Abstract

Objectives: Colorectal cancer is a major public health concern, ranking third in incidence among all malignant tumors both in Poland and globally. We conducted a retrospective study to evaluate the effectiveness of regorafenib in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer ineligible for local therapy treated at two Polish comprehensive cancer centers between 2021 and 2024. Methods: The analysis included 29 patients who had previously received all standard therapies: fluoropyrimidines, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan (in a multi-agent regimen or sequentially) and bevacizumab (anti-VEGF therapy). In patients with tumors negative for KRAS, NRAS and BRAF mutations, cetuximab or panitumumab (anti-EGFR therapy) were also used. Results: The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 2.5 months, and the median overall survival (OS) was 5.8 months. Disease stabilization was observed in five patients, with a median duration of 5.6 months, and no partial or complete remission were recorded. Conclusions: Our results were similar to those of the phase III CORRECT trial, which established the clinical utility of regorafenib. Only minor differences in survival outcomes were noted—likely due to real-world variability in patient characteristics and timing of treatment assessments. However, continued investigation of personalized and sequential treatment strategies that contain anti-angiogenic drugs is warranted to optimize outcomes.

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer represents a significant public health problem, ranking third in terms of incidence among malignant neoplasms both in Poland and globally [1,2]. In Poland, 17,700 individuals were diagnosed with colorectal cancer in 2021 [2].

According to ESMO guidelines, 15–20% of patients present with metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis, and approximately 20–50% of patients with non-advanced disease will develop metastatic disease during the course of their illness [3].

In advanced disease, standard management is based on multi-drug chemotherapy, either combined with targeted agents or administered without them, as well as immunotherapy [3]. At the time of treatment qualification, therapeutic decisions are made considering the patient’s condition, comorbidities, preferences regarding the mode of treatment administration, and consent to potential adverse effects. Another critical factor influencing treatment strategy is the outcome of molecular testing, which includes the identification of mutations in the KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF genes, as well as the assessment of microsatellite instability/mismatch repair status.

Recent advancements in personalized medicine have enabled tailoring therapies to the molecular aberrations of tumors [4]. For patients with the BRAF V600E mutation, which occurs in 8–12% of cases, combination therapy with encorafenib and cetuximab can be considered based on the results of the BEACON study [5]. Another molecular aberration for which targeted therapy may be considered is HER2 overexpression, observed in 3–5% of patients [6]. Additionally, the KRAS G12C mutation, present in 3% of colorectal cancer cases, allows for the use of dual-drug regimens such as sotorasib and panitumumab, based on the phase III CodeBreak 300 trial [7], or adagrasib and cetuximab, based on the phase I/II KRYSTAL-1 trial [8]. Entrectinib and larotrectinib can be utilized in patients with NTRK1, NTRK2, or NTRK3 gene fusions, which occur in less than 1% of colorectal cancer cases [9]. Furthermore, based on the phase I/II basket trial Libretto-001, selpercatinib may be considered for patients with RET gene fusions, observed in fewer than 1% of cases [10].

For patients without the aforementioned molecular aberrations who had received all standard drugs and are in very good or good performance status and express a willingness to continue treatment, there are no clear guidelines regarding the continuation of therapy. One of the options to consider is regorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor, targeting kinases involved in tumor angiogenesis and oncogenesis as well as kinases associated with the tumor microenvironment. Regorafenib particularly inhibits mutated KIT kinase, a key driver of oncogenesis, thereby blocking tumor cell proliferation. Its efficacy after all approved standard therapies was confirmed in the phase III CORRECT trial [11]. This study was conducted between 2010 and 2011 across 114 centers in 16 countries. A total of 760 patients were enrolled and randomized in a 2:1 ratio into two groups: the first group received regorafenib, while the second group received a placebo. Both groups were provided with best supportive care. Eligible participants had to have life expectancy exceeding three months. The trial achieved statistical significance for both its primary and secondary endpoints, which were overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), respectively.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the efficacy of regorafenib in patients from two Polish oncology centers by assessing PFS and OS, and compare them with the results of the CORRECT trial.

