Duration Dependent Outcomes of Combined Dorsal Root Ganglion Pulsed Radiofrequency and Epidural Steroid Injection in Chronic Lumbosacral Radicular Pain

Abstract

1. Introduction

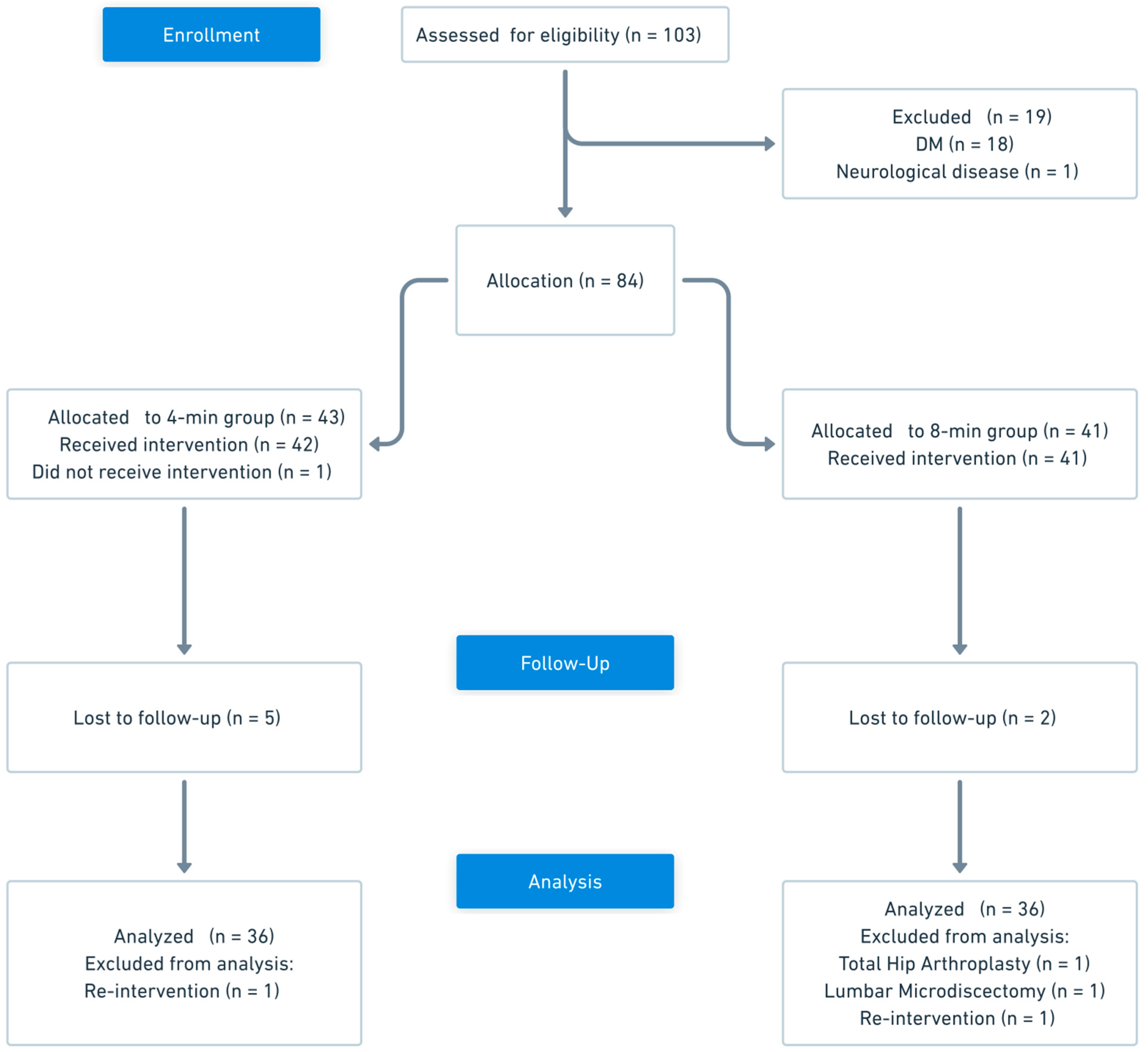

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patient Population

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Age ≥ 18 years.

