Abstract

Juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) is a rare, idiopathic autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation of both muscle and skin, with a significant contribution from the interferon (IFN) pathway in its pathogenesis. Here, we present the case of a 4-year-old boy with JDM who tested positive for Mi2-α and MDA5 antibodies and showed combined muscle and skin involvement. In view of his markedly elevated IFN signature, the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor baricitinib was introduced very early as a targeted steroid-sparing agent in addition to standard immunosuppressive therapy. The patient experienced marked clinical improvement, with resolution of skin lesions, normalization of MDA5 antibodies, and a pronounced reduction in the IFN signature. This case highlights the potential efficacy of JAK inhibition in managing JDM with a high IFN signature and supports a mechanism-based, interferon-targeted treatment approach, in line with emerging evidence in refractory JDM. Further studies are warranted to define the role of JAK inhibitors in the treatment of JDM.

1. Introduction

Juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) is a rare, idiopathic autoimmune condition characterized by inflammation of muscles and skin, which can lead to significant morbidity and, in severe instances, mortality [1]. Although the exact cause of JDM remains unknown, it is generally assumed that genetic predisposition, in combination with environmental triggers, initiates the autoimmune response [2]. Gene expression studies in both adult and juvenile dermatomyositis (DM and JDM) have consistently shown upregulation of interferon (IFN)-regulated genes, indicating that the IFN pathway plays a central role in the disease development [3,4,5]. In particular, high expression of type I and type II IFN-inducible genes in the myocytes of DM patients has been linked to increased inflammation and tissue repair mechanisms [4]. The strong association between IFN signaling and disease activity in DM, along with the crucial involvement of Janus kinases (JAKs) in IFN signal transduction, suggests that targeting the JAK-STAT pathway may represent a promising therapeutic strategy [6].

Janus kinase inhibitors exert their immunomodulatory effects by blocking intracellular signaling downstream of multiple cytokine receptors, particularly those involved in type I interferon signaling. Binding of type I interferons to their receptors activates JAK1 and TYK2, leading to phosphorylation of STAT proteins and induction of interferon-stimulated genes [7]. In dermatomyositis, persistent activation of this pathway results in a prominent type I interferon gene signature and contributes to chronic inflammation and tissue damage. By inhibiting JAK activity, JAK inhibitors suppress interferon-driven inflammatory signaling. This mechanism is especially relevant in anti-MDA5–associated disease, which is characterized by a strong type I interferon signature and severe systemic manifestations, including interstitial lung disease [8].

In JDM, the presence of specific autoantibodies is associated with distinct clinical phenotypes. Notably, MDA5 antibodies are correlated with a higher risk of skin ulcers, arthritis, and interstitial lung disease (ILD), often in the context of a predominantly amyopathic or hypomyopathic disease course [8]. ILD related to MDA5 antibodies is particularly concerning due to its treatment resistance and high mortality [9]. In such cases, conventional treatments may be ineffective, requiring additional therapies such as rituximab, TNF-alpha inhibitors, or cyclophosphamide [10,11,12]. Given the crucial role of the JAK-STAT pathway in JDM pathophysiology, JAK inhibitors have emerged as a promising therapeutic option [13,14]. Although several case reports have described the effectiveness of JAK inhibitors in refractory JDM, the current evidence remains limited, and further studies are needed to confirm these observations.

This case report describes the successful use of JAK inhibition in a 4-year-old boy with positive Mi2-alpha and MDA5 antibodies, presenting with both muscle and skin involvement.

2. Case Report

A previously healthy 4-year-old boy was admitted to the hospital, presenting with a history of heliotrope rash, bilateral eyelid edema, and vesicular lesions primarily localized to the oral cavity. Over time, the symptoms progressed, leading to the development of crusted lesions on the hands, feet, nose, and ears (Figure 1). Over the subsequent weeks his condition deteriorated.

Figure 1.

(A): Patchy, pale erythema on both cheeks and chin. (B): Peeling and erythema on the palmar sides and flexor surfaces of the hands. (C): Periungual erythema, thickening of the nail fold, and early-stage Gottron papules on the extensor surfaces of the fingers. (D): Livid macula with superimposed scaly plaque over ulceration on the right foot.

His mother reported progressive fatigue and lethargy, accompanied by knee and ankle pain that led to refusal to walk. Additionally, he had complained of abdominal pain during the summer months, which prompted a trial of a lactose-free diet, which did not alleviate his symptoms.

On examination, there was marked muscle pain and weakness, symmetrically affecting both the upper and lower limbs, including the wrist extensors, neck flexors, gluteal muscles, and hip flexors. Skin findings included Gottron’s papules on the extensor surfaces of the fingers, knees, and elbows, as well as nodules suggestive of vasculitis in acral areas. Inflammatory changes were also observed in the skin and subcutaneous tissue, together with hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy, but there was no pulmonary involvement. Baseline MMT was 69/80, CMAS 33/52. Nailfold capillaroscopy was performed but inconclusive due to shallow nail fold.

