Abstract

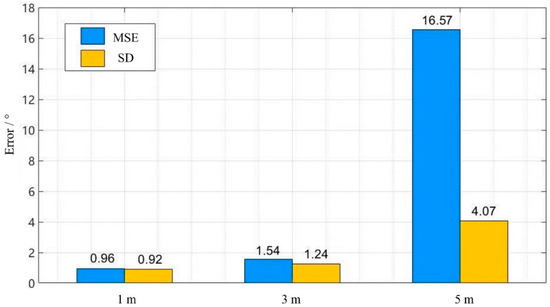

In response to the critical need for autonomous navigation capabilities of underwater vehicles independent of satellites, this paper studies a novel navigation and control method based on underwater polarization patterns. We propose an underwater course angle measurement algorithm and develop underwater polarization detection equipment. By establishing the automatic control model of an ROV (Remote Operated Vehicle) with polarization information, we develop a strapdown navigation method combining polarization and inertial information. We verify the feasibility of angle measurement based on polarization in the water tank. The measurement accuracy of polarization azimuth is less than 0.69°. Next, we conduct ROV navigation at different water depths in a real underwater environment. At a depth of 5 m, the MSE (Mean Square Error) and SD (Standard Deviation) of angle error are 16.57° and 4.07°, respectively. Underwater navigation accuracy of traveling 100 m is better than 5 m within a depth of 5 m. Key technologies such as underwater polarization detection, multi-source information fusion, and the ROV automatic control model with polarization have been broken through. This method can effectively improve ROV underwater work efficiency and accuracy.

1. Introduction

The underwater autonomous navigation system [1,2], which mainly includes radio navigation [3], geophysical navigation [4], and inertial navigation [5], is the key technology for a UUV (Underwater Unmanned Vehicle) to complete the autonomous underwater exploration mission. However, single navigation technology is not adequate for increasingly complex navigation tasks. Therefore, the core problem of underwater navigation is to reasonably equip the above navigation technology and effectively integrate the information provided by different navigation systems so as to obtain a navigation scheme with higher accuracy and stronger reliability than a single navigation system [6]. Underwater integrated navigation technology usually refers to navigation technology mainly based on an inertial navigation system and assisted by one or more technologies such as radio navigation, satellite navigation, and geophysical navigation. It aims to use high-precision navigation technology to correct the errors accumulated by inertial navigation equipment over time while ensuring the autonomy and disguise of UUVs. At present, in shallow water, a UUV mainly uses the combination of satellite and inertial navigation to estimate the status of the position, heading, and speed information. However, satellite navigation signals are susceptible to interference, which has become a technical bottleneck of underwater navigation.

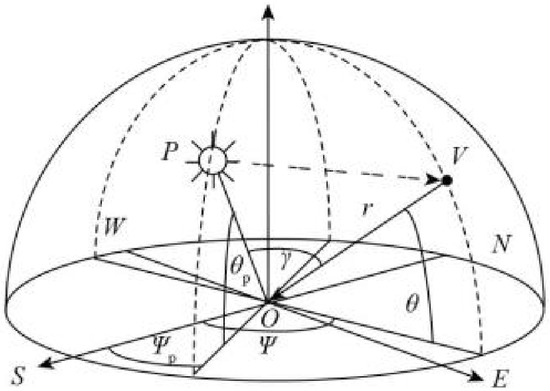

Many organisms on Earth have evolved over eons of evolution, and harsh natural selection has given them many superb navigational abilities [7,8]. Some organisms can rely on polarized information to determine their posture and position. A variety of insects, birds, and sea creatures have evolved the ability to sense polarized light and use it for navigation in the process of foraging, homing, and migration. Physicists have found that sunlight is scattered by the atmosphere and forms the skylight. Then, it is refracted by the gas–water interface, scattered by water particles, and finally forms a certain mode of polarization patterns underwater [9]. In most of the ocean depths that sunlight can penetrate through, the polarization pattern remains stable [10]. According to the theory of underwater polarized light transmission and the observation results of underwater polarization patterns, the space–time specificity of underwater polarization distribution mode exists objectively. Therefore, it is feasible to obtain navigation information by measuring underwater polarization patterns. The polarization patterns in Snell’s window in shallow water are similar to the atmosphere and contain important navigational information, which can be used by underwater organisms and even humans. Biologists have demonstrated that many underwater organisms [11,12,13] can sense the polarization information of the environment and thus perform navigational behaviors, which lays a biomimetic foundation for the navigation method proposed in this paper. Therefore, inspired by the biological navigation mechanism, it is theoretically feasible to realize underwater navigation technology based on the polarization pattern.