2. Materials and Methods

The study included 30 patients with inoperable metastatic colorectal cancer treated with regorafenib between 2021 and 2024 from two oncology centers (The Multidisciplinary Center of Oncology and Traumatology in Lodz and Tadeusz Koszarowski Cancer Center in Opole). One patient was excluded from the analysis as he did not attend the scheduled visit after the first treatment cycle and missed subsequent cycles. His survival exceeded the planned imaging evaluation after 3 months, leading to exclusion. The final analysis was conducted on data from 29 patients. All patients were initially qualified to receive the standard dose of 160 mg once daily for 3 weeks. The drug was reimbursed based on the individual approvals (the Emergency Access to Drug Technology).

Statistical analyses were performed to evaluate PFS and OS within a time-to-event framework. PFS was defined as the time from the start of treatment until disease progression or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. OS was defined as the time from the start of treatment until death from any cause. Patients who were alive at the last follow-up were censored at that time. The analysis included the calculation of median values of PFS and OS, along with the comparison of survival curves using Kaplan–Meier estimation. Data visualization was generated using Python (version 3) with the Matplotlib v3.10 and Lifelines v0.30 libraries.

3. Results

The median age of patients included in the study was 64 years. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Surgical resection of the primary tumor was performed in 72.4% of patients. All patients had metastatic disease, with 69% presenting distant metastases at initial diagnosis and 31% owing to relapse after previous radical local treatment. Prior to regorafenib treatment, 34.5% of patients had received more than three lines of therapy. Molecular testing for KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF mutations, as well as microsatellite instability (MSI), were not performed in one patient due to the difficulties in obtaining reliable material. Additionally, 44.8% of patients underwent HER2 expression testing by immunohistochemistry, all with negative results. None of the patients received immunotherapy due to the absence of microsatellite instability.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the studied population.

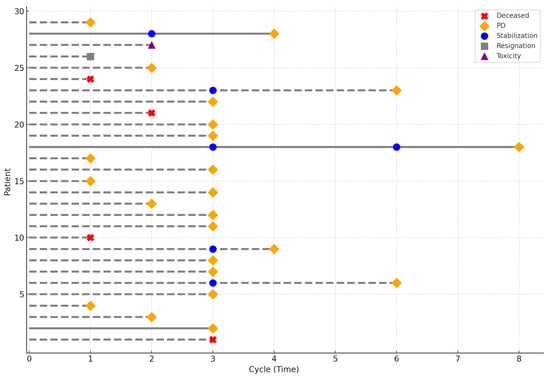

In the study group, seven patients received only one cycle of regorafenib, five received two cycles, twelve received three cycles, and five continued therapy beyond three cycles. Twenty-three patients discontinued treatment due to disease progression, while one patient discontinued due to treatment-related toxicity. Four patients died before disease progression could be confirmed. One patient voluntarily withdrew from treatment. The treatment course is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Characteristics of the treatment course. The symbols indicate the reason for treatment discontinuation for each patient. Solid lines represent patients alive at the last follow-up, whereas dashed lines represent patients who died prior to it.

