Abstract

Background/Objectives: Endotracheal intubation in critically ill patients presents significant challenges due to anatomical and physiological complexities, making airway management crucial. Video laryngoscopy (VL) has emerged as a promising alternative to direct laryngoscopy (DL), offering improved and higher success rates. This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the comparative efficacy and safety of VL versus DL in critically ill adults. Methods: A systematic search was conducted in PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library through August 2024 following PRISMA-2020 guidelines. Randomized controlled trials comparing VL and DL in critically ill adult patients were included. The RoB 2.0 tool assessed bias, and GRADE evaluated the certainty of evidence. The primary outcome was first-attempt success; secondary outcomes included intubation time, glottic visualization, and complications. Random effects models were used for data synthesis. Results: Fifteen studies (4582 intubations) were included. VL improved first-attempt success rates (RR 1.12; 95% CI: 1.04–1.21; I2 = 87%). It also reduced esophageal intubation (RR 0.44; 95% CI: 0.26–0.75), dental injuries (RR 0.32; 95% CI: 0.16–0.67), and poor glottic visualization. No significant differences were found in hypoxemia, hypotension, or mortality. Conclusions: VL enhances intubation success and reduces specific complications, particularly in difficult airways. However, high heterogeneity and low certainty of evidence warrant further studies to clarify its impact on critical patient outcomes.

1. Introduction

Emergency endotracheal intubation in critically ill patients remains a high-stakes procedure, where the choice of intubation technique can significantly impact patient outcomes. Although direct laryngoscopy has been the primary approach since the 1940s with the introduction of Miller and Macintosh laryngoscopes, it presents notable challenges in emergency settings, with success rates varying between experienced practitioners and trainees [1].

The implementation of video laryngoscopy has introduced new perspectives in airway management. Studies have demonstrated that video laryngoscopy provides superior glottic compared to direct laryngoscopy (POGO scores 88.25 ± 22.06 vs. 57.25 ± 29.26, p < 0.001) and potentially faster intubation times (32.90 ± 8.69 vs. 41.33 ± 15.29 s, p = 0.004) in controlled settings [2]. However, the translation of these advantages to emergency scenarios remains complex, with success rates influenced by multiple factors, including operator experience, patient characteristics, and clinical circumstances.

Several anatomical and clinical factors can increase intubation difficulty in emergency settings. These include limited head and neck mobility, high Mallampati scores, restricted mouth opening, and reduced thyromental distance. The impact of these factors varies significantly, with reported difficult airway rates between 6.8% for glottic exposure and 8.2% for mask ventilation in emergency departments [3]. Video laryngoscopy has emerged as a potential solution to these challenges, particularly in predicted difficult airways, where it has demonstrated a higher success rate (80.0% vs. 50.4%, p < 0.001) compared to direct laryngoscopy [4].

The comparative effectiveness of video versus direct laryngoscopy shows notable variation, depending on operator experience and clinical context. Recent data suggest that while video laryngoscopy may improve first-attempt success rates (93.6% vs. 80.8%, p < 0.001; risk difference 0.128, 95% CI: 0.0771–0.181), its utility can be influenced by specific predictors, including head and neck positioning (OR 1.63, 95% CI: 1.14–2.31), mouth opening limitations (OR 1.18, 95% CI: 1.02–1.36), and specific surgical procedures [5].

Despite these advances, significant knowledge gaps persist regarding the optimal application of video laryngoscopy in emergency settings. The interplay between device selection, operator proficiency, and patient characteristics remains incompletely understood, particularly in scenarios involving difficult airways managed by experienced clinicians. Furthermore, while video laryngoscopy has demonstrated benefits in controlled environments, its role in emergency airway management requires further clarification, especially concerning factors that might influence success rates and complications.

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the comparative efficacy of video versus direct laryngoscopy for tracheal intubation in critically ill adults. By synthesizing the available evidence, we seek to provide insights into the optimal selection of laryngoscopy techniques in emergency settings, considering patient characteristics and operator experience levels.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted following PRISMA-2020 guidelines and was prospectively registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024613946). The review protocol outlined the objectives, inclusion criteria, search strategy, and planned analyses to ensure methodological transparency and minimize reporting bias.

2.1. Searches

A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library from inception until 8 August 2024, following PRISMA-2020 guidelines. The search strategy included a combination of MeSH terms and free-text keywords related to ‘Critically Ill Adults’, ‘Tracheal Intubation’, ‘Video Laryngoscopy’, and ‘Direct Laryngoscopy’. Boolean operators (AND/OR) were applied to refine results, and language restrictions were not imposed. The full search strategy for each database is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Additionally, reference lists of relevant systematic reviews and included studies were manually screened for potentially eligible trials. The retrieved studies were screened in duplicate by two independent reviewers using the Rayyan platform, and discrepancies were resolved by a third investigator (JJB).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

All studies that met the following criteria were included in this study: Phase 2 or Phase 3 randomized controlled trials that treated critically ill patients requiring tracheal intubation in an intensive care unit or emergency room setting, where video laryngoscopy was used to secure the airway as the intervention compared to direct laryngoscopy.

Conference abstracts, systematic reviews, narrative reviews, case reports and series, and letters to the editor were excluded.

2.3. Outcomes

Based on the PICO framework, the primary outcomes of this study included first-attempt intubation success (O) in critically ill adult patients (P) undergoing tracheal intubation with video laryngoscopy (I) compared to direct laryngoscopy (C). Secondary outcomes included time to successful intubation, glottic visualization, hypoxaemia, hypotension, tooth injury, esophageal intubation, and mortality.

