Abstract

Against the backdrop of expanding off-farm employment, it is of great practical significance to examine how off-farm employment affects grain production and its underlying mechanisms, in order to build a more stable and sustainable national food security system. Drawing on micro-level data from wheat-producing households in the national Rural Fixed Observation Points survey from 2004 to 2021, this study systematically investigates the impact of off-farm employment on wheat planting decisions and the channels through which it operates. The findings reveal the following: (1) Off-farm employment encourages farmers to adjust their factor input structure and crop choices, leading to an increased proportion of wheat sown area. (2) Agricultural socialized services, especially mechanized operations, enhance the feasibility of factor substitution and effectively channel off-farm income into agricultural investment. Furthermore, the number of service providers at the village level plays a significant moderating role in this process; the more adequate the service supply, the stronger the positive effect of off-farm employment on wheat cultivation. (3) The influence of off-farm employment on wheat production is more pronounced in plain regions with favorable topographic conditions and among large-scale farming households. Based on these findings, the study recommends improving the agricultural service system, promoting better coordination between off-farm employment and agricultural development, and fostering a more stable and sustainable support system for grain production.

1. Introduction

In recent years, with the acceleration of industrialization and urbanization in China, a large number of rural laborers have continued to shift toward non-agricultural sectors, leading to a significant rise in the share of off-farm employment nationwide [1]. This trend has resulted in increasingly severe shortages and structural constraints in the agricultural labor supply. According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China, by 2023, the number of rural migrant workers reached 177 million, accounting for more than 60% of the total rural labor force; thus, income from off-farm employment has become the main source of livelihood for most rural households [2]. While this transformation has improved income levels and living standards, it has also raised a central question: in the context of large-scale labor migration, who will continue to farm? And more critically, will staple grain production be adversely affected? These concerns pose practical challenges to China’s agricultural modernization. The 2024 No. 1 Central Document explicitly addresses this issue by calling for resolute prevention of “non-grain use of arable land” and the stabilization of grain-sown areas. It also advocates for the establishment of benefit compensation mechanisms for major grain-producing areas, underscoring the dual imperatives of “who will farm” and “whether grain will be grown” [3].

China’s agricultural production system is simultaneously undergoing a profound transformation. On the one hand, the continuous advancement of agricultural mechanization, together with the rapid expansion of socialized service systems, has helped mitigate the adverse impacts of labor shortages on food production [4]. On the other hand, wheat—owing to its high compatibility with mechanized operations and relatively low labor input—has emerged as the staple grain crop that farmers are most inclined to retain when adjusting cropping structures and coping with production risks [5]. Against this backdrop of factor reallocation and evolving crop decision-making mechanisms, two key questions call for further investigation: First, to what extent has the rise in off-farm employment influenced farmers’ decisions regarding the cultivation of staple crops such as wheat? Second, does the agricultural service system serve a moderating or buffering role in this transition? These questions are not only central to understanding the micro-level foundations of China’s food security but are also closely aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goal 2 (“Zero Hunger”) and Goal 12 (“Responsible Consumption and Production”). Addressing these questions is essential for building a food production system that is more resilient, efficient, and sustainable.

Previous studies have shown that non-farm employment reduces the supply of agricultural labor and increases the risk of farmland abandonment, which in turn poses significant challenges to food production. In the context of China, rural labor migration has been found to significantly increase both the likelihood and extent of land abandonment [6,7]. Further evidence suggests that non-farm employment reduces agricultural labor input and diminishes technical efficiency [8,9]. Collectively, these studies highlight a “labor crowding-out effect,” whereby non-farm employment may constrain agricultural output when labor becomes a limiting factor.

By contrast, another line of research highlights the potential for non-farm employment to generate a “budget-relaxing effect” and promote “capital–labor substitution.” Non-farm income has been shown to enhance farm households’ cash flow and risk resilience, which in turn facilitates investment in mechanization and reduces dependence on manual labor. These shifts can help sustain agricultural output and labor productivity [10,11,12,13]. However, some studies suggest that non-farm employment may also lead to a decline in agricultural input intensity or weaken access to credit [14,15]. These mixed findings imply that both effects may coexist, and the net impact of non-farm employment on agricultural production depends on their relative strength.

Beyond labor and capital pathways, non-farm employment may also influence agricultural production indirectly through land reallocation and agricultural service systems. From the perspective of land use, existing studies generally find that non-farm employment significantly promotes the transfer of farmland and accelerates the concentration of land among more capable agricultural operators [16,17,18,19]. At the same time, agricultural socialized services are widely regarded as an important institutional mechanism for improving production efficiency and alleviating labor shortages. Related research has shown that service provision reduces agriculture’s dependence on household labor, encourages the adoption of more mechanized and specialized production practices, and helps optimize input structures and enhance farm-level performance [20,21].

Despite extensive research on the pathways through which non-farm employment affects agriculture—covering labor, capital and land—several important gaps remain. First, most existing studies focus on aggregate agricultural output or grain production, with limited attention to the heterogeneity among crops in terms of labor substitutability and compatibility with mechanization. As a result, internal adjustments within staple crop structures have not been adequately examined. Second, agricultural socialized services are often treated as independent explanatory factors, while their potential role as a moderating mechanism within the impact pathway of non-farm employment remains underexplored. Third, the relative income advantage of non-farm employment over staple crop production—an important determinant of farmers’ planting decisions—has not been systematically incorporated into the analytical framework.

