Abstract

Unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) are equipped with numerous sensors, and data is transmitted through networks. Attackers may remotely compromise unmanned surface vehicle (USV) systems and commit criminal acts via networks, causing USVs to deviate from their intended course or pose a collision risk. Although significant research efforts have focused on developing attack detection and defense technologies for USVs, less attention has been paid to the offensive perspective—particularly the design and modeling of novel attack strategies. In this paper, we investigate the potential attack locations of USVs equipped with distributed navigation, guidance, and control modules. We propose a series of novel attack methods designed to compromise the navigation safety of USVs. These methods compromise the control system by blocking, modifying, and delaying navigation data to manipulate the navigation routes of USVs. Ultimately, the simulation results demonstrate the effectiveness of these attacks on the navigation of USVs.

1. Introduction

Ships navigating maritime environments face numerous hazards and challenges, including grounding, collisions, course deviation, and other dangers that can lead to economic losses and environmental disasters. According to a report released by the European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA) [1], there were a total of 2510 maritime casualties and accidents in 2022, resulting in 597 people injured (83.8% of the injured were crew members) and 38 fatalities (65.8% of the deceased were crew members). Among the ships involved, six were reported missing, 524 were damaged, 180 were deemed unfit for further operation, 603 required onshore assistance, 330 needed towing, and 17 were abandoned.

Investigations reveal that human factors contribute to approximately 80.7% of maritime casualties [1]. To mitigate human-factor accidents, the maritime industry is undergoing an intelligent transformation, with USV technology emerging as a pivotal pathway to enhancing maritime safety. A USV is a surface robot capable of independent navigation and task execution on water [2]. USVs offer numerous advantages, including autonomy, intelligence, diversified applications, energy conservation, environmental protection, flexibility, and scalability. USVs can be equipped with various payloads to perform high-risk and labor-intensive tasks unsuitable for manned ships [3]. Currently, USVs are widely deployed in various fields, including ocean transportation, scientific exploration, maritime rescue, maritime cruising, and environmental monitoring [4].

The control system of a USV integrates a variety of embedded devices, collectively forming a complex CPS [5]. The system comprises core control and computing units, multi-source perception systems, high-precision navigation systems, heterogeneous communication data transmission systems, propulsion and actuating mechanisms, energy and power management systems, and various mission payloads. Any anomaly in control logic, whether due to malicious attacks or internal failures, may lead to erroneous commands, course deviation, mission failure, or even catastrophic outcomes such as collisions and shipwrecks, inflicting severe damage to the entire USV platform. Real-world incidents underscore these threats, as seen in [6,7,8].

While most existing USV cybersecurity research focuses on low-cost passive defense and detection, such methods are often insufficient to prevent and reliably detect attacks. We argue that investigating attack methods is not only beneficial but necessary for developing robust USV security frameworks. To effectively defend against attacks, researchers must first understand the adversaries’ attack methodologies from their perspective. This paper fills the identified gap by systematically exploring the offensive side of USV security.

We present five potential attack locations within a USV’s Navigation, Guidance, and Control (GNC) architecture and propose four novel position-spoofing attacks capable of diverting USVs from their intended courses. These methods involve blocking, modifying, delaying, and manipulating position data transmitted among GNC modules. We provide detailed analyses of the attack process and theoretical impacts and validate the effectiveness through simulations. This work aims to support USV designers, researchers, and operators in understanding potential threats and developing effective countermeasures. The contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- We present and analyze five key network attack surfaces in USVs, providing a clear threat model for designers and security researchers.

- We propose four novel position spoofing attacks capable of compromising both encrypted and unencrypted data channels, providing a basis for testing defense mechanisms.

- We elucidate the mechanisms underlying these attacks and provide analytical evidence to demonstrate the impact on the safe navigation of USVs.

- We verify that the proposed attack methods are effective against USVs and can significantly reduce offset errors. The results confirm the feasibility of these attack methods and demonstrate the potential to disrupt USV navigation.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 3 introduces the mathematical model, the control framework, and the network of USVs. Section 4 introduces the possible attack locations of USVs. Based on this, we design four position-spoofing attack methods against USVs and introduce the techniques used in these attacks. Next, we analyze the impact of these attacks on USVs. Section 5 presents simulations of USVs under these attacks. Section 6 analyzes the simulation results and discusses the practical significance of this study. Finally, Section 7 concludes this paper and provides prospects for future research on USV network security.

2. Related Work

This section systematically surveys the current landscape of USV security research. We focus on peer-reviewed literature from the past decade that addresses core vulnerabilities and defense strategies in maritime Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS), with particular emphasis on studies that demonstrate practical implementations or novel theoretical models for attacks and defenses in unmanned system networks. Following this methodology, the existing research can be categorized into the following key areas.

2.1. Defense Mechanisms for CPS and Unmanned Systems

In recent years, significant research efforts have been devoted to enhancing the security of CPS and unmanned systems. The authors of [9] propose the Orpheus system, which combines Control Flow Integrity (CFI) with Data Flow Integrity (DFI) to provide runtime anomaly detection and security recovery mechanisms for embedded control programs, thereby effectively defending against control-flow attacks. Focusing on a hardware-oriented approach, the authors of [10] propose an ideal defense criterion against sensor conversion attacks, namely the Golden Reference, which redesigns the intelligent converter from the physical structure level of the sensor through a collaborative design of hardware and software. Similarly, the authors of [11] design a low-complexity defense method against electromagnetic interference injection into sensors, which uses electromagnetic shielding and signal correction techniques to detect and correct injection attacks on pressure sensors. To enable secure communication, the authors of [12] propose a lightweight framework for underwater acoustic channels, accounting for high latency, low bandwidth, and openness. Furthermore, the authors of [13] propose a novel role-based access control framework for USVs in complex task environments and, based on this, construct a Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) security model suitable for the remote operation of USV clusters.

2.2. Analysis of Maritime Cybersecurity Threats

Understanding the broader threat landscape is important for securing maritime systems. The authors of [14] present a systematic study on cybersecurity threats in the maritime field, focusing on the three core security attributes of maritime information systems: confidentiality, integrity, and availability, and analyze the cybersecurity risks and potential impacts. Beyond these, the authors of [15] survey USV’s network information security technology, outlining how adversaries may exploit various technological weaknesses to compromise unmanned systems using methods such as Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) attacks, Denial of Service (DoS) attacks [16], replay attacks, and physical attacks, which can result in damage, data leakage, and loss of operational control. For instance, the authors of [17] demonstrate how Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) communication network vulnerabilities can be exploited via real-world MITM attacks. The authors of [18] evaluate the operational impact of DoS attacks on commercial USVs, showing that such attacks can severely degrade performance and even cause system crashes. The authors of [19] propose a range-Doppler replay attack against orthogonal frequency division multiplexing-based integrated sensing and communication systems, creating false targets that compromise sensing and threaten autonomous vehicle safety.

2.3. GPS Spoofing and Jamming Attacks

A primary attack vector against USV navigation systems is the disruption of Global Positioning System (GPS) signals. The authors of [20] provide a foundational analysis of GPS spoofing threats and proposed cryptographic authentication as a potential countermeasure. The authors of [21] experimentally validate the vulnerability of UAVs to civil GPS spoofing. The authors of [22] investigate the impact of GPS spoofing on USV path planning and propose using low-cost software-defined radio to launch GPS attacks on USVs. The authors of [23] use a portable, low-cost software-defined radio platform to transmit GPS jamming and spoofing signals, thereby preventing the reception of GPS signals.