- Chronic LRP persisting for ≥ 12 weeks.

- Insufficient pain relief (NRS ≥ 4) despite at least 4 weeks of conservative management, including physical therapy and/or pharmacological treatment (e.g., NSAIDs, gabapentinoids, or duloxetine).

- Radiological evidence of nerve root compression on lumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), attributed to a herniated intervertebral disk (HIVD) or spinal stenosis.

- Persistent or recurrent radicular pain (NRS ≥ 4) at the time of PRF evaluation despite receiving at least one TFESI > 3 weeks prior.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Patient refusal.

- Lumbar radicular pain due to malignancy or infection.

- Diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and/or polyneuropathy.

- Diagnosis of demyelinating disorder (e.g., multiple sclerosis).

- Predominant axial low back pain.

- Neuropsychiatric conditions that would hinder follow-up and assessment (e.g., dementia and severe psychiatric disorders).

- Progressive motor weakness or cauda equina syndrome requiring urgent surgical intervention.

- Active systemic infection or infection at the injection site.

- Cardiac implantable electronic device.

- Known allergy to local anesthetic agents or contrast media.

- Presence of bleeding or coagulation disorders or ongoing use of oral anticoagulants.

2.3. Group Allocation

2.4. Treatment Protocols

2.5. Outcome Measures and Data Collection

2.6. Power Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

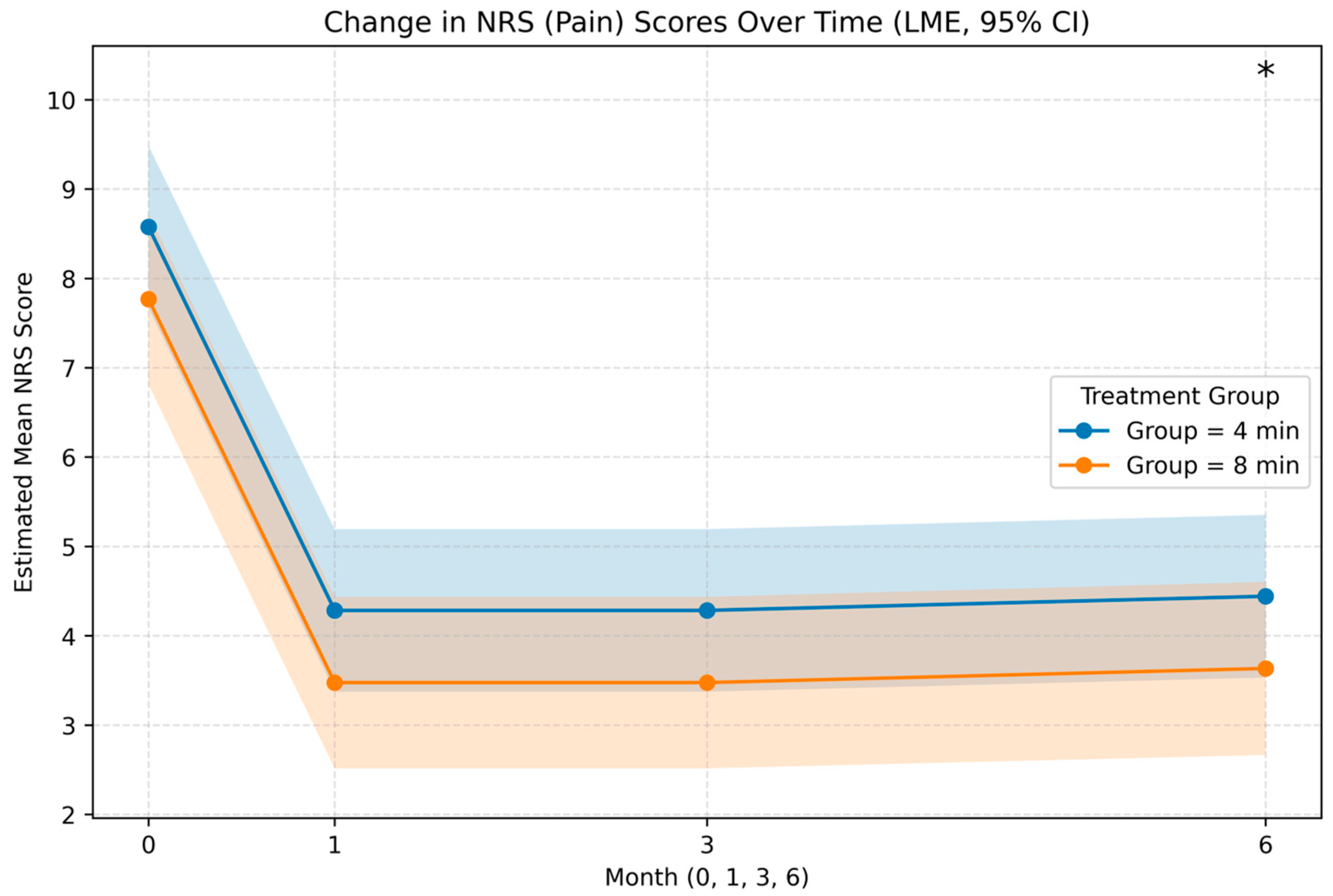

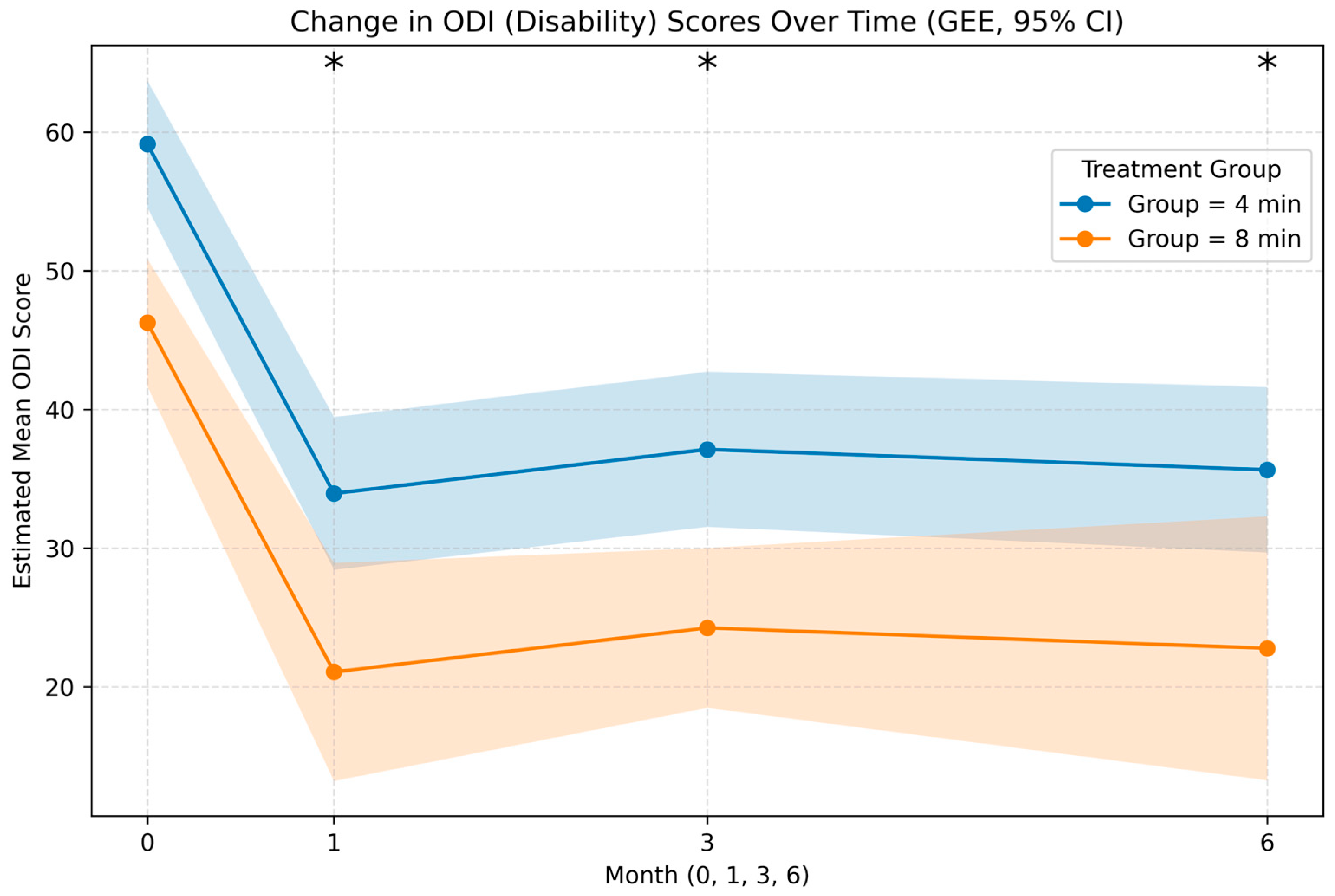

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CCI | Chronic constriction injury |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| DRG | Dorsal root ganglion |

| ESI | Epidural steroid injection |

| GEE | Generalized estimating equations |

| GPES | Global Perceived Effect of Satisfaction |

| HIVD | Herniated intervertebral disk |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| LME | Linear mixed-effects |

| LRP | Lumbosacral radicular pain |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| n | Number of patients |

| NRS | Numeric Rating Scale |

| NSAID | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| ODI | Oswestry Disability Index |

