Abstract

Objective: The objective of this study was to investigate which of two short questionnaires, the Asthma Control Test (ACT) or the COPD Assessment Test (CAT), correlates better with severity variables and whether they share similar determinants in patients with asthma–COPD overlap. Method: This observational, cross-sectional, multicentric study included smokers and former smokers of more than 10 pack-years, with non-fully reversible airflow obstruction and either a concomitant diagnosis of asthma or signs of type 2 inflammation, from 15 centres in Spain. Results: A total of 157 patients were included, 109 (69.4%) were men, the mean age was 63.3 (SD: 9) years and the mean FEV1 (%) was 59.7% (SD: 20.5%). The mean CAT score was 14.5 (SD: 8.7), and the mean ACT score was 17.9 (SD: 5.2). Both scores showed good correlations (r = 0.717; p < 0.001). In the multivariate analysis, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and mMRC dyspnoea scores were independently and significantly associated with both the CAT and ACT scores; however, age was only significantly associated with the CAT, and the EQ-5D scores and the number of exacerbations in the previous year were only significantly associated with the ACT scores. The ACT had a slightly better predictive value for exacerbations than the CAT (AUC = 0.70 (95% CI: 0.62 to 0.79 vs. 0.65 (95% CI: 0.56 to 0.74))). Conclusions: There is a good correlation between ACT and CAT scores in patients with ACO. However, severe patients scored worse on the CAT than the ACT. Anxiety, depression and dyspnoea were significantly associated with both the CAT and ACT scores. The ACT was a slightly better predictor of exacerbations than the CAT in this population.

1. Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma are two very prevalent diseases in the adult population. In Spain, the estimated prevalence of COPD is around 11.8% of the total population over 40 years of age [1], while the prevalence of asthma in adulthood is estimated to be 5.1% [2]. Both diseases are characterised by being chronic inflammatory diseases that affect the airway, with airflow obstruction that is usually more variable in asthma and not fully reversible in COPD. Due to the high prevalence of both diseases, they may coexist in asthmatics who smoke and develop emphysema and chronic bronchitis or smokers with COPD who have a predominant T2 type of inflammation [3,4,5]. This T2 inflammation in COPD is characterised by peripheral blood and tissue eosinophilia, high fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) levels, high bronchial hyperresponsiveness and better responses to treatment with oral and inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) [5,6,7,8]. These two types of COPD patients, those with coexisting asthma and those with predominant T2 COPD, were grouped together and defined as asthma–COPD overlap (ACO) by the Spanish COPD treatment guidelines because of their similar responses to ICSs [9]. More recently, other guidelines have adopted similar definitions of ACO [10,11,12]. Among the population of patients with COPD, approximately 25% to 30% fulfil the definition of ACO [13,14,15], and these individuals usually have more exacerbations and hospitalisations and a worse quality of life compared with persons with asthma or COPD alone [7,13,16,17,18,19]. However, no patient-reported outcomes have been developed or their performances specifically compared in this population.

The questionnaire most widely used for COPD in clinical practice is the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) [20], which has been adopted by the GOLD [21] and other guidelines [22] for managing initial pharmacological treatment in COPD. On the other hand, the Asthma Control Test (ACT) [23] is extensively used to determine the degree of clinical control of asthma. It is not clear if these two short questionnaires are similarly valid in patients with ACO or whether they measure different dimensions of the disease and have different determinants in this population.

The objectives of our study were: (1) to determine if there is a correlation between the scores of the ACT and CAT questionnaires in patients with ACO; (2) to identify the determinants of CAT and ACT scores; (3) to analyse the correlations between ACT and CAT scores and severity variables (i.e., exacerbations, lung function, exercise capacity and dyspnoea) in patients with ACO and (4) to establish the most appropriate ACT or CAT cut-off point to predict exacerbations in these patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of This Study

This was an observational, cross-sectional, multicentric study performed in the pulmonology outpatient clinics of 15 centres in Spain from January 2019 to January 2020. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Albacete (Spain), number 11/2017, as the coordinating centre and by all the other participating centres. All the patients provided signed informed consent to participate in this study.