The primary outcomes were the first-attempt success rate (defined as placement of an endotracheal tube in the trachea with a single insertion of a laryngoscope blade into the mouth and either a single insertion of an endotracheal tube into the mouth or a single insertion of a bougie into the mouth followed by a single insertion of an endotracheal tube into the mouth), time to successful intubation (defined as the interval [in seconds] between the first insertion of a laryngoscope blade into the mouth and the final placement of an endotracheal tube or tracheostomy tube in the trachea), and glottic view grade (Cormack–Lehane grade of glottis: Reflects glottis. Score range: 1 [sound] to 4 [no glottis]). The secondary outcomes were hypoxaemia (pulse arterial saturation of less than 90%), hypotension (arterial systolic pressure of less than 90 mm Hg), tooth injury, esophageal intubation, and mortality.

2.4. Data Extraction

After the electronic searches, the results were compiled in a single library, and duplicates were eliminated. Then, the first screening step was performed, evaluating the titles and abstracts and applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria to each result reviewed through the Rayyan platform.

The studies included after this phase were searched and analyzed in full text, and a new screening process was carried out, justifying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. After this process, the eligible studies were included in the systematic review, and data extraction began. In disagreement, a third review author (JJB) was consulted.

Data extraction was conducted independently by two reviewers, and discrepancies were resolved by a third investigator. In cases where data were missing or incompletely reported in the included studies, we attempted to contact the corresponding authors to obtain additional information. If missing data could not be retrieved, we applied the following strategies. (1) For missing standard deviations in continuous outcomes, we estimated them from interquartile ranges or confidence intervals when available. (2) For dichotomous outcomes with missing event counts, we used sensitivity analyses with different plausible scenarios to assess the impact on pooled estimates. (3) Studies with excessive missing data (>20% of key outcomes) were excluded from quantitative synthesis. These approaches aimed to minimize bias and ensure robustness in the meta-analysis.

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

The risk of bias (RoB) was independently assessed using the RoB 2.0 tool. This tool evaluates five domains: (1) risk of bias arising from the randomization process, (2) deviations from intended interventions, (3) missing outcome data, (4) measurement of the outcome, and (5) selection of the reported result. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third author (JJB). RoB per domain and study was described as low, with some concerns, or high for RCTs.

2.6. Data Synthesis

Random-effects models with the inverse variance method were used for all meta-analyses comparing video laryngoscopy (VL) with direct laryngoscopy (DL). This approach was chosen due to the expected clinical and methodological heterogeneity across studies, particularly variations in patient populations, operator expertise, intubation settings (ICU, emergency department, operating room), and VL devices used. The Paule-Mandel method was employed to estimate the between-study τ2 variance, as it provides a robust approach when heterogeneity is present. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using fixed-effects models to assess the stability of the findings. The effects of video laryngoscopy (VL) compared to direct laryngoscopy on dichotomous outcomes were described with relative risks (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI).

The continuity correction method adjusted for null events in one or two arms of the RCT. When more than five studies were found for meta-analysis, adjustments were made using the Hartung-Knapp method. Statistical heterogeneity of effects among RCTs was described by the I2 statistic, whose values represented low (<30%), moderate (30–60%), and high (>60%) levels of heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the robustness of findings. First, fixed-effects models were applied to assess the influence of small-study effects. Second, a leave-one-out analysis was performed by sequentially excluding each study to determine its impact on the overall effect size. Third, we conducted an additional sensitivity analysis excluding studies classified as having a high risk of bias to examine their influence on the pooled estimates. These approaches aimed to ensure the stability and reliability of our results. The metabin function of the R 3.5.1 meta library (https://www.r-project.org/; accessed on 15 December 2024) was used. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots combined with Egger’s test for small-study effects. The funnel plots were visually inspected for asymmetry, which may indicate potential publication bias, and Egger’s regression test was used to provide a quantitative assessment. Funnel plots for primary outcomes are provided in Supplementary Figures S1 and S2.

2.7. GRADE Assessment

The GRADE methodology assessed the certainty of the evidence and the degree of recommendation regarding all outcomes. GRADE is based on domains such as risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias, which were evaluated. The outcomes determined the certainty of the evidence, which was described in the summary of results (SoF) tables created using the online software GRADEpro GDT (https://www.gradepro.org; accessed on 15 December 2024) (Supplementary Table S2).

This review informed the reference elements for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA-2020, Supplementary Table S3). PROSPERO ID (CRD42024613946).

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Studies

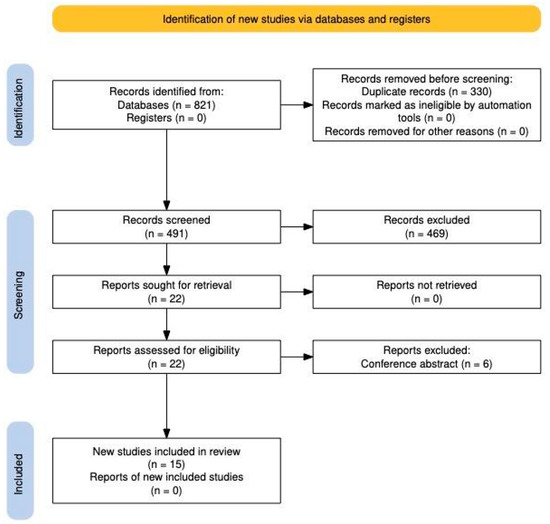

A total of 821 records were identified through database searches, with no records retrieved from registers. After removing 330 duplicates, 491 records were screened based on titles and abstracts, excluding 469 records that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Subsequently, 22 reports were assessed for eligibility through full-text review, and none were excluded due to retrieval issues. However, six reports were excluded as they were conference abstracts without sufficient data for inclusion. Finally, 15 studies met all eligibility criteria and were included in the final review, ensuring a rigorous selection process aligned with PRISMA guidelines [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 Flow chart.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the included studies. The studies were conducted in nations including China and the US and released between 2018 and 2023. Included were randomized, frequently unblinded studies. The studies’ aims varied, focusing on markers like overall procedural results, hemodynamic changes, and ease of intubation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

