The Sustainable Development of Organic Agriculture: The Role of Wellness Tourism and Environmental Restorative Perception

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Introduction to Study Area

2.1. Environmental Restorative Perception

2.2. Place Attachment

2.3. Healthy Image of Tourism

2.4. Loyalty

2.5. Introduction to Study Area

3. Research Method

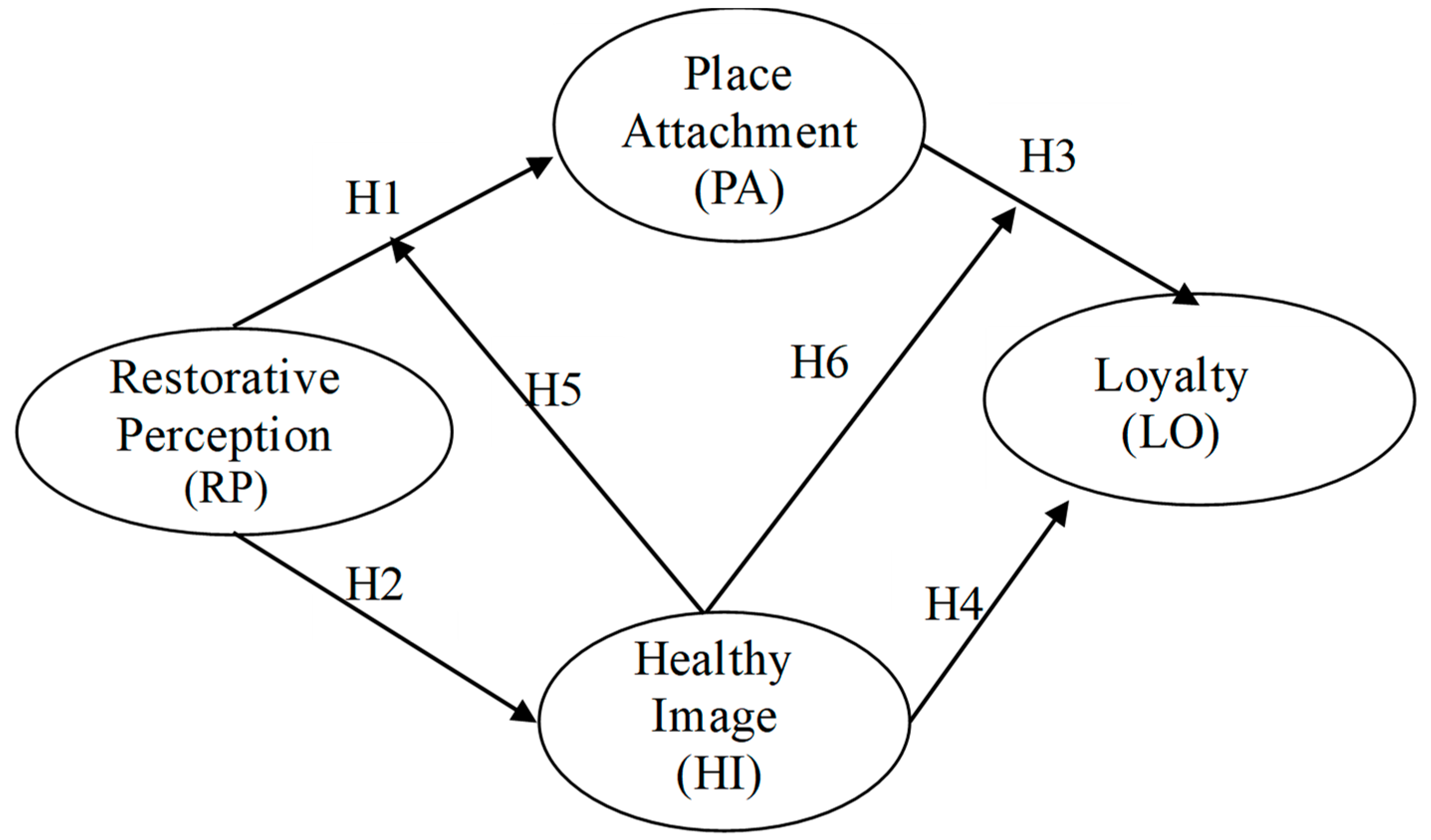

3.1. Research Structure and Hypotheses

3.1.1. Relationship between Restorative Perception and Place Attachment

3.1.2. Relationship between Restorative Perception and Healthy Image

3.1.3. Relationship between Place Attachment and Loyalty

3.1.4. Relationship between Healthy Image and Loyalty

3.1.5. Interference of Healthy Image

3.2. Questionnaire Design

3.3. Questionnaire Survey

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Sample Structure Analysis

4.2. Factor Analysis and Reliability Analysis

4.3. Solution of Modes

5. Results and Discussions

5.1. Results

5.2. Discussion

5.2.1. Restorative Perception Impacts on Place Attachment

5.2.2. Restorative Perception Impacts on Healthy Image

5.2.3. Place Attachment Impacts on Loyalty

5.2.4. Healthy Image Impacts on Loyalty

5.2.5. Healthy Image Moderates Both the Impact of Restorative Perception on Place Attachment and the Impact of Place Attachment on Loyalty

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Implications

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cooper, M.; Vafadari, K.; Hieda, M. Current Issues and Emerging Trends in Medical Tourism; IGI Global: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.-S.; Lee, T.J.; Ryu, K. The promotion of health tourism products for domestic tourists. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.R.; Godbey, G. The Sociology of Leisure; Venture Publishing Inc.: State College, PA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, T.J.; Ko, T.G. A comparative study of health tourism seekers and non-seekers’ satisfaction and subjective well-being evaluation: The case of Japanese and Korean tourists. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 742–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.A.; Mang, M.; Evans, G.W. Restorative effects of natural environment experiences. