Abstract

This paper presents a human-in-the-loop (HiTL) intelligent adaptive control scheme for unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) that accounts for uncertain dynamics, with the goal of effectively monitoring marine pollutants. To tackle the challenges posed by complex aquatic monitoring environments, this approach integrates human intelligence into the navigation strategy of USVs, allowing for superior path planning through human decision-making. Additionally, a potential field-based obstacle avoidance strategy is developed to ensure the safe operation of USVs within this HiTL framework. To address issues related to system uncertainties, we propose a novel adaptive fuzzy control strategy based on convex optimization, which enhances overall control performance. Finally, stability analysis and simulation results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method. The verification results show that compared with traditional adaptive fuzzy controllers, our control strategy effectively reduces control errors.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the growing disparity between social demand and resource supply has led people to focus on the exploration and utilization of marine resources. However, the increase in human activities in the ocean has resulted in severe marine pollution [1,2,3,4]. Incidents such as the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and the Ever Given blockage in the Suez Canal have highlighted the critical importance of preventing marine pollution and protecting the environment. As a result, automated detection technologies for marine pollution have become a significant area of research [5,6,7].

Intelligent USVs, which have emerged alongside advancements in artificial intelligence technologies, represent a new platform for marine monitoring [8,9,10,11,12]. Compared to traditional environmental monitoring vessels, USVs offer several advantages, including lower costs, high autonomy and flexibility, and a wider operational range. These features make them a promising next-generation technology for marine environmental monitoring. However, achieving precise control of USVs in complex marine environments remains a challenging issue. And this challenge mainly comes from the underactuated characteristics of USVs, the uncertain dynamics of the system, and unknown external disturbances. Currently, most USVs are underactuated structures, meaning their control input is less than their degrees of freedom. In [13], a distributed bearing-based formation control scheme with finite-time convergence is proposed for multiple underactuated USVs. By employing a guidance-point-based model transformation method, the dimension of the underactuated tracking error dynamics can be reduced from three to two. In [14], the trajectory tracking problem of underactuated USVs subject to input saturation, unmodeled dynamics, and marine environmental disturbances is investigated. A coordinate transformation is constructed to address the under-actuation issue of USVs, and a new event-triggered condition is introduced to significantly reduce control execution frequency and transmission load. In [15], a robust collision-avoidance formation navigation problem for multiple USVs is addressed, where USVs are modeled as underactuated nonlinear systems subject to state and input constraints. A novel distributed model predictive control (MPC)-based controller is developed to achieve collision-free formation navigation. Furthermore, a class of distributed collision-avoidance formation navigation strategies is proposed and utilized, allowing the control inputs of USVs to be determined synchronously. In [16], a prescribed performance path-following control algorithm for USVs is proposed, which employs an output-based threshold rule and a shift function to perform parallel maritime search tasks. In the guidance module, a finite-boundary-based guidance principle is developed, and a position threshold rule is adopted to avoid continuous computation of heading reference signals.

For unmodeled dynamics or external disturbance issues of USVs, adaptive control strategies or disturbance observers are often used to compensate for system uncertainties [17,18,19]. In [20], an adaptive trajectory tracking control algorithm with guaranteed transient performance is proposed for underactuated USVs. Neural networks are employed to approximate unknown external disturbances and the uncertain hydrodynamic characteristics of the USVs. In [21], the trajectory tracking control problem of underactuated USVs under state and input quantization is investigated. At the dynamic level, a fuzzy adaptive quantized control method based on an event-triggered mechanism is proposed. In [22], the trajectory tracking problem of USVs under unmeasurable velocity and unknown disturbances is investigated. By combining a fixed-time extended state observer and a fixed-time differentiator, a fixed-time sliding mode control law is proposed, in which a saturation function is employed to ensure that the terminal sliding surface avoids the singularity area. In [23], the fixed-time prescribed performance trajectory tracking control of USVs with unknown dynamics and disturbances is investigated. An improved prescribed performance function is introduced to achieve user-defined performance, including both transient and steady-state behaviors of the USVs. In [24], the distributed optimal cooperative control (DOCC) problem of USVs subject to network channel limitations and communication interruptions is investigated. To address the challenges of scarce and intermittent communication channels, an intermittent interlaced periodic event-triggered mechanism is developed in the auxiliary system.

It is important to note that while extensive research has been conducted on control systems for USVs, most existing control strategies depend on predefined trajectories or specified map information to develop corresponding controllers. This method may not be suitable for marine pollution monitoring, as such pollution incidents often occur suddenly and randomly, making their location and extent highly unpredictable. As a result, the distribution of pollutants and other essential information cannot be determined in advance. Given the complexities of the marine environment, current algorithms face significant challenges in effectively monitoring contaminated waters. To tackle the obstacles presented by complex marine environments, we have designed an HiTL control strategy for USVs. The purpose of HiTL is to enhance the system’s adaptability in complex and uncertain environments through the use of human intelligence. In [25], the HiTL control strategy is combined with an improved prescribed performance control method and applied to the cooperative control of unmanned aerial vehicle systems. In [26], the focus is on the consensus tracking control problem of an HiTL unmanned aerial vehicle attitude system subject to external disturbances. The proposed event-based adaptive neural controller ensures finite-time tracking of the attitude systems. In [27], the study, under a directed communication graph, addresses the observer-based HiTL asymptotic consensus control problem for multi-agent ship systems that are also affected by external disturbances. In [28], a human-in-the-loop framework based on deep reinforcement learning is proposed to achieve autonomous dynamic soaring for improving the endurance of fixed-wing unmanned aerial vehicles. In [29], to solve the problem of increased load on teleoperated ground vehicle operators caused by communication delay and low transparency, a human-in-the-loop experiment is conducted to evaluate the ePTGC framework. The results showed that the framework can reduce load and improve stability. Ref. [30] has designed a human-supervised task replanning system for unmanned underwater vehicles in ocean missions, and the effectiveness of the design has been verified through simulation. Ref. [31] proposes a human-in-the-loop backstepping reinforcement learning algorithm (human agent interaction) for nonlinear strict feedback multi-agent systems under unknown fault disturbances, achieving fast convergence and capture control. Ref. [32] proposes a human-in-the-loop collaborative path tracking architecture for marine vehicles with unknown disturbances (human-controlled virtual leader’s path update speed), based on the RED observer and OFCTC method to achieve finite-time path tracking. In summary, under the background of HiTL research, existing work has provided multiple approaches to solving deterministic problems. However, when applied to monitoring marine pollution, the HiTL control strategy may present potential safety issues. This approach often utilizes a joystick-like operation mode for controlling USVs. However, the human operator is usually located far from the actual environment, making it challenging to accurately perceive real-time ocean conditions. Consequently, the operator may lack precise awareness of the vessel’s orientation, velocity, and position, which can lead to operational errors. For instance, during the detection of marine pollutants, USVs are typically required to collect samples along the borders of a contaminated area instead of entering it directly. Unfortunately, because the operator in the remote control center cannot accurately discern the USV’s surrounding environment, the vessel may inadvertently drift into the polluted zone. This could potentially cause disturbances or even damage to the USV. As a result, achieving precise and safe control of USVs under the HiTL mechanism presents a significant challenge, particularly when the system is influenced by uncertain dynamic parameters.

