Abstract

Humic substances (HS), as important environmental components, are essential to soil health and agricultural sustainability. The usage of low-rank coal (LRC) for energy generation has declined considerably due to the growing popularity of renewable energy sources and gas. However, their potential as soil amendment aimed to maintain soil quality and productivity deserves more recognition. LRC, a highly heterogeneous material in nature, contains large quantities of HS and may effectively help to restore the physicochemical, biological, and ecological functionality of soil. Multiple emerging studies support the view that LRC and its derivatives can positively impact the soil microclimate, nutrient status, and organic matter turnover. Moreover, the phytotoxic effects of some pollutants can be reduced by subsequent LRC application. Broad geographical availability, relatively low cost, and good technical applicability of LRC offer the advantage of easy fulfilling soil amendment and conditioner requirements worldwide. This review analyzes and emphasizes the potential of LRC and its numerous forms/combinations for soil amelioration and crop production. A great benefit would be a systematic investment strategy implicating safe utilization and long-term application of LRC for sustainable agricultural production.

1. Introduction

Managing soil health is essential for its functional biodiversity, environmental sustainability, and crop productivity. Nowadays, around 33% of the global land is degraded and virtually unproductive due to various factors. The negative impact of intensive land use on soil properties and productivity is evidenced by a significant shift in the balance of humic substances (HS) and nutrients in arable soils over past decades [1,2,3]. This situation thereby affects the livelihood and food security of billions of people worldwide [4]. The annual demand for organic soil amendments is constantly increasing across the globe and makes it impossible to fulfill it with traditional types of organic matters. Sole utilization of chemical fertilizers hardens the soil, reducing soil fertility and polluting the natural environment [5].

Alternative sources for soil fertility management can be low-rank coal (LRC) and its derivatives. LRC is rich in a wide range of macro- and microelements and is also a valuable source of organic matter containing a high amount of HS [6]. For energy or industry applications, LRC is not economically feasible and therefore in the course of mining, it is usually sent to dumps. The amount of such low-rank coals is estimated during its detailed exploration and evaluation, while depends on the deposit structure and its location. However, there is no doubt that the overall LRCs amount is huge and has severely disturbed the natural environment [7]. LRC is enjoying rapidly growing application in agriculture as a fertilizer synergist due to its ability to ameliorate a broad range of soil properties. Particularly, LRC-derived HS, amended to the soil at specific rates and combinations can provide additional benefits for soil productivity [8].

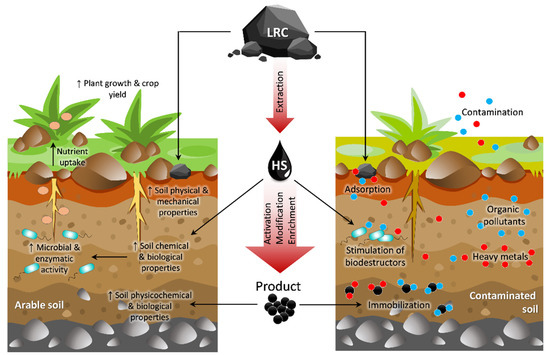

In light of the potential value of LRC, we sought to gain a better understanding of using LRC as an amendment/conditioner for soil health and plant development (Figure 1). The objectives of this review were to examine and to summarize various effects of LRC (i) on soil chemical characteristics including soil carbon (C) and nitrogen (N), soil organic matter (SOM), pH, cation exchange capacity (CEC); (ii) on soil physical properties, such as moisture, porosity, and bulk density; (iii) on soil biological properties, including microbial community, mineralization, and enzyme activity; and (iv) on plant growth response and crop productivity. The beneficial impact of LRC in addressing polluted soil is also considered (v).

Figure 1.

Low-rank coal and its derivatives provide a highly functional additive for soil fertility maintenance and plant growth stimulation. In addition, it is highly effective to immobilize and degrade various pollutants in soil, reducing their availability to plants.

2. LRC Types and Properties

Coal is considered one of the world’s most abundant and most important fossil fuels for power generation [9]. There are different types of coal that are characteristically distinct in few specific features, such as origin, composition, and coalification level [10]. Brown coal, known as lignite and sub-bituminous coal are classified as LRC due to the short formation time and low-grade metamorphism. Both have relatively low heat value and high ash content [11]. In addition, LRC, especially brown coal has a high moisture content, in the range of 25–65%, most of which exists as free water that rapidly evaporates under dry conditions [12].

The natural oxidation (weathering) of brown coal takes place on a large scale when the coal is in the seam or occurs during transportation/storage and significantly affects its physical properties and chemical composition [13]. As a result of oxidation, the valuable properties of fossil fuels deteriorate leading to extremely fast fragmentation and low calorific value. The resulting type of coal is called leonardite, named after Arthur Gray Leonard in recognition of his research contribution [14]. The interaction of coal with the atmosphere is a cause of great concern for the power sector and industry due to its gradual destruction, dispersion, and redeposition [15]. Moreover, LRC may combust spontaneously during mining and utilization, thereby causing air-polluting emissions [16]. Up to date, thousands of hectares of previously-fertile land functioning ecosystems are disturbed by coal mining and coal waste [17].

3. Impact of LRC on Soil Quality and Health

The application of LRC and its derivatives to agricultural soil is becoming a very common practice. Due to high levels of SOM in LRC, there is steady great interest in its use as a soil amendment and conditioner. Many studies have traced a wide range of benefits of applying LRC and its derivatives provisioning for physical, chemical, and biological functions of soil in mainly short-term practice (Table 1). It is important to note that the labile and humified organic matter of LRC has a decisive impact on soil health and fertility [18,19].

Table 1.

Selected short- to long-term effects of LRC and its derivatives on soil properties.

The SOM of LRC is characterized by its high content (<90% d.w.) of humic substances (HS) [43,44]. HS are mixtures of humic acid (HA, only soluble in water under alkaline conditions), fulvic acid (FA, soluble in water under all pH conditions) and humin (HM, neither soluble in alkali nor in acid) [45]. HS can be extracted from coal using alkali, acids, and organic solvents [46]. HS are relatively stable complexes and display diverse functional groups that help to create a healthy soil environment by improving soil aggregation, microbial activity, enzymatic functionality, carbon sequestration, nutrient retention, and pollutant immobilization [47,48]. The LRS-specific HS exhibit more carbonyl carbon (about 16%) and less aliphatic carbon (27%) compared to the typical soil-specific HS, containing about 11% and 31% respectively [43].

3.1. Effects of LRC on Soil Physical Properties

LRC accrue benefits for soil structure by enhancing its water retention ability, aggregate stability/porosity, aeration, and bulk density. The water holding capacity of brown coal HS due to its partial hydrophilicity and porous character is well-understood [49]. Piccolo et al. showed that coal-derived HS can improve the structure and water retention of degraded arable soils and argued that the higher the HS content, the better the water retention of soil [50]. Cihlar et al. [51] suggested that modification of brown coal HS by formaldehyde cross-linking may provide an effective strategy for achieving high water uptake kinetics. Oxidation may enhance the HA content of coal sources to be used as soil conditioners. Two independent experimental studies showed that nitric acid (HNO3) oxidation of brown coal leads to the increase of HA content with richer functional groups and ensures the retention rate of nutrients, which consequently improves soil aggregate stability and associated structure [52,53].

Brown coal-derived humic acid can reduce the disaggregating effects of cyclic wetting and drying on soil structural stability [54]. Soil porosity, an essential component of the soil skeleton structure and site productivity, can be maintained after coal mining by conducting site reclamation [55]. Being a rich source of carboxylic acid and phenolic hydroxyl functional groups, HS can provide reactive sites, increasing the CEC and the pH buffering of soils [56]. The high CEC of brown coal results in greater retention of NH4+ and consequently lowers the NO3− leaching loss [57].

