Abstract

Collision risk identification is an important basis for intelligent ship navigation decision-making, which evaluates results that play a crucial role in the safe navigation of ships. However, the curvature, narrowness, and restricted water conditions of complex waterways bring uncertainty and ambiguity to the judgment of the danger of intelligent ship navigation situation, making it difficult to calculate such risk accurately and efficiently with a unified standard. This study proposes a new method for identifying ship navigation risks by combining the ship domain with AIS data to increase the prediction accuracy of collision risk identification for ship navigation in complex waterways. In this method, a ship domain model is constructed based on the ship density map drawn using AIS data. Then, the collision time with the target ship is calculated based on the collision hazard detection line and safety distance boundary, forming a method for dividing the danger level of the ship navigation situation. In addition, the effectiveness of this method was verified through simulation of ships navigation in complex waterways, and correct collision avoidance decisions can be made with the Regulations for Preventing Collisions in Inland Rivers of the People’s Republic of China, indicating the advantages of the proposed risk identification method in practical applications.

1. Introduction

With the development of waterway transportation, the increase in the number, tonnage, and speed of ships has raised the possibility of ship collision, especially in complex waterways [1,2]. Therefore, more scientific and efficient collision warning and collision avoidance decisions are needed in today’s water navigation scenarios. At present, ships have been widely installed with traffic sensing devices such as an automatic identification system (AIS) and a shipborne radar, and most complex or important waterways have been equipped with vessel traffic service (VTS), whose purpose is to obtain more navigation information to ensure the safe navigation of ships. However, ship collisions still exist and have not decreased with the advances in navigation technology [3]. This may be due to a combination of factors such as insufficient experience of ship navigators, sudden collision situations, and high thresholds for advanced equipment analysis [4]. The International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREG) is implemented by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), and some navigation regulations are implemented in some complex waterways, such as the Regulations for Preventing Collisions in Inland Rivers of the People’s Republic of China in the Yangtze River waterway. Nevertheless, these rules are qualitative and do not have quantitative collision prediction thresholds to assist in judgment in order to reduce the subjective judgment of navigators.

Several methods have been proposed to identify the risk of ship collision. In the mid-20th century, concepts such as Distance to Closest Point of Approach (DCPA), Time to Closest Point of Approach (TCPA), and Ship Domain were used to make decisions on ship collision avoidance [5,6]. Zheng and Wu [7,8,9] proposed the concepts of space collision risk and time collision risk, which considered the main factors that reflect risk levels of collision between ships, such as DCPA, TCPA, safety distance, and the latest avoidance point, to establish their respective collision avoidance risk models. Sotiralis et al. [10] proposed a quantitative risk analysis method based on Bayesian networks by considering human factors more adequately, which integrates elements from the Technique for Retrospective and Predictive Analysis of Cognitive Errors, focusing on analyzing human-induced collision accidents. Abebe et al. [3] proposed a ship collision risk index estimation model based on the Dempster–Shafer theory and its accuracy and fast calculation were verified by comparing it with different machine learning methods. Pietrzykowski et al. [11] proposed an integrated, comprehensive system of an Autonomous Surface Vessel dedicated to ships with various degrees of autonomy, and tests were conducted under the actual operating conditions of ships. Perera and Soares [12] proposed a collision risk detection and quantification methodology that can be implemented in a modem-integrated bridge system. Ozturk and Cicek [13] believe that the risk assessment of wind, current, and wave height on a ship’s dynamic cannot be ignored.

