Abstract

Background: Caregivers represent the core of patients’ care in hospital structures, in the process of care and self-care after discharge. We aim to identify the factors that affect the strain of caring for orthopedic patients and how these factors are related to the quality of life of caregivers. We also want to evaluate the role of caregivers in orthopedic disease, focusing attention on the patient–caregiver dyad. Methods: A comprehensive search on PubMed, Cochrane, CINAHL and Embase databases was conducted. This review was reported following PRISMA statement guidance. Studies were selected, according to inclusion and exclusion criteria, about patient–caregiver dyads. For quality assessment, we used the MINORS and the Cochrane Risk of BIAS assessment tool. Results: 28 studies were included in the systematic review; in these studies, 3034 dyads were analyzed. Caregivers were not always able to bear the difficulties of care. An improvement in strain was observed after behavioral interventions from health-care team members; Conclusions: The role of the caregiver can lead to a deterioration of physical, cognitive and mental conditions. The use of behavioral interventions increased quality of life, reducing the strain in caregivers of orthopedic patients. For this reason, it is important to consider the impact that orthopedic disease has on the strain of the caregiver and to address this topic.

Keywords:

caregiver; orthopedic disease; caregiver strain; hip; knee; shoulder; caregiver stress; dyads 1. Introduction

Orthopedic surgery is one of the most commonly performed surgeries worldwide [1,2]. Patients undergoing orthopedic surgery can experience difficulties in the management of post-surgical symptoms and physical limitations [3]. Orthopedic patients may experience barriers such as difficulties with Activities of Daily Living (ADL) [4,5], and problems returning to post-surgical lives. For these reasons, the role of the caregiver is of paramount importance in supporting dependent people both in simple and complex activities [6]. Although they are often family members without formal training, they take part in the activities of daily care, offering emotional support to the patients and replacing, in whole or in part, the physically dependent patients in the ADLs. Additionally, they monitor the patient’s care pathway, managing the symptoms and taking on the family responsibilities previously managed by the patients [7]. All these factors contribute to increasing the caregivers’ workload and they could affect caregivers’ quality of life, both pre to post the patients’ orthopedic surgeries [8]. The poor physical conditions of patients are associated with a decrease in the quality of life of the caregiver and an increase in stressors, due to all the caregivers’ responsibilities; the caregiver can also present physical problems due to the effort involved in helping the patient to move. It is therefore important to enhance the caregiver’s safety to improve his/her physical condition [9]. Caregiving is emotionally and cognitively demanding, and literature indicates that caregivers’ overall health is adversely altered [10].

The term “dyad” refers to the relationship between patient and caregiver, who are involved physically and emotionally. The dyad is an important foundation for problem identification and problem-solving included in the orthopedic patient process, from the pre-operative period to the post-operative period. Humor, reassurance, and empathy are also important factors in this dyad relationship. There is a need to enhance patient–caregiver dyad research, by studying the relationship from pre-operative to follow-up to evaluate the changes in the patient’s outcomes, but also in the caregiver’s psychological and cognitive sphere. There is a need to identify the type of supportive relationship that is established with informal caregivers to offer them an appropriate educational plan. Furthermore, it is necessary to evaluate if the degree of instruction received during the hospitalization period and the knowledge of informal caregivers about the disease, is sufficient for them to be able to face a functional recovery process in the postoperative period in order to maintain the role of caregiver after patients’ surgery [11].

The present systematic review aims to identify, analyze and synthesize the studies on the role of informal caregivers’ strain and difficulties when caring for orthopedic patients, focusing attention on the patient–caregiver dyad, during the pre-operative to post-operative period.

2. Materials and Methods

A literature review was performed and reported following PRISMA statement guidance [12]. Preliminary searches of main databases could not find any existing or ongoing systematic reviews on caregiver strain or difficulties of caring for orthopedic patients.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria and Search Strategy

Key words and combinations of key words were used to search the electronic databases and were organized according to the Population Intervention Comparison Outcome (PICO) model as follows.

Study: original studies with different study designs; English language; recent studies (from 2003 to 2020).

Participants: patient–caregiver dyads, orthopedic patients and informal caregivers.

Interventions: educational interventions, home-care rehabilitations, emotional and social supports.