Most of lignin oxygen-containing functional groups result in a low pH level when ionized in solution [58]. For this reason, LRC can be rather effective in neutral-to-alkaline soils. However, in combination with lime, brown coal is well suited for application to soils with a low pH. Imbufe et al. [59] have found LRC humates to be effective for increasing pH and electrical conductivity in acidic soils. Further acid ameliorating effects by LRC have been studied in different conditions [20]. According to another recent report, the LRC at a dose of 5 kg m−2 contributed to the decrease of electrical conductivity and sodium adsorption ratio of saline-sodic soils, whereas pH levels and bulk density displayed no significant changes [25].

3.2. Effects of LRC on Soil Organic Matter

The high content of TOC and its relatively slow mineralization suggest LRC be attractive for increasing plant nutrient supply in the soil the same way as known organo-mineral fertilizers [52]. The application of LRC by B. Dębska with colleagues [21] resulted in an increase in TOC content (by ~300%) and elevated soil organic carbon with higher aromaticity (38.6% compared to 35.4% in controls), which implies higher C sequestration potential and recalcitrance. Along with LRC, the LRC-derived humic acid products can outperform conventional organic wastes such as farmyard manure (FYM) in ameliorating soil quality and fertility [60]. Enhancement of SOC content and sequestration following LRC-derived HS is well-documented by R. Spaccini et al. [61].

3.3. Effects of LRC on Soil Heavy Metals and Other Pollutants

Good adsorptive properties of LRC have aroused intense interest for its potential as a versatile environmental adsorbent. The utilization of the coal-based HS in soil remediation [45,62,63,64] and water treatment systems (municipal wastewater and acid mine drainage) [65,66,67] are recently well-documented. Detoxification studies by research groups led by Qi and by Skłodowski [58,68] have employed LRC as an attractive low-cost adsorbent for the removal of different pollutants from the aquatic and terrestrial environments. The complex and heterogeneous coal matrix is created by amorphous polymers containing double- or triple-substituted aromatic rings which makes LRC highly suitable for immobilizing di- and trivalent metals in soil, consequently reducing their uptake by plants. Brown coal-derived HA has been used already multiple times for the environmentally beneficial adsorption of metal ions (Al3+, Pb2+, Fe3+, Ca2+, Mn2+, Mg2+, Cu2+, Ni2+, Co2+, Cd2+), that strongly reduced their mobility, bioavailability and phytotoxicity [69,70,71,72,73].

System of interactions between HA and dissolved metal ions creates a complex supramolecular network given by their heterogeneous, polyelectrolyte, and polydispersive character [74]. In comparison with HA/HS isolated from various soils, HA/HS from brown coal exhibit a remarkably high sorption capacity and a low desorption profile [75]. A. Pusz [76] showed that brown coal can be especially effectively employed on soils strongly contaminated with heavy metals, and suggested using it at the dose of around 90 t ha−1 (roughly equivalent to a dose 150 g pot−1 in their studies).

Coal-derived humic substances are considered to be effective for the extraction and concentration of many organic pollutants as well. The recovery degree of phenols using a magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles modified with HA from natural sources (brown coal, peat, chernozem, and sapropel) exceeded 94% [77]. The sorption rate of polar organic pollutants can be strongly influenced by the degree of the HS aromaticity [78]. Brown coal amendment to soil contaminated with the pesticide pentachlorophenol resulted in a distinct improvement of its biodegradation, enhancing the growth of the inoculated bacterial strain Comamonas testosteroni [79].

A summary of the effects of various LRC types on heavy metals mobility and uptake by plants in different soils is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

LRC application effectively reduces the bioavailability of heavy metals in the soil and their uptake by plants.

3.4. Effects of LRC on Soil Microbial and Biochemical Qualities

Application of exogenous organic matter is often critical to improving soil fertility and nutrient management. Only such a treatment can substantially stimulate microbial activity, root respiration, enzyme turnover and many other biological processes in soil. Studies assessing the impact of LRC on soil microbial community structure and activity are scarce. However, existing reports consistently show that LRC amendment increases soil microbial activity, manifesting in elevated soil respiration, higher enzyme activity, and larger CEC [36,84,85]. High specific surface area and porosity of LRC promotes ventilation and moisture retention, providing a favorable habitat for the growth and activity of microbial communities [31]. Activity levels of various hydrolytic and ligninolytic enzymes (including esterases, peroxidases, phenol oxidases as well as supporting enzymes, e.g., H2O2-generating oxidases; all predominantly of fungal origin) are strongly positively correlated with the enrichment of soil with LRC [86].

Due to its chemical and physical properties LRC act as a “storehouse” for nutrients that attracts soil microbial communities. Microorganisms with different physiological properties and metabolism transform LRC and generate HS through the so-called “ABCDE-system” (A = alkali, oxidative; B = biocatalysts; C = chelators; D = detergents; E = esterases) [87]. Microbially produced chelators and alkaline substances attack the macromolecular coal matrix and dissolve HS [87].

Metagenomic analyses revealed that both endophytic and epiphytic microorganisms are abundant in the LRC environment, as coal is generally originated from plant materials and therefore exhibits inherent plant interaction abilities [88,89,90]. LRC supplementation usually promotes the relative abundance of Actinobacteria. Due to their filamentous nature, these bacteria favor and can readily colonize the leonardite-rich environment [36,91]. Many members of Actinobacteria and Firmicutes are able to solubilize and depolymerize coal matrix [92,93,94]. However, further data regarding microbial functional responses to LRC exposure are inconsistent. Victorian brown coal had a short-term effect on the soil microbial community after 60 days of application, i.e., it temporarily increased the peroxidase and phenol oxidase activities, suppressed the heterotrophic respiration, and induced shifts among microbial populations [24]. Bekele et al. [34] observed that leonardite amendment had no effect on microbial biomass carbon (MBC) of the receiving subsoil, while application together with labile organic mix resulted in intermediate MBC values. It is important to note that the current understanding of microbial colonization and its activity is mainly drawn from short-term studies; thus, more testing should be done yet, especially focusing on long-term studies.

4. Impact of LRC on Plant Growth and Crop Yield

Among the main benefits of using LRC as soil amendments are the enhancement of plant growth and stress resistance. Some coal-derived HS is promoted commercially as plant growth stimulants and regulators. However, despite multiple publications showing the positive effects of coal derivatives on plant growth, the success of commercial coal-derived products in agriculture varies and so there is a relative lack of statistical evidence of its effectiveness. Furthermore, most of commercial products are highly complex and contain mixtures of organic matters as well as added plant nutrients, which makes it difficult to identify the individual effect of HS [95].

While several studies have confirmed the beneficial role of coal-derived products on plant growth, only a few have specifically examined the direct impact of LRC (Table 3). Part of the reason for this is the wide range in physicochemical and functional properties that make LRC substantially less predictable regarding plant-stimulating behavior compared to other soil amendments of a known chemical structure [96]. In addition, depending on the used LRC type, the selected plant and soil, as well as on environmental conditions, the actual efficiency of an amendment can vary dramatically.

Table 3.

Response of various plants to soil supplementation with LRC derivatives/compositions.

Table 3 overviews the studies on plant growth-promoting activity of LRC and its products. The majority of applications were conducted in hydroponic, soil-less, or field conditions. On the one hand, in most cases, significant plant-growth stimulation was observed in response to LRC derivatives/compositions. For example, Amoah-Antwi et al. [8] reported that LRC applications provide long-term soil quality benefits and adequate protection against pollution, which results in reduced net abatement costs. On the other hand, the observed effects were inconsistent across the studies, depending on the type of plant treated, soil classes tested and the manner of product application.

Rose et al. [95] ranked the factors contributing to positive plant-growth promotion using a boosted regression tree (BRT) and demonstrated that application rate, HS source, and plant type were the key factors regulating HS impact on the shoot and root growth, while the growth media employed and the location of application played a negligible role. HS can influence plant growth directly, by acting on physiological and metabolic plant processes, and indirectly, by modification of soil characteristics [115,116].

