Abstract

Comparative efficacy and safety of renal denervation (RDN) interventions for uncontrolled (UH) and resistant hypertension (RH) is unknown. We assessed the comparative efficacy and safety of existing RDN interventions for UH and RH. Six search engines were searched up to 1 May 2020. Primary outcomes were mean 24-h ambulatory and office systolic blood pressure (SBP). Secondary outcomes were mean 24-h ambulatory and office diastolic blood pressure (DBP), clinical outcomes, and serious adverse events. Frequentist random-effects network meta-analyses were used to evaluate effects of RDN interventions. Twenty randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (n = 2152) were included, 15 in RH (n = 1544) and five in UH (n = 608). Intervention arms included radiofrequency (RF) in main renal artery (MRA) (n = 10), RF in MRA and branches (n = 4), RF in MRA+ antihypertensive therapy (AHT) (n = 5), ultrasound (US) in MRA (n = 3), sham (n = 8), and AHT (n = 9). RF in MRA and branches ranked as the best treatment to reduce 24-h ambulatory, daytime, and nighttime SBP and DBP versus other interventions (p-scores: 0.83 to 0.97); significant blood pressure effects were found versus sham or AHT. RF in MRA+AHT was the best treatment to reduce office SBP and DBP (p-scores: 0.84 and 0.90, respectively). RF in MRA and branches was the most efficacious versus other interventions to reduce 24-h ambulatory SBP and DBP in UH or RH.

1. Introduction

Renal denervation (RDN) is an option for treating resistant hypertension (RH) [1] and uncontrolled hypertension (UH) [2]. Early studies such as the Symplicity HTN-1 single-arm trial and the Symplicity HTN-2 randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed promising results of RDN on lowering blood pressure (BP); however, the Symplicity HTN-3 sham-controlled trial in 2014 showed neutral results. Reasons for negative findings include patients’ failure to adhere to antihypertensive medication as well as the inexperience of those performing the renal ablation. More recent RCTs improved the Symplicity HTN-3 trial’s shortcomings; the DENERHTN trial, the SPYRAL HTN-OFF trial, the SPYRAL HTN-ON trial, and the RADIANCE-HTN SOLO trial showed clinically significant decreases in ambulatory BP [3,4].

Several systematic reviews (SR) have evaluated the efficacy of RDN in RH and/or UH [5,6,7,8,9]. Cheng et al. found that UH patients experienced a reduction in mean 24-h systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 4 mmHg (95% confidence interval (CI) −5.5 to −2.6) after RDN when compared to controls [5]. Another recent SR of sham-controlled RCTs by Dahal et al. identified that RDN reduced both ambulatory SBP (−3.5 mmHg, 95% CI −5.0 to −1.9) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) (−1.9 mmHg, 95% CI −3.6 to −0.2) in both RH and UH patients [6]. Coppolino et al. in 2017 assessed RH patients and found that RDN did not reduce ambulatory and office BP, or clinical outcomes, in comparison to standard therapy or sham [7]. Yao et al., in 2016, found a significant reduction of DBP in comparison to standard medical therapy in RH patients (−3.8 mmHg, 95% CI −7.2 to −0.3) [8]. Finally, Fadl Elmula et al., in 2015, did not find differences in ambulatory or office BPs between RDN + antihypertensives and antihypertensives alone in RH patients [9].

None of the previous systematic reviews compared all available RDN options to one another, in particular specific types of radiofrequency (e.g., main renal artery, main renal artery and branches) or ultrasound. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs of RDN interventions in patients with UH or RH to determine their effects on several intermediate and clinical outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Searches

A comprehensive literature search was performed on 1 May 2020 in PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science, the Cochrane library, and clinicaltrials.gov. Keywords were renal denervation, resistant hypertension, uncontrolled hypertension, randomized controlled trials; the PubMed search strategy is available in the Supplemental File.

2.2. Study Selection

Abstracts were independently selected by three investigators (JS, VP, JJB). Inclusion criteria were RCTs in ≥18 years-old with RH and/or UH and evaluating RDN interventions such as radiofrequency (RF) in main renal artery (MRA) and branches, RF in MRA, RF in MRA plus antihypertensive therapy (AHT), ultrasound (US) in MRA, sham, and AHT. RCTs with at least one outcome of interest were included. We excluded animal and observational studies. We did not restrict RCTs by sample size, follow-up time, or language. Full texts were reviewed for studies whose eligibility was questioned. Discrepancies were solved by discussion between investigators and a senior investigator (AVH).

