Abstract

Operational modal analysis (OMA) is essential for long-term health monitoring of offshore wind turbines (OWTs), helping identifying changes in structural dynamic characteristics. OMA has been applied under parked or idle states for OWTs, assuming a linear and time-invariant dynamic system subjected to white noise excitations. The impact of complex operating environmental conditions on structural modal identification therefore requires systematic investigation. This paper studies the applicability of OMA based on covariance-driven stochastic subspace identification (SSI-COV) under various non-white noise excitations, using a DTU 10 MW jacket OWT model as a basis for a case study. Then, a scaled (1:75) 10 MW jacket OWT model test is used for the verification. For pure wave conditions, it is found that accurate identification for the first and second FA/SS modes can be achieved with significant wave energy. Under pure wind excitations, the unsteady servo control behavior leads to significant identification errors. The combined wind and wave actions further complicate the picture, leading to more scattered identification errors. The SSI-COV based modal identification method is suggested to be reliably applied for wind speeds larger than the rated speed and with sufficient wave energy. In addition, this method is found to perform better with larger misalignment of wind and wave directions. This study provides valuable insights in relation to the engineering applications of in situ modal identification techniques under operating conditions in real OWT projects.

1. Introduction

As global warming intensifies, sustainable energy development has gained significant attention as a means to reduce fossil fuel dependence and limit carbon emissions. Offshore wind energy, in particular, has experienced substantial growth in recent years [1], with the global installed capacity of offshore wind turbines (OWTs) surpassing 60 GW by 2023 [2]. It is anticipated that this trend will increase significantly soon. However, OWTs face more challenging operational environmental conditions than those exposed to onshore, resulting in greater structural reliability challenges and higher operational maintenance (O&M) costs [3]. It is reported that the O&M costs for OWT projects can potentially account for 30% of the total project costs [4], which represents a significant financial burden. Therefore, structural health monitoring for OWTs plays a critical role in observing structural state in real time and providing precise decision support for O&M cost reduction [5,6].

Operational modal analysis (OMA) plays a crucial role in extracting modal parameters, which are vital for monitoring the structural health of OWTs, offering critical insights for assessing operational conditions, identifying structural damage, and providing guidance for structural design [7]. This facilitates the development of a data-driven numerical model that closely represents the physical OWT structure, enabling the prediction of structural responses and assessment of structural health and lifetime [8,9,10]. In recent decades, OMA techniques have been developed significantly across frequency and time domains. Within the frequency domain, methodologies like the peak-picking (PP) [11], PolyMax method [12], and frequency domain decomposition (FDD) [13] were introduced. In terms of the time domain, techniques such as Random Decrement Technique (RDT) [14], the Eigensystem Realization Algorithm (ERA) [15], Natural Excitation Technique (NExT) [16], Auto-Regressive Moving Average (ARMA) [17], Data-Driven Stochastic Subspace Identification (SSI-DATA) [18], and Covariance-Driven Stochastic Subspace Identification (SSI-COV) [19] were introduced. OMA techniques have been successfully applied to damage detection for wind turbine blades [20,21]. Shirzadeh et al. [22] established the OMA technique and evaluated the damping ratio of the fundamental fore–aft (FA) mode for an offshore wind turbine under overspeed stop tests and ambient excitation conditions. Weijtjens et al. [23] attempted to apply the OMA technique to monitor the scour at the foundation of an offshore wind turbine. Zhou et al. [24] explored the dynamic characteristics of monopile OWT using ERA, SSI, and weak-mode identification (WMI) through sea tests. Among these methods, SSI has become one of the most widely considered OMA methods for OWT monitoring due to its high computational efficiency and accuracy in experimental environment [8,25], with promising potential for in situ applications [26].

Long-term monitoring of structural modal parameters is essential to assess the reliability of structures thoroughly [10,27]. Magalhães et al. [28] proposed an innovative automatic SSI-COV method for modal parameters identification of bridges based on long-term online monitoring. Subsequently, the automatic SSI-COV method was considered for OWT structural monitoring, and the results indicated that this method has high identification accuracy during idle or parked states [6]. Several studies also point out that OMA technology performs better when the OWT is in a parked state compared to operating states with blade rotation [5,26], mainly due to the limitations imposed by OMA’s fundamental assumptions. Specifically, OMA technique assumes that the identified system is linear, time-invariant, and subject to stationary, white-noise-type excitation with no temporal or spatial correlation [29].

However, the OWTs continuously adjust the nacelle orientation (yaw) and blade pitch angle during the operation, resulting in nonlinear and nonstationary dynamic behavior [30,31]. Harmonic excitations, including 3P and 6P introduced by blade rotation lead to significant deviation from the white noise assumption [32]. Distinguishing between modes becomes challenging when the harmonic frequencies (i.e., 3P or 6P) approach the structural modal frequency. It also encounters onerous environmental conditions, including stochastic wind turbulence and wave excitations, which strictly violate the assumption of white-noise excitation [8]. Nevertheless, OWTs are mostly in operation during their lifetime. It is therefore vital to make full use of in situ data under normal operating conditions to largely improve structural monitoring. The high nonlinearity of structural dynamics and the complex variations in the marine environment pose challenges to reliable modal identification. It is therefore essential to clarify the effect of those complex factors on the identification results of OWTs.

Relatively few studies have tackled these challenges directly. Some researchers have explored the effects of signal noise, measurement time, vibration amplitudes, and stationarity of the ambient response on the identification of damping, as opposed to the modal frequencies and mode shapes using SSI-COV method [5]. For non-white noise harmonic excitation, Dong et al. [33] introduced the harmonic modification SSI method to isolate the harmonic components. However, its limitation lies in the assumption that the input harmonic frequencies must remain time-invariant and need to be known, whereas these frequencies are typically unknown. Several studies indicated that the identified modal frequency significantly changes especially when the turbines are in operation, primarily due to nonlinear and nonstationary effects such as varying pitch angle, and nacelle angle [34,35,36,37]. However, the existing research has not addressed whether the OMA method remains accurate when environmental excitations and structural nonlinearity do not conform to white noise excitation. To summarize, there is a notable research gap regarding the impact of load excitations, including turbulent winds and stochastic irregular waves, and blade rotation on the results of the OMA methods. Thus, it is imperative to investigate the applicability of the methods under operating environments, which will significantly enhance their reliability.

This research intends to explore the influence of non-white noise excitations, including turbulent winds and stochastic sea states on the OWT modal parameter identification accuracy. In addition, most modal parameter identification techniques were investigated for monopile-support OWTs. With the trend toward deeper offshore installations, the advantage of jacket-type OWT shows up for its higher OWT installation capacity. Furthermore, SSI-COV method is focused in the present study due to its high computational efficiency for online OWT monitoring [8]. Therefore, in the present study, the intention is to provide guidance for the engineering implementation of SSI-COV method for identifying modal parameters in real projects for structural monitoring and in situ online safety assessment for jacket-type OWTs.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: the next section introduces the basic theory of the automated SSI-COV method. Section 3 describes the considered numerical model of the jacket OWT, as well as the considered typical operating environments. Section 4 analyzes the identification results under different operating environments, followed by a discussion on the influence of environmental excitations on the identification results. Section 5 presents further verification through experimental data from scaled model testing of a jacket-type OWT. The conclusions are presented in Section 6.

2. Method

2.1. SSI-COV Method

The SSI-COV method [19] primarily estimates the state and output matrices of the state-space system using output-only measurements. The state-space system equation is described as follows:

where denotes a state vector of the system at time instant k, denotes the output vector. is a state matrix, and is an output matrix. is a modeling noise vector, is a measurement noise vector. They are uncorrelated with zero mean. The covariance matrices of and are represented by the following formulation:

where E denotes the expected operator, p and q are the two arbitrary time instants, denotes the Kronecker delta, T represents the transpose of a matrix, and Q, S, and R are constant.