For example, hormone-like and catalytic activities of HS directly stimulate shooting and rooting of plants [117]. Moreover, some studies suggest that HS may directly stimulate activity of H+-ATPase and ion transporters in the root plasma membrane, consequently enhancing nutrient acquisition [101,118]. The best documented indirect effects of HS include: improvement in soil structure, pH buffering, CEC, and water retention capacity, as well as enhancement in nutrient bioavailability (particularly P, Fe, K, Zn, and N) and reduction of toxicity of heavy metals [119,120]. Presence of abiotic environmental stress factors, such as salinity, nutrient deficiency, and heavy metal toxicity plays a big role in shaping the root growth response to HS [121]. High content of (coal-derived) HS, alleviates salinity stress presumably by binding excess cations [95].

The studies devoted to the impact of LRC supplementation specifically on the crop yield are addressed in the Table 4. A general conclusion that can be drawn from the studies listed here is that the response of crop yield to LRC is mainly affected by its origin, level of coalification, rate/dose, form/mode of application. Crop yield is also dependent on specific plant responses, soil type, and environmental conditions.

Table 4.

The crop yield response to application of LRC derivatives/compositions.

5. Application Forms of LRC for Soil Amendment and Fertility Management

5.1. Sole LRC and HS Application

As shown and discussed above, LRC has the ability to immobilize pollutants meanwhile making important nutrients and microelements more easily accessible for plants. Many commercial products are derived from coal matrices and mainly sold as humates and humalite [142]. LRC-based fertilizers, such as Rekulter, Actosol and others are successfully used in agricultural practice [18,21]. LRC or LRC-derived products can be formulated as soluble slow-release granules, powders, or even liquids that are applied either directly to the soil or as a foliar spray [33,143,144]. Products might vary in concentration of, for example, HS, specific HS extraction methods, and the composition of incorporated nutrients.

The mechanisms that lie behind the fertilizing activity of sole LRC and its derivatives can be (i) ion-exchange groups capable of complexing or adsorbing and (ii) high porosity that optimizes storage of water and nutrients, thus contributing to their adequate availability [145]. Moreover, considerable research efforts have been aimed to modify LRC using solid-phase activation techniques to improve its pore structure and nutrient uptake [26].

Chemical properties and structural characteristics of LRC facilitate biofunctionality with a wide variety of soil constituents. The extensive surface area, porous structure, and functional groups of coal are used to design slow- or controlled-release soil amendments. A popular solution to further increment the fertilizing value of LRC derivatives is supplementation with mineral fertilizers NPK (recommended doses are variable depending on soil type) [18,30,146]. Some other interesting types of LRC-modifications have been proposed as well and will be briefly reviewed in the following sections. Here it is important to note that careful characterization and assessment of parent LRC with respect to the potential synergistic amendments are key aspects of positive performance outcomes.

5.2. Amendments Used along with LRC

5.2.1. Coal-Urea Fertilizers

Nitrogen (N) is one of the most important nutrients for agricultural crop production. Annually large volumes of synthetic N fertilizers are applied to improve soil fertility and productivity. However, more than 50% of N fertilizers added to soil are commonly lost through volatilization and leaching, resulting in groundwater pollution, plant diseases, N2O emissions, etc. [147,148]. Furthermore, long-term excessive fertilizer applications may deteriorate soil physical properties, reduce TOC and basic cation content, in consequence increasing soil acidification [149]. The depletion of SOC due to intensive agriculturalization can be a further cause for declining fertilizer N efficiency since SOC plays a pivotal role in the retention of soil N and limits its losses [150].

On the contrary, combining LRC rich in HS with N fertilizer would allow normalization of nutrient uptake by plants and would help to decrease N losses in the soil from excess N fertilizer application [21]. In recent years, various kinds of urea-N loaded brown coal have been developed and investigated for their potential to increase soil quality [24,27]. It was shown that LRC indeed reduces volatilization loss of N from urea-amended soil by inhibiting urease activity, thus increasing urea-N availability for plants [151,152]. Some studies already demonstrated that LRC can be also successfully employed in the synthesis of controlled-release fertilizers based on urea, formaldehyde, and KH2PO4 [107,153]. More recently, LRC-urea granulates came into focus since they offer good predictable performance, the vast availability of the substrate, and a standardized production process [112,139].

5.2.2. Combination with Coal Solubilizing Bacteria

The effect of added LRC on the chemical and biological properties of soil is expectedly greater if applied in conjunction with active strains of coal solubilizing bacteria. A number of species of Escherichia, Pseudomonas, Streptomyces, Bacillus, Staphylococcus, and Rhodococcus are capable to release humic organic matter through biotransformation of the coal [154,155,156,157]. Co-application of LRC and exogenous Bacillus mycoides, Microbacterium sp. and Acinetobacter baumannii increased the soil respiration and microbiological activity [25,31].

Experiments from Jeong et al. [126] by using a hydroponic lettuce culture showed that microorganisms were directly and actively participating in plant growth stimulation by HS.

5.2.3. LRC and Biochar

Another sustainable alternative to the application of conventional organics fertilizers is represented by LRC combined with biochar produced on a laboratory and industrial scale. Biochar is produced through the pyrolysis of biomass and like LRC possesses high stability against decay and a superior ability to retain nutrients in soil [158]. Biochar and LRC have many common physicochemical and biological characteristics, such as extensive surface area, porous structure, chemical functional groups, high water-holding, and CEC [159,160]. The synergetic employing these materials may provide a long-term positive effect on SOM, thereby building up a sustainable form of C [161]. The utilization of biochar and LRC alternatively or in the mixture to improve soil health and plant growth is well documented by many authors [8,34,48].

5.3. LRC in Composting Technologies

Composting is a cost-effective and sustainable process of conversion of various organic wastes into compost [162]. However, composting can be related to a high loss of N through NH3 volatilization [163]. In turn, NH3 poses negative effects on ecosystems and indigenous biodiversity [164]. Existing strategies to mitigate nitrous emissions and retain N during composting include using bulking agents, bedding materials, microbial and/or chemical amendments, and optimization of composting duration/conditions [165]. However, these approaches are not widely recognized due to the difficulties and limitations in commercial on-farm implementation [166]. Due to its excellent absorption properties, brown coal may suppress NH3 volatilization in composted material [99]. This was confirmed in recent studies where NH3 emissions were significantly reduced by brown coal additives (Table 5). Good N retention by brown coal can be also attributed to better N mineralization and inhibition of compost urease activity, resulting in a lower rate of NH3 production and emission [167]. We argue that the LRC-based technologies can be especially effectively used in the processing of livestock and poultry manure to reduce environmental impacts and improve efficiency.

Table 5.

Investigated effects of brown coal applications on NH3 emission or N retention from various composting systems.

6. Knowledge Gaps, Needs, and Concerns

LRC is an abundant and valuable resource but there are critical issues that must be addressed to facilitate its agronomic value:

- Consideration of the issues related to long-term soil behavior under LRC loading is important for interpreting lasting soil quality changes since most of the described applications of LRC have been derived from short- to medium-term studies [8,95].

- Only limited work has been performed so far to investigate the inherent chemical heterogeneity and functional diversity LRC as soil amendment and there are still uncertainties regarding the chemical mechanisms of LRC as flow-release fertilizer.

- Since the most common techniques for producing HS from coal based on alkaline extraction, it may be unable to achieve its purpose of separating humic from non-humic substances (i.e., from functional biomolecules, their partial decomposition products, and from microbial residues) [172]. There was an apparent lack of relationship between biological functioning of OM and its alkaline extractability [173].

- A weakly acidic nature may make LRC unsuitable for amending many contaminated soils [48]. Consequently, mitigation of soil acidification via liming should be considered. Researches have however demonstrated that LRC when used in heavy metal-polluted soils increment buffering capacity of soil [174,175].

- Most coal-derived HS are combined with Ca and Mg, which have poor solubility in water and weak decomposability in soil, thereby demanding activation processes to convert it into more suitable forms, e.g., brown coal is usually pretreated with strong oxidants [176,177].

- Depending on origin and quality, LRC may itself contain elevated levels of organically-bound chlorides and inorganic constituents, implying a conceivable risk of soil contamination by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and heavy metals [178,179].

- Causes of suboptimal outcomes applying LRC products can be attributed to the manufacturer’s recommended rate with limited knowledge of optimal rates, timing, and methods of application for a given plant-soil combination [33].