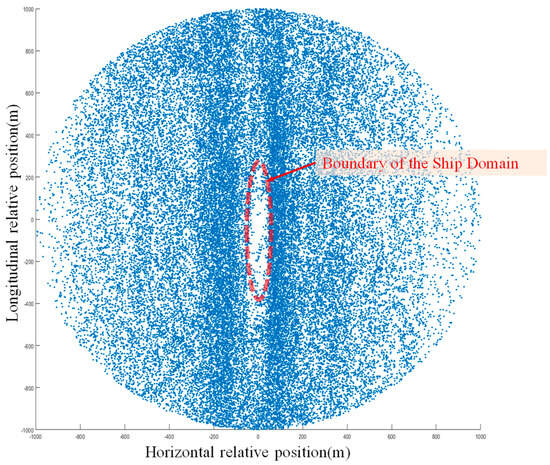

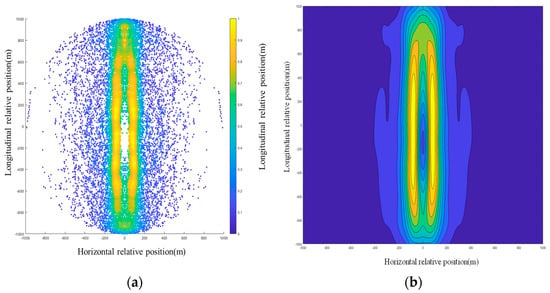

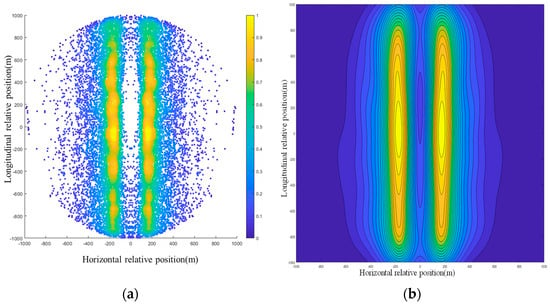

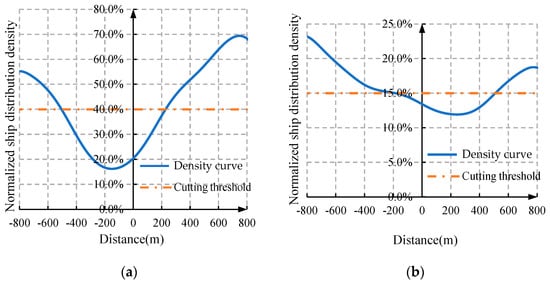

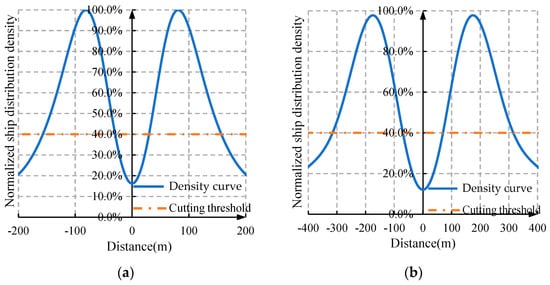

More advantageously, ship domain models can promote the rapid identification of ship navigation collision avoidance, and their boundaries determine the accuracy of ships’ collision avoidance. As early as 1963, a symmetric elliptical ship domain model centered around the own ship using the ship’s radar information was first proposed and widely applied [14]. Goodwin [5] divides the ship domain into three different-sized sectors based on ship lights. Van der Tak and Spaans [15] established a ship domain model based on previous research, in which the center of the elliptical ship domain has a forward offset from the position of the ship, and the bow of the ship was deflected, resulting in an area of approximately equal to the three-sector areas of the Goodwin model. Coldwell [16] established the ship domain model in overtaking and encountering situations by observing the traffic of over 200 ships in the 19 nautical mile waterways of the Humber River in the UK. Zhu et al. [17] proposed a multi-vessel collision risk assessment model based on the Coldwell ship domain model. Wen et al. [18] obtained the shape and size of specific types of ship domains in typical inland waterways by observing AIS-based grid density maps and analyzing grid density data, in which the ship domain in real life is quite different from the theoretical prediction. The shape of the ship domain in typical inland waters takes the form of an asymmetrically shaped ellipse, with its major axis coinciding with the ship’s central line.