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, T.R.; Black, A.M.; Fountaine, K.A.; Knotts, D.J. Reflection and attentional recovery as distinctive benefits of restorative environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1997, 17, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Evans, G.W.; Jamner, L.D.; Davis, D.S.; Gärling, T. Tracking restoration in nature and urban field settings. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kuo, C.J.; Chang, C.H.; Hsieh, C.H. The study of relationship between recreation experience and perceived restoration in Nei-tung National Forest Recreation Area. J. Outdoor Recreat. Study 2010, 23, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Nearby Nature: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Choo, H.; Jamal, T. Tourism on organic farms in South Korea: A new form of ecotourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 431–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privitera, D. The importance of organic agriculture in tourism rural. Appl. Stud. Agribus. Commer. 2010, 4, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.C.; Liu, D.J.; Tseng, T.A. Establishing an organic agricultural tourism attachment model by integrating the means-end chain method and fuzzy aggregation operator. J. Outdoor Recreat. Study 2020, 33, 67–114. [Google Scholar]

- Laumann, K.; Garling, T.; Stormark, K.M. Rating scale measures of restorative components of environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Kaiser, F.G.; Bowler, P.A. Further Development of a Measure of Perceived Environmental Restorativeness; Institute for Housing Research, Uppsala University: Gävle, Sweden, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Scopelliti, M.; Giuliani, M.V. Choosing restorative environments across the lifespan: A matter of place experience. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 24, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.N.; Chiou, C.K. Exploring restorative perception of environment, place attachment on senior tourists’ psychological well-being. Leis. Soc. Res. 2016, 13, 71–89. [Google Scholar]