- Systematic experimental evidence concerning the amendment dose/rate depending on the soil type, environmental conditions is still missing, resulting in a lack of theoretical models and full understanding regarding plant growth-response to LRC amendment.

The selection criteria for LRC amendment should integrate environmental and agronomic factors, such as soil quality, material availability, economic accessibility, cost, application needs, safety compliance, and sustainability [8].

7. Conclusions

Coal seams and spoils generated during mining and processing operations, are generally considered economically non-viable and deteriorating public and environmental health. However, according to numerous existing studies and interdisciplinary evaluations, low-rank coals could be successfully used for the production of soil amendments/conditioners and reclamation of disturbed lands. Different types and combinations of LRC applied to the soil at specific rates can provide various short- to medium-term benefits, i.e., ameliorate soil structure, improve nutrient mobility, stimulate microbial and enzymatic activity; enhance soil productivity and crop yield. Potentially in a long-term perspective, LRC can serve as a stable source of SOM. However, thorough consideration and careful matching of the involved components and specific factors (soil, crop, LRC, location, etc.) is of paramount importance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S.A. and I.D.; software, K.T.T.; validation, N.S.A., I.D. and D.B.J.; formal analysis, D.K.S.; investigation, N.S.A.; resources, K.T.T.; data curation, D.K.S. and N.P.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.S.A.; writing—review and editing, I.D.; visualization, D.B.J.; supervision, I.D.; project administration, K.T.T.; funding acquisition, N.S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP08855394).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Maximillian, J.; Brusseau, M.L.; Glenn, E.P.; Matthias, A.D. Pollution and Environmental Perturbations in the Global System; Brusseau, M.L., Pepper, I.L., Gerba, C.P., Eds.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 457–476. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.; Siebert, J.; Eisenhauer, N.; Schädler, M. Climate change and intensive land use reduce soil animal biomass via dissimilar pathways. eLife 2020, 9, 54749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pukalchik, M.; Kydralieva, K.; Yakimenko, O.; Fedoseeva, E.; Terekhova, V. Outlining the Potential Role of Humic Products in Modifying Biological Properties of the Soil—A Review. Front. Environ. Sci. 2019, 7, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhilash, P. Restoring the Unrestored: Strategies for Restoring Global Land during the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (UN-DER). Land 2021, 10, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahalvi, H.N.; Rafiya, L.; Rashid, S.; Nisar, B.; Kamili, A.N. Chemical Fertilizers and Their Impact on Soil Health BT—Microbiota and Biofertilizers. In Ecofriendly Tools for Reclamation of Degraded Soil Environs; Dar, G.H., Bhat, R.A., Mehmood, M.A., Hakeem, K.R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Akimbekov, N.; Digel, I.; Abdieva, G.; Ualieva, P.; Tastambek, K. Lignite biosolubilization and bioconversion by Bacillus sp.: The collation of analytical data. Biofuels 2021, 12, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, X.; Hou, L.; Shao, A. Impact of the Coal Mining on the Spatial Distribution of Potentially Toxic Metals in Farmland Tillage Soil. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah-Antwi, C.; Kwiatkowska-Malina, J.; Fenton, O.; Szara, E.; Thornton, S.F.; Malina, G. Holistic Assessment of Biochar and Brown Coal Waste as Organic Amendments in Sustainable Environmental and Agricultural Applications. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendryx, M.; Zullig, K.J.; Luo, J. Impacts of Coal Use on Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2020, 41, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Finkelman, R.B. Coal as a promising source of critical elements: Progress and future prospects. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2018, 186, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Zheng, J.; Liu, X. Effect of Hydrothermal Dehydration on the Slurry Ability of Lignite. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 12027–12035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Liao, J.; Mo, Q.; Wen, Y.; Bao, W.; Chang, L. Evolution of Pore Structure during Pressurized Dewatering and Effects on Moisture Readsorption of Lignite. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 7113–7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisupati, S.V.; Scaroni, A.W. Natural weathering and laboratory oxidation of bituminous coals: Organic and inorganic structural changes. Fuel 1993, 72, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Ding, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, G.; Sun, J.; Ding, Q. Characterization of humic acids derived from Leonardite using a solid-state NMR spectroscopy and effects of humic acids on growth and nutrient uptake of snap bean. Chem. Speciat. Bioavailab. 2015, 27, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumins, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Yan, M.; Klavins, M. A study of weathered coal spectroscopic properties. Energy Procedia 2017, 128, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brune, J.F. 6-Mine Ventilation Networks Optimized for Safety and Productivity. In Advances in Productive, Safe, and Responsible Coal Mining; Hirschi, J., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Manna, A.; Maiti, R. Geochemical contamination in the mine affected soil of Raniganj Coalfield—A river basin scale assessment. Geosci. Front. 2018, 9, 1577–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarkowska, K.; Sołek-Podwika, K.; Filipek-Mazur, B.; Tabak, M. Comparative effects of lignite-derived humic acids and FYM on soil properties and vegetable yield. Geoderma 2017, 303, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, J.; Hoffmann, K. The Utilization of Peat, Lignite and Industrial Wastes in the Production of Mineral-Organic Fertilizers. Am. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2007, 2, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazawa, Y.; Wong, M.; Gilkes, R.; Yamaguchi, T. Effect of additions of brown coal and peat on soil solution composition and root growth in acid soil from wheatbelt of western Australia. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2000, 31, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębska, B.; Maciejewska, A.; Kwiatkowska, J. The effect of fertilization with brown coal on Haplic Luvisol humic acids. Plant Soil Environ. 2011, 48, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ece, A.; Saltali, K.; Eryigit, N.; Uysal, F. The effects of leonardite applications on climbing bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) yield and the some soil properties. J. Agron. 2007, 6, 480–483. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowska, J.; Provenzano, M.; Senesi, N. Long term effects of a brown coal-based amendment on the properties of soil humic acids. Geoderma 2008, 148, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, C.K.T.; Rose, M.T.; Cavagnaro, T.; Patti, A. Lignite amendment has limited impacts on soil microbial communities and mineral nitrogen availability. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2015, 95, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubillos-Hinojosa, J.G.; Valero, N.; Peralta Castilla, A.D.J. Effect of a low rank coal inoculated with coal sol-ubilizing bacteria for the rehabilitation of a saline-sodic soil in field conditions. Rev. Fac. Nac. De Agron. Medellín 2017, 70, 8271–8283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Gao, B.; Wan, Y.; Li, Y.C.; Cheng, D. Activated-Lignite-Based Super Large Granular Slow-Release Fertilizers Improve Apple Tree Growth: Synthesis, Characterizations, and Laboratory and Field Evaluations. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 5879–5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, B.K.; Rose, M.T.; Wong, V.; Cavagnaro, T.; Patti, A.F. Hybrid brown coal-urea fertiliser reduces nitrogen loss compared to urea alone. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 601–602, 1496–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, B.K.; Rose, M.T.; Wong, V.N.L.; Cavagnaro, T.R.; Patti, A.F. Nitrogen Dynamics in Soil Fertilized with Slow Release Brown Coal-Urea Fertilizers. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, L.; Song, F.; Song, X.; Guo, X.; Lu, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, N.; Zou, J.; Zhang, P. Effects of different types of humic acid isolated from coal on soil NH3 volatilization and CO2 emissions. Environ. Res. 2021, 194, 110711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharif, M.; Khattak, R.A.; Sarir, M.S. Effect of different levels of lignitic coal derived humic acid on growth of maize plants. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2002, 33, 3567–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubillos-Hinojosa, J.G.; Valero, N.; Melgarejo, L.M. Assessment of a low rank coal inoculated with coal solubilizing bacteria as an organic amendment for a saline-sodic soil. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2015, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iakimenko, O.S. Commercial Humates from Coal and Their Influence on Soil Properties and Initial Plant Development BT-Use of Humic Substances to Remediate Polluted Environments. In From Theory to Practice; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 365–378. [Google Scholar]