With the widespread application of modern AIS technology, research on the ship domain based on AIS has become increasingly meaningful. Qi et al. [19] established a ship domain model and obtained boundary curves of the ship domain under different avoidance degrees by utilizing AIS data from Qiongzhou Strait. Hansen et al. [20] estimated the minimum ship domain where a navigator feels comfortable by observing the AIS data of ships sailing in southern Danish waters for four years. Szlapczynski and Szlapczynska [21] proposed a ship collision risk model based on the concept of ship domain and considered the related domain-based collision risk parameters, such as degree of domain violation, the relative speed of the two vessels, combination of the vessels’ courses, arena violations, and encounter complexity. Feng et al. [22] proposed a quantitatively evaluated method of the collision risks combining information entropy, which integrated the K-means clustering based on AIS data. Liu et al. [23] proposed a systematic method based on the dynamic ship domain model to detect possible collision scenarios and identify the distributions of collision risk hot spots in a given area. Du et al. [24] proposed a data ship domain concept and an analytical framework based on AIS, in which the ship domain explicitly incorporates the dynamic nature of the encounter process and the navigator’s evasive maneuvers. Liu et al. [25] proposed a quantitative method for the analysis of ship collision risk, in which a kinematics feature-based vessel conflict ranking operator was introduced, and both the static and dynamic information of AIS data were considered to evaluate ship collision risk. Silveira et al. [26] introduced a method to define AIS data-based empirical polygonal ship domains, which can fit the empirical domain better. He et al. [27] proposed a dynamic collision avoidance path planning algorithm for complex multi-ship encounters based on the A-star algorithm and the quaternion ship domain from AIS data. Zhang et al. [28] proposed an interpretable knowledge-based decision support method to guide ship collision avoidance decisions with a knowledge base based on the ordinary practice of seamen using AIS data.

In summary, on the one hand, these studies mainly focus on open water areas, and there is a lack of empirical research on ship navigation risks based on complex inland waterways. On the other hand, research methods based on statistical analysis use actual traffic flow data. Early research was mostly based on radar data, and in recent years, it has shifted towards AIS data. However, for research on risk identification with ship domains in complex waterways, qualitative research is often used, and data containing ship navigation information is rarely used for quantitative research. Thus, while taking the risk identification computations in complex waterways, a ship domain model considering the characteristics of navigation separation based on AIS data needs to be developed.

In this paper, a risk identification method is established based on the collision risk detection line and the safety distance boundary of the ship domain to provide real-time and fast guidance for collision avoidance control during navigation in complex waterways. Section 2 provides an overall description of the proposed risk identification method, Section 3 introduces the process of establishing a ship domain model, and Section 4 introduces collision risk classification algorithms based on the ship domain model. Section 5 validates this method using real ship data. In this way, we can evaluate the collision risk of ship navigation based on AIS data and assist ship navigation by providing a collision avoidance decision-making basis for navigators.

2. Procedure of the Proposed Risk Identification Method

The risk identification method for ship navigation in complex waterways consists of two procedures: establishment of ship domain and collision risk classification, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the proposed method.

