Intelligent Multi-Objective Path Planning for Unmanned Surface Vehicles via Deep and Fuzzy Reinforcement Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A baseline Deep Q-Learning (DQN) framework is developed for USV path planning, forming a foundation for evaluating advanced fuzzy-enhanced techniques.

- A Fuzzy Deep Q-Learning (F-DQN) algorithm is proposed, combining reinforcement learning with fuzzy logic to achieve multi-objective optimization in terms of smoothness, energy efficiency, and safety.

- A multi-objective reward model is designed, integrating path deviation (PC), environmental fuel consumption (EE), and velocity deviation-based energy cost (ED), subject to an overall fuel constraint.

- A simulation environment is implemented, allowing both DQN and F-DQN agents to be tested across multiple scenarios to assess adaptability and robustness.

- Comparative results demonstrate that the proposed F-DQN significantly outperforms the baseline DQN in terms of trajectory smoothness, convergence stability, and total fuel consumption, validating its effectiveness for autonomous USV navigation.

2. Related Works

3. System Model and Problem Formulation

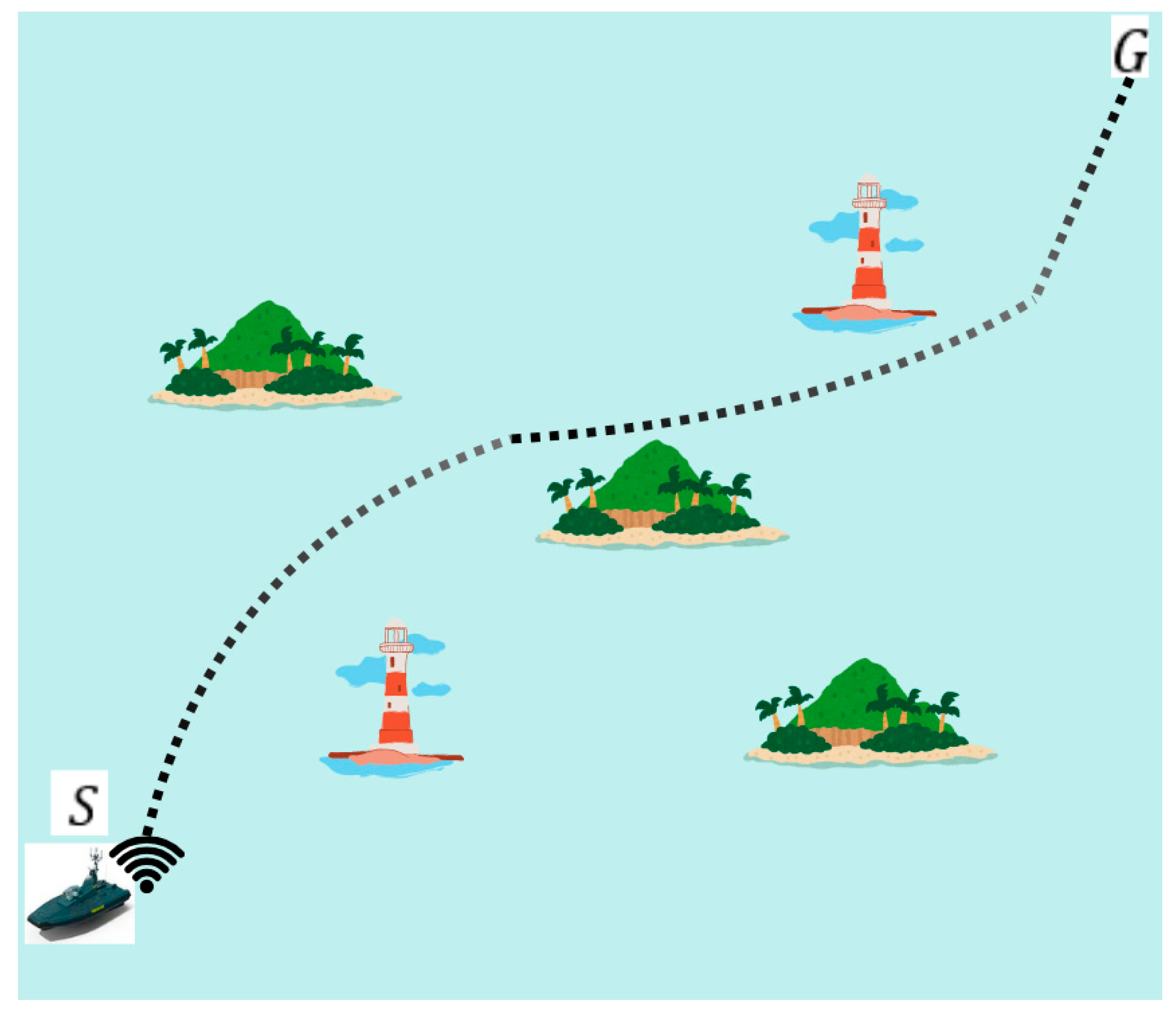

3.1. Overall System Topology

3.2. Problem Formulation

3.2.1. Traveled Distance

3.2.2. Path Deviations

3.2.3. Fuel Consumption

- (i)

- fuel consumption due to environmental conditions, and

- (ii)

- fuel consumption due to velocity deviations between consecutive path segments.

3.2.4. Overall Optimization Objective

4. Deep Q-Learning and Fuzzy Deep Q-Learning Frameworks

4.1. Reinforcement-Learning Formulation

4.2. State and Action Representations

4.3. Reward Function Design

4.4. Baseline Deep Q-Learning (DQN)

4.5. Fuzzy Deep Q-Learning (F-DQN)

- Action evaluation: the FIS assesses the feasibility or quality of possible actions based on fuzzy state variables, rather than discrete thresholds

