevenness of survey coverage when analyzing AFP monitoring results, which is implemented in the proposed approach.

The resulting generalized map of the eAFP criterion near the Kerch Strait for the emergency period from 15 December 2024, to 15 June 2025, shown in Figure 4d, demonstrates the following. Relatively high AFP exposure values were observed over a significant part of the study area, reaching a level of eAFP~6000 ppm, which is a high level [25] for this region. The eAFP values in the range from 0 to 6000 ppm on the map shown in Figure 4d correspond to the pink-red colors of the regular grid cells. At the same time (see Figure 4d), some cells were characterized by extremely high levels of AFP exposure, exceeding the 6000 ppm level and reaching ~12,000 ppm (these cells are marked off with ticks in Figure 4d). Such cells correspond to blue-violet colors (see the map key in Figure 4d). The highest AFP exposure values (e > 12,000 ppm) were detected in the immediate vicinity of the sunken fragments of the Volgoneft-239 (bow section) and Volgoneft-212 (stern and bow sections, see circles with crosses in Figure 4d). This indicates that significant amounts of pollutants entered the water from those emergency objects.

The obtained results indicate that the accident significantly contributed to the pollution of the sea surface near the Kerch Strait. As a result, record levels of the measured marine surface AFP exposure index were registered for the Black Sea. This pollution is caused by the release of light fractions of fuel oil onto the sea surface. At the same time, it is clear that the accident’s contribution to the pollution of the seawater, seabed, and coastline is manifold higher [18,35] than the level of sea surface pollution estimated in this study. This is due to the fact that most of the fuel oil released into the marine environment is characterized by near-neutral buoyancy and is located not on the surface, but in the water column, on the seabed, and on the shore.

4.3. Comparative Analysis of the AFP Monitoring Results in Avacha Gulf with Previously Obtained Results

As mentioned above, we had previously studied the dynamics of eAFP values in Avacha Gulf for the 10-year period up to 2023. This study complements those previously obtained results and allows for a comparative analysis of the actual AFP monitoring results obtained in 2024.

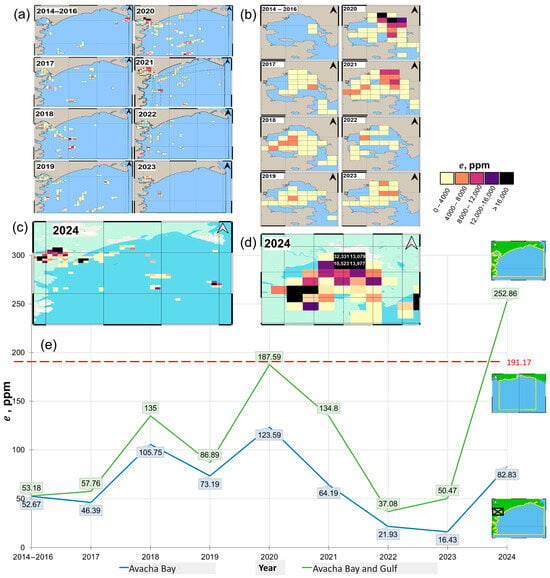

Figure 5 shows the interannual dynamics of eAFP values on this test site for the combined period from 2014 to 2024. The blue graph corresponds to the interannual mean eAFP calculated for the open part of Avacha Gulf (Avacha Bay is excluded), and the green graph corresponds to the entire study area of Avacha Gulf, including Avacha Bay. The red horizontal line shows the calculated AFP exposure reference level (~191 ppm) for Site 2 (see Table 1) in the Black Sea south of the Kerch Strait in a zone of intense shipping [25]. The boundaries of this reference site were selected such that its area was equal to the area of the studied Avacha Gulf (~10.2 thousand km2). This ensures the correct comparison of AFP exposure values for Sites 1 and 2.

Figure 5.

Variability of AFP exposure criterion in the Avacha Gulf (a,c) and in the Avacha Bay only (b,d) for the period from 2014 to 2024; The lines (e) represent the interannual mean eAFP calculated for the entire gulf (green) and for open waters excluding the bay (blue); The red line indicates the reference eAFP level from the Black Sea.

