Abstract

This study presents a model experiment on the oblique maneuvering of a ship in a floating ice environment. A series of captive model tests was conducted in both open-water and synthetic ice fields at concentrations of 60%, 70%, and 80%. The model was tested in a conventional towing tank using non-refrigerated polypropylene ice floes to simulate a broken ice field. Surge force, sway force, and yaw moment on the hull were measured under various drift angles and three speeds. Results show that in oblique motion, ice floes around the hull experience significant overturning and piling up, especially on the drift side, leading to random collisions with the hull. These interactions markedly affect the hydrodynamic forces. As the drift angle increases, the surge, sway, and yaw forces on the hull increase nonlinearly. The comparison between open-water and ice conditions indicates that floating ice can significantly increase the resistance and maneuvering forces. Higher ice concentrations lead to more frequent and more extensive contact between the hull and the ice floes, thereby further amplifying all components of the hydrodynamic forces. This work provides experimental data for validating calculation methods of ship resistance and maneuvering in broken ice. It demonstrates a feasible experimental approach for studying ship maneuvers in a floating ice channel.

1. Introduction

The retreat of Arctic sea ice has steadily expanded the navigable season of Arctic shipping routes [1]. In particular, the Northern Sea Route (NSR) offers a significantly shorter passage and holds promise as a vital Asia–Europe trade corridor [2], translating into substantial time and fuel savings for shippers [3]. Recent years have indeed seen growing traffic along the NSR, with steady increases in transit voyages and cargo volumes. In line with these trends, new voyage planning tools and vessel-specific analyses are emerging to evaluate NSR operations under evolving ice conditions [4,5].

Ships operating in ice-covered waters face complex resistance and maneuvering challenges. Early analytical and empirical models addressed performance in level ice [6]. Williams and Waclawek [7] considered ice–ship interactions and proposed a new experimental and analytical methodology for evaluating ship maneuverability in ice-covered regions. Liu et al. [8] further advanced the ice–ship interaction model by integrating analytical formulations with numerical simulations to reproduce ship maneuvering motions in level ice, enabling more accurate predictions of surge force, sway force, and yaw moment on the hull induced by ice sheets. An IHI ice–ship interaction model was subsequently developed by Liu [9], thus permitting real-time simulation of ship motions in ice-covered regions. However, predicting ship behavior in broken or pack ice is more complicated due to many interacting factors [10]. Modern approaches increasingly rely on advanced numerical simulations. For example, real-time finite-element models and discrete element methods have been developed to capture ice–hull interaction forces during ship transits [11,12]. These methods allow the modeling of multiple ice–ship contact events and failure processes that empirical formulas cannot fully cover. Coupled CFD–DEM techniques further incorporate hydrodynamic effects of the surrounding water and ship waves, improving the accuracy of broken-ice resistance predictions [13]. Overall, research has progressed from empirical rules to high-fidelity simulations, though each approach has limitations in applicable ice conditions and requires careful validation against experimental or full-scale data [10,14].

Traditional ice model tests in refrigerated ice tanks provide reliable predictions of ship–ice interaction but are costly and resource-intensive to conduct [15]. To reduce costs, researchers have developed non-frozen model ice techniques using synthetic materials to simulate ice floes in ordinary towing tanks [16]. This approach allows repeated experiments at normal temperatures, significantly improving efficiency and enabling more exhaustive exploration of parameters. For instance, [17] employed polypropylene “model ice” in a conventional towing tank to successfully test a ship’s performance in broken ice without a dedicated ice basin. Such non-frozen model ice experiments have demonstrated good agreement with corresponding tests using actual ice: the measured resistance and ice loads using synthetic ice correlated well with those from traditional ice tank tests [18]. This fidelity validates the use of artificial ice methods and has led to their adoption in developing new prediction tools. For example, recent empirical formulas for ship resistance in brash ice have been derived and calibrated based on synthetic ice experiments [19].

