Abstract

The purpose of this study was to evaluate whether heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) is associated with vascular dysfunction and whether vascular function predicts future deterioration of LVEF in patients with HFmrEF. We evaluated endothelial function assessed by flow-mediated vasodilation (FMD) and vascular smooth muscle function assessed by nitroglycerine-induced vasodilation (NID) in 69 patients with HFmrEF and 426 patients without HF and evaluated the future deterioration of LVEF, defined as a decrease in LVEF to <40%, in 39 patients with HFmrEF for up to 3 years. Both FMD and NID were significantly lower in patients with HFmrEF than in patients without HF. We categorized patients into two groups based on low tertiles of NID: a low group (NID of <7.0%) and an intermediate and high group (NID of ≥7.0%). There were significant differences between the Kaplan–Meier curves for the deterioration of LVEF in the two groups (p < 0.01). Multivariate Cox proportional hazard analysis revealed that NID of <7.0% was an independent predictor of future deterioration of LVEF in patients with HFmrEF. Both endothelial function and vascular smooth muscle function are impaired in patients with HFmrEF compared with those in patients without HF. In addition, low NID of <7.0% predicts future deterioration of LVEF.

1. Introduction

The mortality rate of patients with heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) is comparable to that of patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and that of HF patients with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) [1,2]. Previous studies have clearly shown that vascular dysfunction plays an important role in the pathogenesis and maintenance of HF including HFrEF and HFpEF [3,4,5,6,7]. Both patients with HFrEF and patients with HFpEF had vascular dysfunction compared with patients without HF [5,6]. Although it is thought that HFmrEF also has vascular dysfunction, it remains unclear whether HFmrEF is associated with vascular dysfunction. Changes in left ventricular EF (LVEF) in patients with HF are a common occurrence [8,9]. Deterioration of LVEF in patients with HFmrEF increases mortality and/or HF hospitalization [9]. It is clinically important to predict future deterioration of LVEF in patients with HFmrEF. Although there are few predictors for deterioration of LVEF in patients with HFmrEF [10,11,12], there is no established predictor for deterioration of LVEF.

Endothelial dysfunction is initially impaired in atherosclerosis and leads to the development and progression of atherosclerosis [13,14]. Endothelial function was measured by flow-mediated vasodilation (FMD) and vascular smooth muscle function was measured by nitroglycerine-induced vasodilation (NID) [15,16]. Both FMD and NID have been widely used due to being noninvasive. Growing evidence has shown that both FMD and NID can serve as independent predictors of cardiovascular events [17,18,19]. In addition, several studies showed that there were relationships of HF with vascular function assessed by FMD and NID and with vascular structure assessed by brachial intima-media thickness (IMT) and brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV) [3,5,6,20].

The purpose of this study was to evaluate vascular function and vascular structure in patients with HFmrEF. In addition, we determined whether assessment of vascular function can be used for risk stratification regarding deterioration of LVEF in patients with HFmrEF.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Protocol 1

This study was a single-center, retrospective longitudinal cohort study. Between April 2010 and May 2020, a total of 240 patients with HF underwent FMD, NID, brachial IMT, and baPWV measurements and echocardiography, and 463 subjects without HF underwent FMD, NID, brachial IMT, and baPWV measurements and echocardiography. In total, 171 of the 240 patients who had HF, comprising 20 patients with severe renal dysfunction, 23 patients using nitrates, 44 patients with HFrEF, and 84 patients with HFpEF, were excluded. Finally, 69 patients with HFmrEF were enrolled in this study. We defined patients with no symptoms, no signs of HF, and either normal NT-proBNP or normal echocardiography on the basis of diagnostic criteria of the European Working Group for HF as patients without HF [21]. Furthermore, 37 of the 463 patients without HF, comprising 19 patients with severe renal dysfunction and 18 patients using nitrates, were excluded. Finally, 426 patients without HF were enrolled in this study.

Patients with HF were patients with symptoms or signs of HF and who were diagnosed with HF at Hiroshima University Hospital. HF was defined according to the diagnostic criteria of the European Society of Cardiology guidelines [21]. Patients with LVEF of ≥50%, LVEF of 40–49%, and LVEF of <40% were defined as patients with HFpEF, HfmrEF, and HFrEF, respectively.

Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure of more than 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure of more than 90 mmHg in a sitting position measured on at least three different occasions. Diabetes mellitus was defined according to the American Diabetes Association or a previous diagnosis of diabetes [22]. Dyslipidemia was defined according to the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program [23].

We assessed vascular function using measurements of FMD and NID and vascular structure using measurements of brachial IMT and baPWV. Subjects fasted the previous night for at least 12 h and the study began at 8:30 a.m. The subjects were kept in a supine position in a quiet, dark, and air-conditioned room (constant temperature of 22–25 °C) throughout the study. A 23-gauge polyethylene catheter was inserted into the left deep antecubital vein to obtain blood samples. After thirty minutes of the subjects maintaining a supine position, we measured FMD, NID, brachial IMT, and baPWV. The observers were blind to the clinical status of the subjects and the purposes of the study [6].

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The Ethics Review Board of Hiroshima University approved the study protocol (UMIN000003409). Written informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from all of the subjects.

2.2. Study Protocol 2

In this study, referred to as the follow-up study, we selected patients with HFmrEF for further study who had at least one additional transthoracic echocardiogram every year for up to three years after the baseline study. Finally, 39 patients with HFmrEF were enrolled in the follow-up study. The primary endpoint was deterioration of LVEF, defined as a decrease in LVEF to <40%.

2.3. Measurements of FMD and NID

Vascular response to reactive hyperemia in the brachial artery was used for assessment of endothelium-dependent FMD. A high-resolution linear artery transducer was coupled to computer-assisted analysis software (UNEXEF18G, UNEX Co, Nagoya, Japan) that used an automated edge detection system for measurement of brachial artery diameter [18]. The response to nitroglycerine was used for assessment of endothelium-independent vasodilation. NID was measured as described previously [18]. Additional details are available in Supplementary Materials.

2.4. Measurement of Brachial IMT

Before FMD measurement, baseline longitudinal ultrasonographic images of the brachial artery, obtained at the end of diastole from each of 10 cardiac cycles, were automatically stored on a hard disk for offline assessment of IMT with a linear, phased-array high-frequency (10 MHz) transducer using an UNEXEF18G ultrasound unit (UNEX Co) [24]. Additional details are available in Supplementary Materials.

2.5. Measurement of baPWV

Aortic compliance was assessed noninvasively on the basis of Doppler ultrasound measurements of PWV along the descending thoracoabdominal aorta, as previously reported and validated [25]. Briefly, baPWV, an index of arterial stiffness, was determined by two pressure sensors placed on the right ankle and left brachial arteries to record each pulse wave simultaneously (Form PWV/ABI, model BP-203RPE, Colin Co., Tokyo, Japan). The distance (D) between the two recording sensors was calculated automatically by inputting the value of individual height. The PWV value was calculated as PWV = D/t. PWV was measured for five consecutive pulses, and averages were used for analysis.

2.6. Echocardiography

Echocardiograms were obtained by using a Philips iE33 (Philips Co. Ltd., Bothell, WA, USA) with a 1.0 to 5.0 MHz transducer (S5-1). Routine two-dimensional imaging examinations were performed in parasternal long-axis and short-axis views and apical two-chamber and four-chamber views. Left atrial (LA) volume was measured by the biplane area–length formula and indexed for body surface area. LV mass was calculated according to the Penn Convention. LVEF was calculated by the modified Simpson formula.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as means ± SD for continuous variables and as percentages for categorical variables. Statistical significance was set at a level of p < 0.05. Categorical variables were compared by means of the χ2 test. Continuous variables were compared by ANOVA. One-to-one propensity-score matching analyses were used to create matched pairs to investigate the associations of HFmrEF with vascular function and vascular structure. The propensity score was calculated for each patient on the basis of logistic regression analysis of the probability of HFmrEF including age, sex, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, hypertension (yes/no), dyslipidemia (yes/no), diabetes mellitus (yes/no), and current smoking (yes/no). With these propensity scores, two well-matched groups based on clinical characteristics were created with a caliper width of 0.02 for comparison of vascular function. Time-to-event end point analyses were performed by using the Kaplan–Meier method. We categorized subjects into two groups according to the low tertiles of NID (<7.0%). The log-rank test was used to compare the groups. We evaluated the associations of deterioration of LVEF with NID after adjustment for age, sex, and cardiovascular risk factors by using Cox proportional hazard regression analysis. The number of variables that could enter the multivariate model was limited using the p < m/10 rule to prevent overfitting of the model. The data were processed using JMP Pro version 15 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Study Protocol 1: Vascular Function and Vascular Structure in Patients with HFmrEF