2.4. Countermeasures Against Navigation Attacks

In response to the threats, numerous detection and defensive strategies have been proposed specifically for navigation systems. The authors in [24] propose a memory-based event-triggered path-tracking controller that accounts for signal non-transmission caused by DoS attacks during the event-triggering interval, thereby mitigating the adverse effects of DoS attacks on USVs. The authors in [25] propose a Jamming Aware Artificial Potential Field (JA-APF) method. The JA-APF method replans the USVs’ paths based on the GPS jammer’s location, enabling them to move away from the jammer quickly. The authors in [26] propose a periodic event-triggered adaptive neural tracking control scheme for USVs under replay attacks. This scheme enables USVs to force their trajectories to follow the reference trajectory even under the influence of replay attacks. The authors in [27] propose a deep-ensemble-learning method using path loss and MLP networks to detect UAV GPS spoofing via cellular networks. The authors of [28] propose a novel method to enhance the network security resilience of autonomous ship navigation systems from within the system, leveraging multimodal sensor fusion and machine learning to detect and counter GNSS spoofing effectively. Lastly, the authors of [29] conduct an in-depth study on the injection attack of adversarial waypoint AIS against the collision avoidance system of autonomous surface vessels at sea.

While significant research efforts have been devoted to USV cybersecurity, a clear gap remains in the literature. Existing work is predominantly focused on defense mechanisms and detection technologies. Furthermore, the offensive perspective, particularly the proactive design, modeling, and simulation of novel attack strategies within the USV’s GNC framework, has received less attention. Most existing research focuses on low-cost passive defense and detection, which is often insufficient for preemptively identifying and mitigating novel threats.

3. The System of USVs

To establish the foundation for our cybersecurity analysis and attack modeling, this section delineates the core components of a typical USV’s navigation and control system. We focus specifically on three key factors that enable the proposed position spoofing attacks: the mathematical motion model, the distributed GNC architecture, and the underlying network.

3.1. The Mathematical Model of USVs

The kinematic and dynamic model of a USV is important for understanding the effects of cyber attacks on its physical behavior. Attacks that manipulate sensor data ultimately lead to erroneous control commands, and this model governs the physical impact. The research on navigation control of USVs is based on the ship kinematic model [30,31], a mathematical model that describes the motion state and dynamic changes of USVs, as shown below.

where is a position vector, is the position of USVs, is the heading of USVs, is a velocity vector, u is a surge velocity, v is a sway velocity, r is a yaw velocity, is a rotation matrix, is a positive definite symmetric inertia matrix, is an acceleration vector, is a coriolis term matrix, is a damping matrix, is a propulsion force provided by a USV, is a surge force, is a sway force, is a yaw force, and d is an unknown external disturbance vector. USVs navigate on the sea surface by controlling their propellers and may encounter various waves at different velocities and heading angles, resulting in 6 degrees of freedom. Therefore, the USV motion model can adopt the kinematic model of ship motion. The mathematical formula for USVs shows that the key factors controlling their motion are velocity and position. The motion of the USV is controlled by manipulating its propellers and rudder based on this data.

This mathematical model controls the physical impact of cyber attacks. Any manipulation of position () or velocity (v) data through spoofing attacks will result in incorrect control commands (), ultimately causing the USV to deviate from its predetermined trajectory.

3.2. The Control Framework of USVs

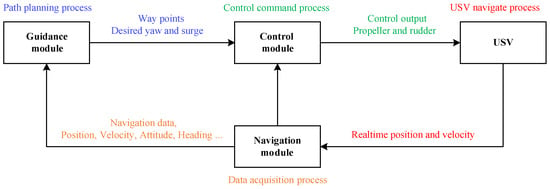

Based on the mathematical model of USVs, we know that a USV is a typical underactuated surface motion vehicle. Generally, the motion control module of a USV consists of three independent parts: guidance, navigation, and control [32]. To ensure navigation safety, the guidance module of a USV integrates multiple sensors, including a GPS receiver and an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), to acquire real-time environmental data and estimate navigation state parameters. The guidance module performs path planning based on the navigation system’s estimated data and generates a safe path. The path consists of a series of waypoints, and the USV navigates along these waypoints. The control module ensures the USV navigates along these waypoints by allocating appropriate thrust to the propulsion and the appropriate steering angle to the steering system. Based on [32], we summarize the USV’s motion control module framework, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The motion control module framework of USVs.

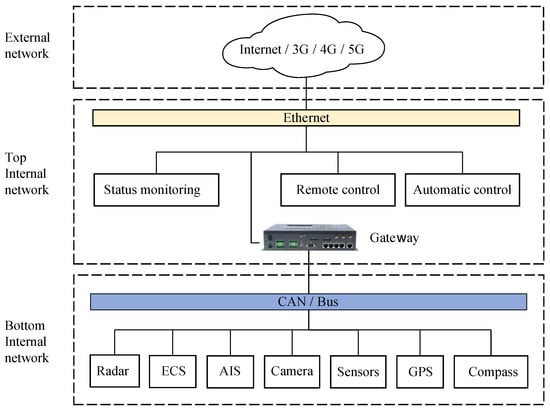

3.3. The Network of USVs

The network of USV primarily consists of three parts [15], namely the bottom internal network, the top internal network, and the external network, as illustrated in Figure 2. The bottom layer of the internal network is implemented by bus technology. The integrated bridge system’s radar, navigation, electronic charts, and AIS transmit data to the management system through a bus or Controller Area Network (CAN) while receiving control commands from the management system. The top layer of the internal network uses Ethernet technology. The status-monitoring, remote, and automatic-control systems obtain USV status data and environmental information via Ethernet. The external networks include the Internet, mobile communication networks, radio, etc. The control system of a USV consists of two parts: the ground control station and the shipborne intelligent control system [33]. Through external networks, ground control stations can monitor real-time data of USVs. At the same time, status data and real-time images from the USV are transmitted to the ground control station via wireless communication. In emergencies, the ground control station can send control commands to USVs through external networks to ensure the safety of USV navigation. Communication between a USV and the ground control station uses real-time data transmission. The wireless transmission distance limits the USV’s working range. According to [34], the transmission distance of 2.4 G Wi-Fi can reach 100 m, the transmission distance of RF can reach 1–5 km, and the transmission distance of 4 G networks can reach 10 km. The coverage range of wireless and mobile communication is limited, and when USVs are far from the shore, there may be insufficient or no signal coverage. Radio at lower frequencies is a good choice; Very High Frequency (VHF) and High Frequency (HF) can cover up to 40 nautical miles. Distributed GNC for USVs communicates via a local area network. This paper focuses on the network security of shipborne intelligent control systems for USVs.

Figure 2.

The network of a USV.

4. Proposed Attacks for USVs

This section proposes five potential attack locations for USVs. Based on these locations, we design a series of attack methods that may target unencrypted and encrypted networks. Next, we introduce the techniques and methods used in attacks. Finally, we analyze the impact of these attack methods on USVs from a theoretical perspective.

4.1. Attack Strategy and Overview

Building upon the vulnerability analysis of the USV’s GNC architecture and network in Section 3, this section formalizes the attack model. It details a series of position spoofing attacks. The core strategy of these attacks is to exploit the trust relationships between GNC modules. By establishing an MITM position on the network, an adversary can target the critical position data flowing from the Navigation system to the Guidance system. Destroying the single data source misleads the entire control chain. The guidance module generates erroneous commands based on false position data, and the control module executes them, ultimately causing the USV to deviate from its intended path.

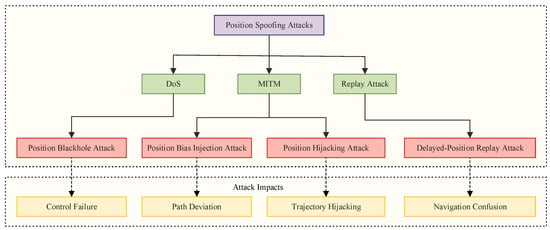

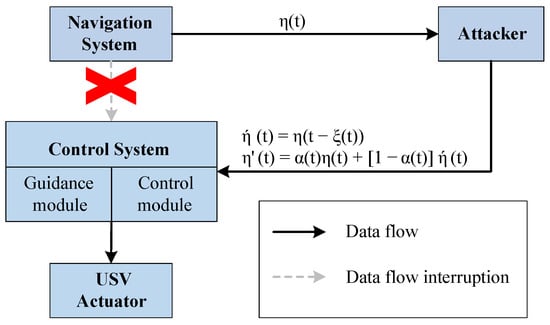

To systematically present this work, we first define the attacker’s capabilities and objectives. Next, we map the specific attack locations within the GNC framework. Based on this foundation, we introduce four novel position spoofing attacks. As illustrated in Figure 3, these attacks manipulate the position data flow in distinct ways:

- Position Blackhole (PBH) Attack: Selectively drops position data packets.