Despite these advances, there remains a notable research gap regarding ship hydrodynamics under oblique ice navigation conditions. Most existing studies and ice-class design regulations focus on head-on icebreaking performance or straight-line resistance of dedicated icebreakers. In contrast, the maneuvering behavior of non-icebreaking ships in floating ice, including turning, sideways drifting, and low-speed handling among ice floes, is still poorly understood [20]. Some specific scenarios have been studied, for example, methods exist to estimate loads on moored ships in ice ridges [21], but comprehensive experimental or numerical investigations of free-running ship maneuvers in broken-ice fields are scarce. This knowledge gap introduces uncertainty in predicting course-keeping, turning ability, and safety for ordinary ships transiting ice-covered waters. Consequently, researchers and regulators have highlighted the need for new data and models in this area [22]. Filling this gap is essential for improving ice-going vessel design and operational guidelines beyond the scenarios currently covered by the Polar Code.

This study systematically investigates the hydrodynamic characteristics of ships during oblique motion in ice-covered regions, addressing a critical gap in maneuvering research under floe ice conditions. Experiments were conducted using a polar research vessel model in a standard towing tank, where artificial non-frozen ice floes made of paraffin wax were deployed at different concentrations to simulate a ship transiting through broken ice at various drift angles. This approach eliminates the high cost and complexity of conventional refrigerated ice tanks and enables repeatable maneuvering tests under ambient conditions, offering a new experimental pathway for ice hydrodynamics research. During the experiments, the surge force, sway force, and yaw moment acting on the hull were measured under varying drift angles and ship speeds. Corresponding hydrodynamic forces were derived. By comparing results across different ice concentrations, the study systematically reveals the influence of floe concentration on a ship’s oblique hydrodynamic behavior. These findings provide theoretical support for the design of ice-going ship maneuverability and the development of safer navigation strategies in polar regions.

2. Experimental Setup

2.1. Facility and Equipment

The experiments were conducted in the towing tank of the China Ship Scientific Research Center. The tank has a length of 150 m, a width of 7 m, and a depth of 4.5 m, which is sufficient to eliminate shallow-water effects for the model scale considered.

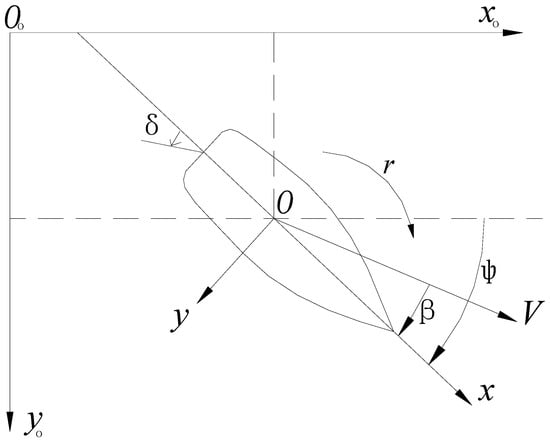

The ship coordinate system is shown in Figure 1. The Earth-fixed system is a right-handed Cartesian frame whose origin coincides with the ship’s center of gravity at . The axis points along the initial heading in the horizontal plane, points to starboard, and is vertical downward. The body-fixed coordinate system is attached to the ship, with its origin at . The axis points forward, to starboard, and downward. The drift angle is defined as the angle between the ship’s velocity vector and the axis, positive when the velocity rotates clockwise toward starboard. A 6-component dynamometer was used in a captive model configuration to measure the forces and moments on the ship model. The dynamometer recorded the surge force , sway force , and yaw moment acting on the model, with an accuracy of 0.5% and a resolution of 1.5 N. High-speed video cameras were installed above the tank to capture the interactions between the model and ice floes at the bow and along the hull during each run. All tests were conducted at ambient room temperature.

Figure 1.

The sketch of coordinate systems.

