Abstract

Congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) is the most common cause of congenital infection and the leading cause of non-genetic sensorineural hearing loss in childhood. While treatment trials have been conducted in symptomatic children, defining asymptomatic infection can be complex. We performed a scoping review to understand how infection severity is defined and treated globally, as well as the various indications for initiating treatment. We conducted an electronic search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library, using combinations of the following terms: “newborn”, “baby”, “child”, “ganciclovir”, “valganciclovir”, and “cytomegalovirus” or “CMV”. We included eligible prospective and retrospective studies, case series, and randomized clinical trials (RCTs) published up to May 2024. A total of 26 studies were included, of which only 5 were RCTs. There was significant heterogeneity between studies. The most commonly considered criteria for symptomatic infection were microcephaly (23/24 studies), abnormal neuroimaging (22/24 studies), chorioretinitis/ocular impairment (21/24 studies), and hearing impairment (20/24 studies). Two studies also included asymptomatic newborns in their treatment protocols. Outcome measures varied widely, focusing either on different hearing assessments or neurocognitive issues. Our literature analysis revealed significant variability and heterogeneity in the definition of symptomatic cCMV infection and, consequently, in treatment approaches. A consensus on core outcomes and well-conducted RCTs are needed to establish treatment protocols for specific groups of newborns with varying manifestations of cCMV.

Keywords:

cytomegalovirus; ganciclovir; valganciclovir; neurological outcome; hearing; neutropenia; neonates 1. Introduction

Congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) is the most common cause of congenital infection in developed countries [1]. Although cCMV infection can sometimes present as a severe, systemic, life-threatening disseminated disease, such cases are relatively rare and can be treated with a six-week course of intravenous ganciclovir (GC), oral valganciclovir (VGC), or a combination of initial GC followed by VGC [2].

More commonly, cCMV infection is clinically asymptomatic. However, even in asymptomatic cases, cCMV infection can be associated with significant outcomes. It is recognized as the leading cause of non-genetic sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) in childhood, regardless of infection severity [1,3]. Approximately 25% of SNHL cases in children up to four years old are attributed to cCMV [4]. Infants with symptomatic infections at birth are at higher risk of developing late-onset SNHL (LO-SNHL), with up to one-third affected, but asymptomatic newborns can also develop this condition during childhood [5,6]. Most cases of LO-SNHL occur before three years of age [6]. Additionally, increasing reports highlight neurocognitive problems in these children during their school years [7,8].

For these reasons, researchers focusing on cCMV and its outcomes have devoted significant attention to strategies that may prevent the long-term negative effects of the infection. A clinical trial involving symptomatic children with central nervous system (CNS) involvement and/or SNHL at birth demonstrated that antiviral treatment with ganciclovir or valganciclovir may prevent hearing deterioration [9,10]. However, evidence on the effectiveness of treatment in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic cCMV cases remains limited [11]. To complicate matters further, the definition of asymptomatic or mild cCMV infection can vary, especially with the advent of increasingly advanced diagnostic tools. For example, a clinically healthy newborn, who years ago might have been classified as asymptomatically infected, could today fall under a different classification if a brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were performed. This reflects the evolving criteria and the challenges associated with interpreting MRI findings in newborns. An isolated premature delivery of a small-for-gestational age (SGA) newborn may either be unrelated to maternal CMV infection or could indicate symptomatic infection. To date, these dilemmas have not been standardized or agreed upon internationally. As a result, therapeutic practices vary widely across the world, influenced by local guidelines and expert opinions. Some experts even recommend antiviral treatment for asymptomatic infections, despite the lack of strong supporting evidence [12,13].

To further investigate these issues, we conducted a scoping review of the literature to understand how cCMV infection severity is defined and how the infection is treated globally, as well as the various indications for initiating treatment. This study aims to provide researchers and policymakers with insights into the current variability in practice and to lay the groundwork for addressing uncertainties and standardizing clinical care and research priorities worldwide.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

The goal of our scoping review is to provide a comprehensive overview of the current literature on a broad neonatal topic. Initially, we aimed to conduct a meta-analysis; however, because of the heterogeneity in the published studies, a scoping review was deemed the most appropriate methodological approach. We followed the guidelines provided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist [14].

The search strategy was proposed by a single author (GB) and discussed and approved by the entire team. It was based on a combination of the following terms: “newborn”, “baby”, “child”, “ganciclovir”, “valganciclovir”, and “cytomegalovirus” or “CMV”. We conducted the search using electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library) through customized search queries. Additionally, the references of the included articles were reviewed to identify other relevant studies. The references were regularly updated throughout the drafting of this review.

