Abstract

Background: Valve-in-Valve (VIV) transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is a potential solution for malfunctioning surgical aortic valve prostheses, though limited data exist for its use in Perceval valves. Methods: searches were performed on PubMed and Scopus up to 31 July 2023, focusing on case reports and series addressing VIV replacement for degenerated Perceval bioprostheses. Results: Our analysis included 57 patients from 27 case reports and 6 case series. Most patients (68.4%) were women, with a mean age of 76 ± 4.4 years and a mean STS score of 6.1 ± 4.3%. Follow-up averaged 9.8 ± 8.9 months, the mean gradient reduction was 15 ± 5.9 mmHg at discharge and 13 ± 4.2 mmHg at follow-up. Complications occurred in 15.7% of patients, including atrioventricular block III in four patients (7%), major bleeding or vascular complications in two patients (3.5%), an annular rupture in two patients (3.5%), and mortality in two patients (3.5%). No coronary obstruction was reported. Balloon-expanding valves were used in 61.4% of patients, predominantly the Sapien model. In the self-expanding group (38.6%), no valve migration occurred, with a permanent pacemaker implantation rate of 9%, compared to 5.7% for balloon-expanding valves. Conclusions: VIV-TAVR using both balloon-expanding and self-expanding technologies is feasible after the implantation of Perceval valves; however, it should be performed by experienced operators with experience both in TAVR and VIV procedures.

1. Background

Surgical aortic valve replacement (AVR) is the recommended treatment option for patients with aortic valve disease [1,2]. The operational risk for AVR has reduced significantly, with a drop in mortality from 4.3% to 2.6% [3,4]. Even with these results, elderly high-risk patients who are referred for AVR still have poor outcomes; hence, sutureless technology may assist in reducing morbidity and mortality [5,6,7,8].

A whole new approach to surgically implanting aortic valve bioprostheses has been described in the last ten years with the advent of sutureless aortic valve replacement (SAVR). The Perceval valve (LivaNova, PLC, London, UK) is a well-known sutureless bioprosthesis that has been demonstrated to cut the cross-clamp time in half [7,9]. The Perceval valve differs from traditional surgical sutured bioprostheses in that it features a tall nitinol stent composed of two rings joined by nine struts. Regarding sutured bioprostheses, sutureless bioprostheses are susceptible to structural valve degeneration; reports of stent infolding, maybe as a result of improper prosthetic sizing technique, have also been made [7]. Initially, older patients were the primary target market for SAVR operations, as they stand to gain the most from shorter recovery times. Patients in this higher risk category, however, will be at much greater danger should the prior sutureless bioprosthesis degenerate and require surgery. Given the encouraging outcomes of recent series, a percutaneous technique using Valve-in-Valve (VIV) surgery could be taken into consideration as a viable alternative in this case [10]. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is a viable method for the VIV replacement of surgical valves that have deteriorated. Nonetheless, there is still little experience with VIV-TAVR for deteriorated Perceval valves [11,12,13]. Since, there are only published cases in the literature explaining the outcomes of TAVR through VIV procedure, we aimed to gather evidence from all available cases to generate a more comprehensive view of this procedure.

2. Methods

This study was carried out in compliance with the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions at each step [14]. Following the PRISMA statement’s guidelines, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis [15].

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

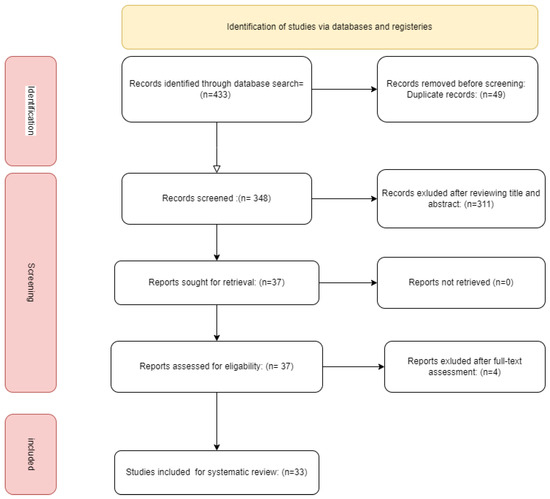

The searching process was conducted on PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science from inception to 30 June 2024Since they better illustrate the purpose of our study, the following keywords were included in the search strategy: “Perceval” OR “sutureless valve” AND “Aortic valve replacement” OR “AVR” AND “Valve in Valve” (Figure 1).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