- Position Bias Injection (PBI) Attack: Adds a constant offset to the position data.

- Position Hijacking (PH) Attack: Replaces the authentic position with an adversary-designed trajectory.

- Delayed-Position Replay (DPR) Attack: Replays old and recorded position data to disrupt control.

The following subsections detail the technical implementation and impact of each attack, with the common goal of endangering the USV’s navigational safety.

Figure 3.

Overview of the four proposed position spoofing attack methods against the USV control layer.

4.2. Attack Model

To systematically analyze security threats against USVs, we formally define the attacker model based on the Dolev-Yao adversarial framework [35]. The attacker’s profile is characterized by their capabilities, knowledge, and objectives, under a set of explicitly stated assumptions.

Within the defined threat model, the adversary possesses the capability to infiltrate the USV’s network and MITM attacks, enabling them to intercept, modify, or inject data between GNC modules. Their effectiveness depends on knowledge of the system’s high-level GNC architecture and the use of LOS guidance and PID control; however, it is constrained by a lack of internal cryptographic keys or detailed mission parameters. The primary objectives of the adversary are to maliciously divert the USV from its intended path, lure it towards a fake waypoint, or disrupt its normal operation. This formal model provides the foundational assumptions for the attack methods described in the following sections, ensuring that each proposed attack is grounded in a realistic, well-defined adversarial context.

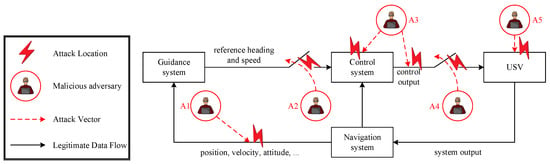

4.3. Attack Locations of USVs

There are various security risks of USVs. Network attacks on USVs may occur at the hardware level of data collection or during data transmission to the navigation system over networks. The paper [36] summarizes the attack on CPS [37]. On this basis, we present the main attack locations against USVs as shown in Figure 4, and the detailed introduction as follows:

- Attack location 1 (A1) is a location of navigation output. Attack location 3 (A3) is within the control module. A1 and A3 represent spoofing attacks, including MITM, replay, and other attacks. Attackers attack sensors or controllers and send fake data.

- Attack location 2 (A2) is a location of guidance output. Attack location 4 (A4) is a location where the control module output is situated. A2 and A4 correspond to DoS attacks, wherein adversaries disrupt communication channels, thereby preventing the controller from receiving sensor measurements or transmitting control commands to USV actuators.

- Attack location 5 (A5) is an external location of USVs. A5 represents direct attacks or external physical attacks on the actuator of USVs.

It is important to delineate the scope of this work. While Figure 4 presents a comprehensive threat model identifying five key attack locations, the subsequent attack design and analysis in this paper primarily focus on spoofing-based attacks targeting locations A1 (Navigation Output) and A3 (Internal Control Module). These locations are critically vulnerable to data-integrity attacks such as MITM and replay attacks, which form the core of our contribution. A comprehensive defense framework also requires robust protections against DoS attacks (A2, A4) and external interface threats (A5). Investigating these attack vectors is a priority for our future work.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of main attack locations and types against a USV.

4.4. Design Attacks for USVs

Based on the above attack locations for USVs, we design a series of position spoofing methods to disrupt and deceive USV communication. To implement the attack on USVs, we have the following assumptions.

- Assumption 1: USVs use the distributed GNC architecture. The guidance module uses the Line-of-Sight (LOS) [38] method, and the control module uses a classic Proportion-Integral-Differential coefficient (PID) method.

- Assumption 2: The distributed GNC system of USVs transmits messages using the Internet Protocol (IP).

Under these assumptions, an adversary gains access to an unsecured USV network, executes attacks targeting the network and control layers, and compromises the USV’s navigation status. In this scenario, an adversary can disrupt communication among GNC modules by blocking, injecting, hijacking, or modifying position data transmissions. At the same time, the adversary may spoof the control module into believing it is still receiving information from the navigation system.

Corresponding to A1 and A3 attack types in Figure 4, an adversary hijacks the position data, then either drops it, replays it, or sends modified data to the guidance and control module of the USV. We design four different position attack methods to implement different effects on USVs, including position blackhole attack, position bias injection attack, position hijacking attack, and position replay attack, as shown in Figure 3.

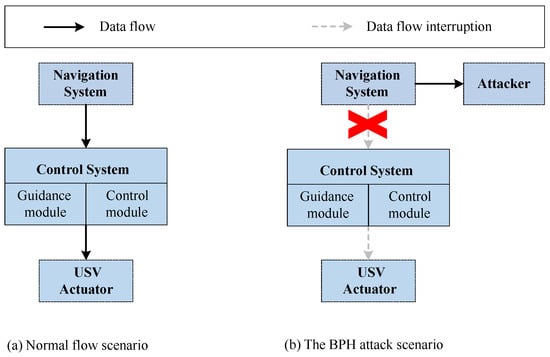

4.4.1. Position Blackhole Attack for USVs

During the transmission of position information between the GNC module of a USV, an adversary may redirect traffic, intercept the position information sent by the navigation module, and drop it without taking any action, preventing the guidance and control module from receiving it. This is known as a Position Blackhole (PBH) Attack. A PBH attack may block the control module of a USV from receiving control commands, thereby compromising its safe navigation. Meanwhile, to prevent a PBH attack from being detected, the adversary can drop part of the specified position information and transmit the rest to the guidance and control module of the USV. This operation is similar to pruning, which can prevent a PBH attack from being detected by the victim. The mathematical model of the PBH attack is as follows.

where is a threshold flag that the adversary sets at any time. The normal flow of packets and the PBH attack scenario are shown in Figure 5. Once the adversary successfully executes a PBH attack, the normal communication between the USV’s GNC module and its surroundings may be disrupted, posing a risk to the USV’s safe navigation.

Figure 5.

Normal data flow versus Position Blackhole (PBH) attack scenario.