While the research on underwater polarization patterns is becoming more and more mature [14,15,16,17], the research on underwater polarization navigation technology is still in the primary stage. The realization of this navigation technology depends on the improvement of underwater polarization detection technology [18,19,20]. Some scholars have developed corresponding polarization detection equipment to detect the navigation information contained in the underwater polarization pattern, which proves the potential of underwater polarization navigation. Wehner [21] first discussed the feasibility of using polarized light for underwater navigation and proposed the idea of using polarized light to make navigation sensors. In different visual environments, polarization is used for different tasks, including contrast enhancement and defogging of images, camouflage recognition, optical communication, and navigation. Waterman [12] found that the polarization pattern in clear water at a depth of at least 200 m could be used for navigation, while the detection in deeper water required the improvement of optical sensor technology. The direction of the underwater E-vector is not always horizontal, which can be used for visual and navigational tasks. Lerner et al. [22] conducted theoretical modeling and experimental detection of underwater polarization patterns and found that it is possible to use underwater polarization navigation in clear water far from the seabed. Powell et al. [23] developed a polarization-sensitive imager by referring to the eye structure of mantis shrimp, which could capture underwater polarization patterns for navigation. The average geographical accuracy was 61 km and the error per 1 km traveled was 6 m, which verified the feasibility of using polarization for navigation underwater. Dupeyroux et al. [24] developed a polarization navigation sensor inspired by ants’ homing behavior and tested it in a water tank with a depth of 1 m. The mean error of angle measurement was 1.0° ± 4.0°, proving that the polarization distribution detected in clear shallow water can be used for navigation. Inspired by the polarization vision of underwater organisms, a bionic point source underwater polarization sensor was developed to obtain underwater polarization information [25]. Indoor and outdoor underwater experiments proved the angular measurement performance of the designed polarization sensor. In addition, a solar position determination algorithm based on the refraction polarization model in the underwater Snell’s window was proposed, and the effectiveness of the method was verified by underwater long-term experiments [26]. Therefore, by using navigation information contained in the underwater polarization pattern, the development of a novel underwater autonomous navigation system can further improve the operational efficiency and survivability of UUVs.

However, the underwater polarization navigation based on the UUV platform has not been realized. The intelligent navigation algorithm integrating underwater polarization information and other navigation information has not been proposed, and a variety of static and dynamic experiments of polarization navigation in the real underwater environment have not been carried out. Therefore, there is still a long way to achieve UUV underwater autonomous navigation based on polarization navigation technology. In this paper, we study polarization navigation technology and further realize UUV automatic control. In the Introduction, we discuss the characteristics of existing underwater navigation methods and introduce bionic polarization navigation technology. In view of the existing problems of this technology, we present the research work of this paper. Then, we show our navigation method and control principle in Section 2 and Section 3. In Section 4, we conduct a series of experiments and analyses. In the water tank experiment, we use a test device based on a north finder and precision turntable to test the angular accuracy of the polarization navigation system. We carry out an outdoor positioning accuracy experiment with an ROV (Remote Operated Vehicle) equipped with a navigation system combined with polarization and inertial navigation methods. The mean accuracy of course angle measurement in the water tank is 0.30°. The positioning accuracy of traveling 100 m is better than 5 m in the real underwater environment. Finally, we draw a conclusion in Section 5. The experiment achieves great results that prove that our navigation and control strategy is feasible. The bionic polarization navigation method proposed in this paper is inspired by underwater organisms sensing polarization for communication and navigation. Thus, we need to mimic marine life both in terms of hardware architecture and navigation algorithms. Due to the complex underwater conditions, the navigation accuracy of the current UUV is very low. At the same time, current polarization navigation can only work on land. Therefore, the proposed method is novel and effective because we promote the realization of high-precision polarization navigation technology underwater. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows. (1) Develop a strapdown navigation control method combining polarization and inertial information. (2) Develop underwater polarization information detection equipment by imitating the marine organism function of sensing polarization. (3) Conduct static and dynamic experiments of heading determination based on underwater polarization patterns. (4) Conduct the underwater tracking experiment at different depths based on polarization and inertial information. (5) Realize the bionic polarization navigation technology in a real underwater environment.

