Abstract

Primary humoral immunodeficiencies are a heterogeneous group of disorders defined by quantitative and/or functional defects in one or more immunoglobulin classes, often with associated cellular immune abnormalities. Their link with bronchiectasis, whose prevalence varies across specific defects, is largely driven by recurrent respiratory infections. Selective Immunoglobulin-(Ig)A deficiency and IgG2 subclass deficiency are the most frequent forms, but common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is the condition most often associated with bronchiectasis and is usually diagnosed earlier because of its characteristic phenotype. In contrast, the contribution of isolated IgA deficiency or selective IgG subclass deficiencies to bronchiectasis remains controversial. Other reported associations include X-linked agammaglobulinemia, selective IgM or IgG deficiency, and rarer entities such as selective IgE deficiency, unclassified hypogammaglobulinemia, specific antibody deficiency, specific polysaccharide antibody deficiency, and heavy- or light-chain deficiencies. Current bronchiectasis guidelines recommend measurement of serum immunoglobulins and IgG subclasses in patients with compatible features, recurrent infections, or no clear etiology before labeling disease as idiopathic. Identifying immunoglobulin defects is clinically important because they represent treatable traits. The potential role of emerging therapies such as the DPP1 inhibitor brensocatib in immunodeficiency-related bronchiectasis remains uncertain, and ongoing registries will be key to clarifying these relationships.

1. Introduction

Primary humoral immunodeficiencies (PHI) constitute a heterogeneous group of immune disorders characterized by a quantitative deficiency or functional impairment of antibodies (immunoglobulins). This defect affects the respiratory system in various ways, depending on the specific disorder and other contributing factors [1].

Various organizations maintain registries of immunodeficiencies, including humoral types, such as ESID (European Society for Immunodeficiencies) [2], USIDNET (US Immunodeficiency Network Registry) [3], and IUIS (International Union of Immunological Societies), which defines, classifies, and standardizes the nomenclature and diagnostic criteria of these diseases [4]. Numerous smaller national or regional registries also exist. The IUIS classifies humoral immunodeficiencies into four main groups, shown in Table 1 [4,5].

Table 1.

Predominantly antibody deficiencies according to the definition of IUIS (modified from [5]).

The prevalence of PHI depends on patient age and the specific type of immunodeficiency. It is estimated that 1 in 1000–2000 individuals in the general population are affected, with lower prevalence in adults (1 in 25,000–50,000). Diagnostic delays are common due to low clinical suspicion, subclinical or late-onset symptoms, or misattribution of symptoms to chronic diseases, medications, or procedures [1].

Immunoglobulin-(Ig)A deficiency is the most common PHI, affecting 1 in 200–500 individuals [6], followed by common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) (1 in 25,000–50,000) [7], IgG subclasses deficiency (1 in 500–2000) [8], and IgM deficiency (1 in 100,000–200,000) [9]. A reduced immunoglobulin production or function compromises immunity, particularly against encapsulated bacteria [1].

Abnormal immunoglobulin values are generally those that fall outside the mean ±2 standard deviations of the general population [10]. Normal adult immunoglobulin ranges are: IgA: 70–400 mg/dL (0.7–4 g/L); IgM: 40–230 mg/dL (0.4–2.3 g/L); IgG: 700–1600 mg/dL (7–16 g/L); IgG subclasses: (IgG1: 430–1050 mg/dL; IgG2: 250–650 mg/dL; IgG3: 50–200 mg/dL and IgG4: 30–150 mg/dL) [10].

IgG is the most abundant immunoglobulin, with IgG1–IgG4 representing ~60–70%, 20–30%, 5–8%, and 1–4% of total IgG, respectively [11]. Although isolated IgG subclass deficiencies are rare (<1%), combined deficiencies are even less common. These deficiencies can increase susceptibility to respiratory and upper airway infections, particularly those caused by encapsulated bacteria. Table 2 summarizes the main role and consequence of the deficiency of the different immunoglobulins [12,13,14].

Table 2.

Immunoglobulins: function and consequences of deficiency [12,13,14].

Certain immunodeficiencies, such as CVID and X-linked agammaglobulinemia (Bruton’s disease), involve both humoral and cellular components and are associated with severe infections from early childhood. CVID, for example, is characterized by poor response to polysaccharide vaccines (e.g., Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae) [6,15].

This narrative review focuses on the relationship between common PHI and the development of non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (hereafter referred to as bronchiectasis).

2. Methods

In general, the existing scientific evidence regarding the association between different types of humoral immunodeficiencies and bronchiectasis is very limited. A systematic literature review was conducted using the PubMed and Embase databases, employing the following terms in the title: (Immunodeficiency OR IgA OR IgA1 OR IgA2 OR IgG OR IgM OR IgG subclasses OR IgG1 OR IgG2 OR IgG3 OR IgG4 OR Combined immunoglobulin OR Common variable immunodeficiency OR CVID OR immunoglobulin OR humoral immunodeficiency OR agammaglobulinemia OR Bruton)* AND in the title or abstract: (Bronchiectasis OR bronchial infection). Regarding clinical studies, only those conducted in adult populations were included in the analysis (PubMed filter: Adults 19+ years).

A total of 138 manuscripts were identified. Two authors of the present study (GSC and MAMG) independently screened the manuscripts, and any discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The majority of the identified papers were case reports or referred to the detection of Aspergillus sp. or Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections through immunoglobulin assays.

After the screening process, 45 manuscripts were included in the final review. Among these, the most frequently studied humoral immunodeficiencies were isolated or combined IgG subclass deficiencies (16 manuscripts), CVID (10), IgA deficiency (4), and agammaglobulinemia (4). Fewer than four manuscripts addressed IgG deficiency, combined immune defects, and hyper-IgM syndrome. Additionally, five manuscripts discussed immunoglobulin replacement therapy in relation to these syndromes.

Of all the manuscripts reviewed, the term “bronchiectasis” appeared explicitly in 11 papers, usually in reference to IgG subclass deficiencies.

3. Humoral Immunodeficiencies and Bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis refers to dilations—typically irreversible—of the bronchial tree, which are commonly accompanied by bronchial wall thickening as an indirect marker of inflammation [16]. This inflammation, to varying degrees, impairs local defense mechanisms such as the mucociliary system, increasing susceptibility to infections by pathogenic bacteria. These infections, in turn, further exacerbate bronchial inflammation, creating a vicious cycle of infection and inflammation that drives the progression of the disease. Most of the currently available pharmacological treatments are aimed at interrupting this cycle [17].

An important point is that, according to a recent global consensus, a true diagnosis of bronchiectasis refers to radiological images of bronchial dilatation accompanied by compatible symptoms—such as chronic productive cough with a purulent component and a history of infective-type exacerbations, and not imaging alone [16].