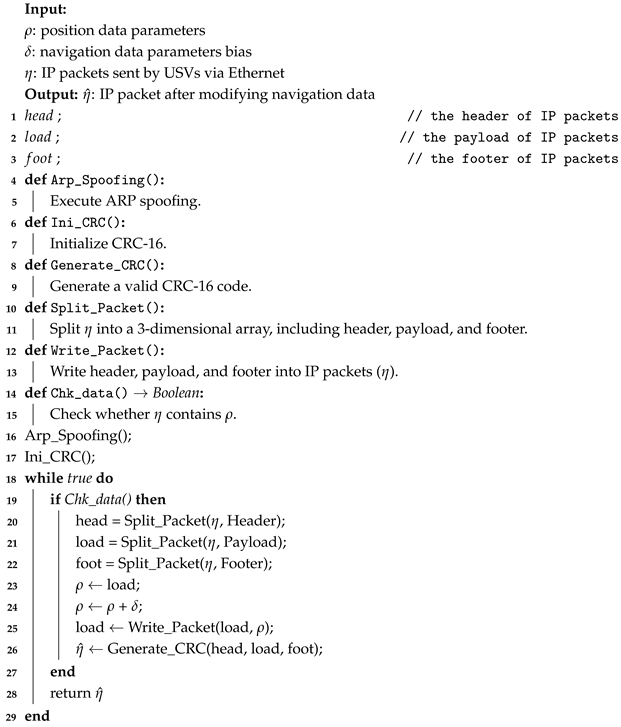

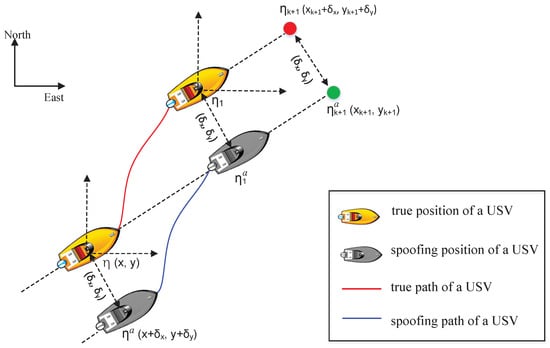

4.4.2. Position Bias Injection Attack for USVs

Position Bias Injection (PBI) Attack is when a constant bias is injected into the position information of a USV during the transmission process among the GNC modules. This attack compromises USV navigation, leading to their failure to reach the intended target position. Due to the subtle magnitude of the injected bias injected each instance, a PBI attack remains particularly challenging to detect by the victim. An adversary employs MITM techniques to intercept network-layer navigation data. The intercepted traffic is then maliciously redirected to the guidance and control modules. The adversary analyzes the intercepted navigation information and transmits IP packets to the guidance module without position information. For IP packets containing position data, the adversary reads the header, payload, and footer separately and parses the position data from the packet. The bias is added to the position data in the packet, and then the header, payload, and footer are encapsulated in the IP packet and sent to the guidance module. The guidance module employs the LOS algorithm to compute a path toward the designated waypoint based on the fake position information received at time t. It subsequently transmits the corresponding control parameters, such as the desired velocity and heading angle , to the USV’s control module. According to these control parameters, the control module sends control commands to the propeller and steering engine of USVs to achieve the required velocity and heading angle. The PBH scenario is illustrated in Figure 6. A mathematical model of the PBI attack is as follows.

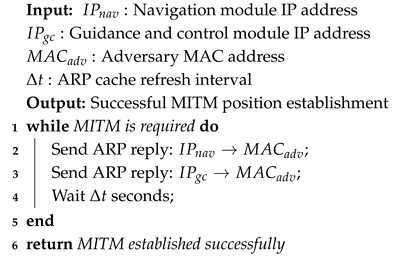

where is the true position information of the USV at time t, is the yaw position information, and is a bias added to the position information by the adversary. The corresponding pseudocode of the method is presented in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: A position bias injection attack for USVs based on IP packets. |

|

Figure 6.

Position Bias Injection (PBI) Attack scenario.

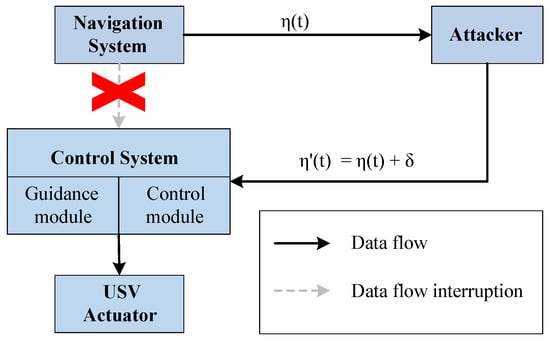

4.4.3. Position Hijacking Attack for USVs

In the Position Hijacking (PH) attack, a malicious adversary employs the MITM strategy to intercept communication channels and surreptitiously replace the authenticated position data , transmitted by the navigation module, with the fake position value at time t. The fake position signal is intercepted by the adversary and, in turn, derived inversely through the LOS algorithm using the authenticated positional data. This fake value can be mathematically expressed as follows:

The PH attack scenario is shown in Figure 7. According to the adversary’s needs, the position basis can be a constant or variable, c is a constant greater than zero, k is an attack frequency parameter, and is a regular trigonometric function. The adversary can dynamically adjust the parameters k and to alter the offset between the fake and true positions, ultimately making the fake position equal to the position the adversary designed. The objective of a PH attack is to disrupt communication among the GNC modules, intercept position information transmitted by the navigation module, and substitute the true position with a fake position provided by the adversary. Consequently, the USV is deceived into navigating toward coordinates specified by the adversary under the influence of the fake position information.

Figure 7.

Position Hijacking (PH) Attack scenario.

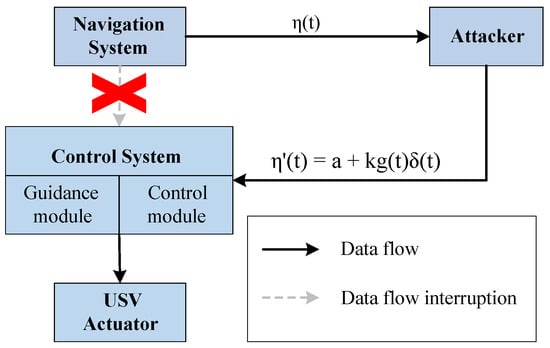

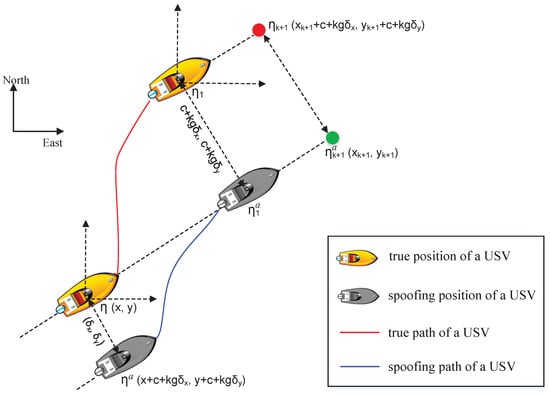

4.4.4. Delayed-Position Replay Attack for USVs

The above attacks are all constructed by adversaries under the assumption that position information is transmitted in the clear. In practice, the transmission of position information among USV GNC modules may be encrypted. As a result, adversaries are unable to parse position data from intercepted encrypted IP packets. To overcome this limitation, we propose a Delayed-Position Replay (DPR) attack targeting encrypted communication among the GNC modules of USVs (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Delayed-Position Replay (DPR) Attack scenario.

Through an MITM attack, an adversary intercepts communications among the GNC modules and captures position information over a specified time interval. Next, the adversary iteratively replays malicious position information. As the guidance and control modules receive and process the malicious data, they may generate erroneous control commands. Execution of the compromised commands ultimately leads to the USV deviating from its intended trajectory. Based on the paper [39], the mathematical model of the PRA can be formalized as follows.

where t is the time when the adversary initiates the PR attack, is the time interval between the adversary recording position information and resending position information, is the position information affected by the PR attack, is the true position information, and is a continuous Bernoulli variable and satisfies the probability , is the replay position information that the replayed data are the data transmitted in previous time .

Corresponding to attack types A2 and A4 in Figure 4, an adversary employs DoS attack techniques to disrupt the server control environment of USVs, resulting in crashes of the control systems. In the case of attack type A5 in Figure 4, an adversary accesses a USV control module through external interface devices, affecting the safety of the USV navigation. These interfaces may be external, such as USB, a bus, or Ethernet. A detailed investigation of the attack methodologies and impacts for locations A2, A4, and A5 is a recognized and vital extension of this study, planned for our future work. Therefore, this paper focuses on the position spoofing attack methods associated with the A1 and A3 types.