2.2. Participants

Patients fulfilling the diagnostic criteria of ACO according to the Spanish GesEPOC-GEMA consensus were consecutively included in this study [9]. The patients fulfilling the COPD criteria were over 40 years of age, smokers or ex-smokers with cumulative consumptions of at least 10 pack-years, with post-bronchodilator spirometry showing a forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) < 0.7 and either (a) a diagnosis of asthma or (b) a very positive bronchodilator test (>15% and a 400 mL increase in FEV1) and/or peripheral blood eosinophilia > 300 cells/µL in the previous year [9]. Furthermore, the patients had to be clinically stable for at least four weeks since the resolution of the last exacerbation and not present other chronic respiratory diseases such as lung cancer, the sequelae of pulmonary tuberculosis, the presence of clinically significant bronchiectasis or interstitial lung disease. The presence of severe comorbidities that could have interfered with the objectives of this study, i.e., severe cardiac, renal or liver insufficiency or severe cognitive impairment, was an exclusion criterion.

2.3. Measurements

The anthropometric and sociodemographic data of the patients were collected, as well as the number of exacerbations in the previous year, including the numbers of emergency room visits, hospital admissions and exacerbations that required corticosteroid and/or antibiotic treatment. The degree of dyspnoea was evaluated with the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale [24]. Comorbidities were evaluated with the Charlson Index [25] and the COTE Index [26]. The disease severity was also calculated with the BODEx index [27]. To assess the levels of patient anxiety and depression, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) questionnaire was administered [28], and to measure quality of life, the European Quality of Life—5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire was used [29,30]. The patients performed forced spirometry with a bronchodilator test and a six-minute walking test; according to international standards, only one measurement was requested [31]. Analytical data (C-reactive protein (CRP) values and fibrinogen and eosinophil count) were collected.

The CAT and ACT scores were obtained for each patient. The CAT is a validated, short, self-administered questionnaire that measures the impact of the disease in patients with 8 questions. The score ranges from 0 to 40, with 40 being the worst possible health state and 0 the best [20]. The CAT has an excellent correlation with other quality of life questionnaires [32,33] and allows assessment of the impact of COPD on health status within only a few minutes. On the other hand, the ACT is a self-administered questionnaire that provides a numerical score to assess the control of asthma. It comprises five questions regarding aspects of asthma control relevant to patients. Each question is answered on a 5-point scale, with a total score ranging from 5 to 25; higher scores indicate improved asthma control [23].

A threshold of ≤ 10 has been established as an indicator of low impact of the disease in the case of the CAT [20], and a score > 19 indicates controlled disease in the case of the ACT [23]. Patients presenting with ACT < 20 and CAT > 10 or ACT > 20 and CAT < 10 were classified as “concordant” and those with ACT > 20 and CAT > 10 or ACT > 20 and CAT > 10 as “discordant”.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The results are expressed as absolute numbers and their corresponding percentages for qualitative variables, as means and standard deviation (SD) for quantitative variables with normal distribution and as medians and 25th to 75th percentiles for quantitative variables with non-normal distribution.

The CAT and ACT scores were compared based on the characteristics of the patients using the Student t-test or ANOVA tests with the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons in the case of qualitative variables. The Spearman correlation test was performed to determine if there were correlations between the CAT and ACT scores and other variables of interest, such as exacerbations, the BODE and BODEx indexes, FEV1, dyspnoea according to the mMRC scale and metres walked in the 6-min walk test.

Subsequently, to respond to the rest of the objectives, the scores of both questionnaires were established as dependent variables, and two different multivariate linear regression models were built, including sociodemographic and clinical variables as independent factors. Finally, the receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves of the CAT and ACT scores and exacerbations were calculated and compared using DeLong’s test. The results were defined as statistically significant, with p < 0.05. All the analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical package, version 27.0 (IBM Analytics, Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

A total of 157 patients were included, of whom 109 (69.4%) were men, with a mean age of 63.3 (SD: 9) years, and 47 (29.9%) were active smokers. The diagnostic criteria of the ACO of the studied population are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria of the ACO of the included population.

The mean FEV1 was 59.7% (SD: 20.5%), and the mean BODEx index was 2.1 (SD: 1.8). The mean EQ-5D index was 0.8 (SD: 0.2), and the visual analogue scale (VAS) score was 61.9 (SD: 20.4). The total HADS score was 10.4 (SD: 8.5). The mean eosinophil count was 317 cells/μL (SD: 270), and the mean fibrinogen level was 392.3 mg/dL (SD: 573). Table 2 shows the rest of the descriptive characteristics of the total sample.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the population of patients with ACO included in this study.