Primary outcomes were mean 24-h ambulatory and office SBP. Secondary outcomes were mean 24-h ambulatory and office DBP, daytime SBP and DBP, nighttime SBP and DBP, and the following clinical outcomes: overall mortality, cardiovascular (CV) mortality, stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), hypertensive crisis, heart failure, hospitalization of any cause, renal complications (e.g., doubling of serum creatinine, end stage renal disease), and serious adverse events (SAEs). We used definitions of clinical outcomes as used in the original studies.

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Three investigators (JS, VP, JJB) independently extracted trial information (trial acronym, year of publication, sample size, trial phase, number of RDN interventions, follow-up time, type of patients, type and definition of RDN interventions), patient characteristics (age, body mass index (BMI), proportion of male, races, smokers, history of type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease (CAD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), number and types of antihypertensives at baseline), and outcome data per trial arm.

The 2019 Cochrane risk-of-bias (RoB) tool 2.0 was used to assess the risk of bias of RCTs [10]. This evaluated several domains that bias may have risen from: randomization process, deviations from intended interventions (effect of assignment to intervention), missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and selection of the reported result. The risk of bias per domain followed an algorithm to conclude the existence of low risk, some concerns, or high risk per domain and per trial. Discrepancies in data extraction or risk of bias assessment were solved by discussion between investigators and a senior investigator (AVH).

2.4. Data Synthesis and Analysis

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Network Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-NMA) guidelines were used to report this systematic review [11].

Inverse variance random-effects meta-analyses were used for all meta-analyses. Effects of RDN on outcomes were expressed as mean differences (MDs) for continuous outcomes, and relative risks (RR) for dichotomous outcomes with their 95% CIs. Best interventions were ranked with the p-score, where best interventions had values closer to one. Statistical heterogeneity of effects among RCTs were evaluated using the I2 statistic, with values of <30%, 30–60%, and >60% corresponding to low, medium, and high heterogeneity, respectively. Publication bias was tested with the Egger’s test if more than ten RCTs were available.

To compare all RDN interventions to one another, we conducted network meta-analyses (NMA) within a frequentist framework [12]. The geometry of the networks per outcome was assessed regarding specific treatments, studies with specific direct comparisons, and individuals randomly assigned to each intervention. RCTs were assessed for similarity or transitivity based on the evaluation of patient characteristics (age, BMI, number of AHT drugs at baseline, type of hypertension) and trial design (sample size, type of RDN intervention, outcomes, follow-up time). NMA comparisons were also assessed for consistency between direct and indirect effects with a test of disagreement for each comparison as well as the Cochran’s Q statistic for the overall network [13]. Sensitivity analyses were performed for trials with a 6-month follow-up time and those only including RH patients.

When NMAs were not possible due to scarcity of events and/or trial arms, we conducted traditional pairwise meta-analyses between one specific RDN intervention and a given control. We then used the treatment arm continuity correction (TACC) method to correct for zero events in trial arms and the Paule–Mandel method for calculating between-study variance tau2. R 3.5.3 software (www.r-project.org, accessed on 20 December 2020) was used for statistical analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

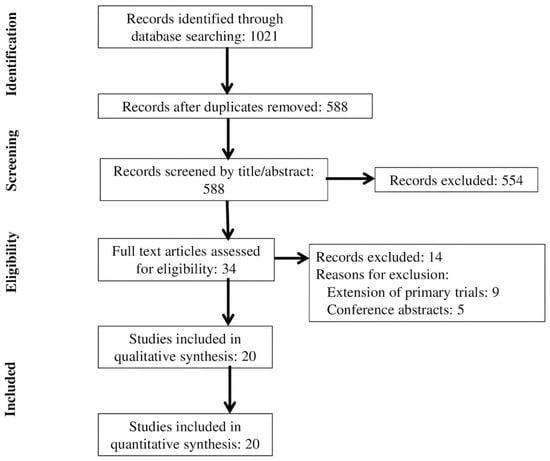

We identified 588 unique articles through a review of titles and abstracts. We assessed 34 full text articles for eligibility, and after review we excluded 14 articles that were extensions of primary trials (n = 9) or conference abstracts (n = 5) (Figure 1). Twenty RCTs (n = 2152) were included in the final analysis [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33].

Figure 1.

Flowchart of trial selection.

3.2. Trial Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes key characteristics of RCTs evaluated. Six out of 20 RCTs were performed in multiple countries, and sample sizes ranged from 15 to 535 participants. RH patients were enrolled in 15 studies (n = 1544) [16,19,20,21,22,23,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33], and UH patients were enrolled in three studies (n = 608) [14,15,17,18,24]. Mean ages ranged from 48 to 64 years-old, mean BMI 27.5 to 34.3 kg/m2, and mean number of antihypertensive drugs zero to five. Follow-up time ranged from two to six months, with six months being the majority (n = 14).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included randomized controlled trials.