We included prospective and retrospective studies, case series, and randomized clinical trials (RCTs) published up to May 2024. Case reports and editorials were excluded, and only articles published in English were considered eligible. The main research questions of this scoping review were as follows:

How is symptomatic infection defined globally?

What are the global indications for treating cCMV infection?

What are the outcomes (hearing and neurological) and side effects of cCMV treatment?

2.2. Search Screening and Data Extraction

After conducting the search, the studies were exported to Rayyan for screening. The first screening to remove duplicates was carried out by one author (GB). Titles and abstracts of the studies identified through the search strategy were independently screened by four reviewers (RR, FT, CI) to identify studies for inclusion. Full texts of potentially eligible studies were retrieved and independently assessed for eligibility. Each researcher was blinded to the decisions of the other reviewers. Any disagreements regarding study eligibility were resolved through discussion, and in cases of unresolved disagreement, a third reviewer (GB) was consulted. Studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded.

Neurological outcomes were considered in terms of hearing and neurodevelopment. For each selected study, data were summarized in a table based on a pre-discussed data extraction form, which included details on the setting, authorship, year of publication, study design, treatment, definitions of cCMV and symptomatic infection, outcomes, and side effects. A separate table was created for RCTs. Additionally, treatment indications and the criteria for defining symptomatic cCMV were summarized in a specific data form.

3. Results

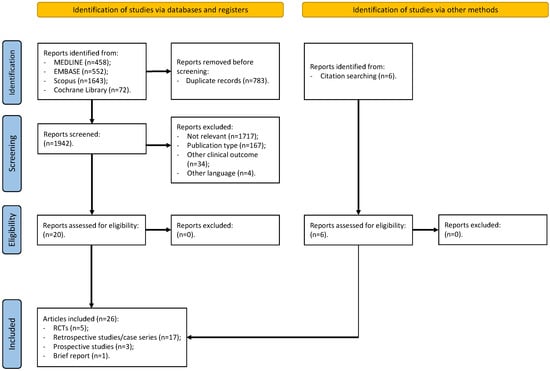

Using the search terms described in the Methods Section, we identified 2725 articles (Figure 1). Following the screening process, we selected 20 research articles. After manually reviewing the reference lists of studies from previous stages (including systematic reviews and meta-analyses), we added six additional documents. Thus, as shown in Figure 1, the final step of this scoping review included 26 studies [9,10,12,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37], consisting of five RCTs, 17 retrospective studies/case series, three prospective studies, and one brief report.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart. Figure legend: RCTs (randomized controlled trials).

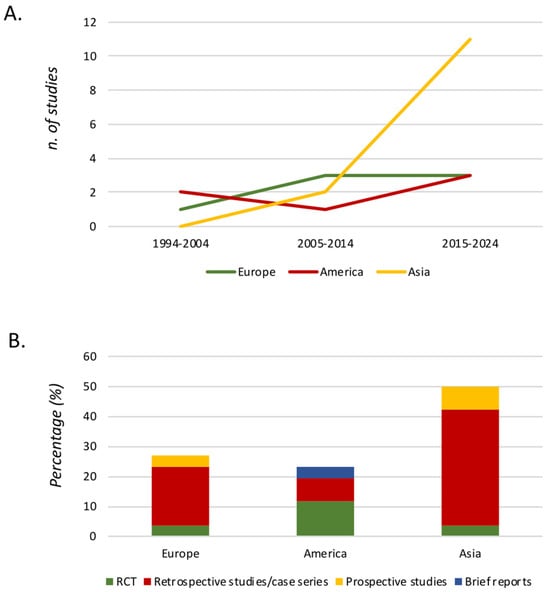

Figure 2 describes the distribution of the studies according to year of publication. It shows an increasing number of studies in the last decades, especially in Asia. Of these, seven (26.9%) were published in Europe, six (23.1%) were published in America, and the majority were published in Asia (13.50%), as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Graphical distribution of the studies according to year of publication. Figure legend. (A) Number of studies separated by continent and year of publication. (B) Typology of studies separated by continent. RCT (randomized controlled trial).

Table 1 describes the criteria used to diagnose and define symptomatic cCMV in the enrolled studies, separated by continent.

Table 1.

Diagnosis and definition of symptomatic cCMV used in the enrolled studies, separated by continent.

In addition, Table 2 provides a graphical representation of the criteria used to define symptomatic cCMV in the studies. Two studies did not report criteria for symptomatic infection (Table 2). The most commonly considered criteria for symptomatic infection were microcephaly (23/24 studies), abnormal neuroimaging (22/24 studies), chorioretinitis/ocular impairment (21/24 studies), and hearing impairment (20/24 studies). The least frequently considered criteria were abnormal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) findings (7/24 studies) and clinical neurological abnormalities (6/24 studies).