Building on this context, this study investigates whether non-farm employment affects staple grain security in China and contributes to the literature in three key ways. First, it focuses on wheat—a staple crop characterized by high mechanization compatibility and low management intensity—to examine how non-farm employment influences grain production from the perspective of intra-grain structural adjustment. Second, it incorporates agricultural socialized services as a moderating factor. Specifically, a household is considered to have adopted such services if reported expenditures on outsourced mechanized operations or entrusted farming services are greater than zero. Based on this definition, an interaction term between non-farm employment and service adoption is constructed to identify the moderating role of socialized services in the impact pathway, highlighting how labor constraints may be mitigated through mechanization and outsourcing. In addition, the study investigates heterogeneity in farmers’ wheat planting adjustment behaviors across two dimensions—farm size and topographical conditions—focusing on structural adjustment paths such as expansion, reduction, or substitution with other crops. Third, using panel data from the National Rural Fixed Observation Points Survey (2004–2021) [22], the study systematically explores the long-term dynamics between non-farm employment and staple grain planting.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Direct Impact of Off-Farm Employment on Wheat Cultivation

In recent years, as a large number of rural laborers have shifted toward non-agricultural sectors, off-farm employment has become a key factor influencing adjustments in farmers’ crop planting structures. On one hand, the outflow of labor has intensified the shortage of agricultural labor, placing farmers under dual constraints of rising labor costs and declining labor availability. Under such conditions, farmers tend to reduce their investment in labor-intensive cash crops and shift toward staple crops like wheat, which require less labor input and are more compatible with mechanization, thereby ensuring basic food security [23,24]. Qian et al. and Yang et al. further point out that under the dual constraints of China’s land tenure system and food security policies, labor shortages have led rural households to retain wheat cultivation while reducing participation in other high-input, high-risk agricultural activities [8,25]. Similarly, De Brauw finds in a study of Vietnam that migrant households are more likely to withdraw from labor-intensive crop production and shift to land- and capital-intensive farming systems [24].

On the other hand, off-farm employment may also influence agricultural investment behavior through an income effect. With increased off-farm earnings, households enjoy greater disposable resources and are more capable of investing capital elements into agriculture, such as purchasing machinery or paying for land outsourcing services [26,27]. Yi et al. finds that households with off-farm employment experience spend significantly more on agricultural machinery than others, suggesting that off-farm income enhances farmers’ ability to allocate capital in agriculture [28].

In summary, off-farm employment may positively influence wheat cultivation through two channels: the labor substitution effect, where labor shortages drive farmers to shift toward less labor-intensive crops; and the income effect, where improved income enables greater capital investment in agriculture. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1.

Off-farm employment has a positive effect on the share of farmland allocated to wheat cultivation.

Hypothesis 1a.

Off-farm employment increases household income and capital investment, such as in agricultural machinery, thereby positively influencing the share of land used for wheat cultivation.

Hypothesis 1b.

Off-farm employment leads farmers to adjust their cropping structure by reducing investment in labor-intensive cash crops and shifting to less labor-demanding wheat, thereby increasing the share of wheat sown area.

2.2. The Moderating Role of Agricultural Socialized Services

Although off-farm employment may theoretically promote wheat cultivation through income growth and cropping structure adjustments, whether increased income is actually reinvested into agriculture remains contingent on several external conditions. Existing studies show that off-farm income is often directed toward non-agricultural uses, such as housing improvements, children’s education, or household businesses, rather than reinvested in agricultural production [29,30]. Therefore, income increases alone do not necessarily lead to higher agricultural investment, and the availability of agricultural services may play a key moderating role in this process.

Agricultural socialized services—organized systems providing technical support, mechanized operations, market access, and resource coordination—have become crucial mechanisms for improving production efficiency. In many developing economies, these services promote mechanization and information-based farming, thereby increasing labor productivity [4,31]. Prior studies have also found that such services significantly alleviate labor shortages and enhance agricultural efficiency, especially in major grain-producing regions and among large-scale operators [32,33]. However, other research reveals that in China’s major grain-producing areas, smallholders often face a “high willingness but low uptake” dilemma due to poor service accessibility and low supply–demand matching [34]. These findings suggest that the effectiveness of converting off-farm income into agricultural inputs depends on the development level of agricultural service systems. Based on this, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.

The extent to which off-farm income can be transformed into agricultural investment is conditioned by the development level of agricultural socialized services. A higher level of service development strengthens the positive impact of off-farm employment on wheat cultivation.

2.3. Heterogeneity in the Impact of Off-Farm Employment: Topography and Farm Size

The impact of off-farm employment on grain production is also characterized by significant heterogeneity, particularly in how farmers respond across different regions and topographical conditions. First, in terms of topography, Plains areas are more conducive to the adoption of agricultural mechanization. Farmers in these areas are better able to substitute labor with machines, making the negative effects of off-farm employment easier to mitigate. In contrast, hilly and mountainous regions face physical constraints on mechanized operations, which amplifies the constraining effect of off-farm employment on agricultural production [35]. Second, regarding farm size, larger-scale farmers typically have stronger mechanization capacity and greater ability to manage risks. They are more capable of leveraging socialized services and off-farm income to sustain grain production. Smallholders, however, are more likely to exit grain farming due to labor loss [34,36]. Based on these considerations, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 3a.

The impact of off-farm employment on wheat cultivation varies significantly across regions with different topographies. In plain areas, off-farm employment has a stronger positive effect on wheat production.

Hypothesis 3b.

The effect of off-farm employment on wheat cultivation differs across farm sizes. Among large-scale farmers, the positive influence of off-farm employment on wheat production is more pronounced.

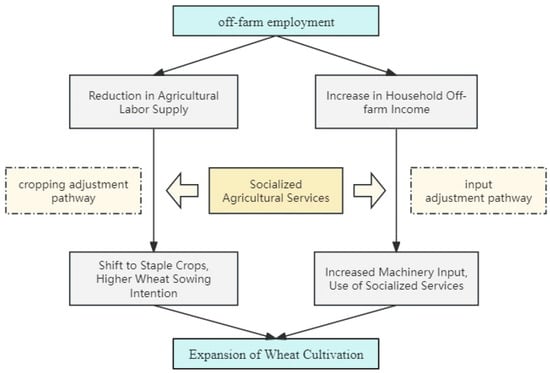

In summary, this study conceptualizes the impact of off-farm employment on wheat cultivation through two primary mechanisms. First, the labor substitution effect suggests that the outflow of rural labor encourages farmers to shift from labor-intensive crops to less labor-demanding staples like wheat. Second, the income–investment effect posits that increased off-farm income enhances farmers’ ability to invest in agricultural inputs, thereby supporting wheat production. Moreover, the development of agricultural socialized services plays a moderating role, facilitating the conversion of off-farm income into productive agricultural investments. These theoretical pathways are visually summarized in Figure 1, which serves as the analytical framework for the empirical investigation that follows.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Framework of the Impact of Off-Farm Employment on Wheat Cultivation.

