Abstract

Background/Objectives: Liver transplantation is an effective treatment for end-stage liver disease, and patients treated by surgeons with higher service volumes have better therapeutic outcomes. However, few studies have examined the effects of cumulative service volume on the survival of liver transplant patients. The objective of this study was to investigate the effect of a surgeon’s cumulative service volume on the survival rates of liver transplant patients. Methods: The study was a retrospective and nationwide cohort study. Patients who underwent a liver transplant in 2005–2013 were identified. The data were from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database. The primary outcome was the effect of surgeon service volume on 1-year survival after surgery for liver transplant patients. Results: A total of 3233 patients who underwent liver transplantation had a first-year survival rate of 85.8%. The high relative service volume group (>307 cases) had the highest patient survival rate at 1 year after operation (95.31%), while the low relative service volume group (<31 cases) had the lowest survival rate (71.39%). After relevant adjustment variables, the risk of mortality was significantly higher among patients operated on when their surgeons had accumulated fewer than 41 prior transplant cases, and the risk of mortality decreased as the cumulative service volume of surgeons rose. Conclusions: This nationwide cohort study demonstrated an association, rather than a causal relationship, between surgeon cumulative service volume and 1-year survival after liver transplantation. One-year survival reached approximately 85% once surgeons had accumulated 41–60 prior transplant cases. These findings may provide a reference for understanding the clinical learning curve in liver transplantation.

1. Introduction

According to the Taiwanese Ministry of Health and Welfare, in 2016, liver and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma were the second leading cause of malignant tumors, with a mortality rate of 35.5 per 100,000. Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis is the tenth leading cause of death, with a mortality rate of 20.1 per 100,000 [1]. Liver disease is common in Taiwan and liver transplantation is considered the most effective treatment to help end-stage liver disease patients return to normal daily life [2,3,4].

Although liver transplantation can prolong the life of patients with liver disease, according to the Central Health Insurance Department, the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival rates in patients after surgery were only 86%, 78%, and 74%, respectively [5]. In addition, previous studies have reported that some patients develop serious postoperative complications, such as bile leakage, hepatic artery thrombosis, intra-abdominal hemorrhage, organ rejection, and viral infection, resulting in recurrent hospitalization or re-transplantation [6,7], which in turn led to increasing medical costs. Furthermore, bleeding and intraoperative blood transfusion also impact the postoperative survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma [8]. Previous studies have suggested that the cause of bleeding may be associated with the physician’s professional competence and medical experience, both of which are important factors in treatment success [9].

Treatment outcomes are closely associated with surgeon service volume. In 1973, Adams and colleagues conducted the first study on the relationship between physician service volume and treatment outcomes in their analysis of the rates of complications of coronary arteriography [10]. Since then, similar studies have been performed on gastric cancer resection in Taiwan [11], colorectal surgery [12], and bariatric surgery [13] in the United States, as well as an Italian report on results in 26 clinical areas [14]. Most studies have demonstrated that physicians with higher service volume have better treatment outcomes than those with lower service volume [15,16].

According to previous studies, the factors influencing the survival of liver transplant patients include: the service volume of the physician; the patient’s gender, age, education, marital status, and economic and environmental factors, health status and health behavior; the characteristics of the surgical hospital; source of organ donation; and postoperative medication control [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Burroughs et al. studied the effect of physician service volume on European liver transplant patients and showed that the mortality rate of patients in the high service volume group (≥70 cases) was lower at 3 months and 1 year after surgery, compared with patients in the medium service volume group (37–69 cases) and those in the low service volume group (36 cases) [29].

While past studies have focused on physician service volume and treatment outcomes, none have determined the exact number of operations in a year of a surgeon’s service that corresponds with the optimal survival of liver transplant patients. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effect of surgeon service volume (both relative and cumulative) and related factors on patient survival in the first year after liver transplantation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Study Populations

This study was a retrospective cohort study. Data from the National Health Insurance Research Database for 2000–2014 were provided by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, and the Cause of Death Database for 2005–2014 was used to determine the cause of death. In this study, we selected patients who underwent liver transplantation from 2005 to 2013 and were coded 50.5 on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Procedure Coding System (ICD-9-PCS). Patients with two or more liver transplants (39 patients) were excluded, resulting in a total of 3233 patients identified. No organs from executed prisoners were included in this study. The study was approved by the hospital Institutional Review Board (CMUH107-REC3-033; approval date: 27 September 2018), which waived the requirement for informed consent.