All papers were examined separately by four authors during the selection and critical appraisal phases. Case reports and case series investigating the use of VIV replacement for degenerated Perceval bioprostheses were included in our systematic review. Narrative reviews, scoping reviews, systematic reviews, conference abstracts, randomized controlled trials, descriptive cross-sectional studies, case-control studies, and cohort studies were all excluded because they did not address the key goals. Rayyan [16] was used to screen the articles based on their titles and abstracts. Each prospective article’s whole text was reviewed individually by four authors after title and abstract screening. Any disagreements that developed throughout the research selection process were resolved by consensus and if the disagreements persisted, the senior author resolved them.

2.3. Data Extraction

Four authors worked separately to extract data using a standard data extraction sheet created in Microsoft Excel and individually updated by the senior author. The following data were extracted: Age, sex, STS Scor%, Perceval size, cause, reason for VIV, degeneration, type of TAVI, duration of follow-up, mean gradient at discharge, and, on follow-up, complications, coronary obstruction, and outcomes.

Figure 1.

flow chart of the study.

2.4. Quality Assessment

The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools for Case Reports were used to evaluate the quality of the included studies [17]. The questions were answered with “Yes” or “No”. Each “yes” response is worth one point, and the possible scores range from 0 to 8. Studies with a score of 7–8 are of good quality, those with a score of 4–6 are of a moderate level, and those with a score of 0–3 are of low quality. Only publications with a score more than four were included in this study.

3. Results

3.1. Database Searching and Screening

According to our abovementioned search and quality assessment criteria, we included 48 patients in this metanalysis from 27 case reports and 5 case series [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41].

3.2. Baseline Characteristics

The majority (68.4) were women and the mean ± SD of age was 76 ± 4.4 years. The STS score % of the included patients had a mean ± SD of 6.1 ± 4.3% and the months after Perceval implant were 9.8 ± 8.9 months. The mean TAVI size was 24.7 ± 1.9 mm, while the Perceval size was small in 31.5% of the patients, medium in 40.3%, large in 22.8%, and x-large in 5.2%. The most common reason for VIV was steno-insufficiency in 45.6% of patients, followed by stenosis and regurgitation in 31.5% and 22.8% of patients, respectively. The most common mechanism was degeneration (36 patients; 63.1%), followed by stent folding (13 patients; 22.8%); otherwise, migration in three patients, thrombosis in two patients, and endocarditis in one patient. The majority (61.4%) of implanted TAVI was balloon expanding and the most common model (57.8%) was Sapien. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics of the included patients.

In the patients treated with self-expanding valves (20 patients; 41.6%), including 17 patients with CoreValve or Evolut, 1 patient with Acurate neo, 1 patient with Portico, and 1 patient with Allegra, no valve migration was reported, and the rate of permanent pacemaker (PPM) implantation was 10%, compared to 7.1% in patients treated with balloon-expanding technology.