This paper proposes a novel HiTL adaptive fuzzy control strategy for USVs with uncertain dynamics, aimed at achieving effective monitoring of marine pollutants. The effectiveness of the proposed method is validated through both theoretical analysis and simulation results. Compared with existing approaches, the main contributions of this work are as follows.

- 1.

- This paper proposes a novel HiTL intelligent control strategy for USVs used in marine pollution monitoring. Compared with existing methods [33,34,35], the proposed approach leverages human intelligence to better address the challenges of USVs’ navigation and control in complex marine environments, thereby achieving more effective pollutant monitoring. Furthermore, based on the HiTL control framework, a potential field-based obstacle avoidance strategy is designed to achieve effective coordination between autonomous avoidance and manual control, enhancing the security performance of the USVs.

- 2.

- Based on convex optimization theory, this paper designs an adaptive fuzzy control strategy for USVs to effectively compensate for uncertain dynamics. Moreover, a novel adaptive update mechanism is proposed to address the potential issue of excessive parameter growth under the HiTL framework. Compared with existing approaches [36,37,38], the proposed method effectively mitigates the adverse effects of uncertainties on control performance.

2. Model and Problem Statement

2.1. Dynamic Model

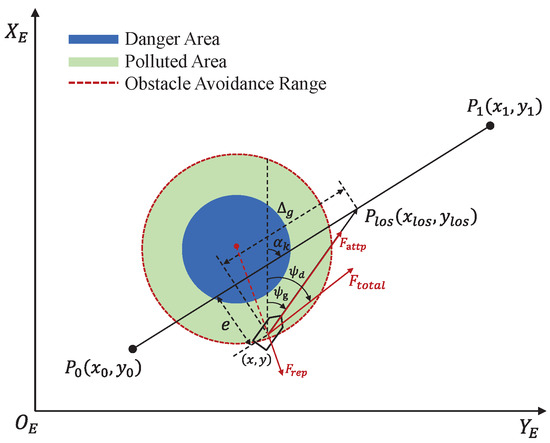

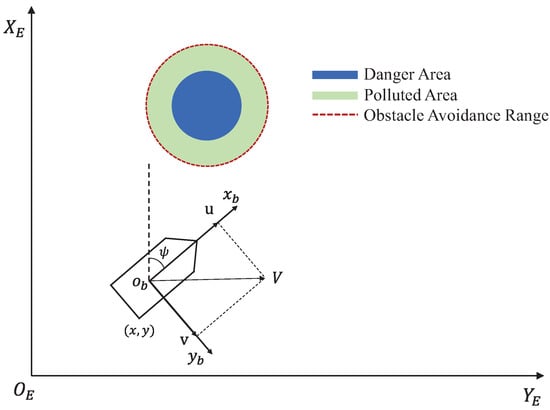

In this section, we describe in detail the three-degree-of-freedom kinematics and dynamics of the underactuated USVs. As shown in Figure 1, two coordinate frames are introduced to describe the USVs motion in planar space, where is the earth-fixed frame and the body-fixed frame. The nonlinear mathematical model of the three-degree-of-freedom (3-DOF) of the USVs is as follows [39]:

where represents the position coordinate of the USVs, and represents the heading angle. u and v represent the surge velocity and sway velocity of the USVs, respectively. r is the heading angular velocity of the USVs. m is the ship mass. , , and represent hydrodynamic added masses. , , and are the linear damping coefficients. represent the second-order nonlinear drag coefficients related to surge velocity, lateral drift speed, and steering speed, respectively. represents the moment of inertia about the vertical axis. and are the control inputs representing surge force and yaw moment, respectively. In this paper, it is assumed that all the dynamic coefficients in Equation (1) are unknown.

Figure 1.

USV coordinate system diagram.

2.2. Control Objective

The objective of this article is to design an adaptive fuzzy control strategy that incorporates human actions for a USV system with highly uncertain and unknown dynamics. By leveraging human intelligence, the USVs can navigate to a designated monitoring area at a specified speed, effectively monitor pollutants, and avoid entering danger zones to prevent potential safety hazards.