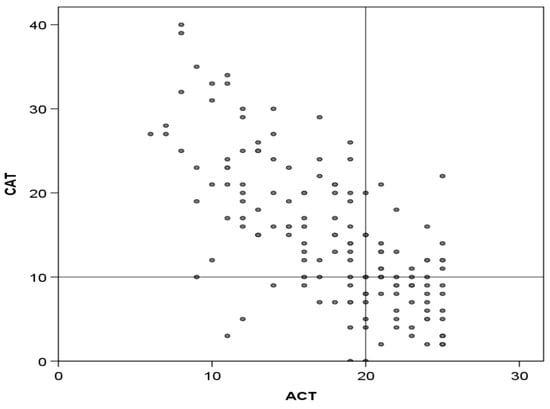

3.2. CAT and ACT Scores and Their Correlation

The mean CAT score was 14.5 (SD: 8.7), while the mean ACT score was 17.9 (SD: 5.2). A total of 38 (24.2%) patients had CAT scores of <10, indicating a low impact, and 48 (30.5%) had ACT scores of >19, indicating good control. The scores of both questionnaires showed good correlation, with a Spearman r-value of 0.717 (p < 0.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Correlation between CAT and ACT scores. Lines divide the area into those with good or poor CAT and ACT scores according to established cut-offs (<10 and >20, respectively). Correlation: Spearman, r = 0.717; p < 0.001.

3.3. Correlations Between CAT and ACT Scores and Markers of Disease Severity

The variables that best correlated with the two questionnaires were the total HADS and HADS depression and anxiety scores, the mMRC dyspnoea scale scores, the EQ-5D index and VAS utility scores and the BODEx index scores. Their correlations with other variables, such as the number of exacerbations and lung function, were also significant, albeit poor (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlations between the CAT and ACT scores and other variables of interest.

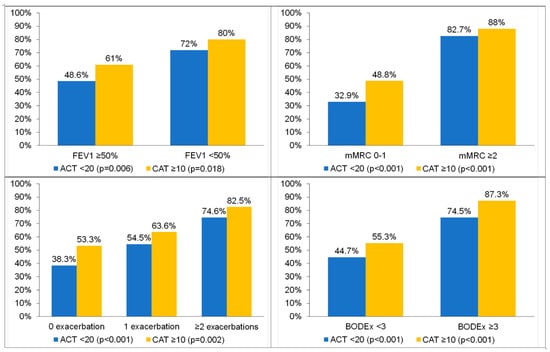

In general, among patients with greater disease severity, significantly more patients were classified as high-impact by the CAT than not controlled by the ACT. For example, among the patients with severe airflow obstruction (FEV1 predicted < 50%), 80% were classified as high-impact by the CAT and 72% were not controlled according to the ACT (p = 0.006). Similar results were obtained for the mMRC scale, the number of exacerbations in the previous year and the BODEx index (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentages of patients with poor control (ACT < 20) or high impact of symptoms (CAT ≥ 10) according to different markers of severity of chronic respiratory disease. p = 0.006 and p = 0.018 for comparison between FEV1 < 50% and FEV ≥ 50% in the ACT and CAT, respectively. p < 0.001 and p < 0.001 for comparison between mMRC 0–1 and mMRC ≥ 2 in the ACT and CAT, respectively. p < 0.001 and p = 0.002 for comparison between 0 exacerbations, 1 exacerbation and ≥ 2 exacerbations in the ACT and CAT, respectively. p < 0.001 and p < 0.001 for comparison between BODEx < 3 and BODEx ≥ 3 in the ACT and CAT, respectively.

3.4. Factors Significantly Associated with CAT and ACT Scores: Univariate and Multivariate Analyses

The variables significantly associated with the CAT and ACT scores differed somewhat. In the multivariate analysis, the HADS and the mMRC dyspnoea scores were independently and significantly associated with both the CAT and ACT scores; however, only age was significantly associated with the CAT and EQ-5D scores, while only the number of exacerbations within the previous year were significantly associated with ACT scores (Table 4).

Table 4.

Simple and multiple linear regression analyses to predict ACT and CAT scores.