3.3. Clinical Outcomes

The mean follow-up period was 9.8 ± 8.9 months; the mean gradient reduction was 15 ± 5.9 mmHg at discharge and 13 ± 4.2 mmHg at follow-up. The follow-up data were available in 19 patients; all those patients were asymptomatic or had improved symptoms at the follow-up. Complications were reported in nine patients (15.7%). Among these, four patients (7%) developed atrioventricular (AV) block III, with one patient experiencing late AV block III on the 8th postoperative day. Major bleeding or vascular complications were reported in two patients (3.5%), an annular rupture in two patients (3.5%), and mortality in two patients (3.5%). The majority of patients (84.3%) showed no complications. The cause of mortality was an annular rupture in one patient, while the second patient underwent an emergency ViV TAVR to treat severe aortic regurgitation (AR) and cardiogenic shock due to Perceval migration. This patient died 10 days after the procedure due to complications derived from the mechanical support implanted the day after the procedure. Moreover, none of the patients showed coronary obstruction. (Table 2) Balloon-expanding valves were used in 61.4% of patients, predominantly the Sapien model. In the self-expanding group (38.6%), no valve migration occurred, with a permanent pacemaker implantation rate of 9%, compared to 5.7% for balloon-expanding valves.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of the included patients.

Two cases suffered from annular ruptures; the first had post-procedural imaging which demonstrated bioprosthetic valve frame protrusion and contained an annular rupture, which required operative intervention. The second had an aortic annular rupture inferior to the origin of the left coronary artery with the extravasation of contrast and a large hematoma compressing the right ventricular outflow tract. Upon a review of previous imaging, the rupture site appeared to correspond to the location of the previously infolded portion of the Perceval valve. The patient passed away on the second postoperative day (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3.

Procedural characteristics of the included patients.

Table 4.

Outcomes of Valve in Valve procedure in the included patients.

4. Discussion

Our study aimed to evaluate the outcomes of VIV-TAVR in patients with Perceval implants. We observed that VIV-TAVR, utilizing both balloon-expanding and self-expanding TAVR technologies, demonstrated safety and efficacy, yielding excellent short- and mid-term outcomes and favorable hemodynamics.

Both surgical and transcatheter bioprosthetic valves have a limited lifetime. It is often challenging to identify patients with failed bioprosthetic valves as historical definitions are based on death or valvular reinterventions, meaning that all cases are not accurately captured. Thus, the accurate capture of all valve failure cases should be based on imaging. The main modality for diagnosis is echocardiography and, to a lesser extent, computerized tomography which can add valuable information regarding the mechanism. The echocardiographic definition of structural valve degeneration includes an increase in the mean transvalvular gradient ≥10 mm Hg resulting in a mean gradient ≥20 mm Hg with concomitant decreases in the aortic valve which are (AVA) ≥0.3 cm−2 or ≥25% and/or decreases in the dimensionless velocity index (DVI) ≥0.1 or ≥20% compared with the echocardiographic assessment performed 1-to-3 months postprocedure or at discharge if not available or new occurrence or an increase of >1 grade of intraprosthetic aortic regurgitation (AR) resulting in moderate AR [47]. The mechanisms of bioprosthetic valve dysfunction include structural bioprosthetic valve failure, i.e., intrinsic irreversible damage to the valve structure; non-structural valve failure, i.e., not intrinsic to the valve; valve thrombosis; and endocarditis [47]. Examples of non-structural valve degeneration include a patient–prosthesis mismatch and paravalvular regurgitation.

Current ESC guidelines recommend operative Re-SAVR for patients with degenerated bioprosthetic valves as a class I-C recommendation. However, many patients with degenerated valves have operative risk, thus the guidelines recommend TAVR as the treatment of choice after a multidisciplinary heart-team discussion and risk assessment using standardized scores like STS or EuroScores [48].

The “PERCEVAL TRIAL” pilot study was performed in 30 high-risk patients who were scheduled for isolated SAVR due to severe aortic stenosis, the Perceval met non-inferiority criteria vs. stented AV-prosthesis, but had a significantly reduced surgical times mean (CPB: 71.0 ± 34.1 vs. 87.8 ± 33.9 min; mean aortic cross-clamp times: 48.5 ± 24.7 vs. 65.2 ± 23.6; both p-values < 0.001), but resulted in a higher rate of permanent pacemaker implantation (PPI—11.1 vs. 3.6% at 1 year). Incidences of paravalvular leakage (PVL) and central leak were similar [49]. Another study reported excellent outcomes with Perceval with a total of 1652 patients who showed excellent short-term and long-term outcomes [8]. A recent study by Concistrè et al. [50] showed that VIV-TAVR seems to be a safe and efficient solution for deteriorated Perceval. This process is linked to a superior hemodynamic function and positive clinical outcomes.