Outcome measures: The primary outcome of the review is the caregivers’ role in the orthopedic patients’ functional recovery, the caregivers’ knowledge to manage orthopedic disease symptoms, the caregivers’ strain, and the dyads’ quality of life; the secondary outcome is the impact that orthopedic disorders have on quality of life, on stress level and on the psychological and physical status of patients.

A comprehensive search of the databases PubMed, Medline, Cochrane, CINAHL, and Embase databases was conducted since the inception of the database to March 2020 with the English language constraint. To ensure a comprehensive search, facet analysis, necessary to identify the key terms to be used in the search strategy, was carried out. Keywords were combined using the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR”. The search strategy was iterative and flexible within the limits of the search engines of the individual databases.

The following medical subject heading (MeSH) keywords and free terms were used for the search: caregiver, spouse, orthopedic disease, orthopedic, caregiver burden, hip, knee, shoulder, elbow, wrist, hand, humerus, femur, patella, spine, ankle, foot, caregiver stress, patient–caregiver dyads. Search strategies were checked by two reviewers (VC and GF). The exclusion criteria included: formal caregivers, reviews, books, patients and caregivers without a relation. Further details about search strategies are in Appendix A.

2.2. Study Selection and Data Collection

Two researchers (VAr and VAl) independently reviewed all studies (title, abstract and full text) that met the inclusion criteria and extracted relevant data. Disagreements were resolved by a discussion among the reviewers.

We included observational studies, prospective studies, cohort studies, mixed studies, pre–post quasi-experimental designs, randomized controlled trials, descriptive cross-sectional studies, prospective longitudinal cohort studies, non-randomized trials, qualitatively focused ethnographic approaches and retrospective analyses. The studies included articles published from 2003 to 2020. Disagreement regarding the exclusion and inclusion criteria were decided by the senior reviewer (VD).

2.3. Quality Assessment

Two reviewers independently evaluated (VAr/VAl) the potential risk of bias of the studies included using MINORS [13], a methodological index for non-randomized studies, and the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool [14] for randomized controlled trials.

The MINORS items were scored as 0 if not reported, 1 when reported but inadequate, 2 when reported and adequate. The global ideal score was 16 for non-comparative studies and 24 for comparative studies.

The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool assessed randomized controlled trials with the following criteria: selection, performance, detection, attrition, reporting and other biases. Each criterion was evaluated assigning zero for low risk, one point for unclear risk, and two points for high risk of bias. The potential total score range was 0–14, in which a low score indicated a higher quality level, and a high score indicated lower quality. Based on this score, an overall score of 0–1 shows high quality, an overall score of 2–3 shows moderate quality, and an overall score of >3 shows low quality [15].

2.4. Data Synthesis and Analysis

Data were extracted and synthesized through Microsoft Excel. Several data were extracted, and they concern outcome measures; authors and year; study design; orthopedic disease; aim of each study follow-up period; the relationship between patient and caregiver; number of patients and caregivers for each study; data findings; and study conclusion.

Data analysis was done using the description of the study and patient and intervention characteristics. Categorical variable data were reported as percentage frequencies. Continuous variable data were reported as mean values, with the range between the minimum and maximum values.

3. Results

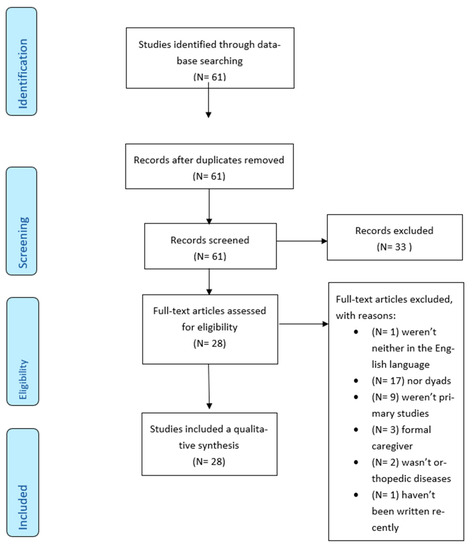

The selection process is illustrated in Figure 1. The search strategy yielded 61 articles. After duplicate removal and title, abstract and full texts review, 28 studies were evaluated for methodological quality and were eligible for the review.

Figure 1.