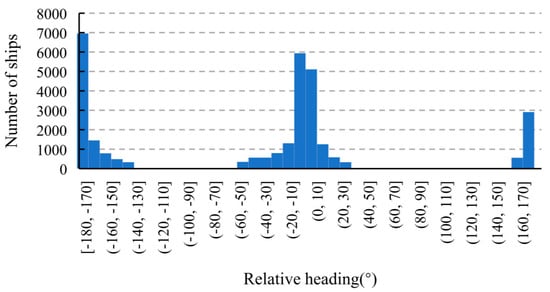

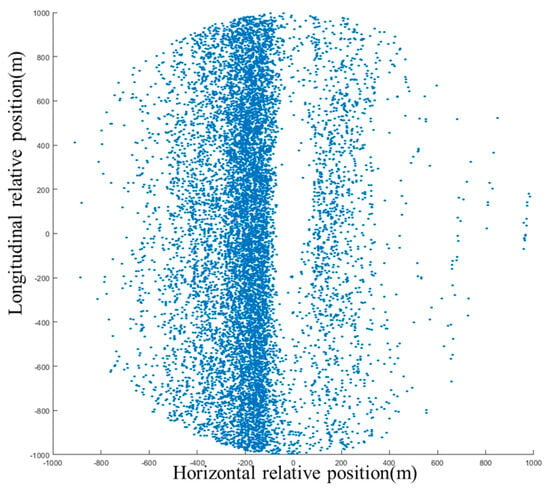

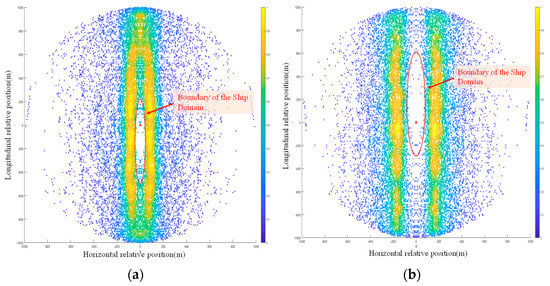

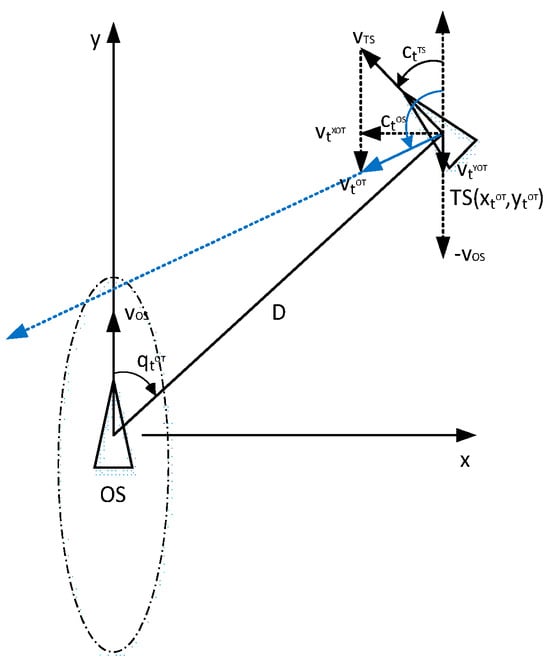

Due to the complex waterway characteristics and the Regulations for Preventing Collisions, the AIS position data distribution pattern of the target ships around the own ship in the same direction is not the same as that of the target ships in the opposite direction. Therefore, based on historical AIS data, a corresponding ship domain model for the own ship with different encounter situations is established in the complex waterway, which is described in detail in Section 3. When the position data (from AIS, radar, or a fusion of the two) of the own ship and the target ship are collected during real-time navigation, a mathematical equation using Formula (3) in Section 3.5 and Formula (11) in Section 4.1 can be applied for calculating the safety distance boundary in the ship domain. By determining whether the target ship is within the ship domain, whether the collision risk detection line intersects with the safe distance boundary of the own ship, and whether the time (Tca) to the intersection point between the collision risk detection line and the safe distance boundary of the ship domain is sufficient (Tca < TAlarm), the collision risk level is described and divided, forming a fast collision risk identification method for ship navigation in complex waterways.

5. Simulation Results and Discussion

5.1. Simulation

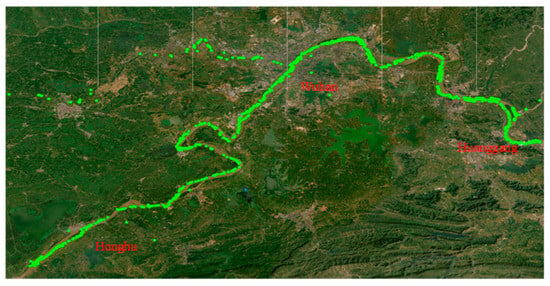

A complex waterway in the Wuhan reach of the Yangtze River was selected, as ships frequently encounter each other, which significantly increases the demand for collision avoidance warnings. According to the ship “Channel 1”, which has been introduced in Section 3.3, and its actual situation of collision avoidance with other ships in this complex waterway, the proposed risk identification method has been verified by mainly taking practical avoidance measures in the change of direction, when “Channel 1” and other ships are in a dangerous or urgent situation of encounter.