In most of the studies, no conflicts of interest were declared. More extensive multicenter trials involved up to 1420 patients, whereas more minor investigations involved 163 people. The inclusion criteria primarily focused on critically ill adult patients over 18 undergoing urgent or emergency intubation, frequently in the intensive care unit. Among the many exclusion criteria were patients under the age of 18, pregnant women, and those who were not suitable candidates for endotracheal intubation. The most common reasons for intubation were respiratory failure or airway protection, and the patients’ clinical conditions often included critical circumstances.

Table 2 demonstrates that the studies included a range of video laryngoscopy tools, including the McGrath and GlideScope, with interventions tailored to varying operator experiences and clinical contexts. All control group members used conventional direct laryngoscopy, primarily with the Macintosh blade. Procedure descriptions emphasized key elements such as preoxygenation methods, anesthetic protocols, and operator direction. Physician experience criteria differed across the investigations, ranging from highly experienced operators to general practitioners in intensive care units, highlighting disparities in the intubation domain. The trials examined success rates, operative duration, and hemodynamic stability outcomes.

Table 2.

Characteristics of interventions.

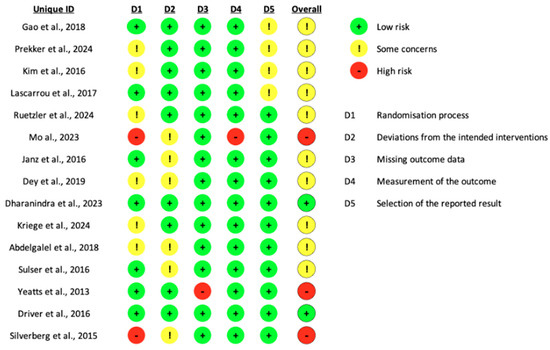

3.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

Among the fifteen studies evaluated, three were at high risk of bias and ten had some concerns. Only two studies had a low risk of bias overall. Two studies were at high risk of bias in the randomization process, one in the deviation from the intended interventions and another study in the missing outcome data (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias assessment [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20].

3.4. Effects of Video Laryngoscopy on Primary and Secondary Outcomes

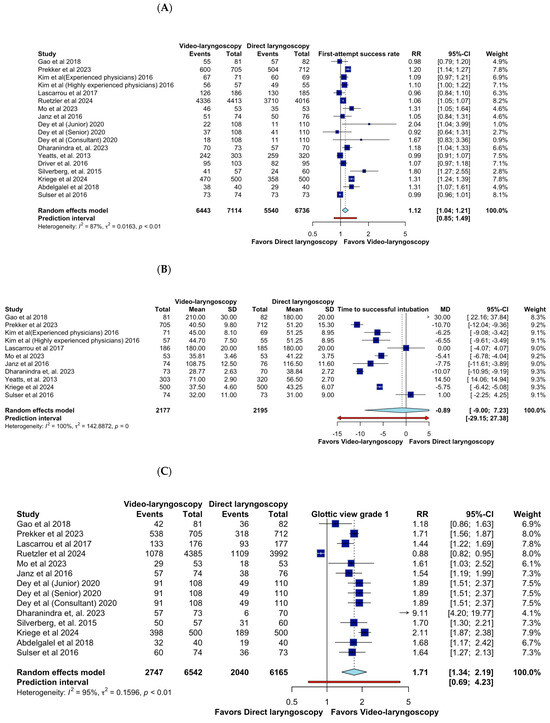

The meta-analysis of the first-attempt success rate of video laryngoscopy (VL) compared to direct laryngoscopy (DL) in critically ill adults undergoing tracheal intubation. The pooled estimate from a random-effects model reveals a relative risk (RR) of 1.12 (95% CI: 1.04–1.21, CoE Very Low), indicating a statisticallsy significant advantage of VL over DL in achieving successful intubation on the first attempt. However, substantial heterogeneity is evident, with an I2 of 87% and a τ2 of 0.0163, suggesting considerable variability across studies. The individual study estimates demonstrate a range of effect sizes, with some studies reporting a more pronounced benefit of VL, such as Silverberg et al. [20] (RR 1.80, 95% CI: 1.27–2.55) and Mo et al. [11] (RR 1.31, 95% CI: 1.05–1.64). The confidence intervals of several studies overlap with the line of no effect (RR = 1.0), emphasizing variability in individual study findings. This heterogeneity may stem from differences in study populations, operator experience, VL devices used, and clinical settings. For instance, Kim et al. [8] stratified their results based on physician experience, demonstrating that highly experienced practitioners achieved better outcomes with VL (RR 1.10, 95% CI: 1.00–1.22), whereas experienced physicians showed a more modest effect (RR 1.09, 95% CI: 0.97–1.21). The prediction interval (0.85–1.49) suggests that future studies could observe a range of outcomes, including those favoring DL, underscoring the uncertainty in generalizing these findings (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Effects of video laryngoscopy on primary outcomes. (A) First-attempt success rate; (B) Time to successful intubation; (C) Glottic view grade 1; (D) Glottic view grade 2a; (E) Glottic view grade 2b; (F) Glottic view grade 3 [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20].