2.2. Similarity Criteria and Ship Model

In these model tests, geometric, kinematic, and dynamic similarities with the full-scale scenario were maintained to the extent possible. The model scale was chosen such that the model and floes satisfy the same geometric ratios as the real ship and full-scale ice floes. The ice thickness ratio was determined as follows:

where and are the real and model ice thickness, respectively. The density of the model ice was matched to real sea ice density to satisfy density similarity:

Hydrodynamic scaling was based on Froude number similarity, since gravity is the dominant force for both open-water hydrodynamics and the buoyancy of ice floes. The model was towed at speeds ensuring the same Froude number as the corresponding full-scale scenario:

where and denote the model and full-scale ship speeds, and and their corresponding overall lengths. Ice breaking was intentionally excluded from the present experiments because the synthetic ice floes employed in the tests remained intact upon impact and behaved as rigid bodies without further fragmentation. This treatment is considered appropriate for low-speed operations in brash-ice conditions, where the behavior of individual ice pieces is dominated by rigid-body motions such as sliding, submergence, and overriding rather than by mechanical failure. Under such circumstances, the primary interaction forces between the ship and the ice arise from gravity, inertia, and friction during direct contact, which are analogous to open-water hydrodynamic forces but enhanced by additional drag induced by ice impacts. By omitting ice-crushing effects, the experiments effectively represent a conservative, “worst-case” maneuvering scenario in a pre-broken ice field, where the vessel advances through existing floes rather than fracturing a continuous ice sheet.

The ship model used in the study is a 1:35-scale representation of a CRV-type polar research vessel with an ice-strengthened hull, shown in Figure 2. Constructed from fiberglass, the model features a slender icebreaking form characterized by a raked stem and a broad beam, typical of polar research vessels. Its principal parameters are listed in Table 1. The model was unpropelled and employed in a captive, towed configuration. It was mounted on a planar-motion mechanism that enabled the imposition of a prescribed drift (yaw) angle while the model was towed in a straight path.

Figure 2.

The line of the CRV ship. SAT means station number.

Table 1.

Principal parameters of the ship model (scale 1:35).

2.3. Synthetic Ice and Channel Preparation

To simulate a brash ice channel with controlled ice concentration, non-refrigerated synthetic ice floes made of polypropylene were used. This material has a density similar to real sea ice and remains solid at room temperature, allowing repeatable tests without the need for an ice-making facility. The synthetic floes were molded into square pieces of side length 0.12 m and thickness 0.02 m. Each piece weighs about 0.262 kg and has a planar area of 0.0144 m2. Table 2 summarizes the main properties of the model ice pieces and the ice field configuration.

Table 2.

Synthetic model ice properties and ice field configuration.

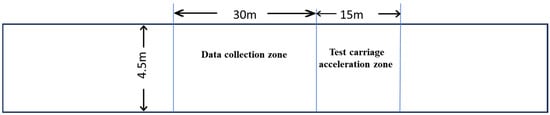

To conduct a test at a given ice concentration, the required number of synthetic floes was evenly distributed within a designated ice channel region of the tank. For these tests, we used a 30 m long section of the tank as the floating ice channel. Upstream and downstream of this section, 15 m long buffer zones were left as a preparation zone to allow the model to achieve a steady speed before entering the ice and a runout zone to decelerate after the test. A lightweight frame with netting was used along the sides of the channel to contain the ice pieces within the 4.5 m width during the run. Figure 3 illustrates the initial configuration of the experimental area.

Figure 3.

The initial configuration of the experimental area.

2.4. Test Conditions

Prior to each test, the ice pieces were gently placed in the water and allowed to drift into a uniform distribution. The ice concentration is defined as the ratio of total floe area to the channel area. We investigated three representative concentrations, as shown in Figure 4: a medium concentration of 60%, a high concentration of 80%, and an intermediate 70% case. In a full-scale scenario, 60% might represent a medium brash ice condition where open-water patches still exist between floes, whereas 80% represents a heavy brash or marginal ice zone condition with floes densely packed and frequent hull-ice contacts. For reference, broken ice floes in the Arctic marginal ice zone typically have diameters on the order of 0.5-8 m and thickness 0.5-3 m. The chosen model floe size of 0.12 m represents roughly a 5 m full-scale floe, and 0.02 m thickness represents ~0.8 m full-scale thickness, consistent with field observations of broken ice floe dimensions.

Figure 4.

Example of the floating ice field setup at different concentrations.

Two sets of experiments were performed: (a) open-water (no ice) tests, to establish the baseline hydrodynamic forces on the hull, and (b) floating ice tests at 60%, 70%, and 80% concentrations. Each test condition for both open water and ice channel operations was identified by a case number specifying the drift angle and towing speed, as listed in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Test conditions in open water.

