Abstract

Background/Objectives: Sjögren’s disease (SjD) is an autoimmune disease causing irreversible damage to the exocrine glands but can have symptoms throughout the entire body. The aim of this study is to determine the prevalence of Sjogren’s disease (SjD) in the Netherlands, compare this with the prevalence for other countries in a systematic literature review. Methods: In the first part of this study, the prevalence of SjD was determined at two academic dental clinics in the Netherlands by electronically analysing patient records. In the second part of this study, a systematic literature search was performed in PubMed. Studies in the English language reporting prevalence ratios (PRs), incidence ratios (IRs) or sufficient data to calculate these parameters were included. Population-based studies and population surveys aiming to examine an entire geographic region or using a clearly defined sampling procedure were included. Review studies were excluded. Studies that did not report sufficient data or contained no original data were excluded. Included studies were assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa assessment scale. Results: At the dental clinic in Amsterdam, 76 SJD patients were identified among a patient population of 81941, resulting in a prevalence ratio of 93 per 100,000 (0.093%) patients. In Nijmegen, 21 SjD patients were identified in a total patient population of 14,240, resulting in a prevalence ratio of 147 per 100,000 (0.15%). Thirty-one studies were included in the systematic review. They varied in diagnostic criteria for SjD with the American-European Consensus Group (AECG) criteria being the most widely used. The reported prevalence ratio varied from 0.008% to 3.3%. The overall pooled prevalence ratio of SjD using the AECG criteria was 0.031%, while the pooled prevalence of SjD using the EU criteria was 0.029%. The overall pooled incidence ratio was 5.2 (95%CI 4.7 to 5.6) per 100,000 person-years. Conclusions: The estimated prevalence ratio of SjD in the Netherlands (0.09% to 0.15%) falls within the worldwide range but is higher than the worldwide pooled prevalence ratio.

1. Introduction

Sjögren’s disease (SjD) is a chronic and progressive autoimmune disease causing irreversible damage to the exocrine glands and is associated with the B and T lymphocyte infiltration of the affected glands [1,2]. Although SjD is a systemic disease and can have symptoms throughout the entire body, it mainly affects the lacrimal and salivary glands. The predominant symptoms are dry eyes, hyposalivation and xerostomia [2,3]. Other symptoms are fatigue, joint pain, vaginal dryness and depression [3,4,5,6]. Furthermore, among patients with SjD, the risk of B-cell lymphoma is 15 to 20 times higher than in the general population [6]. SjD can be divided into primary SjD and SjD associated with another rheumatic disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus [3,7]. Due to the decreased saliva secretion, the altered saliva composition [8] and the reduced capability of saliva to buffer, lubricate and perform antimicrobial activities, caries risk in SjD patients is increased [9,10]. SjD patients have an increased risk of root caries and caries on the labial and incisal surfaces of the teeth. Also, a diminished taste [11] and swallowing disorders [12] are frequently reported. Finally, SjD can increase the risk of Candidiasis and the inflammation of the oral mucosa [9]. In the early stages of SjD, salivary flow can be stimulated by the use of lozenges and chewing gums or systematic pharmacotherapies such as pilocarpine or cevimeline [13,14]. Alternatively, sialoendoscopy as a therapeutic procedure [15] and acupuncture [13,16] have also been reported to increase saliva production.

Worldwide, several studies have explored the prevalence of SjD, and large differences have been reported between different parts of the world. This could be related to ethnic and geographical differences [7,17]. Moreover, the use of different classification criteria to diagnose SjD could also explain these differences. Some studies use the International ‘Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems’ (ICD) code system, a globally used tool to classify diseases. The ICD system is primarily used for administrative purposes, such as tracking diseases, reimbursement and public health reporting. It does not define specific clinical criteria for the diagnosis of SjD but simply categorizes diseases based on existing definitions. Other frequently used diagnosis criteria are the EU-1993 and EU-1996, Copenhagen and San Diego criteria. For harmonization purposes, the American-European Consensus Group (AECG) proposed in 2002 a new set of criteria, based on previous research by Vitali and co-workers [18]. Finally, in 2016, the ACR/EULAR set of criteria was introduced, which excludes the most common differential diagnoses. It also differs substantially from the previous AECG criteria in that it considers systemic manifestations and introduced a weighted scoring system. [19] The EU-1993 and the San Diego and the Copenhagen criteria could be regard as more symptom-based criteria placing emphasis on patient-reported symptoms of dry eyes and dry mouth. In contrast, the EU-1996, the AECG and the 2016 ACR/EULAR criteria place more focus on objective tests including histopathological examination and antibody testing (anti-Ro/SS-A and anti-La/SS-B), moving away from reliance on subjective symptoms [20]. The use of different classification criteria and the broad nature of ICD coding can create substantial differences in the reported prevalence of Sjögren’s syndrome. More lenient or symptom-based criteria will often lead to higher prevalence estimates, while stringent, objective-based criteria that rely on specific test results will produce lower estimates. This discrepancy is influenced by varying access to diagnostic testing, changing classification standards over time and the administrative nature of the ICD coding system.