Likewise, the forest plot displays the meta-analysis of time to successful intubation comparing video laryngoscopy (VL) and direct laryngoscopy (DL) in critically ill adults. The pooled mean difference (MD) of −0.89 s (95% CI: −9.00 to 7.23, CoE Very Low) suggests no statistically significant difference between techniques. However, substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 100%) indicates considerable variability among studies. Several studies report a shorter intubation time with VL, such as Prekker et al. [7] (MD −10.70, 95% CI: −12.04 to −9.36) and Dharanindra et al. [14] (MD −10.07, 95% CI: −10.95 to −9.19). Others, such as Yeatts et al. [18] (MD 14.50, 95% CI: 14.06 to 14.94), favor DL, contributing to the observed heterogeneity. The wide prediction interval (−29.15 to 27.38) underscores the uncertainty in future estimates, reinforcing that the impact of VL on intubation time is highly context-dependent. Operator experience, airway difficulty, and device type may influence outcomes, highlighting the need for further standardized research (Figure 3B).

Also, the set of forest plots evaluates the impact of video laryngoscopy (VL) versus direct laryngoscopy (DL) on glottic view quality, classified by Cormack–Lehane grades. For glottic view grade 1, the pooled relative risk (RR) is 1.71 (95% CI: 1.34–2.19; CoE Very Low), indicating that VL significantly improves optimal glottic visualization compared to DL. However, high heterogeneity (I2 = 95%) suggests variability in operator skill, patient characteristics, or device use. In grade 2a, VL demonstrates a protective effect (RR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.41–0.74), favoring DL in achieving this level of glottic exposure. The substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 92%) underscores study differences in defining and achieving airway exposure. For grade 2b, VL significantly reduces the incidence (RR = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.17–0.59), reinforcing its advantage in preventing suboptimal visualization. Heterogeneity remains high (I2 = 92%), suggesting differences in study populations and procedural factors. Similarly, for grade 3, VL demonstrates a strong reduction in poor glottic views (RR = 0.40, 95% CI: 0.20–0.76), with heterogeneity (I2 = 81%) reflecting clinical variations. These findings confirm that VL provides superior glottic visualization, reducing the likelihood of difficult airway scenarios. However, high heterogeneity suggests the need for further research on standardizing VL use across clinical settings (Figure 3C–F).

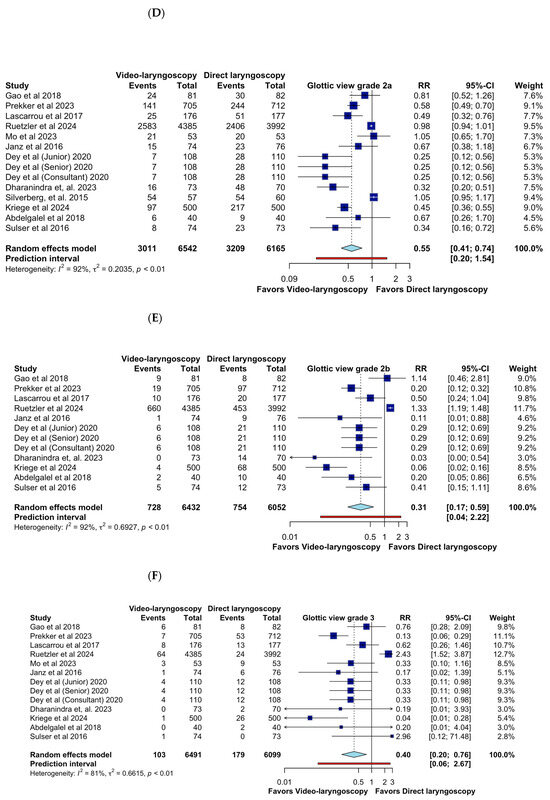

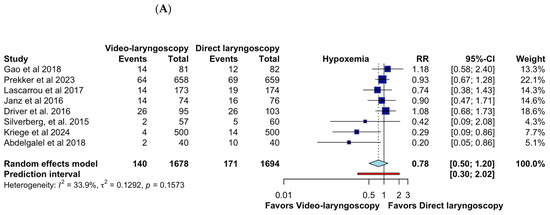

On the other hand, the forest plot evaluates the impact of video laryngoscopy (VL) versus direct laryngoscopy (DL) on the incidence of hypoxemia during tracheal intubation. The pooled relative risk (RR) of 0.78 (95% CI: 0.50–1.20; CoE Very Low) suggests a potential reduction in hypoxemia with VL; however, the confidence interval includes the null value, indicating no statistically significant difference. Heterogeneity is moderate (I2 = 33.9%), suggesting relatively consistent findings across studies. While some individual studies, such as Kriege et al. [15] (RR = 0.29, 95% CI: 0.09–0.86) and Abdelgalel et al. [16] (RR = 0.20, 95% CI: 0.05–0.86), favor VL, others show no significant effect. The prediction interval (0.30–2.02) indicates considerable uncertainty in future study outcomes, reinforcing the need for further research. Overall, while VL may reduce hypoxemia, the current evidence does not confirm a definitive advantage over DL (Figure 4A).