Figure 5a shows annual eAFP maps for the entire Avacha Gulf water area, while Figure 5b shows them zoomed in for Avacha Bay alone. The results for 2014–2016 were combined in Figure 5a,b,e due to low SAR data flow rate. Figure 5c,d show the AFP exposure maps obtained within our effort for 2024 (for the entire gulf on the left and for the bay alone on the right).

Figure 5a–d demonstrate that the obtained spatial distributions of the AFP exposure criterion show heterogeneity, complexity, and interannual variability. Moreover, in 2024, AFP exposure was very high, which is confirmed by the graph in Figure 5e. Notably, in 2020, the e-value in Avacha Gulf (187 ppm) almost reached the level of this indicator determined for the equivalent site of the Black Sea near the Kerch Strait (191 ppm). In addition, in 2024, eAFP in Avacha Gulf significantly exceeded this level and reached 253 ppm.

A comprehensive analysis of the maps and graphs from Figure 5 allows us to indicate the following features:

(1) In Avacha Gulf (including Avacha Bay) from 2014 to 2024, the interannual dynamics of eAFP was characterized by minima that appeared in 2014–2016, 2017, 2019, 2022 and 2023 (53, 58, 87, 37 and 50 ppm, respectively), as well as maxima in 2018, 2020, 2021 and 2024 (135, 188, 135 and 253 ppm, respectively).

The maximum AFP exposure values recorded in 2020 and 2024 could have been caused by accidental wastewater discharges as well as ship spills. For example, in 2020, the largest AFP was detected in the Avacha Bay (the area was ~11 km2). The largest AFP in the open part of the bay was recorded in 2024 near Khalaktyrsky Beach. The area of this AFP, calculated using GIS, was ~14 km2.

It is noteworthy that in 2024, a record high number of AFPs was recorded in Avacha Bay—79 cases (see Figure 3a–d), which led to a record high value of the eAFP criterion (253 ppm) and resulted in the presence of dark-colored cells in Figure 5d, corresponding to high and extreme levels of AFP exposure.

(2) The interannual dynamics of AFP exposure criterion in the open part of Avacha Gulf from 2014 to 2024 were characterized by minima in 2017, 2022, and 2023 (~46, 22, and 16 ppm, respectively) and maxima in 2018, 2020, and 2024 (~105, 124 (absolute maximum), and 83 ppm, respectively).

(3) A comparative analysis of the green and blue graphs in Figure 5e demonstrates that, despite the relatively small area of the bay (smaller than 5% of the test site area), this part of the water area makes a significant contribution to the AFP exposure levels for the entire Avacha Gulf.

Thus, using Avacha Gulf as an example, the feasibility of using the developed quantitative approach to process the results of long-term SAR satellite monitoring of AFP for the purposes of a substantiated comparative analysis of interannual AFP variability using a standardized eAFP criterion was demonstrated.

4.4. Comparison of AFP Monitoring Results in the Local Area of the Tanker Accident near the Kerch Strait and in Other Parts of the Black Sea Waters

Comparison of AFP monitoring results obtained in this study in the local area of tanker accidents near the Kerch Strait with the monitoring results for other parts of the Black Sea waters was performed. We used the previously obtained results of satellite monitoring of film pollution in the north sector of the Black Sea for 2019, as well as the results of satellite monitoring of film pollution associated with the accident at the CPC terminal near Novorossiysk in 2021 (see Table 1). It is noteworthy that in 2025, a similar accident occurred in the area of the CPC terminal (http://www.aerocosmos.info/news/detail.php?ELEMENT_ID=7196 (accessed on 23 December 2025)), the consequences of which remain to be investigated in the future.