- Reward evaluation: the FIS dynamically computes the composite reward by considering multiple uncertain or interdependent factors (distance, path deviation, and energy consumption).

- : traveled distance

- : path curvature

- : energy consumption,

- : overall path quality.

4.6. Neural-Network Configuration

- Input layer: Receives the environment’s state vector, which includes the USV’s current position, goal coordinates, velocity, and relative distances to the nearest obstacles.

- Fully connected layer 1 (128 neurons): Applies a linear transformation followed by a ReLU activation function.

- Fully connected layer 2 (128 neurons): Also activated by ReLU; reduces dimensionality while capturing higher-order correlations between motion and obstacle data. Serves as a transitional latent representation linking the abstracted features to the action space.

- Output layer: Produces one Q-value per available action (e.g., turn-left, turn-right, accelerate, decelerate, or maintain speed).

- For F-DQN: The same network is used, but the output Q-values are refined by the Fuzzy Inference System (FIS), which adjusts them based on the fuzzy evaluation of distance, path smoothness, and energy consumption.

5. Performance Evaluation

5.1. Simulation Environment

- Scenario 1: four obstacles (low-density environment),

- Scenario 2: six obstacles (medium-density environment),

- Scenario 3: eight obstacles (high-density environment).

5.2. Evaluation Metrics

- Path Length (D): Total distance traveled by the USV between start and goal points.

- Path Smoothness (PC): Cumulative angular deviation between consecutive trajectory segments (Equation (2)), representing the curvature of the path.

- Energy Consumption (EC): Combined metric incorporating environmental and velocity-dependent components (Equations (3)–(5)).

- Success Rate (SR): Ratio of episodes where the USV successfully reached the goal without collisions.