Laboratory investigations detected Mi2-α and MDA-5 antibodies. semi-quantitative measurements of autoantybodies were performed with detection of Mi2 (Elisa), Mi2-α (immunoblot), MDA-5 (immunoblot). Muscle enzymes, including creatine kinase or aldolase were within normal range, with no leucocytosis and no elevated CRP or ESR.

The skin biopsy showed a discrete interface reaction with increased plasmacytoid dendritic cells and discrete dermal toluidine deposits.

Although the patient had anti-MDA5 antibodies, which raised concerns for potential pulmonary complications, pulmonary involvement was carefully excluded. Imaging studies included chest X-ray and whole-body magnetic resonance imaging with pulmonary sequences; no pathological findings were detected. In addition, pulmonary function tests, including diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), were within normal limits at diagnosis and remained normal during follow-up. No clinical or radiological signs of interstitial lung disease were observed.

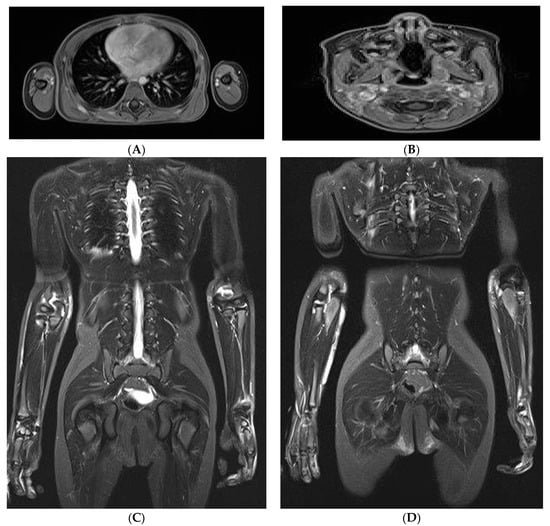

MRI imaging revealed multiple muscular edemas and contrast enhancement consistent with myositis, with a maximum intensity bilaterally in the gluteus maximus muscles, to a lesser extent also in the adductor muscles, adjacent to the scapula (Figure 2A), and on the right side of the cervical region (Figure 2B). Synovitis of the elbow joints (Figure 2C), hands, knees, and ankles, the latter also showing tenosynovitis. Multiple cutaneous and subcutaneous edematous and contrast-enhancing inflammatory changes with maximum intensity in the forearms (Figure 2D) and gluteal regions. Additional smaller foci are noted, for example, along the left proximal anterior tibial margin and in the cervical region.

Figure 2.

Whole-body MRI imaging: multiple muscular edemas and contrast enhancement consistent with myositis, adjacent to the scapula (A), cervical region (B), arthritis of elbow, hand (C), and multiple cutaneous and subcutaneous edematous and contrast-enhancing inflammatory changes with maximum intensity in the forearms (D). Images courtesy of the Department of Pediatric Radiology, University hospital Tuebingen.

Clinical and radiological findings, along with auto-antibodies and conclusive histopathological findings confirmed the diagnosis of JDM.

Standard therapies with IVIG (2 g/kg), one cycle of methylprednisolone pulse steroids (30 mg/kg), and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg every other day were initiated while awaiting the interferon-signaling results. The interferon signature was measured by assessing the expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). The following six ISGs were analyzed: IFI27, IFI44, IFI44L, IFIT1, ISG15, RSAD2, and SIGLEC1.

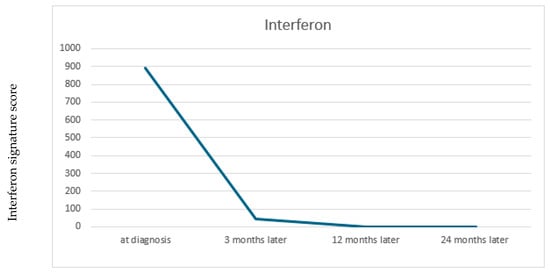

Gene expression was normalized to GAPDH and compared to the mean expression of 10 healthy controls. Quantitative RT-PCR (TaqMan) was used for analysis, and results were expressed as mean fold change (relative mRNA expression) ± SEM from at least three measurements. Interferon signature was highly elevated (892.89, Ref. range: <12.49), (Figure 3). which led us to explore treatment options targeting the interferon pathway. Methotrexate was not introduced, as baricitinib was selected early on as the primary steroid-sparing agent in addition to corticosteroids, IVIG, and hydroxychloroquine. Off-label JAK inhibitor treatment with Baricitinib (2 mg/day, adapted to body weight), was introduced after 6 weeks after initial admission to target interferon signaling, particularly in the context of MDA5 antibodies [13]. No further steroids were administered from then on.

Figure 3.

IFN signature score elevation and improvement. The patient had a highly elevated interferon (IFN) signature (score: 892.89; reference range: <12.49). Expression of six interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) was analyzed: IFI27, IFI44, IFI44L, IFIT1, ISG15, RSAD2, and SIGLEC1. The IFN signature markedly improved and became negative one year after diagnosis.

Baricitinib was selected over other JAK inhibitors based on its JAK1/JAK2 inhibition profile, its relevance in interferon-mediated diseases, and our center’s prior clinical experience with baricitinib in other pediatric rheumatologic conditions, particularly polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, where it has demonstrated good tolerability and manageable safety in routine clinical practice.

