Abstract

With the research on unmanned ships conducted by the International Maritime Organization, the European Union and China, the navigation risk of unmanned ships has become a hot topic around the world. Based on the research and development history and current situation of unmanned ships at home and abroad, focusing on the three key elements of “Unmanned Ship, shore-based control personnel, external navigation environment”, this study establishes a navigation risk index system for unmanned ships under complex navigation conditions, considering the particularity of the unmanned ship, its perception ability, environmental understanding, situation judgment, communication ability and other indicators. The analytic hierarchy process is used to solve the weight of all kinds of navigation risk factors, and a consistency test of the established index system is carried out. Through expert investigation, the fuzzy membership set of risk indexes is established, and a fuzzy comprehensive evaluation model is established to evaluate the navigation risk of unmanned ships under complex navigation conditions. To avoid the situation of single-factor information being inundated, this study adopts the method of fuzzy comprehensive evaluation from a low level to a high level, and it verifies the algorithm through cases, which proves the validity and rationality of the proposed risk assessment method.

1. Introduction

At present, the research of unmanned ships is a hotspot around the world. Unmanned ships are taken as a strategic development direction in relevant research institutions in different regions or countries, such as the European Union, the United Kingdom, Norway, Finland, Japan, South Korea, etc., who carried out the development of unmanned ships, classified unmanned ships, formulated corresponding guidelines, and established maritime test sites. The International Maritime Organization defined unmanned ships as maritime Autonomous Surface ships (MASSs), which began to establish the laws and regulations for unmanned ships and created a preliminary classification of unmanned ships.

In recent years, China has been actively promoting the research of unmanned ships. In May 2015, the “Made in China 2025” was released. It aims to accelerate the development of marine engineering equipment and high-tech ships, which is one of the ten key development areas. In March 2016, the China Classification Society issued the “Code for Intelligent Ships” [1], which clarified the technical development direction of future intelligent ships. In July 2017, the State Council issued the New Generation of Artificial Intelligence Development Plan [2]. The plan proposed that common technologies, such as the computing architecture of autonomous unmanned systems, perception and understanding of complex dynamic scenes, real-time accurate positioning, and adaptive intelligent navigation for complex environments, should be emphasized. In addition, intelligent technologies, such as autonomous control of drones and automatic driving of cars, ships and rail transit, can support the application of unmanned systems and industrial development.

The risk of autonomous ships under sail is an inevitable problem during operation, especially in complex navigation conditions, such as narrow waterways, waters with high traffic flow density, wind, waves, and bad natural conditions. Thus, the safe state of unmanned ships is of great concern for researchers, managers, ship owners, and insurance companies. The combined effect of various risk factors under complex navigation conditions may cause incalculable impacts and losses to unmanned ships, cargoes, and the marine environment. Therefore, in order to ensure the safe navigation of unmanned ships and avoid accidents, it is urgent to analyze and study the risks of unmanned ships under complex navigation conditions.

For ship-related risk assessment, recent research has focused on comprehensive safety assessments of container ships [3,4], risk assessment of ship navigation safety [5,6], risk assessment of a ship capsizing [7], risk assessment of ship oil spills [8], etc. Jiang Dan [9] from Wuhan University of Technology takes the complex weather conditions of the Three Gorges Reservoir as a background and analyzes the influencing factors of ship navigation safety. The index system is established, and the early warning and assessment of ship navigation risk are realized by using chromatography analysis and fuzzy comprehensive evaluation. There are also some typical risk warning results, such as the collision risk assessment of ships sailing in the Strait of Malacca based on Automatic Identification System (AIS) data [10,11], navigation risk prevention and control in crowded waters near shore [12], ship collision risk assessment based on traffic flow and ship field [8], and comparative study of various collision risk assessment methods [13,14]. In the field of risk assessment, the risk analysis system model of PAWSA (Port and Waterway Safety Assessment), which is widely used at present, was established and developed by the United States Coast Guard. PAWSA consists of four parts: risk source identification, risk event estimation, risk control methods, and risk control implementation measures. In addition, Zhen et al. [15] propose a novel collision risk assessment method for quantifying the risk of certain regions, which considers the aggregation density of ships. Li and Zhang [16] propose a collision avoidance decision method for unmanned surface vehicles, which is based on the improved velocity obstacle algorithm. Huang et al. [17] established a novel regional collision risk assessment framework for multi-ship encounters in order to identify the collision hotspots in complex waters.