- Little, K.R.; Rose, M.; Jackson, W.R.; Cavagnaro, T.R.; Patti, A.F. Do lignite-derived organic amendments improve early-stage pasture growth and key soil biological and physicochemical properties? Crop. Pasture Sci. 2014, 65, 899–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, A.; Roy, J.L.; Young, M.A. Use of biochar and oxidized lignite for reconstructing functioning agronomic topsoil: Effects on soil properties in a greenhouse study. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2015, 95, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placek, A.; Grobelak, A.; Hiller, J.; Stępień, W.; Jelonek, P.; Jaskulak, M.; Kacprzak, M. The role of organic and inorganic amendments in carbon sequestration and immobilization of heavy metals in degraded soils. J. Sustain. Dev. Energy Water Environ. Syst. 2017, 5, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimbekov, N.; Qiao, X.; Digel, I.; Abdieva, G.; Ualieva, P.; Zhubanova, A. The Effect of Leonardite-Derived Amendments on Soil Microbiome Structure and Potato Yield. Agriculture 2020, 10, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjumend, T.; Abbasi, M.K.; Rafique, E. Effects of lignite-derived humic acid on some selected soil proper-ties, growth and nutrient uptake of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) grown under greenhouse conditions. Pak. J. Bot. 2015, 47, 2231–2238. [Google Scholar]

- Canarutto, S.; Pera, A.; La Marca, M.; Vallini, G. Effects of Humic Acids from Compost-Stabilized Green Waste or Leonardite on Soil Shrinkage and Microaggregation. Compos. Sci. Util. 1996, 4, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdrighi, M.; Pera, A.; Scatena, S.; Agnolucci, M.; Vallini, G. Effects of Humic Acids Extracted from Mined Lignite or Composted Vegetable Residues on Plant Growth and Soil Microbial Populations. Compos. Sci. Util. 1995, 3, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannouli, A.; Kalaitzidis, S.; Siavalas, G.; Chatziapostolou, A.; Christanis, K.; Papazisimou, S.; Papanicolaou, C.; Foscolos, A. Evaluation of Greek low-rank coals as potential raw material for the production of soil amendments and organic fertilizers. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2009, 77, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, C.; Lashari, M.S.; Deng, J.; Du, Z. Impact of flue gas desulfurization gypsum and lignite humic acid application on soil organic matter and physical properties of a saline-sodic farmland soil in Eastern China. J. Soils Sediments 2016, 16, 2175–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, A.D.; Randall, P.J.; James, T.R. Evaluation of two coal-derived organic products in ameliorating surface and subsurface soil acidity. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 1995, 46, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Córdova-Kreylos, A.L.; Yang, J.; Yuan, H.; Scow, K.M. Humic acids buffer the effects of urea on soil ammonia oxidizers and potential nitrification. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 1612–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anemana, T.; Óvári, M.; Szegedi, Á.; Uzinger, N.; Rékási, M.; Tatár, E.; Yao, J.; Streli, C.; Záray, G.; Mihucz, V.G. Optimization of Lignite Particle Size for Stabilization of Trivalent Chromium in Soils. Soil Sediment Contam. Int. J. 2020, 29, 272–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Tang, C.; Antonietti, M. Natural and artificial humic substances to manage minerals, ions, water, and soil microorganisms. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 6221–6239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, F.; Bragança, S.R. Extraction and characterization of humic acid from coal for the application as dispersant of ceramic powders. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2018, 7, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikos-Szymańska, M.; Schab, S.; Rusek, P.; Borowik, K.; Bogusz, P.; Wyzińska, M. Preliminary Study of a Method for Obtaining Brown Coal and Biochar Based Granular Compound Fertilizer. Waste Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 3673–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah-Antwi, C.; Kwiatkowska-Malina, J.; Thornton, S.F.; Fenton, O.; Malina, G.; Szara, E. Restoration of soil quality using biochar and brown coal waste: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 722, 137852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, F.J. Humus Chemistry: Genesis, Composition, Reactions; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo, A.; Pietramellara, G.; Mbagwu, J. Effects of coal derived humic substances on water retention and structural stability of Mediterranean soils. Soil Use Manag. 1996, 12, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cihlář, Z.; Vojtová, L.; Conte, P.; Nasir, S.; Kucerik, J. Hydration and water holding properties of cross-linked lignite humic acids. Geoderma 2014, 230–231, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Xing, S.; Du, Z. Nitric Acid Oxidation for Improvement of a Chinese Lignite as Soil Conditioner. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2011, 42, 1782–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, S.S.; Seng, L.; Chong, W.N.; Asing, J.; Nor, M.F.B.M.; Pauzan, A.S.B.M. Characterization of the coal derived humic acids from Mukah, Sarawak as soil conditioner. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2006, 17, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, A.; Pietramellara, G.; Mbagwu, J. Use of humic substances as soil conditioners to increase aggregate stability. Geoderma 1997, 75, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Du, Y.; Chen, B.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, Y. Variation in shallow sandy loam porosity under the influence of shallow coal seam mining in north-west China. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2020, 38, 1349–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skodras, G.; Kokorotsikos, P.; Serafidou, M. Cation exchange capability and reactivity of low-rank coal and chars. Open Chem. 2014, 12, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramashivam, D.; Clough, T.; Carlton, A.; Gough, K.; Dickinson, N.; Horswell, J.; Sherlock, R.R.; Clucas, L.; Robinson, B.H. The effect of lignite on nitrogen mobility in a low-fertility soil amended with biosolids and urea. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 543, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Hoadley, A.F.; Chaffee, A.L.; Garnier, G. Characterisation of lignite as an industrial adsorbent. Fuel 2011, 90, 1567–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbufe, A.U.; Patti, A.F.; Surapaneni, A.; Jackson, R.; Webb, A. Effects of brown coal derived materials on pH and electrical conductivity of an acidic vineyard soil. In Proceedings of the 3rd Australian New Zealand Soils Conference, Sydney, Australia, 5–9 December 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowska-Malina, J. The Influence of Exogenic Organic Matter on Selected Chemical and Physicochemical Properties of Soil. Pol. J. Soil Sci. 2016, 48, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Spaccini, R.; Piccolo, A.; Conte, P.; Haberhauer, G.; Gerzabek, M.H. Increased soil organic carbon sequestration through hydrophobic protection by humic substances. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 1839–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Muhmood, A.; Dong, R.; Wu, S. Synthesis of humic-like acid from biomass pretreatment liquor: Quantitative appraisal of electron transferring capacity and metal-binding potential. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, S.; Fu, Q.; Antonietti, M. Conjugation of artificial humic acids with inorganic soil matter to restore land for improved conservation of water and nutrients. Land Degrad. Dev. 2019, 31, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Bechtel, A.; Eble, C.F.; Flores, R.M.; French, D.; Graham, I.T.; Hood, M.M.; Hower, J.C.; Korasidis, V.A.; Moore, T.A.; et al. Recognition of peat depositional environments in coal: A review. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2020, 219, 103383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.; Bora, M.; Tamuly, J.; Benoy, S.M.; Baruah, B.P.; Saikia, P.; Saikia, B.K. Coal-derived humic acid for application in acid mine drainage (AMD) water treatment and electrochemical devices. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2021, 8, 1479–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Du, Q.; Cheng, K.; Antonietti, M.; Yang, F. Efficient phosphorus recycling and heavy metal removal from wastewater sludge by a novel hydrothermal humification-technique. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 394, 124832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, N.; Jamal, A.; Huang, Z.; Liaquat, R.; Ahmad, B.; Haider, R.; Ali, M.I.; Shoukat, T.; Alothman, Z.A.; Ouladsmane, M.; et al. Extraction and Chemical Characterization of Humic Acid from Nitric Acid Treated Lignite and Bituminous Coal Samples. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skłodowski, P.; Maciejewska, A.; Kwiatkowska, J. The effect of organic matter from brown coal on bioavailability of heavy metals in contaminated soils. In Soil and Water Pollution Monitoring, Protection and Remediation; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 299–307. [Google Scholar]