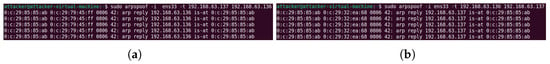

4.5. The Techniques and Methods Used in Attacks

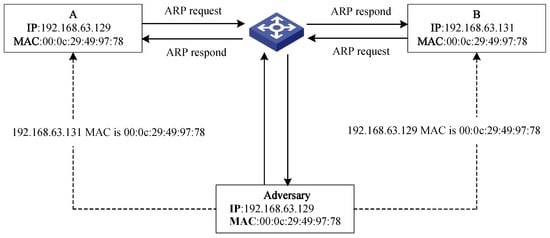

An MITM attack is a common attack method used by adversaries. The classic MITM is an indirect intrusion attack that uses various technical means to virtually place a computer controlled by the intruder between two communicating computers in a network. In this paper, we exploit vulnerabilities in the Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) to launch attacks. The adversary is positioned in the middle of the communication channels and establishes an independent connection with each of them. However, both parties in the communication section are unaware of the adversary’s existence, and the adversary may drop, modify, or block communication data for both parties.

Adversaries can use various techniques to implement MITM attacks, including the following common types.

- Wi-Fi hijacking: Adversaries deploy rogue access points on public networks, enabling the interception and manipulation of communication data from connected users.

- ARP spoofing: Adversaries forge Media Access Control (MAC) addresses to impersonate legitimate network devices, thereby redirecting communication traffic through their own device.

- Domain Name System (DNS) hijacking: Adversaries manipulate DNS resolution results to redirect user requests to malicious websites under their control.

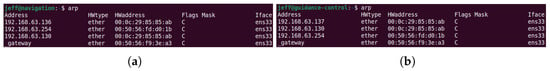

ARP is an address resolution protocol that maps IP addresses to corresponding MAC addresses. We assume a scenario in which modules A and B of a USV communicate within the same DNS domain, potentially leading to DNS hijacking. Adversaries modify DNS resolution results, causing the website the user visits to point to malicious sites under their control. A local network is present, and an adversary C is also present. Module A is assigned IP address 192.168.63.129 and MAC address 00:0c:29:49:97:78. Module B is assigned IP address 192.168.63.131 and MAC address 00:0c:0f:3c:25:97. The adversary C operates with the IP address 192.168.63.130 and MAC address 00:0c:29:85:85:ab. Establishing communication requires knowledge of the recipient’s MAC address, which is dynamically maintained in ARP tables. If module A has only module B’s IP address and lacks the corresponding MAC address, direct communication is impossible. To initiate communication, module A broadcasts an ARP request throughout the network. Upon receiving the request, module B responds to module A with a unicast ARP reply containing its MAC address. After receiving the response, module A stores the IP-MAC mapping of module B in the local ARP cache, enabling subsequent data transmission to module B. Similarly, upon receiving module A’s ARP request, module B records module A’s addressing information in the ARP table. Once both modules have updated the ARP caches, bidirectional communication can proceed normally. This procedure describes the fundamental operation of the ARP protocol, as illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Illustration of the ARP Spoofing technique used against USV modules [40].

Due to the lack of effective authentication mechanisms in ARP, an adversary can exploit these vulnerabilities by transmitting fake ARP response messages to the victim host, causing incorrect IP and physical address mapping relationships to be stored in the ARP cache table, rendering the transmitted information unable to reach the intended host. The core vulnerability stems from ARP’s stateless and trust-based design, which lacks inherent security mechanisms [41]. This fundamental weakness renders the protocol vulnerable to spoofing attacks. Despite persistent research, this problem remains relevant in modern networks, including the Internet of Things (IoT) [42] and CPSs [43]. Consequently, studies on CPS security repeatedly emphasize the vulnerability of their underlying network infrastructure to such attacks, which can undermine data integrity and cause tangible operational disruptions [44]. The continued prevalence of ARP spoofing demonstrates its utility as a persistent threat against networked systems, including USVs. The formal procedure for an ARP spoofing attack to establish an MITM position is detailed in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2: ARP Spoofing for MITM Attack Establishment. |

|

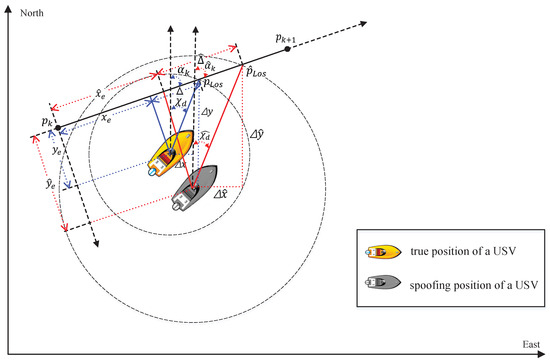

4.6. Analysis of the Attacks Against USVs

To facilitate the study of the influence of MITM attacks on USVs, we exclude the external disturbance to USVs. Accordingly, the parameter d in the mathematical model of USVs is set to 0 in this study. The USV employs the LOS guidance algorithm and is assumed to navigate along a straight path defined by a sequence of waypoints. Among the waypoints, is the previous waypoint, and is the next waypoint. At time t, the true position of the USV is . The two points where a circle with p as the center and as the radius intersect with a straight line are and . Due to being closer to than , is the LOS position, . is the rotated angle between the path-fixed reference frame and the North-East-DOWN (NED) reference frame. is the rotation matrix from the path-fixed reference coordinate system to the NED reference system. , , and satisfy the following equations:

where and are the longitudinal and lateral errors of path tracking for a USV in the path-fixed reference coordinate system. is the look-ahead distance, 2–5 times the length of a USV. is the desired heading angle. Under the control of the rudder and propeller, a USV gradually reduces lateral errors and can track the desired path, as shown in Figure 10. Based on , , and , we can calculate as follows.

Figure 10.

Path planning for a USV using LOS navigation algorithm under no attack and attacks.

Based on Equation (1) in Section 3.1, the motion of a USV is related to the velocity and position. Due to the mutual influence between velocity and position, this paper considers the influence of position on the motion of a USV. Assuming the current true position of the USV at time t is . After receiving the USV’s true position, the guidance module uses the LOS algorithm to calculate the desired position . Therefore, the position offset of the USV is . According to the PID control method, we can compute the actual output of rudder angle . Based on the computed guidance parameters, the control module of the USV transmits command signals to the rudder and propeller, directing the USV’s head toward the next waypoint.

For clearer representation, the superscripts of the attacked parameters are denoted as a. Assuming the current true position of the USV is , the fake position received by the guidance and control system is .

During a PBH attack, the guidance and control modules of the USV are prevented from receiving an authentic position from the navigation module. The offset between the authentic and fake positions can be mathematically represented by the expression . Due to the different values of and , the rudder angle output is affected by PBH . Ultimately, the USV’s navigation is compromised by DBH attacks.

During a PBI attack, the guidance and control module of the USV may receive a fake position injected by an adversary. The fake position acquired by the guidance and control module is denoted as , where . The position biases and are maliciously modified by adversaries through the attack. As illustrated Figure 10, and represent the true and spoofed desired heading angle, and represent the true and spoofed rotated angle, and represent the true and spoofed lateral errors of path tracking, and represent the true and spoofed look-ahead distance for a USV. The guidance module utilizes the spoofed data to compute the desired heading for the USV. Subsequently, the control module allocates appropriate thrust to the propeller based on the computed desired heading. As an adversary has maliciously altered the position data of the USV, the LOS guidance module may guide the USV toward an erroneous position , resulting in the USV to unintended yaw, as depicted in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

The expected navigation path of a USV under no attack and the PBI attack.

During a PH attack, the guidance and control system of the USV may receive fake position data, misleading the USV to navigate toward a destination specified by the adversary. The fake position acquired by the guidance and control system is denoted as , where . The parameters , and are maliciously configured by the adversary through MITM attacks. Using the fake input, the guidance system executes the LOS algorithm to compute control commands. As illustrated in Figure 12, the USV is deceived into following a trajectory toward the manipulated waypoint . Ultimately, the adversary achieved its objective of illegally controlling the USV’s navigation.

Figure 12.

The expected navigation path of a USV under no attack and the PH attack.