From 15:48 to 15:52 on 18 April, the ship “Channel 1” was sailing on the Luoyang reach between the Yangluo Yangtze River Highway Bridge and the Wuhan Qingshan Yangtze River Bridge, which has a width of about 350 m (the up lane width is about 150 m and the down lane width is about 200 m), and a depth of 8 m. Figure 14 shows the electronic chart of the Luoyang reach, in which facing the direction of water flow, the down lane is on the left side of the waterway, while the up lane is on the right side.

Figure 14.

Chart with AIS data of the Luoyang reach.

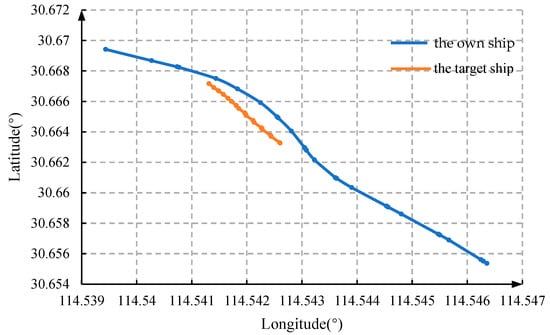

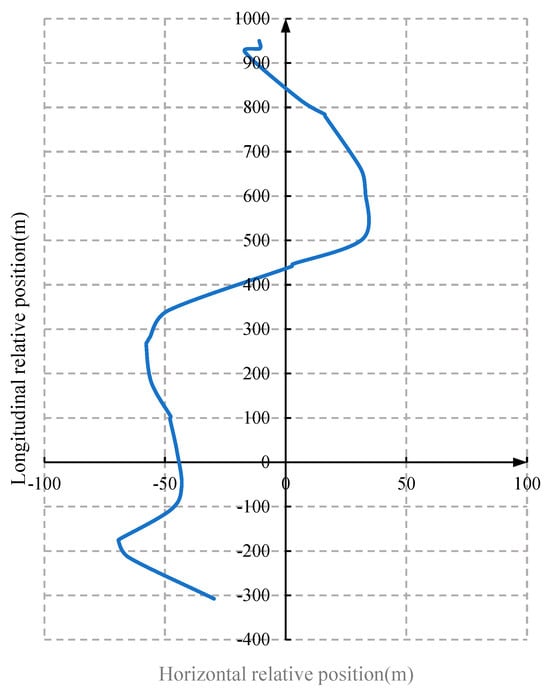

During this navigation, AIS data of the own ship “Channel 1” overtaking the target ship (MMSI: 413786692) was selected for analysis. In the beginning, the target ship was sailing at a speed of 3.4 knots, while the own ship followed at a speed of 13 knots. As the distance gradually narrowed to about 500 m, the own ship turned right and began to overtake the target ship. Then, the own ship was sailing parallel to the target ship, with a parallel distance of approximately 50 m. Finally, the own ship overtook the target ship and then turned left to return to the middle of the up lane of the waterway. The entire overtaking process is shown in Figure 15 and Figure 16.

Figure 15.

The trajectory map of the own ship and the target ship.

Figure 16.

The trajectory map of the target ship relative to the own ship.

5.2. Validation

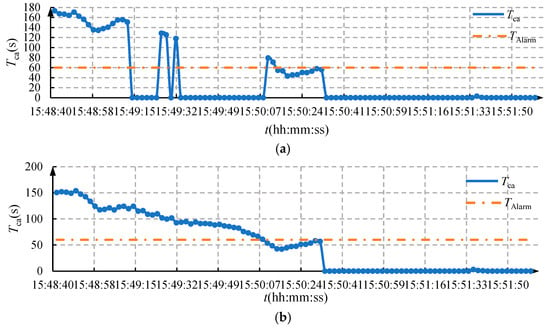

Figure 17 shows that Tca can effectively describe the collision risk level of the target ship relative to the own ship when the alert time TAlarm is 60 s. In addition, due to the low frequency of sending AIS data from the target ship and the low real-time performance of AIS data, which leads to missed alarms and poor alarm stability when using AIS data alone to calculate the collision risk level, compared to using the fusion data of AIS and radar. Compared with using the fusion data of AIS and radar, the lag time of only using AIS data calculation is about 5–10 s, which may affect the navigator’s misjudgment of the navigation risk situation.