5.3. Comparative Results

5.4. Comparison with Existing Works

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Acronym | Definition |

| ACO | Ant Colony Optimization |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| APF | Artificial Potential Field |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| DOAJ | Directory of Open Access Journals |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| DQN | Deep Q-Learning |

| EE | Energy Consumption due to Environmental Conditions |

| EC | Total Energy (Fuel) Consumption |

| ED | Energy Consumption due to Velocity Deviations |

| F-DQN | Fuzzy Deep Q-Learning |

| FIS | Fuzzy Inference System |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| MDP | Markov Decision Process |

| NN-MPC | Neural Network Model Predictive Controller |

| PC | Path Curvature (Path Deviation) |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| RRT | Rapidly-Exploring Random Tree |

| SR | Success Rate |

| TLA | Three-Letter Acronym |

| UGV | Unmanned Ground Vehicle |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| USV | Unmanned Surface Vehicle |

| WSM | Weighted Sum Method |

References

- Singh, Y.; Sharma, S.; Sutton, R.; Hatton, D.; Khan, A. A Constrained A* Approach towards Optimal Path Planning for an Unmanned Surface Vehicle in a Maritime Environment Containing Dynamic Obstacles and Ocean Currents. Ocean Eng. 2018, 169, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Liu, Y.; Bucknall, R. Smoothed A* Algorithm for Practical Unmanned Surface Vehicle Path Planning. Appl. Ocean Res. 2019, 83, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Sharma, S.; Sutton, R.; Hatton, D. Optimal Path Planning of an Unmanned Surface Vehicle in a Real-Time Marine Environment Using a Dijkstra Algorithm. In Marine Navigation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-315-09913-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mirjalili, S.; Song Dong, J.; Lewis, A. Ant Colony Optimizer: Theory, Literature Review, and Application in AUV Path Planning. In Nature-Inspired Optimizers: Theories, Literature Reviews and Applications; Mirjalili, S., Song Dong, J., Lewis, A., Eds.; Studies in Computational Intelligence; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 7–21. ISBN 978-3-030-12127-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Guo, F.; Yao, H.; He, S.; Xu, X. Collision Avoidance Planning Method of USV Based on Improved Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 52964–52975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, P.; Du, L. Path Planning Technologies for Autonomous Underwater Vehicles-A Review. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 9745–9768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lin, W.; Chen, A. Path Planning for the Mobile Robot: A Review. Symmetry 2018, 10, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntakolia, C.; Lyridis, D.V. A Swarm Intelligence Graph-Based Pathfinding Algorithm Based on Fuzzy Logic (SIGPAF): A Case Study on Unmanned Surface Vehicle Multi-Objective Path Planning. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntakolia, C.; Lyridis, D.V. A Comparative Study on Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm Approaches for Solving Multi-Objective Path Planning Problems in Case of Unmanned Surface Vehicles. Ocean Eng. 2022, 255, 111418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Savvaris, A.; Tsourdos, A.; Ji, Z. Voronoi-Visibility Roadmap-Based Path Planning Algorithm for Unmanned Surface Vehicles. J. Navig. 2019, 72, 850–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C. Energy-Efficient Path Planning and Control Approach of USV Based on Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2018 MTS/IEEE Charleston, Charleston, SC, USA, 22–25 October 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, H.; Zhu, J. Optimal Path Planning for Unmanned Vehicles Using Improved Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm. In Proceedings of the Neural Computing for Advanced Applications; Zhang, H., Yang, Z., Zhang, Z., Wu, Z., Hao, T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 701–714. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, J.; Zhong, J.; Yang, F.; Cui, Y.; Sheng, J. An Improved Genetic Algorithm for Path-Planning of Unmanned Surface Vehicle. Sensors 2019, 19, 2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, G.; Sun, X.; Xia, X. Multiple Task Assignment and Path Planning of a Multiple Unmanned Surface Vehicles System Based on Improved Self-Organizing Mapping and Improved Genetic Algorithm. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y. Efficient Path Planning Method of USV for Intelligent Target Search. J. Geovis Spat. Anal. 2019, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, H.; You, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, F. The Hybrid Path Planning Algorithm Based on Improved A* and Artificial Potential Field for Unmanned Surface Vehicle Formations. Ocean Eng. 2021, 223, 108709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, D.; Gu, J.; Li, F. A Path-Planning Strategy for Unmanned Surface Vehicles Based on an Adaptive Hybrid Dynamic Stepsize and Target Attractive Force-RRT Algorithm. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Li, B.; Li, S.; Yang, F.; Li, P.; Cui, Y. Particle Swarm Optimization with Orientation Angle-Based Grouping for Practical Unmanned Surface Vehicle Path Planning. Appl. Ocean Res. 2021, 111, 102658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Zhong, J.; Li, S.; Sheng, J.; Cui, Y. Greedy Mechanism Based Particle Swarm Optimization for Path Planning Problem of an Unmanned Surface Vehicle. Sensors 2019, 19, 4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Jin, X.; Er, M.J. A Multilayer Path Planner for a USV under Complex Marine Environments. Ocean Eng. 2019, 184, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Hu, M.; Yan, X. Multi-Objective Path Planning for Unmanned Surface Vehicle with Currents Effects. ISA Trans. 2018, 75, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyridis, D.V. An Improved Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm for Unmanned Surface Vehicle Local Path Planning with Multi-Modality Constraints. Ocean Eng. 2021, 241, 109890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntakolia, C.; Iakovidis, D.K. A Swarm Intelligence Graph-Based Pathfinding Algorithm (SIGPA) for Multi-Objective Route Planning. Comput. Oper. Res. 2021, 133, 105358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiujuan, L.; Zhongke, S. Overview of Multi-Objective Optimization Methods. J. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2004, 15, 142–146. [Google Scholar]