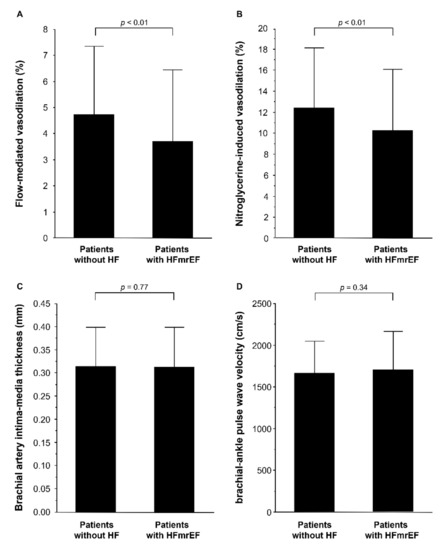

The baseline clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. Of the 495 patients, 310 (62.6%) were men, 376 (76.1%) had hypertension, 315 (63.6%) had dyslipidemia, 135 (27.2%) had diabetes mellitus, 114 (23.1%) had previous coronary heart disease, and 76 (15.5%) were current smokers. Echocardiographic parameters of the 426 patients without HF and 69 patients with HFmrEF are summarized in Table 1. LV end-diastolic dimension index, LV end-systolic dimension index, LV mass index, and LA volume index were significantly higher in patients with HFmrEF than in patients without HF. EF was significantly lower in patients with HFmrEF than in patients without HF. FMD was significantly lower in patients with HFmrEF than in patients without HF (3.7 ± 2.7% versus 4.7 ± 2.5%, p < 0.01; Figure 1A). NID was significantly lower in patients with HFmrEF than in patients without HF (10.3 ± 5.9% versus 12.7 ± 5.7%, p < 0.01; Figure 1B). There was no significant difference in brachial IMT (0.32 ± 0.09 mm versus 0.32 ± 0.09 mm, p = 0.77; Figure 1C) and baPWV (1648 ± 372 cm/s versus 1705 ± 459 cm/s, p = 0.34; Figure 1D) between patients without HF and patients with HFmrEF.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the subjects correspond to Study Protocol 1.

Figure 1.

Bar graphs show flow-mediated vasodilation (A); nitroglycerine-induced vasodilation (B); brachial intima-media thickness (C), and brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity (D) in patients without heart failure (HF) and patients with heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF).

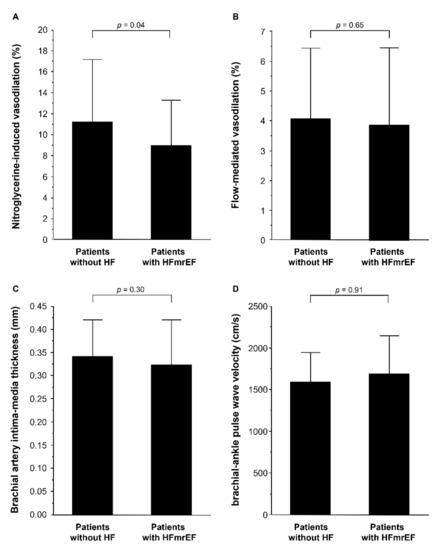

In addition, we evaluated vascular function in patients with HFmrEF and control subjects using the propensity score matching method to make matched pairs between patients without HF and patients with HFmrEF. The clinical characteristics of matched pairs of patients without HF and patients with HFmrEF are summarized in Table 2. NT-proBNP was significantly higher in patients with HFmrEF than in patients without HF. The percentage of patients using diuretics was significantly higher in patients with HFmrEF than in patients without HF. LV end-diastolic dimension index, LV end-systolic dimension index, and LV mass index were significantly higher in patients with HFmrEF than in patients without HF. LVEF was significantly lower in patients with HFmrEF than in patients without HF. NID was significantly lower in patients with HFmrEF than in patients without HF (8.9 ± 4.3% versus 11.2 ± 6.0%, p = 0.04; Figure 2A). There was no significant difference in FMD (4.0 ± 2.4% versus 3.8 ± 2.6%, p = 0.65; Figure 2B), brachial IMT (0.34 ± 0.08 mm versus 0.32 ± 0.10 mm, p = 0.30; Figure 2C), and baPWV (1594 ± 356 cm/s versus 1692 ± 458 cm/s, p = 0.91; Figure 2D) between patients without HF and patients with HFmrEF.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of well-matched pairs of the subjects correspond to study protocol 1.