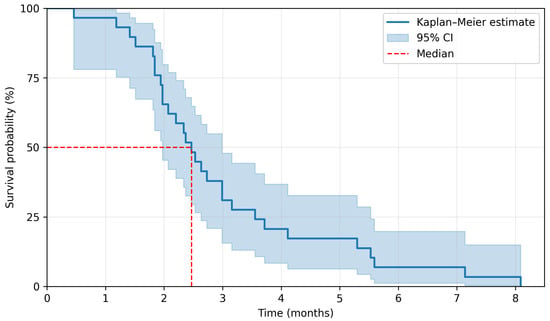

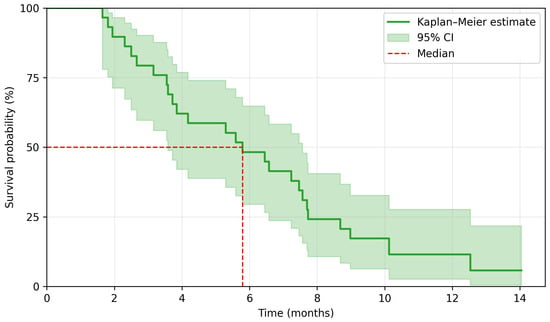

The median duration of regorafenib treatment was 2.8 months. The last follow-up date for survival was 2 January 2025. There were 29 PFS events and 26 OS events. A median PFS (mPFS) was 2.5 months, and a median OS (mOS) was 5.8 months. The 3-month and 6-month PFS rate was 37.9% and 6.9%, respectively, whereas the 6-month and 12-month OS rate was 48.3% and 6.9%. Kaplan–Meier survival curves are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Among 29 patients, 5 achieved disease stabilization as the best response to therapy, there were no partial or complete remissions. The median duration of disease stabilization was 5.6 months. The comparison of our results with the outcomes of the CORRECT trial is presented in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimation for progression-free survival.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier estimation for overall survival.

Table 2.

Comparison of current results with CORRECT Trial results; mPFS—median progression-free survival, mOS—median overall survival, mDoT—median duration of treatment, mDoSD—median duration of stable disease.

4. Discussion

Managing treatment for patients in good performance status who have already received all standard therapies and whose tumors do not exhibit molecular aberrations amenable to targeted therapies is challenging. The CORRECT trial, published in 2013, provided evidence of the efficacy of regorafenib in such patients. In this study, regorafenib was shown to significantly improve OS and PFS compared to placebo. The use of regorafenib reduced the risk of disease progression by 51% (HR 0.49, 95% CI 0.42–0.58; p < 0.0001) and the risk of death by 23% (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.64–0.94; p = 0.0052), extending the median PFS from 1.7 to 1.9 months and the median OS from 5 to 6.4 months. No patients achieved a complete response, while 5 patients receiving regorafenib achieved a partial response. Disease control was observed in 41% of patients, with a median duration of disease stabilization of 2 months compared to 1.7 months in the placebo group. A meta-analysis combining results from the CORRECT trial and three studies conducted in Asian populations [12,13,14] demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in OS (OR = 0.78; 95% CI = 0.65–0.94; p = 0.008) and PFS (OR = 0.52; 95% CI = 0.34–0.79; p = 0.002) compared with the control group [15]. The efficacy and safety of regorafenib have also been supported by European real-world data, including the French compassionate-use REBECCA cohort [16] and the Czech national registry-based analysis [17]. These findings are complemented by the international prospective observational CORRELATE study, which included a substantial number of European centers [18], as well as separate French cohort analysis [19]. Regorafenib was also investigated in the second-line setting in a phase II study that compared FOLFIRI combined with regorafenib versus FOLFIRI alone. The study demonstrated only a slight improvement in PFS (median: 6.1 vs. 5.3 months; HR 0.73, 95% CI = 0.53–1.01; p = 0.056); however, no benefit in OS was observed (HR 1.01, 95% CI = 0.71–1.44) [20]. In the Italian REALITY (GISCAD) study [21], clinical factors potentially identifying patients with a greater likelihood of benefit were explored, with the absence of liver progression and good early tolerability (without dose/schedule modifications) associated with improved outcomes. The patient characteristics in these cohorts appear broadly comparable to those in CORRECT and in our analysis. To the best of our knowledge, Polish centers were not represented in the above-mentioned studies.

The outcomes of the study conducted on the population from Polish oncology centers were comparable to those in the CORRECT trial. However, reliable comparison is not possible, as patients treated in real-word practice usually differ from those treated in controlled clinical trials. In the analyzed group, most patients had a performance status of 1 according to ECOG, compared to the registration trial, where patients with good and very good performance status were more evenly distributed. Additionally, the Polish population had a higher prevalence of rectal cancer—more than half compared to one-third of the CORRECT trial population with this diagnosis. Moreover, 34.5% of patients in the current study received more than three lines of treatment prior to regorafenib, compared to 49% in the 2013 trial. Thus, small numerical differences in mPFS and mOS seem to be negligible. Moreover, the difference in median PFS may be attributed to the timing of treatment response assessments, performed every 8 weeks in the registration trial but every 12 weeks in our study. Differences between the size of populations may also contribute to the observed discrepancies. The potential impact of improved supportive care quality for oncology patients since the time of the registration trial should also be considered.