Treatment duration was guided by sustained clinical response and laboratory improvement, with therapy continued under close clinical and laboratory monitoring in the absence of established discontinuation algorithms.

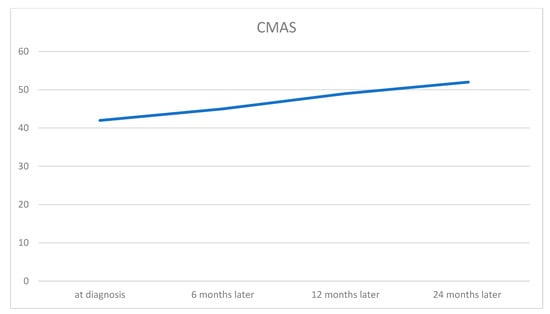

The patient experienced substantial clinical improvement on Baricitinib treatment, remaining on a stable dose of 2 mg. His CMAS score increased significantly from 42/52 upon admission to 52/52 after 24 months (Figure 4), while MDA5 antibodies and IFN signature were no longer detectable. Over time, the skin lesions healed, with complete resolution of ulcerations and minimal scars remaining. There were no recurrences of skin lesion recurrence or clinical manifestations of calcinosis.

Figure 4.

Improvement in CMAS over time. The patient’s CMAS score increased progressively from diagnosis to 24 months, indicating continuous improvement in muscle strength and function. CMAS was assessed at diagnosis, and at 6, 12, and 24 months of follow-up. CMAS: Childhood Myositis Assessment Scale.

The patient remains in sustained stable remission without any signs of disease activity on continuous Baricitinib therapy.

3. Discussion

This case demonstrates that Janus kinase (JAK) inhibition can be an effective therapy for patients with JDM, particularly those with a high interferon signature and MDA5 antibodies. The addition of the JAK inhibitor to the therapeutic regimen led to a rapid resolution of symptoms and disease control. This decision was guided by the markedly elevated interferon signature, the presence of MDA5 antibodies, and accumulating evidence supporting JAK inhibition as a targeted approach in JDM.

The primary goals in JDM therapy are to control inflammation, restore muscle strength, and prevent long-term sequelae [12,15]. Depending on disease severity, individualized therapeutic strategies should be employed. While corticosteroids and methotrexate remain first-line treatments, complications such as calcinosis, lipodystrophy, interstitial lung disease (ILD), and joint contractures pose significant management challenges. In refractory cases, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) beyond methotrexate, biologic agents, and small molecules are utilized [12,13,14].

Our patient demonstrated an elevated type I interferon (IFN) signature characterized by increased expression of IFI27, IFI44L, IFIT1, and RSAD2 (viperin), a validated whole-blood marker set reflecting systemic IFN-I pathway activation. This transcriptional signature has been shown to correlate with both muscle and skin disease activity in dermatomyositis [16,17]. In particular, the IFN signature decreases with effective therapy, including Janus kinase (JAK) inhibition, underscoring its value as a pharmacodynamic biomarker. In parallel, recent studies have identified circulating IFN-stimulated chemokines—CXCL10 (IP-10), CXCL11 (I-TAC), and galectin-9 (Gal-9)—as biomarkers that correlate with disease activity and longitudinal improvement in JDM. Monocyte expression of SIGLEC1 (CD169) also mirrors IFN-pathway activation and has emerged as a sensitive biomarker for both disease activity and therapeutic monitoring. Notably, Veldkamp et al. (2025) demonstrated that SIGLEC1 expression can serve as an in vitro biomarker of JAK-inhibitor efficacy in JDM, directly linking IFN-pathway activity with target engagement [18]. Collectively, these findings highlight how IFN-pathway biomarkers—including gene-expression signatures, inducible proteins, and SIGLEC1—can inform and rationalize targeted therapy in JDM. The favorable clinical response observed in our patient following JAK-inhibitor therapy supports this biologically guided approach and underscores the potential value of implementing IFN biomarker testing more broadly in clinical practice.

A comprehensive review of the literature was conducted using PubMed to identify studies reporting the use of JAK inhibitors in juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM). The search was performed using the keywords “JDM” and “JAK inhibitors,” covering publications from 2018 to 2025. A total of 27 reports and studies were identified, including cases treated with various JAK inhibitors, such as ruxolitinib, baricitinib, and tofacitinib. Overall, approximately 270 patients were reported to have received JAK inhibitor therapy, highlighting the emerging role of these agents in the management of refractory or severe JDM (Table 1). In addition, baricitinib has an established regulatory approval in pediatric populations, being indicated for atopic dermatitis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis from 2 years of age [19]. This existing pediatric safety and efficacy profile further supports the feasibility of baricitinib use in children and reinforces its potential as a therapeutic option in refractory juvenile dermatomyositis.