The most common definition of RH included office SBP ≥140 mmHg and ≥ three antihypertensive medications at maximally tolerated doses, with one being a diuretic. The most common definition of UH included office SBP 150–180 mmHg, mean 24-h ambulatory SBP 140–170 mmHg, and ≤three antihypertensive medications. Intervention arms and number of RCTs with available interventions were the following: RF in MRA and branches (n = 4), RF in MRA (n = 10), RF in MRA plus AHT (n = 5), US in MRA (n = 3), sham (n = 8), and AHT (n = 9). Network geometries for 24-h ambulatory BPs, office BPs, and daytime and nighttime DBP showed direct comparisons for RF MRA vs. antihypertensive or sham as well as for sham vs. US MRA or RF MRA and branches (Figure S1A–D,G,H). For daytime and nighttime SBP, network geometries showed direct comparisons for RF MRA and branches vs. RF MRA vs. US MRA (Figure S1E,F).

3.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

Figure S2 summarizes the risk of bias per domain. Most trials had low risk of bias for each domain: randomization process (80%), deviations from intended interventions (89%), missing outcome data (70%), measurement of the outcome (55%), selection of the reported result (80%). Missing outcome data was a high risk of bias in one trial. Overall, there was some concern of bias in the majority of trials (n = 12; 60%), which came mostly from measurement of the outcome, missing outcome data, and selection of the reported result. Five trials had low overall risk (25%), and one trial had high overall risk (5%).

3.4. Network Meta-Analyses of Primary Outcomes

RF in MRA and branches had a significantly larger reduction in 24-h ambulatory SBP compared to RF in MRA (MD −7.8 mmHg, 95% CI −15.1 to −0.4), to RF in MRA plus AHT (MD −11.9 mmHg, 95% CI −23.4 to −0.4), to sham (MD −7.2 mmHg, 95% CI −13.6 to −0.8), and to AHT (MD −12.9 mmHg, 95% CI −22.6 to −3.2) (Table 2).

Table 2.

League table of the effects of treatments expressed as MD and their 95%CIs on 24-h ambulatory systolic blood pressure (white cells) and 24 h ambulatory diastolic blood pressure (gray cells).

For 24-h ambulatory SBP, RF in MRA and branches showed the largest reduction in comparison to other treatments (Figure S3). For office SBP, RF in MRA plus AHT showed the largest reduction in comparison to other treatments; however, 95%CIs were largely overlapping (Table 3, Figure S4).

Table 3.

League table of the effects of treatments expressed as MD and their 95%CIs on office systolic blood pressure (white cells) and office diastolic blood pressure (gray cells).

RF in MRA and branches ranked as the best among other interventions for reducing 24-h ambulatory SBP (p-score = 0.97); AHT ranked as the worst intervention. For office SBP, RF in MRA plus AHT ranked as the best intervention (p-score = 0.84); US MRA ranked as the worst intervention. Consistency of the networks was moderate for 24h ambulatory SBP (p = 0.03) and high for office SBP (p = 0.74).

3.5. Network Meta-Analyses of Secondary Outcomes

RF in MRA and branches had a significantly larger reduction in 24-h ambulatory DBP compared to RF in MRA (MD −4.2 mmHg, 95%CI −8.3 to −0.2), to sham (MD −3.7 mmHg, 95%CI −7.1 to −0.2), and AHT (−6.8 mmHg, 95%CI −12.7 to −0.8) (Table 2). RF in MRA and branches showed the largest reduction in comparison to other treatments for 24-h ambulatory DBP, daytime SBP and DBP, and nighttime SBP and DBP (Figures S5, S7–S10, Tables S1 and S2). For office DBP, RF in MRA plus AHT had a significantly larger reduction compared to AHT (MD −5.4 mmHg, 95%CI −9.6 to −1.1) (Table 3) and showed the largest reduction in comparison to other treatments (Figure S6).

RF in MRA and branches ranked as the best among other interventions for reducing 24-h ambulatory DBP, daytime SBP and DBP, and nighttime SBP and DBP (p-scores: 0.83 to 0.97) (Table S3). AHT ranked as the worst intervention for reducing 24-h ambulatory DBP and nighttime SBP and DBP. RF MRA plus AHT ranked as the worst intervention for reducing daytime SBP and DBP. RF in MRA plus AHT ranked as the best among other interventions for reducing office DBP (p-score = 0.90) (Table S3); sham ranked as the worst intervention. Consistency of the networks was moderate for daytime and nighttime SBP (p = 0.07 and 0.08, respectively) and high for other secondary outcomes (p range: 0.39 to 0.87).