2.2. Definition of Relevant Variables

The survival of the patient within 1 year after liver transplantation is influenced by the technique and experience of the surgeon; therefore, previous studies considered whether the patient died within the first year after liver transplantation as a dependent variable [30,31]. In this study, each subject was followed up for 1 year after liver transplantation and was categorized as having died (confirmed in the Cause of Death Data statistical database) or living. The independent variable was the surgeon service volume. Since the National Health Insurance Research Database has been available only since 2000, the amount of surgeon service volume was calculated beginning 1 January 2000. The surgeon service volume was defined as the number of liver transplants performed by the primary operating surgeon since 1 January 2000 up to the time when the patients underwent liver transplants, and included both relative and cumulative service volume. In procedures involving multiple surgeons, surgeon service volume was attributed to the primary surgeon recorded in the National Health Insurance database, as only one surgeon is registered for reimbursement purposes. Relative service volume was divided by quartiles, with low surgeon service volume at ≤25%, medium volume at 25–75%, and high volume at ≥75%. Cumulative service volume was determined by cases as follows: ≤20, 21–40, 41–60, 61–80, 81–100, 101–120, 121–140, 141–160, 161–180, 181–200, 201–230, 231–260, 261–300, 301–400, 401–500, and ≥501 cases, in order to locate the group at which cumulative service volume provided optimal patient survival in the 1-year period after liver transplantation.

Control variables were patient characteristics (gender, age), economic factors (monthly salary), health status (severity of comorbidity), environmental factors (degree of urbanization of the residential area), surgeon characteristics (whether the surgeon changed the practice hospital), surgical hospital characteristics (hospital accreditation level, hospital ownership), and year of operation. Patient age was divided into six groups of <20 years, 20–34 years, 35–44 years, 45–54 years, 55–64 years, and ≥65 years old. Monthly salary was divided into six groups of <564 United States dollars (USD), 564–744 USD, 745–940 USD, 941–1186 USD, 1187–1496 USD, and >1497 USD. Severity of comorbidity was determined by using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), which uses ICD-9-CM codes for 17 diseases to calculate the cumulative comorbidity of patients; it is the most widely used such tool [32]. The primary and secondary diagnoses recorded for the outpatient and inpatient visits for each patient for the two years prior to the liver transplant were converted into numerical scores, the liver-related diagnoses were excluded, and the total score was then calculated as the severity of comorbidity. Codes were calculated and divided into three groups: 0, 1–2, and ≥3. The degree of urbanization of the residential area was used to denote environmental factors. According to Liu et al., in 2006, the 359 townships in Taiwan are divided into seven levels (high degree of urbanization, moderate degree of urbanization, emerging town, general township urban area, old age town, agricultural town, and remote township), as a 7-cluster of urbanization [33].

Other characteristics included whether the surgeon changed the practicing hospital, defined as the surgeon changing the practice hospital within the two years before the liver transplant operation (yes/no). The characteristics of the surgical hospital included hospital accreditation level (medical center or regional hospital) and hospital ownership (public hospital or non-public hospital). The hospital where the patients underwent liver transplant surgery was defined as a surgical hospital for patients. The patients were examined according to year of transplantation (all years from 2005 to 2013, inclusive) to control for potential factors that could not be observed between years.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Log-rank tests were used to perform unadjusted comparisons of survival curves across categories of surgeon service volume (relative and cumulative), patient characteristics, economic factors, health status, environmental factors, surgeon characteristics, surgical hospital characteristics, and year of transplantation, with patient mortality in the 1-year period after liver transplantation. The Cox Proportional Hazard Model was used to investigate the effects of different surgeon service volumes on the mortality of patients at 1 year after liver transplantation and associated risk factors. This study represented statistically significant differences at p < 0.05. Cox survival curves were used to depict the survival curve of patients at 1 year after liver transplant by surgeon service volume, after adjusting for other variables. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) statistics software was used for data processing and statistical analysis.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the distribution of the characteristics of the 3233 study subjects included in the statistical analysis. For relative surgeon service volume by quartile, low surgeon service volume was ≤31 cases, medium volume was 32–306 cases, and high volume was ≥307 cases. In all the 16 Surgeon Cumulative Service Volume categories, most patients were in the lowest volume category, i.e., 619 or 19.15% of all cases. The number of survivors at 1 year after liver transplantation was 2774, or 85.80%; the number of survivors at 3 years was 2595, or 80.27%.