Figure 2.

Bar graphs show nitroglycerine-induced vasodilation (A); flow-mediated vasodilation (B); brachial intima-media thickness (C), and brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity (D) in patients without heart failure (HF) and patients with heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) in propensity match population.

3.2. Study Protocol 2: Association of NID with Future Deterioration of LVEF in Patients with HFmrEF

The baseline clinical characteristics of the 39 patients with HFmrEF are summarized in Table 3. We categorized patients into two groups based on low tertiles of NID. The intermediate and high group had NID of ≥7.0% (12.4 ± 5.6%) and the low group had NID of <7.0% (4.0 ± 1.7%). There was no significant difference in other parameters between the two groups.

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of the patients with HFmrEF in follow-up study.

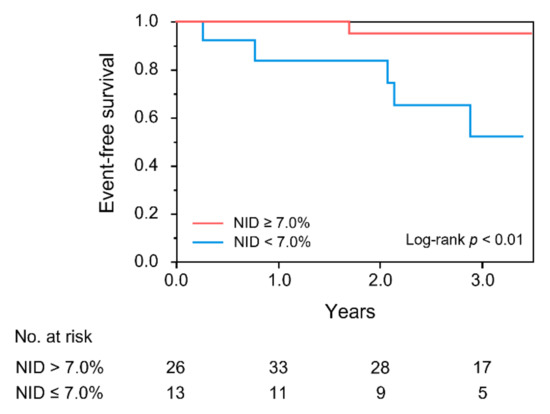

During a median period of 2.6 years (interquartile range, 2.3–3.1 years) of follow-up, six patients had deteriorated LVEF. The Kaplan–Meier curves for the deterioration of LVEF between the two groups according to NID were significantly different (p < 0.01; Figure 3). Multivariate Cox proportional hazard analysis revealed that NID of <7.0% was an independent predictor of future deterioration of LVEF in patients with HFmrEF in Models 1 to 5 (Table 4).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves of cumulative event-free survival of patients with heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction according to nitroglycerine-induced vasodilation (NID). The primary endpoint was deterioration of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), defined as a decrease in LVEF to <40%.

Table 4.

Association between nitroglycerine-induced vasodilation and ejection fraction deteriorated during follow-up.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we showed that both endothelial function assessed by FMD and vascular smooth muscle function assessed by NID were impaired in patients with HFmrEF compared with those in patients without HF, and we showed by using propensity score matching analysis that vascular smooth muscle function was impaired in patients with HFmrEF compared with that in control subjects. In addition, we demonstrated that NID of <7.0% was an independent predictor of future deterioration of LVEF in patients with HFmrEF. Vascular structure assessed by brachial IMT and baPWV was similar in patients with HFmrEF and patients without HF. These findings suggest that vascular function, but not vascular structure, is impaired in patients with HFmrEF and that measurements of NID might be useful for prediction of future deterioration of LVEF in patients with HFmrEF.

Previous studies have clearly shown that endothelial dysfunction plays an important role in the pathogenesis and maintenance of HF, especially in patients with HFrEF and patients with HFpEF [3,4,5,6]. In patients with HFrEF, endothelial dysfunction is induced by increases in oxidative stress and neurohumoral activity, alteration of shear stress, and a decrease in nitric oxide (NO) production [26,27]. In addition, endothelial dysfunction contributes to worsening HF via impaired myocardial perfusion and ventricular function, leading to a vicious circle between endothelial dysfunction and worsening HF in patients with HFrEF. Furthermore, in patients with HFpEF, several studies (including our study) have shown that endothelial function is impaired [6,28]. Endothelial dysfunction contributes to worsening HF via delayed myocardial relaxation and impairment of vascular compliance in patients with HFpEF. However, there is no information on vascular function in patients with HFmrEF. In the present study, we found that patients with HFmrEF had both endothelial dysfunction and vascular smooth muscle dysfunction. Some possible mechanisms by which vascular dysfunction might contribute to the pathogenesis and maintenance of HFmrEF are postulated. HFmrEF may also promote vascular dysfunction via increases in oxidative stress and inflammation. Superoxide suppresses not only NO production from endothelial cells but also intracellular signaling pathways in vascular smooth muscle cells via suppressing the activity of soluble guanylyl cyclase and cGMP-dependent kinase [29]. In addition, inflammation increases the connective tissue matrix in intima–media layers of vascular smooth muscle [30,31], leading to decreases in vascular relaxation responses to endogenous and exogenous NO.