This paper discusses the challenges associated with the HiTL adaptive intelligent control strategy in comparison to the existing literature. These challenges are primarily reflected in three key aspects. First, in HiTL control modes, human control actions are often applied suddenly. Unmanned vessels used for environmental monitoring frequently undertake multiple tasks, making it difficult to coordinate current operations with abrupt human actions. Ensuring stable vessel performance in these situations is a significant challenge. The second issue is that operators, under HiTL control, often cannot accurately perceive the vessel’s surroundings in real-time. This leads to delayed interventions, increasing the difficulty of obstacle avoidance and introducing potential safety risks. The third challenge arises from the highly nonlinear and uncertain dynamics of unmanned vessels. Since operators generally control these vessels from a distance, they struggle to fully understand the mechanical characteristics of the hull, which complicates the control process. As far as the author is aware, currently, there are still shortcomings in HiTL control strategies for USVs used for environmental monitoring when addressing certain specific challenges [25,26,27]. This gap in the literature is one of the motivations for this paper.

Assumption 1

([39]). The left and right hull of the unmanned surface vehicle is symmetrical and the mass is even.

Assumption 2

([20]). All the variable states in Equation (1) can be measured by using GPS and IMU modules.

Lemma 1

([40]). Define the continuous unknown function on a compact set Ω. There exists a fuzzy logic system that satisfies the following relation

where is the ideal constant weight vector, and is the basis function vector of the number of fuzzy rules of . is chosen as Gaussian functions, for , where is the center vector and the width of the Gaussian function is .

Lemma 2

(Young’s inequality). For , the following relationship holds:

where , , , and .

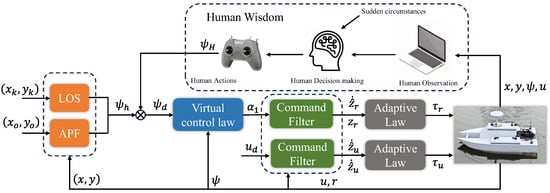

3. Human-in-Loop Control Adaptive Fuzzy Strategy

To achieve coordinated control between sudden human actions and the preset tasks of USVs, this paper proposes a strategy that separates navigation strategies from control methods. The control strategy diagram is shown in Figure 2. It implements decoupling between the control of forward velocity and heading angle for USVs using a Line-of-Sight (LOS) navigation strategy. This effectively addresses the challenge of underactuated control in unmanned vessels. The surge velocity of the USVs is set to a predefined value, while the tracking angle is determined by human actions and the LOS navigation laws. Consequently, the target angle for the USVs is given by

where is defined by human input, while is automatically calculated based on the LOS algorithm.

Figure 2.

Adaptive Fuzzy Human-in-the-loop Control Diagram.

5. System Stability Analysis

In this section, the control performance of the heading angle under our strategy is analyzed based on the Lyapunov stability theorem. Consider the following Lyapunov function

Taking the derivative of V, we have

And then, the boundedness of the term and will be analyzed. For the convenience of analysis, define and For , the following first-order condition of the convex function holds

For and , it can be concluded that

Therefore, the following can be obtained:

For the positive definition function , its derivative is derived as

Using (44), we have

Thus, the boundedness of is proven, which illustrates that the fuzzy logic system is able to approximate the uncertain function . So, and , where and are bounded normal numbers. According to Lemma 2 and (42), is rewritten as

In (48), , . In order to ensure the positive definiteness of a, the control parameters need to meet the following conditions: . Thus, one can obtain

According to (49), is bounded by . Therefore, all the error variables in the system are ultimately bounded.

Remark 1.

It is important to note that in this article, human actions do not directly control the USVs’ movements, specifically the torque. Instead, human control is achieved by adjusting the desired heading angle of the USVs. This approach aligns more closely with human operational habits compared to existing methods [32]. Additionally, we implement a LOS navigation strategy based on the potential field method, which helps mitigate potential safety risks associated with human actions.

Remark 2.

The formula presented introduces an adaptive learning strategy that is based on input saturation. Under this control strategy, if the control torque exceeds a specified saturation value, our adaptive method ceases training the fuzzy system. This strategy effectively minimizes the negative impact of excessive control inputs on performance, in contrast to what is found in the existing literature [41,42]. Furthermore, we develop the adaptive law for the fuzzy system using convex optimization rather than the Lyapunov method, which reduces the coupling within the entire controller. Compared to other adaptive intelligent control strategies [43,44,45], the separate design approach outlined in this paper simplifies the controller’s complexity and facilitates easier parameter tuning.

6. Method Validation and Analysis

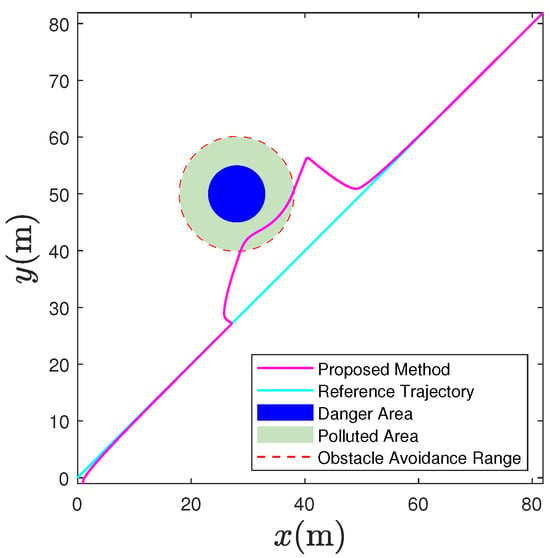

In this section, we conduct simulation experiments to verify the feasibility of the proposed adaptive fuzzy control strategy. The USV model chosen for this test is based on the work of [46]. The model parameters are shown in Table 1. The expected speed of the USV is set to 0.5 m/s, with an initial position of (1, −1) and an initial speed of 0. The waypoints for the reference path are set at (0, 0) and (80, 80). We have designated a blue danger zone with a radius of 5 m, centered around the coordinates (28, 50), and a circular green pollution zone that extends 5 m beyond the danger zone. The fuzzy system nodes for both the velocity and heading angle subsystems consist of 11 nodes, with the center points of the Gaussian functions evenly distributed within the range of and a width of 0.5. The initial fuzzy weights are all 0. The control parameters are , , , , , , , , , , , , , .

Table 1.