Table 4.

Test conditions in the ice channel.

2.5. Data Processing

When the model was fully inside the ice channel, the measured force time histories were averaged over a steady 8 s interval. The measured forces and moments were then nondimensionalized as follows:

3. Results

3.1. Hydrodynamic Loads in Open Water

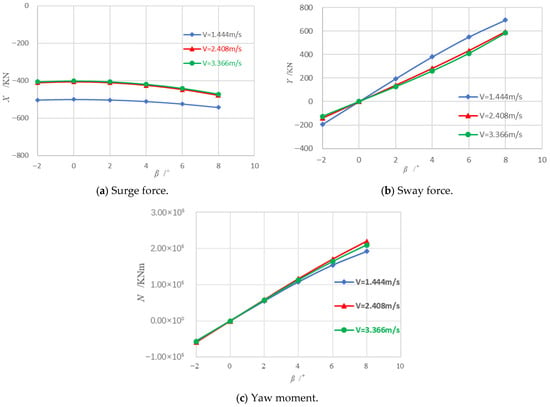

To investigate the relative contributions of ice loads and hydrodynamic loads, conventional oblique-towing tests were first conducted to measure the open-water hydrodynamic forces on the hull. During each test, the time histories of the forces were recorded for an 8 s interval, and the mean value over this steady period was taken as the representative force for that condition. Each test condition was repeated twice, and the averaged value of the two runs was used as the final result. Based on Froude number similarity, the hydrodynamic forces measured in the experiments were converted to full scale. The scaled hydrodynamic results are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The hydrodynamic forces in open water.

The surge force increases in magnitude with increasing drift angle . At three different speeds, the change from to is noticeable but moderate, reflecting the limited increase in projected frontal area at small drift angles. As the drift angle and the speed increase, resulting in a steeper growth slope of , the surge force increases more rapidly. The sway force exhibits a strong, nearly linear growth with , especially at the higher speeds. While near , it rises rapidly as increases, indicating the formation of strong side-force components due to flow separation and cross-flow drag. At , the sway force is four times stronger than at , showing that oblique flow produces disproportionately large sway loads on the hull. The yaw moment increases almost linearly with and exhibits a very similar trend to the sway force, which is expected since both arise from asymmetric cross-flow along the hull. A larger drift angle produces a stronger maneuvering moment on the hull. At , the yaw moment is approximately four to five times that at , demonstrating a pronounced linear dynamic behavior.

3.2. Hydrodynamic Loads in Ice Channel

Based on the test conditions described earlier in Table 3, non-frozen model ice experiments were conducted for ice concentrations of 60%, 70%, and 80%. The interactions between the ship model and the non-frozen ice floes under these three concentrations are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The phenomenon of the interaction between ship and ice in different concentrations.

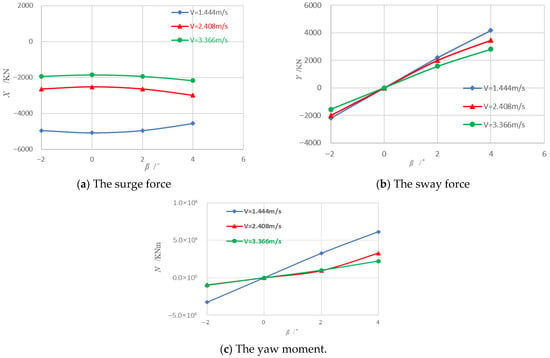

Following the methodology described previously, the corresponding hydrodynamic forces were obtained, as presented in Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9. As shown in Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9, the hydrodynamic forces of the ship—surge force , sway force , and yaw moment —increase markedly with the drift angle for each ice concentration (60%, 70%, and 80%). These curves represent combined data from tests at three speeds (1.444, 2.408, and 3.366 m/s). Meanwhile, to better illustrate the influence of ice concentration on the hydrodynamic characteristics of ships navigating in ice-covered regions, Table 5 and Figure 10 present the surge forces of the ship under straight-ahead motion at different ice concentrations. As can be seen from Figure 10, the surge force acting on the ship increases as the ice concentration increases. At an ice concentration of 80%, the increase is particularly significant.