Table 2.

Criteria used to define symptomatic cCMV in the enrolled studies, separated by continent.

In Table 3, we summarize the treatment indications considered in the studies included in our scoping review. Two studies also included asymptomatic newborns in their treatment protocols. The treatment protocol was not well specified in three studies, while one study treated all newborns with severe neurological symptoms, and another study treated patients under compassionate use. The remaining 19 studies treated only symptomatic newborns.

Table 3.

Indication for treatment used in the enrolled studies.

The treatments used in the studies are summarized in Table 4. There was some heterogeneity between the studies. While the majority administered IV GC, comparing two different protocols in terms of dosage and timing of administration, some studies used IV GC followed by oral VGC or compared different protocols based on the dosage and duration of treatment with either GC/VGC or VGC alone. Additionally, we described the neurological and hearing outcomes, as well as the side effects, associated with the two treatment protocols used in the studies.

Table 4.

Hearing outcomes, neurological outcomes, and side effects reported in the enrolled studies.

With the aim of conducting a sub-meta-analysis focused on RCTs, we described the outcomes (specifically hearing, neurodevelopment, and side effects) in Table 5. Hearing outcomes were assessed in three out of five RCTs, while two out of five RCTs evaluated long-term neurological outcomes. The most commonly studied side effect was neutropenia, reported in all five RCTs. However, we decided not to perform a meta-analysis because of the significant variability in treatment protocols, methodologies, and outcomes across the enrolled RCTs.

Table 5.

Enrolled randomized controlled studies.

4. Discussion

In this scoping review, we analyzed the extensive literature on the treatment of cCMV, with a specific focus on understanding how infection severity is defined and how it is treated globally. We also examined the criteria used to decide when to initiate treatment. Our primary aim was to determine whether a standardized protocol for best practices could be established to promptly define symptomatic cCMV infection and treat affected newborns in a way that improves both short- and long-term outcomes. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic scoping review to address these perspectives with clinical implications.

Despite growing interest in this topic over the past decades, only five RCTs were published up to May 2024 [9,10,15,22,36], each involving different populations and outcomes. This represents a significant gap with important implications for daily clinical practice. It is known that neonates with asymptomatic cCMV infection (approximately 10% of cases) generally have better long-term outcomes compared with children with symptomatic infection [38,39]. Because of the potential toxicity of antiviral drugs, treatment is currently recommended only for symptomatic cases [40]. However, our scoping review revealed significant variability and heterogeneity in the definition of symptomatic cCMV infection, leading to differences in treatment indications across centers. Varying definitions of symptomatic disease can result in different interpretations of which infants might benefit most from antiviral treatment, thus influencing clinical decisions based on the perceived risks and benefits.

Moreover, asymptomatic cCMV can also cause SNHL during early childhood, with variable onset, progression, and severity [38,39]. Unfortunately, no clinical, laboratory, or imaging features are currently able to predict this risk reliably [39]. As a result, it remains unclear whether clinically well-appearing newborns with cCMV and isolated SNHL should receive antiviral treatment.

While most centers include the classic signs and symptoms of severe cCMV in their definition of symptomatic infection (such as microcephaly, chorioretinitis, cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities, and hematological abnormalities), there is greater variability when it comes to abnormal neuroimaging or hearing impairment. For instance, how should we classify a clinically well-appearing cCMV newborn with mild audiological impairment or isolated white matter abnormalities? Is this a symptomatic or asymptomatic infection, and should such cases be treated? Historically, clinical symptoms alone were used to define symptomatic infection. However, with the increasing availability of newborn hearing screening and advanced imaging (including ultrasound and the growing use of MRI), there is ongoing debate about whether isolated abnormalities should be considered part of symptomatic infection and treated accordingly.

Chung et al. investigated the benefits of antiviral treatment for children with isolated hearing loss and clinically inapparent cCMV in a nonrandomized trial published in May 2024 [41]. They found that children with inapparent cCMV and hearing loss who were treated with VGC experienced less hearing deterioration at 18 to 22 months of age compared with the control group [41]. These results led to the implementation (edition 2024) of recent European guidelines for the management of cCMV infection. This update suggests the benefit of treatment as soon as possible and before 1 to 3 months of age also for infants with isolated SNHL [42]. However, these points are critical, as SNHL is the most common long-term outcome of cCMV infection, and recent studies suggest that even isolated brain MRI abnormalities might be predictive of this outcome. A recent retrospective, single-center observational study, which included 225 patients with cCMV who underwent neonatal brain MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging between 2007 and 2020, found that the general white matter apparent diffusion coefficient was significantly higher in patients with neonatal hearing loss and cognitive or motor impairment (p < 0.05) [43]. In another study, abnormal white matter was associated with neonatal hearing loss and lower motor scores, with a tendency towards impaired cognitive development [44]. Similarly, a smaller Spanish study of 36 patients reported that MRI brain abnormalities were more frequent in newborns with SNHL (11 of the 36 patients had MRI abnormalities and SNHL, p = 0.004) [45].