During a DPR attack, an adversary initially captures the position signal from the navigation system at the following time instances: , , , , and . At time , the adversary executes an MITM attack to intercept and compromise the navigation module. The adversary subsequently replays the previously recorded position data to the guidance and control module n times, where . By continuously injecting these recorded positions into the guidance and control systems, the adversary effectively replaces the legitimate data and induces abnormal fluctuations in the control signal b. These erroneous control commands force the USV to alter its heading, ultimately causing significant deviation from the intended course.

In summary, the analysis presented in this study demonstrates that these attacks, including Position Blackhole, Position Bias Injection, Position Hijacking, and Delayed-Position Replay, are effective. These attack strategies can compromise the integrity of navigation data, disrupt control signals, and ultimately lead to hazardous deviations from intended trajectories. This research underscores the critical need for robust defensive mechanisms in maritime CPSs.

4.7. Attack Realism, Defenses, and System Applicability

The proposed attacks remain highly feasible under conditions in current maritime CPSs. Many modern USVs integrate legacy subsystems or Commercial Off-The-Shelf (COTS) components that are not designed with cybersecurity as a priority, often relying on standard but unauthenticated protocols, thereby establishing an inherently vulnerable communication foundation [45]. Furthermore, the feasibility of the attacks is significantly heightened in real-world scenarios involving Trojan-infected devices or malicious insiders within the USVs’ network.

Although existing defense mechanisms can partially mitigate the threats posed by the attack methods in this study, the core contribution of this work lies not in defeating such defenses, but in demonstrating the severe consequences that arise in their absence, thus providing a firm rationale for their implementation.

The applicability and immediacy of these threats vary significantly across different operational domains. Commercial and civilian USVs for applications such as cargo, research, or monitoring are the most susceptible, as they often focus on cost and interoperability, leading to the use of standard IP networks with less stringent security configurations. The majority of USV prototypes in both academia and industry utilize standard Ethernet and IP-based communication, which simplifies development but also introduces significant vulnerabilities to cyber-physical attacks. In contrast, military systems are typically designed with a layered defense-in-depth approach, making a simplistic ARP spoofing attack less probable for an external attacker. Nevertheless, the fundamental attack vectors, spoofing and corrupting critical navigation data, remain highly relevant.

With this context established, the following section presents the simulation setup and results to demonstrate the concrete impacts of these attacks.

5. Results

In this section, we present experimental evaluations to validate the impact of MITM-based attacks on a USV. A USV navigates across water surfaces, performs collision avoidance, and avoids obstacles through guidance, navigation, and automatic control [46]. This study focuses on the USV equipped with a distributed GNC system; the simulated USV in our experiments also adopts this structure.

The simulation environment was configured with the following key parameters to ensure a realistic and well-defined experimental setup: The USV dynamics were modeled using Equation (1) with representative parameters for a small-scale vehicle (including defined inertia and damping matrices) as detailed in [47]. The navigation system (GPS/IMU) and the control loop were synchronized at a sampling frequency of 10 Hz. A delay of 50 ms was incorporated into the control chain to account for actuation and computational latency. All GNC modules communicated via the User Datagram Protocol (UDP) protocol over a local Ethernet network, with position data packets transmitted at the 10 Hz sampling rate.

The core mechanism of the implemented attack involved an adversary continuously transmitting fake ARP response packets to manipulate the IP-MAC mapping in the target victim’s ARP cache. The experimental setup utilized a personal computer equipped with an AMD Ryzen 5 3500U CPU, Radeon Vega Mobile Graphics, running at 2.10 GHz, with 32 GB of RAM and a 500 GB hard drive (AMD, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The host operating system was Windows 10 (64-bit). We used VMware 15 Pro virtual machine software to configure three virtual machines, including a navigation module, a guidance and control module, and an adversary. All virtual machines operated under Ubuntu 22.04.3. The detailed virtual hardware and network configurations for both the victim modules and the adversary are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

The virtual hardware information of the victim host and the adversary.

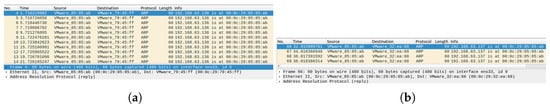

In the initial phase, the simulated adversary scans the active hosts within the network segment and identifies the IP addresses of the victim USV modules: the navigation module at 192.168.63.137 and the guidance and control module at 192.168.63.136. The adversary initiates an ARP spoofing attack against both targets. By continuously transmitting fake ARP replies to the navigation module (192.168.63.137), the adversary forces it to update its local ARP cache with malicious entries. At the same time, a similar attack is launched against the guidance and control module (192.168.63.136), compromising its ARP mapping in the same manner. The specific commands used in the attack are provided in Figure 13. Network traffic captured using Wireshark across the GNC modules confirms the reception of spoofed ARP responses from the adversary, as illustrated in Figure 14. Following the attack, the navigation module’s ARP table shows that the MAC address of the guidance and control module matches that of the adversary. Likewise, the ARP cache of the guidance and control module erroneously maps the navigation module’s IP address to the adversary’s MAC address. The modified IP–MAC mappings of both modules are illustrated in Figure 15, confirming the successful execution of the ARP spoofing attack. As a result, any communication among the GNC modules is redirected to the adversary.

Figure 13.

Example commands used by the adversary to launch the ARP spoofing attack. (a) Navigation module; (b) guidance and control module.

Figure 14.

Wireshark network packet capture showing spoofed ARP traffic. (a) The navigation module; (b) the guidance and control module.

Figure 15.

ARP cache tables of the victim modules after the ARP spoofing attack. (a) The navigation module; (b) the guidance and control module.

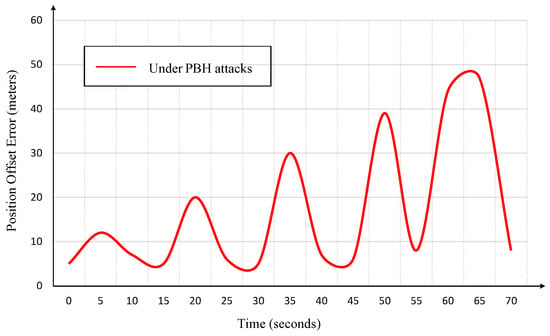

In a PBH attack, the adversary redirects communication traffic, intercepts the position information transmitted by the navigation module, and discards it without action. The guidance and control module fails to acquire position information, resulting in the accumulation of offset errors, as shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

USV offset error under Position Blackhole (PBH) Attack.

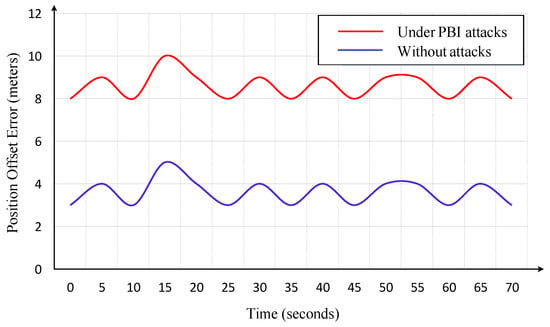

In a PBI attack, the adversary injects a constant bias into the USV’s position data during transmission among GNC modules. As depicted in Figure 17, this manipulation results in a progressive increase in the offset error.

Figure 17.

Comparison of USV offset error under normal conditions and Position Bias Injection (PBI) Attack.

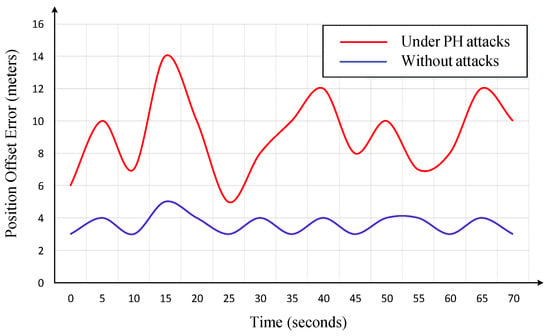

In a PH attack, the adversary employs the MITM technique to redirect the communication traffic and substitute the authentic position transmitted by the navigation module, with a fake position , where . The parameters k, , and the adversary maliciously configures to manipulate the spoofed position output. As shown in Figure 18, the PH attack results in a progressive increase in offset errors.