Unmanned vessels present unique risk factors, such as the completeness of ship perception systems, the effectiveness of ship-to-shore communication, and the situation of shore-based personnel. These limitations pose challenges in adopting existing risk assessment methods or technologies designed for traditional ships. Meanwhile, the increasing complexity of navigational environments introduced by unmanned ships, particularly in congested ports or narrow waterways characterized by high traffic complexity and limited navigation capabilities, has heightened the challenges associated with risk assessment in intelligent ship navigation. This study refers to the traditional navigational risk assessment method of manned ships and fully considers the particularity of unmanned ships under complex navigational conditions, which not only considers the channel environment and the influencing factors of the natural environment but also adds the ship’s own influencing factors and human control factors into the entire evaluation system. In addition, this study determines the entire navigational safety assessment index system in a more comprehensive way. The research results will play a good role in promoting the development and application of unmanned ships.

2. Risk Assessment Index System for Unmanned Ships

2.1. Analysis of Navigation Risk Assessment Index of Unmanned Ships

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) classifies unmanned ships into four classes [18], termed as ‘Degree of Autonomy’: Class L1—ships with automated procedure and operation and decision-making assistance; Class L2—ships with remote control function and a crew on board; L3 Class—ships with remote control function but no crew on board; Class L4 ships that are completely autonomous in navigation. For Class L1, the primary risks are associated with automation and decision-making processes. For Class L2, the main risks arise from perception and communication aspects, encompassing the adequacy of ship perception systems and the efficacy of ship-to-shore communication channels. For Class L3, in addition to the aforementioned risks at Class L2, there are also concerns regarding onboard equipment reliability. For Class L4, navigation risks primarily stem from both the completeness and reliability of autonomous navigation systems themselves. Due to varying approaches and degrees of autonomy, different levels of unmanned ships encounter distinct navigation risks. Consequently, an assessment should be conducted on their specific navigation risks to ensure navigational safety for ships with differing levels of autonomy.

2.1.1. Factors Affecting Navigation Safety of Unmanned Ships

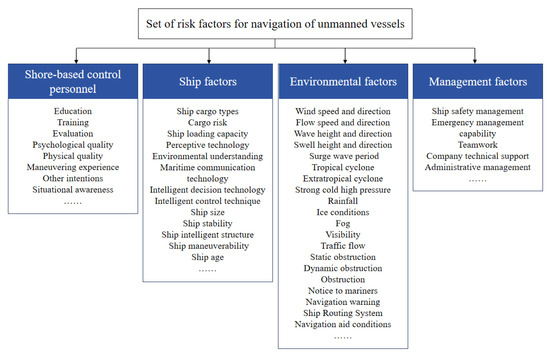

The safe navigation of unmanned ships is mainly affected by the following four factors: shore-based control personnel [19,20], ship factors, environmental factors, and management factors [1]. Based on the analysis of factors affecting the navigation safety of unmanned ships under a complex navigation environment, the navigation risk factor set of unmanned ships is sorted out, as shown in Figure 1, which is mainly divided into four aspects: shore-based control personnel, ship, environment, and management.

Figure 1.

Set of risk factors for navigation of unmanned ships.

In order to more accurately calculate and evaluate the navigation risks of unmanned ships under complex navigation conditions, this study adopts the expert questionnaire method [21] to screen, simplify, and synthesize the indexes of the navigation risk factor set of unmanned ships mentioned above. The expert questionnaire method is used because it is an efficient method to collect professional and representative evaluation information with high flexibility. Through expert questionnaires, this study identifies factors with the same system or influencing characteristics among various risk sources and simplifies and unifies them. Factors which are unreasonable or not applicable to unmanned ships shall be removed or replaced according to expert opinions. For example, navigation notices, navigation warnings, etc., are classified into the navigation aid conditions, and all management factors are deleted.