3. ROV Automatic Control

3.1. Attitude Updating

The rotation angular velocity of the carrier with respect to the navigation coordinate system can be obtained by the following equation:

ωx, ωy, and ωz are the angular velocity in each direction, respectively. is the rotation angular velocity of the carrier measured with respect to the inertial coordinate system. is the rotation angular velocity of the navigation coordinate system relative to the inertial coordinate system, which is shown below:

and are the east and north components of the carrier’s motion velocity relative to the navigation system, respectively. L and h are the latitude and height from the ground where the carrier is located, respectively. R0 is the radius of the earth. represents the rotation speed of the earth.

Define q = [q0 q1 q2 q3]T ∈ R4 as an attitude quaternion. The relation between the quaternion and the direction cosine matrix is:

The quaternion component obeys the following identity:

According to the quaternion differential equation, if the rotation angular velocity (ωx, ωy, ωz) of the carrier relative to the navigation coordinate system is known, then the attitude angle can be calculated by solving the differential Equation (7):

The relationship between the attitude angle of the carrier and the quaternion can be written as follows:

φ, δ, and ψ are the attitude angle in each direction, respectively. In the future, we will use the algebraic form of a quaternion [27], which is more compact and needs less computer power to improve our performance of the navigation algorithm.

3.2. Attitude Measurement

The roll angle and pitch angle of the carrier can also be calculated by the gravity component measured by the accelerometer. Given the values of gravity components gx, gy, and gz in the carrier coordinate system, roll angle and pitch angle can be calculated by the following equation:

3.3. System Model

The attitude quaternion solved by the gyroscopic integral in the MIMU (Miniature Inertial Measurement Unit) is selected as the state variable of the filtering system. The attitude angle measured by the accelerometer in the MIMU, and the polarization navigation method is selected as the measurement variable. The relationship in Equation (10) between attitude angle and attitude quaternion is taken as the measurement model of the system. Then, the state equation and measurement equation of Kalman filtering can be written as:

X = [q0 q1 q2 q3]T is the system state variable, Z = [φ δ ψ 1] is the measurement variable, and W(t) and V(t) are the process noise and measurement noise, respectively. The system transition matrix A can be expressed as:

The measurement matrix h(x) can be expressed as:

The last line in the above equation represents that the state variable satisfies the constraint that the quaternion norm is 1. The roll and pitch angle of variable Z can be determined by the gravity component of Equations (11) and (12), and the course angle can be determined by the output value of the polarized light sensor.

In order to facilitate real-time calculation, the Rungekutta algorithm is used to discretize the system state equation represented by Equations (13) and (14), and the following is obtained:

Let T represent a discrete period, and then Fk can be expressed as:

Since the measurement matrix H(Xk + 1) is nonlinear, the conventional Kalman filter algorithm cannot directly calculate. Therefore, an extended Kalman filter is used to estimate the attitude information. The measurement matrix performs a Taylor expansion near the state variable, and the higher order term is ignored to linearize the linear model Hk+1 of the measurement matrix:

3.4. Noise Variance Analysis

In the internal equation of the filter system, the process noise mainly comes from the rotation angular velocity of the carrier relative to the navigation coordinate system. As can be seen in Equation (4), when the carrier is moving at low speed and in short range, the rotation angular velocity of the navigation system is small relative to the inertial system, so its error can be ignored. The rotation angular velocity error of the carrier relative to the navigation coordinate system mainly comes from the measurement error of the gyroscope. Let the actual output of the gyroscope be represented by , and . , , and are the ideal value of the gyroscope. , , and are the measurement error of the respective gyroscope. After ignoring , Equation (17) can be written as:

The Taylor expansion in Equation (22) is performed near the ideal value of the gyroscope and the highest order small term is ignored:

Therefore, process noise in Equation (17) satisfies:

is the angular velocity error vector. is the antisymmetric matrix of attitude quaternion. Then, the process noise covariance matrix satisfies:

The characteristic of the measurement noise determines the variance of the measurement noise. In this paper, the roll angle and pitch angle are derived from Equations (11) and (12), and the course angle is derived from the calculation model of polarization navigation. Therefore, the following equation can be used to represent the covariance of measured noise:

represents the covariance of pitch and roll angle. represents the variance of the course angle. is the variance of the constant in Equation (9), and the theoretical value is zero. To avoid numerical problems, the covariance can be set to a smaller constant close to zero. Therefore, the covariance of the pitch and roll angle is:

It can be seen in the previous part that course angle ψ has a certain relationship with pitch and roll angle, so the variance of course angle is also related to them, which can be expressed by the following equation:

Here, b and c come from the course angle calculation equation and , , are the covariance of α, δ, φ, respectively.

In the outdoor underwater experiment, the polarization camera and the MIMU are installed on the carrier. The GPS receiver is used to obtain position information. According to the mathematical model of the strapdown inertial navigation system, the specific force and angular velocity information output by the MIMU are collected and compensated. The roll, pitch, course, speed, and position of the carrier are solved. The navigation error of the strapdown system can be estimated and compensated by the Kalman filtering method with the aid of external sensors, such as the polarization camera.

4. Experiment and Results

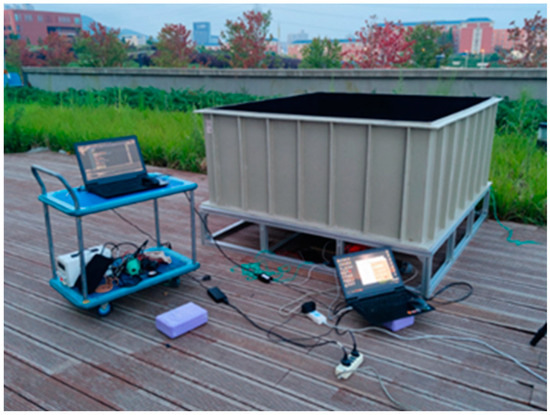

We first verified the course angle measurement of underwater polarization navigation (Figure 3). The polarization camera was set up on the high-precision turntable, which was installed on the mounting plate with the north finder. The mounting plate was leveled by the level. A 2 m × 2 m × 1 m water tank filled with water was placed directly above the camera. There was an open observation window under the water tank, which was directly facing the camera detection position. During the test, the north finder first determined the initial direction of the datum axis measured by the polarization camera. Then, the upper computer sent instructions to control the step rotation of the precision turntable and recorded the course angle measured by the polarization camera. After several rotations of the turntable, the data collected by the camera were counted and the course angle accuracy was taken as the 2σ error fluctuation interval.

Figure 3.

Course angle measurement in the water tank.

Table 1 is the results of angle measurement based on underwater polarization patterns when the solar meridian is at different angles. By comparing the measurement with the theory, we can obtain the mean error of the method, which is 0.30°. The measurement accuracy of the polarization azimuth is less than 0.69°. The results show that the underwater pattern of polarized light is closely related to the position of the sun, and the solar meridian is symmetrically distributed as the center line. The solar meridian can be used as the navigation reference line in the polarized light navigation method.

Table 1.

Static test results of angle measurement based on polarization.

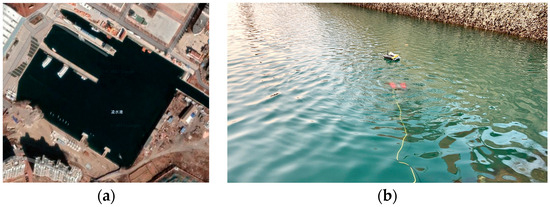

The accuracy of underwater polarization positioning was measured by the test platform of the ROV (Figure 4). The ROV, which was connected to the upper computer, was equipped with a navigation system with a polarization camera and a high-precision inertial navigation module. The navigation system was used to measure the ROV position information, and the upper computer was used to control the ROV and receive navigation information. The surface unmanned ship was equipped with a high-precision satellite navigation module, which can steer a fixed trajectory by remote control and record satellite navigation data. At the ground station, the front camera of the ROV test platform was used to control the ROV to track the surface ship on the water surface.