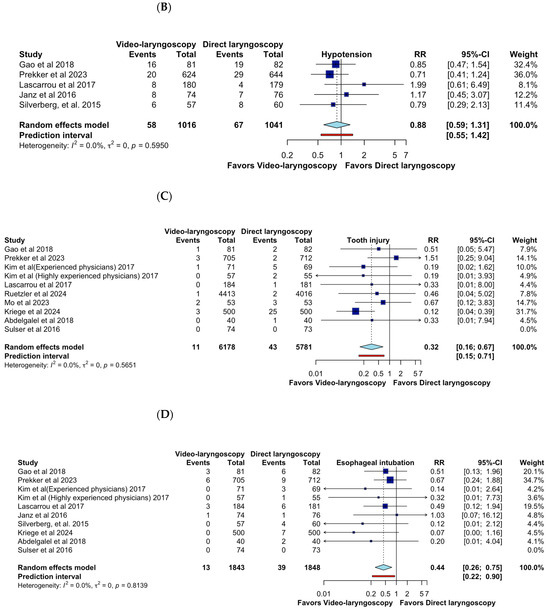

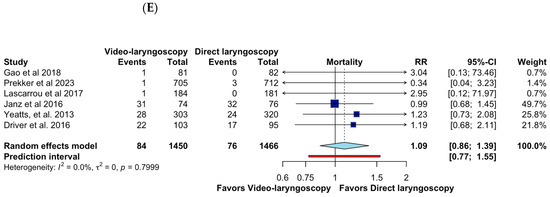

Figure 4.

Effects of video laryngoscopy on secondary outcomes. (A) Hypoxemia; (B) Hypotension; (C) Tooth injury; (D) Esophageal intubation; (E) Mortality [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,16,17,19,20].

The forest plot assesses the impact of video laryngoscopy (VL) versus direct laryngoscopy (DL) on the incidence of hypotension following intubation. The pooled relative risk (RR) of 0.88 (95% CI: 0.59–1.31; CoE Very Low) suggests no statistically significant difference between VL and DL in terms of hypotension risk. Heterogeneity is negligible (I2 = 0%), indicating high consistency across studies. Individual study results vary, with some favoring VL (Prekker et al. [7], RR = 0.71, 95% CI: 0.41–1.24) and others showing no clear advantage. The prediction interval (0.55–1.42) suggests future studies may yield varying outcomes, but overall, VL does not appear to significantly influence hypotension rates compared to DL. Further research is needed to assess hemodynamic stability in different clinical contexts (Figure 4B).

Also, the forest plot evaluates the impact of video laryngoscopy (VL) versus direct laryngoscopy (DL) on the incidence of tooth injury during intubation. The pooled relative risk (RR) of 0.32 (95% CI: 0.16–0.67, CoE Very Low) indicates a statistically significant reduction in tooth injuries with VL. Heterogeneity is absent (I2 = 0%), suggesting highly consistent results across studies. The study by Kriege et al. [15] (RR = 0.12, 95% CI: 0.04–0.39) contributes substantially to the overall effect, reinforcing VL’s advantage in reducing dental trauma. The prediction interval (0.15–0.71) supports the robustness of these findings, suggesting that future studies are likely to confirm this protective effect. These results highlight VL’s benefit in minimizing airway-related trauma, particularly in challenging intubations (Figure 4C).

The forest plot evaluates the impact of video laryngoscopy (VL) versus direct laryngoscopy (DL) on the incidence of esophageal intubation. The pooled relative risk (RR) of 0.44 (95% CI: 0.26–0.75, CoE Very Low) indicates a statistically significant reduction in esophageal intubation with VL compared to DL. Heterogeneity is absent (I2 = 0%), demonstrating high consistency across studies. While some individual studies, such as Kriege et al. [15] (RR = 0.07, 95% CI: 0.00–1.16), show a pronounced benefit of VL, others report more modest effects. The prediction interval (0.22–0.90) reinforces the robustness of these findings, suggesting that future studies will likely confirm this protective effect. These results highlight VL’s advantage in reducing critical airway misplacement, making it a valuable tool in difficult airway management (Figure 4D).

Finally, the forest plot evaluates the impact of video laryngoscopy (VL) versus direct laryngoscopy (DL) on mortality. The pooled relative risk (RR) of 1.09 (95% CI: 0.86–1.39; CoE Very Low) suggests no statistically significant difference between VL and DL in terms of mortality rates. Heterogeneity is absent (I2 = 0%), indicating high consistency across studies. Individual study estimates vary widely, with some suggesting increased mortality risk with VL (Gao et al. [6], RR = 3.04, 95% CI: 0.13–73.46) and others favoring DL (Prekker et al. [7], RR = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.04–3.23), but all confidence intervals include the null effect. The prediction interval (0.77–1.55) reinforces the uncertainty in future outcomes, suggesting that mortality is likely influenced by multiple factors beyond the choice of laryngoscopy technique. Overall, these results indicate that while VL improves intubation success and reduces complications, its impact on patient survival remains inconclusive. Further research in high-risk populations is needed (Figure 4E).

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of our findings. The application of fixed-effects models produced estimates consistent with those obtained using random-effects models, indicating that small-study effects did not substantially alter the results. The leave-one-out analysis, in which individual studies were sequentially removed, demonstrated that no single study disproportionately influenced the overall effect size. Furthermore, excluding studies classified as having a high risk of bias did not materially change the pooled estimates, suggesting that the observed effects were not driven by methodological weaknesses in certain studies. These findings reinforce the reliability of our conclusions regarding the comparative efficacy and safety of video laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy in critically ill adults.

The certainty of evidence was assessed using GRADE. The first-attempt success rate showed a low certainty of evidence, primarily due to heterogeneity (I2 = 87%). The reduction in esophageal intubation with video laryngoscopy had a moderate certainty of evidence, while the mortality outcome was rated as very low certainty, indicating high uncertainty in its effect estimate (Table 3)

Table 3.