Study selection process and screening according to the PRISMA flow chart [12].

3.1. Study and Patient Characteristics

A total of 3034 patients–caregiver dyads were reviewed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies: author and country; number of patients; number of caregivers; outcome measures; follow-up; data findings; conclusion; relationship with the patients.

According to the aim of the review, the studies included analyzed the patient–caregiver dyad in the orthopedic disease context. It was found that the majority of the studies included (75%) analyzed dyad characteristics in hip disease (hip fracture, hip arthroplasty, hip deformity). To a lesser extent, 11% of the studies considered patients affected by knee orthopedic disease (knee fracture, knee arthroplasty, patella fracture) and 14.3% with backbone conditions (spinal arthrodesis, scoliosis, spine deformity, and cord injury) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of orthopedic diseases in included studies.

The topics of the studies included in the systematic review make it possible to evaluate the caregiver’s role in the orthopedic patients’ functional recovery, dealing with knowledge to manage symptoms and orthopedic disease in 8 studies, caregiver strain in 15 studies and dyads’ quality of life in 5 studies.

In the studies evaluating the quality of life of the dyad, 7.14% of the studies affirmed that the patient’s quality of life was improved due to the assistance provided by the informal caregiver. Despite the improvement in patients’ quality of life, their quality of functional recovery does not improve, and the 14.2% of studies state that it is influenced by caregivers’ psychological factors.

Regarding the caregivers’ quality of life, 7.14% of the studies say the decrease in caregivers’ quality of life is related to the increasing intensity of care and caregiver strain [14].

The studies analyzing caregiver strain report that the factors affecting caregiver difficulties are increased recovery time (21.4%), complication and symptom management (14.2%), financial resources (10.7%), functional level reduction (10.7%), bad healthcare experiences (7%), any trusting relationships (7%), patients’ and caregivers’ age (7%), poor social support (7%), poor self-efficacy (7%), transport (3.5%), and rural environment (3.5%). Two studies identified a significant correlation between caregiver strain and caregiver characteristics such as age [16,17] and gender [17].

The studies included in the review used some different follow-up periods: the pre-operative period (12.5%) and 2 weeks (4.6%), 1 month (18.2%), 3 months (20.4%), 6 months (23.3%), and 1 year (21%) after surgery. The follow-up period analysis was useful for analyzing the caregivers’ strain duration. In studies that analyzed the duration of caregiver strain, fourteen percent of studies reported that caregiver strain lasted for one year, 10.7% for six months, 7.1% for one month and 3.5% for two years.

Regarding the studies that analyzed knowledge to manage symptoms, they reported that pre-operative education was fundamental to improve the management of symptoms. Pre-operative education and postoperative social support reduced caregiver strain in 46.5% of studies.

To understand the relationship between the informal caregivers and the patients that form the dyads, studies reported that the major of informal caregivers were patients’ relatives. The most common relationships between the primary caregiver and the care recipient in this review included spouses (22.1%), daughters (8.7%), sons (6.7%), daughters-in-law (5.2%), and others, including partners, mothers, grandchildren and siblings (9.2%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Caregivers’ demographic characteristics (relationship with patients).

3.2. Intervention Characteristics

The most common outcome measures observed in original studies according with the aim of this review were Caregiver Strain Index (CSI), utilized in 32% of the studies recruited [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]; Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI), in 7.14% [26,27]; Mini-Mental Test (M-MT) in 7.14% [22,27]; and Health-Related Quality of Life score (HRQL) in 14.2% of the studies [27,28,29,30].

Participants’ knowledge of the intervention and post-surgical management was tested via Knowledge Expectations of significant others (KEso) and Received Knowledge of significant others (RKso) [16]; confusion assessment method (CAM) and family version (FAM-CAM) [7] were used to measure empowering by knowledge.

Measures for general health status included the Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) [18,22,31,32], the Functional Independence Measure Score (FIM) [27]; the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) [27]; Time Up and Go Test (TUG) [18,19,27]; International Fitness Scale (FIS) [27]; The University of California, Los Angeles Activity Scale (UCLA) [29]; The Blaylock Risk Assessment Screening Score (BRASS) [37]; and the italics Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE) [21,26].