The majority of patients in our study were elderly patients and had a high surgical risk with a mean STS-Score ± SD of 6.1 ± 4.3%; thus a transcatheter treatment was recommended over reoperation, denoting a high degree of guidelines-based treatment in the study cohort.

The most commonly degenerated valves were small and medium valves, and the most common mode of failure was mixed stenosis and regurgitation. Valve degeneration is often multifactorial and cannot be attributed to a single factor. In a recent study including a total of 25,490 patients, risk factors included an increasing body surface area, a patient–prosthesis mismatch, and smoking, whereas age was a protective factor [51]. In our study, mixed stenosis and regurgitation was the most prevalent type of degeneration. The degeneration of bioprothesis is a complex multifactorial process; however, some points should be specifically avoided when implanting Perceval. Many surgeons favor some degree of oversizing in conventional SAVR, thus achieving superior hemodynamics and avoiding a patient–prosthesis mismatch. However, this should not be carried out in cases of sutureless rapid-deployment Perceval because it leads to the incomplete expansion and or deformation of the stent struts, causing regurgitation or stenosis. This was proven by Cerillo et al. [52], who found that the degree of oversizing is the strongest predictor of high postoperative peak and mean gradients. Thus, it is felt that the incorrect sizing of the Perceval may be the culprit in early valve degeneration.

Regarding the choice of the TAVI prosthesis, we found that both the balloon-expanding and self-expanding prosthesis were successfully deployed with no difference in the outcome noted. We found that the peak and mean gradients met the VARC-3 definition for device success without increased gradients in 100% of the patients.

In our series, no cases of coronary artery obstruction occurred. This highlights the importance of preoperative planning. Commonly used measures include the virtual transcatheter heart valve (THV) to the coronary ostial distance (VTC), which can be simulated prior to implantation. Thus, a VTC of less than 3 mm is considered a high risk for coronary obstruction, and 6 mm is considered a low risk [53]. Our hypothesis is that the configuration of PERCEVAL has a crucial role in preventing iatrogenic coronary obstruction. This valve has a flask-shaped suprannular frame, which prevents the displacement of the degenerated leaflet towards the sinus of Valsalva, providing adequate space between the coronary ostia and the degenerated bioprosthesis. This allows for adequate coronary perfusion by preserving the VTC. Concerning the pacemaker after the valve-in–valve-out analysis shows an incidence of 0.0% in comparison with TAVR in sutured bioprosthetics. This could be explained by the relative flexibility of the PERCEVAL frame compared to the stiff sewing ring on the sutured counterpart. This flexibility may allow the overexpansion in PERCEVAL and hence injury to the conduction system with a higher incidence of conduction disturbance and permanent pacemakers. One useful technique is to assess the depth of the in situ Perceval and its relationship to the membranous septum, thus avoiding this potential caveat. This also could have implications for the choice of TAVR valve, depth of implantation, and overexpansion and may be avoidable in the hands of experienced teams.

Regarding the hemodynamic performance of the implanted TAVI prosthesis, it is well known that the ViV-TAVI prosthesis implanted in the surgical valve has a poorer hemodynamic profile with elevated mean gradients and a lower-than-expected orifice area when compared to Redo-SAVR [54]. This may be an important issue regarding the lifetime management of younger patients undergoing ViV-TAVR after SAVR. In our study, most of the patients achieved a low mean gradient, with the mean gradient decreasing to 11 mmHg on the 6-month follow-up. This superior hemodynamic performance after Perceval may be attributed to the overexpansion capacity of the valve without the need for valve fracture. This is attributed to the flexible Nitinol–Titanium alloy allowing successful overexpansion, thus achieving superior hemodynamics.