Table 1.

Distribution of Characteristics of the Study Subjects.

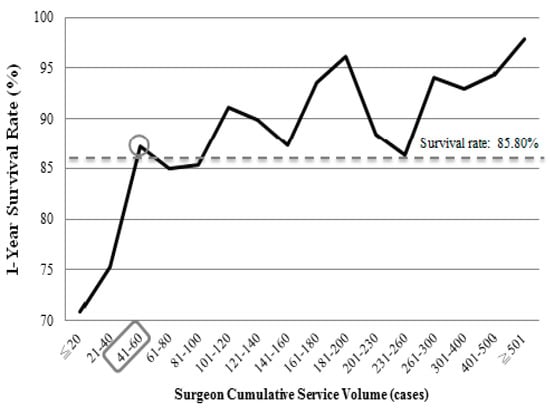

Table 2 shows that surgeon service volume, comorbidity severity, hospital accreditation level, hospital ownership, and year of transplantation were significantly associated with the 1-year survival status of liver transplant patients (p < 0.05). In terms of relative service volume, the higher the surgeon’s service volume, the better the patient’s survival rate at 1 year after the operation. The high service volume group (≥307 cases) had the highest patient survival rate at 1 year after operation (95.31%), while the low service volume group (≤31 cases) had the lowest (71.39%). We further analyzed cumulative service volume. When the cumulative service volume of surgeons was ≤20 cases, the 1-year survival rate of liver transplant patients was 70.92%; for a cumulative service volume of 21–40 cases, the 1-year survival rate was 75.31%. When the surgeon’s cumulative service volume was 41–60 cases, the 1-year survival rate was 87.15%. After this point, the survival rate of liver transplant patients remained stable and gradually increased. The 1-year survival rates of patients with surgeons with a cumulative service volume of ≥60 cases were higher than those with 41–60 cases, as shown in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Bivariate analysis of factors associated with 1-year survival status of liver transplant patients.

Figure 1.

Survival rates of the patients within 1 year after liver transplantation according to surgeon cumulative service volume from 2005–2013.

In terms of comorbidity severity, patients with higher comorbidity scores had lower rates of 1-year survival. Patients with a CCI score of 0 had the highest 1-year survival rate (88.59%), while those with a CCI score of ≥3 had the lowest (82.82%). In terms of hospital accreditation, patients treated at a medical center (86.01%) had a higher 1-year survival rate than those treated at a regional hospital (78.72%). For hospital ownership, patients at non-public hospitals had a greater 1-year survival rate (86.67%) than patients at public hospitals (83.93%). For year of transplantation, survival rates increased each year. In 2006, the 1-year survival rate was the lowest, 77.62%, and in 2013, 90.34% was the highest. However, survival rates did not differ by patient gender, age, monthly salary, urbanization of residence area, or whether the surgeon changed the practice hospital (p > 0.05).

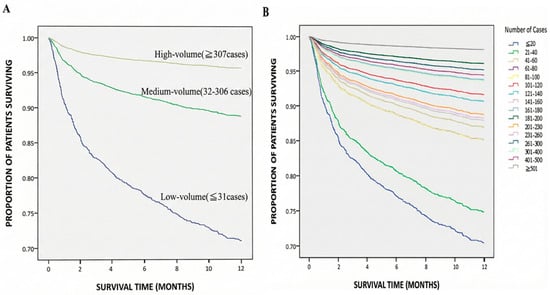

After adjusting for the relevant variables, we looked at which variables were associated with risk of mortality at 1 year (Table 3). Both surgeon service volume and comorbidity severity were significantly associated with the risk of mortality in patients 1 year after liver transplantation (p < 0.05). Figure 2 shows the 1-year patient survival curve after liver transplantation from 2005–2013 for patients according to surgeon relative service volume and surgeon cumulative service volume, respectively.

Table 3.

Effects and associated risk factors of different surgeon service volumes on mortality of patients 1 year after liver transplantation.

Figure 2.