3.6. Sensitivity Analyses

For RCTs with a 6-month follow-up time, rankings of best treatments were similar to main analyses of all primary and secondary outcomes. RF in MRA and branches ranked the highest for 24-h ambulatory, daytime, and nighttime SBP and DBP (p-scores: 0.78 to 0.96), and RF in MRA plus AHT ranked the highest for office SBP and DBP (p-scores: 0.91 and 0.96, respectively).

For RCTs that included only RH patients, rankings of best treatments were similar to main analyses of 24-h ambulatory and daytime SBP and DBP (RF in MRA and branches p-scores: 0.74 to 0.97) and office SBP and DBP (RF in MRA and AHT p-scores: 0.80 and 0.89, respectively). A difference in rankings was seen in nighttime SBP and DBP, with sham procedure having the highest ranking (p-scores: 0.69 and 0.65, respectively).

3.7. Effect of Renal Denervation on Clinical Outcomes

Due to scarcity of clinical outcomes and treatment arms being compared, NMAs were not possible. We then evaluated the effect of some types of RDN interventions (RF MRA, RF MRA and branches, RF MRA plus AHT) vs. controls (sham, AHT) on clinical outcomes in traditional pairwise meta-analyses (Table S4, Figures S11–S26). Clinical outcomes with at least data in two studies were heart failure, stroke, MI, renal complications, hypertensive crisis, and SAEs. None of the effects of RDN interventions on clinical outcomes were significant.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

We found that RF in MRA and branches was the best intervention to reduce 24-h ambulatory, and daytime and nighttime SBP and DBP compared to other interventions. Only 24-h ambulatory SBP and DBP were significantly reduced in most of comparisons. RF in MRA plus AHT was the best intervention to reduce office SBP and DBP compared to other interventions, but neither effect was significant. Best RDN interventions were similar after analyses in 6-month follow-up and RH only trials. We did not find any significant effect of RDN interventions on scarce clinical outcome data. Most trials had overall low risk or some concern of bias.

4.2. What Is Known in the Literature

RH is estimated to affect 10% of individuals with hypertension [34]; 54% of individuals with hypertension are uncontrolled [2]. Among individuals with UH, 39.4% were unaware of their hypertension, 15.8% were aware but not on any medication, and 44.8% were aware and not at maximally tolerated doses [2].

RDN procedures most commonly use either RF or US energy. The first-generation RF ablation catheter, Symplicity Flex® (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA), was used in several RDN RCTs [20,21,23,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. The second-generation RF ablation catheter, Symplicity Spyral® (Medtronic), was used in more recent RCTs [16,18,24]. The Paradise US catheter® (ReCor Medical, Palo Alto, CA, USA) has been used in two recent RCTs [16,17].

The efficacy of RDN has been previously evaluated in several SRs (Table S5) [5,6,7,8,9]. Coppolino et al., Yao et al., and Fadl Elmula et al. included only RH patients [7,8,9]. Cheng et al. included only UH patients [5], and Dahal et al. included patients with both RH and UH [6]. All SRs included between 985 and 1539 individuals. All except Fadl Elmula et al. assessed risk of bias with the 2011 Cochrane tool. Both Fadl Elmula et al. and Coppolino et al. concluded that RDN did not have a significant effect on BP vs. no intervention and standard treatment or sham, respectively. Yao et al. concluded that RF RDN was not superior to standard treatment. Both Cheng et al. and Dahal et al. concluded that RDN significantly reduced 24-h ambulatory SBP vs. any control and sham, respectively. Additionally, Cheng et al. found a significant reduction in office SBP, and Dahal et al. found a significant reduction in 24-h ambulatory and office DBP.

Coppolino et al. and Cheng et al. assessed the effect of RDN on clinical outcomes. Coppolino et al. showed low quality evidence that RDN did not affect major CV events or renal function but did increase bradycardia events. Cheng et al. concluded that RDN did not increase major adverse events (Table S5). Several meta-analyses have shown that BP reduction is associated with a lower incidence of CV events. The HOPE-3 trial showed that patients with an SBP reduction of −5.8/−3.0 mmHg (baseline office SBP > 143.5 mmHg) experienced 28% fewer CV events when treated with AHT vs. placebo [35]. CV outcomes have not been evaluated as primary outcomes in any RDN trials to date, but it is estimated that a 10-mmHg reduction in office SBP maintained after RDN among individuals with an average age of 65 years-old would be associated with a 25% lower incidence of CV events [3].

Mahfoud et al. conducted a single-arm trial of alcohol-mediated renal denervation using the Peregrine Catheter in patients with hypertension, which showed promising results in patients with UH. The ambulatory and office BPs were significantly reduced by −11/−7 mm Hg, respectively, after 6 months. Within 1 month of procedure, there was no report of any major adverse events and death in 95% of patients. Further studies or RCTs are needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of the procedure and compare them to other available treatments [36].