The output covariance matrix is defined as

where i denotes any time lag for covariance calculation. Then, the output covariance matrices are gathered in a Toeplitz matrix ,

The Toeplitz matrix is further decomposed of singular value decomposition (SVD) and the Moore–Penrose pseudo-inverse, and the exact derivation is given in the literature. Finally, the state-space matrices can be obtained as

where , , denotes the selected model order, represents a Hankel matrix with one block row, is a state sequence, and superscript † denotes the Moore–Penrose pseudo-inverse. To obtain the modal parameters, an eigenvalue analysis of the continuous time system matrix is carried out as follows [26]:

where ∧ represents the eigenvalue matrix, denotes the eigenvector of . The eigenvector matrix of the continuous time system matrix is identical to that of . Let ; is the sampling time interval, is the eigenvalue matrix of is the natural frequency, is the damping ratio, is the mode shape of the structure, represents the diagonal element of the matrix , and the subscript indicates the utilization of only alternate eigenvalues. Complex conjugate pairs are constituted by these eigenvalues, and modal parameters corresponding to a specific vibration mode are obtained by each pair.

2.2. Automated Clustering Algorithm

Choosing the appropriate order of the state space model is crucial for identifying the system matrix A. It is also challenging to obtain the model order that accurately reflects the response of structures in reality. The stabilization diagram serves as an effective method for the selection of system order and estimation of stable modes [38]. In a stabilization diagram, stable poles are modes with similar frequency, mode shape, and damping ratio in most system orders. If the modal parameters between adjacent orders fall within acceptable limits, the pole is considered similar and stable. Otherwise, it is deemed as a spurious mode. However, the modal parameters need to be judged based on the experience after obtaining the stabilization diagram, and the selection of different stable poles might result in varying results, which can not be directly applied to automatic estimation as part of long-term monitoring.

The hierarchical clustering algorithm can be used for clustering stable poles in an automatic process [28,39]. The algorithm constructs a tree-like hierarchy. Each object is treated as an individual cluster, while the two closest clusters are merged into one single cluster step by step. A large cluster will be obtained. The basic workflow of the hierarchical clustering algorithm is briefly discussed as follows.

Firstly, calculate the similarity among all pairs of estimated stable modes. The Euclidean distance between the objects is used for estimation of the similarity. The Euclidean distance is calculated using the similarity measures derived from natural frequency and mode shape estimates. In addition, the distance between two modes (i and j) is calculated based on Equation (7),

where is the natural frequency of the mode i, and is the modal assurance criterion between the ith and jth mode shapes. If the distance is small, they are considered to be identical physical modes, and ought to be grouped into one cluster. The hierarchical tree is established using a single linkage. The minimum distance between any pair of points sourced from each respective cluster is defined as the distance between two clusters. Equation (7) shows how to calculate the distance. The level of the hierarchical tree cut depends on the number of clusters, which is usually unknown. A criterion for the hierarchical tree cut is to enforce a maximum threshold on the distance from each point to its closest neighbor within one cluster [28]. The physical modes are determined for a cluster with a higher number of elements. Finally, the average of each cluster is output as the physical modal parameters.

In the application of SSI-COV, several hyperparameters should be determined, including the time lag for covariance calculation (Ts), the maximal value of the model order (Nmax), frequency difference (eps_freq), damping difference (eps_zeta), and modal confidence criterion difference (eps_MAC). It is important to note that the term “difference” specifically refers to the relative error. The selection of those hyperparameters could be essential for the identification, but such influence might also be ignorable. In this study, various hyperparameter settings were attempted to minimize their impact on the identification results across extensive conditions, while also incorporating engineering practical experience [26,28,40]. Ultimately, Ts was set to 20 s, Nmax to 20, eps_freq to 10%, eps_MAC to 10%, and eps_zeta to 10%. This study focuses on the automated evaluation of natural frequency and mode shape, with no further discussion on damping ratio estimation.

3. Case Study for Jacket Offshore Wind Turbine

3.1. Model Description

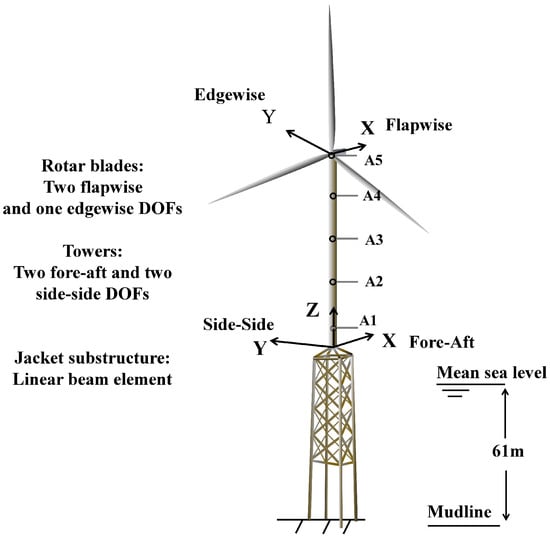

Investigation on the applicability of SSI-COV was carried out based on a 10 MW jacket OWT. Its main structural parameters are illustrated in Figure 1 and summarized in Table 1. The DTU 10 MW wind turbine [41] was applied. The design of the tower and the jacket support structure refers to [42].

Figure 1.

Illustration of the considered jacket OWT.

Table 1.

The structural parameters and properties of the DTU 10 MW OWT structure.

A coupled numerical model for the simulation of jacket OWT dynamics was established in FAST v8, which includes the modules ElastoDyn, SubDyn, AeroDyn, HydroDyn, ServoDyn, and InflowWind [43]. The Rotor-Nacelle Assembly (RNA) including blades, nacelle, drivetrain, and hub, were modeled in the ElastoDyn module. The blade flexibilities were simulated by two flapwise modes and one edgewise mode, while the nacelle was set with two DOFs (i.e., yaw and pitch). The tower was modeled by beam elements with variable cross-sections, considering two DOFs in the fore–aft (FA) and side-to-side (SS) directions. BModes [44] was used to calculate the modes of the blades and tower, and these modes served as the input to the ElastoDyn module. The jacket foundation was modeled in the SubDyn module based on linear finite-element beam theory and the Craig–Bampton (C-B) method. The aerodynamic loads on the blades and the tower were computed by the AeroDyn module. HydroDyn module was utilized to calculate the hydrodynamic loads on the structure.

3.2. Description of the Operating Environmental Conditions

The case study focused on the SSI-COV-based structural modal identification under three main environmental conditions, i.e., irregular waves, turbulent wind, and combined wave and wind conditions. Although the OWT operates in a complex environment with both wave and wind, the use of pure wave or wind excitation allows a detailed investigation of the mechanism of jacket OWT modal identification under different environmental conditions.

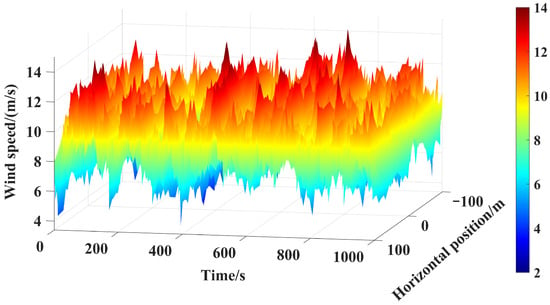

The JONSWAP spectrum [45] was used for the sea state simulation. A total of 187 sea states were applied, as shown in Table 2, with the peak period (Tp) ranging from 0.5 s to 16.5 s and the significant wave height (Hs) ranging from 6.5 m to 16.5 m. The wave direction aligns with the FA direction of the structure. For turbulent wind conditions, 57 groups were selected as shown in Table 3, covering wind speeds from 0.5 m/s to 30 m/s, with corresponding turbulence intensity ranging from 13.11% to 49.7%. The stochastic, full-field, turbulent wind was simulated using TurbSim [46] based on standard B of the IEC Kaimal spectral model. Figure 2 shows the 3D map of a turbulent wind simulated by Turbsim, reflecting the stochastic statistical characteristics of turbulent wind speeds for a duration of 1000 s, with an average wind speed of 9.5 m/s, a turbulence level of 18.75%, a horizontal width of 200 m, and centered at a hub height of 119 m. The simulated wind speeds were fed into the Inflow Wind module of FAST. The wind also aligns with the FA direction of the OWT. A total of 600 combined wave and wind conditions were included as shown in Table 4, with wind speeds ranging from 2 m/s to 30 m/s (and Tp from 0.5 s to 16.5 s with Hs from 6.5 m to 16.5 m as already mentioned above). The values of Hs, Tp, and wind turbulence intensity, were widely selected covering the most interesting ranges. Their combinations almost cover all real operating environmental conditions, effectively facilitating the exploration of the method’s applicability.