The survival curves of the patients within 1 year after liver transplantation from 2005 to 2013 based on (A) surgeon relative service volume (medium volume: HR 0.35, 95% CI 0.28–0.43; high volume: HR 0.13, 95% CI 0.09–0.19; both p < 0.001) and (B) surgeon cumulative service volume.

In terms of surgeon service volume, surgeons were divided into the low, medium and high group by the number of liver transplants performed. Using the lowest quartile group (≤31 cases) as the reference group (Adjusted Model 1, Table 3), we found that patients treated when surgeons’ accumulated service volume fell into the middle group (32–306 cases) or the high group (≥307 case) had statistically significantly lower risk of mortality, with hazard ratio (HR) values of 0.35 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.28–0.43; p < 0.001) and 0.13 (95% CI: 0.09–0.19; p < 0.001), respectively.

We further focused on the number of liver transplants performed by the surgeon, measured as the cumulative service volume. When this study used ≤20 cases (lowest) of cumulative surgeon service as the reference group (Adjusted Model 2, Table 3), the risk of mortality of liver transplant patients decreased as the cumulative service volume of surgeons rose, especially the cumulative service volume higher than 40 cases (p < 0.001). This result confirmed that the survival of patients with liver transplants improved and remained steadily better once the cumulative service volume of surgeons reaches 41–60 cases (Table 3).

In terms of severity of comorbidity, with CCI = 0 as the reference group, the risk of mortality in liver transplant patients rose, as did the comorbidity score. For example, the risk of mortality in liver transplant patients with CCI ≥ 3 was 1.54-fold (95% CI: 1.14–2.08) higher than that of those with CCI of 0 (p = 0.005). However, other variables had no effect on 1-year mortality (p > 0.05). Patients who received a liver transplant from a surgeon who did not change the practice hospital had a lower risk of mortality than those whose surgeon did change hospitals within two years before surgery (HR = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.24–2.50), but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.668).

4. Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the higher the surgeon’s service volume, the lower the risk of mortality in patients 1 year after liver transplantation. In a previous US study that divided the number of liver transplants performed by surgeons in a given year into low (<3 cases), medium (3–9 cases) and high (>9 cases), service volume was significantly associated with postoperative mortality and length of hospitalization. The postoperative mortality rate was 3.21-fold higher in the low service group than in the high service group, and the postoperative mortality rate was 2.81-fold greater in the medium service group than in the high service group [34]. Their results were consistent with the findings in our study. In the study by Burroughs et al., the number of cases of liver transplantation performed in Europe from 1988 to 2003 was collected; the mortality rate was measured at 3 months and 1 year after surgery, and the service volume was divided into three groups: high (≥70 cases), medium (37–69 cases) and low (≤36 cases). The patients in the high service volume group had the lowest mortality rates at 3 months and 1 year after surgery [29]. Their finding also corresponded with our study. In addition, both US and Taiwanese studies found that surgeons with higher service volume of organ transplants have better postoperative outcomes than those with lower service volume. The result may be related to the skill or experience of the surgeon [35,36,37,38,39].

In the past, many studies of physician service volume and treatment outcomes have divided the physician service volume into low (≤25%), medium (25–75%), and high (≥75%). In terms of service volume, relative volume may be less important than the cumulative service volume of the physician. We assumed that the cumulative service volume of the surgeon could well be the critical factor influencing the survival of patients within 1 year after liver transplantation. In this study, analysis of the surgeon service volume included both relative and cumulative service volume. At first, we analyzed the results of surgeons with 5 or 10 cases per group, but the 1-year survival rate of the patients was inconsistent. We then extended the cumulative service volume to 20 cases per group, and the survival rate of the patients was relatively steady after the surgery. Therefore, we analyzed the cumulative service volume of surgeons treating 200 cases or fewer by groups of 20 cases. Our results showed that when the cumulative service volume of surgeons reached 41–60 cases, the 1-year survival rate of liver transplant patients was 87.15%, which was higher than the overall 1-year survival rate of 85.80%. The 1-year survival rate of liver transplant patients increased as the surgeon service volume rose beyond 41–60 cases. Therefore, when the surgeon’s cumulative service volume reaches 41–60 cases, the surgeon’s liver transplant technique may be established enough to maximize their patients’ likelihood of the survival.