4.3. What Our Study Adds to the Literature

We performed an NMA of all available and most updated RDN interventions, which no previous SR has performed. Our study evaluated newer RDN interventions such as RF MRA and branches and US MRA. We found that RF MRA and branches consistently provided the largest reduction in 24-h ambulatory, daytime and nighttime SBP and DBP. The Symplicity Spyral was specifically designed to also treat RA branches with a diameter of 3 to 8 mm [4]. Having a higher number of ablated sites may improve the chance of hitting pressor nerves around the arteries [3]. This concept is also supported by the moderate effect achieved by the US intervention [17].

We used follow-up times specified in the primary outcomes, even in cases when the RCTs were followed up beyond that time point. We also performed sensitivity analyses by removing studies with follow-up shorter than six months and found results consistent with main analyses. Eight different BP outcomes were evaluated, including both in-office and out-of-office measurements. Ambulatory BP monitoring is regarded as a more accurate BP measuring option as it avoids the “white coat effect” of office point-of-care BP measures [37].

We found data from two to five RCTs for heart failure, stroke, MI, renal complications, and hypertensive crisis. Additionally, SAEs were available in two to three RCTs. NMAs were not possible though. Our pairwise meta-analyses comparing RF MRA +/− branches to sham did not find significant effects on any of the clinical outcomes. Other clinical outcomes such as overall mortality, CV mortality, and hospitalizations of any cause were available for one or none of the RCTs. Pairwise meta-analyses comparing RF MRA +/− branches or AHT to sham or AHT did not show significant differences for SAEs. We will need more clinical outcome data in future trials to elucidate the effects of RDN interventions on harder outcomes.

Our study also ranked RDN interventions per outcome by using p-scores in the context of NMA. P-scores are equivalent to the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) in Bayesian NMA [38]. Finally, we used the new 2019 Cochrane risk-of-bias tool 2.0 to evaluate the risk of bias for each RCT. In contrast to the old 2011 version, items have been grouped in domains of bias, decisions per domain include the option of some concern of bias instead of “unclear risk of bias”, and documentation is more detailed.

4.4. Limitations

First, we identified heterogeneity among included RCTs in terms of age, sex, BMI, type of population, and follow-up time. To adjust for heterogeneity, we performed sensitivity analyses on RCTs including only RH patients and only trials with a 6-month follow-up time. For most outcomes, results were consistent with the main analyses. Second, the majority of included RCTs had some concern of bias, coming mainly from measurement of the outcome, missing outcome data, and selection of the reported result; one RCT of 81 RH patients had a high risk of bias because of missing outcome data [19]. Third, the mean number of AHT drugs varied among 15 RH RCTs, ranging from three to five; this may change the baseline risk of patients undergoing RDN interventions. Lastly, there was scarce data available to analyze clinical outcomes, so we could not conduct NMA on these outcomes. Instead, we performed traditional pairwise meta-analyses between one specific RDN intervention and a given control. Data for overall mortality, CV mortality, and hospitalizations were very scarce, in line with previous SRs [5,6,7,8,9].