5. Limitations

One limitation of our meta-analysis is the relatively small number of patients included, which may affect the generalizability of our findings, in addition to the lack of long-term follow-up and the absence of follow-up echocardiographic data from 71% of the patients.

6. Conclusions

ViV-TAVR, utilizing both balloon-expanding and self-expanding TAVR technologies, demonstrated acceptable outcomes. Although it remains a relatively rare procedure, it can be performed safely in the hands of an experienced TAVR operator after the appropriate discussion of all treatment options by the heart team. Experience with the VIV procedure after sutureless valves remains limited and should be further studied to provide a consensus on the management of those patients.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AR | Aortic Regurgitation |

| AV | Atrioventricular |

| AVR | Aortic Valve Replacement |

| CPB | Cardiopulmonary Bypass |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| PPM | Permanent Pacemaker |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SAVR | Sutureless Aortic Valve Replacement |

| STS | Society of Thoracic Surgeons |

| TAVR | Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement |

| THV | Transcatheter Heart Valve |

| VARC-3 | Valve Academic Research Consortium 3 |

| VIV | Valve-in-Valve |

References

- Nishimura, R.A.; Otto, C.M.; Bonow, R.O.; Carabello, B.A.; Erwin, J.P., 3rd; Guyton, R.A.; O’Gara, P.T.; Ruiz, C.E.; Skubas, N.J.; Sorajja, P.; et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 2438–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahanian, A.; Alfieri, O.; Andreotti, F.; Antunes, M.J.; Barón-Esquivias, G.; Baumgartner, H.; Borger, M.A.; Carrel, T.P.; De Bonis, M.; Evangelista, A.; et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012): The Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2012, 42, S1–S44. [Google Scholar]