3. Method

3.1. Model Specification

Farmers’ crop planting decisions are shaped by a combination of factors. In the study of agricultural supply behavior, it is widely acknowledged that price expectations are among the most critical determinants. Nerlove made a pioneering contribution by introducing a dynamic analytical framework into the study of agricultural supply and developing the adaptive expectations model. In this framework, farmers form expectations not solely based on the most recent price but by observing price trends over multiple past periods to anticipate future movements. The model specifies expected output as a function of anticipated prices and a set of exogenous variables. To meet the research objectives, this study extends the Nerlove framework by incorporating variables such as the level of off-farm employment, the lagged wheat sown area, and the prices of wheat and competing crops.

Traditional Nerlove models are primarily based on time-series data and are designed to capture the dynamic response of agricultural supply to price changes. However, this study employs multi-period panel data, which incorporates both temporal dynamics and cross-sectional heterogeneity across regions. In this context, directly applying a time-series model would make it difficult to control for unobservable but time-invariant regional characteristics—such as topography, policy legacy, social networks, and technology adoption capacity—potentially leading to biased model identification. Therefore, while retaining the core idea of decision inertia from the Nerlove framework, this study adopts a fixed-effects panel model for empirical analysis. On the one hand, the fixed-effects approach can effectively control for unobserved, time-invariant factors at the regional or household level, thus mitigating omitted variable bias. On the other hand, it allows for the inclusion of more time-varying control variables, which enhances the model’s identification strength and explanatory power. The model is specified as follows:

Let denote the share of wheat sown area for farmer i in period t; is the lagged value of the wheat sown area share; represents the lagged price of wheat received by the farmer; denotes the unit price of the competing crop cultivated by the farmer in the previous period, reflecting the opportunity cost of wheat cultivation; represents the explanatory variables; denotes the control variables.

To address potential non-stationarity in the data, all variables in the model are transformed into logarithmic form, resulting in a log-linear specification. This transformation not only mitigates issues of heteroskedasticity but also facilitates the interpretation of elasticities between variables. Additionally, given the possibility of heteroskedasticity and intra-group correlation in micro-level panel data, clustered robust standard errors at the village level are employed in all regressions to enhance the robustness of parameter estimates. As for the normality of the error terms, the large sample size and the use of robust estimation techniques help minimize any adverse effects on the results.

3.2. Variable Selection

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

The dependent variable is the share of wheat sown area (WAS), defined as the ratio of a household’s wheat planting area to its total contracted farmland. Compared with the absolute wheat area, this measure more accurately reflects farmers’ crop structure choices and planting preferences under limited land resources, as it eliminates the bias caused by differences in landholding size. To ensure validity, the sample includes only households that cultivated wheat at least once during the study period, thereby avoiding meaningless values of the dependent variable. It should be noted that changes in WAS may result either from an expansion of wheat planting area or from a reduction in total contracted farmland. To verify this, we conducted a statistical analysis of households with an increase in WAS and found that approximately 78.66% of the increase was driven by an expansion of wheat planting area, while only about 21.34% was due to a reduction in contracted farmland. Therefore, using WAS as an indicator more accurately reflects farmers’ actual planting behavior rather than mere proportion changes caused by land size fluctuations.

3.2.2. Independent Variable

Share of off-farm employment time (OES). Given that more than 50 percent of the sampled household heads are above 50 years old and nearly 20 percent are above 65, this study measures the indicator as the ratio of total household off-farm working hours to total household labor hours. A value of 1 indicates that all household members are engaged in off-farm activities, while a value of 0 indicates that the household is fully engaged in farming.

OES × socialized service adoption (OES × SSA). Against the backdrop of continued labor outmigration, a household’s ability to maintain agricultural production and replace family labor largely depends on its access to agricultural socialized services and mechanized operations. Existing studies show that the development of agricultural socialized services significantly improves mechanization levels and production efficiency, thereby mitigating the labor constraints caused by off-farm employment. This effect is especially evident in labor-intensive staple crops such as wheat, where the use of these services supports households in maintaining production even under labor shortages [35]. Therefore, this study sets an interaction term “OES × socialized service adoption” to identify the moderating effect of socialized services.

To construct the socialized service variable, this study draws on household expenditure data. Specifically, if the combined expenditures on outsourced mechanized operations and entrusted or substitute tillage services exceed zero, the household is classified as having adopted socialized services (value = 1); otherwise, the value is 0. In the rural fixed-point survey, outsourced machinery expenditures are recorded as aggregate amounts, including both equipment usage fees and payments to operators. This study treats the entire amount as mechanized operation expenditure because the core objective of purchasing such services is labor substitution through mechanization—regardless of whether labor wages are included, the expense reflects the household’s mechanization level. These expenses are fully borne by farm households and do not include any government subsidies.

OES × comparative advantage of off-farm employment (OES × CAOE). In practice, whether off-farm employment influences farmers’ agricultural decisions depends not only on the duration of their off-farm work but also on whether it is economically worthwhile. That is, only when off-farm income significantly exceeds farming income do farmers have the incentive to reallocate household labor and adjust their cropping structure, favoring crops that are less labor-intensive and more mechanized.

Sample statistics show that before 2012, the average daily income from off-farm employment was generally lower than that from cash crops such as rice and vegetables, leading farmers to continue planting these high-input, high-return crops. However, after 2012, off-farm daily earnings gradually surpassed those of these crops, and off-farm employment began to show a clear comparative advantage, increasing the likelihood that labor would shift toward staple crops such as wheat. This suggests that the impact of off-farm employment on wheat planting is characterized by distinct phases and threshold effects.