| PRF | Pulsed radiofrequency |

| SE | Standard Error |

| SNL | Spinal nerve ligation |

| TFESI | Transforaminal epidural steroid injection |

References

- Van Boxem, K.; Cheng, J.; Patijn, J.; Van Kleef, M.; Lataster, A.; Mekhail, N.; Van Zundert, J. Lumbosacral radicular pain. Pain Pract. 2010, 10, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peene, L.; Cohen, S.P.; Kallewaard, J.W.; Wolff, A.; Huygen, F.; Gaag, A.V.; Monique, S.; Vissers, K.; Gilligan, C.; Van Zundert, J.; et al. Lumbosacral radicular pain. Pain Pract. 2024, 24, 525–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Melhat, A.M.; Youssef, A.S.A.; Zebdawi, M.R.; Hafez, M.A.; Khalil, L.H.; Harrison, D.E. Non-Surgical Approaches to the Management of Lumbar Disc Herniation Associated with Radiculopathy: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carassiti, M.; Pascarella, G.; Strumia, A.; Russo, F.; Papalia, G.F.; Cataldo, R.; Gargano, F.; Costa, F.; Pierri, M.; De Tommasi, F.; et al. Epidural Steroid Injections for Low Back Pain: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Boxem, K.; de Meij, N.; Kessels, A.; Van Kleef, M.; Van Zundert, J. Pulsed radiofrequency for chronic intractable lumbosacral radicular pain: A six-month cohort study. Pain Med. 2015, 16, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, M.C.; Cho, Y.W.; Ahn, S.H. Comparison between bipolar pulsed radiofrequency and monopolar pulsed radiofrequency in chronic lumbosacral radicular pain: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine 2017, 96, e6236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanneste, T.; Van Lantschoot, A.; Van Boxem, K.; Van Zundert, J. Pulsed radiofrequency in chronic pain. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2017, 30, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahana, A.; Van Zundert, J.; Macrea, L.; van Kleef, M.; Sluijter, M. Pulsed radiofrequency: Current clinical and biological literature available. Pain Med. 2006, 7, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, J.; Catapano, M.; Sahni, S.; Ma, F.; Abd-Elsayed, A.; Visnjevac, O. Pulsed Radiofrequency in Interventional Pain Management: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Action—An Update and Review. Pain Physician 2021, 24, 525–532. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Huang, D.; Ma, J.; Huang, Y. Pulsed Radiofrequency Relieves Neuropathic Pain by Repairing the Ultrastructural Damage of Chronically Compressed Dorsal Root Ganglion. Neurosci. Insights 2025, 20, 26331055251339081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.G.; Ahn, S.H.; Lee, J. Comparative Effectivenesses of Pulsed Radiofrequency and Transforaminal Steroid Injection for Radicular Pain due to Disc Herniation: A Prospective Randomized Trial. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2016, 31, 1324–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuka, I.; Marciuš, T.; Došenović, S.; Ferhatović Hamzić, L.; Vučić, K.; Sapunar, D.; Puljak, L. Efficacy and Safety of Pulsed Radiofrequency as a Method of Dorsal Root Ganglia Stimulation in Patients with Neuropathic Pain: A Systematic Review. Pain Med. 2020, 21, 3320–3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzy, E.A.; Khalil, K.I.; Nour, E.M.; Hamed, M.F.; Taha, M.A. Evaluation of the Effect of Duration on the Efficacy of Pulsed Radiofrequency in an Animal Model of Neuropathic Pain. Pain Physician 2018, 21, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arakawa, K.; Kaku, R.; Kurita, M.; Matsuoka, Y.; Morimatsu, H. Prolonged-duration pulsed radiofrequency is associated with increased neuronal damage without further antiallodynic effects in neuropathic pain model rats. J. Pain Res. 2018, 11, 2645–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.N.; Park, S.; Park, J.H.; Choi, Y.S.; Park, S. Efficacy of pulsed radiofrequency treatment duration to the lumbar dorsal root ganglion in lumbar radicular pain: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Jang, J.N.; Park, J.H.; Song, Y.; Sooil, C.; Kim, Y.U.; Park, S. Comparing the effectiveness of pulsed radiofrequency treatment to lumbar dorsal root ganglion according to application times in patients with lumbar radicular pain: Protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e077847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakut, E.; Düger, T.; Oksüz, C.; Yörükan, S.; Ureten, K.; Turan, D.; Frat, T.; Kiraz, S.; Krd, N.; Kayhan, H.; et al. Validation of the Turkish version of the Oswestry Disability Index for patients with low back pain. Spine 2004, 29, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Chang, M.C. The mechanism of action of pulsed radiofrequency in reducing pain: A narrative review. J. Yeungnam Med. Sci. 2022, 39, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cruz, J.; Benzecry Almeida, D.; Silva Marques, M.; Ramina, R.; Fortes Kubiak, R.J. Elucidating the Mechanisms of Pulsed Radiofrequency for Pain Treatment. Cureus 2023, 15, e44922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, M.A.; Safar, O.; Almurayyi, M.; Alahmadi, A.; Alahmadi, A.M.; Aljohani, M.; Almhmd, A.E.; Almujel, K.N.; Alyousef, B.; Bashraheel, H.; et al. Pulsed Radiofrequency Ablation for Orchialgia-A Literature Review. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zundert, J.; de Louw, A.J.; Joosten, E.A.; Kessels, A.G.; Honig, W.; Dederen, P.J.; Veening, J.G.; Vles, J.S.; van Kleef, M. Pulsed and continuous radiofrequency current adjacent to the cervical dorsal root ganglion of the rat induces late cellular activity in the dorsal horn. Anesthesiology 2005, 102, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdine, S.; Bilir, A.; Cosman, E.R.; Cosman, E.R., Jr. Ultrastructural changes in axons following exposure to pulsed radiofrequency fields. Pain Pract. 2009, 9, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, N.; Yamaga, M.; Tateyama, S.; Uno, T.; Tsuneyoshi, I.; Takasaki, M. The effect of pulsed radiofrequency current on mechanical allodynia induced with resiniferatoxin in rats. Anesth. Analg. 2010, 111, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Park, J.H.; Jang, J.N.; Choi, S.I.; Song, Y.; Kim, Y.U.; Park, S. Pulsed radiofrequency of lumbar dorsal root ganglion for lumbar radicular pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Pract. 2024, 24, 772–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.S.; Kim, Y.; Kim, D.H.; Kwon, H.J.; Shin, J.W.; Choi, S.S. Effects of Pulsed Radiofrequency Duration in Patients with Chronic Lumbosacral Radicular Pain: A Randomized Double-Blind Study. Neuromodulation 2025, 28, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 4 min (n = 36) | 8 min (n = 36) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) (years) | 58.5 (54.0–68.5) | 53.5 (41.0–63.2) | 0.073 |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 27.0 (24.4–31.1) | 25.9 (24.4–28.6) | 0.714 |