Figure 7.

Hydrodynamic forces of the ship in ice concentration .

Figure 8.

Hydrodynamic forces of the ship in ice concentration .

Figure 9.

Hydrodynamic forces of the ship in ice concentration .

Table 5.

Hydrodynamic forces X of the ship in different ice concentrations ().

Figure 10.

Hydrodynamic forces of the ship in different ice concentrations ().

3.2.1. Surge Force

The surge force increases monotonically with drift angle for all ice concentrations. At , has a finite value corresponding to the ship’s forward resistance in ice. As grows from 0° to 8°, rises gradually but consistently. This growth is relatively moderate and less dramatic than that of the sway force, owing to the fact that as the ship yaws, the forward component of velocity decreases while some side force develops. Still, a larger drift angle means a greater projected frontal area and more ice being engaged by the bow, which leads to a higher surge resistance. A comparison of the three ice-concentration curves clearly indicates that 80% concentration yields the highest at all drift angles, 70% is intermediate, and 60% is the lowest. The value of in 80% ice concentration is more than twice that in 60% ice concentration, and by and this difference continues to widen as the drift angle increases. This indicates that denser ice concentration significantly amplifies the surge force on the hull. Physically, in higher concentrations, the bow encounters more frequent and simultaneous ice impacts, which increases the resistance.

3.2.2. Sway Force

The sway force starts near zero at , since there is essentially no sideways force when the ship is aligned with its motion, and then grows dramatically with increasing drift angle . The relationship between and is strongly nonlinear. At small drift angles, remains very low, but beyond that, it increases rapidly as the hull presents more side surface to the ice field. By , has become quite large for all concentrations, indicating substantial side force due to the ship–ice interactions along the hull. Notably, rises much faster with than and the sway force is far more sensitive to drift angle. For example, in the 70% ice concentration test at v = 0.407 m/s, when the drift angle increases from to , the sway force increases by more than four times, whereas the surge force increases by only about one and a half times. This indicates that as the drift angle grows, the sway force gradually becomes the dominant component of the hydrodynamic load.

In terms of ice concentration, higher concentrations yield a substantially larger at any given drift angle. Even at , 80% ice concentration produces more sway force than a 60% concentration does at the same angle, because the denser ice field engages with the hull more continuously on the side. During the model tests under high ice concentration conditions, the accumulation of broken ice leads to a noticeable increase in the sway force. The ship–ice interaction becomes more pronounced at higher ice concentrations. At larger drift angles, the difference is even more pronounced.

The 70% ice concentration curve lies between these extremes, but closer to 80% in magnitude. The trend reflects that a denser ice cover presents more persistent contact and friction along the ship’s side, resulting in higher side loads. In other words, the steeper the ice concentration, the steeper the curve, as the ship must exert more sway force to push through a crowded ice field.

3.2.3. Yaw Moment

The yaw moment exhibits a trend similar to that of . Starting from essentially zero at , increases nonlinearly with drift angle for all concentrations. As the drift angle grows, the imbalance of ice forces on the bow and along the hull generates a yawing moment that becomes appreciable. By , sizeable yaw moments are observed, indicating that the ship experiences a strong turning tendency due to asymmetric ice loading on the hull. The increase in is less steep than that in , reflecting the fact that the yaw moment is induced by the sway force distribution along the ship. For small drift angles, the yaw moment remains negligible, but beyond a few degrees, it rises significantly.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Ice on Hydrodynamic Forces

The experimental results clearly show that the presence of floating ice significantly alters the ship’s hydrodynamic force compared to open water. In open water, the surge force is governed purely by fluid resistance, and the sway force and yaw moment remain near zero at zero drift angle. With even a small drift angle, open water and begin to rise due to the increased projected area of the hull, but their magnitudes are modest. By contrast, in an ice-covered scenario, additional ice–hull interaction forces emerge. Even at , broken ice pieces in front of the bow introduce extra resistance, roughly doubling the in the 60% ice concentration relative to open water. At nonzero drift angles, the disparity becomes more pronounced: the ice field produces one-sided contact forces that generate considerable sway load and yaw moment on the hull.