The prevalence of SjD in the Netherlands is unknown. Therefore, the aim of our study was to determine the prevalence of Sjögren’s disease at two academic dental clinics in the Netherlands and compare this prevalence with a worldwide systematic literature review of previous studies in other countries.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection for Prevalence Study

This study was approved on 21 November 2019 by the Internal Ethical Review Board of the Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA) under protocol number 201967. To determine the prevalence of SjD within the Academic Centre of Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA), the electronic health record system Axium (Exan group, Coquitlam, BC, Canada) was automatically searched as previously described [21] for the terms Sjögren, Sjogren, Sjögrens syndrome and Sjogrens syndrome. Only patients who visited the dental clinic in the period from 2010 up to 2019 were included.

In the prevalence study performed at RadboudUMC Nijmegen, patients were identified by an automated search in the electronic health record system Dentium EDU (Netpoint Group, Waalwijk, the Netherlands). The search term ‘Sjogren’ was used to identify patients who visited the dental clinic in the period from 2010 to 2019. Data about the diagnosis of SjD were extracted manually by reviewing the identified health records. In both dental clinics, the prevalence ratio was calculated by dividing the number of SjD patients identified by the total number of patients that enrolled in the clinic during these years.

2.2. Systematic Literature Review

2.2.1. Type of Studies

For this research, population-based studies and population surveys aiming to examine an entire geographic region or using a clearly defined sampling procedure were included. Review studies were excluded. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they reported prevalence ratios (PRs), incidence ratios (IRs) or sufficient data to calculate the PRs or IRs. Studies that did not report sufficient data or contained no original data were excluded.

2.2.2. Type of Participants

The selected studies included patients with primary SjD or SjD associated with another rheumatic disease.

2.2.3. Types of Outcome Measures

The prevalence of SjD was the primary variable of interest. The prevalence ratio data included the number of patients with SjD and the size of the study population during the study period. The secondary variables extracted were the author, publication year, country of origin, study period, the patient selection method, patient age and criteria used for the diagnosis of SjD.

2.2.4. Search Strategy, Screening and Selection

The electronic database PubMed was searched using the term ‘Sjogren’s syndrome’ in combination with ‘prevalence’ and ‘epidemiology’ for studies up to August 2024 using the following search strategy: “Sjogren’s Syndrome” [Mesh] AND (“Prevalence” [Mesh] OR “Epidemiology” [Mesh] OR “Sjogren’s Syndrome” [Mesh] epidemiology OR “Epidemiology” [Mesh] Sjogren’s Syndrome OR “Sjogren’s Syndrome” [Mesh] prevalence OR Epidemiology Sjögren’s Syndrome). Language was restricted to English.

The titles and abstracts of all identified publications were screened by two reviewers. Differences in judgement were resolved through a consensus procedure. If eligible aspects were present in the title or abstract, full-text publications were obtained, fully read and assessed. Publications which fulfilled all selection and inclusion criteria were included for data extraction. The reference lists of the included publications were also manually searched for potentially relevant publications.

2.2.5. Quality Assessment

Included studies were assessed for quality and bias using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) for case–control and cohort studies [22]. The NOS consists of 8 items, which are divided into 3 domains: selection, comparability and exposure. Assessed items in the ‘’selection’’ domain were the adequacy of the case definition, representativeness of the cases, selection of controls and the definition of controls. In the ‘’comparability’’ domain only the comparability of the cases was assessed, and in the last domain ‘exposure’, the ascertainment of exposure, the same method of case ascertainment and the non-response rate were assessed. One observer (JH) generated the scores of the included publications. When a study fulfilled an item, this was expressed with a “*”. No symbol indicated that the study was not adequate, or it was not clear whether it was adequate. In case–control and cohort studies, a maximum of 8 points could be obtained. In the adjusted version, applied in this review, only a maximum of 5 items could be assessed. In the ‘selection’ domain, the items ‘selection of controls’ and ‘definition of controls’ were not assessed and neither was ‘the ascertainment of exposure’ in the ‘exposure’ domain. These items were scored as NA = not applicable.