For patients progressing on regorafenib or after exhausting available treatment options, fruquintinib emerges as a promising option. Approved by the FDA in 2023 [22] and by the EMA in June 2024 [23], fruquintinib is a selective VEGFR 1–3 kinase inhibitor that exerts its antitumor effects by inhibiting tumor angiogenesis. Its efficacy was confirmed in the phase III FRESCO-2 trial [24], a randomized study comparing fruquintinib + best supportive care (BSC) with placebo + BSC. This trial included 691 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer previously treated with standard therapies, including fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin, irinotecan, anti-EGFR agents (for KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF wild-type tumors), anti-VEGF agents, trifluridine/tipiracil, and immunotherapy for MSI-H tumors. Patients were stratified by prior therapy (trifluridine/tipiracil only, regorafenib only, or both), RAS genes status, and metastatic disease duration (≤18 months or >18 months). The primary endpoint was OS, with PFS as a key secondary endpoint. Fruquintinib significantly improved both endpoints, with a mOS of 7.4 months compared to 4.8 months in the placebo group (34% reduction in death risk) and a mPFS of 3.7 months versus 1.8 months (68% reduction in progression or death risk).

Another treatment approach after standard therapies could involve reintroducing previously used regimens [25]. Evidence suggests that irinotecan-based retreatment achieves a disease control rate (DCR) of 78.2%, compared to 57.8% for oxaliplatin retreatment [26,27]. However, oxaliplatin retreatment may not be feasible due to persistent neuropathy from prior therapy. Reintroduction of anti-EGFR agents in unselected patients is considered ineffective [28].

5. Limitations of Our Study

The main limitation of our study is a very small number of patients. This results from the limited availability of regorafenib at that time.

6. Conclusions

This analysis focused on patients who had completed standard treatment. The efficacy of regorafenib was evaluated in a population of Polish patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Despite being a preliminary evaluation based on a small patient cohort our study confirmed the results of the CORRECT trial. Decisions regarding treatment after standard therapies remain challenging and, given the current state of knowledge, should be guided by the anticipated benefits and the side effect profile of available options. Fruquintinib has recently emerged as an additional important therapeutic option. Further comparative studies are necessary to determine the optimal treatment strategies in patients with chemorefractory disease.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by M.G., M.K. and D.R. Figures were prepared by T.K., P.P. and B.R. supervised the study and provided critical revisions of the manuscript. The first draft of the manuscript was written by M.G., and all authors reviewed and commented on previous versions. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive any external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Bioethical Committee at the Medical University of Lodz (RNN/197/25/KE) on 10 June 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

All patients involved in the study provided written informed consent for the use of their anonymized data for publication purposes.

Data Availability Statement

The data and materials used in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| anti-EGFR | anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| anti-VEGF | anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| BSC | Best Supportive Care |

| DCR | Disease Control Rate |

| ECOG | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| ESMO | European Society for Medical Oncology |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| HER2 | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| mDoSD | median Duration of Stable Disease |

| mDoT | median Duration of Treatment |

| mOS | median Overall Survival |

| mPFS | median Progression-Free Survival |

| MSI | Microsatellite Instability |

| MSI-H | Microsatellite Instability-High |

| MSI-L | Microsatellite Instability-Low |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| PFS | Progression-Free Survival |