2.1.2. Index Screening of Navigation Risk of Unmanned Ships

According to the investigation results of the expert opinions on navigation risk indexes of unmanned ships in Section 2.1.1, navigation risk assessment indexes of unmanned ships under complex navigation conditions can be divided into 3 first-level indexes, 8 second-level indexes, and 18 third-level indexes. The details are as follows:

The first-level indexes: shore-based control personnel, ship factors, environmental factors.

The second-level indexes: professional skills, education and training, situational awareness, ship itself, perception and understanding, maritime communication technology, hydrometeorology, navigation environment.

The third-level indexes: ship size, ship maneuverability, ship age, ship loading condition, target recognition ability, navigation environment understanding, situation judgment, semantic understanding, communication bandwidth, communication type, communication reliability, wind level, rainfall, surge wave, visibility, traffic flow, obstruction, navigation aid conditions.

2.2. Assessment Index Weight Calculation

Based on the research content and summary experience of the MUNIN project [22] and the actual situation of relevant domestic unmanned ship R&D and operation companies, this study investigates and consulates corresponding cooperative institutions and colleges. The analytic hierarchy process (AHP) is used to solve the weight of all kinds of navigation risk factors in this study. The AHP can decompose complex problems into multiple levels, criteria and sub-criteria, establish a judgment matrix, and finally obtain the optimal decision scheme through the comparison and weight calculation of each level. The steps of AHP are listed as follows:

- Divide complex indexing system into multiple hierarchical levels.

- Based on expert judgment, express the relative importance of factors at higher levels according to the arrangement of factors at each level. This step is conducted by constructing the discriminant matrix.

- Then, determine the order weights of each factor’s relative importance within each level based on the maximum eigenvalue and its eigenvector derived from this matrix.

- Finally, by analyzing each level, obtain the overall ranking weight for the entire system.

The discriminant matrix is established through an expert questionnaire survey, and then the importance of the preliminary index is calculated. This section mainly carries out a consistency test and index weight calculation for the navigation risk assessment index system of unmanned ships. The values in the discriminant matrix represent the relative importance ratios between two factors and the higher-level objective factor. Typically, these ratios are assigned on a scale ranging from 1 to 9, with their reciprocals ranging from 1 to 1/9.

(1) Establish and analyze the navigation risk hierarchy diagram of unmanned ships under complex navigation conditions.

(2) Based on expert evaluation, the importance of the indexes is inferred through the mutual discriminant matrix of the first-level indexes, and the discriminant matrix of the first-level indexes is obtained, as shown in Table 1:

Table 1.

Discriminant matrix of the first-level indexes.

Specifically:

Similarly, the factors of each level and their corresponding sub-index factors are scored by experts, and the discriminant matrix of each level is obtained.

(3) For the calculation of the weight vector [23,24] of the first-level indexes, it is necessary to normalize and geometrically average the sequence of different primary index vectors. The geometrical average is less affected by extremes than the arithmetic mean. The corresponding calculation formula is shown in Equation (1):

where refers to the geometrically averaged row vectors.

The normalization calculation of the ranking index vector is shown in Equation (2):

Similarly, the following results can be obtained: ,

(4) Consistency test

Given the intricate nature of unmanned ship risk systems and the limited comprehension of individuals, experts’ evaluations sometimes result in an inconsistent discriminant matrix that fails to meet satisfaction, thereby leading to contradictions in expressing factor importance. Consequently, it becomes imperative to conduct a consistency test for the judgment matrix. Otherwise, the weights calculated would be unreasonable to some extent.

(1) We need to calculate the maximum eigenvalue of the discriminant matrix and then carry out the consistency test of the discriminant matrix according to the corresponding calculation formula. See Equation (4) for the calculation formula of the maximum eigenvalue :

(2) Calculation of CI and CR:

where CI refers to the consistency index, RI refers to the average random consistency index of the same order, and CR refers to the consistency test result. is the judgment matrix.

The CR value, which is less than or equal to 0.1, meets the corresponding criteria and meets the requirements of the consistency test.