- Gunantara, N. A Review of Multi-Objective Optimization: Methods and Its Applications. Cogent Eng. 2018, 5, 1502242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntakolia, C.; Platanitis, K.S.; Kladis, G.P.; Skliros, C.; Zagorianos, A.D. A Genetic Algorithm Enhanced with Fuzzy-Logic for Multi-Objective Unmanned Aircraft Vehicle Path Planning Missions*. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Dubrovnik, Croatia, 21–24 June 2022; pp. 114–123. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, P.; Zhang, H.; Guo, W.; Liu, Y. Learn to Navigate: Cooperative Path Planning for Unmanned Surface Vehicles Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 165262–165278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, T.; Xiong, G.; Ali, H.; Dong, X.; Han, Y.; Shen, Z. USV Path Planning Under Marine Environment Simulation Using DWA and Safe Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 19th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), Auckland, New Zealand, 26–30 August 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, B.; Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Q. An Algorithm of Complete Coverage Path Planning for Unmanned Surface Vehicle Based on Reinforcement Learning. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chavez-Galaviz, J.; Azizzadenesheli, K.; Mahmoudian, N. Dynamic Obstacle Avoidance for USVs Using Cross-Domain Deep Reinforcement Learning and Neural Network Model Predictive Controller. Sensors 2023, 23, 3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nantogma, S.; Zhang, S.; Yu, X.; An, X.; Xu, Y. Multi-USV Dynamic Navigation and Target Capture: A Guided Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning Approach. Electronics 2023, 12, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, P.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, M. An Optimized Scheduling Scheme for UAV-USV Cooperative Search via Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 20th International Conference on Mobility, Sensing and Networking (MSN), Harbin, China, 12–14 December 2024; pp. 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ren, J.; Cui, Y.; Fu, D.; Cong, J. Multi-USV Task Planning Method Based on Improved Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 18549–18567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gong, C.; Chen, K. Adaptive Control Scheme for USV Trajectory Tracking Under Complex Environmental Disturbances via Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 15181–15196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Nie, Y.; Tang, J.; Zhu, S. A Hybrid Path Planning Algorithm for Unmanned Surface Vehicles in Complex Environment with Dynamic Obstacles. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 126439–126449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Liu, Y.; Bucknall, R. A Multi-Layered Fast Marching Method for Unmanned Surface Vehicle Path Planning in a Time-Variant Maritime Environment. Ocean Eng. 2017, 129, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.; Han, Z.; Zhao, B.; Liu, C.; Wang, X. Global Path Planning for Unmanned Surface Vehicle Based on Improved Quantum Ant Colony Algorithm. Math. Probl. Eng. 2019, 2019, e2902170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harliana, P.; Rahim, R. Comparative Analysis of Membership Function on Mamdani Fuzzy Inference System for Decision Making. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 930, 012029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntakolia, C.; Lyridis, D.V. A n − D Ant Colony Optimization with Fuzzy Logic for Air Traffic Flow Management. Oper. Res. Int. J. 2022, 22, 5035–5053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntakolia, C.; Kladis, G.P.; Lyridis, D.V. A Fuzzy Logic Approach of Pareto Optimality for Multi-Objective Path Planning in Case of Unmanned Surface Vehicle. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2023, 109, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamam, A.; Georganas, N.D. A Comparison of Mamdani and Sugeno Fuzzy Inference Systems for Evaluating the Quality of Experience of Hapto-Audio-Visual Applications. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Workshop on Haptic Audio visual Environments and Games, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 26–27 October 2008; IEEE: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2008; pp. 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bagis, A.; Konar, M. Comparison of Sugeno and Mamdani Fuzzy Models Optimized by Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm for Nonlinear System Modelling. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2016, 38, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, J. Comparative Study of Mamdani-Type and Sugeno-Type Fuzzy Inference Systems for Diagnosis of Diabetes. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Advances in Computer Engineering and Applications, Ghaziabad, India, 19–20 March 2015; IEEE: Ghaziabad, India, 2015; pp. 517–522. [Google Scholar]