Model parameters of USVs.

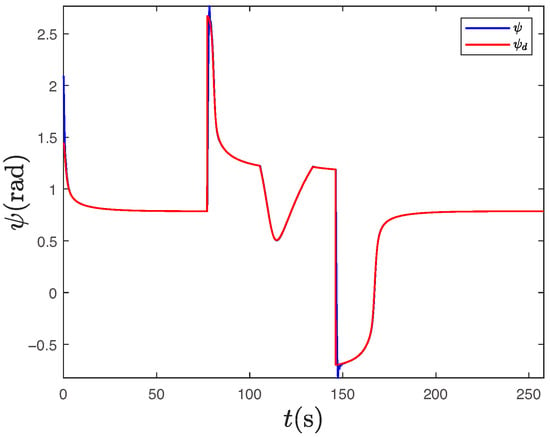

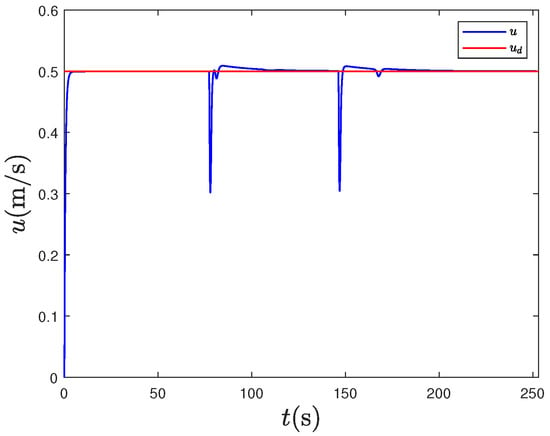

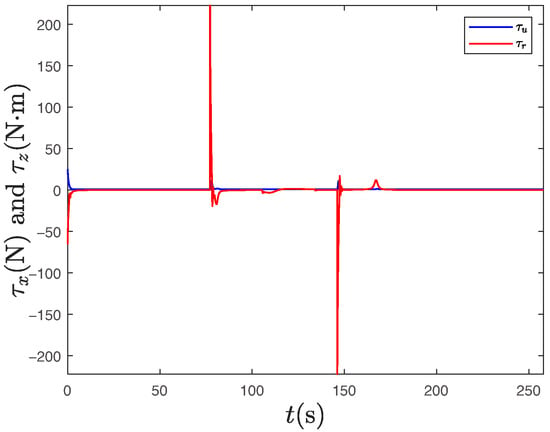

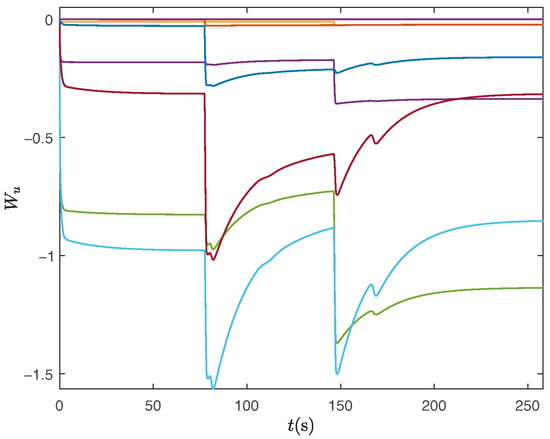

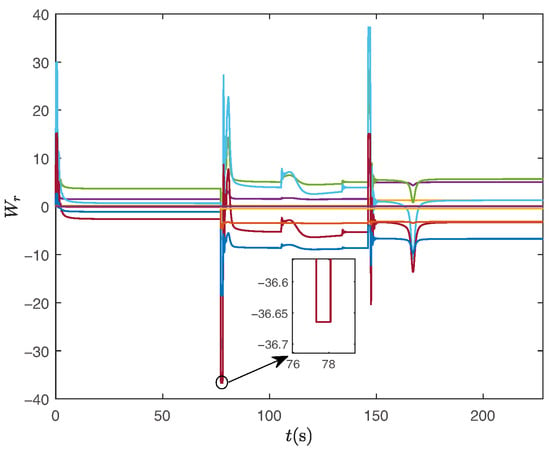

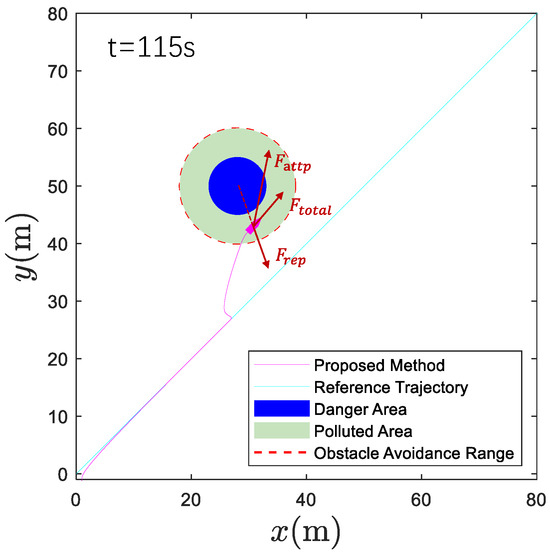

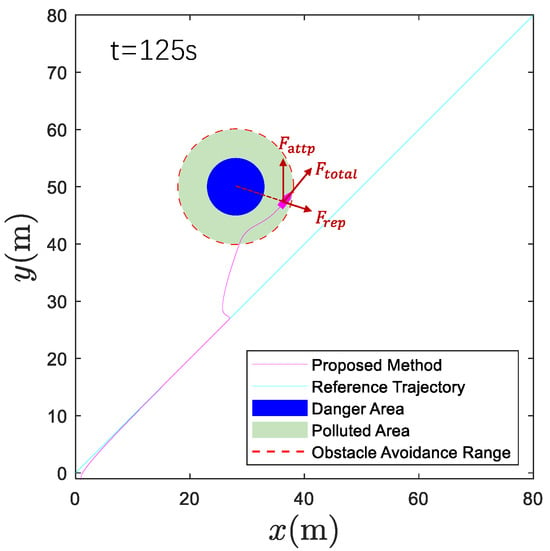

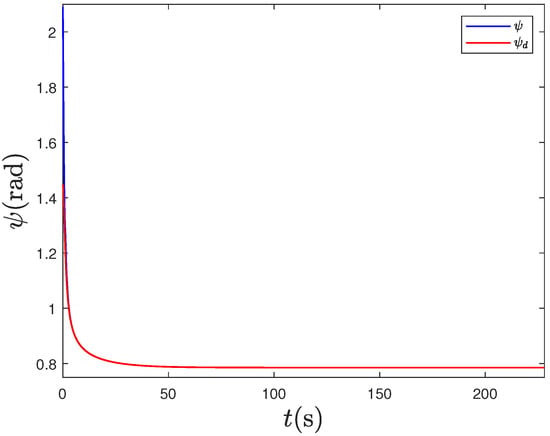

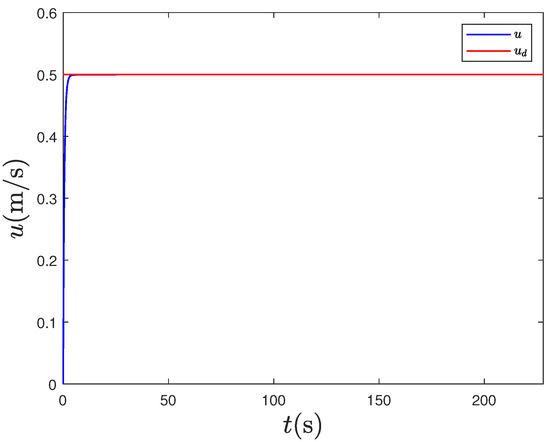

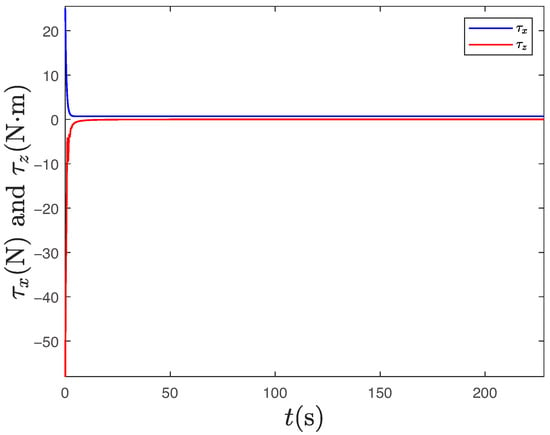

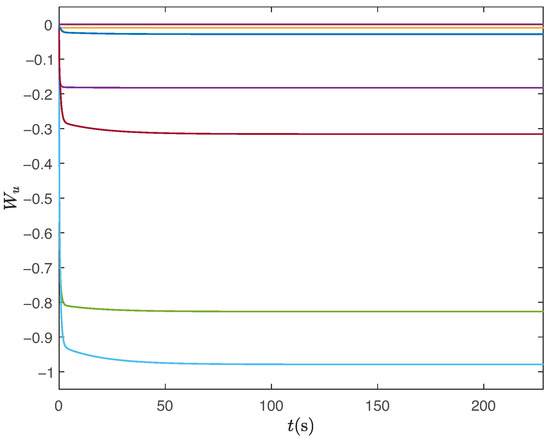

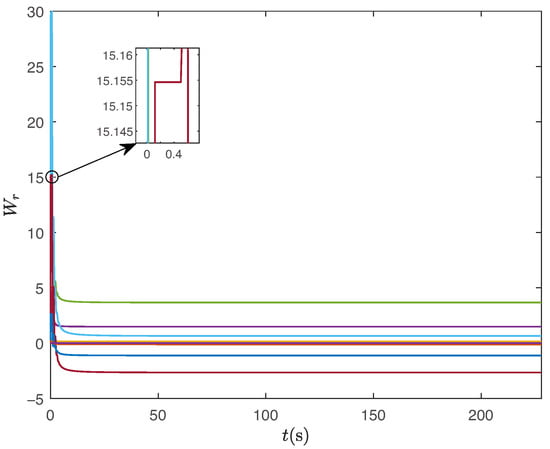

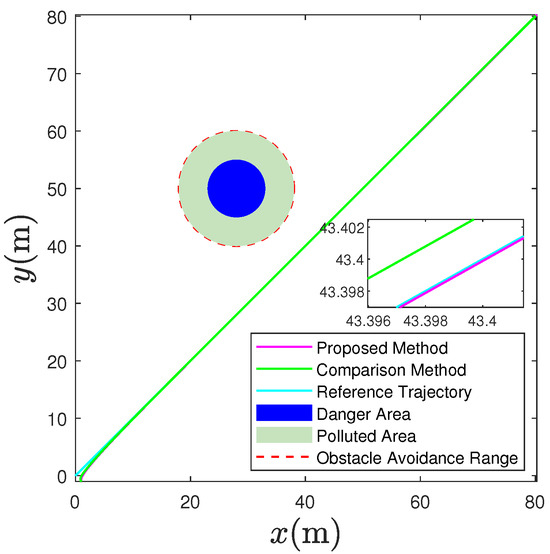

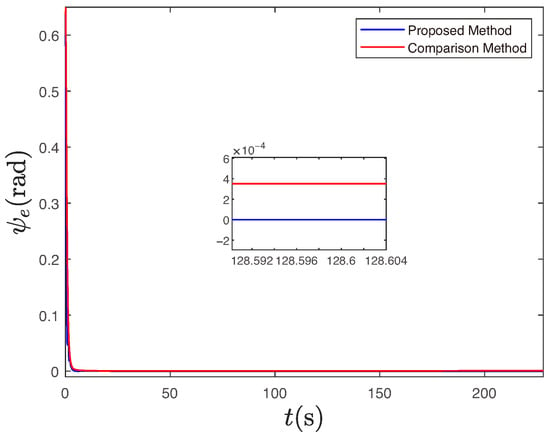

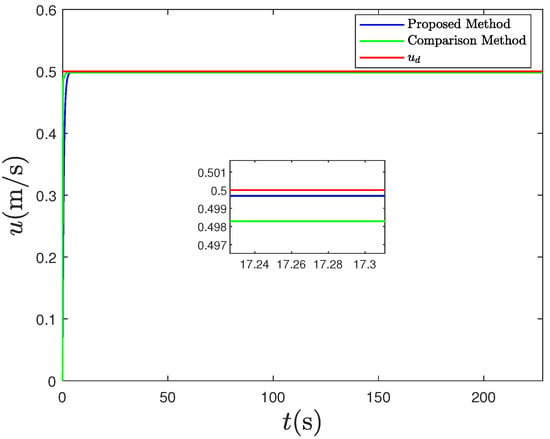

To validate the performance of our algorithm, we conduct simulation experiments across various scenarios. Firstly, we present the performance curve of the unmanned ship control system with the participation of human intelligence The validation results are illustrated in Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9. Figure 4 displays the global path diagram, while Figure 5 and Figure 6 present the dynamic curves for the heading angle and surge velocity, respectively. Figure 7 shows the control input curve of the USVs and Figure 8 and Figure 9 depict the fuzzy weight curves for the velocity and heading angle subsystems. As illustrated in Figure 4, human intervention occurs at 75 s to enable the USVs to enter the contaminated area for environmental monitoring. At this point, there is a significant shift in the expected heading angle, prompting the controller to quickly adjust and guide the USVs to track the desired heading angle. Figure 5 and Figure 6 demonstrate that effective tracking of both speed and angle is still maintained following human intervention. As shown in Figure 5, when human intervention occurs at t = 75 s, the heading angle controller exhibits excellent tracking performance. Quantitative analysis shows that the rise time of the system is 2.1 s, the adjustment time is 4.5 s, and the overshoot is only 3.8%. At about 108 s, the USVs enter the