Among the variables influencing the survival of patients 1 year after liver transplantation, severity of comorbidity was also analyzed in a previous study in Taiwan of 1876 liver transplant patients. The researchers found that patients with hepatitis C after liver transplantation had higher rates of complications of diabetes mellitus and lower survival rates [40]. A previous US study suggested that the risk of postoperative transplantation failure in liver transplant patients with comorbidity scores CCI ≥ 6 was 3.95-fold higher than that of liver transplant patients with CCI scores < 6 [41]. In addition, the study of Pischke et al. in Germany tracked the 15-year survival of 114 patients with liver transplants and found higher rates of mortality and transplant failure in patients with BMI ≥ 24 kg/m2 compared to those with BMI < 24 kg/m2 [42]. Diseases such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and obesity can lead to cardiovascular disease, which is a significant factor for mortality in liver transplant patients [22]. The above studies all indicate that patients with poor health status and more comorbidities before liver transplantation have a higher risk of postoperative mortality. Their findings were consistent with the results of our study.

The medical team performing the liver transplant surgery is also a very important factor in determining treatment outcomes after surgery. However, no research has yet been conducted on this factor. We analyzed the effect on patient survival of surgeons changing their medical team (by moving to another hospital) in the 2 years prior to the surgery. The results showed that patients of surgeons who did not change their hospitals had a lower risk of mortality than patients of those who did (HR = 0.77, p = 0.668), but the difference was not statistically significant. This result may be due to the small number of patients whose surgeons did change their hospitals; only eight patients received surgery from five surgeons who had changed their practice hospital.

In order to control for the potential factors that may not be observed in each year that affect patient survival after liver transplantation, we analyzed the effect of the year of transplantation. The results of the study showed that, in the multivariate analysis (Cox Proportional Hazard Model), the risk of mortality was higher but not significantly different in patients at 1 year after liver transplantation in 2006 and 2007 (p > 0.05). In the log-rank test, the survival rate of patients who underwent liver transplantation in 2006 and 2007 was significantly lower (p < 0.05), or 77.62% and 79.53%, respectively. One reason may be that the guidelines for the standard tumor size of liver transplant after 2006 changed from the Milan criteria (Milan guidelines) to the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) criteria (University of California, San Francisco, USA) which reduced the restrictions on liver transplantation. For example, for a single liver cancer tumor, the size changed from <5 cm to <6.5 cm; in the case of multiple liver cancer tumors, the number and size of tumors was adjusted from more than 3 and <3 cm to <4.5 cm with the total tumor diameter less than 8 cm. The change in liver transplant standards and guidelines made liver transplantation available to more liver cancer patients, but it may also have had the effect of causing transplantation to occur in sicker patients, who were at increased risk of recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma and death.

In summary, this study was the first to examine surgeon cumulative service volume in liver transplantation at a population level and to describe its association with 1-year post-transplant survival as a representation of the surgical learning curve. The results demonstrated that 1-year survival after liver transplantation tended to increase with higher surgeon service volume (relative volume). When surgeons had accumulated approximately 41–60 liver transplant cases, patient 1-year survival reached approximately 85% and became more stable.

It should be emphasized that these findings demonstrate an association rather than a causal relationship, and the observed service volume range should not be interpreted as a definitive threshold or prescriptive standard. Given the retrospective design and the use of an administrative database, the results should be viewed as descriptive and hypothesis-generating.

Accordingly, the clinical relevance of this study lies in providing population-level evidence that may complement existing clinical risk assessments and facilitate further discussion regarding the role of surgeon experience in liver transplantation outcomes. Before any policy-level recommendations or structural modifications to transplant programs are considered, further studies incorporating comprehensive clinical registries, center-level adjustment, and advanced statistical modeling are warranted.