GRADE certainty of evidence for outcomes.

4. Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the efficacy and safety of video laryngoscopy (VL) compared to direct laryngoscopy (DL) for tracheal intubation in critically ill adults. While the findings highlight certain advantages of VL, such as improved first-attempt success rates and reduced complications, the overall certainty of evidence remains low, limiting these results’ generalizability and clinical applicability.

The analysis demonstrated that VL improved the first-attempt success rate compared to DL, with a relative risk (RR) of 1.12 (95% CI: 1.04–1.21). Despite the statistical significance, the very low certainty of the evidence, influenced by high heterogeneity (I2 = 87%) and potential bias in the included studies, limits confidence in these findings. Time to successful intubation showed no significant difference between techniques (MD −0.89 s; 95% CI: −9.0 to 7.23), with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 100%) that further reduces confidence in this outcome. These findings suggest that the clinical advantage of VL may depend on the context, including the operator’s experience and the clinical scenario.

These results align with previous findings that reported similar success rates in emergency settings [1], although our pooled analysis provides a more comprehensive assessment across multiple clinical contexts. The high heterogeneity observed likely reflects variations in operator experience, patient characteristics, and specific device configurations across studies. The authors observed that 80.8% of patients were successfully intubated on the first pass. However, in the GS group, 293 of the 313 (93.6%) were successful on the first pass (p < 0.001; risk difference of 0.128 with 95% CI of 0.0771–0.181). Similarly, a study showed that first-attempt success rates were 71.4% in the McGrath X-blade group versus 79.0% in the CMAC video laryngoscope group (p = 0.26), with an absolute difference of −7.6% (95% CI: −20%, 5.0%, p-value = 0.26) [21]. The authors concluded that in patients with in-line manual stabilization, without anticipated airway difficulty and in the hands of experienced operators, the McGrath X-blade provided superior glottic views but conferred no advantage over the C-MAC, with a longer median time to intubation compared to the CMAC video laryngoscope.

A key finding was the improved laryngeal associated with VL, as assessed by Cormack–Lehane grades. VL showed better performance for grades one and 2a, but the increased uncertainty in evidence counterbalanced this benefit. For grades 2b and 3, VL significantly reduced poor s compared to DL, suggesting a potential advantage in scenarios of difficult airway intubation. However, these results should be interpreted cautiously due to inconsistencies across studies. Consistent with our findings, previous studies concluded that Cormack–Lehane grades and glottic opening percentage scores were similar, and no significant differences were found between the two groups [6]. There was no statistical difference between the VL and DL groups regarding intubation complications (p = 0.310).

VL was associated with reduced complications, such as tooth injuries (RR 0.32; 95% CI: 0.16–0.67) and esophageal intubations (RR 0.44; 95% CI: 0.26–0.75), with low certainty of evidence. Other studies found no significant differences between complications such as dental injury or esophageal intubation. However, a study indicates that fewer esophageal intubations were observed in the video laryngoscopy cohort (0.4% vs. 1.3%, AOR = 0.2, 95% CI = 0.1 to 0.5) [22]. These findings are clinically relevant, as they highlight the potential safety benefits of VL. Conversely, outcomes such as hypoxaemia, hypotension, and mortality did not show significant differences between VL and DL, with very low certainty of evidence, underscoring the need for further research in these areas.

Currently, the lack of standardized definitions and inconsistent reporting of adverse events pose a challenge in accurately assessing the safety of video laryngoscopy (VL) across different patient populations and clinical settings. Previous studies have used varying criteria to define complications such as esophageal intubation, dental trauma, and hypoxemia, making direct comparisons difficult. To address this limitation, future research should adopt uniform definitions and consistent reporting protocols. The implementation of standardized guidelines will enable a more precise evaluation of VL-associated risks and facilitate cross-study comparisons, ultimately improving the clinical applicability of findings.

The effectiveness of VL is significantly influenced by operator skill and experience. While VL is designed to enhance glottic visualization and facilitate intubation, its success depends largely on clinician familiarity with the device and technical proficiency. Studies have shown that the learning curve for VL varies, and insufficient training may mitigate its potential benefits. Therefore, it is essential that training programs include specific VL modules and that periodic competency assessments are conducted to ensure effective implementation in clinical practice.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into airway management represents a promising direction for future research. Recently, La via et al. (2024) [23] explored the use of AI models, including ChatGPT 4.0, in airway management, highlighting applications in education, clinical decision support, and patient communication. Furthermore, AI has the potential to improve difficult airway prediction by analyzing facial images and other clinical data, surpassing the limitations of traditional physical examinations. For instance, deep learning models have been developed to classify intubation difficulty based on facial image analysis, achieving 80.5% accuracy and 83.3% specificity. These tools could provide real-time assistance during intubation procedures, enhancing both safety and efficiency. However, clinical implementation requires rigorous validation and consideration of ethical and practical challenges, such as data privacy and the need for advanced technological infrastructure [23].

Our findings suggest that video laryngoscopy (VL) should be prioritized over direct laryngoscopy (DL) in scenarios involving difficult airways, given its higher first-attempt success and lower rates of esophageal intubation and dental trauma. This is particularly relevant in intensive care units (ICU) and emergency departments (ED), where rapid and successful airway management is critical. However, the benefit of VL may be operator-dependent, highlighting the need for standardized training programs to ensure proficiency. Additionally, while VL improves technical success, its lack of impact on mortality suggests that other factors, such as ventilation strategies and hemodynamic optimization, remain crucial for patient outcomes.