contaminated area and detect obstacles. Thanks to the APF algorithm, the USV is able to navigate around these obstacles autonomously, ensuring the safe continuation of the detection task without human intervention. After exiting the contaminated area, the USVs resume their original path without further human interference. During the obstacle avoidance process, Figure 8 and Figure 9 illustrate that the adaptive fuzzy strategy continuously learns to adapt to changing angles. Our adaptive law only relies on the system information at the current moment; therefore, it has the advantage of low computational complexity. On a PC equipped with an i5-8500 processor (Lenovo Group Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), the running time of our controller in MATLAB (version R2023b) is less than 0.01 s. Additionally, it is observed in Figure 7 and Figure 9 that the adaptive strategy ceased updating at both 52 s and 152 s. This occurs because our proposed adaptive strategy effectively prevents excessive parameter growth, which helps mitigate the negative effects of overly adaptive parameters on the system under the human-in-the-loop control strategy.

Figure 4.

Path curve with human intervention.

Figure 5.

Heading angle curve with human intervention.

Figure 6.

Surge velocity curve with human intervention.

Figure 7.

Control input with human intervention.

Figure 8.

Surge velocity subsystem weight with human intervention.

Figure 9.

Heading angle subsystem weight with human intervention.

To further analyze the performance of the controller during obstacle avoidance, we select two critical moments in the obstacle avoidance process for detailed examination. In Figure 10, we observe that as the USV enters the avoidance radius of the polluted area, the obstacle avoidance maneuver is automatically initiated through the APF algorithm. The sudden change in the heading angle command results in a smooth but significant adjustment in the USV’s trajectory, demonstrating the rapid response capability of our