Bronchiectasis can be caused by more than one hundred different pulmonary and extrapulmonary conditions. Among the most frequent etiologies are post-infectious bronchiectasis (including post-tuberculosis forms), as well as those associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma [18]. Beyond these common causes, there are dozens of other etiologies, each accounting for a smaller proportion of cases (typically less than 5%). These fewer common etiologies may nonetheless present with distinctive clinical features [19].

A diagnosis of idiopathic bronchiectasis—or more accurately, bronchiectasis of unknown etiology—should only be made after a thorough clinical history is obtained and all appropriate complementary investigations have been performed and returned negative [20,21]. In this regard, current international guidelines for the diagnosis and management of bronchiectasis recommend serum immunoglobulin evaluation in all patients, in order to rule out humoral immunodeficiency [19,22,23,24].

Among the well-established causes of bronchiectasis are immunodeficiencies, particularly humoral immunodeficiencies [21]. Table 3 presents the proportion of immunodeficiencies among all patients with bronchiectasis, as reported in national and international registries, as well as in large-scale studies focused on the etiology of bronchiectasis. In most cases, these studies do not distinguish between humoral and cellular immunodeficiencies, grouping them under the broader term of primary immunodeficiencies. Based on the total number of patients included in these studies and the partial percentages reported, it can be estimated that approximately 4–5% of bronchiectasis cases are attributable to primary immunodeficiencies [25]. Only Martínez-García et al. differentiated PHI from the rest (secondary and cellular immunodeficiencies), observing that the vast majority (4.2% vs. 0.5%) were PHI, from which we can infer that the same is likely to occur in most of the other studies [25,26].

The reported prevalence of PHI in large bronchiectasis cohorts varies considerably, ranging from 9% in the study by Olveira et al. [26] to less than 1% in data from India [27]. In the United States, the prevalence is approximately 5% [28], while in Europe it is similar overall (4.1%), though with notable geographic variation [29]. For example, in southern Europe, the prevalence is less than half that reported in south-eastern and western Europe (Table 3). On the other hand, a cohort from Colombia including 161 patients, showed that immune disorders were among the main causes of bronchiectasis, represented by autoimmunity (13.6%) and immunodeficiency (11.7%), especially in individuals under 50 years of age [30].

Several factors may contribute to these differences. The most likely explanation is under diagnosis, due to low clinical suspicion and the limited use of appropriate diagnostic tests, which results in an overall reduction in identified cases. Additionally, many studies do not differentiate between humoral, cellular, and secondary immunodeficiencies, which affects the accuracy of reported percentages. Genetic, socioeconomic, and environmental factors may also play a role. Humoral immunodeficiencies are frequently caused by genetic defects or mutations, which may be more prevalent in regions with higher rates of consanguinity, where cultural practices promote marriage among close relatives [21]. Finally, some studies may include a disproportionately high number of patients from immunodeficiency referral centers, artificially inflating the relative percentage of immunodeficiency-related bronchiectasis. This phenomenon is clearly illustrated in the comparison between two Spanish registries. In the earlier registry [26], a single center contributed over 200 patients with immunodeficiencies, resulting in a relatively high prevalence of over 9%. In contrast, the more recent registry which did not include data from that center, reported a prevalence of immunodeficiencies less than half that of the previous study [25].

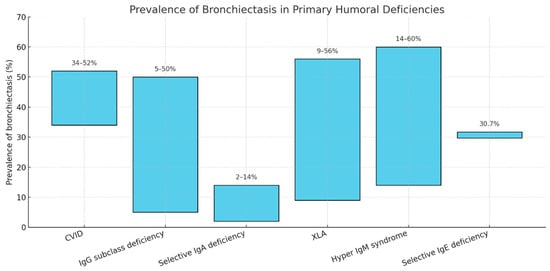

The most frequent PHIs will be described below. The estimated prevalence of bronchiectasis among them is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Prevalence ranges of bronchiectasis according to the different primary humoral immunoglobulin deficiencies. CVID: Common Variable Immunodeficiency; X-linked Agammaglobulinemia.

Combined immunodeficiencies with syndromic features, such as STAT3-related hyper-IgE syndrome and DOCK8 deficiency, may also result in bronchiectasis [5,31]; however, as they are not classified as predominantly antibody deficiencies, they lie outside the scope of this review and will not be discussed further.

Table 3.

Prevalence of primary humoral immunodeficiencies in large series of bronchiectasis series.

Table 3.

Prevalence of primary humoral immunodeficiencies in large series of bronchiectasis series.

| Study | Country | Year | n° | ID% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lonni et al. [32] | 6 European countries | 2015 | 1258 | 5.8% |

| Aksamit et al. [28] | US | 2017 | 1775 | 5% |

| Olveira et al. [26] | Spain | 2017 | 2047 | 9.4% |

| Henkle et al. [33] | US Medicare | 2018 | 175,572 | 3.5% * |

| Dhar et al. [27] | India | 2019 | 2195 | <1% |

| Visser et al. [34] | Australia | 2019 | 566 | 3.7% |

| Huang et al. [35] | Taiwan | 2020 | 15,729 | 1.3% |

| Martínez-Garcia et al. [25] | Spain | 2021 | 1912 | 4.2% |

| Yu et al. [36] | South Korea | 2022 | 931 | 2.8 * |

| Chalmers et al. [29] | Europe | 2023 | 16,963 | 4.1% |

| -UK | -- | -- | 8163 | 2.5% |

| -North/West | -- | -- | 4295 | 6% |

| -South | -- | -- | 3444 | 6.1% |

| -Central/East | -- | -- | 1061 | 2.7% |

| Edis et al. [37] | Turkey | 2024 | 1035 | 1.3% |

| Ibrahim et al. [38] | Qatar | 2024 | 284 | 3.5% |

| Zea-Vera et al. [30] | Colombia | 2024 | 161 | 11.7% |

| Burgel et al. [39] | France | 2025 | 630 | 3.5% |

| Xu et al. [40] | China | 2025 | 9501 | 0.3% |

ID: Immunodeficiency; US: United States; UK: United Kingdom. * Also includes allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, primary ciliary dyskinesia and others.

3.1. IgG Subclass Deficiencies

Although the existing literature remains limited, the thresholds of normality for defining an IgG subclass deficiency are established when one or more subclass levels are found to be two standard deviations below the age-adjusted range in patients with normal total serum IgG levels [10,11]. A persistent controversy remains regarding whether certain isolated or combined subclass deficiencies may in fact cause bronchiectasis as a consequence of recurrent respiratory infections associated with such deficiencies. The classic data supporting this notion date back to the 1990s and the beginning of the 21st century. Popa et al. reported that among 42 adults with some degree of IgG subclass deficiency and multiple acute bronchial exacerbations, there was a greater degree of chronic airflow obstruction [41]. In turn, Hill et al. proposed that, owing to the lack of consensus in defining IgG subclass deficiencies, true plasma deficits are rare, and that the pulmonary manifestations are more likely to reflect bronchial rather than systemic subclass deficiencies, which they assessed through measurement of subclass concentrations in sputum [42].