Changes in LVEF in patients with HF are a common occurrence [8]. Some investigators showed that more than one-third of patients with HFmrEF had deterioration of LVEF [9,10]. Deterioration of LVEF in patients with HFmrEF is associated with mortality and/or HF hospitalization [9]. Therefore, it is clinically important to predict future deterioration of LVEF in patients with HFmrEF. However, it is difficult to predict future deterioration of LVEF in patients with HFmrEF [11,12]. Chang et al. showed that LV global longitudinal strain was associated with LVEF changes [11]. In contrast, measurement of LV global longitudinal strain failed to predict all-cause mortality and hospitalization for HF. Tsuji et al. showed that history of ischemic heart disease and LV dilatation were significantly associated with changes in LVEF in patients with HFmrEF [10]. These findings suggest that predictors of future deterioration of LVEF in patients with HFmrEF have not been established. It is well known that vascular dysfunction is closely correlated with HF [5,6,26]. In addition, assessments of vascular function have been shown to be predictors for cardiovascular events in patients with cardiovascular disease including patients with HF [32,33]. Previously, we confirmed that NID as well as FMD was independently associated with future cardiovascular events, including healthy subjects and patients with cardiovascular disease [34]. In the present study, low NID values were predictors of future deterioration of LVEF in patients with HFmrEF. Measurement of NID may be useful for prediction of mortality and/or HF hospitalization in patients with HFmrEF. Furthermore, in patients with HFmrEF, it is likely that there is a vicious circle between vascular dysfunction and the condition of HF. Therefore, restoration of vascular function by interventions including pharmacological treatment and lifestyle modifications may prevent worsening of HF.

There are some limitations in the present study. The number of patients with HFmrEF in the follow-up study was relatively small. However, we found that NID was a predictor of future deterioration of LVEF in patients with HFmrEF. The results of this study need to be confirmed in large clinical trials in patients with HFmrEF. In addition, we had no data on NID during follow-up periods. It is unclear whether there is a change in vascular function in patients with HFmrEF during the course of treatment for HF. Further studies are needed to confirm the effects of treatment for HF in patients with HFmrEF on vascular function.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, vascular smooth muscle function is impaired in patients with HFmrEF compared with that in patients without HF. In addition, NID of <7.0% may be an independent predictor of future deterioration of LVEF in patients with HFmrEF. We should pay attention to patients with HFmrEF who have low NID during treatment for HF.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm10245980/s1.

Author Contributions

S.K. and Y.H. (Yukihito Higashi) contributed to the study design. S.K., T.M., M.K., T.H., T.Y., Y.H. (Yiming Han), A.M., Y.H. (Yu Hashimoto), C.G., F.M.Y., and A.N. performed the data collection. S.K., K.Y. performed statistical analyses after discussion with all authors. S.K. and Y.H. (Yukihito Higashi) contributed to the writing of the manuscript. Y.N. and K.C. revised the article critically for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to interpretation of data and review of the manuscript, and approved this manuscript for submission. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan (18590815 and 21590898 to Higashi).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Review Board of Hiroshima University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to institutional policies requiring a data-sharing agreement.

Acknowledgments

We thank Megumi Wakisaka, Ki-ichiro Kawano, and Satoko Michiyama for their excellent secretarial assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have anything to disclose regarding conflicts of interest with respect to this manuscript.