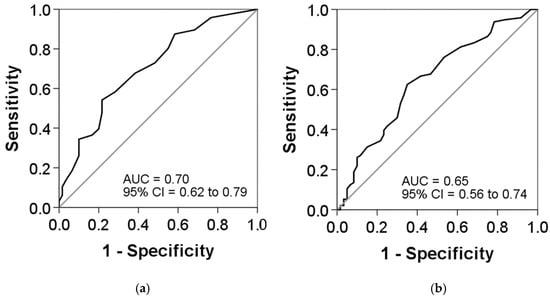

3.5. Predictive Values of the CAT and ACT Scores for Exacerbations

The ROC curves were used to investigate the predictive values of the CAT and ACT scores for exacerbations. The analyses showed a slightly better predictive value for the ACT, with an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.70 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.62 to 0.79; p < 0.001), compared to the CAT questionnaire, with an AUC of 0.65 (95% CI: 0.56 to 0.74; p < 0.001), but a statistically significant difference was not achieved. The best cut-offs for the ACT and CAT questionnaires were 17.5 and 12.5, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the (a) ACT and (b) CAT scores as predictors of exacerbations: (a) area under the curve (AUC), 0.70; cut-off, 17.5; sensitivity, 54.2%; and specificity, 78.3% and (b) AUC, 0.65; cut-off, 12.5; sensitivity, 62.5%; and specificity, 65%. DeLong’s test indicated no significant difference between both AUCs (p = 0.351).

3.6. Discordance Between the CAT and ACT Scores

The majority of patients were concordant in terms of either good control and low impact of symptoms (n = 40, 25.4%) or poor control and high impact (n = 78, 49.7%). However, the results were discordant in 39 (24.8%) subjects. In general, the concordant patients with good control and low levels of symptoms had better lung function, fewer exacerbations and better generic quality of life and anxiety and depression scores compared with the concordant patients with poor control and high symptom levels (Table 2).

We also evaluated whether the characteristics of the discordant patients with poor CAT and good ACT scores differed from the remaining discordant patients with good CAT and poor ACT scores. The results of this comparison showed that the patients with worse CAT but better ACT scores (n = 28, 71.8% of discordant) had significantly higher body mass indexes (BMIs), lower COTE comorbidity indexes and better FEV1/FVC ratios and also showed a trend towards younger age and better FEV1 scores (mL) compared with those with good CAT but poor ACT scores (Table 5).

Table 5.

Characteristics of discordant patients: patients with good CAT but poor ACT scores (CAT < 10 and ACT < 20) and patients with poor CAT and good ACT scores (CAT > 10 and ACT ≥ 20).

4. Discussion

The results of the present study show good correlation between ACT and CAT scores in patients with ACO. However, almost 25% of patients were discordant, the majority of whom (78%) had good ACT but poor CAT scores. These patients had higher BMIs, fewer comorbidities and better FEV1/FVC ratios. Anxiety, depression and dyspnoea were significantly associated with both the CAT and ACT scores, but the CAT was also associated with age and the ACT with previous exacerbations and EQ-5D scores. Finally, the ACT was a slightly better predictor of exacerbations than the CAT in patients with ACO.

There is a need to develop patient-reported outcomes that can help clinicians to understand the impact of respiratory disease and even provide some guidance for treatment management. The ACT has shown to be useful in the assessment of asthma, both in exacerbations and in the stable state, as well as having a good relationship with the quality of life of patients with this disease [34]. In COPD, the CAT is a short questionnaire that correlates very well with Saint George’s Respiratory Questionnaire [33], which is considered the gold-standard questionnaire for specific health-related quality of life, and has been proposed by the GOLD strategy document, as well as by the Spanish COPD guidelines, as a criterion for initial pharmacological therapy for patients with COPD [22,35].

Although asthma and COPD have particular and differential characteristics, there is a group of patients that share characteristics of both diseases. The terminology to identify these subjects has long been debated, but irrespective of the name, there is general agreement that asthma and COPD may coexist, as stated in the last update of the GOLD document [21]. The current study was initiated just before the COVID-19 pandemic, and since it was conducted in Spain, we used the terminology of the Spanish consensus of 2017, which identified patients with criteria of both asthma and COPD or those with COPD and evidence of T2 inflammation as ACO [9]. The name and the criteria to define these patients can be challenged, but we believe that the validity of our results remains. The recommendation of GINA to call these patients “asthma + COPD” [35] is important because using only the term “COPD” or even ACO can hamper the prescription of highly effective drugs that are only approved for asthma [36]. However, for simplicity, in this article, the term ACO has been used, as this was used in the approved protocol.