Two studies from a Spanish research group further elucidated this possible association. Thus, De Gracia et al. observed, in a cohort of 65 patients, that within the subgroup of individuals with bronchiectasis of unknown origin (defined as those cases remaining without an identified etiology despite an exhaustive diagnostic workup), thirty-one patients (48%) exhibited low serum concentrations of one or more IgG subclasses (19 IgG2 deficiencies, 2 IgG3 deficiencies, 3 IgG4 deficiencies, and 7 combined subclass deficiencies). Although this finding did not establish causality, it did highlight that the prevalence of IgG subclass deficiency was greater in this group of idiopathic bronchiectasis than in the general population, thereby justifying the inclusion of subclass determination in the diagnostic evaluation prior to classifying bronchiectasis as idiopathic [43].

Rodrigo et al. advanced this line of investigation with a study of 107 patients with bronchiectasis, hypothesizing that even in the presence of normal total IgG or subclass concentrations, a functional deficit might exist. To test this hypothesis, they evaluated the antibody response to a pneumococcal unconjugated vaccine and a Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine. They observed a deficient response in 11% of patients, particularly among those with reduced IgG2 levels, suggesting that IgG2 deficiency or dysfunction may be the most relevant in relation to bronchiectasis. This notion is supported by the known role of IgG2 in the immune response to capsular bacterial polysaccharides, precisely those most frequently implicated in bronchiectasis (Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Haemophilus influenzae) [44]. Similar results were obtained by Martínez-García et al. in a cohort of 128 patients with idiopathic bronchiectasis, with a mean age of 71.6 years, where 12.5% presented at least one subclass deficiency, the most frequent being IgG2 [45].

By contrast, other studies, such as that of Drogu et al., reported that the presence of bronchiectasis in cases of selective IgG subclass deficiency is an uncommon finding in adults over 18 years. In their retrospective series of 270 patients, 96 had an IgG subclass deficiency, yet bronchiectasis was present in only 19 of them (10.4%), in comparison with other humoral immunodeficiencies. However, in the subgroup with combined IgG2 + IgG4 deficiency, prevalence was higher (30.8%), although the number of patients was very small [46].

In 2022, Zhang et al. confirmed prior observations by demonstrating that IgG2 deficiency—the most frequent subclass deficiency—was the one most closely associated with the development of bronchiectasis. Serum IgG2 levels were stratified into tertiles (<2.68 g/L, 2.68–3.53 g/L, and 3.54–4.45 g/L). Independent predictors of three or more exacerbations included: hospital admission within the preceding two years, colonization with potentially pathogenic organisms, asthma, and reduced IgG2 levels. Patients in the lower two tertiles (<2.68 g/L and 2.68–3.53 g/L) experienced a worse progression of bronchiectasis, as assessed by the Bronchiectasis Severity Index over one year, compared with those who were normal IgG2 (>4.45 g/L) (p = 0.013) [47].

It is therefore of paramount importance to recognize, in patients with recurrent infections and bronchiectasis, that either quantitative or functional IgG subclass deficiency (particularly of IgG2) may be associated with the presence of bronchiectasis, even when total IgG levels are within the normal range, before labeling the disease as idiopathic. Furthermore, and of greatest clinical relevance, is the fact that IgG or IgG subclass deficiencies represent a “treatable trait,” since the use of intravenous or subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement therapy may lead to a clinically meaningful reduction in respiratory infections and prevent progressive decline in lung function [48].

3.2. Common Variable Immunodeficiency (CVID)

CVID are the most frequent symptomatic primary immunodeficiencies diagnosed in adulthood, and presents as a heterogeneous condition characterized by hypogammaglobulinemia (especially IgG, IgA and/or IgM), poor antibody response to vaccinations and recurrent upper and/or lower airway infections, as well as several other systemic manifestations, ranging from autoimmunity to lymphoproliferative disorders [49,50]. One of the most common features of CVID is their respiratory system involvement, which can present as bronchiectasis related to the infection-inflammation-tissue damage vicious cycle, or as immune-mediated interstitial lung disease [51]. Different studies have estimated that bronchiectasis is present in around 34–52% of patients with idiopathic hypogammaglobulinemia and CVID [52,53,54,55,56], although in some cohorts, pulmonary lymphoproliferative granulomatous disease are the main causes of morbidity and mortality in patients with CVID [56]. On the other hand, immunodeficiencies account for the main cause of bronchiectasis in approximately 1–9.4% of the cases in different bronchiectasis registries [18]. These registries, however, often do not differentiate between the specific conditions causing the immunodeficiency, so the true prevalence of CVID among bronchiectasis patients is hard to establish.

A study by Buso et al. observed that patients with CVID and bronchiectasis have a significantly lower forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) compared to those without bronchiectasis [53]. This finding was also observed in another study by Sperlich et al., where the authors identified a more rapid FEV1 decline in CVID individuals with bronchiectasis [54]. Furthermore, the presence of bronchiectasis in CVID was associated with a higher rate of annual respiratory infections and worse quality of life [54]. On the other hand, this same study observed that lower serum IgM levels were associated with a higher risk of developing bronchiectasis and a higher number of annual respiratory infections [54]. In this regard, a meta-analysis by Ramzi et al. also observed that CVID patients with bronchiectasis had significantly lower levels of serum IgA and IgM, and a higher frequency of pneumonias, sinus infections, otitis media and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia [55]. Similar results were observed in an analysis of 1470 CVID patients included in the USIDNET registry, were lower serum IgA levels, chronic rhino sinusitis, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and interstitial lung disease (ILD) were independently associated with the development of bronchiectasis [57]. In summary, these findings highlight the significant negative clinical impact of the association of CVID and bronchiectasis.

Although, in general, it was considered that the presence of bronchiectasis did not impact mortality in CVID patients, a more recent study showed that higher bronchiectasis severity score at diagnosis, as well as chronic bronchial infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, low FEV1 and the overlap with COPD do have an independent association with an increased mortality [58]. Moreover, a specific analysis of a New Zealand CVID cohort showed that early-onset disease and delayed diagnosis was associated with an increased risk of bronchiectasis as well as with premature death [59].

Immunoglobulin reposition is one of the main pillars of CVID treatment, which can help to obtain respiratory infections control. Due to this specific treatment option, the measurement of serum immunoglobulins is recommended in all bronchiectasis patients, as mentioned previously [19,22]. The efficacy of this treatment in subjects with CVID, however, may be influenced by the presence of bronchiectasis, as the required reposition dose is higher and time to achieve target IgG levels, and therefore, time to infection frequency control, takes longer in this subgroup of patients [60,61]. Nevertheless, a study by Pereira et al. observed that immunoglobulin treatment in patients with CVID and bronchiectasis managed to significantly improve airway inflammatory markers, as well as the mucus transportability by cough [62]. Another key treatment in patients with bronchiectasis is daily airway clearance through physiotherapy. In this regard, a study by Thickett et al. observed that despite the high prevalence of bronchiectasis among a cohort of CVID patients, only few patients had received instructions in airway clearance techniques [63]. These differences manifest the need to increase awareness efforts for early diagnosis and treatment of both CVID and bronchiectasis among clinicians.