Table 2.

Irregular wave conditions.

Table 3.

Turbulent wind conditions.

Figure 2.

The 3D turbulent wind map at a turbulence level of 18.75% simulated by Turbsim.

Table 4.

The combined wind and wave conditions.

3.3. Vibration Response and Processing

Acceleration responses serve as the input for modal parameter identification based on SSI-COV. Five channels of acceleration responses, denoted by A1 to A5, are assumed to be monitored. The synthetic signals of tower accelerations at different positions were generated based on numerical simulations. Their positions are illustrated in Figure 1. These recorded acceleration data are along the X- and Y-axes of the global reference coordinate system, and the responses serve as input for modal identification in the FA and SS directions, respectively. The duration of each synthetic monitoring record was assumed to be 10 min for each environmental condition. The sampling frequency is 20 Hz.

Synthetic signals were polluted by noise for more realistic signal simulations. Gaussian white noise at a noise level of 5% was added. The white noise, characterized by a mean of 0 and variance of 1, is scaled by the root mean square of the signal, with the noise level expressed as a percentage. The noise level is described as

where x denotes the true response, and s is the noise-polluted signal. The identification results under different environmental conditions are discussed based on the synthetic response signals with 5% noise. To provide a more objective evaluation of the method, the effect of low noise levels ranging from 0% to 30% on the identification results is further studied.

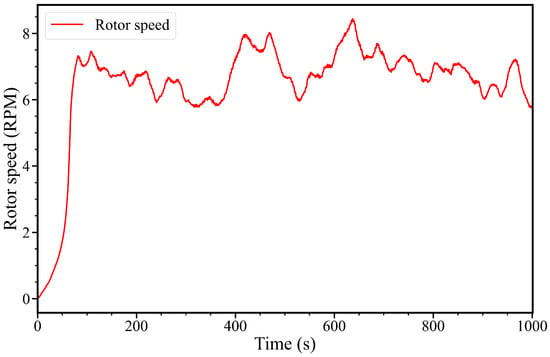

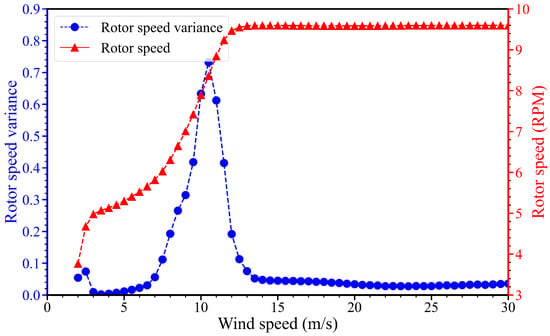

Understanding the dynamic properties of the OWT during operation is essential for analyzing the influence on modal parameter identification. Figure 3 illustrates the time series of rotor speed for a wind speed of 9.5 m/s. The average rotor speed and coefficient of variance for the rotor speed varying with different wind speeds are illustrated in Figure 4. The transient effect of the structural dynamics right after the startup of the wind turbine is truncated. The average and variance of the rotor speed were calculated for the period from 400 s to 1000 s. The structure operates in a non-generating state before reaching the cut-in wind speed of 4m/s with a notably low average rotor speed. For the wind speeds between the cut-in and the rated (i.e., 4 m/s and 11.4 m/s) magnitudes, the turbine operates below its rated power. Consequently, the average rotor speed gradually rises as the wind speed increases. Upon surpassing the rated wind speed, the turbine reaches the rated power operation, while the average rotor speed remains constant due to the servo control. The high variability of the rotor speed within the range of 8 m/s to 12 m/s is primarily related to the significant stochastics of the wind turbulence. The potential influence of rotor speed variations on identification results is discussed in the subsequent analysis.

Figure 3.

Rotor speed time history at a wind speed of 9.5 m/s.

Figure 4.

Average rotor speed and variance of the rotor speed over different wind speeds.

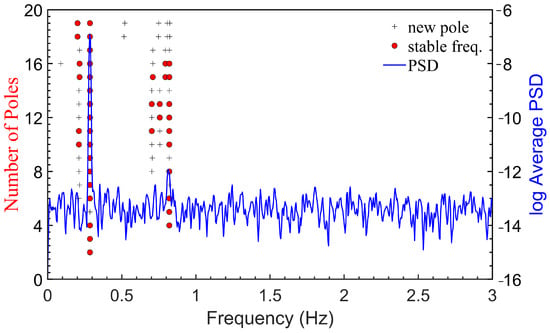

3.4. Validation of Modal Parameters Identification Method

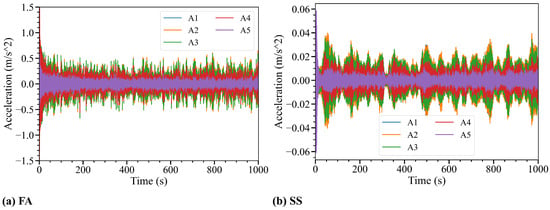

The applied SSI-COV method for jacket OWT modal parameter identification was first validated based on white noise excitation loads. The signals were generated based on the accelerations under the white noise excitation along the FA directions. Figure 5 shows the five channels of acceleration responses.

Figure 5.

Acceleration response signals in FA and SS directions excited by a white noise spectrum.

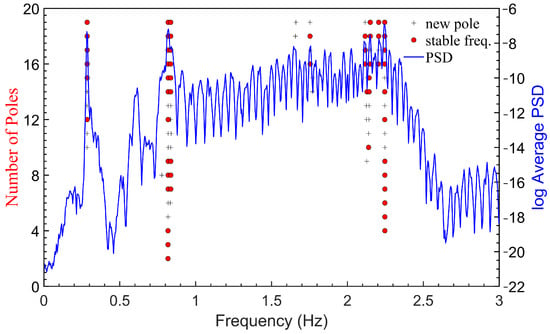

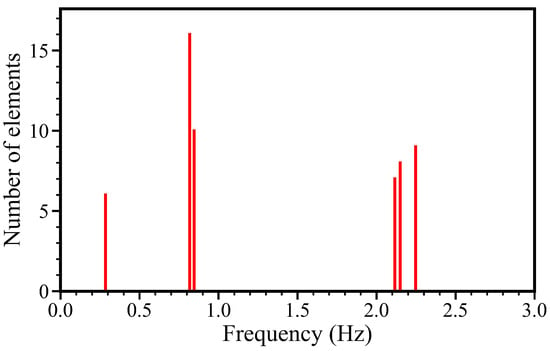

The stabilization diagram using 10 min of acceleration in the FA direction under a white noise condition is shown in Figure 6. Figure 7 shows the consequent selection of stable modes of the stability diagram in Figure 6 using the hierarchical clustering algorithm. Each cluster is characterized by a vertical line, the horizontal axis denotes the mean natural frequency of the cluster, and the vertical axis represents a height of the line equal to the number of elements inside the cluster. Clusters with more than 5 elements are considered to be physical modes of the structure.

Figure 6.

Stabilization diagram using 10 min acceleration response in the FA direction of the OWT when excited by white noise.

Figure 7.

Clustering results of the stable points under a white noise condition.