In general, it was found that both questionnaires can be used for ACO patients, with similar reliabilities. There was a good correlation between the two questionnaires, and both had similar associations with the outcomes of interest, such as exacerbations, although the ACT performed somewhat better. Interestingly, despite the good correlation between the two questionnaires, almost one out of four patients were discordant, with the great majority (three quarters) showing good control in the ACT but high impact in the CAT. These individuals were younger and had more preserved lung function and fewer comorbidities compared to the remaining quarter, who had poor control in the ACT and low impact in the CAT.

These differences may, in part, be related to the different determinants of the scores of both tools. In the multivariate analysis, generic health-related quality of life and previous exacerbations were significantly and independently associated with ACT scores, whereas age was associated with CAT scores. More interestingly, however, was that both tools shared some determinants, such as the degree of dyspnoea and the level of anxiety and depression measured by the HADS questionnaire.

The association of ACT but not CAT scores with previous exacerbations may be related to the finding that the ACT scores were better determinants of the frequent exacerbator phenotype, with an AUC of 0.70, compared with 0.65 with the CAT. These differences are small, and the 95% CIs overlap, but they suggest that the ACT may be more determined by exacerbations than the CAT, perhaps due to the questions about the use of rescue treatment that are included in the ACT but not included in the CAT.

The significant association and the moderate and significant correlation observed between the HADS scores and both the ACT and CAT scores indicate the strong influence of mood on the scores of both questionnaires. Recent large studies have already shown this relationship. In another study in Spain, of 684 COPD patients, the level of depressive symptoms measured by the short Beck Depression Inventory explained 38% of the variance of the CAT scores [37], and a study of 3452 COPD patients from Eastern European countries observed that the clinical diagnosis of depression was the second most important variable significantly and independently associated with CAT scores, only after the degree of dyspnoea [38]. Our results suggest that psychological factors are also determinant in patients with ACO and may have a similar influence in the ACT and CAT scores.

We were also interested in comparing the classification of patients according to the established cut-off for poor asthma control (<20 units in the ACT) and a high level of COPD symptoms (>10 units in the CAT). Consistently, the CAT classified more participants as highly symptomatic compared to those poorly controlled as classified by the ACT. For example, among those with no exacerbations in the previous year, 53% had a high level of symptoms according to the CAT, but only 38% were not controlled, according to the ACT. Likewise, among patients with BODEx values of 3 or higher, 87.3% had high levels of symptoms according to the CAT, but only 74.5% were considered not controlled according to the ACT. These results indicate that the use of the CAT would result in a larger request for the intensification of treatment in ACO patients compared to the ACT.

Regarding treatment in patients with “asthma + COPD”, defined by similar criteria as in our population, Lommatzsch et al. [39] used the ACT to identify changes in disease control with the use of various biologics. So far, there is no biologic approved for use in COPD, but some of these products can be used in asthma, including asthma with some trends of COPD. The previously mentioned study included 20 asthmatics, smokers or former smokers of more than 10 pack-years and with FEV1/FVC values of <0.7 and observed significant improvements of a median of 7 units in the ACT scores with five different biologics; however, the authors did not use the CAT to evaluate symptoms in their patients. On the contrary, the CAT questionnaire was used in the METREO study, which investigated the efficacy of mepolizumab in patients with “type 2 COPD”, but the differences in the CAT scores between active treatment and placebo patients were not significant [40]. The future use of biologics in patients with “COPD and type 2 inflammation” or in “asthma + COPD” may require more information about the reliability and the prognostic values of both ACT and CAT in this group of patients.

The present study has several limitations. First, it was a cross-sectional study, with a single visit, without subsequent follow-up of the patients, especially in terms of symptoms and exacerbations. A follow-up of at least one year would allow observation of whether the correlation between the two tests is maintained over time and evaluate the prognostic value of the ACT and CAT scores for exacerbations. Another limitation is the use of a single definition of the ACO phenotype when including patients in this study. It is possible that if other definitions had been used, the patients included would have presented different baseline characteristics.