- Korpela, K.M.; Hartig, T.; Kaiser, F.; Fuhrer, U. Restorative experience and self-regulation in favorite place. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 573–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.C.; Huang, F.M.; Chou, H.C. The Relationships between environmental preference and restorative perception of environment: A case of moutainscape. J. Outdoor Recreat. Study 2008, 21, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kyle, G.; Graefe, A.; Manning, R.; Bacon, J. An examination of the relationship between leisure activity involvement and place attachment among hikers along the Appalachian trail. J. Leis. Res. 2003, 35, 249–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.J.; Hsieh, C.H.; Lin, S.Y. The relationships between environment preference and restorative perception of environment example in Xitou Nature Education Area. J. Archit. 2016, 97, 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.R.; Patterson, M.E.; Roggenbuck, J.W.; Watson, A.E. Beyond the commodity metaphor: Examining emotional and symbolic attachment to place. Leis. Sci. 1992, 14, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, M.V.; Feldman, R. Place attachment in a development and Culture context. J. Environ. Psychol. 1993, 13, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.L.; Graefe, A.R. Attachments to recreation settings: The case of rail-trail users. Leis. Sci. 1994, 17, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, A.; Yuksel, F.; Bilim, Y. Destination attachment: Effects on customer satisfaction and cognitive, affective and conative loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, V.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Payini, V.; Woosnam, K.M.; Mallya, J.; Gopalakrishnan, P. Visitors’ place attachment and destination loyalty: Examining the roles of emotional solidarity and perceived safety. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Jiang, J.; Van Winkle, C.M.; Kim, H.; Maruyama, N.E. Explaining festival impacts on a hosting community through motivations to attend. Event Manag. 2016, 20, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricker, K.S.; Kerstetter, D.L. Level of specialization and place attachment: An exploratory study of whitewater recreationists. Leis. Sci. 2000, 22, 233–257. [Google Scholar]

- Backlund, E.A.; Williams, D.R. A quantitative synthesis of place attachment research: Investigating past experience and place attachment. In Proceedings of the 2003 Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium, Bolton Landing, NY, USA, 6–8 April 2003; NE-317. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2004; pp. 320–325. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, M.J.; Brown, G. An empirical structural model of tourists and places: Progressing involvement and place attachment into tourism. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Aleshinloye, K.D.; Strzelecka, M.; Erul, E. The role of place attachment in developing emotional solidarity with residents. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Song, H.; Chen, N.; Shang, W. Roles of tourism involvement and place attachment in determining residents’ attitudes toward industrial heritage tourism in a resource-Exhausted city in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokols, D.; Shumaker, S.A. People in places: A transactional view of settings. In Cognition, Social Behavior, and Environment; Harvey, J., Ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1981; pp. 441–488. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, J.L. An assessment of the image of Mexico as vacation destination and the influence of geographical location upon that image. J. Travel Res. 1979, 17, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakeye, P.C.; Crompton, J.L. Image differences between prospective, first-time, and repeat visitors to the Lower Rio Grande Valley. J. Travel Res. 1991, 30, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.D. Image as a factor in tourism development. J. Travel Res. 1975, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisen, B. Image segmentation: The case of a tourism destination. J. Serv. Mark. 2001, 15, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-K.; Lee, Y.-K.; Lee, B. Korea’s destination image formed by the 2002 World Cup. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 839–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Tsai, D. How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.Q.; Qu, H. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, H.; Kaufmann, E.L. Wellness tourism: Market analysis of a special health tourism segment and implications for the hotel industry. J. Vacat. Mark. 2001, 7, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusby, C. Perceptions and Preferences of Wellness Travel Destinations of American Travelers. J. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 3, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hoyez, C. The world of yoga—The production and reproduction of therapeutic landscapes. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, S.J.; Veldkamp, C. Examination of the relationship between service quality and user loyalty. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 1995, 13, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramseook-Munhurruna, P.; Seebalucka, V.N.; PNaidoo, P. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, perceived value, tourist satisfaction and loyalty: Case of Mauritius. Procedia -Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 175, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Household Registration, Ministry of the Interior. Demographic Data in 2020. 2021. Available online: https://www.ris.gov.tw/app/portal/346 (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Food Next. The First Organic Village in Taiwan: Promoting the Organic Agricultural Tourism in Taiwan. Available online: https://www.foodnext.net/newstrack/paper/4098748220 (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Korpela, K.; Hartig, T. Restorative qualities of favorite places. J. Environ. Psychol. 1996, 16, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcu, A.; Uzzell, D.; Barnett, J. Making sense of unfamiliar risks in the countryside: The case of Lyme disease. Health Place 2011, 17, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, D.; Liu, Q.Y.; Ai, J.B.; Huang, Q.T.; Lan, S.R. The relationship between characteristics of the campus green space use and environmental restoration perception. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. 2018, 36, 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Addoms, D.L. Psychological and recreational benefits of a residential park. J. Leis. Res. 1981, 13, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattell, V.; Dines, N.; Gesler, W.; Curtis, S. Mingling, observing, and lingering: Everyday public spaces and their implications for well-being and social relations. Health Place 2008, 14, 544–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, T.H.; Ling, D.L.; Mao, H.F. The Relationship among Preference, Cogitative Psychological Benefit and Physical Response of Landscape Environment. J. Landsc. 2002, 8, 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Low, S.M.; Altman, I. Place attachment. In Place Attachment; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandris, K.; Kouthouris, C.; Meligdis, K. Increasing customers’ loyalty in a skiing resort: The contribution of place attachment and service quality. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 85, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ryan, C. Antecedents of tourists’ loyalty to Mauritius the role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Puczkó, L. Health and Wellness Tourism; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- DeBotton, A. The Art of Travel; Penguin: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, J. The spa is a model of an optimal healing environment. J. Altern. Compliment. Med. 2004, 10, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.D.; Zhang, J.S. The effect of service interaction orientation on customer satisfaction and behavioral intention: The moderating effect of dining frequency. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 1026–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, C.R.; Lin, W.R.; Lin, J.H. The relationships among recreation farming’ image, brand personality and travelers’ intention: The test of mediating effect of self- congruity. J. Outdoor Recreat. Study 2012, 25, 59–81. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C. A national customer satisfaction barometer: The Swedish experience. J. Marking 1992, 56, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwel, S.; Lingqiang, Z.; Asif, M.; Hwang, J.; Hussain, A.; Jameel, A. The influence of destination image on tourist loyalty and intention to visit: Testing a multiple mediation approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.Y. Business Research Methods; Hwai Tai Publishing: Taipei, Taiwan, 2019; p. 236. [Google Scholar]