In a larger Spanish study involving 160 infants with cCMV (103 symptomatic), temporal-pole white matter abnormalities, rather than the extent of white matter abnormalities, were associated with moderate/severe disability (OR 7.8; 1.4–42.8), specifically severe SNHL or SNHL combined with other moderate/severe disabilities (OR 16.2; 1.8–144.9) [46]. A smaller series of 17 patients in the United States showed that most infants whose CMV infections were identified after failing newborn hearing screening had abnormal brain MRIs [47]. Conversely, a small study from the Republic of Korea, involving 31 patients, did not find any association between MRI findings and SNHL [48].

While these findings are noteworthy, they raise the question of whether all newborns with cCMV, including those with clinically asymptomatic infections, should undergo neonatal MRI. Although MRI shows promise as a prognostic tool, routine use may not be feasible in all settings because of its high cost (both for the test itself and the extended hospital stay required, even for healthy newborns), as well as the potential need for sedation, making its widespread application challenging. Additionally, interpreting brain MRI findings in newborns can be difficult, as some results may reflect physiological delays in maturation rather than specific abnormalities associated with cCMV [49]. Lastly, whether children with a clinically asymptomatic infection but with brain MRI abnormalities should be treated with antivirals still needs to be addressed. However, as shown in Table 3 of our study, some authors use brain MRI abnormalities as an indication of treatment; however, this is not specifically mentioned in any guidelines, nor is there evidence of any potential benefits.

In fact, trials or observational studies that have treated patients historically used other definitions as inclusion criteria for treatment; nevertheless, it seems that clinicians translate those historical findings to expand indications for treatment. Nowadays, GC, and its oral pro-drug VGC, are the two antiviral drugs administered to treat symptomatic cCMV. Other potential drugs for cCMV disease are Foscarnet and Cidofovir, but these are not routinely administered. Myelosuppression, especially neutropenia, is the most frequent side effects associated with GC and VGC [50]. Foscarnet and Cidofovir result in renal toxicity and electrolyte imbalances [50]. To the best of our knowledge, there are no RCTs that evaluated the treatment with Foscarnet or Cidofovir for newborns with cCMV infection. In addition, there is an ongoing phase 1 trial that is evaluating the role of oral Letermovir as a potential alternative to VCG for symptomatic cCMV infection (NCT06118515, ClinicalTrials.gov).

Nigro et al. conducted an RCT comparing infants with symptomatic cCMV treated with two different IV ganciclovir (GC) protocols (Group A: 5 mg/kg twice daily for 2 weeks vs. Group B: 7.5 mg/kg twice daily for 2 weeks, followed by 10 mg/kg three times weekly for 3 months) [15]. The authors did not assess hearing or neurological outcomes and found no statistical difference in terms of neutropenia between the groups. However, the study had a very small sample size (six infants in each group).

In 2003, Kimberlin et al. enrolled 100 neonates (≥32 weeks and ≥1200 g at birth) with symptomatic cCMV involving the CNS, defined by microcephaly, intracranial calcifications, abnormal CSF for age, chorioretinitis, and/or hearing deficits [9]. They compared two groups, one treated with IV GC (6 mg/kg every 12 h for 6 weeks) and the other untreated. The authors found that GC therapy prevented hearing deterioration at 6 months and might also prevent deterioration after 1 year, despite two-thirds of the treated newborns developing neutropenia during therapy.

In a follow-up study, Oliver et al. evaluated neurological outcomes using the Denver II scale at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months [22]. Their results confirmed previous findings on the benefits of GC therapy for symptomatic cCMV, including its toxicity, particularly neutropenia. In 2015, the same authors evaluated two different oral valganciclovir (VGC) treatment protocols in the same population of neonates (≥32 weeks and ≥1200 g at birth). Group A received 16 mg/kg of oral VGC every 12 h for 6 months, while Group B received 16 mg/kg of oral VGC every 12 h for 6 weeks, followed by a placebo up to 6 months [10]. They found that treating symptomatic cCMV with VGC for 6 months, compared with 6 weeks, did not improve hearing in the short term but appeared to improve hearing and developmental outcomes after 12 months, as measured by the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, third edition. The risk of neutropenia was similar between the two groups after 6 weeks and up to 6 months, suggesting that the highest risk occurs during the first 6 weeks of treatment.