5. Conclusions

Our systematic review and network meta-analyses found that RF in MRA and branches was the most efficacious RDN intervention compared to other interventions to reduce BP outcomes in RH or UH populations. No significant difference in the effect of RDN on clinical outcomes was found, but data were scarce and outcomes were uncommonly described in existing trials. More clinical outcome data is needed from future trials to further assess the efficacy and safety of RDN interventions.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/10/4/782/s1, Supplemental Methods: PubMed search strategy; Table S1: League table of the effects of treatments expressed as MD and their 95%CIs on daytime systolic blood pressure (white cells) and daytime diastolic blood pressure (gray cells); Table S2: League table of the effects of treatments expressed as MD and their 95%CIs on nighttime systolic blood pressure (white cells) and nighttime diastolic blood pressure (gray cells); Table S3: Ranking of renal denervation treatments per outcome; Table S4: Meta-analyses of clinical outcomes; Table S5: Characteristics of previously published systematic reviews compared to our study; Figure S1: Network geometries for primary and secondary outcomes; Figure S2: Risk of bias per domain of included randomized trials; Figure S3: Effect of renal denervation interventions on change of 24 h ambulatory SBP in comparison to antihypertensive drugs; Figure S4: Effect of renal denervation interventions on change of office SBP in comparison to antihypertensive drugs; Figure S5: Effect of renal denervation interventions on change of 24 h ambulatory DBP in comparison to antihypertensive drugs; Figure S6: Effect of renal denervation interventions on change of office DBP in comparison to antihypertensive drugs; Figure S7: Effect of renal denervation interventions on change of daytime SBP in comparison to antihypertensive drugs; Figure S8: Effect of renal denervation interventions on change of nighttime SBP in comparison to antihypertensive drugs; Figure S9: Effect of renal denervation interventions on change of daytime DBP in comparison to antihypertensive drugs; Figure S10: Effect of renal denervation interventions on change of nighttime DBP in comparison to antihypertensive drugs; Figure S11: Effect of RF MRA vs. sham on heart failure; Figure S12: Effect of RF MRA vs. sham on stroke; Figure S13: Effect of RF MRA + branch vs. sham on stroke; Figure S14: Effect of RF MRA +/− branch vs. sham on stroke; Figure S15: Effect of RF MRA vs. sham on myocardial infarction; Figure S16: Effect of RF MRA + branch vs. sham on myocardial infarction; Figure S17: Effect of RF MRA +/− branch vs. sham on myocardial infarction; Figure S18: Effect of RF MRA vs. sham on renal complications; Figure S19: Effect of RF MRA + branch vs. sham on renal complications; Figure S20: Effect of RF MRA +/− branch vs. sham on renal complications; Figure S21: Effect of RF MRA vs. sham on hypertensive crisis; Figure S22: Effect of RF MRA + branch vs. sham on hypertensive crisis; Figure S23: Effect of RF MRA +/− branch vs. sham on hypertensive crisis; Figure S24: Effect of RF MRA vs. sham on serious adverse events; Figure S25: Effect of RF MRA + AHT vs. AHT on serious adverse events; Figure S26: Effect of RF MRA +/− branch vs. sham on serious adverse events.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V.H.; methodology, A.V.H.; software, Y.M.R. and A.V.H.; validation, A.V.H., V.P., and J.J.B.; formal analysis, J.S., K.E.M., M.T.P., H.A., V.P., M.B., Y.M.R., and A.V.H.; investigation, J.S., K.E.M., M.T.P., H.A., M.B., V.P., Y.M.R., and A.V.H.; resources, A.V.H.; data curation, J.S., K.E.M., M.T.P., H.A., V.P., and A.V.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S., K.E.M., Y.M.R., and A.V.H.; writing—review and editing, J.S., K.E.M., M.T.P., H.A., M.B., J.J.B., V.P., Y.M.R., and A.V.H.; resources, V.P. and A.V.H.; visualization, V.P., Y.M.R., and A.V.H.; supervision, A.V.H.; project administration, Y.M.R. and A.V.H.; funding acquisition, A.V.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Carey, R.M.; Calhoun, D.A.; Bakris, G.L.; Brook, R.D.; Daugherty, S.L.; Dennison-Himmelfarb, C.R.; Egan, B.M.; Flack, J.M.; Gidding, S.S.; Judd, E.; et al. Resistant hypertension: Detection, evaluation, and management: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension 2018, 72, e53–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valderrama, A.L.; Gillespie, C.; King, S.C.; George, M.G.; Hong, Y.; Gregg, E. Vital signs: Awareness and treatment of uncontrolled hypertension among adults-United States, 2003–2010. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2012, 61, 703–709. [Google Scholar]