References

- Cheng, R.K.; Cox, M.; Neely, M.L.; Heidenreich, P.A.; Bhatt, D.L.; Eapen, Z.J.; Hernandez, A.F.; Butler, J.; Yancy, C.W.; Fonarow, G.C. Outcomes in patients with heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction in the Medicare population. Am. Heart J. 2014, 168, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, K.S.; Xu, H.; Matsouaka, R.A.; Bhatt, D.L.; Heidenreich, P.A.; Hernandez, A.F.; Devore, A.D.; Yancy, C.W.; Fonarow, G.C. Heart Failure with Preserved, Borderline, and Reduced Ejection Fraction: 5-Year Outcomes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 2476–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.D.; Hryniewicz, K.; Hriljac, I.; Balidemaj, K.; Dimayuga, C.; Hudaihed, A.; Yasskiy, A. Vascular endothelial dysfunction and mortality risk in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation 2005, 111, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kubo, S.H.; Rector, T.S.; Bank, A.J.; Williams, R.E.; Heifetz, S.M. Endothelium-dependent vasodilation is attenuated in patients with heart failure. Circulation 1991, 84, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nishioka, K.; Nakagawa, K.; Umemura, T.; Jitsuiki, D.; Ueda, K.; Goto, C.; Chayama, K.; Yoshizumi, M.; Higashi, Y. Carvedilol improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart 2007, 93, 247–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, S.; Kajikawa, M.; Maruhashi, T.; Iwamoto, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Iwamoto, A.; Oda, N.; Matsui, S.; Hidaka, T.; Kihara, Y.; et al. Endothelial dysfunction and abnormal vascular structure are simultaneously present in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 231, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Premer, C.; Kanelidis, A.J.; Hare, J.M.; Schulman, I.H. Rethinking Endothelial Dysfunction as a Crucial Target in Fighting Heart Failure. Mayo Clin. Proceedings. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2019, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lupón, J.; Gavidia-Bovadilla, G.; Ferrer, E.; de Antonio, M.; Perera-Lluna, A.; López-Ayerbe, J.; Domingo, M.; Núñez, J.; Zamora, E.; Moliner, P.; et al. Dynamic Trajectories of Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction in Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll Cardiol. 2018, 72, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarese, G.; Vedin, O.; D’Amario, D.; Uijl, A.; Dahlström, U.; Rosano, G.; Lam, C.S.P.; Lund, L.H. Prevalence and Prognostic Implications of Longitudinal Ejection Fraction Change in Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2019, 7, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, K.; Sakata, Y.; Nochioka, K.; Miura, M.; Yamauchi, T.; Onose, T.; Abe, R.; Oikawa, T.; Kasahara, S.; Sato, M.; et al. Characterization of heart failure patients with mid-range left ventricular ejection fraction-a report from the CHART-2 Study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 1258–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chang, W.T.; Lin, C.H.; Hong, C.S.; Liao, C.T.; Liu, Y.W.; Chen, Z.C.; Shih, J.Y. The predictive value of global longitudinal strain in patients with heart failure mid-range ejection fraction. J. Cardiol. 2020, 77, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, F.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Han, X.; Fan, Y.; Cao, J.; Luo, J.; Sun, A.; et al. Prognostic value of sST2 in patients with heart failure with reduced, mid-range and preserved ejection fraction. Int. J. Cardiol. 2020, 304, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higashi, Y.; Noma, K.; Yoshizumi, M.; Kihara, Y. Endothelial function and oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. Circ. J. 2009, 73, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ross, R. Atherosclerosis—An inflammatory disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celermajer, D.S.; Sorensen, K.E.; Gooch, V.M.; Spiegelhalter, D.J.; Miller, O.I.; Sullivan, I.D.; Lloyd, J.K.; Deanfield, J.E. Non-invasive detection of endothelial dysfunction in children and adults at risk of atherosclerosis. Lancet 1992, 340, 1111–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, J.; Noma, K.; Hata, T.; Hidaka, T.; Fujii, Y.; Idei, N.; Fujimura, N.; Mikami, S.; Maruhashi, T.; Kihara, Y.; et al. Rho-associated kinase activity, endothelial function, and cardiovascular risk factors. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 2353–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gokce, N.; Keaney, J.F., Jr.; Hunter, L.M.; Watkins, M.T.; Menzoian, J.O.; Vita, J.A. Risk stratification for postoperative cardiovascular events via noninvasive assessment of endothelial function: A prospective study. Circulation 2002, 105, 1567–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maruhashi, T.; Soga, J.; Fujimura, N.; Idei, N.; Mikami, S.; Iwamoto, Y.; Kajikawa, M.; Matsumoto, T.; Hidaka, T.; Kihara, Y.; et al. Nitroglycerine-induced vasodilation for assessment of vascular function: A comparison with flow-mediated vasodilation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013, 33, 1401–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lerman, A.; Zeiher, A.M. Endothelial function: Cardiac events. Circulation 2005, 111, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Khan, H.; Newman, A.B.; Lakatta, E.G.; Forman, D.E.; Butler, J.; Berry, J.D. Arterial Stiffness and Risk of Overall Heart Failure, Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction, and Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction: The Health ABC Study (Health, Aging, and Body Composition). Hypertension 2017, 69, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bueno, H.; Cleland, J.G.; Coats, A.J.; Falk, V.; Gonzalez-Juanatey, J.R.; Harjola, V.P.; Jankowska, E.A.; et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2016, 18, 891–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, S11–S24. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Jama 2001, 285, 2486–2497. [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, Y.; Maruhashi, T.; Fujii, Y.; Idei, N.; Fujimura, N.; Mikami, S.; Kajikawa, M.; Matsumoto, T.; Kihara, Y.; Chayama, K.; et al. Intima-media thickness of brachial artery, vascular function, and cardiovascular risk factors. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 2295–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kimoto, E.; Shoji, T.; Shinohara, K.; Inaba, M.; Okuno, Y.; Miki, T.; Koyama, H.; Emoto, M.; Nishizawa, Y. Preferential stiffening of central over peripheral arteries in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2003, 52, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marti, C.N.; Gheorghiade, M.; Kalogeropoulos, A.P.; Georgiopoulou, V.V.; Quyyumi, A.A.; Butler, J. Endothelial dysfunction, arterial stiffness, and heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 1455–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ontkean, M.; Gay, R.; Greenberg, B. Diminished endothelium-derived relaxing factor activity in an experimental model of chronic heart failure. Circ. Res. 1991, 69, 1088–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akiyama, E.; Sugiyama, S.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Konishi, M.; Suzuki, H.; Nozaki, T.; Ohba, K.; Matsubara, J.; Maeda, H.; Horibata, Y.; et al. Incremental prognostic significance of peripheral endothelial dysfunction in patients with heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 1778–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Münzel, T.; Feil, R.; Mülsch, A.; Lohmann, S.M.; Hofmann, F.; Walter, U. Physiology and pathophysiology of vascular signaling controlled by guanosine 3’,5’-cyclic monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Circulation 2003, 108, 2172–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Engström, G.; Melander, O.; Hedblad, B. Carotid intima-media thickness, systemic inflammation, and incidence of heart failure hospitalizations. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009, 29, 1691–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thakore, A.H.; Guo, C.Y.; Larson, M.G.; Corey, D.; Wang, T.J.; Vasan, R.S.; D’Agostino, R.B., Sr.; Lipinska, I.; Keaney, J.F., Jr.; Benjamin, E.J.; et al. Association of multiple inflammatory markers with carotid intimal medial thickness and stenosis (from the Framingham Heart Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 2007, 99, 1598–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neglia, D.; Michelassi, C.; Trivieri, M.G.; Sambuceti, G.; Giorgetti, A.; Pratali, L.; Gallopin, M.; Salvadori, P.; Sorace, O.; Carpeggiani, C.; et al. Prognostic role of myocardial blood flow impairment in idiopathic left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation 2002, 105, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Prasad, A.; Higano, S.T.; Al Suwaidi, J.; Holmes, D.R., Jr.; Mathew, V.; Pumper, G.; Lennon, R.J.; Lerman, A. Abnormal coronary microvascular endothelial function in humans with asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction. Am. Heart J. 2003, 146, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajikawa, M.; Maruhashi, T.; Hida, E.; Iwamoto, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Iwamoto, A.; Oda, N.; Kishimoto, S.; Matsui, S.; Hidaka, T.; et al. Combination of Flow-Mediated Vasodilation and Nitroglycerine-Induced Vasodilation Is More Effective for Prediction of Cardiovascular Events. Hypertension 2016, 67, 1045–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).