5. Limitation

This study has several limitations. First, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was used to represent baseline health status; however, it may not fully reflect the acute physiological severity of liver transplant candidates. Second, the database covered the period from 2005–2013 and may not entirely represent current transplantation practices, although the volume–outcome relationship is likely to remain valid over time. Third, information on graft source (living or deceased donor) was unavailable, but both types are reimbursed under the same procedural code and follow similar management in Taiwan’s National Health Insurance system, minimizing potential bias. Finally, several clinical and graft-related factors—including MELD score, portal hypertension, hepatocellular carcinoma, organ function, and graft-to-recipient ratio—were not recorded, and inter-institutional heterogeneity could not be fully adjusted. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the association between surgeon service volume and patient survival.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: L.-Y.C., T.-W.W. and W.-C.T.; Methodology: L.-Y.C., T.-W.W. and P.-T.K.; Validation: P.-T.K. and W.-C.T.; Formal analysis: L.-Y.C. and T.-W.W.; Investigation: L.-Y.C.; Data curation: T.-W.W.; Writing—original draft: L.-Y.C. and T.-W.W.; Writing—review and editing: P.-T.K. and W.-C.T.; Visualization: L.-Y.C.; Supervision: W.-C.T.; Project administration: W.-C.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the grant (CMU112-MF-92) from the China Medical University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of China Medical University Hospital (CMUH107-REC3-033; approval date: 27 September 2018). The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the use of de-identified secondary data.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because the study used de-identified secondary data from the National Health Insurance Research Database and the Cause of Death Database, and individual consent was not required according to the regulations of the Institutional Review Board of China Medical University Hospital.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available from the National Health Insurance Research Database and the Cause of Death Database, Taiwan. Access to these databases is restricted and requires approval from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for use of the National Health Insurance Research Database and the Cause of Death Database provided by Statistic Center of Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCI | Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| MELD | Model for End-Stage Liver Disease |

References

- Taiwanese Ministry of Health and Welfare. Statistics on the Cause of Death of Taiwanese People 2017; Taiwanese Ministry of Health and Welfare: Taipei City, Taiwan, 2017.

- Finkenstedt, A.; Nachbaur, K.; Zoller, H. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: Excellent outcomes after liver transplantation but high mortality on the wait list. Liver Transplant. 2013, 19, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rattanasiri, S.; McDaniel, D.O.; McEvoy, M. The association between cytokine gene polymorphisms and graft rejection in liver transplantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transpl. Immunol. 2013, 28, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sannananja, B.; Seyal, A.R.; Baheti, A.D. Tricky Findings in Liver Transplant Imaging: A Review of Pitfalls with Solutions. Curr. Probl. Diagn. Radiol. 2017, 47, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health Insurance Administration. The National Health Insurance Administration Has Released Four Postoperative Survival Indicators for Organ Transplant Patients. Available online: https://www.nhi.gov.tw/ch/cp-7585-27ad4-3255-1.html (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Levitsky, J.; Cohen, S.M. The liver transplant recipient: What you need to know for long-term care. J. Fam. Pract. 2006, 55, 136–144. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.M.; Xu, X.; Zheng, S.S. Hepatitis B virus reinfection after liver transplantation: Related risk factors and perspective. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2005, 4, 502–508. [Google Scholar]

- Pol, B.; Campan, P.; Hardwigsen, J. Morbidity of major hepatic resections: A 100-case prospective study. Eur. J. Surg. 1999, 165, 446–453. [Google Scholar]