- Perdue, E.M. Modeling Concepts in Metal-Humic Complexation. Soil Health Substances and Chemical Contaminants. Soil Health Ser. 2015, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauletbay, A.; Serikbayev, B.A.; Kamysbayev, D.K.; Kudreeva, L.K. Interaction of metal ions with humic acids of brown coals of Kazakhstan. J. Exp. Nanosci. 2020, 15, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, M.; Olaetxea, M.; Baigorri, R.; Zamarreño, A.M.; Etienne, P.; Laîné, P.; Ourry, A.; Yvin, J.-C.; Garcia-Mina, J.M. Main binding sites involved in Fe(III) and Cu(II) complexation in humic-based structures. J. Geochem. Explor. 2013, 129, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Chen, S.; Yuan, Y.; Lu, Q. Influence of Humic Acid Complexation with Metal Ions on Extracellular Electron Transfer Activity. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmler, M.; Ciadamidaro, L.; Schulin, R.; Madejón, P.; Reiser, R.; Clucas, L.; Weber, P.; Robinson, B. Lignite Reduces the Solubility and Plant Uptake of Cadmium in Pasturelands. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 4497–4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klučáková, M.; Pavlíková, M. Lignitic Humic Acids as Environmentally-Friendly Adsorbent for Heavy Metals. J. Chem. 2017, 2017, 7169019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekař, M.; Klučáková, M. Comparison of Copper Sorption on Lignite and on Soils of Different Types and Their Humic Acids. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2008, 25, 1123–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusz, A. Influence of brown coal on limit of phytotoxicity of soils contaminated with heavy metals. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 149, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubin, A.S.; Sukhanov, P.T.; Kushnir, A. Extraction of Phenols From Aqueous Solutions by Magnetic Sorbents Modified with Humic Acids. Mosc. Univ. Chem. Bull. 2019, 74, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, K.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, D.; Meng, X.; An, Q.; Chu, P.K. Removal of organic pollutants from super heavy oil wastewater by lignite activated coke. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2014, 447, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitkova, M.; Dercová, K.; Molnárová, J.; Tothova, L.; Polek, B.; Godočíková, J. The Effect of Lignite and Comamonas testosteroni on Pentachlorophenol Biodegradation and Soil Ecotoxicity. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2010, 218, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuske, M.; Karczewska, A.; Gałka, B.; Dradrach, A. Some adverse effects of soil amendment with organic Materials—The case of soils polluted by copper industry phytostabilized with red fescue. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2016, 18, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leszczyńska, D.; Kwiatkowska-Malina, J. Effect of organic matter from various sources on yield and quality of plant on soils contaminated with heavy metals. Ecol. Chem. Eng. S 2011, 18, 501–507. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, M.Z.U.; Rizwan, M.; Hussain, A.; Saqib, M.; Ali, S.; Sohail, M.I.; Shafiq, M.; Hafeez, F. Alleviation of cadmium (Cd) toxicity and minimizing its uptake in wheat (Triticum aestivum) by using organic carbon sources in Cd-spiked soil. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 241, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, M.Z.U.; Khalid, H.; Akmal, F.; Ali, S.; Rizwan, M.; Qayyum, M.F.; Iqbal, M.; Khalid, M.U.; Azhar, M. Effect of limestone, lignite and biochar applied alone and combined on cadmium uptake in wheat and rice under rotation in an effluent irrigated field. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 227, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, K.; Leskovar, D.I. Lignite-derived humic substances modulate pepper and soil-biota growth under water deficit stress. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2018, 181, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugier, D.; Kołodziej, B.; Bielińska, E. The effect of leonardite application on Arnica montana L. yielding and chosen chemical properties and enzymatic activity of the soil. J. Geochem. Explor. 2013, 129, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofrichter, M.; Fakoussa, R.M. Biodegradation and Modification of Coal. In Biopolymers Online; Steinbüchel, A., Ed.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fakoussa, R.M.; Hofrichter, M. Biotechnology and microbiology of coal degradation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1999, 52, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, N.J. Geology of Coal; Alderton, D., Elias, S.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 745–761. [Google Scholar]

- Ezeokoli, O.; Bezuidenhout, C.C.; Maboeta, M.S.; Khasa, D.P.; Adeleke, R.A. Structural and functional differentiation of bacterial communities in post-coal mining reclamation soils of South Africa: Bioindicators of soil ecosystem restoration. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, B.; Yuan, L.; Xue, S.; Liu, X.; Wu, Z.; Chen, J. Subsurface Microbial Invasion Affects the Microbial Community of Coal Seams. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 8023–8032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhart, E.P.; Weeks, E.P.; Jones, E.J.; Ritter, D.J.; McIntosh, J.C.; Clark, A.C.; Ruppert, L.F.; Cunningham, A.B.; Vinson, D.; Orem, W.; et al. Hydrogeochemistry and coal-associated bacterial populations from a methanogenic coal bed. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2016, 162, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhohola, L.; Igbinigie, E.E.; Cowan, A.K. Biological degradation and solubilisation of coal. Biodegradation 2013, 24, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, N.; Gómez, L.; Pantoja, M.; Ramírez, R. Production of humic substances through coal-solubilizing bacteria. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2014, 45, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanowska, I.; Strzelecki, B.; Bielecki, S. Biosolubilization of Polish brown coal by Gordonia alkanivorans S7 and Bacillus mycoides NS. Fuel Process. Technol. 2015, 131, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, M.T.; Patti, A.F.; Little, K.R.; Brown, A.L.; Jackson, W.R.; Cavagnaro, T.R. A Meta-Analysis and Review of Plant-Growth Response to Humic Substances. In Practical Implications for Agriculture; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; Volume 124, pp. 37–89. [Google Scholar]