control system. In Figure 11, we can see that when the USV has successfully navigated around the core hazardous zone, it begins to return toward the original desired path while maintaining a safe distance from the polluted area. These two figures collectively illustrate that the guidance algorithm has successfully executed the obstacle avoidance function, while the control algorithm effectively tracks the abrupt angle changes that occur during this process, thereby verifying the effectiveness of our proposed APF-based navigation strategy.

Figure 10.

The avoidance trajectory (115 s).

Figure 11.

The avoidance trajectory (125 s).

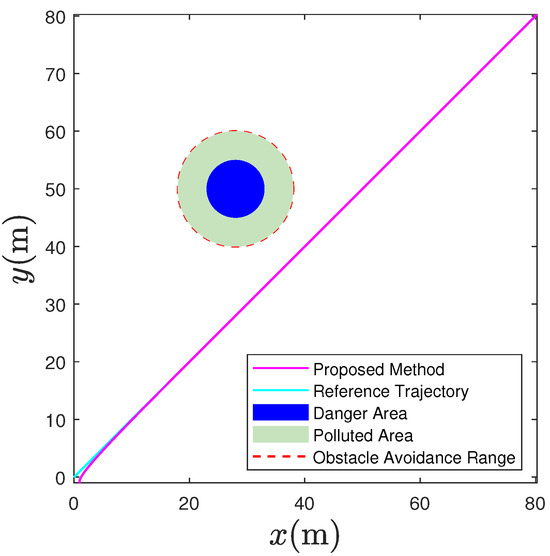

Under the same control parameters, we simulate the tracking of the expected path without human intervention. The experimental results are presented in Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17. Figure 12 illustrates the tracking path of the unmanned surface vehicles, demonstrating their effective tracking of the expected route. Figure 13 and Figure 14 depict the tracking of the heading angle and surge velocity. Notably, there are significant tracking errors during the initial stage. However, as adaptive parameters are trained, the tracking error decreases rapidly. Figure 15 shows the curve of the control input signal. Meanwhile, Figure 16 and Figure 17 illustrate the changes in fuzzy weights. It is evident that as the tracking error diminishes, both the velocity weight and heading angle weight remain within a specific range. By comparing the two results above, it is clear that human intelligence can enhance the performance of unmanned ships in functions like ocean environment monitoring. Additionally, our design approach, which separates navigation from control, effectively minimizes the impact of human actions on the stability of these unmanned vessels. The verification results demonstrate that the control strategy proposed in this paper ensures the stability of unmanned ships, whether human actions are introduced or removed.