Figure 4.

ROV for underwater polarization positioning.

The experiment (Figure 5) was conducted at 4 p.m. with a solar altitude angle of 15.27° and a solar azimuth of 71.03°. The weather was sunny but the water quality was poor. There was a breeze, causing waves on the water. The test site is close to the shore, which will produce a negative impact on the experiment.

Figure 5.

The experiment of underwater polarization navigation. (a) Experimental site and (b) ROV test.

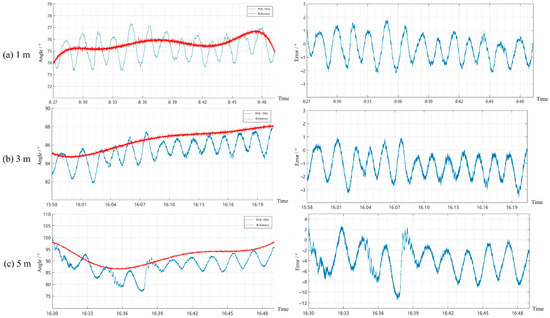

A variety of cruise routes and speeds were designed at different water depths. We then obtained the angle and position data measured by the polarization-based navigation system and further calculated related accuracy (Figure 6). With the depth, the error increases gradually. As a new bionic visual navigation method, it cannot exactly work at much deeper depths. But as photoelectric detection devices improve and underwater image enhancement technology develops, polarization navigation will be able to work in deeper waters and play a more important role.

Figure 6.

Angle error of underwater polarization navigation at 1 m (a), 3 m (b), and 5 m (c).

As shown in Figure 7, the underwater polarization/inertia system will provide a smooth heading output for the vehicle. The MSE (Mean Square Error) and SD (Standard Deviation) of the angle error are 16.57° and 4.07° at a depth of 5 m, respectively. However, due to the multiple scattering caused by water depth, the model parameters are changed, and constant error is introduced.

Figure 7.

The MSE and SD of angle error at different water depths.

Underwater navigation accuracy of traveling 100 m is better than 5 m within a depth of 5 m. The data using the fusion of polarized and inertial information have high robustness, good real-time performance, and no cumulative error accumulation. Outdoor experiments show that the polarization/inertial navigation system proposed by the paper had a high angle and positioning measurement accuracy.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, the structure and mechanism of navigation based on the sensing polarized light underwater and other information by marine organisms are proposed. The underwater bionic navigation method and ROV automatic control theory are studied. We develop the underwater bionic navigation system to meet the requirements of autonomous navigation capability of the underwater vehicle independent of the satellite. The mean accuracy of course angle measurement in the water tank is 0.30°. In the real underwater environment, the MSE and SD of the angle error are 16.57° and 4.07° at a depth of 5 m. Underwater positioning accuracy of traveling 100 m is better than 5 m within a depth of 5 m. This shows that underwater polarization navigation is feasible and has great potential in this depth range. As a novel navigation method that is not easy to be attacked and interfered with, bionic polarization navigation can realize independent navigation without relying on satellites and provide wide coverage and a robust, reliable, convenient, and useful navigation service for various unmanned platforms, which has broad application prospects. By studying UUV navigation and control technology based on underwater polarization patterns, the proposed method can improve and supplement existing underwater navigation technology and fill in the blank of underwater polarization navigation. At the same time, this method greatly expands the application range of polarization navigation and improves the practicability of this navigation method. In the future, we will work on the improvement of system accuracy and operational depth in a variety of underwater environments.