- Goodney, P.P.; O’Connor, G.T.; Wennberg, D.E.; Birkmeyer, J.D. Do hospitals with low mortality rates in coronary artery bypass also perform well in valve replacement? Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2003, 76, 1131–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.M.; O’Brien, S.M.; Wu, C.; Sikora, J.A.H.; Griffith, B.P.; Gammie, J.S. Isolated aortic valve replacement in North America comprising 108,687 patients in 10 years: Changes in risks, valve types, and outcomes in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2009, 137, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischlein, T.; Meuris, B.; Hakim-Meibodi, K.; Misfeld, M.; Carrel, T.; Zembala, M.; Gaggianesi, S.; Madonna, F.; Laborde, F.; Asch, F.; et al. The sutureless aortic valve at 1 year: A large multicenter cohort study. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016, 151, 1617–1626.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischlein, T.; Pfeiffer, S.; Pollari, F.; Sirch, J.; Vogt, F.; Santarpino, G. Sutureless Valve Implantation via Mini J-Sternotomy: A Single Center Experience with 2 Years Mean Follow-up. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015, 63, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, M.; Fischlein, T.; Meuris, B.; Flameng, W.; Carrel, T.; Madonna, F.; Misfeld, M.; Folliguet, T.; Haverich, A.; Laborde, F. European multicentre experience with the sutureless Perceval valve: Clinical and haemodynamic outcomes up to 5 years in over 700 patients. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2016, 49, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concistré, G.; Baghai, M.; Santarpino, G.; Royse, A.; Scherner, M.; Troise, G.; Glauber, M.; Solinas, M. Clinical and hemodynamic outcomes of the Perceval sutureless aortic valve from a real-world registry. Interdiscip. CardioVasc. Thorac. Surg. 2023, 36, ivad103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarpino, G.; Pfeiffer, S.; Concistré, G.; Grossmann, I.; Hinzmann, M.; Fischlein, T. The Perceval S aortic valve has the potential of shortening surgical time: Does it also result in improved outcome? Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2013, 96, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.N.; Gad, M.M.; Elgendy, I.Y.; Mahmoud, A.A.; Taha, Y.; Elgendy, A.Y.; Ahuja, K.R.; Saad, A.M.; Simonato, M.; McCabe, J.M.; et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of valve-in-valve transcatheter aortic valve replacement in patients with failed bioprosthetic aortic valves. EuroIntervention 2020, 16, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, R.T.; Linjawi, H.; Butler, C.; Mathew, A.; Muhll, I.V.; Khandekar, S.; Tyrrell, B.D.; Nagendran, J.; Taylor, D.; Welsh, R.C. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation in a Failed Perceval Sutureless Valve, Complicated by Aortic Annular Rupture. CJC Open 2022, 4, 577–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, T.; Tanseco, K.; Arunothayaraj, S.; Michail, M.; Cockburn, J.; Hadjivassilev, S.; Hildick-Smith, D. Valve-in-Valve Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation for the Failing Surgical Perceval Bioprosthesis. Cardiovasc. Revasculariz. Med. 2022, 40, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belluschi, I.; Buzzatti, N.; Blasio, A.; Romano, V.; De Bonis, M.; Castiglioni, A.; Montorfano, M.; Alfieri, O. Self-expanding valve-in-valve treatment for failing sutureless aortic bioprosthesis. J. Card. Surg. 2020, 35, 477–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayyan. Available online: https://rayyan.ai/ (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Munn, Z.; Barker, T.H.; Moola, S.; Tufanaru, C.; Stern, C.; McArthur, A.; Stephenson, M.; Aromataris, E. Methodological quality of case series studies: An introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2127–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Song, Z.; Soffer, D.; Pirris, J.P. Transcatheter aortic valve-in-valve implantation for early failure of sutureless aortic bioprosthesis. J. Card. Surg. 2018, 33, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lettieri, C.; Romano, M.; Camurri, N.; Niglio, T.; Serino, F.; Cionini, F.; Baccaglioni, N.; Buffoli, F.; Rosiello, R.; Rambaldini, M. Impianto transcatetere di valvola aortica in paziente con bioprotesi aortica sutureless degenerata: Descrizione di un caso e revisione della letteratura [Transcatheter valve-in-valve implantation in a patient with a degenerative sutureless aortic bioprosthesis: Case report and literature review]. G. Ital. Cardiol. 2017, 18 (Suppl. S1), 18S–21S. [Google Scholar]