Accordingly, this study introduces the interaction term “OES × comparative advantage of off-farm employment” to identify whether the expansion of off-farm work time is accompanied by a relative economic advantage. Specifically, the study calculates the average daily income from rice and vegetables and compares it to the household’s off-farm daily income. If the latter is higher, the household is considered to have a comparative advantage in off-farm employment and is assigned a value of 1; otherwise, it is assigned a value of 0.

3.2.3. Control Variables

Wheat Price: Since farmers usually form price expectations based on previous information, the lagged wheat price is used as the expected price variable. As wheat has a relatively long production cycle, price changes tend to influence the next sowing season. An increase in the previous period’s wheat price typically leads farmers, in pursuit of short-term profits, to expand wheat cultivation, thereby raising supply in the following season.

Competing Crop Prices: In addition to wheat prices, farmers also consider the market prices of alternative crops, especially those in direct competition with wheat. If the price of a competing crop rises, farmers may reallocate land to maximize returns and reduce wheat cultivation. Based on the cropping structure of different wheat-growing regions in China, rice and vegetable prices are selected as the main competing crops.

Wheat Production Cost: From an input–output perspective, wheat production costs have risen steadily in recent years, particularly for labor, land, fertilizer, and machinery. Rising costs compress profit margins and weaken farmers’ incentives to grow wheat. Therefore, the total cost of wheat production is included as a key control variable. Total cost covers expenses for seeds and seedlings, imputed value of organic fertilizer, chemical fertilizer, plastic film, pesticides, irrigation, outsourced mechanized services, land rent, and other indirect expenses. This variable is log-transformed in the empirical analysis.

Policy Factor: Government intervention remains central to safeguarding food security. This study includes the Minimum Support Price (MSP) for wheat as a policy variable. The MSP applies to six provinces—Hebei, Jiangsu, Anhui, Shandong, Henan, and Hubei—and sets a price floor to stabilize farmers’ income expectations. Adjustments to the MSP over time (see Table A1) have directly influenced farmers’ planting decisions. This variable is therefore incorporated into the empirical model as a key policy factor.

In addition, this study controls for household- and village-level characteristics to account for potential confounding effects on wheat sown area. At the household level, control variables include age, gender (male = 1, female = 0), Party membership (Communist Party member = 1, otherwise = 0), participation in agricultural training (yes = 1, no = 0), health status, and household labor size. Health status is coded from 1 to 5 according to five categories: excellent, good, fair, poor, and loss of work capacity. Household labor size refers to the total number of working-age individuals (16–65 years old) in the household. At the village level, control variables include the level of economic development and whether the village is water-scarce. Economic development level is categorized into five groups—upper, upper-middle, middle, lower-middle, and lower—and coded from 1 to 5. “Water-scarce village” is a dummy variable coded as 1 if the village faces water scarcity and 0 otherwise. Detailed descriptive statistics are presented in Table A2.

3.3. Data Source and Descriptive Statistics

The micro-level data used in this study are drawn from the National Rural Fixed Observation Point Survey. This survey is a longitudinal household-level tracking database administered by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. To ensure data consistency and relevance to the research objectives, the study utilizes household data from the years 2004 to 2021. The dataset covers 31 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities across mainland China (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan), including approximately 23,000 rural households and 360 administrative villages. To ensure the validity of the dependent variable, the sample is restricted to households that planted wheat at least once during the study period. Households that never engaged in wheat cultivation are excluded from the analysis. All price-related variables are deflated using the annual Consumer Price Index (CPI) for rural residents to account for inflation effects. Summary statistics for the main variables are presented in Table 1. Descriptive statistics for household and village-level characteristics are provided in Appendix A Table A2.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Main Variables.

3.4. Unit Root Test

To avoid spurious regression caused by non-stationary variables, panel unit root tests were conducted for all core variables prior to the regression analysis. Two methods were applied—the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test and the Im–Pesaran–Shin (IPS) test—to examine whether the variables are stationary in their level form. As shown in Table 2, most variables passed the stationarity test at their original levels; however, “share of off-farm employment time,” “vegetable price,” and “wheat production cost” were found to be non-stationary. Accordingly, these three variables were transformed by taking the first difference, after which they became stationary and thus met the requirements for econometric analysis. In the subsequent empirical analysis, these variables are included in the regression models in their first-differenced form.

Table 2.

Unit Root Test Results 1.

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Model

According to the theoretical background discussed earlier, off-farm employment is expected to exert a positive effect on the share of wheat sown area (WAS). Table 3 reports the estimation results of the regression models, with Model 1 serving as the baseline specification. In this model, only the core explanatory variable—the share of off-farm employment time (△OES)—is included. The estimated coefficient is 0.0216, which is positive and statistically significant at the 10% level, indicating that off-farm employment has a modest but positive effect on the expansion of wheat planting area, although the overall impact remains relatively limited.

Table 3.

The Impact of Off-Farm Employment on Farmers’ Wheat Planting Decisions 1.

Models 2 and 3, respectively, introduce two interaction terms on top of the baseline: “△OES × SSA” and “△OES × CAOE” Both interaction terms yield significantly positive coefficients (0.0561 and 0.0625, respectively), with the latter significant at the 1% level. These results suggest that the effect of off-farm employment on wheat cultivation is primarily transmitted through specific mechanisms rather than through a direct pathway. In particular, the availability of socialized services provides farmers with practical labor substitution options, enhancing the compatibility between off-farm employment and grain production. Meanwhile, the relative income advantage of off-farm work serves as an economic incentive for farmers to adjust their cropping structure in response to labor constraints.

In Model 4, both interaction terms are included simultaneously along with a set of control variables. The coefficient for off-farm employment time share becomes statistically insignificant, reinforcing the argument that its impact on wheat cultivation operates mainly through indirect channels. This finding implies that once moderating mechanisms and household-level heterogeneity are accounted for, the marginal effect of off-farm employment itself becomes attenuated.