Figure 18.

Comparison of USV offset error under normal conditions and Position Hijacking (PH) Attack.

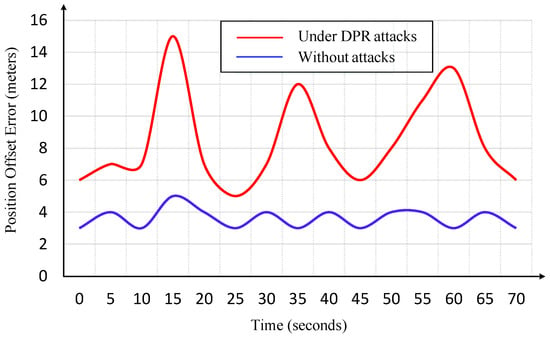

In a DPR attack, the adversary uses an MITM technique to intercept communications between the GNC modules. The adversary records the authenticated position information over a defined duration (), and subsequently replays the maliciously captured information repeatedly to the guidance and control modules. As depicted in Figure 19, PRA induces a noticeable increase in the offset errors during the replay phase.

Figure 19.

Comparison of USV offset error under normal conditions and Delayed-Position Replay (DPR) Attack.

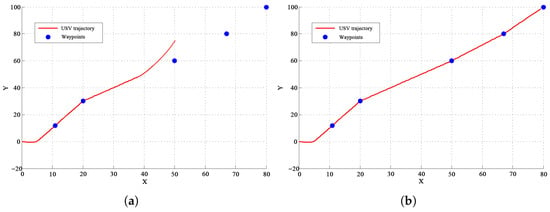

The adversary can execute the spoofing Algorithm 1 in Section 4.4 to compromise both the navigation module and guidance and control modules of the target USV. Specifically, the adversary modifies the navigation data within intercepted IP packets and transmits the manipulated data to the guidance and control system host. This results in erroneous path-planning decisions and faulty control commands from the guidance and control module. These inaccuracies can induce unintended yaw motion in the USV, thereby jeopardizing its safe navigation and operation. The comparative trajectories of the USV under normal conditions and under attack are presented in Figure 20.

Figure 20.

Comparative USV navigation trajectories under normal operation and adversarial spoofing attacks. (a) Normal operation; (b) under adversarial spoofing attacks.

For the above position spoofing attacks, we extracted key indicator metrics from the offset error data of Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18 and Figure 19 for quantitative comparison of severity and characteristics. Table 2 summarizes the maximum offset error and the average offset error during the attack period for each scenario.

Table 2.

Quantitative comparison of attack impacts on USV navigation.

The influence of these offset errors on the safe navigation of USVs is important. In the marine environment, a navigation deviation of even 10 m may result in major maritime accidents. Especially during the critical phases of entering and leaving ports, passing through narrow or crowded waterways, these deviations may directly lead to collisions with other ships, docks, or underwater obstacles. The data in Table 2 show that the deviations caused by the four proposed attacks exceed the safe threshold. In particular, the PH attack causes a maximum deviation of more than 25 m.

6. Discussion

The simulation results show that position spoofing attacks are different in form, but all the attacks can cause dangerous deviation when USVs navigate. The quantitative analysis reveals the impact of four attacks, indicating that the defense mechanism must detect not only large, obvious anomalies but also subtle, persistent data changes. The analysis results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

The analysis results of position spoofing attacks for USVs.

These findings have far-reaching practical significance for maritime network security:

- The dependence on standard IP networks and unauthenticated protocols within the USV internal control network is a fundamental design flaw. Our work provides an argument for enforcing integrated design security principles. For example, the subsequent design of a USV can implement strong encryption, authentication, and integrity protection for all data exchanges between GNC modules.

- The attack method we proposed has proven its effectiveness and established a necessary foundation for the security verification of USVs. These four attack methods can be used as the test tools to evaluate the security of the USV navigation system.

- For the Maritime Safety Administration (MSA), this study emphasizes the need to develop and implement cybersecurity standards.

7. Conclusions

This paper identifies five potential attack locations in USVs: the navigation module’s data transmission process, the guidance module’s data transmission process, the control module’s internal and output channels, the control module’s data transmission process, and the USV’s external communication interfaces. We design four attack methods based on location to target the control systems of USVs. The adversaries may disrupt, alter, delay, and maliciously control transmitted GNC information to usurp control of USVs, thereby inducing deviations from intended trajectories. We further analyze the impact of these attacks through theoretical modeling and conduct a series of simulations to validate the threats to USV navigation safety, with varying levels of practical effectiveness across different attack types.

This paper analyzes USV network attacks. In the future, we will design more sophisticated network attacks against USVs that are undetectable to victims, which may advance research on USV network security.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X. and T.L.; Methodology, J.W., Y.X., T.L. and P.C.L.C.; Investigation, J.W.; Writing—original draft, J.W.; Writing—review & editing, Y.X., T.L. and P.C.L.C.; Supervision, Y.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work of J. Wang and T. Li are partially supported by the Liaoning Revitalization Talents Program, XLYC1908018.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

For clarity, the abbreviations used in this paper are defined.

| USV | Unmanned Surface Vehicle |

| EMSA | European Maritime Safety Agency |

| GNC | Navigation, Guidance, and Control |

| CPS | Cyber-Physical System |

| CFI | Control Flow Integrity |

| DFI | Data Flow Integrity |

| RBAC | Role-Based Access Control |

| MITM | Man-in-the-Middle |

| DoS | Denial of Service |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| JA-APF | Jamming Aware Artificial Potential Field |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| CAN | Controller Area Network |

| VHF | Very High Frequency |

| HF | High Frequency |

| PBH | Position Blackhole |

| PBI | Position Bias Injection |

| PH | Position Hijacking |

| DPR | Delayed-Position Replay |

| LOS | Line-of-Sight |

| PID | Proportion Integral-Differential |

| IP | Internet Protocol |

| ARP | Address Resolution Protocol |

| MAC | Medium Access Control |

| DNS | Domain Name System |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| NED | North-East-DOWN |

| COTS | Commercial Off-The-Shelf |

| UDP | User Datagram Protocol |

| MSA | Maritime Safety Administration |

References

- EMSA. Annual Overview of Marine Casualties and Incidents; Technical Report; EMSA: Lisboa, Portugal, 2023; Available online: https://www.emsa.europa.eu/newsroom/latest-news/download/7639/5055/23.html (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Wang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Li, T.; Chen, C.P. A survey of technologies for unmanned merchant ships. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 224461–224486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanakitkorn, K. A review of unmanned surface vehicle development. Marit. Technol. Res. 2019, 1, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, S. Developments in unmanned surface vehicles (usvs): A review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Engineering and Natural Sciences, Konya, Turkey, 10–12 July 2023; Volume 1, pp. 596–600. [Google Scholar]

- Leni, A.; Anand, R.; Mythili, N.; Pugalenthi, R. An improved cyber-attack detection and classification model for the internet of things systems using fine-tuned deep learning model. Int. J. Sens. Netw. 2025, 47, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Journal. Electronic Warfare Extends to GPS Spoofing Attacks Affecting Hundreds of Flights Daily; Technical Report; World Journal: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/nMDVAVcZDPeAqmnl9xciTQ (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- WIRED. GPS Jamming Is Screwing with Norwegian Planes; Technical Report; WIRED: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.wired.com/story/gps-jamming-is-screwing-with-norwegian-planes/ (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Park, J.H. North Korea Jams GPS Signals Near Border to Disrupt Ships and Planes: Seoul; Technical Report; NKNEWS: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2024; Available online: https://www.nknews.org/2024/11/north-korea-jams-gps-signals-near-border-to-disrupt-ships-and-planes-seoul/ (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Cheng, L.; Tian, K.; Yao, D. Orpheus: Enforcing cyber-physical execution semantics to defend against data-oriented attacks. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Computer Security Applications Conference, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 4–8 December 2017; pp. 315–326. [Google Scholar]