This growing body of evidence highlights the therapeutic potential of JAK inhibitors in JDM. Subsequent studies have specifically examined their efficacy in refractory cases, focusing on agents such as ruxolitinib, baricitinib, and tofacitinib. Aeschlimann et al. (2018) reported significant clinical improvement in a 13-year-old girl treated with ruxolitinib, with disease inactivity achieved at the 12-month follow-up [11]. Similarly, Heinen et al. (2021) observed marked recovery of muscle strength and reduction in inflammatory markers in a 14-year-old patient with anti-NXP2-positive JDM [20]. Larger studies, such as that by Huang et al. (2023), confirmed significant improvement of rash, muscle strength, and laboratory markers in 128 JDM patients receiving JAK inhibitors [21]. Notably, Ding et al. (2021) found that 96% of JDM patients exhibited rash improvement, with 66.7% achieving complete resolution of the rash, while muscle strength recovery was observed in 40% [22].

JAK inhibitors have also demonstrated efficacy in severe cases complicated by interstitial lung disease (ILD). Chan Ng et al. (2022) reported successful remission induction and maintenance with tofacitinib in pediatric JDM with rapidly progressive ILD [23]. Kaplan et al. (2023) highlighted clinical improvement and reduced interferon-alpha levels in anti-MDA5-positive JDM patients with ILD and cardiac involvement [24].

Calcinosis-associated JDM also appears responsive to JAK inhibition. Agud-Dios et al. (2022) described significant softening of calcium deposits and regained mobility in a 5-year-old patient treated with baricitinib [25]. Mastrolia et al. (2023) further supported the efficacy of baricitinib in refractory JDM complicated by calcinosis [26] (Table 1).

The safety profile of JAK inhibitors in JDM remains favorable, with most studies reporting good tolerability and minimal adverse effects. Aeschlimann et al. (2018) and Papadopoulou et al. (2019) observed no major adverse events in their respective patients treated with ruxolitinib and baricitinib, while corticosteroid tapering was achieved. Ding et al. (2021) also reported no severe infections among 25 JDM patients receiving JAK inhibitors [11,22,27].

However, some studies have reported potential safety concerns. Le Voyer et al. (2022) described cases of herpes zoster and skin abscesses in a cohort of 10 JDM patients treated with JAK inhibitors [28]. Huang et al. (2023) identified leukopenia and cough in a subset of patients, while 39.6% were able to discontinue glucocorticoids [21]. Kostik et al. (2022) documented a case of lymphadenitis associated with tofacitinib use [29]. Quintana-Ortega et al. (2022) described a fatal outcome in an 11-year-old patient with anti-MDA5-positive juvenile dermatomyositis and rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease treated with intensive combination immunosuppression including tofacitinib, underscoring the fulminant nature and high mortality risk of this condition [30]. Despite these findings, most adverse effects were manageable, and the overall benefit–risk profile of JAK inhibitors in JDM remains favorable, particularly in refractory disease cases (Table 1).

Importantly, uncertainties regarding long-term safety persist, especially in the context of childhood growth and immune system maturation. The JAK–STAT pathway plays a role not only in immune regulation but also in cell proliferation, differentiation, and metabolic processes [31]. Prolonged inhibition during childhood therefore raises theoretical concerns related to oncological risk, endocrine development, growth patterns, and the long-term shaping of adaptive immunity [32]. To date, no increase in malignancy or severe developmental disturbances has been reported [33]; however, available studies are limited by relatively short follow-up periods.

In this case, based on World Health Organization growth standards, the patient’s weight, height, and body mass index (BMI) percentiles were around the 50th percentile at treatment initiation and remained stable over a two-year follow-up, with no clinical evidence of growth impairment. Nonetheless, this favorable individual observation does not obviate the need for long-term prospective follow-up studies and registry-based surveillance to adequately define long-term outcomes and the true safety profile of JAK inhibitors in pediatric patients.

In juvenile dermatomyositis, JAK inhibitors represent one option within advanced immunomodulatory therapies. Oral administration and avoidance of prolonged immune cell depletion may be practical advantages in younger patients. Treatment response may vary by disease phenotype, and cost considerations should be addressed on a country-specific basis. Given limited long-term safety data in children, treatment decisions should be individualized.

Management of JDM is guided by the 2017 consensus-based recommendations developed within the European SHARE initiative, which outline a standardized, stepwise approach to corticosteroid and immunosuppressive therapy, complemented by physiotherapy and close monitoring of disease activity [34]. Within this framework, emerging biomarkers—such as interferon-pathway signatures—offer an opportunity to refine treatment decisions and support the rationale for targeted therapies like JAK inhibition.

4. Conclusions

JAK inhibitors hold promise as targeted agents for anti-MDA5 antibody-positive juvenile dermatomyositis, with potential roles in both induction and maintenance of remission. Their ability to achieve rapid disease control supports their integration into evolving treatment algorithms; however, rigorous clinical evaluation is still needed to confirm efficacy and safety and to define evidence-based management protocols.

Table 1.

Summary of reports on JAK inhibitor use in Juvenile Dermatomyositis (JDM).

Table 1.