To further elucidate these mechanisms, descriptive statistics on household labor structure are examined. The results show that the average age of agricultural laborers in households with off-farm employment is 53.27 years, significantly higher than 48.61 years in households without off-farm employment. This indicates a pattern of “labor force restructuring,” whereby agricultural tasks are increasingly undertaken by older household members after the main laborers have exited for off-farm work. This structural shift helps maintain the existing crop production system and also explains why the coefficient of off-farm employment becomes insignificant when mechanisms are fully controlled for—its influence is primarily indirect, contingent on institutional support and internal labor reallocation.

Notably, the two interaction terms remain significantly positive in Model 4, further confirming that off-farm employment affects wheat cultivation through both “labor substitution” and “income incentive” mechanisms. On the one hand, agricultural socialized services—such as mechanized field operations and land trusteeship—help fill the labor gap created by out-migration, providing institutional support for the continuation of grain production. On the other hand, whether off-farm employment stimulates wheat cultivation depends on its income advantage over competing economic crops. When off-farm earnings are relatively more attractive, farmers are more inclined to reallocate household labor toward off-farm sectors while retaining wheat—a labor-saving, highly mechanized crop—as a means of optimizing labor use and adjusting cropping structure.

4.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

Topographic conditions also affect the feasibility of labor substitution through mechanization. In plain areas, the flat terrain and contiguous farmland make large-scale mechanized operations more feasible and efficient. In such areas, labor shortages resulting from off-farm employment can be more readily offset by mechanization. This may not only mitigate the negative impact on wheat cultivation but even contribute to an expansion of the wheat sown area. In contrast, non-plain areas are characterized by complex terrain and fragmented plots, making them unsuitable for large-scale mechanized operations. In these areas, machinery is less able to substitute for labor, and agricultural production remains more labor-intensive. Therefore, in non-plain regions, the reduction in labor due to off-farm employment may have a more pronounced negative effect on wheat cultivation.

As shown in Table 4, in non-plain areas, the share of off-farm employment time is 63%, which is 10 percentage points lower than that in plain areas. The share of wheat sown area is 45%, 26 percentage points lower than in plain areas. This suggests that the positive association between off-farm employment and wheat cultivation is likely to be weaker—or even negative—in non-plain regions. Additionally, the share of mechanization costs is lower than in plain areas, while labor input per mu of wheat is nearly twice as high. These patterns indicate that, due to topographic constraints and lower mechanization feasibility, agricultural production in non-plain regions is less able to substitute labor with machinery. As a result, the negative effect of off-farm employment on wheat sown area may be more pronounced in such regions.

Table 4.

Variation in the Share of Wheat Sown Area by Topographic Conditions and Farm Size.

Following the analysis of how topographic conditions influence the mechanism through which off-farm employment affects wheat cultivation, it is necessary to examine another key source of heterogeneity: farm size. While differences in terrain primarily affect farmers’ ability to adopt mechanization and outsourcing services, farm size is directly linked to farmers’ resource endowments and production strategies. To better capture the heterogeneity among farm households in the relationship between off-farm employment and wheat cultivation, this study further explores behavioral differences between large-scale and small-scale farmers. Descriptive statistics reveal that 67.88% of households cultivate less than 5 mu of wheat, 26.17% cultivate between 5 and 15 mu, 1.66% cultivate between 15 and 30 mu, and only 0.33% cultivate more than 30 mu. Overall, the distribution of farm size is skewed toward smallholders. Accordingly, this study defines large-scale farmers as those cultivating more than 15 mu of wheat.

Descriptive statistics in Table 4 reveal notable differences between small- and large-scale farmers regarding off-farm employment and wheat cultivation characteristics. Among small-scale farmers, 68% of household labor is engaged in off-farm work, compared to 60% among large-scale farmers. This may be attributed to the limited scale efficiency of small-scale operations, which constrains their ability to generate substantial income from wheat cultivation. A further comparison indicates that the share of wheat sown area among small-scale farmers is 51%, markedly lower than the 79% observed among large-scale farmers. This suggests that large-scale farmers are more likely to engage in specialized grain production.

To more clearly identify the heterogeneous effects of off-farm employment on wheat cultivation, this study conducts subgroup regressions based on two dimensions: topographic type (plain vs. non-plain areas) and farm size (small-scale vs. large-scale farmers). Compared with including multiple interaction terms in a single regression equation, the subgroup estimation approach offers two main advantages. First, it allows for a more intuitive comparison of coefficient differences across groups, which facilitates the identification of group-specific policy implications. Second, it helps mitigate potential multicollinearity issues that may arise from the inclusion of excessive interaction terms, thereby enhancing the robustness and interpretability of the regression results. Based on these considerations, this study adopts a subgroup estimation strategy while keeping the set of control variables consistent across all groups.

Table 5 reports the empirical results of the heterogeneity analysis. The effect of △OES on WAS is stronger in plain areas than in non-plain areas. Specifically, the coefficient of △OES in plain areas is 0.03 and significant at the 1% level. This suggests that off-farm employment promotes wheat cultivation more effectively in these regions through the mechanism of capital–labor substitution. This interaction term is significant only in plain regions (coefficient = 0.102, p < 0.01), highlighting the regional variation in the moderating role of socialized services. This provides additional evidence that socialized services more effectively enhance the positive effect of off-farm employment on grain production in regions with favorable topographic conditions.

Table 5.

Heterogeneity Analysis of the Effect of Off-Farm Employment on Wheat Cultivation 1.

When disaggregating by farm size, off-farm employment has a significantly positive effect on wheat sown area (WAS) for both small- and large-scale farmers. Among small-scale farmers, the estimated coefficient for △OES is 0.090, significant at the 10% level. In comparison, the coefficient among large-scale farmers is 0.113 and statistically significant at the 5% level, suggesting a relatively stronger association between off-farm employment and wheat cultivation decisions in this group. The interaction term between off-farm employment and socialized services is significant at the 1% level for both groups, with a coefficient of 0.025 for small-scale farmers and 0.110 for large-scale farmers. This provides evidence that the moderating effect of socialized services on the relationship between off-farm employment and wheat cultivation is more pronounced among large-scale farmers, who may have greater capacity and incentive to adopt such services at scale.