5. Conclusions

In patients with ACO, both the ACT and CAT symptom questionnaires showed similar results, although the ACT was more related to exacerbations and the CAT classified more patients as high-impact compared to the ACT. Both questionnaires have common determinants, such as dyspnoea, anxiety and depression. Longitudinal studies are needed to assess which of the two questionnaires is a better predictor of outcomes in these patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, C.A., G.G., C.E., M.M. and M.B.; methodology, C.A., M.M., M.B. and C.E.; software, C.A., G.G. and C.E.; validation and formal analysis, C.A., C.E., M.B. and M.M.; investigation, C.E., C.A., G.G., F.J.C.-G., C.M.-R., A.P.-S., L.R.-P., E.C.-C., E.M.-M., A.B.-L., E.N.-S., B.A.-B., C.C.-L. and M.B.; resources and data curation, C.E., C.A., G.G., F.J.C.-G., C.M.-R., A.P.-S., L.R.-P., E.C.-C., E.M.-M., A.B.-L., E.N.-S., B.A.-B., C.C.-L. and M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M., C.A., G.G. and M.B.; writing—review and editing, C.E., C.A., G.G., F.J.C.-G., C.M.-R., A.P.-S., L.R.-P., E.C.-C., E.M.-M., A.B.-L., E.N.-S., B.A.-B., C.C.-L. and M.B. All authors contributed to the data analysis, the result interpretation and drafting and revising the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by an unrestricted grant from Laboratorios Esteve (Barcelona, Spain).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Albacete (Spain), number 11/2017, 30 November 2017, as the coordinating centre and by all the other participating centres.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Cristina Aljama is a recipient of a SEPAR (Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery) 2023–2024 Research Fellowship.

Conflicts of Interest

Cristina Aljama has received speaker fees from FAES farma, Zambon, GSK and CSL Behring. Galo Granados has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Zambon and GlaxoSmithKline. Marc Miravitlles has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Kamada, Takeda, Zambon, CSL Behring, Specialty Therapeutics, Janssen, Grifols and Novartis; consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Atriva Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, BEAM Therapeutics, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, CSL Behring, Ferrer, Inhibrx, Menarini, Mereo Biopharma, Spin Therapeutics, Specialty Therapeutics, ONO Pharma, Palobiofarma SL, Takeda, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Zambon, Zentiva and Grifols; and research grants from Grifols. Miriam Barrecheguren has received speaker fees from CSL Behring, Grifols, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline and Menarini and consulting fees from CSL Behring and Boehringer Ingelheim.