2.2.6. Data Extraction

Two review authors (JFH and FM) extracted data independently with the help of data extraction forms, and outcome data were summarized into Review Manager (RevMan 5.3). The details of the study such as the authors, year of publication, prevalence, prevalence ratio, incidence and incidence ratio were extracted for each study and documented in a data sheet. The overall incidence ratio and overall prevalence ratio were calculated as the weighted average of all included studies. Subsequently, the confidence interval for the calculated overall ratios was determined using the sample size calculator for designing clinical research (www.sample-size.net/confidence-interval-proportion/) (accessed on 13 August 2024).

3. Results

The ACTA electronic health record system comprised 81,941 patients who enrolled between 2010 and 2020. A total of 76 patients with SjD were identified. The prevalence of SjD at ACTA was 0.093%, and the prevalence ratio was 92.75 per 100,000 persons. At the dental school of RadboudUMC Nijmegen, the electronic health record system comprised 14,240 patients. In this database, 21 patients were labelled as SjD patients. The prevalence was 0.15%, and the prevalence ratio was 147.47 per 100,000 persons.

3.1. Literature Study

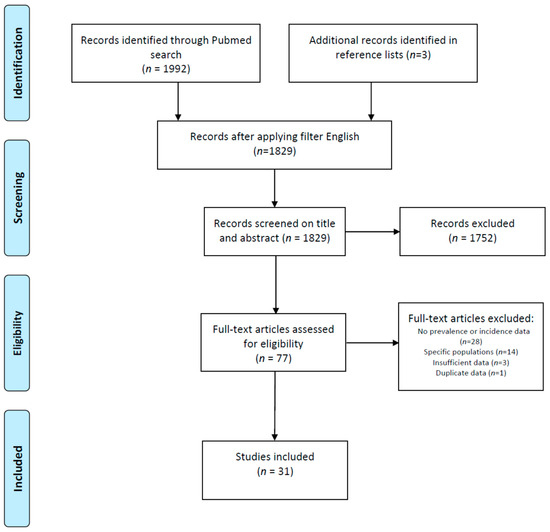

Initially, 1995 publications were found, and after restriction to publications in the English language, 1829 publications remained. All publications were screened for eligibility based on the title and abstract, after which 77 publications remained. These were screened full text for suitability. Twenty-eight studies were excluded because they did not contain data on the prevalence or incidence of SjD; in three other studies, the data were insufficient to be included, and one study contained data already presented in another publication. Fourteen studies were excluded since they only investigated specific populations. This resulted in 31 included studies. The included studies, of which 21 provided only prevalence ratios, 5 provided only incidence ratios and 5 provided both, were assessed for quality and included for data extraction (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of identification and selection of studies for inclusion.

3.2. Prevalence Ratio of SjD

Seventeen of the included prevalence studies were conducted in Europe [17,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38], five in Asia [39,40,41,42,43], one in the USA [44] and three in South America [45,46,47] (Table 1). Among the included studies were 14 medical record searches, in which the medical history of included patients was screened for SjD and diagnosis criteria, and 11 questionnaires followed by a clinical examination to determine whether patients are indeed suffering from SjD. The remaining studies used an initial telephone survey followed by the screening of medical records when necessary. All studies were published between 1995 and 2024. The American-European Consensus Group (AECG) criteria were the most widely used (12 studies) as diagnostic criteria, followed by 8 studies using ICD criteria, 4 studies using the EU criteria, 2 studies using the 2016 ACR/EULAR criteria and 1 using the San Diego criteria.

Table 1.

Overview of included Sjögren’s disease prevalence studies.

One study did not provide information on the number of assessed patients [47]. In the remaining 25 studies, the number of included subjects varied from 332 to 67 million patients with a mean of 4,213,682 patients. In three studies, only female subjects were included [27,28,40]. A total of 8 studies took a sample of patients registered in hospitals or rheumatology clinics, 5 studies took a sample of the national health insurance databases and 14 studies included patients from an entire region or country. Sixteen studies reported the prevalence of patients with primary SjD, three studies reported separate values for pSjD and SjD associated with another rheumatic disease and eight studies reported the prevalence of SjD in general.