Summary of reports on JAK inhibitor use in Juvenile Dermatomyositis (JDM).

| Study | Author(s) | Year | Patient Characteristics | Treatment | Efficacy | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [11] | Aeschlimann et al. | 2018 | 13-year-old female, refractory JDM, anti-NXP2+ | Ruxolitinib | Sustained remission, improved muscle strength, reduced inflammation | No major adverse events |

| [27] | Papadopoulou et al. | 2019 | 11-year-old, refractory JDM | Baricitinib | Strength, skin disease improved; steroid tapering | No adverse events, relapse after stopping |

| [35] | Sabbagh et al. | 2019 | Anti-MDA5+ JDM, refractory | Tofacitinib | Muscle, skin, lung function improved | No adverse events |

| [36] | Melki et al. | 2020 | JIIM patients with/without anti-MDA5, 4 cases | Various therapies, 4 patients Ruxolitinib | Required for remission in severe skin cases | Not specified |

| [37] | Sozeri & Demir | 2020 | 2 pediatric patients (JDM, refractory calcinosis) | Tofacitinib | Complete resolution of calcinosis in one patient, moderate improvement in the other | Not mentioned |

| [23] | Chan Ng et al. | 2021 | Pediatric JDM, rapidly progressive ILD | Tofacitinib | Remission achieved, ILD biomarkers improved | No adverse events |

| [22] | Ding et al. | 2021 | 25 JDM patients (mean age 7.2 ± 4.0) | Tofacitinib (n = 7), Ruxolitinib (n = 18) | Rash resolved (96%), muscle strength improved (40%) | No major adverse events |

| [20] | Heinen et al. | 2021 | 14-year-old male, NXP2+ JDM | Ruxolitinib | Improved strength, reduced inflammation | No major adverse events |

| [38] | Kim et al. | 2021 | 4 refractory JDM cases (ages 5.8–20.7) | Baricitinib | Strength, corticosteroid tapering improved | Not specified |

| [39] | Quintana-Ortega et al. | 2022 | 11-year-old, anti-MDA5+ JDM, ILD | Tofacitinib | No response | Fatal SARS-CoV-2 complication |

| [25] | Agud-Dios et al. | 2022 | 5-year-old male, JDM, calcinosis, contractures | Baricitinib | Improved muscle strength, calcinosis, mobility | No major adverse events |

| [29] | Kostik et al. | 2022 | 2 JDM patients (6-month follow-up) | Tofacitinib | One complete, one partial response | Lymphadenitis |

| [28] | Le Voyer et al. | 2022 | 10 JDM cases (9 refractory, 1 new-onset) | Ruxolitinib (n = 7), Baricitinib (n = 3) | 5 achieved inactive disease, steroids reduced | Herpes zoster, skin abscesses |

| [40] | Stewart et al. | 2022 | 1 pediatric patient (JDM, MAS as initial manifestation) | IVIG, steroids, mycophenolate, anakinra, tofacitinib | Resolution of MAS, improvement in multi-organ involvement | Not mentioned |

| [13] | Strauss et al. | 2023 | 4-year-old patient with MDA5 antibody | Ruxolitinib | Fast and sustained remission | No major adverse events |

| [21] | Huang et al. | 2023 | 9 (previously unreported) JDM patients | Ruxolitinib (n = 6), Baricitinib (n = 3) | Rash, muscle strength, and lab markers improved; 39.6% stopped steroids | Leukopenia, cough |

| [24] | Kaplan et al. | 2023 | Anti-MDA5+ JDM, ILD, cardiac involvement | Tofacitinib | Disease control with steroid tapering | Not specified |

[26] | Mastrolia et al. | 2023 | Refractory JDM, calcinosis | Baricitinib | Disease and calcinosis improved | Not specified |

| [41] | Wang et al. | 2023 | 20 children with refractory/severe JDM | Baricitinib (n = 20) + steroids + immunosuppressants | 95% improvement in skin rash, better muscle strength, reduced disease activity, 49% steroid reduction at 24 weeks | No serious side effects reported |

| [42] | Xue Y | 2023 | 9 anti-MDA5-positive children with JDM and ILD | Tofacitinib | 55.5% showed ILD improvement; 44.5% had worsened ILD; high IgG and T-cell levels correlated with poor response | Not mentioned |

| [43] | Zhang J | 2023 | A total of eighty-eight patients with JDM | Tofacitinib | Skin and muscle symptoms improved markedly. Nearly half achieved complete response, six remained on tofacitinib monotherapy. Lung disease improved in 60%, and calcinosis in 75% (complete resolution in 25%). | Only one patient had herpes zoster infection 9 months after initiation. After drug withdrawal, herpes recovered and tofacitinib was given again. |

| [44] | Yu et al. | 2023 | 3 children with refractory JDM | Tofacitinib | Improved muscle strength, skin lesions, quality of life, steroid tapering | No severe adverse events |

| [45] | Xiangyuan C. et al. | 2024 | 12-year-old girl with JDM who developed multiple GI perforations | Tofacitinib | Leading to gradual improvement in muscle strength and reduction in inflammation | No severe adverse events |

| [46] | Kinkor M et al. | 2024 | 14-month-old female with anti-MDA5 | Tofacitinib | Remission of skin and muscle disease | Not mentioned |