3.3. IgA Deficiency

Selective IgA deficiency is the most common immunodeficiency [12]. Both IgA1 and IgA2 subclasses increase locally in the presence of local inflammation/infection or purulent sputum, particularly IgA2 [12,64]. Subjects with IgA deficiency may remain asymptomatic or present with bacterial infections (mainly due to encapsulated bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae) as well as non-bacterial infections of the respiratory tract and upper airways. IgA deficiency is also associated with certain autoimmune diseases and is frequently combined with other humoral deficiencies [65].

Regarding its relationship with bronchiectasis, results remain heterogeneous. For instance, Hodkinson et al., in a study of 626 patients with primary immunodeficiency, observed that 48% of those with combined IgA and IgM deficiency developed bronchiectasis, even though a high proportion of them were already receiving IgG replacement therapy. Among the limitations of this study was the inclusion of all types of humoral immunodeficiencies, such as CVID and X-linked agammaglobulinemia [66].

In contrast, Aghamohammadi et al. studied 37 patients with IgA deficiency and found that only 4 developed bronchiectasis, although many displayed atopic disorders. In 50% of cases, IgA deficiency was associated with other humoral deficits, particularly IgG subclass deficiency, whether quantitative or functional. Patients with this combined defect experienced a higher frequency of bronchial infections and bronchiectasis [67].

On the other hand, Domingue et al. evaluated 330 patients with selective IgA deficiency and found that although a high proportion suffered from recurrent respiratory tract infections, atopy, and certain autoimmune diseases, bronchiectasis was documented in only 6 patients. This very small percentage is likely explained by the fact that only patients younger than 18 years were included, meaning that recurrent respiratory tract infections had not yet had sufficient time to induce the development of bronchiectasis [68].

At present, no replacement therapy exists for IgA deficiency. However, several animal model trials have yielded promising results. Vonarburg et al., using a murine model, demonstrated the feasibility of topically applying human plasma-derived immunoglobulins into the lungs through a nebulized liquid formulation, which successfully prevented acute respiratory infection [69].

3.4. X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia (XLA)

XLA is a primary immunodeficiency caused by different mutations in the gene encoding Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK), which alter B-cell development. Since the BTK gene is located on the X chromosome, the disease almost exclusively affects males [70]. Agammaglobulinemia is defined by recurrent infections before 5 years of age, IgG serum levels <500 mg/dL, IgA and IgM levels <2 standard deviations below the mean for age, and <2% circulating B cells [71].

XLA is rare, with a prevalence of 0.3 per 100,000 male births in the United Kingdom, representing 4% of patients in the UK Primary Immunodeficiency Registry [72]. Symptoms usually begin in infancy, with a median onset age of 8–12 months, and a median age at diagnosis of 48–60 months [73,74]. The most frequent clinical manifestations are pneumonia, otitis media, and diarrhea [73,74]. The prevalence of bronchiectasis in XLA varies by cohort, ranging from 10% to 44% [73,75].

Bronchiectasis is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in XLA, and its presence is associated with a faster decline in FEV1 than in CVID [76]. Immunoglobulin replacement is the main treatment; however, many patients continue to have recurrent infections, progressive lung damage, and reduced quality of life despite higher IgG doses [77,78,79]. Patients with XLA and bronchiectasis can continue to show lung disease progression even with adequate IgG replacement therapy [78]. Respiratory failure is one of the most frequent causes of death in these patients [75].

There is a need to investigate the mechanisms regulating inflammation in XLA to improve therapeutic strategies and optimize outcomes.

3.5. Other Primary Humoral Immunodeficiencies

Although there is little information, other types of PHI may be associated with bronchiectasis.

3.5.1. Hyper-IgM Syndrome (HIGM)

HIGM is a primary immune disorder in which the patient has normal or elevated IgM levels but very low or absent levels of the other main immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, and sometimes IgE) [13]. The most common form is X-linked, caused by mutations in the CD40L gene in T lymphocytes, although there are other genetic variants. The defect lies in class-switch recombination, where B lymphocytes switch from producing IgM to other antibody classes. Treatment is based on IgG replacement therapy.

In a cross-sectional study, Moazzami et al. reported that, among 62 patients with HIGM, more than 50% had pneumonia and 14.1% had bronchiectasis [80].

3.5.2. Selective IgE Deficiency

This is a very rare primary humoral immunodeficiency characterized by markedly reduced serum IgE concentrations, with preservation of the levels of the other immunoglobulin isotypes [81]. The available literature on this condition remains scarce. Picado et al., in a retrospective study of 52 adults, observed that a considerable number of patients presented with autoimmune diseases, but also that a significant proportion exhibited an increased frequency and severity of respiratory tract infections, both upper and lower, such as chronic bronchitis (34.6%), pneumonia (30.7%), and even bronchiectasis (30.7%) [82].

3.5.3. Extremely Rare Forms

Other very rare PHI variants include unclassified hypogammaglobulinemia, specific antibody deficiency (SPAD), specific polysaccharide antibody deficiency (SAD) and heavy- and light-chain deficiencies. These conditions have not been associated with bronchiectasis in the literature but are associated with recurrent respiratory infections, which favor the development of bronchiectasis [2].

4. Future Directions

The growing recognition of PHI as a relevant etiology of bronchiectasis contrasts sharply with the limited, often heterogeneous evidence base that currently guides clinical practice in this setting. Future research must therefore prioritize robust, prospective characterization of patients with bronchiectasis and PHI, including precise immunological phenotyping, longitudinal assessment of lung function and exacerbation burden, and detailed microbiological profiling. Such work should clarify which specific defects (for example, IgG2 deficiency, combined subclass deficiencies, or CVID) carry the greatest risk of developing bronchiectasis and of progression once established, and at what time-points immunoglobulin replacement and other interventions have the greatest preventive impact.

Regarding new therapeutic approaches, emerging treatments such as dipeptidyl peptidase 1 (DPP1) inhibitors, along with other anti-inflammatory and host-directed strategies, have been tested almost exclusively in populations without overt immunodeficiency [83,84]. The strict exclusion of patients with PHI from most phase II and III bronchiectasis trials leaves a major evidence gap: the efficacy, safety, optimal dosing, and risk–benefit balance of these agents in individuals with underlying antibody defects remain essentially unknown. As a result, clinicians need to extrapolate experiences from non-immunodeficient cohorts or to withhold potentially beneficial therapies from a group with particularly high morbidity. Future clinical trials should explicitly address this limitation by either including carefully phenotyped PHI subgroups with pre-specified stratified analyses, or by designing dedicated studies focused on immunodeficiency-associated bronchiectasis. Pragmatic trials and well-controlled observational studies, nested within large registries, may offer a feasible intermediate step where traditional randomized designs are challenging.