The total population of subjects, investigated according to the AECG criteria, comprised 4,158,123 individuals with a total pooled prevalence of 0.031%. The highest prevalence in a study using the AECG diagnostic criteria was 0.72% in Turkey [40]. The lowest prevalence using the AECG was 0.01% in both France [32] and the USA [44]. The total population of individuals screened according to the EU criteria was 118,961 with a pooled prevalence of 0.029%, ranging from 0.22% in Norway [29] to 3.30% in the United Kingdom [33]. The total number of subjects in seven studies with the ICD criteria comprised 94,663,803 individuals with a pooled prevalence of 0.048%, varying from 0.038% in Italy [34] to 0.12% in Colombia 7]. The single study from China that used the San Diego criteria reported a prevalence of 0.30% [43].

3.3. Incidence Ratio of SjD

Ten studies reported the incidence ratio of SjD [23,35,41,42,44,48,49,50,51,52] (Table 2). Four studies were performed in Asia [41,42,50,52], four in Europe [23,35,49,51] and two in the USA [44,48]. Of the included studies, three used AECG and one used the EU criteria. Four studies used International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes, one study used a combination of ICD and ACR-EULAR criteria and one study did not report the diagnosis criteria used.

Table 2.

Overview of included Sjögren’s disease incidence studies.

The overall study population was 118,356,435. The overall pooled incidence rate was 5.2 (95%CI 4.7 to 5.6) per 100,000 person-years. Two studies reported a change in incidence rate over time. Seror et al. [35] reported that the incidence rate declined in the period 2012–2017, while Conrad et al. [51] reported an increase in the years 2017–2019 compared to 2000–2002.

The total population of individuals diagnosed according to the AECG criteria was 25,074,308. The reported incidence rates in the studies using the AECG criteria ranged from 3.5 (95%CI 2.9 to 4.00) per 100,000 person-years in the USA [44] to 6.0 (5.8 to 6.2) per 100,000 person-years in Taiwan [50]. The pooled incidence rate of SjD in subjects evaluated with the AECG criteria was 5.8 per 100,000 person-years (95%CI 5.4 to 6.3).

3.4. Quality Assessment

Only 6 of the 31 included studies fulfilled all 5 relevant criteria of the adjusted Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment (Table 3). Sixteen studies fulfilled four criteria, while 8 studies fulfilled three criteria and 1 study only two criteria. The most frequent missing information concerned the non-response rate, which was lacking in 19 studies, followed by missing information on the comparability of cases on the basis of the design or analysis (missing in 6 studies). The case definition and the representativeness of the cases were both inadequate in four studies. Four other studies did not use the same method of ascertain of cases.

Table 3.

Adjursted Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment.

4. Discussion

This study showed considerable variation in the reported prevalence and the incidence of SjD between countries. The observed SjD prevalence in the Netherlands falls within the range of the worldwide prevalence.

The variation in the results might be related to the different classification criteria used for the diagnosis of SjD, as the items of the criteria of the classification systems differ considerably. According to the EU criteria, patients that suffered from pre-existing lymphoma, acquired immune deficiency disease, sarcoidosis or graft-versus-host disease have to be excluded [53]. In the AECG criteria, these exclusion criteria were extended with the use of anticholinergic drugs, previous head and neck radiation treatment and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection [18]. Furthermore, according to the AECG criteria, patients should not be given anaesthesia while performing Schirmer’s test, and the definition of ‘histopathology’ was slightly stricter than in the EU criteria [18]. Despite the more strict AECG criteria, the total pooled prevalence of SjD in populations investigated with the ACEG criteria was comparable to the pooled prevalence according to the EU criteria (0.031% and 0.029%, respectively). This suggests that more stringent diagnostic criteria do not lead to a lower estimated prevalence in the population.

Three studies [27,28,40] included only female patients. Because SjD mainly affects women (female–male ratio: 9:1) [1], one limitation of a population study on female individuals only is that it will result in the overestimation of the prevalence of SjD in the general population. Moreover, the included studies showed considerable variation in the mean age of the investigated populations, which also could have affected the prevalence of SjD [30]. The peak incidence of SjD is at approximately 50 years of age [6,54], and the median delay between the appearance of the initial symptoms of SjD and the diagnosis is 8.5 years [55]. This will result in a higher prevalence of SjD in studies where the average age of the population is higher than in studies of a younger population. Conversely, studies of younger individuals may lead to the underestimation of the prevalence of SjD.