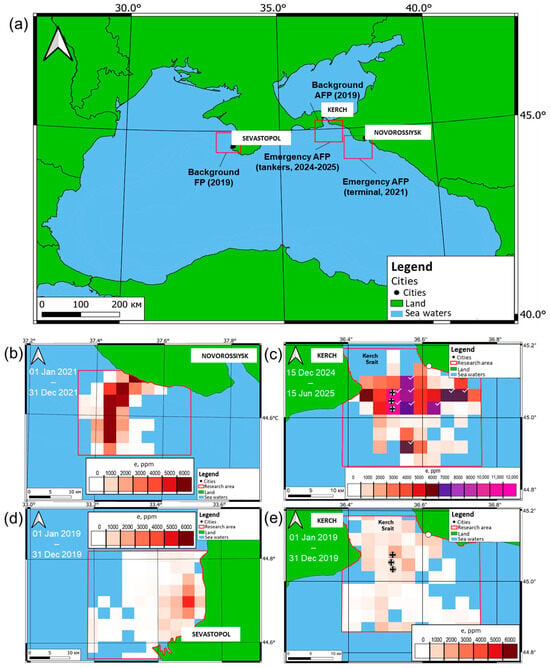

To conduct a comparative analysis, maps were created illustrating the spatial distribution of AFM exposure across all four compared local sites using a compatible color and the same spatial scale. These maps are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

(a) Boundaries of compared local sites of Black Sea coastal waters and (b–e)—mapped eAFP criterion near Novorossiysk in 2021, near Sevastopol in 2019, near the Kerch Strait from 15 December 2024 to 15 June 2025 (after the tanker accident), and in 2019 (background), respectively.

Figure 6a shows boundaries of the local areas for which the comparison was conducted, indicating the monitoring periods. Figure 6b–e show AFP criterion maps for individual local areas and monitoring periods, namely (see Table 1):

- -

- The coastal water area near Novorossiysk (Figure 6b) for 2021, where an accident occurred at an oil terminal in August of that year, and therefore this case can be classified as “emergency”.

- -

- The coastal waters near the Kerch Strait near the Volgoneft-212 and Volgoneft-239 tanker accidents, for which the AFP exposure maps were calculated for two periods:

- -

It should be noted that the local sites under consideration, No. 3, No. 4, and No. 5 (no more than ~1000 km2 area), are characterized by intense pollution sources, which have a crucial influence on the levels of the averaged eAFP indicator. In the larger sites, No. 1 and No. 2 (~10.2 thousand km2 area), the averaged eAFP values are determined by a combination of background and highly concentrated pollution, including AFP. This can lead to significant differences in the averaged eAFP values obtained for local and larger areas. Therefore, we do not compare the eAFP levels for local and large test sites.

Figure 6 demonstrates the following. The case shown in Figure 6e (south of the Kerch Strait, 2019) was characterized by the lowest AFP exposure compared to the cases shown in Figure 6b–d (the water area near Novorossiysk, Sevastopol, and the water area near the Kerch Strait in the emergency period from 15 December 2024, to 15 June 2025, after the tanker accidents). The e criterion values in this area (Figure 6e) range from 0 to 2000 ppm. It should be noted that the area near the Kerch Strait is under a quite intense anthropogenic load, with ships constantly traveling through this water area [3]. Figure 6e demonstrates the background level of anthropogenic pollution in a local emergency area near the Kerch Strait under conditions of intensive shipping and no emergency events.

An analysis of Figure 6c in comparison with Figure 6e reveals a significant increase in the AFP exposure levels in almost all parts of the studied local site of coastal waters near the Kerch Strait, recorded during the emergency monitoring period from 15 December 2024, to 15 June 2025. This increase is obviously related to the tanker accident. Figure 4 shows more detailed maps displaying the monitoring result from Figure 6c. A significant portion of the cells (these cells are marked off with ticks in Figure 4d and Figure 6c) are characterized by an extremely high level of AFP exposure, exceeding the threshold of 6000 ppm and reaching ~12,000 ppm.

A comparative analysis of Figure 6c,e (accident) and (background) reveals that the sea surface exposure to AFP in individual cells of the study area increased approximately 6-fold (up to ~12,000 ppm) during the accident compared to ~2000 ppm (background). Considering that the bulk of the pollutant (fuel oil) was located not on the surface but in the water column [18,35], the recorded ~6-fold increase in the eAFP value due to the accident (for the surface only) is of considerable concern. Satellite monitoring of this local site of coastal waters is ongoing.

An analysis of Figure 6b, which illustrates the consequences of another accident (the oil spill near the CPC terminal in 2021), shows that in this case the AFP exposure indicator values reached high values (approximately 6000 ppm) over a significant portion of the water area near Novorossiysk. Taking this into account as well as the results of the analysis of Figure 6e (background, eAFP < 2000 ppm for most cells), we can conclude that the accident at the CPC terminal in 2021 caused approximately a ~3-fold greater negative environmental impact. In this situation, only a surface spill is at issue. The recorded and quantified consequences are likely not catastrophic (unlike the Kerch Strait tanker accident discussed above).