- Kiuchi, M.G.; Esler, M.D.; Fink, G.D.; Osborn, J.W.; Banek, C.T.; Böhm, M.; Denton, K.M.; DiBona, G.F.; Everett, T.H.; Grassi, G.; et al. Renal denervation update from the International Sympathetic Nervous System Summit. JACC 2019, 73, 3006–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.A.; Mahfoud, F.; Schmieder, R.E.; Kandzari, D.E.; Tsioufis, K.P.; Townsend, R.R.; Kario, K.; Böhm, M.; Sharp, A.S.; Davies, J.E.; et al. Renal denervation for treating hypertension: Current scientific and clinical evidence. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 12, 1095–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Zhang, D.; Luo, S.; Qin, S. Effect of catheter-based renal denervation on uncontrolled hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019, 94, 1695–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, K.; Khan, M.; Siddiqui, N.; Mina, G.; Katikaneni, P.; Modi, K.; Azrin, M.; Lee, J. Renal denervation in the management of hypertension: A meta-analysis of sham-controlled trials. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 2019, 21, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppolino, G.; Pisano, A.; Rivoli, L.; Bolignano, D. Renal denervation for resistant hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2, CD011499. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Zhang, D.; Qian, J.; Deng, S.; Huang, Y.; Huang, J. The effect of renal denervation on resistant hypertension: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2016, 38, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadl Elmula, F.E.M.; Jin, Y.; Yang, W.Y.; Thijs, L.; Lu, Y.C.; Larstorp, A.C.; Persu, A.; Sapoval, M.; Rosa, J.; Widimský, P.; et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of renal denervation in treatment-resistant hypertension. Blood Press. 2015, 24, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, 14898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, B.; Salanti, G.; Caldwell, D.M.; Chaimani, A.; Schmid, C.H.; Cameron, C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Straus, S.; Thorlund, K.; Jansen, J.P.; et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: Checklist and explanations. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoaglin, D.C.; Hawkins, N.; Jansen, J.P.; Scott, D.A.; Itzler, R.; Cappelleri, J.C.; Boersma, C.; Thompson, D.; Larholt, K.M.; Diaz, M.; et al. Conducting indirect-treatment-comparison and network-meta-analysis studies: Report of the ISPOR task force on indirect treatment comparisons good research practices: Part 2. Value Health 2011, 14, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Jackson, D.; Barrett, J.K.; Lu, G.; Ades, A.E.; White, I.R. Consistency and inconsistency in network meta-analysis: Concepts and models for multi-arm studies. Res. Synth. Methods 2012, 3, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.A.; Kirtane, A.J.; Weir, M.R.; Radhakrishnan, J.; Das, T.; Berk, M.; Mendelsohn, F.; Bouchard, A.; Larrain, G.; Haase, M.; et al. The REDUCE HTN: REINFORCE: Randomized, Sham-Controlled Trial of Bipolar Radiofrequency Renal Denervation for the Treatment of Hypertension. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, M.; Townsend, R.R.; Kario, K.; Mahfoud, F.; Weber, M.A.; Schmieder, R.E.; Tsioufis, K.; Pocock, S.; Konstantinidis, D.; Choi, J.W.; et al. Efficacy of catheter-based renal denervation in the absence of antihypertensive medications (SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED Pivotal): A multicentre, randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1444–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fengler, K.; Rommel, K.P.; Blazek, S.; Besler, C.; Hartung, P.; von Roeder, M.; Petzold, M.; Winkler, S.; Höllriegel, R.; Desch, S.; et al. A three-arm randomized trial of different renal denervation devices and techniques in patients with resistant hypertension (RADIOSOUND-HTN). Circulation 2019, 139, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi, M.; Schmieder, R.E.; Mahfoud, F.; Weber, M.A.; Daemen, J.; Davies, J.; Basile, J.; Kirtane, A.J.; Wang, Y.; Lobo, M.D.; et al. Endovascular ultrasound renal denervation to treat hypertension (RADIANCE-HTN SOLO): A multicentre, international, single-blind, randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 2335–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandzari, D.E.; Böhm, M.; Mahfoud, F.; Townsend, R.R.; Weber, M.A.; Pocock, S.; Tsioufis, K.; Tousoulis, D.; Choi, J.W.; East, C.; et al. Effect of renal denervation on blood pressure in the presence of antihypertensive drugs: 6-month efficacy and safety results from the SPYRAL HTN-ON MED proof-of-concept randomised trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 2346–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmieder, R.E.; Ott, C.; Toennes, S.W.; Bramlage, P.; Gertner, M.; Dawood, O.; Baumgart, P.; O’Brien, B.; Dasgupta, I.; Nickenig, G.; et al. Phase II randomized sham-controlled study of renal denervation for individuals with uncontrolled hypertension- WAVE IV. J. Hypertens. 2018, 36, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warchol-Celinska, E.; Prejbisz, A.; Kadziela, J.; Florczak, E.; Januszewicz, M.; Michalowska, I.; Dobrowolski, P.; Kabat, M.; Sliwinski, P.; Klisiewicz, A.; et al. Renal denervation in resistant hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea: Randomized proof-of-concept phase II trial. Hypertension 2018, 72, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jager, R.L.; de Beus, E.; Beeftink, M.M.A.; Sanders, M.F.; Vonken, E.J.; Voskuil, M.; van Maarseveen, E.M.; Bots, M.L.; Blankestijn, P.J.; SYMPATHY Investigators. Impact of medication adherence on the effect of renal denervation: The SYMPATHY trial. Hypertension 2017, 69, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, L.; Persu, A.; Huang, Q.F.; Lengelé, J.P.; Thijs, L.; Hammer, F.; Yang, W.Y.