- Barua, A.; Faruque, M.A.A. Sensor security: Current progress, research challenges, and future roadmap. In Proceedings of the 41st IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design, San Diego, CA, USA, 29 October–3 November 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Y.; Tida, V.S.; Pan, Z.; Hei, X. Transduction shield: A low-complexity method to detect and correct the effects of EMI injection attacks on sensors. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Virtual, 7–11 June 2021; pp. 901–915. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Wu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Qi, X.; Zhang, W.; Qiao, G.; Zuo, D. A lightweight secure scheme for underwater wireless acoustic network. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laso, P.M.; Brosset, D.; Giraud, M.A. Defining role-based access control for a secure platform of unmanned surface vehicle fleets. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2019, Marseille, France, 17–20 June 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, I.; Park, Y.; Hur, S.; Kim, S.W.; Alroobaea, R.; Zikria, Y.B.; Nosheen, S. A survey on cyber security threats in IoT-enabled maritime industry. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 24, 2677–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Dou, X.; Xu, F.; Song, W.; Li, T. Survey on Unmanned Ship’s Network Information Security Technology. Telecommun. Eng. 2022, 62, 1537–1544. [Google Scholar]

- Mahjabin, T.; Xiao, Y.; Sun, G.; Jiang, W. A Survey of distributed denial-of-service Attack, Prevention, and Mitigation Techniques. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2017, 13, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodday, N.M.; Schmidt, R.d.O.; Pras, A. Exploring security vulnerabilities of unmanned aerial vehicles. In Proceedings of the NOMS 2016—2016 IEEE/IFIP Network Operations and Management Symposium, Istanbul, Turkey, 25–29 April 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 993–994. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, G.; Miani, R.S.; Guizilini, V.C.; Souza, J.R. Evaluation of DoS attacks on commercial Wi-Fi-based uavs. Int. J. Commun. Netw. Inf. Secur. 2019, 11, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyriou, G.C.Y.L.A. A Replay Attack Against ISAC Based on OFDM. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 20998–21003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, T.E.; Ledvina, B.M.; Psiaki, M.L.; O’Hanlon, B.W.; Kintner, P.M., Jr. Assessing the spoofing threat: Development of a portable GPS civilian spoofer. In Proceedings of the 21st International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS 2008), Savannah, GA, USA, 16–19 September 2008; pp. 2314–2325. [Google Scholar]

- Kerns, A.J.; Shepard, D.P.; Bhatti, J.A.; Humphreys, T.E. Unmanned aircraft capture and control via GPS spoofing. J. Field Robot. 2014, 31, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Li, T.; Chen, C.P. Impacts of GPS Spoofing on path planning of unmanned surface ships. Electronics 2022, 11, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.; Gaspar, J.; Sebastião, P.; Souto, N. A software defined radio based anti-UAV mobile system with jamming and spoofing capabilities. Sensors 2022, 22, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Zhang, G.; Huang, C.; Zhang, W. Memory-based event-triggered path-following control for a USV in the presence of DoS attack. Ocean Eng. 2024, 310, 118627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Li, T.; Chen, C.P. A Jamming Aware Artificial Potential Field Method to Counter GPS Jamming for Unmanned Surface Ship Path Planning. IEEE Syst. J. 2023, 17, 4555–4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhu, G.; Xu, Y.; Ding, L. Periodic event-triggered adaptive neural control of USVs under replay attacks. Ocean Eng. 2024, 306, 118022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Y.; Benzaïd, C.; Yang, B.; Taleb, T.; Shen, Y. Deep-Ensemble-Learning-Based GPS Spoofing Detection for Cellular-Connected UAVs. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 25068–25085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagdilelis, D. Multi-Modal Sensor Fusion for Cyber-Resilient Navigation of Autonomous Ships. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Denmark, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024. Available online: https://backend.orbit.dtu.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/388731705/Thesis_2_.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Longo, G.; Martelli, M.; Russo, E.; Merlo, A.; Zaccone, R. Adversarial waypoint injection attacks on Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASS) collision avoidance systems. J. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2024, 23, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamamoto, M.; Akiyoshi, T. Study on Ship Motions and Capsizing in Following Seas (1st Report) Equations of Motion for Numerical Simulaion. J. Soc. Nav. Archit. Jpn. 1988, 1988, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjetne, R.; Smogeli, Ø.; Fossen, T.I. Modeling, identification, and adaptive maneuvering of Cybership II: A complete design with experiments. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2004, 37, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solnør, P.; Volden, Ø.; Gryte, K.; Petrovic, S.; Fossen, T.I. Hijacking of unmanned surface vehicles: A demonstration of attacks and countermeasures in the field. J. Field Robot. 2022, 39, 631–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunsheng, F.; Zenglu, G.; Yongsheng, Z.; Guofeng, W. Design of information network and control system for USV. In Proceedings of the 2015 54th Annual Conference of the Society of Instrument and Control Engineers of Japan (SICE), Hangzhou, China, 28–30 July 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1126–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, J.; Li, T.; Geng, T. The wireless communications for unmanned surface vehicle: An overview. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Robotics and Applications: 11th International Conference, ICIRA 2018, Newcastle, Australia, 9–11 August 2018; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. Proceedings, Part I 11. pp. 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cervesato, I. The Dolev-Yao intruder is the most powerful attacker. In Proceedings of the 16th Annual Symposium on Logic in Computer Science—LICS, Washington, DC, USA, 16–19 June 2001; Citeseer. Volume 1, pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas, A.A.; Amin, S.; Sastry, S. Secure control: Towards survivable cyber-physical systems. In Proceedings of the 2008 the 28th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems Workshops, Beijing, China, 17–20 June 2008; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 495–500. [Google Scholar]

- Dibaji, S.M.; Pirani, M.; Flamholz, D.B.; Annaswamy, A.M.; Johansson, K.H.; Chakrabortty, A. A systems and control perspective of CPS security. Annu. Rev. Control 2019, 47, 394–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimane, Z.; Nouali, I.; Abdelmalek, A. Modified UKF for accurate indoor UWB multi-target tracking in the context of SaS NLOS model. Int. J. Sens. Netw. 2024, 44, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Long, Y.; Li, T.; Park, J.H.; Chen, C.P. Fault Detection for Unmanned Marine Vehicles Under Replay Attack. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2022, 37, 1716–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, S. An introduction to ARP Spoofing. Technical Report. 2001. Available online: http://www.gbppr.net/2600/arp_spoofing_intro.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Plummer, D.C. RFC0826: Ethernet Address Resolution Protocol: Or Converting Network Protocol Addresses to 48. bit Ethernet Address for Transmission on Ethernet Hardware. 1982. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.17487/RFC0826 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Yang, Y.; Lian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, S.; Gu, W.; Ling, M. PULP-Lite: A more light-weighted multi-core framework for IoT applications. Int. J. Sens. Netw. 2025, 49, 4555–4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabelsi, Z.; El-Hajj, W. ARP spoofing: A comparative study for education purposes. In Proceedings of the 2009 Information Security Curriculum Development Conference, Kennesaw, GA, USA, 25–26 September 2009; pp. 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Humayed, A.; Lin, J.; Li, F.; Luo, B. Cyber-physical systems security—A survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017, 4, 1802–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, K.N. Recommended Design Rules for Developing and Maintaining a General Noise-and Attenuation-Tolerant Sensing System Aboard a Maritime Vessel. Master’s Thesis, University of Hawai’i at Manoa, Honolulu, HI, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- McCue, L. Handbook of marine craft hydrodynamics and motion control [bookshelf]. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 2016, 36, 78–79. [Google Scholar]

- Fossen, T.I. Handbook of Marine Craft Hydrodynamics and Motion Control; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).