ADLs for patients and caregivers were assessed using the Barthel index [18,22,32]; the Reintegration to Normal Living Index (RNLI) [20]; and the Family Function Rating Scale [21]. The Visual Analogue Scale for Pain (VAS) [27,33] was the scale most often used to evaluate symptoms, as well as depression scales [24,27].

3.3. Quality Assessment

Most of studies included in this review (N = 27; 96.4%) were evaluated with MINORS. Of these, one study (3.57%) had low risk of bias and 26 (92.8%) had high risk of bias. The only RCT (Crotty, 2003) in this review had moderate quality due to insufficient details about the double-blinding procedure.

4. Discussion

This review aimed to synthesize the studies on the role of informal caregiver strain and difficulties when caring for orthopedic patients, focusing attention on the patient–caregiver dyad, from the pre-operative period to the post-operative period. Family caregivers are a relatively unused resource as a way to identify early symptoms and complications in orthopedic patients and to improve health outcomes for orthopedic patients. When pre-operative education is performed, family caregivers can apply their knowledge by acting on early recognition of symptoms [3,7].

Learning about diseases drives caregivers to satisfaction and to learn strategies to help patients, also with emotional support. Extensive efforts have been made to understand the strain felt by caregivers of patients with orthopedic disease. Orthopedic caregivers without enough information had less security in dealing with the patients’ disease than those who received an appropriate education from health care team members: this is a finding that was consistent with the stress and coping model of caregiving [29].

Caregiving and poor quality of life can relate bidirectionally. In the dyad, concerns are about mobility, pain, self-care, support from the caregiver and discharge on the same day regarding recovery expectations, and drugs and their effect on postoperative recovery [34]. Orthopedic patients feel more pain and greater difficulties with physical activity; this leads to an increase in the caregiver’s workload, and several studies underestimate this result [35]. The impact of the orthopedic disease on dyads is crucial for patients’ outcomes and caregiver strain. The physical outcomes of patients and their functional recovery, and also the impact of caregiver assistance on care transition, have been studied more frequently [36].

In this context, the formal rehabilitation program has a key role in restoring patient autonomy and also involving the caregiver to reduce and improve rehabilitation times [38,39]. When the patients’ formal post-surgery rehabilitation program is insufficient, the supply of a family caregiver is fundamental. For example, it could be necessary to improve the information and caregivers’ education about the management of symptoms. A focus on the orthopedic patient and caregiver education regarding the clinical post-operative problems, potential risks involved, and patient and caregiver roles to improve the caring process is necessary.

In many of the studies recruited, caregiver strain is one of the main topics. The difficulty of assistance is often not recognized, and it can lead to mental and physical problems, but can also have a strong impact on social life [35]. Caregiver stress increases in the immediate postoperative period, while decreasing a lot after a year after surgery [25]. Especially in patients undergoing hip replacement, the caregiver strain is very high, which is why it is important to ease caregiver stress and increase the quality of care throughout the functional recovery period, including the periodic follow-up [24]. In most of the studies analyzed, the follow-up period of the dyad is approximately one year. This means that it cannot be said that the interventions implemented on the dyad provide long-term benefits and that the outcomes are valid.

Concerning the strain of care [30], we have found that caregivers showed disorders in the cognitive and physical spheres of their daily lives during the treatment period, from the pre-operative to post-operative period, leading to a reduction in their quality of life.

This review showed the importance of information and education before and after orthopedic surgery, to limit the functional restriction of patients by scared caregivers and to analyze its influence on functional recovery. The patient’s functional level, quality of life, physical performance, pain, caregiver strain, and their the emotional and cognitive state should be evaluated, and perception of physical state should be assessed [40]. A study conducted in 2010 aimed to investigate the causes of stress attributed to the caregivers of patients with orthopedic disease [23]. The caregiver tension can result from changes in the patient’s physical and cognitive states, and the sustained role during the patient’s daily life activities. Several factors can contribute to caregiver stress, including financial strain, which is one of the most significant causes of caregiver stress. The financial problems arise from the need to incur medical expenses, rehabilitation, and transportation. This can be added to the physical and mental stress of the caregiver.

Post-operative recovery of patients was associated with the mental state of their family members. When a caregiver’s mental state is “poor”, the patient is more likely to relapse, which could lead a prolongation of recovery. Agreeing with this hypothesis, it is recommended to consider the mental well-being of the informal carers by evaluating patient recovery time [22].