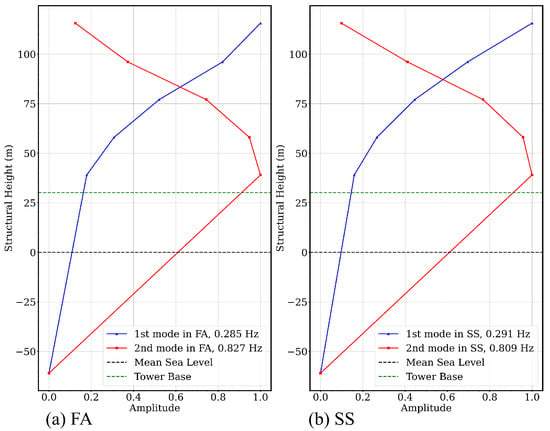

The first two FA/SS modes for the operating OWT were extracted using the peak-picking method based on tower acceleration responses computed by FAST under Gaussian white noise conditions [47]. The first two modal frequencies in FA direction of the overall structure were identified as 0.285 Hz and 0.827 Hz. The modal frequencies and shapes of these two modes were taken as the reference mode values. It should be emphasized that these two modes should be considered as the first two FA modes of the integrated global OWT structure under its operating condition. The reference mode shapes are shown in Figure 8. The MAC was introduced to describe the differences between the identified mode shape and the reference mode shape,

where and are the two modes, with T denoting vector transpose. A MAC value closer to 1 indicates a higher similarity between the two modes.

Figure 8.

The first two reference mode shapes in FA/SS directions.

The first two modes identified by SSI-COV and reference modes are presented in Table 5. The results indicate an accurate identification of the first two natural frequencies and modes in both the FA and SS directions for the white-noise excitation. The first modes for the FA and SS directions are crucial for fatigue life analysis, while the second modes in both directions contain valuable structural stiffness information for model correction and damage identification [26]. The identification of the higher-order modes under operational conditions is still challenging. Hence, the discussion in this study is limited to the first two modes.

Table 5.

The first two FA/SS modes using SSI-COV and FAST.

4. Modal Parameter Identification Results

4.1. Identification Under Irregular Wave Excitation

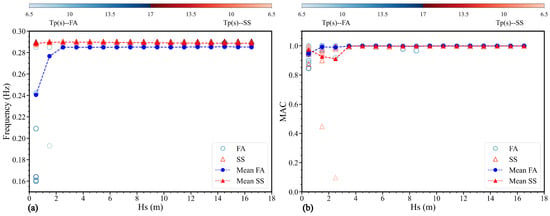

4.1.1. First FA/SS Modes

The identification results for the first modes excited by irregular wave conditions are illustrated in Figure 9. Figure 9a,b describes the first natural frequencies and MACs of the identified modes, respectively. The legends of FA and SS denote the modes identified under different sea states with varying Hs and Tp in the two directions, respectively. The legends of mean FA and mean SS represent the average values of the modal identification results for environmental conditions with variation in Tp. The results indicate that the identified first FA natural frequency is significantly lower than the reference value for Hs of 0.5 m, leading to the appearance of several spurious modes. The identified natural frequencies were also deviated from the reference ones for Hs of 1.5 m, due to the relatively low excitation energy. In addition, this might also reveal a research potential of methodology modification to eliminate identified skeptical modes. For Hs larger than 2 m, such an increase in wave energy led to much more accurate identification results of the frequencies for varying values of Tp. The first FA MACs showed high accuracy for all conditions. It is also worth mentioning that the identified first natural frequencies in SS direction demonstrate high accuracy under different wave conditions. However, there are instances of incorrect MAC identification at Hs values of 1.5 m and 2.5 m. Based on Figure 9b, it seems that reliable identification of modal shapes requires higher wave energy compared with modal frequency identification.

Figure 9.

The identified first FA and SS modes for irregular wave conditions: (a) the natural frequency, and (b) the MAC. Note that the gradient color bars represent variations in Tp from 6.5 s to 17 s in the irregular wave excitation conditions, the blue color indicates FA, and the red color is SS.

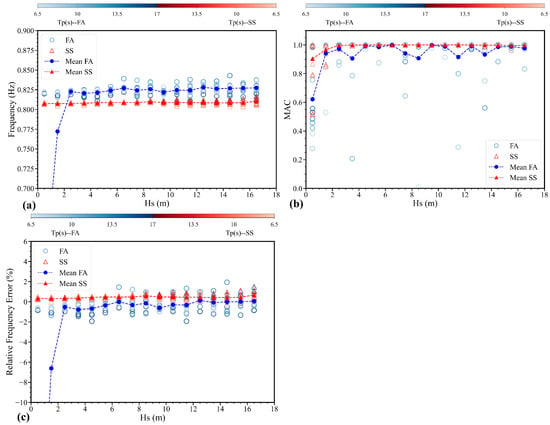

4.1.2. Second FA/SS Modes

Figure 10 represents the second FA/SS modes for irregular wave conditions. Similarly, the mean FA/SS represents the average identified values for different Tp conditions with a fixed value of Hs. For the FA direction, it is observed that the errors in identifying second frequencies are large for low values of Hs. In reality, the true structural modes for jacket OWTs are usually unknown. Misidentification could result in a mismatch of modal order. In one particular condition, as shown in Figure 11 and Figure 12, it shows that the first three natural frequencies are 0.209 Hz, 0.285 Hz, and 0.82 Hz. The 0.285 Hz is incorrectly considered to be the second natural frequency, resulting in a notable error compared to the second reference natural frequency. In cases with high Hs, the second natural frequencies can be identified accurately, with identification errors within −2% to 2%. This suggests that variations in Tp have a less critical impact on the identification results. The accuracy of the identified second FA MAC is significantly reduced, and reaches the lowest value at a Hs of 0.5 m, with a mean value of only 0.6. The errors of the second MAC are high in a few cases, but low in most conditions. For the SS direction, it is shown that the estimation of the second natural frequencies and MACs were stable under most irregular wave conditions, with minimal variability as Tp changes.

Figure 10.

The second FA/SS modes for irregular wave conditions: (a) the second natural frequency, (b) the second MAC, and (c) the relative frequency error. Note that the gradient bars represent variations in Tp from 6.5 s to 17 s for the pure wave excitation conditions, the blue color indicates FA, and the red color is SS.

Figure 11.

Stabilization diagram using the 10 min of a condition where Hs is 0.5 m, Tp is 10.5 s.

Figure 12.

Clustering results of the stable points under a condition where Hs is 0.5 m, Tp is 10.5 s.

The SSI-COV method was shown to be generally applicable to the identification of the first modes under most pure irregular wave conditions which do not strictly meet the fundamental assumptions of white-noise excitation. The identification for the first natural frequency in FA direction and the first MAC in SS direction were inaccurate for low wave energy conditions. The identification performance of the method for the second mode in the SS direction is better than that in the FA direction.

4.2. Identification Under Turbulent Wind Excitation

4.2.1. First FA/SS Modes

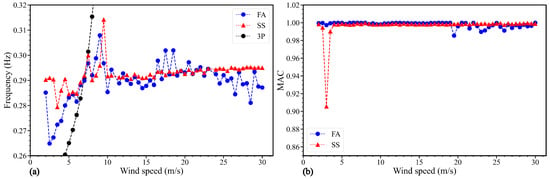

Figure 13 shows the results of the first FA/SS modes of the structure excited by the pure turbulent wind. The label of 3P dedicates the three times harmonic frequency calculated using the average rotor speed. For the FA direction, the identification error of the first natural frequency near the rated wind speed condition is large, and the maximum identification error reaches 7.72% at an averaged wind speed of 9.5 m/s. The wind speed varies throughout the entire duration leading to the large variation in the rotor speed as shown in Figure 3. The non-stationarity of the structural response ultimately leads to the largest errors in the identification of the first natural frequency at this particular wind speed of 9.5 m/s. The first natural frequency identified at the wind speed of 6.5 m/s overlaps with the 3P harmonic. The identified first natural frequency is notably lower than the reference one for wind speeds smaller than 5.5 m/s. It is probably due to the unsteady state of the turbine with a low and varying rotor speed. It is found that for wind speeds higher than the rated wind speed, the first FA natural frequency can be successfully identified. There was an error of about 2% (higher than the reference value) which is acceptable. It could be due to the blade stiffening or gyroscopic effect that has increased the first natural frequency in operational conditions [26]. For the SS direction, there was a similar phenomenon of the poorest identification performance near a wind speed of 10 m/s with an error of 8.2%. For this case, lower first natural frequencies were identified compared to the actual frequency values for low wind speeds. The first MAC could be identified accurately in both FA and SS directions.

Figure 13.

The first FA/SS modes for turbulent wind conditions: (a) the first natural frequency, (b) the first MAC.