| [47] | Huang B et al. | 2024 | 11-year-old girl with juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM), anti-MDA5 antibodies and multiple skin ulcers | Tofacitinib | At the 2-month follow-up visit, early healing of the ulcers Within 8 months, the skin ulcers healed, and muscle enzyme markers and ESR returned to normal. | Not mentioned |

| [48] | Bader-Meunier B et al. | 2025 | Thirty-nine patients with JDM | Various therapies | A significant decrease in the median Type 1 IFN score and serum IFN-α from the diagnosis of JDM to the 6-month follow-up | JAKi-related adverse events consisted of infections in nine patients (including five herpes zoster infections) and weight gain in three patients. |

| [49] | Arguelles Balas D et al. | 2025 | 9-year-old Spanish boy | Tofacitinib | Remission with tofacitinib monotherapy following the failure of previous therapies | No AEs related to tofacitinib have been observed. |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Project administration: O.B., Ö.S., J.B.K.-D. and C.R.; Data curation and Formal analysis: O.B., Ö.S., J.B.K.-D. and C.R.; Funding acquisition: C.R.; Resources and Software: Ö.S. Supervision: J.B.K.-D. and C.R. Validation: O.B., Ö.S., J.B.K.-D. and C.R. Visualization: O.B. Writing—original draft: O.B., Ö.S., J.B.K.-D. and C.R. Writing—review and editing: O.B., Ö.S., J.B.K.-D. and C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Infrastructural support was provided by the participating centers. No other specific funding was received for this study.

Institutional Review Board approval

Not applicable. This manuscript is a single-patient case report with a review of the literature. According to local and national regulations, Ethics Committee/Institutional Review Board approval is not required for single case reports, provided that the patient’s identity is fully anonymized and that written informed consent is obtained.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants (or their legal guardians) provided written informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patient and his family for their willingness to participate in this report and for providing clinical photographs. We also thank the Department of Pediatric Radiology, University Hospital Tuebingen, for kindly providing the MRI images.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Marie, I. Morbidity and mortality in adult polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2012, 14, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, J.T.; Petty, R.E.; Laxer, R.M.; Lindsley, C.B. Textbook of Pediatric Rheumatology E-Book; Saunders/Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Baechler, E.C.; Bauer, J.W.; Slattery, C.A.; Ortmann, W.A.; Espe, K.J.; Novitzke, J.; Ytterberg, S.R.; Gregersen, P.K.; Behrens, T.W.; Reed, A.M. An interferon signature in the peripheral blood of dermatomyositis patients is associated with disease activity. Mol. Med. 2007, 13, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinal-Fernandez, I.; Casal-Dominguez, M.; Derfoul, A.; Pak, K.; Plotz, P.; Miller, F.W.; Milisenda, J.C.; Grau-Junyent, J.M.; Selva-O’Callaghan, A.; Paik, J.; et al. Identification of distinctive interferon gene signatures in different types of myositis. Neurology 2019, 93, e1193–e1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallwork, R.S.; Paik, J.J.; Kim, H. Current evidence for janus kinase inhibitors in adult and juvenile dermatomyositis and key comparisons. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2024, 25, 1625–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casal-Dominguez, M.; Pinal-Fernandez, I.; Mammen, A.L. Inhibiting interferon pathways in dermatomyositis: Rationale and preliminary evidence. Curr. Treat. Opt. Rheumatol. 2021, 7, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, Y.; Luo, Y.; O’Shea, J.J.; Nakayamada, S. Janus kinase-targeting therapies in rheumatology: A mechanisms-based approach. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2022, 18, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, S.; He, X.; Ji, J. Risk factors for mortality in anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis with interstitial lung disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1628748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, L.; Huang, Y.; Yan, S.; Li, H.; Zhan, H.; Li, Y. Roles of biomarkers in anti-MDA5-positive dermatomyositis, associated interstitial lung disease, and rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, A.M.; Giannini, E.H.; Bowyer, S.L.; Kim, S.; Lang, B.; Lindsley, C.B.; Pachman, L.M.; Pilkington, C.; Reed, A.M.; Rennebohm, R.M.; et al. Protocols for the initial treatment of moderately severe juvenile dermatomyositis: Results of a Children’s Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance Consensus Conference. Arthritis Care Res. 2010, 62, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeschlimann, F.A.; Fremond, M.L.; Duffy, D.; Rice, G.I.; Charuel, J.L.; Bondet, V.; Saire, E.; Neven, B.; Bodemer, C.; Balu, L.; et al. A child with severe juvenile dermatomyositis treated with ruxolitinib. Brain 2018, 141, e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hinze, C.H.; Oommen, P.T.; Dressler, F.; Urban, A.; Weller-Heinemann, F.; Speth, F.; Lainka, E.; Brunner, J.; Fesq, H.; Foell, D.; et al. Development of practice and consensus-based strategies including a treat-to-target approach for the management of moderate and severe juvenile dermatomyositis in Germany and Austria. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online J. 2018, 16, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, T.; Gunther, C.; Schnabel, A.; Wolf, C.; Hahn, G.; Lee-Kirsch, M.A.; Bruck, N. Rapid and sustained response to JAK inhibition in a child with severe MDA5 + juvenile dermatomyositis. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online J. 2023, 21, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinze, C. Juvenile dermatomyositis-what’s new? Z. Rheumatol. 2019, 78, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, M.A.; Nicolai, R.; Datyner, E.K.; Rosina, S.; Hamilton, A.; Ardalan, K.; Bader-Meunier, B.; Brown, A.G.; Jansen, M.H.A.; Kim, S.; et al. Approach to Janus kinase inhibition for juvenile dermatomyositis among CARRA and PReS providers. Rheumatology 2025, 64, 4732–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladislau, L.; Suarez-Calvet, X.; Toquet, S.; Landon-Cardinal, O.; Amelin, D.; Depp, M.; Rodero, M.P.; Hathazi, D.; Duffy, D.; Bondet, V.; et al. JAK inhibitor improves type I interferon induced damage: Proof of concept in dermatomyositis. Brain 2018, 141, 1609–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huard, C.; Gulla, S.V.; Bennett, D.V.; Coyle, A.J.; Vleugels, R.A.; Greenberg, S.A. Correlation of cutaneous disease activity with type 1 interferon gene signature and interferon beta in dermatomyositis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 176, 1224–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veldkamp, S.R.; Reugebrink, M.; Evers, S.W.; Moreau, T.R.J.; Bondet, V.; Armbrust, W.; van den Berg, J.M.; Hissink Muller, P.C.E.; Kamphuis, S.; Schatorje, E.; et al. Targeting interferon responses in juvenile dermatomyositis: Siglec-1 as an in vitro biomarker for JAK inhibitor efficacy. Rheumatology 2025, 64, 5132–5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMA. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/olumiant (accessed on 8 January 2020).