| RAS | Rat sarcoma |

| VEGFR | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor |

References

- Global Burden of Disease 2019 Cancer Collaboration. Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for 29 Cancer Groups From 2010 to 2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 420–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didkowska, J.; Barańska, K.; Miklewska, M.J.; Wojciechowska, U. Cancer Incidence and Mortality in Poland in 2023. Nowotwory. J. Oncol. 2024, 74, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, A.; Adam, R.; Roselló, S.; Arnold, D.; Normanno, N.; Taïeb, J.; Seligmann, J.; Baere, T.D.; Osterlund, P.; Yoshino, T.; et al. Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashraheel, S.S.; Domling, A.; Goda, S.K. Update on Targeted Cancer Therapies, Single or in Combination, and Their Fine Tuning for Precision Medicine. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 125, 110009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopetz, S.; Grothey, A.; Yaeger, R.; Cutsem, E.V.; Desai, J.; Yoshino, T.; Wasan, H.; Ciardiello, F.; Loupakis, F.; Hong, Y.S.; et al. Encorafenib, Binimetinib, and Cetuximab in BRAF V600E–Mutated Colorectal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1632–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahcene Djaballah, S.; Daniel, F.; Milani, A.; Ricagno, G.; Lonardi, S. HER2 in Colorectal Cancer: The Long and Winding Road From Negative Predictive Factor to Positive Actionable Target. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2022, 42, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakih, M.G.; Salvatore, L.; Esaki, T.; Modest, D.P.; Lopez-Bravo, D.P.; Taieb, J.; Karamouzis, M.V.; Ruiz-Garcia, E.; Kim, T.-W.; Kuboki, Y.; et al. Sotorasib plus Panitumumab in Refractory Colorectal Cancer with Mutated KRAS G12C. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 2125–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaeger, R.; Weiss, J.; Pelster, M.S.; Spira, A.I.; Barve, M.; Ou, S.-H.I.; Leal, T.A.; Bekaii-Saab, T.S.; Paweletz, C.P.; Heavey, G.A.; et al. Adagrasib with or without Cetuximab in Colorectal Cancer with Mutated KRAS G12C. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Ou, Q.; Wu, X.; Nagasaka, M.; Shao, Y.; Ou, S.I.; Yang, Y. NTRK Fusion Positive Colorectal Cancer Is a Unique Subset of CRC with High TMB and Microsatellite Instability. Cancer Med. 2022, 11, 2541–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subbiah, V.; Wolf, J.; Konda, B.; Kang, H.; Spira, A.; Weiss, J.; Takeda, M.; Ohe, Y.; Khan, S.; Ohashi, K.; et al. Tumour-Agnostic Efficacy and Safety of Selpercatinib in Patients with RET Fusion-Positive Solid Tumours Other than Lung or Thyroid Tumours (LIBRETTO-001): A Phase 1/2, Open-Label, Basket Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 1261–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grothey, A.; Cutsem, E.V.; Sobrero, A.; Siena, S.; Falcone, A.; Ychou, M.; Humblet, Y.; Bouché, O.; Mineur, L.; Barone, C.; et al. Regorafenib Monotherapy for Previously Treated Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (CORRECT): An International, Multicentre, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2013, 381, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Qin, S.; Xu, R.; Yau, T.C.C.; Ma, B.; Pan, H.; Xu, J.; Bai, Y.; Chi, Y.; Wang, L.; et al. Regorafenib plus Best Supportive Care versus Placebo plus Best Supportive Care in Asian Patients with Previously Treated Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (CONCUR): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, T.; Komatsu, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Yamazaki, K.; Tsuji, A.; Ura, T.; Grothey, A.; Van Cutsem, E.; Wagner, A.; Cihon, F.; et al. Randomized Phase III Trial of Regorafenib in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Analysis of the CORRECT Japanese and Non-Japanese Subpopulations. Investig. New Drugs 2015, 33, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriwaki, T.; Fukuoka, S.; Taniguchi, H.; Takashima, A.; Kumekawa, Y.; Kajiwara, T.; Yamazaki, K.; Esaki, T.; Makiyama, C.; Denda, T.; et al. Propensity Score Analysis of Regorafenib Versus Trifluridine/Tipiracil in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Refractory to Standard Chemotherapy (REGOTAS): A Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum Multicenter Observational Study. Oncologist 2018, 23, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.-S.; Men, S.-Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, R.-H. A Meta-Analysis of Safety and Efficacy of Regorafenib for Refractory Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Medicine 2018, 97, e12635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenis, A.; de la Fouchardiere, C.; Paule, B.; Burtin, P.; Tougeron, D.; Wallet, J.; Dourthe, L.-M.; Etienne, P.-L.; Mineur, L.; Clisant, S.; et al. Survival, Safety, and Prognostic Factors for Outcome with Regorafenib in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Refractory to Standard Therapies: Results from a Multicenter Study (REBECCA) Nested within a Compassionate Use Program. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novakova-Jiresova, A.; Kopeckova, K.; Boublikova, L.; Chloupkova, R.; Melichar, B.; Petruzelka, L.; Finek, J.; Fiala, O.; Grell, P.; Batko, S.; et al. Regorafenib for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: An Analysis of a Registry-Based Cohort of 555 Patients. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 5365–5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducreux, M.; Petersen, L.N.; Öhler, L.; Bergamo, F.; Metges, J.-P.; de Groot, J.W.; Wang, J.-Y.; García Paredes, B.; Dochy, E.; Fiala-Buskies, S.; et al. Safety and Effectiveness of Regorafenib in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer in Routine Clinical Practice in the Prospective, Observational CORRELATE Study. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 123, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metges, J.-P.; Genet, D.; Tougeron, D.; Ligeza, C.; Ducreux, M.; Borg, C.; Guimbaud, R.; Phelip, J.-M.; Dourthe, L.-M.; Kim, S. Real-World Safety and Effectiveness of Regorafenib in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: The French CORRELATE Cohort. Future Oncol. 2021, 17, 3343–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanoff, H.K.; Goldberg, R.M.; Ivanova, A.; O’Reilly, S.; Kasbari, S.S.; Kim, R.D.; McDermott, R.; Moore, D.T.; Zamboni, W.; Grogan, W.; et al. Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind Phase 2 Trial of FOLFIRI with Regorafenib or Placebo as Second-Line Therapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Cancer 2018, 124, 3118–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, E.; Puzzoni, M.; Ziranu, P.; Cremolini, C.; Lonardi, S.; Banzi, M.; Mariani, S.; Liscia, N.; Cinieri, S.; Dettori, M.; et al. Long Term Survival With Regorafenib: REALITY (Real Life in Italy) Trial—A GISCAD Study. Clin Color. Cancer 2021, 20, e253–e262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; Food and Drug Administration. D.I.S.C.O. Burst Edition: FDA Approval of Fruzaqla (Fruquintinib) for Adult Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer; Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2024.