- Guielford, J.P. Fundamental Statistics in Psychology and Education; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menatti, L.; Subiza-Perez, M.; Villapando-Flores, A.; Vozmediano, L.; San Juan, C. Place attachment and identification as predictors of expected landscape restorativeness. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 63, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Fu, W.; Zhuo, Z.; van den Bosch, C.C.K.; Huang, Q.; Lan, S. More meaningful, more restorative? Lingking local landscape characteristics and place attachment to restorative perceptions of urban park visitors. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 197, 103763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, T.R.; Strevey, S.J. Contact with nature, sense of humor, and psychological well-being. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 747–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.J.; Zhou, Y.W.; Li, Y.X.; Su, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, L.Q.; Ying, L.; Deng, W. Research on Color Space Perceptions and Restorative Effects of Blue Space Based on Color Psychology: Examination of the Yijie District of Dujiangyan City as an Example. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | SD | Critical Ratio | Item–To–Total Correlations | Cronbach Alpha If Item Deleted | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Being away (BAW) | Hartig, et al., (1997) [15], Laumann, et al., (2001) [14] Huang et al., (2008) [19] | |||||

| Away from urban hustle and bustle | 4.54 | 0.66 | 12.145 *** | 0.516 | 0.942 | |

| Away from worldly experiences | 4.39 | 0.73 | 13.021 *** | 0.535 | 0.942 | |

| A place where I can relax completely | 4.35 | 0.74 | 13.315 *** | 0.591 | 0.941 | |