- Heinen, A.; Schnabel, A.; Bruck, N.; Smitka, M.; Wolf, C.; Lucas, N.; Dollinger, S.; Hahn, G.; Gunther, C.; Berner, R.; et al. Interferon signature guiding therapeutic decision making: Ruxolitinib as first-line therapy for severe juvenile dermatomyositis? Rheumatology 2021, 60, e136–e138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Wang, X.; Niu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Wang, X.; Tan, Q.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chi, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Long-term follow-up of Janus-kinase inhibitor and novel active disease biomarker in juvenile dermatomyositis. Rheumatology 2023, 62, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Huang, B.; Wang, Y.; Hou, J.; Chi, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Li, J. Janus kinase inhibitor significantly improved rash and muscle strength in juvenile dermatomyositis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 543–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan Ng, P.L.P.; Mopur, A.; Goh, D.Y.T.; Ramamurthy, M.B.; Lim, M.T.C.; Lim, L.K.; Ooi, P.L.; Ang, E.Y. Janus kinase inhibition in induction treatment of anti-MDA5 juvenile dermatomyositis-associated rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2022, 25, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, M.M.; Celikel, E.; Gungorer, V.; Ekici Tekin, Z.; Gursu, H.A.; Polat, S.E.; Cinel, G.; Celikel Acar, B. Cardiac involvement in a case of juvenile dermatomyositis with positive anti-melanoma differentiation associated protein 5 antibody. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 26, 1582–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agud-Dios, M.; Arroyo-Andres, J.; Rubio-Muniz, C.; Zarco-Olivo, C.; Calleja-Algarra, A.; de Inocencio, J.; Perez, S.I.P. Juvenile dermatomyositis-associated calcinosis successfully treated with combined immunosuppressive, bisphosphonate, oral baricitinib and physical therapy. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrolia, M.V.; Orsini, S.I.; Marrani, E.; Maccora, I.; Pagnini, I.; Simonini, G. Efficacy of Janus kinase inhibitor baricitinib in the treatment of refractory juvenile dermatomyositis complicated by calcinosis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2023, 41, 402–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, C.; Hong, Y.; Omoyinmi, E.; Brogan, P.A.; Eleftheriou, D. Janus kinase 1/2 inhibition with baricitinib in the treatment of juvenile dermatomyositis. Brain 2019, 142, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Voyer, T.; Gitiaux, C.; Authier, F.J.; Bodemer, C.; Melki, I.; Quartier, P.; Aeschlimann, F.; Isapof, A.; Herbeuval, J.P.; Bondet, V.; et al. JAK inhibitors are effective in a subset of patients with juvenile dermatomyositis: A monocentric retrospective study. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 5801–5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostik, M.M.; Raupov, R.K.; Suspitsin, E.N.; Isupova, E.A.; Gaidar, E.V.; Gabrusskaya, T.V.; Kaneva, M.A.; Snegireva, L.S.; Likhacheva, T.S.; Miulkidzhan, R.S.; et al. The Safety and Efficacy of Tofacitinib in 24 Cases of Pediatric Rheumatic Diseases: Single Centre Experience. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 820586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintana-Ortega, C.; Remesal, A.; Ruiz de Valbuena, M.; de la Serna, O.; Laplaza-Gonzalez, M.; Alvarez-Rojas, E.; Udaondo, C.; Alcobendas, R.; Murias, S. Fatal outcome of anti-MDA5 juvenile dermatomyositis in a paediatric COVID-19 patient: A case report. Mod. Rheumatol. Case Rep. 2021, 5, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, D.M.; Kanno, Y.; Villarino, A.; Ward, M.; Gadina, M.; O’Shea, J.J. JAK inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for immune and inflammatory diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 843–862, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 78. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2017.267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikaeili, B.; Alqahtani, Z.A.; Hincapie, A.L.; Guo, J.J. Safety of Janus kinase inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis: A disproportionality analysis using FAERS database from 2012 to 2022. Clin. Rheumatol. 2025, 44, 1467–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winthrop, K. Erratum: The emerging safety profile of JAK inhibitors in rheumatic disease. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2017, 13, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellutti Enders, F.; Bader-Meunier, B.; Baildam, E.; Constantin, T.; Dolezalova, P.; Feldman, B.M.; Lahdenne, P.; Magnusson, B.; Nistala, K.; Ozen, S.; et al. Consensus-based recommendations for the management of juvenile dermatomyositis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, S.; Almeida de Jesus, A.; Hwang, S.; Kuehn, H.S.; Kim, H.; Jung, L.; Carrasco, R.; Rosenzweig, S.; Goldbach-Mansky, R.; Rider, L.G. Treatment of anti-MDA5 autoantibody-positive juvenile dermatomyositis using tofacitinib. Brain 2019, 142, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melki, I.; Devilliers, H.; Gitiaux, C.; Bondet, V.; Duffy, D.; Charuel, J.L.; Miyara, M.; Bokov, P.; Kheniche, A.; Kwon, T.; et al. Anti-MDA5 juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathy: A specific subgroup defined by differentially enhanced interferon-alpha signalling. Rheumatology 2020, 59, 1927–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sozeri, B.; Demir, F. A striking treatment option for recalcitrant calcinosis in juvenile dermatomyositis: Tofacitinib citrate. Rheumatology 2020, 59, e140–e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Dill, S.; O’Brien, M.; Vian, L.; Li, X.; Manukyan, M.; Jain, M.; Adeojo, L.W.; George, J.; Perez, M.; et al. Janus kinase (JAK) inhibition with baricitinib in refractory juvenile dermatomyositis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 406–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana-Ortega, C.; Prieto-Moreno Pfeifer, A.; Palomino Lozano, L.; Lancharro, A.; Saavedra Lozano, J.; Villa-Garcia, A.J.; Seoane-Reula, E. Colchicine as rescue treatment in two pediatric patients with chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO). Mod. Rheumatol. Case Rep. 2023, 7, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.A.; Price, T.; Moser, S.; Mullikin, D.; Bryan, A. Progressive, refractory macrophage activation syndrome as the initial presentation of anti-MDA5 antibody positive juvenile dermatomyositis: A case report and literature review. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online J. 2022, 20, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.T.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, T.; Luo, C.; Liu, M.Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, L.; Tang, X.M. Anti-nuclear matrix protein 2+ juvenile dermatomyositis with severe skin ulcer and infection: A case report and literature review. World J. Clin. Cases 2022, 10, 3579–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhang, J.; Deng, J.; Kuang, W.; Wang, J.; Tan, X.; Li, C.; Li, S.; Li, C. Efficiency of tofacitinib in refractory interstitial lung disease among anti-MDA5 positive juvenile dermatomyositis patients. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 1499–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, L.; Shi, X.; Li, S.; Liu, C.; Li, X.; Lu, M.; Deng, J.; Tan, X.; Guan, W.; et al. Janus kinase inhibitor, tofacitinib, in refractory juvenile dermatomyositis: A retrospective multi-central study in China. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2023, 25, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, L.; Quan, M.; Zhang, T.; Song, H. Successful management with Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib in refractory juvenile dermatomyositis: A pilot study and literature review. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 1700–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiangyuan, C.; Xiaoling, Z.; Guangchao, S.; Huasong, Z.; Dexin, L. Juvenile dermatomyositis complications: Navigating gastrointestinal perforations and treatment challenges, a case report. Front. Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1419355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinkor, M.; Hameed, S.; Kats, A.; Slowik, V.; Fox, E.; Ibarra, M. 14-month-old female with anti-MDA5 juvenile dermatomyositis complicated by liver disease: A case report. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online J. 2024, 22, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Huang, W.; Hao, S. Cutaneous ulceration in juvenile dermatomyositis with anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2024, 41, 342–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bader-Meunier, B.; Moreau, T.R.J.; Aeschlimann, F.; Authier, F.J.; Charuel, J.L.; Jouen, F.; Boyer, O.; Bodemer, C.; Welfringer-Morin, A.; Bondet, V.; et al. Myositis-specific autoantibody subtypes are associated with response to Janus kinase inhibitors in patients with juvenile dermatomyositis. Rheumatology 2025, 64, 5487–5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arguelles Balas, D.; Barral Mena, E.; Martin Diaz, M.A.; Calvo-Aranda, E. Tofacitinib monotherapy as maintenance treatment in juvenile dermatomyositis: A case report. RMD Open 2025, 11, e005651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.