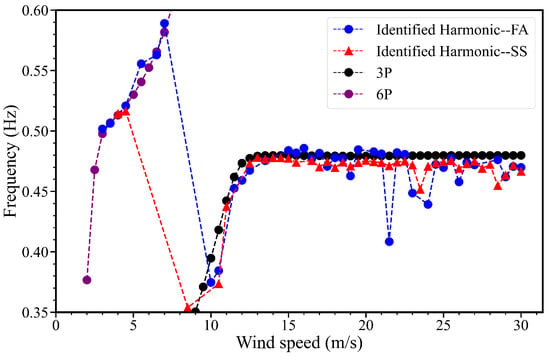

Figure 14 shows the identified harmonic frequencies for different wind speeds, 3P and 6P harmonics are the three times and six times harmonic frequencies. They might interfere with the identification results during the automatic identification process. Thus, the harmonics should be eliminated in the structural safety assessment. The identified harmonic-FA and identified harmonic-SS are the harmonic frequencies identified in the FA and SS directions, respectively. The identified harmonic frequencies were selected based on the known blade rotor speeds. The results show that 3P and 6P could be identified in the FA and SS directions at different wind speeds. However, the results show that they are not identified precisely in all conditions, particularly between 21.5 m/s to 25 m/s. Such identification error might be caused by the stochastic property of the data, interference with other excitations, etc.

Figure 14.

The identified harmonic frequencies for turbulent wind conditions.

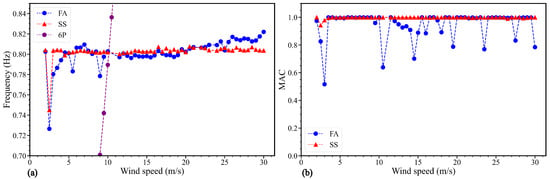

4.2.2. Second FA/SS Modes

Figure 15 shows the identified second modes under turbulent wind conditions. In the FA direction, the identified values were generally lower than the reference structural modes for the wind speed lower than 22 m/s, with errors up to 2.5%. The identified second natural frequency is close to the reference value for wind speeds higher than 22 m/s. The effect of low wind speed on the identification of the second natural frequency is less than the first. The second natural frequency and second MAC in the SS direction can be accurately identified, but with larger errors in some cases. The identification performance of the second FA MAC is worse than that in the SS direction. Similar findings have been observed in the study [26], where many MAC values were identified as relatively poor. It was suggested that the MAC value above 0.6 is reasonable for OWTs during operation.

Figure 15.

The identified second modes for different turbulent wind conditions: (a) second frequency, (b) second MAC.

The SSI-COV method was applied to the modal parameters identification of the jacket OWT structure for gust wind conditions with different turbulence, which indicates that the performance of the method is excellent for wind speeds higher than the rated speed. The SS direction demonstrates a considerably higher identification performance than the FA direction.

4.3. Identification Under Combined Wind and Wave Excitation

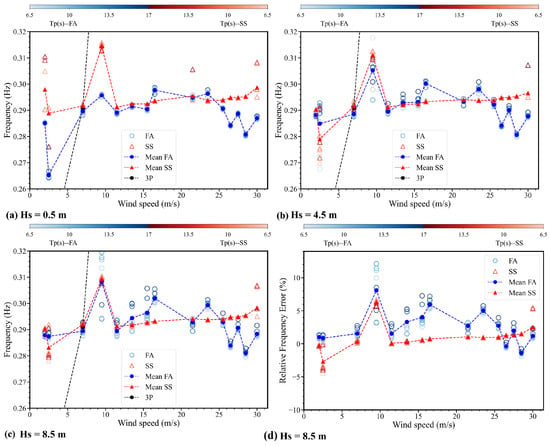

4.3.1. First FA/SS Modes

The identified first modal parameters under the combined irregular wave and turbulent wind conditions are shown in Figure 16 and Figure 17. The mean FA and mean SS represent the average modal identification values for variations in Tp and wind speeds. At low wind speeds of around 2.5 m/s, the identified first natural frequency for the FA direction is significantly lower than the reference value at the Hs of 0.5 m with a maximum error of 7.0%, and as the Hs increases, the error of the identified value decreases significantly. The 3P is close to the reference value of the first natural frequency at a wind speed of 7 m/s, and the identified values are close to 3P. This indicates that the harmonic frequency interferes with the identified results when the harmonic frequency is close to the real structural frequency. Hence, the results are not convincing. At the wind speed of 9.5 m/s, the identified first natural frequency is much higher than the reference value, which is similar to the cases for pure wind excitation. The average maximum error reaches 8.1% at a wind speed of 9.5 m/s and Hs of 8.5 m. The error is magnified as Hs increases, and the identified values are more dispersed across Tps, making the identification results more complex, with maximum errors exceeding 10%. The identification is more accurate when the wind speed is higher than the rated wind speed of 11.4 m/s with a maximum error of 3.5%.

Figure 16.

The first frequency at different Hs for combined wave and wind conditions. Note that the gradient bars represent variations in Tp from 6.5 s to 17 s, the blue color indicates FA, and the red color is SS.

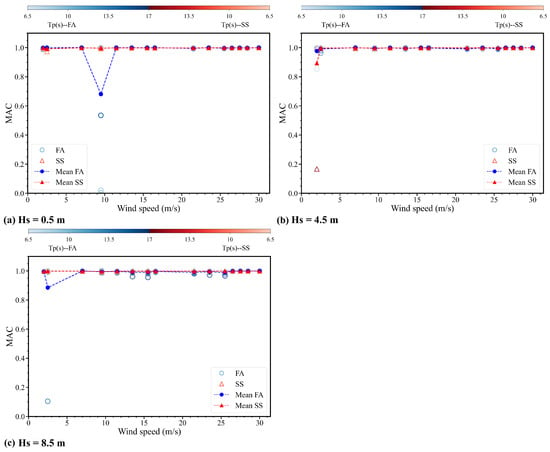

Figure 17.

The first MAC at different Hs for combined wave and wind conditions. Note that the gradient bars represent variations in Tp from 6.5 s to 17 s, the blue color indicates FA, and the red color is SS.

For the SS direction, the identified first natural frequencies at a wind speed of 2.5 m/s are much lower than the reference values. Additionally, with the variation in Tp, the identified values are scattered, especially at the low Hs. The error of the identified values is the largest when the wind speed nears the rated wind speed, which is similar to the FA direction. The identified values are generally accurate when the wind speed is higher than 11.4 m/s. The method shows excellent identification performance, with no observed dispersive values as Hs and Tp vary.

The accuracy for the first MACs in both directions is generally high, while some conditions might still lead to identification errors.

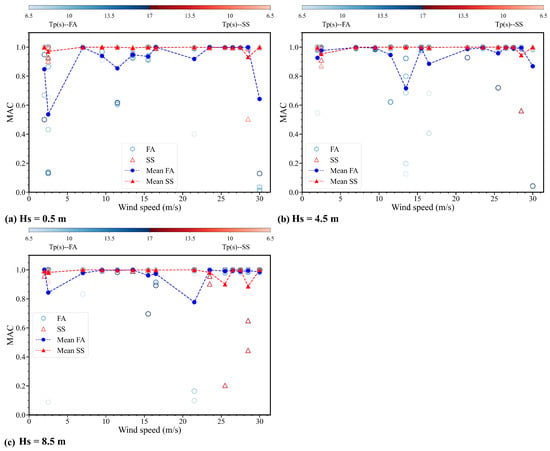

4.3.2. Second FA/SS Modes

The identified second modal parameters under the combined irregular wave and turbulent wind conditions are shown in Figure 18 and Figure 19. The mean FA and mean SS represent the average modal identification values for variations in Tp and wind speeds. The second FA natural frequency is focused upon. The second natural frequency is lower than the reference value at the wind speed of 2.5 m/s, Hs of 0.5 m, with a maximum error of s 7.3%. As Hs increases, the identification values vary greatly for variation in Tp conditions with a maximum error of 7.3%. The irregular wave with different Hs and Tp has a significant effect on the identification of the second FA natural frequency compared to the pure wind conditions. The results indicate that the second natural frequency for the SS direction could be accurately identified in general conditions, except for some conditions at a wind speed of 2.5 m/s.