This difference suggests that large-scale farmers have greater organizational capacity and resource management skills, allowing them to more effectively reinvest off-farm income into agricultural operations. They are more likely to adopt labor-saving socialized services, thereby sustaining or even scaling up their wheat production. In contrast, although small-scale farmers have a higher proportion of off-farm labor, their operations are less specialized, and the influence of socialized services on their planting decisions is relatively limited.

4.3. Endogeneity Test

To address potential endogeneity and validate the estimated effect of off-farm employment on the share of wheat sown area, this study conducts robustness checks using two approaches: the fixed effects instrumental variable (FE-IV) model and the system generalized method of moments (System GMM). Endogeneity may result from omitted variables or reverse causality. To mitigate this, the study uses migration social networks (MSN)—proxied by the average number of migrant workers in the village over the past five years—as an instrumental variable. It influences off-farm employment decisions via social demonstration and information-sharing, but is plausibly exogenous to crop structure choices, thus satisfying the relevance and exclusion conditions. Second, to account for the dynamic nature of wheat planting decisions, the study applies a System GMM estimator. This method addresses both endogeneity and lag dependence by using lagged explanatory variables as instruments. Specifically, the second lag of wheat sown area is used to strengthen identification.

Table 6 presents the estimation results. The instrument passes the under-identification, weak instrument, and endogeneity tests, confirming its validity. The System GMM estimates also pass autocorrelation and overidentification tests, supporting model specification. The results are consistent with the baseline estimates and confirm the robustness of the findings.

Table 6.

Endogeneity Tests for the Impact of Off-Farm Employment on Wheat Sown Area Share 1.

4.4. Robustness Check

To verify the robustness of the regression results, this study conducts checks from three perspectives: sample selection, variable replacement, and interaction expansion. First, households with year-on-year changes in total cultivated area exceeding 20% were excluded to eliminate the influence of drastic land adjustments. The re-estimated results remain consistent with the baseline findings. Second, the core variable was replaced with the share of off-farm income (OEI) instead of time, and the results show similar direction and significance, confirming robustness to alternative definitions. Third, based on the heterogeneity analysis, interaction terms between off-farm employment and both topography and farm size were introduced. The effects were more pronounced among smallholders and in plain areas, suggesting that natural and resource conditions strengthen the underlying mechanisms. Overall, these multi-dimensional robustness checks enhance the credibility and generalizability of the findings (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Robustness Check Results 1.

4.5. Further Analysis

The previous analysis has identified that the use of agricultural socialized services at the household level moderates the relationship between off-farm employment and wheat cultivation. However, the availability of such services is not solely determined by individual decisions but also depends on village-level resource endowment and service conditions. Therefore, it is necessary to further examine whether the village-level supply of socialized services amplifies or weakens the effect of off-farm employment on wheat production behavior. Unlike the previous focus on individual-level service adoption, this section shifts attention to the external institutional and service environment influencing farmers’ production decisions.

This section uses the number of agricultural service providers in the village as a proxy variable to measure the village-level supply of socialized services. This indicator encompasses various types of service providers, including agricultural input supply, plant protection, entrusted farming, mechanized operations, and agricultural product sales, offering a comprehensive reflection of the village’s agricultural service capacity.

Given that wheat is a highly mechanized crop, its entire production process—including sowing, management, and harvesting—relies heavily on stage-specific mechanized services such as plowing, sowing, and harvesting. Compared with input supply or sales services, mechanized operations have a more direct influence on farmers’ planting decisions. This is particularly true under conditions of rural labor shortages, where the availability of such services plays a critical role in farmers’ decisions to continue wheat cultivation.

Therefore, we further introduce a more targeted indicator: the level of mechanized agricultural services, defined as the number of service providers offering basic mechanized operations such as plowing, sowing (or transplanting), and harvesting. This variable is a subset of the total number of agricultural service providers in the village and specifically focuses on labor-saving services that substitute capital for manual labor. It helps identify the potential mechanism through which off-farm employment influences wheat production by enabling farmers to maintain cultivation through mechanization.

The interaction terms between off-farm employment and village-level socialized service provision are all significant at the 1% level across the three models, confirming that agricultural services moderate the relationship between labor transfer and wheat cultivation. As shown in Table 8, Model 1 indicates that a richer service environment strengthens the positive impact of off-farm employment, reinforcing the “grain-oriented” tendency. In Model 2, a higher number of mechanized service providers (coefficient = 0.113) enhances the substitution of capital for labor, thereby amplifying the positive effect on wheat production. In Model 3, where both variables are included simultaneously, the interaction terms remain highly significant (0.114 and 0.134), suggesting that mechanized services play a more pronounced moderating role than general services. These services directly support key production stages such as plowing, sowing, and harvesting, offering vital assistance under labor shortages. Therefore, improving access to mechanized agricultural services is essential to realizing the goal of “off-farm without abandoning agriculture.”

Table 8.

Estimated Effects of Village-Level Socialized Service Provision on the Impact of Off-Farm Employment 1.

5. Conclusions

This paper utilizes micro-level data on wheat-growing households from the National Rural Fixed Observation Point Survey (2004–2021) [22] to systematically examine the impact of off-farm employment on wheat production and its underlying mechanisms. The main findings are as follows:

The positive effect of non-farm employment on wheat production becomes more pronounced when socialized services are widely accessible, mechanization can substitute for manual labor, and non-farm income exceeds the returns from competing cash crops. Socialized services, by providing mechanized operations and land outsourcing, effectively alleviate labor shortages in agriculture, allowing farmers to sustain wheat production even when primary household labor shifts to off-farm work.

Second, socialized agricultural services significantly moderate the relationship between off-farm employment and wheat production. An increase in off-farm income does not automatically lead to greater agricultural investment. However, the availability of mechanized services enables farmers to substitute external services for household labor, thereby ensuring continuity in production.

Third, the positive impact of off-farm employment on wheat cultivation is more evident in plain areas and among large-scale farmers. These regions and groups have better access to mechanization and resource integration, which facilitates labor substitution with capital and helps maintain production scale.