In addition, the dropout of patients in some studies could also have affected the reported prevalence and incidence ratios. Anagnostopoulos et al., Thomas et al. and Tomšič et al. reported a response rate of 37 to 48% on their questionnaires [24,26,33]. In contrast, Birlik et al. and Haugen et al. reported much higher response rates of 70% and 98%, respectively [30,39]. The exclusion of the dropouts from the results of the study might introduce the possibility of a response bias, as shown in the study by Bowman et al. [27]. Some investigators tried to correct for the non-response, using assumptions from other similar surveys. Thomas et al. [33] assumed that non-responders are likely to be closer to ‘reluctant’ responders, similar to in a study on low back pain [56]. Haugen et al. and Valim et al., who performed a study based on an initial questionnaire followed by a clinical examination, were confronted with another problem [30,46]. Some of the patients refused an appointment for a physical examination by a physician, which was necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Narvaez and co-workers, who used an initial screening by telephone, were confronted during two phases of their studies with people who did not want to cooperate. Firstly, there were many people who did not want to participate in the initial telephone screening. In addition, several people who had indicated a diagnosis of SjD or Sicca during the telephone interview refused to have that confirmed by a rheumatologist. The fact that in a proportion of SjD patients the diagnosis could not be confirmed affects the reliability of the prevalence reported in these studies.

A limitation of the systematic literature study is that only the Pubmed scientific database was searched, and the search was limited to publications in the English language. This may explain why the majority of the included studies originated from Europe and the USA. As ethnic and geographical differences have been reported [7,17], the under-representation of other continents may have affected the estimation of the total pooled prevalence and incidence.

In our study, to determine the prevalence of SjD in the Netherlands, it can be questioned to what extent patients of academic dental clinic centres are representative of the entire Dutch population. Considering that SjD patients more often suffer from oral health problems [57], it is possible that these patients are more frequently referred to an academic dental clinic, resulting in the over-representation of SjD patients in our study population. Furthermore, SjD patients in the Netherlands are less employed than the general Dutch population, and almost half of all SjD patients in the Netherlands receive disability benefits [58]. The cost of treatment at university dental clinics is lower than that of treatment in a regular dental practice in the Netherlands. As a result, we cannot exclude the possibility that, due to a lower socioeconomic status, SjD patients are more likely to be registered in university dental clinics. Also, the available electronic records lacked further information regarding the diagnosis of SjD. It is therefore possible that some patients have reported to suffer from SjD, without this diagnosis being confirmed by a rheumatologist. Altogether, this means that using data from dental university clinics may have resulted in a certain overestimation of the prevalence of SjD in the Netherlands.

5. Conclusions

Despite several potential limitations, this review of the relevant scientific literature provided an insight into the worldwide prevalence of SjD. Although the reported prevalence in the individual studies shows a wide variation from 0.008% to 3.30%, the pooled worldwide prevalence of SjD seems to be in the range of 0.03% to 0.05%, depending on the classification system used. The estimate prevalence in the Netherlands differed slightly from the pooled worldwide prevalence at 0.09% to 0.15%, which might be related to the population surveyed. Despite this relatively low prevalence in the general population, it is essential that healthcare providers screen patients for the possible presence of SjD so that patients can receive optimal (oral) healthcare for complications resulting from SjD at an early stage of the disease.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.H.J.J. and H.S.B.; methodology, F.M. and J.F.H.; formal analysis, J.F.H. and H.S.B.; investigation, J.F.H.; data curation, H.S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M. and J.F.H.; writing—review and editing, H.S.B.; supervision, D.H.J.J. and H.S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved on 21 November 2019 by the Internal Ethical Review Board of the Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA) under protocol number 201967.

Data Availability Statement

The data from the patient survey in the Netherlands are not available due to privacy reasons. The articles on which the systematic review is based are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fox, R.I. Sjögren’s syndrome. Lancet 2005, 366, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reksten, T.R.; Jonsson, M.V. Sjögren’s Syndrome: An update on epidemiology and current insights on pathophysiology. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malladi, A.S.; Sack, K.E.; Shiboski, S.C.; Shiboski, C.H.; Baer, A.N.; Banushree, R.; Dong, Y.; Helin, P.; Kirkham, B.W.; Li, M.; et al. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome as a systemic disease: A study of participants enrolled in an international Sjögren’s syndrome registry. Arthritis Care Res. 2012, 64, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bongi, S.M.; Del Rosso, A.; Orlandi, M.; Matucci-Cerinic, M. Gynaecological symptoms and sexual disability in omen with primary sjögren’s syndrome and sicca syndrome. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2013, 31, 683–690. [Google Scholar]