- Mangner, N.; Holzhey, D.; Misfeld, M.; Linke, A. Treatment of a degenerated sutureless Sorin Perceval® valve using an Edwards SAPIEN 3. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2018, 26, 364–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, E.; Tron, C.; Eltchaninoff, H. Emergency Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation for Acute and Early Failure of Sutureless Perceval Aortic Valve. Can. J. Cardiol. 2015, 31, 1204.e13–1204.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Eusanio, M.; Saia, F.; Pellicciari, G.; Phan, K.; Ferlito, M.; Dall, G.; Di Bartolomeo, R.; Marzocchi, A. In the era of the valve-in-valve: Is transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in sutureless valves feasible? Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2015, 4, 214–217. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, B.; Kütting, M.; Scholtz, S.; Utzenrath, M.; Hakim-Meibodi, K.; Paluszkiewicz, L.; Schmitz, C.; Börgermann, J.; Gummert, J.; Steinseifer, U.; et al. Development of an algorithm to plan and simulate a new interventional procedure. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2015, 21, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Amabile, N.; Zannis, K.; Veugeois, A.; Caussin, C. Early outcome of degenerated self-expanding sutureless aortic prostheses treated with transcatheter valve implantation: A pilot series. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016, 152, 1635–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vondran, M.; Abt, B.; Nef, H.; Rastan, A.J. Allegra Transcatheter Heart Valve inside a Degenerated Sutureless Aortic Bioprosthesis. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. Rep. 2021, 10, e1–e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misfeld, M.; Abdel-Wahab, M.; Thiele, H.; Borger, M.A.; Holzhey, D. A series of four transcatheter aortic valve replacement in failed Perceval valves. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2020, 9, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellouze, M.; Mazine, A.; Carrier, M.; Bouchard, D. Sutureless and Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: When Rivals Become Allies. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 32, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilalta, V.; Carrillo, X.; Fernández-Nofrerías, E.; González-Lopera, M.; Mauri, J.; Bayés-Genís, A. Valve-in-valve transcatheter aortic valve implantation for bioprosthetic aortic sutureless valve failure: A case series. Rev. Española Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2021, 74, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raschpichler, M.C.; Chakravarty, T.; Lange, D.; Makkar, R.R. Balloon-expanding valve-in-valve for a deformed surgical bioprosthesis. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Portano, J.D.; Zaldívar-Fujigaki, J.L.; García-García, J.F.; Madrid-Dour, E.A.; Muratalla-González, R.; Merino-Rajme, J.A. Acute dislocation of a Perceval valve treated with TAVI valve-in-valve: A literature review and case report. CIU Card. Image Updat. 2019, 1, 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Laricchia, A.; Mangieri, A.; Colombo, A.; Giannini, F. Perceval sutureless valve migration treated by valve-in-valve with a CoreValve Evolut Pro. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 96, 225–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosmas, I.; Iakovou, I.; Leontiadis, E.; Sbarouni, E.; Georgiadou, P.; Bousoula, E.; Aravanis, N.; Stratinaki, M.; Voudris, V.; Mpalanika, M. The first transcatheter valve-in-valve implantation of a self-expanding valve for the treatment of a degenerated sutureless aortic bioprosthesis. Hell. J. Cardiol. 2020, 61, 49–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koni, E.; Trianni, G.; Ravani, M.; Gasbarri, T.; Al Jabri, A.; Chiappino, D.; Berti, S. Bailout Balloon Predilatation and Buddy Wire Technique for Crossing a Degenerated Sutureless Perceval Bioprosthesis with SAPIEN 3 Ultra Device in a Transcatheter Valve-in-Valve Intervention. Cardiovasc. Revascularization Med. 2019, 20, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balghith, M.A. Degenerated Suturless Perceval with (Paravalvular Leak and AS) Treated by Valve in Valve using S3 Edward Valve. Heart Views 2019, 20, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Lara, J.; García-Puente, J.; Mateo-Martínez, A.; Pinar-Bermúdez, E.; Gutiérrez-García, F.; Valdés-Chávarri, M. Percutaneous Treatment of Early Denegeration of a Sutureless Bioprosthesis. Rev. Española Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2018, 71, 398–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oezpeker, U.C.; Feuchtner, G.; Bonaros, N. Cusp thrombosis of a self-expanding sutureless aortic valve treated by valve-in-valve transcatheter aortic valve implantation procedure: Case report. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 2018, 2, yty117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tomai, F.; Weltert, L.; de Persio, G.; Salatino, T.; de Paulis, R. The matryoshka procedure. J. Card. Surg. 2021, 36, 3381–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Tejero, S.; Núñez-García, J.C.; Antúnez-Muiños, P.; González-Calle, D.; Martín-Moreiras, J.; Diego-Nieto, A.; Rodríguez-Collado, J.; Herrero-Garibi, J.; Sánchez-Fernández, P.L.; Cruz-González, I. TAVR to Solve Perceval Sutureless Valve Migration. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 15, e65–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, T.; Rajani, R.; Esposito, G.; Allen, C.; Adams, H.; Prendergast, B.; Young, C.; Redwood, S. Transcatheter Aortic Valve-in-Valve Implantation Complicated by Aorto-Right Ventricular Fistula. JACC Case Rep. 2020, 2, 309–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğan, M.; Kasapkara, A.; Öztürk, S.; Çöteli, C.; Baştuğ, S.; Bayram, N.A.; Akçay, M.; Durmaz, T.; Turkey, A. First experience in Turkey with Meril’s MyValTM transcatheter aortic valve-in valve replacement for degenerated PERCEVALTM bioprothesis valve. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2022, 26, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, Ş.; Bayar, N.; Erkal, Z.; Köklü, E.; Çağırcı, G. Transcatheter valve-in-valve implantation for sutureless bioprosthetic aortic paravalvular leak in the era of COVID-19. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2021, 25, 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, A.; Reyes, M.; Yang, E.; Little, S.H.; Nabi, F.; Barker, C.M.; Ramchandani, M.; Reul, R.M.; Reardon, M.J.; Kleiman, N.S. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement for Perceval Sutureless Aortic Valve Failure. J. Invasive Cardiol. 2017, 29, E65–E66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Landes, U.; Sagie, A.; Kornowski, R. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation in degenerative sutureless perceval aortic bioprosthesis. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2018, 91, 1000–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loforte, A.; Comentale, G.; Coppola, G.; Amodio, C.; Botta, L.; Saia, F.; Taglieri, N.; Marrozzini, C.; Savini, C.; Pacini, D. A rescue transcatheter solution for early sutureless basal ring infolding. J. Card. Surg. 2022, 37, 697–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medda, M.; Casilli, F.; Tespili, M.; Bande, M. The “Chaperone Technique”: Valve-in-Valve TAVR Procedure with a Self-Expandable Valve Inside a Degenerated Sutureless Prosthesis. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, e15–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubios, C.; Minten, L.; Lamberigts, M.; Lesizza, P.; Jacobs, S.; Adriaenssens, T.; Verbrugghe, P.; Meuris, B. Valve-in-valve transcatheter aortic valve replacement for the degenerated rapid deployment Perceval prosthesis: Technical considerations. J. Vis. Surg. 2023, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pibarot, P.; Herrmann, H.C.; Wu, C.; Hahn, R.T.; Otto, C.M.; Abbas, A.E.; Chambers, J.; Dweck, M.R.; Leipsic, J.A.; Simonato, M.; et al. Standardized Definitions for Bioprosthetic Valve Dysfunction Following Aortic or Mitral Valve Replacement. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease: Developed by the Task Force for the management of valvular heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J. 2022, 14, 561–632.