Fourth, the village-level supply of socialized services constitutes a key contextual factor shaping the impact of off-farm employment on agricultural production. In areas with more abundant service providers and better mechanization access, the positive effect of off-farm employment on wheat planting is more pronounced. The adequacy of local service provision largely determines whether farmers can mitigate labor shortages through outsourcing, serving as a critical safeguard for balancing labor transfer with stable grain production.

In conclusion, non-farm employment does not inherently undermine food production. Its ultimate impact depends on whether institutional support, service availability, and income structures allow farmers to reconfigure labor without sacrificing agricultural output.

Based on the above conclusions, this paper offers the following policy recommendations.

First, rural labor should be guided toward a balanced development between off-farm employment and grain production, in order to prevent farmland abandonment and ensure a stable foundation for food security. Second, the development of agricultural socialized service systems should be accelerated—particularly in core areas such as mechanized operations—to enhance accessibility, specialization, and service quality. This would enable off-farm income to be more effectively converted into agricultural investment. Third, agricultural mechanization should be promoted in a region-specific manner. Machinery and equipment should be adapted to the conditions of plains, hilly areas, and mountainous regions to improve both production efficiency and the resilience of grain supply. Fourth, a land transfer and allocation platform that integrates both urban and rural areas should be established to improve mechanisms for farmland exit and reallocation. This would ensure that producers with genuine willingness and capacity—especially professional farmers and new-type agribusiness operators—can access stable and appropriately scaled farmland resources over the long term. Fifth, to address the potential weakening of agricultural skills resulting from off-farm employment, a regularized system of agricultural training and high-quality farmer development should be established. In addition, mechanisms for identifying and incentivizing professional farmers should be improved, thereby strengthening human capital accumulation and promoting the intergenerational transfer of agricultural knowledge. These measures are essential to ensuring the long-term sustainability of grain production.

This paper provides a systematic analysis of the impact of non-farm employment on wheat cultivation behavior. However, several limitations remain and warrant further exploration in future research.

First, the study focuses on wheat sowing area as the core outcome variable, without incorporating other staple crops such as rice and maize. As a result, the findings primarily reflect adjustments within the structure of staple grain production, and may not fully capture the broader impact of non-farm employment on total grain output. Future research could expand the scope of analysis to include a wider range of crops to improve the generalizability of the conclusions.

Second, the study uses total expenditures on outsourced mechanized services as a proxy for socialized agricultural services and mechanization. While this measure partially reflects the substitution of household labor with machinery, it does not distinguish between equipment costs and hired labor costs, which may introduce measurement error. Future studies may improve indicator precision by incorporating more detailed cost data.

Third, the adoption of agricultural socialized services may be systematically correlated with unobserved farmer characteristics. If not properly controlled, this could result in endogeneity bias and estimation errors arising from omitted variables, thereby affecting the significance and explanatory power of the regression results. Although this study incorporates a rich set of control variables and applies individual fixed effects to minimize the influence of unobserved factors, future research should employ more rigorous identification strategies to further strengthen causal inference.

From the perspective of long-term impacts, several issues deserve closer examination. These include the potential weakening of agricultural skills, the allocation of non-farm income, and the reconfiguration of land resources. On the one hand, prolonged reliance on external services and reduced hands-on agricultural practice may lead to skill erosion, undermining the sustainability of agricultural production. On the other hand, existing studies show that non-farm income is often allocated to non-agricultural consumption such as education and housing, raising concerns about its potential to support long-term agricultural investment. In addition, as the trend of part-time farming continues to intensify, the shift in rural labor toward off-farm sectors poses challenges for optimal land allocation. Future research could explore how an improved farmland transfer system might help release underutilized land and ensure that producers with genuine agricultural capacity and willingness—particularly professional farmers—can access appropriately scaled land on a stable basis. These issues involve the interaction between household behavior, factor allocation, and institutional design, and merit more systematic analysis in future studies.

Author Contributions

M.W.: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation; W.Z.: resources, data curation, funding acquisition; H.C.: writing—review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition; N.J.: conceptualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China [grant number 23&ZD121], Ministry of Science and Technology of China [grant number 2023YFE0105000], and National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 72373142].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study were derived from the Rural Fixed Observation Point Survey Data administered by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. These data are not publicly available and must be formally requested from the Ministry.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this study, the authors used the Rural Fixed Observation Point Survey Data, a nationally representative panel dataset of farm households administered and maintained annually by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China. The dataset was used primarily for empirical analysis in this paper. All authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Minimum Procurement Prices of Wheat by Year 1.

Table A1.

Minimum Procurement Prices of Wheat by Year 1.

| Year | CNY/kg | Year | CNY/kg |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 0.69 | 2014 | 1.18 |

| 2007 | 0.69 | 2015 | 1.18 |

| 2008 | 0.72 | 2016 | 1.18 |

| 2009 | 0.83 | 2017 | 1.18 |

| 2010 | 0.86 | 2018 | 1.15 |

| 2011 | 0.93 | 2019 | 1.12 |

| 2012 | 1.02 | 2020 | 1.12 |

| 2013 | 1.12 | 2021 | 1.13 |

Note 1: National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), China.

Table A2.

Descriptive Statistics of Sample Characteristics.

Table A2.

Descriptive Statistics of Sample Characteristics.