The patient–caregiver dyad has also been studied in the traumatological and chronic fields. It has been well documented in hip injuries, while less attention is paid to other orthopedic conditions. Quantitatively, 19 studies deal with hip fractures, four studies deal with knee injuries, five studies with spine injuries, and two studies with general orthopedic pathologies. All revised studies refer to the caregiver strain and the amount of care for the patient with the orthopedic condition, which will reduce the quality of life of the caregiver due to the resulting growing stress. Many studies focus on patient outcomes related to care by a caregiver. The aim is to improve care but also to reduce the strain and stress factors attributable to this type of relationship established with the patient.

The present results should be interpreted in the context of the strengths and weaknesses of the studies composing the orthopedic caregiver. For example, most studies of orthopedic caregivers have used self-report questionnaires rather than assess the level of quality of life or have used rating scales that emphasize increasing caregiver strain.

Self-reported quality of life was greater than objective measures of quality of life, so it is possible that the actual caregivers’ stress level was even worse than that estimated by the present systematic review. Repeating objective measures for all the caregivers would yield more accurate estimates of the real caregiver strain when caring for orthopedic patients.

Caregivers could be important to patients’ healthcare, particularly according to the duration of caregiving, workload and stress level: these are also the factors that increase caregiver difficulties. Patients demonstrated the greatest increase in quality of recovery thanks to communication with their caregiver and thanks to the help they received from caregivers in maintaining social interaction. Besides, caregivers could improve orthopedic patients’ life with behavioral interventions such as emotional comfort and support, both during pre-operative and post-operative periods.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. Further research is needed to examine how the intervention described would be successful with a larger sample. The study lacked a control group: future research is needed using a design that randomly assigns participants to intervention and control groups. Despite these limitations, the interventions were successful in increasing knowledge of caregivers’ importance in orthopedic disease.

5. Conclusions

Despite the challenges in studying the role of caregivers in orthopedic diseases and family caregiver strain and challenges when caring for orthopedic patients, the literature indicates that not only the increase in caregivers’ stress levels but also the decrease in quality of life was less severe in caregivers who received appropriate behavioral interventions including health care advice, such as medication advice or psychological tips. To improve the quality of health care, stressors should be considered for caregivers due to the high strain, especially in the post-discharge period.

Clinicians should consider the importance of caregiver interventions, not only for the orthopedic patient but also for the spouse, child, or friend who will be providing care for that individual. Further studies should focus on the important physical and mental role of the informal caregiver for patients who receive orthopedic surgery and the importance of psychological sphere for the patient–caregiver dyad. Focusing on caregivers’ welfare rather than only on patient well-being could radically improve both caregivers’ performance and patients’ recovery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and U.G.L.; methodology, V.A. (Valeria Arcangeli); software, V.A. (Viviana Alciati); validation, V.C., and M.M.; formal analysis, G.F.; investigation, A.M.; resources, M.G.D.M.; data curation, V.C.; writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, A.M.; visualization, M.M.; supervision, V.D.; project administration, U.G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. List of Search Terms Used for Systematic Review

Search terms for Medline Complete (via EBSCO Host): 1971 to 27 January 2019

- MH “Chronic Disease”

- chronic disease*

- chronic illness*

- chronically Ill

- 1 or 2 or 3 or 4

- MH “Aged+”

- Aged

- Elderly

- older adults

- 6 or 7 or 8 or 9

- MH “Continuity of Patient Care+”

- continuity of patient care

- patient care continuity

- continuum of care

- continuity of care

- care continuity

- 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16

- MH “Patient Readmission”

- re-admission*

- readmission*

- patient readmission*

- hospital readmission*

- post discharge*

- postdischarge*

- re-hospitalization

- rehospitalization

- re-admit*

- 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27

- 5 and 10 and 17 and 28

269. records found

Search terms for PubMed: 1971 to 27 January 2019

- Chronic Disease [Mesh]

- chronic disease*

- chronic illness*

- chronically ill

- 1 or 2 or 3 or 4

- Aged [Mesh]

- aged

- elderly

- older adult

- 6 or 7 or 8 or 9

- Continuity of Patient Care”[Mesh]