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Renkin, J.; Sinnaeve, P.; et al. Results of a randomized controlled pilot trial of intravascular renal denervation for management of treatment-resistant hypertension. Blood Press. 2017, 26, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekarskiy, S.E.; Baev, A.E.; Mordovin, V.F.; Semke, G.V.; Ripp, T.M.; Falkovskaya, A.U.; Lichikaki, V.A.; Sitkova, E.S.; Zubanova, I.V.; Popov, S.V. Denervation of the distal renal arterial branches vs. conventional main renal artery treatment: A randomized controlled trial for treatment of resistant hypertension. J. Hypertens. 2017, 35, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, R.R.; Mahfoud, F.; Kandzari, D.E.; Kario, K.; Pocock, S.; Weber, M.A.; Ewen, S.; Tsioufis, K.; Tousoulis, D.; Sharp, A.S.P.; et al. Catheter-based renal denervation in patients with uncontrolled hypertension in the absence of antihypertensive medications (SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED): A randomised, sham-controlled, proof-of-concept trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 2160–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiassen, O.N.; Vase, H.; Bech, J.N.; Christensen, K.L.; Buus, N.H.; Schroeder, A.P.; Lederballe, O.; Rickers, H.; Kampmann, U.; Poulsen, P.L.; et al. Renal denervation in treatment-resistant essential hypertension. A randomized, SHAM-controlled, double-blinded 24-h blood pressure-based trial. J. Hypertens. 2016, 34, 1639–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveras, A.; Armario, P.; Clarà, A.; Sans-Atxer, L.; Vázquez, S.; Pascual, J.; De la Sierra, A. Spironolactone versus sympathetic renal denervation to treat true resistant hypertension: Results from the DENERVHTA study- a randomized controlled trial. J. Hypertens. 2016, 34, 1863–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi, M.; Sapoval, M.; Gosse, P.; Monge, M.; Bobrie, G.; Delsart, P.; Midulla, M.; Mounier-Véhier, C.; Courand, P.Y.; Lantelme, P.; et al. Optimum and stepped care standardised antihypertensive treatment with or without renal denervation for resistant hypertension (DENERHTN): A multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 1957–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desch, S.; Okon, T.; Heinemann, D.; Kulle, K.; Röhnert, K.; Sonnabend, M.; Petzold, M.; Müller, U.; Schuler, G.; Eitel, I.; et al. Randomized sham-controlled trial of renal sympathetic denervation in mild resistant hypertension. Hypertension 2015, 65, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kario, K.; Ogawa, H.; Okumura, K.; Okura, T.; Saito, S.; Ueno, T.; Haskin, R.; Negoita, M.; Shimada, K.; SYMPLICITY HTN-Japan Investigators. SYMPLICITY HTN-Japan–First randomized controlled trial of catheter-based renal denervation in Asian patients. Circ. J. 2015, 79, 1222–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, J.; Widimský, P.; Toušek, P.; Petrák, O.; Čurila, K.; Waldauf, P.; Bednář, F.; Zelinka, T.; Holaj, R.; Štrauch, B.; et al. Randomized comparison of renal denervation versus intensified pharmacotherapy including spironolactone in true-resistant hypertension: Six-month results from the Prague-15 study. Hypertension 2015, 65, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, D.L.; Kandzari, D.E.; O’Neill, W.W.; D’Agostino, R.; Flack, J.M.; Katzen, B.T.; Leon, M.B.; Liu, M.; Mauri, L.; Negoita, M.; et al. A controlled trial of renal denervation for resistant hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1393–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadl Elmula, F.E.M.; Hoffmann, P.; Larstorp, A.C.; Fossum, E.; Brekke, M.; Kjeldsen, S.E.; Gjønnæss, E.; Hjørnholm, U.; Kjaer, V.N.; Rostrup, M.; et al. Adjusted drug treatment is superior to renal sympathetic denervation in patients with true treatment-resistant hypertension. Hypertension 2014, 63, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esler, M.D.; Krum, H.; Sobotka, P.A.; Schlaich, M.P.; Schmieder, R.E.; Böhm, M.; Symplicity HTN-2 Investigators. Renal sympathetic denervation in patients with treatment-resistant hypertension (The Symplicity HTN-2 Trial): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010, 376, 1903–1909. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ruilope, L.M.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, E.; Navarro-García, J.A.; Segura, J.; Órtiz, A.; Lucia, A.; Ruiz-Hurtado, G. Resistant hypertension: New insights and therapeutic perspectives. Resistant hypertension: New insights and therapeutic perspectives. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2019, 6, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, S.; Bosch, J.; Dagenais, G.; Zhu, J.; Xavier, D.; Liu, L.; Pais, P.; López-Jaramillo, P.; Leiter, L.A.; Dans, A.; et al. Cholesterol lowering in intermediate-risk persons without cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 2021–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfoud, F.; Renkin, J.; Sievert, H.; Bertog, S.; Ewen, S.; Böhm, M.; Lengelé, J.P.; Wojakowski, W.; Schmieder, R.; van der Giet, M.; et al. Alcohol-Mediated Renal Denervation Using the Peregrine System Infusion Catheter for Treatment of Hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. Interv. 2020, 13, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, E. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in the diagnosis and management of hypertension. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, S307–S311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rücker, G.; Schwarzer, G. Ranking treatments in frequentist network meta-analysis works without resampling methods. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2015, 15, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).