| Free from trivial affairs | 4.35 | 0.66 | 21.901 *** | 0.734 | 0.940 | |

| Extent (EXT) | Hartig, et al., (1997) [15], Huang et al., (2008) [19] | |||||

| Environment integrating with nature | 4.41 | 0.67 | 19.306 *** | 0.664 | 0.941 | |

| Vast field landscape | 4.41 | 0.73 | 11.988 *** | 0.543 | 0.942 | |

| Extend many beautiful associations | 4.42 | 0.77 | 13.545 *** | 0.556 | 0.942 | |

| Fascination (FAS) | Laumann, et al., (2001) [14], Huang et al., (2008) [19] | |||||

| Environment deserves my stay | 4.37 | 0.66 | 16.104 *** | 0.586 | 0.942 | |

| Environment deserves my exploration | 4.32 | 0.70 | 20.343 *** | 0.695 | 0.940 | |

| Environment attracts my attention | 4.27 | 0.74 | 16.837 *** | 0.634 | 0.941 | |

| Compatibility (COM) | Laumann, et al., (2001) [14], Huang et al., (2008) [19] | |||||

| The environment is suitable to activities I like to do. | 4.36 | 0.72 | 18.229 *** | 0.698 | 0.940 | |

| I can enjoy myself in the place. | 4.29 | 0.72 | 20.684 *** | 0.724 | 0.940 | |

| I can quickly adapt to the environment. | 4.28 | 0.73 | 19.143 *** | 0.692 | 0.940 | |

| Place attachment (PA) | Moore and Graefe (1994) [24] Shen et al., (2020) [13] | |||||

| I like to visit organic village very much. | 4.13 | 0.78 | 18.688 *** | 0.667 | 0.940 | |

| I will consider organic village at the thought of travel. | 3.81 | 0.85 | 14.491 *** | 0.601 | 0.941 | |

| Identify organic agritourism development | 4.31 | 0.73 | 17.278 *** | 0.663 | 0.941 | |

| Deep love for the organic village | 4.01 | 0.82 | 16.818 *** | 0.656 | 0.941 | |

| Healthy image (HI) | Shen et al., (2020) [13] | |||||

| Image of health tourism | 4.38 | 0.67 | 15.820 *** | 0.623 | 0.941 | |

| Environment is good for physical health | 4.32 | 0.69 | 17.896*** | 0.691 | 0.940 | |

| Natural and healthy living environment | 4.46 | 0.71 | 13.765 *** | 0.557 | 0.942 | |

| Organic and non-toxic sustainable environment | 4.53 | 0.72 | 13.043 *** | 0.526 | 0.942 | |

| Loyalty (LO) | Oliver (1999) [44], Ramseook-Munhurruna et al., (2015) [47] Shen et al. (2020) [13] | |||||

| Loyalty to organic agriculture | 3.94 | 0.86 | 14.993 *** | 0.617 | 0.941 | |

| Loyalty to organic agricultural products | 3.89 | 0.85 | 14.390 *** | 0.601 | 0.942 | |

| Loyalty to organic agritourism | 4.08 | 0.79 | 15.266 *** | 0.588 | 0.942 |

| Items | Variables | N | % | Items | Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 160 | 39.0 | Occupation | Student | 113 | 27.6 |

| Female | 250 | 61.0 | Civil servant | 91 | 22.2 | ||

| Marital status | Single | 231 | 56.3 | Agriculture | 31 | 7.6 | |

| Married | 179 | 43.7 | Business | 48 | 11.7 | ||

| Age | 21–30 yrs | 156 | 38.0 | Service | 83 | 20.2 | |

| 31–40 yrs | 112 | 27.3 | Unemployed | 30 | 7.3 | ||

| 41–50 yrs | 98 | 23.9 | Others | 14 | 3.4 | ||

| Above 51 yrs | 44 | 10.7 | Monthly income (NT$) | <20,000 | 105 | 25.6 | |

| Education | Elementary and middle | 112 | 27.3 | 20,001–30,000 | 77 | 18.8 | |

| High school | 59 | 14.4 | 30,001–40,000 | 109 | 26.6 | ||

| College | 178 | 43.4 | 40,001–50,000 | 59 | 14.4 | ||

| Graduate and above | 61 | 14.9 | Above 50,001 | 60 | 14.6 |

| Constructs | M | SD | EV | Explanatory Variable V (%) | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Being away (BAW) | 4.39 | 0.57 | 2.627 | 65.668 | 0.811 | 0.880 | 0.657 |