- Fruzaqla|European Medicines Agency (EMA). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/fruzaqla (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Dasari, A.; Lonardi, S.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Elez, E.; Yoshino, T.; Sobrero, A.; Yao, J.; García-Alfonso, P.; Kocsis, J.; Gracian, A.C.; et al. Fruquintinib versus Placebo in Patients with Refractory Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (FRESCO-2): An International, Multicentre, Randomised, Double-Blind, Phase 3 Study. Lancet 2023, 402, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, A.E.; Frick, J.; Tanner, N.; Gerkin, R.; Kundranda, M.; Dragovich, T. Chemotherapy Re-Challenge Response Rate in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2018, 9, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.K.; Cha, Y.; Baek, J.Y. Retreatment of Irinotecan in Later Lines of Therapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Retrospective Study. Oncology 2021, 99, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatu, A.; Mauri, G.; Tosi, F.; Bencardino, K.; Bonazzina, E.; Gori, V.; Ruggieri, L.; Arena, S.; Bardelli, A.; Marsoni, S.; et al. Efficacy of Retreatment with Oxaliplatin-Based Regimens in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients: The RETROX-CRC Retrospective Study. Cancers 2022, 14, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; George, G.C.; Tsimberidou, A.M.; Naing, A.; Wheler, J.J.; Kopetz, S.; Fu, S.; Piha-Paul, S.A.; Eng, C.; Falchook, G.S.; et al. Retreatment with Anti-EGFR Based Therapies in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Impact of Intervening Time Interval and Prior Anti-EGFR Response. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.