- Hillner, B.E.; Smith, T.J.; Desch, C.E. Hospital and physician volume or specialization and outcomes in cancer treatment: Importance in quality of cancer care. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 18, 2327–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.F.; Fraser, D.B.; Abrams, H.L. The Complications of Coronary Arteriography. Circulation 1973, 48, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xirasagar, S.; Lien, Y.C.; Lin, H.C. Procedure volume of gastric cancer resections versus 5-year survival. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2008, 34, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archampong, D.; Borowski, D.; Wille-Jørgensen, P. Workload and surgeon’s specialty for outcome after colorectal cancer surgery. Cochrane Libr. 2012, 14, CD005391. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.D.; Patterson, E.; Wahed, A.S. Relationship between surgeon volume and adverse outcomes after RYGB in Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) study. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2010, 6, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, L.; Colais, P.; Davoli, M. Volume and health outcomes: Evidence from systematic reviews and from evaluation of Italian hospital data. Epidemiol. Prev. 2013, 37, 1–100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luft, H.S. Hospital Volume, Physician Volume, and Patient Outcome: Assessing the Evidence; Health Administration Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Waldman, J.D.; Yourstone, S.A.; Smith, H.L. Learning curves in health care. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, R.; Cailliez, V.; Majno, P. Normalised intrinsic mortality risk in liver transplantation: European Liver Transplant Registry study. Lancet 2000, 356, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axelrod, D.A.; Guidinger, M.K.; McCullough, K.P. Association of center volume with outcome after liver and kidney transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2004, 4, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busuttil, R.W.; Lake, J.R. Role of tacrolimus in the evolution of liver transplantation. Transplantation 2004, 77, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, M.; Herrero, J.I.; Quiroga, J. De novo neoplasia after liver transplantation: An analysis of risk factors and influence on survival. Liver Transplant. 2005, 11, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Z.; Wu, J.; Smart, G. Survival analysis of liver transplant patients in Canada 1997–2002. Transplant. Proc. 2006, 38, 2951–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.; Hong, J.C.; Saab, S. Cardiovascular risk factors following orthotopic liver transplantation: Predisposing factors, incidence and management. Liver Int. 2010, 30, 948–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozhathil, D.K.; Li, Y.F.; Smith, J.K. Impact of center volume on outcomes of increased-risk liver transplants. Liver Transplant. 2011, 17, 1191–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnetta, M.J.; Xing, M.; Zhang, D. The effect of bridging locoregional therapy and Sociodemographics on survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation: A united network for organ sharing population study. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2016, 27, 1822–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.H.; Yoon, Y.I.; Song, G.W. Living Donor Liver Transplantation for Patients Older Than Age 70 Years: A Single-Center Experience. Am. J. Transplant. 2017, 17, 2890–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Huang, R. Prognostic value of marital status on stage at diagnosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Pu, L.; Gao, W. Influence of marital status on the survival of adults with extrahepatic/intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 28959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, P.A.; Hervás, M.D.; García, C.A. Outcomes in patients with diabetes 10 years after liver transplantation. J. Diabetes 2017, 9, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burroughs, A.K.; Sabin, C.A.; Rolles, K. 3-month and 12-month mortality after first liver transplant in adults in Europe: Predictive models for outcome. Lancet 2006, 367, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanWagner, L.B.; Ning, H.; Whitsett, M. A point-based prediction model for cardiovascular risk in orthotopic liver transplantation: The Carolt score. Hepatology 2017, 66, 1968–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, T.K.; Thomas, K.A.; Ladner, D.P. Incidence and Risk Factors of Intracranial Hemorrhage in Liver Transplant Recipients. Transplantation 2018, 102, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyo, R.A.; Cherkin, D.C.; Ciol, M.A. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1992, 45, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Y.; Hung, Y.T.; Chuang, Y.L. Incorporating Development Stratification of Taiwan Townships into Sampling Design of Large Scale Health Interview Survey. J. Health Manag. 2006, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough, J.E.; Pietrobon, R.; Tuttle-Newhall, J.E. Relationship between provider volume and outcomes for orthotopic liver transplantation. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2008, 12, 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, S.F.; Chu, C.C.; Chien, C.C. Renal transplantation: Relationship between hospital/surgeon volume and postoperative severe sepsis/graft-failure. A nationwide population-based study. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 11, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Dhar, V.K.; Wima, K. The center volume–outcome effect in pancreas transplantation: A national analysis. J. Surg. Res. 2017, 213, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer, J.D.; Putter, H.; Blok, J.J.; Alwayn, I.P.J.; van Hoek, B.; Braat, A.E. Predictive Capacity of Risk Models in Liver Transplantation. Transpl. Direct 2019, 5, e457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Ryu, H.G. Impact of institutional case volume of solid organ transplantation on patient outcomes and implications for healthcare policy in Korea. Korean J. Transpl. 2023, 37, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniyappan, N.; Peach, E.; Pearce, F.; Dhaliwal, A.; Campos-Varela, I.; Cant, M.R.; Dopazo, C.; Trotter, J.; Divani-Patel, S.; Hatta, A.A.; et al. Long-term outcomes (beyond 5 years) of liver transplant recipients—A transatlantic multicenter study. Liver Transplant. 2024, 30, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.W.; Kung, Y.T.; Chang, W.T. Risk Factors Analysis for New-Onset Diabetes Mellitus after Liver Transplantation—A National Population Based Study in Taiwan. Med. J. South Taiwan 2016, 12, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Petrowsky, H.; Rana, A.; Kaldas, F.M. Liver transplantation in highest acuity recipients: Identifying factors to avoid futility. Ann. Surg. 2014, 259, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pischke, S.; Lege, M.C.; von Wulffen, M. Factors associated with long-term survival after liver transplantation: A retrospective cohort study. World J. Hepatol. 2017, 9, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.