References

- Castillo, E.G.; Pérez, T.A.; Peláez, A.; González, P.P.; Miravitlles, M.; Alfageme, I.; Casanova, C.; Cosío, B.G.; de Lucas, P.; García-Río, F.; et al. Trends of COPD in Spain: Changes Between Cross Sectional Surveys 1997, 2007 and 2017. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2023, 59, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, D.S.; Rabe, K.F. The asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekov, E.; Nuñez, A.; Sin, D.D.; Ichinose, M.; Rhee, C.K.; Maselli, D.J.; Coté, A.; Ulrik, C.S.; Maltais, F.; Anzueto, A.; et al. Update on Asthma-COPD Overlap (ACO): A Narrative Review. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2021, 16, 1783–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christenson, S.A.; Steiling, K.; van den Berge, M.; Hijazi, K.; Hiemstra, P.S.; Postma, D.S.; Lenburg, M.E.; Spira, A.; Woodruff, P.G. Asthma-COPD overlap: Clinical relevance of genomic signatures of Type 2 inflammation in COPD. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 191, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardin, M.; Cho, M.; McDonald, M.-L.; Beaty, T.; Ramsdell, J.; Bhatt, S.; van Beek, E.J.; Make, B.J.; Crapo, J.D.; Silverman, E.K.; et al. The clinical and genetic features of COPD-asthma overlap syndrome. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 44, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.M.; Sin, D.D. Asthma-COPD overlap syndrome: Pathogenesis, clinical features, and therapeutic targets. BMJ 2017, 358, j3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcázar-Navarrete, B.; Díaz-Lopez, J.M.; García-Flores, P.; Ortega-Antelo, M.; Aguilar-Cruz, I.; Ruiz-Rodríguez, O.; Santiago-Diaz, P.; Palacios, P.J.R. T2 Biomarkers as Predictors of Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2022, 58, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, V.; Álvarez, F.; Calle, M.; Casanova, C.; Cosío, B.G.; López-Viña, A.; de Llano, L.P.; Quirce, S.; Román-Rodríguez, M.; Soler-Cataluña, J.J.; et al. Consensus on the Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS) between the Spanish COPD Guidelines (GesEPOC) and the Spanish Guidelines on the Management of Asthma (GEMA). Arch. Bronconeumol. 2017, 53, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koblizek, V.; Chlumsky, J.; Zindr, V.; Neumannova, K.; Zatloukal, J.; Zak, J.; Sedlak, V.; Kocianova, J.; Zatloukal, J.; Hejduk, K.; et al. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Official diagnosis and treatment guidelines Biomed of the Czech Pneumological and Phthisiological society: A novel phenotypic approach to COPD with patient oriented care. Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky Olomouc. Czech Repub. 2013, 157, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankaanranta, H.; Harju, T.; Kilpeläinen, M.; Mazur, W.; Lehto, J.T.; Katajisto, M.; Peisa, T.; Meinander, T.; Lehtimäki, L. Diagnosis and pharmacotherapy of Stable Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: The Finish Guidelines. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2015, 116, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahboub, B.; Vats, M.; Alzaabi, A.; Iqbal, M.N.; Safwat, T.; Al-Hurish, F.; Miravitlles, M.; Singh, D.; Al-Asad, K.; Zein-El-Dine, S.; et al. Joint Statament for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for Gulf Cooperation Council countries and Middle East-North Africa region. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2017, 12, 2869–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, J.A.; Nibber, A.; Chisholm, A.; Price, D.; Bateman, E.D.; Bjermer, L.; van Boven, J.F.M.; Brusselle, G.; Costello, R.W.; Dandurand, R.J.; et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Asthma–Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Overlap in Routine Primary Care Practices. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2019, 16, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosio, B.G.; Soriano, J.B.; López-Campos, J.L.; Calle-Rubio, M.; Soler-Cataluna, J.J.; De-Torres, J.P.; Marín, J.M.; Martínez-Gonzalez, C.; de Lucas, P.; Mir, I.; et al. Defining the Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome in a COPD Cohort. Chest 2016, 149, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, L.C.; Eraso, C.C.; Ruiz-Duque, B.; Arranz, M.A.; Martín, E.M.; Acuña, C.C.; Lopez-Campos, J.L. Deconstructing Phenotypes in COPD: An Analysis of the TRACE Cohort. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2022, 58, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurst, K.E.; Rheault, T.R.; Edwards, L.; Tal-Singer, R.; Agusti, A.; Vestbo, J. A comparison of COPD patients with and without ACOS in the ECLIPSE study. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 47, 1559–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppi, P.; Kupiainen, H.; Lindqvist, A.; Tammilehto, L.; Kilpeläinen, M.; Kinnula, V.L.; Haahtela, T.; Laitinen, T. Overlap syndrome of asthma and COPD predicts low quality of life. J. Asthma. 2011, 48, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, A.M.B.; de Oca, M.M.; Pérez-Padilla, R.; Nadeau, G.; Wehrmeister, F.C.; Lopez-Varela, M.V.; Muiño, A.; Jardim, J.R.B.; Valdivia, G.; Tálamo, C.; et al. Increased risk of exacerbation and hospitalization in subjects with an overlap phenotype: COPD-asthma. Chest 2014, 145, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Makita, H.; Konno, S.; Shimizu, K.; Kimura, H.; Nishimura, M. Asthma-like features and clinical course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. An analysis from the Hokkaido COPD cohort study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 194, 1358–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.W.; Harding, G.; Berry, P.; Wiklund, I.; Chen, W.H.; Kline Leidy, N. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 34, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustí, A.; Celli, B.R.; Criner, G.J.; Halpin, D.; Anzueto, A.; Barnes, P.; Bourbeau, J.; Han, M.K.; Martinez, F.J.; de Oca, M.M.; et al. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2023 Report: GOLD Executive Summary. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2023, 59, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miravitlles, M.; Calle, M.; Molina, J.; Almagro, P.; Gómez, J.-T.; Trigueros, J.A.; Cosío, B.G.; Casanova, C.; López-Campos, J.L.; Riesco, J.A.; et al. Spanish COPD Guidelines (GesEPOC) 2021: Updated Pharmacological treatment of stable COPD. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2022, 58, 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, R.A.; Sorkness, C.A.; Kosinski, M.; Schatz, M.; Li, J.T.; Marcus, P.; Murray, J.J.; Pendergraft, T.B. Development of the asthma control test: A survey for assessing asthma control. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004, 113, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestall, J.C.; Paul, E.A.; Garrod, R.; Garnham, R.; Jones, P.W.; Wedzicha, J.A. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1999, 54, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divo, M.; Cote, C.; de Torres, J.P.; Casanova, C.; Marin, J.M.; Pinto-Plata, V.; Zulueta, J.; Cabrera, C.; Zagaceta, J.; Hunninghake, G.; et al. Comorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 186, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler-Cataluña, J.J.; Martínez-García, M.A.; Sánchez, L.S.; Tordera, M.P.; Sánchez, P.R. Severe exacerbations and BODE index: Two independent risk factors for death in male COPD patients. Respir. Med. 2009, 103, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.J.; Blanch, J.; Peri, J.M.; De Pablo, J.; Pintor, L.; Bulbena, A. A validation study of the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) in a Spanish population. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2003, 25, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, X.; Roset, M.; Monserrat, S.; Herdman, M.; Segura, A. La versión española del EuroQoL: Descripción y aplicaciones. Med. Clin. 1999, 112, 79–86. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Esquinas, C.; Ramon, M.A.; Nuñez, A.; Molina, J.; Quintano, J.A.; Roman-Rodríguez, M.; Naberan, K.; Llor, C.; Roncero, C.; Miravitlles, M.; et al. Correlation between disease severity factors and EQ-5D utilities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, A.E.; Spruit, M.A.; Troosters, T.; Puhan, M.A.; Pepin, V.; Saey, D.; McCormack, M.C.; Carlin, B.W.; Sciurba, F.C.; Pitta, F.; et al. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society technical standard: Field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 44, 1428–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsiligianni, I.G.; van der Molen, T.; Moraitaki, D.; Lopez, I.; Kocks, J.W.; Karagiannis, K.; Siafakas, N.; Tzanakis, N. Assessing health status in COPD. A head-to-head comparison between the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) and the Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ). BMC Pulm. Med. 2012, 12, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Ringbaek, T.; Martinez, G.; Lange, P. A comparison of the assessment of quality of life with CAT, CCQ, and SGRQ in COPD patients participating in pulmonary rehabilitation. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2012, 9, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dijk, B.C.P.; Svedsater, H.; Heddini, A.; Nelsen, L.; Balradj, J.S.; Alleman, C. Relationship between the Asthma Control Test (ACT) and other outcomes: A targeted literature review. BMC Pulm. Med. 2020, 20, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddel, H.K.; Bacharier, L.B.; Bateman, E.D.; Brightling, C.E.; Brusselle, G.G.; Buhl, R.; Cruz, A.A.; Duijts, L.; Drazen, J.M.; FitzGerald, J.M.; et al. Global Initiative for Asthma Strategy 2021. Executive Summary and Rationale for Key Changes. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2022, 58, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lommatzsch, M.; Brusselle, G.G.; Canonica, G.W.; Jackson, D.J.; Nair, P.; Buhl, R.; Virchow, J.C. Disease-modifying anti-asthmatic drugs. Lancet 2022, 399, 1664–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miravitlles, M.; Molina, J.; Quintano, J.A.; Campuzano, A.; Pérez, J.; Roncero, C. Depressive status explains a significant amount of the variance in COPD assessment test (CAT) scores. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2018, 13, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miravitlles, M.; Koblizek, V.; Esquinas, C.; Milenkovic, B.; Barczyk, A.; Tkacova, R.; Somfay, A.; Zykov, K.; Tudoric, N.; Kostov, K.; et al. Determinants of CAT (COPD Assessment Test) scores in a population of patients with COPD in central and Eastern Europe: The POPE study. Respir. Med. 2019, 150, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lommatzsch, M.; Mohme, S.N.; Stoll, P.; Virchow, J.C. Response to Various Biologics in Patients with Both Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Respiration 2023, 102, 986–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavord, I.D.; Chanez, P.; Criner, G.J.; Kerstjens, H.A.; Korn, S.; Lugogo, N.; Martinot, J.-B.; Sagara, H.; Albers, F.C.; Bradford, E.S.; et al. Mepolizumab for Eosinophilic Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1613–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).