Figure 18.

The second frequency at different Hs for combined wave and wind conditions. Note that the gradient bars represent variations in Tp from 6.5 s to 17 s, the blue color indicates FA, and the red color is SS.

Figure 19.

The second MAC at different Hs for combined wave and wind conditions. Note that the gradient bars represent variations in Tp from 6.5 s to 17 s, the blue color indicates FA, and the red color is SS.

The identified second MAC for the SS direction is generally higher than 0.8, demonstrating high accuracy. However, there are more cases with high errors in the second FA MAC than in the SS direction.

For combined wave and wind conditions, it is indicated that the first modes could be accurately identified for wind speed higher than the rated speed. The identification accuracy of the second natural frequency in the SS direction is generally high. However, in the FA direction, the identification values exhibit increased dispersion and reduced accuracy, particularly at higher Hs. The identification performance of the method in the SS direction is significantly more outstanding than in the FA direction.

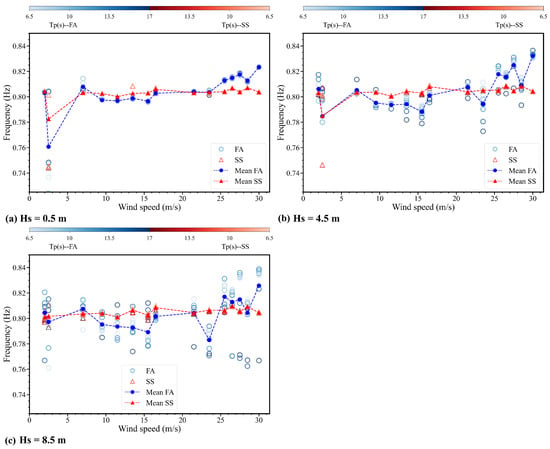

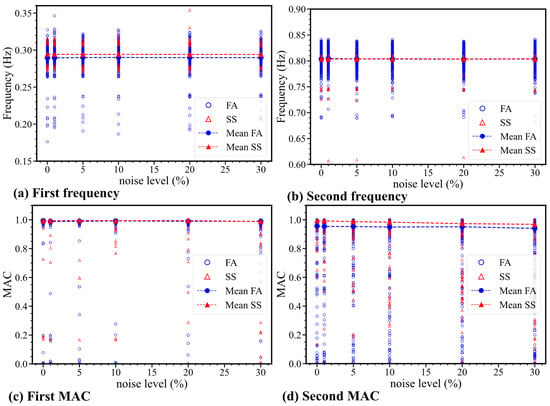

4.3.3. Effect of Signal Noise

The previous discussion was conducted based on acceleration responses with 5% noise level. However, it is equally important to investigate whether noise levels affect the identified results. Noise levels ranging from 0% to 30% were considered, adding to the response of the structure under combined turbulent wind and irregular wave conditions, with a total of 600 groups with combined wave and wind conditions. Figure 20 illustrates the first two modes for combined wave and wind conditions across different noise levels. Interestingly, we observed minimal variation in the first two frequencies across different noise levels. However, with an increase in noise level, the number of cases with decreased accuracy in MAC identification increased. Furthermore, a comparison of the identification results for different noise levels under specific conditions was conducted. It reveals minor variations in the identified natural frequencies but significant variations in the identified modes across different noise levels. The results suggest that signal noise levels have little impact on the identification of natural frequencies but significant effects on the mode shape identification. Moreover, it is worth mentioning that few significantly deviated identification results were presented. Some examples were observed that the identified first FA frequency was lower than 0.2 Hz or MAC value was as low as 0.05 for a few other cases. In practice, these significantly deviated results may be excluded based on accumulated field knowledge after a period of in situ structural monitoring when neighboring data can provide sufficient confidence against the newly identified deviated results. This can be practically important and could be studied in detail in future research.

Figure 20.

The first two modes of OWT by combined wave and wind conditions under different noise levels.

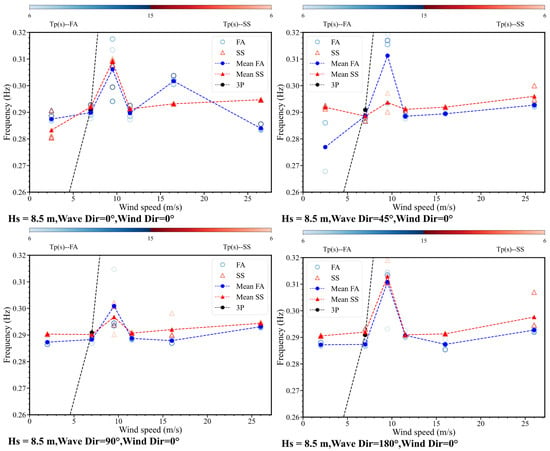

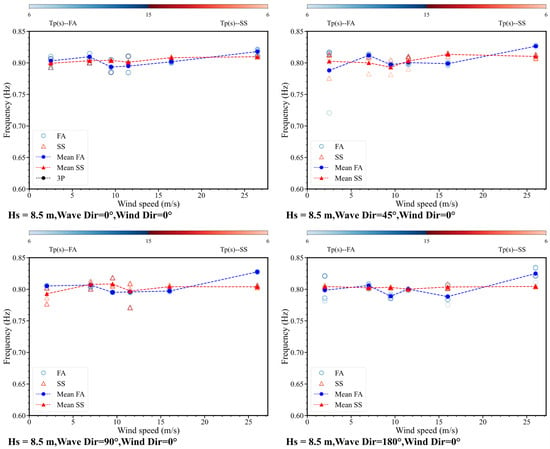

4.3.4. Effect of the Excitation Direction of the Wave and Wind

The system identification results primarily consider conditions where wind and waves are aligned. However, OWTs are typically subjected to environmental excitations with wind and wave directions at certain angles, closer to broadband excitations. When wind and waves are aligned, the excitation tends to be narrower. To minimize the influence of environmental parameters on the results, comparisons were conducted under specific conditions. The identified first and second natural frequencies for variation in wave directions while at a wind direction of 0° are illustrated in Figure 21 and Figure 22, respectively. The results indicate that as the wave direction increased, the first FA natural frequency tended to stabilize when the wind speed exceeded the rated speed, showing a significant improvement compared to conditions where both wave and wind directions were 0°. However, the identification performance remains poor near a wind speed of 9.5 m/s, indicating that the instability of rotor speed significantly affects the identification results, surpassing the impact of the direction of excitations. The second natural frequencies in the SS direction become unstable. The results may suggest that the larger angle between wind and waves while maintaining the wind angle perpendicular to the SS direction, improves the identification performance in the FA direction. This is possibly due to the method being more suitable for broadband excitations.

Figure 21.

The first frequency for variation in wave directions, while at a wind direction of 0°.

Figure 22.

The second frequency for variation in wave directions, for a constant wind direction of 0°.