- patient care continuity

- continuum of care

- care continuity

- 11 or 12 or 13 or 14

- Patient Readmission”[Mesh]

- re-admission*

- readmission*

- patient readmission*

- hospital readmission*

- post discharge*

- postdischarge*

- re-hospitalization

- rehospitalization

- re-admit*

- readmit*

- 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26

- 5 and 10 and 15 and 27

233. records found

Search terms for CINHAL (via EBSCO Host): 1995 to 27 January 2019

- MH “Chronic Disease”

- chronic disease*

- chronic illness*

- chronically Ill

- 1 or 2 or 3 or 4

- MH “Aged”

- aged

- older adult*

- 6 or 7 or 8 or 9

- MH “Continuity of Patient Care”

- patient care continuity

- continuum of care

- continuity of care

- care continuity

- 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14

- MH “Readmission”

- re-admission*

- readmission*

- patient readmission*

- hospital readmission*

- post discharge*

- postdischarge*

- re-hospitalization

- rehospitalization

- re-admit*

- readmit*

- 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26

- 5 and 9 and 15 and 27

169. records found

Search terms for Embase: 1971 to 27 January 2019

- ‘chronic disease’/exp

- ‘chronic disease’

- ‘chronic illness’/exp

- ‘chronic illness’

- 1 or 2 or 3 or 4

- AND ‘aged’/exp

- ‘aged’

- ‘aged patient’/exp

- ‘aged patient’

- ‘aged people’/exp

- ‘aged people’

- ‘aged person’/exp

- ‘aged person’

- ‘aged subject’/exp

- ‘aged subject’

- ‘elderly’/exp

- ‘elderly’

- ‘elderly patient’/exp

- ‘elderly patient’

- ‘elderly people’/exp

- ‘elderly people’

- ‘elderly person’/exp

- ‘elderly person’

- ‘elderly subject’/exp

- ‘elderly subject’

- ‘senior citizen’/exp

- ‘senior citizen’

- ‘senium’/exp

- ‘senium’

- 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29

- ‘advance care planning’/exp

- ‘advance care planning’

- ‘care, continuity of’/exp

- ‘care, continuity of’

- ‘continuity of patient care’/exp

- ‘continuity of patient care’

- ‘episode of care’/exp

- ‘episode of care’

- ‘night care’/exp

- ‘night care’

- ‘patient care’/exp

- ‘patient care’

- ‘patient care management’/exp

- ‘patient care management’

- ‘patient care team’/exp

- ‘patient care team’

- ‘patient centered care’/exp

- ‘patient centered care’

- ‘patient helper’/exp

- ‘patient helper’

- ‘patient isolation’/exp

- ‘patient isolation’

- ‘patient management’/exp

- ‘patient management’

- ‘patient navigation’/exp

- ‘patient navigation’

- ‘patient-centered care’/exp

- ‘patient-centered care’

- ‘continuity of care’/exp

- ‘continuity of care’

- ‘continuum of care’

- ‘care continuity’

- 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 51 or 52 or 53 or 54 or 55 or 56 or 57 or 58 or 59 or 60 or 61 or 62

- ‘hospital readmission’/exp

- ‘hospital readmission’

- ‘patient readmission’/exp

- ‘patient readmission’

- ‘readmission’/exp

- ‘readmission’

- ‘readmission rate’/exp

- ‘readmission rate’

- ‘readmissions’/exp

- ‘readmissions’

- ‘rehospitalization’/exp

- ‘rehospitalization’

- ‘post discharge’