- Van Nimwegen, J.F.; Arends, S.; Van Zuiden, G.S.; Vissink, A.; Kroese, F.G.M.; Bootsma, H. The impact of primary Sjögren’s syndrome on female sexual function. Rheumatology 2015, 54, 1286–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariette, X.; Criswell, L.A. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuboi, H.; Asashima, H.; Takai, C.; Hagiwara, S.; Hagiya, C.; Yokosawa, M.; Hirota, T.; Umehara, H.; Kawakami, A.; Nakamura, H.; et al. Primary and secondary surveys on epidemiology of Sjögren’s syndrome in Japan. Mod. Rheumatol. 2014, 24, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, C.; Ferro, F.; Bombardieri, S. Classification criteria in Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, S.A.; Kurien, B.T.; Scofield, R.H. Oral Manifestations of Sjögren’s Syndrome. J. Dent. Res. 2008, 87, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijpe, J.; Kalk, W.W.I.; Bootsma, H.; Spijkervet, F.K.L.; Kallenberg, C.G.M.; Vissink, A. Progression of salivary gland dysfunction in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2007, 66, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weifenbach, J.M.; Schwartz, L.K.; Atkinson, J.C.; Fox, P.C. Taste performance in Sjogren’s syndrome. Physiol. Behav. 1995, 57, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, J.L.; Tanner, K.; Merrill, R.M.; Miller, K.L.; Kendall, K.A.; Roy, N. Swallowing Disorders in Sjögren’s Syndrome: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Effects on Quality of Life. Dysphagia 2016, 31, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Hamad, A.; Lodi, G.; Porter, S.; Fedele, S.; Mercandante, V. Interventions for dry mouth and hyposalivation in Sjögren’s syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis 2019, 25, 1027–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assy, Z.; Bikker, F.J.; Picauly, O.; Brand, H.S. The association between oral dryness and use of dry-mouth interventions in Sjögren’s syndrome patients. Clin. Oral Investig 2022, 26, 1465–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagozoglu, K.H.; Mahraoui, A.; Bot, J.C.J.; Cha, S.; Ho, J.-P.T.F.; Helder, M.H.; Brand, H.S.; Bartelink, I.H.; Vissink, A.; Weisman, G.A.; et al. Intraoperative Visualization and Treatment of Salivary Gland Dysfunction in Sjögren’s Syndrome Patients Using Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound Silaoendoscopy (CEUSS). J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assy, Z.; Brand, H.S. A systematic review of the effects of acupuncture on xerostomia and hyposalivation. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gøransson, L.; Haldorsen, K.; Brun, J.; Harboe, E.; Jonsson, M.; Skarstein, K.; Time, K.; Omdal, R. The point prevalence of clinically relevant primary Sjögren’s syndrome in two Norwegian counties. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2011, 40, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitali, C.; Bombardieri, S.; Jonsson, R.; Moutsopoulos, H.M.; Alexander, E.L.; Carsons, S.E.; Daniels, T.E.; Fox, P.C.; Fox, R.I.; Kassan, S.S.; et al. Classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome: A revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2002, 61, 554–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiboski, C.H.; Shiboski, S.C.; Seror, R.; Criswell, L.A.; Labetoulle, M.; Lietman, T.M.; Rasmussen, A.; Scofield, H.; Vitali, C.; Bowman, S.J.; et al. 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria for primary Sjögren’s syndrome: A consensus and data-driven methodology involving three international patient cohorts. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, C.; Talarico, R.; Tzioufas, A.G.; Bombardieri, S. Classification criteria for Sjogren’s syndrome: A critical review. J. Autoimmun. 2012, 39, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Kempen, E.E.J.; de Visscher, J.G.A.M.; Brand, H.S. Are periodontitis, dental caries and xerostomiamore frequently present in recreational ecstasy users? Br. Dent. J. 2022, 232, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alamanos, Y.; Tsifetaki, N.; Voulgari, P.V.; Venetsanopoulou, A.I.; Siozos, C.; Drosos, A.A. Epidemiology of primary Sjögren’s syndrome in north-west Greece, 1982–2003. Rheumatology 2006, 45, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomšič, M.; Logar, D.; Grmek, M.; Perkovič, T.; Kveder, T. Prevalence of Sjogren’s syndrome in Slovenia. Rheumatology 1999, 38, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Trontzas, P.I.; Andrianzakos, A. Sjogren’s syndrome: A population based study of prevalence in Greece. The ESORDIG study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2005, 64, 1240–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, I.; Zinzaras, E.; Alexiou, I.; Papathanasiou, A.A.; Davas, E.; Koutroumpas, A.; Barouta, G.; Sakkas, L.I. The prevalence of rheumatic diseases in central Greece: A population survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010, 11, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, S.J.; Ibrahim, G.H.; Holmes, G.; Hamburger, J.; Ainsworth, J.R. Estimating the prevalence among Caucasian women of primary Sjögren’s syndrome in two general practices in Birmingham, UK. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2004, 33, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafni, U.G.; Tzioufas, A.G.; Staikos, P.; Skopouli, F.N.; Moutsopoulos, H.M. Prevalence of Sjogren’s syndrome in a closed rural community. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1997, 56, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, W.W.; Rose, N.R.; Kalaydjian, A.; Pedersen, M.G.; Mortensen, P.B. Epidemiology of autoimmune diseases in Denmark. J. Autoimmun. 2007, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, A.J.; Peen, E.; Hultén, B.; Johannessen, A.C.; Brun, J.G.; Halse, A.K.; Haga, H. Estimation of the prevalence of primary Sjögren’s syndrome in two age-different community-based populations using two sets of classification criteria: The Hordaland Health Study. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2008, 37, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldini, C.; Seror, R.; Fain, O.; Dhote, R.; Amoura, Z.; De Bandt, M.; Delassus, J.; Falgarone, G.; Guillevin, L.; Le Guern, V.; et al. Epidemiology of primary Sjögren’s syndrome in a french multiracial/multiethnic area. Arthritis Care Res. 2014, 66, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardu, C.; Cocco, E.; Mereu, A.; Massa, R.; Cuccu, A.; Marrosu, M.G.; Contu, P. Population based study of 12 autoimmune diseases in Sardinia, Italy: Prevalence and comorbidity. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.; Hay, E.M.; Hajeer, A.; Silman, A.J. Sjogren’s syndrome: A community-based study of prevalence and impact. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1998, 37, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cafaro, G.; Perricone, C.; Ronconi, G.; Calabria, S.; Dondi, L.; Dondi, L.; Pedrini, A.; Esposito, I.; Gerli, R.; Bartoloni, E.; et al. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome in Italy: Real-world evidence of a rare disease through administrative healthcare data. Eur. J. Inten. Med. 2024, 124, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seror, R.; Chiche, L.; Beydon, M.; Desjeux, G.; Zhuo, J.; Vannier-Moreau, V.; Devauchelle-Pensec, V. Estimated prevalence, incidence and healthcare costs of Sjögren’s syndrome in France: A national claims-based study. RMD Open 2024, 10, e003591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stankeviciene, I.; Puriene, A.; Mieliauskaite, D.; Stangvaltaite-Mouhat, L.; Aleksejuniene, J. Detection of xerostomia, sicca and Sjogrens’ syndromes in a national sample of adults. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narvaez, J.; Sanchez-Fernandez, S.A.; Seoane-Mato, D.; Diaz-Gonzalez, F.; Bustabad, S. Prevalence of Sjögren’s synrome in the general adult population in Spain: Estimating the proportion of undiagnosed cases. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio-Cortes, J.; López-Rodríguez, J.A.; Gómez-Gascón, T.; Rayo-Gómez, Á.; del Cura-González, I.; Domínguez-Berjón, F.; Esteban-Vasallo, D.; Chalco-Orrego, J.P.; Vicente-Rabaneda, E.; Baldini, C.; et al. Prevalence and comorbidities of Sjogren’s syndrome patients in the Community of Madrid: A population-based cross-sectional study. Jt. Bone Spine 2023, 90, 105544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birlik, M.; Akar, S.; Gurler, O.; Sari, I.; Birlik, B.; Sarioglu, S.; Oktem, M.A.; Saglam, F.; Can, G.; Kayahan, H.; et al. Prevalence of primary Sjogren’s syndrome in Turkey: A population-based epidemiological study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2009, 63, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabasakal, Y.; Kitapcioglu, G.; Turk, T.; Öder, G.; Durusoy, R.; Mete, N.; Egrilmez, S.; Akalin, T. The prevalence of Sjögren’s syndrome in adult women. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2006, 35, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.H.; See, L.C.; Kuo, C.F.; Chou, I.J.; Chou, M.J. Prevalence and incidence in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases: A nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. Arthritis Care Res. 2013, 65, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- See, L.C.; Kuo, C.F.; Chou, I.J.; Chiou, M.J.; Yu, K.H. Sex- and age-specific incidence of autoimmune rheumatic diseases in the Chinese population: A Taiwan population-based study. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 43, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Shi, C.S.; Yao, Q.P.; Pan, G.X.; Wang, L.L.; Wen, Z.X.; Li, X.C.; Dong, Y. Prevalence of primary Sjogren’s syndrome in China. J. Rheumatol. 1995, 22, 659–661. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Izmirly, P.M.; Buyon, J.P.; Wan, I.; Belmont, H.M.; Sahl, S.; Salmon, J.E.; Askanase, A.; Bathon, J.M.; Geraldino-Pardilla, L.; Ali, Y.; et al. The Incidence and Prevalence of Adult Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome in New York County. Arthritis Care Res. 2019, 71, 949–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Quispe, L.A.; Velarde-Grados, I.V.N.; Guzmán-Avalos, M.; De Arriba, L.; María López-Pintor, R. Prevalence of sicca syndrome in the Peruvian population. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2019, 118, 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Valim, V.; Zandonade, E.; Pereira, A.M.; de Brito Filho, O.H.; Serrano, E.V.; Musso, C.; Giovelli, R.A.; Ciconelli, R.M. Primary sjögren’s syndrome prevalence in a major metropolitan area in Brazil. Rev. Bras. Reumatol. 2013, 53, 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ávila, D.G.; Rincón-Riano, D.N.; Bernal-Macías, S.; Gutiérrez Dávila, J.M.; Rosselli, D. Prevalence and demograohic characteristics of Sjögren’s syndrome in Colombia, based on information from the Official Ministry of Health Registry. Reumatol. Clin. 2020, 16, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillemer, S.R.; Matteson, E.L.; Jacobsson, L.T.H.; Martens, P.B.; Melton, L.J.; O’Fallon, W.M.; Fox, P.C. Incidence of physician-diagnosed primary Sjögren syndrome in residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2001, 76, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plešivčnik Novljan, M.; Rozman, B.; Hočevar, A.; Grmek, M.; Kveder, T.; Tomšič, M. Incidence of primary Sjögren’s syndrome in Slovenia. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2004, 63, 874–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, M.Y.; Huang, Y.T.; Liu, M.F.; Lu, T.H. Incidence and mortality of treated primary sjögren’s syndrome in Taiwan: A population-based study. J. Rheumatol. 2011, 38, 706–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, N.; Misra, S.; Verbakel, J.Y.; Verbeke, G.; Molenberghs, G.; Taylor, P.N.; Mason, J.; Sattar, N.; McMurray, J.J.; McInnes, I.B.; et al. Incidence, prevalence, and co-occurrence of autoimmune disorders over time and by age, sex, and socioeconomic status: A population-based cohort study of 22 million individuals in the UK. Lancet 2023, 401, 1878–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.H.; Ma, K.S.K.; Dong, C.; Chang, W.J.; Gao, K.R.; Perng, W.T.; Huang, J.Y.; Wei, J.C.C. Risk of primary Sjogren’s syndrome following human papillomavirus infections: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 967040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitali, C.; Bombardieri, S.; Moutsopoulos, H.M.; Balestrieri, G.; Bencivelli, W.; Bernstein, R.M.; Bjerrum, K.B.; Braga, S.; Coll, J.; Vita, S.D.; et al. Preliminary criteria for the classification of Sjögren’s syndrome. Results of a prospective concerted action supported by the European community. Arthritis Rheum. 1993, 36, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beydon, M.; McCoy, S.; Nguyen, Y.; Sumida, T.; Mariette, X.; Seror, R. Epidemiology of Sjögren syndrome. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2024, 20, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuryata, O.; Lysunets, T.; Karavanska, I.; Semenov, V. Duration till diagnosis and clinical profile of Sjögren’s syndrome: Data from real c;inical practice in a single-center cohort. Egypt. Rheumatol. 2022, 42, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, A.C.; Croft, P.R.; Ferry, S.; Jayson, M.I.V.; Silman, A.J. Estimating the prevalence of low back pain in the general population: Evidence from the south Manchester back pain survey. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995, 20, 1889–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.B.; Petersen, P.E.; Thorn, J.J.; Schiødt, M. Dental caries and dental health behavior of patients with primary Sjögren syndrome. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2001, 59, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, J.M.; Meiners, P.M.; Huddleston Slater, J.J.; Spijkervet, F.K.; Kallenberg, C.G.; Vissink, A.; Bootsma, H. Health-related quality of life, employment and disability in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Rheumatology 2009, 48, 1077–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).