5. Modal Identification Based on Experimental Data

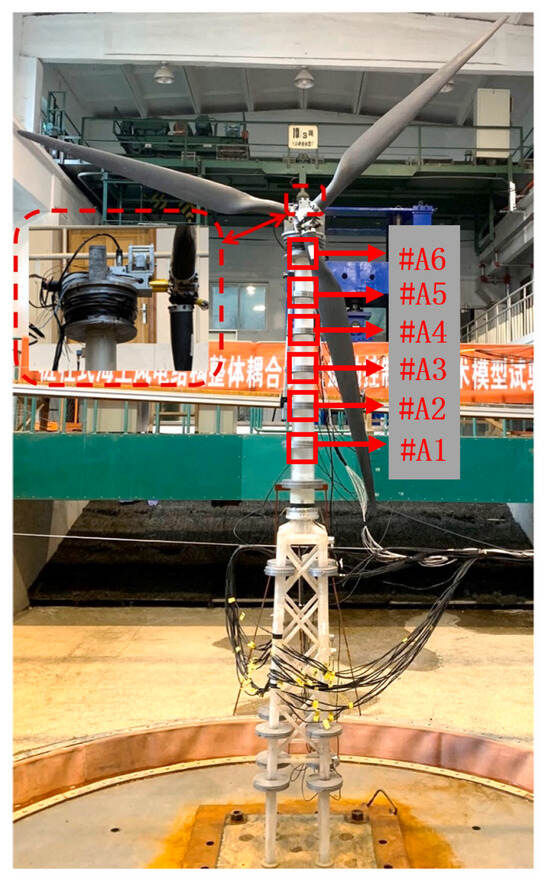

5.1. Description of the Scaled Model Test

The aforementioned findings were further verified by using data from a scaled (1:75) 10 MW jacket-type OWT model testing [42,48]. The corresponding full-scaled model is described in Table 1. Table 6 shows the main scaling coefficients applied according to the structural elastic similarity, aerodynamic similarity, and hydrodynamic similarity theories. The considered environmental conditions are summarized in Table 7 in full scale and Table 8 in model scale, respectively. The considered environmental conditions include pure regular waves (i.e., LC1 and LC2), pure steady wind (i.e., LC3 and LC4), and combined wind and waves (i.e., LC5 and LC6). The sampling frequency was downsampled to 100 Hz to improve the computational efficiency. Figure 23 illustrates the scaled modeling test. Acceleration sensors were positioned at six locations along the tower (i.e., #A1, #A2, #A3, #A4, #A5, and #A6) to record horizontal accelerations in FA direction at a sampling frequency of 512 Hz over 330 s.

Table 6.

The similarity relationships between the full and scaled models.

Table 7.

The loading conditions in full scale.

Table 8.

The loading conditions in model scale.

Figure 23.

The test configurations.

The first natural frequency of the structure was calculated to be 2.87 Hz according to the fast Fourier transform of the response time series [48].

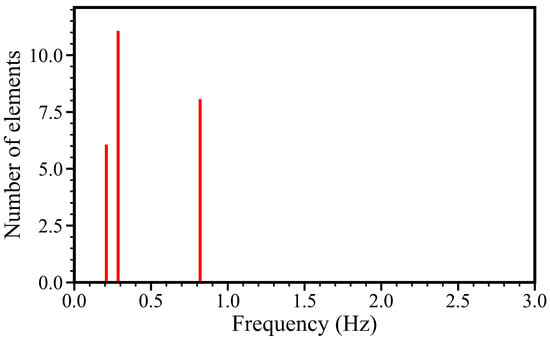

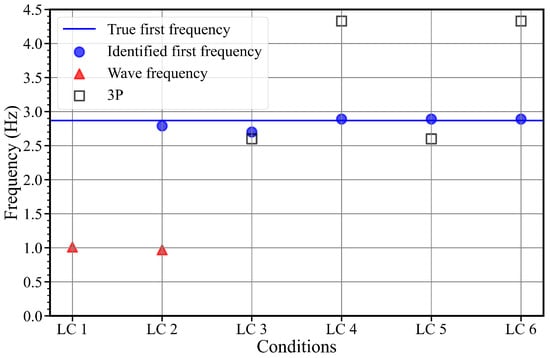

5.2. Modal Parameter Identification Results for the Scaled Test

The applicability of SSI-COV method was tested using the recorded acceleration time series for the six loading conditions. The first structural modal frequency in FA direction was estimated accordingly, as shown in Figure 24. Under wave excitation conditions (LC1 and LC2), the frequencies of 1.01 Hz and 0.97 Hz were identified, respectively. These correspond to the wave excitation frequencies, instead of the reference first modal frequency. In addition, the fundamental natural frequency was misjudged as the second-order frequency in LC2, with a wave height of 0.04 m. However, the identification results contained only wave frequency information without the actual fundamental frequency in LC1 with a wave height of 0.02 m. This may be related to the lack of excitation in the frequency range of interest in LC1. However, LC2 with higher Hs has the potential to excite the structure’s fundamental frequency, and this also has been identified.

Figure 24.

Modal parameter identification results for the scale test.

For the steady wind conditions (LC3 and LC4), the OWT was operating under partial power and full power states, respectively, with 3P at 2.6 Hz and 4.2 Hz. For LC3, the 3P frequency is close to the first structural modal frequency, resulting in a slightly lower identified result of 2.7 Hz. However, for LC4, the identified value is accurate. This demonstrates the SSI-COV is able to identify the first natural frequency under full-power operating conditions.

For the combined wind and wave conditions (LC5 and LC6), the first modal frequency was accurately identified without the wave frequency. It indicates that the combined wind and wave excitations helped eliminating the interference caused by wave-induced harmonic frequency.

Given the constraints of the laboratory equipment, the test load conditions were limited to regular waves and steady wind. However, these conditions still partially confirm the findings by numerical studies in the previous section, particularly regarding the impact of rotor harmonics on the accuracy of modal identification. Further research incorporating actual wind farm monitoring data will be essential for deeper exploration.

6. Conclusions

This research explores the impact of various environmental operating conditions on the modal parameter identification for a jacket OWT structure. The numerical model of a 10MW jacket-typed OWT was set up using FAST.v8. The modal parameters under operating conditions were identified using an automated SSI-COV approach. In addition, experimental data based on a scaled 10MW jacket-type OWT was used for the verification of findings. The conclusions are as follows:

- The first two modal parameters of the OWT structure can be accurately obtained in the majority of irregular wave conditions, except for the cases with very small Hs. Only irregular wave excitation has limited influence on the identification accuracy but requires a sufficiently strong energy.

- Under gust wind conditions with different turbulence, the method performs well when wind speeds exceed the rated speed of 11.4 m/s. The 3P or 6P harmonic is between the first and second frequencies, which interfere with the identification results during the automatic identification process. But those 3P and 6P frequencies can be easily eliminated as they are known values. For wind speed near the rated value, the identification accuracy was highly affected due to the significant nonstationary effect, with the identified error reaching up to about 7%.

- The first modes can be accurately identified for wind speed higher than the rated speed in conditions of gust wind combined with irregular waves. With the increase in Hs, the identification of the second mode in the FA varies greatly in different Tp conditions with errors fluctuating by approximately 8% compared to the reference modes. However, the second mode in the SS direction can be identified accurately.

- The method is more suitable for applications under broadband excitation, and the identification of first FA natural frequencies is improved by appropriately increasing the angles of wave and wind from 0° to 180°. However, the effect of rotor speed variation on the identification is significantly higher than that of the wave and wind pinch angle, especially when the rotor speed variance is large. The performance in SS consistently outperformed the FA direction under all conditions.