Based on the analysis of Figure 6, let us consider the results of monitoring the region of water areas near the city of Sevastopol (Figure 6d). A distinctive feature of this section is the presence of a natural source of film pollution (FP) within its boundaries—hydrocarbon seep [6], which is not anthropogenic. Analysis of Figure 6d allows us to see the approximate location of this source. It corresponds to the cell with the most saturated red color north of Sevastopol. The AFP exposure criterion in the area of this source reached ~4000 ppm. In the surrounding cells, this indicator reached lower values (1000–3000 ppm, and less). Moreover, a joint analysis of Figure 6d,e indicates that, in general, in the areas corresponding to these figures, the situation with pollution in quantitative terms was approximately the same (predominantly light pink color of the cells, with local peaks). The exception is that to the north of the city of Sevastopol pollution is caused mainly by natural sources, and to the south of the Kerch Strait—by the ship traffic.

Thus, using the developed approach, film pollution features in various local areas of the Black Sea under different conditions were reasonably compared and discussed.

5. Conclusions

Considerable widespread increase in anthropogenic load on coastal water areas, on the one hand, and unique capabilities of SAR remote sensing methods for registering water surface pollution, on the other hand, determine the relevance of research involving satellite monitoring of anthropogenic impact on the marine environment.

At the same time, a number of problems remain unresolved. One such problem is poorly developed approaches that allow for a quantitative analysis of the sea surface pollution (including anthropogenic film pollution) informational products, which are the result of long-term satellite SAR monitoring.

In this paper, an approach aimed at solving this problem is elaborated. We address this problem through the statistical analysis of anthropogenic film pollution (AFP) of coastal water on a regular grid according to SAR satellite multitemporal data series involving a methodology to calculate the accumulated area of registered AFP, correlated with accumulated area of used SAR data. In general, we aimed to obtain spatial distributions of the estimation of relative frequency of AFP event occurrences, notionally termed the AFP exposure criterion (eAFP).

This enables the creation of an information product that statistically characterizes spatiotemporal AFP distributions while minimizing distortions caused by variations in satellite coverage density and meteorological conditions. The key advantages and innovative contributions of such information products include progress toward enabling reasonable comparisons of satellite monitoring results across various marine areas, under unequal monitoring conditions. We note the remaining limitations of AFP satellite monitoring, mainly due to the difficulty of identifying such objects among a variety of look-alike formations, the inability to probe excessively thin or small areas of contamination, and the lack of the differentiation of AFP by thickness or pollutant classes. However, a significant challenge remains the systematization and analysis of fragmented outcomes from long-term satellite AFP monitoring. This is necessary to obtain quantitative estimates that characterize the intensity of pollution in marine areas. The article focuses primarily on this problematic.

On a number of test sites, we demonstrate that realistic estimates of the AFP level in the cells of a regular spatial grid can be obtained and utilized. Background and peak values of the proposed quantitative eAFP criterion for assessing the AFP level for several coastal waters of the Black Sea and Avacha Gulf have been determined. In particular, background levels of the eAFP criterion were calculated for coastal waters under conditions of intensive shipping, and it is shown that accidents in maritime transport led to an increase in negative impacts by 3–6-fold in comparison with background levels of the eAFP criterion.

The resulting information products characterizing the studied water areas using the applied quantitative eAFP criterion can be used, among other things, when making scientifically grounded managerial decisions. Further, the processing of long-term series of SAR satellite monitoring data using the quantitative AFP detection approach under development will enable revealing trends and regularities in the spatiotemporal dynamics of such pollution, as well as assessing the efficiency of measures to control anthropogenic load and mitigate accidents in coastal waters. It should also be noted that in future the elaborated approach will be applicable for processing multi-source heterogeneous data (e.g., from other remote sensing satellites and unmanned aerial vehicles).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.B. and V.Z.; methodology, V.Z.; validation, V.B., V.Z. and V.S.; formal analysis, V.B. and V.Z.; SAR. and AFP. investigation, V.Z. and V.S.; data curation, V.Z. and V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, V.B., V.Z. and V.S.; writing—review and editing, V.B. and V.Z.; visualization, V.S. and V.Z.; supervision, V.B.; project administration V.Z.; funding acquisition, V.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Science and Higher Education grant number FNEE-2024-0002.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AFP | Anthropogenic film pollutions |