Figure 12.

Path curve without human intervention.

Figure 13.

Heading angle curve without human intervention.

Figure 14.

Surge velocity curve without human intervention.

Figure 15.

Control input without human intervention.

Figure 16.

Surge velocity subsystem weight without human intervention.

Figure 17.

Heading angle subsystem weight without human intervention.

To demonstrate the advantages of our control strategy, we compare our controller with the traditional adaptive fuzzy control strategy in reference [47]. The control parameters used in reference [47] are the same as those in our controller. The comparison results are shown in Figure 18, Figure 19 and Figure 20, and the system performance metrics are shown in Table 2. Our method outperforms the compared methods in both speed control and angle control. For speed control, the value of MAE in our controller is only , while the one in the comparison method is . In the angle control subsystem, our proposed method reduces the value of MAE from to when compared to traditional methods.

Figure 18.

Path tracking of two strategies.

Figure 19.

The heading angle variation curves of two strategies.

Figure 20.

The surge velocity curves of two strategies.

Table 2.

Comparison of tracking performance between two strategies.

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed control strategy, Table 3 compares and analyzes this method with other mainstream control strategies from four key dimensions. From Table 3, it can be seen that this comparison highlights the good balance achieved by our method between model independence, environmental adaptability, safety, and real-time performance, verifying its practical value and comprehensive advantages in complex marine environment monitoring tasks.

Table 3.

Comparison Performance Benchmark Table of Control Methods.

7. Conclusions

A new type of adaptive fuzzy control strategy based on human-in-the-loop is proposed to solve the navigation and control problems of USVs for environmental monitoring in complex sea conditions. An intelligent control strategy based on convex optimization is proposed to solve uncertain dynamic problems in USVs, and the potential field method is introduced into the HiTL control strategy to ensure the safe operation of USVs. The verification results indicate that with the help of human intelligence, the proposed control strategy can effectively complete the monitoring of marine pollution and overcome the impact of uncertain dynamic problems on control performance. It is important to note that this article did not address the issues of ocean pollutant movement and communication delays, which could result in potential performance degradation. In the future, we aim to develop an HiTL control framework that is resilient to communication delays in order to tackle the obstacle avoidance control problem faced by unmanned ships when encountering moving obstacles.