- Meuris, B.; Flameng, W.J.; Laborde, F.; Folliguet, T.A.; Haverich, A.; Shrestha, M. Five-year results of the pilot trial of a sutureless valve. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015, 150, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concistré, G.; Gasbarri, T.; Ravani, M.; Al Jabri, A.; Trianni, G.; Bianchi, G.; Margaryan, R.; Chiaramonti, F.; Murzi, M.; Kallushi, E.; et al. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in Degenerated Perceval Bioprosthesis: Clinical and Technical Aspects in 32 Cases. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochi, A.; Cheng, K.; Zhao, B.; Hardikar, A.A.; Negishi, K. Patient Risk Factors for Bioprosthetic Aortic Valve Degeneration: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Heart Lung Circ. 2020, 29, 668–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerillo, A.G.; Amoretti, F.; Mariani, M.; Cigala, E.; Murzi, M.; Gasbarri, T.; Solinas, M.; Chiappino, D. Increased Gradients After Aortic Valve Replacement with the Perceval Valve: The Role of Oversizing. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2018, 106, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvir, D.; Leipsic, J.; Blanke, P.; Ribeiro, H.B.; Kornowski, R.; Pichard, A.; Rodés-Cabau, J.; Wood, D.A.; Stub, D.; Ben-Dor, I.; et al. Coronary Obstruction in Transcatheter Aortic Valve-in-Valve Implantation. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015, 8, e002079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hecht, S.; Zenses, A.-S.; Bernard, J.; Tastet, L.; Côté, N.; Guimarães, L.d.F.C.; Paradis, J.-M.; Beaudoin, J.; O’connor, K.; Bernier, M.; et al. Hemodynamic and Clinical Outcomes in Redo-Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement vs. Transcatheter Valve-in-Valve. Struct. Heart 2022, 6, 100106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).