The most recent RCT was conducted by Yang et al. [36]. They compared symptomatic newborns treated with IV GC (6 mg/kg every 12 h for 6 weeks) and oral VGC (16 mg/kg every 12 h for 6 weeks). No differences were found in hearing outcomes or side effects between the two groups, although the oral route of VGC was more acceptable for neonates.

Our study should be interpreted with some limitations. This is a scoping review that aims to better describe the definition of cCMV and evaluate the criteria for the treatment of cCMV across the world and the best therapy weighing the outcomes versus the side effects. We decided not to perform a meta-analysis because of the heterogeneity in the published studies in terms of the criteria for the diagnosis and treatment of cCMV (Table 2 and Table 3). We systematically collected evidence with a robust research strategy and after a deep evaluation and discussion between the authors. We selected articles published in English up to May 2024; thus, it is possible that some gray literature or articles published after May 2024 were analyzed. Despite its limitations, the current literature does not allow us to determine the best antiviral therapy for cCMV for several reasons. First, very few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been published, and these are the best type of study for evaluating treatments. It is not possible to determine the most effective drug therapy based on observational or retrospective studies. A key finding of our review is that the included studies used different outcomes, measured with different methods, neurological scales, or in varying populations. Even when assessing audiological outcomes, which should theoretically be the easiest to measure, different authors employed various methods at different timepoints. Neurological clinical signs were considered for the definition of symptomatic patients in only 6 studies [12,15,18,20,21,37]. Additionally, treatment protocols differed between studies in terms of dosage and duration of therapy.

One of the most significant limitations is that the published RCTs did not include asymptomatic newborns. To our knowledge, only two retrospective studies included asymptomatic newborns with congenital infection in their treatment protocols [12,16]. Lackner et al. treated asymptomatic cCMV with IV ganciclovir (10 mg/kg for 21 days) [16], finding improved outcomes for treated infants but no differences in long-term neurological outcomes. Turriziani Colonna et al. evaluated the long-term audiological, visual, neurocognitive, and behavioral outcomes in both symptomatic and asymptomatic cCMV patients treated with oral valganciclovir (VGC) [12], showing that both groups developed long-term sequelae. However, their study lacked a control group. While these studies suggest that asymptomatic cCMV might benefit from antiviral treatment, they do not provide conclusive evidence, as they were retrospective with small sample sizes. Given the differences in pharmacological approaches and study populations (asymptomatic vs. symptomatic, with varying definitions of symptomatic infections), we believe that the available data do not meet the minimum criteria necessary to perform a meta-analysis on this outcome.

Further complicating treatment decisions, valacyclovir was recently approved for use in pregnant women with CMV infection to prevent vertical transmission to the newborn [51]. A recent meta-analysis of three RCTs, involving 527 women, demonstrated that oral valacyclovir reduces the risk of vertical transmission (adjusted OR 0.34, 95% CI, 0.18–0.61), whether administered during the periconceptional period (adjusted OR 0.34; 95% CI, 0.12–0.96) or the first trimester of pregnancy (adjusted OR 0.35; 95% CI, 0.16–0.76) [51]. This suggests that in the future, an increasing number of newborns with cCMV will be born to mothers treated with valacyclovir during pregnancy, raising questions about whether the criteria used during the pre-valacyclovir era will still apply. For instance, will these children be at risk for late-onset SNHL? If they are asymptomatic, should they still receive VGC despite their in utero exposure to valacyclovir? Many questions remain unanswered.

As we gain more experience with VGC, and as most side effects appear to be minor and transient, as shown in Table 4, there is potential to expand the use of VGC to asymptomatic newborns with isolated abnormalities. However, to achieve this, we need a new generation of RCTs that are appropriately designed, using rigorous clinical definitions of infection severity and standardized outcome measures. A key priority for scientific societies involved with cCMV should be the development of a core outcome set for cCMV trials, ensuring that data from different centers can be combined and compared.

5. Conclusions

Our scoping review showed that interest in studying cCMV treatment is growing globally. However, we identified significant variability and heterogeneity in the definition of symptomatic cCMV infection, leading to differences in treatment decisions. Moreover, therapeutic protocols varied between studies, and outcomes (such as hearing function) were measured using different methods, limiting the ability to compare and interpret results. Thus, there is an urgent need for consensus on defining symptomatic and asymptomatic cCMV infection, using the most advanced methodologies available (e.g., brain MRI in certain settings). Additionally, a core outcome set should be developed, with pre-specified outcomes that can be used across research centers to ensure comparability. These definitions will be crucial for designing new therapeutic RCTs to improve the short- and long-term outcomes for children with cCMV.