Author Contributions

Methodology, J.L. (Jiaang Liu); Validation, J.L. (Jiaang Liu); Formal analysis, J.L. (Jiaang Liu), S.L. and J.L. (Jiapeng Liu); Resources, J.L. (Jiapeng Liu); Writing—original draft, J.L. (Jiaang Liu); Writing—review & editing, J.L. (Jiapeng Liu), S.L., T.L. and B.D.; Visualization, J.L. (Jiaang Liu) and T.L.; Project administration, J.L. (Jiapeng Liu); Funding acquisition, J.L. (Jiapeng Liu) All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by Systems Science Plus Joint Research Program of Qingdao University (Grant No. XT2024202), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62303255) and the Team Plan for Youth Innovation of Universities in Shandong Province (Grant No. 2023KJ222).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Demopoulos, A.W.J.; Bourque, J.R.; Cordes, E.; Stamler, K.M. Impacts of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on deep-sea coral-associated sediment communities. Mar. Ecol. Prog. 2016, 561, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, S.; Dorgan, K.; Kiskaddon, E.; Bell, S.; Gadeken, K.J.; Clemo, W.C.; Keller, E.L.; Caffray, T. Shallow infaunal responses to the Deepwater Horizon event: Implications for studying future oil spills. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 950458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, S.B.; Roziqin, A.; Ahmad, A.; Ahmad, M.M.; Alfanda, B.D.; Pambudi, D.S.A.; Said, N.S.M.; Abdul, P.M.; Imron, M.F. Tackling marine pollution in the blue economy: Synergies between wastewater treatment technologies and governmental policies. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2026, 222, 118627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Sánchez, M.E.; Montoya-Morales, J.R.; Valencia-Palomo, G.; Hernández-González, O. Robust IDA-PBC for non-separable PCH systems under time-varying external disturbances. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 3499–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Li, Y.; Qin, M.; Liu, B. A marine oil spill detection framework considering special disturbances using Sentinel-1 data in the Suez Canal. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 208, 117012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y. YOLO11-YX: An efficient algorithm for marine debris target detection. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 221, 118511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-Sánchez, M.E.; Hernández-González, O.; Lozano, R.; García-Beltrán, C.D.; Valencia-Palomo, G.; López-Estrada, F.R. Energy-Based Control and LMI-Based Control for a Quadrotor Transporting a Payload. Mathematics 2019, 7, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Hu, S.; Yang, Z.; Wu, G. HAUV-USV Collaborative Operation System for Hydrological Monitoring. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmakis, O.; Degani, A. USV Port Oil Spill Cleanup Using Hybrid Multi-Destination RL-CPP. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 122722–122735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. Research on Intelligent Collision Avoidance Decision-Making Algorithm for Multi-Unmanned Surface Vehicles (USVs) Based on COLREGs. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 168420–168432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Liu, J.; Sun, C.; Dai, B. Convex Optimization-Based Adaptive Neural Network Control for Unmanned Surface Vehicles Considering Moving Obstacles. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chu, S.; Jin, X.; Zhang, W. Composite Neural Learning Fault-Tolerant Control for Underactuated Vehicles with Event-Triggered Input. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 51, 2327–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Huang, B.; Jin, M.; Zhu, C.; Zhuang, J. Distributed finite-time bearing-based formation control for underactuated surface vessels with Levant differentiator. ISA Trans. 2024, 147, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Du, J.; Li, J. Adaptive finite-time trajectory tracking event-triggered control scheme for underactuated surface vessels subject to input saturation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 8809–8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, G.; Lam, J.; Fu, J.; Wang, S. Distributed MPC-based robust collision avoidance formation navigation of constrained multiple USVs. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 1804–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Cabecinhas, D.; Pascoal, A.M.; Zhang, W. Prescribed performance path following control of USVs via an output-based threshold rule. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 73, 6171–6182. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Liu, J.; Yu, J.; Sun, C. Adaptive neural network-based obstacle avoidance control for USVs with uncertain dynamics. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 332, 121390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yao, M.; Chu, S.; Zou, Z. Composite neural learning event-triggered control for dynamic positioning vehicles with the fault compensation mechanism. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 252, 111108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Delfín, J.; García-Beltrán, C.; Guerrero-Sánchez, M.; Valencia-Palomo, G.; Hernández-González, O. Modeling and Passivity-Based Control for a convertible fixed-wing VTOL. Appl. Math. Comput. 2024, 461, 128298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Cui, R.; Yang, C.; Yan, W. Adaptive neural network control of underactuated surface vessels with guaranteed transient performance: Theory and experimental results. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 4024–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Ma, Y.; Li, T.; Chen, C.L.P.; Tong, S. Event-triggered based trajectory tracking control of under-actuated unmanned surface vehicle with state and input quantization. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 3127–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Qiu, B.; Liu, L.; Yang, Y. Global fixed-time trajectory tracking control of underactuated USV based on fixed-time extended state observer. ISA Trans. 2023, 132, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wu, C.; Stojanovic, V.; Song, S. 1 bit encoding-ecoding-based event-triggered fixed-time adaptive control for unmanned surface vehicle with guaranteed tracking performance. Control Eng. Pract. 2023, 135, 105513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Peng, H.; Zhang, C.; Ahn, C.K. Distributed optimal coordinated control for unmanned surface vehicles with interleaved periodic event-based mechanism. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 18073–18086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liang, H.; Pan, Y.; Li, T. Human-in-the-loop consensus tracking control for UAV systems via an improved prescribed performance approach. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 8380–8391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Li, H.; Ahn, C.K.; Yao, D. Event-based finite-time neural control for human-in-the-loop UAV attitude systems. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 10387–10397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhu, F.; Zhao, X. Human-in-the-loop consensus control for multiagent systems with external disturbances. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 11024–11034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xie, F.; Ji, T. Human-in-the-loop reinforcement learning for dynamic soaring: A trajectory planning and control integrated system. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 157, 111219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhao, A.; Zhao, F.; Wu, W. A Human-in-the-Loop Study of Eye-Movement-Based Control for Workload Reduction in Delayed Teleoperation of Ground Vehicles. Machines 2025, 13, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Wang, J.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Z.; Yu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, H. Man-in-the-Loop Control and Mission Planning for Unmanned Underwater Vehicles. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhao, J.; Chi, P.; Wang, Y. Resilient Human-in-the-Loop Containment of Multiagent Systems Against Actuator Fault Attack Based on Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Syst. J. 2025, 19, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Gu, N.; Wang, D.; Han, B.; Peng, Z. Human-in-the-Loop Coordinated Path Following of Marine Vehicles Based on Continuous Twisting Control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Mu, J.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y.; Cajo, R. Heading control of USV based on fractional-order model predictive control. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 322, 120476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, X. Data-driven model predictive control for underactuated USV path tracking with unknown dynamics. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 333, 121457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, X.; Miao, Z. Cooperative trajectory tracking control of USV-UAV with non-singular sliding mode surface and RBF neural network. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 337, 121872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.X.; Ding, Y.; Tahsin, T.; Atilla, I. Adaptive neural network and extended state observer-based non-singular terminal sliding modetracking control for an underactuated USV with unknown uncertainties. Appl. Ocean. Res. 2023, 135, 103560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Wu, S.; Liu, W.; Yang, X.; Du, Z.; Xue, W. Adaptive neural synergetic heading control for USVs with unknown dynamics and disturbances. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 300, 117438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Tong, S. Adaptive neural optimal tracking control for uncertain unmanned surface vehicle. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 312, 119031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Garcia, A.; Castañeda, H. Guidance and Control Based on Adaptive Sliding Mode Strategy for a USV Subject to Uncertainties. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2021, 46, 1144–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ma, J.; Zhao, X.; Niu, B.; Chen, M.; Wang, W. Adaptive Fuzzy Fixed-Time Control for High-Order Nonlinear Systems with Sensor and Actuator Faults. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 31, 2658–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, Y.; Bucknall, R. A Robust Localization Method for Unmanned Surface Vehicle (USV) Navigation Using Fuzzy Adaptive Kalman Filtering. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 46071–46083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Mu, D.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y. Fixed-time fuzzy formation control for underactuated surface vehicles based on a novel trajectory-guiding strategy under model uncertainties. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 327, 120715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Teng, F.; Li, T.; Sun, Q. Adaptive Prescribed-Time Tracking Control for an Unmanned Surface Vehicle Considering Motor-Driven Propellers. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 1665–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Yuan, X.; Yang, B.; Zhao, X. Event-Triggered Trajectory Tracking Control for Unmanned Surface Vessels with Prescribed Performance Using Barrier Lyapunov Functions. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2025, 33, 1466–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Yu, J. Finite-time command-filtered autonomous docking control of underactuated unmanned surface vehicles with obstacle avoidance. ISA Trans. 2025, 164, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ni, G.T. Event-Triggered Asymptotic Tracking Control of Underactuated Ships with Prescribed Performance. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Liu, J.; Yu, J. Improved adaptive fuzzy control for unmanned surface vehicles with uncertain dynamics using high-power functions. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 312, 119168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).