Author Contributions

Methodology, H.C.; Writing—review & editing, Q.C., X.Z., H.Y. and L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (62105136), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (202313033), and Qingdao Postdoctoral Program Grant (QDBSH20220202088).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ullah, I.; Chen, J.; Su, X.; Esposito, C.; Choi, C. Localization and detection of targets in underwater wireless sensor using distance and angle based algorithms. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 45693–45704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Ullah, I.; Liu, X.; Choi, D. A review of underwater localization techniques, algorithms, and challenges. J. Sens. 2020, 2020, 6403161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paull, L.; Saeedi, S.; Seto, M.; Li, H. AUV navigation and localization: A review. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2014, 39, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Tao, C.H.; Zhang, J.H.; Liu, C. Correction of tri-axial magnetometer interference caused by an autonomous underwater vehicle near-bottom platform. Ocean. Eng. 2018, 160, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutters, L.; Liu, H.; Tiltman, C.; Brown, D.J. Navigation technologies for autonomous underwater vehicles. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part C 2008, 38, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.A.; Farrell, J.A.; Zhao, Y.; Djapic, V. Autonomous underwater vehicle navigation. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2010, 35, 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskur, P. Side fins performance in biomimetic unmanned underwater vehicle. Energies 2022, 15, 5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naus, K.; Piskur, P. Applying the geodetic adjustment method for positioning in relation to the swarm leader of underwater vehicles based on course, speed, and distance measurements. Energies 2022, 15, 8472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbah, S.; Barta, A.; Gál, J.; Horváth, G.; Shashar, N. Experimental and theoretical study of skylight polarization transmitted through Snell’s window of a flat water surface. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2006, 23, 1978–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbah, S.; Shashar, N. Light polarization under water near sunrise. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2007, 24, 2049–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashar, N.; Hagan, R.; Boal, J.G.; Hanlon, R.T. Cuttlefish use polarization sensitivity in predation on silvery fish. Vis. Res. 2000, 40, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterman, T.H. Reviving a neglected celestial underwater polarization compass for aquatic animals. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2006, 81, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartron, L.; Josef, N.; Lerner, A.; Mccusker, S.D.; Darmaillacq, A.S.; Dickel, L.; Shashar, N. Polarization vision can improve object detection in turbid waters by cuttlefish. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2013, 447, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Wang, J.; Xu, W.; Zhang, K.; Ma, Z. Polarization patterns of transmitted celestial light under wavy water surfaces. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Chu, J.; Zhang, R.; Tian, L.; Gui, X. Underwater polarization patterns considering single Rayleigh scattering of water molecules. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2020, 41, 4947–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Chu, J.; Zhang, R.; Tian, L.; Gui, X. Turbid underwater polarization patterns considering multiple Mie scattering of suspended particles. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2020, 86, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Chu, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, P. Simulation and measurement of the effect of various factors on underwater polarization patterns. Optik 2021, 237, 166637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Chu, J.; Zhang, R.; Gui, X.; Tian, L. Real-time position and attitude estimation for homing and docking of an autonomous underwater vehicle based on bionic polarized optical guidance. J. Ocean. Univ. China 2020, 19, 1042–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Chu, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Gong, W. Polarization-based underwater image enhancement using the neural network of Mueller matrix images. J. Mod. Opt. 2022, 69, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, J.; Yu, H.; Chu, J. Underwater target detection utilizing polarization image fusion algorithm based on unsupervised learning and attention mechanism. Sensors 2023, 23, 5594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehner, R. Polarization vision—A uniform sensory capacity? J. Exp. Biol. 2001, 204, 2589–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, A.; Sabbah, S.; Erlick, C.; Shashar, N. Navigation by light polarization in clear and turbid waters. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. 2011, 366, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, S.B.; Garnett, R.; Marshall, J.; Rizk, C.; Gruev, V. Bioinspired polarization vision enables underwater geolocalization. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaao6841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupeyroux, J.; Viollet, S.; Serres, J.R. An ant-inspired celestial compass applied to autonomous outdoor robot navigation. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2019, 117, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yang, J.; Guo, L.; Hu, P.; Wang, C. A bionic point-source polarisation sensor applied to underwater orientation. J. Navig. 2021, 74, 1057–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Yang, J.; Guo, L.; Yu, X.; Li, W. Solar-tracking methodology based on refraction-polarization in Snell’s window for underwater navigation. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2022, 35, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitowski, Z.; Piskur, P.; Orłowski, M. Dual quaternions for the kinematic description of a fish–like propulsion system. Int. J. Appl. Math. Comput. Sci. 2023, 33, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).