National and international registries will be central to these efforts. Existing immunodeficiency registries (such as ESID and USIDNET) and bronchiectasis registries, such as EMBARC (Europe) and RIBRON (Spain), among others, already capture complementary aspects of these conditions, but are rarely integrated. Linking or harmonizing these datasets would allow a more accurate estimation of the true prevalence of bronchiectasis across PHI subtypes, better description of natural history, and more granular evaluation of outcomes according to immunoglobulin replacement strategy, airway clearance practices, chronic antibiotic use, and exposure to newer therapies such as DPP1 inhibition. Importantly, registries can facilitate post-marketing surveillance of off-label or early-access use of novel bronchiectasis treatments in patients with PHI, providing real-world safety and effectiveness data that are unlikely to be obtained promptly through trials alone.

Furthermore, systematic measurement of serum immunoglobulins and IgG subclasses in all adults with bronchiectasis of unknown cause, as recommended by current guidelines, remains inconsistent in routine practice. Education of respiratory physicians, immunologists, and primary care clinicians to recognize PHI as a “treatable trait” in bronchiectasis, and to refer patients early to specialized centers, is essential. Ultimately, the convergence of biologically informed phenotyping, inclusive trial design, and high-quality registry data offers the most promising route towards genuinely personalized care for patients with bronchiectasis and PHI.

5. Conclusions

There is a wide spectrum of primary humoral immunodeficiencies that, to varying degrees, predispose to recurrent respiratory infections and consequently increase the likelihood of developing bronchiectasis (Figure 1). Among these, common variable immunodeficiency—given its combination of multiple humoral and cellular defects—appears to be the condition most strongly associated with bronchiectasis. The question of whether isolated or combined deficiencies can directly lead to bronchiectasis remains under debate; however, current evidence suggests that IgG2 deficiency, in particular, shows a stronger association.

The clinical relevance of selective or combined IgG deficiencies lies in the fact that they represent a treatable trait in bronchiectasis, as highly effective replacement therapies are available. Large-scale studies, leveraging existing international and national registries of primary humoral immunodeficiencies, are needed to clarify the precise relationship between these disorders and the pathogenesis and impact of bronchiectasis. In the meantime, in any patient with bronchiectasis not attributable to other causes and preceded by recurrent respiratory infections, it is essential to rule out quantitative or functional immunoglobulin deficiencies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S.-C. and M.Á.M.-G.; methodology, G.S.-C. and M.Á.M.-G.; writing—draft preparation, G.S.-C.; C.L.; J.D.G.-O.; G.O. and M.Á.M.-G.; writing—review and editing, G.S.-C.; C.L.; J.D.G.-O.; G.O. and M.Á.M.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This manuscript received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the elaboration of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PHI | Primary Humoral Immunodeficiency |

| ESID | European Society for Immunodeficiencies |

| USIDNET | United States Immunodeficiency Network Registry |

| IUIS | International Union of Immunological Societies |

| Ig | Immunoglobulin |

| CVID | Common Variable Immunodeficiency |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| XLA | X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia |

| HIGM | Hyper IgM Syndrome |

| DPP1 | Dipeptidyl peptidase 1 |

References

- Meyts, I.; Bousfiha, A.; Duff, C.; Singh, S.; Lau, Y.L.; Condino-Neto, A.; Bezrodnik, L.; Ali, A.; Adeli, M.; Drabwell, J. Primary Immunodeficiencies: A Decade of Progress and a Promising Future. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 625753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Society for Immunodeficiencies. Available online: https://esid.org/ (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- The United States Immunodeficiency Network. Available online: https://usidnet.org/ (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- International Union of Immunological Societies. Available online: https://iuis.org/ (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Poli, M.C.; Aksentijevich, I.; Bousfiha, A.A.; Cunningham-Rundles, C.; Hambleton, S.; Klein, C.; Morio, T.; Picard, C.; Puel, A.; Rezaei, N.; et al. Human Inborn Errors of Immunity: 2024 Update on the Classification from the International Union of Immunological Societies Expert Committee. J. Hum. Immun. 2025, 1, e20250003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latiff, A.H.A.; Kerr, M.A. The Clinical Significance of Immunoglobulin A Deficiency. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2007, 44, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, R.; Habibi, S.; Sharifi, L.; Azizi, G.; Abolhassani, H.; Olbrich, P.; Aghamohammadi, A. Common Variable Immunodeficiency: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, Classification, and Management. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 30, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferis, R.; Kumararatne, D.S. Selective IgG Subclass Deficiency: Quantification and Clinical Relevance. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1990, 81, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taietti, I.; Votto, M.; De Filippo, M.; Naso, M.; Montagna, L.; Montagna, D.; Licari, A.; Marseglia, G.L.; Castagnoli, R. Selective IgM Deficiency: Evidence, Controversies, and Gaps. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.R.; Chaker, L.; Ikram, M.A.; Peeters, R.P.; van Hagen, P.M.; Dalm, V.A.S.H. Determinants and Reference Ranges of Serum Immunoglobulins in Middle-Aged and Elderly Individuals: A Population-Based Study. J. Clin. Immunol. 2021, 41, 1902–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Z.; Wen, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, S.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y. Adult Reference Intervals for IgG Subclasses with Siemens Immunonephelometric Assays in Chinese Population. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2017, 13, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.; Selmi, C.; Gershwin, M.E.; Teuber, S.S. The Clinical Implications of Selective IgA Deficiency. J. Transl. Autoimmun. 2019, 2, 100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Gupta, A. Selective IgM Deficiency-An Underestimated Primary Immunodeficiency. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidarsson, G.; Dekkers, G.; Rispens, T. IgG Subclasses and Allotypes: From Structure to Effector Functions. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, D.; Groth, D.; Wright, H.; Bonilla, F.A.; Fuleihan, R.L.; Cunningham-Rundles, C.; Sullivan, K.E.; Ochs, H.D.; Marsh, R.; Feuille, E. X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia: Infection Frequency and Infection-Related Mortality in the USIDNET Registry. J. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 42, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliberti, S.; Goeminne, P.C.; O’Donnell, A.E.; Aksamit, T.R.; Al-Jahdali, H.; Barker, A.F.; Blasi, F.; Boersma, W.G.; Crichton, M.L.; De Soyza, A.; et al. Criteria and Definitions for the Radiological and Clinical Diagnosis of Bronchiectasis in Adults for Use in Clinical Trials: International Consensus Recommendations. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuschillo, S.; De Felice, A.; Balzano, G. Mucosal Inflammation in Idiopathic Bronchiectasis: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms. Eur. Respir. J. 2008, 31, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Olivas, J.D.; Oscullo, G.; Martínez-García, M.Á. Etiology of Bronchiectasis in the World: Data from the Published National and International Registries. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.D.; Haworth, C.S.; Flume, P.; Long, M.B.; Burgel, P.R.; Dimakou, K.; Blasi, F.; Herrero-Cortina, B.; Dhar, R.; Chotirmall, S.H.; et al. European Respiratory Society Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Adult Bronchiectasis. Eur. Respir. J. 2025, 66, 2501126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, M.Á.; Máiz, L.; Olveira, C.; Girón, R.M.; de la Rosa, D.; Blanco, M.; Cantón, R.; Vendrell, M.; Polverino, E.; de Gracia, J.; et al. Spanish Guidelines on Treatment of Bronchiectasis in Adults. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2018, 54, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McShane, P.J. Common Variable Immunodeficiency and Other Immunodeficiency Syndromes in Bronchiectasis. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 42, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, M.Á.; Máiz, L.; Olveira, C.; Girón, R.M.; de la Rosa, D.; Blanco, M.; Cantón, R.; Vendrell, M.; Polverino, E.; de Gracia, J.; et al. Spanish Guidelines on the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Bronchiectasis in Adults. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2018, 54, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, A.T.; Sullivan, A.L.; Chalmers, J.D.; De Soyza, A.; Stuart Elborn, J.; Andres Floto, R.; Grillo, L.; Gruffydd-Jones, K.; Harvey, A.; Haworth, C.S.; et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for Bronchiectasis in Adults. Thorax 2019, 74, 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.C.; Athanazio, R.A.; de Dalcin, P.T.R.; de Figueiredo, M.R.F.; Gomes, M.; de Freitas, C.G.; Ludgren, F.; Paschoal, I.A.; Rached, S.Z.; Maurici, R. Brazilian Consensus on Non-Cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis. J. Bras. De Pneumol. 2019, 45, e20190122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-García, M.A.; Villa, C.; Dobarganes, Y.; Girón, R.; Maíz, L.; García-Clemente, M.; Sibila, O.; Golpe, R.; Rodríguez, J.; Barreiro, E.; et al. RIBRON: The Spanish Online Bronchiectasis Registry. Characterization of the First 1912 Patients. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2021, 57, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olveira, C.; Padilla, A.; Martínez-García, M.-Á.; de la Rosa, D.; Girón, R.-M.; Vendrell, M.; Máiz, L.; Borderías, L.; Polverino, E.; Martínez-Moragón, E.; et al. Etiology of Bronchiectasis in a Cohort of 2047 Patients. An Analysis of the Spanish Historical Bronchiectasis Registry. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2017, 53, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhar, R.; Singh, S.; Talwar, D.; Mohan, M.; Tripathi, S.K.; Swarnakar, R.; Trivedi, S.; Rajagopala, S.; D’Souza, G.; Padmanabhan, A.; et al. Bronchiectasis in India: Results from the European Multicentre Bronchiectasis Audit and Research Collaboration (EMBARC) and Respiratory Research Network of India Registry. Lancet Glob. Health. 2019, 7, e1269–e1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksamit, T.R.; O’Donnell, A.E.; Barker, A.; Olivier, K.N.; Winthrop, K.L.; Daniels, M.L.A.; Johnson, M.; Eden, E.; Griffith, D.; Knowles, M.; et al. Adult Patients with Bronchiectasis: A First Look at the US Bronchiectasis Research Registry. Chest 2017, 151, 982–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.D.; Polverino, E.; Crichton, M.L.; Ringshausen, F.C.; De Soyza, A.; Vendrell, M.; Burgel, P.R.; Haworth, C.S.; Loebinger, M.R.; Dimakou, K.; et al. Bronchiectasis in Europe: Data on Disease Characteristics from the European Bronchiectasis Registry (EMBARC). Lancet Respir. Med. 2023, 11, 637–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zea-Vera, A.F.; Rodríguez, C.A.; Giraldo, S.; Chacón, M.A.; Guerrero, L.F.; Mosquera, R.; Vallejo, R.A.; Vargas, F.S.; García, M.A.; Rengifo, M.A.; et al. Infections, Autoimmunity and Immunodeficiencies Are the Leading Etiologies of Non-Cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis in Adults from the Southwest of Colombia. Biomedica 2024, 44, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A.F.; Olivier, K.N. Hyper-IgE Syndromes and the Lung. Clin. Chest Med. 2016, 37, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonni, S.; Chalmers, J.D.; Goeminne, P.C.; McDonnell, M.J.; Dimakou, K.; De Soyza, A.; Polverino, E.; Van de Kerkhove, C.; Rutherford, R.; Davison, J.; et al. Etiology of Non-Cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis in Adults and Its Correlation to Disease Severity. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2015, 12, 1764–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkle, E.; Chan, B.; Curtis, J.R.; Aksamit, T.R.; Daley, C.L.; Winthrop, K.L. Characteristics and Health-Care Utilization History of Patients with Bronchiectasis in US Medicare Enrollees with Prescription Drug Plans, 2006 to 2014. Chest 2018, 154, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, S.K.; Bye, P.T.P.; Fox, G.J.; Burr, L.D.; Chang, A.B.; Holmes-Liew, C.L.; King, P.; Middleton, P.G.; Maguire, G.P.; Smith, D.; et al. Australian Adults with Bronchiectasis: The First Report from the Australian Bronchiectasis Registry. Respir. Med. 2019, 155, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Y.; Chung, F.T.; Lo, C.Y.; Lin, H.C.; Huang, Y.T.; Yeh, C.H.; Lin, C.W.; Huang, Y.C.; Wang, C.H. Etiology and Characteristics of Patients with Bronchiectasis in Taiwan: A Cohort Study from 2002 to 2016. BMC Pulm. Med. 2020, 20, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, I.; Yong, S.J.; Lee, W.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, H.; Na, J.O.; Kim, D.K.; Oh, Y.M.; Lee, J.H. Prevalence of Chronic Rhinosinusitis and Its Relating Factors in Patients with Bronchiectasis: Findings from KMBARC Registry. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edis, E.Ç.; Çilli, A.; Kızılırmak, D.; Coşkun, A.Ş.; Güler, N.; Çiçek, S.; Sevinç, C.; Ağca, M.Ç.; Gülmez, İ.; Çağlayan, B.; et al. Bronchiectasis in Türkiye: Data from a Multicenter Registry (Turkish Adult Bronchiectasis Database). Balk. Med. J. 2024, 41, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, T.; Thomas, M.; Rasheed, I.; Mobayed, H.; Sattar, H.A.; Al-Khal, A.; Al-Nesf, M. Etiology of Bronchiectasis in Qatar: A Retrospective Study. Qatar Med. J. 2024, 2024, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgel, P.R.; Bergeron, A.; Maitre, B.; Andrejak, C.; Audoly, C.; Boitiaux, J.F.; Camara, B.; Coolen-Allou, N.; Douvry, B.; Chatté, G.; et al. Bronchiectasis in France: Data on Disease Characteristics in 630 Patients from the European Bronchiectasis Registry (EMBARC). Respir. Med. Res. 2025, 88, 101199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.F.; Zheng, H.Z.; Lu, H.W.; Wang, L.W.; Wu, B.; Lv, X.D.; Luo, H.; Feng, J.; Li, Y.Y.; Liu, L.; et al. Baseline Characteristics of Patients in the Chinese Bronchiectasis Registry (BE-China): A Multicentre Prospective Cohort Study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2025, 13, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, V. Airway Obstruction in Adults with Recurrent Respiratory Infections and IgG Deficiency. Chest 1994, 105, 1066–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.L.; Mitchell, J.L.; Burnett, D.; Stockley, R.A. IgG Subclasses in the Serum and Sputum from Patients with Bronchiectasis. Thorax 1998, 53, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Gracia, J.; Rodrigo, M.J.; Morell, F.; Vendrell, M.; Miravitlles, M.; Cruz, M.J.; Codina, R.; Bofill, J.M. IgG Subclass Deficiencies Associated with Bronchiectasis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1996, 153, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, M.J.; Vendrell, M.; Cruz, M.J.; Miravitlles, M.; Pascual, C.; Morell, F.; De Gracia, J. Utility of the Antibody Response to a Conjugated Haemophilus Influenzae Type B Vaccine for Diagnosis of Primary Humoral Immunodeficiency. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000, 162, 1462–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, M.Á.; Román-Sánchez, P.; Perpiñá-Tordera, M.; Soler-Cataluña, J.J.; Saura-Vinuesa, A.; Yago, M.; Pastor, M.J. Bronchiectasis in the Elderly. Study of Serum Levels of Immunoglobulin G Subclasses. Med. Clin. 2007, 129, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogru, D.; Dogru, Y.; Atschekzei, F.; Elsayed, A.; Dubrowinskaja, N.; Ernst, D.; Witte, T.; Gödecke, V.; Sogkas, G. Reappraisal of IgG Subclass Deficiencies: A Retrospective Comparative Cohort Study. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1552513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Clarke, A.; Regan, K.H.; Campbell, K.; Donaldson, S.; Crowe, J.; Rossi, A.G.; Hill, A.T. Isolated IgG2 Deficiency Is an Independent Risk Factor for Exacerbations in Bronchiectasis. QJM Int. J. Med. 2022, 115, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolles, S.; Orange, J.S.; Gardulf, A.; Stein, M.R.; Shapiro, R.; Borte, M.; Berger, M. Current Treatment Options with Immunoglobulin G for the Individualization of Care in Patients with Primary Immunodeficiency Disease. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2015, 179, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.K.; Gereige, J.D.; Maglione, P.J. State-of-the-Art Diagnostic Evaluation of Common Variable Immunodeficiency. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021, 127, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, M.G.; Kindle, G.; Gathmann, B.; Quinti, I.; Buckland, M.; van Montfrans, J.; Scheible, R.; Rusch, S.; Gasteiger, L.M.; Grimbacher, B.; et al. The European Society for Immunodeficiencies (ESID) Registry Working Definitions for the Clinical Diagnosis of Inborn Errors of Immunity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 1763–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinetto, F.; Scarpa, R.; Rattazzi, M.; Agostini, C. The Broad Spectrum of Lung Diseases in Primary Antibody Deficiencies. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2018, 27, 180019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brent, J.; Guzman, D.; Bangs, C.; Grimbacher, B.; Fayolle, C.; Huissoon, A.; Bethune, C.; Thomas, M.; Patel, S.; Jolles, S.; et al. Clinical and Laboratory Correlates of Lung Disease and Cancer in Adults with Idiopathic Hypogammaglobulinaemia. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2016, 184, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buso, H.; Firinu, D.; Gambier, R.F.; Scarpa, R.; Garzi, G.; Soccodato, V.; Costanzo, G.; Ledda, A.G.; Rashidy, N.; Bertozzi, I.; et al. Lung Function Trajectories in Common Variable Immunodeficiencies: An Observational Retrospective Multicenter Study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2024, 155, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperlich, J.M.; Grimbacher, B.; Soetedjo, V.; Workman, S.; Burns, S.O.; Lowe, D.M.; Hurst, J.R. Predictive Factors for and Complications of Bronchiectasis in Common Variable Immunodeficiency Disorders. J. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 42, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzi, N.; Jamee, M.; Bakhtiyari, M.; Rafiemanesh, H.; Zainaldain, H.; Tavakol, M.; Rezaei, A.; Kalvandi, M.; Zian, Z.; Mohammadi, H.; et al. Bronchiectasis in Common Variable Immunodeficiency: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.L.; Paolini, M.V.; Fernández Romero, D.S. Lung Disease in Patients with Common Variable Immunodeficiency. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2020, 48, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Jimenez, O.; Restrepo-Gualteros, S.; Nino, G.; Cunningham-Rundles, C.; Sullivan, K.E.; Fuleihan, R.L.; Gutierrez, M.J. Respiratory Comorbidities Associated with Bronchiectasis in Patients with Common Variable Immunodeficiency in the USIDNET Registry. J. Clin. Immunol. 2023, 43, 2208–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periselneris, J.; Schelenz, S.; Loebinger, M.; Macedo, P.; Adhya, Z.; Armstrong-James, D.; Kelleher, W.P. Bronchiectasis Severity Correlates with Outcome in Patients with Primary Antibody Deficiency. Thorax 2021, 76, 1036–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameratunga, R.; Jordan, A.; Cavadino, A.; Ameratunga, S.; Hills, T.; Steele, R.; Hurst, M.; McGettigan, B.; Chua, I.; Brewerton, M.; et al. Bronchiectasis Is Associated with Delayed Diagnosis and Adverse Outcomes in the New Zealand Common Variable Immunodeficiency Disorders Cohort Study. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2021, 204, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onalan, T.; Colkesen, F.; Kilinc, M.; Aykan, F.S.; Evcen, R.; Akkus, F.A.; Ergun, U.Y.; Kahraman, S.; Gerek, M.E.; Arslan, S. Relationships between Bronchiectasis and Time to Achieving Target Trough Immunoglobulin G Levels in Patients with Common Variable Immunodeficiency. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2024, 45, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gracia, J.; Vendrell, M.; Álvarez, A.; Pallisa, E.; Rodrigo, M.J.; De La Rosa, D.; Mata, F.; Andreu, J.; Morell, F. Immunoglobulin Therapy to Control Lung Damage in Patients with Common Variable Immunodeficiency. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2004, 4, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.C.; Kokron, C.M.; Romagnolo, B.M.S.; Yagi, C.S.A.; Saldiva, P.H.N.; Filho, G.L.; Negri, E.M. Analysis of the Sputum and Inflammatory Alterations of the Airways in Patients with Common Variable Immunodeficiency and Bronchiectasis. Clinics 2009, 64, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thickett, K.M.; Kumararatne, D.S.; Banerjee, A.K.; Dudley, R.; Stableforth, D.E. Common Variable Immune Deficiency: Respiratory Manifestations, Pulmonary Function and High-resolution CT Scan Findings. QJM Int. J. Med. 2002, 95, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, Y.; Sánchez-Montalvo, A.; Hox, V.; Froidure, A.; Pilette, C. IgA-Producing B Cells in Lung Homeostasis and Disease. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1117749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosughimotlagh, A.; Rasouli, S.E.; Rafiemanesh, H.; Safarirad, M.; Sharifinejad, N.; Madanipour, A.; Dos Santos Vilela, M.M.; Heropolitańska-Pliszka, E.; Azizi, G. Clinical Manifestation for Immunoglobulin A Deficiency: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2023, 19, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodkinson, J.P.; Bangs, C.; Wartenberg-Demand, A.; Bauhofer, A.; Langohr, P.; Buckland, M.S.; Guzman, D.; Yong, P.F.K.; Kiani-Alikhan, S. Low IgA and IgM Is Associated with a Higher Prevalence of Bronchiectasis in Primary Antibody Deficiency. J. Clin. Immunol. 2017, 37, 329–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamohammadi, A.; Cheraghi, T.; Gharagozlou, M.; Movahedi, M.; Rezaei, N.; Yeganeh, M.; Parvaneh, N.; Abolhassani, H.; Pourpak, Z.; Moin, M. IgA Deficiency: Correlation between Clinical and Immunological Phenotypes. J. Clin. Immunol. 2009, 29, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez, O.; Giner, M.T.; Alsina, L.; Martín, M.A.; Lozano, J.; Plaza, A.M. Clinical Phenotypes Associated with Selective IgA Deficiency: A Review of 330 Cases and a Proposed Follow-up Protocol. An. Pediatr. 2012, 76, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vonarburg, C.; Loetscher, M.; Spycher, M.O.; Kropf, A.; Illi, M.; Salmon, S.; Roberts, S.; Steinfuehrer, K.; Campbell, I.; Koernig, S.; et al. Topical Application of Nebulized Human IgG, IgA and IgAM in the Lungs of Rats and Non-Human Primates. Respir. Res. 2019, 20, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas-Morales, M.; Hernandez-Trujillo, V.P. Agammaglobulinemia: From X-Linked to Autosomal Forms of Disease. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 63, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Tapia, E.; García-García, E.; Herrera-González, N.E.; Yamazaki-Nakashimada, M.A.; Staines-Boone, A.T.; Segura-Mendez, N.H.; Scheffler-Mendoza, S.C.; O‘Farrill-Romanillos, P.; Gonzalez-Serrano, M.E.; Rodriguez-Alba, J.C.; et al. Delayed Diagnosis in X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia and Its Relationship to the Occurrence of Mutations in BTK Non-Kinase Domains. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2018, 14, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shillitoe, B.; Bangs, C.; Guzman, D.; Gennery, A.R.; Longhurst, H.J.; Slatter, M.; Edgar, D.M.; Thomas, M.; Worth, A.; Huissoon, A.; et al. The United Kingdom Primary Immune Deficiency (UKPID) Registry 2012 to 2017. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2018, 192, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, A.; Jindal, A.K.; Suri, D.; Vignesh, P.; Gupta, A.; Saikia, B.; Minz, R.W.; Banday, A.Z.; Tyagi, R.; Arora, K.; et al. Clinical and Genetic Profile of X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia: A Multicenter Experience from India. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 612323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moin, M.; Aghamohammadi, A.; Farhoudi, A.; Pourpak, Z.; Rezaei, N.; Movahedi, M.; Gharagozlou, M.; Ghazi, B.M.S.; Zahed, A.; Abolmaali, K.; et al. X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia: A Survey of 33 Iranian Patients. Immunol. Investig. 2004, 33, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekrvand, S.; Yazdani, R.; Olbrich, P.; Azizi, G.; Shirzadi, R.; Modaresi, M.; Sohani, M.; Delavari, S.; Kalantari, A.; Shariat, M.; et al. Evaluation of Respiratory Complications in Patients with X-Linked and Autosomal Recessive Agammaglobulinemia. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 31, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Stirling, R.G.; Paul, E.; Hore-Lacy, F.; Thompson, B.R.; Douglass, J.A. Longitudinal Decline in Lung Function in Patients with Primary Immunoglobulin Deficiencies. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 127, 1414–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelstein, J.A.; Marino, M.C.; Lederman, H.M.; Jones, S.M.; Sullivan, K.; Burks, A.W.; Conley, M.E.; Cunningham-Rundles, C.; Ochs, H.D. X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia: Report on a United States Registry of 201 Patients. Medicine 2006, 85, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryan, B.A.; Battersby, A.; Shillitoe, B.M.J.; Barge, D.; Bourne, H.; Flood, T.; Cant, A.J.; Stroud, C.; Gennery, A.R. Respiratory Health and Related Quality of Life in Patients with Congenital Agammaglobulinemia in the Northern Region of the UK. J. Clin. Immunol. 2016, 36, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, M.; Lee, M.; Oksenhendler, E.; Chapel, H. The Ratio of Mean Daily IgG Increment/Mean Daily Dose in Immunoglobulin Replacement Therapy in Primary Antibody Deficiencies. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2015, 3, 998–1000.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazzami, B.; Yazdani, R.; Azizi, G.; Kiaei, F.; Tafakori, M.; Modaresi, M.; Shirzadi, R.; Mahdaviani, S.A.; Sohani, M.; Abolhassani, H.; et al. Respiratory Complications in Patients with Hyper IgM Syndrome. J. Clin. Immunol. 2019, 39, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünsal, H.; Ekinci, A.; Aliyeva, G.; Bildik, H.N.; Esenboğa, S.; Çağdaş, D. Characteristics of Patients with Low Serum IgE Levels and Selective IgE Deficiency: Data from an Immunodeficiency Referral Center. Clin. Immunol. 2025, 270, 110403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picado, C.; Ortiz de Landazuri, I.; Vlagea, A.; Bobolea, I.; Arismendi, E.; Amaro, R.; Sellarés, J.; Bartra, J.; Sanmarti, R.; Hernandez-Rodriguez, J.; et al. Spectrum of Disease Manifestations in Patients with Selective Immunoglobulin E Deficiency. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.D.; Burgel, P.-R.; Daley, C.L.; De Soyza, A.; Haworth, C.S.; Mauger, D.; Loebinger, M.R.; McShane, P.J.; Ringshausen, F.C.; Blasi, F.; et al. Phase 3 Trial of the DPP-1 Inhibitor Brensocatib in Bronchiectasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 1569–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.D.; Shteinberg, M.; Mall, M.A.; O’Donnell, A.E.; Watz, H.; Gupta, A.; Frahm, E.; Eleftheraki, A.; Rauch, J.; Chotirmall, S.H.; et al. Cathepsin C (Dipeptidyl Peptidase 1) Inhibition in Adults with Bronchiectasis: AIRLEAF, a Phase II Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Dose-Finding Study. Eur. Respir. J. 2025, 65, 2401551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.