This study suggests the good applicability of SSI-COV method-based structural modal identification for wind speed larger than the rated speed with significant wave energy. Further studies might consider methodology modification to enhance the performance of modal identification under specific conditions with significant identification errors. Last but not least, it is challenging but very interesting to continue to validate relevant techniques using more comprehensive experimental data as well as in situ offshore monitoring and inspection data from engineering projects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z. and X.H.; methodology, C.Z. and C.L.; software, C.Z.; validation, C.Z.; formal analysis, C.Z. and X.H.; investigation, C.Z.; resources, C.Z. and X.H.; data curation, D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.H., B.J.L., S.S., W.S. and C.L.; visualization, C.Z.; supervision, X.L. and X.H.; project administration, X.L. and X.H.; funding acquisition, X.L. and X.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFB4201300). This paper is also partially funded by Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (DUT22RC(3)069).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- REN21. Renewables 2023 Global Status Report; Technical Report; REN21: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Global Wind Energy Council. GWEC|Global Wind Report 2023; Technical Report; Global Wind Energy Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Wind Energy Association. EWEA| The Economics of Wind Energy; Technical Report; European Wind Energy Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- van Vondelen, A.A.; Navalkar, S.T.; Iliopoulos, A.; van der Hoek, D.C.; van Wingerden, J.W. Damping identification of offshore wind turbines using operational modal analysis: A review. Wind. Energy Sci. 2022, 7, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajrić, A.; Høgsberg, J.; Rüdinger, F. Evaluation of damping estimates by automated operational modal analysis for offshore wind turbine tower vibrations. Renew. Energy. 2018, 116, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devriendt, C.; Magalhães, F.; Weijtjens, W.; De Sitter, G.; Cunha, Á.; Guillaume, P. Structural health monitoring of offshore wind turbines using automated operational modal analysis. Struct. Health Monit. 2014, 13, 644–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Ma, J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, R. Automated eigensystem realisation algorithm for operational modal analysis. J. Sound Vib. 2014, 333, 3550–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustyn, D.; Smolka, U.; Tygesen, U.T.; Ulriksen, M.D.; Sørensen, J.D. Data-driven model updating of an offshore wind jacket substructure. Appl. Ocean Res. 2020, 104, 102366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, B.; Mehrjoo, A.; Moaveni, B.; McAdam, R.; Rüdinger, F.; Hines, E. System identification and finite element model updating of a 6 MW offshore wind turbine using vibrational response measurements. Renew. Energy. 2023, 219, 119430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Fan, S.; Xu, Q. Using Bayesian updating for monopile offshore wind turbines monitoring. Ocean Eng. 2023, 280, 114801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, P.; Brincker, R.; Peeters, B.; De Roeck, G.; Hermans, L.; Krämer, C. Comparison of system identification methods using ambient bridge test data. In Proceedings of the 17th International Modal Analysis Conference (IMAC), Kissimmee, FL, USA, 8–11 February 1999; Society for Experimental Mechanics: Aalborg, Denmark, 1999; pp. 1035–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Luo, Y.; Karney, B.W.; Wang, Z.; Zhai, L. Virtual testing for modal and damping ratio identification of submerged structures using the PolyMAX algorithm with two-way fluid–structure Interactions. J. Fluids Struct. 2015, 54, 548–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brincker, R.; Zhang, L.; Andersen, P. Modal identification of output-only systems using frequency domain decomposition. Smart Mater. Struct. 2001, 10, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, H.A., Jr. On-Line Failure Detection and Damping Measurement of Aerospace Structures by Random Decrement Signatures; Technical Report; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Juang, J.N.; Pappa, R.S. Effects of noise on modal parameters identified by the eigensystem realization algorithm. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 1986, 9, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, G.H. The natural excitation technique (NExT) for modal parameter extraction from operating structures. J. Anal. Exp. Modal. Anal. 1995, 10, 260. [Google Scholar]

- Lardies, J. Modal parameter identification based on ARMAV and state–space approaches. Arch. Appl. Mech. 2010, 80, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, B.; De Roeck, G. Reference-based stochastic subspace identification for output-only modal analysis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 1999, 13, 855–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Overschee, P.; De Moor, B. Subspace algorithms for the stochastic identification problem. Automatica 1993, 29, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulriksen, M.D.; Tcherniak, D.; Kirkegaard, P.H.; Damkilde, L. Operational modal analysis and wavelet transformation for damage identification in wind turbine blades. Struct. Health Monit. 2016, 15, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, E.D.; Petrone, G.; Manzato, S.; Peeters, B.; Desmet, W.; Marulo, F. Damage detection in wind turbine blades by using operational modal analysis. Struct. Health Monit. 2016, 15, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzadeh, R.; Devriendt, C.; Bidakhvidi, M.A.; Guillaume, P. Experimental and computational damping estimation of an offshore wind turbine on a monopile foundation. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2013, 120, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijtjens, W.; Verbelen, T.; Capello, E.; Devriendt, C. Vibration based structural health monitoring of the substructures of five offshore wind turbines. Procedia Eng. 2017, 199, 2294–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, F.; Jiang, Z.; Yu, Q.; Liu, L. Investigation of dynamic characteristics of a monopile wind turbine based on sea test. Ocean Eng. 2019, 189, 106308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, F.B.; Ong, Z.C.; Khoo, S.Y. A review of operational modal analysis techniques for in-service modal identification. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2020, 42, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Mehr, N.P.; Moaveni, B.; Hines, E.; Ebrahimian, H.; Bajric, A. One year monitoring of an offshore wind turbine: Variability of modal parameters to ambient and operational conditions. Eng. Struct. 2023, 297, 117022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Moaveni, B.; Ebrahimian, H.; Hines, E.; Bajric, A. Joint parameter-input estimation for digital twinning of the Block Island wind turbine using output-only measurements. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 198, 110425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, F.; Cunha, A.; Caetano, E. Online automatic identification of the modal parameters of a long span arch bridge. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2009, 23, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brincker, R.; Ventura, C. Introduction to Operational Modal Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tygesen, U.; Worden, K.; Rogers, T.; Manson, G.; Cross, E. State-of-the-art and future directions for predictive modelling of offshore structure dynamics using machine learning. In Dynamics of Civil Structures, Volume 2: Proceedings of the 36th IMAC, A Conference and Exposition on Structural Dynamics 2018; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Popko, W.; Vorpahl, F.; Antonakas, P. Investigation of local vibration phenomena of a jacket sub-structure caused by coupling with other components of an offshore wind turbine. In Proceedings of the ISOPE International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference, Anchorage, AK, USA, 30 June–5 July 2013; ISOPE: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2013; p. ISOPE–I. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Tempel, J. Design of Support Structures for Offshore Wind Turbines; TU Delft: Delft, The Netherland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.; Lian, J.; Yang, M.; Wang, H. Operational modal identification of offshore wind turbine structure based on modified stochastic subspace identification method considering harmonic interference. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2014, 6, 033128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Lian, J.; Wang, H.; Yu, T.; Zhao, Y. Structural vibration monitoring and operational modal analysis of offshore wind turbine structure. Ocean Eng. 2018, 150, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partovi-Mehr, N.; Branlard, E.; Song, M.; Moaveni, B.; Hines, E.M.; Robertson, A. Sensitivity analysis of modal parameters of a jacket offshore wind turbine to operational conditions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzadeh, R.; Weijtjens, W.; Guillaume, P.; Devriendt, C. The dynamics of an offshore wind turbine in parked conditions: A comparison between simulations and measurements. Wind Energy 2015, 18, 1685–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Pan, J.; Huang, Z.; Miao, Y.; Jiang, J.; Wang, Z. Analysis of vibration monitoring data of an onshore wind turbine under different operational conditions. Eng. Struct. 2020, 205, 110071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, B. System Identification and Damage Detection in Civil Engineering. Ph.D. Thesis, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Leuven, Belgium, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cheynet, E.; Jakobsen, J.B.; Snæbjörnsson, J. Damping estimation of large wind-sensitive structures. Procedia Eng. 2017, 199, 2047–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, P.; Moaveni, B. Environmental effects on the identified natural frequencies of the Dowling Hall Footbridge. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2011, 25, 2336–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, C.; Zahle, F.; Bitsche, R.; Kim, T.; Yde, A.; Henriksen, L.C.; Hansen, M.H.; Blasques, J.P.A.A.; Gaunaa, M.; Natarajan, A. The DTU 10-MW reference wind turbine. In Proceedings of the Danish Wind Power Research 2013, Fredericia, Denmark, 27–28 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X. Experimental study of structural vibration control of 10-MW jacket offshore wind turbines using tuned mass damper under wind and wave loads. Ocean Eng. 2023, 288, 116015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkman, B.; Jonkman, J. FAST User’s Guide: Version 8.16.00; Technical Report; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bir, G. User’s Guide to BModes (Software for Computing Rotating Beam-Coupled Modes); Technical Report; National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmann, K.; Barnett, T.P.; Bouws, E.; Carlson, H.; Cartwright, D.E.; Enke, K.; Ewing, J.; Gienapp, A.; Hasselmann, D.; Kruseman, P.; et al. Measurements of wind-wave growth and swell decay during the Joint North Sea Wave Project (JONSWAP). Dtsch. Hydrogr. Z. 1973, A12, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Jonkman, B. Turbsim User’s Guide v2. 00.00; Technical Report; National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Wang, B. Vibration mitigation in offshore wind turbine under combined wind-wave-earthquake loads using the tuned mass damper inerter. Renew. Energy 2023, 216, 119050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, C.; Lu, D.; Zhao, S.; Wang, W.; Shang, J.; Li, X.; Liu, Q. Experimental study of ultra-large jacket offshore wind turbine under different operational states based on joint aero-hydro-structural elastic similarities. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 915591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).