Figure 17.

Change rate curve of the encounter time to the intersection point Tca. (a) Data from AIS; (b) Data from the fusion of AIS and radar.

The change rate of the own ship’s heading objectively reflects the behavior of the ship’s navigating operation. In other words, when the navigator discovers that there is a collision risk of the target ship, he will take corresponding avoidance actions, resulting in a change in the ship’s heading. Therefore, comparing the Tca change curve of the fused data with the change rate curve of the ship’s heading can prove whether the collision risk judgment result is consistent with the navigator’s risk judgment result, which can also verify the reliability of our risk identification method.

Figure 18 shows that at 15:50:00, our method began to alert collision risks from the target ship, and almost at the same time, the rate of the own ship’s heading change gradually increased, indicating that the navigator also judged that there was a risk of collision from the target ship and turned the rudder. Until 15:50:32, our method ends the collision risk alarm for the target ship, and the rate of the own ship’s heading change is gradually decreasing, indicating that at this time, the navigator also determines that the collision risk of the target ship is relieved, and turns the rudder in reverse to return to the original heading for navigation. Overall, our method’s collision risk alarm judgment is consistent with the navigator’s judgment, so our method is effective in identifying the collision risk during navigation and in line with the navigator’s cognitive habits.

Figure 18.

Relationship between Tca and heading change rate (the blue line is Tca, and the yellow line is the actual rate of change in heading).

Therefore, the risk identification method for ship navigation in complex waterways via consideration of ship domain can accurately reflect the collision risk of the target ship relative to the own ship, and the warning data is stable and has good real-time performance, which can effectively assist the navigator in identifying collision risks during navigation, in other words, our proposed method has been validated.

5.3. Comparison

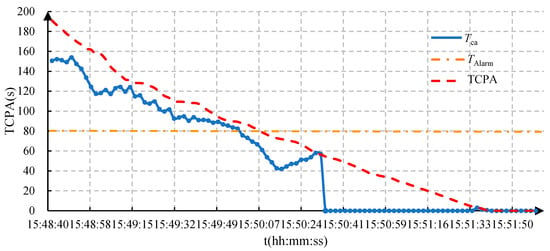

According to traditional methods, DCPA less than 200 m and TCPA less than 80 s are used as alarm judgment conditions, where DCPA is less than 100 m throughout the entire process, so only the changes in TCPA are considered [30].

Figure 19 shows that our proposed method is more accurate than the traditional DCPA and TCPA judgment methods for early warning. Firstly, the traditional DCPA and TCPA judgment methods lag by 8 s before starting to alarm. Secondly, after the navigation risk alarm, the traditional methods always maintain the alarm state for a long time and only stop the alarm after the ship has passed and cleared, which is inconsistent with the driver’s judgment of navigation risk and cannot accurately reflect the navigation situation.

Figure 19.

Comparison between our method and TCPA.

5.4. Discussion

In this paper, a new method for identifying ship navigation risks by combining the ship domain with AIS data is proposed, in which the collision time with the target ship is calculated based on the collision hazard detection line and safety distance boundary and formed a method for dividing the danger level of the ship navigation situation.

The research focuses on the Wuhan reach of the Yangtze River, where ships navigate by the Regulations for Preventing Collisions in Inland Rivers of the People’s Republic of China. In the complex waterway of the Yangtze River, the simulation results of our method are consistent with the actual navigation behavior and superior to the traditional TCPA method. This also indicates that our method can accurately reflect the consolidation risk of the target ship relative to the own ship, and the warning data is stable and has good real-time performance, which can effectively assist the navigator in identifying consolidation risks during navigation.

However, our method did not consider the hydrodynamic interaction between the ships. External hydrodynamic interference, such as waves and currents, is one of the important influencing factors for ship navigation decisions [31,32]. Our method has limitations by determining a reasonable size of the ship domain and avoiding the impact of hydrodynamic interference through navigators. Due to the lack of actual flow field data, poor ship informatization conditions, and the lack of equipment such as recorders and meteorological instruments, our research cannot consider external disturbances. In addition, hydrodynamic simulation requires a certain amount of computational power support, which may improve the accuracy of early warning but reduce the speed of early warning.