| Work | Vehicle Domain | Method | Objectives | Environment | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [27] | USV (single & formations) | Deep RL for cooperative path planning (DQN) | Collision avoidance, path length, formation maintenance, kinematic constraints | Simulation + real harbor data | DRL can compute shortest collision-avoiding paths and maintain formations; applicability to USV formation control and obstacle-dense areas. |

| [28] | USV | Dynamic Window Approach + Safe RL | Obstacle avoidance, safety, path feasibility | Simulation | Combines local DWA motion generation with safe-RL policy for higher-level steering; improved safety in marine simulations. |

| [29] | USV | RL | Coverage completeness, path length, energy proxy | Simulation | Presents RL-based complete coverage planner for USVs; focuses on mission coverage metrics |

| [30] | USV | Cross-domain DRL + NN-MPC hybrid | Dynamic obstacle avoidance, tracking accuracy, collision avoidance | Simulated dynamic obstacles | Hybrid NN-MPC + DRL improves dynamic obstacle avoidance and tracking vs baseline controllers. |

| [31] | Multi-USV | Multi-agent RL | Cooperative navigation, target capture, multi-agent coordination | Simulation | Presents MARL strategies for coordinated capture/navigation; emphasizes cooperation and role assignment among USVs. |

| [32] | USV | Hybrid DRL | Obstacle avoidance, safety, maybe hybrid methods | Simulation | Effective scheduling and path planning under energy constraints |

| [33] | Multi-USV cluster | Value-decomposition network | Task allocation + collision avoidance | Simulated multi-USV ocean observation tasks | Decomposes planning into allocation and avoidance; improved TD error and transfer learning accelerate convergence and safety. |

| [34] | USV | Hybrid-priority Twin-Delayed DDPG | Trajectory tracking, robustness to currents and winds, convergence speed | Realistic marine data with currents and winds | Uses LOS-guided MDP and hybrid-priority replay to enhance robustness and accuracy under time-varying disturbances. |

| This paper | USV | Deep Q-Learning (DQN) and Fuzzy DQN (F-DQN) | Multi-objective path planning under fuel various constraints | Simulation | F-DQN achieves smoother paths, lower fuel use, and faster convergence than baseline DQN; interpretable and energy-aware navigation framework. |

| Fuzzy Rules | Distance | Smoothness | Energy Consumption | Path Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rule 1 | Short | Smooth | Low | Very High |