Several factors limit the robustness of our findings. First, most studies included in this meta-analysis were classified as having a high risk of bias or some concerns in critical domains, including randomization and outcome reporting. Second, the heterogeneity across studies was substantial, reflecting differences in study design, operator expertise, and patient populations. Finally, the very low certainty of evidence for many outcomes, as assessed using GRADE, reduces the confidence in the clinical applicability of these results.

These findings support the preferential use of video laryngoscopy in anticipated difficult airway scenarios and critically ill patients where maximizing first-pass success is essential. However, operator training and experience remain key determinants of success, emphasizing the need for structured airway management education. Future research should focus on optimizing training protocols and identifying specific clinical settings where VL provides the greatest advantage

Despite these limitations, the findings suggest that video laryngoscopy (VL) may offer advantages over direct laryngoscopy (DL), particularly in scenarios of predicted difficult airways. Its ability to enhance laryngeal and reduce complications, such as esophageal intubation and dental injury, is promising. However, the absence of significant improvements in critical outcomes, including mortality, underscores the need for cautious interpretation. These findings highlight that the incremental benefits of VL over DL may be context-dependent, particularly in emergencies managed by experienced providers.

Future research should address the methodological limitations identified in this meta-analysis to enhance the reliability and clinical applicability of the findings. High-quality, large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with standardized protocols are essential to reduce the substantial heterogeneity observed in primary outcomes and improve the overall certainty of the evidence. Such trials should prioritize rigorous methodologies, as most included studies demonstrated a high risk of bias or concerns in critical domains, particularly in randomization processes and outcome reporting.

Additionally, future studies should establish standardized definitions and consistent reporting of adverse events to evaluate better safety outcomes across diverse patient populations and clinical settings. Moreover, the role of operator expertise and experience in influencing the relative effectiveness of video laryngoscopy should be further explored.