| GIS | Geoinformation systems |

| CPC | Caspian Pipeline Consortium |

| ENVI+IDL | Environment for Visualizing Images + Interactive Data Language |

| FP | Film Pollution |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine |

| NCEP | National Centers for Environmental Prediction |

| SAR | Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| SG | Satellite Group |

References

- Bondur, V.G. Aerospace methods and technologies for monitoring oil and gas areas and facilities. Izv. Atmospheric Ocean. Phys. 2011, 47, 1007–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierach, M.M.; Holt, B.; Trinh, R.; Pan, B.J.; Rains, C. Satellite detection of wastewater diversion plumes in Southern California. Estuarine, Coast. Shelf Sci. 2017, 186, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.Y. Slicks and Oil Films Signatures on Synthetic Aperture Radar Images. Issled. Zemli Iz Kosmosa 2007, 3, 73–96. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Bondur, V.; Zamshin, V. Study of Intensive Anthropogenic Impacts of Submerged Wastewater Discharges on Marine Water Areas Using Satellite Imagery. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.Y.; Kucheiko, A.A.; Filimonova, N.A.; Kucheiko, A.Y.; Evtushenko, N.V.; Terleeva, N.V.; Uskova, A.A. Spatial and temporal distribution of oil spills in the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea based on SAR images: Comparative analysis. Issled. Zemli Iz Kosmosa 2017, 2, 13–25. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondur, V.G.; Kuznetsova, T.V. Detecting gas seeps in Arctic water areas using remote sensing data. Izv. Atmospheric Ocean. Phys. 2015, 51, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingas, M.; Brown, C. Oil Spill Remote Sensing. In Earth System Monitoring: Selected Entries from the Encyclopedia of Sustainability Science and Technology; Orcutt, J., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 337–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondur, V.G.; Filatov, N.N.; Grebenyuk, Y.V.; Dolotov, Y.S.; Zdorovennov, R.E.; Petrov, M.P.; Tsidilina, M.N. Studies of hydrophysical processes during monitoring of the anthropogenic impact on coastal basins using the example of Mamala Bay of Oahu Island in Hawaii. Oceanology 2007, 47, 769–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, G.; Meyer-Roux, S.; Muellenhoff, O.; Pavliha, M.; Svetak, J.; Tarchi, D.; Topouzelis, K. Long term monitoring of oil spills in European seas. Int. J. Remote. Sens. 2009, 30, 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.Y.; Zatyagalova, V.V. A GIS approach to mapping oil spills in a marine environment. Int. J. Remote. Sens. 2008, 29, 6297–6313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochergin, S.V.; Fomin, V. Variational Identification of Input Parameters in the Model of Distribution of the Pollutants from the Underwater Source. Phys. Oceanogr. 2019, 26, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatsepa, S.N.; Ivchenko, A.A.; Solbakov, V.V.; Stanovoy, V.V. A method for modeling of the consequences of super-continuous accidents on oil production objects in the Arctic region. Arct. Antarct. Res. 2018, 64, 439–454. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulatov, M.G.; A Kravtsov, Y.; Lavrova, O.Y.; Litovchenko, K.T.; I Mityagina, M.; Raev, M.D.; Sabinin, K.D.; Trokhimovskii, Y.G.; Churyumov, A.N.; Shugan, I.V. Physical mechanisms of aerospace radar imaging of the ocean. Physics Uspekhi 2003, 46, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brekke, C.; Solberg, A.H. Oil spill detection by satellite remote sensing. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2005, 95, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krestenitis, M.; Orfanidis, G.; Ioannidis, K.; Avgerinakis, K.; Vrochidis, S.; Kompatsiaris, I. Oil Spill Identification from Satellite Images Using Deep Neural Networks. Remote. Sens. 2019, 11, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-J.; Singha, S.; Mayerle, R. A deep learning based oil spill detector using Sentinel-1 SAR imagery. Int. J. Remote. Sens. 2022, 43, 4287–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knyazev, N.A.; Lavrova, O.Y.; Kostianoy, A.G. Satellite radar monitoring of oil pollution in the water areas between anapa and gelendzhik in 2018–2020. J. Oceanol. Res. 2021, 49, 163–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrova, O.; Loupian, E.; Kostianoy, A. Satellite monitoring of the fuel oil spill in the Kerch Strait area on December 15, 2024: Preliminary results. Curr. Probl. Remote. Sens. Earth Space 2025, 22, 327–335. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, A. (Ed.) European Maritime Safety Agency CleanSeaNet Activities in the North Sea. In Oil Pollution in the North Sea. The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 41, pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mityagina, M.; Lavrova, O. Satellite Survey of Inner Seas: Oil Pollution in the Black and Caspian Seas. Remote. Sens. 2016, 8, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimenko, S.K.; Ivanov, A.Y.; Evtushenko, N.V. Oil pollution of the gulf of oman based on monitoring with synthetic aperture radar. J. Oceanol. Res. 2023, 51, 114–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krek, E.V.; Krek, A.V.; Kostianoy, A.G. Chronic Oil Pollution from Vessels and Its Role in Background Pollution in the Southeastern Baltic Sea. Remote. Sens. 2021, 13, 4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Magd, I.A.; Zakzouk, M.; Ali, E.M.; Abdulaziz, A.M.; Rehman, A.; Saba, T. Mapping oil pollution in the Gulf of Suez in 2017–2021 using Synthetic Aperture Radar. Egypt. J. Remote. Sens. Space Sci. 2023, 26, 826–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondur, V.; Chernikova, V.; Chvertkova, O.; Zamshin, V. Spatiotemporal Variability of Anthropogenic Film Pollution in Avacha Gulf near the Kamchatka Peninsula Based on Synthetic-Aperture Radar Imagery. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamshin, V.V.; Matrosova, E.R.; Khodaeva, V.N.; Chvertkova, O.I. Quantitative Approach to Studying Film Pollution of the Sea Surface Using Satellite Imagery. Phys. Oceanogr. 2021, 28, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpers, W.; Holt, B.; Zeng, K. Oil spill detection by imaging radars: Challenges and pitfalls. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2017, 201, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, I.S. Discovering the Ocean from Space: The Unique Applications of Satellite Oceanography; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; 638p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulycheva, E.V.; Krek, A.V.; Kostianoy, A.G.; Semenov, A.V.; Joksimovich, A. Oil Pollution in the Southeastern Baltic Sea by Satellite Remote Sensing Data in 2004–2015. Transp. Telecommun. 2016, 17, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, L.; Xing, Q.-G.; Liu, X.; Zou, N.-N. Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Oil Spills in the Bohai Sea Based on Satellite Remote Sensing and GIS. J. Coast. Res. 2019, 90, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinov, S.; Bookman, R.; Levin, N. Spatial and temporal assessment of oil spills in the Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 167, 112338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Xu, J.; Pan, J.; Yang, J.; Wu, P.; Meng, X. Detection of marine oil spills from radar satellite images for the coastal ecological risk assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, A.N. Foundations of the Theory of Probability; Chelsea Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1950; 88p. [Google Scholar]

- Feller, W. An Introduction to Probability Theory and Its Applications; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1968; Volume 1, 536p, ISBN 978-0-471-25708-0. [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R.C.; Woods, R.E. Digital Image Processing, 2nd ed.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002; 793p, ISBN 978-0-201-18075-6, 978-0-13-094650-8. [Google Scholar]

- Nemirovskaya, I.A.; Zavialov, P.O.; Medvedeva, A.V.; Khalikov, I.S.; Konovalov, B.V.; Kalgin, V.U. Transformation of Fuel Oil in the Black Sea Two and Half Months after the Tanker Accident. Dokl. Earth Sci. 2025, 523, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrova, O.; Loupian, E.; Kostianoy, A. Consequences of tanker accidents on the Black Sea side of the Kerch Strait on December 15, 2024: A comprehensive analysis of satellite and meteorological data. Curr. Probl. Remote. Sens. Earth Space 2025, 22, 282–289. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.