| Rule 2 | Short | Smooth | Medium | Very High |

| Rule 3 | Short | Adequate | Low | Very High |

| Rule 4 | Moderate | Smooth | Low | Very High |

| Rule 5 | Short | Smooth | High | High |

| Rule 6 | Short | Adequate | Medium | High |

| Rule 7 | Short | Brut | Low | High |

| Rule 8 | Moderate | Smooth | Medium | High |

| Rule 9 | Moderate | Adequate | Low | High |

| Rule 10 | Long | Smooth | Low | High |

| Rule 11 | Short | Adequate | High | Medium |

| Rule 12 | Short | Brut | Medium | Medium |

| Rule 13 | Short | Brut | High | Medium |

| Rule 14 | Moderate | Smooth | High | Medium |

| Rule 15 | Moderate | Adequate | Medium | Medium |

| Rule 16 | Moderate | Brut | Low | Medium |

| Rule 17 | Long | Smooth | Medium | Medium |

| Rule 18 | Long | Smooth | High | Medium |

| Rule 19 | Long | Adequate | Low | Medium |

| Rule 20 | Long | Brut | Low | Medium |

| Rule 21 | Moderate | Adequate | High | Low |

| Rule 22 | Moderate | Brut | Medium | Low |

| Rule 23 | Moderate | Brut | High | Low |

| Rule 24 | Long | Adequate | Medium | Low |

| Rule 25 | Long | Adequate | High | Low |

| Rule 26 | Long | Brut | Medium | Low |

| Rule 27 | Long | Brut | High | Very Low |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value/Range | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| USV velocity | [1.5, 2.5] m/s | Randomized cruising speed | |

| Fuel consumption rate | 2 kg/h | Nominal energy usage | |

| Fuel capacity | 6 kg | Maximum fuel reserve | |

| Number of obstacles | - | [4, 6, 8] | Scenario-dependent |

| Learning rate | 0.001 | Adam optimizer | |

| Discount factor | 0.99 | Future reward discount | |

| Replay buffer | - | 105 experiences | Experience memory size |

| Mini-batch size | - | 64 | Samples per training step |

| Exploration rate | Linear decay schedule | ||

| Episodes per scenario | - | 500 | Training episodes per environment |

| Scenario (# obst.) | Algorithm | Success Rate (%) | Mean Path Length (m) | Mean Smoothness (rad) | Energy Proxy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | DQN | 88.0 | 214.10 | 0.199 | 30.246 |

| F-DQN | 81.3 | 141.65 | 0.065 | 6.637 | |

| 6 | DQN | 82.7 | 208.52 | 0.198 | 29.499 |

| F-DQN | 81.7 | 135.02 | 0.062 | 5.957 | |

| 8 | DQN | 84.7 | 203.21 | 0.192 | 27.614 |

| F-DQN | 82 | 130.75 | 0.064 | 5.794 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bartsiokas, I.A.; Ntakolia, C.; Avdikos, G.; Lyridis, D. Intelligent Multi-Objective Path Planning for Unmanned Surface Vehicles via Deep and Fuzzy Reinforcement Learning. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2285. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122285

Bartsiokas IA, Ntakolia C, Avdikos G, Lyridis D. Intelligent Multi-Objective Path Planning for Unmanned Surface Vehicles via Deep and Fuzzy Reinforcement Learning. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2285. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122285

Chicago/Turabian StyleBartsiokas, Ioannis A., Charis Ntakolia, George Avdikos, and Dimitris Lyridis. 2025. "Intelligent Multi-Objective Path Planning for Unmanned Surface Vehicles via Deep and Fuzzy Reinforcement Learning" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2285. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122285

APA StyleBartsiokas, I. A., Ntakolia, C., Avdikos, G., & Lyridis, D. (2025). Intelligent Multi-Objective Path Planning for Unmanned Surface Vehicles via Deep and Fuzzy Reinforcement Learning. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2285. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122285