This highlights that and in the ice-covered conditions are not only higher in magnitude but also grow faster with angle than in open water. The surge force in ice also exceeds the open-water drag at all angles, reflecting the extra work done to push through ice floes. Notably, at higher drift angles, the total resistance in ice can be almost three times the open-water value. The presence of ice yields an overall increase in resistance and a dramatic rise in sway force and yaw moment relative to open water, due to the added collision, friction, and accumulation of ice around the hull.

4.2. Effect of Ice Concentration

Higher ice concentrations lead to systematically larger hydrodynamic forces and more severe ice–hull interaction effects. As ice concentration increases from 60% to 80%, the frequency and extent of hull–ice contacts grow, causing all components of force to rise. At 60% concentration, there are open-water gaps between floes. This yields a certain amount of extra resistance and occasional sway forces when a floe is encountered, but between contacts, the ship experiences mostly open-water flow. As a result, the forces at 60% can be variable—for example, in straight-ahead motion, some runs saw total resistance on the order of two to four times the open-water value, depending on how ice floes aligned with the bow. However, at 70% and especially 80% ice concentration, the ice floes form a denser pack that engages more of the hull’s length. It shows that at high concentration, the ice pieces cling to the hull and slide along toward midship as the ship advances. The contact region extends farther down the side of the ship, and ice accumulation becomes much more pronounced. Consequently, the ship experiences a more continuous ice resistance and higher sway loads.

Each increment in concentration from 60% to 80% was found to increase the forces across all drift angles. In the 80% case, even a very small drift angle can result in immediate and strong hull–ice interactions, whereas the 60% case might still allow some water flow past the hull before a floe is encountered. Overall, increasing ice concentration not only raises the magnitude of hydrodynamic forces but also reduces the intermittency of ice contact, making the force response more consistently dominated by ice effects rather than open-water hydrodynamics.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we systematically analyzed the hydrodynamic characteristics of a ship operating under various ice concentrations, drift angles, and speeds, and explained the complex coupling mechanisms among ice, water, and the hull. The results demonstrate that ice-field distribution, oblique motion, and speed have significant effects on surge force, sway force, and yaw moment, and that the resulting force responses differ fundamentally from those in open-water conditions. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- The presence of floating ice causes a notable increase in all components of the hydrodynamic force on the ship. Compared to open water, a ship in broken ice experiences higher surge force and, especially, much larger sway force and yaw moment at equivalent drift angles. This is because ice–hull collisions and friction introduce additional resistance and asymmetric loading that are absent in open water.

- (2)

- Drift angle has a far more pronounced effect on ship forces in ice-covered water than in open water. In open water, increasing the drift angle yields a relatively predictable increase in drag and a moderate development of sway force and yaw moment. In contrast, in a floating ice field, even a small drift angle triggers a large asymmetric ice force. As the drift angle grows, the sway force and yaw moment in ice escalate rapidly owing to the piling-up and wedging of ice on the hull’s drift side.

- (3)

- The magnitude of hydrodynamic forces grows with increasing ice concentration. Higher ice densities lead to more frequent and extended contact between the hull and ice floes, which in turn amplifies the forces. In dense ice, ice floes accumulate and slide along the hull, resulting in significantly greater resistance and maneuvering loads than in sparser ice fields. Thus, all forces tend to increase as the ice concentration rises, with the ship in a high-density ice field experiencing the most severe forces.

In higher ice concentrations and at larger drift angles, the ship transitions into a regime of continuous ice contact where breaking, frictional sliding, and accumulation of floes dominate the forces. Consequently, the ice-induced forces become the primary contributors to the total load, whereas pure hydrodynamic forces from water play a secondary role. These findings indicate that both ice concentration and drift angle profoundly influence a hull’s hydrodynamic forces, and they must be accounted for when predicting ship performance and maneuvering in broken-ice conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Z. and Z.L.; methodology, Q.Z. and Z.L.; investigation, Z.L.; resources, W.G. and Z.L.; data curation, W.G. and J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.Z. and J.M.; writing—review and editing, Z.L.; visualization, Q.Z. and J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 12372242 and 52101315) and by the Key R&D projects of China (grant numbers 2021YFC2803401).