In the future, we will conduct research on rapid simulation and early warning methods that consider hydrodynamic interaction based on our proposed method. Our method will provide a decision-making basis for intelligent ships and assist in the construction of the future New Generation of Waterborne Transportation systems [33].

6. Conclusions

We have considered navigation conditions such as narrow waterways, as well as the characteristics of navigation rules for Yangtze River diversion navigation, and conducted research on methods for estimating the navigation collision risk of ships, and obtained the following conclusions:

- (1)

- In this paper, we combined the ship domain and ship position data from the fusion of AIS and radar to calculate the collision risk level of ship navigation and proposed a new convenient risk identification method for ship navigation in complex waterways.

- (2)

- According to the analysis of the distribution density map around the ship, it can be seen that when sailing in the same direction, the center of the ship domain moves backward, while sailing in the opposite direction, the center of the ship domain moves forward. The space on both sides of the ship is wider in the same direction than that in the opposite direction.

- (3)

- According to the safety distance boundary in the ship domain, the collision risk detection line, and the encounter time at the intersection point, the collision risk level of the ship navigation in complex waterways is divided into four levels: safe (Level I of collision risk), unsafe (Level II of collision risk), dangerous (Level III of collision risk), and very dangerous (Level IV of collision risk). In addition, data analysis was conducted on the real overtaking instance on “Channel 1”, verifying the effectiveness, stability, and real-time performance of our risk identification method.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W. and Y.W.; methodology, Z.W. and Y.W.; validation, Z.W., Y.W. and C.L.; formal analysis, Z.W. and Y.W.; investigation, Z.W. and Y.W.; resources, X.C. and M.Z.; data curation, Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.W.; writing—review and editing, C.L. and M.Z.; visualization, Z.W.; supervision, X.C.; project administration, Z.W. and Y.W.; funding acquisition, Z.W., Y.W., X.C., M.Z. and C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52172327, No. 52001243, No. 52001240); the Open Project Program of Science and Technology on Hydrodynamics Laboratory (No. 6142203210204); the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFB4301402); the Fujian Province Natural Science Foundation (No. 2020J01860); the Fujian Marine Economic Development Special Fund Project (No. FJHJF-L-2022-17); the Fujian Science and Technology Major Special Project (No. 2022NZ033023); the Fujian Science and Technology Innovation Key Project (No. 2022G02027, No. 2022G02009); and the Science and Technology Key Project of Fuzhou (No. 2022-ZD-021); and the Scientific Research Foundation for the Ph.D., Minjiang University (No. MJY19032). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhang, M.Y.; Montewka, J.; Manderbacka, T.; Kujala, P.; Hirdaris, S. A big data analytics method for the evaluation of ship-ship collision risk reflecting hydrometeorological conditions. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 213, 107674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.Y.; Conti, F.; Sourne, H.L.; Vassalos, D.; Kujala, P.; Lindroth, D.; Hirdaris, S. A method for the direct assessment of ship collision damage and flooding risk in real conditions. Ocean. Eng. 2021, 237, 109605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, M.; Noh, Y.; Seo, C.; Kim, D.; Lee, I. Developing a ship collision risk index estimation model based on Dempster-Shafer theory. Appl. Ocean. Res. 2021, 113, 102735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Meng, Q.; Qu, X. An overview of maritime waterway quantitative risk assessment models. Risk Anal. Int. J. 2012, 32, 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, E.M. A statistical study of ship domains. J. Navig. 1975, 28, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.V.; Dove, M.J.; Srockel, C.T. A computer simulation of marine traffic using domains and arenas. J. Navig. 1980, 33, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.L.; Zheng, Z.Y. Time collision risk and its model. J. Dalian Marit. Univ. 2001, 27, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.L.; Zheng, Z.Y. Space collision risk and its model. J. Dalian Marit. Univ. 2001, 27, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.Y.; Wu, Z.L. New model of collision risk between vessels. J. Dalian Marit. Univ. 2002, 28, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sotiralis, P.; Ventikos, N.P.; Hamann, R.; Golyshev, P.; Teixeira, A.P. Incorporation of human factors into ship collision risk models focusing on human centred design aspects. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2016, 156, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzykowski, Z.; Wołejsza, P.; Nozdrzykowski, Ł.; Borkowski, P.; Banaś, P.; Magaj, J.; Chomski, J.; Mąka, M.; Mielniczuk, S.; Pańka, A.; et al. The autonomous navigation system of a sea-going vessel. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 261, 112104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, L.P.; Soares, C.G. Collision risk detection and quantification in ship navigation with integrated bridge systems. Ocean. Eng. 2015, 109, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, U.; Cicek, K. Individual collision risk assessment in ship navigation: A systematic literature review. Ocean. Eng. 2019, 180, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Tanaka, K. Traffic capacity. J. Navig. 1971, 24, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Tak, C.; Spaans, J.A. A model for calculating a maritime risk criterion number. J. Navig. 1977, 30, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coldwell, T.G. Marine traffic behaviour in restricted waters. J. Navig. 1983, 36, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Shi, G.Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, J. Valuation model of ship collision risk based on ship domain. J. Dalian Marit. Univ. 2020, 41, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Y.Q.; Li, T.; Zheng, H.T.; Huang, L.; Zhou, C.H.; Xiao, C.S. Characteristics of ship domain in typical inland waters. Navig. China 2018, 41, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, L.; Zheng, Z.Y.; Li, G.P. AIS-data-based ship domain of ships in sight of one another. J. Navig. 2011, 37, 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, M.G.; Jensen, T.K.; Lehn-Schiøler, T.; Melchild, K.; Rasmussen, F.M.; Ennemark, F. Empirical ship domain based on AIS data. J. Navig. 2013, 66, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlapczynski, R.; Szlapczynska, J. A ship domain-based model of collision risk for near-miss detection and collision alert systems. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 214, 107766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.X.; Grifoll, M.; Yang, Z.Z.; Zheng, P.J. Collision risk assessment for ships’ routeing waters: An information entropy approach with Automatic Identification System (AIS) data. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2022, 224, 106184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.Z.; Yuan, Z.T.; Xin, X.R.; Zhang, J.F.; Wang, W.Q. Conflict detection method based on dynamic ship domain model for visualization of collision risk Hot-Spots. Ocean. Eng. 2021, 242, 110143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Banda, O.A.V.; Huang, Y.; Goerlandt, F.; Zhang, W. An empirical ship domain based on evasive maneuver and perceived collision risk. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 213, 107752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, B.Y.; Zhang, M.Y.; Wang, H.L.; Fu, X.J. A quantitative method for the analysis of ship collision risk using AIS data. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 272, 113906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, P.; Teixeira, A.P.; Soares, C.G. A method to extract the quaternion ship domain parameters from AIS data. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 257, 111568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Liu, C.; Chu, X.; Negenborn, R.R.; Wu, Q. Dynamic anti-collision A-star algorithm for multi-ship encounter situations. Appl. Ocean. Res. 2022, 118, 102995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.F.; Liu, J.J.; Hirdaris, S.; Zhang, M.Y.; Tian, W.L. An interpretable knowledge-based decision support method for ship collision avoidance using AIS data. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 230, 108919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Li, L.N.; Gao, J.J.; Li, G.D. Early warning of collision and avoidance assistance for river ferry. Navig. China 2020, 43, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.J.; Zhang, A.M.; Tian, W.L.; Zhang, J.; Hou, Z. Multi-ship collision avoidance decision-making based on collision risk index. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budak, G.; Beji, S. Controlled course-keeping simulations of a ship under external disturbances. Ocean. Eng. 2020, 218, 108126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkowski, P. Numerical Modeling of Wave Disturbances in the Process of Ship Movement Control. Algorithms 2018, 11, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.L.; Yan, X.P.; Liu, C.G.; Fan, A.L.; Ma, F. Developments and Applications of Green and Intelligent Inland Vessels in China. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).