- Senesi, N. The fractal approach to the study of humic substances. In Humic Substances in the Global Environment and Implications on Human Health; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 3–41. [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa, K.; Wang, B.; Nishiya, K.; Ushijima, K.; Zhu, Q.; Fukushima, M.; Ichijo, T. Effects of humic acids derived from lignite and cattle manure on antioxidant enzymatic activities of barley root. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2015, 51, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Venter, H.A.; Furter, M.; Dekker, J.; Cronje, I.J. Stimulation of seedling root growth by coal-derived sodium humate. Plant Soil 1991, 138, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impraim, R.; Weatherley, A.; Coates, T.; Chen, D.; Suter, H. Lignite Improved the Quality of Composted Manure and Mitigated Emissions of Ammonia and Greenhouse Gases during Forced Aeration Composting. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elena, A.; Diane, L.; Eva, B.; Marta, F.; Roberto, B.; Zamarreño, A.M.; García-Mina, J.M. The root application of a purified leonardite humic acid modifies the transcriptional regulation of the main physiological root responses to Fe deficiency in Fe-sufficient cucumber plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2009, 47, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, V.; Bacaicoa, E.; Zamarreño, A.-M.; Aguirre, E.; Garnica, M.; Fuentes, M.; García-Mina, J.-M. Action of humic acid on promotion of cucumber shoot growth involves nitrate-related changes associated with the root-to-shoot distribution of cytokinins, polyamines and mineral nutrients. J. Plant Physiol. 2010, 167, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verlinden, G.; Coussens, T.; De Vliegher, A.; Baert, G.; Haesaert, G. Effect of humic substances on nutrient uptake by herbage and on production and nutritive value of herbage from sown grass pastures. Grass Forage Sci. 2010, 65, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neswati, R.; Azizah, N.; Lopulisa, C.; Abdullah, S. Effect of Humic Subtances Produced from Lignite and Straw Compost on Phosphor Availability in Oxisols. Int. J. Soil Sci. 2017, 13, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- David, J.; Šmejkalová, D.; Hudecová, Š.; Zmeškal, O.; Von Wandruszka, R.; Gregor, T.; Kučerík, J. The physico-chemical properties and biostimulative activities of humic substances regenerated from lignite. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlčková, Z.; Grasset, L.; Antošová, B.; Pekař, M.; Kučerík, J. Lignite pre-treatment and its effect on bio-stimulative properties of respective lignite humic acids. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 1894–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomhataikool, B.; Faungnawakij, K.; Kuboon, S.; Kraithong, W.; Chutipaichit, S.; Fuji, M.; Eiad-Ua, A. Effect of humic acid extracted from Thailand’s leonardite on rice growth. J. Met. Mater. Miner. 2019, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Hou, S.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, D.; Gao, B.; Wan, Y.; Li, Y.C.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xie, J. Activation of Humic Acid in Lignite Using Molybdate-Phosphorus Hierarchical Hollow Nanosphere Catalyst Oxidation: Molecular Characterization and Rice Seed Germination-Promoting Performances. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 13620–13631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandakumar, R.; Saravanan, A.; Singaram, P.; Chandrasekaran, B. Effect of lignite humic acid on soil nutrient availability at different growth stages of rice grown on Vertisols and Alfisols. Acta Agron. Hung. 2004, 52, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsetsegmaa, G.; Akhmadi, K.; Cho, W.; Lee, S.; Chandra, R.; Jeong, C.E.; Chia, R.W.; Kang, H. Effects of Oxidized Brown Coal Humic Acid Fertilizer on the Relative Height Growth Rate of Three Tree Species. Forests 2018, 9, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahiri, A.; Destain, J.; Thonart, P.; Druart, P. In vitro model to study the biological properties of humic fractions from landfill leachate and leonardite during root elongation of Alnus glutinosa L. Gaertn and Betula pendula Roth. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2015, 122, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, J.R.; Dainello, F.J.; Haby, V.A.; Earhart, D.R. Evaluating Leonardite as a Crop Growth Enhancer for Turnip and Mustard Greens. HortTechnology 1998, 8, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, M.T.; Perkins, E.L.; Saha, B.K.; Tang, E.C.W.; Cavagnaro, T.R.; Jackson, W.R.; Hapgood, K.P.; Hoadley, A.F.A.; Patti, A.F. A slow release nitrogen fertiliser produced by simultaneous granulation and superheated steam drying of urea with brown coal. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2016, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schefe, C.R.; Patti, A.F.; Clune, T.; Jackson, W.R. Organic amendment addition enhances phosphate fertiliser uptake and wheat growth in an acid soil. Soil Res. 2008, 46, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.; Khurshid, M.; Khan, M.; Abbasi, M.; Kazmi, M. Lignite-Derived Humic Acid Effect on Growth of Wheat Plants in Different Soils. Pedosphere 2011, 21, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, S.; Pizzeghello, D.; Muscolo, A.; Vianello, A. Physiological effects of humic substances on higher plants. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 1527–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.Y.; Jeong, H.J.; Cha, J.-Y.; Choi, M.; Jang, K.-S.; Kim, W.-Y.; Kim, M.G.; Jeon, J.-R. Structural variation of humic-like substances and its impact on plant stimulation: Implication for structure-function relationship of soil organic matters. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 725, 138409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscolo, A.; Sidari, M.; Nardi, S. Humic substance: Relationship between structure and activity. Deeper information suggests univocal findings. J. Geochem. Explor. 2013, 129, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinton, R.; Cesco, S.; Varanini, Z. Role of Humic Substances in the Rhizosphere. In Biophysico-Chemical Processes Involving Natural Nonliving Organic Matter in Environmental Systems; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 341–366. [Google Scholar]

- Imbufe, A.U.; Patti, A.F.; Burrow, D.; Surapaneni, A.; Jackson, W.R.; Milner, A.D. Effects of potassium humate on aggregate stability of two soils from Victoria, Australia. Geoderma 2005, 125, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaetxea, M.; de Hita, D.; Garcia, C.A.; Fuentes, M.; Baigorri, R.; Mora, V.; Garnica, M.; Urrutia, O.; Erro, J.; Zamarreño, A.M.; et al. Hypothetical framework integrating the main mechanisms involved in the promoting action of rhizospheric humic substances on plant root- and shoot- growth. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 123, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billingham, K. Humic products: Potential or presumption for agriculture? In Proceedings of the 27th Annual Conference of the Grassland Society of NSW Inc., Orange, Australia, 24–26 July 2012; pp. 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ayuso, M.; Hernández, T.; García, C.; Pascual, J.A. A Comparative Study of the Effect on Barley Growth of Humic Substances Extracted from Municipal Wastes and from Traditional Organic Materials. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1996, 72, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.K.; Rose, M.; Wong, V.; Cavagnaro, T. Brown coal-urea blend for increasing nitrogen use efficiency and biomass yield. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Nitrogen Initiative Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 4–8 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Natesan, R.; Kandasamy, S.; Thiyageshwari, S.; Boopathy, P.M. Influence of lignite humic acid on the micronutrient availability and yield of blackgram in an alfisol. In Proceedings of the 18th World Congress of Soil Science, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 9–15 July 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Akinremi, O.O.; Janzen, H.H.; Lemke, R.L.; Larney, F.J. Response of canola, wheat and green beans to leonardite additions. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2000, 80, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.J.; Oh, M.S.; Rehman, J.U.; Yoon, H.Y.; Kim, J.-H.; Shin, J.; Shin, S.G.; Bae, H.; Jeon, J.-R. Effects of Microbes from Coal-Related Commercial Humic Substances on Hydroponic Crop Cultivation: A Microbiological View for Agronomical Use of Humic Substances. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccolo, A.; Celano, G.; Pietramellara, G. Effects of fractions of coal-derived humic substances on seed germination and growth of seedlings (Lactuga sativa and Lycopersicum esculentum). Biol. Fertil. Soils 1993, 16, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-Q.; Yuan, L.; Li, W.; Lin, Z.-A.; Li, Y.-T.; Hu, S.-W.; Zhao, B.-Q. Effects of urea enhanced with different weathered coal-derived humic acid components on maize yield and fate of fertilizer nitrogen. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 656–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.U.; Khan, M.Z.; Akhtar, M.E.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, A. Chemical Composition of Lignitic Humic Acid and Evaluating its Positive impacts on Nutrient Uptake, Growth and Yield of Maize. Pak. J. Chem. 2014, 4, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, C.; Şenbayram, M.; Akram, N.A.; Ashraf, M.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Ahmad, P. Sulfur-enriched leonardite and humic acid soil amendments enhance tolerance to drought and phosphorus deficiency stress in maize (Zea mays L.). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirn, A.; Kashif, S.R.; Yaseen, M. Using indigenous humic acid from lignite to increase growth and yield of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.). Soil Environ. 2010, 29, 187–191. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Escobar, R.; Benlloch, M.; Barranco, D.; Dueñas, A.; Gañán, J. Response of olive trees to foliar application of humic substances extracted from leonardite. Sci. Hortic. 1996, 66, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangeetha, M.; Singaram, P. Effect of lignite humic acid and inorganic fertilizers on growth and yield of onion. Asian J. Soil Sci. 2007, 2, 108–110. [Google Scholar]

- Sanli, A.; Karadogan, T.; Tonguc, M. Effects of leonardite applications on yield and some quality parameters of potatoes (So-lanum tuberosum L.). Turk. J. Field Crop. 2013, 18, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar, K.; Devarajan, L.; Dhanasekaran, K.; Venkatakrishnan, D.; Surendran, U. Effect of humic acid on the yield and nutrient uptake of rice. ORYZA Int. J. Rice 2007, 44, 277–279. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, D.; Singh, A.; Kumar, A. Nutrient uptake and yield of rice (Oryza sativa L.) as influenced by coalderived potassium humate and chemical fertilizers. ORYZA Int. J. Rice 2017, 54, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolcu, H.; Seker, H.; Gullap, M.; Lithourgidis, A.; Gunes, A. Application of cattle manure, zeolite and leonardite improves hay yield and quality of annual ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) under semiarid conditions. Aust. J. Crop. Sci. 2011, 5, 926–931. [Google Scholar]