According to the above hierarchical analysis method for obtaining the risk impact factor index weight, combining the navigation characteristics of unmanned ships and referring to the prior knowledge of manned ship risk assessment, the weight value of each assessment index of unmanned ship navigation risk is obtained. The weights of each risk index are shown in Table 2. The weights of each index of the navigation risk assessment of unmanned ships are obtained through calculation. When calculating the weights, CI and CR values are calculated to test the effectiveness of the discriminant matrix of weights. It is found that CR is less than 0.1, so the index system in Table 2 can be used.

Table 2.

Weight value of navigation safety evaluation index of unmanned ships.

By calculating all the consistency indexes and the average random consistency indexes of the same order, the total CI and RI can be obtained, and the consistency test of the above table can be realized. Through the above consistency test calculation and analysis, where the value of CR meets the requirement, it is concluded that the navigation risk assessment index system of unmanned ships established in this section meets the consistency test requirements. From the perspective of weight, factors, such as situational awareness, target recognition ability, communication reliability, and navigation aid conditions of shore-based control personnel, have a great impact on safe navigation under complex navigation conditions for unmanned ships.

4. Conclusions and Prospect

4.1. Conclusions

This study focuses on the navigation risk assessment of unmanned ships under complex navigation conditions. The conclusions are drawn as follows:

- (1)

- We reviewed the development status of unmanned ships worldwide, as well as the research status of risk assessment at home and abroad, to lay the foundation for establishing a risk assessment of unmanned ships under complex navigation conditions.

- (2)

- The risk assessment indexes of unmanned ships are analyzed and screened theoretically, the establishment process of the risk assessment index system of unmanned ships is expounded, and the risk factor indexes affecting the navigation safety of unmanned ships under complex navigation conditions are determined by using the analytic hierarchy process; a consistency test is also carried out.

- (3)

- The fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method is used to determine the membership degree of risk factors of unmanned ships under complex navigation conditions, and the algorithm in this study is verified through cases, where the navigation risk assessment results of unmanned ships under complex navigation conditions constructed in this study are consistent with the expert identification results, proving the effectiveness and applicability of the proposed risk assessment method.

- (4)

- The research also has some limitations. One of the limitations lies in the lack of empirical data for autonomous ships, resulting in a little arbitrary assignment of membership degrees to certain factors, such as shore-based control personnel. Another limitation is that, due to the lack of international standards for the size and maneuverability of unmanned vessels, this study temporarily classifies them based on conventional manned vessels. In addition, the fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method used in this study has subjectivity on member degrees to some extent. This is due to the nature of fuzzy comprehensive evaluation itself.

4.2. Prospects

This study focuses on the research of highly autonomous unmanned ships. However, in the development process of unmanned ships, ships with other autonomy degrees will also exist in large numbers. In future studies, the navigation risk assessment of the autonomous ships with other degrees according to the ‘Degree of Autonomy’ defined by IMO under complex navigation conditions could be carried out.

For overcoming the problem of data lacking during the evaluation process, the digital twin technology or building simulated environments can be used to construct navigation scenarios in order to collect data. In addition, it is suggested that the subjectivity in the research can be reduced with the support of a large amount of data in a future study.