5. Conclusions

Video laryngoscopy (VL) improves first-attempt success rates and reduces complications such as esophageal intubation and dental injury compared to direct laryngoscopy (DL), particularly in difficult airways. However, its universal adoption remains uncertain due to significant heterogeneity among studies and the low certainty of evidence for critical outcomes such as mortality. The decision to use VL should be individualized, considering patient-specific factors, operator expertise, and available resources. Future research should focus on standardizing training programs, evaluating device-specific performance, and assessing patient-centered outcomes to clarify its clinical impact.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm14061933/s1: Table S1. Strategy search; Table S2. GRADE assessment; Table S3. PRISMA checklist. Figure S1. Funnel plot for First-attempt success rate; Figure S2. Funnel plot for Time to successful intubation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.P.P., R.R.-R., R.A.-S., J.Y.-V., O.R.-L. and J.J.B.; software, J.J.B.; validation, P.P.P., R.R.-R., R.A.-S., J.Y.-V., O.R.-L. and J.J.B.; formal analysis, P.P.P., R.R.-R., R.A.-S., J.Y.-V., O.R.-L. and J.J.B.; investigation, P.P.P., R.R.-R., R.A.-S., J.Y.-V., O.R.-L. and J.J.B., P.P.P., R.R.-R., R.A.-S., J.Y.-V., O.R.-L. and J.J.B.; resources, J.J.B.; data curation, J.J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, P.P.P., R.R.-R., R.A.-S., J.Y.-V., O.R.-L. and J.J.B.; writing—review and editing, P.P.P., R.R.-R., R.A.-S., J.Y.-V., O.R.-L. and J.J.B.; visualization, P.P.P., R.R.-R., R.A.-S., J.Y.-V., O.R.-L. and J.J.B.; supervision, J.J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Universidad Señor de Sipan–Vicerrectorado de investigacion.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ibinson, J.W.; Ezaru, C.S.; Cormican, D.S.; Mangione, M.P. GlideScope Use improves intubation success rates: An observational study using propensity score matching. BMC Anesthesiol. 2014, 14, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqil, M.; Khan, M.U.; Mansoor, S.; Mansoor, S.; Khokhar, R.S.; Narejo, A.S. Incidence and severity of postoperative sore throat: A randomised comparison of Glidescope with Macintosh laryngoscope. BMC Anesthesiol. 2017, 17, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Walline, J.H.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Xu, J.; Yu, X. Incidence and diagnostic validity of difficult airway in emergency departments in China: A cross-sectional survey. J. Thorac. Dis. 2023, 15, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J.; Kang, H.-G.; Lim, T.H.; Chung, H.S.; Cho, J.; Oh, Y.-M.; Kim, Y.-M.; on behalf of the Korean Emergency Airway Management Registry (KEAMR) Investigators. Endotracheal intubation using a GlideScope video laryngoscope by emergency physicians: A multicentre analysis of 345 attempts in adult patients. Emerg. Med. J. EMJ 2010, 27, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.F.; Abrons, R.O.; Cattano, D.; Bayman, E.O.; Swanson, D.E.; Hagberg, C.A.; Todd, M.M.; Brambrink, A.M. First-Attempt Intubation Success of Video Laryngoscopy in Patients with Anticipated Difficult Direct Laryngoscopy: A Multicenter Randomised Controlled Trial Comparing the C-MAC D-Blade Versus the GlideScope in a Mixed Provider and Diverse Patient Population. Anesth. Analg. 2016, 122, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.-X.; Song, Y.-B.; Gu, Z.-J.; Zhang, J.-S.; Chen, X.-F.; Sun, H.; Lu, Z. Video versus direct laryngoscopy on successful first-pass endotracheal intubation in ICU patients. World J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 9, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prekker, M.E.; Driver, B.E.; Trent, S.A.; Resnick-Ault, D.; Seitz, K.P.; Russell, D.W.; Gaillard, J.P.; Latimer, A.J.; Ghamande, S.A.; Gibbs, K.W.; et al. Video versus Direct Laryngoscopy for Tracheal Intubation of Critically Ill Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Park, S.O.; Lee, K.R.; Hong, D.Y.; Baek, K.J.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, P.C. Video laryngoscopy vs. direct laryngoscopy: Which should be chosen for endotracheal intubation during cardiopulmonary resuscitation? A prospective randomised controlled study of experienced intubators. Resuscitation 2016, 105, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascarrou, J.B.; Boisrame-Helms, J.; Bailly, A.; Le Thuaut, A.; Kamel, T.; Mercier, E.; Ricard, J.-D.; Lemiale, V.; Colin, G.; Mira, J.P.; et al. Video Laryngoscopy vs Direct Laryngoscopy on Successful First-Pass Orotracheal Intubation Among ICU Patients: A Randomised Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017, 317, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruetzler, K.; Bustamante, S.; Schmidt, M.T.; Almonacid-Cardenas, F.; Duncan, A.; Bauer, A.; Turan, A.; Skubas, N.J.; Sessler, D.I.; Collaborative VLS Trial Group; et al. Video Laryngoscopy vs Direct Laryngoscopy for Endotracheal Intubation in the Operating Room: A Cluster Randomised Clinical Trial. JAMA 2024, 331, 1279–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, C.; Zhang, L.; Song, Y.; Liu, W. Safety and effectiveness of endotracheal intubation in critically ill emergency patients with videolaryngoscopy. Medicine 2023, 102, e35692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janz, D.R.; Semler, M.W.; Lentz, R.J.; Matthews, D.T.; Assad, T.R.; Norman, B.C.; Keriwala, R.D.; Ferrell, B.A.; Noto, M.J.; Shaver, C.M.; et al. Randomised Trial of Video Laryngoscopy for Endotracheal Intubation of Critically Ill Adults. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 44, 1980–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Pradhan, D.; Saikia, P.; Bhattacharyya, P.; Khandelwal, H.; Adarsha, K.N. Intubation in the Intensive Care Unit: C-MAC video laryngoscope versus Macintosh laryngoscope. Med. Intensiva. 2020, 44, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharanindra, M.; Shah, J.; Iyer, S.; Kulkarni, S.S.; Jedge, P.P.; Patil, V.C.; Dhanasekaran, K.S. Endotracheal Intubation with King Vision Video Laryngoscope vs Macintosh Direct Laryngoscope in ICU: A Comparative Evaluation of Performance and Outcomes. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 27, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kriege, M.; Lang, P.; Lang, C.; Schmidtmann, I.; Kunitz, O.; Roth, M.; Strate, M.; Schmutz, A.; Vits, E.; Balogh, O.; et al. A comparison of the McGrath videolaryngoscope with direct laryngoscopy for rapid sequence intubation in the operating theatre: A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Anaesthesia 2024, 79, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelgalel, E.F.; Mowafy, S.M.S. Comparison between Glidescope, Airtraq and Macintosh laryngoscopy for emergency endotracheal intubation in intensive care unit: Randomised controlled trial. Egypt. J. Anaesth. 2018, 34, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulser, S.; Ubmann, D.; Schlaepfer, M.; Brueesch, M.; Goliasch, G.; Seifert, B.; Spahn, D.R.; Ruetzler, K. C-MAC videolaryngoscope compared with direct laryngoscopy for rapid sequence intubation in an emergency department: A randomised clinical trial. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2016, 33, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeatts, D.J.; Dutton, R.P.; Hu, P.F.; Chang, Y.-W.W.; Brown, C.H.; Chen, H.; Grissom, T.E.; Kufera, J.A.; Scalea, T.M. Effect of video laryngoscopy on trauma patient survival: A randomised controlled trial. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013, 75, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, B.E.; Prekker, M.E.; Moore, J.C.; Schick, A.L.; Reardon, R.F.; Miner, J.R. Direct Versus Video Laryngoscopy Using the C-MAC for Tracheal Intubation in the Emergency Department, a Randomised Controlled Trial. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2016, 23, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, M.J.; Li, N.; Acquah, S.O.; Kory, P.D. Comparison of video laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy during urgent endotracheal intubation: A randomised controlled trial. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 43, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tan, L.Z.; Toh, H.; Foo, C.W.; Wijeratne, S.; Hu, H.; Seet, E. Comparing the first-attempt tracheal intubation success of the hyperangulated McGrath® X-blade vs the Macintosh-type CMAC videolaryngoscope in patients with cervical immobilization: A two-centre randomised controlled trial. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2022, 36, 1139–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.A.; Kaji, A.H.; Fantegrossi, A.; Carlson, J.N.; April, M.D.; Kilgo, R.W.; Walls, R.M.; The National Emergency Airway Registry (NEAR) Investigators. Video Laryngoscopy Compared to Augmented Direct Laryngoscopy in Adult Emergency Department Tracheal Intubations: A National Emergency Airway Registry (NEAR) Study. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2020, 27, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Via, L.; Maniaci, A.; Gage, D.; Cuttone, G.; Misseri, G.; Lentini, M.; Paternò, D.S.; Pappalardo, F.; Sorbello, M. Exploring the potential of artificial intelligence in airway management. Trends Anaesth. Crit. Care 2024, 59, 101512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).