| NRS baseline, median (IQR) | 8.0 (7.0–9.0) | 8.0 (7.8–9.0) | 0.718 |

| ODI baseline, median (IQR) | 55.0 (43.5–64.0) | 54.0 (41.5–70.5) | 0.685 |

| Pain duration (months), median (IQR) | 12.0 (6.0–39.0) | 12.0 (6.0–24.0) | 0.225 |

| Sex, female (%) | 58.3% | 63.9% | 0.629 |

| NSAID (%) | 97.2% | 97.2% | 1.000 |

| Opioid (%) | 22.2% | 13.9% | 0.358 |

| Gabapentinoid (%) | 13.9% | 8.3% | 0.453 |

| Duloxetine (%) | 22.2% | 13.9% | 0.358 |

| Physical therapy (%) | 80.6% | 77.8% | 0.772 |

| Surgery (%) | 13.9% | 19.4% | 0.527 |

| Outcome | Time | 4 min (n = 36) | 8 min (n = 36) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRS—Absolute change | 1 mo | −4.0 (−5.0, −2.0) | −4.0 (−6.0, −2.8) | 0.283 |

| NRS—Percent change (%) | 1 mo | −50.0 (−57.9, −25.0) | −50.0 (−75.7, −33.3) | 0.238 |

| ODI—Absolute change | 1 mo | −22.0 (−32.0, −4.0) | −24.0 (−40.0, −10.0) | 0.457 |

| ODI—Percent change (%) | 1 mo | −43.9 (−58.1, −7.2) | −46.1 (−76.5, −20.9) | 0.478 |

| NRS—Absolute change | 3 mo | −3.0 (−5.0, −2.0) | −4.5 (−6.0, −3.0) | 0.220 |

| NRS—Percent change (%) | 3 mo | −45.0 (−64.7, −25.0) | −56.3 (−75.7, −37.5) | 0.200 |

| ODI—Absolute change | 3 mo | −21.0 (−32.5, −5.5) | −27.0 (−46.5, −10.0) | 0.138 |

| ODI—Percent change (%) | 3 mo | −37.2 (−64.4, −7.9) | −54.2 (−78.3, −23.2) | 0.093 |

| NRS *—Absolute change | 6 mo | −3.0 (−6.0, −1.0) | −5.0 (−6.5, −2.0) | 0.215 |

| NRS *—Percent change (%) | 6 mo | −43.8 (−75.0, −19.2) | −62.5 (−82.9, −35.4) | 0.141 |

| ODI *—Absolute change | 6 mo | −17.0 (−38.0, −3.5) | −28.0 (−46.0, −9.0) | 0.153 |

| ODI *—Percent change (%) | 6 mo | −33.5 (−64.1, −6.4) | −57.1 (−85.3, −19.1) | 0.104 |

| Outcome | Month | 4 min | 8 min | χ2 (1) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPES responder (≥6) | 1 | 19/36 (52.8%) | 18/36 (50.0%) | 0.06 | 0.812 |

| Patient satisfaction (satisfied) | 1 | 26/36 (72.2%) | 25/36 (69.4%) | 0.07 | 0.802 |

| Medication decreased/stopped | 1 | 19/36 (52.8%) | 21/36 (58.3%) | 0.22 | 0.642 |

| GPES responder (≥6) | 3 | 17/36 (47.2%) | 24/36 (66.7%) | 2.78 | 0.102 |

| Patient satisfaction (satisfied) | 3 | 22/36 (61.1%) | 24/36 (66.7%) | 0.24 | 0.622 |

| Medication decreased/stopped | 3 | 17/36 (47.2%) | 23/36 (63.9%) | 2.02 | 0.152 |

| GPES responder (≥6) | 6 | 13/36 (36.1%) | 20/35 (57.1%) | 3.16 | 0.082 |

| Patient satisfaction (satisfied) | 6 | 18/36 (50.0%) | 23/35 (65.7%) | 1.80 | 0.182 |

| Medication decreased/stopped | 6 | 17/36 (47.2%) | 21/35 (60.0%) | 1.16 | 0.282 |