The most important step in risk assessment and analysis is to select risk impact indicators. Since unmanned ships are not mature at present, there are still many unknown factors that may affect the safe navigation of unmanned ships. Future research could adjust different risk impact factors in real time according to the development trend of unmanned ships and then improve the navigational risk assessment results of unmanned ships.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Z.; methodology, W.Z.; software, W.Z.; validation, W.Z.; formal analysis, W.Z.; investigation, W.Z.; resources, W.Z.; data curation, W.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, W.Z., Z.L. and X.M.; writing—review and editing, W.Z., Z.L. and X.M.; visualization, W.Z.; supervision, W.Z., Z.L. and X.M.; project administration, W.Z. and Z.L.; funding acquisition, W.Z. and Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, grant number 2024M750296, and the Dalian Science and Technology Talent Innovation Support Policy Implementation Plan (Young Science and Technology Star), grant number 2023RQ002.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, grant number 2024M750296, and the Dalian Science and Technology Talent Innovation Support Policy Implementation Plan (Young Science and Technology Star), grant number 2023RQ002, the Fundamental Research Project of Liaoning Provincial Department of Education, grant number JYTQN2023041, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant number 3132024133.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- China Classification Society. Rules for Intelligent Ships; China Classification Society: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Development Planning for a New Generation of Artificial Intelligence; State Council of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Gao, R. The Study on Formal Safey Accessment (FSA) of Containerships. Master’s Thesis, Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M. Safe Assessment of Containerships Based on ReliefF-ANFIS. Master’s Thesis, Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Fang, Q.; Xia, H.; Xi, Y. Formal safety assessment based on relative risks model in ship navigation. Reliab. Eng. Sys. Saf. 2007, 92, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. Study on Risk Security Evaluation Method of Ship Navigation. Master’s Thesis, Jimei University, Xiamen, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. The Ship Capsizing Risk Assessment based on BP Neural Network. Master’s Thesis, Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, T. Research on Risk Assessment of Ship Collision and Oil Spill Pollution Based on Stochastic Methodology: The Case Study of Taiwan Strait. Ph.D. Thesis, Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, D. The Study on Early-Warning Level of Navigation Safety Risk Under Complex Weather in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area. Master’s Thesis, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, X.B.; Meng, Q.; Li, S.Y. Ship collision risk assessment for the Singapore Strait. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2011, 43, 2030–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaman, M.B.; Kobayashi, E.; Wakabayashi, N.; Khanfir, S.; Pitana, T.; Maimun, A. Fuzzy FMEA model for risk evaluation of ship collisions in the Malacca Strait: Based on AIS data. J. Simul. 2014, 8, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, F. Identification, Assessment and Control of Navigational Risks in Coastal and Congested Waters. Navig. China 2014, 37, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Goerlandt, F.; Montewka, J.; Kuzmin, V.; Kujala, P. A risk-informed ship collision alert system: Framework and application. Saf. Sci. 2015, 77, 182–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, L.P.; Soares, C.G. Collision risk detection and quantification in ship navigation with integrated bridge systems. Ocean Eng. 2015, 109, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, R.; Shi, Z.; Shao, Z.; Liu, J. A novel regional collision risk assessment method considering aggregation density under multi-ship encounter situations. J. Navig. 2021, 75, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H. Collision Avoidance Decision Method for Unmanned Surface Vehicle Based on an Improved Velocity Obstacle Algorithm. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Kong, J.; Zhou, J. A novel regional ship collision risk assessment framework for multi-ship encounters in complex waters. Ocean Eng. 2024, 309, 118583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieme, C.A.; Utne, I.B.; Haugen, S. Assessing ship risk model applicability to Marine Autonomous Surface Ships. Ocean Eng. 2018, 165, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvonen, H.; Martio, J. Human Factors Issues in Maritime Autonomous Surface Ship Systems Development. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships, ICMASS 2018, Busan, Republic of Korea, 8–9 November 2018; SINTEF Academic Press: Trondheim, Norway, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sotiralis, P.; Ventikos, N.P.; Hamann, R.; Golyshev, P.; Teixeira, A.P. Incorporation of human factors into ship collision risk models focusing on human centred design aspects. Reliab. Eng. Sys. Saf. 2016, 156, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W. Research on Evaluation Method of Static Comfort of Automobile Seat Based on Fuzzy Neural Network. Master’s Thesis, Ningbo University, Ningbo, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- MUNIN. Research in Maritime Autonomous Systems Project Results and Technology Potentials. 2015. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/314286/reporting (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Niu, D.; Xu, C. Study on Thermal Power Plant Impact Post-Evaluation Based on AHP and Multi-Level Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation. East China Electr. Power 2010, 38, 1413–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J. Research on Computation Methods of AHP Weight Vector and Its Applications. Sci. Technol. Inf. 2015, 13, 218. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y. The Industrialization Risk Assessment Phosphate Building Gypsum Materials for Wall Based on Fuzzy Neural Network. Master’s Thesis, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, G.; Liu, H. Practical risk assessment based on multiple fuzzy comprehensive evaluations and entropy weighting. J. Tsinghua Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2012, 52, 1382–1387. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).