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article and are also available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| DEM | Discrete Element Method |

| NSR | Northern Sea Route |

References

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Zha, Y.; Wang, K.; Chen, C. Changing arctic northern sea route and transpolar sea route: A prediction of route changes and navigation potential before Mid-21st century. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsson, B.; Moe, A. Ten Years of International Shipping on the Northern Sea Route. Arct. Rev. Law Politics 2021, 12, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Kronbak, J. The potential economic viability of using the Northern Sea Route (NSR) as an alternative route between Asia and Europe. J. Transp. Geogr. 2010, 18, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ringsberg, J.W.; Rita, F. A voyage planning tool for ships sailing between Europe and Asia via the Arctic. Ships Offshore Struct. 2020, 15, S10–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Qian, S.; Dong, H.; Fan, J.; Xu, J.; Cao, L.; Xu, S.; Li, X.; Cai, C.; Huang, Y. Navigability of Liquefied Natural Gas Carriers Along the Northern Sea Route. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Riska, K.; Moan, T. A numerical method for the prediction of ship performance in level ice. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2010, 60, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, F.; Waclawek, P. Physical Model Tests for Ship Manoeuvring in Ice. In Proceedings of the SNAME American Towing Tank Conference, Iowa City, IA, USA, 24–25 October 1998; p. D021S009R002. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Lau, M.; Williams, F.M. Mathematical modeling of ice-hull interaction for ship maneuvering in ice simulations. In Proceedings of the SNAME International Conference and Exhibition on Performance of Ships and Structures in Ice, Banff, AB, Canada, 16–19 July 2006; p. D031S010R004. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. Mathematical Modeling Ice-Hull Interaction for Real Time Simulations of Ship Manoeuvring in Level Ice. Ph.D. Thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, NL, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S.-Y.; Choi, K.; Kim, H.-S. Investigation of ship resistance characteristics under pack ice conditions. Ocean Eng. 2021, 219, 108264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubbad, R.; Løset, S. A numerical model for real-time simulation of ship–ice interaction. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2011, 65, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuhkuri, J.; Polojärvi, A. A review of discrete element simulation of ice–structure interaction. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2018, 376, 20170335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Tuhkuri, J.; Igrec, B.; Li, M.; Stagonas, D.; Toffoli, A.; Cardiff, P.; Thomas, G. Ship resistance when operating in floating ice floes: A combined CFD&DEM approach. Mar. Struct. 2020, 74, 102817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrissova, S.; Bergström, M.; Hirdaris, S.E.; Kujala, P. Analysis of a collision-energy-based method for the prediction of Ice loading on ships. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Yang, D.; Gang, X.; Yu, C.; Ji, S.; Yue, Q. Development of a numerical ice tank based on DEM and physical model testing: Methods, validations and applications. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Z.; Yang, B.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, G. Experimental study of ship resistance in artificial ice floes. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2020, 176, 103102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhong, K.; Ni, B.-Y.; Li, Z.; Bergström, M.; Ringsberg, J.W.; Huang, L. A combined experimental and numerical approach to predict ship resistance and power demand in broken ice. Ocean Eng. 2024, 292, 116476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-C.; Lee, S.-K.; Lee, W.-J.; Wang, J.-y. Numerical and experimental investigation of the resistance performance of an icebreaking cargo vessel in pack ice conditions. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2013, 5, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Li, Z.; Ryan, C.; Ringsberg, J.W.; Pena, B.; Li, M.; Ding, L.; Thomas, G. Ship resistance when operating in floating ice floes: Derivation, validation, and application of an empirical equation. Mar. Struct. 2021, 79, 103057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zou, L.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X. Numerical Study on Non-Icebreaking Ship Maneuvering in Floating Ice Based on Coupled NDEM–MMG Modeling. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Gao, J.; Li, D. An engineering method for simulating dynamic interaction of moored ship with first-year ice ridge. Ocean Eng. 2019, 171, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujala, P.; Goerlandt, F.; Way, B.; Smith, D.; Yang, M.; Khan, F.; Veitch, B. Review of risk-based design for ice-class ships. Mar. Struct. 2019, 63, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).