| NRS responder (≥50%) | 1 | 20/36 (55.6%) | 20/36 (55.6%) | 0.00 | 1.000 |

| NRS responder (≥50%) | 3 | 18/36 (50.0%) | 23/36 (63.9%) | 1.42 | 0.230 |

| NRS responder (≥50%) | 6 | 18/36 (50.0%) | 22/35 (62.9%) | 1.19 | 0.270 |

| ODI responder (≥30%) | 1 | 25/36 (69.4%) | 28/36 (77.8%) | 0.64 | 0.420 |

| ODI responder (≥30%) | 3 | 24/36 (66.7%) | 29/36 (80.6%) | 1.79 | 0.180 |

| ODI responder (≥30%) | 6 | 24/36 (66.7%) | 26/35 (74.3%) | 0.49 | 0.480 |

| NRS | Month | Estimate | Std. Error (SE) | 95% CI (Lower, Upper) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Effect | Overall | −0.81 | 0.36 | −1.52, −0.10 | 0.025 |

| Month-Specific Differences | 0 | 0.41 | 0.67 | −0.91, 1.72 | 0.544 |

| 1 | −1.21 | 0.67 | −2.53, 0.10 | 0.071 | |

| 3 | −1.09 | 0.67 | −2.41, 0.22 | 0.103 | |

| 6 | −1.35 | 0.69 | −2.70, −0.01 | 0.048 | |

| ODI | Month | Estimate | Std. Error (SE) | 95% CI (Lower, Upper) | pValue |

| Main effect | |||||

| LME (Primary model) | Overall | −12.84 | 3.33 | −19.36, −6.32 | <0.001 |

| GEE (Robust alternative) | Overall | −12.87 | 3.01 | −18.76, −6.98 | <0.001 |

| Month-Specific Differences | |||||

| LME (Primary model) | 0 | −4.67 | 6.43 | −17.27, 7.94 | 0.468 |

| 1 | −11.87 | 6.43 | −24.47, 0.74 | 0.065 | |

| 3 | −17.79 | 6.43 | −30.40, −5.18 | 0.006 | |

| 6 | −17.23 | 6.56 | −30.10, −4.37 | 0.009 | |

| GEE (Robust alternative) | 0 | −4.69 | 2.93 | −10.44, 1.06 | 0.110 |

| 1 | −11.89 | 3.13 | −18.03, −5.75 | <0.001 | |

| 3 | −17.81 | 5.44 | −28.47, −7.15 | 0.001 | |

| 6 | −17.27 | 5.58 | −28.20, −6.33 | 0.002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Babaoğlu, G.; Şahutoğlu Bal, N.; Sabuncu, Ü.; Dadalı, Ş.; Çoştu, A.; Çelik, Ş.; Akçaboy, E.Y. Duration Dependent Outcomes of Combined Dorsal Root Ganglion Pulsed Radiofrequency and Epidural Steroid Injection in Chronic Lumbosacral Radicular Pain. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 708. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020708

Babaoğlu G, Şahutoğlu Bal N, Sabuncu Ü, Dadalı Ş, Çoştu A, Çelik Ş, Akçaboy EY. Duration Dependent Outcomes of Combined Dorsal Root Ganglion Pulsed Radiofrequency and Epidural Steroid Injection in Chronic Lumbosacral Radicular Pain. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):708. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020708

Chicago/Turabian StyleBabaoğlu, Gülçin, Nevcihan Şahutoğlu Bal, Ülkü Sabuncu, Şükriye Dadalı, Ali Çoştu, Şeref Çelik, and Erkan Yavuz Akçaboy. 2026. "Duration Dependent Outcomes of Combined Dorsal Root Ganglion Pulsed Radiofrequency and Epidural Steroid Injection in Chronic Lumbosacral Radicular Pain" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 708. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020708

APA StyleBabaoğlu, G., Şahutoğlu Bal, N., Sabuncu, Ü., Dadalı, Ş., Çoştu, A., Çelik, Ş., & Akçaboy, E. Y. (2026). Duration Dependent Outcomes of Combined Dorsal Root Ganglion Pulsed Radiofrequency and Epidural Steroid Injection in Chronic Lumbosacral Radicular Pain. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 708. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020708