Author Contributions

G.B., D.B. and S.E.: conception and design of this work; G.B. and D.B.: writing the first draft of this manuscript; G.B., R.R., F.T. and C.I.: analysis of the literature; S.P. gave a substantial scientific contribution; S.E.: revised the final document and made a substantial scientific contribution. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

| cCMV | congenital cytomegalovirus. |

| CFS | cerebrospinal fluid. |

| CNS | central nervous system. |

| GC | ganciclovir. |

| IV | intravenously. |

| LO-SNHL | late-onset sensorineural hearing loss. |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging. |

| OR | orally. |

| RCTs | randomized clinical trials. |

| SGA | small-for-gestational age. |

| SNHL | sensorineural hearing loss. |

| VGC | valganciclovir. |

References

- Kenneson, A.; Cannon, M.J. Review and Meta-analysis of the Epidemiology of Congenital Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Infection. Rev. Med. Virol. 2007, 17, 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsico, C.; Kimberlin, D.W. Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: Advances and Challenges in Diagnosis, Prevention and Treatment. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2017, 43, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dollard, S.C.; Grosse, S.D.; Ross, D.S. New Estimates of the Prevalence of Neurological and Sensory Sequelae and Mortality Associated with Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. Rev. Med. Virol. 2007, 17, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, C.C.; Nance, W.E. Newborn Hearing Screening—A Silent Revolution. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 2151–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goderis, J.; De Leenheer, E.; Smets, K.; Van Hoecke, H.; Keymeulen, A.; Dhooge, I. Hearing Loss and Congenital CMV Infection: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2014, 134, 972–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goderis, J.; Keymeulen, A.; Smets, K.; Van Hoecke, H.; De Leenheer, E.; Boudewyns, A.; Desloovere, C.; Kuhweide, R.; Muylle, M.; Royackers, L.; et al. Hearing in Children with Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: Results of a Longitudinal Study. J. Pediatr. 2016, 172, 110–115.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesch, M.H.; Lauer, C.S.; Weinberg, J.B. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Children with Congenital Cytomegalovirus: A Systematic Scoping Review. Pediatr. Res. 2024, 95, 418–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korndewal, M.J.; Oudesluys-Murphy, A.M.; Kroes, A.C.M.; van der Sande, M.A.B.; de Melker, H.E.; Vossen, A.C.T.M. Long-term Impairment Attributable to Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2017, 59, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimberlin, D.W.; Lin, C.-Y.; Sánchez, P.J.; Demmler, G.J.; Dankner, W.; Shelton, M.; Jacobs, R.F.; Vaudry, W.; Pass, R.F.; Kiell, J.M.; et al. Effect of Ganciclovir Therapy on Hearing in Symptomatic Congenital Cytomegalovirus Disease Involving the Central Nervous System: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. J. Pediatr. 2003, 143, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimberlin, D.W.; Jester, P.M.; Sánchez, P.J.; Ahmed, A.; Arav-Boger, R.; Michaels, M.G.; Ashouri, N.; Englund, J.A.; Estrada, B.; Jacobs, R.F.; et al. Valganciclovir for Symptomatic Congenital Cytomegalovirus Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 933–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luck, S.E.; Wieringa, J.W.; Blázquez-Gamero, D.; Henneke, P.; Schuster, K.; Butler, K.; Capretti, M.G.; Cilleruelo, M.J.; Curtis, N.; Garofoli, F.; et al. Congenital Cytomegalovirus: A European Expert Consensus Statement on Diagnosis and Management. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2017, 36, 1205–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turriziani Colonna, A.; Buonsenso, D.; Pata, D.; Salerno, G.; Chieffo, D.P.R.; Romeo, D.M.; Faccia, V.; Conti, G.; Molle, F.; Baldascino, A.; et al. Long-Term Clinical, Audiological, Visual, Neurocognitive and Behavioral Outcome in Children with Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection Treated with Valganciclovir. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pata, D.; Buonsenso, D.; Turriziani-Colonna, A.; Salerno, G.; Scarlato, L.; Colussi, L.; Ulloa-Gutierrez, R.; Valentini, P. Role of Valganciclovir in Children with Congenital CMV Infection: A Review of the Literature. Children 2023, 10, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigro, G.; Scholz, H.; Bartmann, U. Ganciclovir Therapy for Symptomatic Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection Infants: A Two-Regimen Experience. J. Pediatr. 1994, 124, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, A.; Acham, A.; Alborno, T.; Moser, M.; Engele, H.; Raggam, R.B.; Halwachs-Baumann, G.; Kapitan, M.; Walch, C. Effect on Hearing of Ganciclovir Therapy for Asymptomatic Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: Four to 10 Year Follow Up. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2009, 123, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulon, I.; Naessens, A.; Faron, G.; Foulon, W.; Jansen, A.C.; Gordts, F. Hearing Thresholds in Children with a Congenital CMV Infection: A Prospective Study. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2012, 76, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rosal, T.; Baquero-Artigao, F.; Blázquez, D.; Noguera-Julian, A.; Moreno-Pérez, D.; Reyes, A.; Vilas, J. Treatment of Symptomatic Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection beyond the Neonatal Period. J. Clin. Virol. 2012, 55, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedlińska-Pijanowska, D.; Czech-Kowalska, J.; Kłodzińska, M.; Pietrzyk, A.; Michalska, E.; Gradowska, K.; Dobrzańska, A.; Kasztelewicz, B.; Gruszfeld, D. Antiviral Treatment in Congenital HCMV Infection: The Six-Year Experience of a Single Neonatal Center in Poland. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2020, 29, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturini, E.; Impagnatiello, L.; Chiappini, E.; Galli, L. Hearing Outcome and Virologic Characteristics of Children with Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection in Relation to Antiviral Therapy: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2023, 42, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, M.G.; Greenberg, D.P.; Sabo, D.L.; Wald, E.R. Treatment of Children with Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection with Ganciclovir. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2003, 22, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, S.E.; Cloud, G.A.; Sánchez, P.J.; Demmler, G.J.; Dankner, W.; Shelton, M.; Jacobs, R.F.; Vaudry, W.; Pass, R.F.; Soong, S.J.; et al. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes Following Ganciclovir Therapy in Symptomatic Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infections Involving the Central Nervous System. J. Clin. Virol. 2009, 46, S22–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrary, H.; Sheng, X.; Greene, T.; Park, A. Long-Term Hearing Outcomes of Children with Symptomatic Congenital CMV Treated with Valganciclovir. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 118, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.; Grosse, S.D.; Yockey, B.; Lanzieri, T.M. Ganciclovir and Valganciclovir Use Among Infants with Congenital Cytomegalovirus: Data From a Multicenter Electronic Health Record Dataset in the United States. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2022, 11, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, J.; Wolf, D.G.; Levy, I. Treatment of Symptomatic Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection with Intravenous Ganciclovir Followed by Long-Term Oral Valganciclovir. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2010, 169, 1061–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, J.; Attias, J.; Pardo, J. Treatment of Late-Onset Hearing Loss in Infants with Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. Clin. Pediatr. 2014, 53, 444–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilavsky, E.; Schwarz, M.; Pardo, J.; Attias, J.; Levy, I.; Haimi-Cohen, Y.; Amir, J. Lenticulostriated Vasculopathy Is a High-Risk Marker for Hearing Loss in Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infections. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2015, 104, e388–e394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilavsky, E.; Shahar-Nissan, K.; Pardo, J.; Attias, J.; Amir, J. Hearing Outcome of Infants with Congenital Cytomegalovirus and Hearing Impairment. Arch. Dis. Child. 2016, 101, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, K.; Morioka, I.; Nakamachi, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Imanishi, T.; Kawano, S.; Iwatani, S.; Koda, T.; Deguchi, M.; Tanimura, K.; et al. Neurological Outcomes in Symptomatic Congenital Cytomegalovirus-Infected Infants after Introduction of Newborn Urine Screening and Antiviral Treatment. Brain Dev. 2016, 38, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyano, S.; Morioka, I.; Oka, A.; Moriuchi, H.; Asano, K.; Ito, Y.; Yoshikawa, T.; Yamada, H.; Suzutani, T.; Inoue, N. Congenital Cytomegalovirus in Japan: More than 2 Year Follow up of Infected Newborns. Pediatr. Int. 2018, 60, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasternak, Y.; Ziv, L.; Attias, J.; Amir, J.; Bilavsky, E. Valganciclovir Is Beneficial in Children with Congenital Cytomegalovirus and Isolated Hearing Loss. J. Pediatr. 2018, 199, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziv, L.; Yacobovich, J.; Pardo, J.; Yarden-Bilavsky, H.; Amir, J.; Osovsky, M.; Bilavsky, E. Hematologic Adverse Events Associated with Prolonged Valganciclovir Treatment in Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2019, 38, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohyama, S.; Morioka, I.; Fukushima, S.; Yamana, K.; Nishida, K.; Iwatani, S.; Fujioka, K.; Matsumoto, H.; Imanishi, T.; Nakamachi, Y.; et al. Efficacy of Valganciclovir Treatment Depends on the Severity of Hearing Dysfunction in Symptomatic Infants with Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorfman, L.; Amir, J.; Attias, J.; Bilavsky, E. Treatment of Congenital Cytomegalovirus beyond the Neonatal Period: An Observational Study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2020, 179, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suganuma, E.; Sakata, H.; Adachi, N.; Asanuma, S.; Furuichi, M.; Uejima, Y.; Sato, S.; Abe, T.; Matsumoto, D.; Takahashi, R.; et al. Efficacy, Safety, and Pharmacokinetics of Oral Valganciclovir in Patients with Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. J. Infect. Chemother. 