| Extent (EXT) | 4.41 | 0.60 | 2.059 | 68.625 | 0.766 | 0.865 | 0.686 |

| Fascination (FAS) | 4.32 | 0.56 | 1.910 | 63.667 | 0.715 | 0.840 | 0.637 |

| Compatibility (COM) | 4.31 | 0.60 | 2.248 | 74.949 | 0.832 | 0.890 | 0.749 |

| Place attachment (PA) | 4.06 | 0.70 | 3.041 | 76.023 | 0.894 | 0.760 | 0.760 |

| Healthy image (HI) | 4.43 | 0.53 | 2.245 | 56.120 | 0.739 | 0.836 | 0.561 |

| Loyalty (LO) | 3.97 | 0.78 | 2.631 | 87.714 | 0.930 | 0.877 | 0.877 |

| Path | Coefficient | t-Value | E.V. | E. V. t-Value | C.R. | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP→BAW | 0.81 | 19.08 | 0.34 | 10.45 | 0.853 | 0.591 |

| RP→EXT | 0.77 | 17.89 | 0.40 | 11.59 | ||

| RP→FAS | 0.76 | 17.48 | 0.42 | 11.80 | ||

| RP→COM | 0.73 | 16.54 | 0.47 | 12.49 |

| Model | Non-Standardized Coefficient | Standardized Coefficient | t | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Value B | Standard Error | Beta Distribution | |||

| Constant | 1.243 | 0.440 | 2.826 | 0.005 | |

| RP | 0.451 | 0.200 | 0.324 | 2.249 | 0.025 |

| RP*HI | 0.048 | 0.024 | 0.283 | 2.000 | 0.046 |

| Model | Non-Standardized Coefficient | Standardized Coefficient | t | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Value B | Standard Error | Beta Distribution | |||

| Constant | 1.140 | 0.193 | 5.916 | 0.000 | |

| PA | 0.535 | 0.104 | 0.476 | 5.141 | 0.000 |

| PA * HI | 0.036 | 0.016 | 0.206 | 2.223 | 0.027 |

| Hypotheses | Coefficient | t-Value | Test | Test Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | 0.53 | 11.15 | p < 0.05 | Acceptance |

| H2 | 0.63 | 14.82 | p < 0.05 | Acceptance |

| H3 | 0.95 | 24.16 | p < 0.05 | Acceptance |

| H4 | 0.07 | 1.68 | p < 0.05 | Acceptance |

| H5 | 0.283 | 2.00 | p < 0.05 | Acceptance |

| H6 | 0.206 | 2.22 | p < 0.05 | Acceptance |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xue, L.-L.; Shen, C.-C. The Sustainable Development of Organic Agriculture: The Role of Wellness Tourism and Environmental Restorative Perception. Agriculture 2022, 12, 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12020197

Xue L-L, Shen C-C. The Sustainable Development of Organic Agriculture: The Role of Wellness Tourism and Environmental Restorative Perception. Agriculture. 2022; 12(2):197. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12020197

Chicago/Turabian StyleXue, Lin-Lin, and Ching-Cheng Shen. 2022. "The Sustainable Development of Organic Agriculture: The Role of Wellness Tourism and Environmental Restorative Perception" Agriculture 12, no. 2: 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12020197

APA StyleXue, L.-L., & Shen, C.-C. (2022). The Sustainable Development of Organic Agriculture: The Role of Wellness Tourism and Environmental Restorative Perception. Agriculture, 12(2), 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12020197