- 62 or 63 or 64 or 65 or 66 or 67 or 68 or 69 or 70 or 71 or 72 or 73 or 74

- 5 and 29 and 61 and 75

135. records found

References

- Longo, U.G.; Salvatore, G.; Rizzello, G.; Berton, A.; Ciuffreda, M.; Candela, V.; Denaro, V. The burden of rotator cuff surgery in Italy: A nationwide registry study. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2017, 137, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, G.; Longo, U.G.; Candela, V.; Berton, A.; Migliorini, F.; Petrillo, S.; Ambrogioni, L.R.; Denaro, V. Epidemiology of rotator cuff surgery in Italy: Regional variation in access to health care. Results from a 14-year nationwide registry. Musculoskelet. Surg. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odom-Forren, J.; Reed, D.B.; Rush, C. Postoperative Distress of Orthopedic Ambulatory Surgery Patients. AORN J. 2017, 105, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, F.; Ronga, M.; Longo, U.G.; Testa, V.; Capasso, G.; Maffulli, N. The 3-in-1 procedure for recurrent dislocation of the patella in skeletally immature children and adolescents. Am. J. Sports Med. 2009, 37, 1814–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, U.G.; Loppini, M.; Romeo, G.; Maffulli, N.; Denaro, V. Evidence-based surgical management of spondylolisthesis: Reduction or arthrodesis in situ. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2014, 96, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, J.; Bradford, A. Caregivers of Orthopedic Trauma Patients: Perspectives on Participating in Caregiver-Related Research. IRB 2014, 36, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, M.J.; Boaz, L.; Maadooliat, M.; Hagle, M.E.; Gettrust, L.; Greene, M.T.; Holmes, S.B.; Saczynski, J.S. Preparing Family Caregivers to Recognize Delirium Symptoms in Older Adults After Elective Hip or Knee Arthroplasty. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, e13–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malley, A.M.; Bourbonniere, M.; Naylor, M. A qualitative study of older adults’ and family caregivers’ perspectives regarding their preoperative care transitions. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 2953–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.Y.; Kim, S.C.; Lee, M.H.; Lee, Y.I. Comparison of shoulder and back muscle activation in caregivers according to various handle heights. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2013, 25, 1231–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Pinquart, M.; Sorensen, S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Aging 2003, 18, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.A.; Donaldson, J.; Drake, D.; Johnson, L.; van Servellen, G.; Reed, P.L.; Mulnard, R.A. Venous thromboembolism knowledge among older post-hip fracture patients and their caregivers. Geriatr. Nurs. 2014, 35, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slim, K.; Nini, E.; Forestier, D.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Panis, Y.; Chipponi, J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facchinetti, G.; D’Angelo, D.; Piredda, M.; Petitti, T.; Matarese, M.; Oliveti, A.; De Marinis, M.G. Continuity of care interventions for preventing hospital readmission of older people with chronic diseases: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 101, 103396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stark, A.J.; Salantera, S.; Sigurdardottir, A.K.; Valkeapaa, K.; Bachrach-Lindstrom, M. Spouse-related factors associated with quality of recovery of patients after hip or knee replacement—A Nordic perspective. Int. J. Orthop. Trauma Nurs. 2016, 23, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.C.; Chou, M.Y.; Liang, C.K.; Lin, Y.T.; Ku, Y.C.; Wang, R.H. Association of home care needs and functional recovery among community-dwelling elderly hip fracture patients. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2013, 57, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotty, M.; Whitehead, C.; Miller, M.; Gray, S. Patient and caregiver outcomes 12 months after home-based therapy for hip fracture: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2003, 84, 1237–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Vega, P.; Ortiz-Pina, M.; Kristensen, M.T.; Castellote-Caballero, Y.; Jimenez-Moleon, J.J. High perceived caregiver burden for relatives of patients following hip fracture surgery. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGilton, K.S.; Omar, A.; Stewart, S.S.; Chu, C.H.; Blodgett, M.B.; Bethell, J.; Davis, A.M. Factors That Influence the Reintegration to Normal Living for Older Adults 2 Years Post Hip Fracture. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2019, 733464819885718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.C.; Lu, C.M. Psychosocial factors affecting hip fracture elder’s burden of care in Taiwan. Orthop. Nurs. 2007, 26, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.Y.; Yang, C.T.; Cheng, H.S.; Wu, C.C.; Chen, C.Y.; Shyu, Y.I. Family caregivers’ mental health is associated with postoperative recovery of elderly patients with hip fracture: A sample in Taiwan. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 78, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, M.Q.; Sim, L.; Koh, J.; Fook-Chong, S.; Tan, C.; Howe, T.S. Stress levels amongst caregivers of patients with osteoporotic hip fractures—A prospective cohort study. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2010, 39, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Parry, J.A.; Langford, J.R.; Koval, K.J. Caregivers of hip fracture patients: The forgotten victims? Injury 2019, 50, 2259–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zadzilka, J.D.; Klika, A.K.; Calvo, C.; Suarez, J.C.; Patel, P.D.; Krebs, V.E.; Barsoum, W.K.; Higuera, C.A. Caregiver Burden for Patients With Severe Osteoarthritis Significantly Decreases by One Year After Total Knee Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, 3660–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Miao, J.; Gao, X.; Zheng, L.; Su, X.; Hui, H.; Hu, J. Factors Associated with Caregiver Burden in Primary Caregivers of Patients with Adolescent Scoliosis: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 6472–6479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Pina, M.; Salas-Farina, Z.; Mora-Traverso, M.; Martin-Martin, L.; Galiano-Castillo, N.; Garcia-Montes, I.; Cantarero-Villanueva, I.; Fernandez-Lao, C.; Arroyo-Morales, M.; Mesa-Ruiz, A.; et al. A home-based tele-rehabilitation protocol for patients with hip fracture called @ctivehip. Res. Nurs. Health 2019, 42, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Sullivan, B.T.; Shah, S.A.; Samdani, A.F.; Yaszay, B.; Marks, M.C.; Sponseller, P.D. Caregiver Perceptions and Health-Related Quality-of-Life Changes in Cerebral Palsy Patients After Spinal Arthrodesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2018, 43, 1052–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwachukwu, B.U.; So, C.; Zhang, Y.; Shubin-Stein, B.E.; Strickland, S.M.; Green, D.W.; Dodwell, E.R. Adolescent and Caregiver-derived Utilities for Traumatic Patella Dislocation Health States. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2019, 39, e755–e760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Ree, C.L.P.; Ploegsma, K.; Kanters, T.A.; Roukema, J.A.; De Jongh, M.A.C.; Gosens, T. Care-related Quality of Life of informal caregivers of the elderly after a hip fracture. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2017, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimzadeh, M.H.; Shojaei, B.S.; Golhasani-Keshtan, F.; Soltani-Moghaddas, S.H.; Fattahi, A.S.; Mazloumi, S.M. Quality of life and the related factors in spouses of veterans with chronic spinal cord injury. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shyu, Y.I.; Chen, M.C.; Liang, J.; Tseng, M.Y. Trends in health outcomes for family caregivers of hip-fractured elders during the first 12 months after discharge. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Hu, F.; Liu, F.; Tong, P. Functional Restriction for the Fear of Falling In Family Caregivers. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015, 94, e1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churchill, L.; Pollock, M.; Lebedeva, Y.; Pasic, N.; Bryant, D.; Howard, J.; Lanting, B.; Laliberte Rudman, D. Optimizing outpatient total hip arthroplasty: Perspectives of key stakeholders. Can. J. Surg. 2018, 61, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohar, A.; Cheung, K.; Wu, C.L.; Stierer, T.S. Burden incurred by patients and their caregivers after outpatient surgery: A prospective observational study. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2014, 472, 1416–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscan, J.; Mairs, K.; Hinton, S.; Stolee, P.; InfoRehab Research, T. Integrated transitional care: Patient, informal caregiver and health care provider perspectives on care transitions for older persons with hip fracture. Int. J. Integr. Care 2012, 12, e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elli, S.; Contro, D.; Castaldi, S.; Fornili, M.; Ardoino, I.; Caserta, A.V.; Panella, L. Caregivers’ misperception of the severity of hip fractures. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2018, 12, 1889–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.A.; Sherrington, C.; Guaraldo, A.; Moraes, S.A.; Varanda, R.D.; Melo, J.A.; Kojima, K.E.; Perracini, M. Effectiveness of a physical exercise intervention program in improving functional mobility in older adults after hip fracture in later stage rehabilitation: Protocol of a randomized clinical trial (REATIVE Study). BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, U.G.; Facchinetti, G.; Marchetti, A.; Candela, V.; Risi Ambrogioni, L.; Faldetta, A.; De Marinis, M.G.; Denaro, V. Sleep Disturbance and Rotator Cuff Tears: A Systematic Review. Medicina (Kaunas) 2019, 55, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, U.G.; Risi Ambrogioni, L.; Berton, A.; Candela, V.; Carnevale, A.; Schena, E.; Gugliemelli, E.; Denaro, V. Physical therapy and precision rehabilitation in shoulder rotator cuff disease. Int. Orthop. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).