- Dyśko, J.; Kaniszewski, S.; Kowalczyk, W. Lignite as a new medium in soilless cultivation of tomato. J. Elem. 2012, 20, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillem, S.; Schneider, B.U.; Zeihser, U.; Hüttl, R.F. Effect of N-modified lignite granulates and composted biochar on plant growth, nitrogen and water use efficiency of spring wheat. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2019, 65, 1913–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgay, O.C.; Karaca, A.; Unver, S.; Tamer, N. Effects of Coal- Derived Humic Substance on Some Soil Properties and Bread Wheat Yield. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2011, 42, 1050–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Ali, S.; Khan, K.S.; Hassan, F.U.; Bashir, K. Use of Coal Derived Humic Acid as Soil Conditioner to Improve Soil Physical Properties and Wheat Yield. Int. J. Plant Soil Sci. 2015, 5, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, S.; Ozkan, S.G. Investigation of Humate Extraction from Lignites. Int. J. Coal Prep. Util. 2017, 37, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedbagheri, M.M.; He, Z.; Olk, D.C. Yields of Potato and Alternative Crops Impacted by Humic Product Application BT. In Sustainable Potato Production: Global Case Studies; He, Z., Larkin, R., Honeycutt, W., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Adani, F.; Genevini, P.; Zaccheo, P.; Zocchi, G. The effect of commercial humic acid on tomato plant growth and mineral nutrition. J. Plant Nutr. 1998, 21, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaichelvi, K.; Chinnusamy, C.; Swaminathan, A.A. Exploiting the natural resource-lignite humic acid in agriculture: A review. Agric. Rev. 2006, 27, 276–283. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Liu, M.; Liang, R. Preparation and properties of a double-coated slow-release NPK compound fertilizer with superabsorbent and water-retention. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, M.; Wang, R.; Chen, B. Controlled release urea improved the nitrogen use efficiency, yield and quality of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) on silt loamy soil. Field Crop. Res. 2015, 181, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, S.; Delgado, J.; Mosier, A.; Miura, Y. Use of Controlled Release Fertilizers and Nitrification Inhibitors to Increase Nitrogen Use Efficiency and to Conserve Air Andwater Quality. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2001, 32, 1051–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbian, P.; Lal, R.; Subramanian, K.S. Cropping Systems Effects on Soil Quality in Semi-Arid Tropics. J. Sustain. Agric. 2000, 16, 7–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accoe, F.; Boeckx, P.; Busschaert, J.; Hofman, G.; Van Cleemput, O. Gross N transformation rates and net N mineralisation rates related to the C and N contents of soil organic matter fractions in grassland soils of different age. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2004, 36, 2075–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollmann, A.; Laanbroek, H.J. Continuous culture enrichments of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria at low ammonium concentrations. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2001, 37, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Bai, M.; Shen, J.; Griffith, D.W.; Denmead, O.T.; Hill, J.; Lam, S.K.; Mosier, A.R.; Chen, D. Effects of lignite application on ammonia and nitrous oxide emissions from cattle pens. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 565, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, W.; Hou, D.; Wang, H.; Sai, S.; Wang, B.; Ke, J.; Wu, G.; Li, Q.; Holtzapple, M. Preparation of Microcapsules of Slow-Release NPK Compound Fertilizer and the Release Characteristics. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2018, 29, 2397–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborda, F.; Fernández, M.; Luna, N.; Monistrol, I. Study of the mechanisms by which microorganisms solubilize and/or liquefy Spanish coals. Fuel Process. Technol. 1997, 52, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machnikowska, H.; Pawelec, K.; Podgórska, A. Microbial degradation of low rank coals. Fuel Process. Technol. 2002, 77–78, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokorný, R.; Olejníková, P.; Balog, M.; Zifčák, P.; Hölker, U.; Janssen, M.; Bend, J.; Höfer, M.; Holienčin, R.; Hudecová, D.; et al. Characterization of microorganisms isolated from lignite excavated from the Záhorie coal mine (southwestern Slovakia). Res. Microbiol. 2005, 156, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimbekov, N.; Digel, I.; Qiao, X.; Tastambek, K.; Zhubanova, A. Lignite Biosolubilization by Bacillus sp. RKB 2 and Characterization of its Products. Geomicrobiol. J. 2019, 37, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J. Bioenergy in the black. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2007, 5, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobartini, J.; Tan, K.; Rema, J.; Gingle, A.; Pape, C.; Himmelsbach, D. The geochemical nature and agricultural importance of commercial humic matter. Sci. Total Environ. 1992, 113, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.W.I.; Noack, A.G. Black carbon in soils and sediments: Analysis, distribution, implications, and current challenges. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2000, 14, 777–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Haumaier, L.; Guggenberger, G.; Zech, W. The ’Terra Preta’ phenomenon: A model for sustainable agriculture in the humid tropics. Naturwissenschaften 2001, 88, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, M.; Alburquerque, J.; Moral, R. Composting of animal manures and chemical criteria for compost maturity assessment. A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 5444–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.T.; Tang, J.L.; Ali, Z.; Yao, Z.; Bah, H.; Iqbal, H.; Ren, X. Ammonia Volatilization and Greenhouse Gases Emissions during Vermicomposting with Animal Manures and Biochar to Enhance Sustainability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 18, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Chang, C.; Larney, F.J.; Travis, G.R. Greenhouse Gas Emissions during Cattle Feedlot Manure Composting. J. Environ. Qual. 2001, 30, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Schmidt, S.; Qin, W.; Li, J.; Li, G.; Zhang, W. Towards the circular nitrogen economy—A global meta-analysis of composting technologies reveals much potential for mitigating nitrogen losses. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Sun, J.; Bai, M.; Dassanayake, K.B.; Denmead, O.T.; Hill, J. A new cost-effective method to mitigate ammonia loss from intensive cattle feedlots: Application of lignite. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Bai, M.; Han, B.; Impraim, R.; Butterly, C.; Hu, H.; He, J.; Chen, D. Enhanced nitrogen retention by lignite during poultry litter composting. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 122422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.; Impraim, R.; Coates, T.; Flesch, T.; Trouvé, R.; van Grinsven, H.; Cao, Y.; Hill, J.; Chen, D. Lignite effects on NH3, N2O, CO2 and CH4 emissions during composting of manure. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 271, 110960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgacakis, D.; Tsavdaris, A.; Bakouli, J.; Symeonidis, S. Composting solid swine manure and lignite mixtures with selected plant residues. Bioresour. Technol. 1996, 56, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteley, G.M.; Pettit, C. Effect of lignite humic acid treatment on the rate of decomposition of wheat straw. Biol. Fertil. Soils 1994, 17, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Hu, H.-W.; Guo, H.-G.; Butterly, C.; Bai, M.; Zhang, Y.-S.; Chen, D.; He, J.-Z. Lignite as additives accelerates the removal of antibiotic resistance genes during poultry litter composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 315, 123841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleber, M.; Lehmann, J. Humic Substances Extracted by Alkali Are Invalid Proxies for the Dynamics and Functions of Organic Matter in Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecosystems. J. Environ. Qual. 2019, 48, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, J.; Kleber, M. The contentious nature of soil organic matter. Nature 2015, 528, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amoah-Antwi, C.; Kwiatkowska-Malina, J.; Szara, E.; Thornton, S.; Fenton, O.; Malina, G. Efficacy of Woodchip Biochar and Brown Coal Waste as Stable Sorbents for Abatement of Bioavailable Cadmium, Lead and Zinc in Soil. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2020, 231, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król-Domańska, K.; Smolińska, B. Advantages of Lignite Addition in Purification Process of Soil Polluted by Heavy Metals; Lodz University of Technlology Press: Lodz, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Klučáková, M.; Pekař, M. Solubility and dissociation of lignitic humic acids in water suspension. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2005, 252, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doskočil, L.; Grasset, L.; Válková, D.; Pekař, M. Hydrogen peroxide oxidation of humic acids and lignite. Fuel 2014, 134, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binner, E.; Facun, J.; Chen, L.; Ninomiya, Y.; Li, C.-Z.; Bhattacharya, S. Effect of Coal Drying on the Behavior of Inorganic Species during Victorian Brown Coal Pyrolysis and Combustion. Energy Fuels 2011, 25, 2764–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domazetis, G.; Raoarun, M.; James, B.D. Low-Temperature Pyrolysis of Brown Coal and Brown Coal Containing Iron Hydroxyl Complexes. Energy Fuels 2006, 20, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).