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 77,202 | 58.69 | 12.09 | 16 | 94 |

| Party membership | 77,202 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0 | 1 |

| Gender | 77,202 | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0 | 1 |

| Agricultural training | 77,202 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0 | 1 |

| Health status | 77,202 | 1.90 | 1.03 | 1 | 5 |

| household labor size | 77,202 | 3.21 | 1.14 | 1 | 8 |

| Expenditure on Socialized Agricultural Services | 77,202 | 120.6 | 58.3 | 0 | 350 |

| supply level of socialized services | 77,202 | 210.63 | 129.47 | 12 | 1327 |

| supply level of mechanized socialized services | 77,202 | 163.27 | 122.64 | 5 | 1046 |

| Village-level economic development | 77,202 | 2.82 | 0.79 | 1 | 5 |

| Water-scarce village | 77,202 | 0.86 | 0.34 | 0 | 1 |

References

- Jia, X.; Cheng, M. Interprovincial migration of rural labor in China (1978–2021): Quantitative estimates and spatiotemporal characteristics. China Rural Econ. 2024, 6, 72–93. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Policy interpretation of “Opinions on Further Strengthening the Service and Protection of Migrant Workers”. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/202411/content_6989552.htm (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China; The State Council. Opinions on Learning from the “Thousand Villages Demonstration and Ten Thousand Villages Renovation” Project to Effectively PROMOTE Comprehensive Rural Revitalization. Available online: https://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/2025yhwj/yhwjhg_29973/202402/t20240204_6447014.htm (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Liao, L.; Guo, J.; Peng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ling, Y. Agricultural socialized services and grain yield per unit area: Empirical evidence from Jiangxi Province, China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1611236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Peng, C.; Mao, X. Non-farm employment, agricultural mechanization, and the adjustment of agricultural cropping structure. China Soft Sci. 2022, 6, 62–71. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L. Does off-farm work induce farmland abandonment? Evidence from China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2024, 16, 664–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, J.; Cui, Y. Does non-farm employment promote farmland abandonment of resettled households? Evidence from Shaanxi, China. Land 2024, 13, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wan, Q.; Bi, W. Off-farm employment and grain production change: New evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 63, 101519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Zhang, X.; Fan, S. The impact of migration on farm performance: Evidence from rice farmers in China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Jin, S.; Chen, K.; Riedinger, J.; Peng, C. Migration, local off-farm employment, and agricultural production efficiency: Evidence from China. J. Product. Anal. 2016, 45, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, N.; Wang, Y. Impacts of Rural Labor Resource Change on the Technical Efficiency of Crop Production in China. Agriculture 2017, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, S.; Deng, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H. Demographic shifts and agricultural production efficiency in the context of urban-rural transformation: Complex networks and geographic differences. Glob. Food Secur. 2025, 45, 100867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Y.; Wang, G.; Attipoe, S.G.; Han, D. Does off-farm employment contribute to chemical fertilizer reduction? New evidence from the main rice-producing area in Jilin Province, China. PloS ONE 2022, 17, e0279194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berhe, H.T. Non-farm Employment, Agricultural Inputs Investment, and Productivity Among Rural Households’ in Tigray (Northern Ethiopia). J. Quant. Econ. 2023, 22, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankrah, T.M.; Chandio, A.A.; Sargani, G.R.; Asara, I.; Zhang, H. Off-Farm Employment and Agricultural Credit Fungibility Nexus in Rural Ghana. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Eriksson, T.; Zhang, L. Off-farm employment, land renting and concentration of farmland in the process of urbanization. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2018, 10, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C. Off-farm employments and land rental behavior: Evidence from rural China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2016, 8, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Cao, S.; Qing, C.; Xu, D.; Liu, S. Does labour migration necessarily promote farmers’ land transfer-in?—Empirical evidence from China’s rural panel data. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 97, 534–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Chen, C.; Xie, J. Off-farm employment, farmland transfer and agricultural investment behavior: A study of joint decision-making among North China Plain farmers. J. Asian Econ. 2024, 95, 101839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, Q.; Fahad, S.; Kagatsume, M.; Yu, J. Impact of Off-Farm Employment on Farmland Transfer: Insight on the Mediating Role of Agricultural Production Service Outsourcing. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Xu, D. The impact of non-farm employment on the stable land contracting willingness of farm households: Evidence from rural China. Land Use Policy 2025, 157, 107688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China. National Fixed-Point Survey Data of Rural China (2004–2021) [Data Set]; Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs: Beijing, China, 2023.

- Wang, X.; Huang, J.; Rozelle, S. Off-farm employment and agricultural specialization in China. China Econ. Rev. 2016, 42, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBrauw, A. Seasonal Migration and Agricultural Production in Vietnam. J. Dev. Stud. 2010, 46, 114–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Wang, D.; Zheng, L. The impact of migration on agricultural restructuring: Evidence from Jiangxi Province in China. J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 47, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Causes and Consequences of Return Migration: Recent Evidence from China. J. Comp. Econ. 2002, 30, 376–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, T.H. Economic effects of labor migration on agricultural production of farm households in the Mekong River Delta region of Vietnam. Asian Pac. Migr. J. 2016, 25, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Hu, R.; Zhang, C. Impact of Rural–Urban Migration Experience on Rice Farmers’ Agricultural Machinery Expenditure: Evidence from China. Agriculture 2021, 11, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, H.R. Remittances, Household Expenditure and Investment in Guatemala. World Dev. 2010, 38, 1626–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, C.; Zenteno, R. Migration networks and microenterprises in Mexico. J. Dev. Econ. 2007, 82, 509–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wei, Y.; Liao, R.; Liu, J. The Role of Agricultural Socialized Services in Unlocking Agricultural Productivity in China: A Spatial and Threshold Analysis. Agriculture 2025, 15, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Liao, R.; Liu, J. The Role of Agricultural Socialized Services in Mitigating Rural Labor Shortages: A Multi-Crop Analysis of Production Performance. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Elahi, E.; Cao, F.; Yusuf, M.; Abro, M.L. Sustainable grain production growth of farmland—A role of agricultural socialized services. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, R.; Gao, Y.; Wang, J. Divergence between Willingness and Behavior of Farmers to Purchase Socialized Agricultural Services: From a Heterogeneity Perspective of Land Scale. Land 2022, 11, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Zhou, L.; Yi, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Han, X. The impact of agricultural machinery purchase subsidies on farmers’ machinery purchasing behavior: Empirical evidence from rice production in Jiangsu Province. China Rural Econ. 2010, 6, 38–48. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Wen, G. The development logic, practical constraints, and optimization pathways of agricultural socialized services. China Rural. Econ. 2023, 7, 21–35. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).