2021, 27, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Qiu, A.; Wang, J.; Pan, Z. Comparative Effects of Valganciclovir and Ganciclovir on the Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection and Hearing Loss: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Iran. J. Pediatr. 2022, 32, e118874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongwathanavikrom, N.B.; Lapphra, K.; Thongyai, K.; Vanprapar, N.; Chokephaibulkit, K. Ganciclovir Treatment in Symptomatic Congenital Cmv Infection at Siriraj Hospital: 11 Year-Review (2008 to 2019). J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2021, 104, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, K.B.; Boppana, S.B. Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. Semin. Perinatol. 2018, 42, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boppana, S.B.; Ross, S.A.; Fowler, K.B. Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: Clinical Outcome. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, S178–S181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiopris, G.; Veronese, P.; Cusenza, F.; Procaccianti, M.; Perrone, S.; Daccò, V.; Colombo, C.; Esposito, S. Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: Update on Diagnosis and Treatment. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, P.K.; Schornagel, F.A.J.; Soede, W.; van Zwet, E.W.; Kroes, A.C.M.; Oudesluys-Murphy, A.M.; Vossen, A.C.T.M. Valganciclovir in Infants with Hearing Loss and Clinically Inapparent Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: A Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. J. Pediatr. 2024, 268, 113945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leruez-Ville, M.; Chatzakis, C.; Lilleri, D.; Blazquez-Gamero, D.; Alarcon, A.; Bourgon, N.; Foulon, I.; Fourgeaud, J.; Gonce, A.; Jones, C.E.; et al. Consensus Recommendation for Prenatal, Neonatal and Postnatal Management of Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection from the European Congenital Infection Initiative (ECCI). Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 40, 100892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vande Walle, C.; Keymeulen, A.; Oostra, A.; Schiettecatte, E.; Dhooge, I.; Smets, K.; Herregods, N. Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Values of the White Matter in Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Neonatal Brain May Help Predict Outcome in Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. Pediatr. Radiol. 2024, 54, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vande Walle, C.; Keymeulen, A.; Oostra, A.; Schiettecatte, E.; Dhooge, I.J.; Smets, K.; Herregods, N. Implications of Isolated White Matter Abnormalities on Neonatal MRI in Congenital CMV Infection: A Prospective Single-Centre Study. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2023, 7, e002097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar Castellanos, M.; de la Mata Navazo, S.; Carrón Bermejo, M.; García Morín, M.; Ruiz Martín, Y.; Saavedra Lozano, J.; Miranda Herrero, M.C.; Barredo Valderrama, E.; Castro de Castro, P.; Vázquez López, M. Association between Neuroimaging Findings and Neurological Sequelae in Patients with Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. Neurologia 2022, 37, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarcón, A.; de Vries, L.S.; Parodi, A.; Arnáez, J.; Cabañas, F.; Steggerda, S.J.; Rebollo, M.; Ramenghi, L.; Dorronsoro, I.; López-Azorín, M.; et al. Neuroimaging in Infants with Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection and Its Correlation with Outcome: Emphasis on White Matter Abnormalities. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2024, 109, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hranilovich, J.A.; Park, A.H.; Knackstedt, E.D.; Ostrander, B.E.; Hedlund, G.L.; Shi, K.; Bale, J.F. Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Congenital Cytomegalovirus with Failed Newborn Hearing Screen. Pediatr. Neurol. 2020, 110, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, M.; Yum, M.-S.; Yeh, H.-R.; Kim, H.-J.; Ko, T.-S. Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings of Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection as a Prognostic Factor for Neurological Outcome. Pediatr. Neurol. 2018, 83, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vande Walle, C.; Keymeulen, A.; Schiettecatte, E.; Acke, F.; Dhooge, I.; Smets, K.; Herregods, N. Brain MRI Findings in Newborns with Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: Results from a Large Cohort Study. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 8001–8010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mareri, A.; Lasorella, S.; Iapadre, G.; Maresca, M.; Tambucci, R.; Nigro, G. Anti-Viral Therapy for Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: Pharmacokinetics, Efficacy and Side Effects. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016, 29, 1657–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzakis, C.; Shahar-Nissan, K.; Faure-Bardon, V.; Picone, O.; Hadar, E.; Amir, J.; Egloff, C.; Vivanti, A.; Sotiriadis, A.; Leruez-Ville, M.; et al. The Effect of Valacyclovir on Secondary Prevention of Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection, Following Primary Maternal Infection Acquired Periconceptionally or in the First Trimester of Pregnancy. An Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 230, 109–117.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).